Previewing reading strategy examples

3.3: Reading Strategies - Previewing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 31308

- Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

Pre-reading Strategies

The few minutes you spend preparing BEFORE reading any difficult material can motivate you to read it, as well as increase your ability to understand and remember what you read. Think about it like this: when you are driving to a new place, you would probably look at a map first (or at least turn on your GPS) so you don’t waste time getting lost. Similarly, when you approach a new academic reading, it’s best to use the 4P’s (

purpose, preview, prior knowledge, and predict) so you don’t struggle as much to figure out what the authors want to say or how they plan to say it. Preparing to read can also help you estimate how long you’ll take to read so you can plan your time more efficiently.

Reading Strategy: Previewing

What It Is

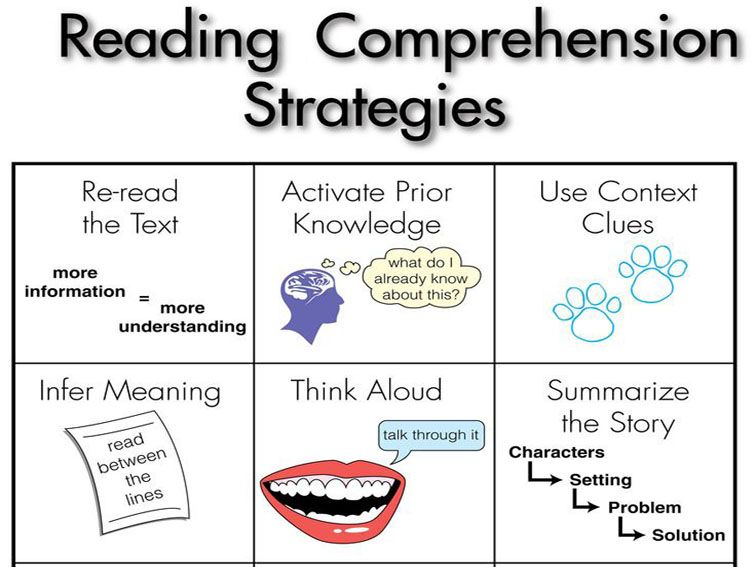

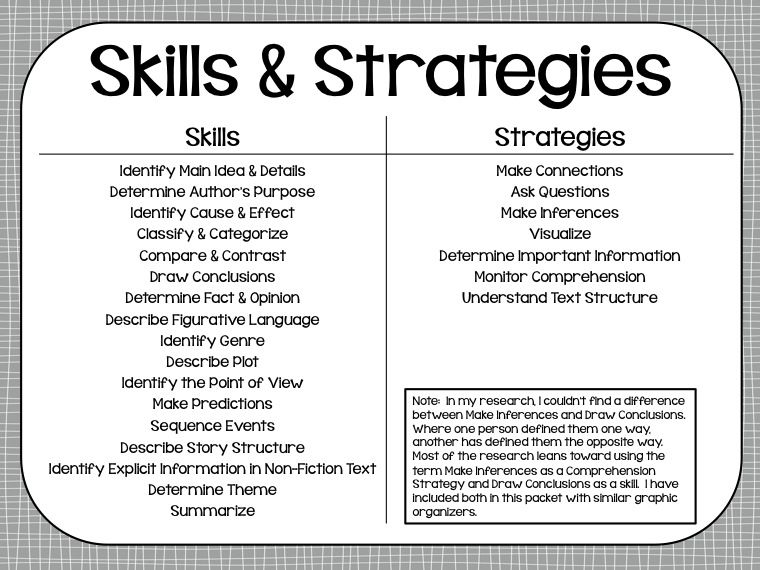

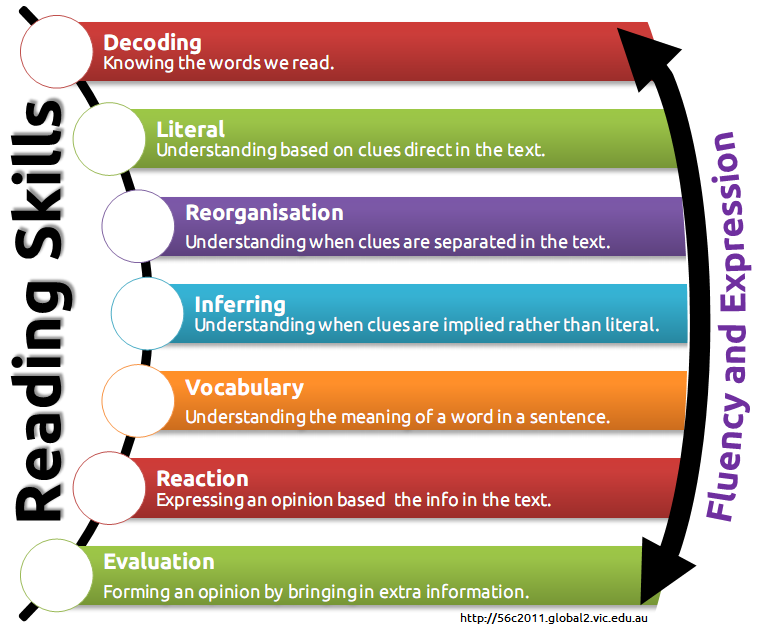

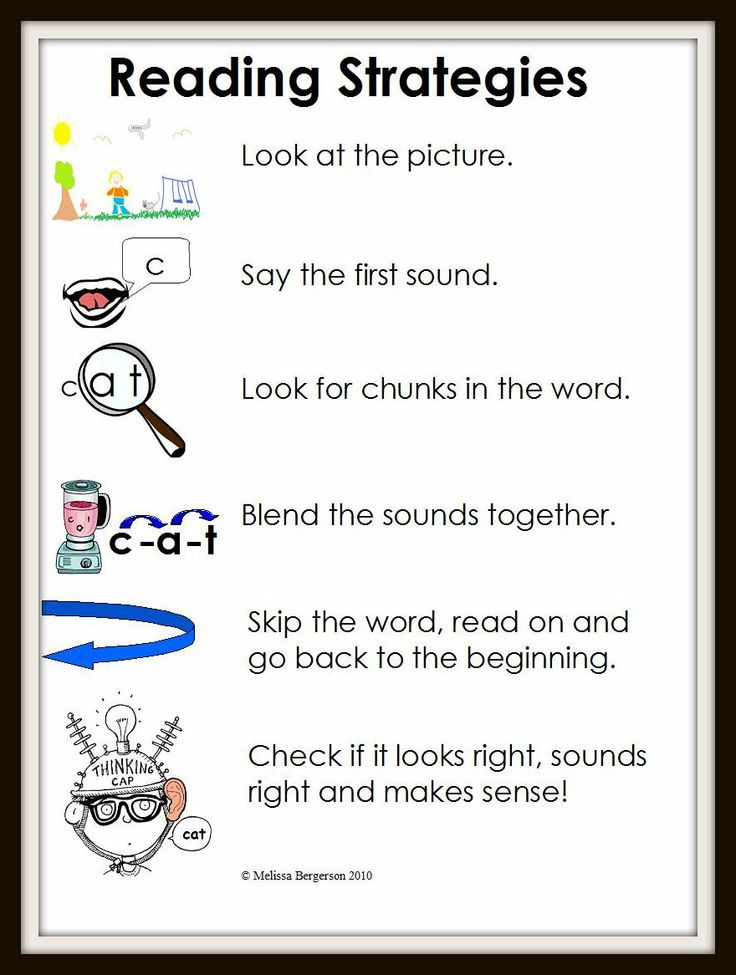

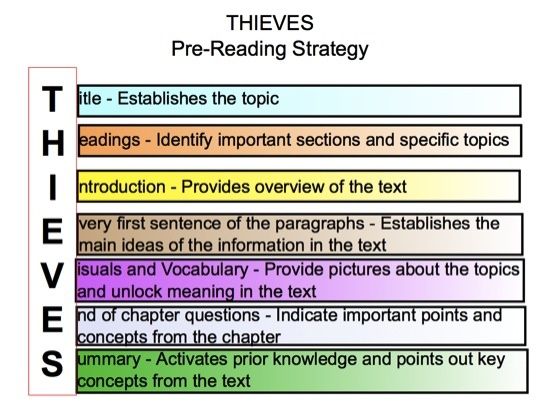

Previewing is a strategy that readers use to recall prior knowledge and set a purpose for reading. It calls for readers to skim a text before reading, looking for various features and information that will help as they return to read it in detail later.

Why Use It

According to research, previewing a text can improve comprehension (Graves, Cooke, & LaBerge, 1983, cited in Paris et al., 1991).

Previewing a text helps readers prepare for what they are about to read and set a purpose for reading.

The genre determines the reader’s methods for previewing:

- Readers preview nonfiction to find out what they know about the subject and what they want to find out. It also helps them understand how an author has organized information.

- Readers preview biographies to determine something about the person in the biography, the time period, and some possible places and events in the life of the person.

- Readers preview fiction to determine characters, setting, and plot. They also preview to make predictions about story’s problems and solutions.

When To Use It

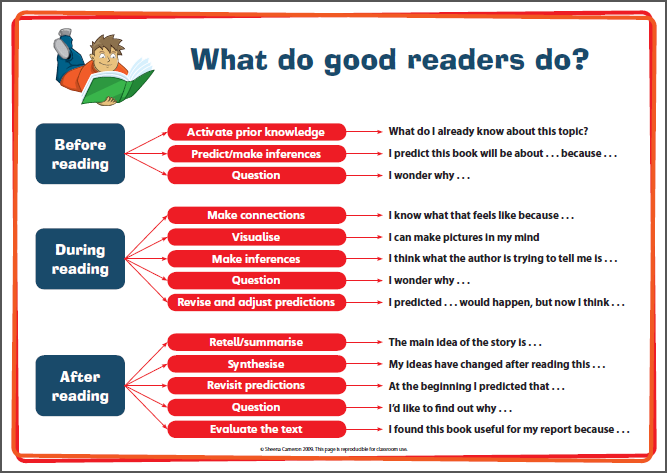

Previewing is a strategy readers use before and during reading.

How To Use It

When readers preview a text before they read, they first ask themselves whether the text is fiction or nonfiction.

- If the text is fiction or biography, readers look at the title, chapter headings, introductory notes, and illustrations for a better understanding of the content and possible settings or events.

- If the text is nonfiction, readers look at text features and illustrations (and their captions) to determine subject matter and to recall prior knowledge, to decide what they know about the subject. Previewing also helps readers figure out what they don’t know and what they want to find out.

How to Preview

Figure: CC BY-NCPreviewing a text is similar to watching a movie preview.

Think of previewing a text as similar to watching a movie trailer. A successful preview for either a movie or a reading experience will capture what the overall work is going to be about, generally what expectations the audience can have of the experience to come, how the piece is structured, and what kinds of patterns will emerge.

Previewing engages your prior experience and asks you to think about what you already know about this subject matter, or this author, or this publication. Then anticipate what new information might be ahead of you when you return to read this text more closely.

Specific Previewing Strategies

KWL+

KWL+ is a simple strategy that is both a reading-writing strategy, as well as an overall structure for research papers. K stands for "What I Know". W

stands for "What I Want to Know." L stands for "What I Learned. " + stands for "What I Still (+) Want to Know.

" + stands for "What I Still (+) Want to Know.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

After a brief review of the topic you will be reading about, on a piece of paper, create a table like the one below with the topic at the top of the page. Write down what you already know about the topic in the K column and what you want to learn in the W column. Use the "K" column as an "into the reading" activity and the "W" column as a guide for what you will look for as you read about the topic. After you have done your research or reading, write down what you learned in the "L" column. Then -- at the end of the research process or when you are done reading -- write down what you still want to know in the "+" column. This becomes a recursive process (routine) in which the "+" can then become the base for the next round of your inquiry.

Topic: _________________________________________________________________

| K (What I Know) | W (What I Want to Know) | L (What I Learned) | + (What I Still Want to Know) |

- Topic: _________________________________________________________________

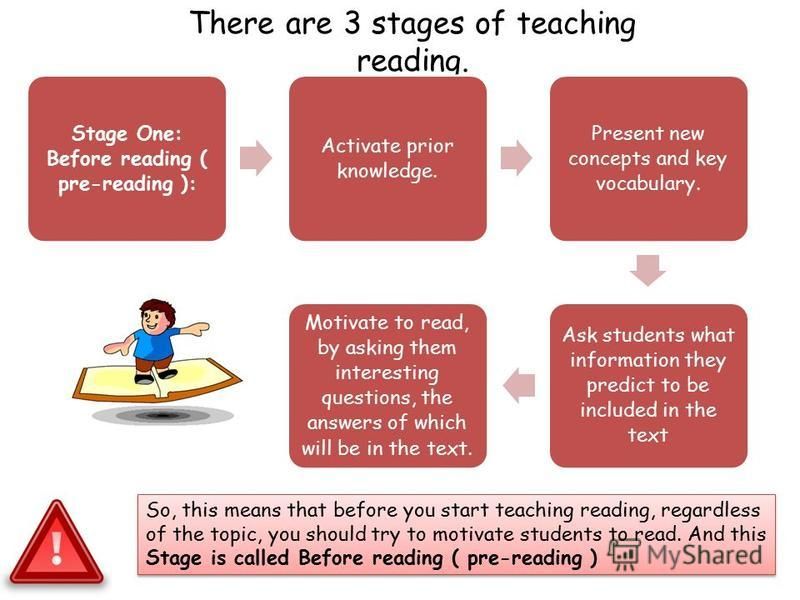

The 4 "P"s: Purpose, Preview, Prior Knowledge, Predict

1. Purpose: Determining your reading goals can help motivate you to read. It will also determine how carefully you need to read and what reading strategies you can use.

Purpose: Determining your reading goals can help motivate you to read. It will also determine how carefully you need to read and what reading strategies you can use.

- Are you looking for general main ideas or specific details, or both?

- Are you going to discuss what you read in class, take a test, use what you read in an essay? Or are you just reading for pleasure?

- How does this reading task tie into the unit or the whole course?

2. Preview: Spend a few minutes looking at visual clues to the author’s central idea, supporting points, and organization of ideas. Depending on the type of reading, look at some, or all, of the following elements:

- Title

- Introductory information about the author and/or selection

- First and last paragraphs

- First sentence of body paragraphs

- Headings and subheadings

- Italics, bold print, numbers, symbols

- Comprehension questions or, other after-reading assignment

3. Prior Knowledge: What do you already know about this topic? Using your own background knowledge and experiences can help stimulate your interest and increase your comprehension.

Prior Knowledge: What do you already know about this topic? Using your own background knowledge and experiences can help stimulate your interest and increase your comprehension.

4. Predict: After previewing a text, a reader can begin to make guesses about what the writer wants to say. These predictions are important in motivating you and keep you focused while reading.

Use the SQ3R Strategy

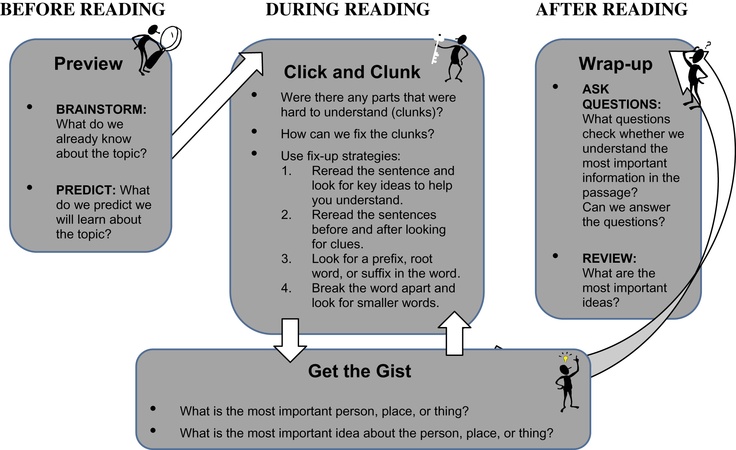

One strategy you can use to become a more active, engaged reader is the SQ3R strategy, a step-by-step process to follow before, during, and after reading. You may already be using some variation of it. In essence, the process works like this:

1. Survey the text in advance.

2. Form questions before you start reading.

3. Read the text.

4. Recite and/or record important points during and after reading.

5. Review and reflect on the text after you read.

Before reading, survey -- or preview -- the text. As noted earlier, reading introductory paragraphs and headings can help you figure out the text's main point and identify what important topics will be covered. However, surveying does not stop there. Look over sidebars, photographs, and any other text or graphic features that catch your eye. Skim a few paragraphs. Preview any boldfaced or italicized vocabulary terms. This will help you form a first impression of the material.

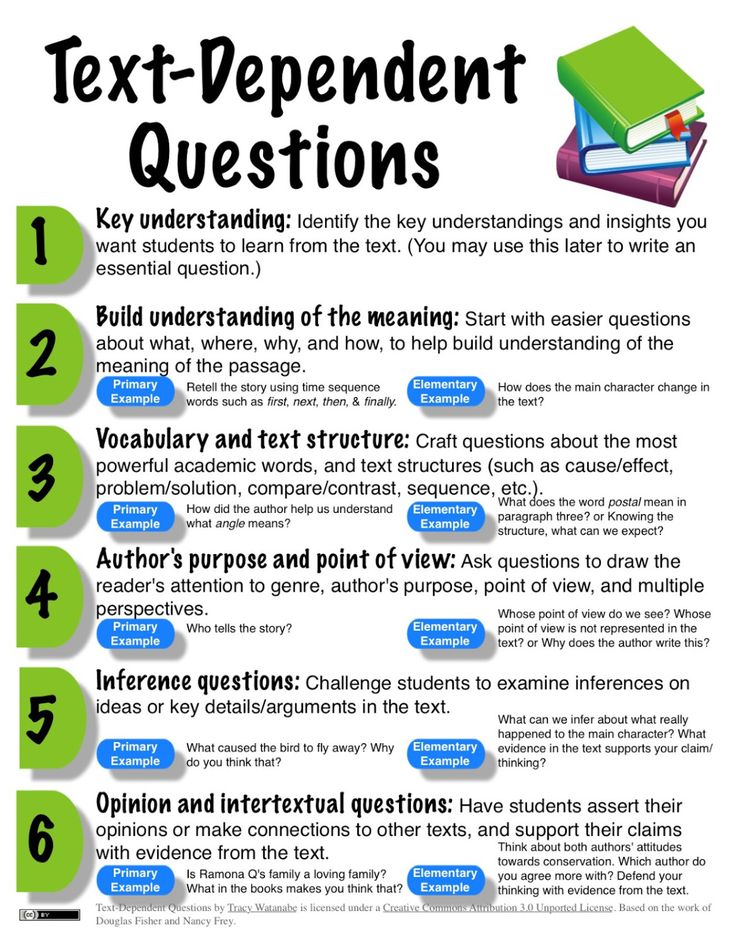

Next, start brainstorming questions about the text. What do you expect to learn from the reading? You may find that some questions come to mind immediately based on your initial survey or based on previous readings and class discussions. If not, try using headings and subheadings in the text to formulate questions. For instance, if one heading i your textbook reads "Medicare and Medicaid," you might ask yourself:

- When was Medicare and Medicaid legislation enacted? Why?

- What are the major differences between these two programs?

Although some of your questions may be simple factual questions, try to come up with a few that are ore open-ended. Asking in-depth questions will help you stay more engaged as you read.

Asking in-depth questions will help you stay more engaged as you read.

The next step is simple: read. As you read, notice whether your first impressions of the text were correct. Are the author's main points and overall approach about the same as what you predicted--or does the text contain a few surprises? Also, look for answers to your earlier questions and begin forming new questions. Continue to revise your impressions and questions as you read.

While you are reading, pause occasionally to record/recite important points. It is best to do this at the end of each section or where there is an obvious shift in the writer's train of thought. Put the book aside for a moment and recite aloud the main points of the section or any important answers you found there. You might also record ideas by jotting down a few brief notes in addition to, or instead of, reciting aloud. Either way, the physical act of articulating information makes you more likely to remember it.

After you have completed the reading, take some time to review the material more thoroughly. If the textbook includes review questions or your instructor has provided a study guide, use these tools to guide your review. You will want to record information in a more detailed format than you did during reading (which would be an outline or a list).

If the textbook includes review questions or your instructor has provided a study guide, use these tools to guide your review. You will want to record information in a more detailed format than you did during reading (which would be an outline or a list).

As you review the material, reflect on what you learned. Did anything surprise you, upset you, or make you think? Did you find yourself strongly agree or disagreeing with any points in the text? What topics would you like to explore further? Jot down your reflections in your notes. (Instructors sometimes require students to write brief response papers or maintain a reading journal. Use these assignments to help you reflect on what you read.)

The video below explains a little more about the SQ3R strategy.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\)Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Choose another text that you have been assigned to read for a class. Use the SQ3R process to complete the reading. (Keep in mind that you may need to spread the reading over more than one sesion, especially if the text is long.)

Use the SQ3R process to complete the reading. (Keep in mind that you may need to spread the reading over more than one sesion, especially if the text is long.)

Be sure to complete all the steps involved. Then, reflect o n how helpful you found this process. On a scale of one to ten, how useful did you find it? How does it compare with other study techniques you have used?

Use Other Active Reading Strategies

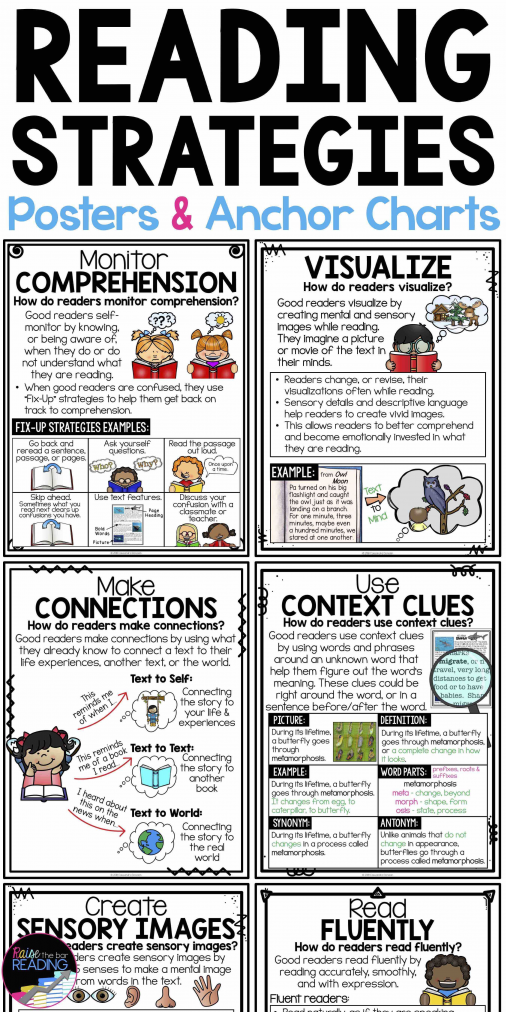

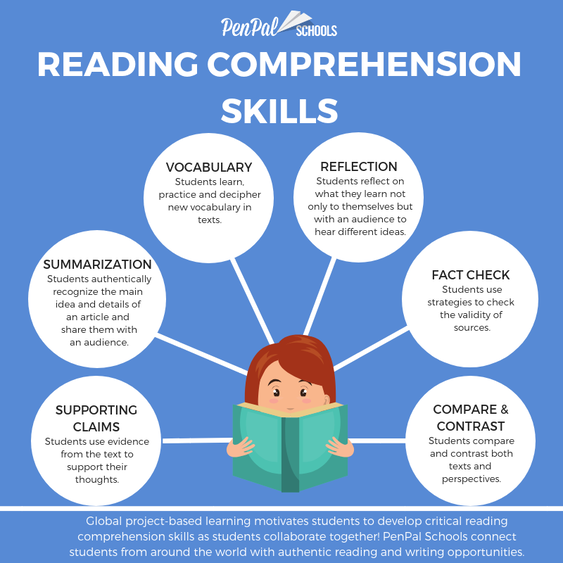

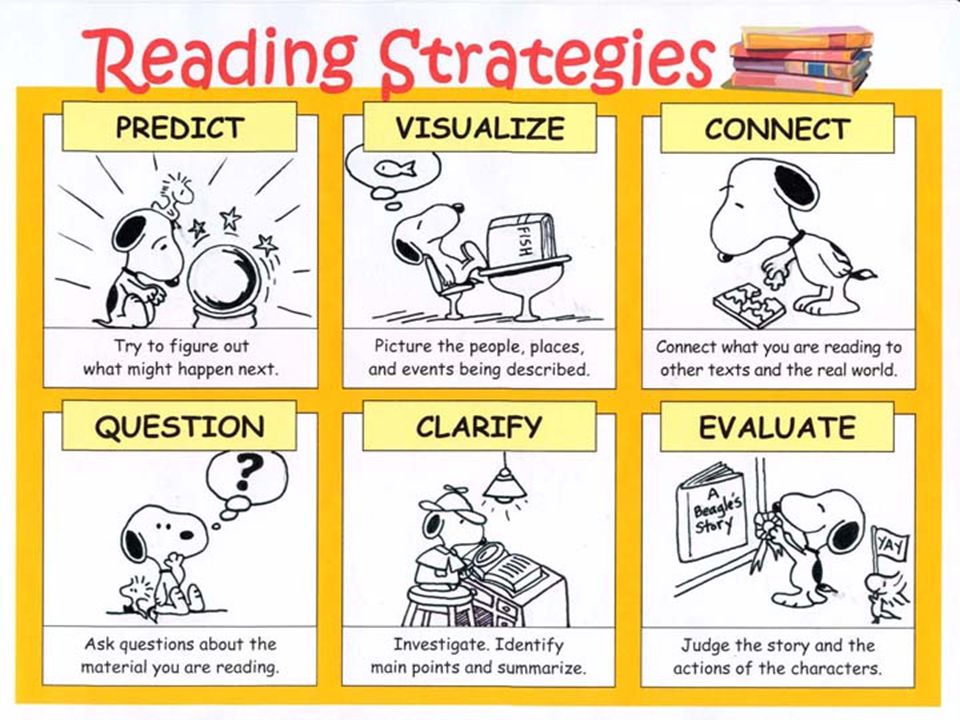

The SQ3R process encompasses a number of valuable active reading strategies: previewing a text, making predictions, asking and answering quesitons, and summarizing. You can use the following additional strategies to further deepen your understanding of what you read.

- Connect what you read to what you already know. Look for ways the reading supports, extends, or challenges concepts you have learned elsewhere.

- Relate the reading to your own life. What statements, people, or situations relate to your personal experiences?

- Visualize.

For both fiction and nonfiction texts, try to picture what is described. Visualizing is especially helpful when you are readinga narrative text, such as a novel or a historical account, or when you read expository texts that describes a process, such as how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

For both fiction and nonfiction texts, try to picture what is described. Visualizing is especially helpful when you are readinga narrative text, such as a novel or a historical account, or when you read expository texts that describes a process, such as how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). - Pay attention to graphics a well as text. Photographs, diagrams, flow charts, tables, and other graphics can help make abstract ideas more concrete and understandable.

- Understand the text in context. Understanding context means thinking about who wrote the text, when and where it was written, the author's purpose in writing it, and what assumptions or agendas influenced the author's ideas. For instance, two writers address the subject of health care reform, but if one article is an opinion piece and one is a news story, the rhetorical context is different.

- Plan to talk or write about what you read.

Jot down a few questions or comments in your notebook so you can bring them up in class. (This also gives you a source of topic ideas for papers and presentations later in the semester.) Discuss the reading on a class discussion board or blog about it.

Jot down a few questions or comments in your notebook so you can bring them up in class. (This also gives you a source of topic ideas for papers and presentations later in the semester.) Discuss the reading on a class discussion board or blog about it.

Additional Strategies

Following are some strategies you can use to enhance your reading even further:

- Pace yourself. Figure out how much time you have to complete the assignment. Divide the assignment into smaller blocks rather than trying to read the entire assignment in one sitting. If you have a week to do the assignment, for example, divide the work into five daily blocks, not seven; that way you won’t be behind if something comes up to prevent you from doing your work on a given day. If everything works out on schedule, you’ll end up with an extra day for review.

- Schedule your reading. Set aside blocks of time, preferably at the time of the day when you are most alert, to do your reading assignments.

Don’t just leave them for the end of the day after completing written and other assignments.

Don’t just leave them for the end of the day after completing written and other assignments. - Get yourself in the right space. Choose to read in a quiet, well-lit space. Your chair should be comfortable but provide good support. Libraries were designed for reading—they should be your first option! Don’t use your bed for reading textbooks; since the time you were read bedtime stories, you have probably associated reading in bed with preparation for sleeping. The combination of the cozy bed, comforting memories, and dry text is sure to invite some shut-eye!

- Avoid distractions. Active reading takes place in your short-term memory. Every time you move from task to task, you have to “reboot” your short-term memory and you lose the continuity of active reading. Multitasking—listening to music or texting on your cell phone while you read—will cause you to lose your place and force you to start over again. Every time you lose focus, you cut your effectiveness and increase the amount of time you need to complete the assignment.

- Avoid reading fatigue. Work for about fifty minutes, and then give yourself a break for five to ten minutes. Put down the book, walk around, get a snack, stretch, or do some deep knee bends. Short physical activity will do wonders to help you feel refreshed.

- Read your most difficult assignments early in your reading time, when you are freshest.

- Make your reading interesting. Try connecting the material you are reading with your class lectures or with other chapters. Ask yourself where you disagree with the author. Approach finding answers to your questions like an investigative reporter. Carry on a mental conversation with the author.

- Highlight your reading material. Most readers tend to highlight too much, hiding key ideas in a sea of yellow lines, making it difficult to pick out the main points when it is time to review. When it comes to highlighting, less is more. Think critically before you highlight.

Your choices will have a big impact on what you study and learn for the course. Make it your objective to highlight no more than 15-25% of what you read. Use highlighting after you have read a section to note the most important points, key terms, and concepts. You can’t know what the most important thing is unless you’ve read the whole section, so don’t highlight as you read.

Your choices will have a big impact on what you study and learn for the course. Make it your objective to highlight no more than 15-25% of what you read. Use highlighting after you have read a section to note the most important points, key terms, and concepts. You can’t know what the most important thing is unless you’ve read the whole section, so don’t highlight as you read. - Annotate your reading material. Marking up your book may go against what you were told in high school when the school owned the books and expected to use them year after year. In college, you bought the book. Make it truly yours. Although some students may tell you that you can get more cash by selling a used book that is not marked up, this should not be a concern at this time—that’s not nearly as important as understanding the reading and doing well in the class!

The purpose of marking your textbook is to make it your personal studying assistant with the key ideas called out in the text.

Use your pencil also to make annotations in the margin. Use a symbol like an exclamation mark (!) or an asterisk (*) to mark an idea that is particularly important. Use a question mark (?) to indicate something you don’t understand or are unclear about. Box new words, then write a short definition in the margin. Use “TQ” (for “test question”) or some other shorthand or symbol to signal key things that may appear in test or quiz questions. Write personal notes on items where you disagree with the author. Don’t feel you have to use the symbols listed here; create your own if you want, but be consistent. Your notes won’t help you if the first question you later have is “I wonder what I meant by that?”

Use your pencil also to make annotations in the margin. Use a symbol like an exclamation mark (!) or an asterisk (*) to mark an idea that is particularly important. Use a question mark (?) to indicate something you don’t understand or are unclear about. Box new words, then write a short definition in the margin. Use “TQ” (for “test question”) or some other shorthand or symbol to signal key things that may appear in test or quiz questions. Write personal notes on items where you disagree with the author. Don’t feel you have to use the symbols listed here; create your own if you want, but be consistent. Your notes won’t help you if the first question you later have is “I wonder what I meant by that?”Watch the following video on annotating texts:

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Video: Annotate It! Authored by: Janene Davison. All Rights Reserved. Standard YouTube license.

All Rights Reserved. Standard YouTube license.

- Get to Know the Conventions. Academic texts, like scientific studies and journal articles, may have sections that are new to you. If you’re not sure what an “abstract” is, research it online or ask your instructor. Understanding the meaning and purpose of such conventions is not only helpful for reading comprehension but for writing, too.

- Look up and Keep Track of Unfamiliar Terms and Phrases. Have a good college dictionary such as Merriam-Webster handy (or find it online) when you read complex academic texts, so you can look up the meaning of unfamiliar words and terms. Many textbooks also contain glossaries or “key terms” sections at the ends of chapters or the end of the book. Many books available on an e-reader have definitions already embedded if you highlight the unknown word. If you can’t find the words you’re looking for in a standard dictionary, you may need one specially written for a particular discipline.

For example, a medical dictionary would be a good resource for a course in anatomy and physiology. If you circle or underline terms and phrases that appear repeatedly, you’ll have a visual reminder to review and learn them. Repetition helps to lock in these new words and to get their meaning into long-term memory, so the more you review them, the more you’ll understand and feel comfortable using them.

For example, a medical dictionary would be a good resource for a course in anatomy and physiology. If you circle or underline terms and phrases that appear repeatedly, you’ll have a visual reminder to review and learn them. Repetition helps to lock in these new words and to get their meaning into long-term memory, so the more you review them, the more you’ll understand and feel comfortable using them. - Make Flashcards. If you are studying certain words for a test, or you know that certain phrases will be used frequently in a course or field, try making flashcards for review. For each key term, write the word on one side of an index card and the definition on the other. Drill yourself, and then ask your friends to help quiz you. Developing a strong vocabulary is similar to most hobbies and activities. Even experts in a field continue to encounter and adopt new words.

Contributors

- Adapted from Previewing in College Composition. Provided by: Lumen Learning.

CC BY-SA

CC BY-SA - Adapted from Successful College Composition. Authored by: Kathryn Crowther, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, and Kirk Swenson. Provided by: Galileo, Georgia's Virtual Library. CC-NC-SA-4.0

- Adapted from EDUC 1300: Effective Learning Strategies. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Public Domain: No Known Copyright

This page most recently updated on June 6, 2020.

This page titled 3.3: Reading Strategies - Previewing is shared under a CC BY-SA license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto (ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative) .

- Back to top

- Was this article helpful?

-

- Article type

- Section or Page

- Author

- Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto

- License

- CC BY-SA

- OER program or Publisher

- ASCCC OERI Program

- Show TOC

- yes

- Tags

-

- #4Ps

- #annotation

- #KWL+

- #predict

- #preview

- #previewing

- #prior knowledge

- #purpose

- #reading

- #reading strategies

Reading strategies | UNSW Current Students

Search

- Sign in

- Search

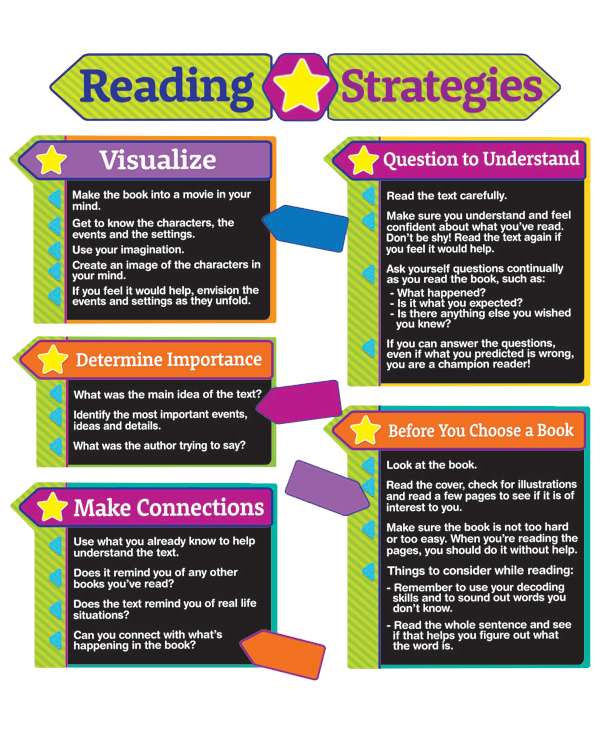

Active readers use reading strategies to help save time and cover a lot of ground. Your purpose for reading should determine which strategy or strategies to use.

Your purpose for reading should determine which strategy or strategies to use.

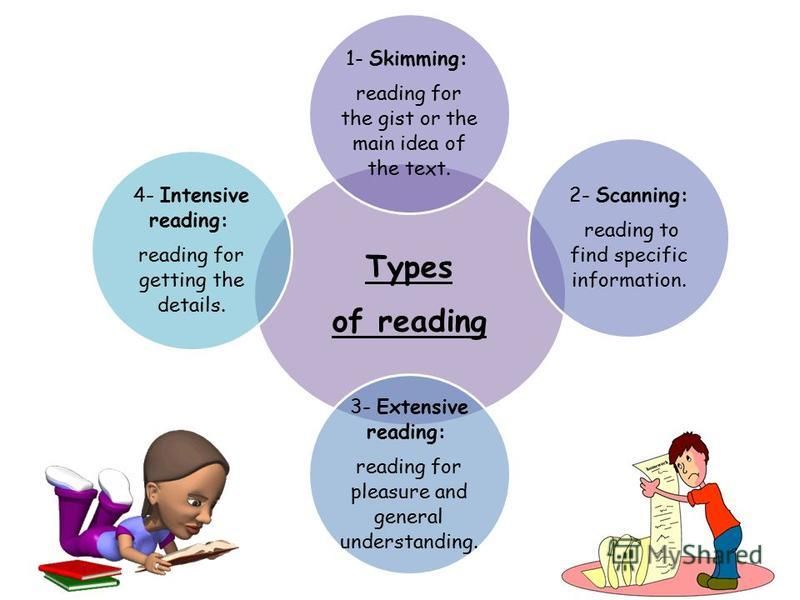

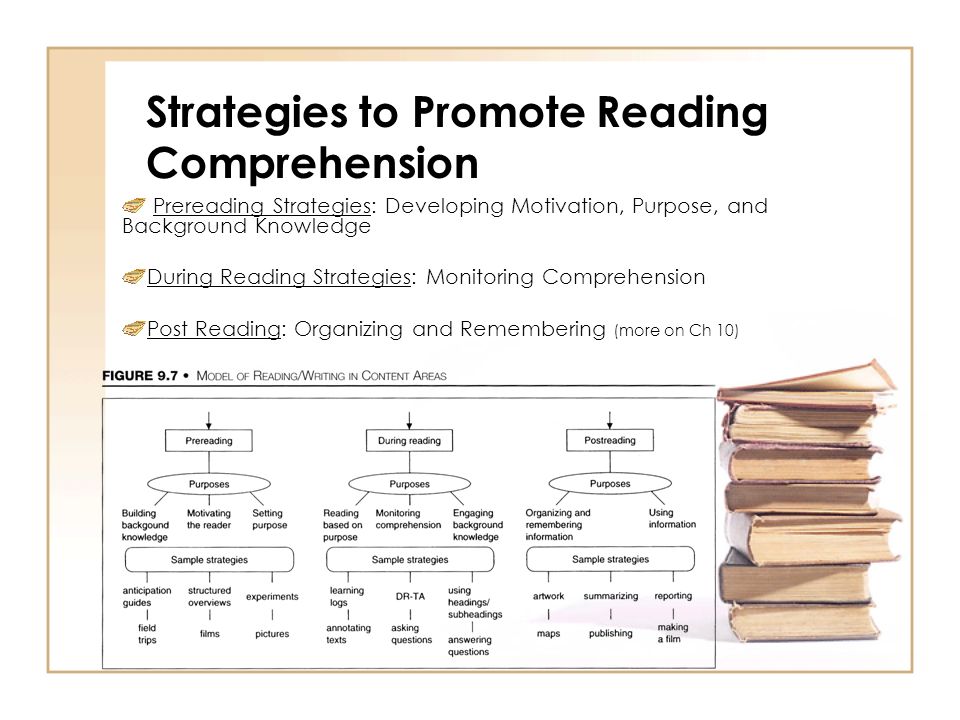

1. Previewing the text to get an overview

What is it? Previewing a text means that you get an idea of what it is about without reading the main body of the text.

When to use it: to help you decide whether a book or journal is useful for your purpose; to get a general sense of the article structure, to help you locate relevant information; to help you to identify the sections of the text you may need to read and the sections you can omit.

To preview, start by reading:

- the title and author details

- the abstract (if there is one)

- then read only the parts that ‘jump out’; that is: main headings and subheadings, chapter summaries, any highlighted text etc.

- examine any illustrations, graphs, tables or diagrams and their captions, as these usually summarise the content of large slabs of text

- the first sentence in each paragraph

2.

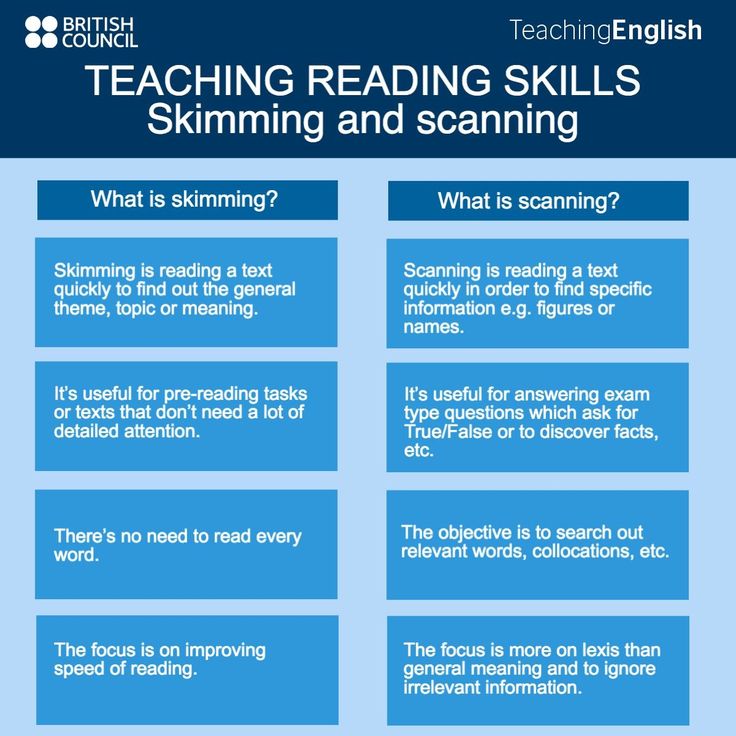

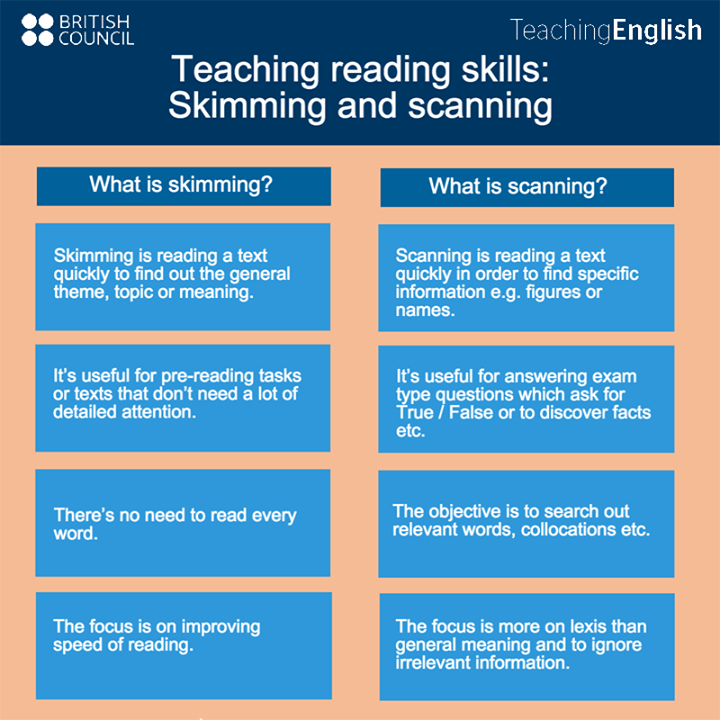

Skimming

Skimming What is it? Skimming involves running your eye very quickly over large chunks of text. It is different from previewing because skimming involves the paragraph text. Skimming allows you to pick up some of the main ideas without paying attention to detail. It is a fast process. A single chapter should take only a few minutes.

When to use it: to quickly locate relevant sections from a large quantity of written material. Especially useful when there are few headings or graphic elements to gain an overview of a text. Skimming adds further information to an overview.

How to skim:

- note any bold print and graphics.

- start at the beginning of the reading and glide your eyes over the text very quickly.

- do not actually read the text in total. You may read a few words of every paragraph, perhaps the first and last sentences.

- always familiarise yourself with the reading material by gaining an overview and/or skimming before reading in detail.

3. Scanning

What is it? Scanning is sweeping your eyes (like radar) over part of a text to find specific pieces of information.

When to use it: to quickly locate specific information from a large quantity of written material.

To scan text:

- after gaining an overview and skimming, identify the section(s) of the text that you probably need to read.

- start scanning the text by allowing your eyes (or finger) to move quickly over a page.

- as soon as your eye catches an important word or phrase, stop reading.

- when you locate information requiring attention, you then slow down to read the relevant section more thoroughly.

- scanning and skimming are no substitutes for thorough reading and should only be used to locate material quickly.

4. Intensive reading

What is it? Intensive reading is detailed, focused, ‘study’ reading of those important parts, pages or chapters.

When to use it: When you have previewed an article and used the techniques of skimming and scanning to find what you need to concentrate on, then you can slow down and do some intensive reading.

How to read intensively:

- start at the beginning. Underline any unfamiliar words or phrases, but do not stop the flow of your reading.

- if the text is relatively easy, underline, highlight or make brief notes (see ‘the section on making notes from readings).

- if the text is difficult, read it through at least once (depending on the level of difficulty) before making notes.

- be alert to the main ideas. Each paragraph should have a main idea, often contained in the topic sentence (usually the first sentence) or the last sentence.

- when you have finished go back to the unfamiliar vocabulary. Look it up in an ordinary or subject-specific dictionary. If the meaning of a word or passage still evades you, leave it and read on. Perhaps after more reading you will find it more accessible and the meaning will become clear.

Speak to your tutor if your difficulty continues.

Speak to your tutor if your difficulty continues. - write down the bibliographic information and be sure to record page numbers (more about this in the section on making notes from readings).

Remember, when approaching reading at university you need to make intelligent decisions about what you choose to read, be flexible in the way you read, and think about what you are trying to achieve in undertaking each reading task.

See next: More reading strategies

Back to top

UNSW Sydney NSW 2052 Australia | Authorised by Deputy Vice-Chancellor Academic

UNSW CRICOS Provider Code: 00098G | TEQSA Provider ID: PRV12055 | ABN: 57 195 873 179

Page last updated: Friday 25 March 2022

Back to top4 methods of quick reading of educational and scientific literature

People have been reading for hundreds of centuries, but only in our time the question of increasing the speed of reading has become so acute. The main reason is the increase in the volume of information as a result of the development of science, its integrativity and the need to significantly accelerate the development of information. Organize daily workouts for your brain and the result will not be long in coming.

The main reason is the increase in the volume of information as a result of the development of science, its integrativity and the need to significantly accelerate the development of information. Organize daily workouts for your brain and the result will not be long in coming.

In Russian, reading is interpreted in several meanings:

1. reading as a process of perception of texts arranged in various ways:

2. reading as pronunciation, recitation of texts, including for educational purposes;

3. reading as an oral presentation to an audience of educational (lecture) or scientific material (report).

4. reading as a process of perception, processing, recoding, understanding and memorization of various symbols and texts with the help of a visual analyzer.

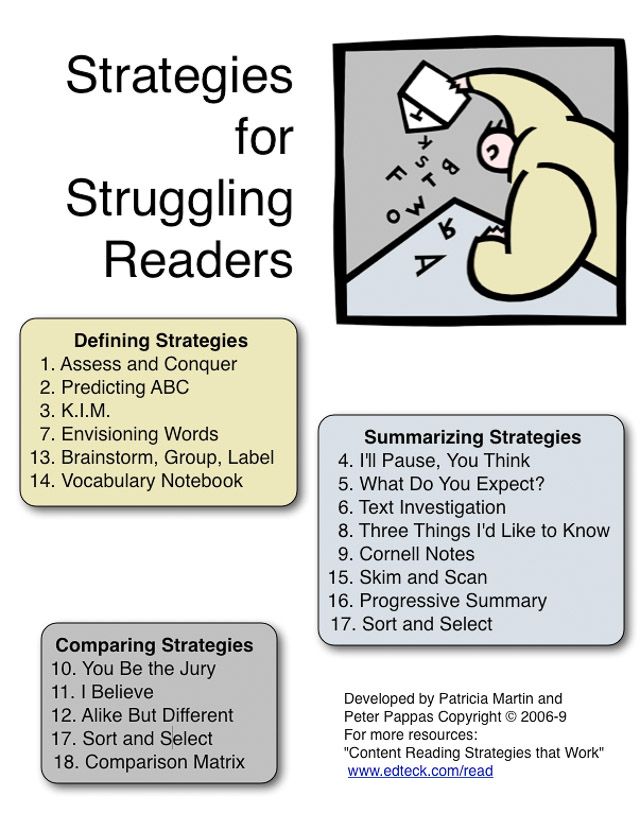

Figure 1. Text processing model In-depth is a way of reading in which the reader pays attention to details, analyzes and evaluates them. It is also called analytical or critical.

For example, this way of reading is best used when studying academic disciplines.

Quick reading - continuous reading of the text, in which the process of analyzing facts and synthesizing individual concepts quickly proceeds.

For example, this way of reading is suitable for reading scientific, technical, economic, etc. literature. nine0003

Selective reading is a reading method in which individual sections of the text are read selectively.

For example, this method is used for secondary reading of an information source after its preview.

Reading-browsing is a way of reading in which there is a preliminary acquaintance with the source of information.

For example, we pick up a book, skim through the preface, look for the author’s most important provisions by the table of contents, according to which we can presumably judge the main content of the source, look through the conclusion and draw a conclusion about the usefulness and value of the text.

nine0003

Reading-scanning is a method of reading a source in which it searches for exclusively factual information (numbers, words, surnames, etc.).

For example, to prove his point of view, the reader looks for this or that statistical information in books.

Thus, the considered methods of reading show the need not only to master them, but also the opportunity to choose the appropriate method each time, depending on the nature of the text and the time budget. nine0003

Regression - involuntary, mechanical, repeated eye fixations of the same section of the text (phrases, words, sentences). With such reading, the eyes move back, but not to the starting point of reading, but limiting themselves to the near zone.

Speaking is the movement of the lips, tongue and other organs of speech when reading to oneself. When reading slowly, internal speaking occurs, proceeding at the same speed with which we read the text aloud.

Small field of vision — coverage of the text by the eye during one fixation of the gaze. A person perceives letters, words, at best a few words, therefore, the eyes make several fixations, which is called splitting the gaze.

Absence of a reading strategy - absence of a goal, task and topic that moves the reader.

Lack of attention - switching thoughts to extraneous sounds, thoughts, objects reduces interest in reading and slows down the perception of the text. nine0003

Reading methods differ in the speed of their implementation, which is defined as the number of characters read per unit of time. Important is not only the speed of reading the text, but also the coefficient of understanding, the productivity of reading.

In different countries and languages, both the names and meanings of reading standards differ (see table).

Reading speed standards in different countries Our country also has reading speed standards for adults (see table).

Of course, each person's reading speed is individual and depends on many factors: the activity of neuropsychic processes, features of thinking, attention, genetic predisposition. But each person, training daily, can change his own indicators.

Reception 1. Disable regression.

It is necessary to force yourself not to return to the previously read text. To do this, you can wear headphones while reading or use a special reading algorithm. This algorithm assumes sequential extraction of information on key issues. nine0003

Special reading algorithm

TITLE (books, articles) - AUTHOR (authors) - SOURCES AND ITS DATA - TOPIC (what the book, article is about) - FACTUAL INFORMATION - DISPUTE ISSUES - NOVELTY OF THE MATERIAL AND THE POSSIBILITY OF ITS USE.

Reception 2. Disable internal articulation (pronunciation).

Since our speech is a rhythmic pattern, to increase the speed of reading it is necessary to use the technique of arrhythmic tapping. nine0003

Arrhythmic tapping reception

While reading to himself, a person taps out a rhythm with his hand that does not correspond to the rhythm of Russian speech. For example: one-two-three-four-six-seven-eight. This rhythm breaks the usual mechanism of speech movements when reading a Russian text, that is, it interferes with internal pronunciation.

Reception 3. Expanding the field of view.

The untrained eye is forced to make 12-16 stops while reading, which takes time and tires the eye muscles. nine0003

Vertical Reading ChartVertical reading technique

The table contains numbers from 1 to 25. Look at the center of the table from a distance of 30-40 cm, trying to see the entire table. You must find all the numbers in ascending order from 1 to 25 in 25 seconds.

If you have lost any purely, then look for it by moving the eye only vertically. Using the same pattern, you can make tables for yourself with a large number of numbers. Exercise 3-5 minutes daily.

Reception 3. Improving attention.

In psychology, it is customary to distinguish the following qualities of attention: concentration, volume, switching, distribution, and stability. Fluent reading skills require the development of all qualities.

To improve all qualities, a series of exercises must be performed daily.

Exercise example.

You have two tasks. Each of which you must close with a piece of paper immediately after reading. Read assignments very quickly. Then you should answer the questions. nine0003

Task 1. The wife asked her husband to buy oil, soap, meat, and cabbage. Husband bought: cabbage, soap, oil, lard.

What did your husband forget to buy? What did he buy extra?

Task 2. In room 235, in the right drawer of the cabinet, which stands next to the desk, there is a book of Wormsbereh and the Cabin “One Hundred Pages an Hour”. Bring her. Where exactly is the book? Were you asked to enter room 325, 235, 435? Where is the closet? Where is the book? Who are the authors of the book?

The online Schulte table is one of the most effective simulators for developing attention, memory and speed reading skills. nine0003

Lumosity - online version has more than 40 games for training attention, multitasking, short-term and long-term memory, focus (concentration), stress management, etc.

PEAK - contains 25 puzzles divided into several categories. Focus - a series of exercises on interacting with shapes: sorting, matching and isolating them. Agility - puzzles that require quick decision making and cause some brain confusion. nine0005 Problem Solving - a series of puzzles in which special emphasis was placed on working with numbers and geometric shapes. Memory - 7 exercises to train memory and work with cards. Language - provides for the development of skills for quick selection of words, pairing, searching for words among the letter grid (support for English only).

nine0005 Problem Solving - a series of puzzles in which special emphasis was placed on working with numbers and geometric shapes. Memory - 7 exercises to train memory and work with cards. Language - provides for the development of skills for quick selection of words, pairing, searching for words among the letter grid (support for English only).

"B-trainika" — daily selects 5 exercises for you, focused on the comprehensive improvement of the basic cognitive functions of the brain. The total class time is 15-20 minutes per day. All simulators are made in the form of games, so classes on them are exciting and interesting. nine0003

Thus, with proper determination, diligence and desire, success is guaranteed to you.

Read-only mode in ArcGIS Enterprise—Portal for ArcGIS

In ArcGIS Enterprise deployments, resources can be quickly created, modified, and accessed. However, sometimes you may want to prevent new resources from being added to your deployment, or to prevent changes to existing resources and settings.

Read-only mode, introduced in version 10.8, allows administrators to freeze an ArcGIS Enterprise deployment at a specific point in time, restricting operations that change site data or configurations. nine0003

When a deployment becomes read-only, it manages the portal, ArcGIS Server federated sites, and ArcGIS Data Store.

If your organization has one or more standalone ArcGIS Server sites, you can use the ArcGIS Server read-only mode setting.

Read-only mode does not prevent access to existing resources and allows some operations. Your users can still view and interact with resources. When you take a deployment out of read-only mode, all operations can continue as before. nine0003

By setting your ArcGIS Enterprise deployment to read-only, you can reduce the chance of data loss when changes or updates are made to the system.

Used for read-only mode

Read-only mode can be useful when upgrading your ArcGIS Enterprise deployment to later versions.

For organizations with system uptime policies or service level agreements, placing a deployment in read-only mode reduces upgrade complexity. These organizations often need to maintain availability for most or all of the update installation period. They can achieve this by setting up a duplicate deployment and replicating resources to it before upgrading the main deployment. nine0003

For example, they can set up their production environment as read-only, replicate resources to the fallback environment, and update the fallback environment to check for updates. After checking for updates, they can redirect traffic to a fallback deployment. During this process, the original production environment is available and resources can be used but not modified. This eliminates the risk of data loss during the update.

Read-only mode can also help if you are updating your computers. You can make your deployment read-only and create a backup before making major changes to the deployment's hardware or configuration. This avoids losing any new or changed resource if you need to rollback to a backup. nine0003

This avoids losing any new or changed resource if you need to rollback to a backup. nine0003

Functional limitations in read-only mode

When ArcGIS Enterprise is in read-only mode, many tasks and workflows are not available. No requests to change or modify data or configurations will be honored.

The following operations are not allowed in read-only mode:

- Creating or loading features

- Running analysis tools in Map Viewer Classic

- Publishing hosted feature layers or any other type of service

- Editing any feature services, including hosted services

- Opening new ArcGIS Notebooks or saving existing notebooks

- Closing ArcGIS Notebook Server containers

- Creating or editing groups

- Creating or editing users

- Making any changes to the configuration of your ArcGIS Enterprise components

- Importing ArcGIS Enterprise backups using the webgisdr utility

- Importing ArcGIS Server or portal 9 backups0223

The following operations are allowed in read-only mode:

- View content in Map Viewer or Map Viewer Classic

- Manage log settings

- Create backups

- Preview ArcGIS Notebooks

- Restore ArcGIS Notebooks using the Datastore Storedata utility

- Portal re-indexing

If your 11. 0 portal has 10.7.1 or earlier federated servers, editing feature services on those servers is not blocked when ArcGIS Enterprise is in read-only mode. You must disable editing on these services individually. nine0003

0 portal has 10.7.1 or earlier federated servers, editing feature services on those servers is not blocked when ArcGIS Enterprise is in read-only mode. You must disable editing on these services individually. nine0003

These lists are not exhaustive. You may find that other operations, such as running analysis tools on ArcGIS Notebooks, are blocked. You may also find that other operations not listed are allowed. In general, don't expect to be able to modify resources while ArcGIS Enterprise is in read-only mode, but you should be able to view an existing resource and settings.

Set ArcGIS Enterprise to read-only mode

Complete the following steps to make ArcGIS Enterprise read-only.

- Sign in to the ArcGIS Portal Directory as a member with the default administrator role of your portal. URL in the format https://webadaptorhost.domain.com/webadaptorname/portaladmin.

- Click Mode > Refresh.

Learn more