Story of jack

The Story of Jack and the Beanstalk

Old English Fairy Tale - version written and illustrated by Leanne Guenther

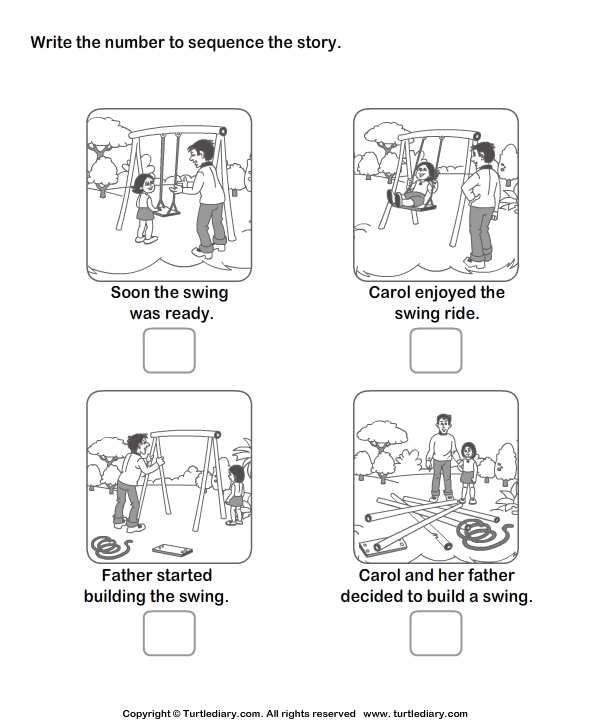

Once upon a time, there lived a widow woman and her son, Jack, on their small farm in the country.

Every day, Jack would help his mother with the chores - chopping the wood, weeding the garden and milking the cow. But despite all their hard work, Jack and his mother were very poor with barely enough money to keep themselves fed.

"What shall we do, what shall we do?" said the widow, one spring day. "We don't have enough money to buy seed for the farm this year! We must sell our cow, Old Bess, and with the money buy enough seed to plant a good crop."

"All right, mother," said Jack, "it's market-day today. I'll go into town and sell Bessy."

So Jack took the cow's halter in his hand, walked through the garden gate and headed off toward town. He hadn't gone far when he met a funny-looking, old man who said to him, "Good morning,

Jack. "

"Good morning to you," said Jack, wondering how the little, old man knew his name.

"Where are you off to this fine morning?" asked the man.

"I'm going to market to sell our cow, Bessy."

"Well what a helpful son you are!" exclaimed the man, "I have a special deal for such a good boy like you."

The little, old man looked around to make sure no one was watching and then opened his hand to show Jack what he held.

"Beans?" asked Jack, looking a little confused.

"Three magical bean seeds to be exact, young man. One, two, three! So magical are they, that if you plant them over-night, by morning they grow right up to the sky," promised the funny little man. "And because you're such a good boy, they're all yours in trade for that old milking cow."

"Really?" said Jack, "and you're quite sure they're magical?"

"I am indeed! And if it doesn't turn out to be true you can have your cow back. "

"

"Well that sounds fair," said Jack, as he handed over Bessy's halter, pocketed the beans and headed back home to show his mother.

"Back already, Jack?" asked his mother; "I see you haven't got Old Bess -- you've sold her so quickly. How much did you get for her?"

Jack smiled and reached into his pocket, "Just look at these beans, mother; they're magical, plant them over-night and----"

"What!" cried Jack's mother. "Oh, silly boy! How could you give away our milking cow for three measly beans." And with that she did the worst thing Jack had ever seen her do - she burst into tears.

Jack ran upstairs to his little room in the attic, so sorry he was, and threw the beans angrily out the window thinking, "How could I have been so foolish - I've broken my mother's heart." After much tossing and turning, at last Jack dropped off to sleep.

When Jack woke up the next morning, his room looked strange. The sun was shining into part of it like it normally did, and yet all the rest was quite dark and shady. So Jack jumped up and

dressed himself and went to the window. And what do you think he saw? Why, the beans he had thrown out of the window into the garden had sprung up into a big beanstalk which went up and up and

up until it reached the sky.

The sun was shining into part of it like it normally did, and yet all the rest was quite dark and shady. So Jack jumped up and

dressed himself and went to the window. And what do you think he saw? Why, the beans he had thrown out of the window into the garden had sprung up into a big beanstalk which went up and up and

up until it reached the sky.

Using the leaves and twisty vines like the rungs of a ladder, Jack climbed and climbed until at last, he reached the sky. And when he got there he found a long, broad road winding its way through the clouds to a tall, square castle off in the distance.

Jack ran up the road toward the castle and just as he reached it, the door swung open to reveal a horrible lady giant, with one great eye in the middle of her forehead.

As soon as Jack saw her he turned to run away, but she caught him, and dragged him into the castle.

"Don't be in such a hurry, I'm sure a growing boy like you would like a nice, big breakfast," said the great, big, tall woman, "It's been so long since I got to make breakfast for a boy. "

"

Well, the lady giant wasn't such a bad sort, after all -- even if she was a bit odd. She took Jack into the kitchen, and gave him a chunk of cheese and a glass of milk. But Jack had only taken a few bites when thump! thump! thump! the whole house began to tremble with the noise of someone coming.

"Goodness gracious me! It's my husband," said the giant woman, wringing her hands, "what on earth shall I do? There's nothing he likes better than boys broiled on toast and I haven't any bread left. Oh dear, I never should have let you stay for breakfast. Here, come quick and jump in here." And she hurried Jack into a large copper pot sitting beside the stove just as her husband, the giant, came in.

He ducked inside the kitchen and said, "I'm ready for my breakfast -- I'm so hungry I could eat three cows. Ah, what's this I smell?

Fee-fi-fo-fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman,

Be he alive, or be he dead

I'll have his bones to grind my bread.

"Nonsense, dear," said his wife, "we haven't had a boy for breakfast in years. Now you go and wash up and by the time you come back your breakfast'll be ready for you."

So the giant went off to tidy up -- Jack was about to make a run for it when the woman stopped him. "Wait until he's asleep," she said, "he always has a little snooze after breakfast."

Jack peeked out of the copper pot just as the giant returned to the kitchen carrying a basket filled with golden eggs and a sickly-looking, white hen. The giant poked the hen and growled, "Lay" and the hen laid an egg made of gold which the giant added to the basket.

After his breakfast, the giant went to the closet and pulled out a golden harp with the face of a sad, young girl. The giant poked the harp and growled, "Play" and the harp began to play

a gentle tune while her lovely face sang a lullaby. Then the giant began to nod his head and to snore until the house shook.

When he was quite sure the giant was asleep, Jack crept out of the copper pot and began to tiptoe out of the kitchen. Just as he was about to leave, he heard the sound of the harp-girl weeping. Jack bit his lip, sighed and returned to the kitchen. He grabbed the sickly hen and the singing harp, and began to tiptoe back out. But this time the hen gave a cackle which woke the giant, and just as Jack got out of the house he heard him calling, "Wife, wife, what have you done with my white hen and my golden harp?"

Jack ran as fast as he could and the giant, realizing he had been tricked, came rushing after - away from the castle and down the broad, winding road. When he got to the beanstalk the giant was only twenty yards away when suddenly he saw Jack disappear - confused, the giant peered through the clouds and saw Jack underneath climbing down for dear life. The giant stomped his foot and roared angrily.

Fee-fi-fo-fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman,

Be he alive, or be he dead

I'll have his bones to grind my bread.

The giant swung himself down onto the beanstalk which shook with his weight. Jack slipped, slid and climbed down the beanstalk as quickly as he could, and after him climbed the giant.

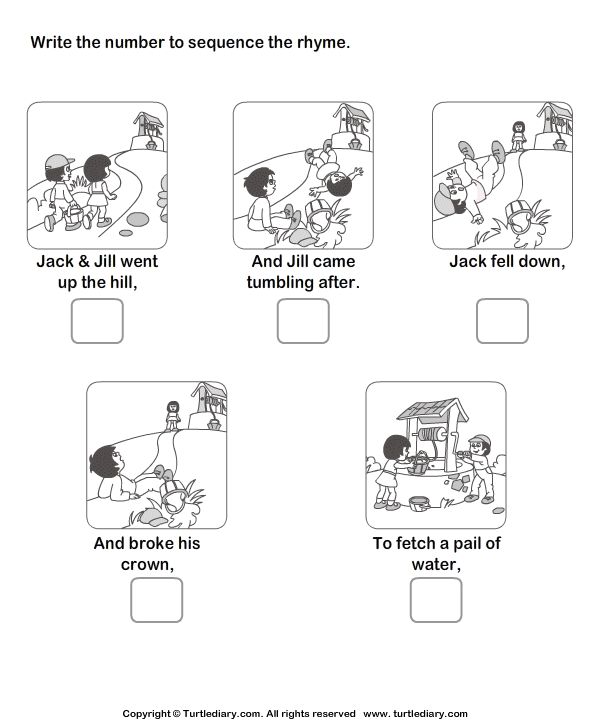

As he neared the bottom, Jack called out, "Mother! Please! Hurry, bring me an axe, bring me an axe." And his mother came rushing out with Jack's wood chopping axe in her hand, but when she came to the enormous beanstalk she stood stock still with fright.

Jack jumped down, got hold of the axe and began to chop away at the beanstalk. Luckily, because of all the chores he'd done over the years, he'd become quite good at chopping and it didn't

take long for him to chop through enough of the beanstalk that it began to teeter. The giant felt the beanstalk shake and quiver so he stopped to see what was the matter. Then Jack gave one

last big chop with the axe, and the beanstalk began to topple over. Then the giant fell down and broke his crown, and the beanstalk came toppling after.

The singing harp thanked Jack for rescuing her from the giant - she had hated being locked up in the closet all day and night and wanted nothing more than to sit in the farmhouse window and sing to the birds and the butterflies in the sunshine.

With a bit of patience and his mother's help, it didn't take long for Jack to get the sickly hen back in good health and the grateful hen continued to lay a fresh golden egg every day.

Jack used the money from selling the golden eggs to buy back Old Bess, purchase seed for the spring crop and to fix up his mother's farm. He even had enough left over to invite every one of his neighbours over for a nice meal, complete with music from the singing harp.

And so Jack, his mother, Old Bess, the golden harp and the white hen lived happy ever after.

Printable version of this story

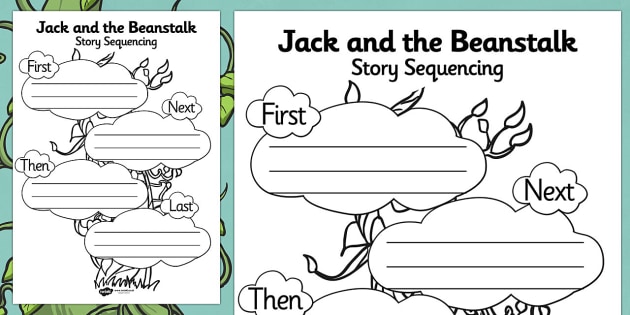

Templates:

- Close the template window after printing to return to this screen.

- Set page margins to zero if you have trouble fitting the template on one page (FILE, PAGE SETUP or FILE, PRINTER SETUP in most browsers).

Template Page 1 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 2 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 3 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 4 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 5 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 6 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 7 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 8 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 9 (color) or (B&W)

Jack and the Beanstalk - Storynory

seek 00.00.00 00.00.00 loading- Download

Download the audio

Pictures by Sophie Green

There was once upon a time a poor widow who had an only son named Jack, and a cow named Milky-White. All they had to live on was the milk the cow gave every morning, which they carried to the market and sold - until one morning Milky-White gave no milk.

All they had to live on was the milk the cow gave every morning, which they carried to the market and sold - until one morning Milky-White gave no milk.

“What shall we do, what shall we do?” said the widow, wringing her hands.

“Cheer up mother, I’ll go and get work somewhere,” said Jack.

“We’ve tried that before, and nobody would take you,” said his mother. “We must sell Milky-White and with the money, start a shop or something.”

“Alright, mother,” said Jack. “It’s market day today, and I’ll soon sell Milky-White, and then we’ll see what we can do.”

So he took the cow, and off he started. He hadn’t gone far when he met a funny looking old man, who said to him, “Good morning, Jack.”

“Good morning to you,” said Jack, and wondered how he knew his name.

“Well Jack, where are you off to?” Said the man.

“I’m going to market to sell our cow there.”

“Oh, you look the proper sort of chap to sell cows,” said the man. “I wonder if you know how many beans make five. ”

”

“Two in each hand and one in your mouth,” said Jack, as sharp as a needle.

“Right you are,” says the man, “and here they are, the very beans themselves,” he went on, pulling out of his pocket a number of strange looking beans. “As you are so sharp,” said he, “I don’t mind doing a swap with you — your cow for these beans.”

“Go along,” said Jack. “You take me for a fool!”

“Ah! You don’t know what these beans are,” said the man. “If you plant them overnight, by morning they grow right up to the sky.”

“Really?” said Jack. “You don’t say so.”

“Yes, that is so. If it doesn’t turn out to be true you can have your cow back.”

“Right,” said Jack, and handed him over Milky-White, then pocketed the beans.

Back home goes Jack and says to his mother, “You’ll never guess mother what I got for Milky-White.”

His mother became very excited, “Five pounds? Ten? Fifteen? No, it can’t be twenty.”

“I told you that you couldn’t guess. What do you say to these beans? They’re magical. Plant them overnight and — ”

Plant them overnight and — ”

“What!” Exclaimed Jack’s mother. “Have you been such a fool, such a dolt, such an idiot? Take that! Take that! Take that! As for your precious beans, here they go out of the window. Now off with you to bed. Not a sup shall you drink, and not a bit shall you swallow this very night.”

So Jack went upstairs to his little room in the attic, sad and sorry he was, to be sure. At last he dropped off to sleep.

When he woke up, the room looked so funny. The sun was shining into part of it, and yet all the rest was quite dark and shady. Jack jumped up and went to the window. What do you think he saw? Why, the beans his mother had thrown out of the window into the garden had sprung up into a giant beanstalk which went up and up and up until it reached the sky. So the man spoke truth after all!

The beanstalk grew up quite close past Jack’s window, so all he had to do was to open it and give a jump onto the beanstalk which ran up just like a big ladder. So Jack climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and he climbed until at last he reached the sky. When he got there he found a long broad road going as straight as a dart. So he walked along, and walked along, and he walked along until he came to a great big tall house, and on the doorstep there was a great big tall woman.

So Jack climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and he climbed until at last he reached the sky. When he got there he found a long broad road going as straight as a dart. So he walked along, and walked along, and he walked along until he came to a great big tall house, and on the doorstep there was a great big tall woman.

“Good morning, ma’am,” said Jack, quite politely. “Could you be so kind as to give me some breakfast?” For he was as hungry as a hunter.

“It’s breakfast you want, is it?” said the great big tall woman. “It’s breakfast you’ll be if you don’t move off from here. My man is an ogre and there’s nothing he likes better than boys boiled on toast. You’d better be moving on or he’ll be coming.”

“Oh! please mum, do give me something to eat, mum. I’ve had nothing to eat since yesterday morning, really and truly, mum,” said Jack. “I may as well be boiled as die of hunger.”

Well, the ogre’s wife was not half so bad after all, so she took Jack into the kitchen, and gave him a hunk of bread and cheese and a jug of milk. Jack hadn’t half finished these when thump, thump, thump! The whole house began to tremble with the noise of someone coming.

Jack hadn’t half finished these when thump, thump, thump! The whole house began to tremble with the noise of someone coming.

“Goodness gracious me! It’s my old man,” said the ogre’s wife. “What on earth shall I do? Come along quick and jump in here.” She bundled Jack into the oven just as the ogre came in. He was a big one, to be sure. At his belt he had three calves strung up by the heels, and he unhooked them and threw them down onto the table and said:

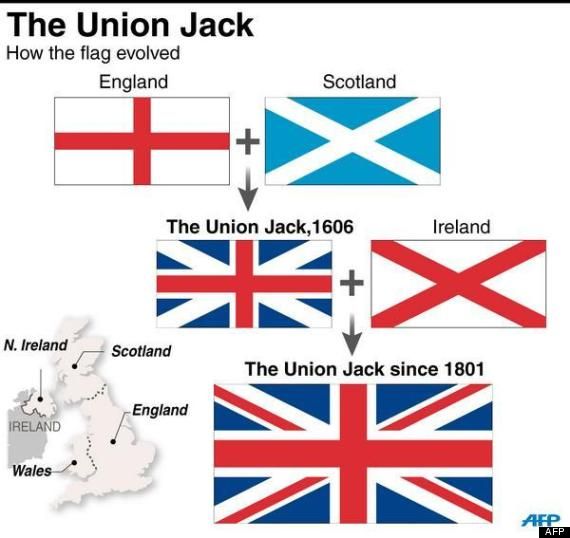

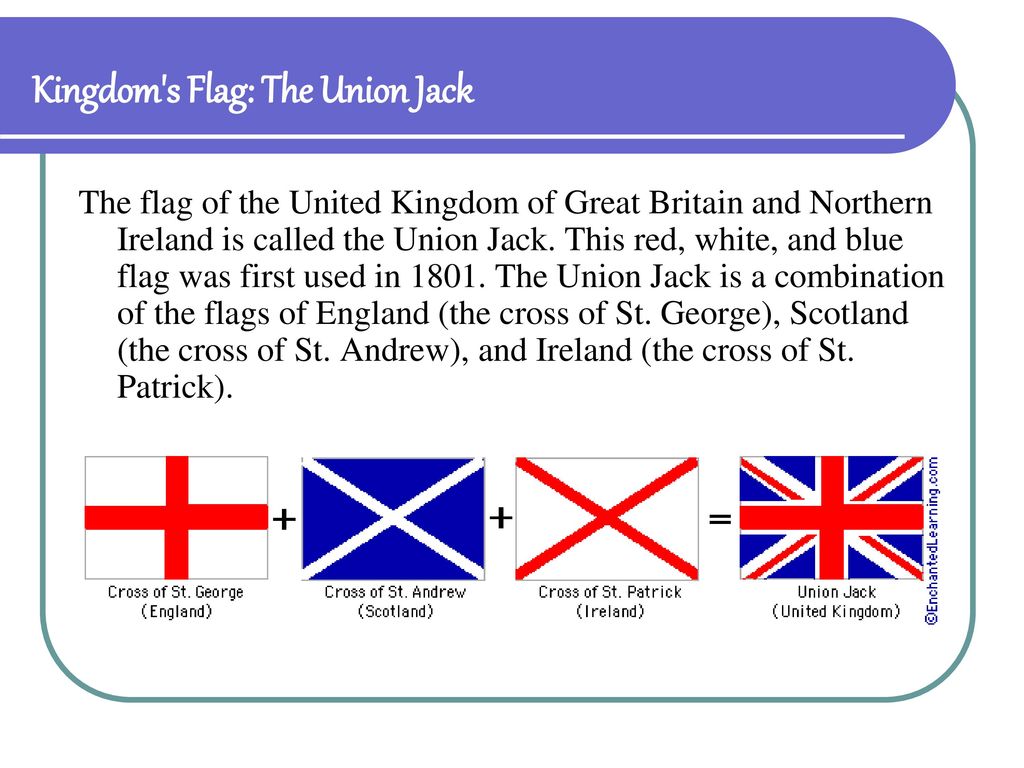

"Fee-fi-fo-fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman,

Be he alive, or be he dead,

I’ll have his bones to grind my bread."

“Nonsense, dear,” said his wife. “You’re dreaming. Or perhaps you smell the scraps of that little boy you liked so much for yesterday’s dinner. Here you go, and have a wash and tidy up. By the time you come back your breakfast’ll be ready for you.”

So off the ogre went, and Jack was just going to jump out of the oven and run away when the woman told him, “Wait till he’s asleep. He always has a doze after breakfast. ” Well, the ogre had his breakfast, and after that he went to a big chest and took out a couple of bags of gold, and down he sat and counted until at last his head began to nod and he began to snore until the whole house shook again.

” Well, the ogre had his breakfast, and after that he went to a big chest and took out a couple of bags of gold, and down he sat and counted until at last his head began to nod and he began to snore until the whole house shook again.

Jack then crept out on tip-toe from the oven, and as he was passing the ogre, he took one of the bags of gold from under his arm, and off he peltered until he came to the beanstalk, and then he threw down the bag of gold, which of course fell into his mother’s garden. He climbed down and down until at last he got home and told his mother and showed her the gold and said, “Well, mother, wasn’t I right about the beans? They are really magical, you see.”

So they lived on the bag of gold for some time, until at last they came to the end of it, and Jack made up his mind to try his luck once more at the top of the beanstalk. So one fine morning he rose up early, and got onto the beanstalk, and he climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and he climbed until at last he came out onto the road again and up to the great tall house he had been to before. There, sure enough, was the great tall woman a-standing on the doorstep.

There, sure enough, was the great tall woman a-standing on the doorstep.

“Good morning, mum,” said Jack, as bold as brass, “could you be so good as to give me something to eat?”

“Go away, my boy,” said the big tall woman, “or else my man will eat you up for breakfast. Aren’t you the youngster who came here once before? Do you know, that very day my man missed one of his bags of gold.”

“That’s strange, mum,” said Jack, “I dare say I could tell you something about that, but I’m so hungry I can’t speak until I’ve had something to eat.”

Well, the big tall woman was so curious that she took him in and gave him something to eat. He had scarcely begun munching it as slowly as he could when thump! thump! They heard the giant’s footstep, and his wife hid Jack away in the oven.

All happened as it did before. In came the ogre as he did before, said, “Fee-fi-fo-fum,” and had his breakfast off three boiled oxen.

Then he said, “Wife, the hen that lays the golden eggs. ” So she brought it, and the ogre said, “Lay,” and it laid an egg all of gold. Then the ogre began to nod his head, and to snore until the house shook. Jack crept out of the oven on tip-toe and caught hold of the golden hen, and was off before you could say “Jack Robinson.” This time the hen gave a cackle which woke the ogre, and just as Jack got out of the house he heard him calling, “Wife, wife, what have you done with my golden hen?”

” So she brought it, and the ogre said, “Lay,” and it laid an egg all of gold. Then the ogre began to nod his head, and to snore until the house shook. Jack crept out of the oven on tip-toe and caught hold of the golden hen, and was off before you could say “Jack Robinson.” This time the hen gave a cackle which woke the ogre, and just as Jack got out of the house he heard him calling, “Wife, wife, what have you done with my golden hen?”

The wife said, “Why, my dear?” But that was all Jack heard, for he rushed off to the beanstalk and climbed down like a house on fire. When he got home he showed his mother the wonderful hen, and said “Lay” to it; and it laid a golden egg every time he said “Lay.”

Well it wasn’t long before that Jack made up his mind to have another try at his luck up there at the top of the beanstalk. One fine morning he rose up early and got to the beanstalk, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and he climbed until he got to the top.

This time he knew better than to go straight to the ogre’s house. When he got near it, he waited behind a bush until he saw the ogre’s wife come out with a pail to get some water, and then he crept into the house and got into a big copper pot. He hadn’t been there long when he heard thump, thump, thump! As before, and in came the ogre and his wife.

When he got near it, he waited behind a bush until he saw the ogre’s wife come out with a pail to get some water, and then he crept into the house and got into a big copper pot. He hadn’t been there long when he heard thump, thump, thump! As before, and in came the ogre and his wife.

“Fee-fi-fo-fum, I smell the blood of an Englishman,” cried out the ogre. “I smell him, wife, I smell him.”

“Do you, my dearie?” said the ogre’s wife. “Then, if it’s that little rogue that stole your gold and the hen that laid the golden eggs he’s sure to have gotten into the oven.” And they both rushed to the oven.

Jack wasn’t there, luckily. So the ogre sat down to the breakfast and ate it, but every now and then he would mutter, “Well, I could have sworn –” and he’d get up and search the larder and the cupboards and everything, only, luckily, he didn’t think of the copper pot.

After breakfast was over, the ogre called out, “Wife, wife, bring me my golden harp.” So she brought it and put it on the table before him. Then he said, “Sing!” The golden harp sang most beautifully. It went on singing until the ogre fell asleep, and commenced to snore like thunder.

Then he said, “Sing!” The golden harp sang most beautifully. It went on singing until the ogre fell asleep, and commenced to snore like thunder.

Then Jack lifted up the copper lid very quietly and got down like a mouse and crept on hands and knees until he came to the table, when up he crawled, caught hold of the golden harp and dashed with it towards the door. But the harp called out quite loudly, “Master! Master!” The ogre woke up just in time to see Jack running off with his harp.

Jack ran as fast as he could, and the ogre came rushing after, and would soon have caught him, only Jack had a start and dodged him a bit and knew where he was going. When he got to the beanstalk the ogre was not more than twenty yards away when suddenly he saw Jack disappear. When he came to the end of the road he saw Jack underneath climbing down for dear life. Well, the ogre didn’t like trusting himself to such a ladder, and he stood and waited, so Jack got another start.

Just then the harp cried out, “Master! Master!” and the ogre swung himself down onto the beanstalk, which shook with his weight. Down climbed Jack, and after him climbed the ogre. By this time Jack had climbed down, and climbed down, and climbed down until he was very nearly home. So he called out, “Mother! Mother! Bring me an axe, bring me an axe!” His mother came rushing out with the axe in her hand, but when she came to the beanstalk she stood stuck still with fright, for there she saw the ogre with his legs just through the clouds.

Down climbed Jack, and after him climbed the ogre. By this time Jack had climbed down, and climbed down, and climbed down until he was very nearly home. So he called out, “Mother! Mother! Bring me an axe, bring me an axe!” His mother came rushing out with the axe in her hand, but when she came to the beanstalk she stood stuck still with fright, for there she saw the ogre with his legs just through the clouds.

Jack jumped down and took hold of the axe and gave a chop at the beanstalk which cut it half in two. The ogre felt the beanstalk shake and quiver, so he stopped to see what was the matter. Then Jack gave another chop with the axe, and the beanstalk was cut in two and began to topple over. Then the ogre fell down and broke his crown, and the beanstalk came toppling after.

Jack showed his mother his golden harp, and with showing that and selling the golden eggs, Jack and his mother became very rich, and he married a great princess, and they lived happy ever after.

Jack the Ripper: Bloody Legend of London

Backbookmark

0 23027

Photo: shutterstock The working-class districts of Victorian London were not the most cheerful places in the world: poverty, unsanitary conditions, dirt and debauchery reigned there. It was in this atmosphere that one of Britain's most sinister legends, the story of Jack the Ripper, unfolded. The ZagraNitsa portal has collected for you interesting facts and theories about a serial maniac: from Lewis Carroll to a Russian paramedic

It was in this atmosphere that one of Britain's most sinister legends, the story of Jack the Ripper, unfolded. The ZagraNitsa portal has collected for you interesting facts and theories about a serial maniac: from Lewis Carroll to a Russian paramedic

Late 19th century London witnessed many tragedies, both fictional and real. However, the sophisticated fantasy of Oscar Wilde and Arthur Conan Doyle fades against the backdrop of the bloody horror that the capital of Britain experienced in 1888.

There is still no unequivocal answer as to who is actually responsible for the brutal murders in Whitechapel, although literature and cinema are full of different, sometimes very crazy, theories. Let's find out who Jack the Ripper is and why his name even today evokes awe in many Britons. nine0003 Photo: davidhiggerson.wordpress.com

A bit of history

In 1888 the poor parts of London looked like a powder keg: the dominance of immigrants, wholesale drunkenness, poverty, unemployment, prostitution and constant outbreaks of viral diseases. The dissatisfaction of the inhabitants of these godforsaken quarters became so obvious that the inhabitants of rich areas were afraid to show themselves here. The lack of jobs has become one of the reasons for the huge number of prostitutes on the streets of the city: in a year, the police counted 62 brothels, and these are only those that were found. nine0003 Photo: shutterstock

The dissatisfaction of the inhabitants of these godforsaken quarters became so obvious that the inhabitants of rich areas were afraid to show themselves here. The lack of jobs has become one of the reasons for the huge number of prostitutes on the streets of the city: in a year, the police counted 62 brothels, and these are only those that were found. nine0003 Photo: shutterstock

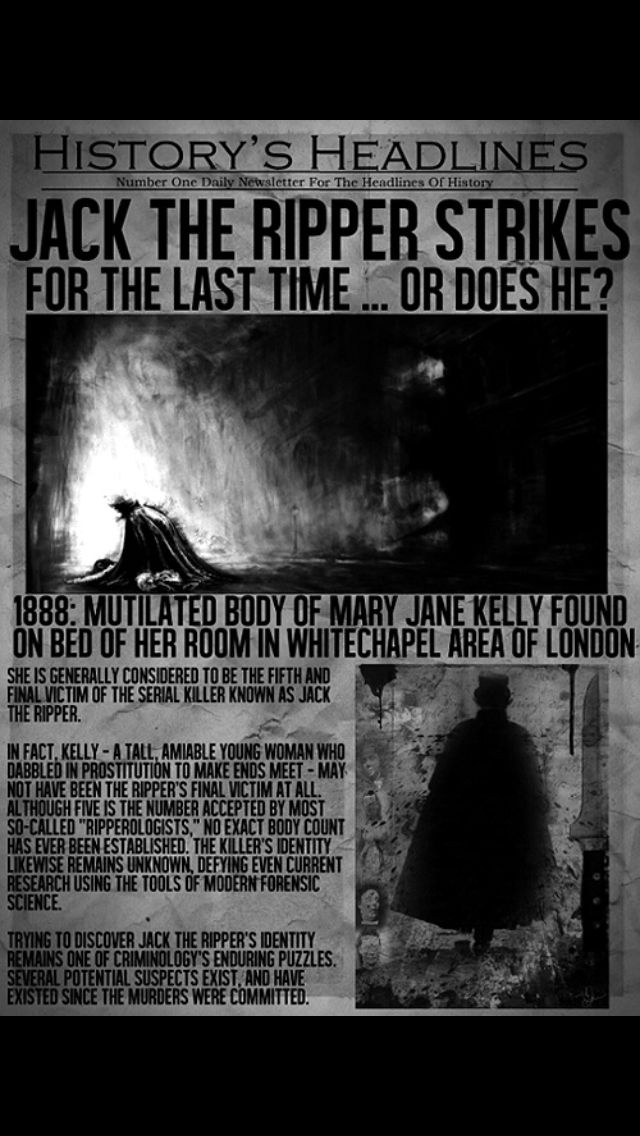

Whitechapel Killer

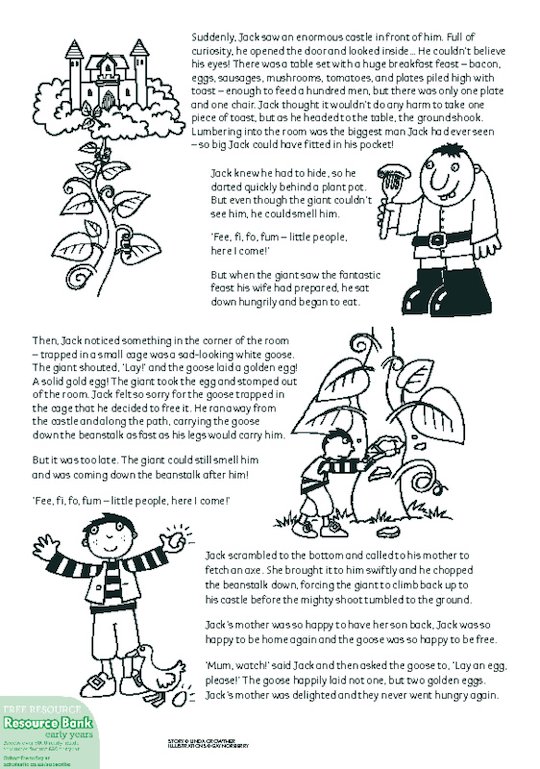

Of course, such an environment could not give rise to anything but cruelty and immorality. In the autumn of 1888, London shuddered from hitherto unseen crimes: a serial maniac not only killed prostitutes, but did it with particular sophistication, removing internal organs from his victims. The killer got his famous nickname thanks to one of the letters to reporters, in which he allegedly confesses to his deed and signs: "Jack the Ripper." However, researchers call this message a fake, of which there were many at that time. nine0003

Different versions attribute from 5 to 15 victims to Jack the Ripper, but most experts believe that there were five of them: everyone was engaged in prostitution, everyone had their throats cut, and three had their internal organs removed. Today they are called "the five canonical victims" of Jack the Ripper. Some researchers add a sixth woman to this list, whose murder, most likely, was also the work of a maniac.

Today they are called "the five canonical victims" of Jack the Ripper. Some researchers add a sixth woman to this list, whose murder, most likely, was also the work of a maniac.

Jack the Ripper was active in the fall of 1888. In addition to the unprecedented brutality, the criminal (or his imitators) was prone to publicity and apparently sought recognition for his activities. From the moment the investigation began, both the police and journalists were literally inundated with letters of confession to their deeds. Of course, most of them were a prank or someone's sick fantasy, but there were several messages among this pile, probably written by the killer's hand. nine0003

From the moment the investigation began, both the police and journalists were literally inundated with letters of confession to their deeds. Of course, most of them were a prank or someone's sick fantasy, but there were several messages among this pile, probably written by the killer's hand. nine0003

The "Dear Boss" letter is famous for giving the maniac his infamous name, Jack the Ripper. Later, the police officially recognized this message as a hoax. The most terrible of the letters is called "From Hell". In addition to bravado and mockery, the sender attached to the letter a box that contained part of a human kidney. The author claimed that he fried and ate the other half.

Photo: whitechapeljack.com nine0012 Photo: whitechapeljack.com Photo: casebook.orgVersions and theories

The impotence of the police, who failed to find and punish the bloody killer, became the basis for a mass of various studies, theories and conjectures. There are even ripperologists - this is what scientists (and not so) men call themselves, to this day trying to figure out the real name of the killer from Whitechapel. nine0003

There are even ripperologists - this is what scientists (and not so) men call themselves, to this day trying to figure out the real name of the killer from Whitechapel. nine0003

1. Polish immigrant

For example, last year the results of DNA tests were published, which were conducted by one of these researchers, Russell Edwards. According to the results, the killer was Aaron Kosminsky, a Polish immigrant who moved to Britain in 1881 and was a suspect in the case. This is indicated by the analysis of a shawl found near one of the victims and bought by businessman Russell Edwards at an auction. DNA samples found on the shawl were compared with the genetic material of the descendants of Aaron, who died in a mental hospital. However, these conclusions cause skepticism among many scientists who call the study amateurish. nine0003 Photo: usvsth4m.com Photo: bbc.com

2. Russian paramedic

Another theory suggests that the offender has Russian roots. This is a certain paramedic Ostrogov, who arrived in London from France, where he left behind not the best memories: he was suspected by the French authorities of the murder of a prostitute. Ostrogov's profession was ideally suited to the theory of the killer's medical education. However, the alleged perpetrator successfully escaped from British justice in St. Petersburg, where he was also convicted and sent to a psychiatric hospital. nine0003 Photo: shutterstock

This is a certain paramedic Ostrogov, who arrived in London from France, where he left behind not the best memories: he was suspected by the French authorities of the murder of a prostitute. Ostrogov's profession was ideally suited to the theory of the killer's medical education. However, the alleged perpetrator successfully escaped from British justice in St. Petersburg, where he was also convicted and sent to a psychiatric hospital. nine0003 Photo: shutterstock

3. Author of Alice in Wonderland

Without a doubt, the most amusing theory is that Jack the Ripper is the famous writer Lewis Carroll. In 1996, researcher Richard Wallis published an entire book on the subject. The author claims that in the works of Carroll, he found anagrams confirming the criminal activities of the writer. Like, if you take a few sentences from Carroll's books and swap the letters, you get a story about the atrocities of the killer from Whitechapel. In fairness, it should be noted that Carroll really had an ambiguous reputation, but it is hard to believe in the brutal murders committed by the author of Alice in Wonderland. nine0003 Photo: telegraph.co.uk Photo: history.com

nine0003 Photo: telegraph.co.uk Photo: history.com

Brand of Jack the Ripper

Dark and bloody legends have always attracted people's attention, and if there is a demand, there will be a supply. Many books and songs have been written about the Whitechapel killer, dozens of films have been shot, there are even several computer games. But Michael Dibdin, a writer who exploits the image of Sherlock Holmes, published a detective story that the famous detective brought Jack the Ripper to clean water: he turned out to be Professor Moriarty. nine0003 Photo: standard.co.uk

In London, there are also daily tours of the places where the maniac committed atrocities. For a two-hour walk you will have to pay 10 pounds. And recently, the Jack the Ripper Museum opened in the capital, causing a wave of protests among activists of the feminist movement.

See also:

More 0 answers comments

"I fried and ate her kidney" Who was and how he killed Jack the Ripper, the most famous and mysterious maniac in history: Society: World: Lenta.

ru

ru Belly ripped open, throat slit - this is how on August 31, 1888, Jack the Ripper, the killer, whose name later became a household name, dealt with his first victim. He, who kept the whole of London in fear, became famous not only for his cruelty, but also for his amazing secrecy. The police never managed to catch him, and only now the researchers were able to lift the veil of secrecy and guess who was hiding under a terrible pseudonym. "Lenta.ru" recalled the bloody story of the most famous maniac in the world. nine0003

In the early hours of 31 August, London cabby Charles Cross was driving through the Whitechapel area. Something dark, lying on the side of the road, caught his attention. Coming closer, Cross realized that he had stumbled upon the still warm corpse of an elderly woman. Her throat had been slashed so that her head was barely holding on, and her stomach was ripped open. The detectives who arrived at the scene found the deceased: she turned out to be an elderly prostitute, Mary Ann Nichols. Last night, she couldn't get 4p for a rooming house, and she was thrown out into the street. nine0003

Last night, she couldn't get 4p for a rooming house, and she was thrown out into the street. nine0003

The matter was put on the brakes: decent people did not enter the poor Whitechapel, the power there belonged to the gangs, and therefore the news of the murder of another prostitute did not impress anyone. A little earlier, the mutilated bodies of Emma Smith and Martha Tabram, also prostitutes, but killed under different circumstances, were found in these slums. The first was subjected to gang rape, and the second was literally cut with a knife. The pathologist counted 39 cut wounds.

Soon, however, the detectives had to return to the disadvantaged area. Not far from the place where Nichols was killed, vagrants found the body of another woman, another prostitute with her stomach ripped open and her throat slit. But something distinguished this murder from the previous one: the woman's intestines were thrown over her shoulders, and an autopsy in the morgue showed that after death the uterus was cut out from the victim. The offender formed his signature "handwriting". nine0003

The offender formed his signature "handwriting". nine0003

The second consecutive brutal murder has caused unrest in the city. It turns out that Scotland Yard has long suspected that a serial killer has wound up in London. It was not only the handwriting - not far from the corpse they found an envelope with a ring and money. The murderer made it clear that he was committing a crime not out of self-interest, but for other motives. Three detective constables were involved in the investigation at once: Frederick Abberline, Henry Moore and Walter Andrews.

The day after the latest murder in Whitechapel, the Star newspaper had a small piece on the front page with a huge headline "Great New Murder in Whitechapel!" Other publications instantly picked up the sensation. Someone spread the rumor that the murders were part of Jewish witchcraft rituals. The fact is that a significant part of the population of the region was made up of Jews - refugees and immigrants who fled from the pogroms that took place in the Russian Empire. London was gripped by similar anti-Semitic unrest. Under public pressure, the police arrested John Peizer, a Polish Jew who was considered a suspect in the first murder. But the man had an ironclad alibi at the time of the commission of both crimes, and he was soon released. nine0003

London was gripped by similar anti-Semitic unrest. Under public pressure, the police arrested John Peizer, a Polish Jew who was considered a suspect in the first murder. But the man had an ironclad alibi at the time of the commission of both crimes, and he was soon released. nine0003

On September 27, the Central News Agency received a letter addressed to the director: “Dear chief! I hear from all sides that they have already seized me, but they cannot take me ... I will not stop cutting them until they catch me. You will hear from me soon." The postscript read: “Hold this letter until I do something else. Then you print. Your Jack the Ripper."

Jack the Ripper murder sites on a map of London

Photo: Public Domain / Wikimedia

Jack did not keep waiting long and three days later, on the night of September 30, he committed another, now double murder, again attacking street prostitutes. The mutilated bodies of Elizabeth Stride and Katherine Eddowes were found quickly. They were on parallel streets, and the medical examiner found that Eddowes had been killed less than 10 minutes before her body was found. The offender was clearly in a hurry and was alarmed. This was indicated by the fact that the damage on Stride's corpse was limited to a cut throat. nine0003

They were on parallel streets, and the medical examiner found that Eddowes had been killed less than 10 minutes before her body was found. The offender was clearly in a hurry and was alarmed. This was indicated by the fact that the damage on Stride's corpse was limited to a cut throat. nine0003

But the second victim was more disfigured than before. Jack disfigured her face, completely removed the intestines and wrapped it around her right shoulder, cut out the kidney. All this took him three to five minutes. Then the maniac fled from possible pursuers along the alleyways, in which he was clearly well versed, managed to wash his hands and a knife in a tank of rainwater, and also wrote a provocative inscription with chalk on the wall of one of the houses: “Jews are not accused of all crimes in vain!” Confirmation of authorship was part of the bloody apron of one of the victims. nine0003

The next morning all the newspapers in London printed the letter of Jack the Ripper and the terrible notes of numerous reporters. The panic that already gripped the city took on paranoid forms. Adding fuel to the fire was a “Postcard of cheeky Jackie”, which was also published the day after the murder. In it, the maniac allowed himself to be sarcastic: “As you can see, I'm not joking. I think you've all heard about my new job. The first managed to squeak, - it was not possible to finish her off with one blow. Thank you for printing the letter, as I asked you. You are my good helpers." But it soon turned out that the investigation had its first witness. A cab driver passing by during one of the murders remembered the general features of the killer: tall, strong build, long brown hair. After that, he lamented that he did not see the face of the Ripper, because on the street, as luck would have it, the lanterns were not lit. nine0003

The panic that already gripped the city took on paranoid forms. Adding fuel to the fire was a “Postcard of cheeky Jackie”, which was also published the day after the murder. In it, the maniac allowed himself to be sarcastic: “As you can see, I'm not joking. I think you've all heard about my new job. The first managed to squeak, - it was not possible to finish her off with one blow. Thank you for printing the letter, as I asked you. You are my good helpers." But it soon turned out that the investigation had its first witness. A cab driver passing by during one of the murders remembered the general features of the killer: tall, strong build, long brown hair. After that, he lamented that he did not see the face of the Ripper, because on the street, as luck would have it, the lanterns were not lit. nine0003

And while prostitutes were afraid to go out, and doctors locked their bags in safes (the pathologist Frederick Brown said that the killer might be a doctor, since you can quickly cut out a kidney in the dark if you only know where it is), the police arranged mass raid on Whitechapel.

The result of the raid was disappointing: several smugglers, pickpockets and robbers fell into the hands of the law. But the Ripper remained at large. The arrests continued. In October 1888 alone, the police interrogated more than two thousand and arrested 80 people. But the investigators did not come close to solving the problem. nine0003

London was waiting for another murder. The tense calm was broken by a letter received on October 15 by George Lusk, a member of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, a group of volunteers who patrolled the area.

The message read: “A letter from Hell. Mr Lusk, sir. I am sending you half of a kidney that I took from one of the women and saved for you. I fried the other half and ate it, it tasted delicious. I'll send you the bloody knife I used to carve her if you wait any longer. Try to stop me, Mr. Lusk." But the signature "Jack the Ripper" was not in the letter, and it was written with numerous errors. Therefore, the falsification was quickly figured out. There were many such attempts to impersonate a maniac, sending letters on his behalf. Probably, some newspapermen tried to raise the sales of their publications in this way. But there were no new murders, so the public calmed down a little. nine0003

There were many such attempts to impersonate a maniac, sending letters on his behalf. Probably, some newspapermen tried to raise the sales of their publications in this way. But there were no new murders, so the public calmed down a little. nine0003

And so, on November 9, 1888, the news of the torn body of another girl again shocked London and the surrounding area. The victim's name was Mary Janet Kelly. A young (unlike the rest of those killed) red-haired Irish prostitute rented a room in a guest house. The hostess saw her for the last time alive. The day before, at two o'clock in the morning, Mary went with some respectable gentleman to her apartment.

Newspaper with the headline “A terrible murder in the East End. Nightmare mutilation of a woman”

Photo: Express Newspapers / Getty Images

The landlady remembered that the man was all in black, with a thick gold chain hanging from his waistcoat, and long brown hair showing from under his hat. The next morning the landlady knocked on Mary's door (she was collecting rent that day), but the lock was not locked. Looking into the room, the hostess screamed in horror and rushed to look for the police. One of the constables, who first arrived on the scene, fainted as soon as he opened the door. The body was mutilated beyond recognition: the chest was cut off, the internal organs were removed and scattered around the room, the face was cut into pieces, the muscles of the thighs were separated from the bones. nine0003

Looking into the room, the hostess screamed in horror and rushed to look for the police. One of the constables, who first arrived on the scene, fainted as soon as he opened the door. The body was mutilated beyond recognition: the chest was cut off, the internal organs were removed and scattered around the room, the face was cut into pieces, the muscles of the thighs were separated from the bones. nine0003

On the same day, the city's police chief, Charles Warren, resigned. Policemen were brought to London from the nearest settlements, because the streets were patrolled around the clock. 143 detectives arrived in the British capital to help colleagues find at least some evidence. But all was in vain. Some law enforcement officers began to count on a new murder - hoping that one day the maniac would be guaranteed to make a mistake. But everything was quiet, and a couple of months later, Scotland Yard issued an official and completely unconvincing statement: Jack the Ripper either committed suicide or went crazy and was locked up in a lunatic asylum for life. nine0003

nine0003

The mystery of the killer's identity still haunts researchers. Already in the 20s of the last century, communities of "ripperologists" began to appear - associations of journalists, historians, detectives and others interested in unraveling the mystery of the Ripper. They collected scattered facts and conspiracy theories. For example, in 1959, the publicist William Le Coue published the book "Things I Know About." The author claimed that in his youth he came to Russia after the February Revolution and became friends with the chairman of the Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky. Therefore, he allowed the journalist to delve into the secret archives. nine0003

There, he came across the diaries of the elder Grigory Rasputin, close to Nicholas II, in which it was written that the real name of Jack the Ripper was Alexander Pedachenko, and he was sent to England by royal intelligence to sabotage the trust of the British in the police. Having completed the task, Pedachenko returned to his native Tver, but was subsequently shot.

This isn't the only crazy theory the Ripperologists have come up with. The Whitechapel murders have been attributed to Vincent van Gogh — they say, the painting “Irises” is actually the outline of the corpse of Mary Kelly — and even to the writer Lewis Carroll. The accusation against the writer of Alice in Wonderland was based on Carroll's similar handwriting to the man who called himself Jack the Ripper in his letters. nine0003

However, it is still unknown whether the killer was the real author of these messages. Fortunately, no one paid much attention to such statements. But when history professor Thomas Stowell put forward his own hypothesis about the identity of the Ripper, there was a real scandal. In 1962, he published an article claiming that the Duke of Clarence, the grandson of Queen Victoria, was responsible for the murders. Confirmation of this Stowell allegedly accidentally discovered in the personal records of the queen's doctor. The duke's crimes were motivated by the birth of a bastard child by a Whitechapel beggar, and to cover up one murder - the murder of a child - five more were committed. nine0003

nine0003

Stowell's information was supported by his authority, so the representatives of Buckingham Palace had to officially refute his words. This only added fuel to the fire. But soon the journalists, who began to check the facts presented in the article, found out that on September 30, 1888 - the day of the double murder - the prince was at his father's birthday party in Scotland. There are many testimonies and confirmations of this.

An interesting study was conducted by forensic scientist Ian Finlay. He studied the genetic material and handwriting from Jack's letters and came to the conclusion that the killer is a woman! Finley even gave a name - Mary Piercy. She was convicted and hanged for the murder of her lover's wife. The girl cut the opponent's throat from ear to ear, which, according to the medical examiner, proves her involvement in the Whitechapel massacre. nine0003

But the two most plausible theories about the identity of the Ripper are related to the names of Sir John Williams and Aaron Kosminsky. The first was a famous London surgeon. Journalist Leonard Mathers suspected him after the killings stopped. He found out that Williams had been practicing for a long time at a clinic on Harley Street, which was located near Whitechapel. He frequently aborted the local prostitutes, wore black, and had a tremendous knowledge of anatomy. Immediately after the last murder, Williams hastily moved to Wales, where he founded the National Library. The surgeon died at 1926 year.

The first was a famous London surgeon. Journalist Leonard Mathers suspected him after the killings stopped. He found out that Williams had been practicing for a long time at a clinic on Harley Street, which was located near Whitechapel. He frequently aborted the local prostitutes, wore black, and had a tremendous knowledge of anatomy. Immediately after the last murder, Williams hastily moved to Wales, where he founded the National Library. The surgeon died at 1926 year.

In 2001, his descendant Tony, studying the archives of his ancestor, found a record that he had an abortion of Mary Kelly, the last victim of a maniac, and all the pages with records for 1888 were torn out, despite the fact that all the rest were preserved in excellent condition. Another proof of the surgeon's guilt was a 30-centimeter surgical knife and fragments of female wombs preserved in alcohol. Tony considers the infertility of Sir John's wife to be the motive for committing the crime. He could take revenge on the prostitutes who asked him to have an abortion for his grief and inability to become a father.