Peter and the snowy day

'A Poem For Peter' Recalls One Unforgettable 'Snowy Day' : NPR

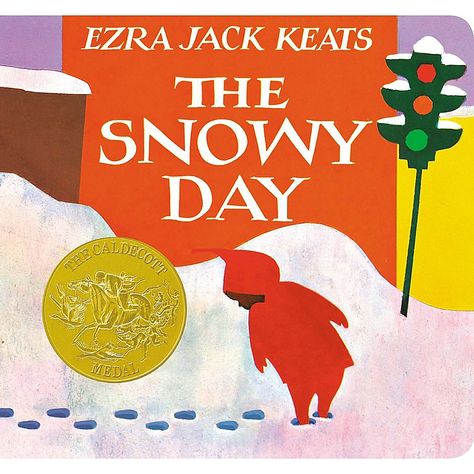

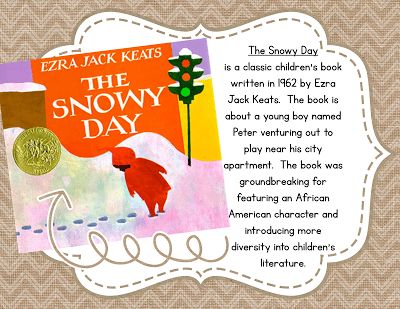

'A Poem For Peter' Recalls One Unforgettable 'Snowy Day' In 1962, Peter — an African-American boy exploring his neighborhood after a snowstorm — broke the color barrier in mainstream children's publishing. A new book pays tribute to author Ezra Jack Keats.

Author Interviews

Heard on Morning Edition

'A Poem For Peter' Recalls One Unforgettable 'Snowy Day'

In A Poem for Peter, Andrea Davis Pinkney introduces young readers to Ezra Jack Keats, the author and illustrator behind The Snowy Day. The story begins with Keats' parents fleeing Warsaw, seeking a better life in the United States. It is illustrated by Lou Fancher and Steve Johnson. Lou Fancher and Steve Johnson/Penguin Random House hide caption

toggle caption

Lou Fancher and Steve Johnson/Penguin Random House

Author Andrea Davis Pinkney used to sleep with a copy of The Snowy Day. "I loved that book — it was like a pillow to me," she says.

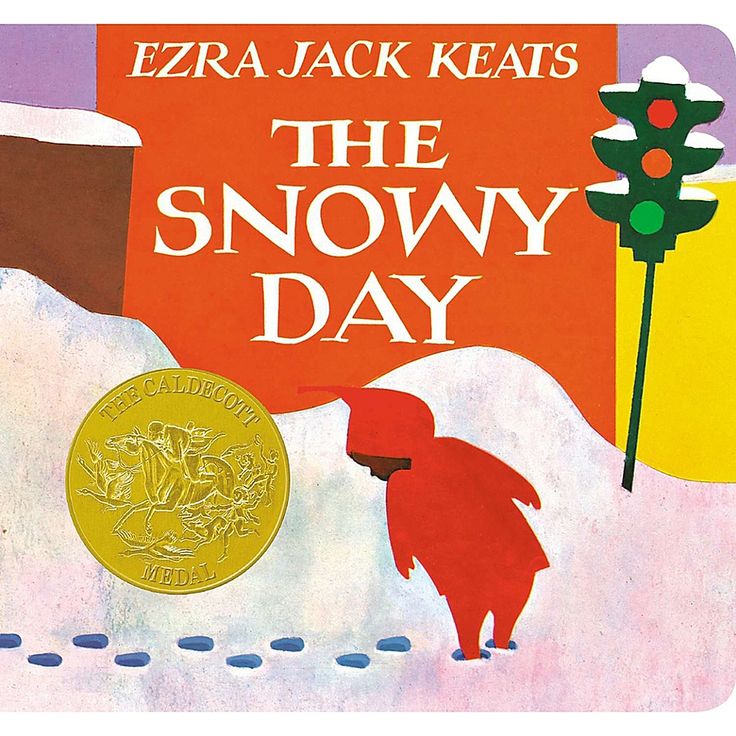

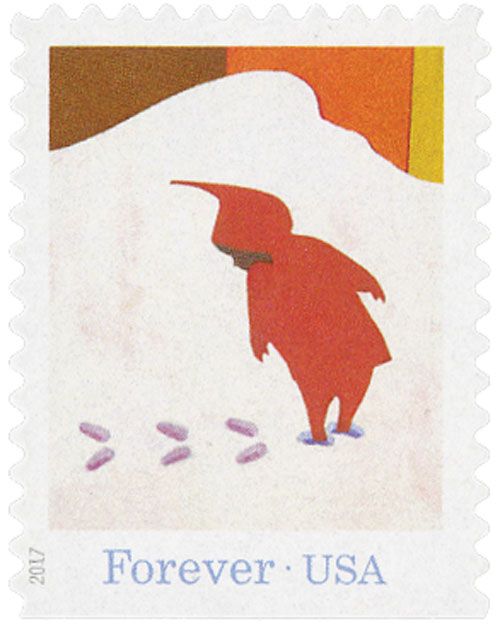

More than 50 years ago, Peter — an African-American boy exploring his neighborhood after a snowstorm — broke the color barrier in mainstream children's publishing. The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats would go on to win a Caldecott Medal. Now, Pinkney pays homage to Keats in a new book called A Poem for Peter, and there is an animated, Snowy Day special streaming on Amazon.

When Pinkney was asked to write a book about Keats, she says she jumped at the chance "like a kid on a sled." The Snowy Day was her favorite book as a child; she says it brought her comfort to see her own life reflected on the page.

"Up to that point, there were many picture books but they were in rural settings," she says. "And here was this book that made my life, my experience, valid. City streets, sidewalks, stoops — everything that I held so dear."

As she worked on the biography, Pinkney learned that Keats was also a city kid, the child of immigrants who fled anti-Semitism in Poland. As a child, Keats wanted to become an artist, but his father died when he was a teen, World War II broke out, and his dreams were put on hold. After serving in the Army, Keats returned to face discrimination at home.

As a child, Keats wanted to become an artist, but his father died when he was a teen, World War II broke out, and his dreams were put on hold. After serving in the Army, Keats returned to face discrimination at home.

"He could not find a job," Pinkney says. "There were literally signs in windows that said: 'Jews need not apply.' Ezra was born with the name Jacob (Jack) Ezra Katz. When he saw those signs, he changed his name to Ezra Jack Keats."

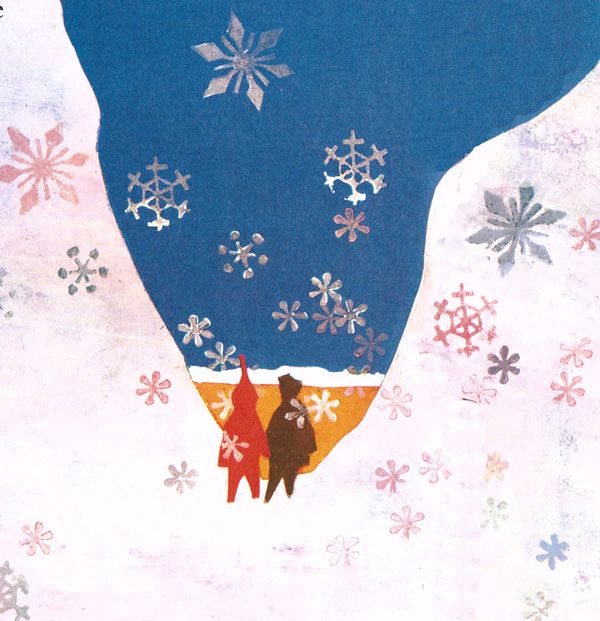

With each tube of colored oil, / Ezra let his imagination grow. / And he drew, oh, how he drew. Lou Fancher and Steve Johnson/Penguin Random House hide caption

toggle caption

Lou Fancher and Steve Johnson/Penguin Random House

Eventually, Keats landed a job as an illustrator. At some point he saw a series of photos of a young, black boy in Life magazine. He held on to those pictures for 20 years.

At some point he saw a series of photos of a young, black boy in Life magazine. He held on to those pictures for 20 years.

"And then he gets an invitation to create his own children's book," Pinkney explains. "And he said: This is the boy I am going to use as the star."

And that's how Peter was born. With its beautiful illustrations and sweet story, The Snowy Day was an instant hit. But there was also a backlash because Keats was white.

"Ezra was criticized for presuming to be able to write about a black child," explains Deborah Pope, executive director of The Ezra Jack Keats Foundation. But Keats had a simple response. He said he put black characters into his books "because they're there," Pope says. Keats felt they'd "always been there, but we've never seen them — we need to see them."

That need still exists, Pinkney says, "We need more Peters. We need more stories that are universal in nature ... that appeal to all children just because of their beauty, and whimsy, and fun and discovery. "

"

In her new book, Pinkney introduces Peter — and the man who created him — to a new generation of young readers:

Like a snowflake you fell,

right into our hearts.

You arrived.

A little Snowy Day surprise!

Like a crystal flake from the clouds,

you fluttered down

with your own one-of-a-kind

cutie-beauty.

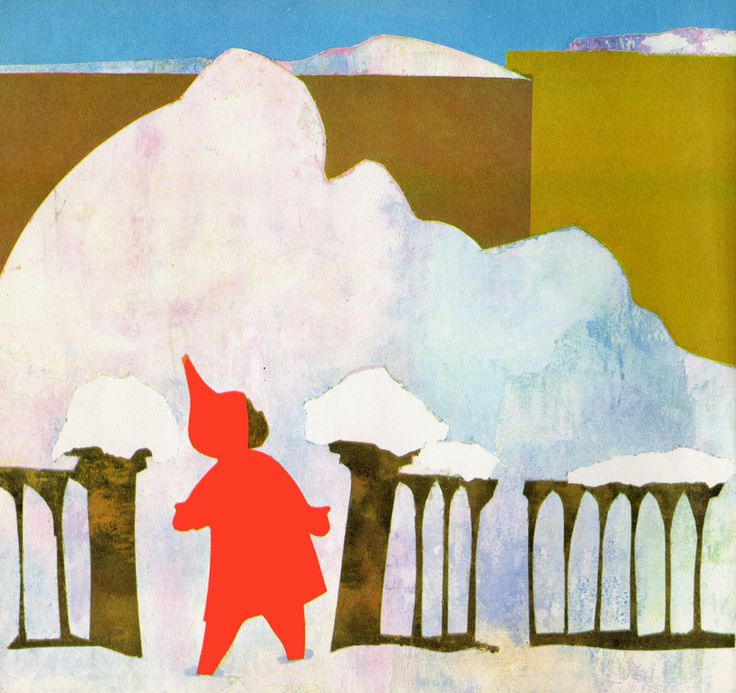

Peter and Ezra, / you made a great team. / Together you brought a snowstorm / of your dreams. Lou Fancher and Steve Johnson/Penguin Random House hide caption

toggle caption

Lou Fancher and Steve Johnson/Penguin Random House

Peter and Ezra, / you made a great team. / Together you brought a snowstorm / of your dreams.

Lou Fancher and Steve Johnson/Penguin Random House

Sponsor Message

Become an NPR sponsor

Why Did I Fail to Notice Race in "The Snowy Day?"

books

In reading colorblind to my children, I erased Peter’s Blackness from the story

Sep 14, 2021

Brian Goedde

Share article

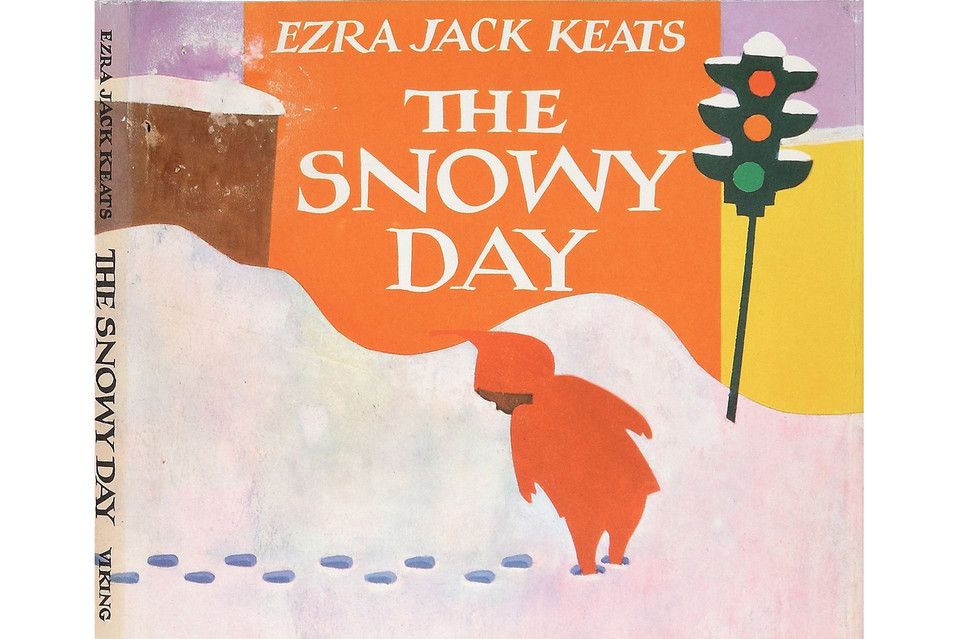

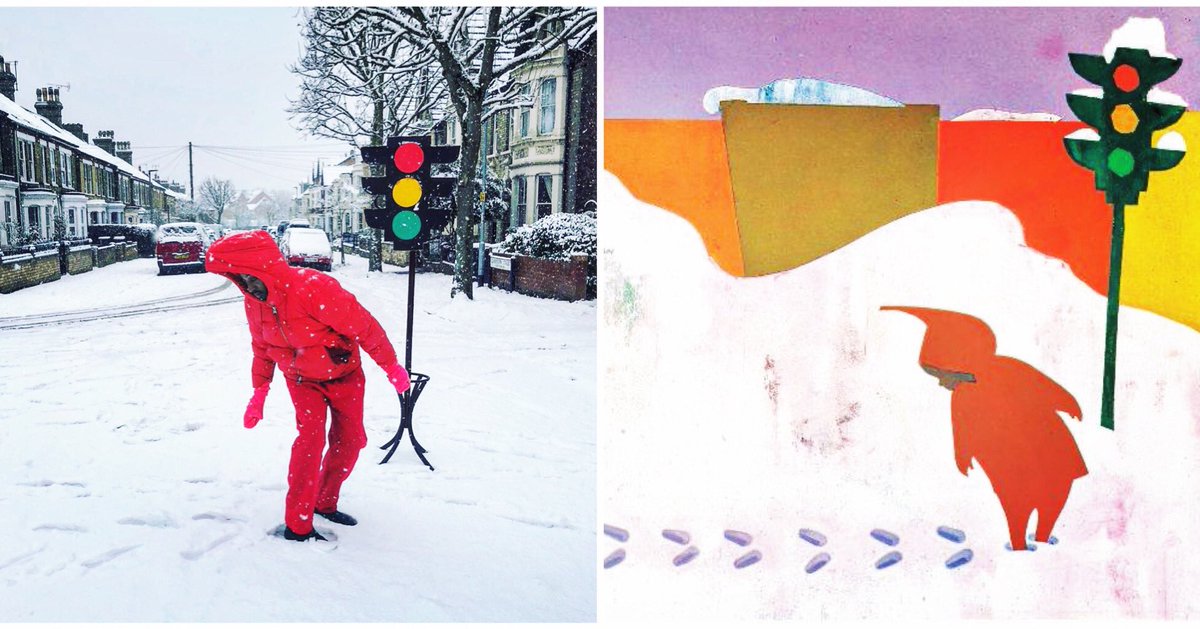

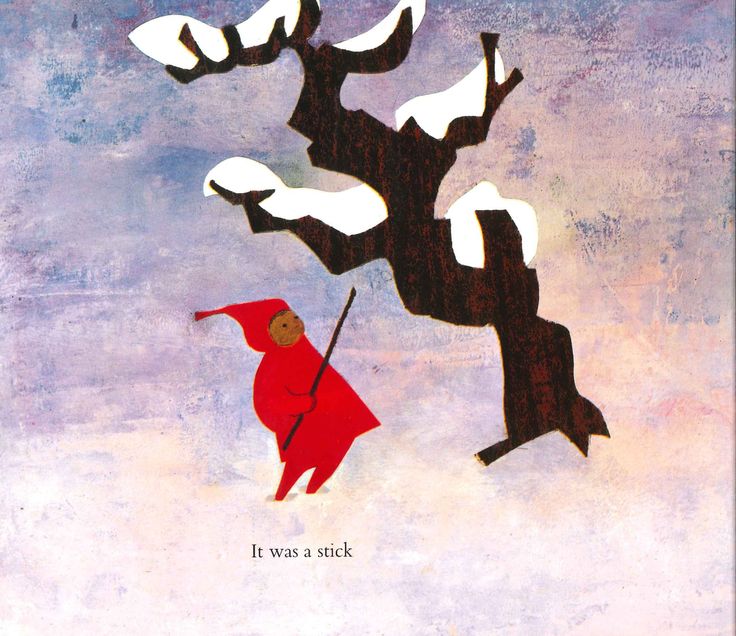

There is an error in The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats that I didn’t see until some point reading it to our second child. On the fifth and sixth pages, Keats writes that Peter “walked with his toes pointing out, like this,” and then, “He walked with his toes pointing in, like that.” The footprints below the text are angled accordingly. In his bright red snowsuit, Peter stands at the far right, looking back over his shoulder, one of several quiet, thoughtful moments in this beautiful book.

In his bright red snowsuit, Peter stands at the far right, looking back over his shoulder, one of several quiet, thoughtful moments in this beautiful book.

But how could I have read over this so many times: The footprints in the picture are side-by-side, two-by-two. Peter didn’t walk. He hopped. (Curiously, the cover image of the book is also Peter looking back at his footprints, but those are alternating and facing forward, evidence of ambulation.)

Why care? It wasn’t noticeable when I read right over it—and over and over it—to my oldest child. But Peter is a child who notices and reflects, which is much of what I love about this book, so I want to respond in kind, especially considering how loved this book has been—by us as a family, and as part of a wider readership. What made The Snowy Day a groundbreaking “first” when it won the Caldecott in 1963, and what makes it noteworthy on our bookshelves as a white family almost sixty years later, is that Peter is Black.

I had noticed Peter’s race, and I imagine my kids did too, but we never talked about it. What I had been reading right over, and repeatedly, was what Peter’s race meant. Can it mean nothing? Clearly not—it is noteworthy and groundbreaking. Yet I was reading colorblind. Why? Was this what the author intended?

The footprints in the picture are side-by-side, two-by-two. Peter didn’t walk. He hopped.

Keats was white. Born in Brooklyn in 1916 as Jacob Ezra Katz, he was the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland. As a young working artist, Keats was a muralist for the Works Progress Administration, a background illustrator for Captain Marvel comics, and, in WWII, a camouflage designer. In 1947, in response to anti-Semitism, he changed his name to Ezra Jack Keats and became an illustrator for newspapers, magazines, and eventually children’s books. “Then began an experience that turned my life around, working on a book with a black kid as hero,” he said, as recounted on the Ezra Jack Keats Foundation website. “None of the manuscripts I’d been illustrating featured any black kids—except for token blacks in the background. My book would have him there simply because he should have been there all along.”

“None of the manuscripts I’d been illustrating featured any black kids—except for token blacks in the background. My book would have him there simply because he should have been there all along.”

Diversifying children’s literature was a cause for Keats. His first book, which he co-authored with Pat Cherr in 1960, My Dog Is Lost!, stars Juanito as its main character, a Puerto Rican immigrant who speaks only Spanish. Of the twenty-two books Keats went on to write and illustrate, seven starred Peter and his family. Other recurring characters in Keats’ oeuvre are Archie and Amy, who are Black, and Roberto, who is Latinx.

‘Then began an experience that turned my life around, working on a book with a black kid as hero,’ Keats said.

The diversity was much needed. In her landmark study “The All-White World of Children’s Books,” published in The Saturday Review three years after The Snowy Day was published, educator and scholar Nancy Larrick found that only 6. 7% of children’s books published between 1962 and 1965 included a Black character, even in the background.

7% of children’s books published between 1962 and 1965 included a Black character, even in the background.

In the sixty years since, progress has been made, but, alarmingly little, and only very recently. According to a study by Professor Sarah Park Dahlen, based on data from The Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Education, 23% of children’s books published in 2018 “depicted characters from diverse backgrounds.” It was 14.2% in 2014, so it is encouraging to see the number go up, but for at least 20 years before this, according to Professor Philip Nel in his 2017 book Was the Cat in the Hat Black? The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature and the Need for Diverse Books, it hovered around 10%. (Nel answers his question: Yes, the Cat in the Hat was Black, both in the visual language and themes of minstrelsy.) What should the number be? If it were to reflect the current U.S. population, it would be about 40%.

Scrutinizing an industry is one thing, but what do I offer my own kids? It’s important to my wife and me to talk to our kids about identity, including race. Books prompt and support these discussions. For example, The Colors of Us by Karen Katz celebrates the multiplicity and beauty of skin colors, centering on a child discovering what color to use in a self-portrait. (She decides on cinnamon; my youngest most recently settled on “peach.”) Other family favorites honor culture, like Bi-bim Bop! by Linda Sue Park, which includes a recipe for the Korean dish, and Feast For Ten by Catheryn Falwell, a counting book that features a Black family shopping and cooking.

Books prompt and support these discussions. For example, The Colors of Us by Karen Katz celebrates the multiplicity and beauty of skin colors, centering on a child discovering what color to use in a self-portrait. (She decides on cinnamon; my youngest most recently settled on “peach.”) Other family favorites honor culture, like Bi-bim Bop! by Linda Sue Park, which includes a recipe for the Korean dish, and Feast For Ten by Catheryn Falwell, a counting book that features a Black family shopping and cooking.

It’s important to my wife and me to talk to our kids about identity, including race.

In raising awareness of others, these books, visually and textually, also raise awareness of ourselves. Another recent favorite has been Bedtime Bonnet by Nancy Redd, who writes in her author bio that she was “inspired by the lack of resources” for her daughter about Black hair. The book begins, “In my family, when the sun goes down, our hair goes up!” In our family, it stays down, so, in addition to learning about wave caps and durags—it’s a resource for us, too—we talk about the care that different hair types require. It feels like part of a good foundation for conversations in the years ahead about all that hair represents, and has represented, in issues of identity.

It feels like part of a good foundation for conversations in the years ahead about all that hair represents, and has represented, in issues of identity.

But back to my question in light of the statistics: what do I offer my own kids—in numbers? Just like not noticing Peter’s footprints, a true audit of my own bookshelf was something I had overlooked.

My study was not terribly scientific. I took my tally by walking my fingers across book spines and pulling them half-way out one afternoon while I was watching my three-year old, and I know there’s at least one other box in the attic filled with books that I didn’t dig out. I mention these limitations to my research because this is how inequality in the 21st century can persist. For as much as I imagine myself to be forward-thinking in matters of parenting and social justice, while in the throes of everyday life, it is all too easy to slide into historical patterns of underrepresentation, if not complicit prejudice. Of the 426 picture books I counted, which we have accumulated for three kids over 13 years, 53 have a main character that is human and not white. I was fearing it would be something like 5, so I am relieved, but in terms of our proportions, it comes out to 12%, a very 20th-century library.

Of the 426 picture books I counted, which we have accumulated for three kids over 13 years, 53 have a main character that is human and not white. I was fearing it would be something like 5, so I am relieved, but in terms of our proportions, it comes out to 12%, a very 20th-century library.

The Snowy Day was a member of the 53 (I passed over our copy of The Cat in the Hat, blushing), but my audit raised further questions about how much, or how well, these books advance the causes of inclusion, equity, anti-racism—causes that motivate my attention. For example, I counted Taro Gomi’s lovely books, originally published in Japanese, but are people and culture of East Asia “represented,” in the sense of promoting diversity? Yes, I decided, compared to Emily’s Balloon by Komako Sakai, also translated from Japanese, in which Emily looks white (so I didn’t count it as part of the 53).

As for Keats’ books, other than Juanito’s Spanish, the stories never call direct attention to ethnicity or race. His images do, but also not really: they show skin color, but not anything that would suggest culture or identity. If any identity is explicit in Keats’ stories of apartment-dwelling and alleyway adventuring, it is working-class urban culture. It is also noteworthy that none of his characters are identified as Jewish. Keats does take up religion in his 1966 book God is in the Mountain, but to make something of a universalist statement: it is an illustrated collection of passages from religious texts spanning the globe.

His images do, but also not really: they show skin color, but not anything that would suggest culture or identity. If any identity is explicit in Keats’ stories of apartment-dwelling and alleyway adventuring, it is working-class urban culture. It is also noteworthy that none of his characters are identified as Jewish. Keats does take up religion in his 1966 book God is in the Mountain, but to make something of a universalist statement: it is an illustrated collection of passages from religious texts spanning the globe.

If Keats sought to diversify picture books, it was to depict the ideal of the melting pot, and when The Snowy Day was published, reviewers were correspondingly colorblind. According to Kathleen T. Horning’s 2016 article for The Horn Book magazine, “The Enduring Footprints of Peter, Ezra Jack Keats, and The Snowy Day,” the book was widely and favorably reviewed, but only three publications acknowledged Peter’s race. The Saturday Review commented on race to dismiss it: “that the boy’s skin is brown is never mentioned in the text, so it is for all children. ” This aspect of Keats’ work also drew criticism. While the civil-rights advocacy group the Council on Interracial Books for Children put Keats’ books on its recommended books list, it also criticized Keats for presenting children of color who might as well be white.

” This aspect of Keats’ work also drew criticism. While the civil-rights advocacy group the Council on Interracial Books for Children put Keats’ books on its recommended books list, it also criticized Keats for presenting children of color who might as well be white.

The tension here is echoed in my own reading: is it a beloved family favorite because it never calls attention to race—Peter’s or ours? As Keats said of Peter, “he simply should have been there all along” in children’s literature, and I agree—we all agree—but only if he “might as well be” white?

Is it a beloved family favorite because it never calls attention to race—Peter’s or ours?

Keats himself was outspoken about his cause of diversifying children’s literature—except for when he wasn’t. In his essay “The Right to Be Real,” published in The Saturday Review after The Snowy Day won the Caldecott, Keats writes that “[w]e are now entering a new era of children’s books,” one that will “relegate to the past the kind of books, both trade and text, in which an entire people and a great heritage have been deliberately ignored. ” When he won the Caldecott for The Snowy Day, however, in his acceptance speech given a month before the 1963 March on Washington, he opts to deliberately ignore it. He suggests its significance in his concluding sentence—“I can honestly say that Peter came into being because we wanted him”—but he doesn’t once mention Peter’s race.

” When he won the Caldecott for The Snowy Day, however, in his acceptance speech given a month before the 1963 March on Washington, he opts to deliberately ignore it. He suggests its significance in his concluding sentence—“I can honestly say that Peter came into being because we wanted him”—but he doesn’t once mention Peter’s race.

This mixed messaging continues through today. Deborah Pope, Executive Director of The Ezra Jack Keats Foundation, which, among other initiatives to honor the artist, gives an annual award to promote diversity in children’s literature, told National Public Radio on the 50th anniversary of The Snowy Day that Keats didn’t mention Peter’s race in the book because it “wasn’t important. It wasn’t the point. The point is that this is a beautiful book about a child’s encounter with snow, and the wonder of it. […] Was he trying to make a ‘cause’ book, was he trying to make a point? No.”

Again, before my attention gets fixed on what other people say and don’t say, do and don’t publish, I have to acknowledge that, in my countless readings of The Snowy Day as a white father to my white kids (Peter appears against a blanketing whiteness indeed), I had never talked about Peter’s race either. What would there be to talk about? It is, as Pope suggests, crafted as a universal story, which makes it doubly remarkable on our bookshelf: not only does this book star a Black child, this Black child represents universal childhood.

What would there be to talk about? It is, as Pope suggests, crafted as a universal story, which makes it doubly remarkable on our bookshelf: not only does this book star a Black child, this Black child represents universal childhood.

…I had never talked about Peter’s race either. What would there be to talk about?

But if race is not acknowledged, if this “remarkableness” is not remarked upon, how visible, or present, is Peter? How present, or realized, is the childhood he represents? How present are we, when we read it?

In all of our appreciation of The Snowy Day, the blizzarding wonder for me is in how race appears in the book, then disappears when it is reviewed, awarded, honored 50 years later, and when I continue to read it. It makes me further wonder whether, in our collective white mind, the feat was—and is—the appearance of race or its disappearance. It recalls Toni Morrison’s 1988 essay “Unspeakable Things Unspoken: The Afro-American Presence in American Literature”:

I can’t help thinking that the question should never have been “Why am I, an Afro-American, absent from it?” It is not a particularly interesting query anyway. The spectacularly interesting question is “What intellectual feats had to be performed by the author or his critic to erase me from a society seething with my presence, and what effect has that performance had on the work?”

The spectacularly interesting question is “What intellectual feats had to be performed by the author or his critic to erase me from a society seething with my presence, and what effect has that performance had on the work?”

My performance of reading of The Snowy Day, which is also a performance of parenting, is what gives importance to Peter hopping.

I tried it myself, one snowy day last year. Crunch, crunch, crunch, my feet sank into the snow. While playing with my toddler after a new snowfall in the mostly white, suburban alleyway behind my duplex, I took twelve walking steps and looked back, then twelve hops and looked back. They made for very different moments of reflection. Walking allowed me to carefully place my footsteps; a dozen hops took the wind out of me.

Here is where my mistake of not noticing is costly: I had always seen this moment as one of quiet introspection. I thought I knew what Peter was thinking and feeling, how he was looking and breathing. I thought I knew Peter, in other words, and that The Snowy Day knew Peter. But I don’t think we did.

I thought I knew Peter, in other words, and that The Snowy Day knew Peter. But I don’t think we did.

I thought I knew Peter, in other words, and that The Snowy Day knew Peter. But I don’t think we did.

What else am I reading right over, and repeatedly?

I have to stop modeling colorblindness, in the name of the universal, when I read this book—and really, any book. The avoidance of race amounts to its erasure, even as I honor its presence on my bookshelf. It models for my kids that, as white people, we talk about race when it is somehow advantageous, or called to our attention, as in (most of) our 53 books that feature a main character of color, but otherwise, we don’t have to worry about it, as in our other 373.

And what of these other 373? Feast for Ten is a “raced” counting book; what about Counting Birds? The books about science? The narratives that star animals by Richard Scarry, Sandra Boynton, Mo Willems—they don’t “depict race,” but in what ways, or to what degree, do they express whiteness, the absence of color, a defaulted position of power? And in what ways do I reinforce, or recreate, our own defaulted position of power as a white family if I avoid thinking or talking about race when I read any of the 426 books my kids and I cuddle up and share?

Perhaps a timeless virtue of The Snowy Day is that it offers a choice. I can “read colorblind,” a choice I had been making without noticing, or I can have a conversation about race with my kids, a conversation which, like Peter, also “simply should have been there all along.” I want to make the latter choice now; what I have been struggling with, simply, is how to start.

I can “read colorblind,” a choice I had been making without noticing, or I can have a conversation about race with my kids, a conversation which, like Peter, also “simply should have been there all along.” I want to make the latter choice now; what I have been struggling with, simply, is how to start.

I have faith in literature: a book this good teaches me how to read it, or in this case, to read it better. If there is not a clear and obvious way to address race in The Snowy Day, it’s my responsibility to find one.

Peter himself is a model for learning. After he looks back on his footprints—made by hopping—he then learns about the snow and what to do in it, dragging his feet “s-l-o-w-l-y to make tracks,” and making snow angels and a “smiling snowman.” He also learns about himself in relation to others: “He thought it would be fun to join the big boys in their snowball fight, but he knew he wasn’t old enough—not yet.” Peter sits in the foreground, a snowball splattered on his torso. Apparently, he learned this the hard way. Peter also conducts two experiments. He hits a snow-covered tree branch with a stick, learning that snow then falls on his head, and upon returning home, puts a snowball in his pocket “for tomorrow.”

Apparently, he learned this the hard way. Peter also conducts two experiments. He hits a snow-covered tree branch with a stick, learning that snow then falls on his head, and upon returning home, puts a snowball in his pocket “for tomorrow.”

“It will melt!” my toddler exclaims when we get to this page. She knows this not only because we’ve read the story countless times, but because last winter she replicated his experiment.

She knows this not only because we’ve read the story countless times, but because last winter she replicated his experiment.

At the end the book, another snowy day begins, but this time there is a big difference. Instead of going out in the snow alone, “After breakfast he called to his friend from across the hall, and they went out together in the deep, deep snow.” The last page shows the two of them in the distance, walking away.

What else have I been reading over?

“Do you know what this means,” I asked my daughter, under the covers for bedtime stories, “that his friend was ‘across the hall’?” For as much as the book is “universal,” here is a detail from Peter’s world, and Keats’, that places them—and us—in the world together.

My daughter kept her thumb in her mouth and shook her head. I briefly explained what an apartment building was. To my memory, she had only been in two. She didn’t remember either.

What else?

Another time, after reading the book at breakfast, I said to my daughter, “So, Peter has brown skin, like Doc McStuffins,” a current favorite cartoon. “What about Peter’s friend?”

She looked. “His coat is brown.”

“So, yes? Or we don’t know?”

We both stayed quiet, looking.

“Do we know it’s a boy? It only says ‘his friend.’”

“I think he’s a girl.” She smiled. “I think he’s a boy.”

Why did she switch back from “girl” to “boy”? Was it the force of the gendered pronoun? Was it her flexible toddler mind? Either way, there it is, on the very last page, the point of entry I had been reading over, and repeatedly. It’s Peter’s friend that can engage me in conversations about identity—beginning with our assumptions, and the question of whether we see ourselves alongside Peter or not.

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven't read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

One snowy day in St. Petersburg (39 photos - St. Petersburg, Russia)

Russia Saint Petersburg city > One snowy day in St. Petersburg (39 Photos)

Author: Van

Saturday, January 26, was snowy in St. Petersburg. Arriving in the afternoon and checking into the hotel, I decided to warm up a bit and take a walk. The walk, despite the weather, lasted for several hours. The city was preparing the next day to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the lifting of the blockade of Leningrad. I did not want to shoot anything, but still I could not resist and took a few photos "for memory".

Anichkov bridge. SPb

Klodt - "Conquest of the horse by man."

Vodnichy leans on one knee,

gripping the bridle with both hands,

stops the horse.

Anichkov bridge. SPb

Klodt - "Conquest of the horse by man."

The animal is obedient to man,

on the hooves of a horseshoe, instead of a saddle, a skin.

Fontanka from Anichkov bridge. SPb

in winter, people have the opportunity to significantly shorten their path ...

Nevsky prospect 41. St. Petersburg

St. Petersburg SOSULI and the fight against them (with varying success)

"Every year Petersburgers die and end up in hospitals because of falling icicles."

from fresh:

SAINT PETERSBURG, February 1, 2019, 12:08, FederalPress. Woman got a concussion

I got the impression that all the forces of St. Petersburg communal services are thrown onto the city roofs, I have not seen such poorly cleaned streets for a long time. Ice build-ups on the sidewalks (even on the Nevsky Prospekt) pass by pedestrians with Nordic calm. ..

..

And children, they are children in Africa too. They are attracted by the dolls moving in the window.

Showcase Eliseevsky. St. Petersburg

Nevsky prospect (28) St. Petersburg

despite the winter, there are people who prefer to move around the city on bicycles.

more often they are deliveries of orders, but there were also several cyclists in thermal suits.

On the eve of the 75th anniversary of the complete liberation of Leningrad from the fascist blockade, Smolny installed functioning copies of blockade loudspeakers in the Central District.

"In the first months of the blockade, 1,500 loudspeakers were installed on the streets of the city. The loudspeakers were reinforced in such a way that the passer-by was continuously in the zone of their sound: one speaker “escorted” the pedestrian, the other immediately “greeted” him. The metronome sounded between transmissions and alerts. According to him, the inhabitants learned the situation in the city. If the radio pulse is normal - 60 beats per minute: everything is calm in the city, if it is quick, bombing or shelling is approaching.0013 / from here http://piter.my/event/634343/

According to him, the inhabitants learned the situation in the city. If the radio pulse is normal - 60 beats per minute: everything is calm in the city, if it is quick, bombing or shelling is approaching.0013 / from here http://piter.my/event/634343/

Blockade loudspeakers. Nevsky prospect 54. St. Petersburg

Kazan Cathedral. SPb

the birds of God are flying...

but "low, low," as Comrade Ensign said about crocodiles.

Mikhail Illarionovich in the snow. St. Petersburg

Monument to M.B. Barclay de Tolly. St. Petersburg

Wash from the Green Bridge. SPb

just a river and just a St. Petersburg bridge

Museum of Illusions. Bolshaya Morskaya street 5. St. Petersburg

"Sail on the Titanic, find yourself among giant toys or escape from zombies..." - no one is in sight, despite the Saturday.

Arch of the General Staff Building and the Church of the Savior Not Made by Hands in the Winter Palace. SPb

SPb

"Church of the Savior Not Made by Hands in the Winter Palace on December 9, 2014, after many years, is open to visitors. This event was timed to coincide with the 250th anniversary of the State Hermitage. Restoration work has been going on since 2008. "

/ from here http://mitropolia.spb.ru/news/culture/?id=62894

Palace Square. SPb

All the "fuss" with the preparations for the Seventy-fifth anniversary is behind me.

Angel of the Alexander Column. St. Petersburg

Inner courtyard of the Winter Palace. SPb

Snowdrifts (small)

Inner courtyard of the Winter Palace. SPb

The queue to the museum was short. Twenty minutes of waiting with the munus of eight amused himself by looking at the statues on the roof.

Inner courtyard of the Winter Palace. St. Petersburg

Petropavlovka from the window of the Hermitage. SPb

"Evening is blue, very blue,

Dropped down on me.

Bright colors, clear lines

The world was covered with a veil. "

/ Pavel Bashlykov (tsy)

Vasilievsky from the window of the Hermitage. St. Petersburg

Inner courtyard of the Winter Palace. SPb

(January snowdrifts)

Isakiy from Palace Square. SPb

(during snowfall)

Palace Square. St. Petersburg

Wash from the Green Bridge. SPb

"just a river" when it got dark

Church of Saints Peter and Paul. Nevsky 22-24. St. Petersburg

Kazan Cathedral. St. Petersburg

Monument to Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin on Arts Square. St. Petersburg

Malaya Sadovaya street. St. Petersburg

Italian street 12. St. Petersburg

Project "Street of Life"

From January 25 to 27, the Street of Life project will be launched on Malaya Sadovaya Street, Manezhnaya Square and Italianskaya Street, which will enable residents and guests of St. Petersburg to touch the "realities of the blockade".

Petersburg to touch the "realities of the blockade".

Italian street 25. St. Petersburg

" Manezhnaya Square and Italianskaya Street will become an open-air Museum, which will be used for guided tours. "

/ from here https://piterzavtra.ru/blokada-spb/

... I got the impression that the streets were not cleaned to give the City a "blockade authenticity" .....

Italian street 25. St. Petersburg

"War" "Blockade" "Victims" - only words

no reason to refuse to take a selfie for many of our people

Manezhnaya Square. SPb

... the square is not crowded

Manezhnaya Square. SPb

TEREMOK under camouflage net

queue for pancakes

(nothing stimulates appetite like a walk in the fresh air)

Manezhnaya Square. SPb

" For the team of the Leningrad Theater of Musical Comedy, the blockade became not only a severe test, but also an unprecedented milestone in their creative biography. The Leningrad musical comedy, the only one of all the city theaters, was left by special order in the besieged city in order to maintain the spirit of Leningraders with its light, cheerful art.

The Leningrad musical comedy, the only one of all the city theaters, was left by special order in the besieged city in order to maintain the spirit of Leningraders with its light, cheerful art.

Every year, veterans and front-line soldiers gather on memorable days in the theater hall at 13 Italianskaya Street, which, alas, are less and less every year, home front workers and children of the war, as well as their children and grandchildren, who know about the horrors of wartime first hand.

Entrance: free

Address: Italian street, 13 "

/ from here https://piterzavtra.ru/blokada-spb/

"Siege hole" (Days of blockade) - a memorial sign in St. Petersburg on the descent of the Fontanka River embankment near house 21, at the place where during the years of the blockade there was an ice hole, to which the inhabitants of the besieged city went for water.

The inscription is carved on the stone:

« Here

from icy

ice hole

took water

residents

besieged

Leningrad »

The memorial sign was opened on January 21, 2001

Fontanka. SPb

SPb

Anichkov bridge from the ice of the river

Fontanka. SPb

Belinsky bridge from the ice of the river

Fontanka Ice

water on top of ice near the pier near the National Library of Russia

(embankment of the Fontanka River, 36)

Fontanka Ice

someone trampled the word "SPARTAK" in the snow

why? why here? ... and now? wasn't it lazy?

I don't understand these people!

Publication date: 02/03/19

1.

karlione 02/04/19 10:02:49

this gallery is somewhat more meaningful than many from the author, there are really good shots inscribed in a certain concept (even two can be traced). however, framing still raises questions, and there is too much.

2.

Van 02/04/19 12:05:55

to karlione

I have asked you many times already.

I'll try to convey the message differently:

- dear karlione, better go teach your wife how to cook cabbage soup

;-)

3.

elena.shustrova 04.02.19 20:16:25

Van, you are just a hero - to walk through our uncleaned streets all day, and take so many photos! Indeed, this year something is going wrong under our feet. And in the photo the snow looks very photogenic))

4.

Van 02/05/19 15:15:53

to elena.shustrova

"just a hero" - probably too much ....

(during my youth I had to walk up to forty km a day)

and when moving around your favorite city - only a matter of timely choice of "recreation places"

py.sy. on the second day he adapted and "samurai running" on the ice already gave odds to the natives ;-)

Register or login to comment.

Login Password

Registration

The most fabulous pictures of the Snow Petersburg

Komsomolskaya Pravda

are different

Anna Sukhodova

January 18, 2016 14:28

A delightful winter came to the northern capital. Citizens share photos on social networks

Citizens share photos on social networks

PHOTO: instagram.com/sv.starikova/

At the end of December, Petersburg was flooded with rain, then twenty degrees of frost struck. Now the weather has more than rewarded the townspeople for all the torment.

A delightful winter came to the northern capital last weekend. Slow snow was falling, and the trees were covered with frost. This made our beautiful city even more fabulous than usual. Residents and tourists happily shared pictures on social networks.

In two days, more than a thousand of them appeared on Instagram alone. And whatever photography is, it's a masterpiece. fluffy city0007

- It was incredibly beautiful today. As if the whole of Petersburg was plunged into a fairy tale. High spirits for the next week is guaranteed! users noted.

Today's frosted city // Today's frosted city Photo: smelov.photo

Others admitted that because of the fine weather, they refused transport and walked all day long - admired. Luckily, the cold weather is over for the weekend. As if on purpose so that people could enjoy the wonders of nature to their fullest.

Luckily, the cold weather is over for the weekend. As if on purpose so that people could enjoy the wonders of nature to their fullest.

#Peter #beloved #snowy #city #blue #lantern #branches #winter #January #January2016 #St. #petersburg #sbpru #spbrussia #piter #piterfoto #piteronlinePhoto: elena_tesoro

There were also those who thanked the officials that this year they decided to abandon reagents - there is no brown slurry on the roads now. And instead of dirt, even in the crowded center, everything is clean and white-white.

Everything is white, and people are walking along the frozen canals in St. Petersburg #allwhiteeverything #stpete #instagramrussia #instagram of the week #vsco #vscohub #vscogrid #vscorussia #so I'm filming #peter #spb #peterburg #petersburg #piteronline #instapiter #petersburg #lovespb #ohmyrussia # vsco_hubPhoto: head_in_clouds_

- Beautiful winter again today! Thank you for returning to childhood without reagents. I have already forgotten how cheerfully the snow creaks underfoot, - says Kirill Shamanov.

just bluePhoto: petrosphotos

And even the frosts, which again returned to the city on Monday, could not spoil the people's mood.

Magic day!!! #spb_guide#ilovespb#gallery_of_all#igworldclub#worldplaces#spbgram#ig_russia#igs#igs_europe#lovelyrussia#gopitershare#russiaphoto#russiaphoto_rus#rusphoto#russiandiary#picturetokeep_hdr#ok_hdr#tv_hdr#kings_meteo#kings_hdr#love_petersburg#mskpit#versatile_photo_#spbfull#be_one_city #petersburgcity#petersburgmycity#spbcamPhoto: natalia_krasnova_

- St. Petersburg hasn't had such a beautiful winter for a very long time! It’s cold outside, but when you see all this beauty, you forget about the frost and enjoy the snow-covered landscapes,” Darina Malinovskaya wrote on VKontakte.

#sunnyday#sunny#frozenday#frozen#daschund#mylovelydog#winerday#winter#wintergram #winter #spb #saintpetersburg #spbgram #petermyeyes #peterfmPhoto: anelabulen 9

Winter fairy tale in St. Petersburg # peter # st. petersburg # winter # spb #spb #saintpetersburg # marsovopole #spbgram March 2021

Acting EDITOR-IN-CHIEF - NOSOVA OLESIA VYACHESLAVOVNA.