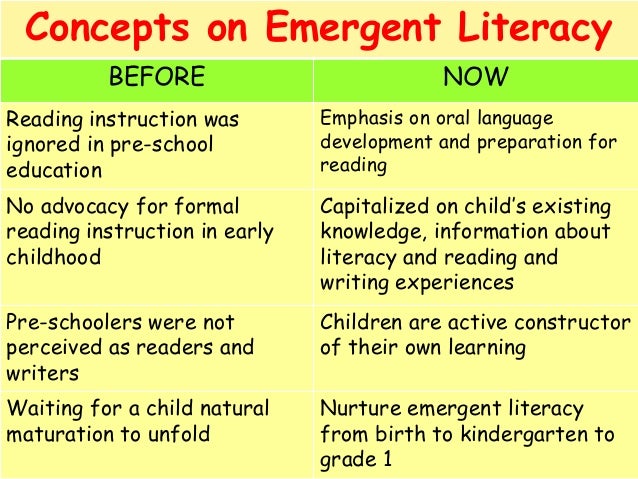

Pre emergent reader

A Guide to Emergent Readers and Stages of Development – AdaptEd4SpecialEd

Krystie Yeo on

As a teacher, you know each of your students is unique. Never is that more apparent than with developing readers.

But you have lesson plans to propose and an entire class of students to teach.

You don't have time to design a reading development strategy for each of your little readers. Instead, you need a plan that will meet your students where they are, wherever that may be.

That's where the stages of reading development come in.

From early emergent readers to fluent readers, this simple breakdown helps you understand what stage each of your students is in so you can better meet their needs.

Want to know how to keep your readers on track and engaged?

Check out this guide to designing an instruction plan that addresses student readers of all stages.

What Is an Emergent Reader?

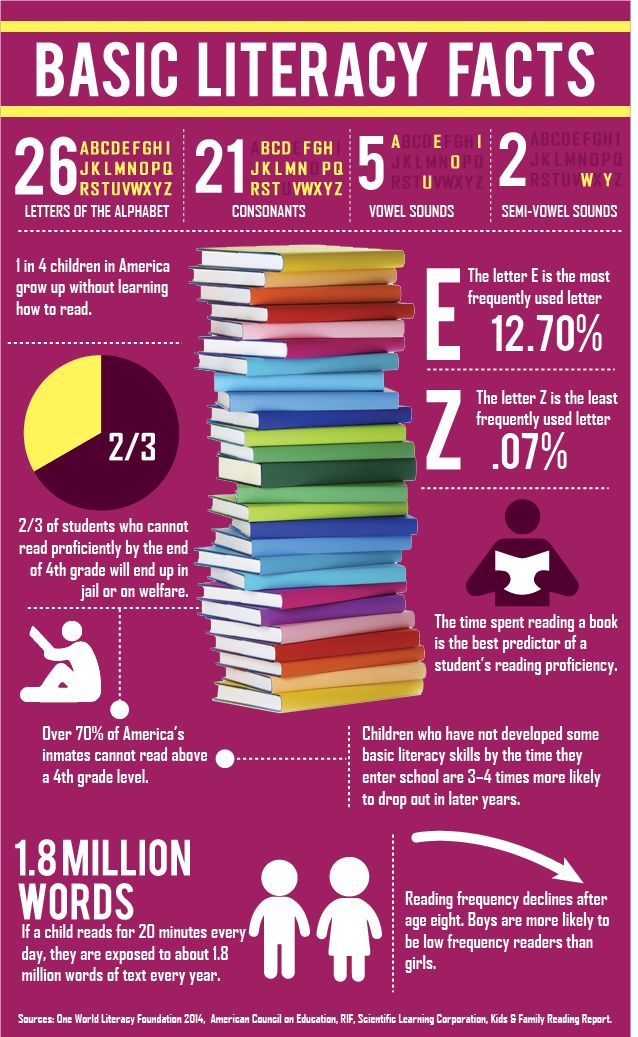

The emergent reader stage is one of the most vital in a student's journey. After all, 65% of 4th-grade students read at or below an early fluent reading level, which is only one step above the emergent reader stage.

Making sure a student progresses beyond emerging reader status with confidence and excitement, then, is important for assuring they improve beyond a basic level of reading comprehension.

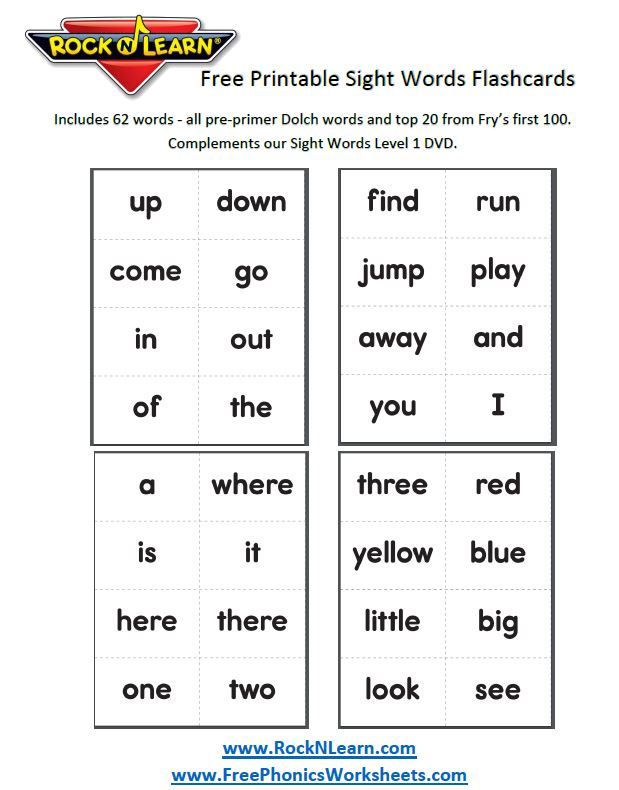

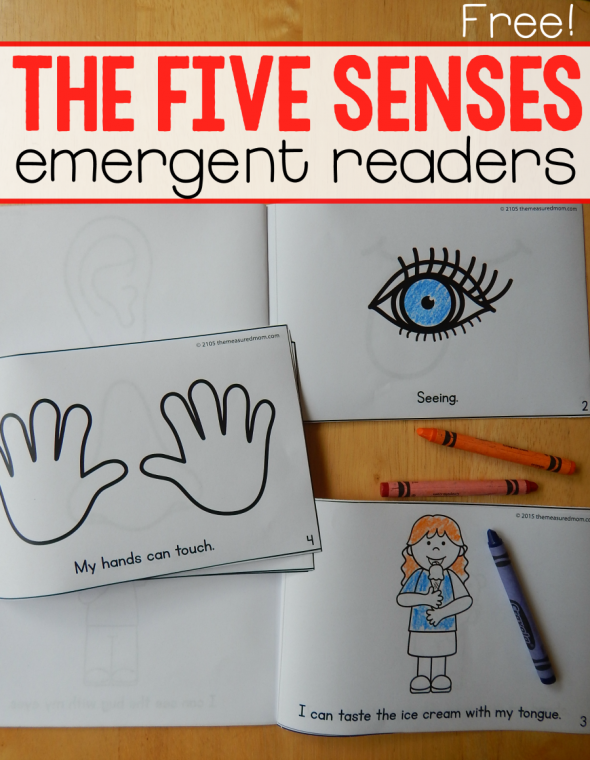

Compared to an early emergent reader, emergent readers have learned the alphabet and have a handle on a large vocabulary of CORE words.

They've progressed beyond picture books and books with small regions of text. Now, your emergent readers have a good understanding of phonics and are starting to comprehend word meanings in addition to word sounds.

Emergent readers will typically read books with increasingly larger blocks of text. They can handle more complex sentences and rely less on pictures for comprehension.

While they may read books on familiar topics like home and family life, these stories go into greater depth than their early emergent reader precursors.

What's more, these students will have more confidence in recognizing high-frequency words.

They're venturing into both fiction and non-fiction stories. And most excitingly, emerging readers have begun to discover that reading has many uses and purposes beyond the classroom.

How to Engage and Excite Your Emergent Reader

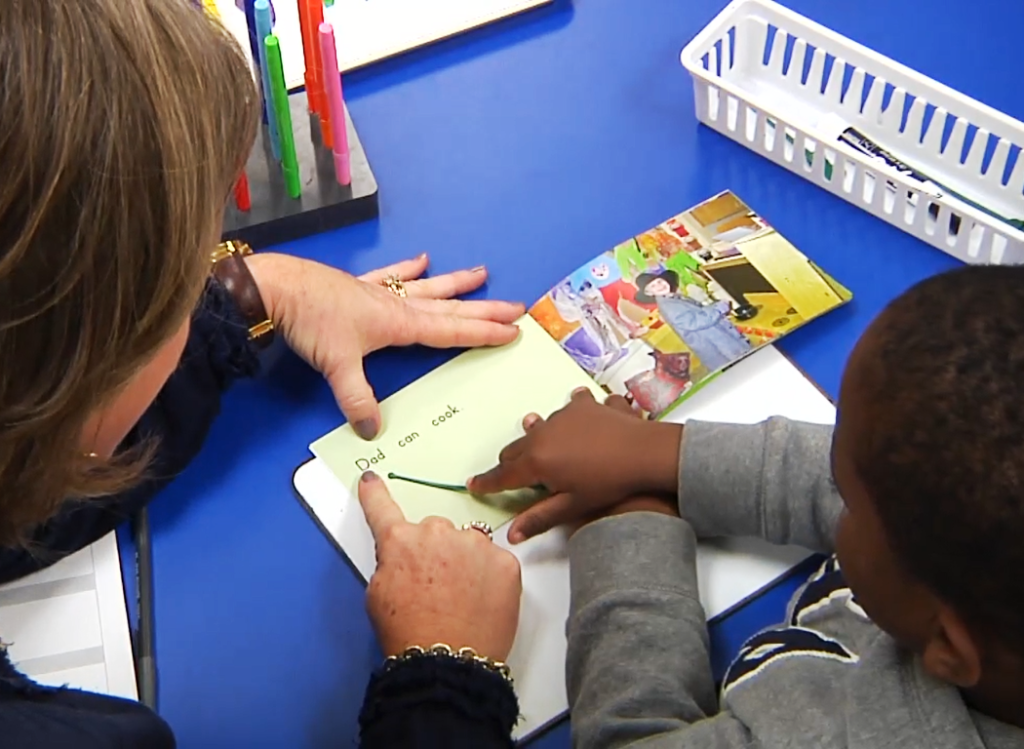

Engaging and exciting your emergent reader is all about choosing the right books and offering assistance only when needed. The reasons behind this latter point are twofold.

First, your student needs to know they are supported and that you're there for assistance with sounding out words or comprehending definitions if needed.

But secondly, too much help can actually be detrimental to the child's confidence in their abilities.

They need to know that you think they can read independently. That way, it gives them the space to form their own confidence in reading independently.

The other tips for engaging and exciting your students is a no-brainer.

Choosing the right books that are challenging but not so challenging that the student feels defeated is vital to helping emerging readers move into the next stage of development. Our phonics collection starts at the very beginning.

Here are three books that we think are perfect for your emerging reader:

- A Giraffe and a Half by Shel Silverstein

- Look What I Can Do by Jose Aruego

- Do You Want to Be My Friend? by Eric Carle

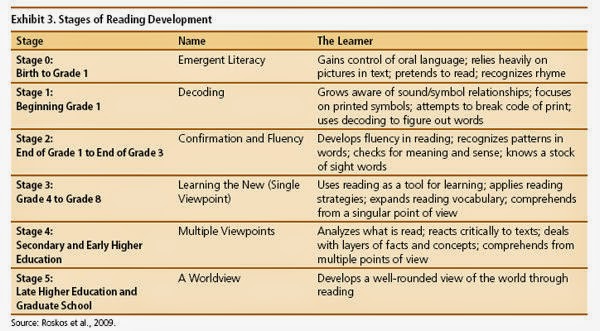

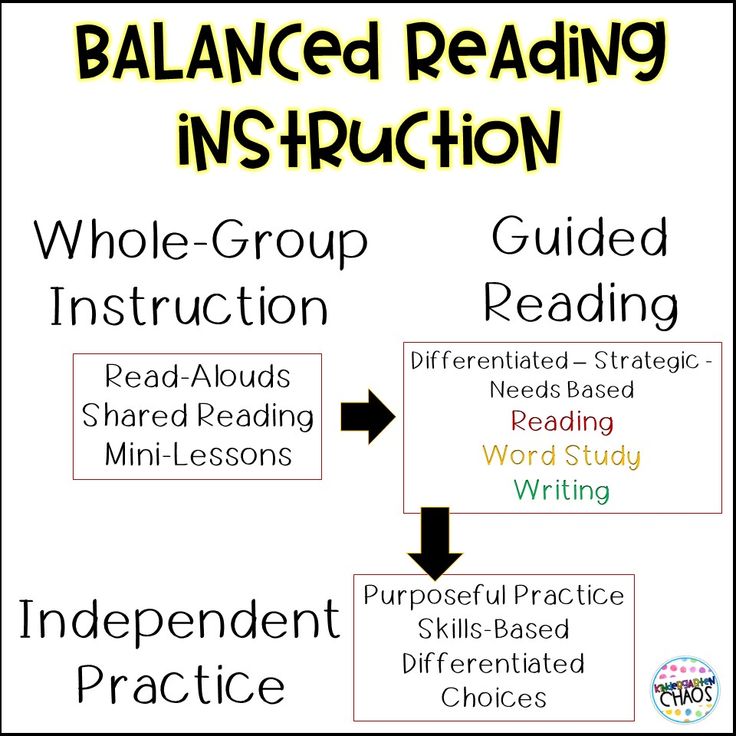

The 4 Stages of Reading Development

If you have a student who is still struggling to achieve emergent reader status despite your very best efforts, it's time to return to the four stages of development.

That way, you can see where your student is lagging while also exciting your little reader with all the learning they have to look forward to.

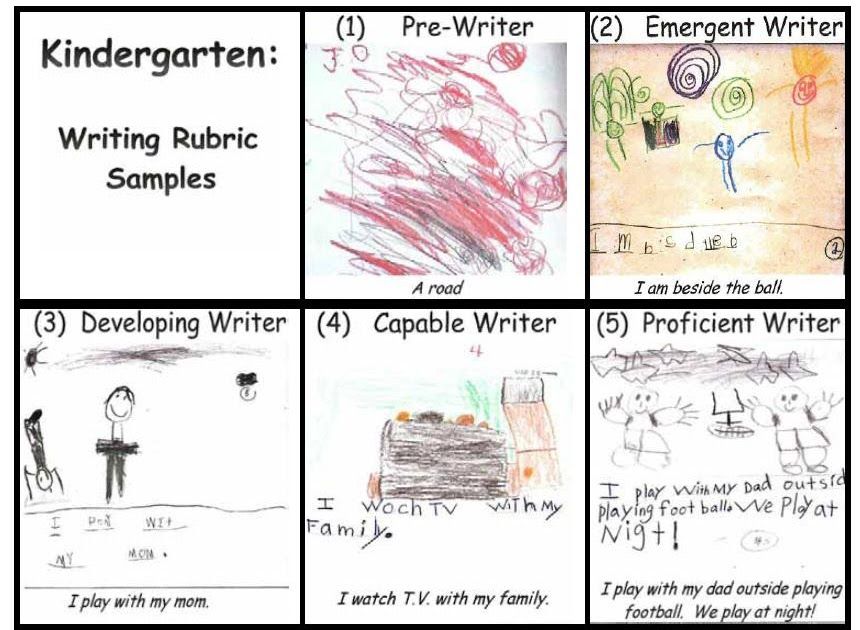

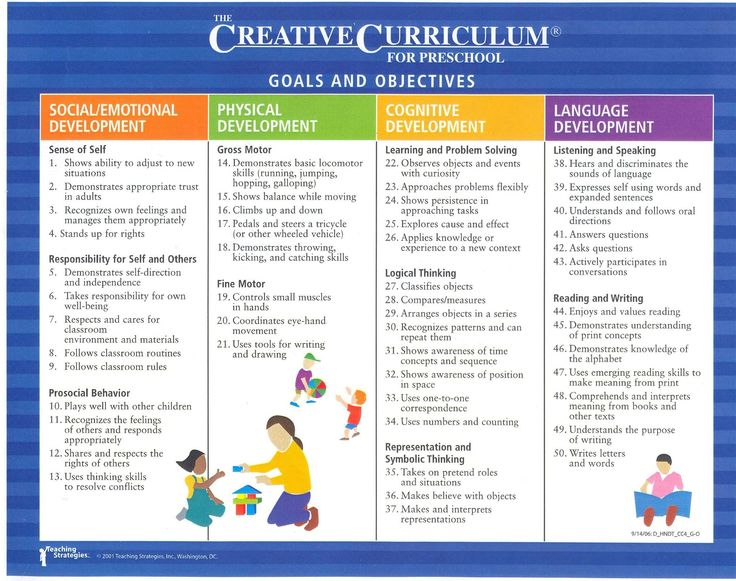

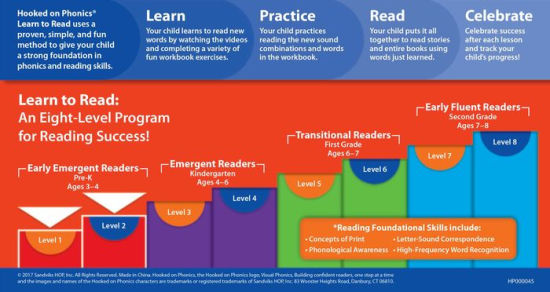

1. Early Emergent Readers

Early emergent readers are just beginning their reading journey.

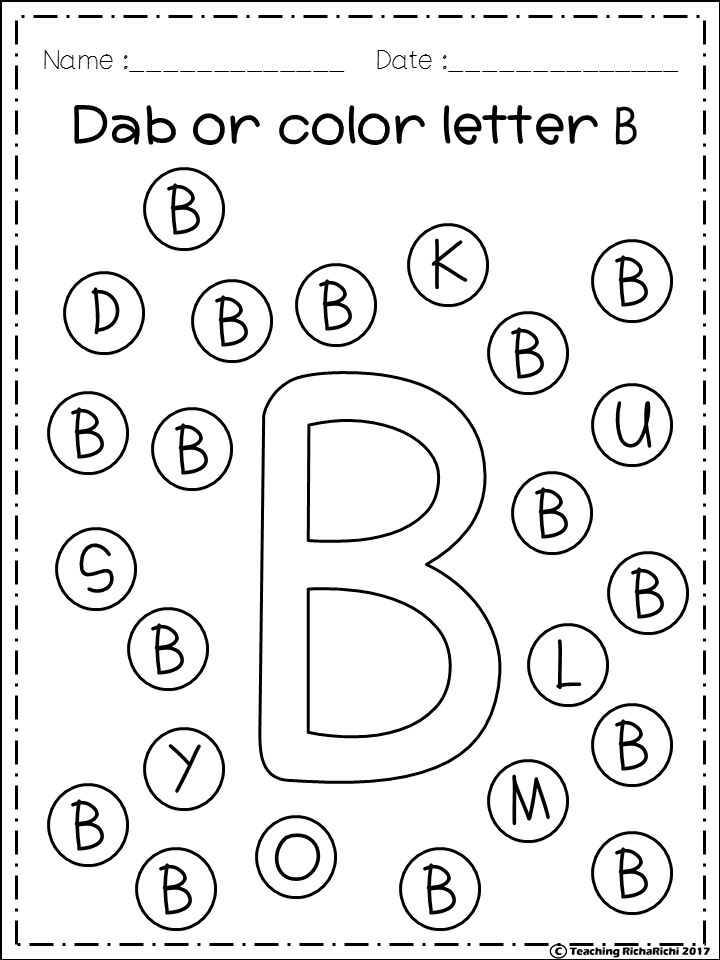

These students are typically 6 months to 6 years old and are learning the alphabet.

As they advance, these readers begin to recognize the difference in uppercase and lowercase letters.

Aside from the alphabet, early phonics is extremely important during this phase.

Children should be learning the relationship between the way a letter looks and its associated sound, beginning with the differences in vowels and consonants.

You'll know your early emergent reader is on the cusp of becoming an emergent reader when they begin to automatically recognize high-frequency words (core vocabulary words).

Also, your almost-emergent readers will be able to read consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) words.

2. Emergent Readers

As we mentioned above, emergent readers have learned the alphabet and are beginning to understand early phonics.

They can often read independently with assistance if needed.

You know your emerging reader is moving on to the next stage if they're starting to comprehend word meaning more automatically instead of focusing on word recognition alone.

3. Early Fluent Readers

This stage is where the magic starts to happen. Early fluent readers are typically between the ages of 7 years and 10 years old.

And at this point, not only can students identify word sounds on their own but they can also comprehend those word meanings independently.

These readers should be given books of different varieties now so that they can appreciate the diversity of the form.

This is a great time to introduce students to genre fiction, an excellent way to excite your early fluent readers with fun, engaging stories.

Complete independence while reading and comprehending is a signal that your early fluent reader is ready to progress.

4. Fluent Readers

If your student or child has made it to this stage, congratulations!

Considering that only 34% of 8th graders achieved National Assessment of Educational Progress "Proficient" reader scores in 2018, this is truly an accomplishment for the record books.

A hallmark of this stage is the ability to read aloud with proper pauses for punctuation.

Fluent readers need absolutely no assistance with reading comprehension. And they are starting to actually understand the meaning behind what they read instead of just comprehending word meanings.

At this point, your fluent reader should begin to choose their own books and form preferences about what they like to read.

This is an exciting time in a student's reading development journey. But it's also an exciting point, in general, since becoming a fluent reader is a major pit stop along the road to true independence.

Special Education for Your Struggling Reader

Are your emergent readers struggling to move on to the next stage of development?

Check out AdaptEd's carefully curated selection of books to engage and excite your child or students today!

Stages of Development | Reading A-Z

> Instructional Support > Stages of Development

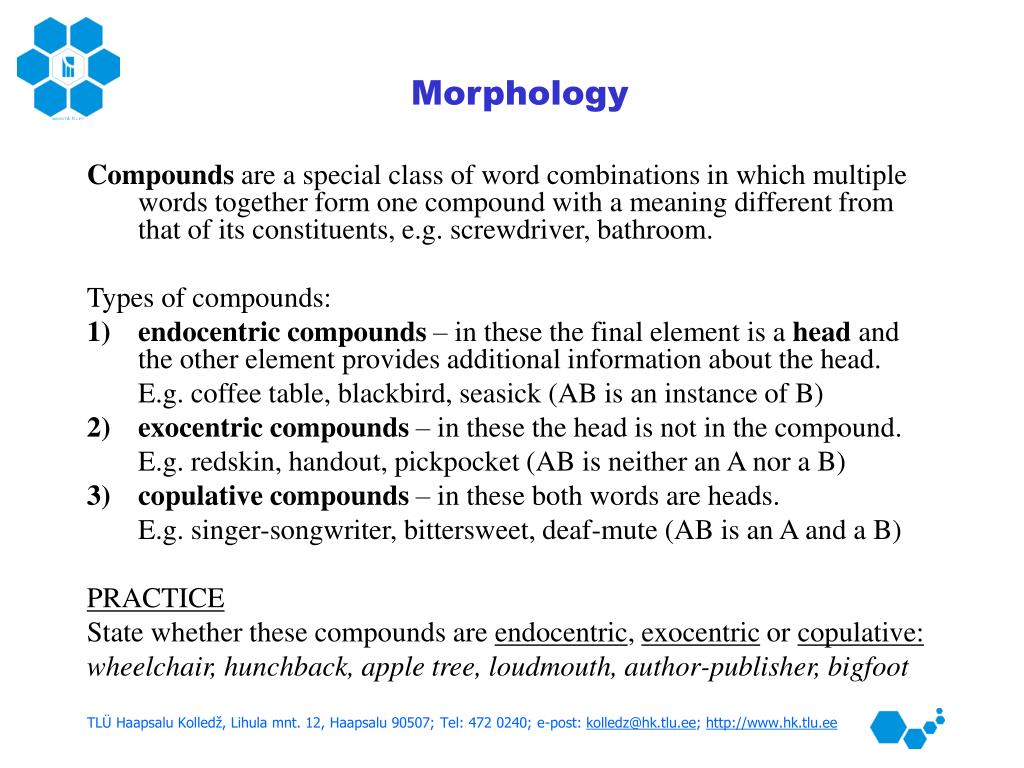

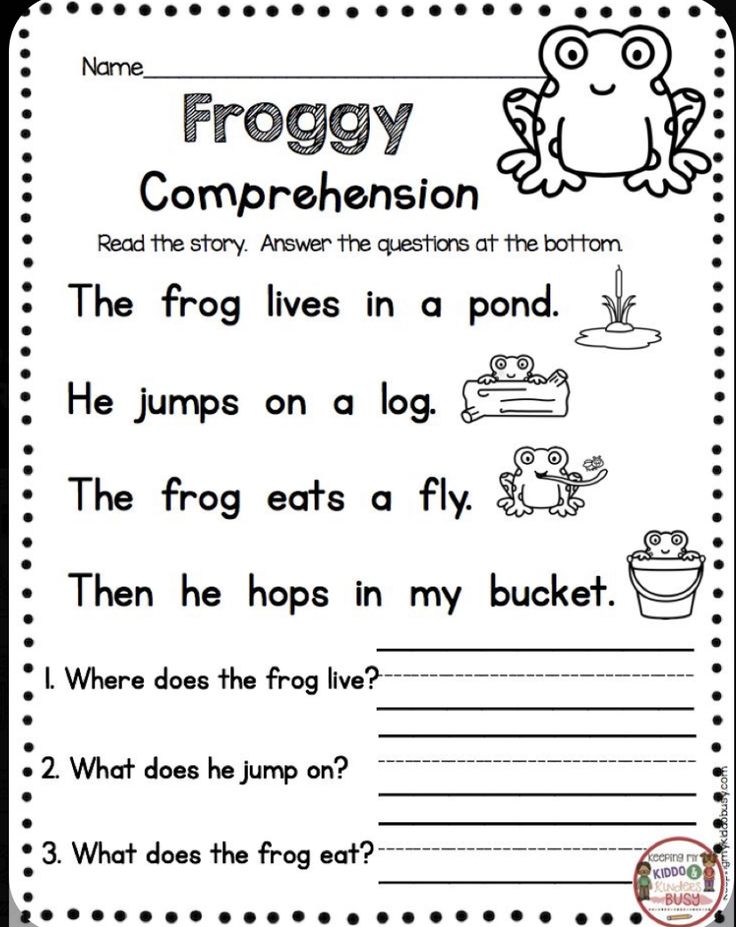

Beginning Readers (Levels aa-C)

Readers at this level might display the following characteristics:

- Pretend to read familiar stories

- Sing their ABCs but not be able to name all of the letters in print

- Recognize and name more letters as they are exposed to print and instruction

- Identify the front cover

- Turn pages one by one

- Show how text progresses left to right, top to bottom

- Identify uppercase letters with greater ease than lowercase letters

- Know some sounds of frequently seen or previously taught letters

- Identify and produce an increasing number of sounds, particularly consonant sounds and short vowels

- Recognize environmental print in context

- Attempt to track print with their finger in books and other texts

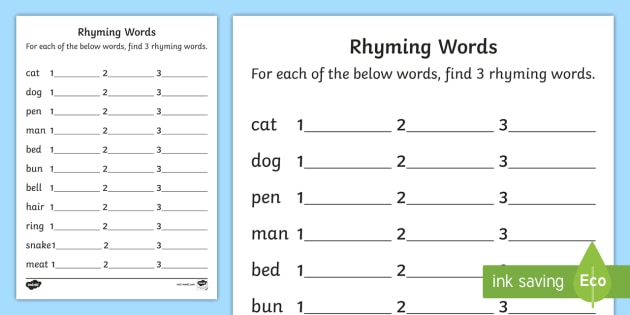

- Begin to play with words

- Identify a rhyming pair when presented with choices (e.

g., rat, bed, hat)

g., rat, bed, hat) - Count syllables in words

- Listening comprehension far exceeds reading comprehension (the latter is limited to single words or short phrases/sentences)

Text to support readers at this level may include:

- Detailed pictures that add to the story

- Short, declarative sentences

- Repetitive patterns

- Repeated vocabulary

- Natural, familiar language

- Large print

- Wide letter spacing

- Familiar concepts

- Limited text per page

Developing Readers (Levels D-J)

Readers at this level might display the following characteristics:

- Apply their understanding of phonics for reading unfamiliar words

- Focus most of their energy on decoding, which leaves fewer cognitive resources for comprehension

- Recognize more frequently read words by sight

- Attempt to sound out unknown words, phoneme by phoneme

- Realize that their reading should make sense and will attempt to self-correct when making errors

- Look for word chunks to assist in reading

- Listening comprehension still exceeds reading comprehension, although readers begin to get meaning from text

Text to support readers at this level may include:

- Increasingly more lines of print per page

- More complex sentence structure

- Fewer repetitive patterns

- Pictures that relate to the story

- Familiar topics with more details

Effective Readers (Levels K-P)

Readers at this level might display the following characteristics:

- Attend to the phonics, word chunks, affixes when decoding unfamiliar words in their entirety, including multisyllabic and compound words

- Recognize more and more words automatically by sight

- Guess or predict what they think the sentence says rather than reading each word as it is written

- Glance ahead to prepare for upcoming words

- Focus less of their energy on decoding, which leaves more cognitive resources for comprehension

- Begin to transition from learning to read to reading to learn as they use text to learn new information

Text to support readers at this level may include:

- More pages

- Longer sentences with more complex syntax

- More text per page

- Richer vocabulary

- Greater variation in sentence pattern and exposure to a variety of text structures

- Fewer pictures

- More formal and descriptive language

Automatic Readers (Levels Q-Z2)

Readers at this level might display the following characteristics:

- Use phonics, syllable knowledge, and morphology to decode unknown multisyllabic words

- Recognize words they repeatedly see in text by sight

- Use fluency and prosodic reading at an appropriate rate

- Focus on comprehension as decoding becomes automatic

- Rely on text for directions, content knowledge, and general information

Text to support readers at this level may include:

- More text

- Less familiar, more varied topics

- Challenging vocabulary

- More complex sentences

- Varied writing styles

- Few, if any pictures

- Text features to support understanding (graphs, charts, infographics, etc.

)

) - Text structures (compare and contrast, cause and effect, problem/solution, sequence, descriptive)

|

The "Mythology of the Slavs" by A. Geishtor, as according to a well-known Latin proverb, had its own special destiny. For the average reader it was all new and difficult, and it was also written in an elegant style, but in a special language, free from any simplifications that make it easier to read. However, this success came at a price. The academic text, based on the rich and varied literature on the subject, was published without footnotes. This was the rule of the publishing series and the harsh requirement of the publisher, who was careful not to alienate the general reader. However, the lack of a scientific reference apparatus prevented scientists from using this book in their works and in many respects led to the fact that the "Mythology of the Slavs" was unfairly considered popularization. As a result, the work of Geishtor did not wait for translations and did not take a well-deserved place of honor among the achievements of European medieval studies. Although A. Geishtor prepared the full version of his book for German translation, he did not have time to fulfill his intention to the end. nine0011 We owe this publication to Dr. The twenty-three years that have passed since the publication of the first edition have not deprived The Mythology of the Slavs of its innovative value. During this time, of course, new works appeared in this area; The reader will find a brief overview of them in the Afterword by L.P. Slupetsky. Since the publication of the book, the charm of the concept of J. Dumézil, which A. Geishtor, not without reservations, accepted as a particularly important frame of reference, has also faded. New intellectual currents that appeared in Europe and America brought into the humanities a fashion for extreme relativism, called postmodernism, based on an ontological principle that denies the existence in the past and present of historical reality beyond the boundaries of the text. However, neither new philosophical constructions nor the achievements in the field of religious studies accumulated over the past quarter of a century deprive the "Mythology of the Slavs" of its pioneering value for interdisciplinary research that expands the horizons of modern humanitarian knowledge. The novelty of Geishtor's book lies in its going beyond the narrow disciplinary framework in which historians, linguists, religious scholars and ethnologists are kept by the fear of violating the strict rules of methodological correctness. A. Geishtor was a recognized authority in the study of medieval sources. He cannot be accused of ignorance of secrets or of neglecting the methodological requirements necessary in our profession. At the same time, A. Geishtor can be called the last great historian, whose comprehensive erudition allowed him to enter the field of art history, archeology, linguistics and ethnography. Finally, thanks to professional caution and responsibility, A. “Thanks to other researchers, primarily ethnographers, representatives of cultural anthropology and semiotics,” A. Geishtor wrote in the preface to “The Mythology of the Slavs,” we already differently evaluate the religious value of folk culture, the subject of which also becomes the object of research by the historian of religion [. ..]. There is no doubt that it is this sphere that keeps in itself opportunities that have not yet been used by researchers of Slavic beliefs and religious practices. Just one eloquent example is enough to understand what perspectives for the study of medieval paganism are provided by the use of modern folklore by the medievalist historian. At the end of the XII century. Saxo Grammatik described in detail the pagan ritual that was performed annually after the harvest at the sanctuary of Sventovit on the island of Rügen. At the climax of the celebration, a large sacrificial cake was brought out, the dimensions of which were only slightly inferior to human growth. The priest put this cake between himself and the people gathered in front of the temple and asked: “Do you see me?” To an affirmative answer to those gathered, he answered with a wish that next year he could no longer be seen. A. Geishtor insistently emphasized that rites are a path leading to a myth, since there was some kind of myth behind each rite[3]. Thanks to this methodological directive, it became possible to compare the medieval source of the XII century. and ethnographic material of the XX century. and to draw a conclusion about the existence of the same myth at different ends of the Slavic world, testifying to the belief shared by all Slavs in the main gods common to them. There is no doubt that the report of the chronicler of the XII century. about pagan rituals on Rügen and evidence of a church holiday in a Bulgarian village of the 20th century. speaks of the same ritual dialogue. In the name of what is the historian, concerned about methodological correctness, not only ignoring similarities between sources, but also failing to explain them? The only noticeable reason why the researcher refuses to note and consider this similarity is the unfounded and therefore arbitrary conviction that the sacred samples of traditional culture cannot exist for such a long time. Combining the research perspectives of historiography and cultural anthropology allows historians to discover a new dimension of the old truth about the past (including the most distant) living in the present. The historical heritage present in the present can, as in the case of religious studies related to Slavic folklore, become the basis for the reconstruction of ancient cultures. At the same time, the study of the question of the presence of history in the present is also necessary for understanding modernity. Neither a sociologist nor an anthropologist can do this without a historian, just as a historian without a sociologist and especially an anthropologist will not understand the principles on which the structures of the past function in modern culture. K. Modzelevsky Notes 1. Geishtor A. Mythology of the Slavs. M.: Ves Mir, 2014. S. 22 (further see this edition). | ||||

Brief essay on the history of Syriac literature - prof. PC. Kokovtsev

prof. PC. Kokovtsev

Download

Original: pdf8Mb

Foreword of the Russian translation

We gladly agreed to take the trouble to review and, wherever necessary, supplement this translation of the well-known work of the late English Orientalist. Its appearance in Russian will, no doubt, fill one of the most essential gaps in our scholarly literature on Oriental studies, since the urgent need for a good Russian textbook on the history of Syriac literature, which is one of the subjects of scientific teaching at the Faculty of Oriental Languages of St. Petersburg University, was especially strongly recognized. This consciousness could naturally only become stronger under the influence of a more lively interest in the ancient Syrian people, which has awakened in our fatherland in recent times after a certain conversion to Orthodoxy of a part of this people in the person of the Nestorians of Urmia. We could therefore only rejoice in the fact that a happy chance gave us, sooner than we could have hoped, the opportunity to fulfill some kind of moral obligation that lay upon us, both in relation to the literature itself, and to the Russian public. nine0011

Its appearance in Russian will, no doubt, fill one of the most essential gaps in our scholarly literature on Oriental studies, since the urgent need for a good Russian textbook on the history of Syriac literature, which is one of the subjects of scientific teaching at the Faculty of Oriental Languages of St. Petersburg University, was especially strongly recognized. This consciousness could naturally only become stronger under the influence of a more lively interest in the ancient Syrian people, which has awakened in our fatherland in recent times after a certain conversion to Orthodoxy of a part of this people in the person of the Nestorians of Urmia. We could therefore only rejoice in the fact that a happy chance gave us, sooner than we could have hoped, the opportunity to fulfill some kind of moral obligation that lay upon us, both in relation to the literature itself, and to the Russian public. nine0011

The choice of Wright's article, which appeared initially in 1887 in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, and then seven years later, with significant additions, and a separate book, is explained, regardless of the great scientific merits of this work, primarily by the fact that when the present translation was started, this essay was on this subject, one might say, the only one. Duval's French work, which appeared about three years ago in the series Bibliotheque de I Enseignement de I Histoire ecclesiastique (II volume of Anciennes Litteratures Chretiennes; 1st ed. published in 1899, 2nd in 1900), - a work more extensive in volume and therefore naturally in many departments and more complete - was published when the translation was almost completed. We must, however, note that the work of the French sirologist, based in a very large part solely on the data of Wright's book, with all its undeniable merits, can in no way replace the latter. It lacks the liveliness of an English work, and the indications are not always distinguished by that pedantic precision which is most dear and desirable in a scientific work (see, for example, our remarks on p. 39, 49, 79, 82, 131, 135, 143, 152). Then, it does not hurt to remember that, with the exception of its comparative completeness in some parts, Duval's French work essentially differs very little from Wright's: in both works we have not a history of literature in the real sense of the word, but nothing more than reference books on Syriac literature.

Duval's French work, which appeared about three years ago in the series Bibliotheque de I Enseignement de I Histoire ecclesiastique (II volume of Anciennes Litteratures Chretiennes; 1st ed. published in 1899, 2nd in 1900), - a work more extensive in volume and therefore naturally in many departments and more complete - was published when the translation was almost completed. We must, however, note that the work of the French sirologist, based in a very large part solely on the data of Wright's book, with all its undeniable merits, can in no way replace the latter. It lacks the liveliness of an English work, and the indications are not always distinguished by that pedantic precision which is most dear and desirable in a scientific work (see, for example, our remarks on p. 39, 49, 79, 82, 131, 135, 143, 152). Then, it does not hurt to remember that, with the exception of its comparative completeness in some parts, Duval's French work essentially differs very little from Wright's: in both works we have not a history of literature in the real sense of the word, but nothing more than reference books on Syriac literature.

This translation is based on a separate edition of 1894, already greatly supplemented by its English publisher (McLean) in comparison with the original text of 1887. The unusually rapid growth of specialized literature during the last seven years, in connection with various manuscript finds in the East, demanded, however, a number of new additions, without which the Russian translation, at its very appearance, could in many ways be outdated. In these types, on the one hand, we reviewed all the relevant latest scientific literature, on the other hand, we made a complete comparison of Wright's text (edition 1894 d.) with data from the French work of Duval (according to the 1900 edition). The latter was of great help to us in general, but for the reason indicated earlier he could not save us from further inquiries. All dubious dates, quotations, references, etc., had to be checked against sources as far as possible.

(Fragment)

This work has not yet been translated into text format.

This book does not belong to the popular science genre, although it was first published in 1982 by the publishing house "Wydawnictwo Artystyczne i Filmowe" as part of the popular series "Mythologies of the World". A. Geishtor did not seek to make his work accessible to a wide range of readers and acquaint them with the already existing achievements in the study of Slavic mythology, but made an original attempt at a new interpretation of the archaic cults and cultures that existed among the Slavs before they adopted Christianity. For this purpose, he used not only the traditional techniques of the historian and archaeologist, but also the research methods of cultural anthropology, the achievements of descriptive ethnography, the experience of linguistics and the theoretical models of comparative religion. nine0011

This book does not belong to the popular science genre, although it was first published in 1982 by the publishing house "Wydawnictwo Artystyczne i Filmowe" as part of the popular series "Mythologies of the World". A. Geishtor did not seek to make his work accessible to a wide range of readers and acquaint them with the already existing achievements in the study of Slavic mythology, but made an original attempt at a new interpretation of the archaic cults and cultures that existed among the Slavs before they adopted Christianity. For this purpose, he used not only the traditional techniques of the historian and archaeologist, but also the research methods of cultural anthropology, the achievements of descriptive ethnography, the experience of linguistics and the theoretical models of comparative religion. nine0011  And this work has become extremely popular! Within a few years, two hundred thousand copies of this book were sold (in 1982 and in 1986).

And this work has become extremely popular! Within a few years, two hundred thousand copies of this book were sold (in 1982 and in 1986).  Aneta Penyondz. After the death of A. Geishtor, she put his handwritten heritage in order and found papers that made it possible to provide the "Mythology of the Slavs" with footnotes, which the Author had previously prepared with the idea of a German edition. As a result, we received the work of the great historian in a complete, unabridged version. One can hope that in this form he will wait for translations and take an honorable place in world science.

Aneta Penyondz. After the death of A. Geishtor, she put his handwritten heritage in order and found papers that made it possible to provide the "Mythology of the Slavs" with footnotes, which the Author had previously prepared with the idea of a German edition. As a result, we received the work of the great historian in a complete, unabridged version. One can hope that in this form he will wait for translations and take an honorable place in world science.  nine0011

nine0011  Geishtor possessed the courage necessary for a scientist, which was required in order to follow the unbeaten path. All this allowed him to start writing an interdisciplinary study that combined the problems and methods of a medievalist historian and an ethnologist. The greatest value of his work is the consideration of the Slavic folk culture that is still visible today, captured and described by ethnographers of the past, as a historical source that can and should be compared with written sources of eight hundred and thousand years ago, pointing to their similar, albeit separated by time, content. nine0011

Geishtor possessed the courage necessary for a scientist, which was required in order to follow the unbeaten path. All this allowed him to start writing an interdisciplinary study that combined the problems and methods of a medievalist historian and an ethnologist. The greatest value of his work is the consideration of the Slavic folk culture that is still visible today, captured and described by ethnographers of the past, as a historical source that can and should be compared with written sources of eight hundred and thousand years ago, pointing to their similar, albeit separated by time, content. nine0011  All these beliefs and practices drawn from historical sources can be written down in one volume of texts, the completion of which cannot be expected [...]. Also, the possibilities of archaeological data that expand our knowledge of places and objects of worship still remain inexhaustible. But the main hope for enriching our research possibilities comes from popular culture; this still existing relic of social consciousness”[1]. nine0011

All these beliefs and practices drawn from historical sources can be written down in one volume of texts, the completion of which cannot be expected [...]. Also, the possibilities of archaeological data that expand our knowledge of places and objects of worship still remain inexhaustible. But the main hope for enriching our research possibilities comes from popular culture; this still existing relic of social consciousness”[1]. nine0011  Saxo dotted the "i", seeing in this rite a wish for a more plentiful harvest for the next year. A. Geishtor without hesitation compared the description of the XII century. with a church custom noted by ethnographers in the Bulgarian village of the 20th century. During the feast in honor of the local saint, the priest “stands behind a pile of sacrificial bread and asks loudly: “Do you see me?” To which they answered: “Yes, we see you, we see you.” Then the priest would say, “So that next year you won’t be able to see me completely,” in the hope that the harvest will be even more plentiful”[2]. nine0011

Saxo dotted the "i", seeing in this rite a wish for a more plentiful harvest for the next year. A. Geishtor without hesitation compared the description of the XII century. with a church custom noted by ethnographers in the Bulgarian village of the 20th century. During the feast in honor of the local saint, the priest “stands behind a pile of sacrificial bread and asks loudly: “Do you see me?” To which they answered: “Yes, we see you, we see you.” Then the priest would say, “So that next year you won’t be able to see me completely,” in the hope that the harvest will be even more plentiful”[2]. nine0011  It should be noted that such logic removed the taboo established by the rigorists of positivist historiography, for whom the comparison of historical evidence so different in nature and time was an unacceptable anachronism. The break with the axiom of synchronicity has become the initial principle of interdisciplinary research, combining the perspectives of historiography and cultural anthropology. But we are talking about something more than just differences between arbitrary interpretations that define research positions. A fundamental difference in the understanding of historical time in different historical schools comes into play. nine0011

It should be noted that such logic removed the taboo established by the rigorists of positivist historiography, for whom the comparison of historical evidence so different in nature and time was an unacceptable anachronism. The break with the axiom of synchronicity has become the initial principle of interdisciplinary research, combining the perspectives of historiography and cultural anthropology. But we are talking about something more than just differences between arbitrary interpretations that define research positions. A fundamental difference in the understanding of historical time in different historical schools comes into play. nine0011  However, imaginary methodological remorse turns out to be a reflection of the culture of the 20th century. ideas about time and social change. Historians with a positivist orientation have been especially sensitive to the question of limiting research horizons. A. Geishtor overcame their methodological limitations and opened up new research perspectives. In his work, he used the concepts of a new understanding of time (“time of great duration”) and social change, which are characteristic of modern historiography and cultural anthropology, in his work. On this basis, a new methodological imperative could appear, which I took the liberty of formulating as follows: evidence from sources that differ in time and space can and should be considered together if we are dealing with a similar anthropological situation in them[4]. nine0011

However, imaginary methodological remorse turns out to be a reflection of the culture of the 20th century. ideas about time and social change. Historians with a positivist orientation have been especially sensitive to the question of limiting research horizons. A. Geishtor overcame their methodological limitations and opened up new research perspectives. In his work, he used the concepts of a new understanding of time (“time of great duration”) and social change, which are characteristic of modern historiography and cultural anthropology, in his work. On this basis, a new methodological imperative could appear, which I took the liberty of formulating as follows: evidence from sources that differ in time and space can and should be considered together if we are dealing with a similar anthropological situation in them[4]. nine0011  At the end of his reflections on the long process of the displacement of paganism by Christianity, A. Geishtor noted: “...Slavic folklore, despite the existence of syncretic plots in it [...] almost to the present day has retained the original basis of the traditional view of the world and its sacred reflection "[five]. This is how the final words of the "Mythology of the Slavs" sound. They can be seen, despite the fact that they were spoken a quarter of a century ago, the last word of the humanities in this particular area of research and a call for the study of the past in modern culture. nine0011

At the end of his reflections on the long process of the displacement of paganism by Christianity, A. Geishtor noted: “...Slavic folklore, despite the existence of syncretic plots in it [...] almost to the present day has retained the original basis of the traditional view of the world and its sacred reflection "[five]. This is how the final words of the "Mythology of the Slavs" sound. They can be seen, despite the fact that they were spoken a quarter of a century ago, the last word of the humanities in this particular area of research and a call for the study of the past in modern culture. nine0011  Interdisciplinary research should be the basis of our encounters with each other, giving us the opportunity to share knowledge and transcend the boundaries of our disciplines. It is to such a meeting that the last book of A. Geishtor paves the way. nine0011

Interdisciplinary research should be the basis of our encounters with each other, giving us the opportunity to share knowledge and transcend the boundaries of our disciplines. It is to such a meeting that the last book of A. Geishtor paves the way. nine0011