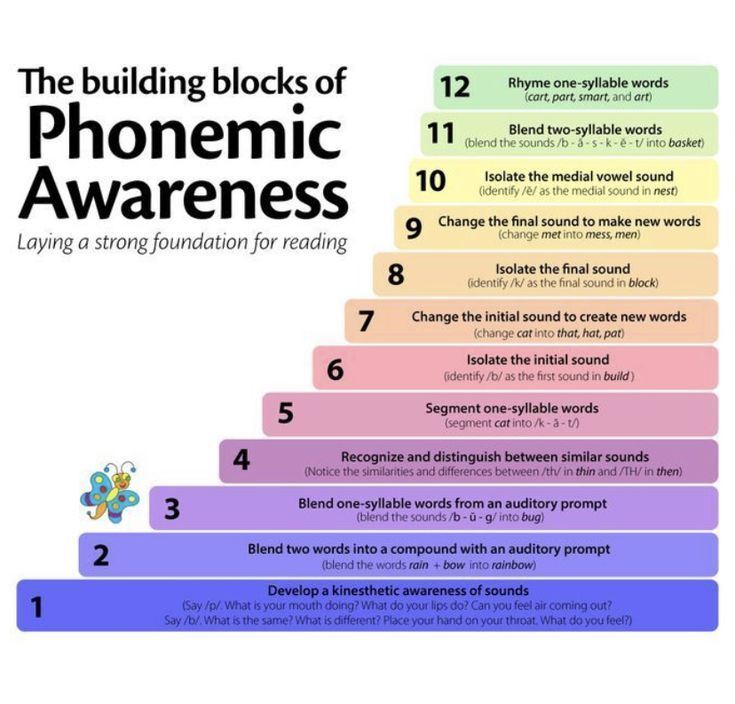

Phonological awareness components

Phonemic Awareness | Phonological Awareness :: Read Naturally, Inc.

What Is Phonemic Awareness?

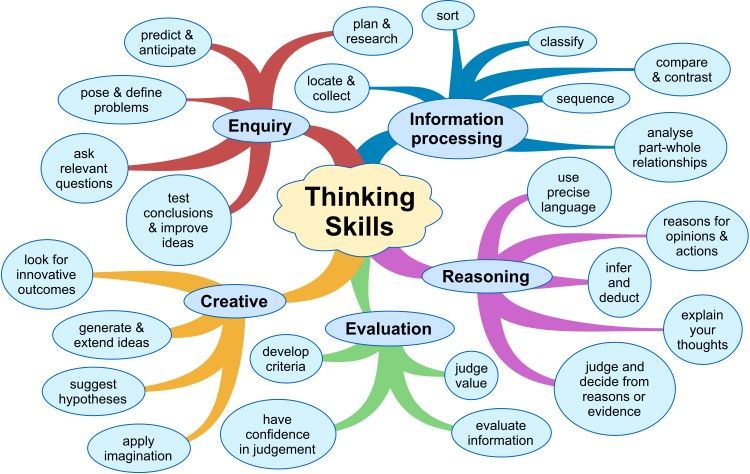

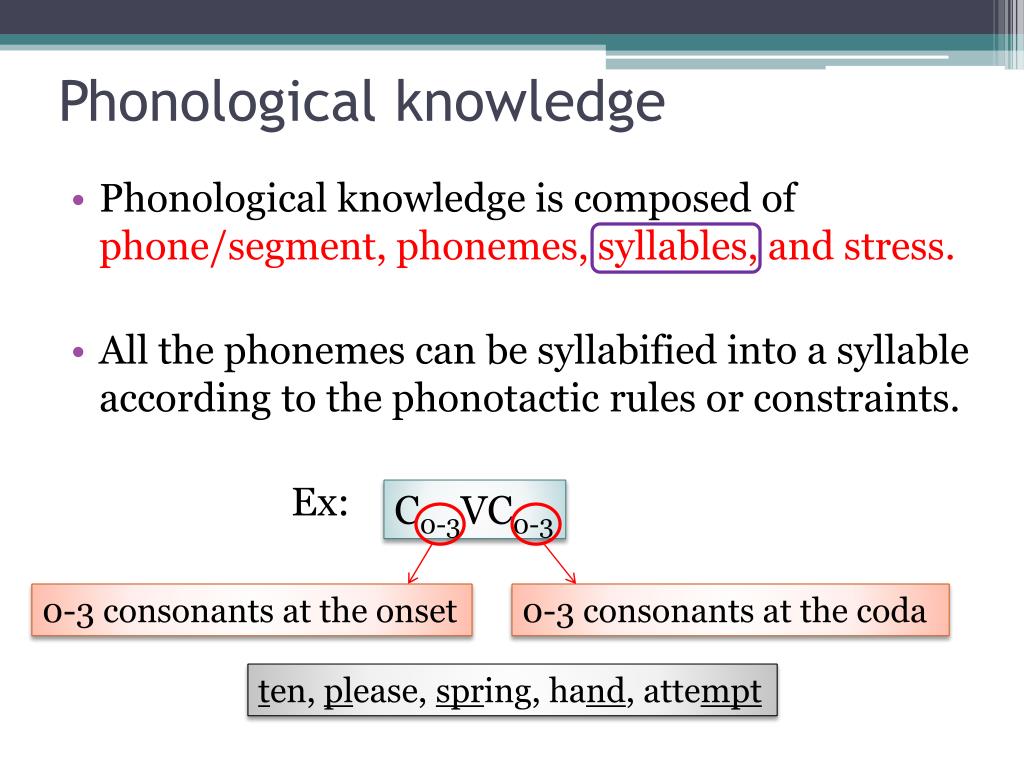

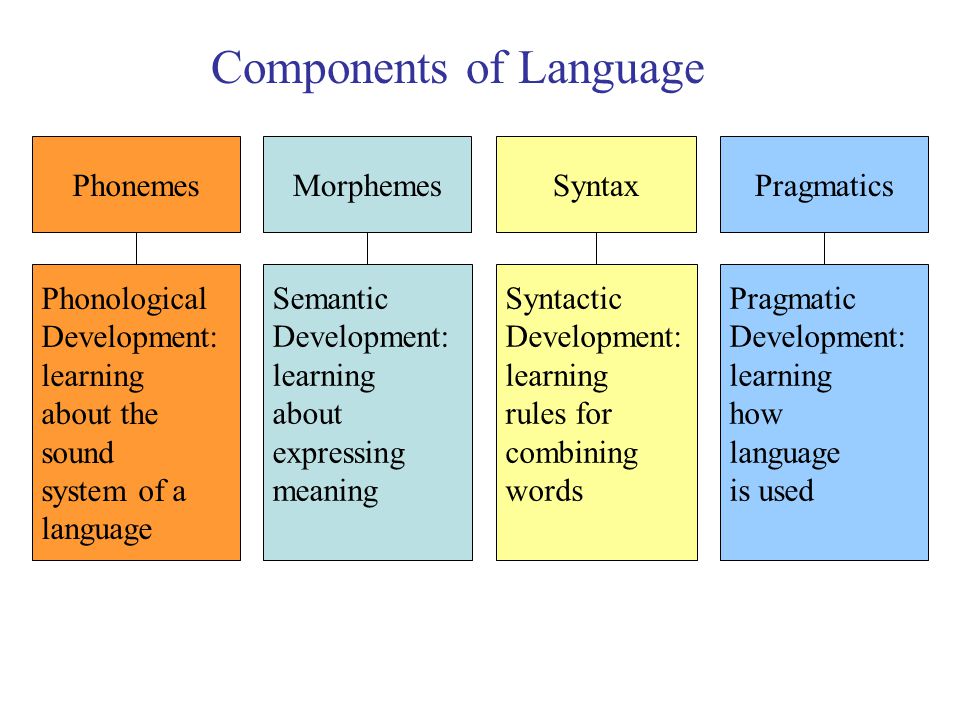

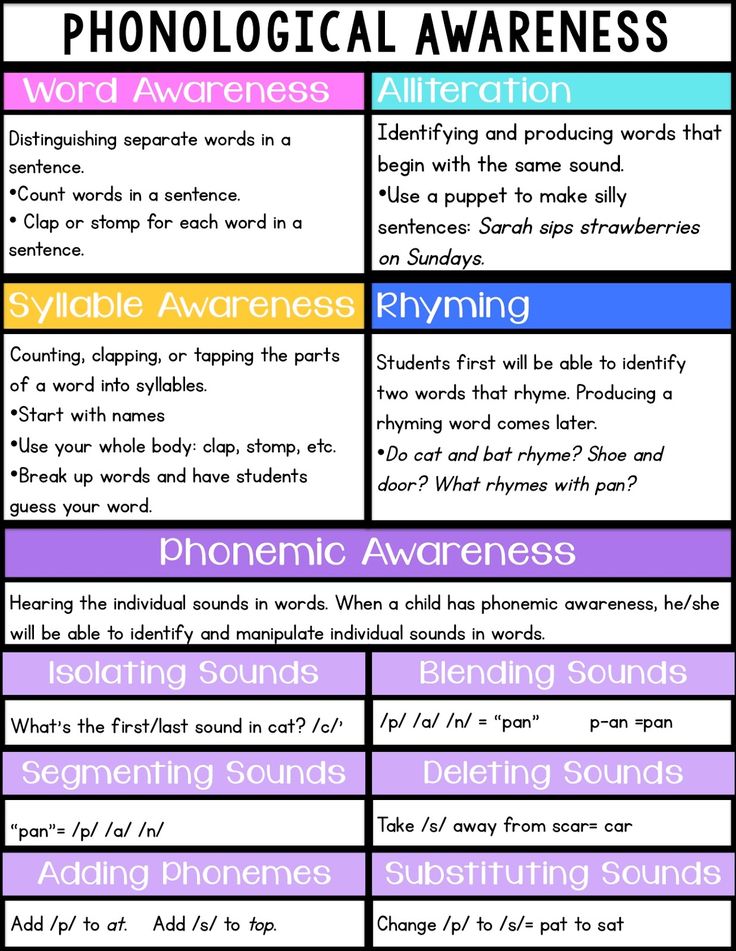

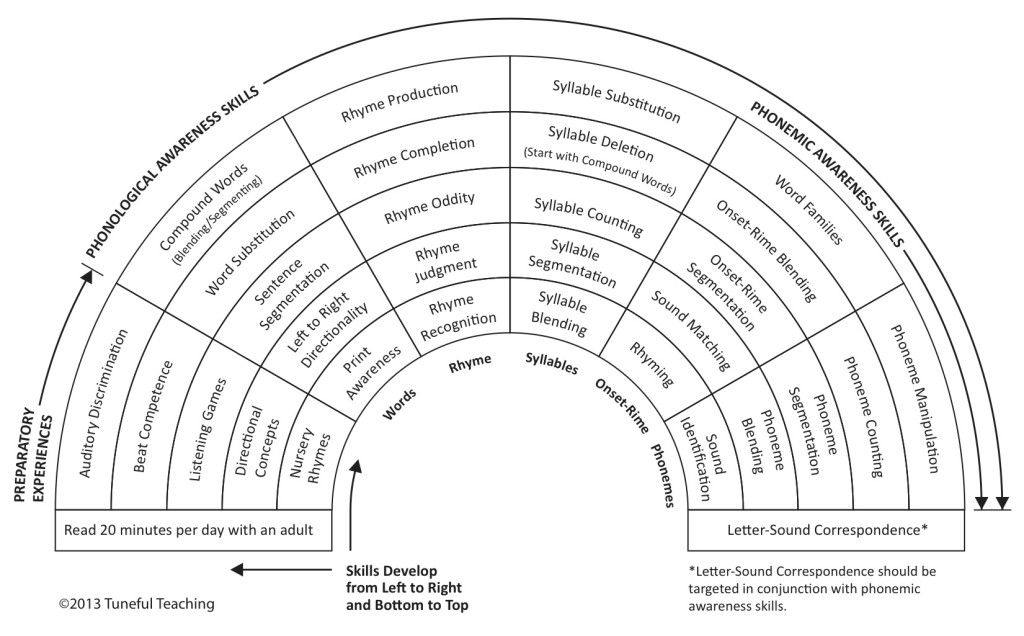

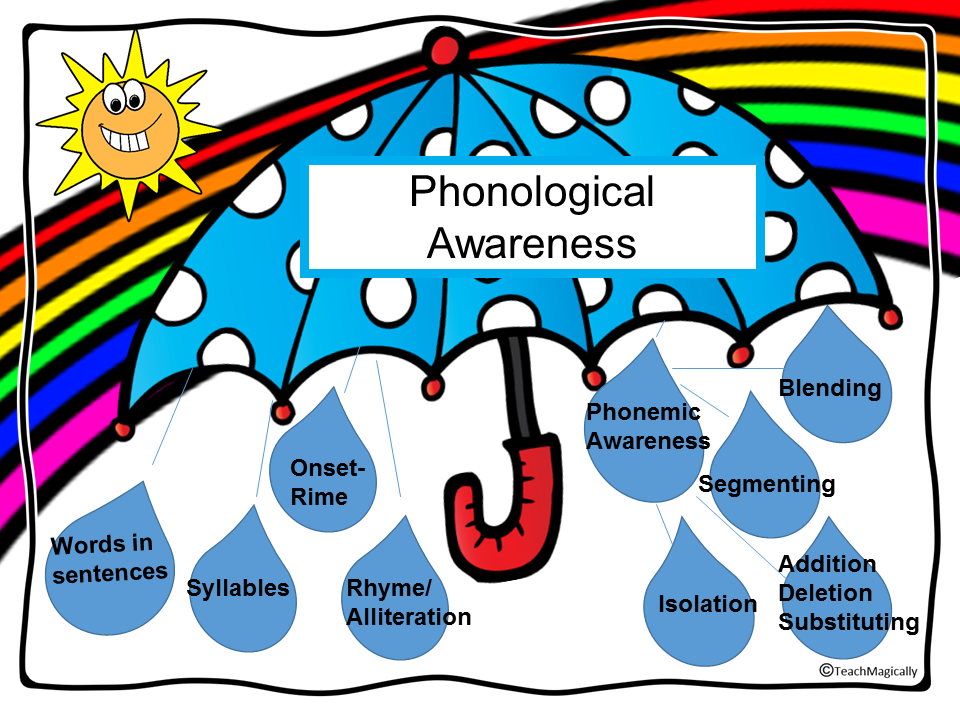

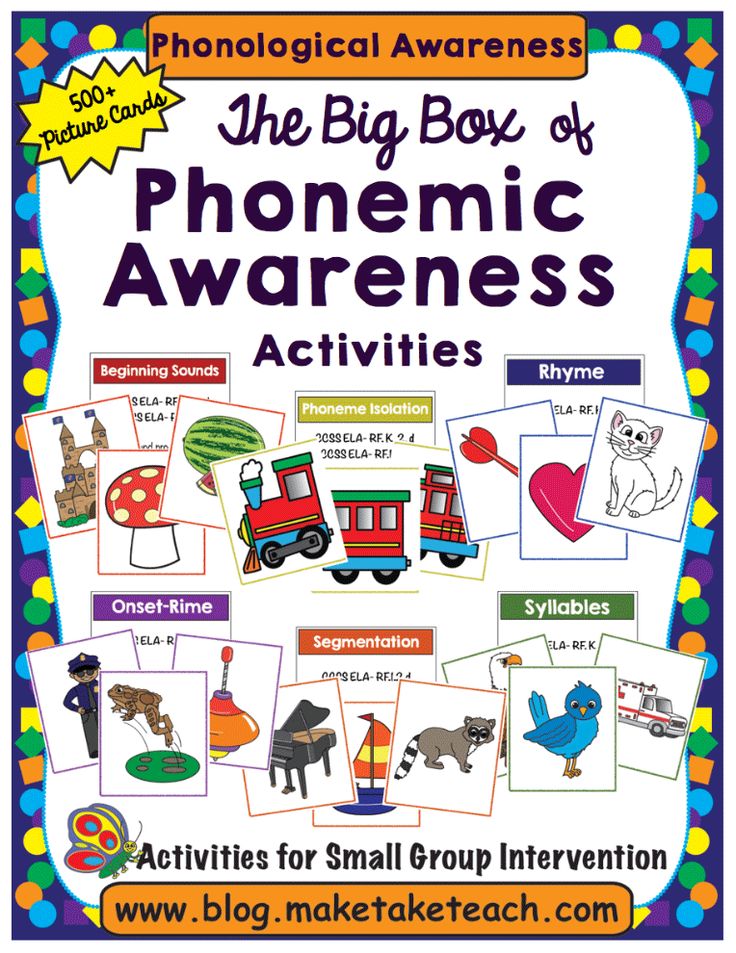

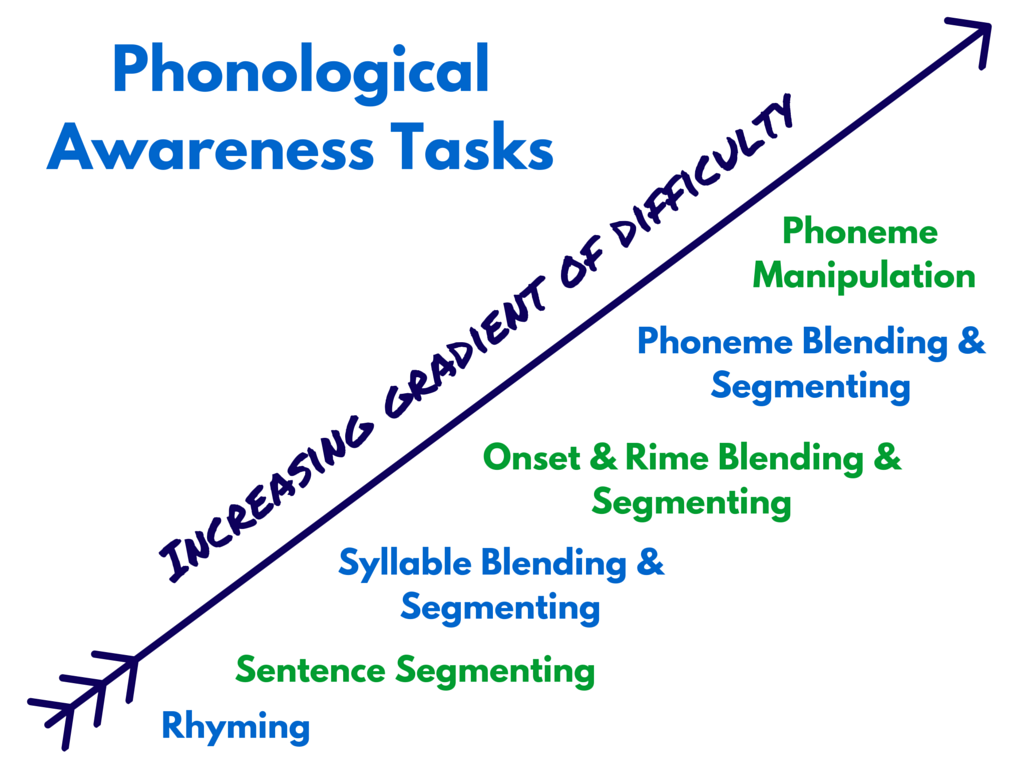

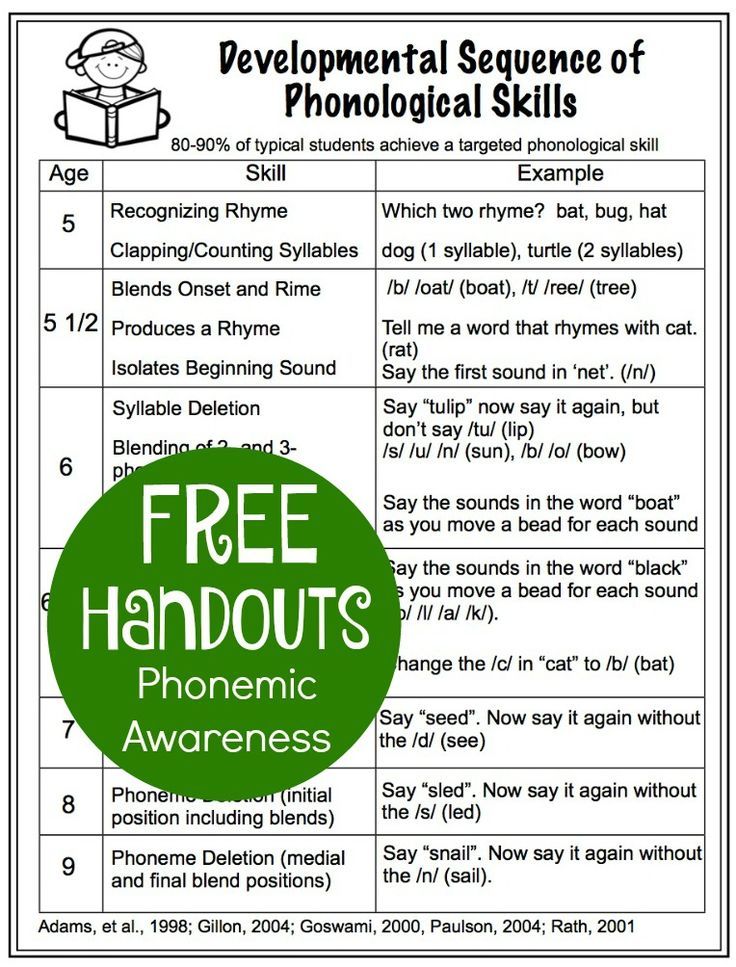

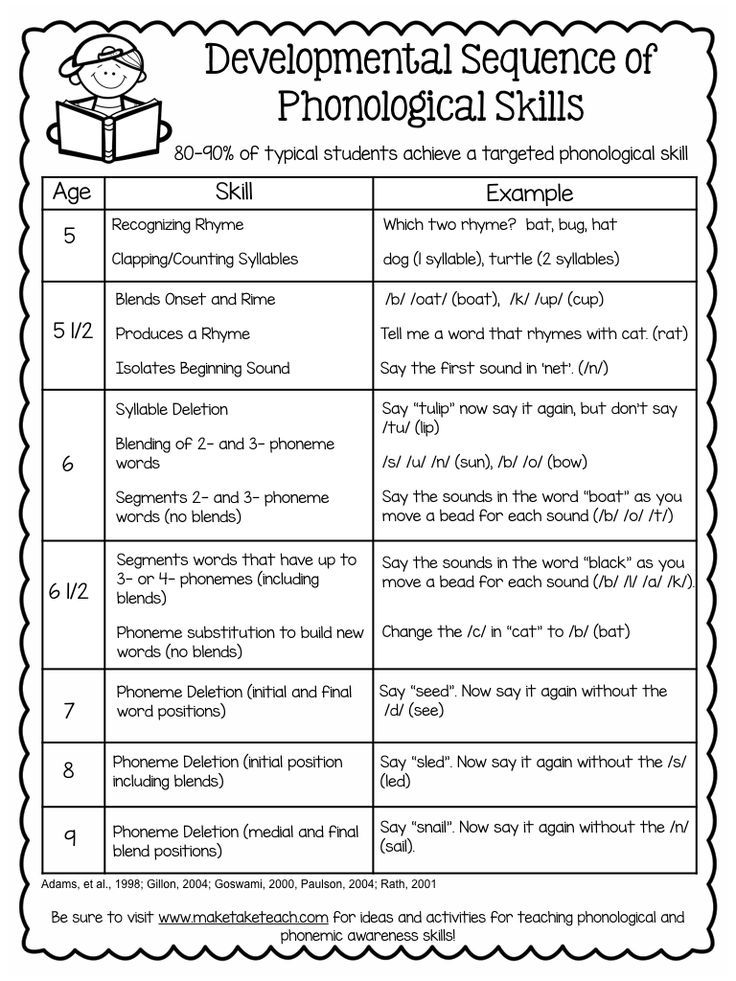

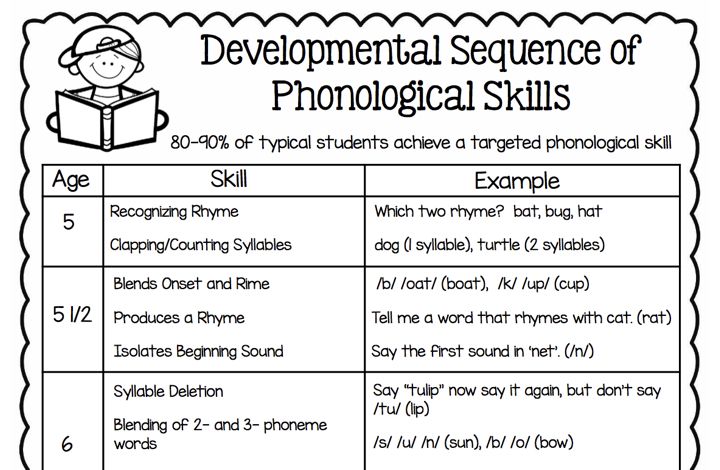

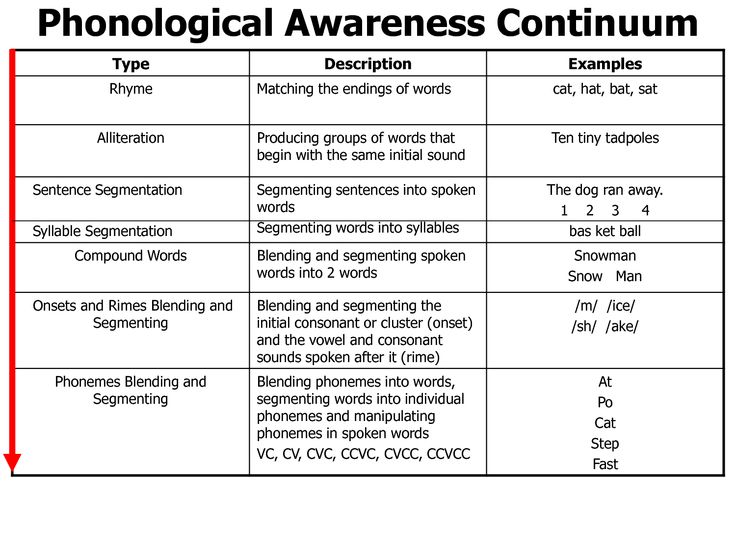

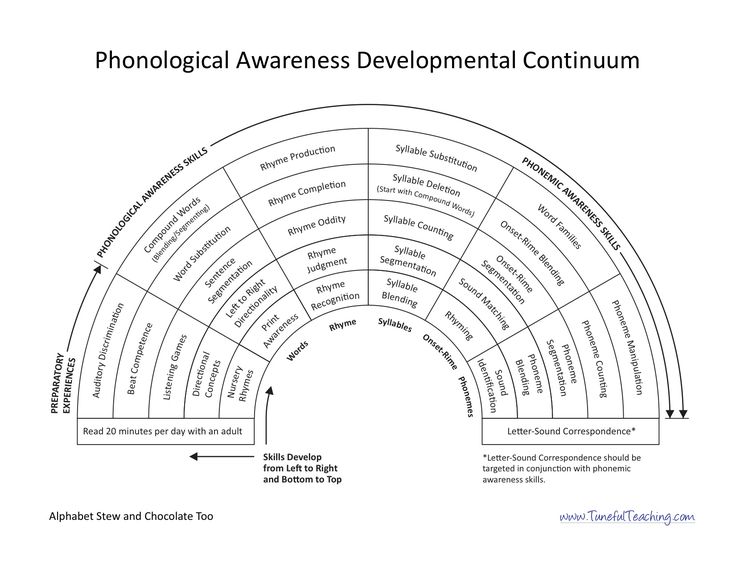

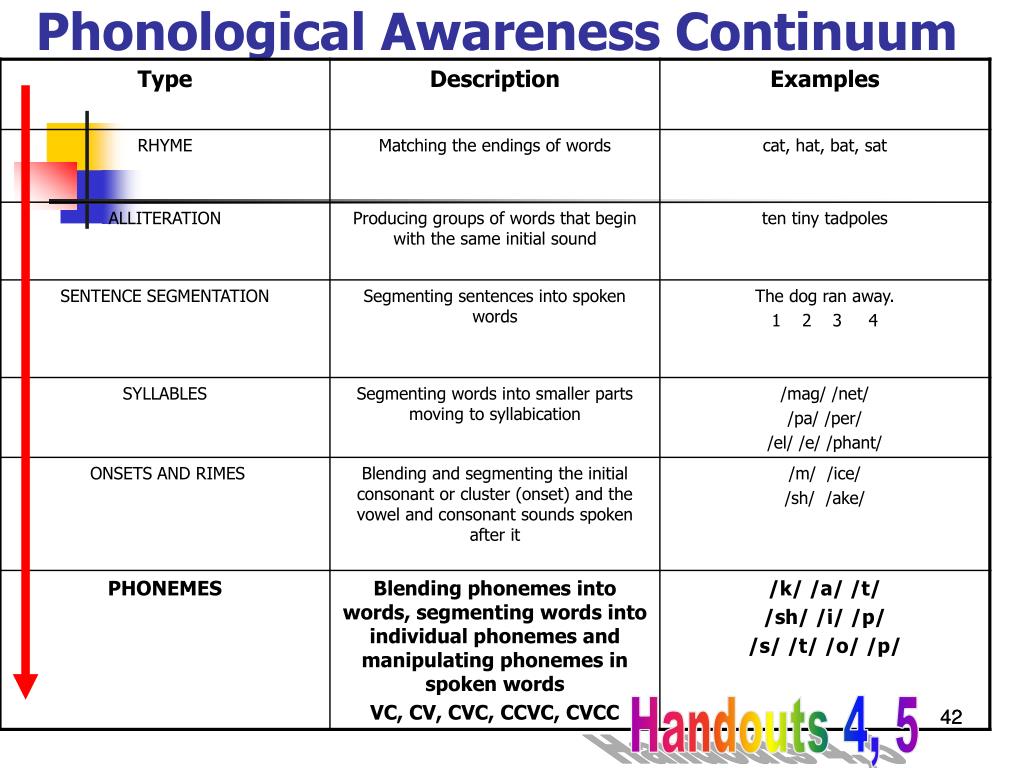

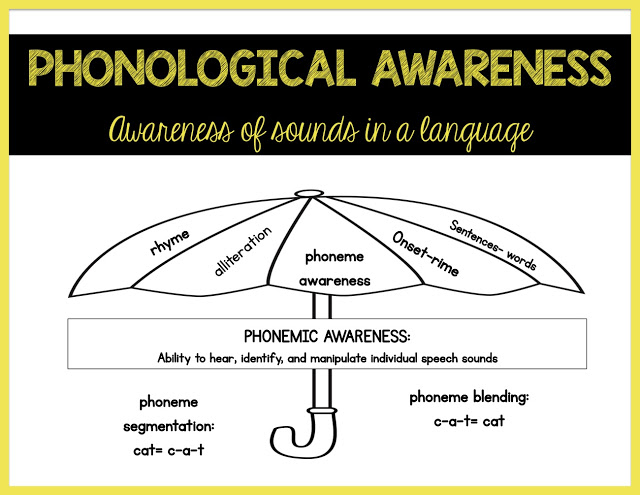

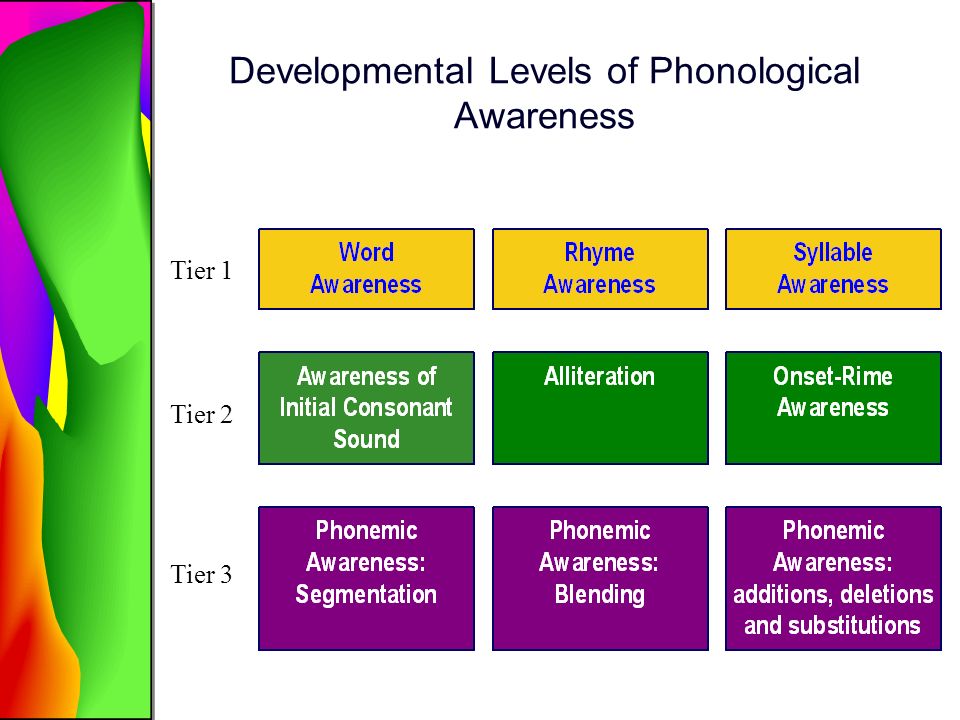

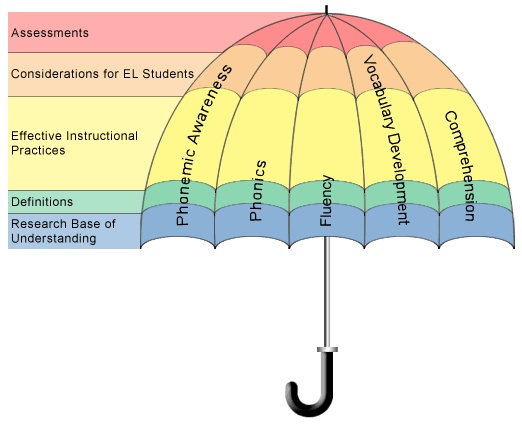

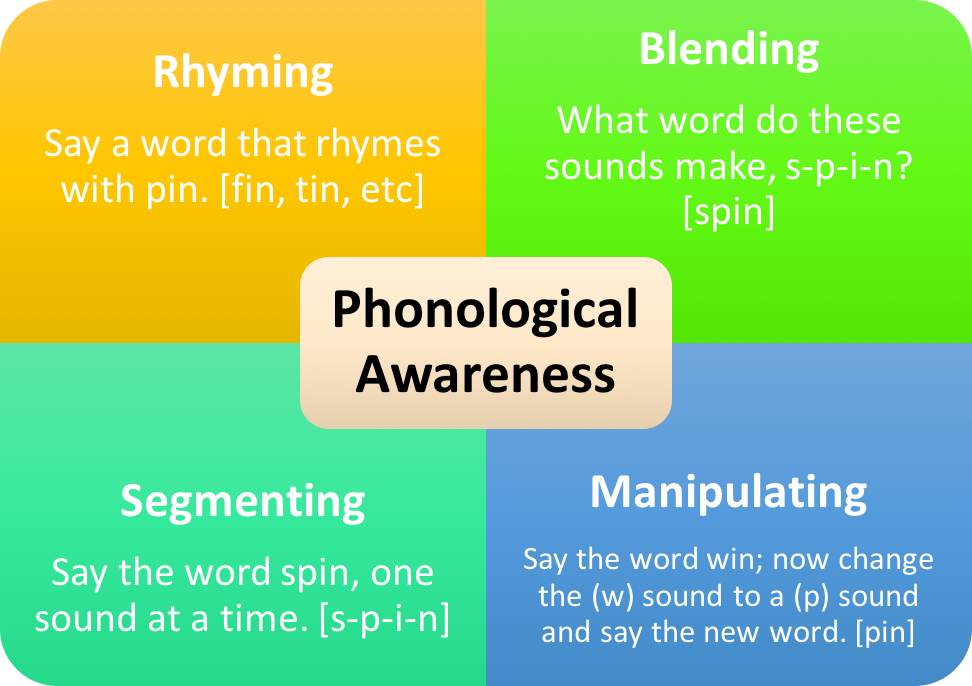

Phonological awareness is an umbrella term that includes four developmental levels:

- Word awareness

- Syllable awareness

- Onset-rime awareness

- Phonemic awareness

Phonemic awareness is the understanding that spoken language words can be broken into individual phonemes—the smallest unit of spoken language.

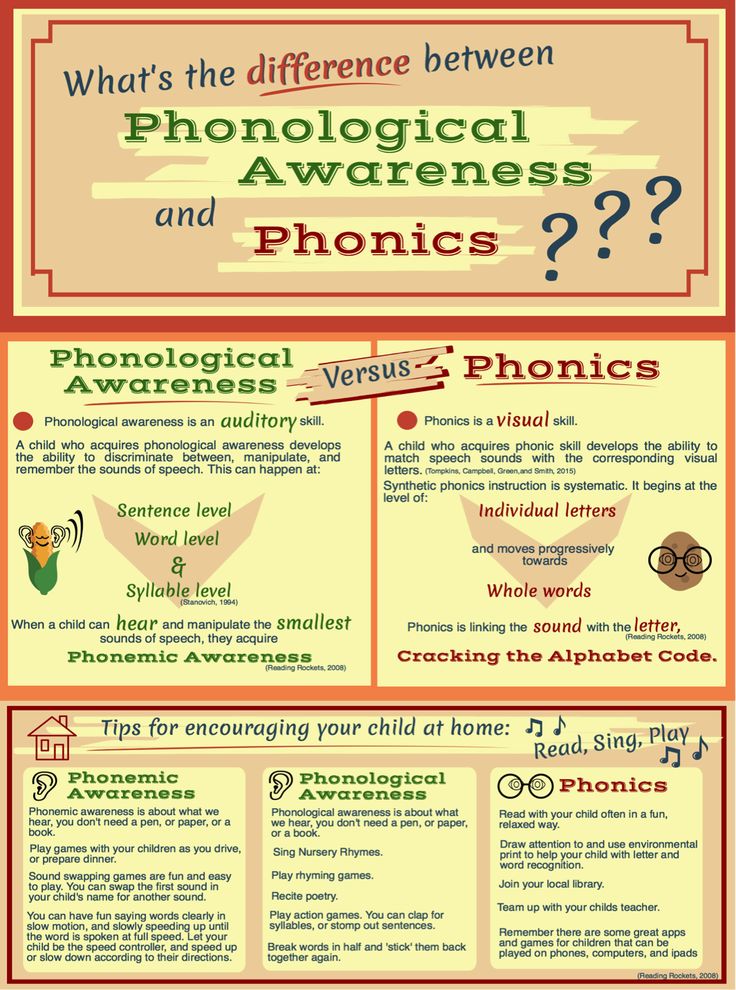

Phonemic awareness is not the same as phonics—phonemic awareness focuses on the individual sounds in spoken language. As students begin to transition to phonics, they learn the relationship between a phoneme (sound) and grapheme (the letter(s) that represent the sound) in written language.

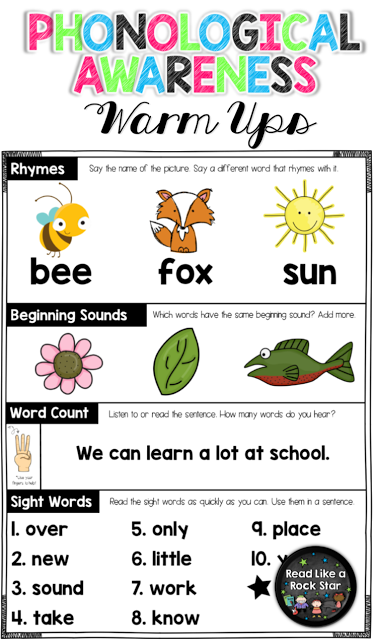

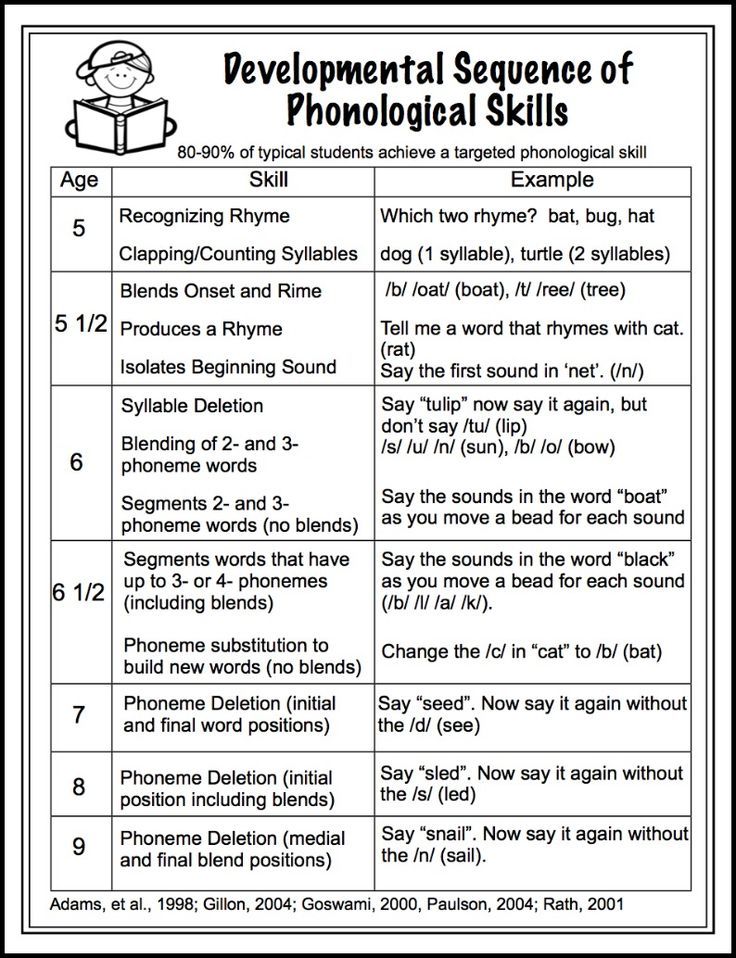

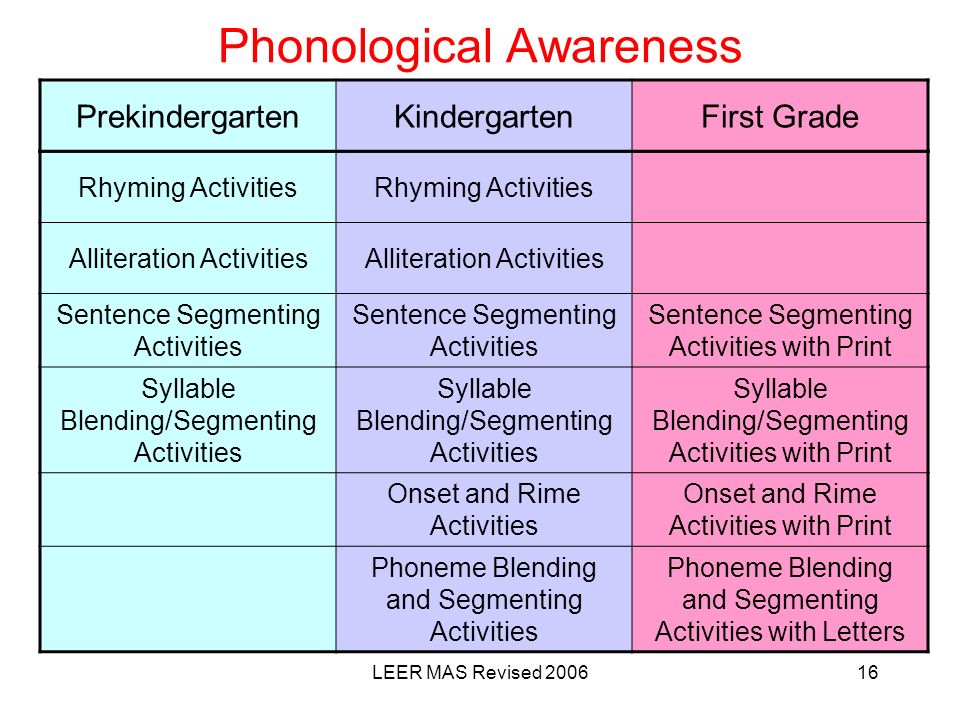

To develop phonological awareness, kindergarten and first grade students must demonstrate understanding of spoken words, syllables, and sounds (phonemes).

Read Naturally programs that develop phonemic awareness

Why Phonemic Awareness Is Important

First of all, phonemic awareness performance is a strong predictor of long-term reading and spelling success (Put Reading First, 1998). Students with strong phonological awareness are likely to become good readers, but students with weak phonological skills will likely become poor readers (Blachman, 2000). It is estimated that the vast majority—more than 90 percent—of students with significant reading problems have a core deficit in their ability to process phonological information (Blachman, 1995).

In fact, phonemic awareness performance can predict literacy performance more accurately than variables such as intelligence, vocabulary knowledge, and socioeconomic status (Gillon, 2004). The good news is that phonological awareness is one of the few factors that teachers are able to influence significantly through instruction—unlike intelligence, vocabulary, and socioeconomic status (Lane and Pullen, 2004).

Many students (75%) enter kindergarten with proficient phonemic awareness skills. The 25% of students who have not mastered these skills are from all socio-economic backgrounds and need explicit instruction in phonemic awareness. When instruction is engaging and developmentally appropriate, researchers recommend that all kindergarten students receive phonemic awareness instruction (Adams, 1990).

When instruction is engaging and developmentally appropriate, researchers recommend that all kindergarten students receive phonemic awareness instruction (Adams, 1990).

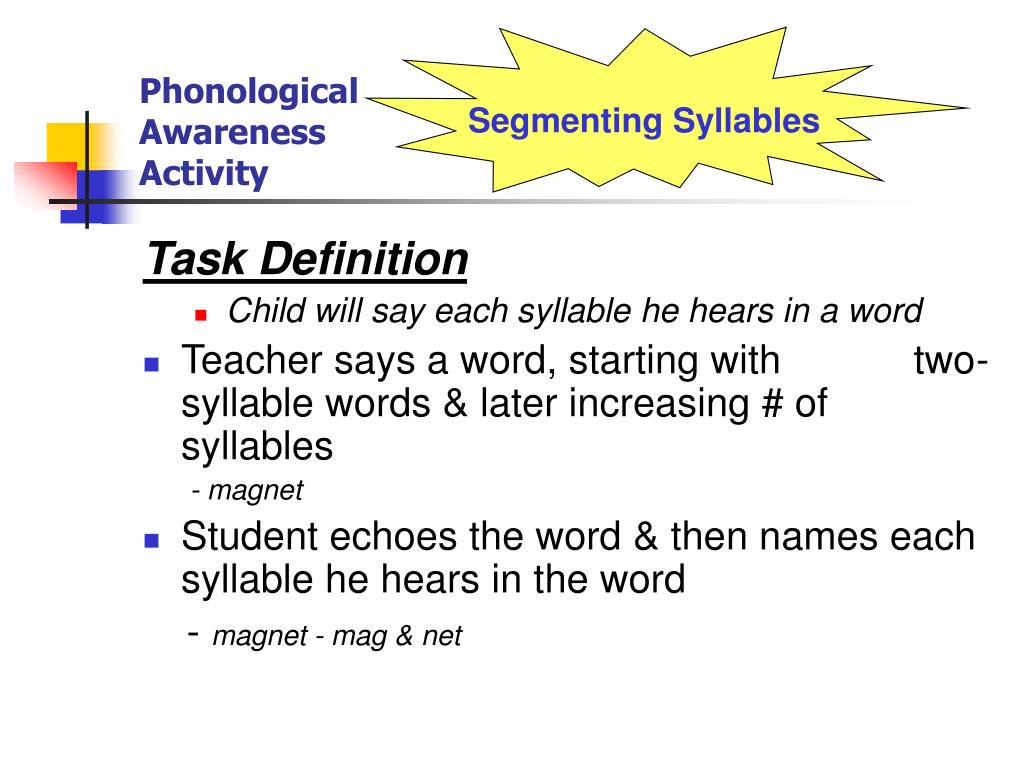

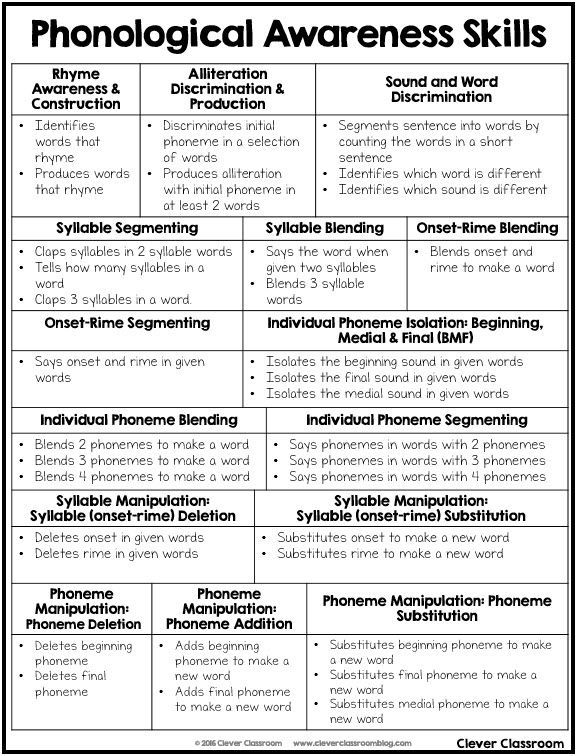

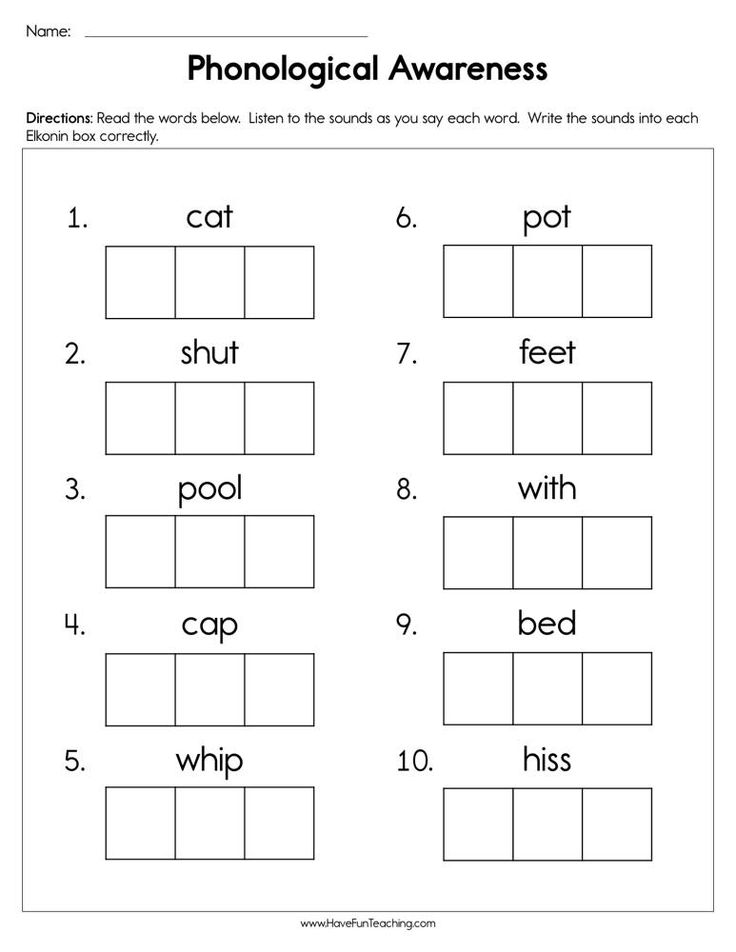

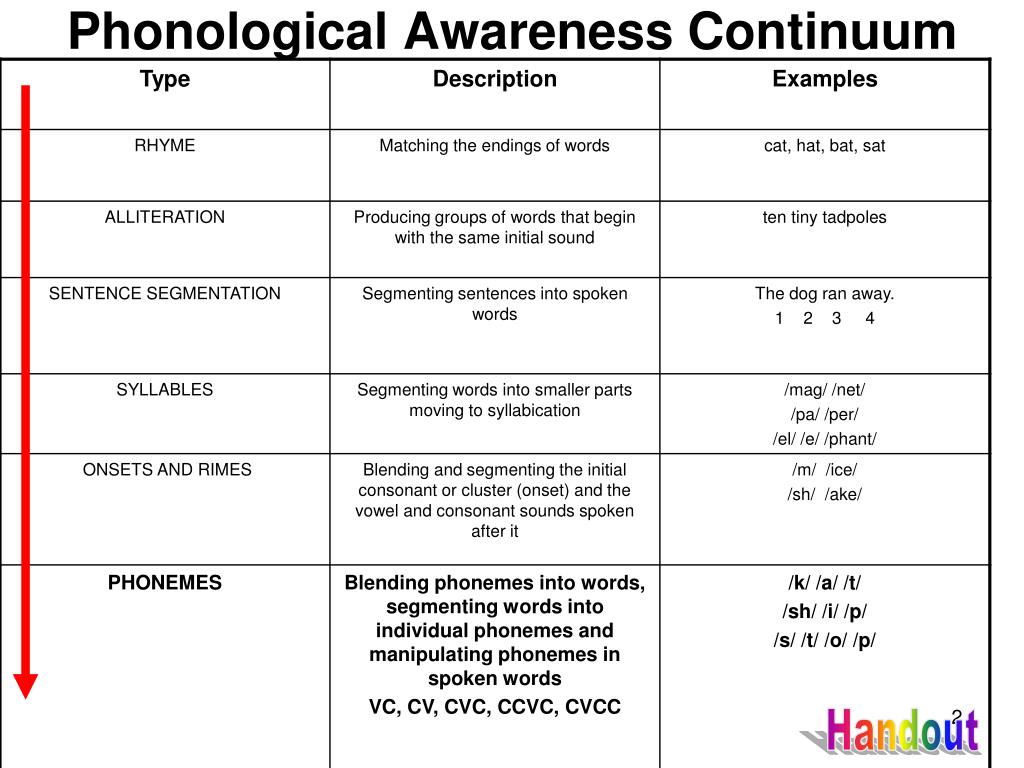

Phonological Awareness Skills

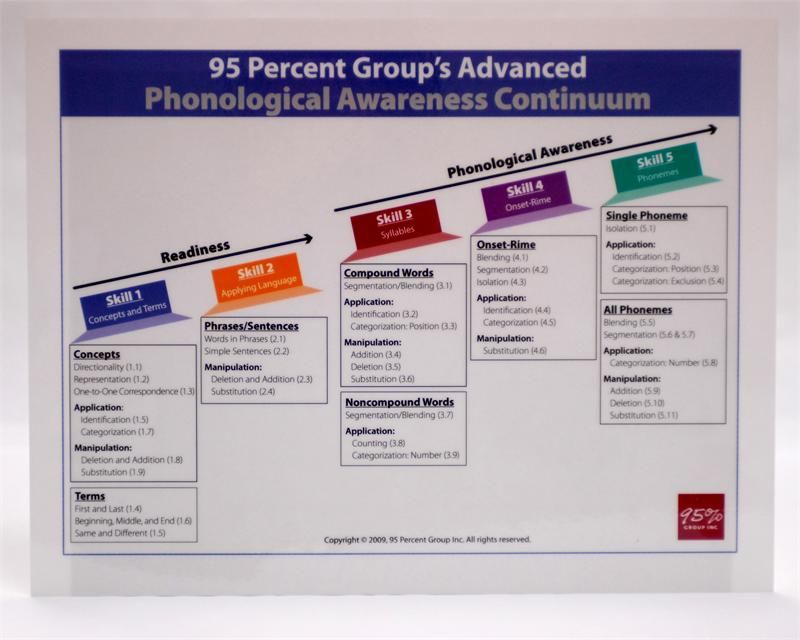

The following table shows how the specific phonological awareness standards fall into the four developmental levels: word, syllable, onset-rime, and phoneme. The table shows the specific skills (standards) within each level and provides an example for each skill.

| Less Complex | | More Complex | ||

| Word Awareness | Syllable Awareness | Onset-Rime Awareness | Phoneme Awareness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less Complex | Sentence Segmentation Tap one time for every word you hear in the sentence:

I like cookies. | Rhyme Recognition Do these two words rhyme: ham, jam? (yes) | Isolation What is the first sound in fan? (/f/) What is the last sound in fan? (/n/) What is the middle sound in fan? (/a/) | |

| | Rhyme Generation Tell me a word that rhymes with nut. (cut) | Identification Which word has the same first sound as car: fan, corn, or map? (corn) | ||

| Categorization Which word does not belong: mat, sun, cat, fat? (sun) | Categorization Which word does not belong? bus, ball, house? (house) | |||

| Blending Listen as I say two small words: rain … bow.  Put the two words together to make a bigger word. (rainbow) | Blending Put these word parts together to make a whole word: rock•et. (rocket) | Blending What word am I saying? /b/ … /ig/? (big) | *Blending What word am I saying /b/ /ĭ/ /g/? (big) | |

| Segmentation Clap the word parts in rainbow. (rain•bow) How many times did you clap? (two) | Segmentation Clap the word parts in rocket. (roc•ket) | Segmentation Say big in two parts. (/b/ … /ig/) | *Segmentation How many sounds in big? (three) Say the sounds in big. (/b/ /ĭ/ /g/) | |

| Deletion Say rainbow. Now say rainbow without the bow. (rain) | Deletion Say pepper.  Now say pepper without the /er/. (pep) |

Deletion Say mat. Now say mat without the /m/. (at) | Deletion Say spark. Now say spark without the /s/. (park) | |

| Addition Say park. Now add /s/ to the beginning of park. (spark) | ||||

| More Complex | Substitution The word is mug. Change /m/ to /r/. What is the new word? (rug) | |||

*Integrated instruction in phoneme segmenting and blending provides the greatest benefit to reading acquisition (Snider, 1995).

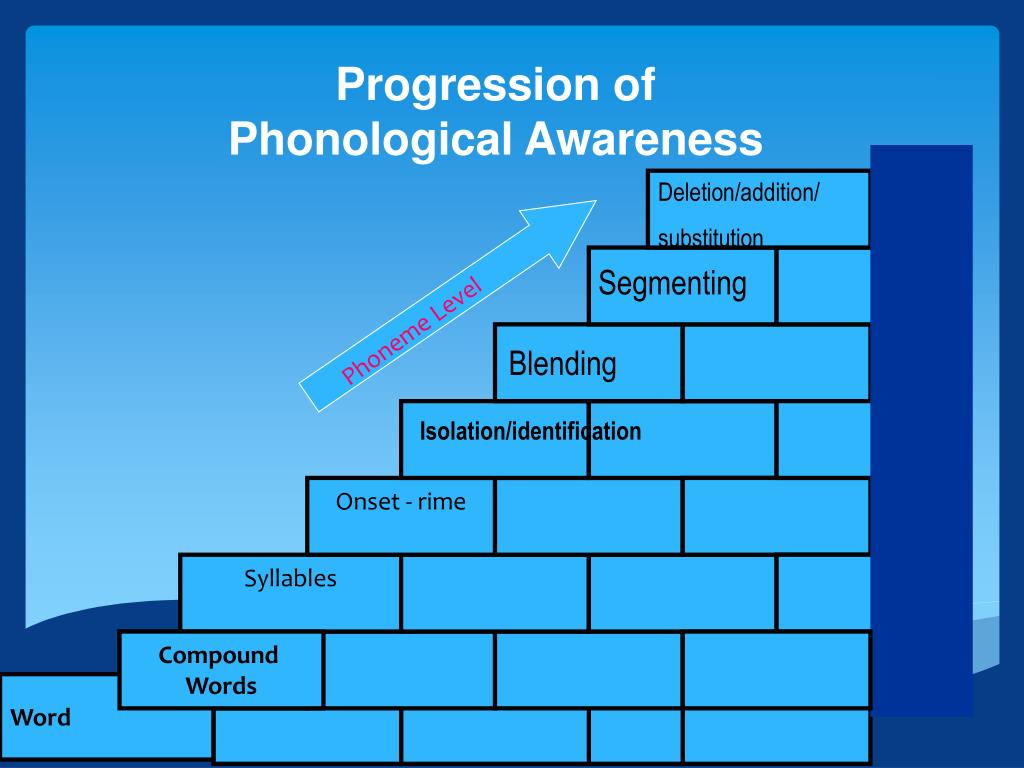

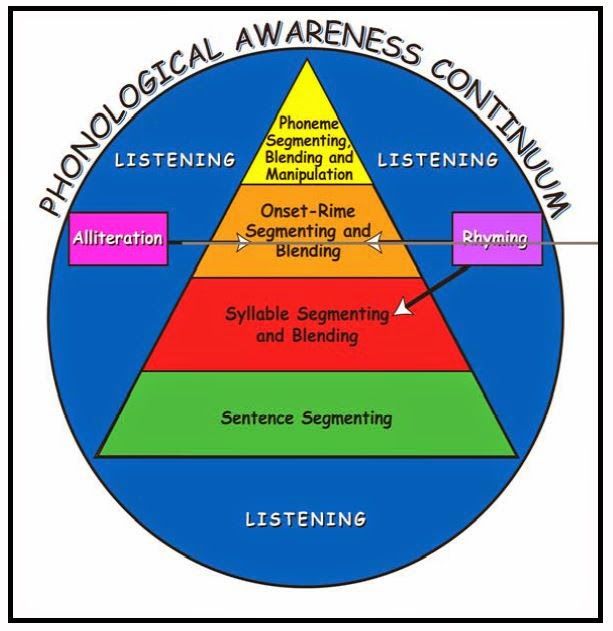

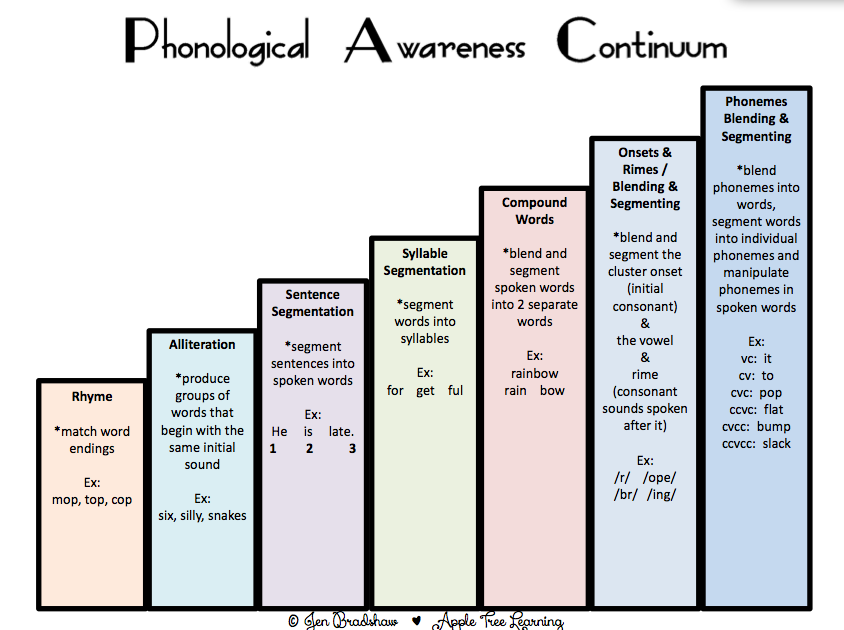

Instruction should be systematic. Notice the arrow across the top. The levels become more complex as students progress from the word level to syllables, to onset and rime, and then to phonemes.

Notice the arrow along the left-hand side. Students progress down each level—learning increasingly more complex skills within a level.

For example, look at the Phoneme Awareness column. Students learn to isolate, identify, and categorize phonemes first. Then students are taught to blend phonemes to make a word before they are taught to segment a word into phonemes—which is typically more difficult. The most challenging phonological awareness skills are at the bottom: deleting, adding, and substituting phonemes.

Blending phonemes into words and segmenting words into phonemes contribute directly to learning to read and spell well. In fact, these two phonemic awareness skills contribute more to learning to read and spell well than any of the other activities under the phonological awareness umbrella (National Reading Panel, 2000; Snider, 1995).

So, as we plan phonological awareness instruction, our goal is to systematically move students as quickly as possible toward blending and segmenting at the phoneme level.

Consonant Phonemes

There are two types of consonant phonemes:

| Type | Description | Phonemes |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous sounds* | A sound that can be pronounced for several seconds without any distortion. | /f/ • /l/ • /m/ • /n/ • /r/ • /s/ • /v/ • /w/ •/y/ • /z/ • /a/ • /e/ • /i/ • /o/ • /u/ |

| Stop sounds | A sound that can be pronounced for only an instant. Avoid adding /uh/. | /b/ • /d/ • /g/ • /h/ • /j/ • /k/ • /p/ • /t/ |

*Blending words with continuous sounds is easier than blending words with stop sounds.

The continuous sounds can be pronounced for several seconds without distortion. The stop sounds can be pronounced only for an instant. It is important to avoid adding /uh/ to a stop sound as it is pronounced—which confuses students. As new phonological awareness skills are introduced, using continuous sounds may be easier at first.

Read Naturally Programs That Develop Phonemic Awareness

Funēmics: A Phonemic Awareness Program for Small GroupsRead Naturally’s Funēmics is a systematic, program for pre-readers or struggling beginning readers that teaches all of the phonological awareness standards. Each lesson builds on skills taught in previous lessons, adding just a few elements at a time. With minimal preparation, teachers or aides present scripted instruction to small groups of students, using an interactive display (with brightly illustrated pages and interactive widgets) viewed on a tablet or whiteboard. Funēmics is entirely pre-grapheme.

Learn more about how Funēmics teaches phonological awareness skills:

- Learn more about Funēmics

- Funēmics sampler

- Research basis for Funēmics

Other Programs That Support Phonemic Awareness

The following programs do not focus on phonemic awareness but include phonemic awareness activities as part of a broader scope of instruction:

| Read Naturally® GATE Teacher-led instruction for small groups of early readers.  Focuses on phonics and fluency instruction with additional support for phonemic awareness and vocabulary. Focuses on phonics and fluency instruction with additional support for phonemic awareness and vocabulary.Learn more about Read Naturally GATE |

| Word Warm-ups® A mostly independent, audio-supported program for developing automaticity in phonics and decoding. Focuses on phonics with additional support for phonemic awareness and fluency. Learn more about Word Warm-ups (reproducible masters with audio) Learn more about Word Warm-ups Live (web application) |

| Signs for SoundsTM Teacher-led, small-group instruction for teaching regular phonetic spelling patterns and high-frequency words through spelling. Focuses on spelling and phonics with additional support for phonemic awareness. Learn more about Signs for Sounds |

Bibliography

Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Blachman, B. A. (2000). Phonological awareness. In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Rosenthal, P. D. Pearson, and R. Barr (eds.), Handbook of reading research, 3, pp. 483-502. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Blachman, B. A. (1995). Identifying the core linguistic deficits and the critical conditions for early intervention with children with reading disabilities. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Learning Disabilities Association, Orlando, FL, March 1995.

Gillon, G. T. (2004). Phonological awareness: From research to practice. New York: The Guilford Press.

Lane, H. B., and P. C. Pullen. (2004). A sound beginning: Phonological awareness assessment and instruction. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

National Institute for Literacy. (1998). Put reading first. <http://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/PRFbooklet.pdf>

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

(2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Snider, V. A. (1995). A primer on phonemic awareness: What it is, why it’s important, and how to teach it. School Psychology Review, 24(3), pp. 443-456.

Phonological and Phonemic Awareness: Introduction

Learn the definitions of phonological awareness and phonemic awareness — and how these pre-reading listening skills relate to phonics.

Letter of completion

After completing this module and successfully answering the post-test questions, you'll be able to download a Letter of Completion.

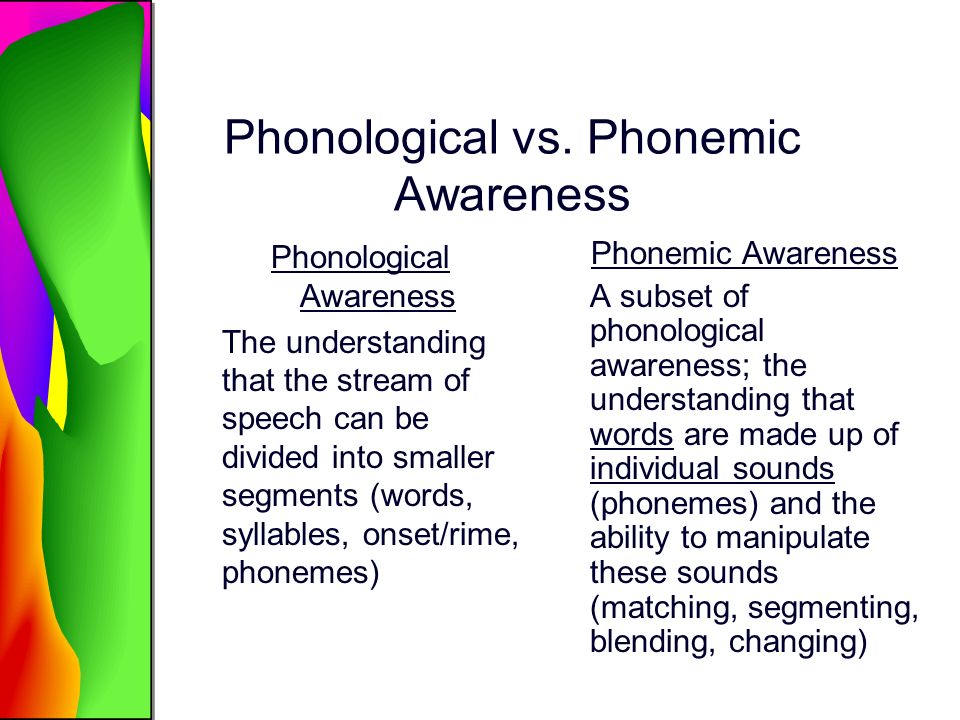

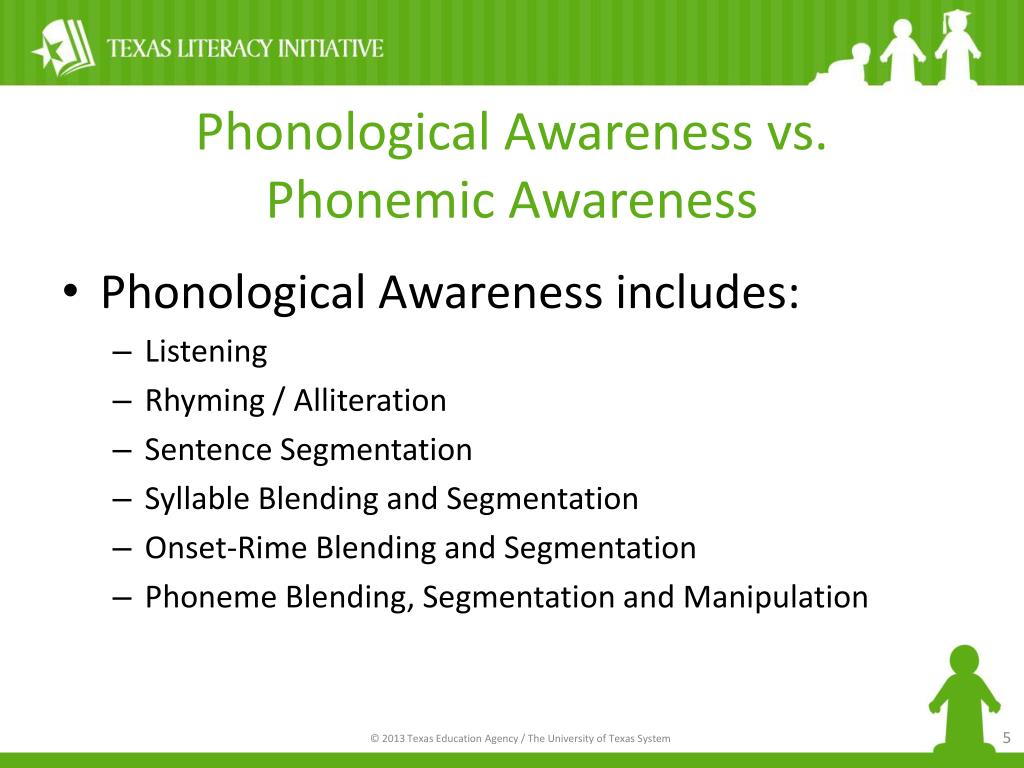

Phonological awareness and phonemic awareness: what’s the difference?

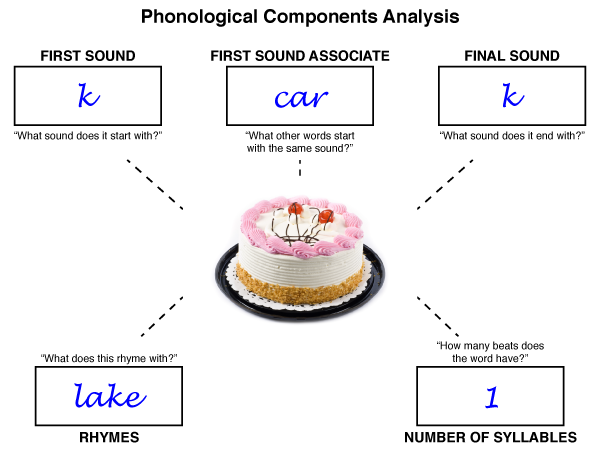

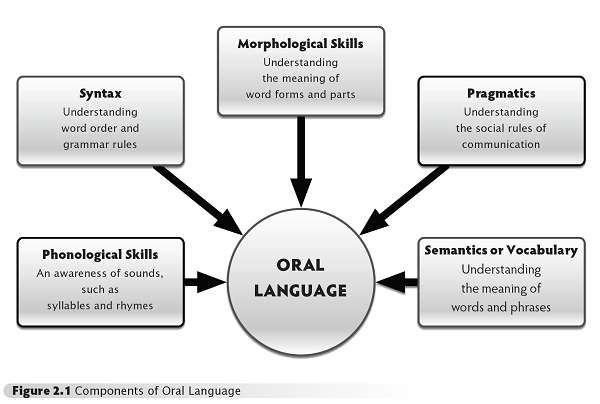

Phonological awareness is the ability to recognize and manipulate the spoken parts of sentences and words. Examples include being able to identify words that rhyme, recognizing alliteration, segmenting a sentence into words, identifying the syllables in a word, and blending and segmenting onset-rimes. The most sophisticated — and last to develop — is called phonemic awareness.

The most sophisticated — and last to develop — is called phonemic awareness.

Phonemic awareness is the ability to notice, think about, and work with the individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. This includes blending sounds into words, segmenting words into sounds, and deleting and playing with the sounds in spoken words.

Phonological awareness (PA) involves a continuum of skills that develop over time and that are crucial for reading and spelling success, because they are central to learning to decode and spell printed words. Phonological awareness is especially important at the earliest stages of reading development — in pre-school, kindergarten, and first grade for typical readers.

Explicit teaching of phonological awareness in these early years can eliminate future reading problems for many students. However, struggling decoders of any age can work on phonological awareness, especially if they evidence problems in blending or segmenting phonemes.

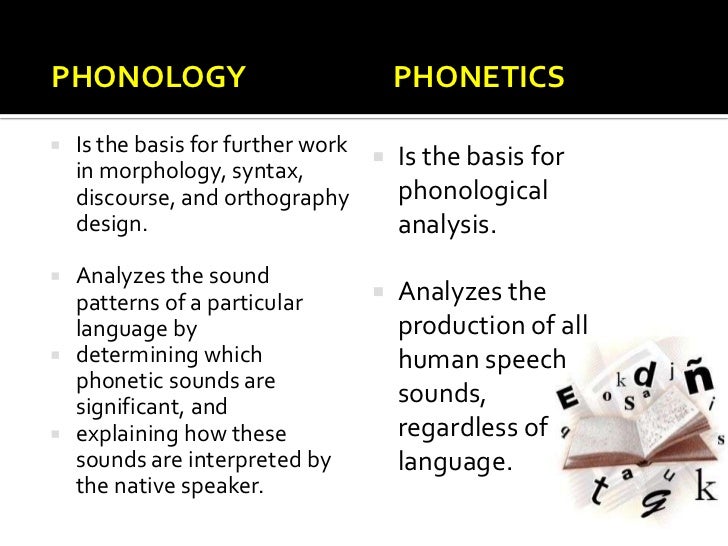

How about phonological awareness and phonics?

Phonological awareness refers to a global awareness of sounds in spoken words, as well as the ability to manipulate those sounds.

Phonics refers to knowledge of letter sounds and the ability to apply that knowledge in decoding unfamiliar printed words.

So, phonological awareness refers to oral language and phonics refers to print. Both of these skills are very important and tend to interact in reading development, but they are distinct skills; children can have weaknesses in one of them but not the other.

For example, a child who knows letter sounds but cannot blend the sounds to form the whole word has a phonological awareness (specifically, a phonemic awareness) problem. Conversely, a child who can orally blend sounds with ease but mixes up vowel letter sounds, reading pit for pet and set for sit, has a phonics problem.

44 phonemes

There are 26 letters in the English alphabet that make up 44 speech sounds, or phonemes.

Letters vs. phonemes

Dr. Louisa Moats explains to a kindergarten teacher why it is critical to differentiate between the letters and sounds within a word when teaching children to read and write.

Next: Phonological and Phonemic Awareness Pre-Test >

15 Learning Disorder Terms Parents Need to Know

1. Phonetics

Phonetics - this term refers to the sound structure of the language: the relationship between a letter or combination of letters (for example: chi, shu, tya, da) and speech sounds they represent.

Phonetics is the foundation of reading and writing skills. Thanks to phonetics, the child decodes written words in the process of reading.

2. Phonemes

A phoneme is the sound of speech. When we speak Russian, we make 42 different speech sounds. But there are only 33 letters in the Russian alphabet. This is one of the reasons why Russian is difficult to learn.

3. Phonemic perception

Phonemic perception is the ability to perceive individual speech sounds (phonemes) in words and work with them.

Learn how to develop phonemic awareness from an early age. nine0005

4. Phonological awareness

Phonological awareness is the awareness that words are made up of smaller parts (such as syllables and sounds).

The term includes a range of sound-related skills that a student needs to develop reading skills. As the child develops phonological awareness, he/she not only comes to understand that words are made up of small sound units (phonemes), but also learns that words can be broken down into larger sound "chunks" known as syllables. . nine0005

As the child develops phonological awareness, he/she not only comes to understand that words are made up of small sound units (phonemes), but also learns that words can be broken down into larger sound "chunks" known as syllables. . nine0005

5. Phonological accuracy

Phonological accuracy refers to the ability to correctly distinguish between individual phonemes (e.g., in similar-sounding words that begin with the same sound) or other aspects of phonology (e.g., rhyming, number of syllables).

Phonological accuracy is key to listening and reading skills. This allows the student to make a clear distinction between similar-sounding words (e.g. "heron" and "saber" or "picture" and "basket"), including morphological differences that can drastically change the word's meaning and/or grammatical function (e.g. " known" and "unknown" or "inserted" and "exposed"). nine0005

The ability to quickly and accurately identify speech sounds is critical to learning the rules of phonetics and matching spoken language to text correctly.

A child with well-developed phonological accuracy will more easily develop decoding skills, understand word and sentence structure, develop vocabulary, follow instructions, and participate more actively in class work.

Well developed phonological accuracy helps in:

-

Understanding and following verbal instructions

-

Listening skills

-

Development of reading skills

-

Learning the rules of phonetics

6. Phonological fluency

Phonological fluency is the understanding that words are made up of different sounds, and the ability to quickly and accurately identify and manipulate these sounds. nine0005

Phonological fluency is critical to learning to read. This allows the student to memorize sequences of sounds and manipulate them quickly and accurately. This makes it easier to both write words and decode them. The more effectively the reader is able to decode, the more of his cognitive resources (mental abilities) he can focus on understanding the text.

The more effectively the reader is able to decode, the more of his cognitive resources (mental abilities) he can focus on understanding the text.

A student with good phonological fluency will also find it easier to learn new words while reading. When confronted with a new word, a student who can accurately pronounce the word is more likely to recognize and understand its meaning. nine0005

Well-developed phonological fluency helps in:

-

Learning the rules of phonetics

-

Development of reading skills

-

Development of writing skills

7. Phonological memory

Phonological memory is the ability to retain speech sounds in memory. This is essential for spoken language and tasks such as comparing phonemes and making connections between phonemes and letters. It also helps with listening and reading understanding of sentences, as it allows you to remember the sequence of words in order. nine0005

nine0005

Phonological memory plays a key role in the development of oral and written language skills. This allows the student to:

-

Memorize and manipulate sound sequences

-

Associate spoken words with written ones

-

Memorize new words by determining their meanings

-

Remember the beginning of a sentence, listening to it to the end.

The ability to remember speech sounds is important for the correct understanding of sentences when changing the order of words in a sentence changes its meaning (for example, "The monkey bites the boy" and "The boy bites the monkey").

Accurate memory of word order also contributes to the construction of accurate ideas about the structure of sentences and the acquisition of knowledge about syntax.

A student with a well-developed phonological memory develops phonemic perception and decoding skills more easily, knowledge of vocabulary and sentence structure is formed. Such a student follows instructions better and takes a more active part in class work with presentations, etc. nine0005

Such a student follows instructions better and takes a more active part in class work with presentations, etc. nine0005

8. Auditory Processing / Auditory Perception

Auditory processing refers to what the brain does with the audio information it “hears”. This includes various skills such as identifying and locating sounds, listening to background noise, and processing what is heard when the sound is fuzzy.

When a student manipulates the auditory information he has heard, but it doesn't sound right, this is called an auditory processing disorder (or auditory perception disorder). nine0005

This can happen if the child has trouble understanding speech in background noise or has difficulty identifying where the sound is coming from. Or it could be a problem in distinguishing speech sounds that sound similar.

Learn 5 Common Hearing Loss (HAI) Myths!

9. Sequencing of audio information

Sequencing of audio information refers to the ability to identify and remember the order in which a series of sounds were presented. This is very important for matching sound sequences to letter sequences in decoding and writing. nine0005

This is very important for matching sound sequences to letter sequences in decoding and writing. nine0005

Organizing audio information is critical to developing speaking and writing skills. The ability to identify and remember the order of sounds in words is important for recognizing subtle differences between words (such as "pot" and "top") and for developing phonemic perception and decoding skills.

A student who has a well-developed ordering of sound information understands and absorbs information better, develops better oral and written speech skills and concentrates attention. Such a student becomes an expert reader and a successful student. nine0005

See also: How do weak cognitive skills affect learning?

10. Listening word comprehension

Listening word comprehension refers to the ability to accurately identify words heard based on auditory cues alone, without the aid of visual or contextual cues.

Listening comprehension of words is crucial for the development of oral speech and vocabulary, and therefore important for the development of reading and writing. This skill allows the student to accurately and efficiently identify words in speech and helps him form a correct understanding of the information presented by ear. nine0005

A student with well developed listening comprehension will find it easier to follow instructions and participate in class discussions; it is easier to answer questions, complete tasks and remember information; and it's much easier to become a proficient reader.

He will also find it easier to carry on a conversation in a noisy environment or when there are distractions.

11. Hearing accuracy

Hearing accuracy is the ability to accurately identify differences between sounds and correctly identify sound sequences. nine0005

Accuracy in listening is the foundation of speech and reading skills. This skill allows the student to quickly and accurately identify and distinguish between rapidly changing sounds, which is very important for distinguishing between phonemes (the smallest units of speech that distinguish one word from another).

This skill allows the student to quickly and accurately identify and distinguish between rapidly changing sounds, which is very important for distinguishing between phonemes (the smallest units of speech that distinguish one word from another).

A student with well-developed listening comprehension will find it much easier to follow instructions and participate in class work; it is easier to remember questions, tasks and information; and it's much easier to become a proficient reader. He will also be able to:

-

Read and write fast

-

Focus on verbally presented information

-

Maintain a conversation in noisy environments or when there are distractions.

12. Listening comprehension

Listening comprehension is the ability to understand consecutive sentences and extract meaning from what is heard.

Listening comprehension is one of the foundations of oral and written speech. To develop more complex speech skills, a child needs to develop good listening comprehension. Well developed listening comprehension allows the student to recognize the meanings formed by combinations of words and series of sentences.

To develop more complex speech skills, a child needs to develop good listening comprehension. Well developed listening comprehension allows the student to recognize the meanings formed by combinations of words and series of sentences.

A student with good listening comprehension will find it much easier to respond to assignments and class discussions; it will be easier to answer questions and remember information; and it is easier to become a proficient reader and a successful learner. He will also be able to do well:

-

Focus on oral information

-

Making sense of history

-

Correctly follow verbal instructions

-

Correctly understand and answer questions

Understanding the components of speech utterance - Almanac

*Fragment of the book "Language and Consciousness", ed. E.D. Chomsky, ed. Moscow State University, 1979, 217-226 C.

We have considered the process of forming a detailed speech utterance, in other words, the path that an utterance goes through, starting from the original idea and ending with a detailed speech message. This process, as we have shown, can be viewed as a process going from the inner meaning of the future utterance to a system of extended speech meanings. Now we will focus on the psychological analysis of utterance understanding, that is, on the process of decoding incoming speech information. nine0005

This process, as we have shown, can be viewed as a process going from the inner meaning of the future utterance to a system of extended speech meanings. Now we will focus on the psychological analysis of utterance understanding, that is, on the process of decoding incoming speech information. nine0005

This process begins with the perception of external, extended speech, then proceeds to understanding the general meaning of the utterance, and then to understanding the subtext of this utterance. Analysis of the process of understanding a speech message is one of the most difficult and, oddly enough, one of the least developed chapters of scientific psychology.

Problem

Psychologists approached the analysis of the process of understanding the meaning of a speech message differently, or the process of decoding a perceived speech statement. nine0005

Some authors assumed that in order to understand the meaning of a speech message, it is enough to have a strong and wide vocabulary, i. e. understand the meaning of each word, its subject relatedness, its generalizing function and master fairly clear grammatical rules by which these words are connected to each other.

e. understand the meaning of each word, its subject relatedness, its generalizing function and master fairly clear grammatical rules by which these words are connected to each other.

Thus, according to these ideas, the presence of an appropriate range of concepts, on the one hand, and a clear knowledge of the grammatical rules of the language, on the other, is decisive for understanding the message. nine0005

There is no reason to doubt that both of these points are absolutely necessary for understanding a speech message. However, it is unlikely that these two conditions are sufficient for deciphering its meaning, no matter what form - oral or written message - it wears.

Another group of psychologists and linguists does not believe that the condition for understanding a speech message is only the presence of the necessary range of representations and knowledge of the system of grammatical rules, according to which these words are combined with each other; they indicate that the process of understanding is of a completely different nature: it begins with the search for the general thought of the utterance, which is the content of this form of mental activity, and only then moves to the lexico-phonemic level (establishing the meaning of individual words) and to the syntactic level (deciphering the meaning of individual phrases ). In other words, according to this point of view, the real process of understanding a detailed speech message does not coincide with the order in which information arrives and in which the listener receives first individual words (lexico-phonological level), and then whole phrases (syntactic level). This position is taken by such linguists as Rommetveit (1968, 1974), Fillmore (1972), McCauley (1972), Lakoff (1972), Wurtch (1974, 1975).

In other words, according to this point of view, the real process of understanding a detailed speech message does not coincide with the order in which information arrives and in which the listener receives first individual words (lexico-phonological level), and then whole phrases (syntactic level). This position is taken by such linguists as Rommetveit (1968, 1974), Fillmore (1972), McCauley (1972), Lakoff (1972), Wurtch (1974, 1975).

These authors showed that the process of understanding a message (for example, expressed in a certain text) is complex and that it requires various processes, some of which are associated with the perception of the meaning of words, some with decoding the syntactic rules of their combination. Already at the very first stages of perception of the message, hypotheses or assumptions (pre-suppositions) about the meaning of the message arise, so that the search for meaning is central to the process of understanding, leading to a choice from a number of emerging alternatives. nine0005

nine0005

The listener (or reader) never sets out to understand individual words or isolated phrases; both of these processes - the understanding of individual words or phrases (which are especially pronounced when perceiving information that is given in a foreign, poorly known language) - play the role of subordinate, auxiliary operations and only in some cases turn into specially conscious actions.

The main process that characterizes the act of understanding is the attempt to decipher the meaning of the entire message, that which creates its general coherence (external coherence, according to Wertch) or its internal meaning and gives the message depth, or "subtext" (internal coherence). These attempts are always aimed at searching for the context of the perceived statement (sometimes verbal, "synsemantic"; sometimes extra-verbal, situational), without which neither understanding of the whole text nor a correct assessment of its constituent elements is possible. That is why the above authors, who believe that there are no elements of the statement free from "context" (context fgee), highlight the process of searching for and forming appropriate hypotheses or assumptions (pre-suppositions) that determine the specific meanings of words or phrases, included in the speech utterance. nine0005

nine0005

The need to take into account the listener's "strategy" associated with this "pre-supposition" and proceed from it is, according to a number of authors (Rommetveit, 1968; Halliday, 1970; Fillmore, 1972; McCawley, 1972; Lakoff , 1972; Wortch, 1974, 1975), the main starting point for studying the mechanism of decoding an incoming message.

Thus, the decoding of a speech message is considered by modern linguistics as an active process in nature and complex in composition.

The second condition, absolutely necessary for understanding a speech message, is the knowledge of the basic, basic semantic or deep syntactic structures that underlie each component of the utterance and express known emotional or logical systems of relations. As we have shown above, this condition appears especially clearly in cases where deep syntactic structures diverge from external, surface structures; then an essential link in the understanding of these structures is their transformation into simpler and more accessible constructions. nine0005

nine0005

Considering this problem, many authors (Miller, 1970; et al.) pointed out that a complete understanding of each component of a message (phrase) can only be ensured by moving from surface grammatical structures to underlying basic semantic or deep ones.

This group of psychologists and linguists, proceeding from the notion that along with the "surface structures of language" there are also "deep structures", makes a significant contribution to the problem of understanding the speech message. nine0005

An important contribution to this problem was also made by L. S. Vygotsky (1934), who pointed out the decisive role of the process of transition from the external structure of the proposed text to the "subtext" or meaning contained in the speech message.

It is not enough to understand the immediate meaning of the message. It is necessary to highlight the inner meaning behind these meanings. In other words, a complex process of transition from "text" to "subtext" is necessary, i. e., to highlighting what exactly is the central inner meaning of the message, so that after that the motives behind the actions of the persons described in the text become clear. nine0005

e., to highlighting what exactly is the central inner meaning of the message, so that after that the motives behind the actions of the persons described in the text become clear. nine0005

This point can be easily illustrated with one example. In "Woe from Wit" by A. S. Griboedov, Chatsky's last exclamation "Carriage to me, carriage!" has a relatively simple meaning - a request to submit a carriage in which Chatsky could leave from the party. However, the meaning (or subtext) of this demand is much deeper: it lies in Chatsky's attitude towards the society with which he breaks.

Thus, the inner meaning of an utterance may diverge from its outer meaning, and the task of fully understanding the meaning of the utterance or its "subtext" consists precisely in not being limited to revealing only the outer meaning of the message, but also in abstracting from it and from the superficial text go to the deep subtext, from meaning to meaning, and then to the motive underlying this message. nine0005

nine0005

It is this provision that determines the fact that the text can be understood or "read" with different depths; the depth of "reading" the text can distinguish different people from each other to a much greater extent than the completeness of perception of surface meaning.

This proposition about the importance of the transition from the external meaning of the text to its deep meaning is well known to writers, actors, directors, and undoubtedly, the analysis of this process should occupy a significant place in psychology. Analysis of the transition from understanding the external meaning of the message to understanding the "subtext", the transition from the meaning to the internal meaning of the message is one of the most important (although the least developed) sections of the psychology of cognitive processes. nine0005

***

Let's move on to a sequential analysis of the conditions that are necessary for understanding the received message and the forms in which it flows. It is known that each speech message, perceived by the listener or perceived by the reader, begins with the perception of individual words, then proceeds to the perception of individual phrases, after which, finally, it proceeds to the perception of the whole text, followed by the allocation of its general meaning. This sequence, however, should be understood only as a logical sequence, but, as already mentioned, this does not mean at all that the actual understanding of the text proceeds in this way and consists in a sequential transition from word to phrase, from phrase to text. nine0005

It is known that each speech message, perceived by the listener or perceived by the reader, begins with the perception of individual words, then proceeds to the perception of individual phrases, after which, finally, it proceeds to the perception of the whole text, followed by the allocation of its general meaning. This sequence, however, should be understood only as a logical sequence, but, as already mentioned, this does not mean at all that the actual understanding of the text proceeds in this way and consists in a sequential transition from word to phrase, from phrase to text. nine0005

The process of decoding the meaning, and then understanding the meaning of the text, always takes place in a certain context, simultaneously with the perception of entire semantic passages, sometimes even understanding a single word actually follows the perception of entire semantic passages, and the context in which the word stands reveals it meaning. This fact indicates that the logical sequence "word-phrase-text-subtext" should not be understood as a chain of real psychological processes unfolding in time. nine0005

nine0005

Let's move on to the analysis of the constituent elements of the process of understanding the text, taking as a basis the logical sequence of its constituent parts that we have just mentioned.

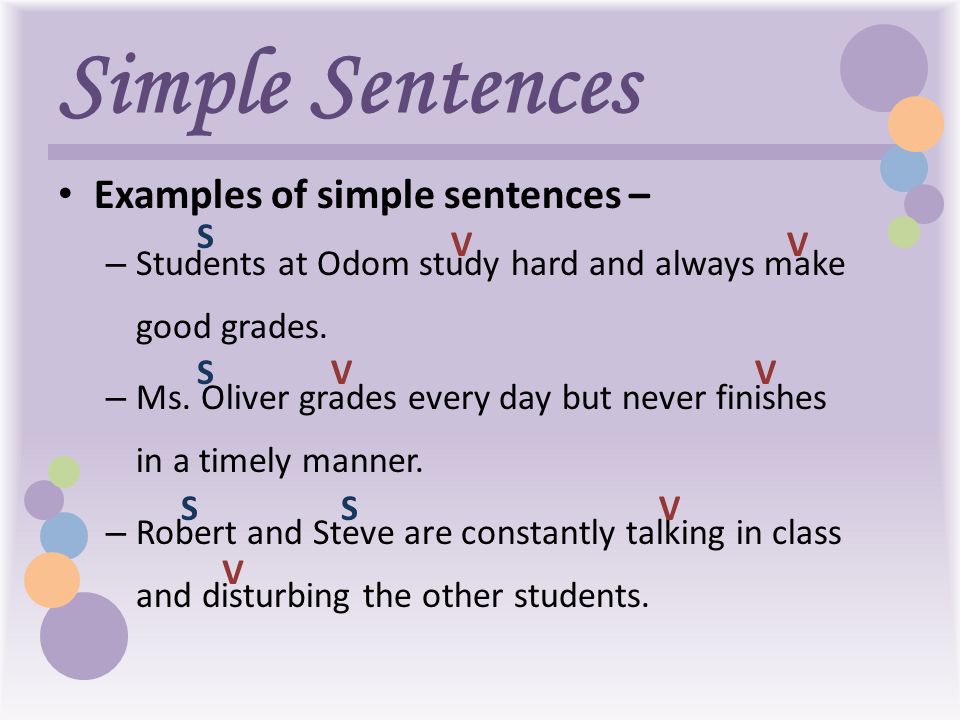

Understanding words

Understanding the meaning of the individual words that make up a message is the initial and, it would seem, the simplest element of decoding a speech message.

However, the very understanding of the meaning of a word, and even more so of the specific individual meaning with which this word is used in each given case, is a complex psychological process. The complexity of this process is due to the following circumstances. nine0005

It is known that each word is homonymous, that is, it has many meanings and, moreover, many meanings. Therefore, both to establish its subject relatedness, and to highlight the meaning of a word, each time there must be a process of choosing the meaning of a word from a number of possible ones, which is determined primarily by the context in which the corresponding word is included.

The fact of homonymy of words is by no means limited to cases of open homonymy, when the word "scythe" can mean an agricultural tool, a shallow in the sea or a girl's hairstyle, and the word "key" can mean a device that opens a door, or a source. The meaning of such words is completely determined by the context ("The girl braided a long braid", "I need a sharp braid to mow this meadow", etc.). nine0005

There is, however, a hidden homonymy: this fact is easy to see when analyzing the following examples. Thus, the word "pen" has a plural meaning: a writing instrument, a door handle, a chair handle, a child's pen, etc. The word "battle" can mean an episode of a war, or a battle of dishes, or a clock. The same can be said about adjectives. The word "cool" can be related to the weather or to an emotional attitude, the word "sharp" - to a needle, discussion, etc.

The same homonymy takes place in verbs. So, "raise" can mean "pick up an object from the floor", "raise your hands up", "raise a question", etc. ; "divide" can express both the separation of one part from another ("divide into two parts"), and union, agreement ("I share the opinion of this person"). The same homonymy can finally be observed in official words. So the preposition "in" has completely different meanings in the context: "in the forest", "in thought", "in a frenzy", etc.; the preposition "on" does not retain the same meaning in the constructions "on the table", "by ear", "climb each other", etc.

; "divide" can express both the separation of one part from another ("divide into two parts"), and union, agreement ("I share the opinion of this person"). The same homonymy can finally be observed in official words. So the preposition "in" has completely different meanings in the context: "in the forest", "in thought", "in a frenzy", etc.; the preposition "on" does not retain the same meaning in the constructions "on the table", "by ear", "climb each other", etc.

It is quite obvious that in order to understand each statement, the act of choosing the necessary, adequate meaning of the word from many alternatives is necessary, which is also ensured by introducing the word into the appropriate context.

However, the process of understanding a word is not determined only by the choice of the desired meaning from many possible alternatives. A word can have different meanings depending on the general context in which this word is given. For example, the word "spot" has a completely different meaning in different contexts: "spot on the Sun", "oil stain on a suit", "spot on reputation", etc. ; also the word "old age": "honorable old age", "sickly old age", "degradation from old age", etc. Therefore, here, for the perception of the text, it is not enough to know the stable subject relatedness of words and their stable meaning: it is necessary to choose the right meaning each time and, finally, the necessary meaning from a whole range of emerging alternatives, which is primarily determined by both the practical (“situational”) and speech contexts. nine0005

; also the word "old age": "honorable old age", "sickly old age", "degradation from old age", etc. Therefore, here, for the perception of the text, it is not enough to know the stable subject relatedness of words and their stable meaning: it is necessary to choose the right meaning each time and, finally, the necessary meaning from a whole range of emerging alternatives, which is primarily determined by both the practical (“situational”) and speech contexts. nine0005

For a complete psychological analysis of the process of understanding words as constituent elements of an utterance, it is necessary to take into account that there are also different semantic levels of the meaning of words, and that a person perceiving a text must each time choose an adequate level of the meaning of a word, which itself can be mobile. The choice of the desired level of meaning of words is also entirely determined by the context in which the word is located. So, for example, in the context of cooking, the word "charcoal" means a kindling agent; in the context of a chemical treatise, "coal" refers to a complex chemical substance having a specific structure. The word "net" in the context of fishing means a device for catching fish; in a scientific context, it means a "system of connections" ("neural network", "network of relations"), etc. Inadequate perception of the meaning of words or at least one word will lead to a misunderstanding of the entire text. Adequate understanding also presupposes the choice of the appropriate level of the word's meaning. nine0005

The word "net" in the context of fishing means a device for catching fish; in a scientific context, it means a "system of connections" ("neural network", "network of relations"), etc. Inadequate perception of the meaning of words or at least one word will lead to a misunderstanding of the entire text. Adequate understanding also presupposes the choice of the appropriate level of the word's meaning. nine0005

We have already mentioned that in some forms of mental illness (for example, in schizophrenia), the impairment of the ability to choose exactly the meaning of the word that corresponds to the situation is the main symptom of the disease and the main obstacle to an adequate understanding of the information reaching the subject.

From what has been said it follows that it would be the greatest mistake to think that words have the same, always the same meaning. The meaning of the word is multi-valued, and for its understanding it is necessary to choose the subject relatedness, the specific meaning and meaning of the given word from many alternatives. This choice can only be made taking into account both the context in which the word is given and the situation in which the message is made. This semantic choice of the adequate meaning of words is a complex psychological process, the study of which can reveal the basic mechanisms that determine the understanding or decoding of the received message. nine0005

This choice can only be made taking into account both the context in which the word is given and the situation in which the message is made. This semantic choice of the adequate meaning of words is a complex psychological process, the study of which can reveal the basic mechanisms that determine the understanding or decoding of the received message. nine0005

Conditions for understanding the meaning of words

The process of choosing the desired meaning of words from a number of possible alternatives is determined by a number of conditions. Let's take a closer look at these conditions.

The first condition affecting the adequate choice of the meaning of a word is the frequency of the given word in the language, which, in turn, is determined by the inclusion of this word in human practice. So, if the word "raise" most often denotes the act of lifting an object from the floor and much less often has the allegorical meaning of "raising a question", then the first meaning of the word is much more likely than the second, and, conversely, when perceiving the second meaning of the word, an initial abstraction from the usual, most common meaning. nine0005

nine0005

It is this unequal frequency with which different meanings of words occur that determines the difficulties that arise in understanding words in people with different professional experience. If for a doctor the word "spleen" is more familiar and has a certain meaning, and the word "drake" is rarely used by him, then it becomes possible to confuse these words (especially outside the speech context). On the contrary, for the poultry breeder, when perceiving the word "spleen", it becomes necessary to abstract from the more familiar meaning of the word "drake". nine0005

The habitual meaning of words can serve as a hindrance for a student of a foreign language, when supposedly familiar, corresponding to the practical experience of a person and frequently occurring words are perceived by him incorrectly. An example is the case when one person who settled in America for a long time perceived the combination of the words "Molted coffee" as "ground coffee" and only later found out that "Molted" has nothing to do with the usual meaning of "ground", but denotes a company producing coffee.

So, for example, a patient with impaired speech zones of the left hemisphere, determining the meaning of the word "wood louse" (low-frequency, unfamiliar to him), decided that it means "wet weather" by analogy with "thick mud" (Luriya, 1947, 1966, 1975; and etc.). Erroneous semantization of unfamiliar words is also possible in a healthy person. Such an erroneous definition of the meaning of unfamiliar words by analogy with more frequently encountered and familiar words is an essential feature of the perception of a complex text in which special terms or insufficiently familiar words appear. nine0005

The second and, perhaps, the main condition that determines the choice of the desired meaning of the word is the speech context.

This factor is especially pronounced when understanding open homonyms. Thus, the word "pipe" in the context of an orchestra undoubtedly actualizes the meaning of a musical instrument, while the same word in the context of a house description is inevitably perceived as denoting a chimney.

The same takes place in the understanding of hidden homonyms. The question of how the word "pen" is to be understood - as a writing instrument, or as a child's handle, or as a chair handle - depends on the context in which the word is used. In all cases, understanding the meaning of a word is by no means an immediate act, and the choice of the meaning of a word from many alternatives depends both on the frequency with which this meaning is used in the language and on the speech context. nine0005

A special case is the process of understanding the meaning of words by deaf-mutes. In these cases, the meanings of words are not formed in the process of live speech communication, in the context of which a healthy child learns the variability of the meanings of words; a deaf-mute child learns individual words in a different way, and if the word "raise" was given to him in the meaning of "bend down and take some object from the floor", then understanding the same word in the context of "raise your hand" turns out to be very difficult for him until he it will not be explained that the word can be used in another sense. nine0005

nine0005

The problem of understanding the meaning of words by deaf-mutes has been elaborated in Soviet literature by many researchers (Morozova, 1947; Korovin, 1950; Boskis 1963).

A similar situation takes place in those cases when learning a foreign language does not begin with the assimilation of contextual speech, but with learning the dictionary meaning of individual words. This way of acquiring a language inevitably leads to a number of difficulties, which are largely eliminated if the method of teaching a language is changed and proceeds from the speech context and only secondarily refers to the dictionary meaning of isolated words. The psychology of foreign language acquisition is a special, well-developed section of psychological science, and we will not dwell on it in more detail. nine0005

Thus, the process of understanding the meaning of a word is always the choice of meaning from many possible ones. It is carried out by analyzing the relationship that the word enters into with the general context, and overcoming the inadequate direct understanding of the word associated with the sound of the word, with the frequency of using one or another meaning, etc.