Original jack and the beanstalk story

The Original Story of “Jack and the Beanstalk” Was Emphatically Not for Children

If, like me, you once tried to plant jelly beans in your backyard in the hopes that they would create either a magical jelly bean tree or summon a giant talking bunny, because if it worked in fairy tales it would of course work in an ordinary backyard in Indiana, you are doubtless familiar with the story of Jack and the Beanstalk, a tale of almost but not quite getting cheated by a con man and then having to deal with the massive repercussions.

You might, however, be a little less familiar with some of the older versions of the tale—and just how Jack initially got those magic beans.

The story first appeared in print in 1734, during the reign of George II of England, when readers could shill out a shilling to buy a book called

Round about our Coal Fire: Or, Christmas Entertainments, one of several self-described “Entertaining Pamphlets” printed in London by a certain J. Roberts. The book contained six chapters on such things as Christmas Entertainments, Hobgoblins, Witches, Ghosts, Fairies, how people were a lot more hospitable and nicer in general before 1734, and oh yes, the tale of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean, and how he became Monarch of the Universe. It was ascribed to a certain Dick Merryman—a name that, given the book’s interest in Christmas and magic, seems quite likely to have been a pseudonym—and is now available in what I am assured is a high quality digital scan from Amazon.com.

(At $18.75 per copy I didn’t buy it. You can find plenty of low quality digital scans of this text in various places in the internet.)

The publishers presumably insisted on adding the tale in order to assure customers that yes, they were getting their full shilling’s worth, and also, to try to lighten up a text that starts with a very very—did I mention very—lengthy complaint about how nobody really celebrates Christmas properly anymore, by which Dick Merryman means that people aren’t serving up as much fabulous free food as they used to, thus COMPLETELY RUINING CHRISTMAS FOR EVERYONE ELSE, like, can’t you guys kill just a few more geese, along with complaining that people used to be able to pay their rent in kind (that is, with goods instead of money) with the assurance that they’d be able to eat quite a lot of it at Christmas. None of this is as much fun as it sounds, though the descriptions of Christmas games might interest some historians.

None of this is as much fun as it sounds, though the descriptions of Christmas games might interest some historians.

Also, this:

As for Puffs in the Corner, that is a very harmless Sport, and one may ramp at it as much as one will; for at this Game when a Man catches his Woman, he may kiss her ’till her Ears crack, or she will be disappointed if she is a Woman of any Spirit; but if it is one who offers at a Struggle and blushes, then be assured she is a Prude, and though she won’t stand a Buss in publick, she’ll receive it with open Arms behind the Door, and you may kiss her ’till she makes your Heart ake.

….Ok then.

This is all followed by some chatter and about making ladies squeak (not a typo) and what to do if you find two people in bed during a game of hide and seek, and also, hobgoblins, and witches, and frankly, I have to assume that by the time Merryman

finally gets around to telling Jack’s tale—page 35—most readers had given up. I know I almost did.

I know I almost did.

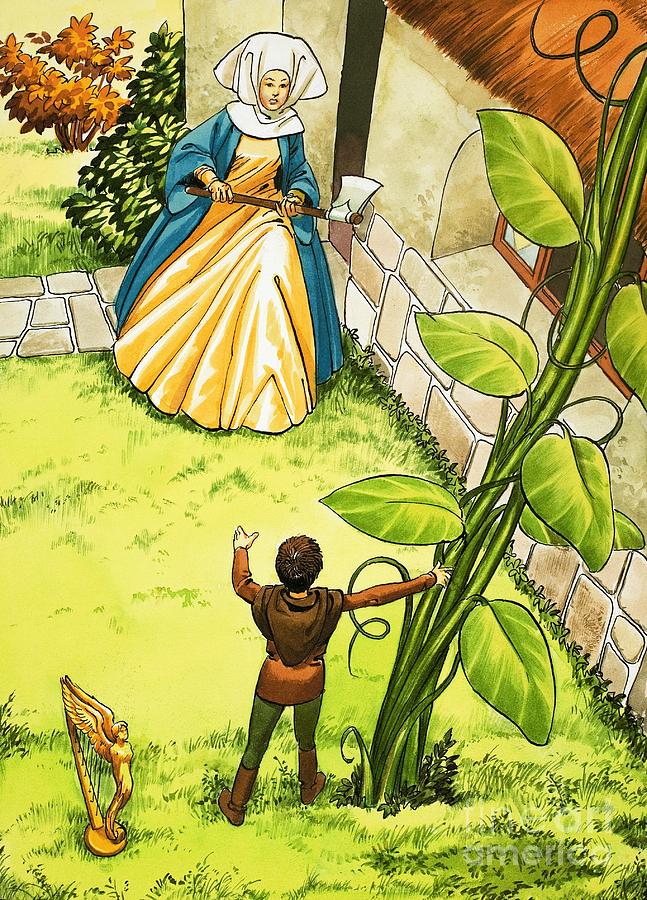

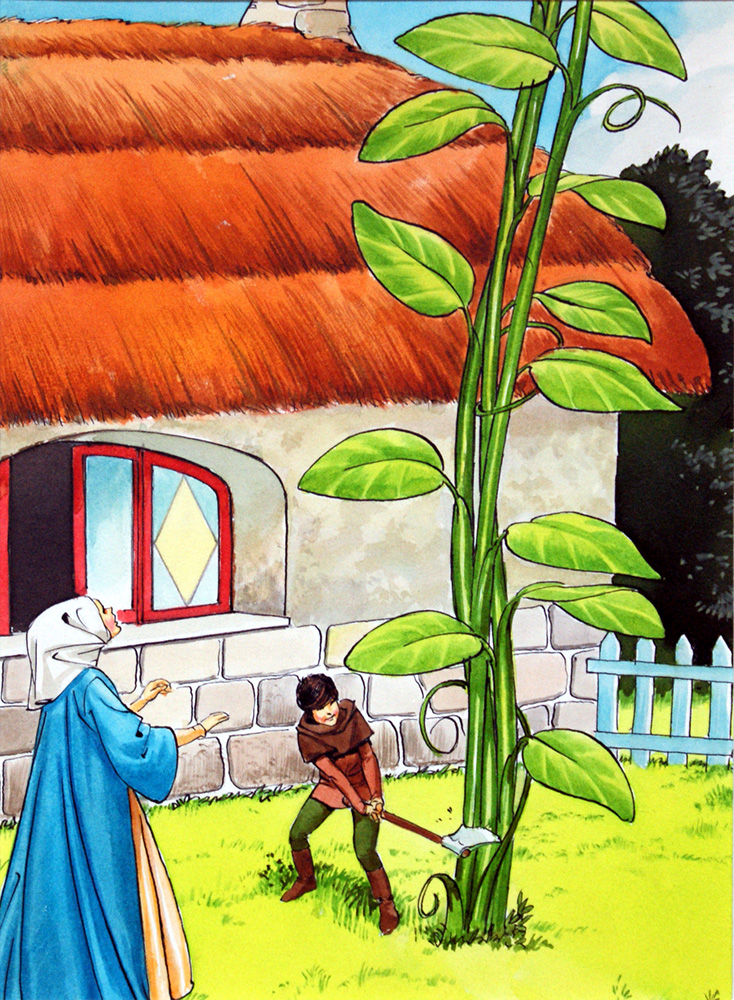

Image from Round about our Coal Fire: Or, Christmas Entertainments (1734)

The story is supposedly related by Gaffer Spiggins, an elderly farmer who also happens to be one of Jack’s relatives. I say, supposedly, in part because by the end of the story, Merryman tells us that he got most of the story from the Chit Chat of an old nurse and the Maggots in a Madman’s brain. I suppose Gaffer Spiggins might be the madman in question, but I think it’s more likely that by the time he finally got to the end, Merryman had completely forgotten the start of his story. Possibly because of Maggots, or more likely because the story has the sense of being written very quickly while very drunk.

In any case, being Jack’s relative is not necessarily something to brag about. Jack is, Gaffer Spiggins assures us, lazy, dirty, and dead broke, with only one factor in his favor: his grandmother is an Enchantress. As the Gaffer explains:

for though he was a smart large boy, his Grandmother and he laid together, and between whiles the good old Woman instructed Jack in many things, and among the rest, Jack (says she) as you are a comfortable Bed-fellow to me —

Cough.

Uh huh.

Anyway. As thanks for being a good bedfellow, the grandmother tells Jack that she has an enchanted bean that can make him rich, but refuses to give him the bean just yet, on the basis that once he’s rich, he will probably turn into a Rake and desert her. It’s just barely possible that whoever wrote this had a few issues with men. The grandmother then threatens to whip him and calls him a lusty boy before announcing that she loves him too much to hurt him. I think we need to pause for a few more coughs, uh huhs and maybe even an AHEM. Fortunately before this can all get even more awkward and uncomfortable (for the readers, that is), Jack finds the bean and plants it, less out of hope for wealth and more from a love of beans and bacon. In complete contrast to everything I’ve ever tried to grow, the plant immediately springs up smacking Jack in the nose and making him bleed. Instead of, you know, TRYING TO TREAT HIS NOSEBLEED the grandmother instead tries to kill him, which, look, I really think we need to have a discussion about some of the many, many unhealthy aspects of this relationship. Jack, however, has no time for that. He instead runs up the beanstalk, followed by his infuriated grandmother, who then falls off the beanstalk, turns into a toad, and crawls into a basement—which seems to be a bit of an overreaction.

Jack, however, has no time for that. He instead runs up the beanstalk, followed by his infuriated grandmother, who then falls off the beanstalk, turns into a toad, and crawls into a basement—which seems to be a bit of an overreaction.

In the meantime, the beanstalk has now grown 40 miles high and already attracting various residents, inns, and deceitful landlords who claim to be able to provide anything in the world but when directly asked, admit that they don’t actually have any mutton, veal, or beef on hand. All Jack ends up getting is some beer.

Which, despite being just brewed, must be amazing beer, since just as he drinks it, the roof flies off, the landlord is transformed into a beautiful lady, with a hurried, confusing and frankly not all that convincing explanation that she used to be his grandmother’s cat. As I said, amazing beer. Jack is given the option of ruling the entire world and feeding the lady to a dragon. Jack, sensibly enough under the circumstances, just wants some food. Various magical people patiently explain that if you are the ruler of the entire world, you can just order some food. Also, if Jack puts on a ring, he can have five wishes. It will perhaps surprise no one at this point that he wishes for food, and, after that, clothing for the lady, music, entertainment, and heading to bed with the lady. The story now pauses to assure us that the bed in question is well equipped with chamberpots, which is a nice realistic touch for a fairy tale. In the morning, they have more food—a LOT more food—and are now, apparently, a prince and princess—and, well. There’s a giant, who says:

Various magical people patiently explain that if you are the ruler of the entire world, you can just order some food. Also, if Jack puts on a ring, he can have five wishes. It will perhaps surprise no one at this point that he wishes for food, and, after that, clothing for the lady, music, entertainment, and heading to bed with the lady. The story now pauses to assure us that the bed in question is well equipped with chamberpots, which is a nice realistic touch for a fairy tale. In the morning, they have more food—a LOT more food—and are now, apparently, a prince and princess—and, well. There’s a giant, who says:

Fee, fow, fum—

I smell the blood of an English-Man,

Whether he be alive or dead,

I’ll grind his Bones to make my Bread.

I would call this the first appearance of the rather well known Jack and the Beanstalk rhyme, if it hadn’t been mostly stolen from King Lear. Not bothering to explain his knowledge of Shakespeare, the giant welcomes the two to the castle, falls instantly in love with the princess, but lets them fall asleep to the moaning of many virgins. Yes. Really. The next morning, the prince and princess eat again (this is a story obsessed with food), defeat the giant, and live happily ever after—presumably on top of the beanstalk. I say presumably, since at this point the author seems to have entirely forgotten the beanstalk or anything else about the story, and more seems interested in swiftly wrapping things up so he can go and complain about ghosts.

Yes. Really. The next morning, the prince and princess eat again (this is a story obsessed with food), defeat the giant, and live happily ever after—presumably on top of the beanstalk. I say presumably, since at this point the author seems to have entirely forgotten the beanstalk or anything else about the story, and more seems interested in swiftly wrapping things up so he can go and complain about ghosts.

Merryman claimed to have heard portions of this story from an old nurse, presumably in childhood, and the story does have a rather childlike lack of logic to it, particularly as it springs from event to event with little explanation, often forgetting what happened before. The focus on food, too, is quite childlike. But with all of the talk of virgins, bedtricks, heading to bed, sounds made in bed, and violence, not to mention all of the rest of the book, this does not seem to be a book meant for children. Rather, it is a book that looks back nostalgically at a better, happier time—read: prior to the reign of the not overly popular George II of Great Britain. I have no proof that Merryman, whatever his real name was, participated in the Jacobite rebellion that would break out just a couple of years after this book’s publication, but I can say he would have felt at least a small tinge of sympathy, if not more, for that cause. It’s a book that argues that the wealthy are not fulfilling their social responsibilities, that hints darkly that the wealthy can be easily overthrown, and replaced by those deemed socially inferior.

I have no proof that Merryman, whatever his real name was, participated in the Jacobite rebellion that would break out just a couple of years after this book’s publication, but I can say he would have felt at least a small tinge of sympathy, if not more, for that cause. It’s a book that argues that the wealthy are not fulfilling their social responsibilities, that hints darkly that the wealthy can be easily overthrown, and replaced by those deemed socially inferior.

So how exactly did this revolutionary tale get relegated to the nursery?

We’ll chat about that next week.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

citation

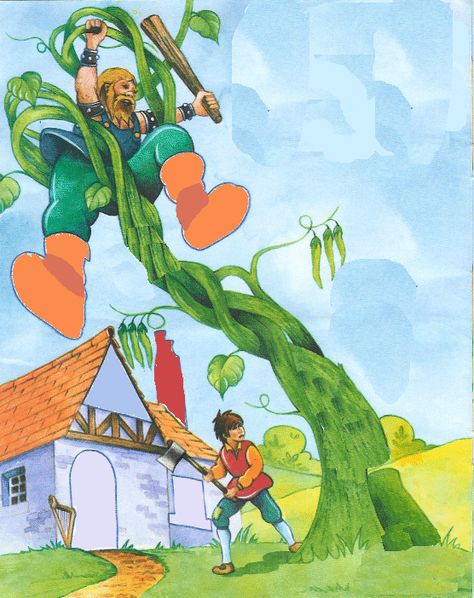

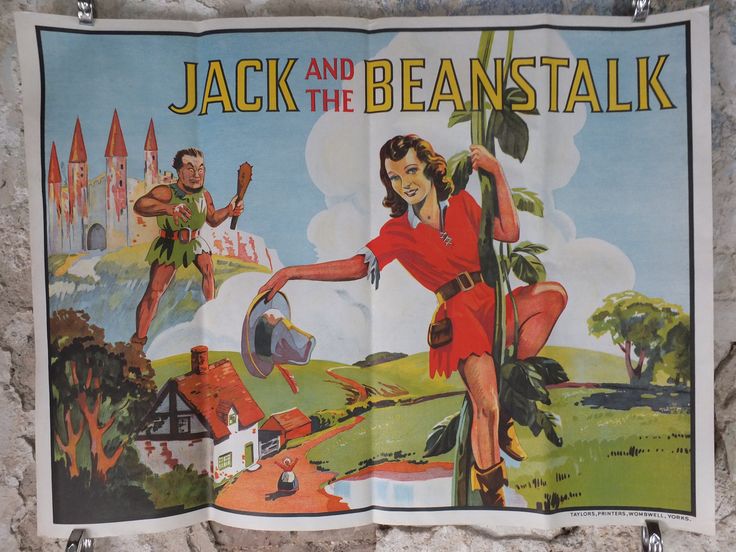

Jack and the Beanstalk - An old English Fairy Tale

Posted in Arthur Rackham, English Fairy Tales, Fortnightly Fairy Tales, Joseph Jacobs Fairy Tales, Story Time

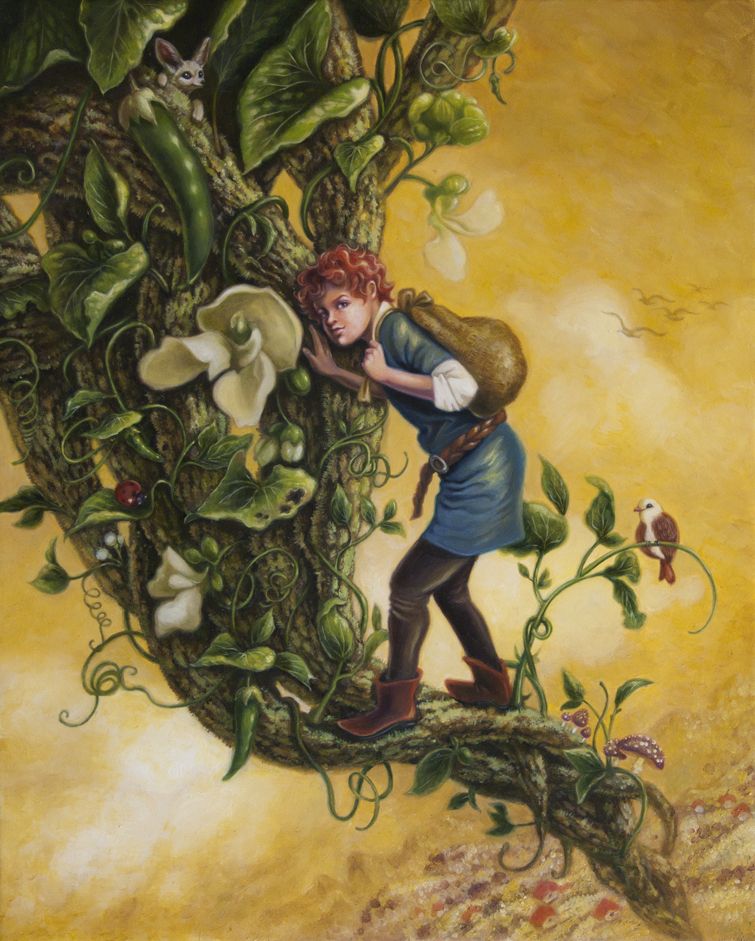

Jack and the Beanstalk is an old English fairy tale. It has been written many, many time by different folklorists and storytellers throughout history. Early appearances include The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean in 1734 and Benjamin Tabart’s The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk in 1807. Joseph Jacobs also collected it in his English Fairy Tales in 1890. His version is most well known today and it is believed to be closer to the original oral versions. This 1918 version here is retold by Flora Annie Steel, who published a beautiful collection of 41 English Fairy Tales illustrated by Arthur Rackham.

Early appearances include The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean in 1734 and Benjamin Tabart’s The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk in 1807. Joseph Jacobs also collected it in his English Fairy Tales in 1890. His version is most well known today and it is believed to be closer to the original oral versions. This 1918 version here is retold by Flora Annie Steel, who published a beautiful collection of 41 English Fairy Tales illustrated by Arthur Rackham.

for magic in your inbox

to our Pook Press emails

An Old English Fairy Tale

A long long time ago, when most of the world was young and folk did what they liked because all things were good, there lived a boy called Jack.

His father was bed-ridden, and his mother, a good soul, was busy early morns and late eves planning and placing how to support her sick husband and her young son by selling the milk and butter which Milky-White, the beautiful cow, gave them without stint. For it was summer-time. But winter came on; the herbs of the fields took refuge from the frosts in the warm earth, and though his mother sent Jack to gather what fodder he could get in the hedgerows, he came back as often as not with a very empty sack; for Jack’s eyes were so often full of wonder at all the things he saw that sometimes he forgot to work!

For it was summer-time. But winter came on; the herbs of the fields took refuge from the frosts in the warm earth, and though his mother sent Jack to gather what fodder he could get in the hedgerows, he came back as often as not with a very empty sack; for Jack’s eyes were so often full of wonder at all the things he saw that sometimes he forgot to work!

So it came to pass that one morning Milk-White gave no milk at all—not one drain! Then the good hard-working mother threw her apron over her head and sobbed:

“What shall we do? What shall we do?”

Now Jack loved his mother; besides, he felt just a bit sneaky at being such a big boy, and doing so little to help, so he said, “Cheer up! Cheer up! I’ll go and get work somewhere.” And he felt as he spoke as if he would work his fingers to the bone; but the good woman shook her head mournfully.

“You’ve tried that before, Jack,” she said, “and nobody would keep you. You are quite a good lad but your wits go a-woolgathering. No, we must sell Milky-White and live on the money. It is no use crying over milk that is not here to spill!”

No, we must sell Milky-White and live on the money. It is no use crying over milk that is not here to spill!”

You see, she was a wise as well as a hard-working woman, and Jack’s spirits rose.

“Just so,” he cried. “We will sell Milky-White and be richer than ever. It’s an ill wind that blows no one good. So, as it is market-day, I’ll just take her there and we shall see what we shall see.”

“But—” began his mother.

“But doesn’t butter parsnips,” laughed Jack. “Trust me to make a good bargain.”

So, as it was washing-day, and her sick husband was more ailing than usual, his mother let Jack set off to sell the cow.

“Not less than ten pounds,” she bawled after him as he turned the corner.

Ten pounds, indeed! Jack had made up his mind to twenty! Twenty solid golden sovereigns!

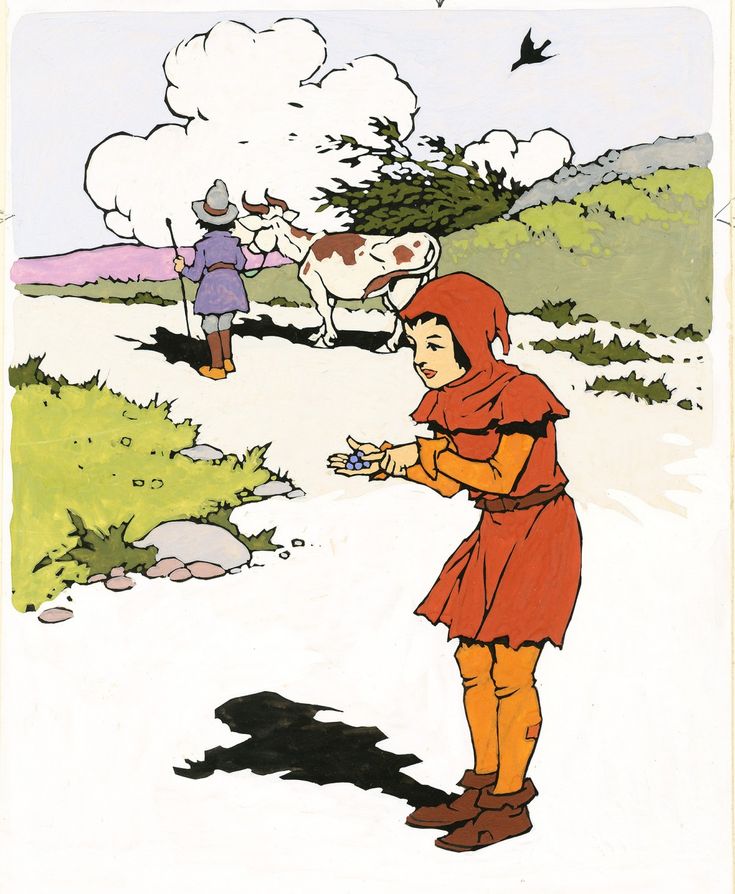

He was just settling what he should buy his mother as a fairing out of the money, when he saw a queer, little, old man on the road who called out, “Good-morning, Jack!”

“Good-morning,” replied Jack, with a polite bow, wondering how the queer, little, old man happened to know his name; though, to be sure, Jacks were as plentiful as blackberries.

“And where may you be going?” asked the queer, little, old man. Jack wondered again—he was always wondering, you know—what the queer, little, old man had to do with it; but, being always polite, he replied:

“I am going to market to sell Milky-White—and I mean to make a good bargain.”

“So you will! So you will!” chuckled the queer, little, old man. “You look the sort of chap for it. I bet you know how many beans make five?”

“Two in each hand and one in my mouth,” answered Jack readily. He really was sharp as a needle.

“Just so, just so!” chuckled the queer, little, old man; and as he spoke he drew out of his pocket five beans. “Well, here they are, so give us Milky-White.”

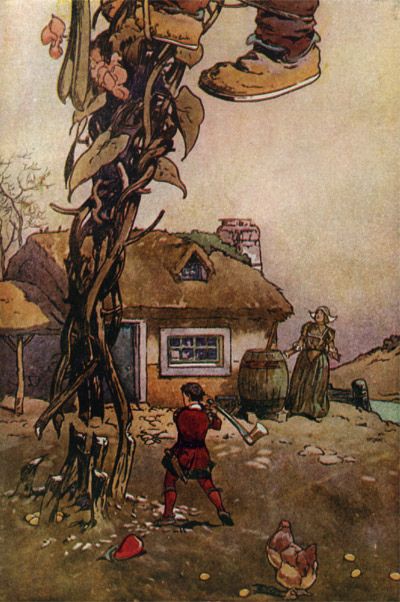

Jack and the Beanstalk, from English Fairy Tales illustrated by Arthur Rackham

Jack was so flabbergasted that he stood with his mouth open as if he expected the fifth bean to fly into it.

“What!” he said at last. “My Milky-White for five common beans! Not if I know it!”

“But they aren’t common beans,” put in the queer, little, old man, and there was a queer little smile on his queer little face. “If you plant these beans over-night, by morning they will have grown up right into the very sky.”

“If you plant these beans over-night, by morning they will have grown up right into the very sky.”

Jack was too flabbergasted this time even to open his mouth; his eyes opened instead.

“Did you say right into the very sky?” he asked at last; for, see you, Jack had wondered more about the sky than about anything else.

“Right up into the very sky,” repeated the queer old man, with a nod between each word. “It’s a good bargain, Jack; and, as fair play’s a jewel, if they don’t—Why! meet me here to-morrow morning and you shall have Milky-White back again. Will that please you?”

“Right as a trivet,” cried Jack, without stopping to think, and the next moment he found himself standing on an empty road.

“Two in each hand and one in my mouth,” repeated Jack. “That is what I said, and what I’ll do. Everything in order, and if what the queer, little, old man said isn’t true, I shall get Milky-White back to-morrow morning.”

So whistling and munching the bean he trudged home cheerfully, wondering what the sky would be like if he ever got there.

“What a long time you’ve been!” exclaimed his mother, who was watching anxiously for him at the gate. “It is past sun-setting; but I see you have sold Milky-White. Tell me quick how much you got for her.”

“You’ll never guess,” began Jack.

“Laws-a-mercy! You don’t say so,” interrupted the good woman. “And I worritting all day lest they should take you in. What was it? Ten pounds—fifteen—sure it can’t be twenty!”

Jack held out the beans triumphantly.

“There,” he said. “That’s what I got for her, and a jolly good bargain too!”

It was his mother’s turn to be flabbergasted; but all she said was:

“What! Them beans!”

“Yes,” replied Jack, beginning to doubt his own wisdom; “but they’re magic beans. If you plant them over-night, by morning they—grow—right up—into—the—sky—Oh! Please don’t hit so hard!”

For Jack’s mother for once had lost her temper, and was belabouring the boy for all she was worth. And when she had finished scolding and beating, she flung the miserable beans out of window and sent him, supperless, to bed.

If this was the magical effect of the beans, thought Jack ruefully, he didn’t want any more magic, if you please.

However, being healthy and, as a rule, happy, he soon fell asleep and slept like a top.

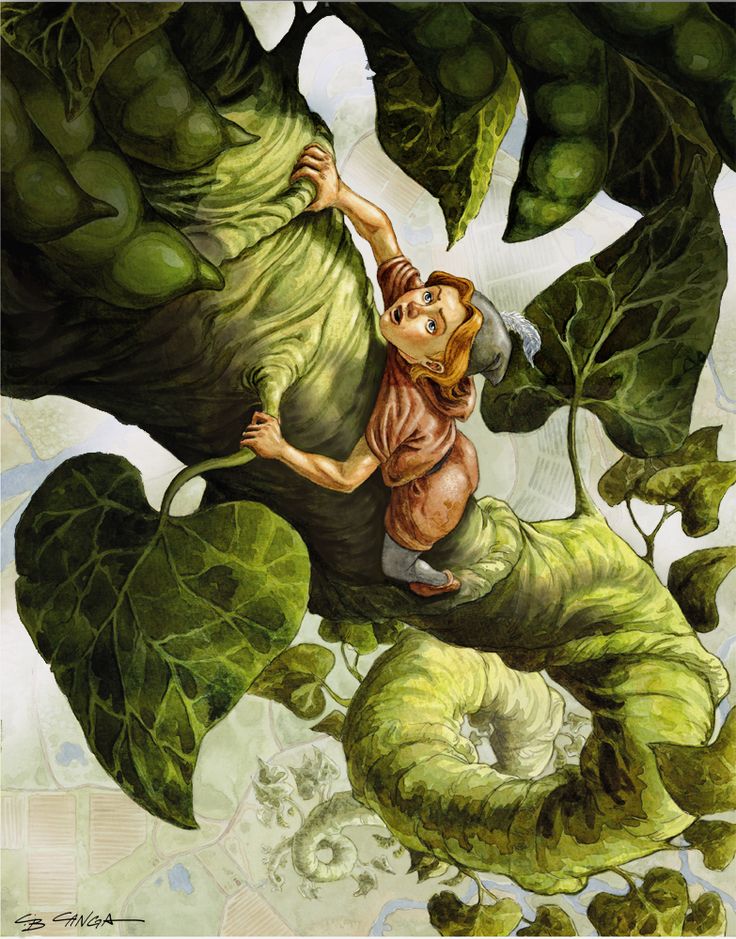

When he woke he thought at first it was moonlight, for everything in the room showed greenish. Then he stared at the little window. It was covered as if with a curtain by leaves. He was out of bed in a trice, and the next moment, without waiting to dress, was climbing up the biggest beanstalk you ever saw. For what the queer, little, old man had said was true! One of the beans which his mother had chucked into the garden had found soil, taken root, and grown in the night. . . .

Where? . . .

Up to the very sky? Jack meant to see at any rate.

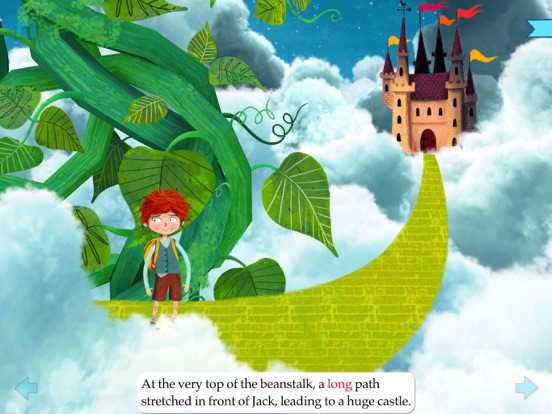

So he climbed, and he climbed, and he climbed. It was easy work, for the big beanstalk with the leaves growing out of each side was like a ladder; for all that he soon was out of breath. Then he got his second wind, and was just beginning to wonder if he had a third when he saw in front of him a wide, shining white road stretching away, and away, and away.

for magic in your inbox

to our Pook Press emails

So he took to walking, and he walked, and walked, and walked, till he came to a tall shining white house with a wide white doorstep.

And on the doorstep stood a great big woman with a black porridge-pot in her hand. Now Jack, having had no supper, was hungry as a hunter, and when he saw the porridge-pot he said quite politely:

“Good morning, I wonder if you could give me some breakfast?”

“Breakfast!” echoed the woman, who, in truth, was an ogre’s wife. “If it is breakfast you’re wanting, it’s breakfast you’ll likely be; for I expect my man home every instant, and there is nothing he likes better for breakfast than a boy—a fat boy grilled on toast.”

Now Jack was not a bit of a coward, and when he wanted a thing he generally got it, so he said cheerful-like:

“I’d be fatter if I’d had my breakfast!” Whereat the ogre’s wife laughed and bade Jack come in; for she was not, really, half as bad as she looked. But he had hardly finished the great bowl of porridge and milk she gave him when the whole house began to tremble and quake. It was the ogre coming home!

But he had hardly finished the great bowl of porridge and milk she gave him when the whole house began to tremble and quake. It was the ogre coming home!

“Fee-fi-fo-fum, I smell the blood of an Englishman”

Thump! THUMP!! THUMP!!!

“Into the oven with you, sharp!” cried the ogre’s wife; and the iron oven door was just closed when the ogre strode in. Jack could see him through the little peep-hole slide at the top where the steam came out.

Jack and the Beanstalk, from English Fairy Tales illustrated by Arthur Rackham

He was a big one for sure. He had three sheep strung to his belt, and these he threw down on the table. “Here, wife,” he cried, “roast me these snippets for breakfast; they are all I’ve been able to get this morning, worse luck! I hope the oven’s hot?” And he went to touch the handle, while Jack burst out all of a sweat wondering what would happen next.

“Roast!” echoed the ogre’s wife. “Pooh! the little things would dry to cinders. Better boil them.”

Better boil them.”

So she set to work to boil them; but the ogre began sniffing about the room. “They don’t smell—mutton meat,” he growled. Then he frowned horribly and began the real ogre’s rhyme:

“Fee-fi-fo-fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman.

Be he alive, or be he dead,

I’ll grind his bones to make my bread,”

“Don’t be silly!” said his wife. “It’s the bones of the little boy you had for supper that I’m boiling down for soup! Come, eat your breakfast, there’s a good ogre!”

So the ogre ate his three sheep, and when he had done he went to a big oaken chest and took out three big bags of golden pieces. These he put on the table, and began to count their contents while his wife cleared away the breakfast things. And by and by his head began to nod, and at last he began to snore, and snored so loud that the whole house shook.

Then Jack nipped out of the oven and, seizing one of the bags of gold, crept away, and ran along the straight, wide, shining white road as fast as his legs would carry him till he came to the beanstalk. He couldn’t climb down it with the bag of gold, it was so heavy, so he just flung his burden down first, and, helter-skelter, climbed after it.

He couldn’t climb down it with the bag of gold, it was so heavy, so he just flung his burden down first, and, helter-skelter, climbed after it.

And when he came to the bottom there was his mother picking up gold pieces out of the garden as fast as she could; for, of course, the bag had burst.

“Laws-a-mercy me!” she says. “Wherever have you been? See! It’s been rainin’ gold!”

“No, it hasn’t,” began Jack. “I climbed up—” Then he turned to look for the beanstalk; but lo, and behold! it wasn’t there at all! So he knew, then, it was all real magic.

After that they lived happily on the gold pieces for a long time, and the bedridden father got all sorts of nice things to eat; but, at last, a day came when Jack’s mother showed a doleful face as she put a big yellow sovereign into Jack’s hand and bade him be careful marketing, because there was not one more in the coffer. After that they must starve.

That night Jack went supperless to bed of his own accord. If he couldn’t make money, he thought, at any rate he could eat less money. It was a shame for a big boy to stuff himself and bring no grist to the mill.

It was a shame for a big boy to stuff himself and bring no grist to the mill.

He slept like a top, as boys do when they don’t overeat themselves, and when he woke . . .

Hey, presto! the whole room showed greenish, and there was a curtain of leaves over the window! Another bean had grown in the night, and Jack was up it like a lamplighter before you could say knife.

This time he didn’t take nearly so long climbing until he reached the straight, wide, white road, and in a trice he found himself before the tall white house, where on the wide white steps the ogre’s wife was standing with the black porridge-pot in her hand.

And this time Jack was as bold as brass. “Good-morning, ’m,” he said. “I’ve come to ask you for breakfast, for I had no supper, and I’m as hungry as a hunter.”

“Go away, bad boy!” replied the ogre’s wife. “Last time I gave a boy breakfast my man missed a whole bag of gold. I believe you are the same boy.”

“Maybe I am, maybe I’m not,” said Jack, with a laugh. “I’ll tell you true when I’ve had my breakfast; but not till then.”

“I’ll tell you true when I’ve had my breakfast; but not till then.”

So the ogre’s wife, who was dreadfully curious, gave him a big bowl full of porridge; but before he had half finished it he heard the ogre coming—

Thump! T

HUMP! THUMP!“In with you to the oven,” shrieked the ogre’s wife. “You shall tell me when he has gone to sleep.”

This time Jack saw through the steam peep-hole that the ogre had three fat calves strung to his belt.

“Better luck to-day, wife!” he cried, and his voice shook the house. “Quick! Roast these trifles for my breakfast! I hope the oven’s hot?”

And he went to feel the handle of the door, but his wife cried out sharply:

“Roast! Why, you’d have to wait hours before they were done! I’ll broil them—see how bright the fire is!”

“Umph!” growled the ogre. And then he began sniffing and calling out:

“Fee-fi-fo-fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman.

Be he alive, or be he dead,

I’ll grind his bones to make my bread. ”

”

“Twaddle!” said the ogre’s wife. “It’s only the bones of the boy you had last week that I’ve put into the pig-bucket!”

“Umph!” said the ogre harshly; but he ate the broiled calves and then he said to his wife, “Bring me my hen that lays the magic eggs. I want to see gold.”

So the ogre’s wife brought him a great, big, black hen with a shiny red comb. She plumped it down on the table and took away the breakfast things.

Then the ogre said to the hen, “Lay!” and it promptly laid—what do you think?—a beautiful, shiny, yellow, golden egg!

“None so dusty, henny-penny,” laughed the ogre. “I shan’t have to beg as long as I’ve got you.” Then he said, “Lay!” once more; and lo and behold! there was another beautiful, shiny, yellow, golden egg!

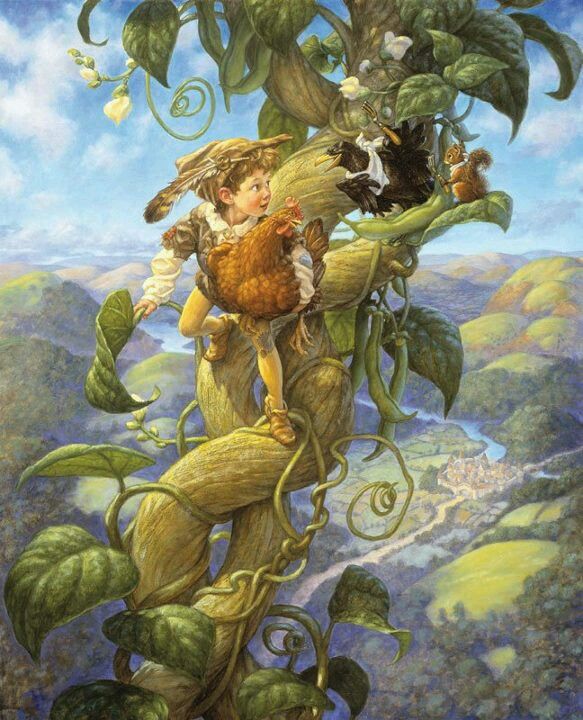

Jack could hardly believe his eyes, and made up his mind that he would have that hen, come what might. So, when the ogre began to doze, he just out like a flash from the oven, seized the hen, and ran for his life! But, you see, he reckoned without his prize; for hens, you know, always cackle when they leave their nests after laying an egg, and this one set up such a scrawing that it woke the ogre.

“Where’s my hen?” he shouted, and his wife came rushing in, and they both rushed to the door; but Jack had got the better of them by a good start, and all they could see was a little figure right away down the wide white road, holding a big, scrawing, cackling, fluttering, black hen by the legs!

How Jack got down the beanstalk he never knew. It was all wings, and leaves, and feathers, and cacklings; but get down he did, and there was his mother wondering if the sky was going to fall!

But the very moment Jack touched ground he called out, “Lay!” and the black hen ceased cackling and laid a great, big, shiny, yellow, golden egg.

So every one was satisfied; and from that moment everybody had everything that money could buy. For, whenever they wanted anything, they just said, “Lay!” and the black hen provided them with gold.

But Jack began to wonder if he couldn’t find something else besides money in the sky. So one fine, moonlight, midsummer night he refused his supper, and before he went to bed stole out to the garden with a big watering-can and watered the ground under his window; for, thought he, “there must be two more beans somewhere, and perhaps it is too dry for them to grow. ” Then he slept like a top.

” Then he slept like a top.

And lo, and behold! when he woke, there was the green light shimmering through his room, and there he was in an instant on the beanstalk, climbing, climbing, climbing for all he was worth.

But this time he knew better than to ask for his breakfast; for the ogre’s wife would be sure to recognize him. So he just hid in some bushes beside the great white house, till he saw her in the scullery, and then he slipped out and hid himself in the copper; for he knew she would be sure to look in the oven first thing.

And by and by he heard—

Thump! T

HUMP! THUMP!And peeping through a crack in the copper-lid he could see the ogre stalk in with three huge oxen strung at his belt. But this time, no sooner had the ogre got into the house than he began shouting:

“Fee-fi-fo-fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman.

Be he alive, or be he dead,

I’ll grind his bones to make my bread. ”

”

For, see you, the copper-lid didn’t fit tight like the oven door, and ogres have noses like a dog’s for scent.

“Well, I declare, so do I!” exclaimed the ogre’s wife. “It will be that horrid boy who stole the bag of gold and the hen. If so, he’s hid in the oven!”

But when she opened the door, lo, and behold! Jack wasn’t there! Only some joints of meat roasting and sizzling away. Then she laughed and said, “You and me be fools for sure. Why, it’s the boy you caught last night as I was getting ready for your breakfast. Yes, we be fools to take dead meat for live flesh! So eat your breakfast, there’s a good ogre!”

But the ogre, though he enjoyed roast boy very much, wasn’t satisfied, and every now and then he would burst out with “Fee-fi-fo-fum” and get up and search the cupboards, keeping Jack in a fever of fear lest he should think of the copper.

But he didn’t. And when he had finished his breakfast he called out to his wife, “Bring me my magic harp! I want to be amused. ”

”

So she brought out a little harp and put it on the table. And the ogre leant back in his chair and said lazily:

“Sing!”

And lo, and behold! the harp began to sing. If you want to know what it sang about! Why! It sang about everything! And it sang so beautifully that Jack forgot to be frightened, and the ogre forgot to think of “Fee-fi-fo-fum,” and fell asleep and

did

NOT

SNORE.

Then Jack stole out of the copper like a mouse and crept hands and knees to the table, raised himself up ever so softly and laid hold of the magic harp; for he was determined to have it.

But, no sooner had he touched it, than it cried out quite loud, “Master! Master!” So the ogre woke, saw Jack making off, and rushed after him.

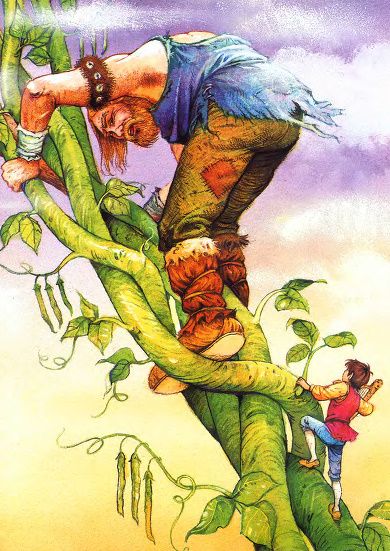

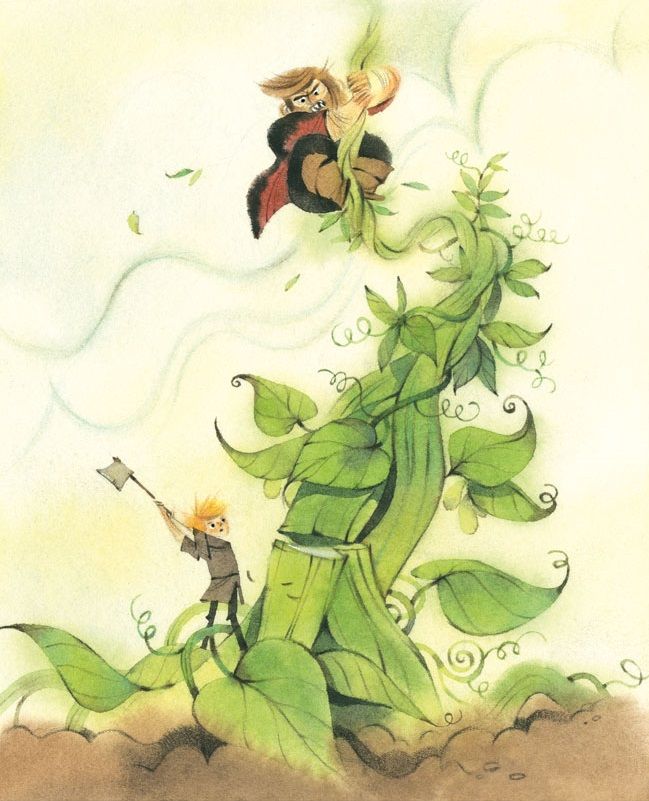

My goodness, it was a race! Jack was nimble, but the ogre’s stride was twice as long. So, though Jack turned, and twisted, and doubled like a hare, yet at last, when he got to the beanstalk, the ogre was not a dozen yards behind him. There wasn’t time to think, so Jack just flung himself on to the stalk and began to go down as fast as he could while the harp kept calling, “Master! Master!” at the very top of its voice. He had only got down about a quarter of the way when there was the most awful lurch you can think of, and Jack nearly fell off the beanstalk. It was the ogre beginning to climb down, and his weight made the stalk sway like a tree in a storm. Then Jack knew it was life or death, and he climbed down faster and faster, and as he climbed he shouted, “Mother! Mother! Bring an axe! Bring an axe!”

There wasn’t time to think, so Jack just flung himself on to the stalk and began to go down as fast as he could while the harp kept calling, “Master! Master!” at the very top of its voice. He had only got down about a quarter of the way when there was the most awful lurch you can think of, and Jack nearly fell off the beanstalk. It was the ogre beginning to climb down, and his weight made the stalk sway like a tree in a storm. Then Jack knew it was life or death, and he climbed down faster and faster, and as he climbed he shouted, “Mother! Mother! Bring an axe! Bring an axe!”

Now his mother, as luck would have it, was in the backyard chopping wood, and she ran out thinking that this time the sky must have fallen. Just at that moment Jack touched ground and he flung down the harp—which immediately began to sing of all sorts of beautiful things—and he seized the axe and gave a great chop at the beanstalk, which shook and swayed and bent like barley before a breeze.

Jack and the Beanstalk, from English Fairy Tales illustrated by Arthur Rackham

“Have a care!” shouted the ogre, clinging on as hard as he could. But Jack did have a care, and he dealt that beanstalk such a shrewd blow that the whole of it, ogre and all, came toppling down, and, of course, the ogre broke his crown, so that he died on the spot.

But Jack did have a care, and he dealt that beanstalk such a shrewd blow that the whole of it, ogre and all, came toppling down, and, of course, the ogre broke his crown, so that he died on the spot.

After that every one was quite happy. For they had gold and to spare, and if the bedridden father was dull, Jack just brought out the harp and said, “Sing!” And lo, and behold! it sang about everything under the sun.

So Jack ceased wondering so much and became quite a useful person.

And the last bean hasn’t grown yet. It is still in the garden.

I wonder if it will ever grow?

And what little child will climb its beanstalk into the sky?

And what will that child find?

Goody me!

Fairy Gold – A Book of Old English Fairy Tales – Illustrated by Herbert Cole

for magic in your inbox

to our Pook Press emails

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

90,000 Jack and the Beanstalk is an English fairy tale. The story of the boy Jack.

The story of the boy Jack. A tale about a poor widow's son, Jack, who traded his family's only breadwinner, a cow, for magic beans. With the help of them and their ingenuity, Jack and his mother got rich.

Once upon a time there lived a poor widow. She had an only son named Jack and a cow named Belyanka. The cow gave milk every morning, and the mother and son sold it in the bazaar - this is how they lived. But suddenly Belyanka stopped milking, and they simply did not know what to do.

— How can we be? What to do? the mother repeated in despair.

— Cheer up, mother! Jack said. - I'll get someone to work with.

— Yes, you already tried to get hired, but no one hires you, — answered the mother. “No, apparently, we will have to sell our Belyanka and open a shop with this money.

“Well, okay, Mom,” Jack agreed. - Today is just a market day, and I will quickly sell Belyanka. And then we'll decide what to do.

And Jack took the cow to the market. But he did not have time to go far when he met a funny, funny old man, and he said to him:0003

But he did not have time to go far when he met a funny, funny old man, and he said to him:0003

- Good morning, Jack!

— Good morning to you too! - Jack answered, and was surprised to himself: how does the old man know his name.

— Well, Jack, where are you going? asked the old man.

- To the market, to sell a cow.

— Yes, yes! Who should trade cows if not you! the old man laughed. “Tell me, how many beans do I have?”

- Exactly two in each hand and one in your mouth! - answered Jack, apparently, not a small mistake.

- That's right! said the old man. “Look, here are those beans!” And the old man showed Jack some strange beans. “Since you’re so smart,” the old man continued, “I’m not averse to trading with you—I’m giving these beans for your cow!”

— Go on your way! Jack got angry. “That would be better!”

"Uh, you don't know what beans are," said the old man. “Plant them in the evening, and by morning they will grow to the sky.

— Yes, well? Truth? Jack was surprised.

- The real truth! And if not, take your cow back.

- Coming! - Jack agreed, gave the old man Belyanka, and put the beans in his pocket.

Jack turned back home, and since he did not have time to go far from home, it was not dark yet, and he was already at his door.

- Are you back yet, Jack? mother was surprised. - I see Belyanka is not with you, so you sold her? How much did they give you for it?

— You'll never guess, Mom! Jack answered.

— Yes, well? Oh my good! Five pounds? Ten? Fifteen? Well, twenty something will not give!

- I said - you can't guess! What can you say about these beans? They are magical. Plant them in the evening and...

— What?! cried Jack's mother. “Are you really such a simpleton that you gave my Belyanka, the most milking cow in the whole area, for a handful of some bad beans?” It is for you! It is for you! It is for you! And your precious beans will fly out the window. So that! Now live to sleep! And don’t ask for food, you won’t get it anyway - not a piece, not a sip!

So that! Now live to sleep! And don’t ask for food, you won’t get it anyway - not a piece, not a sip!

And then Jack went up to his attic, to his little room, sad, very sad: he angered his mother, and he himself was left without supper. Finally, he did fall asleep.

And when he woke up, the room seemed very strange to him. The sun illuminated only one corner, and everything around remained dark, dark. Jack jumped out of bed, dressed and went to the window. And what did he see? What a strange tree! And these are his beans, which his mother threw out of the window into the garden the day before, sprouted and turned into a huge bean tree. It stretched all the way up, up and up to the sky. It turns out that the old man was telling the truth!

The beanstalk grew just outside Jack's window and went up like a real staircase. So Jack had only to open the window and jump onto the tree. And so he did. Jack climbed the beanstalk and climbed and climbed and climbed and climbed and climbed and climbed until he finally reached the sky. There he saw a long and wide road, as straight as an arrow. I went along this road and kept walking and walking and walking until I came to a huge, huge tall house. And at the threshold of this house stood a huge, enormous, tall woman.

There he saw a long and wide road, as straight as an arrow. I went along this road and kept walking and walking and walking until I came to a huge, huge tall house. And at the threshold of this house stood a huge, enormous, tall woman.

— Good morning, ma'am! Jack said very politely. “Be so kind as to give me breakfast, please!”

After all, the day before Jack had been left without supper, you know, and now he was as hungry as a wolf.

— Would you like to have breakfast? - said a huge, enormous, tall woman. “You yourself will get another for breakfast if you don’t get out of here!” My husband is a giant and a cannibal, and he loves nothing more than boys fried in breadcrumbs.

— Oh, madame, I beg you, give me something to eat! Jack didn't hesitate. “I haven’t had a crumb in my mouth since yesterday morning. And it doesn't matter if they fry me or I'll die of hunger.

Well, the ogre's wife was not a bad woman after all. So she took Jack to the kitchen and gave him a piece of bread and cheese and a jug of fresh milk. But before Jack had time to finish with half of all this, when suddenly - top! Top! Top! - the whole house even shook from someone's steps.

But before Jack had time to finish with half of all this, when suddenly - top! Top! Top! - the whole house even shook from someone's steps.

- Oh my God! Yes, that's my old man! gasped the giantess. - What to do? Hurry, hurry, jump over here!

And just as she pushed Jack into the oven, the ogre himself entered the house.

Well, he was really great! Three calves dangled from his belt. He untied them, threw them on the table and said:

— Come on, wife, fry me a couple for breakfast! Wow! What does it smell like?

Fi-fi-fo-foot,

I smell the spirit of the British here.

Whether he is dead or alive,

Will go to my breakfast.

— What are you, hubby! his wife told him. - You've got it. Or maybe it smells like that lamb that you liked so much yesterday at dinner. Come on, wash your face and change, and in the meantime I will prepare breakfast.

The ogre came out and Jack was about to get out of the oven and run away, but the woman wouldn't let him.

“Wait until he falls asleep,” she said. He always likes to take a nap after breakfast.

And so the giant had breakfast, then went to a huge chest, took out two sacks of gold from it and sat down to count the coins. He counted and counted, finally began to nod off and began to snore so that the whole house began to shake again.

Then Jack slowly got out of the oven, tiptoed past the sleeping ogre, grabbed one bag of gold and God bless! — straight to the beanstalk. He dropped the bag down into his garden, and he began to descend the stem, lower and lower, until at last he found himself at home.

Jack told his mother about everything, showed her a bag of gold and said:

— Well, Mom, did I tell the truth about these beans? You see, they are really magical!

“I don’t know what these beans are,” answered the mother, “but as for the cannibal, I think it’s the one who killed your father and ruined us!”

And I must tell you that when Jack was only three months old, a terrible ogre appeared in their area. He grabbed anyone, but especially did not spare the kind and generous people. And Jack's father, although he was not rich himself, always helped the poor and the losers.

He grabbed anyone, but especially did not spare the kind and generous people. And Jack's father, although he was not rich himself, always helped the poor and the losers.

“Oh, Jack,” the mother finished, “to think that the cannibal could eat you too!” Don't you dare climb that stem ever again!

Jack promised, and they lived with their mother in full contentment with the money that was in the bag.

But in the end the bag was empty, and Jack, forgetting his promise, decided to try his luck at the top of the beanstalk one more time. One fine morning he got up early and climbed the beanstalk. He climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, until he finally found himself on a familiar road and reached along it to a huge, enormous tall house. Like last time, a huge, enormous, tall woman was standing at the threshold.

“Good morning, ma'am,” Jack told her as if nothing had happened. “Be so kind as to give me something to eat, please!”

- Get out of here, little boy! the giantess replied. “Or my husband will eat you at breakfast.” Uh, no, wait a minute, aren't you the youngster who came here recently? You know, on that very day my husband missed one sack of gold.

“Or my husband will eat you at breakfast.” Uh, no, wait a minute, aren't you the youngster who came here recently? You know, on that very day my husband missed one sack of gold.

— These are miracles, ma'am! Jack says. “It’s true, I could tell you something about it, but I’m so hungry that until I eat at least a piece, I won’t be able to utter a word.

The giantess was so curious that she let Jack into the house and gave him something to eat. And Jack deliberately began to chew slowly, slowly. But suddenly - top! Top! Top! they heard the steps of the giant, and the kind woman again hid Jack in the oven.

Everything happened just like last time. The ogre came in and said: “Fi-fi-fo-foot…” and so on, had breakfast with three roasted bulls, and then ordered his wife:

- Wife, bring me a chicken - the one that lays the golden eggs!

The giantess brought it, and he said to the hen: “Come on!” And the hen laid a golden egg. Then the cannibal began to nod and began to snore so that the whole house shook.

Then Jack slowly got out of the oven, grabbed the golden hen and was out the door in no time. But then the hen cackled and woke up the ogre. And just as Jack was running out of the house, he heard the giant's voice behind him:

— Wife, leave the golden hen alone! And the wife answered:

- Why are you, my dear!

That's all Jack could hear. He rushed with all his might to the beanstalk and almost flew down it.

Jack returned home, showed his mother the miracle chicken and shouted: "Go!" And the hen laid a golden egg.

Since then, every time Jack told her, "Rush!" The hen laid a golden egg.

Mother scolded Jack for disobeying her and going to the cannibal again, but she still liked the chicken.

And Jack, a restless guy, after a while decided to try his luck again at the top of the beanstalk. One fine morning he got up early and climbed the beanstalk.

He climbed and climbed and climbed and climbed until he reached the very top. True, this time he acted more carefully and did not go straight to the cannibal's house, but crept up slowly and hid in the bushes. I waited until the giantess came out with a bucket for water, and darted into the house! I climbed into the copper cauldron and waited. He didn’t wait long, suddenly he hears the familiar “top! Top! Top!", and now the ogre and his wife enter the room.

True, this time he acted more carefully and did not go straight to the cannibal's house, but crept up slowly and hid in the bushes. I waited until the giantess came out with a bucket for water, and darted into the house! I climbed into the copper cauldron and waited. He didn’t wait long, suddenly he hears the familiar “top! Top! Top!", and now the ogre and his wife enter the room.

- Fi-fi-fo-foot, I smell the spirit of the British here! shouted the cannibal. “I can smell it, wife!”

— Can you really hear it, hubby? says the giantess. “Well, then, this is the tomboy who stole your gold and the goose with golden eggs. He's probably in the oven.

And both rushed to the stove. Good thing Jack wasn't hiding there!

- Always you with your fi-fi-fo-foot! grumbled the ogre's wife, and began preparing breakfast for her husband.

The ogre sat down at the table, but still could not calm down and kept mumbling:

— Still, I can swear that… — He jumped up from the table, rummaged through the pantry, and chests, and sideboards…

He searched all the corners, only he didn’t guess to look into the copper cauldron. Finally finished breakfast and shouted:

Finally finished breakfast and shouted:

- Hey, wife, bring me a golden harp! The wife brought the harp and put it on the table.

- Sing! the giant ordered the harp.

And the golden harp sang so well that you will hear it! And she sang and sang until the ogre fell asleep and snored like thunder.

It was then that Jack lightly lifted the lid of the cauldron. He got out of it quietly, quietly, like a mouse, and crawled on all fours to the very table. He climbed onto the table, grabbed the harp, and rushed to the door.

But the harp called loudly:

— Master! Master!

The ogre woke up and immediately saw Jack running away with his harp.

Jack ran headlong, and the giant followed him. It cost him nothing to catch Jack, but Jack was the first to run, and therefore he managed to dodge the giant. And besides, he knew the road well. When he reached the bean tree, the ogre was only twenty paces away. And suddenly Jack was gone. Cannibal here, there - no Jack! Finally, he thought to look at the beanstalk and sees: Jack is trying with his last strength, crawling down. The giant was afraid to go down the shaky stalk, but then the harp called again:0003

The giant was afraid to go down the shaky stalk, but then the harp called again:0003

- Master! Master!

And the giant just hung on the beanstalk, and the beanstalk trembled all under its weight.

Jack descends lower and lower, and the giant follows him. But now Jack is right above the house. Then he screams:

- Mom! Mother! Bring the ax! Bring the ax!

Mother ran out with an ax in her hands, rushed to the beanstalk, and froze in horror: huge legs of a giant stuck out of the clouds.

But then Jack jumped down to the ground, grabbed an ax and hacked at the beanstalk so hard that he almost cut it in half.

The ogre felt the stalk swaying and shaking and stopped to see what had happened. Here Jack strikes with an ax again and completely cuts the beanstalk. The stalk swayed and collapsed, and the ogre fell to the ground and twisted his neck.

Jack gave his mother a golden harp, and they began to live without grieve. And they did not remember about the giant.

Jack and the Magic Bean - frwiki.wiki

For the articles of the same name, see Jack and the Magic Bean (disambiguation).

Jack and the Beanstalk ( Jack and the Beanstalk ) is a fairy tale popular in English.

It bears some resemblance to Jack the Giant Slayer , another Cornish hero tale. The origin of Jack and Beanstalk is unknown. We can see in the parodic version which appeared in the first half of the XVIII - th century the first literary version of the story. In 1807, Benjamin Tabart published in London a moralizing version closer to what is known today. Subsequently, Henry Cole popularized this story in "To the Home Treasury" (1842) and Joseph Jacobs gave another version in English Tales (1890). The latter is the version most often reproduced in English-language collections today, and due to its lack of morality and "dry" literary treatment, it is often considered a truer oral version than Tabart's. However, there can be no certainty in this matter.

However, there can be no certainty in this matter.

Jack and the Beanstalk is one of the most famous folk tales and has been the subject of many adaptations in various forms until today.

Resume

- 1 First printed versions

- 2 Summary (Jacobs version)

- 3 variants

- 4 Structure

- 5 Classification

- 6 Fee-fi-fo-fum formula

- 7 parallels in other fairy tales

- 8 Patterns and ancient origin of these

- 9 Morality

- 10 interpretations

- 11 Illustrations

- 12 Modern adaptations

- 12.1 Cinema

- 12.2 Television and video

- 12.3 Video games

- 12.4 Exhibitions

- 13 Notes and references

- 14 Bibliography

- 14.1 Versions / editions of fairy tale

- 14.2 Research

- 14.3 Symbolic

- 14.4 About adaptation

- 15 See also

- 15.

1 Related Articles

1 Related Articles

- 15.

First printed versions

The origin of this tale is not exactly known, but it is believed to have British roots.

According to Iona and Peter Opie, the first literary version of the tale is The Charm Shown in the Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean , which appears in the 1734 English edition of Round of Our Coal Fire or Christmas Amusements . The collection, which includes the First Edition, which did not include the tale, dates from 1730. Then this is a parody version that makes fun of the fairy tale, but nevertheless testifies on the part of the author of a good knowledge of the traditional fairy tale.

Frontispiece (" Jack Fleeing the Giant ") and title page of The Jack and the Beanstalk Story , B. Tabart, London, 1807 when two books were published: Mother Twaddle's Story and Her Son Jack's Wonderful Achievements with the single initials " Bat " as the author's name. and Jack and Bob's Story , published in London by Benjamin Tabart. In the first case, this is a poetic version, which differs significantly from the known version: a servant takes Jack to the giant's house, and she gives the latter beer to put him to sleep; as soon as the giant falls asleep, Jack decapitates him; He then marries a maid and sends for his mother. Another version, whose title page states that it is a version "printed from an original manuscript, never before published", is closer to the tale as we know it today, except that it has a fairy character, which gives the moral of the story.

and Jack and Bob's Story , published in London by Benjamin Tabart. In the first case, this is a poetic version, which differs significantly from the known version: a servant takes Jack to the giant's house, and she gives the latter beer to put him to sleep; as soon as the giant falls asleep, Jack decapitates him; He then marries a maid and sends for his mother. Another version, whose title page states that it is a version "printed from an original manuscript, never before published", is closer to the tale as we know it today, except that it has a fairy character, which gives the moral of the story.

In 1890 Joseph Jacobs reported in English Tales a version of Jack and the Beanstalk which he said was based on "oral versions heard in his boyhood in Australia about 1860" and in which he took the side of "ignoring excuse". given by Tabart for Jack who killed the giant. Subsequently, other versions of the tale will follow sometimes Tabart, who therefore justifies the hero's actions, sometimes Jacobs, who presents Jack as a steadfast deceiver. So Andrew Lang at The Red Book of the Fairies , also published in 1890, follows Tabart. From Tabart/Lang or Jacobs, it is difficult to determine which of the two versions is closer to the oral version: while specialists such as Katherine Briggs, Philip Neal or Maria Tatar prefer Jacobs' version, others such as Jonah and Peter Opie consider it should be “nothing but a reworking of a text that has continued to be printed for more than half a century. "

So Andrew Lang at The Red Book of the Fairies , also published in 1890, follows Tabart. From Tabart/Lang or Jacobs, it is difficult to determine which of the two versions is closer to the oral version: while specialists such as Katherine Briggs, Philip Neal or Maria Tatar prefer Jacobs' version, others such as Jonah and Peter Opie consider it should be “nothing but a reworking of a text that has continued to be printed for more than half a century. "

Jack trades his cow for beans. Illustration by Walter Crane.

Summary (Jacobs version)

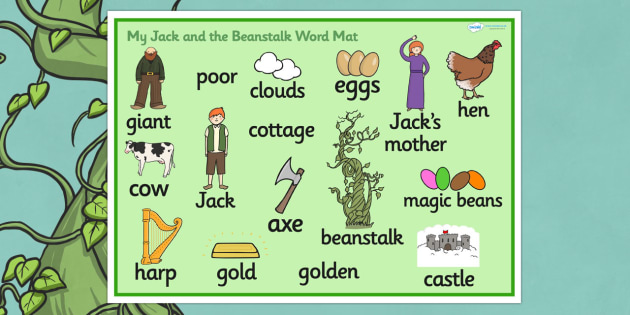

In Jacobs' version of the tale, Jack is a boy who lives alone with his widowed mother. Their only source of existence is milk from a single cow. One morning they realize that their cow is no longer producing milk. Jack's mother decides to send her son to sell her in the market.

Along the way, Jack meets a strange looking old man who greets Jack by his first name. He manages to convince Jack to trade his cow for beans, he says "magic": if we plant them at night, in the morning they will grow to heaven! When Jack returns home with no money but only a handful of beans, his mother gets angry and throws the beans out the window. She punishes her son for his gullibility by sending him to bed without supper.

She punishes her son for his gullibility by sending him to bed without supper.

« Fee-foo-foom, I can smell the Englishman's blood. ". Arthur Rackham's illustration from English Tales by Flora Annie Steele, 1918.

While Jack sleeps, beans sprout from the ground, and by morning a giant stalk of beans has grown in the place where they were thrown. , Jack sees a huge rod rising into the sky and decides to immediately climb to its top.

At the top he finds a broad road which he chooses and which leads him to a large house. On the threshold of a large house stands a large woman. Jack asks her to offer him dinner, but the woman warns him: her husband is a cannibal, and if Jack doesn't turn around, he risks serving dinner to her husband. Jack insists, and the giantess cooks a meal for him. Jack is not halfway to the meal when footsteps are heard, causing the whole house to shake. The giantess hides Jack in the oven. The ogre appears and immediately senses the presence of a human:

« F-f-f-fum!

I smell the blood of an Englishman,

whether he is alive or dead,

I will have his bones to grind my bread."

What does it mean:

« Phi-fi-fo-foom!

I sniff the blood of an Englishman,

Dead or alive,

I have to grind his bones to make bread. "

The ogre's wife tells him that he has his own thoughts and that the smell he smells is probably the smell of the remains of a little boy that he enjoyed the day before. The ogre leaves, and as Jack is ready to jump out of his hiding place and wrap his legs around his neck, the giantess tells him to wait until her husband naps. After the ogre swallows, Jack sees him take some bags from the chest and count the gold coins in them until he falls asleep. So Jack tiptoes out of the oven and runs off carrying one of the bags of gold. He descends the bean stalk and brings gold to his mother.

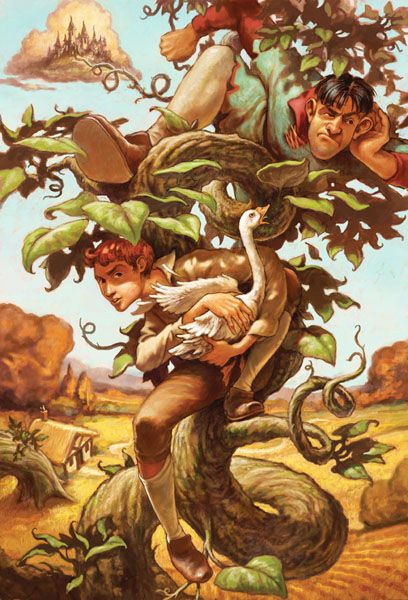

Jack escapes for the third time, carrying a magical harp. The ogre is on his trail. Illustration by Walter Crane.

Gold allows Jack and his mother to live for a while, but there comes a time when it all disappears and Jack decides to return to the top of the bean stalk. On the threshold of a large house, he again finds the giantess. She asks him if he had already arrived the day her husband noticed one of her bags of gold was missing. Jack tells her that he is hungry and cannot talk to her until he has eaten. The giantess prepares food for him again ... Everything goes like last time, but this time Jack manages to steal a goose that every time we say "ponds" lays a golden egg. He returns her to his mother.

On the threshold of a large house, he again finds the giantess. She asks him if he had already arrived the day her husband noticed one of her bags of gold was missing. Jack tells her that he is hungry and cannot talk to her until he has eaten. The giantess prepares food for him again ... Everything goes like last time, but this time Jack manages to steal a goose that every time we say "ponds" lays a golden egg. He returns her to his mother.

Soon an unsatisfied Jack feels the urge to climb back to the top of the bean stalk. So the third time he climbs up the stick, but instead of going straight to the big house, when he comes to it, he hides behind a bush and waits before entering the house. Ogre, that giantess went out for water. There is another cache in the house, in a "pot". A couple of giants are back. Once again, the ogre senses Jack's presence. The giantess then tells her husband to look in the oven because that's where Jack used to hide. Jack is gone and they think it is the smell of the woman the ogre ate the day before. After dinner, the ogre asks his wife to bring him a golden harp. The harp sings until the ogre falls asleep, and Jack takes the opportunity to get out of his hiding place. When Jack grabs the harp, she calls her master an ogre with a human voice, and the ogre wakes up. The ogre chases Jack, who has grabbed the harp, towards the beanstalk. The ogre comes down the rod behind Jack, but as soon as Jack goes down, he quickly asks his mother to give him an ax with which he cuts the huge rod. The ogre falls and "breaks his crown".

After dinner, the ogre asks his wife to bring him a golden harp. The harp sings until the ogre falls asleep, and Jack takes the opportunity to get out of his hiding place. When Jack grabs the harp, she calls her master an ogre with a human voice, and the ogre wakes up. The ogre chases Jack, who has grabbed the harp, towards the beanstalk. The ogre comes down the rod behind Jack, but as soon as Jack goes down, he quickly asks his mother to give him an ax with which he cuts the huge rod. The ogre falls and "breaks his crown".

Jack shows his mother a golden harp, and thanks to her and the sale of golden eggs, they both become very rich. Jack marries a great princess. And then they live happily ever after?

Variants

Three flights are missing from the 1734 parody version and the 1807 "BAT" version, but not from the bean stalk. In Tabart's version (1807), Jack, upon arriving in the giant's realm, learns from an old woman that his father's property had been stolen by the giant.

Composition

- Introduction: Jack and his mother are poor, but their cow gives milk.

- Misfortune → Mission: The cow no longer gives milk

- Encounter → Magic Offer ← Earth Mission Failure: Jack meets a "wizard" - Jack accepts magic and trades a cow for one or more beans.

- Earth Sanction: Jack is punished, deprived of food (Jack is hungry). NIGHT: Jack sleeps.

- The magic happens: a stalk of a giant bean is found in the morning.

- Sky World:

- 1- e visit / 1- flight (Jack is very hungry): (a) Man-eating Jack's wife protects and hides in the oven - (b) Ogre senses Jack: Phi-Pho- fum! ("Chorus formula") - (c) Jack takes the bag of gold - (d) Ogre is unaware.

- 2- e visiting / 2- e stealing (Jack is hungry): (a) The ogre's wife doubts Jack and hides him in spite of everything in the oven - (b) Fi-fi-fo-foom! - (c) Jack takes the goose that lays the golden eggs - (d) Ogre in his house almost catches up with Jack.

- 3 - visit / 3 e flight (Jack wants to find other treasures): (a) Jack is hiding in a pot - (b) Fee-fo-fum! - (a ') Ogre's wife denounces Jack - (c) Jack takes golden harp - (d) Ogre pursues Jack to wand.

- Conclusion: Fall and death of the ogre - Jack and his mother are rich and happy.

This plan includes several progressions, each of which takes place in three stages: in the earthly world, hunger becomes more acute (cash cow → beans → "going to bed without supper"), and in the heavenly world, hunger subsides until finally turns into a desire for more wealth, the ogre's wife gradually separates from Jack, and finally the danger posed by the ogre becomes more and more concrete.

Classification

Ogre fall. Illustration by Walter Crane.

Illustration by Walter Crane.

The tale is usually kept in Aarne-Thompson tales AT 328, corresponding to the type "The boy who steals the ogre's treasure". However, one of the main elements of the tale, namely the bean stalk, does not occur in other tales in this category. Beanstalk , similar to the one that appears in Jack and the Beanstalk , is found in other typical tales such as AT 563, "Three Magic Objects" and AT 555, "The Fisherman and His Wife". Bean Ogre's fall, on the other hand, seems to be unique to Jack .

Formula "Fi-fi-fo-fum"

The formula appears in some versions of the story by Jack the Giant Killer ( XVIII - th cc), and earlier, in Shakespeare's play King Lear (v.1605). We find echoes of this in the Russian fairy tale about Vasilisa the Most Beautiful , where the witch shouts: “Crazy! It smells like Russian here! (Crazy, Fu means "Phi! Pah!" In Russian).

Parallels in other tales

Among other similar tales, such as AT 328 "The Boy Stealing the Ogre's Treasure", we find in particular the Italian tale "The Thirteenth" and the Greek tale How the Dragon was Deceived . Corvetto , a tale that appeared in Giambattista Basile's Pentamerone (1634–1636), is also part of this type. It is about a young courtier who enjoys the favor of the king (of Scotland) and is the envy of the other courtiers, who therefore look for a way to get rid of him. Not far from there, in a fortified castle perched atop a mountain, lives an ogre, who is served by an army of animals and who keeps certain treasures that the king is likely to desire. The enemies of Corvetto force the king to send a young man in search of a cannibal, first a talking horse, then a tapestry. When a young man enters two victorious cases of his mission, they see to it that the king orders him to capture the ogre's castle. To complete this third mission, Corvetto introduces himself to the ogre's wife, who is busy preparing a feast; he offers to help her in her task, but instead kills her with an axe. Corvetto then manages to knock the ogre and all the guests of the feast into a hole dug in front of the castle gates. As a reward, the king finally extends the hand of his daughter to the young hero.

Corvetto then manages to knock the ogre and all the guests of the feast into a hole dug in front of the castle gates. As a reward, the king finally extends the hand of his daughter to the young hero.

The Brothers Grimm note the analogies between Jack and the Beanstalk and the German fairy tale The Devil's Three Golden Hairs (KGM 29), in which the devil's mother or grandmother acts in a manner quite comparable to the behavior of the ogre's wives in Jack : a female figure, protecting the child from an evil male figure. In the version of the tale "Petit Puse" (1697), Perrault's wife also comes to the aid of Puse and his brothers.

The theme of a giant plant serving as a magical staircase between the earthly world and the heavenly world is also found in other fairy tales, especially in Russian ones, for example, in Doctor Fox .

The tale is unusual in that in some versions the hero, although an adult, does not marry at the end, but returns to his mother. This feature occurs only in a small number of other tales, such as some variations of the Russian tale Vasilisa the Beautiful .

This feature occurs only in a small number of other tales, such as some variations of the Russian tale Vasilisa the Beautiful .

Patterns and ancient origins of these

The bean stalk seems to be a memory of the World Tree connecting Earth with Heaven, an ancient belief that existed in Northern Europe. This may be reminiscent of a Celtic tale, an ancient form of the Axis mundi , the original myth of the cosmic tree, a magical-religious symbolic link between Earth and Heaven, allowing sages to climb to the upper halves to know the secrets of the cosmos and the conditions of human life on earth. It is also reminiscent in the Old Testament of the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11:1-9) and the scale of Jacob's dream (Genesis 28:11-19) ascending to Heaven.

The victory of the "small" over the "great" is reminiscent of the episode of David's victory over the giant Philistine Goliath in the Old Testament ( 1 Samuel 17:1-58). In the 1807 version of The Bat (1807), the "ogre" is beheaded, as was Goliath in the Old Testament story.

"The Goose that Lays the Golden Eggs", illustration for Milo Winter's Aesop fable, taken from book "Isop for Children" . The motif of the "hen that lays the golden eggs" is repeated in the fairy tale Jack and the Magic Bean .

Jack steals a goose that lays golden eggs, which resembles the goose with golden eggs of Aesop's fable (VII e - VI - th century BC), without coming to however this is Aesopian morality: no moral judgment is made on greed in Jack . Gold mining animals can be found in other tales such as the donkey in Peau d'âne or the donkey in Petite-table-sois-mise, Donkey-to-gold and Gourdin-sors-du. - bag , but a fact. The fact that in Jack the goose lays golden eggs does not play a special role in the development of the plot. In his Symbol Dictionary Jean Chevalier and Alain Gerbran note: “In the Celtic continental and insular tradition, the goose is the equivalent of the swan [. ..]. Considered a messenger from the Other World, among the Bretons he is the object of a ban on food, along with a hare and a chicken. "

..]. Considered a messenger from the Other World, among the Bretons he is the object of a ban on food, along with a hare and a chicken. "

Jack also steals the golden harp. In the same Dictionary of Symbols we can read that the harp “connects heaven and earth. The heroes of the Edda want to be burned with a harp on a funeral pyre: this will lead them to that world. This is the role of the psychiatrist, the harp does not fulfill it only after death; during earthly life, it symbolizes the tension between the material instincts, represented by its wooden frame and the ropes of the lynx, and the spiritual aspirations, represented by the vibrations of these ropes. They are harmonious only if they come from a well-regulated tension between all the energies of the being, this measured dynamism that symbolizes the balance of personality and self-control. "

Moral

The story shows a hero who shamelessly hides in a man's house and uses his wife's sympathy to rob him and then kill him. In Tabart's moralized version, the fairy explains to Jack that a giant stole and killed his father, and Jack's actions turn into justified retribution in the process.

In Tabart's moralized version, the fairy explains to Jack that a giant stole and killed his father, and Jack's actions turn into justified retribution in the process.

Meanwhile, Jacobs omits this excuse, relying on the fact that, according to his own recollection of a fairy tale heard in childhood, she was absent from it, and also on the idea that children know well, without this we should tell them in a fairy tale that theft and murder are "evil".

Many modern interpretations have followed Tabart and portrayed the giant as a villain, terrorizing little people and often stealing valuables to make Jack's behavior legal. For example, the film "The Goose Who Loves Golden Eggs" ( Jack and the Beanstalk , 1952), starring Abbott and Costello, blames Jack the giant for failure and poverty, making him guilty of theft, and small people from the lands at the foot of his dwelling, food, and possessions, including a goose that lays golden eggs, which in this version originally belonged to Jack's family. Other versions suggest that the giant stole the chicken and harp from Jack's father.

Other versions suggest that the giant stole the chicken and harp from Jack's father.

However, the moral of the tale is sometimes disputed. It is, for example, the subject of discussion in Richard Brooks' Seed of Violence ( Jungle on Plank , 1955), an adaptation of the novel by Evan Hunter (i.e. Ed McBain).

A mini-series made for television by Brian Henson in 2001, Jack and the Beanstalk ( Jack and the Beanstalk: The True Story ) gives an alternate version of the tale, leaving Tabart's additions aside. Here, Jack's character is significantly clouded, and Henson dislikes the morally dubious actions of the hero in the original tale.

Interpretations

There are different interpretations of this tale.

At first we can read Jack's exploits in the Middle Kingdom as a fairy tale. Indeed, it is at night when Jack, deprived of his supper, is asleep that a giant bean stalk appears, and it is not uncommon to see it as a fairy tale creation, spawned by his hunger and subsequent adventures, in part because of the guilt of failing him. missions. The giantess, the ogre's wife, is a projection of Jack's mother in the dream, which can be interpreted as the fact that during Jack's first visit to the Skyworld, the giantess accepts her regarding her mother's protective behavior. The ogre thus represents the absent father, whose role was to provide both, Jack and his mother, with a livelihood, a role for which Jack is now called upon to replace him. In Skyworld, Jack joins his father-turned-giant and formidable shadow - the ogre - in competition with him, who seeks to eat him, and eventually sets about the task. Causing the ogre's death, he comes to terms with his father's death and realizes that it is his duty to the one who was initially presented as worthless to take over. In this way, he also breaks the bonds that bind and hold his mother captive to his father's memory.

missions. The giantess, the ogre's wife, is a projection of Jack's mother in the dream, which can be interpreted as the fact that during Jack's first visit to the Skyworld, the giantess accepts her regarding her mother's protective behavior. The ogre thus represents the absent father, whose role was to provide both, Jack and his mother, with a livelihood, a role for which Jack is now called upon to replace him. In Skyworld, Jack joins his father-turned-giant and formidable shadow - the ogre - in competition with him, who seeks to eat him, and eventually sets about the task. Causing the ogre's death, he comes to terms with his father's death and realizes that it is his duty to the one who was initially presented as worthless to take over. In this way, he also breaks the bonds that bind and hold his mother captive to his father's memory.

We can also interpret the story from a broader point of view. The giant that Jack kills before becoming the master of his fortune may represent the "big ones in this world" who exploit the "little people" and thereby provoke their rebellion, making Jack the hero of a sort of jacquerie.

Vector illustrations

The tale, reprinted many times, was drawn by famous artists such as George Cruikshank (illustrator of Charles Dickens), Walter Crane or Arthur Rackham.

Modern fixtures

Movie

Jack and beanstalk (1917)

- 1902: Jack and the Beanstalk , a ten-minute short film produced by the Edison Manufacturing Company and directed by George S. Fleming and Edwin S. Porter, with Thomas White (Jack).

- 1912: Jack and the Beanstalk or Jack the Giant Killer , a short film directed by J. Searle Dawley, with Gladys Hewlett (Jack), Harry Eitinge (giant) and Gertrude McCoy.

- Jack and the Beanstalk , a short film with Leland Benham (Jack) and Helen Badgley.

- 1917: Jack and the Beanstalk , directed by Chester M. Franklin and Sidney Franklin, with Francis Carpenter (Jack), Jim J. Traver (giant), Virginia Lee Corbin, Jane Leigh, Katherine Leigh, Violet Radcliffe and Carmen de Ryu.

- 1922: Jack and the Beanstalk , produced and directed by Walt Disney.

- 1924: Jack and the Beanstalk , an animated short film directed by Herbert M. Dawley.

- 1924: Jack and the Beanstalk , short film directed by Alfred J. Goulding, with Baby Peggy and Blanche Payson.

- 1924: L'Ogre ( The Giant Killer ), short film mixing live action footage and animation, directed by Walter Lantz, starring the character Dinky Doodle (a character created in 1916 and considered one of the first cartoon characters) .

- 1931: Jack and the Beanstalk , an animated short film directed by Dave Fleischer, starring Betty Boop.

- 1933: Mickey in Giantland ( Giantland ), an animated short produced by Walt Disney and directed by Barton Gillette, starring, as the name suggests, the character Mickey.

- 1933: Jack and the Beanstalk , an animated short film directed by Ub Iwerks and written by Ben Hardaway, collaboration with Sheamus Culhane, music by Carl W.

Stalling (uncredited).

Stalling (uncredited). - 1943: Jack the Wabbit and the Beanstalk , an animated short film directed by Friz Freleng, music by Carl W. Stalling and starring the character Bugs Bunny.

- 1947: Mickey and the Beanstalk , an episode from Disney's Spring Scoundrel , directed by Hamilton Luske and Bill Roberts, again starring the character Mickey.

- 1952: La Poule aux Eggs d'Or ( Jack and the Beanstalk ) produced in black and white for the modern part and in color for Jean Yarbrough's fantasy tale period with Lou Costello (Jack), Buddy Baer (giant), and Costello's lifelong friend, Bud Abbott.

- 1955: Jack and the Beanstalk or Jack the Giant Killer , a British short film (China Shadow technique) directed by Lotte Reiniger with music by Freddie Phillips.

- 1955: Seed of Violence by Richard Brooks, who integrates the cartoon Jack and the Magic Bean into his film to show Richard Dadier's character's heart for tolerance towards his students.

- 1967: Shônen Jakku to Mahô-tsukai (in the United States: Jack and the Witch ) is a Japanese animated film directed by Taiji Yabushita.

- 1970: Jack and the Beanstalk , directed by Barry Mahon, with Mitch Poulos (Jack) and Renato Boraquerro (giant).

- 1974: Jack and the Beanstalk is a Japanese-American animated film directed by Gisaburo Sugi.

- 2013: Jack the Giant Slayer ( Jack the Giant Slayer ), a feature film directed by Bryan Singer, with Nicholas Hoult as Jack.

- 2015: Into the Woods musical film featuring characters from fairy tales with Daniel Huttlestone as Jack.

- Tom and Jerry Jack and the Magic Bean

TV and video

- 1967: Jack and the Beanstalk ( Jack and the Beanstalk (1967) ), produced by Gene Kelly, William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, directed by Gene Kelly, Music by Lenny Hayton, with Gene Kelly, Bobby Riha (Jack) and Ted Cassidy (giant).

The film, which is about fifty minutes long, combines real footage and animation, emphasizing music and dance.

The film, which is about fifty minutes long, combines real footage and animation, emphasizing music and dance. - 1973: The Goodies and Beanstalk , episode of the British TV series featuring the Goodies, a trio of actors consisting of Tim Brooke-Taylor, Graham Garden and Bill Oddy.

- 1974: Jack and the Beanstalk with Peter Jeffery.

- 1993: Jack and the Magic Bean (video), animated short film directed by Koji Morimoto, "Anime Art Video" compilation.

- 1998: Jack and the Beanstalk , a British television film directed by John Henderson and starring Neil Morrissey (Jack), Griff Rhys Jones and Peter Serafinowicz.

- 2001: Jack and the Beanstalk ( Jack and the Beanstalk: The True Story of ), directed by Brian Henson, with Matthew Modine (Jack), Vanessa Redgrave, Mia Sarah, Daryl Hannah, Jon Voight and JJ Feild (Jack's child) .

- 2010: Jack and the Beanstalk is an American television film directed by Gary J.

Tunnicliff and starring Colin Ford, Chloe Moretz and Christopher Lloyd.

Tunnicliff and starring Colin Ford, Chloe Moretz and Christopher Lloyd. - 2010: Simsala Grimm , German cartoon season 2 episode 1: Jack and the beanstalk (Hans und die Bohnenranke)

- 2013: TV series Once Upon a Time offers its own version of the tale. "Jack" here is a woman, and her real name is Jacqueline. In the universe of the series, Jacqueline allies with Prince James (charming's twin) and manipulates the giant into pretending to be his friends, rather than steal his wealth and magic beans;