Non fiction stories example

3490+ Best Creative Non Fiction Short Stories to Read Online for Free

Prompts

Contests

Stories

Discover weekly, the best short stories

Looking for a steady supply of creative nonfiction short stories? Every week thousands of writers submit stories to our writing contest.

Sign up

Sign in with Google

Select a genre...AdventureAfrican AmericanAmericanAsian AmericanBedtimeBlackChristianChristmasComing of AgeContemporaryCreative NonfictionCrimeDesiDramaEast AsianFantasyFictionFriendshipFunnyGayHappyHigh SchoolHistorical FictionHolidayHorrorIndigenousInspirationalKidsLatinxLesbianLGBTQ+Middle SchoolMysteryPeople of ColorRomanceSadScience FictionSpeculativeSuspenseTeens & Young AdultThrillerTransgenderUrban FantasyWestern

Creative Nonfiction Short Stories – Page 31 of 233

“When Joey Fell” by Jack O'brien

When Joey fell there were no headlines. The story exists as family history, shared in quiet conversation over several generations. The bones of the story are these. There was an accident. A boy died. During the early years of the Great Depression, John C. and his young wife, Ida Mae, struggled to make ends meet in western Pennsylvania. John sold appliances. Money was scarce for ...

0 comments 0

Read story

“Mahon 1969” by Jay Harold

Sensitive material: Some swearing and descriptions of sexual harassment but they are a necessary part of the story. Mahon 1969 I remember it as though yesterday - “Eh, English, fucky fucky!” These words are seared in my memory. I can still hear them, even now. They were shouted at me by a raggle taggle group of young men and boys whenever I disemba...

2 comments 2

Read story

“3 Little Birds” by Justin Briggs

When I was a boy I shot three birds on a fence. The karma haunts me. It was a cold fall day, no snow on the plains, but the thought of snow in the air. My breath was crisp and chilled. There was no way to know what I was about to do. A good day for birding. I sat shooting my paper target that morning for two hours. I was a dead eye, as they say. Even with corrective lenses, I could hit anything I shot at....

The karma haunts me. It was a cold fall day, no snow on the plains, but the thought of snow in the air. My breath was crisp and chilled. There was no way to know what I was about to do. A good day for birding. I sat shooting my paper target that morning for two hours. I was a dead eye, as they say. Even with corrective lenses, I could hit anything I shot at....

0 comments 0

Read story

“Perfect Bound” by Scott Christenson

Jessica had 2 weeks to plan how she would explain her manager's misconduct to the board. Being on leave had given her ample time to run through eight years of memories over and over and recollect every detail.Her humble compact car whined as she turned it into Tristate Graphics’ entrance and headed up the driveway toward the executive offices, resisting the instinct to pull into the production plant parking lot. “Build Me Up Buttercup”, a motown classic, was playing at full volume in the car. Bobbi...

Bobbi...

17 comments 17

Read story

“All That Matters” by Anna Banana

Grow up, they said. They always told her she needed to grow up. He always told her it wasn’t her job to grow up. (Jia wasn’t the parent, Ben was. Ben had to be. He always had to be.) Ben kept her young by taking away years from his own life, raising her on his own, by making sure she never had to be the parent like he knew he had to be.

0 comments 0

Read story

“The Buzz” by Irmak Erol

It’s 2am. There is a buzz, as there always is at 2am, a metaphysical one, a buzz that’s not really about half a bottle of red wine and a couple of shots of cheap whiskey that’s been drowned inconsistently of realities of everyday life, more about the consistency of itself regardless of everyday life where it makes one eventually forget. I’m having hiccups as I am typing. Regardless, I managed to finish my cigarette. Have you ever gotten hiccups in the middle of a smoke? It’s a battle. In the bathroom, there are two ...

I’m having hiccups as I am typing. Regardless, I managed to finish my cigarette. Have you ever gotten hiccups in the middle of a smoke? It’s a battle. In the bathroom, there are two ...

0 comments 0

Read story

“Measurements” by Lavonne H.

*Proper names have been changed to protect against potential embarrassment ;)“Nana, measure me!”The memory is still vivid; evoking the excitement of two preschoolers jumping up and down beside me as I hold the pencil and the ruler over one child’s head at a time. Oh, how I dread the day the grandkids will no longer want to be measured on the wall behind the office door. It was a family tradition we had had when our sons were old enough to stand by our kitchen wall. Always excited to see what new height...

23 comments 23

Read story

“A Box of Growing Sorrows” by Abbey Gowan

There are so many beautiful things about growing up. Growing taller, figuring out who you are, always coming up with new dreams and unreachable goals for the future, and outgrowing past goals - whether you reached them or forgot about them over time. Something that once seemed so important, and so exciting can easily become something you barely even remember less than a year later. It almost seems silly that I used to th...

Growing taller, figuring out who you are, always coming up with new dreams and unreachable goals for the future, and outgrowing past goals - whether you reached them or forgot about them over time. Something that once seemed so important, and so exciting can easily become something you barely even remember less than a year later. It almost seems silly that I used to th...

2 comments 2

Read story

“How Darkness Grows” by Christian Baker

How Darkness Grows By Schrodinger Penning (Pen Name) Somedays, I just don’t want to accept it. It seems not possible, like a violation of life and reality. But that’s only if you don’t pay attention to the full picture. Life hasn’t dealt its kindest to me. Growing up, I thought I would have a good life. I loved my parents and sibli...

1 comment 1

Read story

“Beauty for Ashes ” by Cindy Strube

Beauty for Ashes Dry lightning cracks the brooding sky, pointing sharp fingers at parched earth. A tiny spark, skipping to a clump of scrubby, desiccated vegetation, ignites the tip of a woody stem - transforming drab, grayish brown to deep, glowing orange. The pungent odor hanging in the air is sweet, with a tang of metallic sharpness.##########“It’s so peaceful up here,” Bonnie sighed. “Aren’t you glad we came?” She set two plain stoneware mugs carefully ...

A tiny spark, skipping to a clump of scrubby, desiccated vegetation, ignites the tip of a woody stem - transforming drab, grayish brown to deep, glowing orange. The pungent odor hanging in the air is sweet, with a tang of metallic sharpness.##########“It’s so peaceful up here,” Bonnie sighed. “Aren’t you glad we came?” She set two plain stoneware mugs carefully ...

10 comments 10

Read story

“Marks on the Doorway” by Sapphire Rose

The smell of vinegar on the once, freshly cut door frame, was gone now, but the honey oak had kept its sanded posture. Incisions made by my Grandfather, measuring the height of our growth, crept up the body of the doorway. I didn’t want to come back here like this. Two years ago we left Canada in 2009. The move to Chicago from Pickering, Ontario, had been the heaviest felt, and hardest to forget. I had left behind best friends who knew the innermost parts of who I was, a boyfriend who I had only known. ..

..

0 comments 0

Read story

“To be or not to be” by Layla Robinson

Content warning: pregnancy/pro choice Perched on the edge of a public toilet seat, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. And no, it wasn’t the ridiculous messaging on the walls around me. “Things I hate: 1. Vandalism, 2. Irony, 3. Lists.” Hardy har har, as if that one hasn’t been done before. Or, “Whoa, that’s a lot of corn!” Gross. Or my personal favourit...

4 comments 4

Read story

“Dear diary” by F.O. Morier

Dear diary, I don´t know what day it is today, and frankly, I don´t care what day of the week it is. I´m looking for a sense of relief. Can I find some here, on these virgin papers of yours? A long time ago I set aside my creative dreams to become something else. I lost myself in that process. And now, here I am a collapsed star. How I long to return to a realm of beaut...

I lost myself in that process. And now, here I am a collapsed star. How I long to return to a realm of beaut...

5 comments 5

Read story

“Grandfather's Tree” by Manijeh Khorshidi

Manijeh Khorshidi 2022 Grandfather’s Tree I find my grandfather sitting on a chair in the shady part of the backyard with closed eyes and a gentle smile on his face that betrays his calm. A book half-opened rests on his chest, and glasses sit on top of his head. The almost five-year-old me gets closer and puts her head on his lap. Without opening his eyes or uttering any wor...

2 comments 2

Read story

“Wanted: A Green Thumb” by Dee Leger

Fields of wildflowers, baskets of fresh fruits and vegetables, the smell of freshly tilled soil: to quote an old song "These are a few of my favorite things. "I was raised in cities all over the world as the child of a United States Navy sailor. Some countries have multiple tropical forests filled with ferns, flowers, and the earthy smell of mud. Other countries are miles and miles of farmland, rice fields, coffee beans, and exotic fruits. Even in the busiest cities apartment balconies overflowed with potted plants and fl...

"I was raised in cities all over the world as the child of a United States Navy sailor. Some countries have multiple tropical forests filled with ferns, flowers, and the earthy smell of mud. Other countries are miles and miles of farmland, rice fields, coffee beans, and exotic fruits. Even in the busiest cities apartment balconies overflowed with potted plants and fl...

3 comments 3

Read story

10 Great Creative Nonfiction Books -

Tineke Bryson, Staff Writer

Last week Tineke addressed writing about our own life experiences, sharing 8 ways to do creative nonfiction well. But if you found yourself wondering what exactly creative nonfiction (CNF) is, and what sorts of books represent the genre, you are not unusual.

…

“Where is your creative nonfiction section?”

A film of panic clouds the eyes of the Half Price Books employee looking at me from across the trade-in counter.

“Memoirs, for example,” I offer.

“Do you mean biographies?”

“Sure,” I say. That’s not it at all, but I hope the biographies might be somewhere close to the CNF section—if it exists. When I eventually locate the small block of shelves allotted to CNF, I find them labeled as “Essays,” “Memoirs,” and “Letters.” Letters…charmingly old-fashioned. These are not letters as we think of them; they are not written to a person, but you could say they are written to humanity.

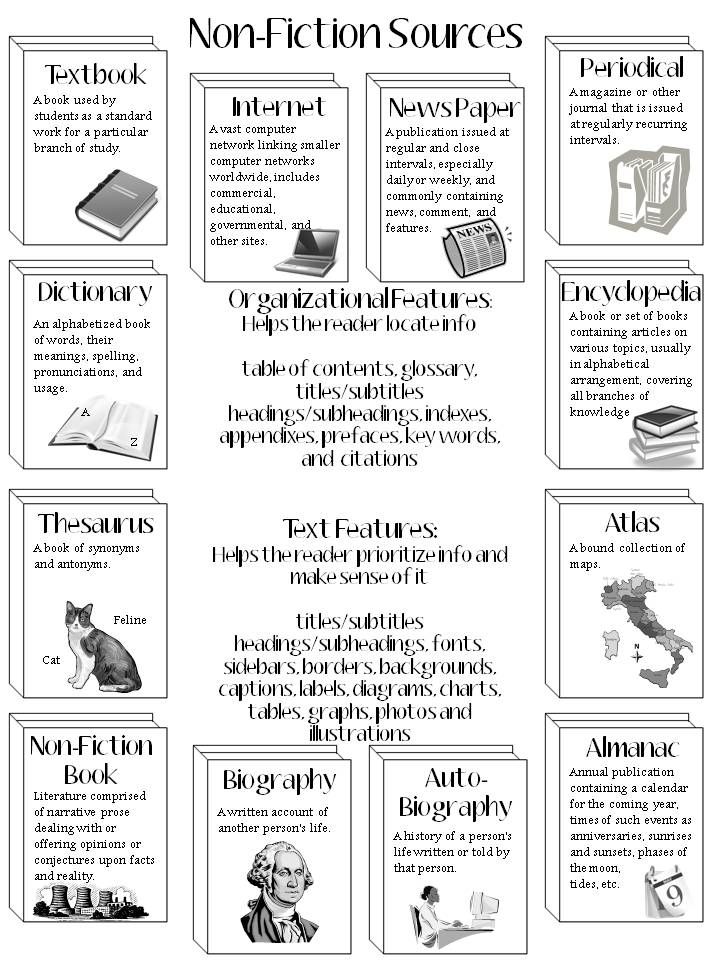

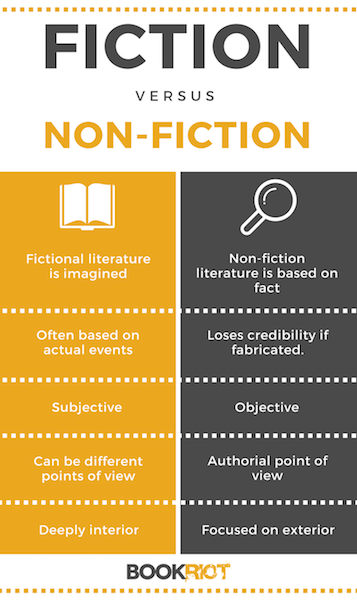

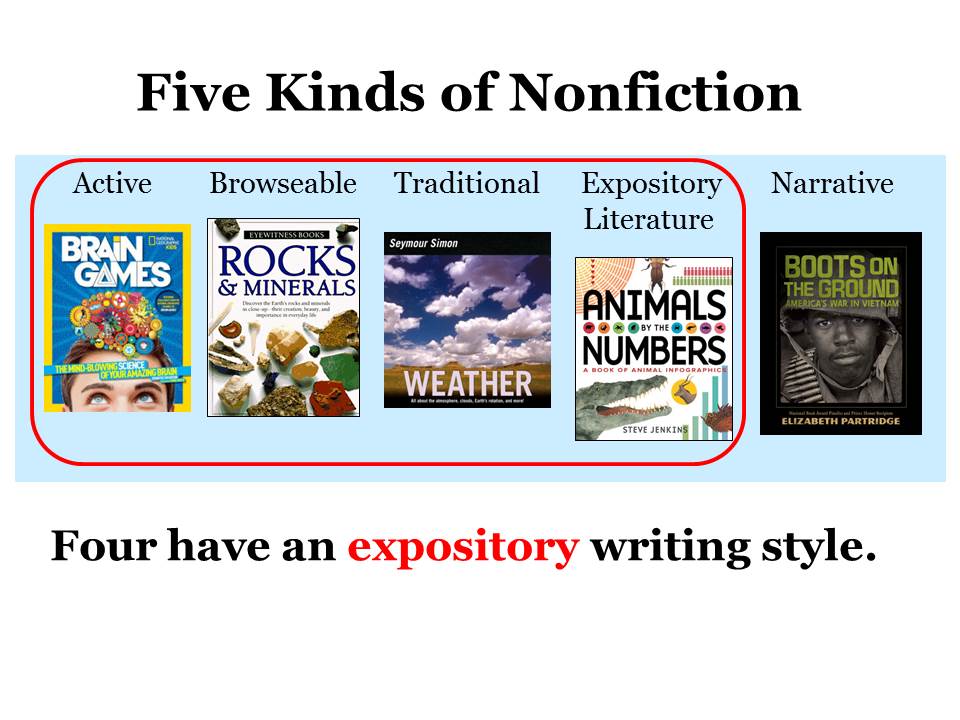

I get why CNF is not widely understood. But I am sad that so many people are never disabused of the grade-school notion that nonfiction is just history textbooks, science fact books, newspapers, and encyclopedias.

I want to challenge that idea.

Yet when I tell people that CNF is nonfiction that uses all the tools of fiction—extended metaphor, symbolism, plot structure, etc.—I always feel frustration. Because I know how easy it is to ask, “But don’t scholarly articles use metaphors?” or “Isn’t there a plot in a biography?”

Because I know how easy it is to ask, “But don’t scholarly articles use metaphors?” or “Isn’t there a plot in a biography?”

Yes. And, yes.

Creative nonfiction as a genre label is easy to define but difficult to restrict. The definition in Wikipedia, for example, sounds simple enough:

Creative nonfiction (also known as literary nonfiction or narrative nonfiction) is a genre of writing that uses literary styles and techniques to create factually accurate narratives. Creative nonfiction contrasts with other nonfiction, such as technical writing or journalism, which is also rooted in accurate fact, but is not primarily written in service to its craft.

Yet when I try to put myself in the shoes of a journalist, I think I would take issue with defining journalism as rooted in fact but not written “in service to” craft. Great journalism can be creative, and is definitely a craft.

And then I wonder if it could be said that personal blog posts are all CNF. That doesn’t go down easily either. Blog posts are not technical writing or journalism, but so few blog posts are crafted. (Or is it just me?)

That doesn’t go down easily either. Blog posts are not technical writing or journalism, but so few blog posts are crafted. (Or is it just me?)

What I want to do is scream, “Just read some examples and you will see what I mean!”

So this post is a virtual scream. Not because I am angry; just because I would love to see more writers and readers give CNF a go, and I think reading classic examples is more helpful than a definition.

What follows is a list of 10 books I consider compelling examples of the power and range of CNF. I have only included books I have read, so it should go without saying—yet must be said—that this is not a list of the ten best CNF books. They are also not in a particular order.

1. An American Childhood by Annie Dillard

Annie Dillard is one of today’s most celebrated CNF writers. Her prose punches holes in other people’s prose. This book is an interesting example of a memoir written not about the author herself but as an exploration of a specific theme: what it feels like to be “alive. ”

”

I defy anyone to read An American Childhood and not catch curiosity fever. Her powers of observation of the natural world are wonderful. She is esteemed both as a memoirist and as a riveting nature writer.

2. The Genesee Diary by Henri Nouwen

Henri Nouwen, evangelicalism’s favorite Catholic (yes, I know about Tolkien), kept a journal during a six-month stay at a Trappist monastery in Western New York. The result is this quiet, but grounding spiritual travel log—Nouwen is physically restricted, but slowly journeying to a wide and open peace in his inner life.

It’s a strong example of editing and re-sequencing a private journal to present to others. It’s also interesting because it manages to avoid being a devotional book while exploring devotion.

3. Dandelion Wine by Ray Bradbury

Like An American Childhood, this is a memoir, but Ray Bradbury has taken creative liberties in the telling that many memoirists would eschew.

A celebration of childhood, Dandelion Wine is delightful while also sometimes somber, and is a provocative read for writers trying to work out what the balance should be between fact and storytelling in their own nonfiction work.

I enjoy comparing and contrasting this book to Dillard’s.

4. Dakota: A Spiritual Geography by Kathleen Norris

When poet Kathleen Norris moves from NYC to Lemmon, South Dakota, to take possession of an old family home, she finds herself confronted and changed by the landscape.

This book is a meditation on the power of landscape and climate to shape culture and the soul, and is also a tribute to place. It is by turns poetic and informative—a great example of writing about place without primarily writing about the self. The non-chronological structure of the book is also interesting.

5. The Confessions of Saint Augustine by Augustine of Hippo

The Confessions of Saint Augustine by Augustine of Hippo

This is arguably the first creative nonfiction autobiography, although that is far from the way most people read it. It is also one of the most influential. In a single semester during college, I was expected to read this book for classes in writing, church history, and world literature.

Apart from saving me a lot of time, studying it in three contexts underlined for me how complex a work of CNF can be—a frank, crafted account of the self can be read on many levels and stand among the classics of literature.

6. 1000 Gifts by Ann Voscamp

If there is a way for the publishing industry to market a book for women, they understandably will. But I can’t quite forgive them for doing this with the writing of Ann Voscamp. This fierce and stark exploration of the meaning of suffering and the power of gratitude is not just for ladies—despite what the girly cover would suggest.

I am so glad I got past the cover and gave this book a chance. Stunning prose. Heartfelt and moving wrestle with God. Just switch out the jacket!

7. The Wild Places by Robert Macfarlane

In an absorbing example of travel writing and nature writing, Macfarlane embarks on a quest to find and “map” the dwindling wild places of the British Isles; each chapter is dedicated to a different place. The prose is gorgeous but tempered. Macfarlane is good at knowing how and when to move between description, narrative, and thematic content, such as natural history, conservation, and stories of writers influenced by landscape.

To read a shorter specimen of his, I recommend The word-hoard: Robert Macfarlane on rewilding our language of landscape, (The Guardian).

8. A Severe Mercy by Sheldon Vanauken

This book is shaped, as was the author, by the writings of Lewis, with whom Vanauken was friends. It is something of a combination of Lewis’s Surprised by Joy and A Grief Observed (also fine examples of CNF), in that it is a love story, a story of conversion to Christian faith, and a story of a great loss.

It is something of a combination of Lewis’s Surprised by Joy and A Grief Observed (also fine examples of CNF), in that it is a love story, a story of conversion to Christian faith, and a story of a great loss.

I find it more relatable than Lewis’s CNF, perhaps because Vanauken’s writing voice is not quite so gruff and he is less private.

9. Wind, Sand, and Stars by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Today, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry is best known for the philosophical children’s classic The Little Prince. However, in literary circles, he is considered primarily a travel writer and is especially beloved for his stories and meditations on early aviation.

This book tells of his beginnings as a pilot, meditates on legendary pilot adventures, and also documents in whimsical but vivid terms his stint as a commercial pilot in the Sahara, including his survival of a crash landing in the desert. I find it especially compelling for its strange blend of colonial ethnocentrism and warm sympathy for individual Africans.

I find it especially compelling for its strange blend of colonial ethnocentrism and warm sympathy for individual Africans.

10. Markings by Dag Hammarskjöld

Not unusually, the English title of this book does not quite capture the sense of the Swedish Vägmärken, which is more along the lines of “markers along the road.” It is the gathered diary entries of the second Secretary-General of the United Nations, who served from 1953 until his death in a plane crash in 1961.

He began writing entries at age 20. The book is interspersed with haiku-style poems, and covers many topics. The guiding idea of Markings is his search for meaning in everything he encountered and experienced.

…

What are some CNF books you like? I would love to read your recommendations in the comments!

…

About Tineke

Tineke Bryson works for One Year Adventure Novel as a kind of jane-of-all-trades, but her favorites trade of the lot is editing. Previous to OYAN, she graduated from Houghton College with an Honors in Writing and then worked as an editor for a large para-church organization.

Previous to OYAN, she graduated from Houghton College with an Honors in Writing and then worked as an editor for a large para-church organization.

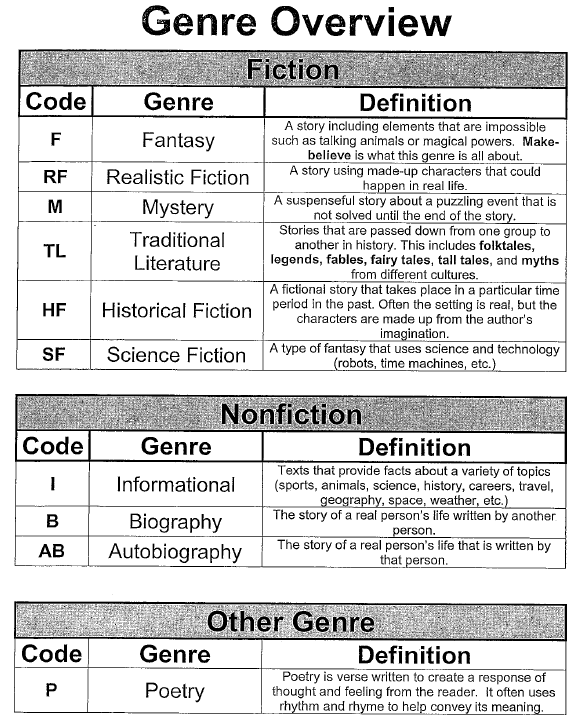

Genre of a literary work - Writer's Handbook

Why does an author need to understand genres?

Then, in order to:

a) to learn mastery in one's own genre;

b) know exactly which publisher to submit the manuscript to;

c) study your target audience and offer the book not to “everyone in general”, but to those people who may be interested in it.

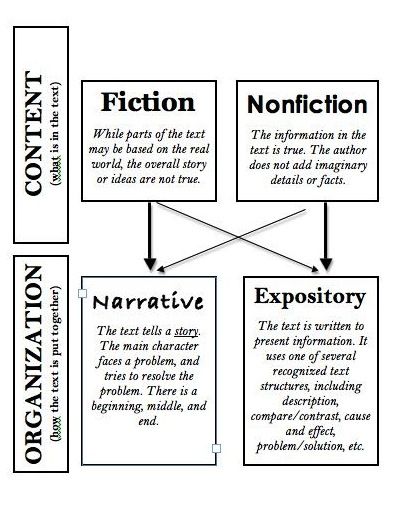

What is fiction?

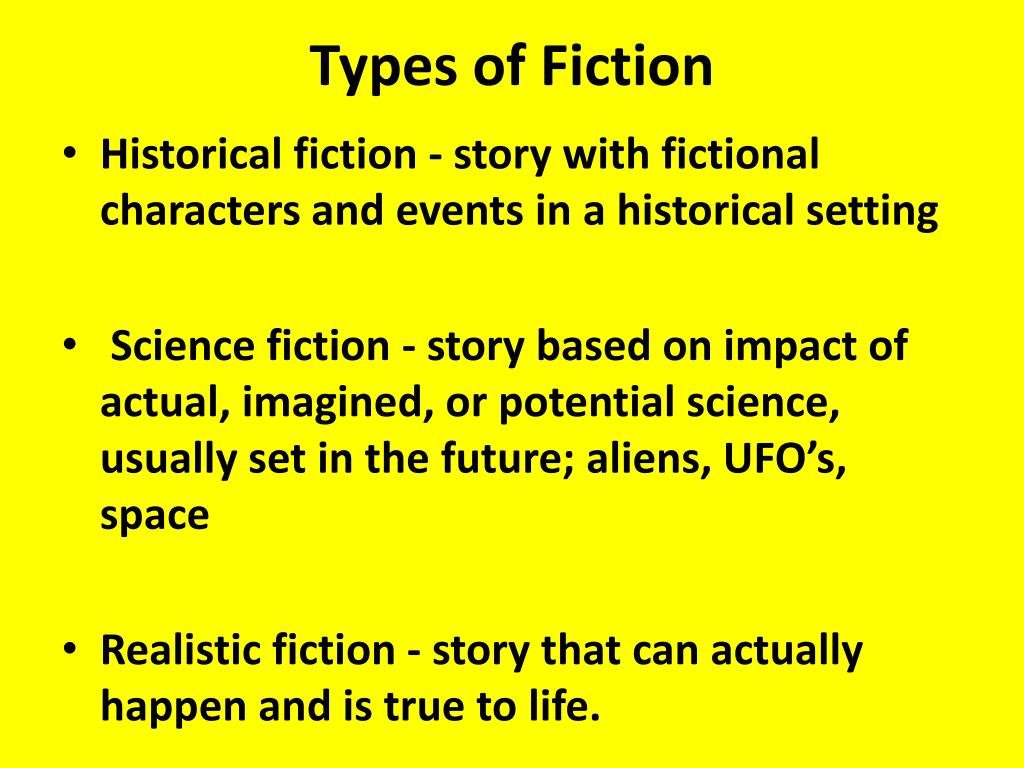

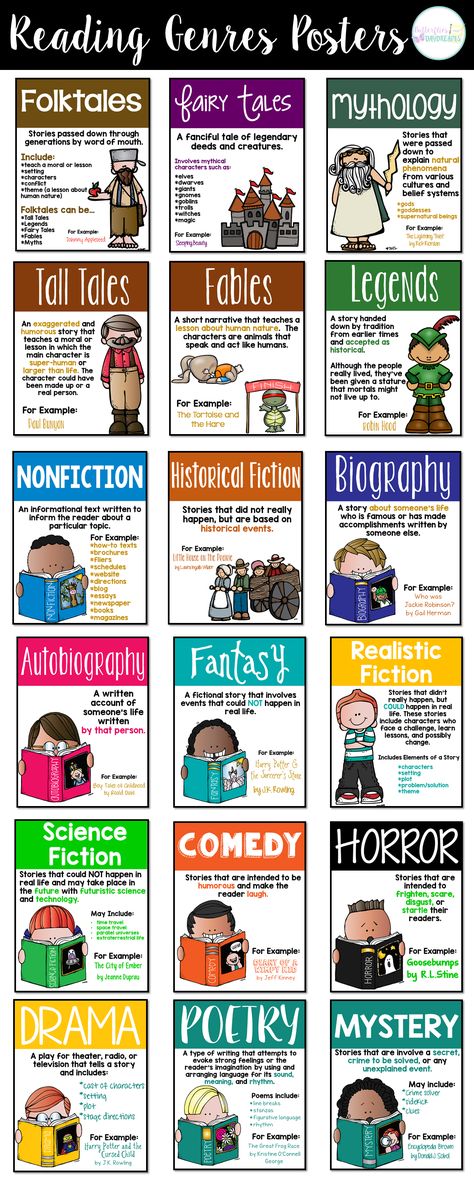

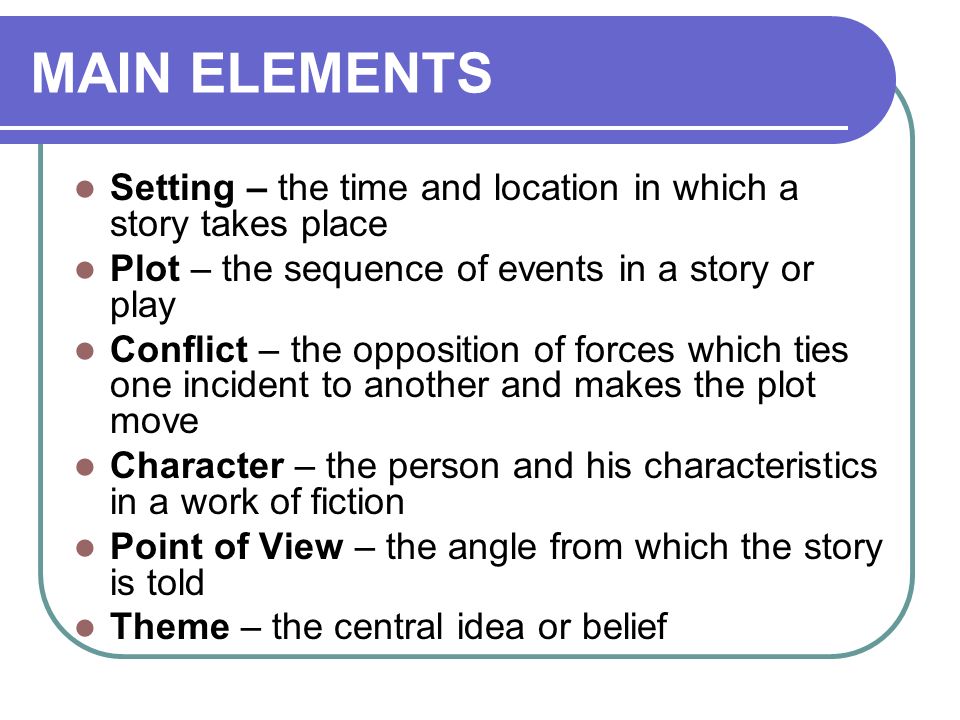

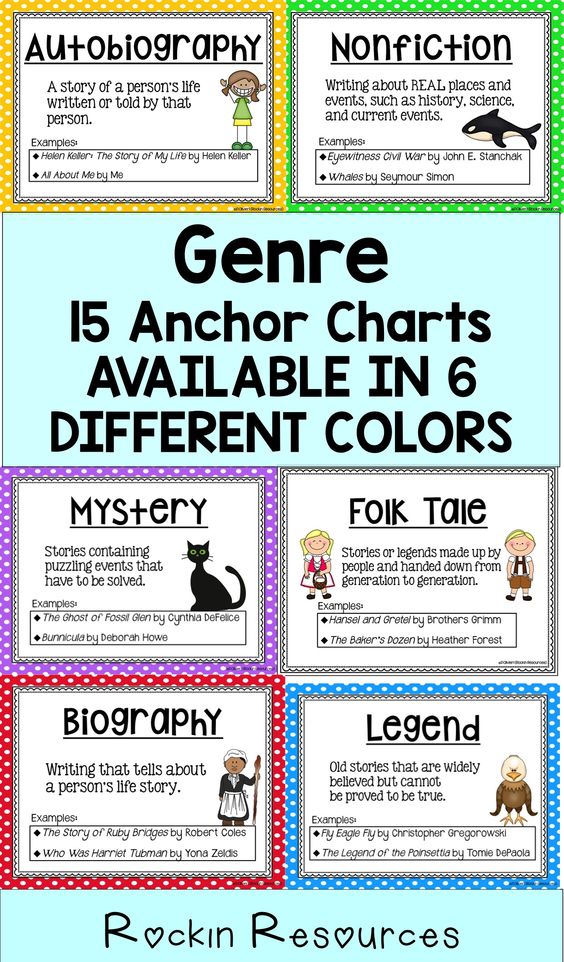

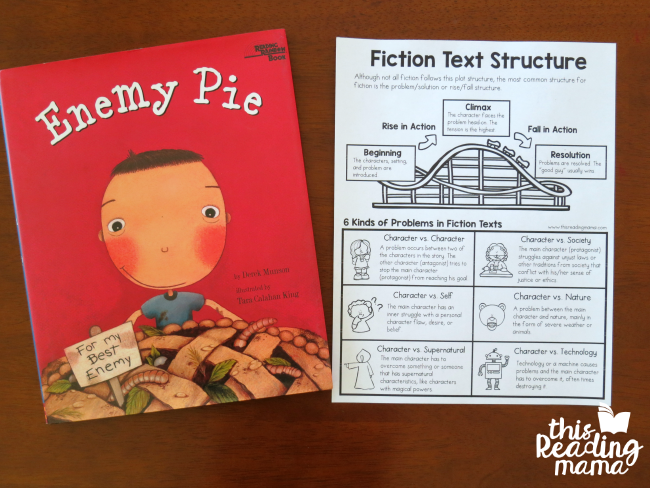

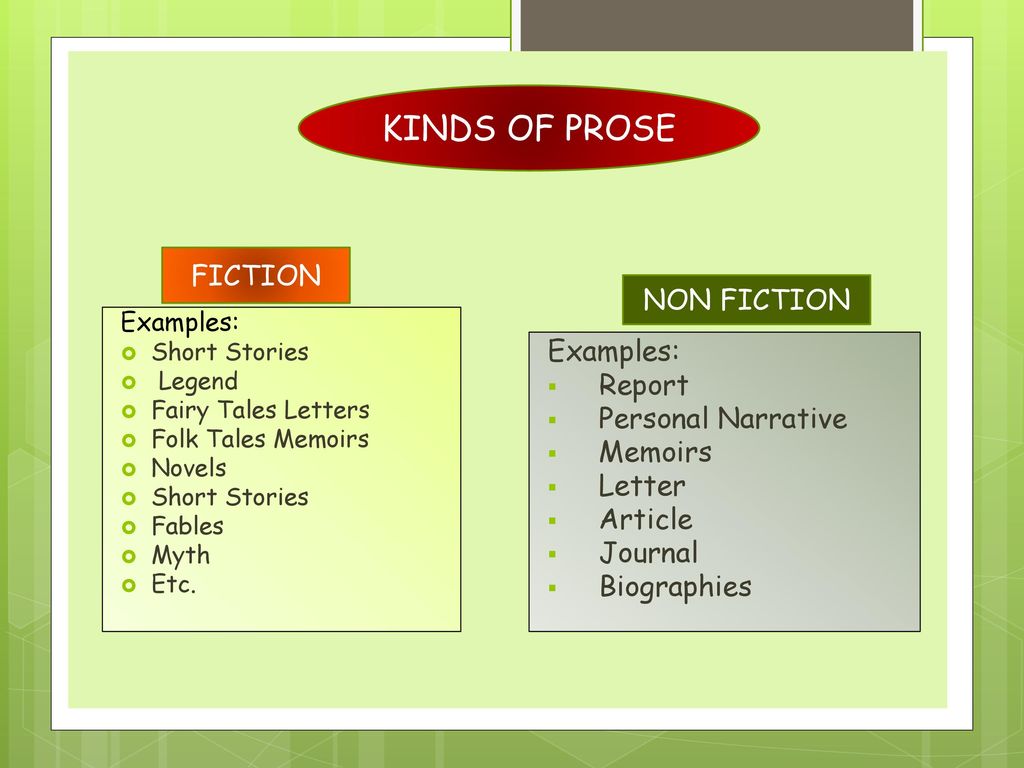

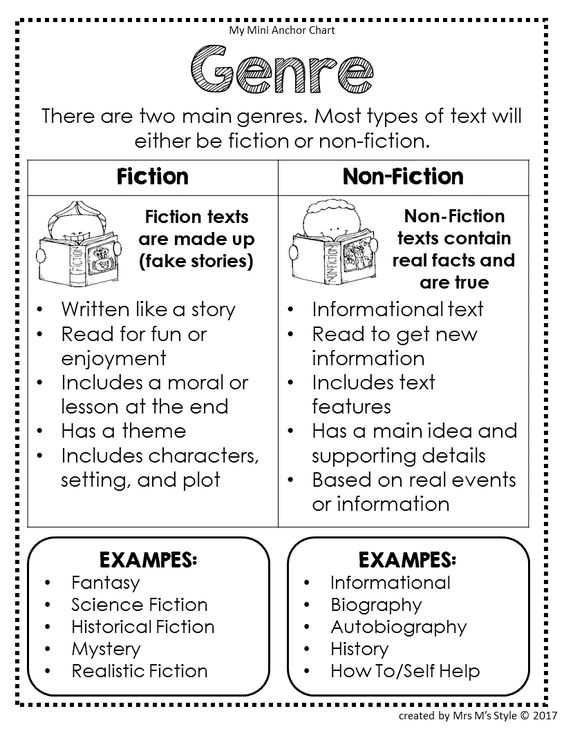

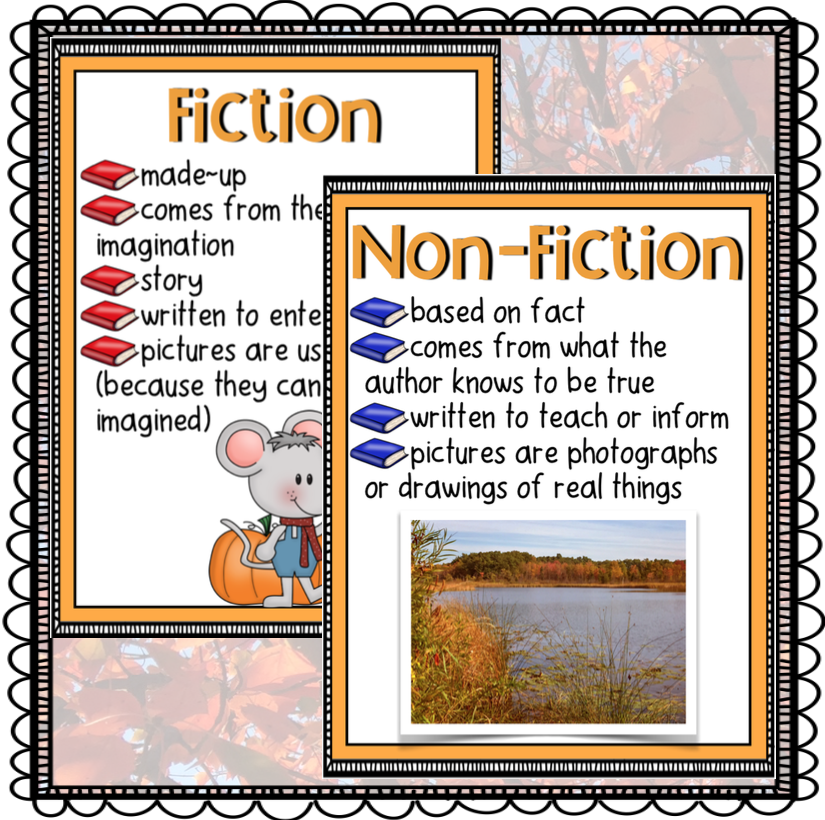

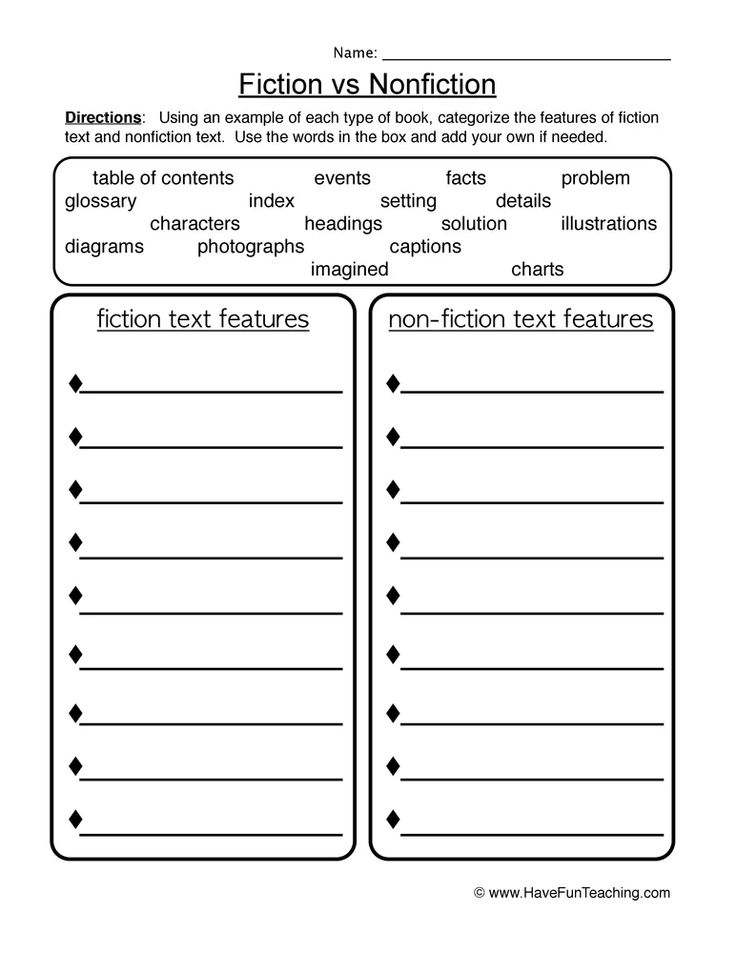

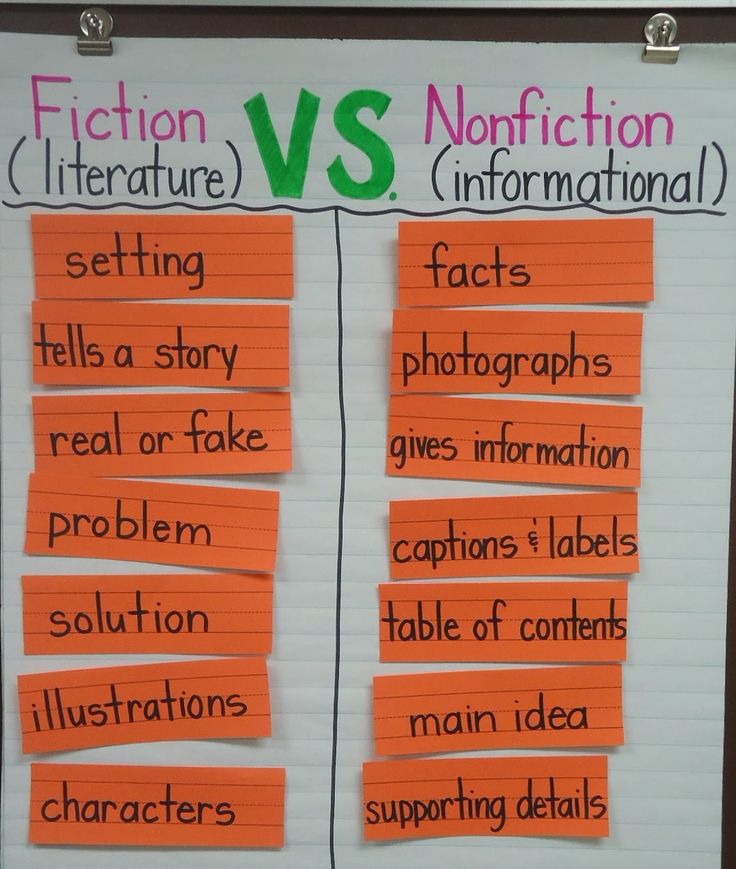

Fiction refers to all works that have a fictional plot and fictional characters: novels, short stories, short stories and plays.

Memoirs are classified as non-fiction because they are not fictitious events, but they are written according to the canons of fiction - with a plot, characters, etc.

But poetry, including lyrics, is fiction, even if the author recalls a past love that actually happened.

Types of fiction for adults

Fiction is divided into genre literature, mainstream and intellectual prose.

Genre literature

In genre literature, the plot plays the first fiddle, while it fits into certain, previously known frameworks.

This does not mean that all genre novels should be predictable. The writer's skill lies precisely in creating a unique world, unforgettable characters and an interesting way to get from point "A" (start) to point "B" (denouement) under given conditions.

As a rule, a genre work ends on a positive note, the author does not delve into psychology and other lofty matters and simply tries to entertain readers.

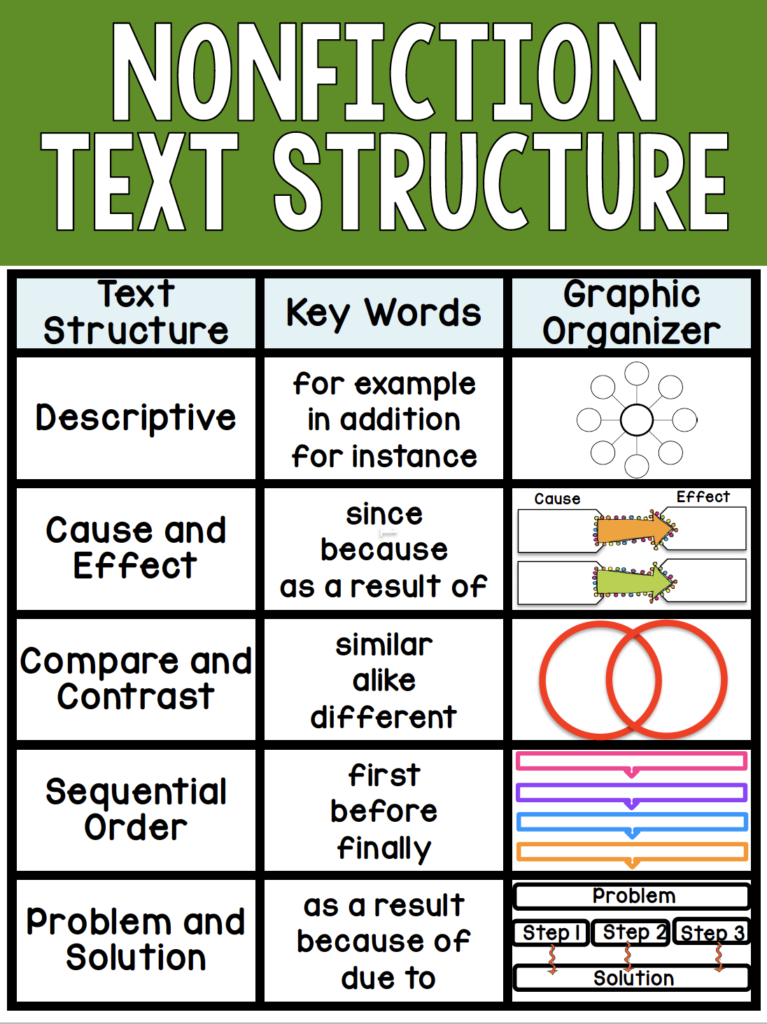

Basic plot schemes in genre literature

Detective: crime - investigation - exposure of the criminal.

Love story : heroes meet - fall in love - fight for love - unite hearts.

Thriller: the hero lived his usual life - a threat arises - the hero tries to escape - the hero gets rid of the danger.

Adventures: the hero sets a goal and, having overcome many obstacles, achieves what he wants.

When we talk about science fiction, fantasy, historical or modern novel, we are talking not so much about the plot as about the scenery, so when defining the genre, two or three terms are used that allow us to answer the questions: “What happens in the novel?” and "Where is it happening?". If we are talking about children's literature, then an appropriate note is made.

Examples: “modern romance novel”, “fantastic action movie” (action movie is adventure), “historical detective story”, “children's adventure story”, “fairy tale for primary school age”.

Genre prose, as a rule, is published in series, either author's or general.

Mainstream

In the mainstream (from English mainstream - the main stream) readers expect unexpected solutions from the author. For this type of book, the most important thing is the moral development of the characters, philosophy and ideology. The requirements for a mainstream author are much higher than for writers working with genre prose: he must be not only an excellent storyteller, but also a good psychologist and a serious thinker.

Another important feature of the mainstream is that such books are written at the intersection of genres. For example, it is impossible to say unequivocally that Gone with the Wind is only romance or only historical drama.

By the way, the drama itself, that is, the story of the tragic experience of the characters, is also a sign of the mainstream.

As a rule, novels of this type are published outside the series. This is due to the fact that serious works are written for a long time and it is rather problematic to form a series of them. Moreover, mainstream authors are so different from each other that it is difficult to group their books on any basis other than “good book”.

When specifying the genre in mainstream novels, the emphasis is usually placed not so much on the plot as on certain distinguishing features of the book: historical drama, novel in letters, fantastic saga, etc.

Origin of the term

writer and critic William Dean Howells (1837–1920). As editor of one of the most popular and influential literary magazines of his time, The Atlantic Monthly , he had a clear preference for works written in a realistic vein and emphasizing moral and philosophical issues.

As editor of one of the most popular and influential literary magazines of his time, The Atlantic Monthly , he had a clear preference for works written in a realistic vein and emphasizing moral and philosophical issues.

Thanks to Howells, realistic literature became fashionable, and for some time it was called the mainstream. The term was fixed in English, and from there it moved to Russia.

Intellectual prose

Unlike the mainstream, which should appeal to a wide readership, intellectual prose is focused on a narrow circle of connoisseurs and claims to be elitism. The authors do not set themselves the goal of commercial success: they are primarily interested in art for the sake of art and the opportunity to share something sore with the world.

In the overwhelming majority of cases, intellectual prose has a gloomy tone and is published outside the series.

Main genres of fiction

Approximate classification

When applying to a publisher, we must indicate the genre so that our manuscript is sent to the appropriate editor.

The following is an indicative list of genres as they are understood by publishers and bookstores.

- Avant-garde literature. Characterized by a violation of the canons and language and plot experiments. As a rule, the avant-garde comes out in very small editions. Closely intertwined with intellectual prose.

- Action. Focused primarily on the male audience. The basis of the plot is fights, chases, saving beauties, etc.

- Detective. The main storyline is the disclosure of a crime.

- Historical novel . The time of action is the past. The plot, as a rule, is tied to significant historical events.

- Love story. Heroes find love.

- Mystic. The plot is based on supernatural events.

- Adventure. Heroes embark on an adventure and/or embark on a perilous journey.

- Thriller/Horror.

The heroes are in mortal danger, from which they are trying to get rid of.

The heroes are in mortal danger, from which they are trying to get rid of. - Fantasy. The plot is set in a hypothetical future or in a parallel world. One of the varieties of fantasy is alternative history.

- Fantasy/fairy tales. The main features of the genre are fairy-tale worlds, magic, unseen creatures, talking animals, etc. Often based on folklore.

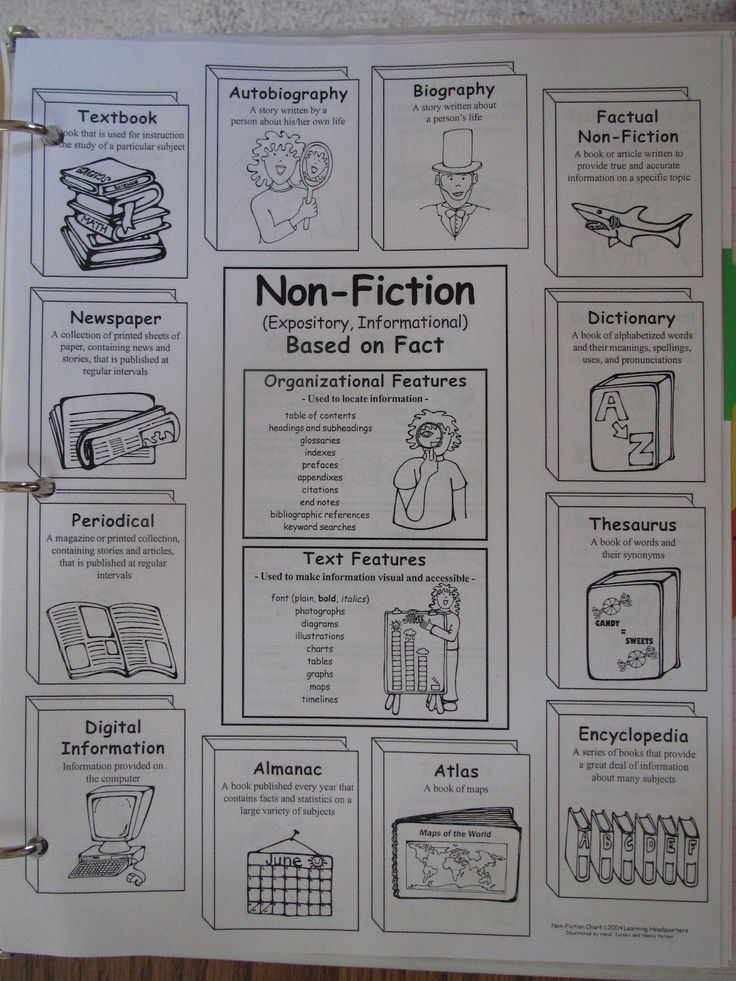

What is non-fiction?

The category of non-fiction includes textbooks, encyclopedias, dictionaries, biographies, journalism, etc. That is, all books that describe life as it is.

Non-fiction books are classified by subject (eg gardening, history, etc.) and type (scientific monograph, collection of articles, photo album, etc.).

The following is a classification of non-fiction books, as is done in bookstores. When applying to a publisher, indicate the topic and type of book - for example, a textbook on writing.

Classification of non-fiction

- autobiographies, biographies and memoirs;

- architecture and art;

- astrology and esotericism;

- business and finance;

- armed forces;

- upbringing and education;

- house, garden, kitchen garden;

- health;

- history;

- career;

- computers;

- local history;

- love and family relationships;

- fashion and beauty;

- music, film, radio;

- science and technology;

- food and cooking;

- deluxe editions;

- politics, economics, law;

- guides and travel books;

- religion;

- self-development and psychology;

- agriculture;

- dictionaries and encyclopedias;

- sports;

- philosophy;

- hobby;

- school books;

- linguistics and literature.

Peculiarities of non-fiction prose by T. Pynchon Text of a scientific article on the specialty "Linguistics and Literary Studies"

Bulletin of the Moscow University. SER. 9. PHILOLOGY. 2008. No. 3

present Kireeva

Peculiarities of non-fiction prose by T. Pinchon

Thomas Pynchon is one of the brightest and most enigmatic figures in contemporary US literature. In almost half a century of literary activity, six novels and one collection of short stories by the writer have been released, firmly inscribed in the paradigm of postmodernism and legitimizing a new artistic practice, as well as laying the foundation for a kind of “Pynchon cult”, in the creation of which the writer himself took a direct part, transferring the role critical assessments of their work to readers, inventively using various kinds of hoaxes, rarely publishing works1.

At the same time, despite the conscious elimination of the obligatory ways for a modern creator to be present in the modern media environment (interviews, meetings with readers, TV appearances on topical issues of modern life, participation in talk shows, etc. ), Pynchon does not refuses such a traditional type of writing as the creation of various samples of non-fiction prose with its characteristic forms of literary self-reflection (reflections on literature and the place of the writer in the autopreface, reviews of literary and musical works, essays and prefaces to novels and stories of his fellow writers, as well as speeches in their support). These "rare essays, reviews and notes, which accidentally formed one of the excellent uncollected anthologies in American literature"2 are a single meta-text, the individual parts of which are interconnected by a complex of recurring themes, motifs, images, and, in addition, are correlated with literary works of Pynchon and the specifics of his writing behavior.

), Pynchon does not refuses such a traditional type of writing as the creation of various samples of non-fiction prose with its characteristic forms of literary self-reflection (reflections on literature and the place of the writer in the autopreface, reviews of literary and musical works, essays and prefaces to novels and stories of his fellow writers, as well as speeches in their support). These "rare essays, reviews and notes, which accidentally formed one of the excellent uncollected anthologies in American literature"2 are a single meta-text, the individual parts of which are interconnected by a complex of recurring themes, motifs, images, and, in addition, are correlated with literary works of Pynchon and the specifics of his writing behavior.

The writer turns to the creation of non-fiction prose from the very beginning of his literary activity3. However, the most intensively the main themes of literary self-reflection (the position of literature in the modern world, the place of the creator, relations with the reader, the history of the creation of works, the problem of tradition and innovation, the relationship between life and art, etc. ) are comprehended by Pynchon in adulthood, starting from 1980- 1990s, at a time when a stable reputation as a cult author was formed, complemented by the image of a “reclusive writer”, each of the

) are comprehended by Pynchon in adulthood, starting from 1980- 1990s, at a time when a stable reputation as a cult author was formed, complemented by the image of a “reclusive writer”, each of the

whose statements “about time and about myself” were perceived as a kind of revelation, became an event in the literary and cultural life of the United States.

First of all, the problem of literary self-reflection finds expression in Pynchon's statements about the work of his fellow writers, which, starting from 1966, appear in the form of short advertising reviews on book covers (a total of more than 30 reviews over 40 years). Often, these small comments grew into full-fledged prefaces to the texts of peer-reviewed writers. this was the case with the cover review of Pynchon's friend R. Farigny's Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me, 1966), the second edition of which in 1983 was preceded by an already extensive preface by Pynchon4. History repeated itself with Iowa professor Jim Dodge's novel Stone Junction (Stone Junction, 1990), which, when reprinted in 1997, was accompanied by a foreword by the author of Gravity's Rainbow5. Each of these prefaces, as well as reviews of O. Hall's novels Warlock (1965) and G.G. Marquez "Love in the Time of Cholera" (1988)6, as well as the preface to the collection of prose by D. Bartelmy (1992)7 and to the novel by J. Orwell "1984" (2003)8, appear as parts of Pynchon's metatext devoted to the problems of literary self-reflection and shedding light on the strategies of their creator's writer's behavior.

Each of these prefaces, as well as reviews of O. Hall's novels Warlock (1965) and G.G. Marquez "Love in the Time of Cholera" (1988)6, as well as the preface to the collection of prose by D. Bartelmy (1992)7 and to the novel by J. Orwell "1984" (2003)8, appear as parts of Pynchon's metatext devoted to the problems of literary self-reflection and shedding light on the strategies of their creator's writer's behavior.

Forming a single text of Pynchon's non-fiction prose, reviews and prefaces present unequal paratexts of Hall, Farigny, Marquez, Bartelmy, Dodge, Orwell, determined by the originality of the author's style of the analyzed works. In addition, the features of their discourse are caused by the multidimensionality of the “image of the reader” inherent in each of these works by Pynchon, produced, firstly, by the specifics of the audience of these authors, and secondly, by the obligatory presence in the minds of their creator of the image of “their own” reader – the reader, i. e. reader. Pynchon.

e. reader. Pynchon.

This complexity of the "image of the reader" as a special communicative structure gives rise to the multi-level nature of the "image of the author", which, due to the peculiarities of the genre of review and preface, appears as another hypostasis of the "image of the reader", combining three unequal reading positions. Firstly, the "ordinary" reader, who enjoys reading and describes his reader's reactions. Secondly, the “professional reader” is a critic, a researcher who consciously reflects on the work of a particular author, inscribes it in a certain literary, biographical, historical context and analyzes the work from the point of view of its artistic structure. And finally, the reader as a writer, considering the central problems for his own works through

the prism of the creativity of fellow writers. It is this third position that is directly related to the problems of literary self-reflection. However, only the integrity of the structure, supplemented by the positions of "ordinary" and "professional" readers, allows Pynchon to effectively ensure the relationship between the figurative nature of the text and its reception, actualizing and concretizing the meaning in the mind of the real reader.

The most interesting from the point of view of Pynchon's literary self-reflection is his autopreface to the collection Slow Learner, 1984). Here the problems of tradition and innovation, the relationship between life and art, the circumstances of becoming a writer and the history of the creation of works receive the most consistent embodiment. In doing so, the author is reframing the traditional structure of a writing textbook, preferring to show his early work as an example "illustrating the typical problems of entry-level literature and warning against methods that young writers should avoid"9. It is no coincidence that the whole collection is prefaced with the title "The Slow Learner": this metaphor of "apprenticeship through mistakes" defines the author's attitude, serves as a kind of justification for the very idea of publishing a collection of his early stories and allows you to present the preface and subsequent stories as a kind of "textbook of mastery" on the contrary.

Another example of Pynchon's non-fiction prose, included in the tradition of writing reviews and book reviews, are two reviews of music discs that appeared in 1994 and 199510 The writer's seemingly unexpected desire to try himself as a music critic no longer seems such, if we remember that as a young man Pynchon dreamed of a career in the music industry11. Acquaintance with reviews of music discs convinces that Pynchon perfectly masters the discourse of a music critic who is versed in the history of modern and classical music, subtly analyzes the musical specifics of the albums being analyzed and has a very original view of the musical culture of his time. In addition, talking about the musical experiment being undertaken by the writers of the reviewed albums allows Pynchon to reflect in passing on the difficulties that await any innovator who uses experimental practices and at the same time strives to be understood by the widest possible audience.

In addition to discussing the whole range of problems of literary self-reflection in autoprefaces, reviews, prefaces to the texts of fellow writers and musicians, an essential feature of these examples of Pynchon's non-fiction prose is the ability to

consider the very fact of their appearance as a result of the institutional recognition of the writer, to which editors and publishers are treated as some kind of authoritative figure in the field of literature. As a result, by creating texts similar to prefaces and reviews, the writer supports not only fellow writers, but also, appealing to their authority, associates in the workshop of postmodern literature (Bartelmy), recognized figures of American (Hall) and world (Marquez, Orwell) literature , American authors - experimenters in literature and music (Farigna, Dodge, Jones), uses the opportunity to speak out the problems important for their own artistic creativity in a direct conversation with the reader, to fit their works into the context of American and world literature and culture.

As a result, by creating texts similar to prefaces and reviews, the writer supports not only fellow writers, but also, appealing to their authority, associates in the workshop of postmodern literature (Bartelmy), recognized figures of American (Hall) and world (Marquez, Orwell) literature , American authors - experimenters in literature and music (Farigna, Dodge, Jones), uses the opportunity to speak out the problems important for their own artistic creativity in a direct conversation with the reader, to fit their works into the context of American and world literature and culture.

One of Pynchon's important problems of literary self-reflection - the writer's place in the contemporary socio-cultural situation - finds expression in an essay on Sloth (Nearer, My Couch, To Thee, 1993)12, thematically related to another work of that same genre - "Is it good to be a Luddite?" (Is It OK To Be a Luddite?, 1984)13. Analyzing some of the mass stereotypes in the perception of Sloth and its varieties, the author focuses on one of them - the notions of writers, in the public mind acting as "crown specialists on Sloth", to whom "constantly turn <. ..> with flattering requests - to speak at the Symposium on Problems of Sloth, to head the Commission on the Affairs of Sloth, to testify as an expert at the Hearings on the Question of Sloth” [On Sloth: 230]. At the same time, irony towards the organizers of dubious scientific events rhymes with self-irony in relation to himself as another “crown specialist” who composes a certain literary opus in response to the “flattering request” of the creators of an authoritative book review (the essay was a response to the appeal of the editors of New York Times Book Review” to a number of well-known authors to write texts dedicated to one of the deadly sins). So Pynchon inscribes himself in the circle of brothers in the literary workshop, whose opinion fellow citizens, paradoxically, both value and neglect.

..> with flattering requests - to speak at the Symposium on Problems of Sloth, to head the Commission on the Affairs of Sloth, to testify as an expert at the Hearings on the Question of Sloth” [On Sloth: 230]. At the same time, irony towards the organizers of dubious scientific events rhymes with self-irony in relation to himself as another “crown specialist” who composes a certain literary opus in response to the “flattering request” of the creators of an authoritative book review (the essay was a response to the appeal of the editors of New York Times Book Review” to a number of well-known authors to write texts dedicated to one of the deadly sins). So Pynchon inscribes himself in the circle of brothers in the literary workshop, whose opinion fellow citizens, paradoxically, both value and neglect.

Such an attitude of society towards writers is already emphasized at the beginning of the essay, thanks to the introduction of an anecdotal discourse that reproduces “a conversation on some medieval death row” between a robber accused of the sin of anger and a writer - “of these, that under the article “Indolence”” [O Sloth: 230]. Considering then "Sloth as a theme of literary works", Pynchon again plays on the ironically condescending attitude of society towards the writer, likening the great Melville to his hero, the scribe Bartleby ("miserable scrivener - this writer!"14, which

Considering then "Sloth as a theme of literary works", Pynchon again plays on the ironically condescending attitude of society towards the writer, likening the great Melville to his hero, the scribe Bartleby ("miserable scrivener - this writer!"14, which

in the Russian translation is strengthened by the use of a diminutive suffix: “because of what a miserable clerk! - or, translating into real life, because of some writer Melville! [On Sloth: 232].

Correlating the transformation in the perception of Lenosti from the Middle Ages to the 20th century with changes in attitudes towards writing, which turned from a “cognitive excursion into the country of mortal sin” into a profession capable of bringing “quite real cash income” [On Lenosti: 230-231], Pynchon offers a kind of apology for this activity: “It is in such moments of their mental wanderings that writers create successful, sometimes even their best things: they find the key to the problems of form, receive advice from the World of Ideas, undergo adventures in the zone between sleep and awakening - sometimes they even manages to remember later. Idle dreams often make up the very essence of our professional activity” [O Lenosti: 231]. However, appealing to the values that have legal power in a state based on the principles of "shark" capitalism, the author frankly ironizes the pragmatic-evaluative approach to art rooted in American society: "We trade in our dreams. Thus, Lenost brings quite real cash incomes” [On Lenosti: 231].

Idle dreams often make up the very essence of our professional activity” [O Lenosti: 231]. However, appealing to the values that have legal power in a state based on the principles of "shark" capitalism, the author frankly ironizes the pragmatic-evaluative approach to art rooted in American society: "We trade in our dreams. Thus, Lenost brings quite real cash incomes” [On Lenosti: 231].

In an effort to defend his right to engage in creativity without regard to the laws of the literary market, rejecting the “mechanism of turning dreams into money” characteristic of the modern media environment [On Sloth: 232], Pynchon implicitly defends his own position in the field of literature. At the same time, the feeling of the uniqueness of the position occupied does not prevent the author of the essay from not only uniting himself with other representatives of his profession, but also not separating himself from the “broad readership” [O Lenosti: 230-232]. It is no coincidence that, illustrating reasoning about an abstract concept, the author constantly appeals to everyday experience that connects the author and his audience [On Sloth: 230, 232, 233]. Such a narrative strategy, coupled with the use of rhetorical questions and direct appeals to the reader, makes it possible to expand the zone of communicative interaction with the recipient, who is aware of the significance of the statements addressed to him, including thanks to the atmosphere created around the name of the author, who rarely breaks his legendary silence. All this allows Pynchon to attract the sympathetic attention of the widest readership to his essay and, as a result, help in the realization of the author's leading intention - to convince the reader of the need to "take seriously our spiritual health" [On Lenosti: 233].

Such a narrative strategy, coupled with the use of rhetorical questions and direct appeals to the reader, makes it possible to expand the zone of communicative interaction with the recipient, who is aware of the significance of the statements addressed to him, including thanks to the atmosphere created around the name of the author, who rarely breaks his legendary silence. All this allows Pynchon to attract the sympathetic attention of the widest readership to his essay and, as a result, help in the realization of the author's leading intention - to convince the reader of the need to "take seriously our spiritual health" [On Lenosti: 233].

The essay on Sloth is a rather rare example for its author of a direct statement on the question of the writer's place in modern society. Turning to the genre of public speaking in support of fellow writers Salman Rushdie (1989) and Ian McEwan (2006), representing a kind of “act of prophetic denunciation”15, Pynchon uses the opportunity to speak directly about the specifics of the relationship between the writer and society, implicitly designating his own place in literary field.

In both cases, Pynchon's speeches are not distinguished by verbosity, but, inscribed in the context of similar speeches by other eminent writers, they acquire the weight of a serious literary document, the fact of inclusion in the world writers' community.

Rushdie's defense is a message addressed directly to the creator of The Satanic Verses (1989), who was persecuted by Islamic fundamentalists and forced into hiding for almost 10 years. Personal addressing makes appropriate a warm tone (“we pray for your good health, safety and lightness of spirit”) and words of gratitude for an example of spiritual fearlessness. At the same time, Pynchon simultaneously opposes himself and the authors close to him, inferior to Rushdie in courage and wisdom, but, thanks to the British author, gaining the strength to become “heretics” and resist such “sworn enemies” of any writer as power and stupidity16.

A more detailed statement in support of a writer close in artistic settings appears in connection with the accusation of British writer Ian McEwan of plagiarism in writing the historical novel Atonement (Atonement, 2001), nominated in 2006 for the Booker Prize. Already in the first sentences of his speech, Pynchon reinforces the authority of the "British genius" with brilliant examples illustrating the uniqueness of McEwan's writing gift. further, as in the case of Rushdie, inscribing himself in a kind of “imaginary community” (this time, instead of a community of “heretic” writers, it is a group of “creators of historical prose”), Pynchon actually takes the accusations against one of the members of this community and proves the legitimacy of the "traditional way" of creating fiction on a historical theme - the use of a wide range of documentary materials and eyewitness accounts. Moreover, this use of documentary material in a different format - the format of fiction - allows, according to Pynchon, to make available important historical knowledge - in this case, evidence of the "tragedy and heroism" of World War II - to the widest possible audience. such an act, Pynchon assures readers, deserves “not our scolding, but our gratitude.”17

Already in the first sentences of his speech, Pynchon reinforces the authority of the "British genius" with brilliant examples illustrating the uniqueness of McEwan's writing gift. further, as in the case of Rushdie, inscribing himself in a kind of “imaginary community” (this time, instead of a community of “heretic” writers, it is a group of “creators of historical prose”), Pynchon actually takes the accusations against one of the members of this community and proves the legitimacy of the "traditional way" of creating fiction on a historical theme - the use of a wide range of documentary materials and eyewitness accounts. Moreover, this use of documentary material in a different format - the format of fiction - allows, according to Pynchon, to make available important historical knowledge - in this case, evidence of the "tragedy and heroism" of World War II - to the widest possible audience. such an act, Pynchon assures readers, deserves “not our scolding, but our gratitude.”17

thus, appealing to the authority of a long tradition of creative processing of historical facts to create fiction (Pynchon quotes J. Ruskin in this regard), emphasizing the unique talent of I. McEwan and relying on the support of the community of historical prose creators, to which he refers himself , the author of the speech boldly defends his views on one of the delicate problems of literary work - the problem of plagiarism, which Pynchon had previously addressed in connection with his own work - in the autopreface to The Leisurely Apprentice18 and in a letter to the editor19.

Ruskin in this regard), emphasizing the unique talent of I. McEwan and relying on the support of the community of historical prose creators, to which he refers himself , the author of the speech boldly defends his views on one of the delicate problems of literary work - the problem of plagiarism, which Pynchon had previously addressed in connection with his own work - in the autopreface to The Leisurely Apprentice18 and in a letter to the editor19.

Concluding the analysis of Pynchon's non-fiction prose, we emphasize once again that this area of the writer's creative interests allows us to analyze various forms of author's self-reflection, among which of considerable interest are those directly addressed to the comprehension of the writer's place in the modern sociocultural space, the specifics of relationships with the readership and fellow writers . Considering non-fiction prose in relation to the facts of Pynchon's writing behavior, the researcher gets the opportunity to reconstruct the multidimensional "literary personality" of the cult author, get closer to the specifics of understanding his artistic work, as well as identify and fix the manifestations of various features of the institutionalization of the creator of postmodern prose during the period of transformation of the literary field.

Notes

1 Read more about Pynchon's transformation into the figure of "the most enigmatic American writer of our time" as a result of an inventive game with the models of writing behavior rooted in American culture and new patterns of behavior that are taking root in the space of the American literary market of the post-industrial era, was discussed in the article "Thomas Pynchon: Modeling a Cult Character in the Literary Field" (Vestnik Mosk. Univ. Ser. 9. Philology. 2007. No. 5).

2 Kipen D. Pynchon brings added currency to 'Nineteen Eighty-Four // Saturday. 2003. May 3 // www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2003/05/03/DD302378.DTL&type=printabl.

3 Pynchon's non-fiction works written in the first period of his work (1950s - early 1970s) were closely connected with the problems and poetics of the novels and short stories created during this period and were distinguished by a variety of themes and discourse (Pynchon Т. Togetherness // Aerospace Safety 1960 December. R. 6-8; Idem. A Journey into the Mind of Watts // The New York Times Magazine. l966. 12 Jun. P. 34-35, 78, 80-82, 84; Idem. The Gift: A Review of Oakley Hall's Warlock // Holiday. 1965 Vol. 38. No. 6. December. P. 164-165.

R. 6-8; Idem. A Journey into the Mind of Watts // The New York Times Magazine. l966. 12 Jun. P. 34-35, 78, 80-82, 84; Idem. The Gift: A Review of Oakley Hall's Warlock // Holiday. 1965 Vol. 38. No. 6. December. P. 164-165.

4 Pynchon T. Introduction // Farina R. Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me. Harmondsworth, 1983. P. V-XIV.

5 Pynchon T. Introduction to Jim Dodge's "Stone Junction" // www.themodernword. com/pynchon/pynchon_essays_stone.html

6 Pynchon T. "The Heart's Eternal Vow": Review of G. Garcia Marquez's "Love in the Time of Cholera" // New York Times Book Review. 1988. 10 April. P. 1, 47, 49.

7 Pynchon T. Introduction // Barthelme D. The Teachings of Don B. 1992. P. XV-XXII.

8 Pynchon T. Foreword // Orwell G. Nineteen Eighty-Four, 2003. P. I-XX.

9 Pynchon T. Introduction // Pynchon T. Slow Learner: Early stories. Boston; Toronto, 1984. P. 4.

10 Pynchon T. Liner Notes to Spiked! The Music of Spike Jones" (CD, 1994) // www. themodernword.com/pynchon/pynchon_essays_spiked.html; Idem. Liner Notes to Lotion's album "Nobody's Cool" (CD, 1995) // wwww.themodernword.com/pyn-chon/pynchon_essays_lotion.html

themodernword.com/pynchon/pynchon_essays_spiked.html; Idem. Liner Notes to Lotion's album "Nobody's Cool" (CD, 1995) // wwww.themodernword.com/pyn-chon/pynchon_essays_lotion.html

11 According to Pynchon's Autobiography, he wrote musical comedies as a teenager and wanted to become an opera librettist , and at twenty-two he applied for a scholarship to work on the libretto of a comic opera (Weisenburger S. Thomas Pynchon at Twenty-Two: A Recovered Autobiographical Sketch // American Literature. 1990 Vol. 62. No. 4. P. 693-694).

12 Pynchon T. Nearer, My Couch, to Thee // New York Times Book Review. 1993. 6 June. P. 3, 57. In Russian translation: Pynchon T. I reach out to You, O my Divan, to You...: Essay / Per. S. Silakova // Foreign Literature. 1996. No. 3. S. 230-233. Further references to the text of the essay will be given to this edition, indicating in square brackets next to the quote the title of the essay and the page number.

13 Pynchon T. Is It OK To Be a Luddite? // New York Times Book Review.