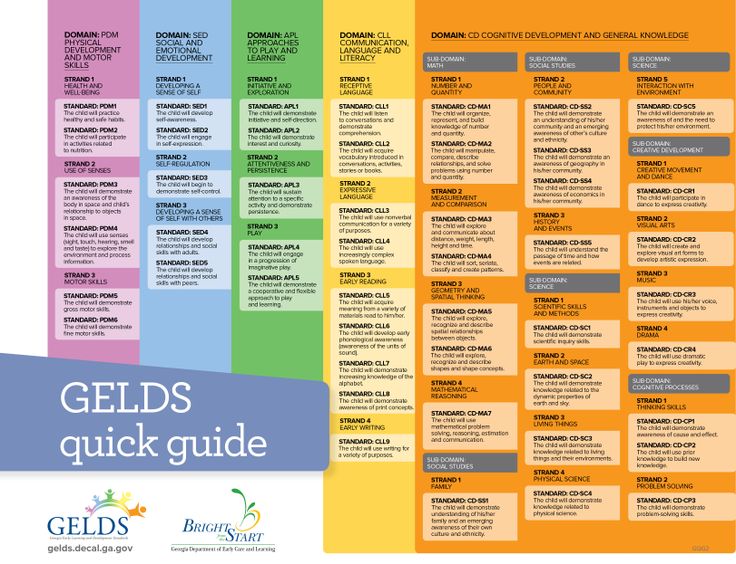

Phonological awareness development

Phonological (Sound) Awareness Development Chart

< Back to Child Development Charts

Phonological Awareness is the knowledge of sounds (i.e. the sounds that letters make) and how they go together to make words.

Note: Each stage of development assumes that the preceding stages have been successfully achieved.

How to use this chart: Review the skills demonstrated by the child up to their current age. If you notice skills that have not been met below their current age contact Kid Sense Child Development on 1800 KIDSENSE (1800 543 736).

| Age | Developmental milestones | Possible implications if milestones not achieved |

| 0-2 years |

|

|

| 2-3 years |

|

|

| 3-4 years |

|

|

| 4-5 years |

|

|

| 5-6 years |

|

|

| 6-7 years |

|

|

| 7-8 years |

|

|

This chart was designed to serve as a functional screening of developmental skills per age group. It does not constitute an assessment nor reflect strictly standardised research.

It does not constitute an assessment nor reflect strictly standardised research.

The information in this chart was compiled over many years from a variety of sources. This information was then further shaped by years of clinical practice as well as therapeutic consultation with child care, pre-school and school teachers in South Australia about the developmental skills necessary for children to meet the demands of these educational environments. In more recent years, it has been further modified by the need for children and their teachers to meet the functional Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) requirements that are not always congruent with standardised research.

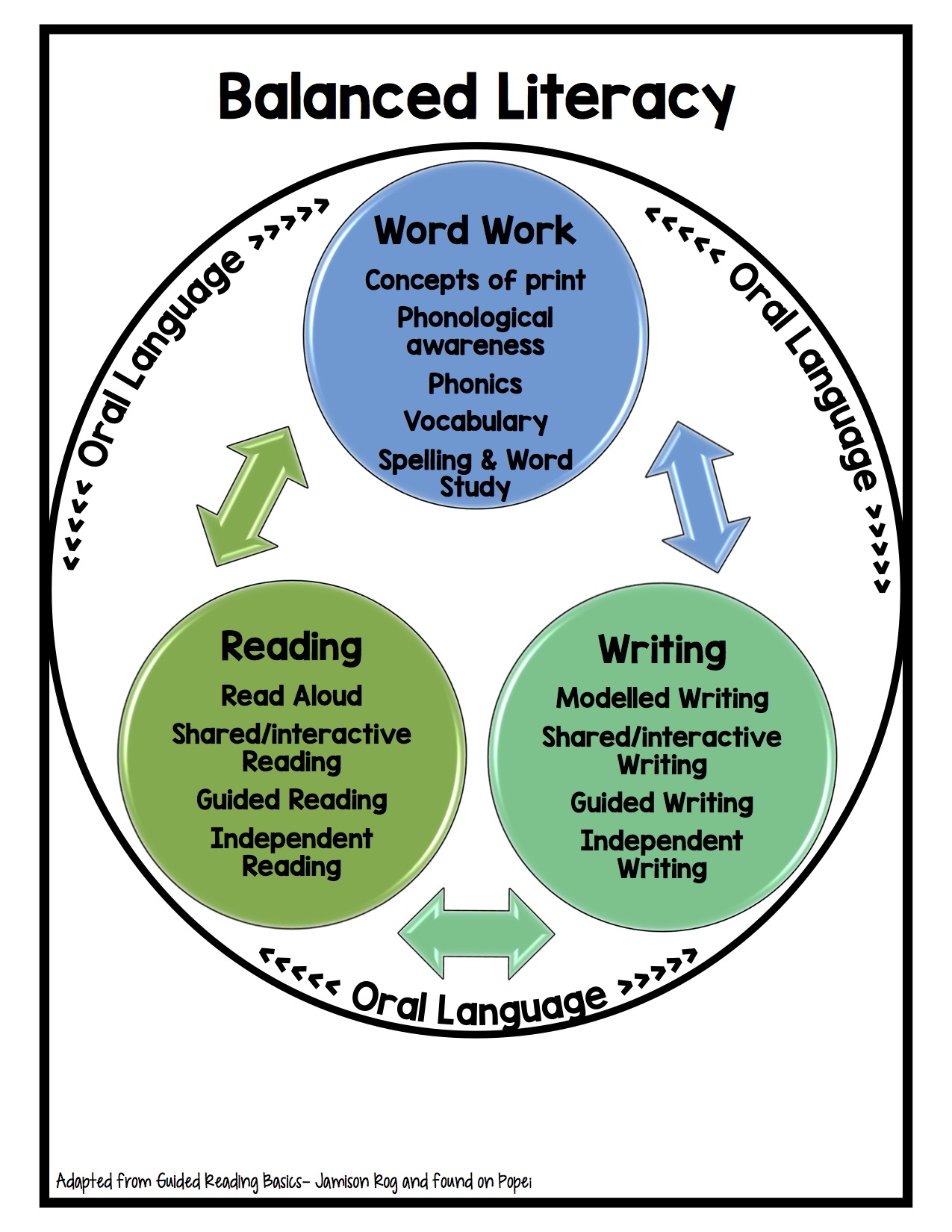

Phonological awareness (emergent literacy)

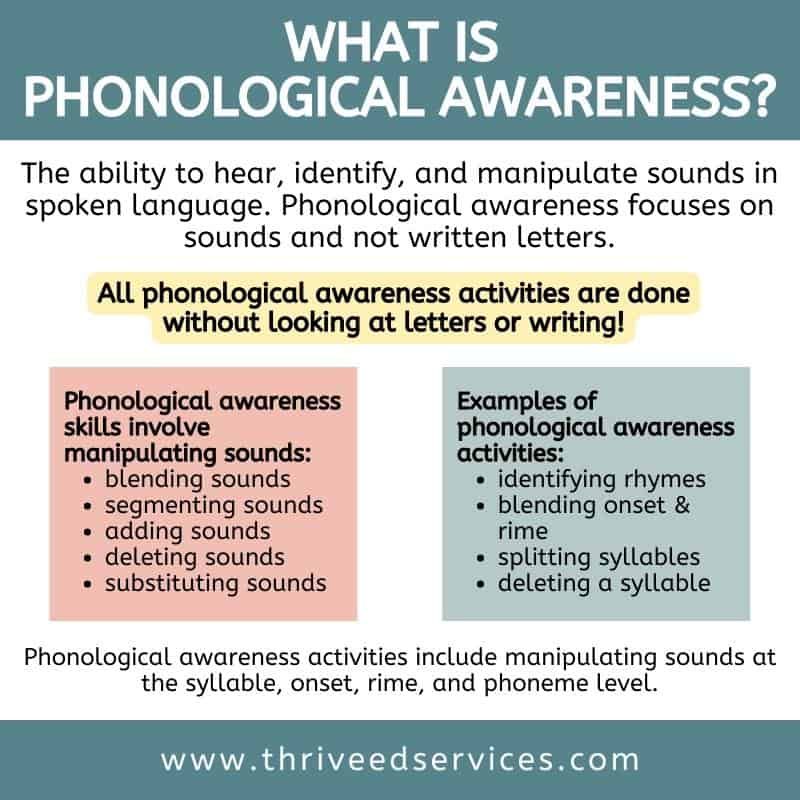

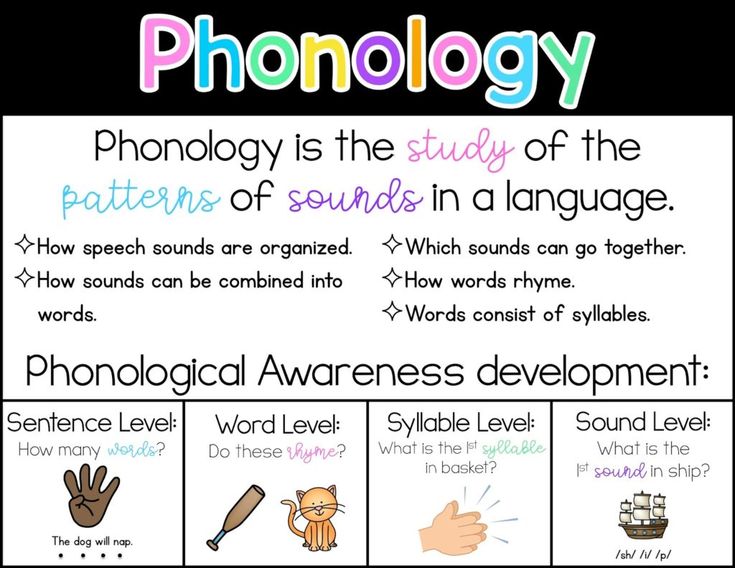

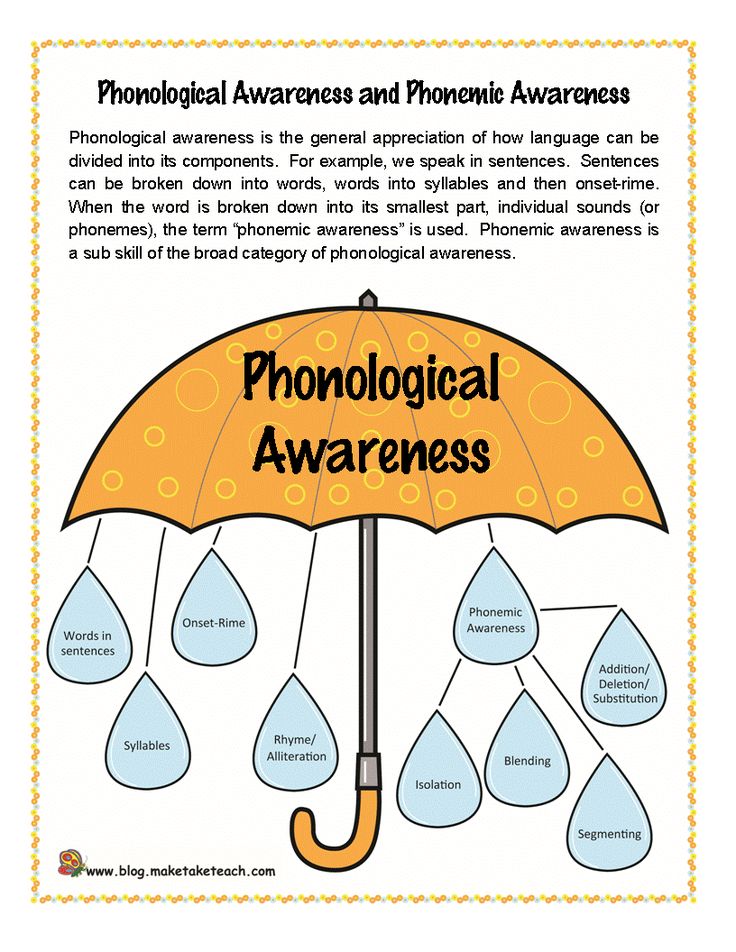

Phonological awareness is children's awareness of how sounds are put together to form words.

It includes children’s ability to recognise:

- syllables (for example pla.ty.pus)

- rhymes (for example rain/Jane; pouring/snoring)

- sounds at the start/end of words (for example cup/kit, drink/stuck)

- sounds within words (for example starch —> s t arch)

Phonological awareness is an important set of skills to develop throughout early childhood and primary school. It is strongly linked to later reading and spelling success.

It is strongly linked to later reading and spelling success.

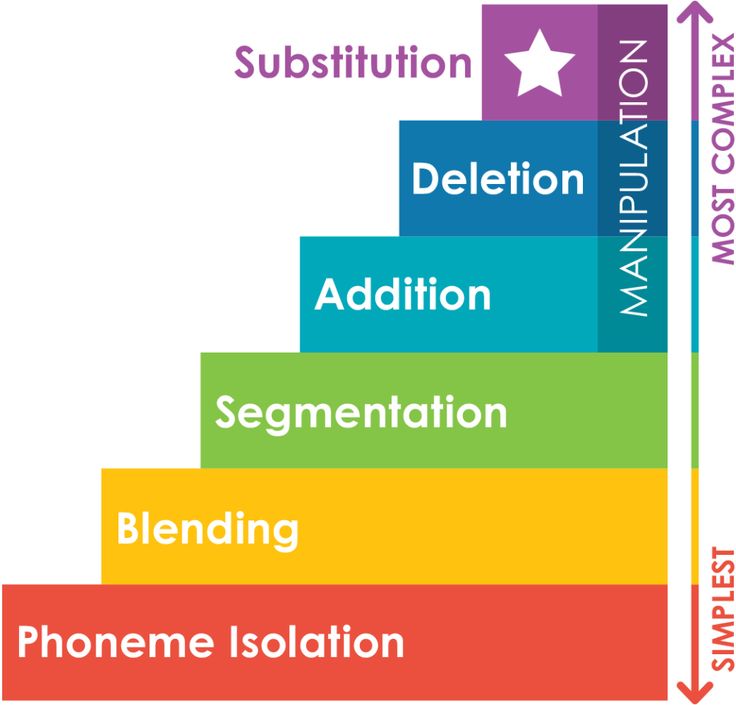

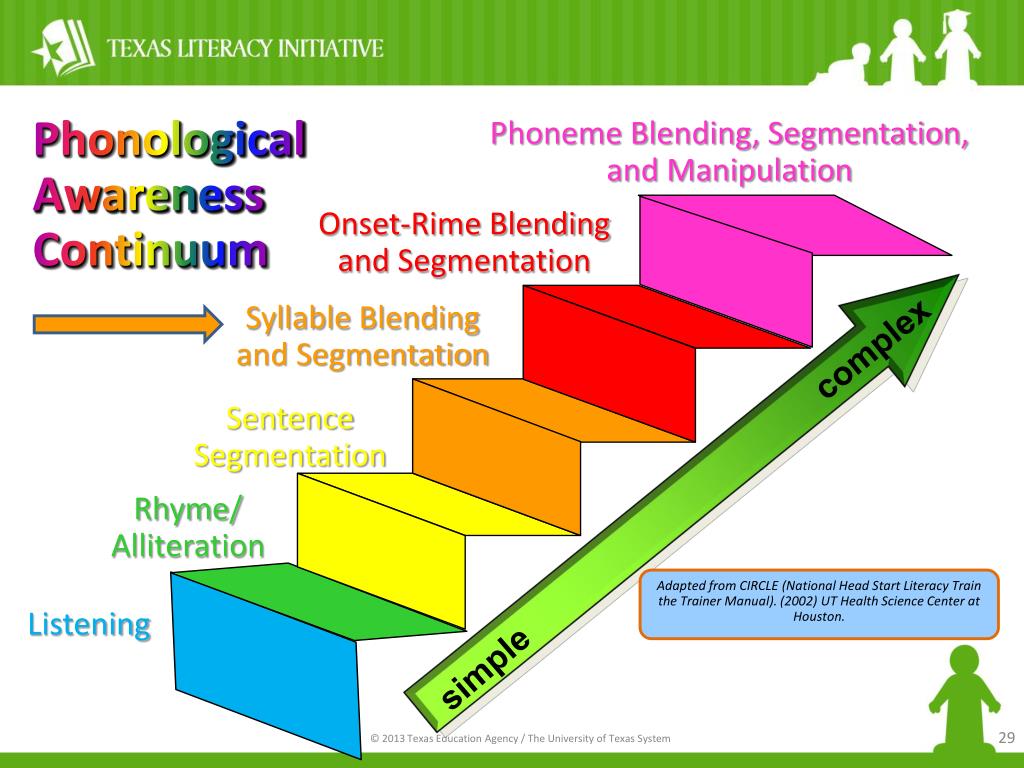

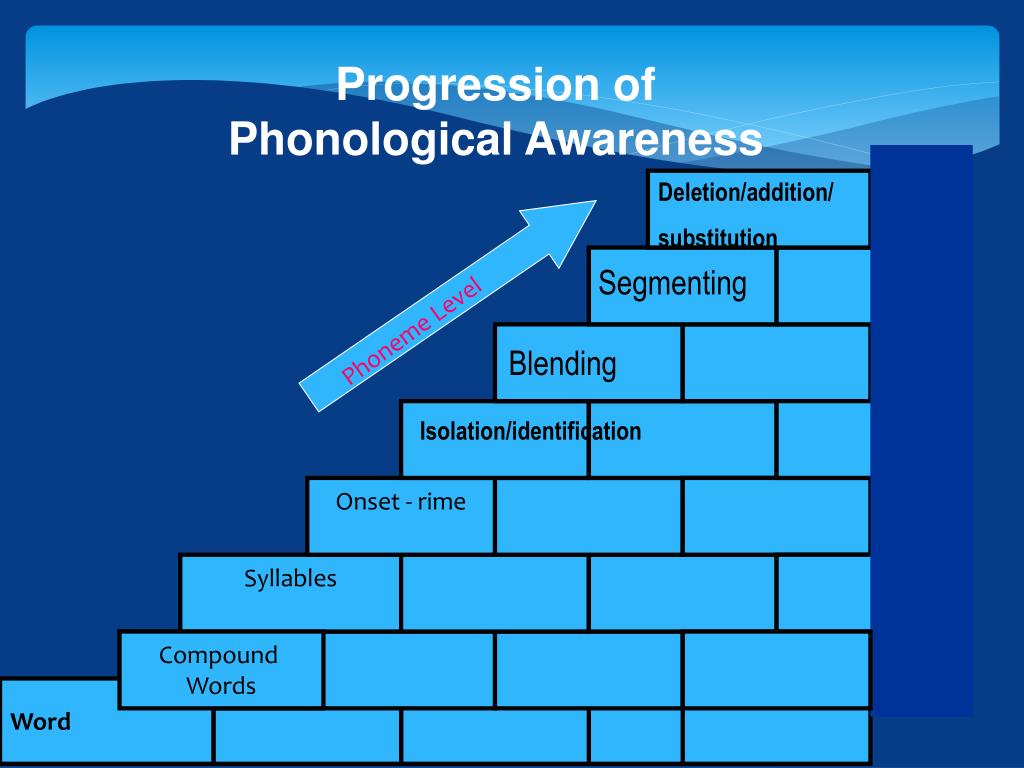

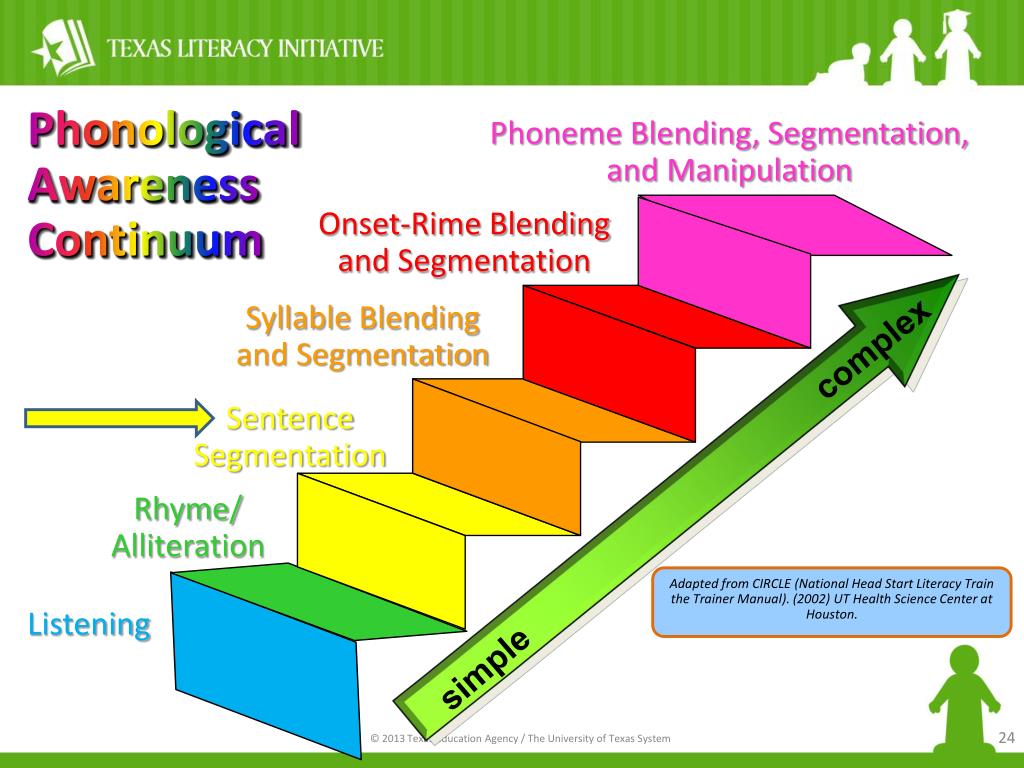

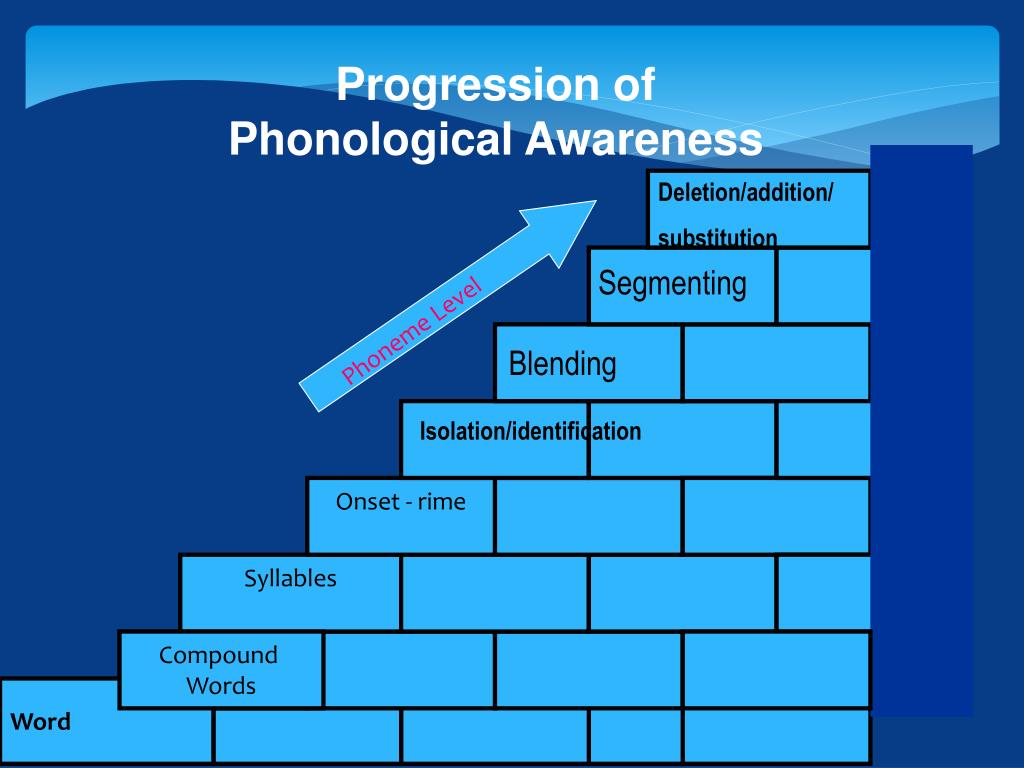

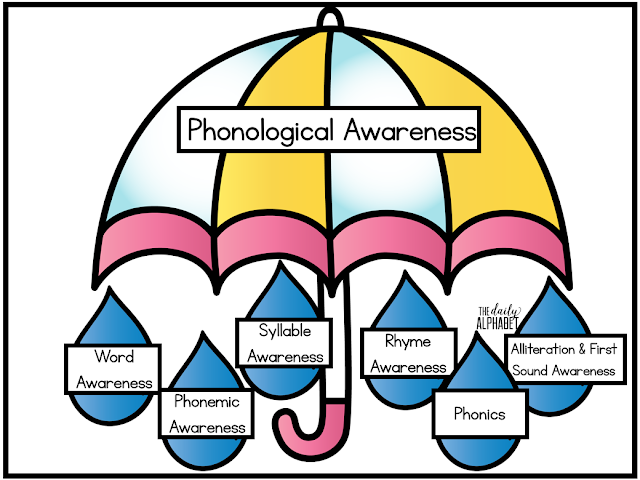

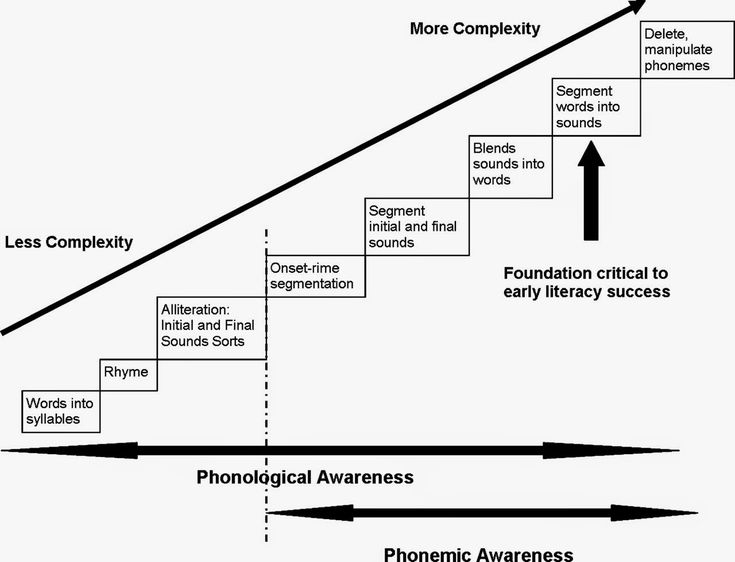

We can think about phonological awareness as a sequence from basic phonological awareness skills, to more complex ones.

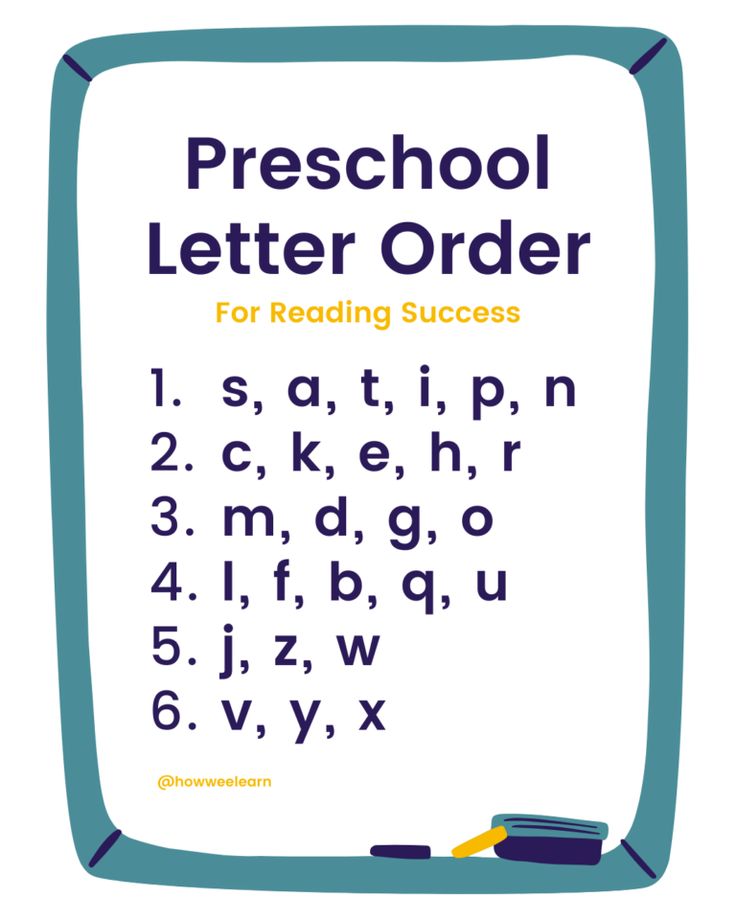

See the Phonological Awareness: Staircase to success diagram.

Important note: Most children start school with an awareness of syllables, rhyme, and alliteration, but are not expected to have attained competency in other phonological/phonemic skills (for example blending, breaking words up, playing with sounds). These later phonological awareness skills can be targeted to extend children who have a strong interest in sounds and words.

When working on phonological awareness with early communicators and early language users (birth – 36 months), the relevant phonological awareness skills are syllables and rhymes.

With older ages, educators may introduce more complex phonological awareness skills (for example alliteration, onset/rime), but the focus of phonological awareness experiences should be informed by current assessment of each child’s learning.

The awareness of the sounds that make up words is critical to being able to blend sounds together for later reading, and segmenting words into sounds for later spelling.

Educators can introduce these concepts to young children through:

- songs

- rhymes and games

- shared book reading

- collaborative emergent writing experiences (for example drawing with annotation).

We can also explicitly discuss phonological awareness concepts by explaining what syllables, rhymes, and sounds are.

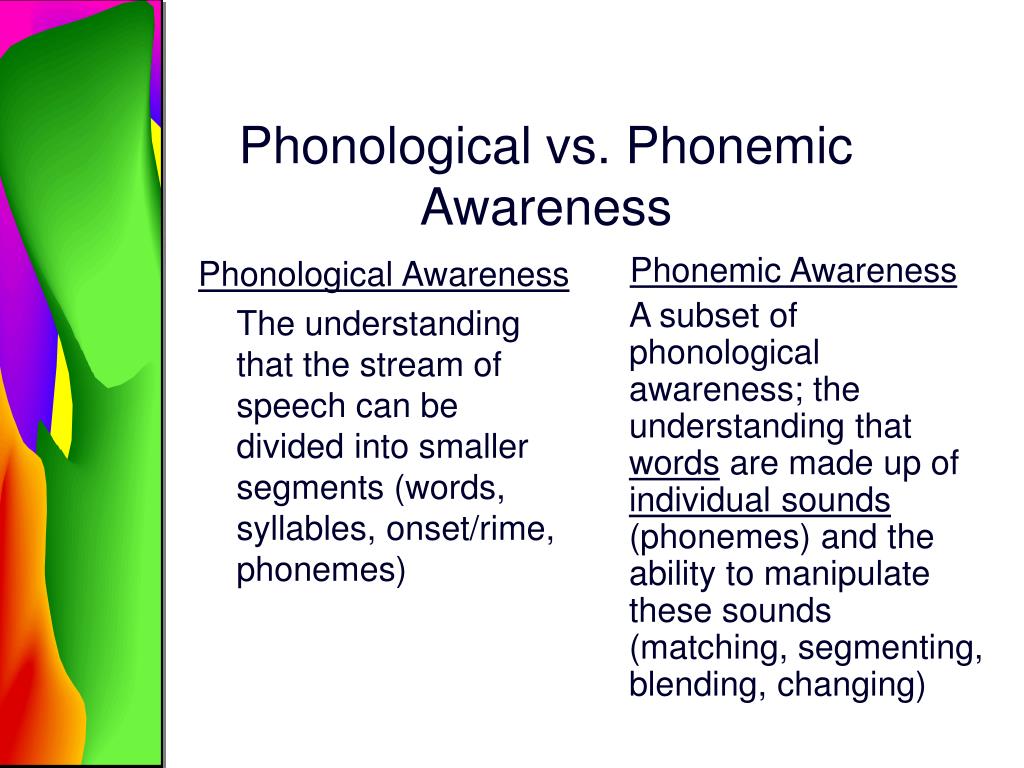

Phonemic awareness is the phoneme (“speech sound”) part of this skill and involves children blending, segmenting, and playing with sounds to make new words.

Note: You can do experiences for phonological awareness without using any written words. It is about the sounds that the words make, not about the letters we use to spell them.

The following ages and stages are a guide that reflects broad developmental norms, but doesn’t limit the expectations of every child . VEYLDF practice principle: high expectations for every child goes into further detail.

VEYLDF practice principle: high expectations for every child goes into further detail.

It is always important to understand children’s development as a continuum of growth, irrespective of their age.

Early communicators (birth - 18 months):

- enjoy book reading

- enjoy nursery rhymes and songs

- may attempt to sing or chant rhymes/songs.

Early language users (12 - 36 months):

- start to hear gaps between words in sentences

- showing interest in syllables and rhymes.

Language and emergent literacy learners (30 - 60 months):

- start to break up words into syllables (for example clapping syllables)

- start to recognise/produce rhymes

- from 36 months: start to recognise words with the same initial sound

- from 36 months: start to break words up into onset and rime (sun= s+un).

English is an alphabetic language. We only have 26 letters, but there are actually 44 speech sounds (phonemes). This includes 20 vowel sounds and 24 consonant sounds. These sounds form part of the phonology of English.

This includes 20 vowel sounds and 24 consonant sounds. These sounds form part of the phonology of English.

- 44 Speech Sounds of English (docx - 224.96kb)

- 44 Speech Sounds of English (docx - 224.92kb)

- 44 Speech Sounds of English (pdf - 546.72kb)

You can learn how these sounds (phonemes) map onto letter patterns (graphemes) in the phonics section.

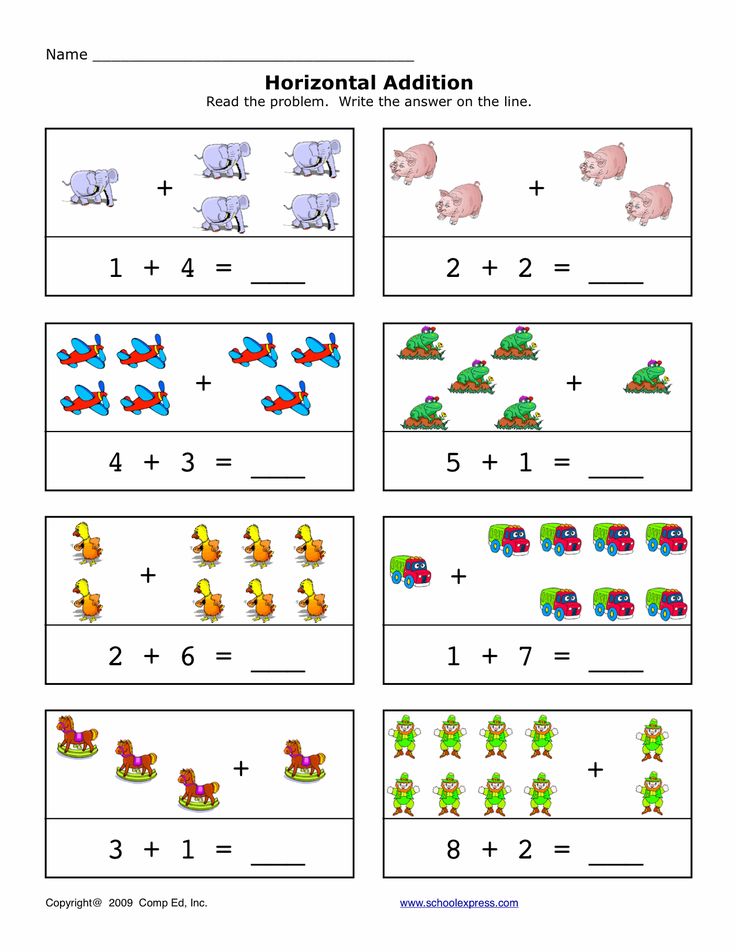

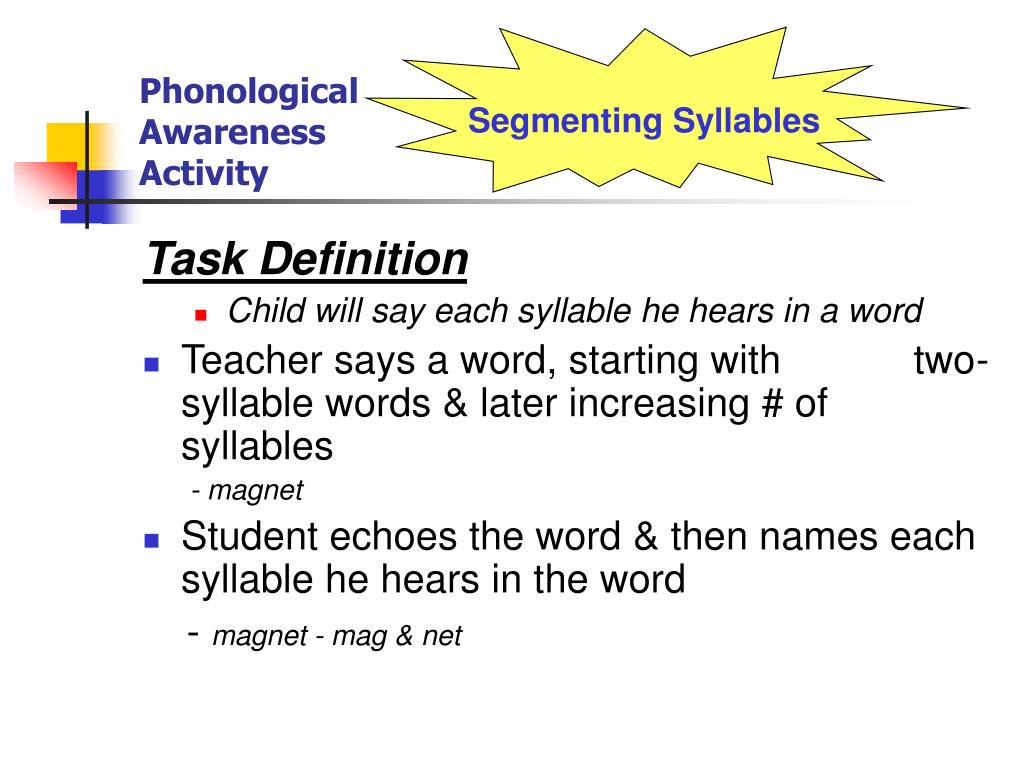

Syllable awareness involves activities like counting, tapping, blending or segmenting syllables.

Every word can be broken down into syllables. For example, helicopter —>he.li.cop.ter (4 syllables).

Compound words (for example doghouse, footpath, lifetime) are words that combine two separate words to create a new word. These are great introductions to syllable counting.

These are great introductions to syllable counting.

Syllable examples

Here are some example words, grouped by the number of syllables.

One syllable:

- jump

- thought

- cup

- range

Two syllables:

- ki.tten

- a.pple

- co.met

- sun.set

- vel.cro

- zig.zag

- fo.ssil

Three syllables:

- ma.gi.cal

- In.di.an

- vi.si.tor

- po.pu.lar

- i.ma.gine

- di.no.saur

- op.po.site

- ex.er.cise

Four syllables:

- in.te.res.ted

- e.lec.tri.cal

- es.pe.cial.ly

- im.me.di.ate

- e.qua.li.ty

- u.su.al.ly

- per.son.al.i.ty

- el.ec.tri.ci.ty

- a.ppre.ci.a.ted

- i.ma.gin.a.tion

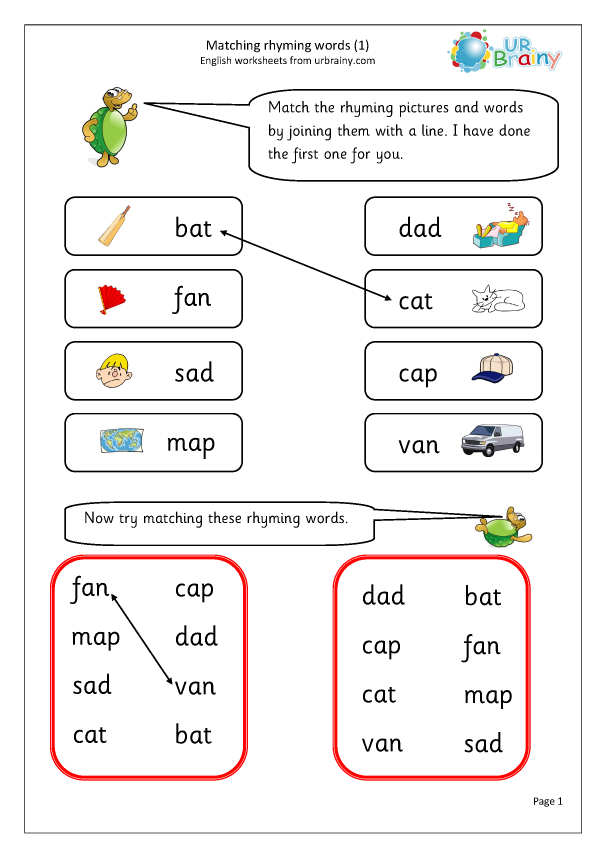

Rhyme awareness is about knowing when words do and do not rhyme. For example, children with good rhyme awareness would be able to identify the two rhyming words from this group below.

In this example, the educator and children would say the words "cat" "hat" and "tap", and children would identify "cat" and "hat" as the rhyming words.

Rhyme production is where children have to think of examples which rhyme with a given word.

For example, children would be asked to hear the rhyme in the words below:

Hand and band. What’s another word that rhymes? Photo: PixabayThrough reading books, singing songs, nursery rhymes and other games, children will be able to start thinking of their own rhymes:

- ‘Sand’ rhymes with ‘hand’ and ‘band’.

More complex rhymes

Some rhymes are more complex than others. For an extra challenge, educators can choose words with more complex rhymes. For example, the words in the second and third columns have multiple syllables in their rhymes:

One syllable rhyme (with syl.la.ble breaks):

- cop

- top

- mop

- stop

- drop

- seek

- peek

- streak

- sneak

Two syllable rhyme (with syl. la.ble breaks):

la.ble breaks):

- na.tion

- sta.tion

- dal.ma.tian

- sca.ry

- hai.ry

- fai.ry

- ca.na.ry

- nec.e.ssa.ry

Three syllable rhyme (with syl.la.ble breaks):

- a.qua.ri.an

- ve.ge.ta.ri.an

- se.ri.ous

- mys.te.ri.ous

Relevant for language and emergent literacy learners, alliteration is another early phonological awareness skill. This involves sorting words by their initial and final sounds.

Note: sorting words by sounds is not about the letters. In a phonological awareness experience, remember that the goal is for children to hear the sounds (phonemes) within words, rather than see the letter patterns (graphemes).

When sorting by initial and final sound, remember to listen to see if the words have the same sound.

Phone and physical are not sorted under the /p/ sound. Instead they both have an initial /f/ sound. Photo: PixabayAll these words start with the letter ‘s’, but sit, sun, slept have a /s/ sound, and shark and ship both have a /sh/ sound spelt with the ‘sh’. Photo: Pixabay

Instead they both have an initial /f/ sound. Photo: PixabayAll these words start with the letter ‘s’, but sit, sun, slept have a /s/ sound, and shark and ship both have a /sh/ sound spelt with the ‘sh’. Photo: PixabayAlliteration experiences can also focus on the last (final) sounds in words. You could ask children to help sort out which words end in a /t/ or a /d/ sound in this example:

Which words end with a /t/ sound, and which ones end with /d/ sound? Bat, cat, slept all end with a /t/; bad, heard, and glide all end with a /d/ sound. Photo: PixabayOnset-rime involves breaking words into their onsets (consonants before the vowels), and the rime (everything left in the word). This phonological awareness skill is more advanced and is more suitable for language and emergent literacy learners.

The onsets in these words are /d/ in down and /g/ /r/ in ‘green’. Onsets always come before the vowel of the syllable. Photo: PixabayFor example the rime "own" as in "down" could have the following onsets to make these words:

- D (onset), own (rime), down (word)

- Br (onset), own (rime), brown (word)

- Cl (onset), own (rime), clown (word)

- Dr (onset), own (rime), drown (word)

- G (onset), own (rime), gown (word)

Photo: Pixabay

Photo: PixabayNote: This phonological awareness skill is more advanced and is more suitable for children soon to transition to school.

It is also important for children to find and name the initial and final sounds of words. This is a more sophisticated version of alliteration. Instead of just sorting words by their sounds, children are encouraged to identify and name the initial or final sounds in words.

Here, children need to say what the first sound of pillow and pancake is. The answer would be the /p/ sound (as in pet). For phone and physical, the answer is /f/ (as in fan). Here, children would name the final sound in bat, cat, slept as the /t/ sound (as in tip). Photo: PixabayHere, children would name the final sound in bat, cat, slept as the /t/ sound (as in tip). For bad, heard, and glide the answer is /d/ (as in dip). Photo: Pixabay Note: This phonological awareness skill is more advanced and is more suitable for children soon to transition to school.

Blending sounds into words is a critical component of phonemic awareness. In later years, when children start to read, blending is how we “sound out words” we don’t know.

Blending sounds is a fun game to play before ever having to “read” words. It helps prepare children for the phonemic skills they need once they do start reading. For example, we can guess the word ‘cap’ by blending the sounds /c/ /a/ /p/.

Note about phoneme counters

In these sections, counters will be used to count the sounds (phonemes) in words:

These are only one way of representing sounds. Photo: Pixabay- blue counters represent consonants

- red counters represent vowels.

It is useful for teachers to use a different colour or shape to distinguish between vowels vs. consonants when children are blending and segmenting sounds.

The sounds /s/ /l/ /e/ /p/ /t/ blend together to make ‘slept’. Photo: Pixabay

Photo: PixabayYou can come up with your own system for representing consonants and vowels.

Physical counters or other small objects (for example buttons) can be used to represent phonemes. These can be useful to help children count and keep track of the number of phonemes in each word.

Counters can also be used to count sounds on paper, or on the wall, to demonstrate the number of speech sounds in each word.

Blending sounds

One of the best ways to encourage early blending is through sound games where educators sound out a word (from a book or picture), then see if the children can blend them together:

When educators sound out words, children can see if they can blend them together. . Photo: PixabayThese sound games can be played during book reading, early writing, play or other experiences. Photo: PixabayWhen educators sound out words, children can see if they can blend them together.

These sound games can be played during book reading, early writing, play or other experiences.

Note: This phonological awareness skill is more advanced and is more suitable for children soon to transition to school.

Breaking words up into their sounds is the reverse of blending sounds into words. So we can say the three sounds in ‘phone’: /f/ /o_e/ /n/:

Breaking words up into their sounds can be a fun game to play with children. It is also very beneficial for emergent writing skills. Photo: PixabayBreaking words up into their sounds can be a fun game to play with children.

It is also very beneficial for emergent writing skills.

You can work on segmenting sounds as a sound game. Educators need to first model how to break words up into sounds:

Using pictures or real objects is very important so that children know what words they are breaking up:

Can you play this sound game? What are the sounds in ‘dog’? /d/ /o/ /g/! Photo: PixabayNote: This phonological awareness skill is more advanced and is more suitable for children soon to transition to school.

Deleting or playing with sounds is the trickiest phonological awareness skill. It involves deleting or swapping the sounds in words, to make new words.

What is ‘beat’ when you take away the /t/? Bee! Photos: PixabayEducators can play these advanced sound games with older children.

Deletion example:

- "What is 'swing' without the /s/?"

- ‘wing!’

Playing with sounds (manipulation) example:

- "What happens when you take off the /g/ in 'dog' and swap it with /k/?"

- ‘dock!’

You can play these sound games with any word. You might find that children think of interesting and humorous new words!

It’s important for children to have a chance to play with words. You can talk about what is a real word and what is not.

See Phonological Awareness: Getting Started for a downloadable version.

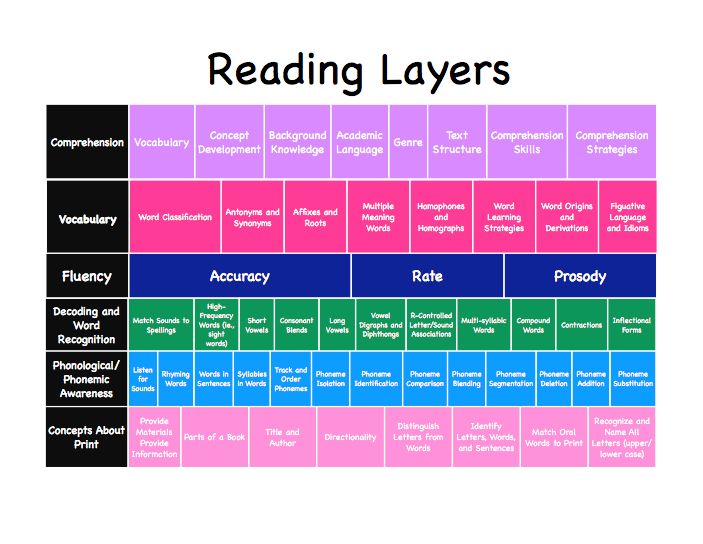

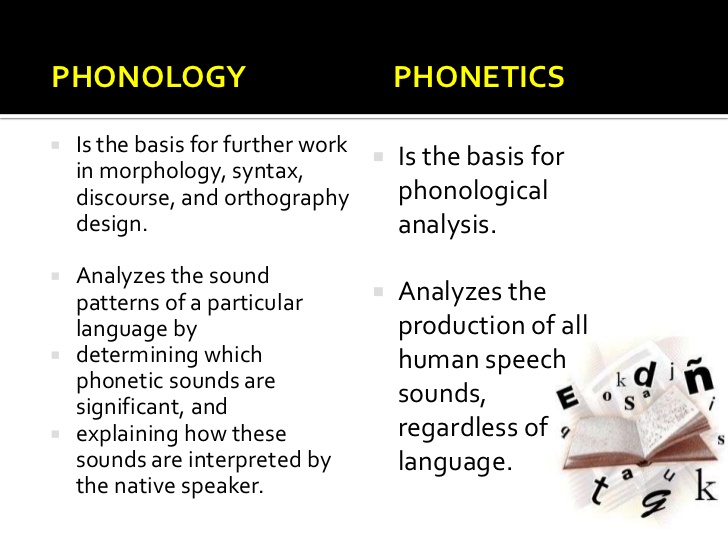

Phonological awareness is a key early competency of emergent and proficient reading and spelling. It involves an explicit awareness of how words, syllables, and individual speech sounds (phonemes) are structured.

Together with phonics, phonological awareness (in particular phonemic awareness) is essential for breaking the code of written language (Luke and Freebody, 1999).

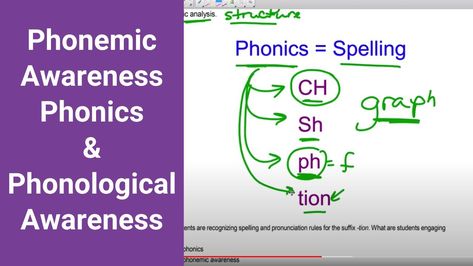

Differences between phonological awareness and phonics

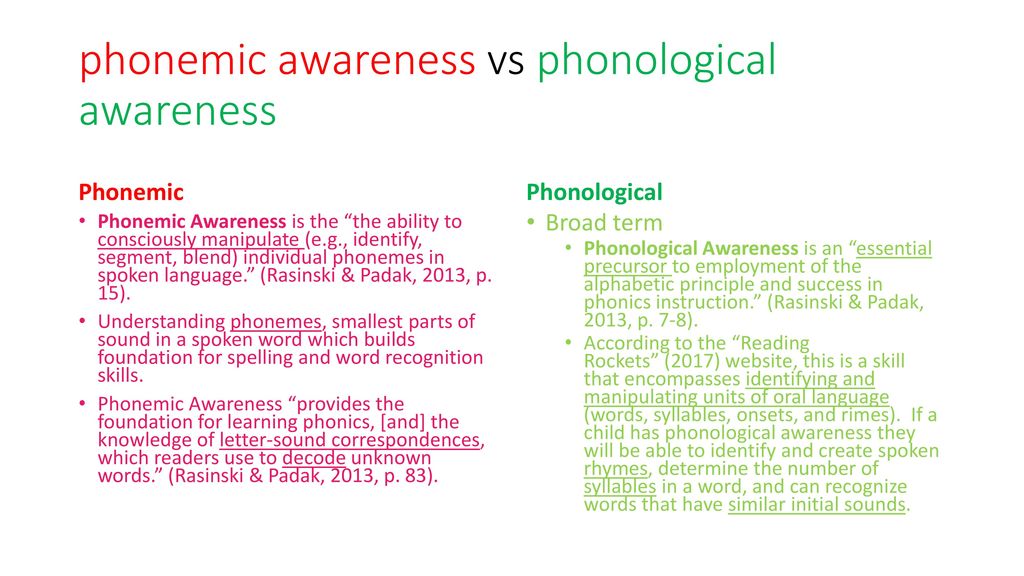

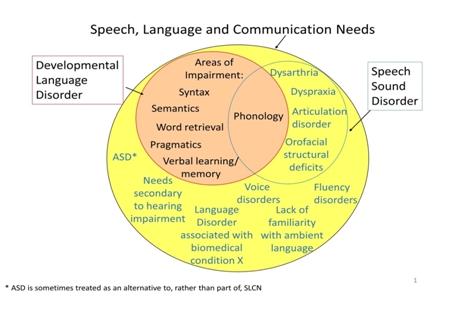

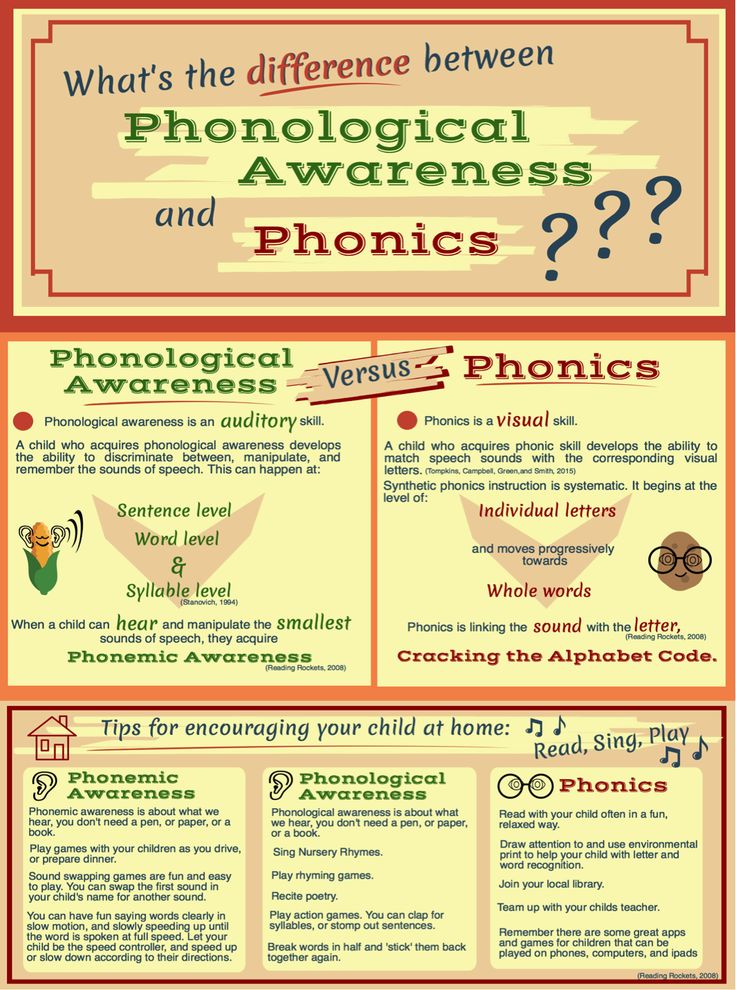

Phonological awareness includes the awareness of speech sounds, syllables, and rhymes.

Phonics is about sound-letter patterns — how speech sounds (phonemes) can map onto letter patterns (i.e. graphemes). Phonological Awareness and Phonics are therefore not the same, but these literacy foci tend to overlap.

Numerous studies support that phonological awareness is a key predictor (along with alphabet knowledge) for success with decoding the written word into speech. This research includes studies into successful phonological awareness programs in early childhood settings (Lefebvre, Trudeau, & Sutton, 2011; Milburn et al., 2015), and the Australian National Inquiry into the Teaching of Reading (Rowe et al., 2005), which supported the teaching of phonological (including phonemic) awareness as an effective approach for early reading skills.

There is also research suggesting that music may be a useful teaching tool for phonological awareness development Degé & Schwarzer, 2011).

Also, Hattie's (2009) Visible Learning, the US National Reading Panel (2000) and the UK Rose Review (2006) support phonological awareness as an important component of rich literacy programs.

Early communicators (birth - 18 months):

- nursery rhymes, songs, and poems

- shared book reading

- drawing children’s attention to the sounds of spoken language, including:

- syllables (beats)

- rhymes

- individual sounds

Early language users (12 - 36 months):

- nursery rhymes

- songs

- poems and riddles

- shared book reading

- finding patterns of syllable, rhyme, initial/final sound by:

- Matching pictures to other pictures: dog/log

- Matching objects to pictures: tap/toe

- Matching objects to actions: rope/jump

Language and emergent literacy learners (30 - 60 months):

- nursery rhymes

- songs

- poems and riddles

- shared book reading

- emergent writing experiences (drawings with annotations)

- using games to practise awareness of syllables, rhyme, initial/final sound, and individual sounds in words (see below for ideas)

- Beats in My Name: At group time, move around the circle, each child claps the syllable in their name: Lu-cy (clap, clap)

- This could also be done with claves, other forms of body percussion

- Group time rhymes with movement: stamping feet for the beat or syllable - e.

g. feet, feet, feet, feet, march-ing up and down the street

g. feet, feet, feet, feet, march-ing up and down the street - Mystery bag: fill with familiar objects, children pull out an object, name it, clap the syllables - e.g. 'lion' – li.on, 'ball' - ball, 'octopus' – oct.o.pus

- Sorting syllables: Set up a t-chart on the carpet (could use string or masking tape):

- children choose an object from around the room to bring to the carpet

- can each sort into 1-syllable or 2+ syllables

- children place their objects accordingly (hat in 1 syllable, pen.cil in 2+ syllable)

Compound words are a great way to introduce syllable counting:

- Educators can present two words separately

- Then show how they blend together

- This makes one word with two syllables

- Rhyming card games

- Sorting objects by rhyme

- Storybooks with rhyme:

- e.g. Hairy Maclary, Room on the Broom, The Gruffalo

- I have, who has?

- Children have a card/object

- They need to find the other student in the class that has a card/object that rhymes with theirs

- e.

g. the student with a frog needs to find the student with a dog

g. the student with a frog needs to find the student with a dog

- Book with song - One Elephant Went Out To Play

- Using songs with actions to highlight rhyming:

- My hands a feeling chilly, I think they're turning blue I need something to warm them up but what can I do? I can rub them, rub them, wriggle them around, I can shake them, shake them and bang them on the ground.

- Poetry reading and writing

- Looking at a poem and finding all the alliteration (this can be highlighted visually for children to look at: Concepts of Print)

- Book reading

- e.g. Fox in Socks (Dr Seuss), Hairy Maclary

- Making up own alliteration poems in a small group

- Saying tongue-twisters during group time

- Choose the first sound in your name to make a funny alliteration poem

Finding initial and final sounds:

- Sorting objects or pictures by the initial or final sounds

- Filling in the Blanks - initial or final sound of a word - this could be done with a picture or aurally

- Bingo

Blending sounds and breaking words up:

- Robot talk: use robot talk and ask the children to help blend the words the robot is saying

- Children can also be robots by breaking words up into robot talk and the other children to blend the words

- Guess-the-word game: Educator says a word’s individual sounds and children have to guess the word

- Race car blending: Children drive a car along a picture and say the sounds in that word

- Using bead bracelets to blend sounds together - or beads on a string

- Playing with magnetic letters, showing how words are put together and then broken up

- Sound boxes: Providing pictures of words, and asking children to place a counter in a box for each sound they can hear.

Deleting or playing with sounds:

- Make a New Word: Ask children to take one word and make a new one by changing a sound

- e.g. what is ‘dawn’ without the /n/? ‘Door!’

- Remember you don’t need to use letters to play these games. It’s about hearing the sounds in spoken words.

- Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework (2016)

- VEYLDF Illustrative maps

Outcome 4: learning

Children develop a range of skills and processes such as problem solving, inquiry, experimentation, hypothesising, researching and investigating:

- make predictions and generalisations about their daily activities, aspects of the natural world and environments, using patterns they generate or identify, and communicate these using mathematical language and symbols

Outcome 5: communication

Children engage with a range of texts and get meaning from these texts listen and respond to sounds and patterns in speech, stories and rhymes in context:

- sing, chant rhymes, jingles and songs

- begin to understand key literacy and numeracy concepts and processes, such as the sounds of language, letter–sound relationships, concepts of print and the ways that texts are structured.

Children begin to understand how symbols and pattern systems work:

- begin to recognise patterns and relationships and the connections between them

- listen and respond to sounds and patterns in speech, stories and rhyme use symbols in play to represent and make meaning.

For age groups: early communicators (birth - 18 months):

- Over in the meadow

For age groups: early language users (12 - 36 months):

- Phonological awareness through rhyme and stories

- Over in the meadow

- Music tree

- Hello song

For age groups: language and emergent literacy learners (30 - 60 months):

- Phonological awareness through music

- Phonological awareness through rhyme and stories

- Hop on pop

- Music tree

- Reading areas

- Bee bee bumble bee

- The sounds in my name

- Speech sounds

- Phonics

Degé, F. , & Schwarzer, G. (2011). The effect of a music program on phonological awareness in preschoolers. Frontiers in Psychology, 2 (June), 124.

, & Schwarzer, G. (2011). The effect of a music program on phonological awareness in preschoolers. Frontiers in Psychology, 2 (June), 124.

Hattie, J 2009, Visible Learning; a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement, Routledge, London.

NRP, National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Lefebvre, P., Trudeau, N., & Sutton, A. (2011). Enhancing vocabulary, print awareness and phonological awareness through shared storybook reading with low-income preschoolers. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 11(4), 453–479.

Luke, A., & Freebody, P. (1999). Further notes on the four resources model. Reading Online, 3.

Milburn, T. F., Hipfner-Boucher, K., Weitzman, E., Greenberg, J., Pelletier, J., & Girolametto, L. (2015). Effects of Coaching on Educators’ and Preschoolers’ Use of References to Print and Phonological Awareness During a Small-Group Craft/Writing Activity. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 46(2), 94.

(2015). Effects of Coaching on Educators’ and Preschoolers’ Use of References to Print and Phonological Awareness During a Small-Group Craft/Writing Activity. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 46(2), 94.

Rowe, Ken and National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy (Australia), Teaching Reading (2005).

Rose Review. Department for Education, 2010, Importance of Teaching: The Schools White Paper Executive Summary, TSO, London, England.

Schuele, C. M., and Boudreau, D. (2008). Phonological awareness intervention: Beyond the basics. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 39(1), 3-20.

Victorian State Government Department of Education and Training (2016, Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework (2016), Retrieved 3 March 2018

Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (2016) Illustrative Maps from the VEYLDF to the Victorian Curriculum F–10.Retrieved 3 March 2018.

90,000 how culture affects the perception of speech. Interview with Doctor of Philology E.F. Tarasov

Interview with Doctor of Philology E.F. Tarasov “I think, therefore I exist,” said the philosopher Rene Descartes. However, we all exist in society. Every day each of us receives a lot of various information, polar opinions, signals from the senses. And, of course, all this affects a person, his way of thinking, speech and language features. About the connection between culture, thinking, language and speech - an interview with a doctor of philological sciences, psycholinguist Evgeny Fedorovich Tarasov.

Evgeny Fedorovich Tarasov - Doctor of Philology, Professor of the Department of Linguistics and Intercultural Communications of the Russian New University.

− Evgeny Fedorovich, what does the term “psycholinguistics” describe today?

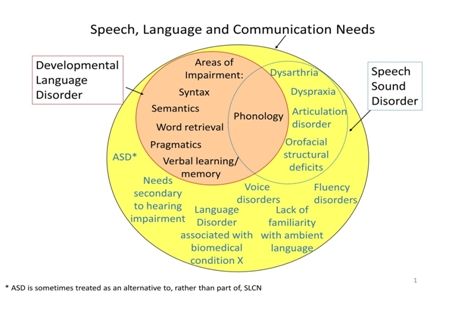

- Psycholinguistics is a scientific discipline that arose at the intersection of psychology and linguistics. Linguistics could not give an unambiguous answer to many questions. Therefore, it was necessary to combine the efforts of linguistics and psychology. For a linguist, linguistic science is a descriptive science. It only describes what linguists hear. But speech consists not only of the sound component. There are stages of psychological preparation of speech that linguistics does not take into account. Therefore, there was a need for interaction between the two disciplines.

Therefore, it was necessary to combine the efforts of linguistics and psychology. For a linguist, linguistic science is a descriptive science. It only describes what linguists hear. But speech consists not only of the sound component. There are stages of psychological preparation of speech that linguistics does not take into account. Therefore, there was a need for interaction between the two disciplines.

In 1953, a summer school was organized in the United States of America, which brought together linguists and psychologists. This is how Charles Osgood's first school of psycholinguistics arose.

However, it did not last long, because as a psychological fragment, the supporters of the school were guided by the theory of behaviorism. She had no support from psychologists. Therefore, the first school of psycholinguistics lasted until 1957.

− How did psycholinguistics develop in the future?

− In 1957, Noam Chomsky's review of Burres Skinner's book Behavior of Language was published. This event marked the end of the Osgood school and the emergence of the Miller-Chomsky school. This school lasted longer - until about the 80s.

This event marked the end of the Osgood school and the emergence of the Miller-Chomsky school. This school lasted longer - until about the 80s.

I note that psycholinguistics studies four problems: speech production - how people speak; speech perception - how people understand someone else's speech; verbal communication, that is, interaction through speech, when people cooperate with each other; and the ontogeny of language, that is, children's speech.

Neither Osgood's psycholinguistics nor Miller-Chomsky's psycholinguistics provided a satisfactory solution to these four problems. Chomsky, for example, put forward a generative theory of language description, in which, by adding to the smallest syntactic structure originally existing in the language, one more element is added and the next structure is produced. The generative way of constructing syntactic constructions has been known for a long time, but it was Chomsky who applied it in linguistics.

But there were also psychologists who suggested that a person also builds his speech based on generative grammar. If I want to say, for example: “I am writing a letter,” then, according to this hypothesis, first I form the structure “I am writing,” and then “I am writing a letter.” Or I add extra structure, like "I'm writing a letter home."

If I want to say, for example: “I am writing a letter,” then, according to this hypothesis, first I form the structure “I am writing,” and then “I am writing a letter.” Or I add extra structure, like "I'm writing a letter home."

This hypothesis has been tested for 20 years. We conducted about three hundred thousand experiments, but there were always opponents of generative psycholinguistics who set up a counter-experiment and refuted the results of opponents. The researchers concluded that the generative theory of speech production and perception is not supported. And so the psycholinguistics of Miller-Chomsky "died" around the 80s. After that, all psycholinguists began to test their own theories without looking back at the work of Chomsky.

Aleksey Nikolaevich Leontiev - Soviet psychologist, philosopher, teacher and organizer of science

Source: Interesting Facts

But it is impossible not to mention the third psycholinguistic school, which is called "The Theory of Speech Activity". This is a domestic direction of psycholinguistics, which arose back in 1966, the only school that has given satisfactory answers to all four questions of psycholinguistics, which we are very proud of. And this is a great merit not even of linguists, but of domestic psychologists who were guided by the theory of activity of Alexei Nikolaevich Leontiev. According to it, any human activity is considered according to the subject-object scheme. That is, in any activity there is a subject, an action and an object. This scheme is great for speech analysis and speech communication.

This is a domestic direction of psycholinguistics, which arose back in 1966, the only school that has given satisfactory answers to all four questions of psycholinguistics, which we are very proud of. And this is a great merit not even of linguists, but of domestic psychologists who were guided by the theory of activity of Alexei Nikolaevich Leontiev. According to it, any human activity is considered according to the subject-object scheme. That is, in any activity there is a subject, an action and an object. This scheme is great for speech analysis and speech communication.

Let's say that now I am speaking, that is, I am making verbal utterances with a specific purpose. I want my listeners or readers to share my thoughts. I influence the audience.

Thus, the psycholinguistic theory of speech activity has proposed working models of speech perception and production that are adequate enough to be used in experiments.

Among domestic linguists who can be called the forerunners of psycholinguistics, it is necessary to single out Alexander Afanasyevich Potebnya, a student of Alexander von Humboldt. Potebnya greatly advanced the understanding of the processes of verbal thinking and speaking. Also a great contribution to the development of domestic psycholinguistics was made by Ivan Alexandrovich Baudouin de Courtenay, a Soviet-Polish researcher. And Lev Vladimirovich Shcherba is considered the direct forerunner of Russian psycholinguistics.

Potebnya greatly advanced the understanding of the processes of verbal thinking and speaking. Also a great contribution to the development of domestic psycholinguistics was made by Ivan Alexandrovich Baudouin de Courtenay, a Soviet-Polish researcher. And Lev Vladimirovich Shcherba is considered the direct forerunner of Russian psycholinguistics.

Alexander Afanasyevich Potebnya - Russian and Ukrainian linguist, literary critic, philosopher

Source: Wikipedia

Today, domestic psycholinguists are guided in the psychological aspect by the theory of activity of Alexei Nikolaevich Leontiev, and in the linguistic aspect, by the activity approach of Lev Vladimirovich Shcherba. It was these scientists who formed a certain stock of knowledge, which is used in the framework of the theory of speech activity of the domestic psycholinguistic school, headed by Alexei Alekseevich Leontiev, the son of Alexei Nikolaevich Leontiev. Leontiev-son was a linguist by education and, in addition, had a good psychological preparation. Aleksey Alekseevich reviewed foreign publications, did colossal work almost independently, published several books in which he showed the positive and negative aspects of existing theories and substantiated his own - the theory of speech activity.

Aleksey Alekseevich reviewed foreign publications, did colossal work almost independently, published several books in which he showed the positive and negative aspects of existing theories and substantiated his own - the theory of speech activity.

− Is Russian theory popular in the West ?

- Because of the contradiction to all the postulates of transformational psycholinguistics of Miller-Chomsky and Osgood, this theory is not particularly popular. Despite the fact that the theory of activity of A.N. Leontiev and the cultural-historical approach of L.S. Vygotsky are considered the tomorrow of psychology, foreign scientists from the field of cognitive science are not yet ready to master the theory of activity.

However, some scientists are interested in these areas, they translate the works of Russian psycholinguists. But there are few such people. Of the domestic psycholinguists, Alexander Romanovich Luria is the most famous. Why? Because he organized the translations of the works of American psychologists into Russian. And those, in turn, translated the publications of Luria. For the most part, it is known among foreign scientists due to the fact that such an exchange existed.

Why? Because he organized the translations of the works of American psychologists into Russian. And those, in turn, translated the publications of Luria. For the most part, it is known among foreign scientists due to the fact that such an exchange existed.

- You said that the first school was founded in the 1950s. But another opinion is also widespread, according to which echoes of psycholinguistics can be found even in the 18th century.

Ivan Alexandrovich Baudouin de Courtenay - Russian linguist of Polish origin

Source: Wikipedia

− I agree with this point of view. The beginnings of psycholinguistics can be considered the work of Humboldt, who proposed to consider language as an activity. Humboldt applied the activity approach, since already in those years the theory of activity was formulated, which was developed by his outstanding contemporaries, including F.W.J. Schelling and I.G. Fichte. Therefore, of course, psycholinguistics was born on the basis of previously created works.

- There are many different opinions about the relationship between thinking and human speech. What theories are accepted by the scientific community today?

− In order to say something, a person must form a thought. Speech is thought put into a form understandable to others. This means that my thought is available to me only in introspection, in "peeping" inside. Although in this form my thought has much in common with the thoughts of other people. After all, you and I are carriers of the same culture. Our consciousness is filled with images of objects of our culture. Let's say we don't know how a Mongolian yurt is arranged, but we have an idea of how a hut looks like in a Russian village. This is a cultural item. So, the consciousness of any person is filled with images of objects of his culture. It is a prerequisite for communication and understanding between people. We can communicate based on the same mental images.

There is another way. A person can express an idea about what he observes. Then speech will be connected directly with the processes of observation and cognition. At the same time, when I look at the table, it exists in my mind as an image. That is, this is not a real table, but an image of this table. Therefore, my consciousness is individual, but at the same time culturally conditioned, and this explains the commonality of consciousness of bearers of the same culture.

A person can express an idea about what he observes. Then speech will be connected directly with the processes of observation and cognition. At the same time, when I look at the table, it exists in my mind as an image. That is, this is not a real table, but an image of this table. Therefore, my consciousness is individual, but at the same time culturally conditioned, and this explains the commonality of consciousness of bearers of the same culture.

When a person observes an object of reality, he forms it as a result of perception, which consists of the processes of influencing an object with a glance, hands, on the one hand, and the influence of the object itself on the organs of vision, touch, smell, that is, human receptors - on the other . This is how a sensory image is formed, which then turns into a perceptual one. When I see an object, I try to compare it with what I saw before. And if I have no perceptual standards, that is, there is nothing to compare the object with, then I may not recognize it.

Simply put, reality exists for me in the images of my consciousness. And if I want to share my perception with you, then I must “clothe” my own individual knowledge into knowledge common to you and me, to tell it in such a way that you understand. And this is knowledge that is associated with the language. This means that language is not consciousness, but a way of existence of consciousness in an external form.

Lev Vladimirovich Shcherba - Russian linguist, academician of the USSR Academy of Sciences, who made a great contribution to the development of psycholinguistics, lexicography and phonology

Source: Wikipedia

− A tool?

− Quite right. Experts call this linguistic consciousness. This is, of course, a metaphor. It is about the consciousness that unites all speakers of this language. F.I. Tyutchev once said: "A thought uttered is a lie." What did he mean? A person has generated some thought with the help of his individual images and wants to convey it to others, but feels that he lacks words to convey his thought. Therefore, there is always a gap between thoughts and the way they are expressed.

Therefore, there is always a gap between thoughts and the way they are expressed.

Besides, when I speak, I don't convey any thoughts, information. I only produce bodies of linguistic signs, that is, sounds. Therefore, when we hear someone else's speech, we perceive it with the help of knowledge of the language and translate it into images of our consciousness.

Now I only pronounce sounds, though organized in a certain grammatical chain. And you, using your knowledge associated with individual words, build the content of my statement, focusing on the grammatical design of the speech chain. Imagine that several people are listening to me, including a ten-year-old child. Will everyone understand me the same way?

- Not likely.

− Yes, the child will definitely misunderstand me. Why? He will rely only on his own knowledge.

When I speak, I give the listener a program to form the content of my speech. He opens up a specific thought that I wanted to express.

− But in fact, you may have completely different thoughts?

− Right. The content of my speech is constructed only by the listener. This is how the processes of production and perception of speech are described, which are directly related to each other and proceed simultaneously in oral form. The key to understanding is a common consciousness. If it does not exist, then it will be difficult for the interlocutors to understand each other.

- How do people from different cultures manage to interact with each other?

- Different nations need to work together. They interact with each other through speech and actions, objects, tools. That is, language is not the only sign and means of mutual understanding.

− So we can't equate thinking and language? Language in this case - tool?

- Language is a way of presenting the results of thinking.

− How does our speech and thinking change under the influence of digital technologies? Are there any studies in this direction?

− Yes, there is quite a lot of research on this subject. The range of questions is wide, so I will focus on a few. First of all, if you are an active Internet user, you have probably noticed that a huge number of people have stopped writing correctly. They have lost social control.

The range of questions is wide, so I will focus on a few. First of all, if you are an active Internet user, you have probably noticed that a huge number of people have stopped writing correctly. They have lost social control.

Evgeny Fedorovich Tarasov - Doctor of Philology, Professor of the Department of Linguistics and Intercultural Communications of the Russian New University

Photo: Scientific Russia / Elena Librik

Among other things, such an element as hypertext appeared in the Internet space. It takes into account all previously published texts and makes it possible to create electronic links, links, allows you to connect one text with another, which is necessary for understanding the final text.

And today we are working on experiments with hypertexts in paper form. In the analog system, the actual text that I read, the “pretext” that was given to me for preliminary review, and the “posttext” that is given for a better perception of the current text are distinguished.![]()

Meanwhile, in order to understand the text, you need to do something after reading it, because the process of perception is only a process. Now, when you listen to me, every time you catch a few words or a whole sentence. And in order to find out what you remember, you need to encourage you to do an essay, an essay, a retelling, some active action. You must present the learned content in a new sign form - in the form of drawings, texts.

Through links on the Internet, I can get a person to understand a text the way I want. Suggested references force the reader to refer to specific texts that are aimed at the desired interpretation of the information.

- You mentioned such a task of psycholinguistics as the study of the ontogeny of language. When and how does a child learn to communicate?

- In order to become a person, a child must be appropriated by the culture in which he was born. At what age should you start learning it? From birth. Of course, a child is born with some innate inclinations. For example, an infant does not need to be taught to suckle at the mother's breast. He does it reflexively. But in order to master his culture, he must learn, that is, master the objects of culture. The child is unable to do this on his own. Therefore, between the objects of culture and the child there must be an intermediary, an educator. Under his guidance, the child gradually masters certain actions. Thus, Vygotsky's cultural-historical theory is based on this principle of interaction between a child and an adult, and the actions performed by the adult are recognized by the child. And the consciousness of the baby is built from the images of actions that he performs with an adult even before he speaks. As a rule, normally the child begins to speak in the period from one to one and a half years. And if he has mastered the objective action, then the speech action will be mastered easily. Why? Because words for a child are equivalent to the surrounding objects that parents and other adults call.

Of course, a child is born with some innate inclinations. For example, an infant does not need to be taught to suckle at the mother's breast. He does it reflexively. But in order to master his culture, he must learn, that is, master the objects of culture. The child is unable to do this on his own. Therefore, between the objects of culture and the child there must be an intermediary, an educator. Under his guidance, the child gradually masters certain actions. Thus, Vygotsky's cultural-historical theory is based on this principle of interaction between a child and an adult, and the actions performed by the adult are recognized by the child. And the consciousness of the baby is built from the images of actions that he performs with an adult even before he speaks. As a rule, normally the child begins to speak in the period from one to one and a half years. And if he has mastered the objective action, then the speech action will be mastered easily. Why? Because words for a child are equivalent to the surrounding objects that parents and other adults call.

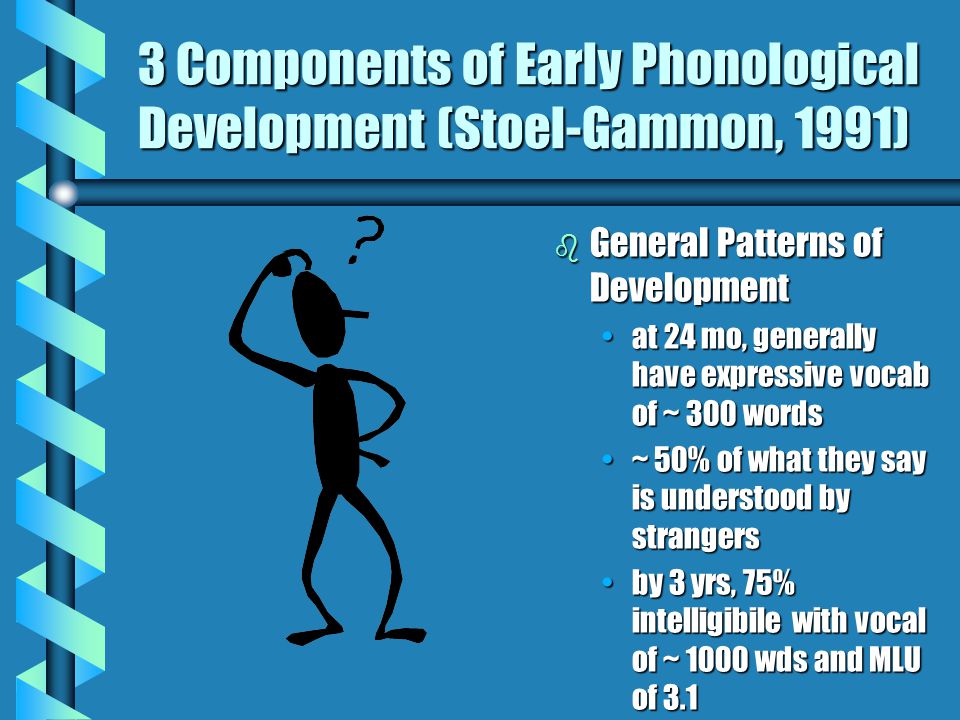

At the age of five or six, language acquisition is most intensive. For example, at a year and a half, a child speaks 30-40 words. At two years old, he should know about a thousand words. At preschool age - seven to eight thousand.

− What questions does modern psycholinguistics seek to answer? In what direction is it developing?

- If we talk about the national school, then the speech production model is actively developing here. This is a great merit of Tatyana Vasilievna Akhutina. She studies the pathologies of brain activity that lead to impaired speech.

In addition, the speech perception model of Irina Alekseevna Zimnyaya is being developed. Today we are jointly trying to establish a connection between linguistic and non-linguistic consciousness (images).

Modern linguists have formed quite extensive and deep ideas about what we do with speech in external form. But so far, unfortunately, explanatory models are not available to us, why we do it this way and not otherwise. Why? Because for this you need to take into account the psychological aspects. They are available only within the framework of psycholinguistics. Therefore, linguists naturally compete with their psycholinguistic colleagues.

Why? Because for this you need to take into account the psychological aspects. They are available only within the framework of psycholinguistics. Therefore, linguists naturally compete with their psycholinguistic colleagues.

One of the most interesting areas is associated with the creation of associative dictionaries. They capture the consciousness of the representatives of the modern generation. Associative dictionaries are compiled in the process of so-called associative experiments. Subjects are presented with a list of words. After each word, they should write the first word that comes to mind. This is how we fix the associative links and linguistic consciousness of the living speakers of a given language. Now I will pronounce the word and ask you to name the first association with it: "Woman."

− Man.

− Excellent! The most common answer. And it is no coincidence. Men and women go together in life. And if the frequency of “man” among Russians is 12%, then among the British it is 80%. Such associative dictionaries make it possible to make casts of the consciousness of the English, Russians, and Germans. Some tool for the analysis of linguistic consciousness.

Such associative dictionaries make it possible to make casts of the consciousness of the English, Russians, and Germans. Some tool for the analysis of linguistic consciousness.

Another direction is connected with the isolation of basic values. Let's say, "poverty", "lack of spirituality", "irresponsibility" - anti-value, "security" - value. In experiments, we see what the bearers of Russian culture consider as a value and with what words it is described.

I think that the problems of production, speech perception, language ontogenesis, speech communication are eternal. At all times, each next generation needs to form the skills of verbal communication. For what? So that they can simply survive in society. And since generations are constantly replacing each other, this activity is endless. If it stops, there will be no culture. Without culture there will be no society. Without society - individuals, because a person cannot survive alone. We all live in a society.

📖 Phonological Awareness, Speech Development, Chapter 11.

Communication and Developmental Disorders of School Skills. Children's pathopsychology. Mash E. Page 87. Read online

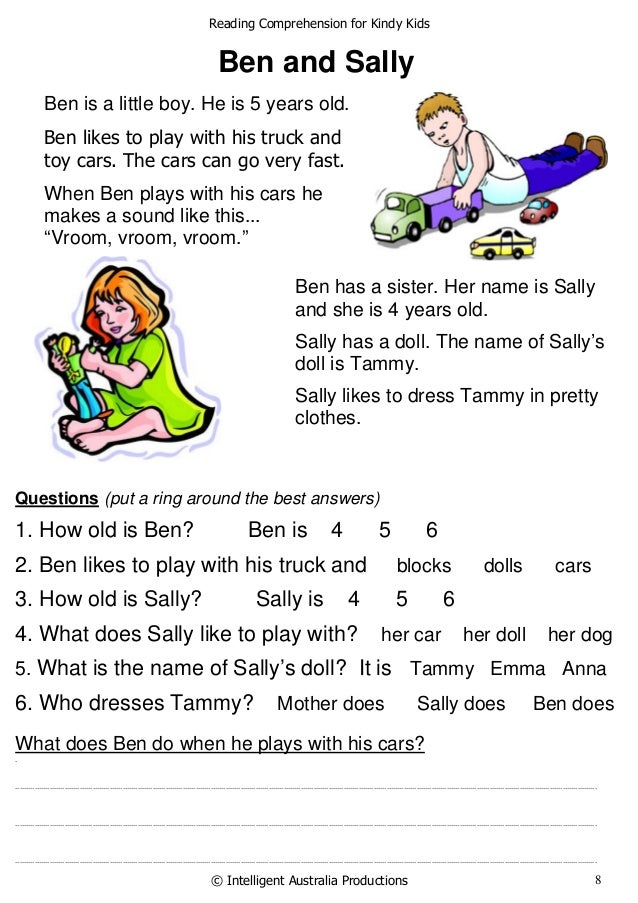

Communication and Developmental Disorders of School Skills. Children's pathopsychology. Mash E. Page 87. Read online At first, babies listen to the sounds of their parents' speech and soon begin to communicate using basic gestures and sounds. During their first year of life, they may learn a few words and even create new words to express their desires and emotions. After two years, language development is rapidly progressing, and their ability to coherently formulate their thoughts and express new concepts is the delight and admiration of parents. Adults play an important role in encouraging the development of a child's language skills by improving speech and enjoying children's expressions.

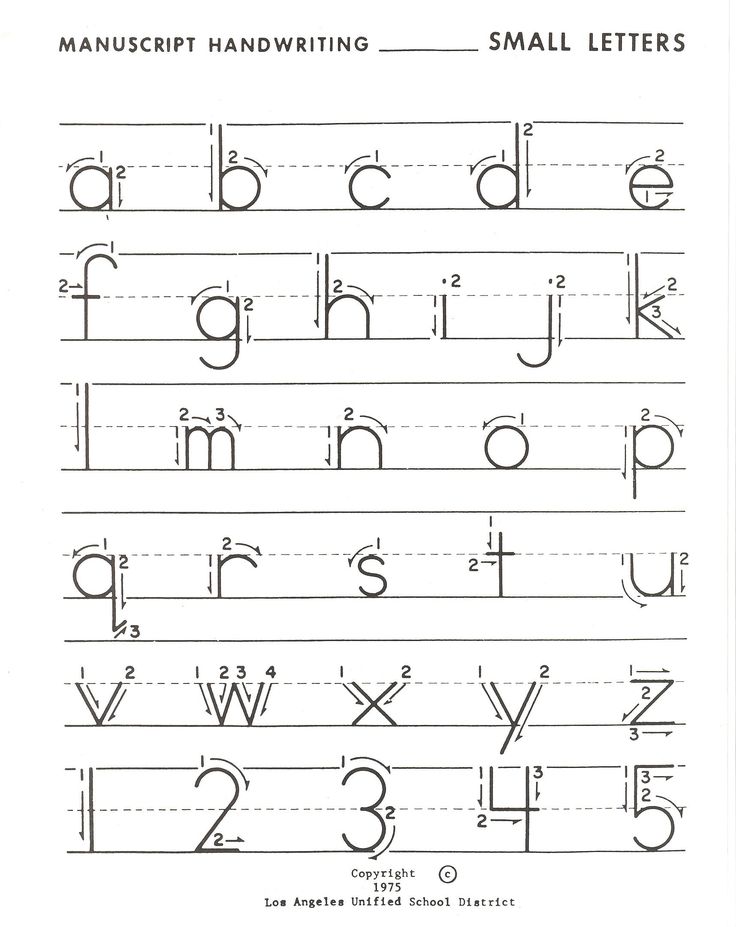

A language consists of phonemes that are basic sounds (such as plosives b, e or vowels and, e) and form the language. When a child constantly hears a particular phoneme, ear receptors stimulate the formation of appropriate connections and transmit them to the auditory part of the cerebral cortex. The formed perception map is a set of sounds similar to each other, which helps the child to recognize different phonemes. These cards form quickly; six-month-old babies of English-speaking parents already have auditory maps that differ from the auditory maps inherent, for example, in babies in Swedish families, which depends on the different activity of neurons for different sounds (Kuhl, 1995). By the first year of life, the cards are formed, and babies lose the ability to distinguish sounds that are not important for their native language.

The formed perception map is a set of sounds similar to each other, which helps the child to recognize different phonemes. These cards form quickly; six-month-old babies of English-speaking parents already have auditory maps that differ from the auditory maps inherent, for example, in babies in Swedish families, which depends on the different activity of neurons for different sounds (Kuhl, 1995). By the first year of life, the cards are formed, and babies lose the ability to distinguish sounds that are not important for their native language.

It is the rapid development of the perceptual map that causes difficulties in learning a second language after the first: the fact is that the connections in the brain are already formed, and the remaining neurons are almost unable to form new basic connections, say, for the Swedish language. When the described cycle is established, babies can make words out of sounds, and the more words they hear, the faster they learn the language. Sounds serve to strengthen and expand neural connections, which in turn ensures the formation of more words. Similar cortical circuits are formed as the basis for other activities, such as music. A young child who is learning to play a musical instrument may have neuronal circulation activated, which will favorably develop his spatial thinking and mathematical abilities (Hancock, 1996).

Similar cortical circuits are formed as the basis for other activities, such as music. A young child who is learning to play a musical instrument may have neuronal circulation activated, which will favorably develop his spatial thinking and mathematical abilities (Hancock, 1996).

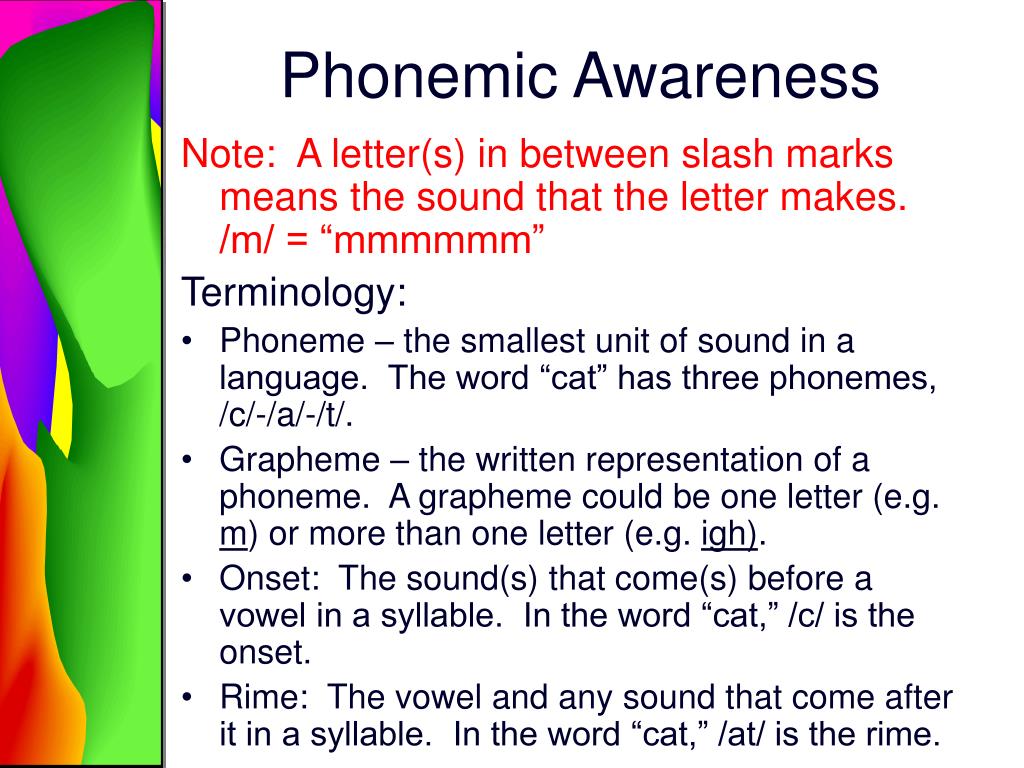

Phonological awareness.

Not all children progress normally in their language development, some are very lagging behind, using mostly gestures or sounds to communicate, rather than speech. Others develop normally following verbal commands, but have difficulty finding words to express their thoughts clearly.

Psychology bookap

Although the development of speech is one of the main indicators of general intelligence, as well as the development of the school curriculum (Sattler, 1998), the difference in this indicator is in no way a sign of intellectual retardation or cognitive impairment in children. Rather, such deviations from the norm may indeed be only deviations and are accompanied by pronounced abilities in other areas. Albert Einstein, considered an intellectual genius, started talking late, stammering and making his parents think he was "not quite normal". Family tradition says that when a father asked the headmaster what profession he would advise his son to take, the answer was simple: “It does not matter, because he will never succeed in anything” (R. W. Clark, 1971, p. 10).

Albert Einstein, considered an intellectual genius, started talking late, stammering and making his parents think he was "not quite normal". Family tradition says that when a father asked the headmaster what profession he would advise his son to take, the answer was simple: “It does not matter, because he will never succeed in anything” (R. W. Clark, 1971, p. 10).

Because speech development is an indicator of overall mental development (Sattler, 1998), children with language delays or severe language delays are considered to be at risk. As is known, Albert Einstein's speech problems were precursors to his subsequent communication and learning disorders (Benasich, Curtiss & Tallal, 1993; B.A. Lewis, Freebarn & Taylor, 2000).

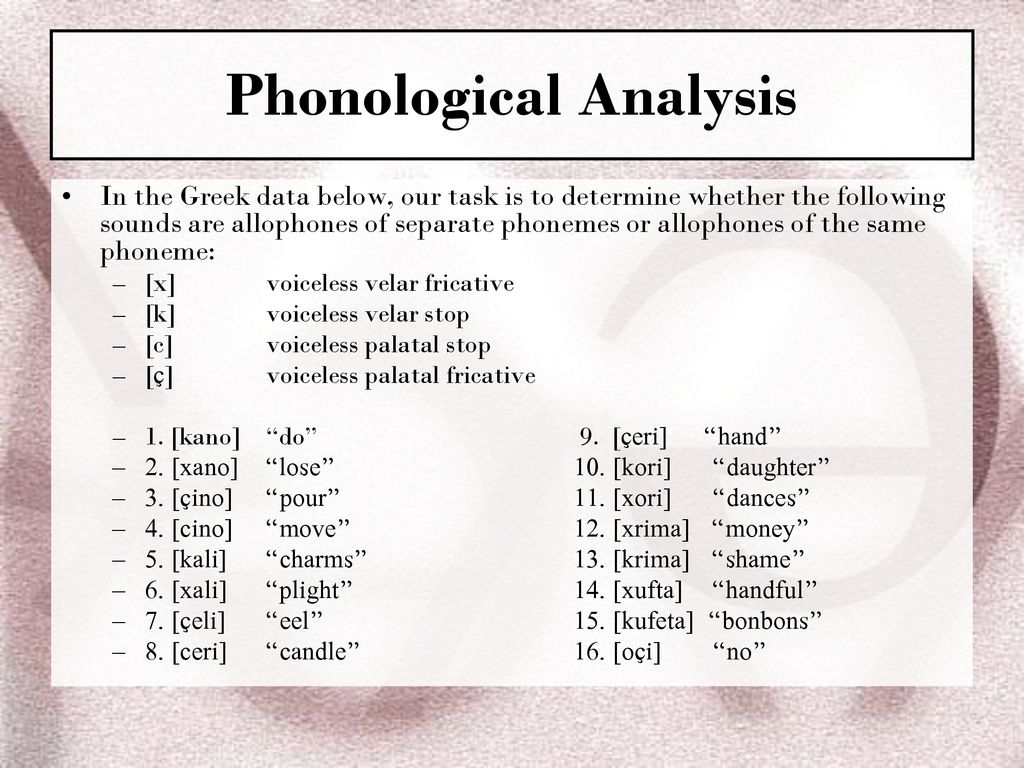

Phonology is the ability to memorize and store phonemes, as well as the rules for composing semantic compounds or words from sounds. The impairment of this ability is the main reason why most children and adults with communication and learning disabilities have language problems such as reading and writing.

A young child needs to realize that speech is divided into phonemes (English has 44, such as ba, ga, at and tr). Many children find it very difficult to understand that speech does not consist of individual phonemes that follow one another. Instead, the sounds are articulated at the same time as (overlapped) so that one can speak faster than if they were spoken in succession (Liberman & Shankweiler, 1991).

By the age of seven, about 80% of children are able to break words and syllables into phonemes (Blachman, 1991), but there are those who cannot do this. These are children who have serious problems in mastering reading skills (B. A. Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 1994).

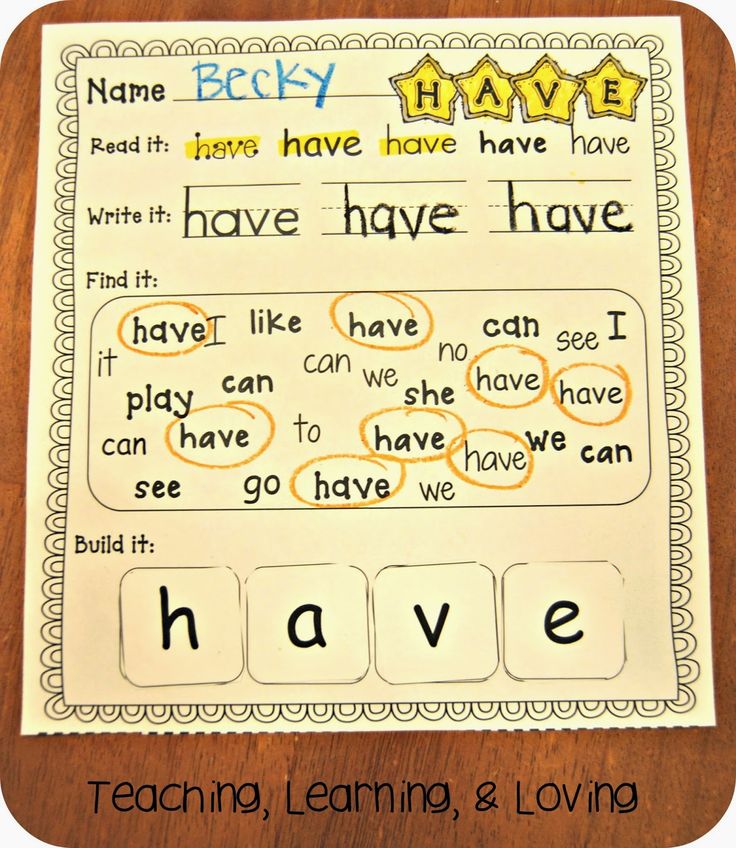

At school entry, early language problems become learning problems as children have to learn to correlate spoken language with written language. Children who find it difficult to learn to read and write also find it difficult to learn the system of letters and sounds. These children cannot correctly pronounce the sounds in the syllables of words, which is called a lack of phonological awareness and is a harbinger of reading problems (Frost, 1998).

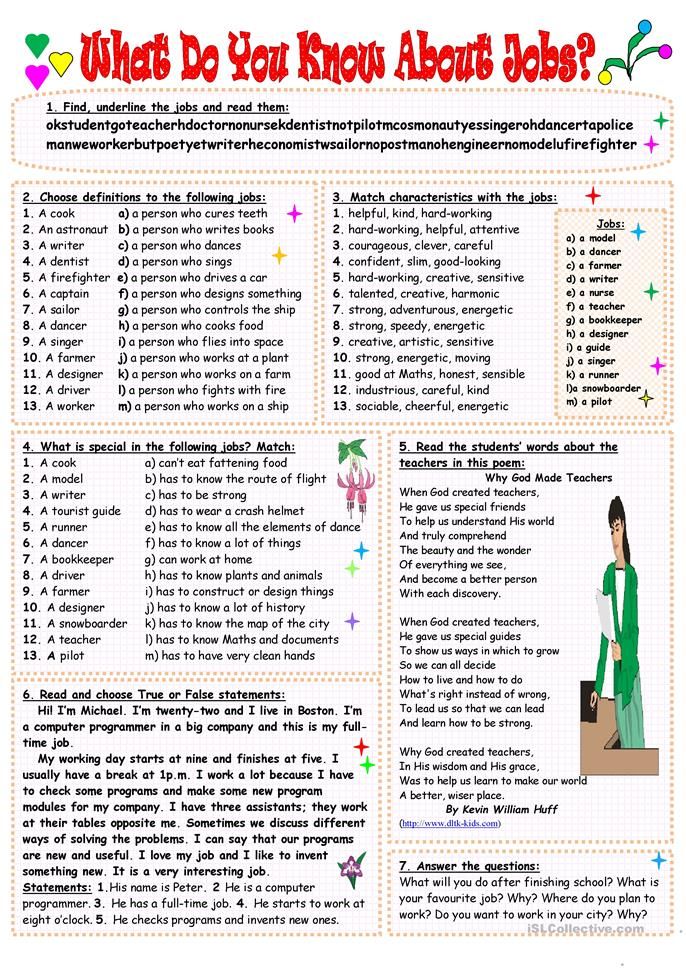

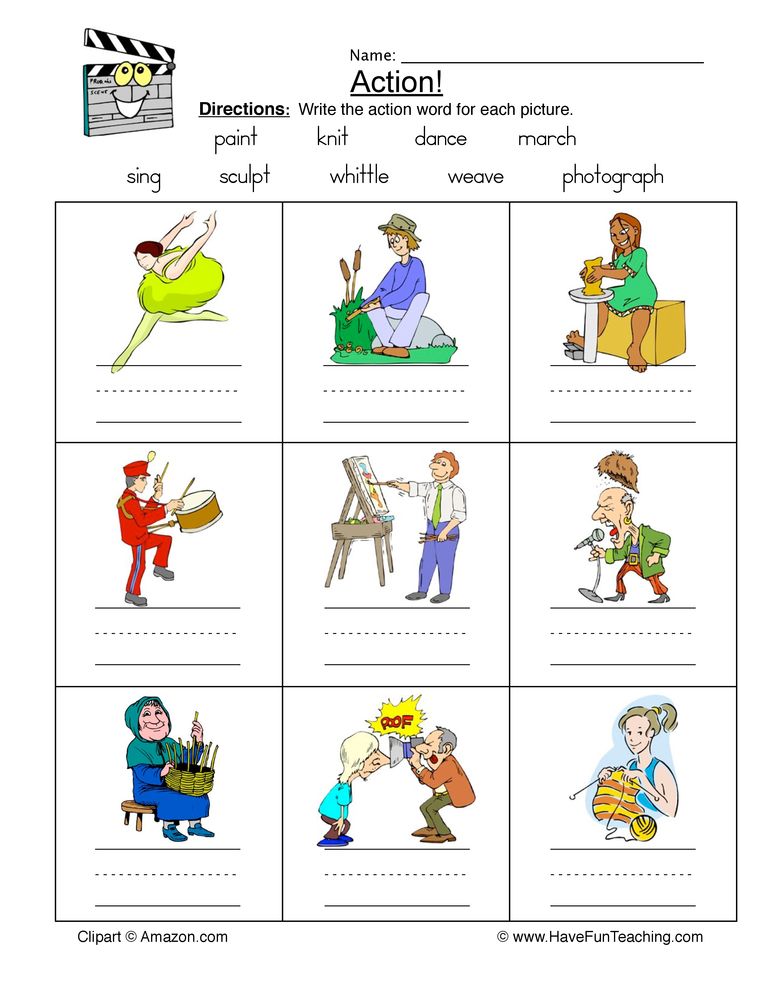

Phonological awareness is a broad generalization that includes recognizing the relationships that exist between sounds and letters, identifying rhythm and alliteration, and knowing that sounds can make up different syllables in words. To determine the level of phonological awareness among primary school students, teachers ask them to rhyme words or rearrange sounds. For example, the teacher might say "cat" and ask the child to say the word without the first sound k, or say "house" and the child must say a word without m. To assess the child's ability to connect sounds, the teacher can say, for example, three sounds t, p and and, and see if he can the child pronounce these sounds together, adding them to the word "three".

While phonological awareness is a prerequisite for developing reading skills, it is also closely related to the development of expressive language (Edwards, Fourakis, Beckman, & Fox, 1999). In the process of reading, it is very difficult for those who experience significant difficulties in pronouncing sounds to differentiate phonemes, remember the names of ordinary objects and letters, as well as store phonological codes in short-term memory, recognize a phoneme and reproduce some speech sounds.

g. cat – hat – big)

g. cat – hat – big) g. Say ‘cupcake’. Take away ‘cup’ and what is left? cake)

g. Say ‘cupcake’. Take away ‘cup’ and what is left? cake)