Reading comprehension is

Comprehension | Reading Rockets

Comprehension is the understanding and interpretation of what is read. To be able to accurately understand written material, children need to be able to (1) decode what they read; (2) make connections between what they read and what they already know; and (3) think deeply about what they have read.

One big part of comprehension is having a sufficient vocabulary, or knowing the meanings of enough words. Readers who have strong comprehension are able to draw conclusions about what they read – what is important, what is a fact, what caused an event to happen, which characters are funny. Thus comprehension involves combining reading with thinking and reasoning.

Target the Problem: Comprehension

What the problem looks like

A kid's perspective: What this feels like to me

Children will usually express their frustration and difficulties in a general way, with statements like "I hate reading!" or "This is stupid!". But if they could, this is how kids might describe how comprehension difficulties in particular affect their reading:

- It takes me so long to read something. It's hard to follow along with everything going on.

- I didn't really get what that book was about.

- Why did that character do that? I just don't get it!

- I'm not sure what the most important parts of the book were.

- I couldn't really create an image in my head of what was going on.

A parent's perspective: What I see at home

Here are some clues for parents that a child may have problems with comprehension:

- She's not able to summarize a passage or a book.

- He might be able to tell you what happened in a story, but can't explain why events went the way they did.

- She can't explain what a character's thoughts or feelings might have been.

- He doesn't link events in a book to similar events from another book or from real life.

A teacher's perspective: What I see in the classroom

Here are some clues for teachers that a student may have problems with comprehension:

- He seems to focus on the "wrong" aspect of a passage; for example, he concentrates so much on the details that the main idea is lost.

- She can tell the outcome of a story, but cannot explain why things turned out that way.

- He does not go behind what is presented in a book to think about what might happen next or why characters took the action they did.

- She brings up irrelevant information when trying to relate a passage to something in her own life.

- He seems to have a weak vocabulary.

- She cannot tell the clear, logical sequence of events in a story.

- He does not pick out the key facts from informational text.

- He cannot give you a "picture" of what's going on in a written passage; for example, what the characters look like or details of where the story takes place.

How to help

With the help of parents and teachers, kids can learn strategies to cope with comprehension problems that affect his or her reading. Below are some tips and specific things to do.

What kids can do to help themselves

- Use outlines, maps, and notes when you read.

- Make flash cards of key terms you might want to remember.

- Read stories or passages in short sections and make sure you know what happened before you continue reading.

- Ask yourself, "Does this make sense?" If it doesn't, reread the part that didn't make sense.

- Read with a buddy. Stop every page or so and take turns summarizing what you've read.

- Ask a parent or teacher to preview a book with you before you read it on your own.

- As you read, try to form mental pictures or images that match the story.

What parents can do to help at home

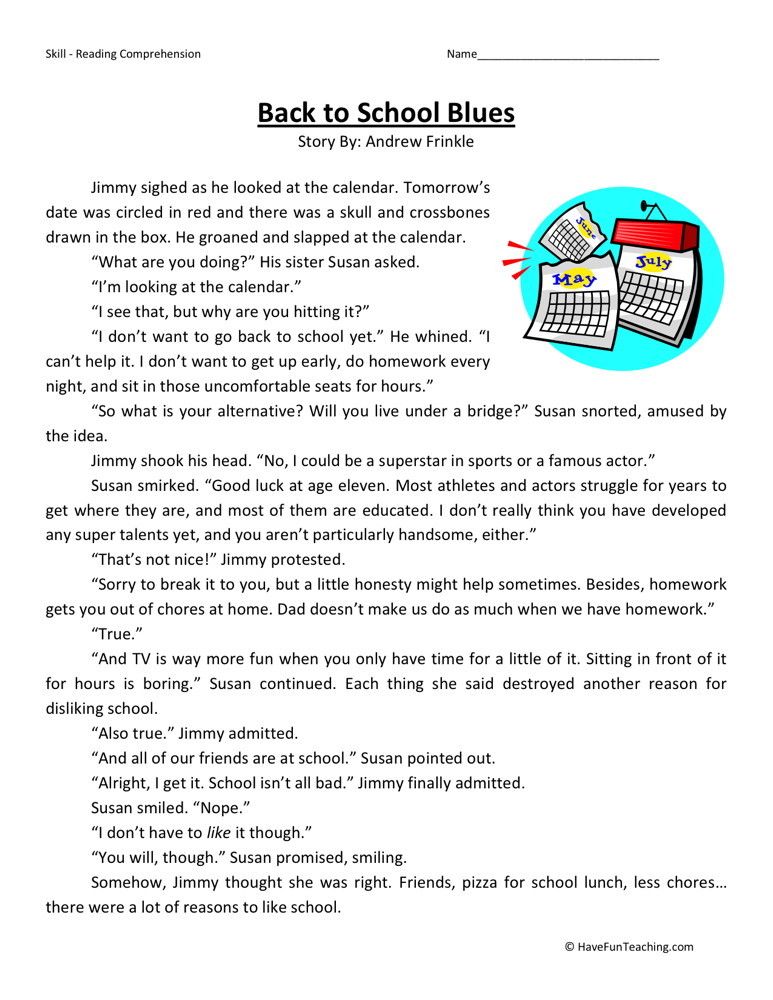

- Hold a conversation and discuss what your child has read. Ask your child probing questions about the book and connect the events to his or her own life. For example, say "I wonder why that girl did that?" or "How do you think he felt? Why?" and "So, what lesson can we learn here?".

- Help your child make connections between what he or she reads and similar experiences he has felt, saw in a movie, or read in another book.

- Help your child monitor his or her understanding. Teach her to continually ask herself whether she understands what she's reading.

- Help your child go back to the text to support his or her answers.

- Discuss the meanings of unknown words, both those he reads and those he hears.

- Read material in short sections, making sure your child understands each step of the way.

- Discuss what your child has learned from reading informational text such as a science or social studies book.

What teachers can do to help at school

- As students read, ask them open-ended questions such as "Why did things happen that way?" or "What is the author trying to do here?" and "Why is this somewhat confusing?".

- Teach students the structure of different types of reading material. For instance, narrative texts usually have a problem, a highpoint of action, and a resolution to the problem. Informational texts may describe, compare and contrast, or present a sequence of events.

- Discuss the meaning of words as you go through the text. Target a few words for deeper teaching, really probing what those words mean and how they can be used.

- Teach note-taking skills and summarizing strategies.

- Use graphic organizers that help students break information down and keep tack of what they read.

- Encourage students to use and revisit targeted vocabulary words.

- Teach students to monitor their own understanding. Show them how, for example, to ask themselves "What's unclear here?" or "What information am I missing?" and "What else should the author be telling me?".

- Teach children how to make predictions and how to summarize.

More information

Find out more about comprehension issues with these resources from Reading Rockets, The Access Center, and LD OnLine:

Other recommended links:

< previous | next >

The Importance of Reading Comprehension

Many children in the United States haven’t fully developed their reading skills. Between 2017 and 2019, the number of children in grades 4 through 8 reading at or above their grade level decreased. In other words, the number of children who lack the necessary reading skills increased.

Between 2017 and 2019, the number of children in grades 4 through 8 reading at or above their grade level decreased. In other words, the number of children who lack the necessary reading skills increased.

The National Reading Panel Report identified five components vital to developing reading skills: phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Although each component is important in developing a child’s reading ability, the following information focuses on four comprehension strategies that are used to help increase the reading comprehension of young children and older children who are struggling with reading.

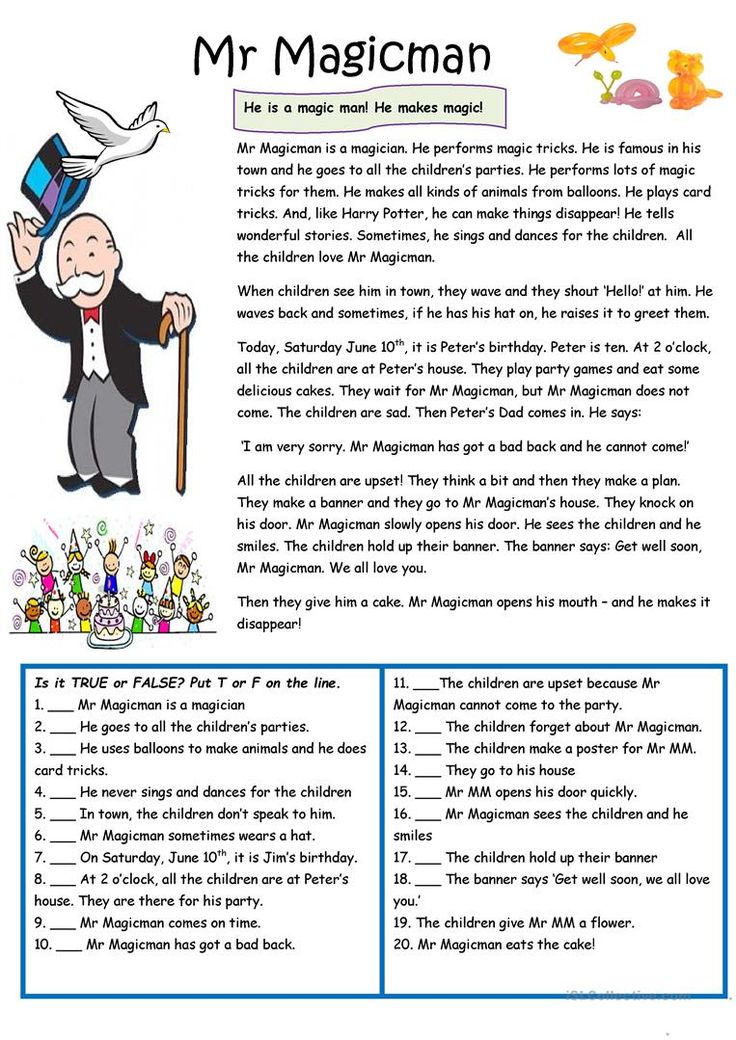

Comprehension refers to the ability to understand written words. It is different from the ability to recognize words. Recognizing words on a page but not knowing what they mean does not fulfill the purpose or goal of reading, which is comprehension. Imagine, for example, that a teacher gives a child a passage to read. The child can read the entire passage, but he or she knows nothing when asked to explain what was read. Comprehension adds meaning to what is read. Reading comprehension occurs when words on a page are not just mere words but thoughts and ideas. Comprehension makes reading enjoyable, fun, and informative. It is needed to succeed in school, work, and life in general.

Comprehension adds meaning to what is read. Reading comprehension occurs when words on a page are not just mere words but thoughts and ideas. Comprehension makes reading enjoyable, fun, and informative. It is needed to succeed in school, work, and life in general.

There are different strategies to use to enhance comprehension. It takes patience and continuous guidance when using these strategies. When working with children, remember to model the strategy as well as provide guided practice. As their skills increase, slowly decrease your guidance. The goal is to get children to use the strategies automatically. The following are strategies that can be used to help build reading comprehension in children:

Predicting

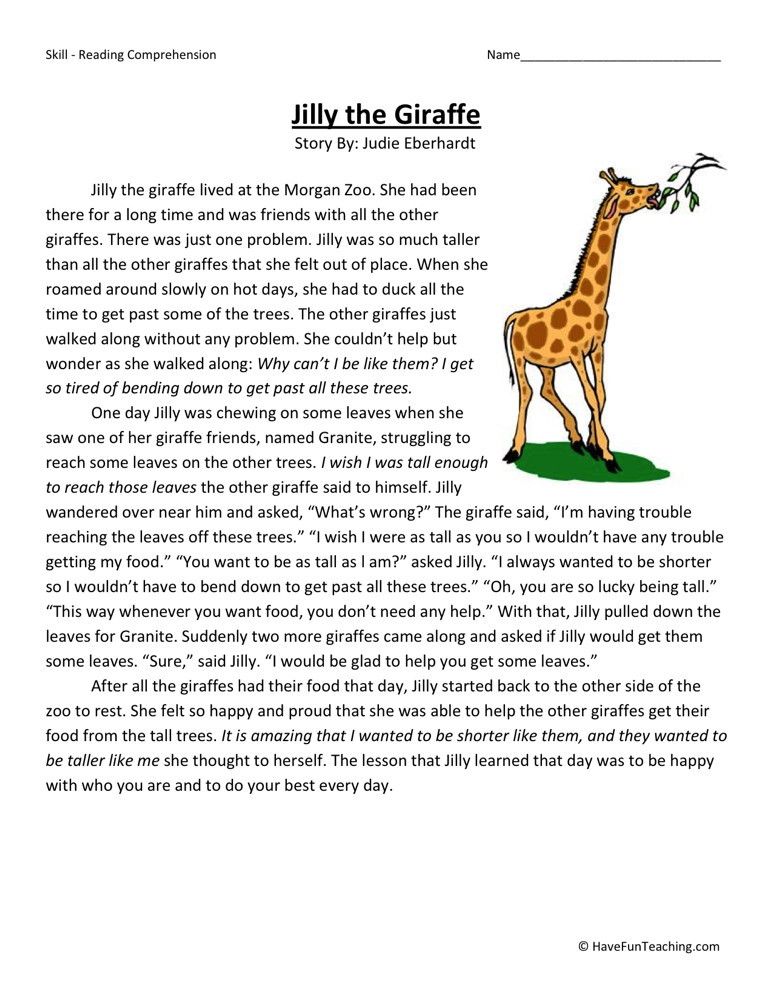

This strategy involves asking children to make informed predictions based on what they obtain from the story or text. Predictions require asking children to make guesses about what might happen. Predictions are made based on what they see, hear, or read relative to the book’s cover, title, pictures, drawing, table of content, and headings.

When asked a question, such as “What do you think this book will be about?” or “What do you think will happen to/if …?,” children make predictions or guesses when answering. Predicting builds interest and understanding of the text, and it establishes a purpose for reading. This strategy keeps children actively engaged by connecting, reflecting, and revising their predictions.

Making Connections to Prior Knowledge

Making connections to prior knowledge involves connecting a new idea to knowledge and experiences already known. It requires getting children to relate their own experiences to something in the story. The goal is to get children to use their prior knowledge to help make sense of the text they read. Prior knowledge can include their experiences or knowledge of words, places, animals, or events. For example, the children know the word “bones” because of a previous discussion on bones because of a classmate’s broken arm. When they read a new word, such as “skeleton”, their prior knowledge of bones will be used to help them understand the new term.

Children start by making connections between text and their personal experiences (text-to-self). As they grow older, connections are made between different books, texts, or ideas by identifying similarities. In other words, to increase comprehension, get children to make text-to-self, text-to-text, and text-to-world connections before, during, and after they read. For example, a discussion of the new or difficult vocabulary words before reading the text can help increase children’s comprehension. When reading, they can then activate their prior knowledge of the new terms.

Visualizing

Visualizing is also a strategy used to increase reading comprehension. It requires getting children to create in their minds a mental image of what they read from the text. Children can mentally envision what they are reading. The mental image helps children understand, recall details, remember, and draw conclusions from the things they encountered while reading. For example, ask children to make a drawing based on what they read. Also, while reading a passage to children, ask them to close their eyes and listen. Ask them to create a movie in their mind of what the words are describing.

Also, while reading a passage to children, ask them to close their eyes and listen. Ask them to create a movie in their mind of what the words are describing.

Summarizing

This strategy involves getting children, when reading, to identify the main idea in the text and putting the idea into their own words. Children must sort through the information to determine what information is important and what is unimportant. They take the most important information and put it in their own words and use as few words as possible to explain the text. This strategy is not to be applied only at the end of the story. Instead, children should be taught to summarize throughout the story.

Without comprehension, children gain no meaning from what they read. Comprehension strategies are used to increase children’s understanding of the text to help them become active readers by engaging with the text. Learn more about Alabama Extension’s Parent-Child Reading Enhancement Program to enhance a child’s reading ability.

6 Key Skills for Reading Comprehension

For some people, reading is like a walk in the park on a warm summer day, an enjoyable activity that is easy to master. In fact, reading is a complex process that involves many different skills. Together, these skills lead to the ultimate goal of learning to read: comprehensive reading comprehension.

Text comprehension can be difficult for children for many reasons, but regardless of them, knowing what underdeveloped skills this is due to, you will be able to provide your child with the best help.

Let's take a look at the six reading comprehension skills and how you can help your child develop them.

1. Decoding

Decoding is an extremely important step in the reading process. Children use this skill to sound out words they have heard before but not seen written. The ability to decode is the foundation of all other reading skills.

Decoding relies on one of the first language skills to develop, phonemic comprehension (this skill is part of a broader set of skills called phonological comprehension). Phonemic awareness allows children to hear and distinguish individual sounds in words (also known as phonemes). It also allows them to "play" with sounds in syllables and words.

Phonemic awareness allows children to hear and distinguish individual sounds in words (also known as phonemes). It also allows them to "play" with sounds in syllables and words.

Decoding also relies on the ability to match individual sounds and letters. For example, to read the word "sun", the child must know that the letter "s" sounds like "s". Understanding the relationship between letters and sounds is an important step towards "voicing" words.

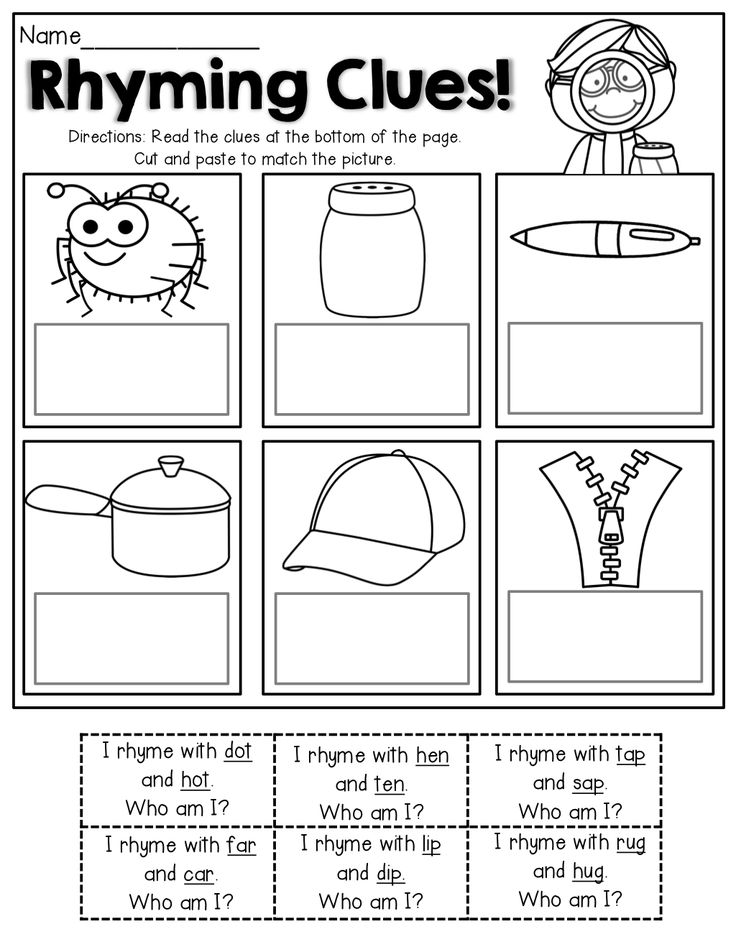

How to help: Many children learn phonological awareness naturally by reading books, listening to songs and poems. But for some children it is not so easy. In fact, one of the earliest signs of reading difficulty is trouble with rhyming, counting syllables, or identifying the first sound in a word.

The best way to help your child improve these skills is to guide them with precise instructions and lots of practice. Children need to be taught how to correctly identify sounds and work with them. You can also develop phonological perception by playing with words, reading poems aloud to your child, or using special computer techniques aimed at developing phonemic perception and decoding.

You can also develop phonological perception by playing with words, reading poems aloud to your child, or using special computer techniques aimed at developing phonemic perception and decoding.

2. Reading fluently

To read fluently, children must recognize words immediately, including words that do not read as they are written. By developing reading fluency, the child increases not only reading speed, but also reading comprehension.

Decoding and reading each word can be a lot of work. Word recognition is the ability to recognize a word instantly just by looking at it, without having to read it out loud. When children can read quickly and with almost no errors, they are said to be able to read "fluently".

People who can read fluently read fluently and rhythmically. They use the context to understand the meaning and change the intonation in their voice depending on what they are reading about. The ability to read fluently is critical to a good understanding of the text.

How to help: Word recognition can be a big hurdle for beginning readers. Usually a person needs to see a word from 4 to 14 times in order to learn to automatically recognize it. But, for example, children diagnosed with dyslexia may need to see the word up to 40 times.

Many children have difficulty reading fluently. To improve word recognition and other reading skills, children need help and a lot of practice. The best way to strengthen these skills is to practice reading books. It is important to choose books that are appropriate for the child's reading level.

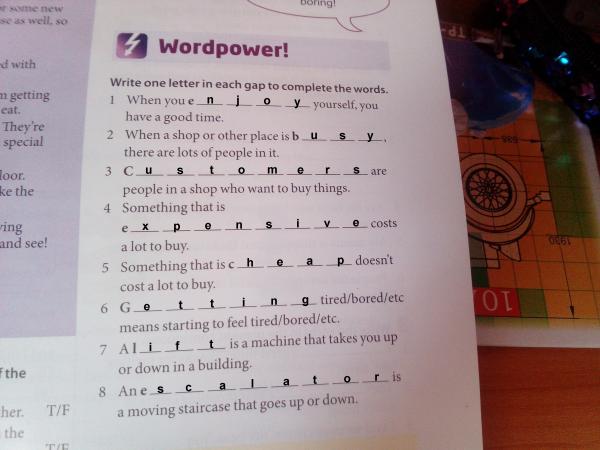

3. Vocabulary

To understand what you read, you need to understand at least most of the words in the text. A rich vocabulary is a key component of text comprehension. Students can learn new words during class, but they usually learn the meaning of words through everyday situations and while reading.

How to help: The more new words children learn, the more their vocabulary grows. You can help your child develop vocabulary by talking to him often about different topics, introducing him to new words and concepts. Word games and funny jokes are also fun ways for children to reinforce these skills.

You can help your child develop vocabulary by talking to him often about different topics, introducing him to new words and concepts. Word games and funny jokes are also fun ways for children to reinforce these skills.

Daily reading together also helps to build vocabulary. When reading aloud to your child, stop when you encounter new words and explain their meaning. But it is also important that the child reads independently. Even if there is no one to explain the meaning of a new word, the child can guess its meaning from the context, and also learn with the help of a dictionary.

Teachers can also help by choosing interesting words to study and learning them all together in class. To practice vocabulary, the teacher can engage students in dialogue during the lesson, or play word games to make learning new words fun.

4. Sentence construction and cohesion

Understanding how sentences are built can seem like a skill necessary for writing. The same can be said about the connection of ideas within and between sentences, which is called cohesion. But these skills are also important for reading comprehension.

The same can be said about the connection of ideas within and between sentences, which is called cohesion. But these skills are also important for reading comprehension.

Knowing how ideas connect at the sentence level helps children make sense of passages and entire texts. This also leads to what is called coherence, or the ability to relate ideas to other ideas in a common work.

How to help: Explain the basics of sentence construction to your child. Work with him to connect two or more thoughts, both in writing and orally.

5. Expanding horizons and reasoning

read. It is also important to teach the child to “read between the lines” and find meaning where it is not literally written.

How to help: Your child can broaden their horizons through reading, socializing, watching movies and TV shows, and exploring art. Also many things come with years of personal experience.

Open up opportunities for your child to gain new useful knowledge in different areas and discuss with him what you have learned from the experience gained, both together and separately. Help your child make connections between new and old knowledge and ask questions that require extended answers and thoughtful explanations.

Help your child make connections between new and old knowledge and ask questions that require extended answers and thoughtful explanations.

You can also read these tips on how to use cartoons to help your child learn to judge for themselves.

6. Working memory and attention

These two skills are part of a group of skills also known as executive functions. They are different, but closely related.

When children read, attention allows them to absorb information from the text. Working memory helps them retain this information and use it to make sense and gain knowledge from what they read.

The ability to control oneself while reading is also related to executive functions. The child must be able to recognize when he does not understand something, stop, go back and reread, so that there is no doubt about the understanding of what he read.

How to help: There are many ways to help your child improve working memory, and it doesn't have to look like a lesson. There are many games and daily activities that can help develop working memory in a way that your child won't even notice!

There are many games and daily activities that can help develop working memory in a way that your child won't even notice!

To improve your child's concentration, look for reading materials that interest and/or motivate your child. For example, some children love graphic novels. Teach your child to stop and reread the text when something is not clear to him. And show him how you “think out loud” when you read to make sure it makes sense.

More ways to help with text comprehension

When children have difficulty learning the above skills, they may find it difficult to fully understand what they read.

Find out what might be causing your child's reading difficulties. Remember, if a child has difficulty reading, it does not mean that he is not smart. But some children need extra support to successfully develop reading skills. The sooner you contact a specialist or start applying a special corrective technique, the less stress and lag in learning and development your child will receive. Pay attention to the computer technique Fast ForWord, aimed at developing the skills of phonemic perception, decoding, memory, concentration and other executive functions.

Pay attention to the computer technique Fast ForWord, aimed at developing the skills of phonemic perception, decoding, memory, concentration and other executive functions.

Pins

-

Decoding, reading fluency and vocabulary are key skills needed for reading comprehension.

-

Understanding how ideas connect within and between sentences helps children understand the entire text.

-

Reading aloud and discussing experiences can help a child develop reading skills.

Quickly and permanently develop reading skills: decoding, reading comprehension, extracting meaning from context, reading fluency, etc., as well as concentration, memory, information processing - classes using the Fast ForWord online method will help you.

Sign up for trial online classes in Fast ForWord right now!

Don't delay helping your child!

Source

Reading comprehension by schoolchildren and its predictors

Grigorenko

Laboratory of Behavior and Molecular Processes

Yale University 230 South Frontage Road, New Haven, USA, 06518

The article presents the results of two studies of reading comprehension. In the first study (n = 502), coherent text comprehension scores were predicted by single-word reading accuracy scores and phonological scores, which are traditionally considered predictors of single-word reading acquisition. In the second study (n = 1048), measures of connected text comprehension were predicted based on a group of metalinguistic measures. The article discusses the results of the research and draws a parallel between these results and the performance of Russian schoolchildren in the PIRLS and PISA programs.

In the first study (n = 502), coherent text comprehension scores were predicted by single-word reading accuracy scores and phonological scores, which are traditionally considered predictors of single-word reading acquisition. In the second study (n = 1048), measures of connected text comprehension were predicted based on a group of metalinguistic measures. The article discusses the results of the research and draws a parallel between these results and the performance of Russian schoolchildren in the PIRLS and PISA programs.

Keywords: reading, reading comprehension, metalinguistic processes, PISA, PIRLS.

Since receiving the first test results from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2000, it has become clear that Russia, in terms of testing rates for 15-year-old schoolchildren among OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries and their partners, looks unsatisfactory. It turned out that the majority of Russian schoolchildren are significantly behind international standards (that is, from the average indicators of both the OECD countries and other countries participating in PISA). It would seem that these results should disturb both the public and educators and contribute to some kind of change, which, in turn, would increase these indicators of our students in the next rounds of this program. However, the public does not seem to be particularly concerned (or not concerned enough). The last round of PISA was held in 2009and its results were published in December 2010. Unfortunately, the situation has not improved - Russian schoolchildren still show results that are well below the average for OECD countries. Thus, according to the results of the reading literacy test in 2000, Russia was in 28th place (32 countries took part), according to the results of 2003 - in 32-34th (41 participating countries), 37th-40th (56 participating countries), according to the results of 2009 - by 43 (65 participating countries).

It turned out that the majority of Russian schoolchildren are significantly behind international standards (that is, from the average indicators of both the OECD countries and other countries participating in PISA). It would seem that these results should disturb both the public and educators and contribute to some kind of change, which, in turn, would increase these indicators of our students in the next rounds of this program. However, the public does not seem to be particularly concerned (or not concerned enough). The last round of PISA was held in 2009and its results were published in December 2010. Unfortunately, the situation has not improved - Russian schoolchildren still show results that are well below the average for OECD countries. Thus, according to the results of the reading literacy test in 2000, Russia was in 28th place (32 countries took part), according to the results of 2003 - in 32-34th (41 participating countries), 37th-40th (56 participating countries), according to the results of 2009 - by 43 (65 participating countries).

PISA tests are conducted in three areas: reading literacy, math literacy and science literacy. Its purpose is to determine the levels of schoolchildren's skills in applying the knowledge they have received.0003

*Study supported by US NIH (DC007665 and HD052120)

and International Dyslexia Assocaition.

in practice [2]. In addition to these international observations, domestic observations are added, according to which, on average, the level of reading literacy of Russian schoolchildren is falling and does not correspond to the level expected by the modern labor market.

The results of Russian schoolchildren in PISA cause great concern and considerable interest among Russian scientists. Attempts have been made to understand the pattern of schoolchildren's results, and several hypotheses for the reasons for their low values have been published [1]. It is interesting to note that, by their nature, these reasons were formulated at the level of the inability of schoolchildren, at least during the PISA tasks, to flexibly self-organize and apply metacognitive skills when trying to formulate the correct answer. The statement was made that “our students are generally able to read and understand texts and give answers to them in various forms” [1], according to which the spread in psychological processes associated with the ability to read among our students is either not, or it is insignificant. This statement is indirectly confirmed by observations in the process of the international study of 10-year-old schoolchildren PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study - a study conducted every five years by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement) in 2006, where our fourth-graders showed very good results [ 3].

The statement was made that “our students are generally able to read and understand texts and give answers to them in various forms” [1], according to which the spread in psychological processes associated with the ability to read among our students is either not, or it is insignificant. This statement is indirectly confirmed by observations in the process of the international study of 10-year-old schoolchildren PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study - a study conducted every five years by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement) in 2006, where our fourth-graders showed very good results [ 3].

This article considers the assumption that reading comprehension among Russian schoolchildren is not associated with variability in indicators of “low” level processes associated with reading (they can all read, look at the results of the 4th grade!). In other words, this article examines how measures of reading comprehension (i.e., measures essentially identical to those used in the PIRLS and PISA studies) depend on indicators of a "lower" level of information processing (i. e., indicators of phonetic - phonemic, spelling and morphological) not only in elementary school, but throughout the entire school career (i.e. in high school too).

e., indicators of phonetic - phonemic, spelling and morphological) not only in elementary school, but throughout the entire school career (i.e. in high school too).

Reading comprehension is a complex hierarchical process that includes many psychological processes of different levels; the quality and depth of reading comprehension are determined not only by the quality of “high” level cognitive processes (for example, indicators of the processes of extracting critical information from a text, inferential processes, the processes of formulating and testing hypotheses related to finding the correct answer). Accordingly, individual differences in each of these component processes contribute to the overall spread scores for reading comprehension indicators. From the point of view of the mechanical vertical structure of reading comprehension, several levels of comprehension are usually distinguished:

1) understanding the meanings of the words being read;

2) understanding the sentences that are made up of these words;

3) understanding the text from these sentences.

Each "subsequent" level implies understanding not necessarily complete, but reaching a certain critical value at the previous level (thus, understanding of a paragraph comes easier if the sentences that make up this paragraph are understood). However, this movement through the levels of understanding is also carried out in the opposite direction. So, if a paragraph contains an unknown word, determining the meaning of this word is easier if the content of the paragraph itself is understood.

In turn, each of these levels of understanding is associated with certain psychological processes that define this level. For example, understanding the meaning of a word is closely related to the phonological, orthographic, and morphological features of that word. With the increase in units of understanding (i.e., with the transition from words to sentences, text, and accompanying them, for example, tables and graphs), the dimension of the space of understanding increases - semantic, syntactic and prosodic characteristics of the text are added. At the same time, the degree and quality of reading comprehension are related to the individual characteristics of the understander (i.e., the level of development of his phonological, spelling, morphological, semantic, syntactic, etc. representations). It is important to note, however, that while there is a general understanding of these dependencies, there are relatively few empirical studies in the literature examining the contribution of these low-level processes, which are sources of individual differences, to reading comprehension. This tendency of ignoring the lower reading processes at higher stages of development is based on research traditions, presented mainly in the Western and cited [3] and developed [4] in the domestic literature. Thus, it is assumed that after completing primary school, the student moves from the stage of learning to read to the stage of reading for learning [10]; in other words, it is assumed that the processes of the "low" level are formed and are no longer sources of individual differences in indicators of reading comprehension.

At the same time, the degree and quality of reading comprehension are related to the individual characteristics of the understander (i.e., the level of development of his phonological, spelling, morphological, semantic, syntactic, etc. representations). It is important to note, however, that while there is a general understanding of these dependencies, there are relatively few empirical studies in the literature examining the contribution of these low-level processes, which are sources of individual differences, to reading comprehension. This tendency of ignoring the lower reading processes at higher stages of development is based on research traditions, presented mainly in the Western and cited [3] and developed [4] in the domestic literature. Thus, it is assumed that after completing primary school, the student moves from the stage of learning to read to the stage of reading for learning [10]; in other words, it is assumed that the processes of the "low" level are formed and are no longer sources of individual differences in indicators of reading comprehension. This article, however, provides evidence that reading comprehension depends on indicators of "low" processes associated with reading; these processes continue to be sources of individual differences as you move from junior to middle to high school and cannot be ignored when trying to understand the paradox of “winning PIRLS and losing PISA” [4].

This article, however, provides evidence that reading comprehension depends on indicators of "low" processes associated with reading; these processes continue to be sources of individual differences as you move from junior to middle to high school and cannot be ignored when trying to understand the paradox of “winning PIRLS and losing PISA” [4].

This last statement about the significance of “low” processes is, of course, not unfounded and is related to the materials (albeit limited) of foreign literature, showing that different aspects of knowledge of the word [17] (not only understanding of its meaning), namely those which are usually studied predominantly in the context of developing early reading skills (i.e. reading ability) remain informative predictors of reading for learning. Among these aspects are knowledge of pronunciation (phonetics and phonology), spelling (spelling), structure (morphology), frequency of occurrence, style (formal or informal is a given word), relationships with other words, etc. [5; eight; 13].

[5; eight; 13].

Consider the results of Study 1, which was conducted in one of the regional centers of the Russian Federation. In total, 502 schoolchildren from 7 to 13 years old took part in the work (average age 9.63 years, sd = 1.18, girls 48.2%). Invitations to participate were distributed only through public schools; participation was carried out only with the permission of the parents.

Schoolchildren were asked to complete four tasks.

Reading comprehension task. A set of paragraphs was used as a reading comprehension test. Paragraph comprehension was assessed by analyzing responses to questions in multiple choice and open-ended questions. Paragraph tasks were aimed at measuring reading skills, assessed in modern large-scale comparative studies (NAEP - National Assessment of Educational Progress, PIRLS, PISA, conducted in the USA), namely: the ability to selectively extract information; integrate and interpret information; draw conclusions based on the information received; correlate information with one's own point of view, interests, motives, etc. The difficulty levels of paragraphs were controlled according to the Russian language training program (http://www.edusite.ru/p135aa1.html). Open tasks were processed according to specially designed headings using a 5-point rating scale. All raters (evaluators) were specially trained for the evaluation process in such a way that the consistency of their ratings with the ratings of the coach and at least one other rater reached 70%. To obtain a reading comprehension score, a measurement model was used that included three factors: the level of ability of the test-taker, the level of task complexity, and the rater factor. The FACETS package [15] was used to parameterize these factors.

The difficulty levels of paragraphs were controlled according to the Russian language training program (http://www.edusite.ru/p135aa1.html). Open tasks were processed according to specially designed headings using a 5-point rating scale. All raters (evaluators) were specially trained for the evaluation process in such a way that the consistency of their ratings with the ratings of the coach and at least one other rater reached 70%. To obtain a reading comprehension score, a measurement model was used that included three factors: the level of ability of the test-taker, the level of task complexity, and the rater factor. The FACETS package [15] was used to parameterize these factors.

Reading single words aloud. Schoolchildren were presented with isolated words containing two to four syllables on cards. 18 words were words varying in frequency of occurrence (words of the Russian language with high, medium and low frequency). 15 words were pseudowords, i.e. words whose alphabetic composition corresponded to the rules of the Russian language, but at the same time these words did not make sense. After each card was presented, the number of errors was counted.

After each card was presented, the number of errors was counted.

Phonetic-phonemic awareness (PFO). The students were read words one at a time (40 words in total) and asked them to delete certain syllables or letters in these words and pronounce the resulting word. The number of errors was counted.

Fast automated naming (BAN). Schoolchildren were shown four consecutive cards (five rows of 10 drawings in each row) of repeating colors, objects, numbers and letters. They were asked to sequentially name all the colors, objects, numbers and letters on the map. The total time spent on each card was recorded. Here, however, only the average time spent on the card is analyzed.

All tasks were presented individually, in a separate room of the school where the tested student studied.

In tab. 1 presents the descriptive characteristics of the studied variables and the correlations between them.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics of variables in Study 1 and correlations between them

Variables Descriptive characteristics Correlations

minimum maximum mean. value std. deviation (1) (2) (3) (4)

value std. deviation (1) (2) (3) (4)

(1) Reading comprehension -3.61 2.07 0.20 1.03 1.26 -.44 -.24

(2) Single word reading 0 33 29.86 3.24 .26 1 -.49-.29

(3) FFO, errors 0 40 7.41 5.38 -.44 -.49 1.39

(4) BAN, sec. 23 85 40.72 8.03 -.24 -.29 .39 1

Zeros in correlation coefficients are omitted; all correlations are statistically significant at p < 0.001.

Analysis of the correlation matrix showed that all variables are related to each other. However, collinearity analysis in the context of regression analysis convincingly demonstrated that none of the variables is a linear combination of other variables (the minimum tolerance value was 0.741 and the maximum VIF value was 1.350). Regression analysis was carried out by the method of stepwise analysis "forward". It should be noted that of the five independent variables introduced into the analysis (age, gender, number of errors in reading single words, FFO and BAN), only three variables were retained (age, FFO and BAN), however, these three variables explained a fairly large number of variance in the indicator of reading comprehension - 23. 0% (F = 49.27, p < 0.001). Of these 23%, the FFO variable explained 19.0% of the variability (FA = 115.94, p < 0.001), the age variable explained 3.0% (FA = 19.46, p < 0.001), and the BAN variable accounted for 1 .0% (F = 6.48, p < 0.01). The final model, including all three variables, showed the following coefficients: t = -0.39 (t = -8.91, p < 0.001), t = -0.19 (t = -4.67, p < 0.001), and c = -0.11 (t = -2.55, p < 0.01) for FFO, age, and BAN, respectively.

0% (F = 49.27, p < 0.001). Of these 23%, the FFO variable explained 19.0% of the variability (FA = 115.94, p < 0.001), the age variable explained 3.0% (FA = 19.46, p < 0.001), and the BAN variable accounted for 1 .0% (F = 6.48, p < 0.01). The final model, including all three variables, showed the following coefficients: t = -0.39 (t = -8.91, p < 0.001), t = -0.19 (t = -4.67, p < 0.001), and c = -0.11 (t = -2.55, p < 0.01) for FFO, age, and BAN, respectively.

Study 2 was conducted in one of the regional centers of the Russian Federation (in the same place where study 1 was conducted). A total of 1048 schoolchildren from 7 to 18 years old took part in it (average age 12.3 years, sd = 2.26, girls 45.4%). Invitations to participate were distributed only through public schools; participation was allowed only with the permission of the parents.

Schoolchildren were asked to complete five tasks.

Reading comprehension task. Study 2 used the comprehension task used in study 1.

Phonetic-phonemic awareness (PFA). Schoolchildren were offered 60 triplets of words, and only one of the words in each trio was a real word and sounded like a real word (it had to be chosen, for example: pontse, sontse, sonek). In the resulting indicator, the number of correct answers was counted.

Orthographic awareness (OS). Schoolchildren were offered a task based on the so-called spelling choice problem [18], a task that allows assessing quick access to the correct spelling representation of words even in the presence of phonological pseudocopies of these words. This task contained 45 verbal trios (eg milk, milko and maloco). In the resulting indicator, the number of correct answers was counted.

Morphological awareness (MO). The morphology task (M) [6] consisted of two parts: word inflection task (28 tasks for inflectional morphology) and word decomposition task (28 tasks for derivational morphology). The resulting indicator counted the number of correct answers in both types of tasks.

Spelling task. This task included 56 tasks; in these tasks, in order to write a word grammatically correctly, it is necessary to understand the context of the sentence in which this word is given. The resulting indicator counted the number of errors made during the performance of this task.

All tasks were group tasks. Testing was conducted in the schools where the study participants studied.

2 presents the descriptive characteristics of the variables used and the correlations between them.

Analysis of the correlation matrix showed that all variables are related to each other. However, collinearity analysis in the context of regression analysis demonstrated that none of the variables is a linear combination of other variables (the minimum tolerance value was 0.378 and the maximum VIF value was 2.647).

Table 2

Descriptive statistics of variables in study 2 and correlations between them

Variables Descriptive characteristics Correlations

minimum maximum avg. significant. std. deviation (1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

significant. std. deviation (1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

(1) Comprehension -3.21 2.41 0.00 1.00 1 .29 .39 .45 -.38

read

( 2) FFO, correct 0 60 48.46 10.82 .29 1.41 .45 -.39

answers

(3) OO, correct 0 45 34.16 5.58 .39 .41 1 .66 - .64

answers

(4) MO, correct 0 55 40.79 10.26 .45 .45 .66 1 -.73

answers

(5) Spelling, 0 59 10.40 8.23 - .38 -.39 -.64 -.73 1

errors

Note. Zeros in correlation coefficients are omitted; all correlations are statistically significant at p < 0.001.

As in study 1, the regression analysis was carried out using the forward step analysis method. Of the six explanatory variables entered into the analysis (age, gender, FFO, GR, MO, and spelling scores), five variables (all but sex indicator) were retained. A five-variable model,

, explained 24.3% of the variance in the reading comprehension indicator (F = 66.61, p < 0.001). Of these 24.3%, the MO variable explained 20. 5% of the variability (FV = 263.41, p < 0.001), the OD variable explained 1.3% (FV = 17.39).= 2.97, p < 0.005) and v = -0.11 V = -2.59, p < 0.01) for MO, OO, age, FFO, and spelling index, respectively.

5% of the variability (FV = 263.41, p < 0.001), the OD variable explained 1.3% (FV = 17.39).= 2.97, p < 0.005) and v = -0.11 V = -2.59, p < 0.01) for MO, OO, age, FFO, and spelling index, respectively.

Discussion and conclusions

It is well known that the requirements for reading comprehension increase from grade to grade in secondary school in such a way that by the time a student moves from primary to secondary school, the student uses reading as one of the main methods of learning and self-education. With an increase in the degree of difficulty of the texts that the student encounters, the requirements for understanding what is read increase. Thus, both coefficients β obtained for the indicator of age in both Study 1 and Study 2 were negative. This indicates that with the inevitable increase in the degree of complexity of tasks, the indicators of high school students on the scale of latent ability were lower than those of younger students. This phenomenon of gaps in the developmental trajectory (when younger children, contrary to the laws of development, do something better than older children) suggests that the development of reading skills seems to be non-linear and requires careful study of the issue. It is obvious that high school students come to the task of understanding texts with gaps in some requirements. These requirements include extracting information from texts, processing and interpreting information, formulating inferences, and relating what is read to the values, interests, and motives of the reader. All this implies the constant development and improvement of complex "high" cognitive processes - the so-called metacognitive functions (thinking, control-performing cognitive functions, self-regulation processes, etc.). However, at the same time, the role and importance of the “low” level functions that underlie the acquisition of reading skills at its early stages (the so-called metalinguistic functions of phonetic-phonemic, spelling, morphological, syntactical awareness) do not disappear; these features remain important predictors of reading comprehension scores even when it comes to interacting with complex texts.

It is obvious that high school students come to the task of understanding texts with gaps in some requirements. These requirements include extracting information from texts, processing and interpreting information, formulating inferences, and relating what is read to the values, interests, and motives of the reader. All this implies the constant development and improvement of complex "high" cognitive processes - the so-called metacognitive functions (thinking, control-performing cognitive functions, self-regulation processes, etc.). However, at the same time, the role and importance of the “low” level functions that underlie the acquisition of reading skills at its early stages (the so-called metalinguistic functions of phonetic-phonemic, spelling, morphological, syntactical awareness) do not disappear; these features remain important predictors of reading comprehension scores even when it comes to interacting with complex texts.

There are several reasons for maintaining this dependence. First, the reading of single words itself, which, by definition, is a predictor of reading comprehension, is formed as a skill based on metalinguistic indicators. It is interesting, however, to note that, as shown in Study 1, when both the single word reading scores and the metalinguistic process scores “meet” in the same regression equation, the single word reading score

First, the reading of single words itself, which, by definition, is a predictor of reading comprehension, is formed as a skill based on metalinguistic indicators. It is interesting, however, to note that, as shown in Study 1, when both the single word reading scores and the metalinguistic process scores “meet” in the same regression equation, the single word reading score

is displaced, while the metalinguistic score (in the study 1 — phonetic-phonemic awareness) remains statistically significant (p < 0.001) and significant (explaining 19% variance). This observation corresponds to the data obtained in foreign psychology [21; 22].

Second, as shown in study 2, both the statistical significance and the significance of the contributions of various metacognitive components are preserved at all stages of school education. In addition, these data are also consistent with the observations made in foreign psychology [7; 12; fourteen; 16; twenty]. According to these observations, the fact that morphological awareness predicts 20. 5% of the variance in reading comprehension is logical - after graduating from elementary school, all school textbooks contain a large number of morphologically complex and long words [9; 11], and the time of eye fixation on a certain word when interacting with the text (i.e., during the understanding of the text) depends not only on the frequency of occurrence of certain words, but also on the frequency of occurrence of the morphemes that these words make up [19].

5% of the variance in reading comprehension is logical - after graduating from elementary school, all school textbooks contain a large number of morphologically complex and long words [9; 11], and the time of eye fixation on a certain word when interacting with the text (i.e., during the understanding of the text) depends not only on the frequency of occurrence of certain words, but also on the frequency of occurrence of the morphemes that these words make up [19].

Thirdly, although this issue was not discussed in this work, it is extremely important to note the “reverse” regulation from a developed reading skill to metalinguistic processes. It is likely that the morphological awareness that is an effective predictor of understanding is not the morphological awareness on the basis of which the skill of reading single words was formed, but another awareness modified under the pressure of the developing reading skill. So, the more a student reads, the more complex morphological forms he comes across and the more intensively his morphological awareness develops.

Thus, the presented data show that the so-called "low-level" metalinguistic processes, which are considered basic in mastering the reading skill at the level of single words, remain significant throughout the school career. Remaining important predictors of both reading at the level of single words and reading comprehension at the level of a coherent text, these metalinguistic processes seem to blur the boundary between reading levels (word, sentence, text), reflecting the conventionality of this division and the real unity of all these components. In other words, understanding where individual differences in reading comprehension come from implies a focus not only on "high-level" but also on "low-level" processes. And in this sense, understanding what happens during the transition from reading comprehension in elementary school to reading comprehension and functional literacy in high school should include the study of not only metacognitive, but also metalinguistic processes.

LITERATURE

[1] Kasprzhak A.G. and others. Russian school education: a view from the outside (psychological and pedagogical analysis of the results of testing Russian teenagers in the international study PISA 2000) // Educational Issues. - 2004. - No. 1. - S. 190-231.

[2] Tsukerman G.A., Ermakova I.V. Developing effects of D.B. Elkonin - V.V. Davydova: a view from the competence approach // Psychological science and education. - 2003. - No. 4. - S. 56-73.

[3] Tsukerman G.A., Kovaleva G.S., Kuznetsova M.I. Do Russian students read well? // Questions of education. - 2007. - No. 4. - S. 240-267.

[4] Tsukerman G.A., Kovaleva G.S., Kuznetsova M.I. Victory in PIRLS and defeat in PISA: the fate of the reading literacy of 10-15-year-old schoolchildren // Problems of Education. - 2011. - No. 2. - S. 123-150.

[5] Arndt E., Foorman B. Second graders as spellers: What types of errors are they making? // Assessment for Effective Instruction. - 2010. - Vol. 36. - P. 57-67.

- Vol. 36. - P. 57-67.

[6] Carlise J.F. Awareness of the structure and meaning of morphologically complex words: Impact on reading // Reading and Writing. - 2000. - Vol. 12. - P. 169-190.

[7] Carlisle J.F. Awareness of the structure and meaning of morphologically complex words: Impact on reading // Reading and Writing. - 2000. - Vol. 12. - P. 169-190.

[8] Carlisle J.F., Stone C.A. Exploring the role of morphemes in word reading // Reading Research Quarterly. - 2005. - Vol. 40. - P. 428-449.

[9] Chafe W., Danielewicz J. Properties of spoken and written language // Comprehending oral and written language / ed. R. Horowitz, J. Samuels. - San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1987. - P. 83-113.

[10] Chall J.S. Stages of reading development. — Orlando, FL: Harcourt-Brace, 1983/1996.

[11] Coxhead A. A new academic word list // TESOL Quarterly. - 2000. - Vol. 34. - P. 213-238.

[12] Deacon S.H., Kirby J.R. Morphological awareness: Just—more phonological? The roles of morphological and phonological awareness in reading development // Applied Psycholinguistics. - 2004. - Vol. 25. - P. 223-238.

- 2004. - Vol. 25. - P. 223-238.

[13] Foorman B., Petscher Y. Development of spelling and differential relations to text reading in grades 3–12 // Assessment for Effective Instruction. - 2010. - Vol. 36. - P. 7-20.

[14] Kieffer M.J., Lesaux N.K. The role of derivational morphology in the reading comprehension of Spanish-speaking English language learners // Reading and Writing. - 2008. - Vol. 21. - P. 783-804.

[15] Linacre J.M. Facets Rasch measurement computer program. — Chicago, IL: Winsteps.com, 2004.

[16] Nagy W., Berninger V., Abbott R. Contributions of morphology beyond phonology to literacy outcomes of upper elementary and middle-school students // Journal of Educational Psychology. - 2006. - Vol. 98. - P. 134-147.

[17] Nagy W., Scott J. Vocabulary processing // Handbook of reading research / ed. M.L. Kamil, P.D. Pearson, E.B. Moje, P. Afflerbach. - Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2000. - Vol. 3. - P. 269-284.

[18] Olson R.K., Forsberg H. , Wise B.W., Rack J. Genes, environment and the development of orthographic skills // The varieties of orthographic knowledge / ed. V. Beringer. — Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer, 1994. - P. 27-72.

, Wise B.W., Rack J. Genes, environment and the development of orthographic skills // The varieties of orthographic knowledge / ed. V. Beringer. — Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer, 1994. - P. 27-72.

[19] Rayner K., Pollatsek A., Ashby J., Clifton C. Psychology of reading. — New York, NY: Psychology Press, 2011.

[20] Tong X. et al. Morphological awareness: A key to understanding poor reading comprehension in English // Journal of Educational Psychology. - 2011. - Vol. 103. - P. 523-534.

[21] Kim Y.-S. Proximal and distal predictors of reading comprehension: Evidence from young Korean readers // Scientific Studies of Reading. - 2011. - Vol. 15. - P. 167-190.

[22] Schiff R., Schwartz-Nahshon S., Nagar R. Effect of phonological and morphological awareness on reading comprehension in Hebrew-speaking adolescents with reading disabilities // Annals of Dyslexia. - 2011. - Vol. 61. - P. 44-63.

PUPILS' READING COMPREHENSION AND ITS PREDICTORS

Elena L.