Reading skills for 1st graders

How To Help 1st Grader Read Fluently

When our children are first learning to read, we want them to be successful. As a parent, you are likely to try to find out how to help 1st grader read better. By first grade, kids are learning to read full-length books and are able to read longer, more complex sentences.

This means that your child is reading at a more challenging level and might be struggling. Their reading fluency is likely a factor in how well they are understanding a text.

What should a 1st grader be able to read?

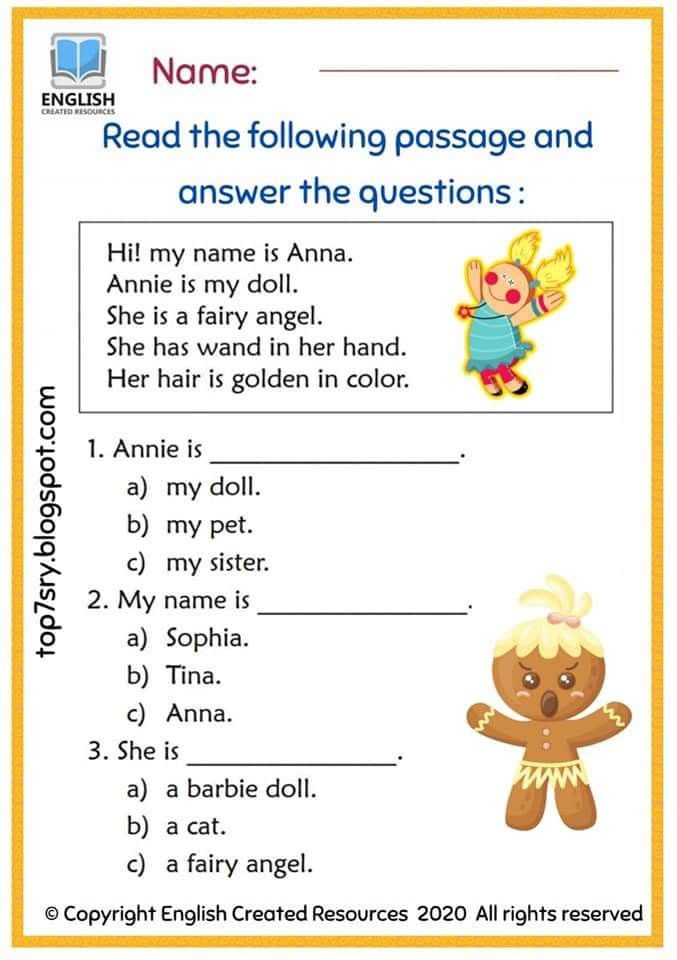

By 1st grade your child should have at least the following variety of reading skills:

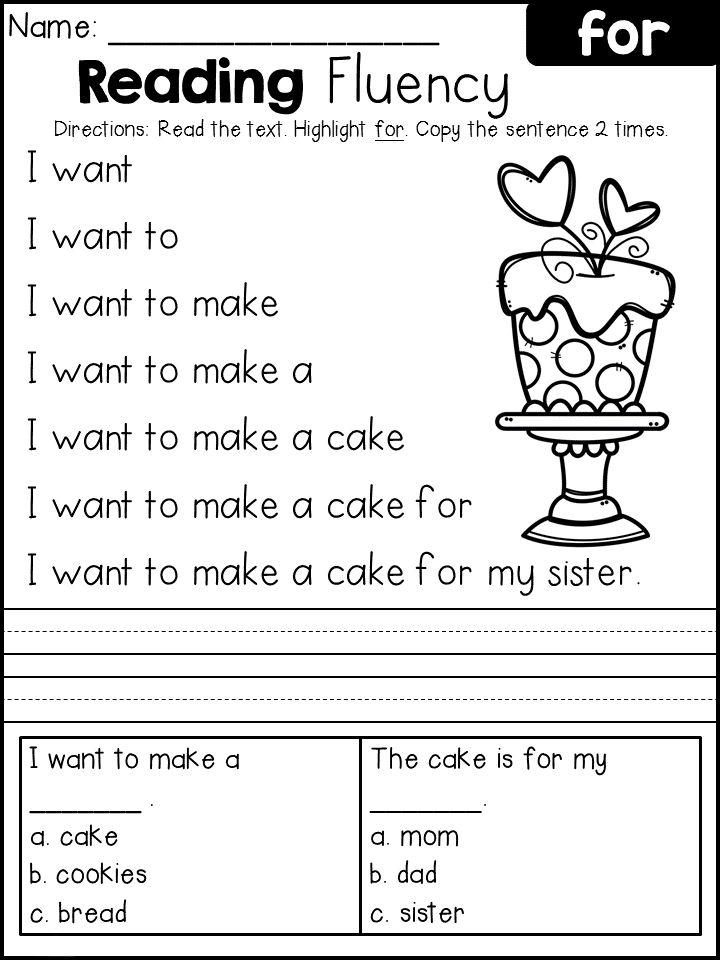

- They should be able to recognize about 150 sight words or high-frequency words.

- They are able to distinguish between fiction and nonfiction texts.

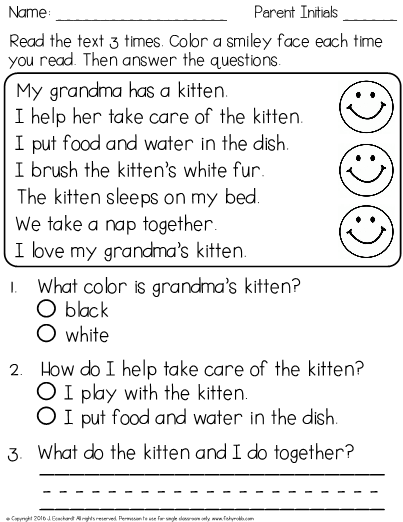

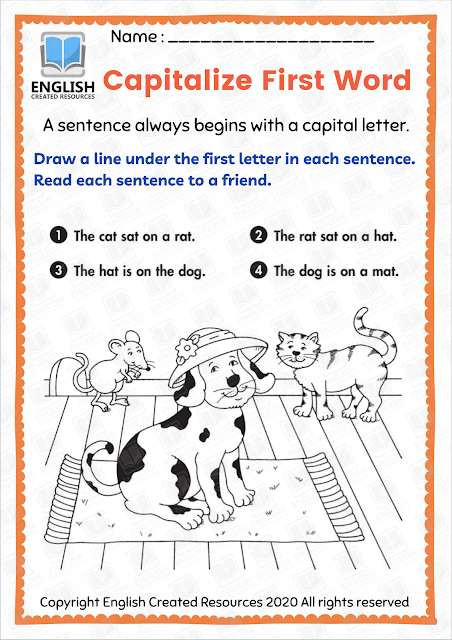

- They should be able to recognize the parts of a sentence such as the first word, capitalization, and punctuation.

- They are able to understand how a final “e” will change the sound of the vowels within a word.

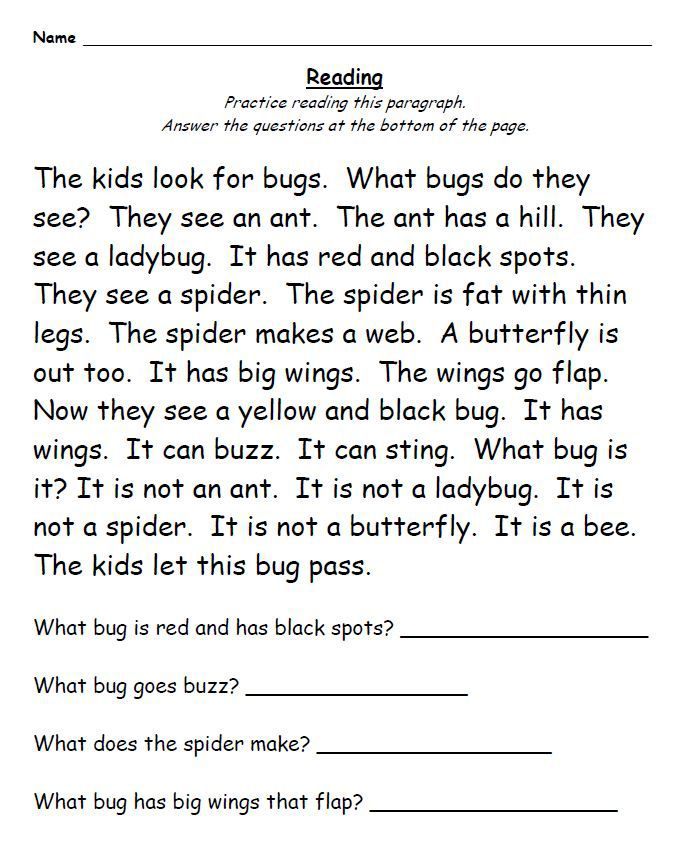

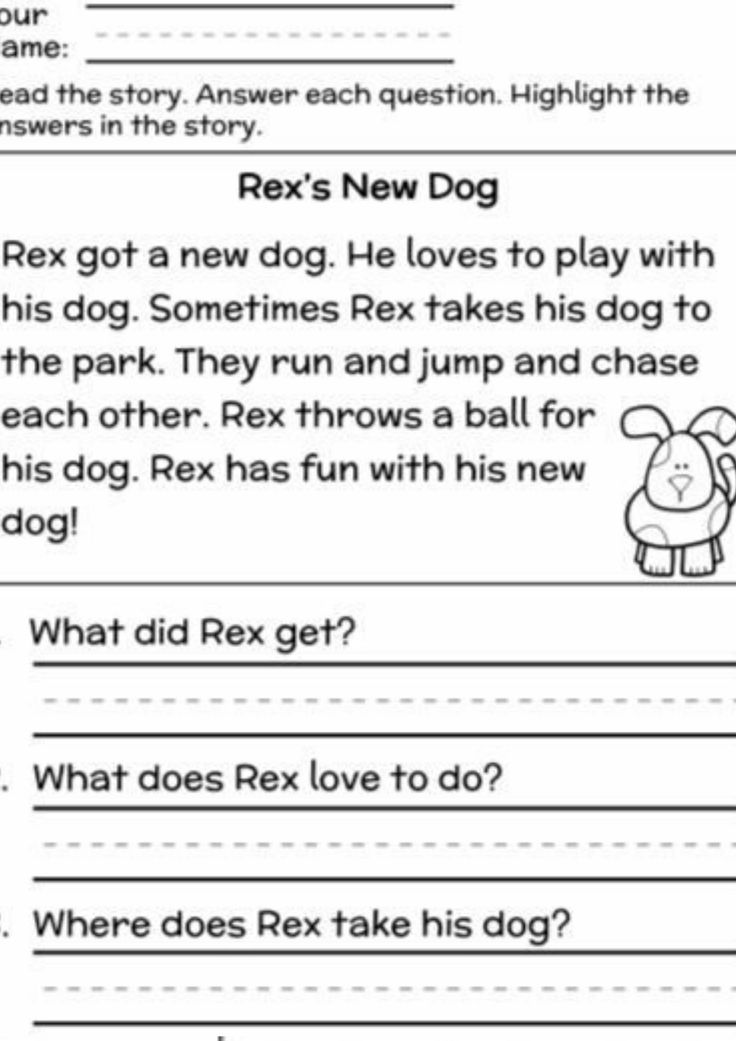

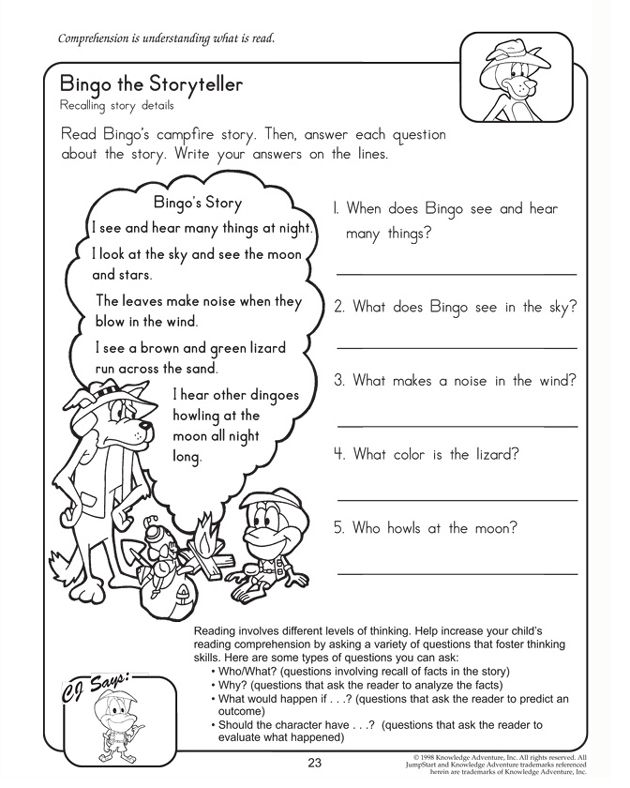

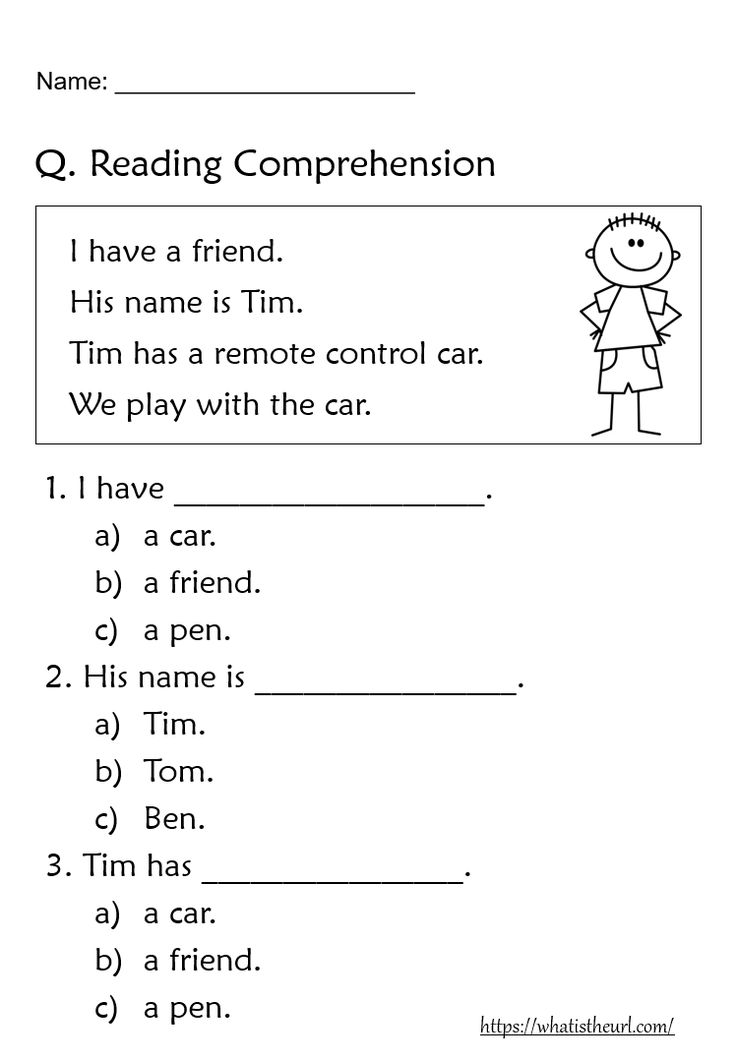

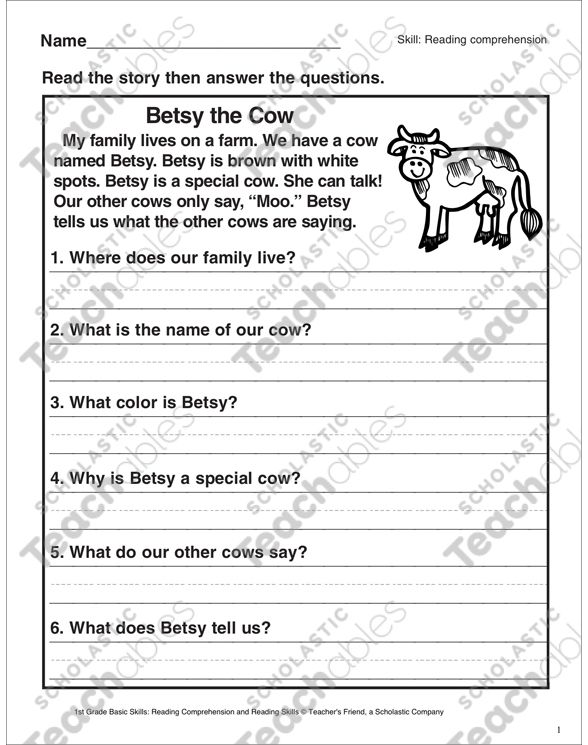

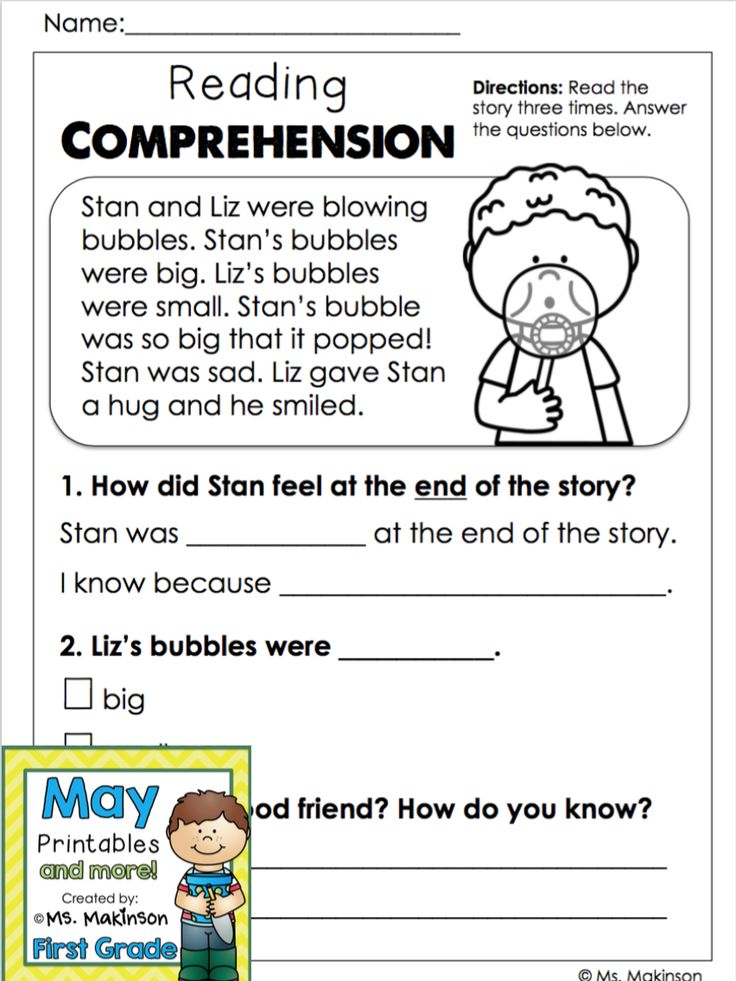

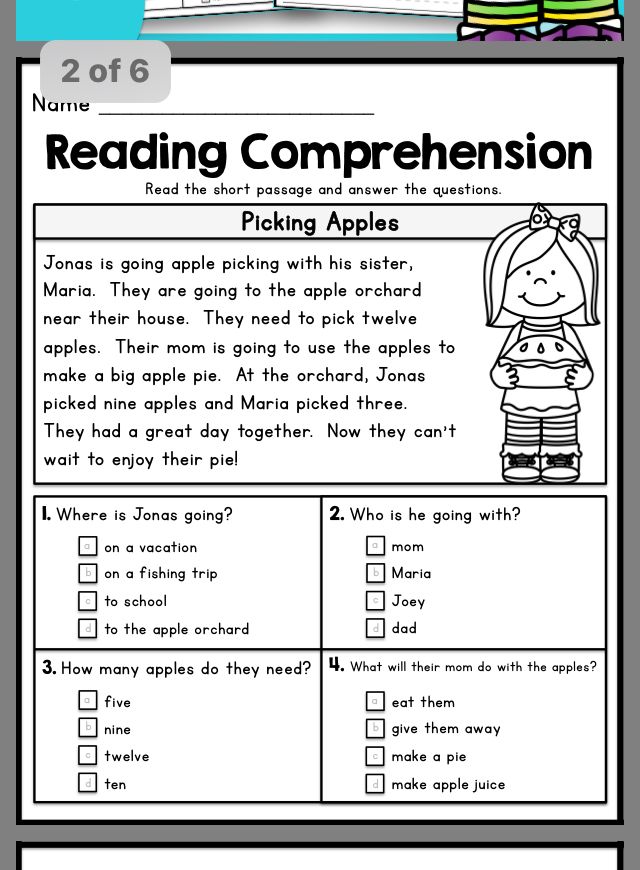

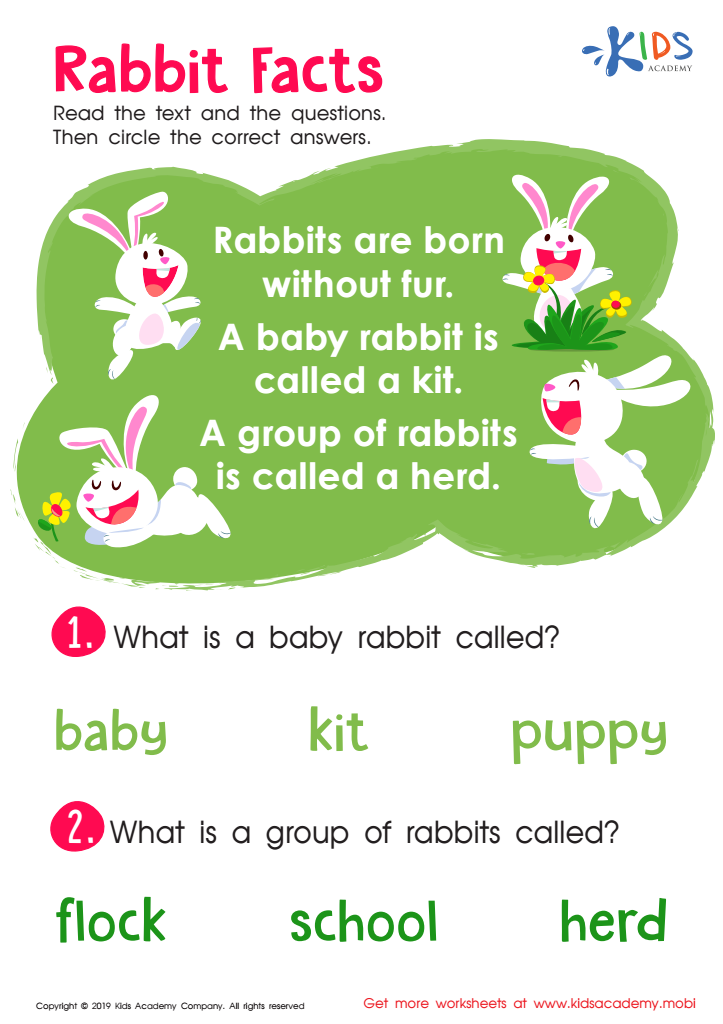

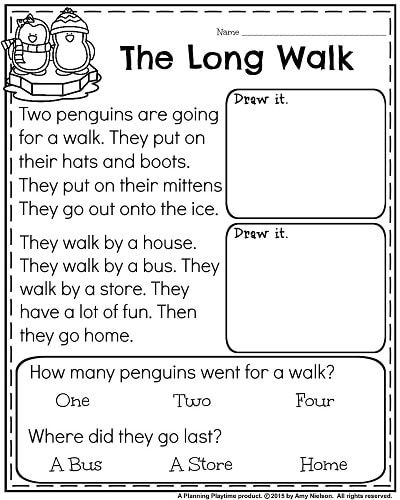

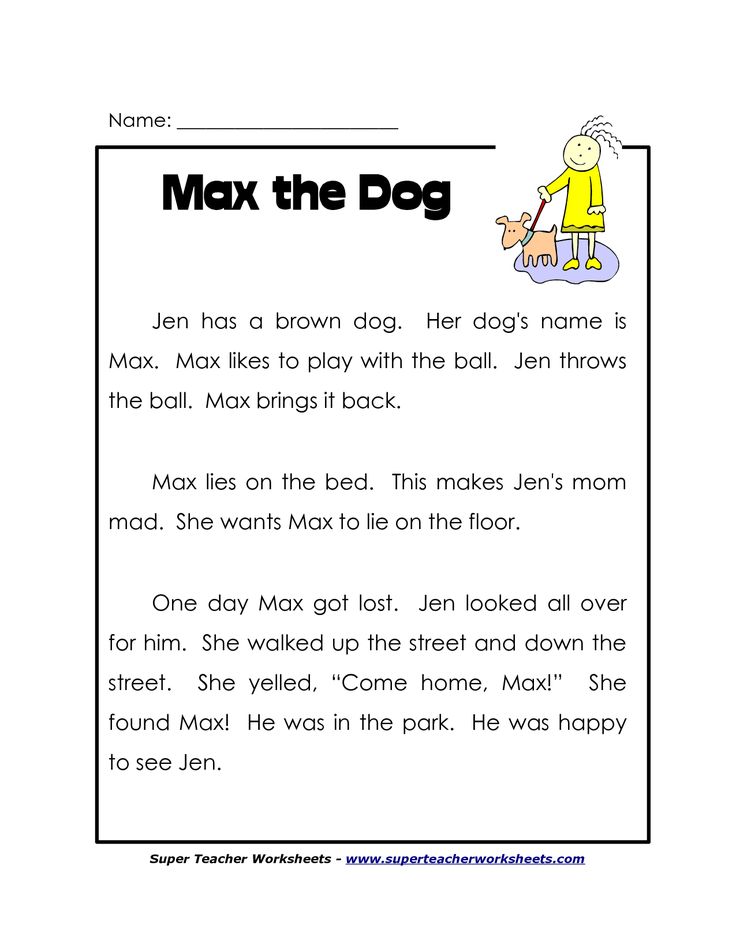

- They are able to answer questions and recall details from a reading.

- They are able to read fluently meaning with speed, accuracy, and prosody.

Your first grader should be able to begin reading the first few levels of graded reader books. A graded reader book is a book that is set at a certain reading level. These books are often used in schools to help measure student progress.

What is fluency in reading?

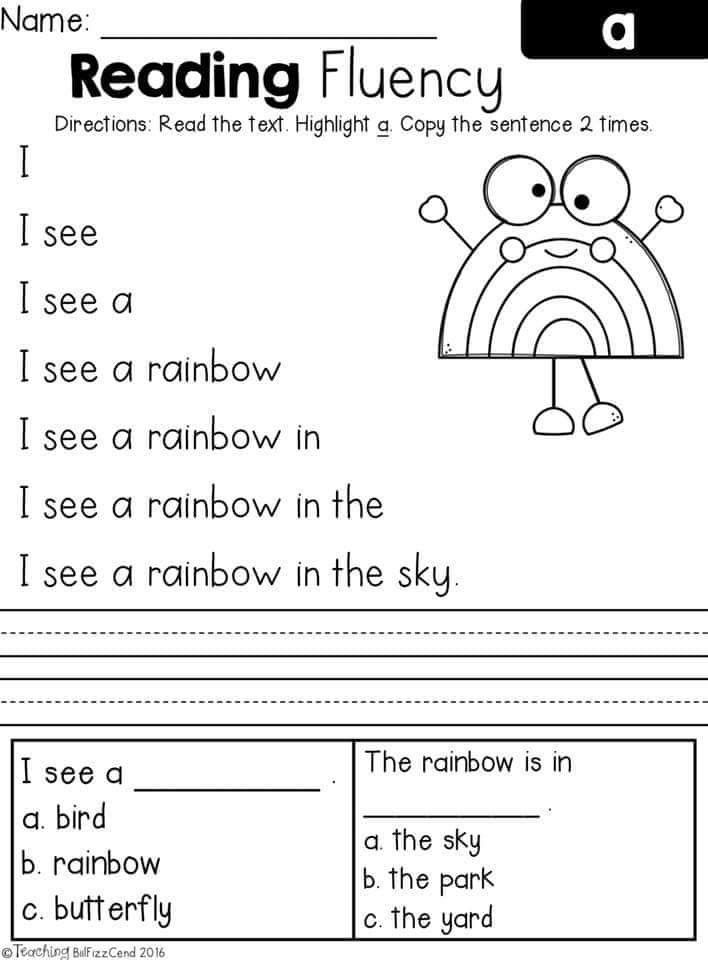

Reading fluency is the ability to “read how you speak”. This means that your child is reading at a conversational pace with appropriate expression. Reading fluency is important because it is directly related to reading comprehension. The more fluent a reader is the better they understand the text.

Fluency in reading relies on speed, accuracy, and prosody. These factors make for a fluent reader and help your 1st grader not only to recognize words but to actually understand and comprehend text.

- Speed – Fluent readers read at a speed that is accurate for their grade level which is 60 words per minute for 1st graders.

- Accuracy – Fluent readers are able to recognize words quickly and have the skills to sound out and decode words they are unfamiliar with.

- Prosody – Fluent readers use expression and intonation to bring meaning into their readings. This is not just recognizing words, but also recognizing that expression also plays a part in understanding.

How can I help my 1st grader with reading fluency?

There are a variety of things you can do at home to help your 1st grader read more fluently:

- Model reading – Children learn best when they have a model showing them the skills they are meant to be learning. Reading to your child regularly provides a model of fluent reading for them.

- Echo Reading – As you and your child read a text, read one sentence then have them read the same sentence out loud. This form of repeated reading helps them see you model fluency then lets them practice it.

- Reader’s theatre – Turn a book into a script and have your kids bring the story to life.

This will help them practice their expression and intonation when they read.

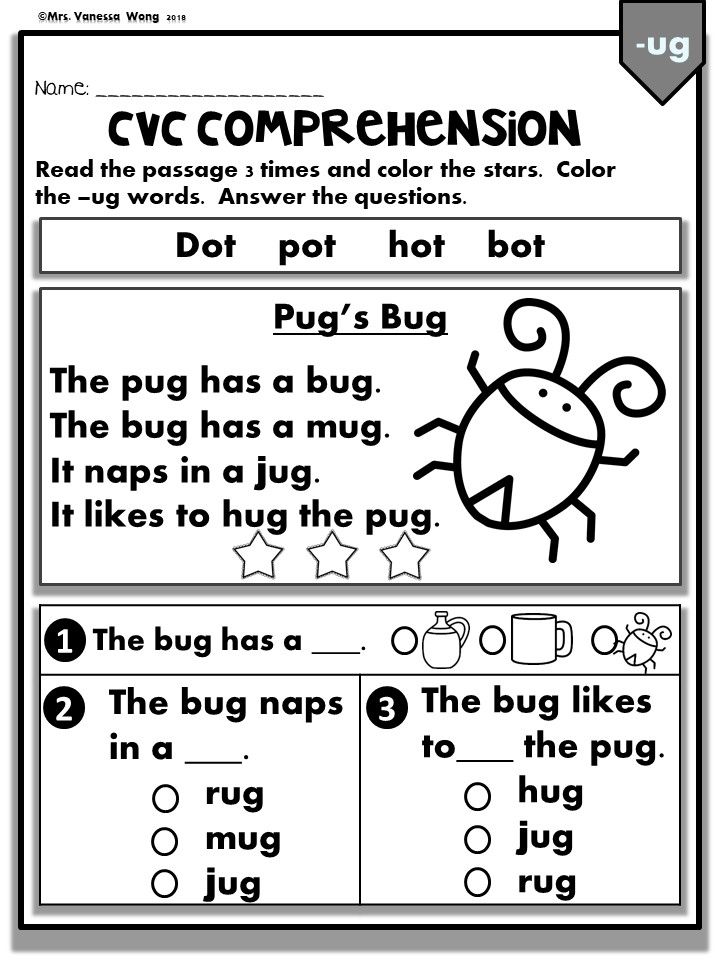

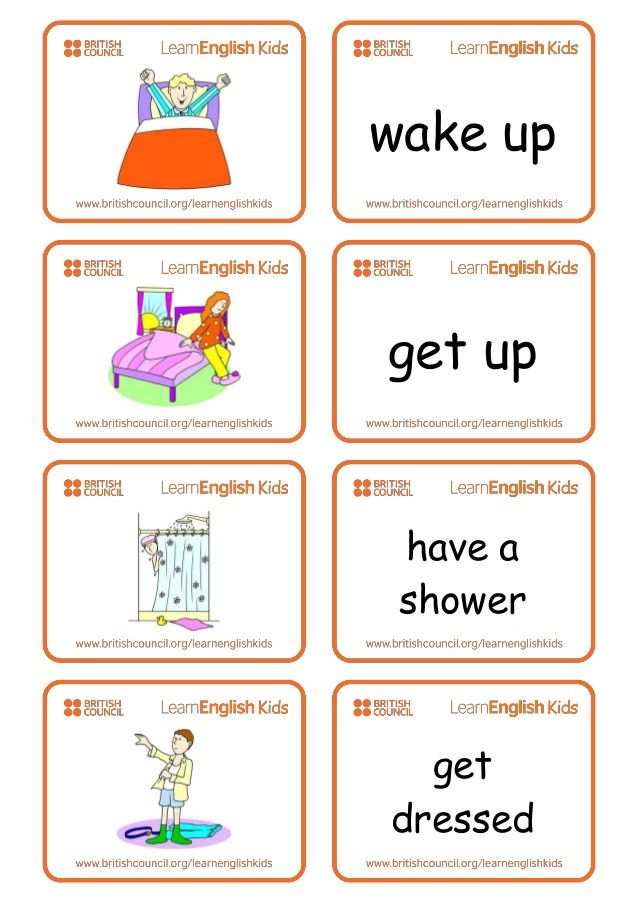

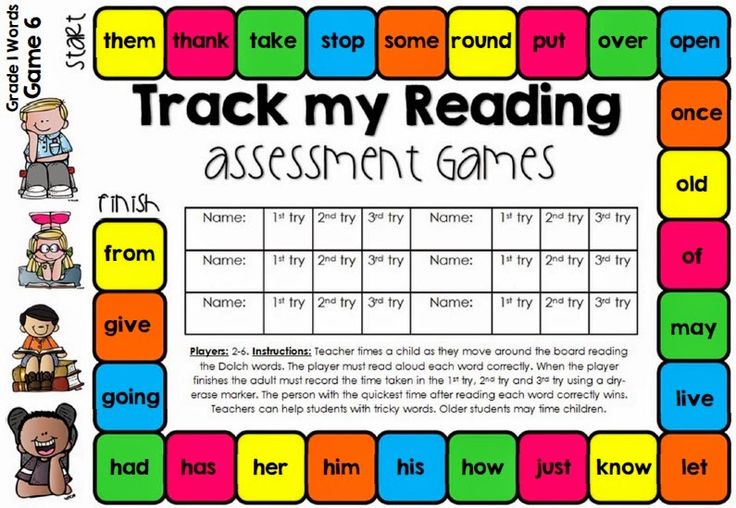

This will help them practice their expression and intonation when they read. - Practice sight words – The more words your child recognizes, the more fluent they will become. Use word games and flashcards to help them learn sight words to help them read less choppy.

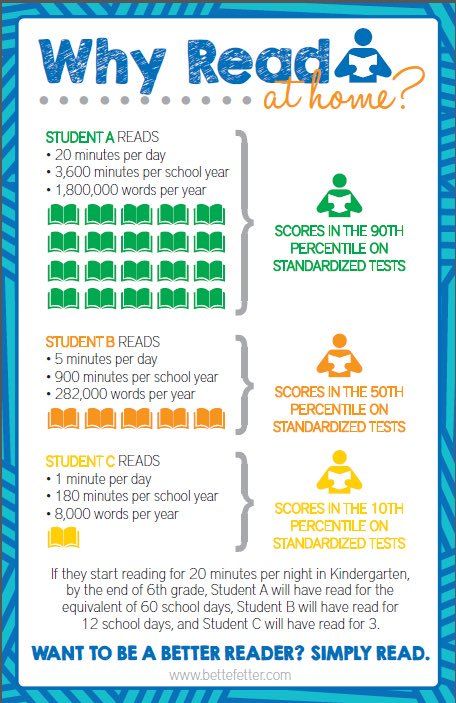

- Extensive reading – The best way to help your 1st grader to read fluently is to get them to read a lot! Provide lots of books of their choice at home and get them to enjoy reading so that they practice often.

- Utilize reading apps – Most kids play with technology already such as tablets and smartphones. Why not incorporate reading into this game time by downloading some reading apps?

Which reading app is helpful for improving fluency?

Readability

is an app that helps improve fluency for emerging readers. The app is a great way to increase fluency for your 1st grader because it uses A.I. technology and speech-recognition to recognize errors your child might be making when reading out loud.

Readability provides a large library of original content that your child can read and is constantly being updated with new stories. The app works like a private tutor by actually listening to your child read out loud and recognizing their errors. It then provides feedback to help them improve. It can also read the material to your child as they follow along.

These forms of repeated reading can help your 1st grader practice their fluency wherever and whenever they want. Try Readability for free!

First grade is critical for reading skills, but some kids are way behind

AUSTIN, Texas — Most years, by the third week of first grade, Heather Miller is working with her class on writing the beginning, middle and end of simple words. This year, she had to backtrack — all the way to the letter “H.”

This story also appeared in USA Today“Do we start at the bottom or do we start at the top?” Miller asked as she stood in front of her class at Doss Elementary.

“Top!” chorused a few voices.

“When I do an H, I do a straight line down, another straight line down and then I cross in the middle,” Miller said, demonstrating on a projector in a front corner of the classroom.

Her 25 students set to work on their own. Some got it right away. One student watched his tablemate before slowly copying down his own H’s. Another tested her own way of writing the letter: one line down, cross in the middle, then another line down. “Your paper is upside down, let’s turn it,” Miller said to a student who was trying to write letters while leaning sideways, almost out of her seat.

A student works on a writing assignment in Heather Miller’s classroom.In classrooms across the country, the first months of school this fall have laid bare what many in education feared: Students are way behind in skills they should have mastered already.

Children in early elementary school have had their most formative first few years of education disrupted by the pandemic, years when they learn basic math and reading skills and important social-emotional skills, like how to get along with peers and follow routines in a classroom.

While experts say it’s likely these students will catch up in many skills, the stakes are especially high around literacy. Research shows if children are struggling to read at the end of first grade, they are likely to still be struggling as fourth graders. And in many states with third grade reading “gates” in place, students could be at risk of getting held back if they haven’t caught up within a few years.

40 percent — The number of first grade students “well below grade level” in reading in 2020, compared with 27 percent in 2019, according to Amplify Education Inc.

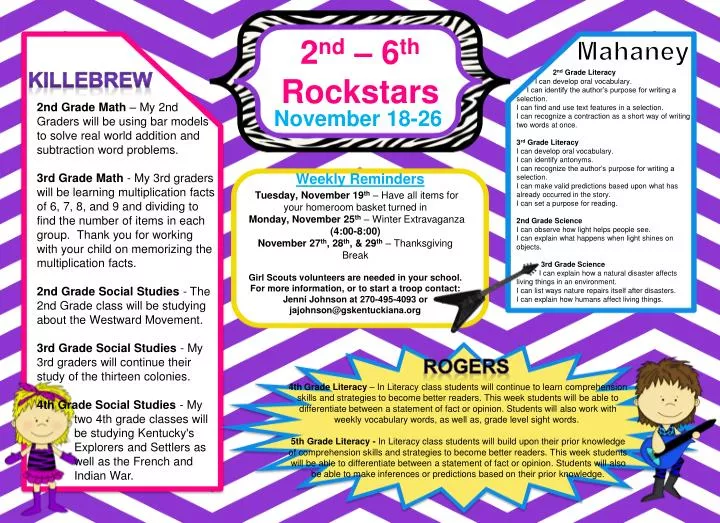

First grade in particular — “the reading year,” as Miller calls it — is pivotal for elementary students, when their literacy skills “really take off.” Kindergarten focuses on easing children from a variety of educational backgrounds — or none at all — into formal schooling. In contrast, first grade concentrates on moving students from pre-reading skills and simple math, like counting, to more complex skills, like reading and writing sentences and adding and subtracting numbers.

By the end of first grade in Texas, students are expected to be able to mentally add or subtract 10 from any given two-digit number, retell stories using key details and write narratives that sequence events. The benchmarks are similar to those used in the more than 40 states that, along with the District of Columbia, adopted the national Common Core standards a decade ago.

Teachers often see a range of literacy skills, and that could be more pronounced this year due to the pandemic

Teacher Heather Miller has seen a wide range of writing skills among her first grade students, with some students already writing complex sentences while others are still working on letter formation. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller has already seen improvement in writing, including among students who started the year without a strong grasp of forming letters. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller’s students frequently write in notebooks to show their progress in writing skills. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller’s students frequently write in notebooks to show their progress in writing skills. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger Report

Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller’s students frequently write in notebooks to show their progress in writing skills. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger Report“They really grow as readers in first grade, and writers,” Miller said. “It’s where they build their confidence in their fluency.”

But about half of Miller’s class of first graders at Doss Elementary, a spacious, bright, newly built school in northwest Austin, spent kindergarten online. Some were among the tens of thousands of children who sat out kindergarten entirely last year.

More than a month into this school year, Miller found she was spending extensive time on social lessons she used to teach in kindergarten, like sharing and problem-solving. She stopped class repeatedly to mediate disagreements. Finally, she resorted to an activity she used to use in kindergarten: role-playing social scenarios, like what to do if someone accidentally trips you.

“My kids are so spread out in their needs … there’s so much to teach, and somehow there’s not enough time.

Heather Miller, first grade teacher”

“So many kids are missing that piece from last year because they were, you know, virtual or on an iPad for most of the time, and they don’t know how to problem-solve with each other,” Miller said. “That’s just caused a lot of disruption during the school day.”

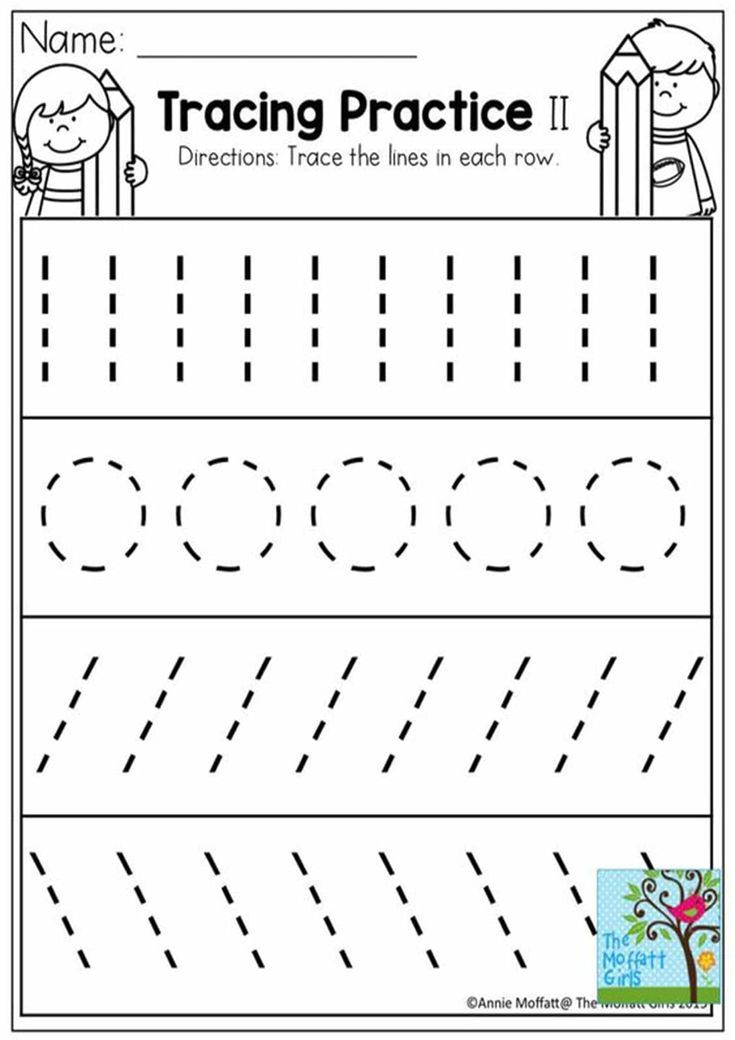

Her students were also not as independent as they had been in previous years. Used to working on tablets or laptops for much of their day, many of these students were also behind in fine motor skills, struggling to use scissors and still working on correctly writing numbers.

Related: What parents need to know about the research on how kids learn to read

Instead of working on first grade standards, Miller was devoting time on this Friday morning in early September to forming upper- and lowercase letters, a kindergarten standard in Texas and the majority of other states. As students finished practicing the letter H, they moved on to the assignment at the bottom of the page: Draw a picture and write a word describing something that starts with an H.

“H-r-o-s” one student wrote next to a picture of a horse standing on green grass in front of a light blue sky. “H-e-a-r-s” another student wrote next to a picture of a strip of brown hair, floating in the white picture box. “You should draw a face there,” suggested his tablemate, pointing at the blank space under the hair.

Students work on a phonics activity during center time in Heather Miller’s classroom. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportMiller’s first graders are a case study in the scale, depth and unevenness of learning loss during the pandemic. One report by Amplify Education Inc., which creates curriculum, assessment and intervention products, found children in first and second grade experienced dramatic drops in grade level reading scores compared with those in previous years.

In 2020, 40 percent of first grade students and 35 percent of second grade students were scoring “well below grade level” on a reading assessment, compared with 27 percent and 29 percent the previous year. That means a school would need to offer “intensive intervention” to nearly 50 percent more students than before the pandemic.

That means a school would need to offer “intensive intervention” to nearly 50 percent more students than before the pandemic.

Data analyzed by McKinsey & Company late last year concluded that children have lost at least one and a half months of reading. Other data show low-income, Black and Latinx students are falling further behind than their white peers, leading to worsening achievement gaps.

Experts say it’s now clear families who had time and resources to help their children with academics when schooling was disrupted had a tremendous advantage.

“Higher-income parents, higher-educated parents, are likely to have worked with their children to teach them to read and basic numbers, and some of those really basic early foundational skills that kids generally get in pre-K, kindergarten and first grade,” said Melissa Clearfield, a professor of psychology who focuses on young children and poverty at Whitman College.

“Families who were not able to, either because their parents were essential workers or children whose parents are significantly low-income or not educated, they’re going to be really far behind. ”

”

What Miller has observed in the first few weeks of the school year is likely taking place in classrooms nationwide, experts say. In April, researchers with the nonprofit NWEA, which develops pre-K-12 assessments, predicted how the pandemic’s disruptions would manifest among the kindergarten class of 2021: a wider range of ability levels; large class sizes with more diverse ages because some parents held children back a grade; and students unfamiliar with in-person classroom routines.

“We predicted that there would be a lot of diversity in skills,” said Brooke Mabry, strategic content design coordinator for NWEA Professional Learning. That includes skills related to academics, social-emotional learning and executive functioning, she added.

The varying experiences children had with school last year also impacted fine motor skill development, independence, ability to navigate conflicts and the “unfinished learning” teachers are now observing, she added.

Related: Remote learning a bust? Some families consider having their child repeat kindergarten

While switching to remote learning was hard on many students, younger students were generally unable to log themselves on to a computer independently and focus on virtual lessons for extended periods of time. Teachers, who usually rely on small, in-person groups for early literacy skills, instead had to teach letters, sounds and sight words via online platforms.

Miller had the unwieldy task of teaching kids both in person and online, spending her year pivoting between students in front of her and students on her computer screen, using her projector to display books to students at home and teaching reading skills via virtual groups.

Now, with students in front of her again, Miller was finding that those online lessons weren’t as useful as many had hoped.

Miller, 30, is a calm, confident teacher who is in her eighth year of teaching and her second at Doss. She usually has students with a wide range of ability levels at the beginning of the year, although Doss is relatively affluent. Nearly 62 percent of students at the school are white, and fewer than 20 percent are economically disadvantaged, compared with the district average of nearly 53 percent. In 2019, 95 percent of Doss’ students passed the state reading assessment.

Students play outside Doss Elementary in Austin, Texas. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportBut this year, Miller saw larger gaps in reading skills than ever before. Usually, her first graders would start with reading levels ranging from mid-kindergarten to second grade. This year, the levels spanned early kindergarten up to fourth grade.

“My kids are so spread out in their needs,” Miller said. “I just feel like — and I’m sure every teacher feels like this — there’s so much to teach, and somehow there’s not enough time.”

“I just feel like — and I’m sure every teacher feels like this — there’s so much to teach, and somehow there’s not enough time.”

She’s also seen higher literacy levels for kids who went to school in person last year. To her, it speaks to the immense benefits kids get from all aspects of in-person learning. “It just shows how important it is for these kids to be around their peers and just have normalcy,” she said.

Related: Summer school programs race to help students most in danger of falling behind

To catch kids up, Miller is relying on, among other things, one of the staples of the early elementary classroom: center time. For two hours a day, she works with small groups of students on the specific math and reading skills they are lacking.

On a recent October morning, Miller divided her class into five groups to rotate through various activities around her room. She gave her students a few minutes to finish a writing assignment as she pulled out several sets of small books at various reading levels; colorful plastic, hollow phones so her students could hear themselves read; and for a group of struggling readers, a matching game featuring cards showing various letters and pictures.

“I feel like I’m teaching four grades,” Miller said as she arranged the materials on her desk.

Several minutes later, seated at a table in the back of the room with five of her grade-level readers, Miller handed them each a phone, a small book and a green witch’s finger to help them point at the words in the book. “Today we’re going to talk about our reading tools,” Miller said, holding up a blue plastic phone. “These are called whisper phones. You whisper so you can hear yourself sound out the words,” she said. “Do these go on our heads?”

“No!” the students said, giggling.

“You know what these are for?” she said, holding up a rubber finger.

“Um, they’re for reading,” one student said. “’Cause I had them in kindergarten.”

“Very good. Are these for picking your nose?” Miller asked.

“No!” the students said, laughing.

She placed a book in front of each child and walked them through a series of exercises, including looking at the cover and predicting what the book would be about.

Then, they opened their books and began to read in a whisper. Miller turned from one side of the table to the other, listening as students read to themselves, pointing at each word with their green rubber fingers. She helped them sound out challenging words, like “away.” One by one, the students finished the book. A few read it several times in the minutes allotted.

Students practice reading using whisper phones during center time in their first grade classroom. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportMiller’s next group, all of whom were reading far below grade level, required a different activity. Rather than handing out a book, Miller pulled out a letter-matching game at the table, using materials she had from her days as a kindergarten teacher. She placed two small laminated cards on the table, one showing the letter D and a picture of a dog, and one with the letter B and a picture of a ball.

“We’re going to do your letters today,” Miller said to the group. “What letter is this?” she asked, pointing to the B.

“Ball!” one student responded.

“What letter?” Miller asked again. There was a pause.

“B!” another student responded.

“What sound does it make?”

“Buh,” a third student said.

The students ran through the activity, looking at pictures of items starting with B and D like a doll, ball, dog and dolphin, and sorting them into piles based on the starting letter.

A student reads a book during center time in Heather Miller’s classroom. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportExperts like Clearfield say finding new or different strategies to help students learn grade-level content after the last 18 months will be critical, even if that means pulling out activities typically used by lower grade levels, as Miller did with her lowest reading group.

It also may mean recruiting help from outside the classroom. Miller said Doss already had a strong team of interventionists to rely on, and several of her students receive extra reading help during the day.

Miller has also found it helpful to work with her fellow first grade teachers to solve a shared academic challenge. This fall, the first grade teachers all discovered that many of their students were behind in reading sight words. They began meeting regularly to share tips and strategies to combat this.

Despite the obvious need to catch kids up, Miller has been mindful of not coming on too strong with remediation efforts. “I don’t want to push them so hard where they get burned out,” she said on an October evening. “They’ve been through so much.”

Related: We know how to help young children cope with the trauma of the last year— but will we do it?

Mabry, of NWEA, said while catching students up is important, society needs to view the recovery process as a multiyear effort. “In previous years, when looking at unfinished learning and finding ways to get students to accelerated growth, we never expected that we would get students who need support to meet those accelerated goals in one year. We would never approach it that way,” Mabry said. “Now, we’re so frantic. I think we’re frantic because we feel it’s this larger population.”

We would never approach it that way,” Mabry said. “Now, we’re so frantic. I think we’re frantic because we feel it’s this larger population.”

It’s a daunting task, but experts say there is hope.

“Kids will catch up eventually,” said Clearfield from Whitman College. But to get there, society may need to re-evaluate expectations, she added. “If most children in our community are behind by, like, a year or two, then our expectations for what is typical, it’s going to have to match where they are,” Clearfield said. “Otherwise, we are going to be constantly frustrated … we’re going to have expectations that don’t match their skills or abilities.”

By mid-autumn, Miller was heartened by what she was seeing in her classroom. Students were becoming more confident and independent. Their writing was stronger. There were fewer conflicts.

There were fewer conflicts.

One morning, Miller stood by her desk as students effortlessly transitioned from one activity to the next during center time. They quietly buzzed around, cleaning up activities and putting their notebooks away in cubbies as she prepared to work with a new group of students at her desk.

“It kind of gives me hope that we’ll be OK,” she said. “Even after last year, we’ll be OK.”

This story about reading skills was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

Reading for first graders - a selection of books for the 1st grade from the publishing house "Eksmo"

Primer (according to SanPiN)

Nadezhda Zhukova

This "Primer" was developed by the candidate of pedagogical sciences, Natalia Zhukova. This book is an example of a classic textbook that three generations of children have successfully learned from.

More details

418 ₽

418 ₽

Choose the most convenient offer:

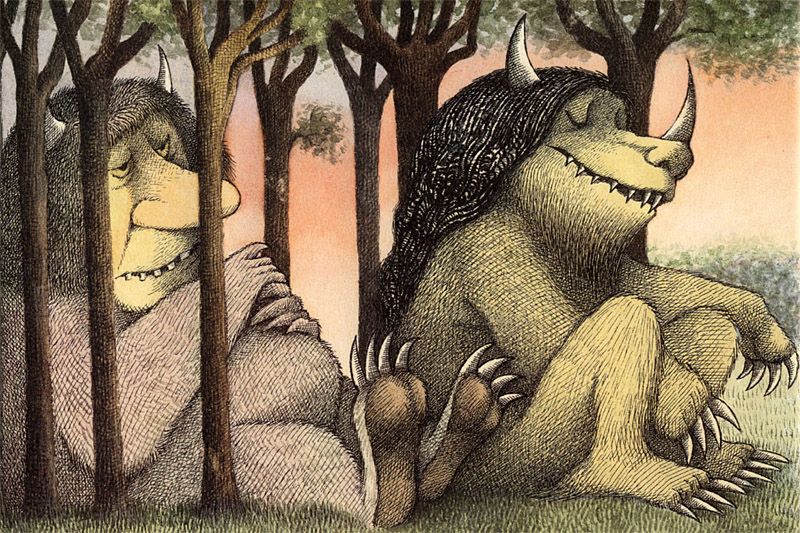

Electronic book Russian fairy tales (illustrated by I. Yegunov)

Large-format book for lovers of fairy tales - with wonderful drawings by Igor Yegunov, designed in the best traditions of domestic book illustration. Among the heroes of fairy tales are the Frog Princess, Koschey the Immortal, Morozko, the Tsar Maiden and many others.

more

636 ₽

775 ₽

-18%

Select the most convenient action:

Other editions

Elephant went to study

Samoilov Samoil0005

A funny and entertaining fairy tale by David Samoilov in verse, which you can read by roles and create your own children's play! This book is sure to lift your child's spirits.

Read more

Other editions

Poems for children

Agniya Barto

Texts in verse form allow the child to develop speech and memory at the same time. This book contains poems: “We are with Tamara”, “Amateur fisherman”, “Lyubochka” and 115 more best poems by Agnia Barto. nine0005

More

718 ₽

875 ₽

-18%

Choose the most convenient promotion:

Part 1. 2nd ed., corrected. and reworked.

Pyatak S.V.

This book is for children who already know letters. The proposed exercises contribute to the development of attention, memory, thinking, coherent speech and enrich the child's vocabulary.

Read more

225 ₽

289 ₽

-22%

Choose the most convenient promotion:

E-book I read easily and correctly: for children 6-7 years old

Pyankova E. A.,

A.,

This book will give your child the reading skills they need to succeed in elementary school. With the help of a special testing methodology, you will be able to correctly assess the reading skills of a child, choose the optimal development program for him and, in the process of learning, adjust it depending on what your child is interested in. nine0005

Read more

570 ₽

695 ₽

-18%

Select the most convenient action:

Other editions

Russian folk tales (Il. M. Litvinova)

Tales: "Tales:" "" "" "" "" "" " The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise", "The Frog Princess", "The Nesmeyana Princess" and others. Convenient small format and colorful design make this book easy to read.

More details

0004 241 ₽

-24%

Choose the most convenient promotion:

Other editions

I'm right. From the first lessons of oral speech to the "Primer"

Nadezhda Zhukova

All methodological literature according to the author's program of Nadezhda Zhukova is based on a combination of traditional and original speech therapy methods and is combined into a system. This edition will help your kid in mastering spoken language.

This edition will help your kid in mastering spoken language.

Read more

315 ₽

389 ₽

-19%

Choose the most convenient action:

Other editions

The first after the primer for reading

Nadezhda Zhukova

The missing link between the primer and the children's book will make up this reading manual. Its main task is to begin to form curiosity in children, to arouse in the child the desire to acquire new knowledge, develop an inquisitive mind and perseverance.

Read more

Mishkina porridge (illustrated by V. Kanivets)

Nikolai Nosov

This collection includes eight stories by the famous master of children's literature Nikolai Nosov about the adventures of two friends Kolya and Misha and about the unlucky Fedya Rybkin. Funny stories are accompanied by vivid illustrations by Vladimir Kanivets.

More

425 ₽

525 ₽

-19%

Choose the most convenient promotion:

Other publications Stage

001

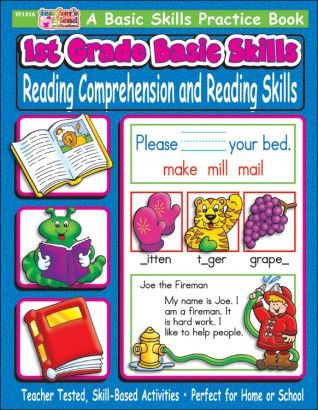

Primary school is a special stage in the life of any child, which is associated with the formation of the basics of his ability to learn, the ability to organize his activities. It is a full-fledged reading skill that provides the student with the opportunity to independently acquire new knowledge, and in the future creates the necessary basis for self-education in subsequent education in high school and after school.

It is a full-fledged reading skill that provides the student with the opportunity to independently acquire new knowledge, and in the future creates the necessary basis for self-education in subsequent education in high school and after school.

Interest in reading arises when a child is fluent in conscious reading, while he has developed educational and cognitive motives for reading. Reading activity is not something spontaneous that arises on its own. To master it, it is important to know the ways of reading, the methods of semantic text processing, as well as other skills. nine0005

Reading is a complex psychophysiological process in which visual, speech-auditory and speech-motor analyzers take part. A child who has not learned to read or does it poorly cannot comprehend the necessary knowledge and use it in practice. If the child can read, but at the same time he does not understand what he read, then this will also lead to great difficulties in further learning and, as a result, failure at school.

Reading begins with visual perception, discrimination and recognition of letters. This is the basis on the basis of which the letters are correlated with the corresponding sounds and the sound-producing image of the word is reproduced, i.e. his reading. In addition, through the correlation of the sound form of the word with its meaning, the understanding of what is read is carried out. nine0005

Stages of developing reading skills

T.G. Egorov identifies several stages in the formation of reading skills:

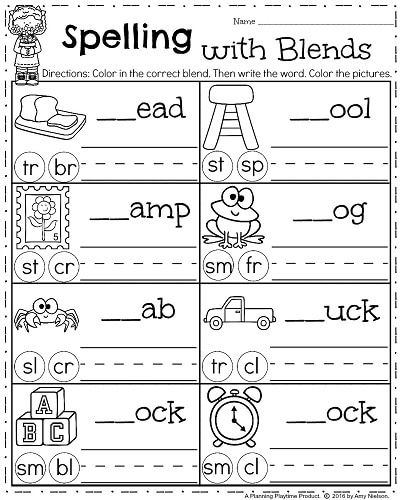

- Mastery of sound-letter designations.

- Reading by syllable.

- The formation of synthetic methods of reading.

- Synthetic reading.

The mastery of sound-letter designations occurs throughout the entire pre-letter and literal periods. At this stage, children analyze the speech flow, sentence, divide it into syllables and sounds. The child correlates the selected sound from speech with a certain graphic image (letter). nine0005

nine0005

Having mastered the letter, the child reads the syllables and words with it. When reading a syllable in the process of merging sounds, it is important to move from an isolated generalized sound to the sound that the sound acquires in the speech stream. In other words, the syllable must be pronounced as it sounds in oral speech.

At the stage of syllable-by-syllable reading, the recognition of letters and the merging of sounds into syllables occurs without any problems. Accordingly, the unit of reading is the syllable. The difficulty of synthesizing at this stage may still remain, especially in the process of reading long and difficult words. nine0005

The stage of formation of synthetic reading techniques is characterized by the fact that simple and familiar words are read holistically, but complex and unfamiliar words are read syllable by syllable. At this stage, frequent replacements of words, endings, i.e. guessing reading takes place. Such errors lead to a discrepancy between the content of the text and the read.

The stage of synthetic reading is characterized by the fact that the technical side of reading is no longer difficult for the reader (he practically does not make mistakes). Reading comprehension comes first. There is not only a synthesis of words in a sentence, but also a synthesis of phrases in a general context. But it is important to understand that understanding the meaning of what is read is possible only when the child knows the meaning of each word in the text, i.e. Reading comprehension directly depends on the development of the lexico-grammatical side of speech. nine0005

Features of the formation of reading skills

There are 4 main qualities of reading skill:

- Correct. By this is understood the process of reading, which occurs without errors that can distort the general meaning of the text.

- Fluency. This is reading speed, which is measured by the number of printed characters that are read in 1 minute.

- Consciousness. It implies understanding by the reader of what he reads, artistic means and images of the text. nine0188

- Expressiveness. It is the ability by means of oral speech to convey the main idea of the work and one's personal attitude to it.

Accordingly, the main task of teaching reading skills is to develop these skills in schoolchildren.

All education in the primary grades is based on reading lessons. If the student has mastered the skill of reading, speaking and writing, then other subjects will be given to him much easier. Difficulties during training arise, as a rule, due to the fact that the student could not independently obtain information from books and textbooks. nine0005

Methods and exercises for developing reading skills

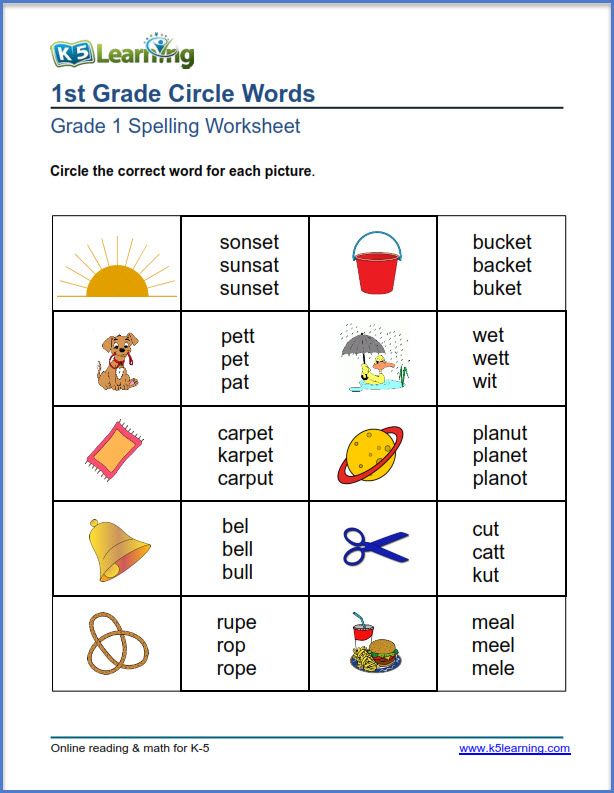

In educational practice, there are 2 fundamentally opposite methods of teaching reading - linguistic (the method of whole words) and phonological.

Linguistic method teaches the words that are most commonly used, as well as those that are read the same as they are written. This method is aimed at teaching children to recognize words as whole units, without breaking them into components. The child is simply shown and said the word. After about 100 words have been learned, the child is given a text in which these words are often found. In our country, this technique is known as the Glenn Doman method. nine0005

This method is aimed at teaching children to recognize words as whole units, without breaking them into components. The child is simply shown and said the word. After about 100 words have been learned, the child is given a text in which these words are often found. In our country, this technique is known as the Glenn Doman method. nine0005

The phonetic approach is based on the alphabetical principle. Its basis is phonetics, i.e. learning to pronounce letters and sounds. As knowledge is accumulated, the child gradually moves to syllables, and then to whole words.

Reading begins with visual perception, discrimination and recognition of letters. This is the basis on the basis of which the letters are correlated with the corresponding sounds and the sound-producing image of the word is reproduced, i.e. his reading. In addition, through the correlation of the sound form of the word with its meaning, the understanding of what is read is carried out. nine0005

In addition, there are several other methods:

- Zaitsev method .

It involves teaching children warehouses as units of language structure. A warehouse is a pair of a consonant and a vowel (either a consonant and a hard or soft sign, or one letter). Warehouses are written on different faces of the cube, which differ in size, color, etc.

It involves teaching children warehouses as units of language structure. A warehouse is a pair of a consonant and a vowel (either a consonant and a hard or soft sign, or one letter). Warehouses are written on different faces of the cube, which differ in size, color, etc. - Moore's method. Learning begins with sounds and letters. The whole process is carried out in a specially equipped room, where there is a typewriter that makes sounds and names of punctuation marks and numbers when a certain key is pressed. Next, the child is shown a combination of letters that he must type on a typewriter. nine0188

- Montessori method. It involves teaching children the letters of the alphabet, as well as the ability to recognize, write and pronounce them. After they learn how to combine sounds into words, they are encouraged to combine words into sentences. The didactic material consists of letters that are cut out of rough paper and pasted onto cardboard plates. The child repeats the sound after the adult, after which he traces the outline of the letter with his finger.

- Soboleva O.L. This method is based on the "bihemispheric" work of the brain. By learning letters, children learn them through recognizable images or characters, which makes it especially easy for children with speech disorders to learn and remember letters. nine0188

There is no universal methodology for developing reading skills. But in modern teaching methods, a general approach is recognized when learning begins with an understanding of sounds and letters, i.e. from phonetics.

There are certain exercises that help build reading skills. Here are a few of them:

- Reading lines backwards letter by letter. nine0184 The exercise contributes to the development of letter-by-letter analysis. The meaning is simple - the words are read in reverse order, i.e. from right to left.

- Reading through the word. You do not need to read all the words in a sentence, but jumping over one.

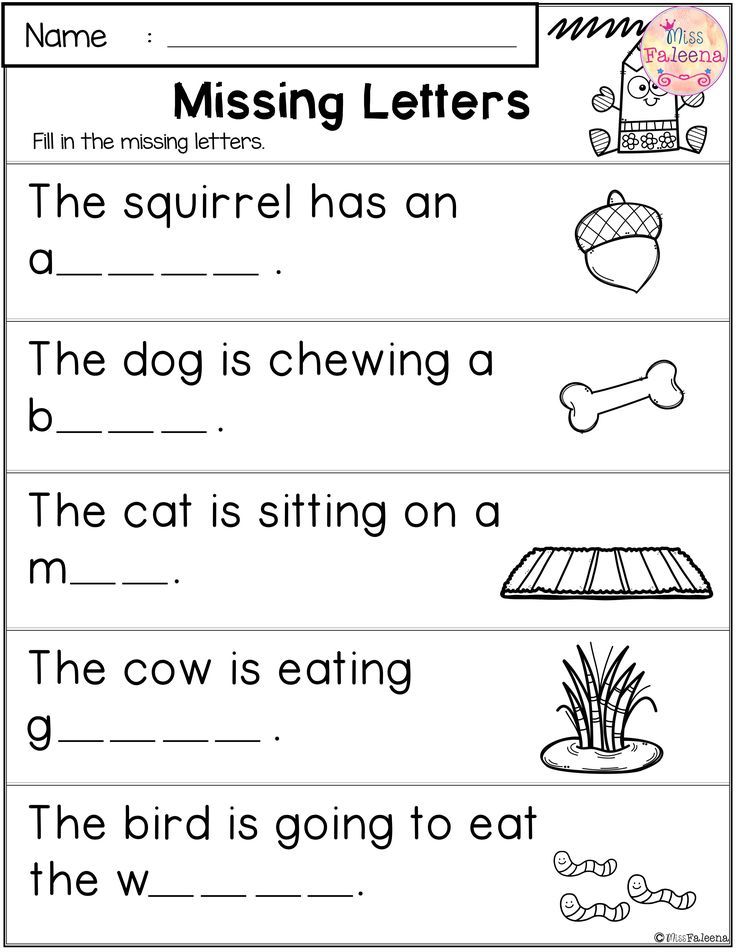

- Reading dotted words. The cards have words written on them, but some letters are missing (dotted lines are drawn instead).

- Read only the second half of the word. You need to read only the second part of the word, the first part is omitted. The exercise contributes to the understanding that the second part of the word is no less important than the first, thereby preventing the omission (or reading with distortion) of the endings of words in the future. nine0188

- Reading lines with the upper half covered. A piece of paper is superimposed over the text so that the top of the stitching is covered.

- Fast and multiple repetition. The child should repeat a line of a poem or a sentence aloud as quickly as possible and several times in a row. Correct pronunciation is extremely important, so if necessary, you need to stop and correct the child.

- Find the words in the text. nine0184 The child is faced with the task of finding the words in the text as quickly as possible.

Learn more