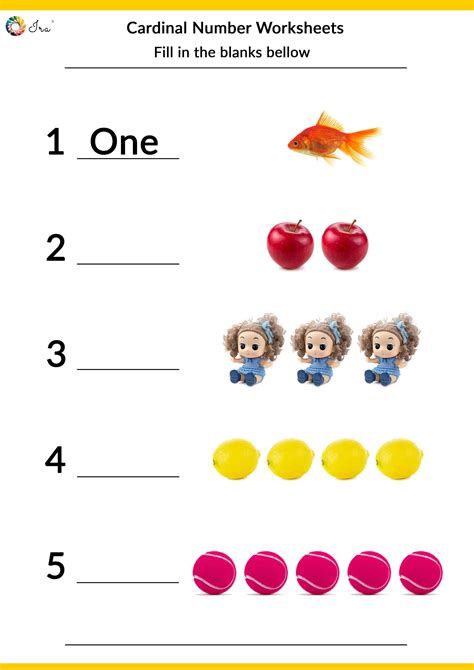

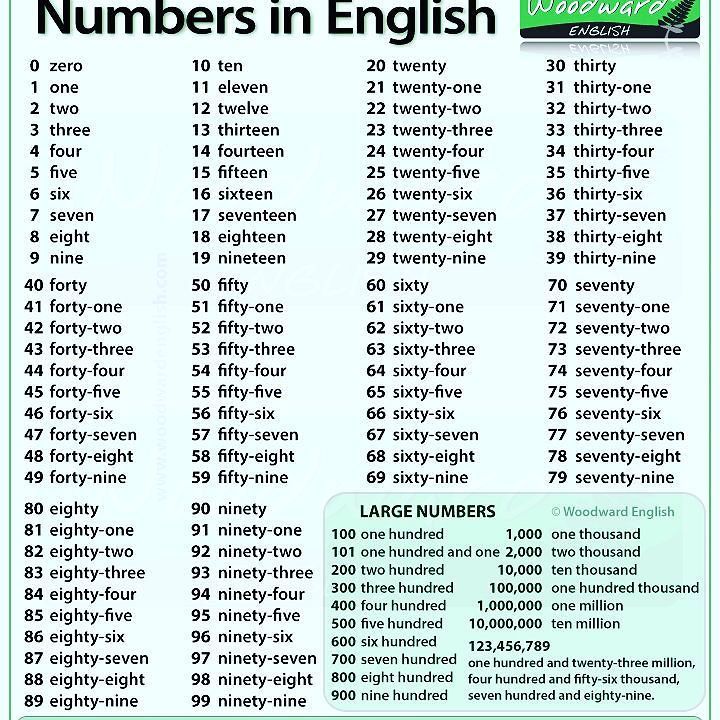

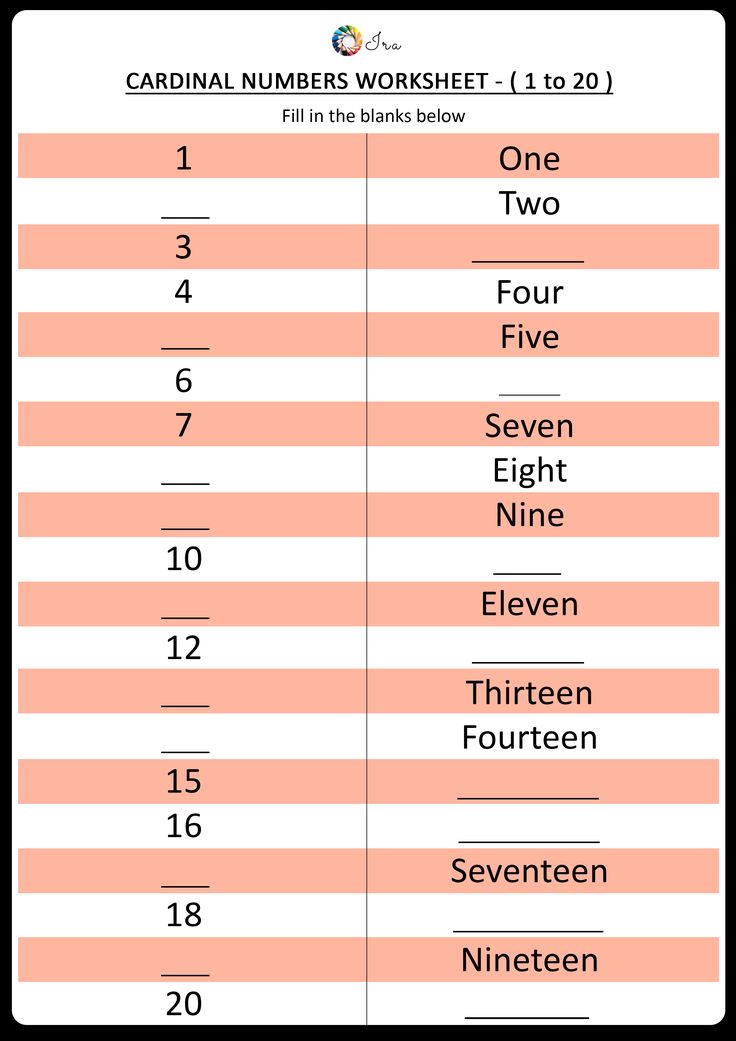

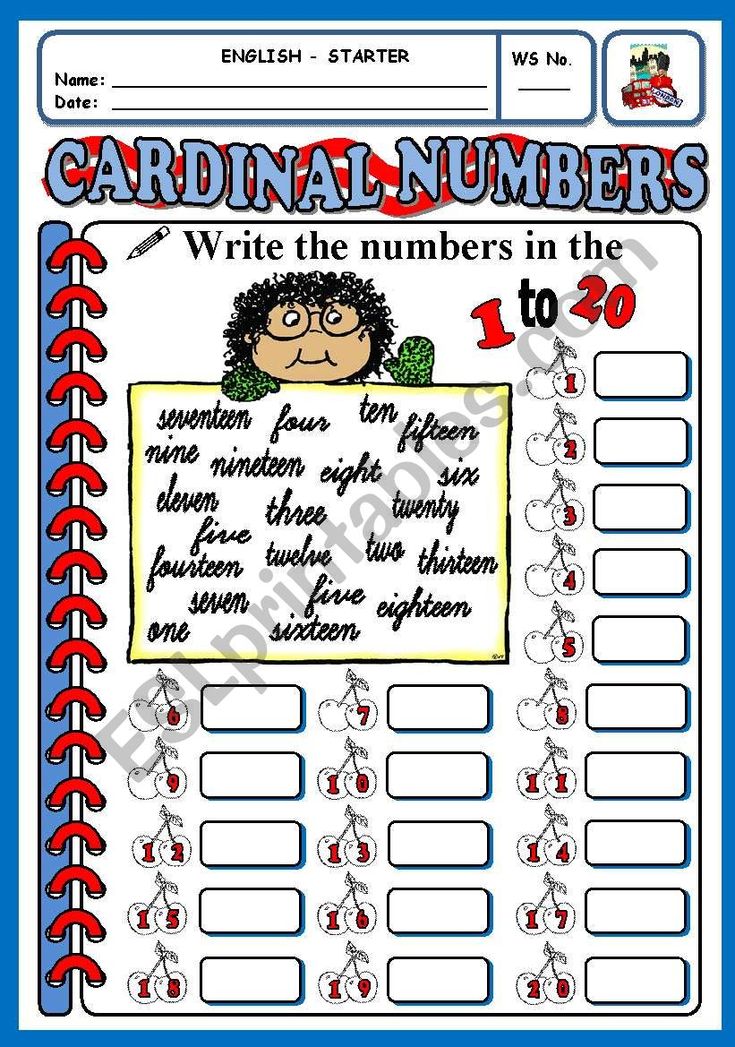

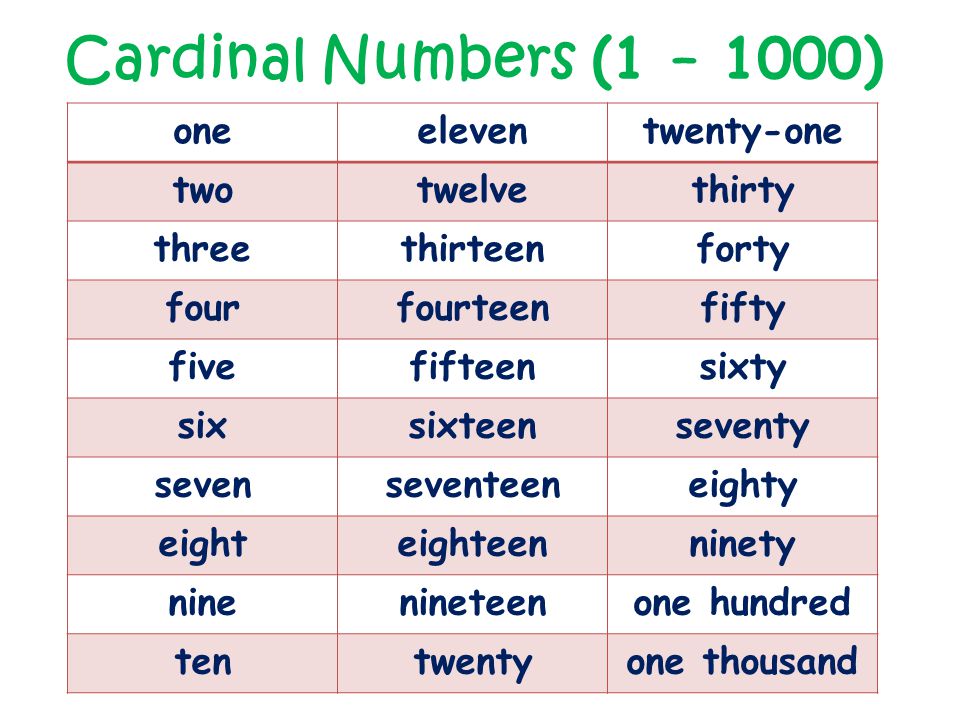

Number cardinals in english

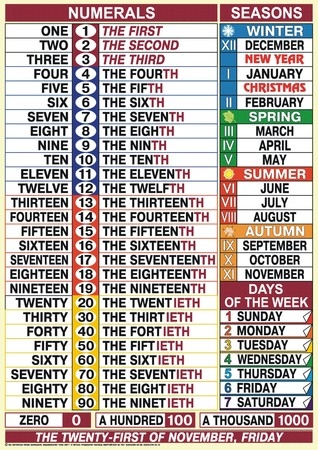

Cardinal and Ordinal Numbers Chart

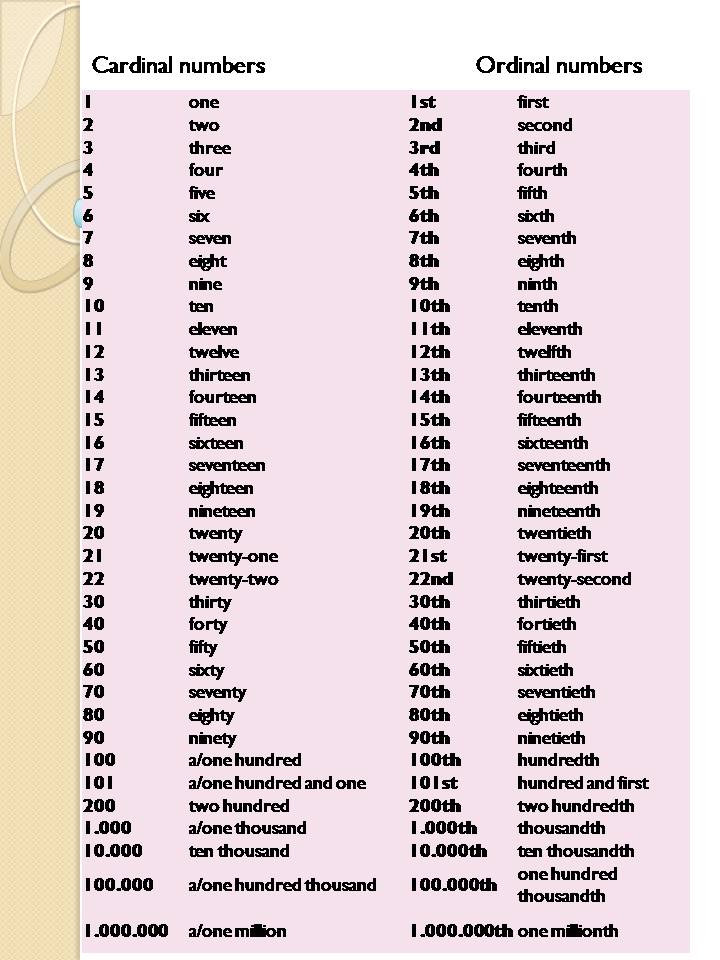

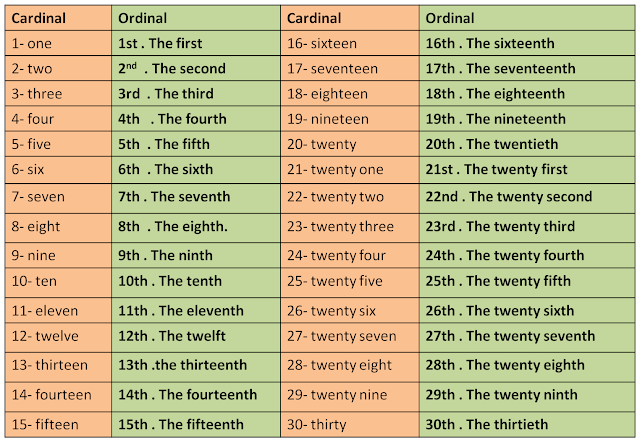

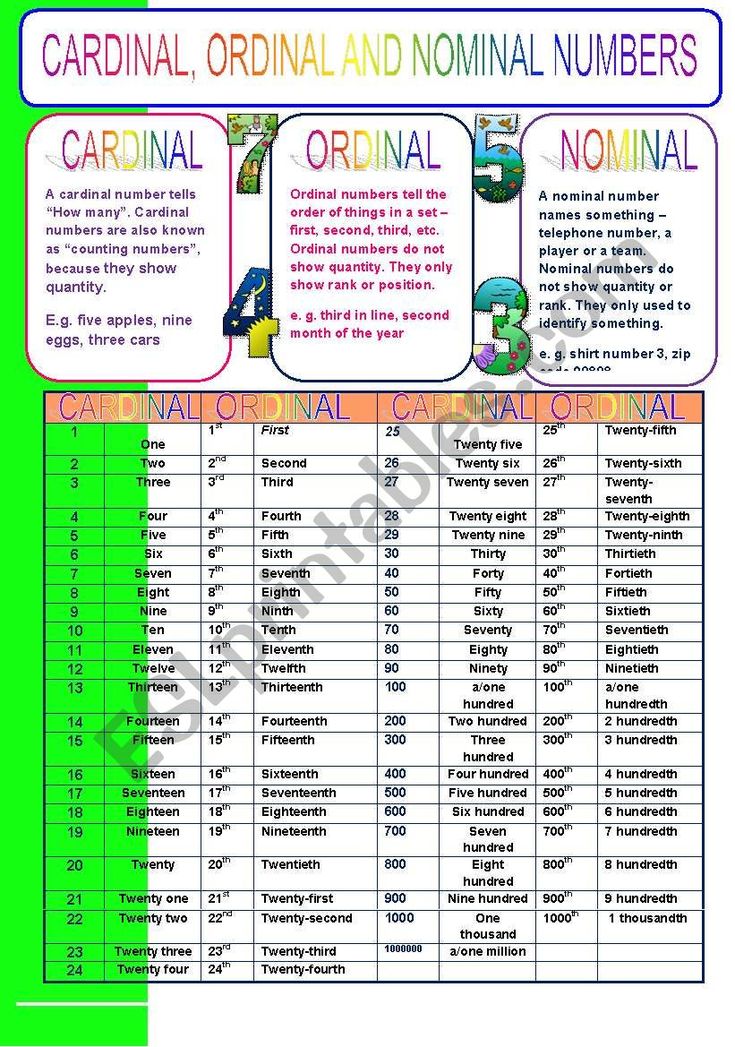

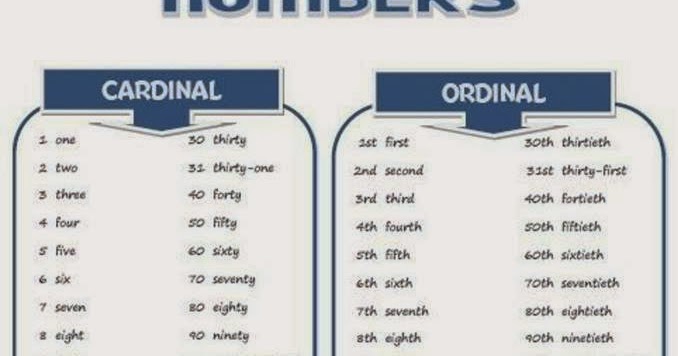

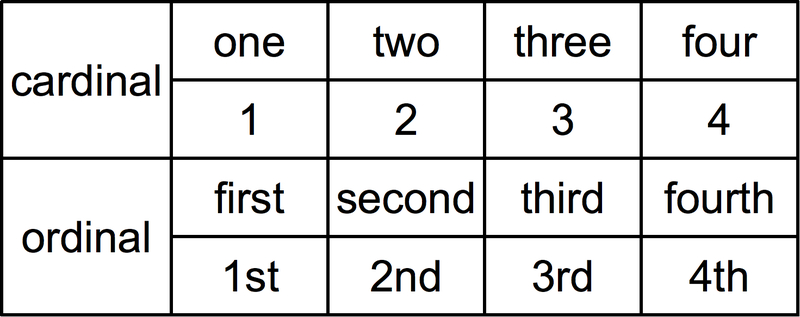

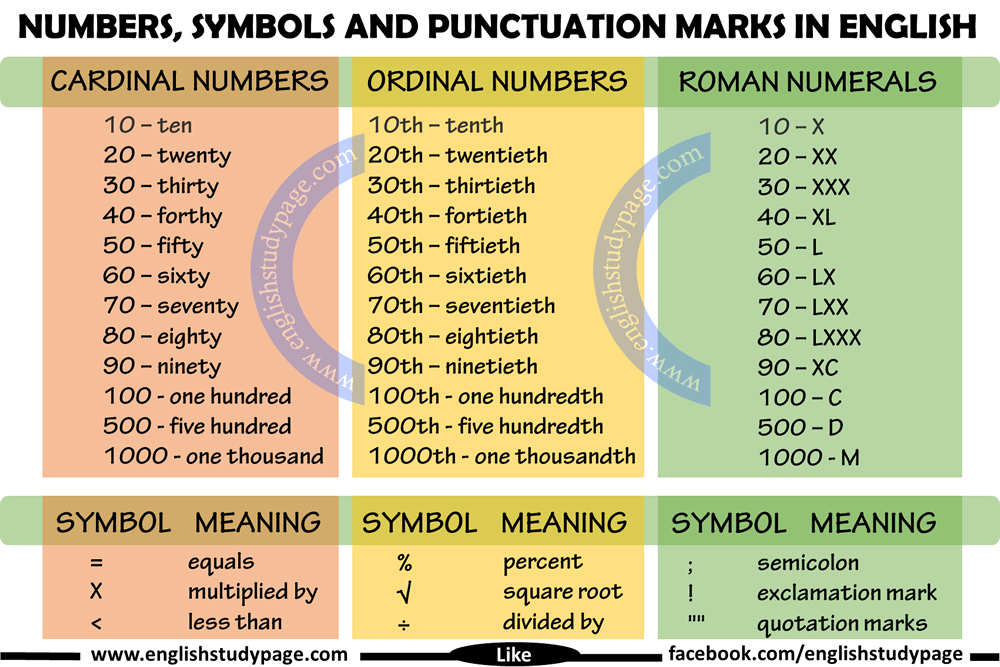

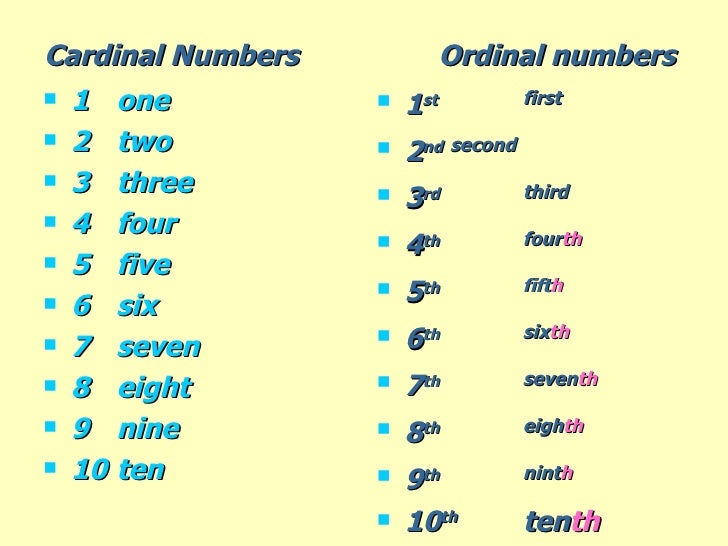

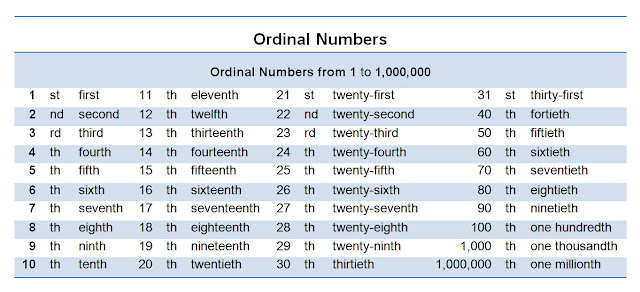

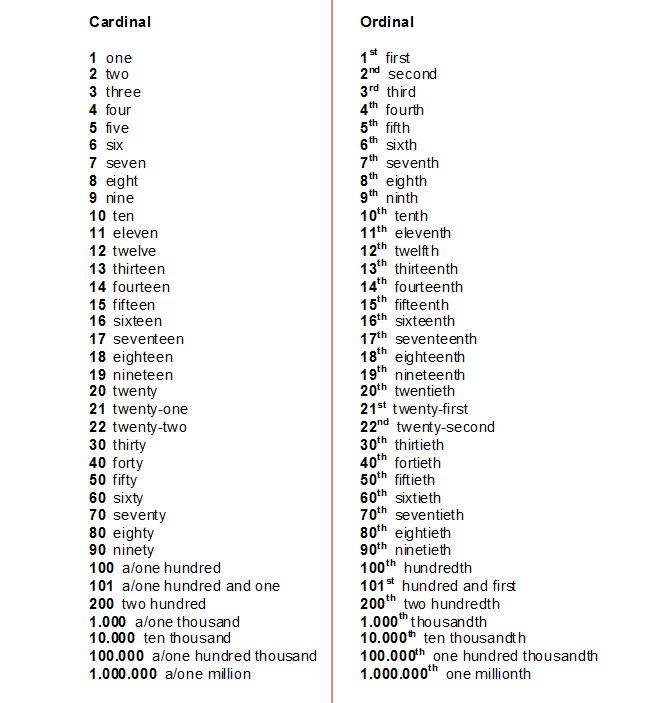

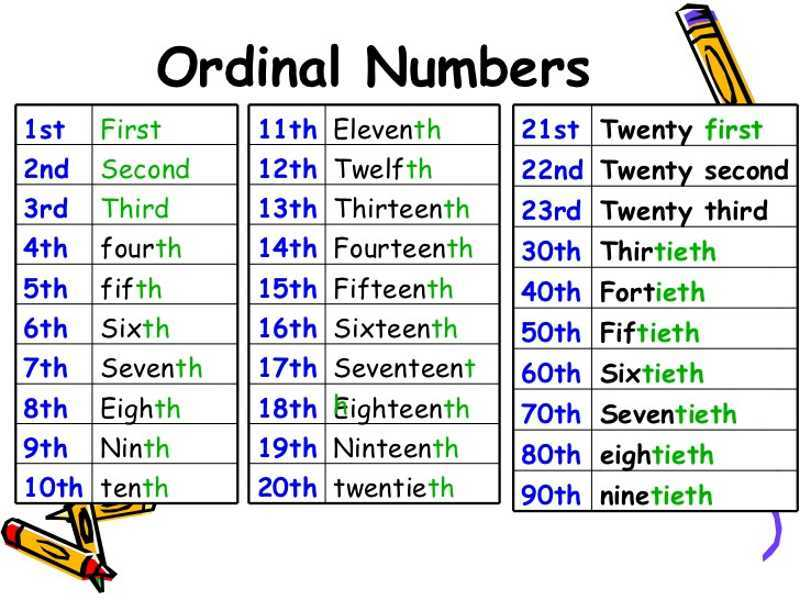

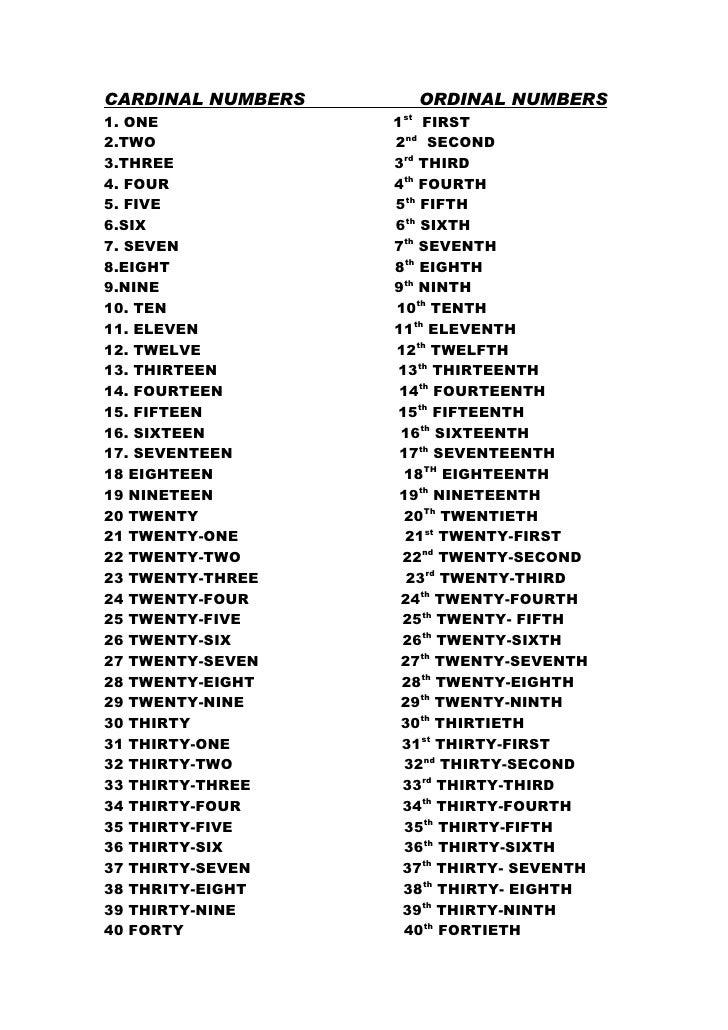

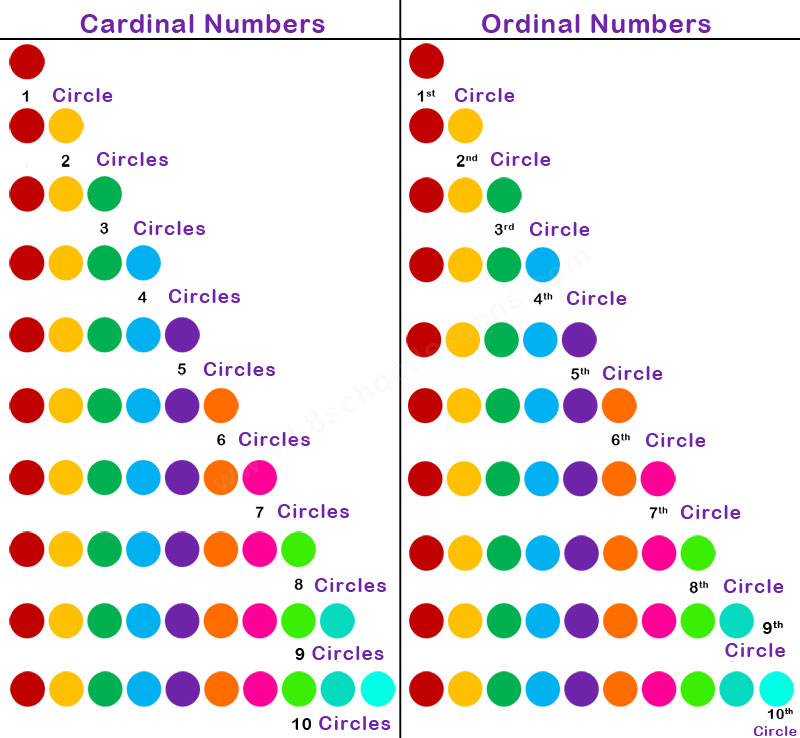

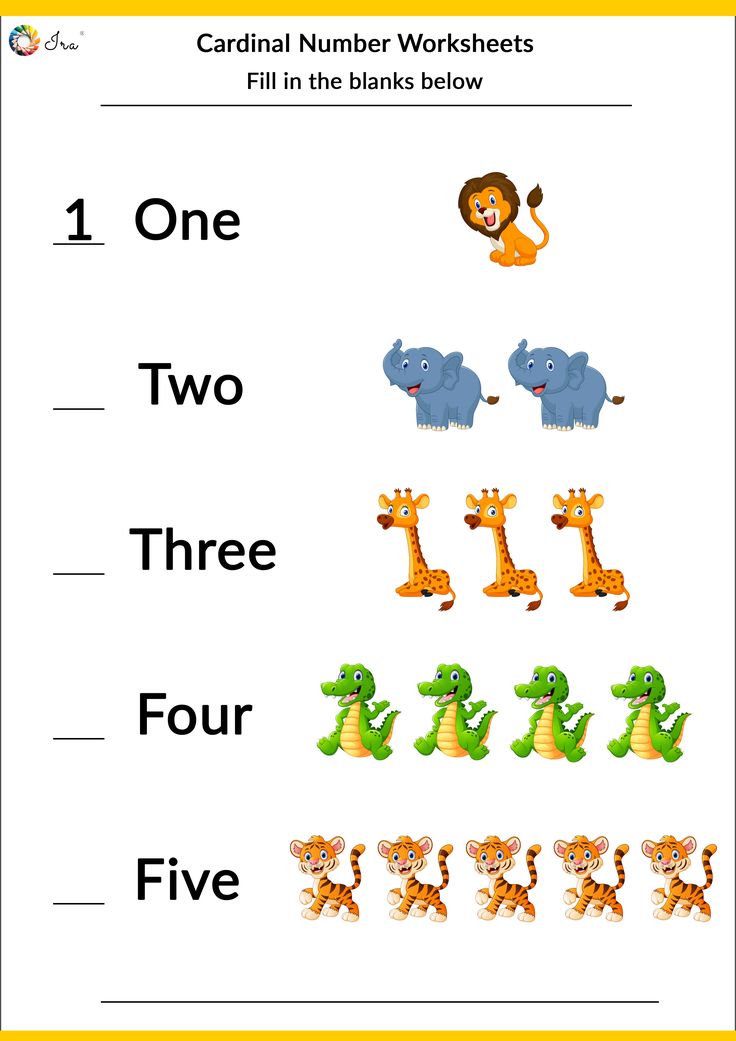

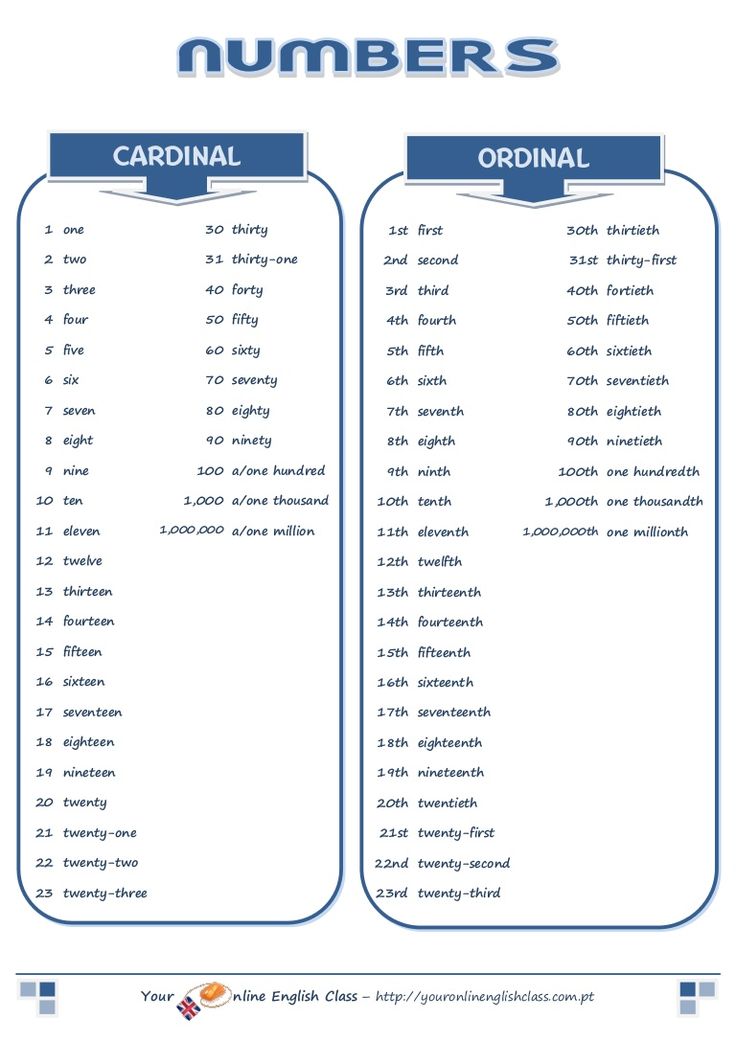

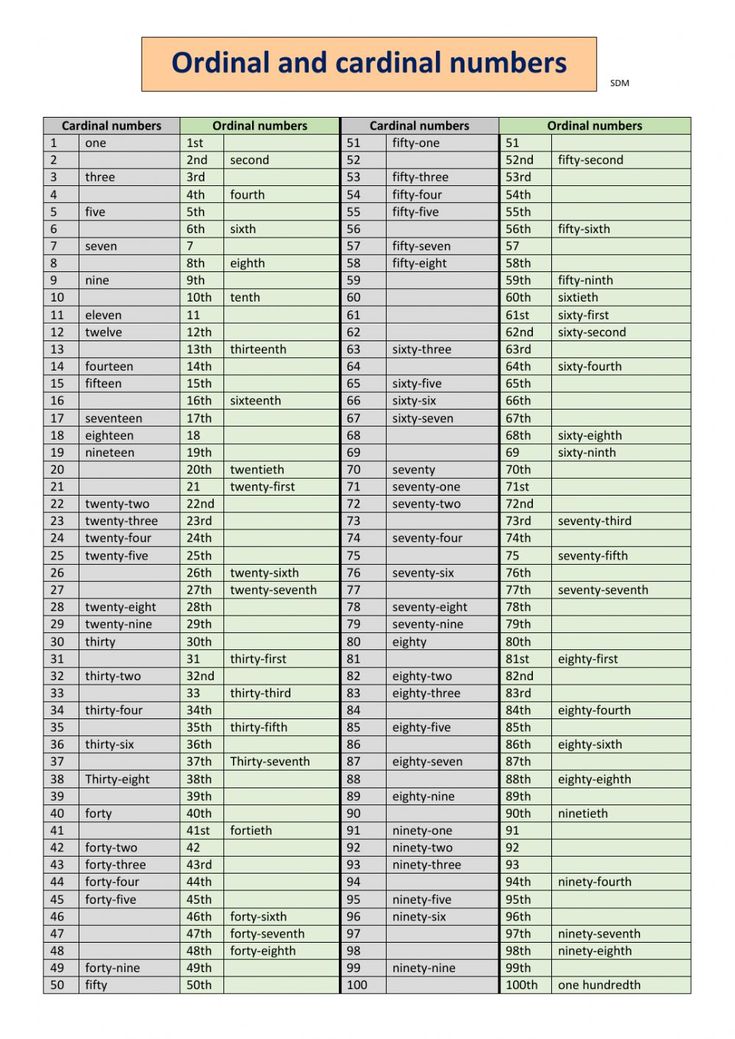

Cardinal and Ordinal Numbers ChartA Cardinal Number is a number that says how many of something there are, such as one, two, three, four, five.

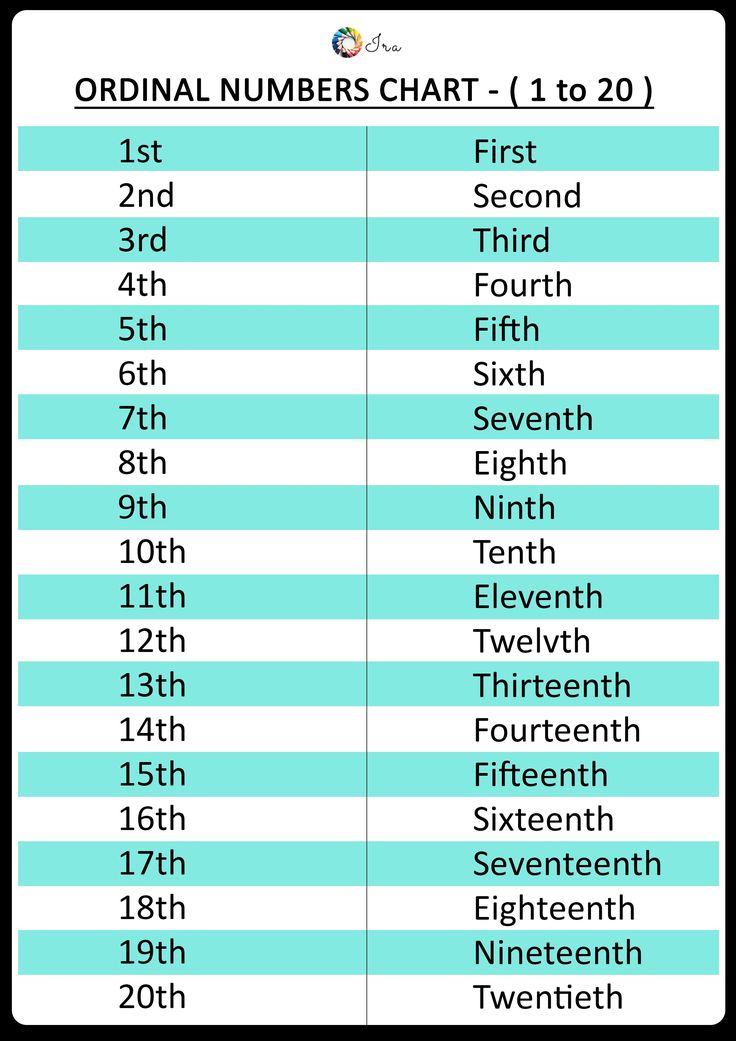

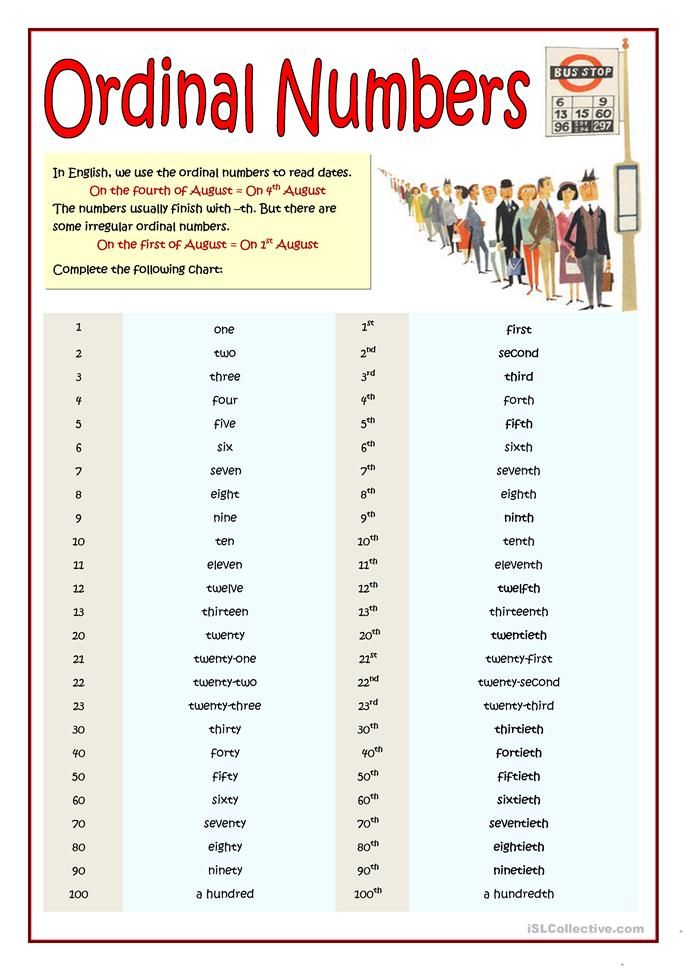

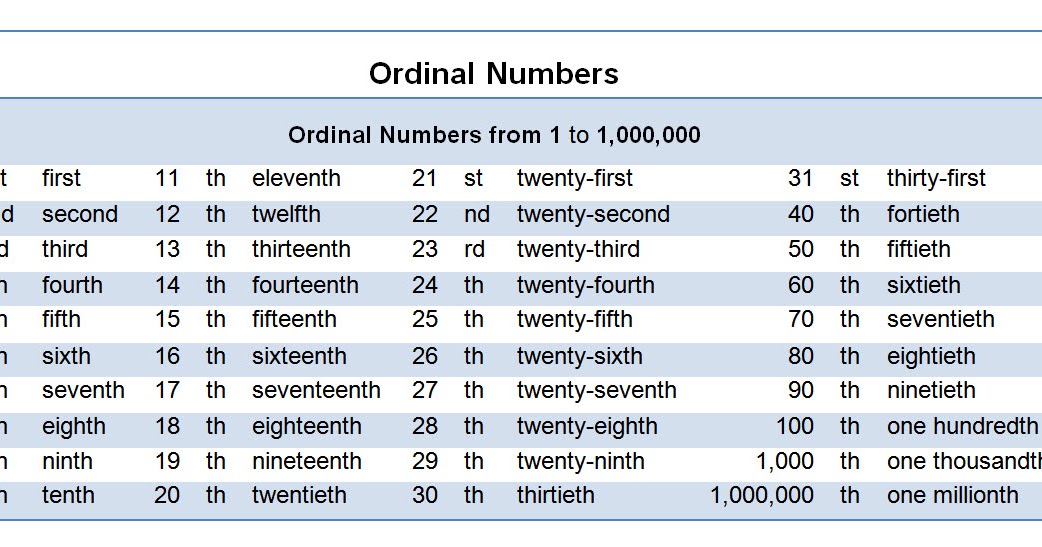

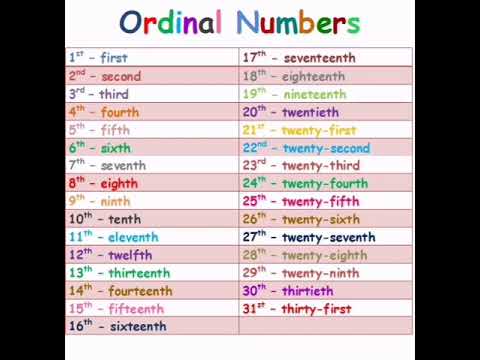

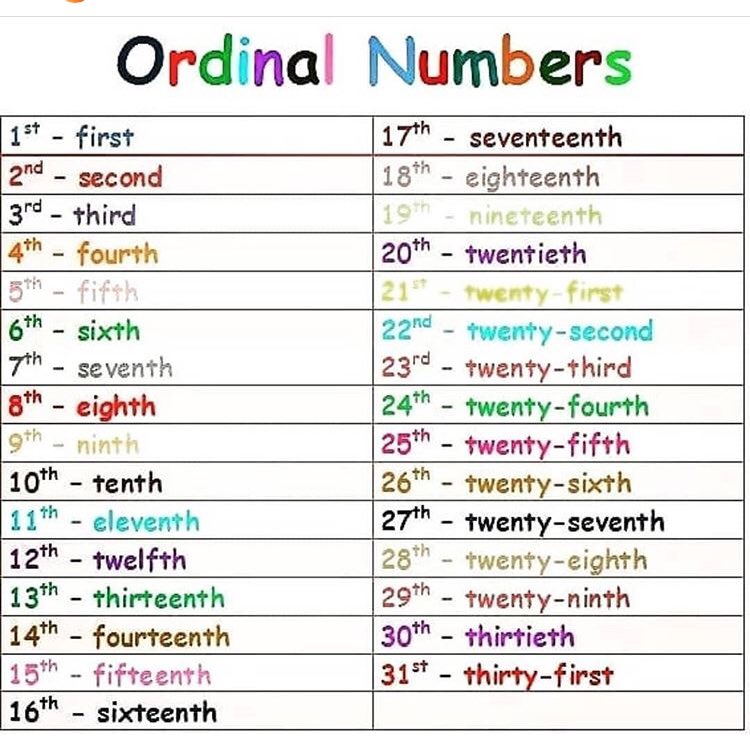

An Ordinal Number is a number that tells the position of something in a list, such as 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th etc.

Most ordinal numbers end in "th" except for:

- one ⇒ first (1st)

- two ⇒ second (2nd)

- three ⇒ third (3rd)

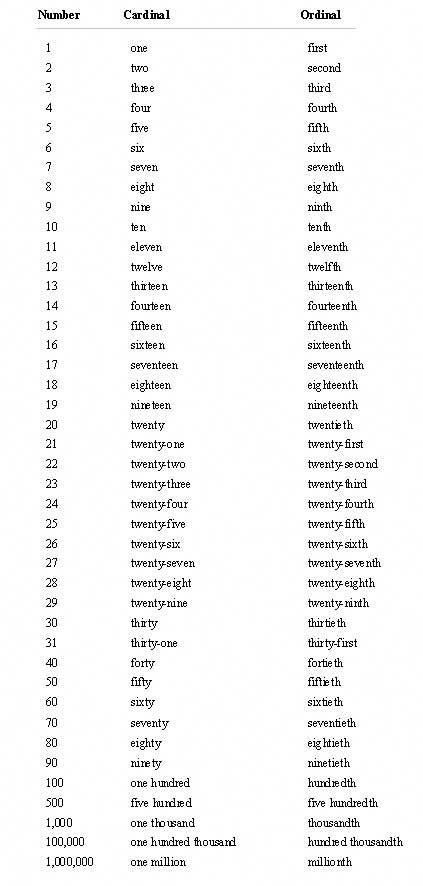

| Cardinal | Ordinal | |||

| 1 | One | 1st | First | |

| 2 | Two | 2nd | Second | |

| 3 | Three | 3rd | Third | |

| 4 | Four | 4th | Fourth | |

| 5 | Five | 5th | Fifth | |

| 6 | Six | 6th | Sixth | |

| 7 | Seven | 7th | Seventh | |

| 8 | Eight | 8th | Eighth | |

| 9 | Nine | 9th | Ninth | |

| 10 | Ten | 10th | Tenth | |

| 11 | Eleven | 11th | Eleventh | |

| 12 | Twelve | 12th | Twelfth | |

| 13 | Thirteen | 13th | Thirteenth | |

| 14 | Fourteen | 14th | Fourteenth | |

| 15 | Fifteen | 15th | Fifteenth | |

| 16 | Sixteen | 16th | Sixteenth | |

| 17 | Seventeen | 17th | Seventeenth | |

| 18 | Eighteen | 18th | Eighteenth | |

| 19 | Nineteen | 19th | Nineteenth | |

| 20 | Twenty | 20th | Twentieth | |

| 21 | Twenty one | 21st | Twenty-first | |

| 22 | Twenty two | 22nd | Twenty-second | |

| 23 | Twenty three | 23rd | Twenty-third | |

| 24 | Twenty four | 24th | Twenty-fourth | |

| 25 | Twenty five | 25th | Twenty-fifth | |

| … | … | … | … | |

| 30 | Thirty | 30th | Thirtieth | |

| 31 | Thirty one | 31st | Thirty-first | |

| 32 | Thirty two | 32nd | Thirty-second | |

| 33 | Thirty three | 33rd | Thirty-third | |

| 34 | Thirty four | 34th | Thirty-fourth | |

| … | … | … | … | |

| 40 | Forty | 40th | Fortieth | |

| 50 | Fifty | 50th | Fiftieth | |

| 60 | Sixty | 60th | Sixtieth | |

| 70 | Seventy | 70th | Seventieth | |

| 80 | Eighty | 80th | Eightieth | |

| 90 | Ninety | 90th | Ninetieth | |

| 100 | One hundred | 100th | Hundredth | |

| … | … | … | … | |

| 1000 | One thousand | 1000th | Thousandth | |

Copyright © 2021 MathsIsFun. com

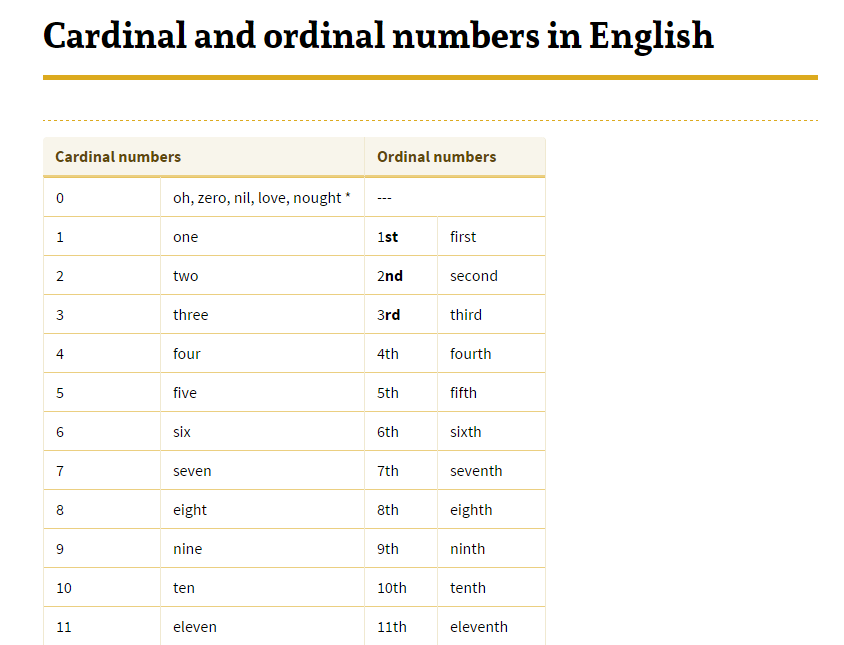

Cardinal and ordinal numbers in English

1. The numbers in English

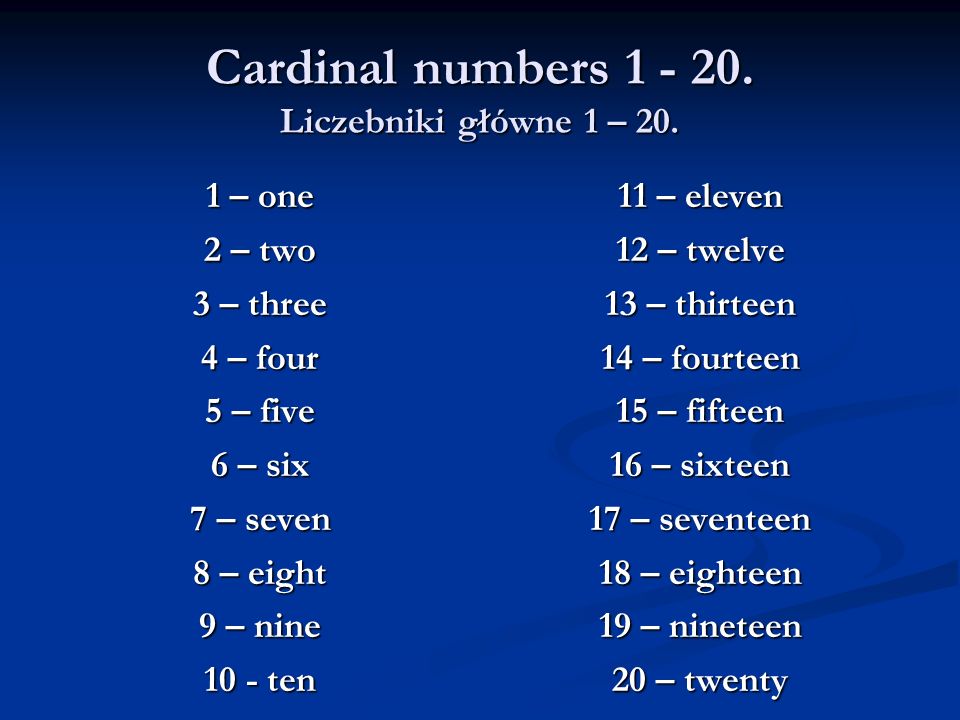

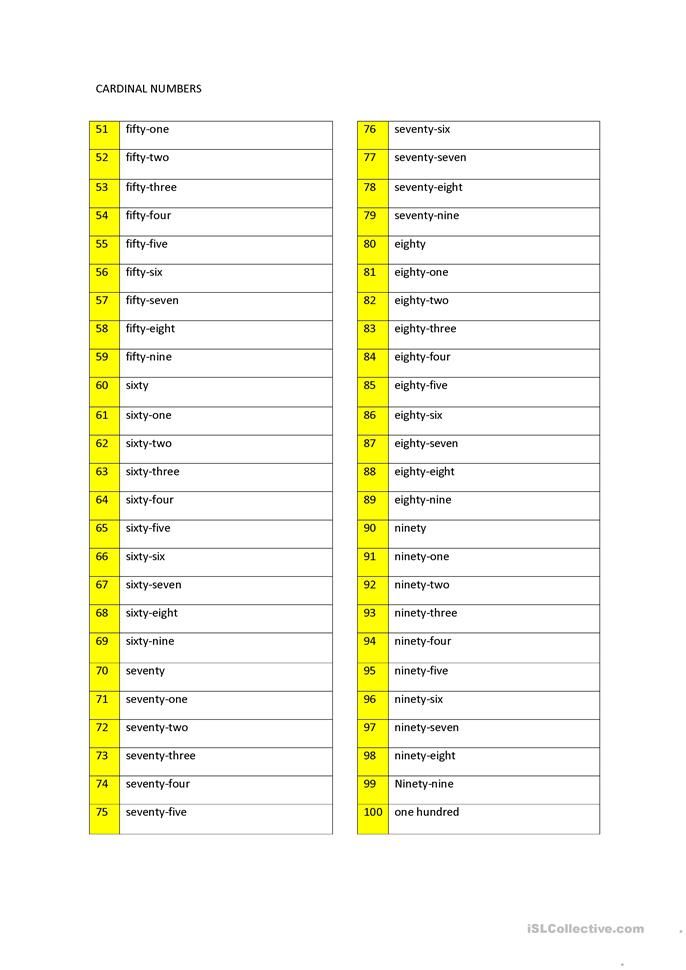

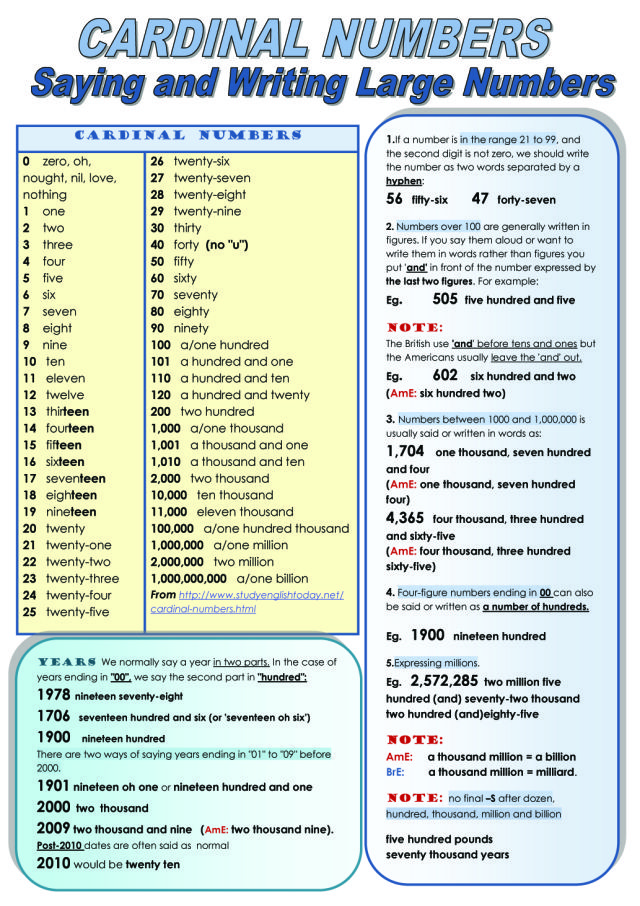

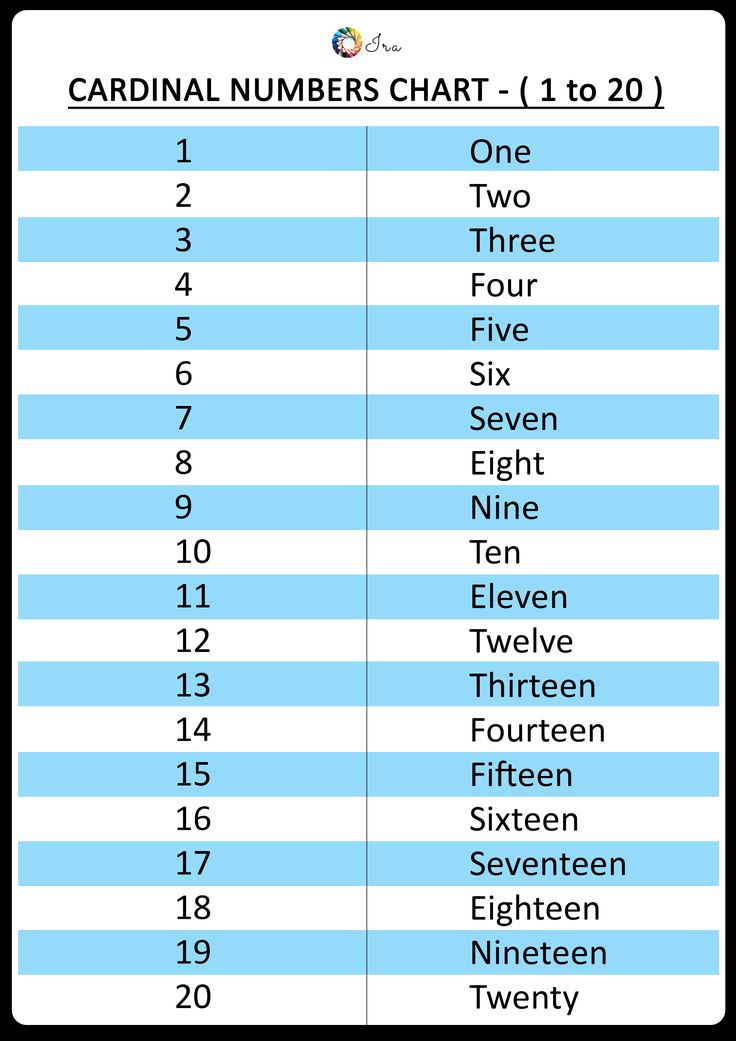

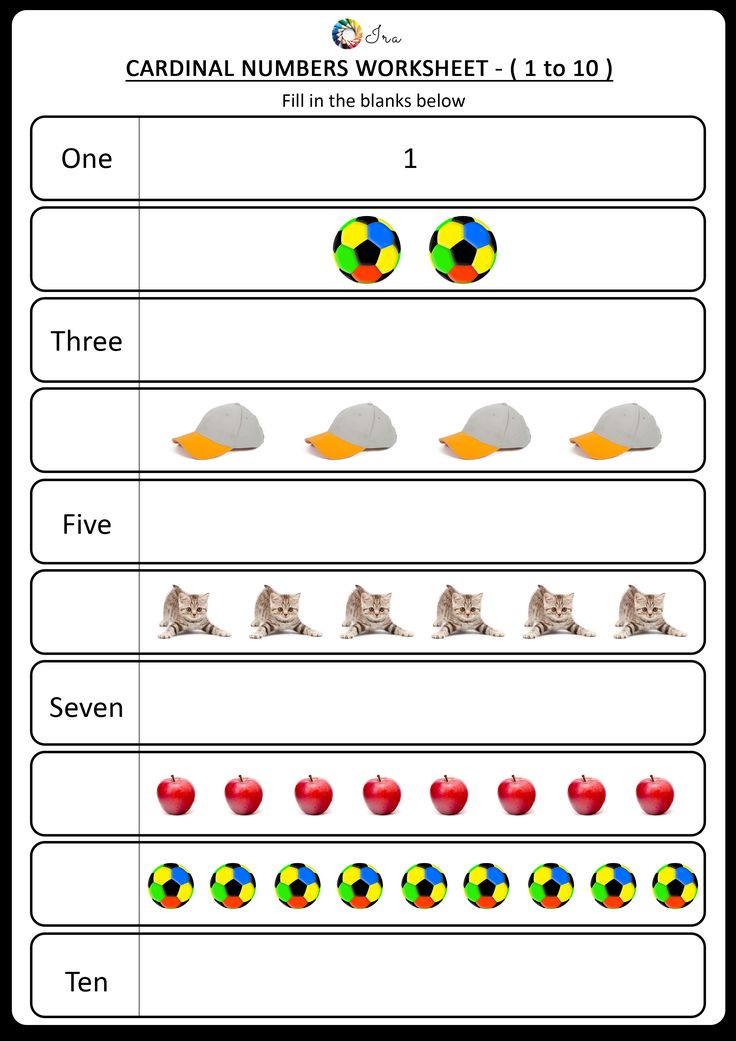

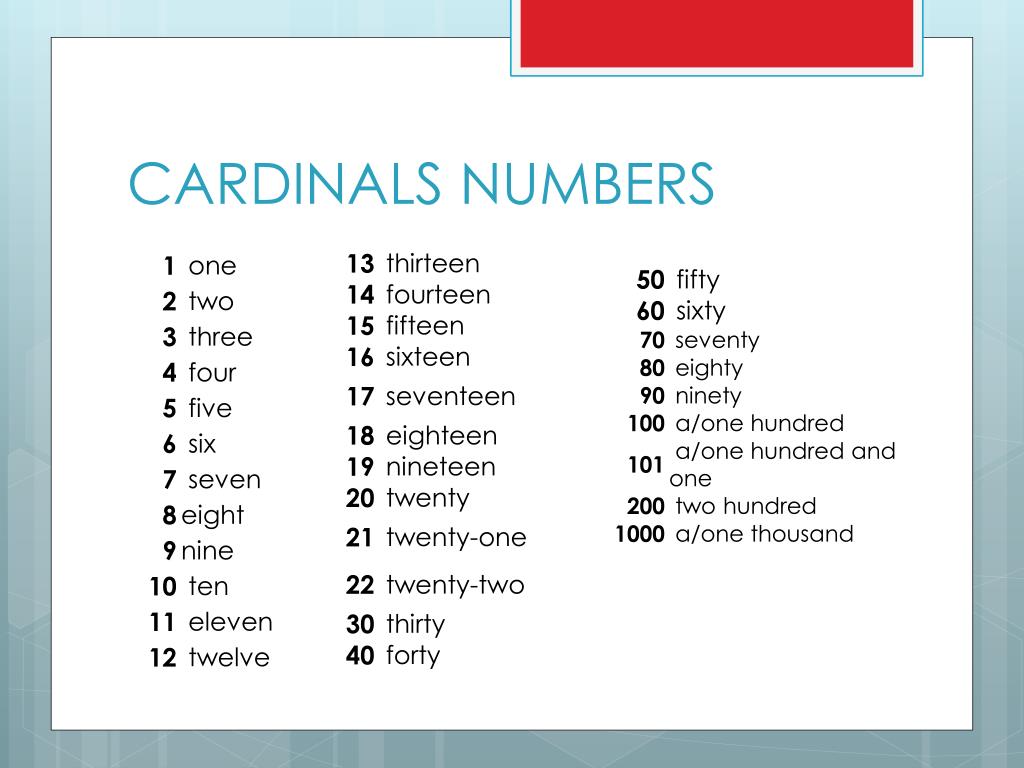

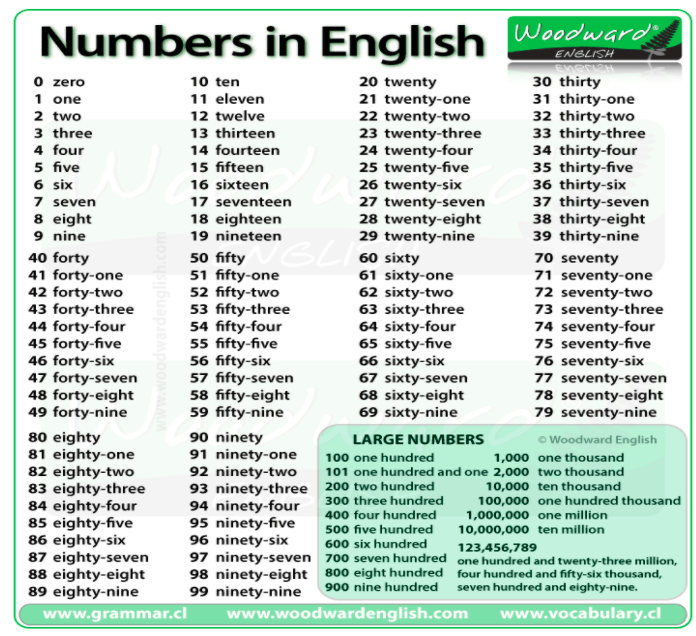

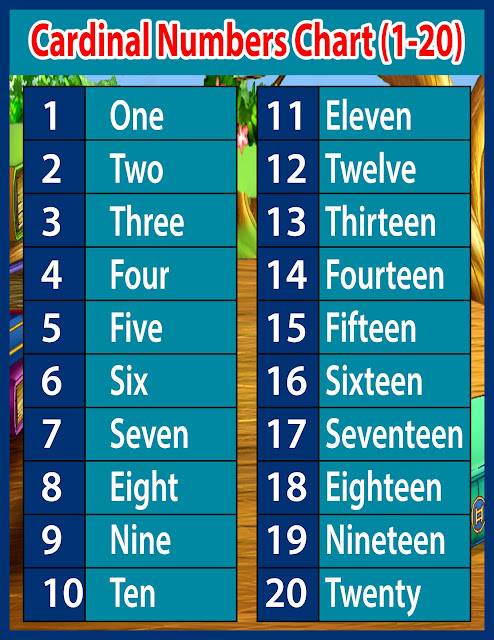

1.1. Cardinal numbers

Cardinal numbers say how many people or things there are.

Examples:

- There are five books on the desk.

- Ron is ten years old.

1.1.1. Numbers bigger than 20

Use a hyphen between compound numbers.

| Number | Word |

|---|---|

| 21 | twenty-one |

| 55 | fifty-five |

| 99 | ninety-nine |

1.1.2. Numbers bigger than 100

Use a hyphen between compound numbers and the word and.

Use either the definite article a or one for 100.

| Number | Word |

|---|---|

| 121 | a/one hundred and twenty-one |

| 356 | three hundred and fifty-six |

| 999 | nine hundred and ninety-nine |

In American English and is mostly not used.

1.1.3.Numbers bigger than 1,000

Use a hyphen between compound numbers and the word and.

Use either the definite article a or one for 1,000.

Separate three digits with a comma (,) → 50,000.

| Number | Word |

|---|---|

| 1,121 | a/one thousand and one hundred and twenty-one |

| 2,356 | two thousand and three hundred and fifty-six |

| 9,999 | nine thousand and nine hundred and ninety-nine |

| 305,234 | three hundred and five thousand and two hundred and thirty-four |

In American English and is mostly not used.

1.1.4. The number 0

There are different words for the number 0.

| Word | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| oh | single digits (telephone numbers, codes) | 67890 six - seven - eight - nine - oh |

| zero | measurements (temperature) | -5 °C five degrees Celsius below zero |

| nought | figure 0 in British English* | 5 - 5 = 0 Five minus five leaves nought.  |

| nil | results in sport | The match ended 2 - 0. The match ended two - nil. |

| love | tennis | 40 - 0 forty - love |

* In American English zero is used.

1.1.5. Year

see: The date and the year in English

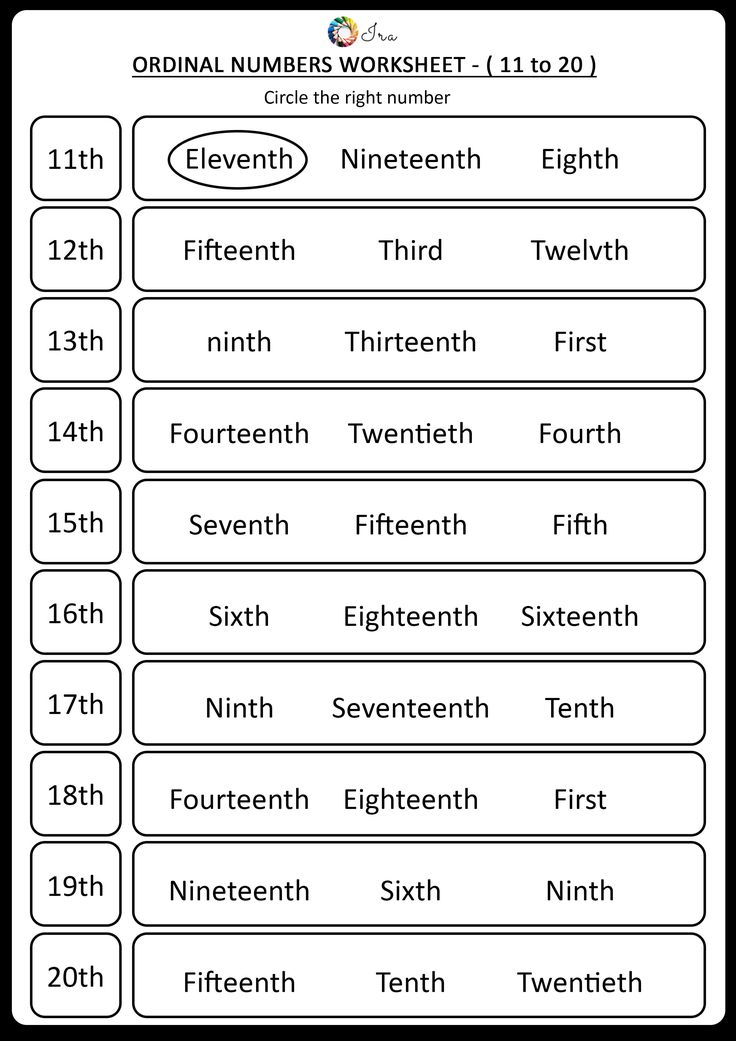

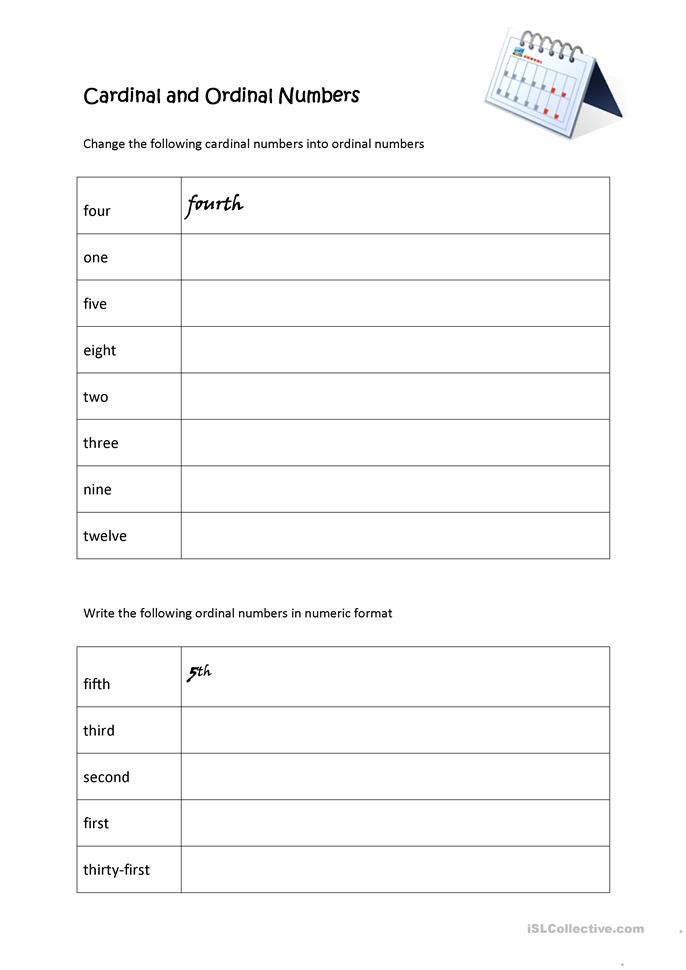

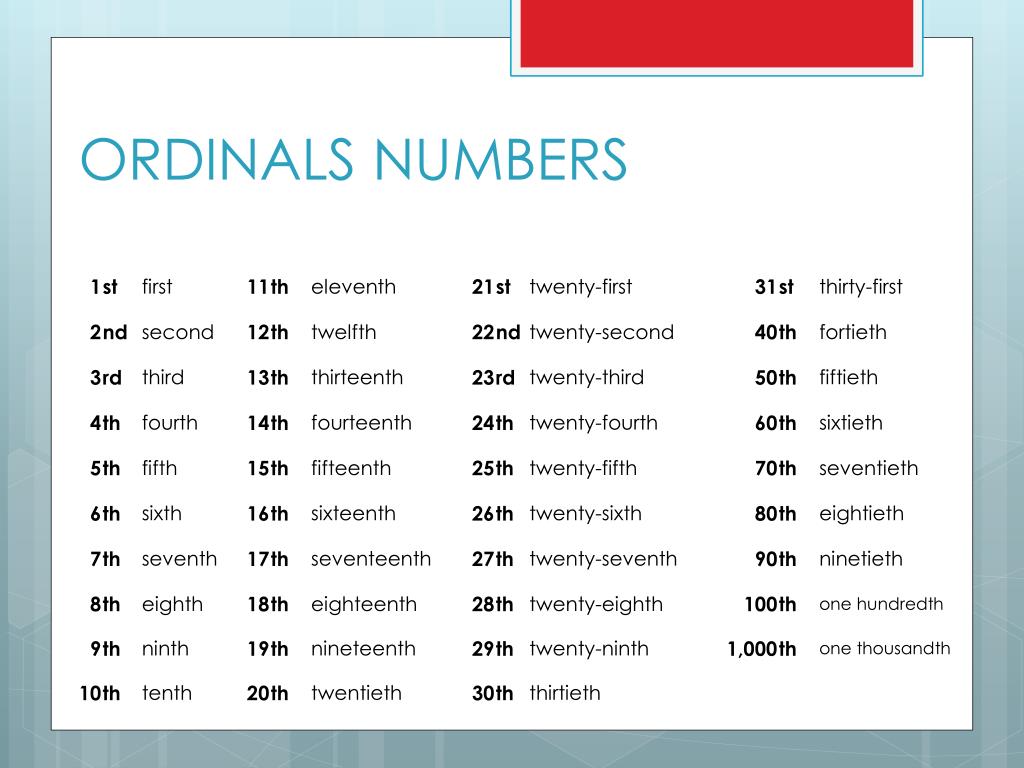

1.2. Ordinal numbers

Add th to the cardinal number to form the ordinal number: six → sixth

Add the last two letters of the written word to the figure. → 4th

Numbers in words: The ordinal numbers 1st → first, 2nd → second and 3rd → third are irregular. Be careful with the spelling of the words for 5th, 8th, 9th, 12th and the words ending in -y.

| Cardinal numbers | Ordinal numbers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | one | 1st | first |

| 2 | two | 2nd | second |

| 3 | three | 3rd | third |

| 5 | five | 5th | fifth |

| 8 | eight | 8th | eighth |

| 9 | nine | 9th | ninth |

| 12 | twelve | 12th | twelfth |

| 20 | twenty | 20th | twentieth |

| Ordinal numbers | |

|---|---|

| 21st | twenty-first |

| 22nd | twenty-second |

| 23rd | twenty-third |

| 24th | twenty-fourth |

| 25th | twenty-fifth |

| 26th | twenty-sixth |

| 27th | twenty-seventh |

| 28th | twenty-eighth |

| 29th | twenty-ninth |

| 30th | thirtieth |

| 31st | thirty-first |

1.

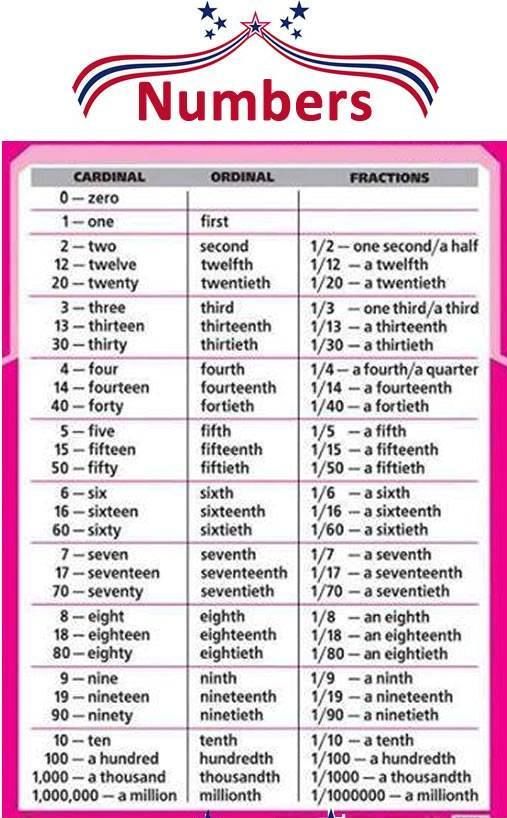

3. Fractions and decimals

3. Fractions and decimals1.3.1. Fractions

Use the ordinal number for the denominator:

- 1/3 → one third

- 2 3/5 → two and three fifths

Exceptions:

- 1/2 → one half

- 1/4 → one quarter

1.3.2. Decimals

Use the cardinal number for decimals:

- 3.8 → three point eight

- 4.25 → four point two five

1.4. Roman numbers

Roman numbers are seldom used. They are used for the names of kings and queens. Use the ordinal number:

- Elisabeth II → Elisabeth the Second

- Louis XIV → Louis the Fourteenth

2. The numbers in a table

| Cardinal numbers | Ordinal numbers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | oh, zero, nil, love, nought | --- | |

| 1 | one | 1st | first |

| 2 | two | 2nd | second |

| 3 | three | 3rd | third |

| 4 | four | 4th | fourth |

| 5 | five | 5th | fifth |

| 6 | six | 6th | sixth |

| 7 | seven | 7th | seventh |

| 8 | eight | 8th | eighth |

| 9 | nine | 9th | ninth |

| 10 | ten | 10th | tenth |

| 11 | eleven | 11th | eleventh |

| 12 | twelve | 12th | twelfth |

| 13 | thirteen | 13th | thirteenth |

| 14 | fourteen | 14th | fourteenth |

| 15 | fifteen | 15th | fifteenth |

| 16 | sixteen | 16th | sixteenth |

| 17 | seventeen | 17th | seventeenth |

| 18 | eighteen | 18th | eighteenth |

| 19 | nineteen | 19th | nineteenth |

| 20 | twenty | 20th | twentieth |

| 21 | twenty-one | 21st | twenty-first |

| 22 | twenty-two | 22nd | twenty-second |

| 23 | twenty-three | 23rd | twenty-third |

| 24 | twenty-four | 24th | twenty-fourth |

| 25 | twenty-five | 25th | twenty-fifth |

| 26 | twenty-six | 26th | twenty-sixth |

| 27 | twenty-seven | 27th | twenty-seventh |

| 28 | twenty-eight | 28th | twenty-eighth |

| 29 | twenty-nine | 29th | twenty-ninth |

| 30 | thirty | 30th | thirtieth |

| 31 | thirty-one | 31st | thirty-first |

| 40 | forty | ||

| 50 | fifty | ||

| 60 | sixty | ||

| 70 | seventy | ||

| 80 | eighty | ||

| 90 | ninety | ||

| 100 | a/one hundred | ||

| 1,000 | a/one thousand | ||

| 10,000 | ten thousand | ||

| 100,000 | a/one hundred thousand | ||

| 1,000,000 | a/one million | ||

| 1,000,000,000 | a/one billion | ||

Meaning, Definition, Suggestions .

What is a cardinal number

What is a cardinal number - Online translator

- Grammar

- Video lessons

- Textbooks

- Vocabulary

- Professionals

- English for tourists

- Abstracts

- Tests

- Dialogues

- English dictionaries

- Articles

- Biographies

- Feedback

- About project

Options | Examples

The meaning of the word "CARDINAL"

The most important, essential, basic.

See all meanings of the word CARDINAL

The meaning of the word "NUMBER"

See all meanings of NUMBER

Cardinal sentences

| The calendar era assigns a cardinal number to each successive year, using a point in the past as the beginning of the era. | |

| Other results | |

| The non-existence of a subset of real numbers with cardinality strictly between integers and real numbers is known as the continuum hypothesis. | |

| The principles concerned only the theory of sets, cardinal numbers, ordinal numbers and real numbers. | |

| Any set of cardinal numbers is well founded, which includes the set of natural numbers. | |

| Luganda's system of cardinal numbers is rather complicated. | |

| Each Aleph is the cardinality of some ordinal number. | |

| In modern Japanese, cardinal numbers are given on readings other than 4 and 7, which are called Yon and Nana, respectively. | |

| The cardinal numbers four and fourteen, when written as words, are always written with a u, as are the ordinal numbers four and fourteen. | |

| The old Swedish cardinal numbers look like this. | |

| Cardinal numbers can be inflexed, and some of the inflexed forms are irregular. | |

| Long ordinal numbers in Finnish are typed in much the same way as long cardinal numbers. | |

| Cardinal numbers refer to group size. | |

| To work with infinite sets, natural numbers have been generalized to ordinal and cardinal numbers. | |

| For finite sets, ordinal and cardinal numbers are identified with natural numbers. | |

| In the infinite case, many ordinal numbers correspond to the same cardinal number. | |

| For finite sets, ordinal and cardinal numbers are identified with natural numbers. | |

| In the infinite case, many ordinal numbers correspond to the same cardinal number. | |

| The practice of naming orthogonal networks with numbers and letters in the corresponding cardinal directions has been criticized by Camilo Sitte as unimaginative. | |

| Another area of study is the size of sets, which is described by cardinal numbers. | |

| Jack Valero of Catholic Voices said that by February the number of cardinal electors would likely drop. | |

| He said that usually the pope names as many cardinals as needed to bring the number of cardinal electors back to 120, and as many cardinals over the age of 80 as he wishes. | |

| I know how to dramatically increase the number of Zero supporters. | |

| By mid-December, their number had reached only 39, but by the end of the conclave five more cardinals had arrived. | |

| He was nominated by Cardinal Giraud and received a significant number of votes. | |

| The Synod was attended by 13 cardinal priests, one of whom was the future Pope Benedict V. An unknown number fled with Pope John XII. | |

| The number of homeless people has not changed dramatically, but the number of homeless families has increased, according to the HUD report. | |

| Forty percent of Catholics live in South America, but they are represented by a negligible number of cardinals. | |

| Several cardinals were not listed as members of these factions. | |

| Among the most ancient constellations are those that marked the four cardinal points of the year in the Middle Bronze Age, i.e. | |

”, as well as synonyms, antonyms and sentences, if available in our database. We strive to make the English-Grammar.Biz explanatory dictionary, including the interpretation of the phrase / expression "cardinal number", as correct and informative as possible. If you have suggestions or comments about the correctness of the definition of "cardinal number", please write to us in the "Feedback" section.

The image of Thomas Wolsey as interpreted by his contemporaries: “Ipse Rex” or a servant of Antichrist?

The article presents representations of the image of the English cardinal, minister and chancellor Thomas Wolsey by his compatriot contemporaries: J. Skelton, Polydor Virgil and W. Tyndel, for whom Wolsey is an example of an unrighteous political figure and vicious representative of the clergy. First of all, they note such negative qualities of the cardinal's personality as greed, greed, excessive ambition and hardness of heart. The works of these authors are full of expressive and evaluative judgments about the Chancellor, which led to the demonization of the image of Wolsey, firmly established in English historiography.

Tyndel, for whom Wolsey is an example of an unrighteous political figure and vicious representative of the clergy. First of all, they note such negative qualities of the cardinal's personality as greed, greed, excessive ambition and hardness of heart. The works of these authors are full of expressive and evaluative judgments about the Chancellor, which led to the demonization of the image of Wolsey, firmly established in English historiography.

Key words: Thomas Volsi , John Skeleton , Polydor Virgil , William Tyndel , Reformation , Italian wars

Kiryukhin D.V., Chugunova Tomasa Tomas Volsey in the interpretation of contemporaries "ipse rex" or a servant of the Antichrist? // Dialogue with time. 2017. Issue. 61. S. 51-67. https://roii.ru/r/1/61.4

Recently, interest in the study of life and creativity of prominent statesmen, whose service received mixed reviews by their contemporaries. For such figures also applies to the first minister of the English king Henry VIII, a cardinal and Chancellor Thomas Wolsey 1 (1472–1529). Life and work of Wolsey undeservedly deprived of the attention of Russian researchers 2 , while while Western historiography has dozens of works 3 , authors who are attributed by Volsey to a galaxy of prominent statesmen, determined the vector of development of England in the first third of the XVI century.

For such figures also applies to the first minister of the English king Henry VIII, a cardinal and Chancellor Thomas Wolsey 1 (1472–1529). Life and work of Wolsey undeservedly deprived of the attention of Russian researchers 2 , while while Western historiography has dozens of works 3 , authors who are attributed by Volsey to a galaxy of prominent statesmen, determined the vector of development of England in the first third of the XVI century.

Son of a prosperous butcher, cattle dealer and tavern owner in Ipswich, Thomas Wolsey had a brilliant career as a successful politician and the subject of heated discussions of his no less famous compatriots J. Skelton, Polydor Virgil and W. Tyndel 4 . each of them directly or indirect contact with Thomas Wolsey, and most often these relationships were far from friendly.

A detailed description of the life and public service Volsey compiled it clerk George Cavendish (1497–1562) 5 , showing the chancellor of England with this hero of his time. About those contemporaries of the English cardinal, whose judgments about him are the subject of this article, as well as about Volsey himself, dozens of works have been written (which cannot be said about the mentioned J. Cavendish). The life and career of Polydor Virgil has been studied in sufficient detail. thanks to D. Hay, who prepared one of the most complete editions of his major work on the history of England 6 and R. Hertel and J. Arnold 7 . The study of the literary heritage of Skelton was addressed many foreign researchers 8 , but only some of them (A. Kinney, G. Walker, I. Gordon, H. Edwards 9 ) attempted in part touch upon the problem of the poet's relationship with his contemporaries, mentioning the open confrontation between Volsey and Skelton, which found reflected in the works of the English poet.

About those contemporaries of the English cardinal, whose judgments about him are the subject of this article, as well as about Volsey himself, dozens of works have been written (which cannot be said about the mentioned J. Cavendish). The life and career of Polydor Virgil has been studied in sufficient detail. thanks to D. Hay, who prepared one of the most complete editions of his major work on the history of England 6 and R. Hertel and J. Arnold 7 . The study of the literary heritage of Skelton was addressed many foreign researchers 8 , but only some of them (A. Kinney, G. Walker, I. Gordon, H. Edwards 9 ) attempted in part touch upon the problem of the poet's relationship with his contemporaries, mentioning the open confrontation between Volsey and Skelton, which found reflected in the works of the English poet.

Foreign historiography about the translator of the Bible into English W. Tyndele also aims primarily (as in the case of Wolsey) to illuminate his life path and religious and political doctrines and almost no concerns the question of the views of two outstanding personalities of the same era (Wolsey and Tyndel) to the historical role of his opponent. Biographers of Tyndel R. Demaus, W. Moseley, D. Daniell and others point only to Volsey's activity to suppress the circulation of the English translation of the New Testament, carried out by the reformer 10 . All these studies do not to reconstruct the image of Cardinal Wolsey created by his contemporaries. Fill the lack of complex matching of image representations Volsey and this article is partly intended.

Biographers of Tyndel R. Demaus, W. Moseley, D. Daniell and others point only to Volsey's activity to suppress the circulation of the English translation of the New Testament, carried out by the reformer 10 . All these studies do not to reconstruct the image of Cardinal Wolsey created by his contemporaries. Fill the lack of complex matching of image representations Volsey and this article is partly intended.

Cardinal Volsey is one of the main characters in the XXVII book England "(" Anglica Historia ") by Polydor Virgil, work on compiling which he began about 1507 on behalf of King Henry VII. First 26 books were published in 1534 in Basel, the 27th book - in 1555 11 Polydor Virgil, like many others from the environment cardinal, at first he was also his admirer. The first break between them happened in 1513 when Volsey sent Polydorus Virgil to Rome to he, thanks to his eloquence, was able to convince the pope as soon as possible consecrate Volsey to the cardinal rank. However, at this meeting, Polydor Virgil, as Volsey later learned, spoke of the future cardinal a lot of hard-hitting 12 . At the beginning of 1515 the relationship was even greater aggravated: a letter from Polydorus Virgil to Rome was intercepted, in which he wrote sharply about Cardinal Wolsey and about the king himself, as a result of which April of the same year, the court historian was imprisoned in Tower of London. Of course, Polydor Virgil had many supporters - Pope Leo X himself stood up for him, writing about this to the king. Soon Polydor Virgil sent a letter to T. Volsey, in which pleaded for his forgiveness. Before Christmas 1515 courtier the author was released.

However, at this meeting, Polydor Virgil, as Volsey later learned, spoke of the future cardinal a lot of hard-hitting 12 . At the beginning of 1515 the relationship was even greater aggravated: a letter from Polydorus Virgil to Rome was intercepted, in which he wrote sharply about Cardinal Wolsey and about the king himself, as a result of which April of the same year, the court historian was imprisoned in Tower of London. Of course, Polydor Virgil had many supporters - Pope Leo X himself stood up for him, writing about this to the king. Soon Polydor Virgil sent a letter to T. Volsey, in which pleaded for his forgiveness. Before Christmas 1515 courtier the author was released.

According to researchers, J. Skelton also originally referred to Wolsey as a friend and patron, although criticism of the Chancellor is already contained in the poems of the poet in 1516. The most famous works Skelton, in which the figure of Volsey is in the center of attention, are three poems from the early 1520s: "Speak, parrot" ("Speke, Parott", 1521 g. ), “Colin Clout” (“Colin Clout”, 1522) and “Why are you not yard? ("Why Come Ye Not to Court?", 1522-1523). negative Wolsey deserved the attitude of the court poet not only thanks to some negative qualities of his character, but also because of his opposition to Skelton's patron, Thomas Howard (1473–1554), the third Duke of Norfolk. However, one should not forget, as G. Walker points out, that the main purpose of Skelton's poetry was anti-clerical satire, and ridicule of the cardinal made her all the more persuasive. courtier the poet managed to escape punishment for his sharp criticism by hiding in Westminster Abbey, where he was under the protection of his abbot J. Islip until his death in 1529

), “Colin Clout” (“Colin Clout”, 1522) and “Why are you not yard? ("Why Come Ye Not to Court?", 1522-1523). negative Wolsey deserved the attitude of the court poet not only thanks to some negative qualities of his character, but also because of his opposition to Skelton's patron, Thomas Howard (1473–1554), the third Duke of Norfolk. However, one should not forget, as G. Walker points out, that the main purpose of Skelton's poetry was anti-clerical satire, and ridicule of the cardinal made her all the more persuasive. courtier the poet managed to escape punishment for his sharp criticism by hiding in Westminster Abbey, where he was under the protection of his abbot J. Islip until his death in 1529

whether they could directly contact. Thomas Wolsey attended Cambridge university in 1520, when William Tyndel was studying there, they may have saw each other. In 1524 the future reformer left England and departed abroad, where he took up the translation of the Holy Scriptures into English. Wolsey stopped attempts to spread this heretical in England, as believed at that time the adherents of the Catholic Church, translation. Cardinal took all measures to protect England from the spread of the Lutheran heresy. In 1530 Tyndel published a treatise entitled The Practice of Papist prelates”, in which he devoted a whole section to the analysis of the state Wolsey's service, blaming the cardinal for all the troubles that befell England in the first third of the 16th century, including the divorce of King Henry VIII from Catherine Aragonese 13 . Let us now turn to the characterization of Volsey's personality. writings of his contemporaries mentioned.

Wolsey stopped attempts to spread this heretical in England, as believed at that time the adherents of the Catholic Church, translation. Cardinal took all measures to protect England from the spread of the Lutheran heresy. In 1530 Tyndel published a treatise entitled The Practice of Papist prelates”, in which he devoted a whole section to the analysis of the state Wolsey's service, blaming the cardinal for all the troubles that befell England in the first third of the 16th century, including the divorce of King Henry VIII from Catherine Aragonese 13 . Let us now turn to the characterization of Volsey's personality. writings of his contemporaries mentioned.

From childhood, Thomas was distinguished by an extraordinary mind, curiosity and ambition. He received his primary education at a grammar school. Ipswich, then at the school at St. Magdalen at Oxford, after graduating from which, at the age of 11, he entered Magdalen College. At 15 years, he received a bachelor's degree in liberal arts, and with it the nickname "boy bachelor" (boy bachelor). After receiving a master's degree of liberal arts, Wolsey was appointed teacher in the same grammar school at the college of St. Magdalene, which he once completed. At 1498 y. he was ordained, in 1502 received the office of chaplain from Henry Dean, Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1503 Wolsey entered the service of To Richard Nanfan, Assistant Lieutenant of Calais, and then to the Bishop Winchester to Richard Fox, who recommended him as tutor for Prince Heinrich 14 . As Polydorus Virgil points out in his "History of England", the Bishop of Winchester supported the young Wolsey and contributed in every possible way to his career growth in order to use him for struggle with his opponent Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, Earl Surrey, while remaining in the shadows.

After receiving a master's degree of liberal arts, Wolsey was appointed teacher in the same grammar school at the college of St. Magdalene, which he once completed. At 1498 y. he was ordained, in 1502 received the office of chaplain from Henry Dean, Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1503 Wolsey entered the service of To Richard Nanfan, Assistant Lieutenant of Calais, and then to the Bishop Winchester to Richard Fox, who recommended him as tutor for Prince Heinrich 14 . As Polydorus Virgil points out in his "History of England", the Bishop of Winchester supported the young Wolsey and contributed in every possible way to his career growth in order to use him for struggle with his opponent Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, Earl Surrey, while remaining in the shadows.

This is how the court historian of the young Wolsey describes: there was a priest named Thomas Wolsey, one of the royal chaplains, not an ignoramus in Scripture, a smart fellow and ready for any enterprises” 15 . It is his readiness for any, incl. and dubious in terms of morality, actions to achieve personal success, ambition and hidden vanity attracted, according to the author, the bishop Winchester in Wolsey. Thanks to the many accolades and support high-ranking patron, Wolsey receives a seat on the Privy Council and the opportunity to communicate with the king and his entourage; while Polydor Virgil notes his special gift to charm people and win them over. to himself: “... it’s amazing how quickly he managed to favorably dispose a company of young people close to Heinrich, who became his (Wolsey) favorites. He was a witty young man, ready at any moment to leave dignity befitting a priestly dignity and strum on a lute, dance, indulge in pleasant conversation, smile, joke and play" 16 .

It is his readiness for any, incl. and dubious in terms of morality, actions to achieve personal success, ambition and hidden vanity attracted, according to the author, the bishop Winchester in Wolsey. Thanks to the many accolades and support high-ranking patron, Wolsey receives a seat on the Privy Council and the opportunity to communicate with the king and his entourage; while Polydor Virgil notes his special gift to charm people and win them over. to himself: “... it’s amazing how quickly he managed to favorably dispose a company of young people close to Heinrich, who became his (Wolsey) favorites. He was a witty young man, ready at any moment to leave dignity befitting a priestly dignity and strum on a lute, dance, indulge in pleasant conversation, smile, joke and play" 16 .

In 1507 Thomas Wolsey became confessor to Henry VII. After joining throne in 1509 by Henry VIII, Wolsey's career went up rapidly. AT 1514 he added to the already existing post of Bishop of Lincoln the post Archbishop of York. In 1515, Pope Leo X ordained Wolsey to the dignity cardinal, and on November 18 he was solemnly presented with a cardinal's cap in Westminster Abbey, and soon the positions of chancellor were granted kingdom and the king's first minister. These fateful stages in life Wolsey became the subject of discussion by Skelton in two of his works 1516

In 1515, Pope Leo X ordained Wolsey to the dignity cardinal, and on November 18 he was solemnly presented with a cardinal's cap in Westminster Abbey, and soon the positions of chancellor were granted kingdom and the king's first minister. These fateful stages in life Wolsey became the subject of discussion by Skelton in two of his works 1516

The reason for creating the poem "Against poisonous tongues" 17 ("Against Venemous Tongues"), just served as the rise of Volsey from Archbishop of York to Cardinal. With a sardonic sneer, Skelton writes about the cardinal: “And what reward should the deceitful language? // Such languages deserve to be uprooted, // Grunting like pigs that purr in the mud." The mention of pigs points to Wolsey as on the butcher's son, but more outrageous for the author than low origin of the cardinal, is his ostentatious manifestation of the signs of his new high position. According to Skelton, the Latin letters "T" and "C" ( "Thomas Cardinalis" ) is very often repeated on his livery: "On chest and back // Latin letters have no number. The poet goes on to say, that thus reminding of himself, the cardinal forgets about Christ and the symbol the faith they are called to serve. In the only surviving morality Skelton "Magnificence" ("Magnificence" ) 18 main character symbolizes humanity, for whose soul and mind virtues and vices come into conflict with each other. Skelton allegorically depicts Wolsey by a character named Splendor, who, ceasing to be prudent, invites corrupt conspirators to his court and, as a result, loses power, then struggles to regain it. Skelton touched on the problem of good and bad government for a reason, since the main character of the morality - Thomas Wolsey - concentrated in his hands during these years, the entire foreign and a significant part of the domestic policy England: it is no coincidence that he receives the nickname "alter rex" from his contemporaries, or "ipse rex".

The poet goes on to say, that thus reminding of himself, the cardinal forgets about Christ and the symbol the faith they are called to serve. In the only surviving morality Skelton "Magnificence" ("Magnificence" ) 18 main character symbolizes humanity, for whose soul and mind virtues and vices come into conflict with each other. Skelton allegorically depicts Wolsey by a character named Splendor, who, ceasing to be prudent, invites corrupt conspirators to his court and, as a result, loses power, then struggles to regain it. Skelton touched on the problem of good and bad government for a reason, since the main character of the morality - Thomas Wolsey - concentrated in his hands during these years, the entire foreign and a significant part of the domestic policy England: it is no coincidence that he receives the nickname "alter rex" from his contemporaries, or "ipse rex".

At the beginning of his reign, Henry VIII was known to be more than government, occupied jousting tournaments, hunting, theatrical entertainment, dancing. However, these authors see in the indifference of the king to affairs of state the hand of Volsey himself. Polydor Virgil, for example, notes that the cardinal achieved this result with the help of cunning, persuading Henry VIII, "a man of good character, with a good educated and born to rule", to partially transfer to him administration of the state so that the king has more free time for noble pursuits according to your taste. “For recreation, he studied music and carefully pored over the books of St. Thomas Aquinas. He did it by Wolsey's insistence, since he was a convinced Thomist, ”notes Polydor Virgil. Soon, according to the historian, Volsey began to manage state at will, “and did a lot as he saw fit, relying primarily on the assistance of the Bishop of Winchester, who preferred him to the rest of his protégés" 19 .

However, these authors see in the indifference of the king to affairs of state the hand of Volsey himself. Polydor Virgil, for example, notes that the cardinal achieved this result with the help of cunning, persuading Henry VIII, "a man of good character, with a good educated and born to rule", to partially transfer to him administration of the state so that the king has more free time for noble pursuits according to your taste. “For recreation, he studied music and carefully pored over the books of St. Thomas Aquinas. He did it by Wolsey's insistence, since he was a convinced Thomist, ”notes Polydor Virgil. Soon, according to the historian, Volsey began to manage state at will, “and did a lot as he saw fit, relying primarily on the assistance of the Bishop of Winchester, who preferred him to the rest of his protégés" 19 .

We find similar reasoning in Tyndel, who in the treatise "The Practice of Papist Prelates" noted that the cardinal "wormed his way into the confidence royal grace "and actually ruled the king":

"As I heard various people say that he learned the science of sorcery, wore engraved amulets around his neck, with which he bewitched the mind of the king, and made him think of him more than of any other master or mistress in the kingdom, so now royal favor followed on his heels, as he used to follow the king.

And everything that he spoke was considered wisdom, and what he asserted was considered honor. So, over time, he [Wolsey] studied the way of thinking and the goodwill of the king's associates and all noble people, and those whom he considered necessary people, flattering them, ingratiated himself with them big promises, now swearing, now taking back their words, so that one helped the other, for without a terrible oath he never allowed no one in their secret affairs" 20 .

Climbing the career ladder, Volsey became more and more powerful, arrogant and arrogant. Polydor Virgil wrote:

"he became smug and arrogant even towards the nobles, ceasing to appreciate their friends, especially old ones who came to partly to congratulate him on his newfound honors, partly in connection with your own affairs." Wolsey should be proud that, despite the low origin, he managed to achieve such heights, but he, on the contrary, “did not like to remember this as something unworthy its provisions” 21 .

Tyndel noted: “as his career and dignity, he began to gather around him cunning people, as well as those who was intoxicated with the thirst for glory, like himself” 22 .

Polydor Virgil gives a special place to the indefatigable passion of Cardinal Wolsey for luxury and demonstration of symbols of one's power:

"As far as I know, he was both the first and the last of all clergy, including bishops and cardinals, who wore outerwear silk, which was also taken up by those priests who sought to win his favor. And in fact, this mannerisms in behavior created great hostility among clergy" 23 .

"He began to use a golden throne, a pillow and a tablecloth, cardinal hat, and the sign of his rank was carried in front of him on a pole by his servant, as if was an idol. The same hat was placed on the altar of the Royal Chapels during worship. Thus, because of his arrogance and Wolsey's ambitions won and deserved the dislike of the whole people, he was hated peers and communities, because they were very indignant at his vanity.

He became an object of general disgust and hatred…” 24 .

The desire for luxury was also expressed in the construction of majestic residences. Polydor Virgil mentions the palace built for Volsey Bridewell Palace on the banks of the River Fleet in the City of London representing is a wonderful architectural monument, which, however, "was hardly fit for life” 25 . Another, more famous Volsi Palace - Hampton Court (construction began in 1514) was not inferior to any of royal residences. Its architecture successfully combined traditions English Gothic and Italian Renaissance. For splendor and decoration the court of the minister of the English king, notes J. Cavendish, surpassed court of King Henry VIII himself 26 . Wherever Volsey went, his accompanied by a retinue of prelates and nobles; his court consisted of 500 persons noble birth, and the main places in it were occupied by knights and barons of the kingdom 27 . The reason for such luxury, according to Polydor Virgil, there was again the vanity of Volsey, who wanted to "perpetuate the memory of yourself” 28 . Wolsey's ambition and dominance were also expressed in his attempts make international politics. The British Chancellor saw his country in the role of "arbiter" overseeing the state of affairs in continental Europe, where the main bone of contention was the Apennine Peninsula. C 1494th on 1559 there were long Italian wars. In 1513 England was involved in the war against France. Roman Pontiff Julius II personally requested English cardinal to help the Holy See defeat the French king, and Wolsey did not give the pope a reason to be disappointed in his diplomatic abilities. Tyndel wrote about these events in The Practice of Papist Prelates:

The reason for such luxury, according to Polydor Virgil, there was again the vanity of Volsey, who wanted to "perpetuate the memory of yourself” 28 . Wolsey's ambition and dominance were also expressed in his attempts make international politics. The British Chancellor saw his country in the role of "arbiter" overseeing the state of affairs in continental Europe, where the main bone of contention was the Apennine Peninsula. C 1494th on 1559 there were long Italian wars. In 1513 England was involved in the war against France. Roman Pontiff Julius II personally requested English cardinal to help the Holy See defeat the French king, and Wolsey did not give the pope a reason to be disappointed in his diplomatic abilities. Tyndel wrote about these events in The Practice of Papist Prelates:

"Pope Julius wrote to his dear child Thomas Wolff [so pejoratively Tyndel calls the cardinal - auth. ] to be like this kind and amiable, and helped the holy church, being compared with Thomas Becket, for he was just as capable.

Then the new Foma, just as glorious, like the former, took matters into his own hands, and convinced royal grace. And then his royal grace took leave from his oath, which was a condition of peace between the English and French kings, and promised to help the holy throne ... As they said, so made…. And then parliament, and then payment, and then in French dogs, with a complete release of all sins to those who let at least one of them, or who will be killed in this war (for these words only work in the next world, but not in this one), and then straight into paradise without the torments of purgatory" 29 .

The English reformer repeatedly claimed that Wolsey was simply "dancing to the tune" of the Roman pontiff. This is a simplification. Wolsey, many say modern scholars, was a zealous guardian of the interests of English states 30 . As a result of a successful military campaign The British were able to capture the city of Tournai. However, in 1514 the allies Henry VIII, Ferdinand II and Maximilian I made peace with France, for that they incurred the wrath of the king of England, who did not forgive them betrayal. Henry had no choice but to sign with France world. In addition, he married his wife to King Louis XII of France. younger sister Maria 31 . In all these events, Volsey hosted most active participation. In 1518 the English cardinal became one of chief designers of the so-called. London Agreements (Treaty of London), treaty, according to which, the countries that signed this document, pledged not to fight with each other and to stand together against anyone, who will attack one of the countries that signed the agreement. This pact was directed primarily against the Ottoman Empire in order to preventing its penetration into Southern Europe 32 . Wolsey, remembering resentment of the English monarch against the Germans and Spaniards because of their betrayal in 1514, invited the king in 1519 to conclude an alliance with France. Polydor Virgil writes about how both sides came to this agreement: the help of his ambassadors, Francis I, as soon as he could, began to seduce Wolsey gifts and splendid speeches, and quickly won him over to his side in such a way that, being originally the most ardent opponent the French, has now become their most energetic defender .

Henry had no choice but to sign with France world. In addition, he married his wife to King Louis XII of France. younger sister Maria 31 . In all these events, Volsey hosted most active participation. In 1518 the English cardinal became one of chief designers of the so-called. London Agreements (Treaty of London), treaty, according to which, the countries that signed this document, pledged not to fight with each other and to stand together against anyone, who will attack one of the countries that signed the agreement. This pact was directed primarily against the Ottoman Empire in order to preventing its penetration into Southern Europe 32 . Wolsey, remembering resentment of the English monarch against the Germans and Spaniards because of their betrayal in 1514, invited the king in 1519 to conclude an alliance with France. Polydor Virgil writes about how both sides came to this agreement: the help of his ambassadors, Francis I, as soon as he could, began to seduce Wolsey gifts and splendid speeches, and quickly won him over to his side in such a way that, being originally the most ardent opponent the French, has now become their most energetic defender . .. " 33 .

.. " 33 .

It is Volsey who can be considered the main initiator and organizer of the magnificent meetings of the kings on the Field of Golden Brocade June 7-24, 1520 34 That's how evaluates his role in this important event W. Tyndel:

"Thomas Wolff, cardinal and legate, who longed to become dad 35 , although this is clearly too much for his secret intentions, he decided bring our king and the present king of France together and force them conclude a lasting peace and friendship among themselves, and this despite the fact that both kings and their nobility were at enmity with each other. They went not to announce, but make peace, forever and for one more day. But speaking of luxury attire of our master himself and his assistants, we can say that they would pass for the twelve apostles. I'm willing to bet that if Peter and Paul saw them all at once together, they would hardly believe that all of them, or even one of them, are their spiritual successors, like Thomas the unbeliever was not prepared to believe that Christ had risen.

” 36 .

Skelton probably mentions the same events in the poem "Colin Clout", where he points to the exorbitant passion of the cardinal for luxury, despite his ignoble origin. Skelton's Wolsey personifies the universal evil:

And just like that

Ready for you

About that story,

How can immediately raise

In the episcopal high rank

Simple hermit Vatican.

For this he is obliged

to admit that he subordinated

to the

strict Statute that0236 That he should go out on horseback

With a magnificent hood,

Sparkling with gold, crimson,

All his outfit should be

(For greater flour, they say)

Luxurious and rich.

The fabric of the collar is transparent

It should always be light,

Whiter than fresh milk,

And the gold of his stirrups

Should blind the eyes of the laity 37 .

Polydor Virgil notes that the chancellor shared with the king only part gifts, deceiving the naive Henry VIII and hiding from him the most valuable and expensive offerings from the king of the French. In addition, Francis I entered into a secret correspondence with the cardinal, praising him in his letters, referring to him as "Master" or "Father » and asking for advice on any about. Wolsi, Virgil concludes, "was ready to give everything he had forces” 38 for the benefit of France and to the detriment of his country.

In addition, Francis I entered into a secret correspondence with the cardinal, praising him in his letters, referring to him as "Master" or "Father » and asking for advice on any about. Wolsi, Virgil concludes, "was ready to give everything he had forces” 38 for the benefit of France and to the detriment of his country.

However, literally two months after the signing of peace, in the same 1520 d., Henry VIII, not without the help of Thomas Wolsey, concluded a new alliance, on this time with Emperor Charles V. In 1521 a new war began against France, in which England acted as an ally of Charles. For the war with France was in need of large funds, and Volsey installed new taxes in the state, as mentioned by W. Tyndel:

"Wolsey ordered that in London there should be held three times a week general procession and throughout the country too, while the royal gatherers collected taxes from ordinary people. Therefore, the incessant pestilence and that similar, according to the threats of God, should have fallen on the whole Christendom, as mentioned in Leviticus 26 and Deuteronomy, 28-29, for they (the clergy), along with the Turks, trampled on the name of Christ, and if they want to be called Christians, they need to turn around and look at the teachings of Christ.

Yes, and what was the fame of the cardinal, and with what a loud voice, when he deceived his own priests and made them swear by what they had in order to better spin them on payments, because ordinary priests are not very obedient to his superiors about money, unless they know where and why to pay0263 39 .

In 1521 Wolsi's inept mediation in Franco-imperial negotiations in Calais became the occasion for Skelton's ridicule in the poem "Speak, Parrot" ( Speak, Parrot ). The poet himself plays the role of a parrot, and the bird was not chosen by chance: the tradition of medieval bestiaries emphasizes her exotic origin (India) and the ability to imitate different sounds and human speeches 40 . There is a mirror in the parrot's cage. In medieval homiletic literature a mirror and the combination of its parts or fragments was a metaphor for unity in Christ, thus the speech parrot is inspired 41 . In the first part from the mouth of a parrot we learn that Henry VIII is personified with the King of the World ("King of Peace"), opposing Molech, the deity of the Moabites and Ammonites (1 Kings, 11:7), to whom they sacrificed children (Jer. 7:31), - with him and is compared Wolsey. The fourth part consists of short messages, in one of them the poet describes Wolsey's failure at Calais, another mentions Edward Stafford, the third Duke of Buckingham, who was executed in 1521 on charges of treason with the participation of the cardinal 42 . Wolsey had a hand in this to undermine reputation of Thomas Howard, patron of Skelton for many years. The poet depicts Wolsey riding a mule dressed in gold on his way to Jerusalem - a clear opposition to Jesus Christ entering, according to the biblical story, to the same city on a donkey in simple clothes. The gold in which Volsey is clothed is associated with the biblical parable of golden calf, which the parrot tells earlier, anticipating the story of human fall.

7:31), - with him and is compared Wolsey. The fourth part consists of short messages, in one of them the poet describes Wolsey's failure at Calais, another mentions Edward Stafford, the third Duke of Buckingham, who was executed in 1521 on charges of treason with the participation of the cardinal 42 . Wolsey had a hand in this to undermine reputation of Thomas Howard, patron of Skelton for many years. The poet depicts Wolsey riding a mule dressed in gold on his way to Jerusalem - a clear opposition to Jesus Christ entering, according to the biblical story, to the same city on a donkey in simple clothes. The gold in which Volsey is clothed is associated with the biblical parable of golden calf, which the parrot tells earlier, anticipating the story of human fall.

As early as 1518 Volsey became a papal legate, and in 1523 Clement VII appointed him legate for life. In this position, he diligence directed to the suppression of the Protestant heresy, the elimination of texts Lutherans, including the English translation of the New Testament by Tyndel. In 1521, Henry VIII published a treatise against Luther under entitled "On the Seven Sacraments", where he pointed out that Luther's doctrine of justification by faith leads to immorality 43 . In gratitude for this essay the English king received from the pope the title of "defender of the faith." Henry VIII, of course, also learned this joyful news from Wolsey, who may have been one of his consultants in writing this work. Tyndel writes about this event:

In 1521, Henry VIII published a treatise against Luther under entitled "On the Seven Sacraments", where he pointed out that Luther's doctrine of justification by faith leads to immorality 43 . In gratitude for this essay the English king received from the pope the title of "defender of the faith." Henry VIII, of course, also learned this joyful news from Wolsey, who may have been one of his consultants in writing this work. Tyndel writes about this event:

"When this glorious name 44 came from our holy father, Cardinal brought this message to his royal grace in Greenwich ... In the morning they were collected all the lords and gentlemen who could be summoned on such a short time to pronounce [name] with honor. And the next morning the cardinal learned of this from the monks. Part of the nobility appeared openly and conveyed to him [Volsey] a bow from Rome on behalf of the pope, some of them met his midway, part at the gate of the courtyard, and finally, his royal mercy met Volsey, led to a large hall where they were prepared high seats for his royal grace and the cardinal, there was a bull was read, and there are not only wise, but also people of a narrow mind laughed, ridiculing the vainly pompous style, as on receipt a cardinal's cap, which a rude man brought to Westminster under the hollow of the raincoat" 45 .

Volsi took an active part in almost all activities, associated with the punishment of heretics and the seizure of Protestant literature, in including Tyndel's writings. Tyndel considered him an accomplice of Thomas More in fight against the reformers 46 who convinced the king to appoint his Mor's successor, since he is "a learned man and a layman, and he deserved this position with his writings against Martin Luther, and also against “Obedience” and “Mammon” 47 , became the protector of purgatory and wrote against intercession for the poor and vagabonds” 48 . Tyndel even believed that the fall of Volsey was a ploy performed by Rome to continuation of the atrocities of the latter under his successor Thomas More. Tyndel omits the speech of More Chancellor before Parliament, in which English humanist condemned the cardinal for attempting to deceive and pressure king 49 . Moreover, it is known about the conflict between these two statesmen 50 . 19th century English historian J. R. Green noted that "the reform movement in England was favored Wolsey's indifference" 51 . This assessment seems correct given the campaign cardinal for the dissolution of monasteries, especially those where egregious cases of corruption. The proceeds from the activities carried out went on the creation of educational institutions: a grammar school in Ipswich, Cardinal College, Oxford, later renamed Christ Church College.

19th century English historian J. R. Green noted that "the reform movement in England was favored Wolsey's indifference" 51 . This assessment seems correct given the campaign cardinal for the dissolution of monasteries, especially those where egregious cases of corruption. The proceeds from the activities carried out went on the creation of educational institutions: a grammar school in Ipswich, Cardinal College, Oxford, later renamed Christ Church College.

The demonization of the image of Volsey is clearly seen in the poem by J. Skelton "Why don't you come to court?" In the first part of Skelton's work gives a biography of a character named Dicken, a devil who symbolizes the Volsey. In the second part, which deals with the cardinal's court, the author focuses on the fact that this is not a royal court, where he himself The Lord placed his anointed one, and Hampton Court Palace, built for the Wolsey at the behest of the king. In the third part, the cardinal is compared with Amalek, father of the Amalekites, grandson of Esau, who brought much trouble Jews (Ex. 17:8-16).

17:8-16).

The Garland of Laurel, first major poem Skelton, unpublished before 1523, contains, at first glance, glance, an attempt to reconcile the poet with his worst enemy. latin dedication "To His Serene Highness, as well as to the Lord Cardinal, most deserved legate" is perceived by many as an attempt by the poet to apologize to Volsey in order to get a pre-bend and more opportunities not hiding in Westminster Abbey. But the poem praises rather not Wolsey, but the king, and Skelton's goal in the first place was to sing his patron, Thomas Howard, than anyone else.

One of the events that led to the fall of Wolsey was the divorce of the king. According to Tyndel, the idea of divorce came from the cardinal and his "henchman" of Longland, Bishop of Lincoln, and was one of the dark and dirty intrigues that the clergy were weaving for hundreds of years 52 :

"He made the present Bishop of Lincoln, his old friend, confessor, and whatever the king, the cardinal found out the same day.

It's no wonder how God's creatures must obey God and serve him, so the creations of the pope must obey the pope and serve his Holiness" 53 .

This next initiative of the cardinal, according to Polydor Virgil, was fatal mistake. The final of the XXVII book of the History of England is description of the divorce proceedings of the royal couple. Thanks to cunning chancellor, it comes to a public trial, which only increases the number of Volsey's enemies:

"Then the Queen took the floor and publicly condemned Wolsey for his treachery, deceit, lawlessness and dishonesty with which he tries cause discord between her and her husband, and she did the following public statement: “I accuse, renounce and wish to get away from such a judge, who is the most hostile of the enemies of law and justice, I will go to the Pope alone and take my case to court to him alone." When she said those words with tears in her eyes, you could see that everyone turned their hard eyes on Volsey .

.. ".

However, quickly noticing the increased interest of the king in Anne Boleyn, the cardinal sees in her not only a possible future queen, but also a danger to herself, "... primarily because of the offensive arrogance of the girl", which, in his opinion, "should be feared more than death". Wolsey enters into an agreement with the pope, conducts secret correspondence with him with the aim of delay the divorce proceedings until it succeeds influence Heinrich. All of the above does not pass by the attention of the king, determined to punish "this man who had become so forgetful all the good deeds that have been done for him" 54 .

Without regret and unambiguously writes about the resignation of Volsey Tyndel:

“I have many thoughts about the cardinal's overthrow. Firstly, I have never heard or read that a man who was such a traitor and a traitor, suffered such an easy death <…>. God brought down on him his own evil. Wolsey paid for the betrayal he planned against the king and those whom he led away from the people, lest rebelled.

He thought of cheating fate with his tricks (as proved by the move tragedy), remained sitting in his office to continue to lead and resist God, as he had long ago done. Chief among all his henchmen no less skillful than his master in lying, pretense and duplicity. The cardinal could not speak with royal grace, he had the great seal was taken away, Wolsey was accused of high treason, but about the main betrayal that he planned, not a single word was said words" 55 .

Volsey was indeed accused of high treason, and he threatened with the death penalty, but he died before the meeting with the king, on the way from York to London.

So, for all three authors, Volsey is an example of an unrighteous political doer and vicious representative of the clergy. Expressive-evaluative Skelton's poems are filled with judgments about him. He uses all his poetic arsenal, which includes numerous comparisons with both the devil himself, and with biblical characters who spoke on the side evil. An invariable attribute of the image of Volsey (or the character who personifies) clothes made of expensive fabrics and excessive use of gold jewelry. Skelton does not forget to mention his low origin. According to the poet, he is guilty not only of troubles, fallen to the lot of their native country, but also in betrayal of their own Christian faith, to which he goes to achieve his selfish goals. The poetic tradition created by Skelton became in many ways the basis for the next generation of English poets and playwrights (including Shakespeare), whose works in British historiography of recent years subjected to deep analysis 56 .

An invariable attribute of the image of Volsey (or the character who personifies) clothes made of expensive fabrics and excessive use of gold jewelry. Skelton does not forget to mention his low origin. According to the poet, he is guilty not only of troubles, fallen to the lot of their native country, but also in betrayal of their own Christian faith, to which he goes to achieve his selfish goals. The poetic tradition created by Skelton became in many ways the basis for the next generation of English poets and playwrights (including Shakespeare), whose works in British historiography of recent years subjected to deep analysis 56 .

Tyndel gives an equally sharp assessment of Volsey's service. He doesn't skimp on epithets and comparisons, calling Volsey “Sinon who betrayed Troy”, “evil wolf", "raging sea", "death for all England". For Tyndel Wolsey's service is an example of the work of a servant of the Antichrist. He blames State Chancellor in all the misfortunes that have occurred in the country and in world in the first third of the 16th century, primarily referring to the numerous military campaigns in which a large number of Englishmen died, French and other peoples. As A. Kinney accurately noted, the English the cardinal is "a common enemy of Tyndel and Skelton" 57 .

As A. Kinney accurately noted, the English the cardinal is "a common enemy of Tyndel and Skelton" 57 .

Polydor Virgil, unlike his colleagues, seeks to find for deeds Wolsey Rational Causes: The Cardinal's Greed and Hardness of Heart due to his low origin, opposition to Queen Catherine - their personal hostile relationship. Despite the fairly frequent vivid metaphors and direct speech of historical characters, demonization of the image Wolsi is absent, there are no comparisons with the devil, no mention of him supernatural abilities, which his colleagues abuse. More In addition, Polydor Virgil recognizes certain talents of Volsey, his penetrating mind and ambition, showing readers his image with humanistic message to draw certain lessons from the history of his life. Thus, Polydorus Virgil, unlike the other two authors, gives the most balanced and sober assessment of the personality of the State Chancellor.

BIBLIOGRAPHY / REFERENCES

Boccaccio G. Decameron. M.: Pravda, 1989.

Decameron. M.: Pravda, 1989.

Skelton J. From "Colin Clout" / transl. ABOUT. Rumera // Reader by Western European literature. Renaissance / comp. B.I. Purishev. M., 1947. S. 446-447.

Cavendish G. The life and death of Cardinal Wolsey / ed. by R.S. Sylvester, L., 1959. Reprint / Ed. Ian Lancashire. Toronto: Web Development Group University of Toronto Library, 1997.187 p. URL: http://www.library.utoronto.ca/utel/ret/cavendish/cavendish.html

Desiderius Erasmus . Hecuba et Iphigenia in Aulide Euripidis Tragoediae: Eiusdem Ode de laudibus Britanniae, Regisq[ue] Henrici septimi, ac regiorum liberorum eius. 1511.).

Grafton R . Graftons's chronicle or history of England, to which is added his table of the bailiffs, sheriffs, and mayors of the city of London. From the year 1189 to 1558. 2 vols. L., 1809.

Henry VIII. Assertio septem sacramentorum adversus Mart. Lutherum Henrico VIII, Angliae rege auctore. Cui sub nex a est eiusdem Regis epistola, assertionis ipsius contra eundem defensoriia. accedit quoque r.p.d. Iohan Roffen, epics. Contra Lutheris captivitatem Babylonicam Assertionis regiae defensio. Parisii: Apud Gulielmum Desboys, 1562.

Cui sub nex a est eiusdem Regis epistola, assertionis ipsius contra eundem defensoriia. accedit quoque r.p.d. Iohan Roffen, epics. Contra Lutheris captivitatem Babylonicam Assertionis regiae defensio. Parisii: Apud Gulielmum Desboys, 1562.

Holinshed R . Holinshed's chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland. 6 vols. L., 1807-1808.

Skelton J. Against Venomous Tongues Enpoisoned with Slander and False Detractions / Pithy, pleasaunt and profitable workes of Maister Skelton. London: T. Marshe, 1568. 385 p. URL: http://www.exclassics.com/skelton/skel031.htm

Skelton J. Biography, poems. Poetry Foundation. URL : http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/john-skelton#poet

Skelton J. The Garland of Laurel. URL : http://www.exclassics.com/skelton/skel061.htm

Skelton J. Magnificence. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1980. 229 p.

Skelton J. Speak, Parrot. URL: http://www.exclassics.com/skelton/skel063.htm

Skelton J. Why Come Ye not to Court? URL : http://www.exclassics.com/skelton/skel065.htm

Tyndale W. Practice of papisticall Prelates // The Whole works of W. Tyndall, John Frith, and Doct. Barnes, three worthy Martyrs and principall teachers of this Church of England collected and compiled in one Tome together, being scattered now in Print here exhibited to the Church / ed. John Fox. London: Printed by J. Daye, 1573. P. 340-377.

Vergil P. Anglica Historia. Latin text and English translation / Ed. and trans. by D.J. Suton. Library of Humanistic Texts at the Philological Museum of the University of Birmingham's Shakespeare Institute, 2005. Book XXVII. URL: http://www.philological.bham.ac.uk/polverg/27lat.html

Vergil P. The Anglica Historia of Polydore Vergil, A.D. 1485-1537. / Ed. by D. Hay. London: Offices of the Royal Historical Society, 1950.

REFERENCES

Gavrilov S.N. Thomas Wolsey - "Alter rex" of England 1515-1529 // Glory and oblivion: the paradoxes of biographics. St. Petersburg: Aleteyya, 2014. S. 248-264 [ Gavrilov S.N. Tomas Wolsi - "Alter rex" Anglii 1515-1529 // Slava i zabvenie: paradox biographics. SPb.: Aleteyya, 2014. S. 248-264].

Gorelov M.M. Historical turning points of the past in English historiography Early Modern: Polydorus Virgil. // Dialogue with time. M.: IVI RAN, 2012, No. 41, pp. 235–256 [ Gorelov M.M. Historical fractures proshlogo v angliyskoy istoriografii rannego Novogo vremeni: Polidor Vergili // Dialog so vremenem. 2012. No. 41. S. 235–256].

Green J. R. History of the English people / transl. from English. P. Nikolaev. T. 2. M., 1892 [ Grin Dzh.R. Istoriya English people / per. s engl. P. Nikolaeva. T. 2. M., 1892].

Green JR History of England and the English people / trans. from English. 2nd ed. M.: Kuchkovo field, Hyperborea, 2007. 888 p. [ Grin J.R. History English i English people / per. s engl. 2nd izd.. M.: Kuchkovo pole, Giperboreya, 2007. 888 s.]

from English. 2nd ed. M.: Kuchkovo field, Hyperborea, 2007. 888 p. [ Grin J.R. History English i English people / per. s engl. 2nd izd.. M.: Kuchkovo pole, Giperboreya, 2007. 888 s.]

Domnina E.G. England and the Duchy of Urbino 1474-1500: Private case of using the Order of the Garter as a tool of diplomacy // Medium century. 2005. 66. P. 200–217 [ Domnina E.G. Angliya i hertsogstvo Urbino v 1474–1500 gg.: chastnyy sluchay ispol'zovaniya ordena Podvyazki kak orudiya diplomatii // Srednie veka. 2005. 66. S. 200–217].

Ivonin Yu.E. Henry VIII // Questions of history. 2008. no. 8.44-63 [ Ivonin Yu.E. Genrikh VIII // Voprosy istorii. 2008. no. 8.44-63].

Kiryukhin D.V. Early Tudor court intelligentsia and their role in education and upbringing of the heirs to the royal throne // Intelligentsia and world. 2013. No. 3. P. 118-126 [Kiryukhin D.V. Pridvornaya intelligentsia epokhi rannikh Tyudorov i ee rol' v obuchenii i vospitaniii naslednikov korolevskogo trona // Intelligentsiya i mir. 2013. No. 3. S. 118-126].

2013. No. 3. S. 118-126].

Lowes D. Henry VIII and his queens. District / D: Phoenix, M .: Zeus, 1997. 320 p. [ Loudz D. Genrikh VIII i ego korolevy. R-n/D: Feniks, M.: Zevs, 1997. 320 s.].

Osinovsky I.N. Thomas More and the Reformation of Henry VIII (On the question of contradictions of the ideological views of T. Mora) // Essays on social - economic and political history of England and France XIII - XVII centuries: Sat. Art. / Rev. ed. V.F. Semenov. M.: MGPI, 1960. S. 79-95 [ Osinovskiy I.N. Tomas Mor i Reformatsiya Genrikha VIII (K voprosu o protivorechiyakh ideologicheskikh vzglyadov T. Mora) // Ocherki sotsial'no – ekonomicheskoy i politicheskoy istorii Anglii i Frantsii XIII-XVII centuries: Sb. st. /Otv. red. V.F. Semenov. M.: MGPI, 1960.S. 79-95].

Osinovsky I. N. Thomas More: utopian communism, humanism, Reformation. M.: Nauka, 1978. 326 p. [ Osinovskiy I.N. Tomas Mor: utopicheskiy kommunizm, gumanizm, Reformatsiya. M.: Nauka, 1978. 326 s.]

M.: Nauka, 1978. 326 s.]

Ryzhov N.V. All monarchs of the world. Western Europe. M.: Veche, 1999. 655 p. [ Ryzhov N.V. All monks mira. Zapadnaya Evropa. M.: Veche, 1999. 655 s.].

Smirnov E.R. The idea of constitutionalism in England at the end of the 14th - the first half of the 15th century: a historiographical aspect. // Bulletin of Nizhny Novgorod University. N.I. Lobachevsky. Series: Law. No. 1. N. Novgorod, 2003. pp. 101–108 [ Smirnov E.R. Idea konstitutsionalizma v Anglii kontsa XIV – pervoy poloviny XV vv.: istoriograficheskiy aspekt. // Vestnik Nizhegorodskogo universiteta im. N.I. Lobachevsky. Seriya: Right. No. 1. N.Novgorod, 2003. S. 101–108].

Chugunova T.G. William Tyndel. Historical biography. N. Novgorod: NGPU, 2014. 241 p. [ Chugunova T.G. Uil'yam Tindel. History biography. N. Novgorod: NGPU, 2014. 241 s.].

Chugunova T.G. Thomas Wolsey's service according to W. Tyndel's treatise "Practice papist prelates” // Bulletin of the Nizhny Novgorod University. No. 5(6). N.Novgorod, 2015. S. 150-154 [ Chugunova T.G. Sluzhba Tomasa Volsi po traktatu U. Tindela "Praktika papistskikh prelatov" // Vestnik Nizhegorodskogo universiteta. No. 5(6). N.Novgorod, 2015. S. 150-154].

No. 5(6). N.Novgorod, 2015. S. 150-154 [ Chugunova T.G. Sluzhba Tomasa Volsi po traktatu U. Tindela "Praktika papistskikh prelatov" // Vestnik Nizhegorodskogo universiteta. No. 5(6). N.Novgorod, 2015. S. 150-154].

Arnold J. “Polydorus Italus”: analyzing authority in Polydore Vergil's Anglica Historia. // Reformation & Renaissance Review, 16, 2014. P. 122–137.

Clark J.A. Corrupt Prelates in Tyndale and Shakespeare // Word, Church, and State. Tyndale Quincentenary Essays. Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1998. P. 287-306.

Creighton M. Cardinal Wolsey. London; New York: Macmillan and Co., 1888. 226 rubles.

Daniell D. William Tyndale: A Biography. New Haven and L.: Yale Univ. Press, 1994. 429 p.

Demaus R. William Tyndale: A Biography / Rev. by Richard Lovett. 3d ed. London: Religious Tract Society, 1904. 341 p.

Edwards H.L.R. Skelton: The Life and Times of an Early Tudor Poet. L.: Cape, 1949. 325 p.

L.: Cape, 1949. 325 p.

Ferguson C.W. Naked to Mine Enemies: The Life of Cardinal Wolsey. Boston: Little, Brown, 1958. $543

Gordon I.A. John Skelton: Poet Laureate. Folcroft, Pa.: Folcroft Library Editions. 1977. 223 p.

Gwyn P. The King's Cardinal: The Rise and fall of Thomas Wolsey. L.: Barrie & Jenkins, 1990. $665

Harris W.O. Skelton's “Magnyfycence” and the Cardinal Virtue tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1965. 177 p.

Hay D. The Life of Polydore Vergil of Urbino // Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. Vol. 12. 1949. R. 132-151.

Hay D. Polydore Vergil: Renaissance Historian and Man of Letters. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952. 223 p.

Heiserman R. Skelton and Satire. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961. 326 p.

Hertel R. Nationalizing History? Polydore Vergil's Anglica Historia, Shakespeare's Richard III, and the Appropriation of the English Past. // Schaff B. Exiles, Emigres and Intermediaries: Anglo-Italian cultural transactions. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2010, pp. 47–70.

// Schaff B. Exiles, Emigres and Intermediaries: Anglo-Italian cultural transactions. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2010, pp. 47–70.

Kinney A.F. Skelton and Tyndale: Men of the Cloth and of the Word // Word, Church, and State. Tyndale Quincentenary Essays. Washington: Catholic Univ. of America Pr., 1998, pp. 275-286.

Kinsman R.S. The “Buck” and the “Fox” in Skelton's “Why Come Ye Nat to courte?” // Philological Quarterly, 29 (January 1950). P. 61-64.

Lloyd L.J. John Skelton: A Sketch of His Life and Writings. Oxford: Blackwell, 1938. 152 p.

Morris T.A. Europe and England in the sixteenth century. London: Routledge, 1998. $376

Mozley J.F. William Tyndale. London: Society for promoting Christian knowledge; New York: The Macmillan Co., 1937. 364 p.

Parrot // The Medieval Bestiary. URL: http://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast235.htm

Pollard A.F. Wolsey. London: Longmans, Green and Co. , 1929. 393 p.

, 1929. 393 p.

Ridley J. Statesman and Saint: Cardinal Wolsey, Sir Thomas More and the Politics of Henry VIII. New York: Viking Press, 1983. 338 p.

Schwartz-Leeper G.E. Princes into pages: Images of Cardinal Wolsey in the satires of John Skelton and Shakespeare's Henry VIII . URL: https://www.academia.edu/349151/

Teems D. Tyndale – The Man Who Gave God an English Voice. L.: Thomas Nelson, 2012. 336 p.

Walker G. Cardinal Wolsey and the Satirists: the Case of Godly Queen Hester re-opened // Cardinal Wolsey: Church, State and Art / Eds. S.J. Gunn and P.G. Lindley. Cambridge: U.P., 1991. P. 239-260.

Walker G . John Skelton and the Politics of the 1520s. Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History. Cambridge University Press, 1988. 228 p.

Williams C.H. William Tyndale. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd. 1969. 270 p.

Williams N. The Cardinal and the Secretary: Thomas Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. 1976. 278 p.

New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. 1976. 278 p.

Wyly T.J. Tyndale as Interpreter of Henrician Politics // Word, Church, and State. Tyndale Quincentenary Essays. Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1998. P. 259-274.

-

In domestic literature, the surname of an English cardinal transcribed variously: Wolsey, Woolsey, Wolsey. Tradition pre-revolutionary historiography, the authors of this article convey it like wolsey. ↩

-

Only a few papers available: Ivonin 2008; Gavrilov 2014; Chugunova 2015. ↩

-

For the most important see: Creighton 1888 ; Pollard 1929; Ferguson 1958; Williams 1976; Ridley 1983; Gwyn 1990. ↩

-

John Skelton (1460-1529) - court poet of the early Tudors, teacher of Henry VIII, one of the earliest representatives Poetry of the English Renaissance. According to Erasmus of Rotterdam, Skelton - "immortal poet", "a beacon and decoration of the British literature” (see: Desiderius Erasmus.

1511. In addition to the regalia, in 1498 Skelton was ordained and became a priest in Norfolk. (See also about him: Kiryukhin 2013. P. 119-120).

1511. In addition to the regalia, in 1498 Skelton was ordained and became a priest in Norfolk. (See also about him: Kiryukhin 2013. P. 119-120). Polydor Virgil (1470-1555) - a native of Italy, a relative Cardinal Adrian de Castello, spent a significant part of his life in England. In 1502, Polydorus Virgil traveled to England for the first time on on behalf of Pope Alexander VI as an assistant to the tax collector, and in October became Bishop of Bath and Wells.

William Tyndel (1494-1536) - Reformer, controversialist, translator of the Bible into English, forced to live in a foreign land (in Germany and Netherlands) and be martyred in order to make Holy Scripture accessible to their countrymen. (cm. details: Chugunova 2014). ↩

-

Cavendish 1959. This work was used by Shakespeare in his play "Henry VIII". ↩

-

Vergil 1950. Translated by D. Sutton into modern English - Vergil 2005.

↩

↩ -

Hertel R. 2010. P. 47–70; Arnold J . 2014. P. 122–137. In writings Russian historians touch upon only certain aspects of life and career as a humanist historian. – E.G. Domnina examines him diplomatic activity as a representative of the Roman Curia ( Domnina 2005), E.R. Smirnov uses the works of Polydor Virgil when referring to the question of the relationship between royal power and Parliament ( Smirnov 2003, and the article by M.M. Gorelov is devoted to the analysis historical past of England in the work of a humanist scientist ( Gorelov 2012). ↩

-

Schwartz-Leeper; Lloyd 1938; Kinsman 1950; Heiserman 1961; Harris 1965. ↩

-

Kinney 1998; Walker 1988; Gordon 1977; Edwards 1949. ↩

-

Demaus 1886; Mozley 1937; Williams 1969 ; Daniell 1994; Teems 2012.

↩

↩ -

See: Hay 1949. P. 139. ↩

-

See: Hay 1952, pp. 44-45. ↩

-

Tyndale 1573. R. 367-375. ↩

-

See: Holinshed 1807–1808. Vol. 3. P. 756; Gavrilov 2014. S. 249. ↩

-

Vergil P. 2005. Book XXVII. R. 1. ↩

-

Vergil P. 2005. P. 1. ↩

-

Skelton 1568. ↩

-

Skelton 1980. ↩

-

Vergil. Book XXVII. R. 1. ↩

-

Tyndale 1573. P. 367-368. ↩

-

Vergil. Book XXVII. P. 1. ↩

-

Tyndale 1573. R. 368. ↩

-

Vergil. Book XXVII. P. 1. ↩

-

Ibid. P. 20. ↩

-

Ibid. P. 17. ↩

-

Cavendish 1997. R. 15. ↩

-

Green S.

336. ↩

336. ↩ -

Vergil. Book XXVII. P. 17. ↩

-

Tyndale 1573. R. 369. ↩

-

Clark 1998. P. 302-306; Wyly 1998. P. 260-265. ↩

-

Ryzhov 1999. P. 122. ↩

-

Morris 1998. P. 34. ↩

-

Vergil 2005. Book XXVII. P. 25. ↩

-

English Field of Cloth of Gold, fr. Le Camp du Drap d'Or. This place negotiations between the two kings is at Balingham, between Gin and Ardrom, near Calais (modern France, in those days - the territory English crown). These events are depicted in the engraving by J. Basir "Field of golden brocade" (1774) ↩

-

Wolsey was one of the candidates for the papacy after his death Adrian VI in 1523, but did not get enough votes, so how the emperor did not support him. ↩

-

Tyndale 1573. R. 370. ↩

-

Skelton 1947.

pp. 446-447. ↩

pp. 446-447. ↩ -

Vergil 2005. Book XXVII. P. 25. ↩

-

Tyndale 1573. R. 367. ↩

-

Parrot. Medieval Bestiary. The second source for Skelton was Decameron by Boccaccio (1353.), in which the divinity of the parrot explained by the fact that his pen is perceived by the heroes as a pen Archangel Gabriel ( Boccaccio 1989, p. 432). ↩

-

Skelton. Biography, poems. Poetry Foundation. ↩

-

Polydor Virgil noted in connection with this incident that "Wolsi burned hatred and thirsted for human blood…” (see: Vergil 2005. Book XXVII. P. 35). ↩

-

Henry VIII. 1562. R. 5. ↩

-

Meaning "Defender of the Faith" - Defensor fidei. ↩

-

Tyndale. 1573. R. 374-375. ↩

-

Tyndale 1573. R. 373. See more: Chugunova 2014. P. 69, 74-76.

↩

↩ -

Tyndel is referring to his writings: "The obedience of a Christian and how Christian authorities must govern", "The Parable of the Wicked Mammon." ↩

-

Thomas More argued with Simon Fish, who published in 1528 tractate "Prayer for the poor". Moore, in turn, answered him the work "The Prayer of Souls" (for more details see: Osinovsky 1978. S. 279). ↩

-

Grafton 1809. Vol. 2. R. 338. ↩

-

Osinovsky 1960. P. 82. ↩

-

Green 1892. Vol. 2. S. 103. ↩

-

Tyndale 1573. R. 320-321. ↩

-

Ibid. R. 368-369. ↩

-

Vergil 2005. Book XXVII. R. 59. Later Wolsey changed his point vision and tried his best to please Henry VIII. In token of thanks Anne Boleyn wrote Wolsey the following letter content: “In all the days of my life, I am most indebted to king to love you and serve you; and I ask you never to doubt that I will not change this thought as long as the spirit lives in my body ”(quoted from: Lowds 1997 S.

90-91). ↩

90-91). ↩ -

Tyndale 1573. R. 373. ↩

-

Schwartz-Leeper [Electr. resource]. ↩

-

Kinney . P. 276. ↩

Words: 4798 | Characters: 27462 | Paragraphs: 46 | Footnotes: 57 | Bibliography: 59 | Microwave: 20

Keywords: Thomas Wolsey , John Skelton , Polydore Vergil , William Tyndale , Reformation

The article presents the interpretation of the image of the English cardinal, minister and chancellor Thomas Wolsey by his contemporaries John Skelton, Polydore Vergil, William Tyndale. The representations of Wolsey in the public consciousness of his contemporaries were largely dependent on their authors’ own relationship with the first minister of the king. For all three authors, Wolsey is an example of the unscrupulous politician and the vicious representative of clergy.