Reading to learn strategies

Strategies for Reading Comprehension :: Read Naturally, Inc.

Comprehension: The Goal of Reading

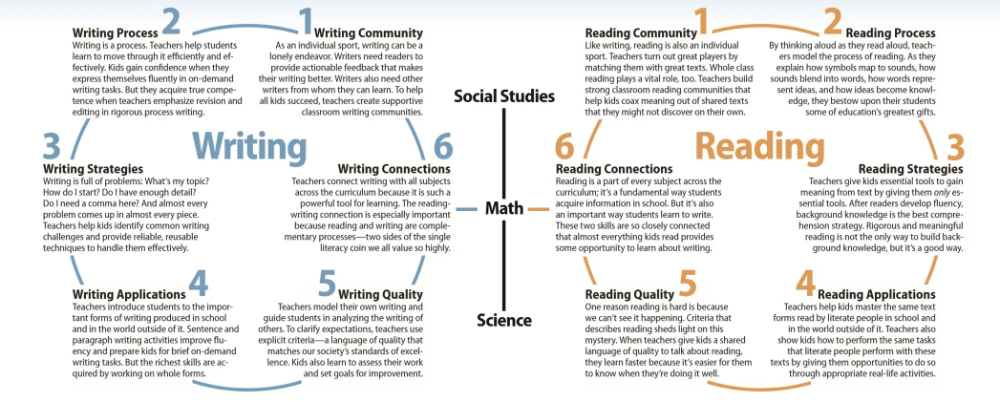

Comprehension, or extracting meaning from what you read, is the ultimate goal of reading. Experienced readers take this for granted and may not appreciate the reading comprehension skills required. The process of comprehension is both interactive and strategic. Rather than passively reading text, readers must analyze it, internalize it and make it their own.

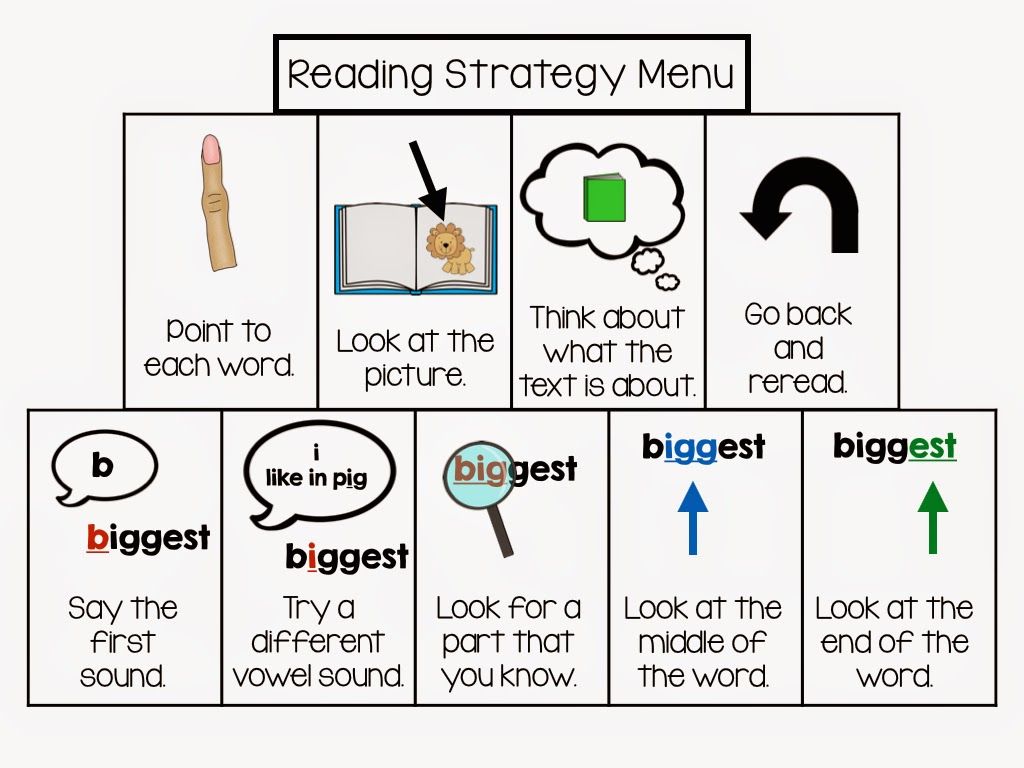

In order to read with comprehension, developing readers must be able to read with some proficiency and then receive explicit instruction in reading comprehension strategies (Tierney, 1982).

Strategies for reading comprehension in Read Naturally programs

General Strategies for Reading Comprehension

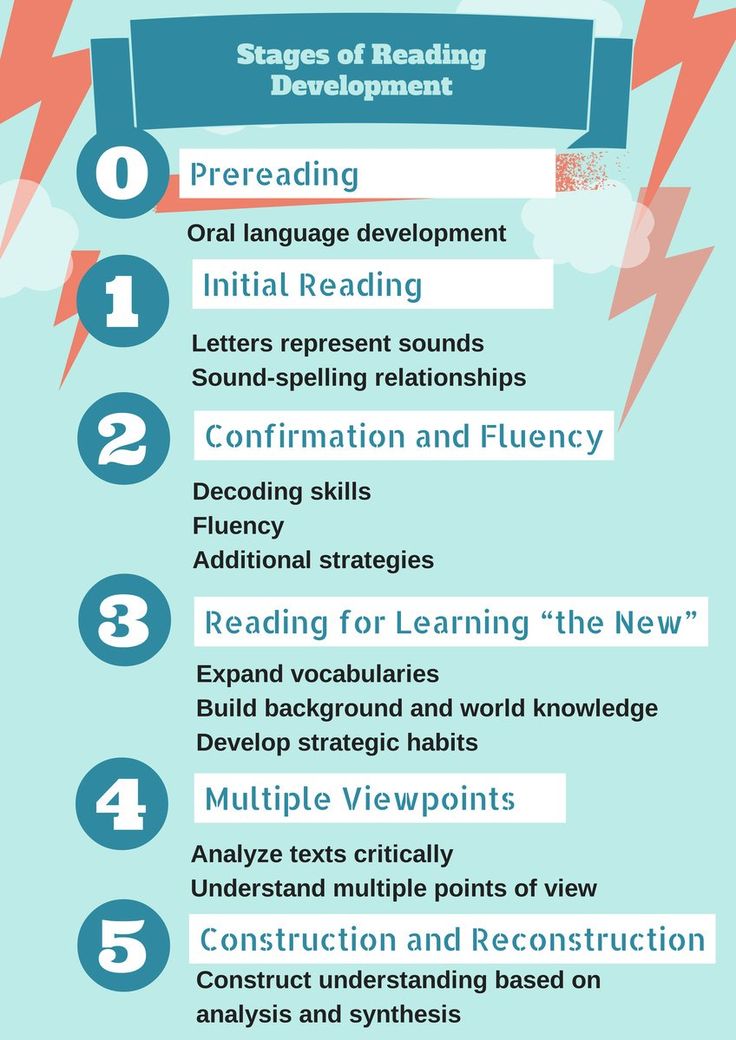

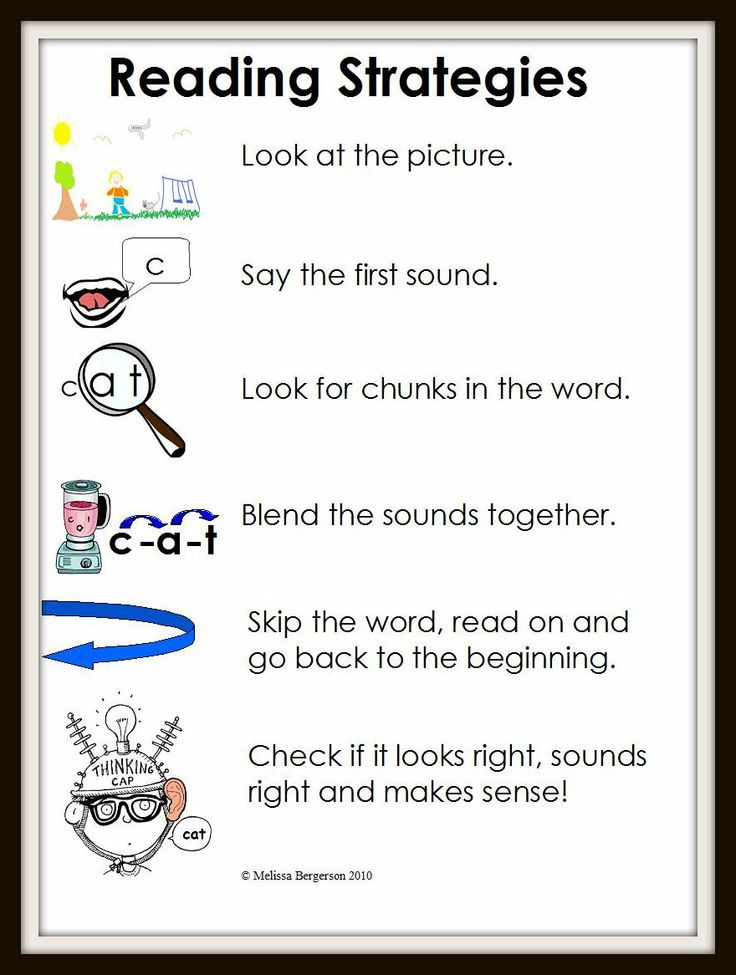

The process of comprehending text begins before children can read, when someone reads a picture book to them. They listen to the words, see the pictures in the book, and may start to associate the words on the page with the words they are hearing and the ideas they represent.

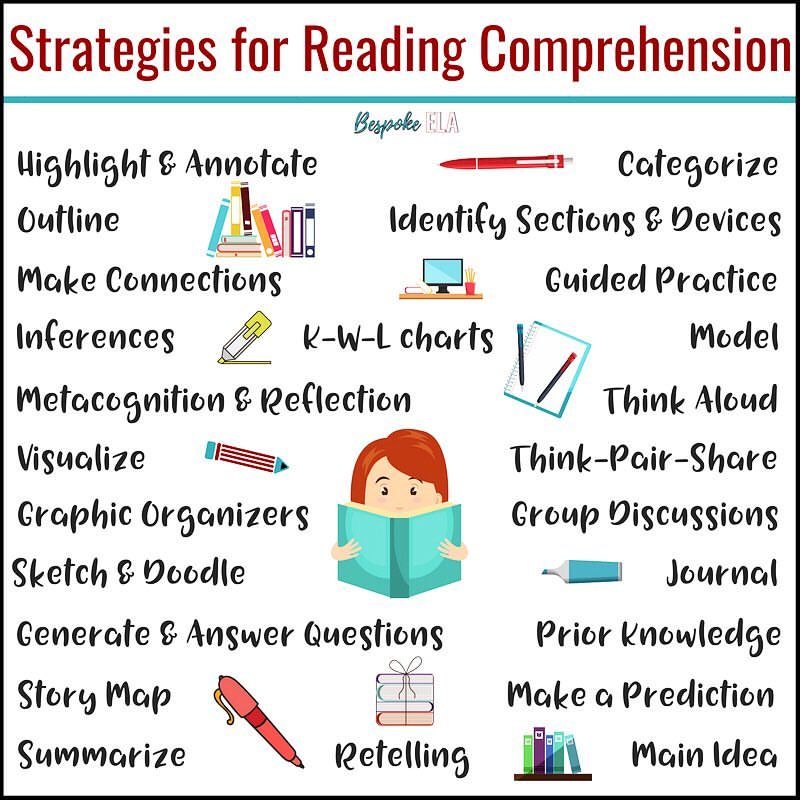

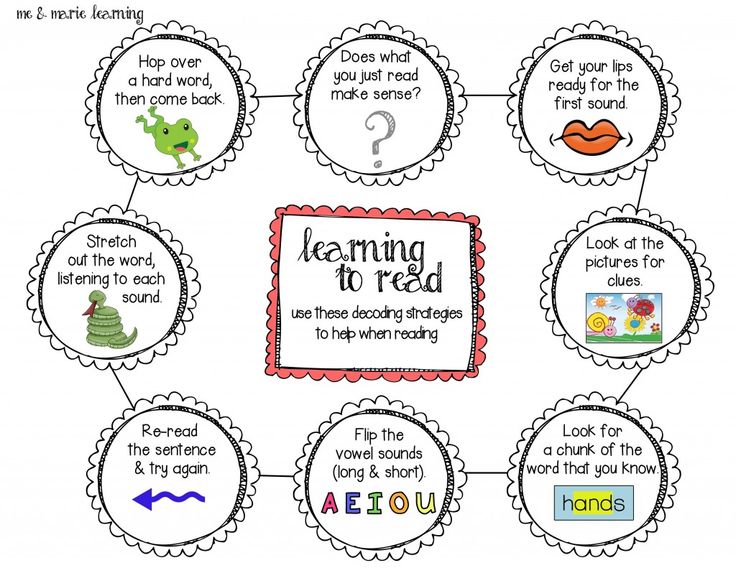

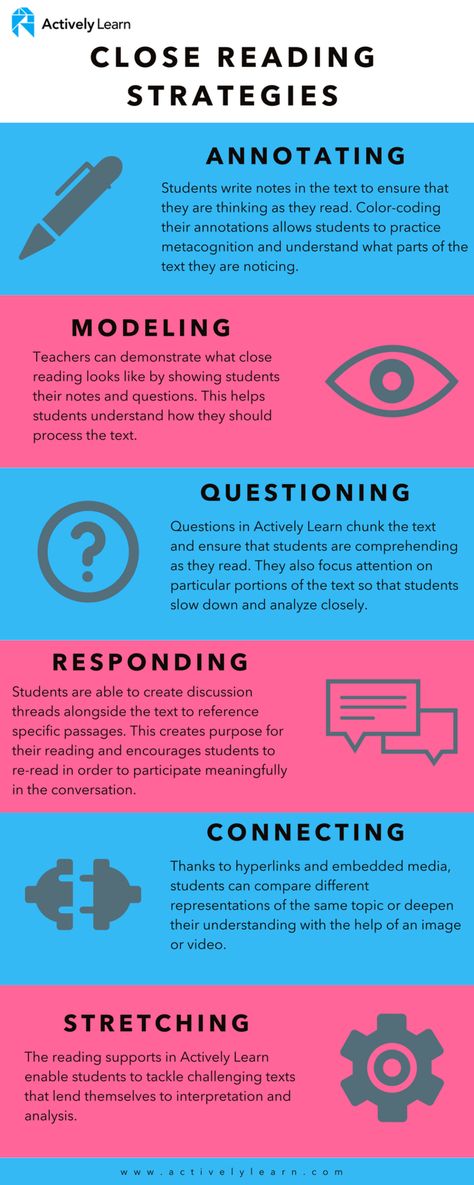

In order to learn comprehension strategies, students need modeling, practice, and feedback. The key comprehension strategies are described below.

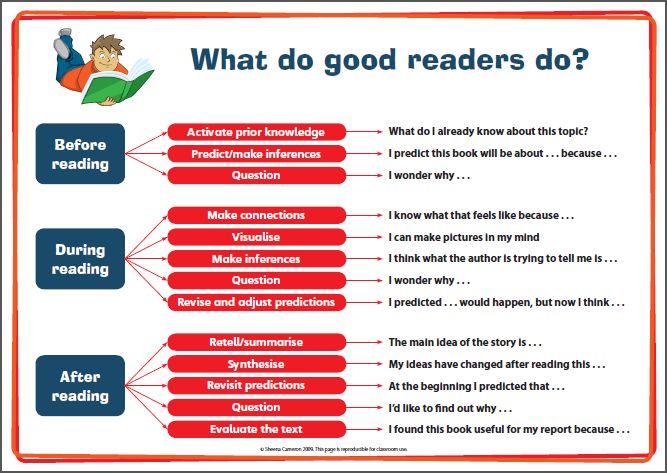

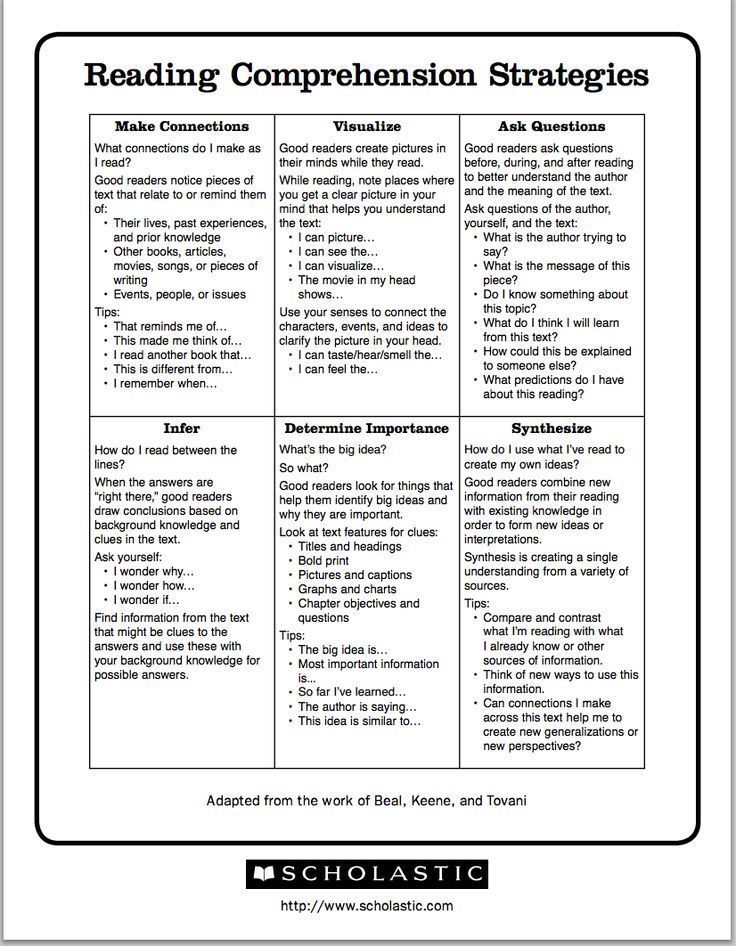

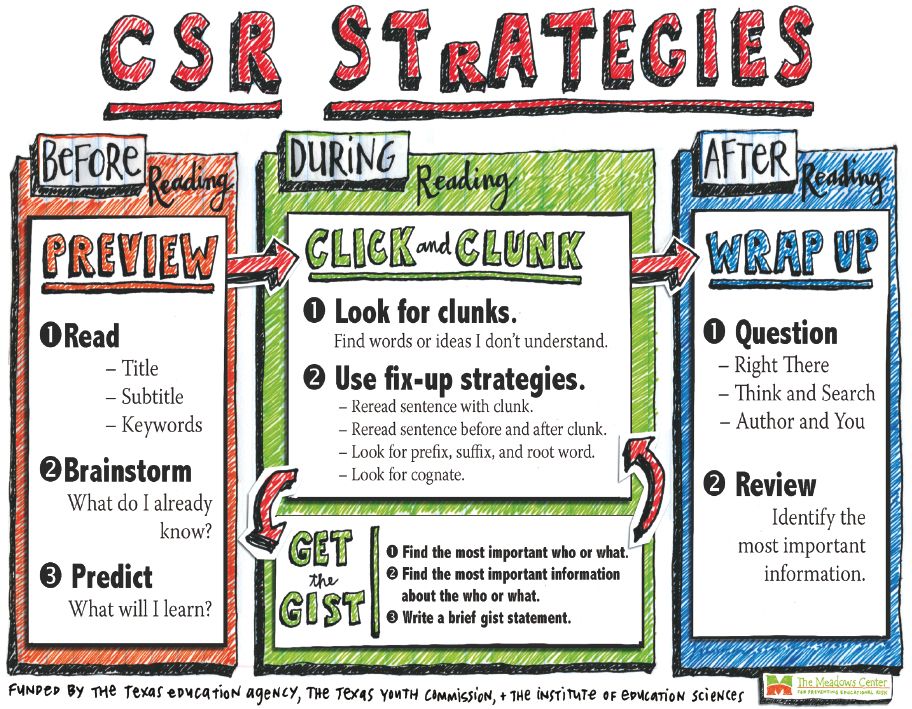

Using Prior Knowledge/Previewing

When students preview text, they tap into what they already know that will help them to understand the text they are about to read. This provides a framework for any new information they read.

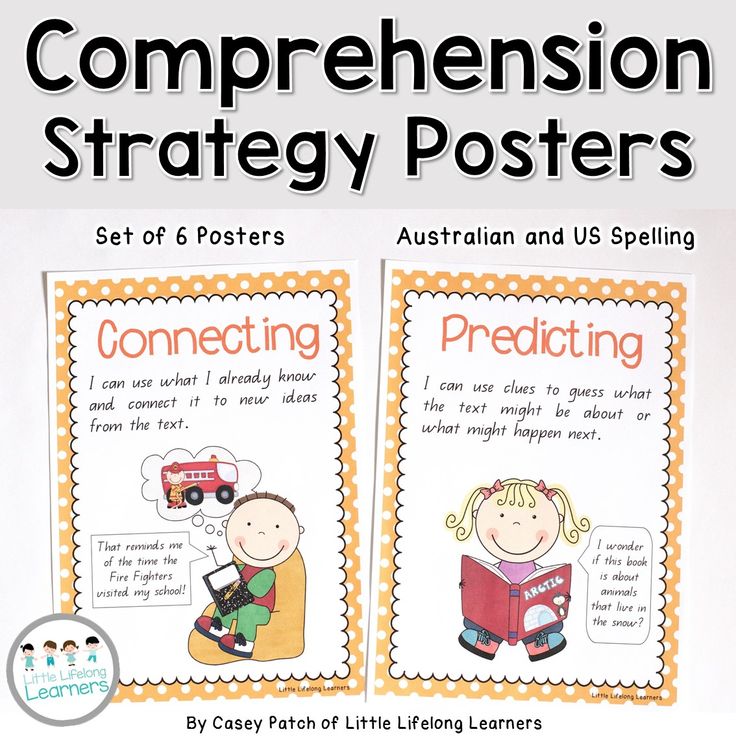

Predicting

When students make predictions about the text they are about to read, it sets up expectations based on their prior knowledge about similar topics. As they read, they may mentally revise their prediction as they gain more information.

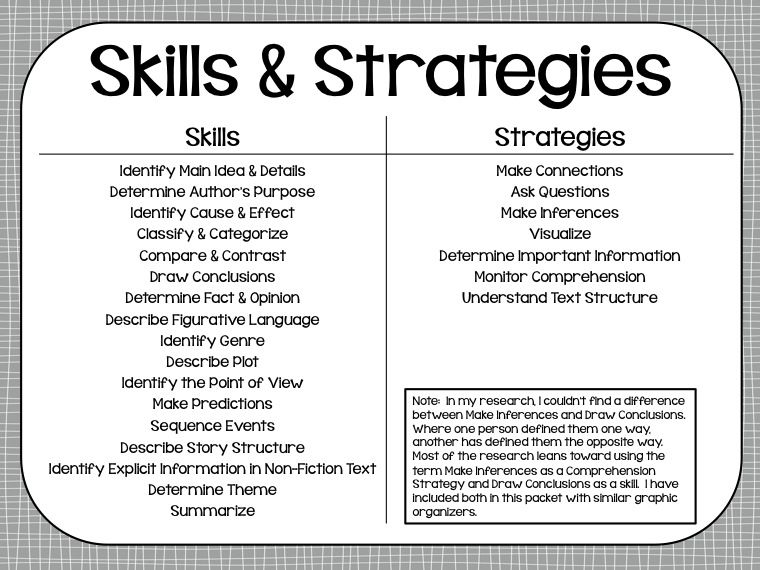

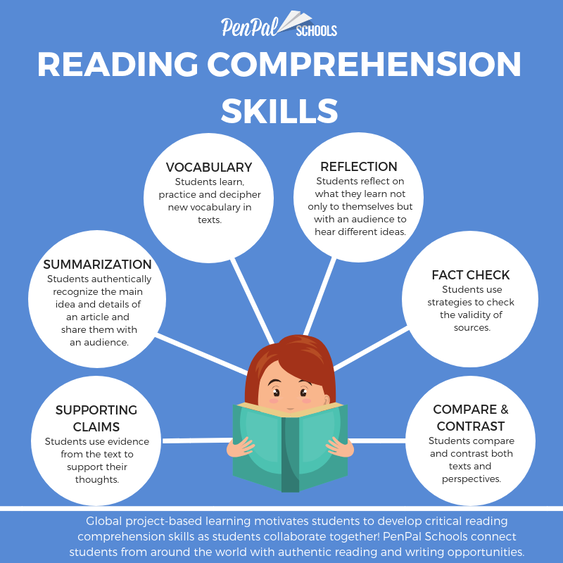

Identifying the Main Idea and Summarization

Identifying the main idea and summarizing requires that students determine what is important and then put it in their own words. Implicit in this process is trying to understand the author’s purpose in writing the text.

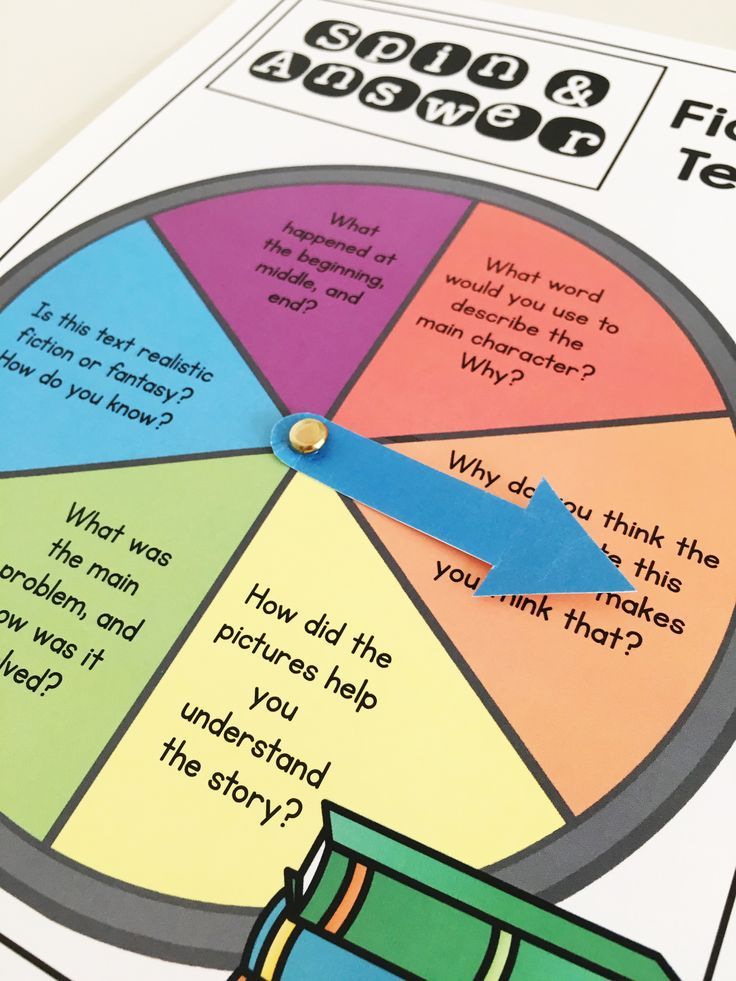

Questioning

Asking and answering questions about text is another strategy that helps students focus on the meaning of text. Teachers can help by modeling both the process of asking good questions and strategies for finding the answers in the text.

Teachers can help by modeling both the process of asking good questions and strategies for finding the answers in the text.

Making Inferences

In order to make inferences about something that is not explicitly stated in the text, students must learn to draw on prior knowledge and recognize clues in the text itself.

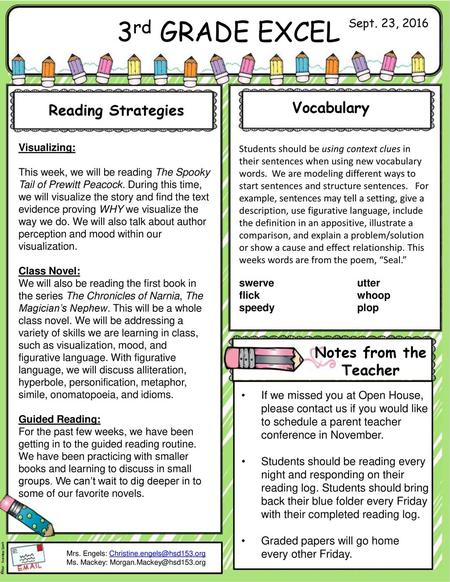

Visualizing

Studies have shown that students who visualize while reading have better recall than those who do not (Pressley, 1977). Readers can take advantage of illustrations that are embedded in the text or create their own mental images or drawings when reading text without illustrations.

Strategies for Reading Comprehension: Narrative Text

Narrative text tells a story, either a true story or a fictional story. There are a number of strategies that will help students understand narrative text.

Story Maps

Teachers can have students diagram the story grammar of the text to raise their awareness of the elements the author uses to construct the story. Story grammar includes:

Story grammar includes:

- Setting: When and where the story takes place (which can change over the course of the story).

- Characters: The people or animals in the story, including the protagonist (main character), whose motivations and actions drive the story.

- Plot: The story line, which typically includes one or more problems or conflicts that the protagonist must address and ultimately resolve.

- Theme: The overriding lesson or main idea that the author wants readers to glean from the story. It could be explicitly stated as in Aesop’s Fables or inferred by the reader (more common).

Printable story map (blank)

Retelling

Asking students to retell a story in their own words forces them to analyze the content to determine what is important. Teachers can encourage students to go beyond literally recounting the story to drawing their own conclusions about it.

Prediction

Teachers can ask readers to make a prediction about a story based on the title and any other clues that are available, such as illustrations. Teachers can later ask students to find text that supports or contradicts their predictions.

Teachers can later ask students to find text that supports or contradicts their predictions.

Answering Comprehension Questions

Asking students different types of questions requires that they find the answers in different ways, for example, by finding literal answers in the text itself or by drawing on prior knowledge and then inferring answers based on clues in the text.

Strategies for Reading Comprehension: Expository Text

Expository text explains facts and concepts in order to inform, persuade, or explain.

The Structure of Expository Text

Expository text is typically structured with visual cues such as headings and subheadings that provide clear cues as to the structure of the information. The first sentence in a paragraph is also typically a topic sentence that clearly states what the paragraph is about.

Expository text also often uses one of five common text structures as an organizing principle:

- Cause and effect

- Problem and solution

- Compare and contrast

- Description

- Time order (sequence of events, actions, or steps)

Teaching these structures can help students recognize relationships between ideas and the overall intent of the text.

Main Idea/Summarization

A summary briefly captures the main idea of the text and the key details that support the main idea. Students must understand the text in order to write a good summary that is more than a repetition of the text itself.

K-W-L

There are three steps in the K-W-L process (Ogle, 1986):

- What I Know: Before students read the text, ask them as a group to identify what they already know about the topic. Students write this list in the “K” column of their K-W-L forms.

- What I Want to Know: Ask students to write questions about what they want to learn from reading the text in the “W” column of their K-W-L forms. For example, students may wonder if some of the “facts” offered in the “K” column are true.

- What I Learned: As they read the text, students should look for answers to the questions listed in the “W” column and write their answers in the “L” column along with anything else they learn.

After all of the students have read the text, the teacher leads a discussion of the questions and answers.

Printable K-W-L chart (blank)

Graphic Organizers

Graphic organizers provide visual representations of the concepts in expository text. Representing ideas and relationships graphically can help students understand and remember them. Examples of graphic organizers are:

Tree diagrams that represent categories and hierarchies

Tables that compare and contrast data

Time-driven diagrams that represent the order of events

Flowcharts that represent the steps of a process

Teaching students how to develop and construct graphic organizers will require some modeling, guidance, and feedback. Teachers should demonstrate the process with examples first before students practice doing it on their own with teacher guidance and eventually work independently.

Strategies for Reading Comprehension in Read Naturally Programs

Several Read Naturally programs include strategies that support comprehension:

| Read Naturally Intervention Program | Strategies for Reading Comprehension | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction Step | Retelling Step | Quiz / Comprehension Questions | Graphic Organizers | |

| Read Naturally Live:

| ✔ | ✔ |

| |

| Read Naturally Encore:

| ✔ | ✔ |

| |

| Read Naturally GATE:

| ✔ | ✔ |

| |

| One Minute Reader Live:

|

| |||

| One Minute Reader Books/CDs:

|

| |||

| Take Aim at Vocabulary: A print-based program with audio CDs that teaches carefully selected target words and strategies for independently learning unknown words. Students work mostly independently or in teacher-led small groups of up to six students.

|

| ✔ | ||

Bibliography

Honig, B. , L. Diamond, and L. Gutlohn. (2013). Teaching reading sourcebook, 2nd ed. Novato, CA: Arena Press.

, L. Diamond, and L. Gutlohn. (2013). Teaching reading sourcebook, 2nd ed. Novato, CA: Arena Press.

Ogle, D. M. (1986). K-W-L: A teaching model that develops active reading of expository text. The Reading Teacher 38(6), pp. 564–570.

Pressley, M. (1977). Imagery and children’s learning: Putting the picture in developmental perspective. Review of Educational Research 47, pp. 586–622.

Tierney, R. J. (1982). Essential considerations for developing basic reading comprehension skills. School Psychology Review 11(3), pp. 299–305.

Strategies for the Classroom | Reading to Learn in Science

Reading to Learn in Science

These instructional strategies can be helpful to science teachers when the lesson requires some student engagement with text. Some are especially effective when used before reading, others during reading, and still others are used frequently after students complete a reading assignment.

Before Reading

Many studies suggest that reading comprehension can be improved by activating student’s prior knowledge of subject matter before they read. Teachers can ask students what they already know about a topic, priming them to build on that knowledge. However, this advice comes with a warning: prior misconceptions can lead to miscomprehension.

Consider the example of what causes seasons. The false belief that seasonal changes are caused by the earth’s varying orbital distance from the sun can make it hard for students to understand a text explaining how the earth’s tilted axis of rotation causes seasonal variations. On the other hand, students may be primed to understand the text if a teacher asks them what they know about how seasons differ in the northern and southern hemisphere, or what they know about how high the sun appears in the sky at different times of year, or what they know about the length of daylight in different seasons and different latitudes (e. g., where they live versus the North Pole).

g., where they live versus the North Pole).

The trick is to help students use what they already know, while being wary of what they mistakenly think they already know.

Anticipation Guide

Frayer Model

DARTS

Productive Talk Moves

Argument Lines

4 Corners

Picture Walk

During Reading

Reading comprehension can also benefit from specific strategies used during reading. The trick is to get students to read reflectively and monitor their own comprehension. Students may need help identifying points of difference between their preconceptions and the actual content of the text. They can benefit from close reading strategies (involving slowing down and re-reading difficult passages) and from adopting a critical perspective on the text, questioning the author’s intent. Anticipation guides can help: students can write down their initial expectations about a text, and then pause during reading to compare their predictions with what the text says.

Anticipation Guide

DARTS

Listening Triads

Reciprocal Teaching

Cornell Notes

After Reading

The process of understanding doesn’t stop when students reach the end of a text. Research shows that when students summarize and organize the salient content of a text after reading it, their comprehension and recall improves. It’s important for students to cite evidence from the text as they reason about claims.

There are a number of strategies students can use, individually or in groups.

Following up on a pre-reading strategy such as an anticipation guide can help students identify how their understanding has changed. The metacognitive act of reflecting on learning can itself enhance learning. Writing strategies such as doing a Frayer model about a main concept, filling out Cornell notes on the main ideas, or creating foldable graphic organizers allow students to demonstrate and consolidate their new understanding.

Having students talk about what they’ve read is another effective strategy. Students can engage in small group discussions, either around a writing prompt or through an activity such as learning triads. Or you can organize a whole class discussion or debate to check in on what students have learned. As students not only synthesize what they read but also respond to other students’ ideas, they will gain a deeper understanding of the material.

Anticipation Guide

Frayer Model

DARTS

Listening Triads

Productive Talk Moves

Cornell Notes

Argument Lines

Folding Graphic Organizers

4 Corners

Development of Reading to Learn in Science was led by Jonathan Osborne (Stanford University) through a SERP collaboration. Support for Reading to Learn in Science was provided by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education through grant number R305F100026. The information provided does not represent views of the funders.

The information provided does not represent views of the funders.

The emphasis of the RTLS project is on disciplinary literacy at the 4th to 8th grade level.

Meet the RTLS Team

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Strategic Education Research Partnership

SERP Institute

1100 Connecticut Ave NW

Suite 1310

Washington, DC 20036

SERP Studio

2744 East 11th Street

Unit E09.B

Oakland, CA 94601

(202) 223-8555

Registered 501(c)(3). EIN: 30-0231116

Subscribe to Newsletter

Privacy Policy

Terms of Service

Site Map

©

Copyright

Strategic Education Research Partnership

Five Strategies for Effective Reading *

Today, any curriculum involves studying a lot of literature, writing various projects, participating in various conferences and competitions. Without training in an educational institution, at the Olympics, when entering a university or college, there is nothing to do.

Without training in an educational institution, at the Olympics, when entering a university or college, there is nothing to do.

Not every person manages to quickly study the resource and remember the most important things. Therefore, Dishelp specialists decided to talk about the most popular reading techniques that will significantly increase the efficiency of preparation, taking into account the minimum time spent.

The role of reading in a person's life

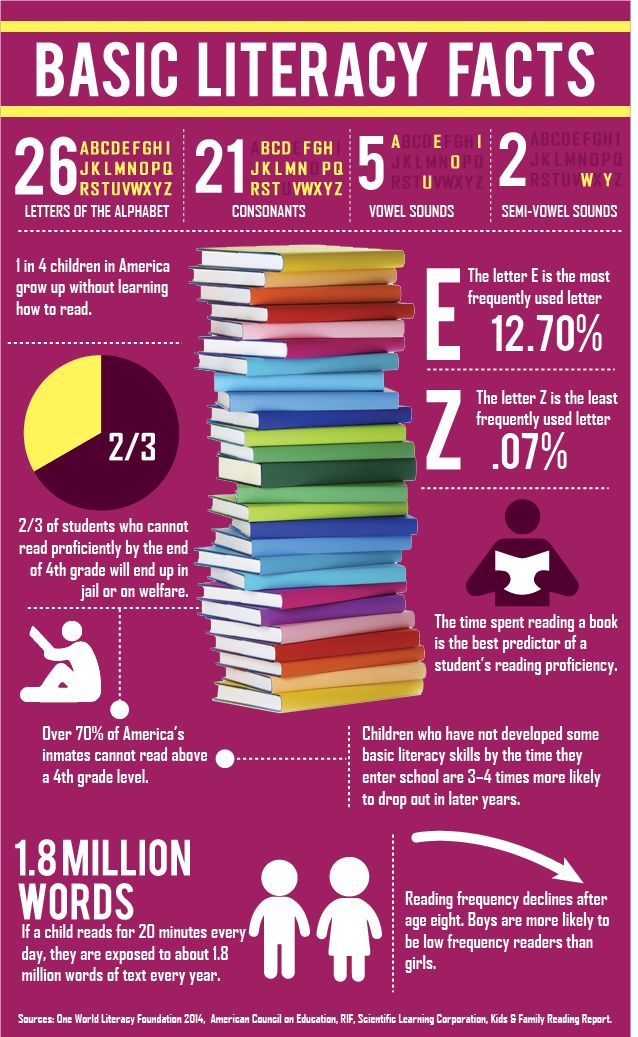

Reading is not just a skill that a person develops at the beginning of his life and uses it until the end of his days. Reading is an opportunity to develop, correspond to the time, be erudite and ready for any changes.

How does reading affect a person's life? Often the study of literature becomes a burden for students. It is difficult for them to assimilate what they read, to understand it (where is the truth and where is the lie), to remember important points. In 70% of cases, children do not like to read books, but without this skill it is impossible to live.

Reading brings certain benefits:

- Expands the outlook of the individual;

- Promotes growth in the profession;

- Helps in solving many problems;

- Instills certain cultural, ethical and other qualities;

- Etc.

No wonder they say: whoever reads a lot knows a lot.

Perhaps the only drawback of reading books is the loss of time (when studying literature, it flies by instantly), deterioration of vision (under uncomfortable conditions).

The Art of Efficient Reading

If you treat reading as an unloved thing, then the study of literature will turn into masochism: a person will read only under duress, not getting pleasure from it. This approach is inefficient.

If you perceive reading as a kind of art, you can reach unprecedented heights. This theory allows not only to select interesting literature, but also to easily develop oneself, to discover new horizons.

Rules for Effective ReadingExperts distinguish two positions regarding effective reading:

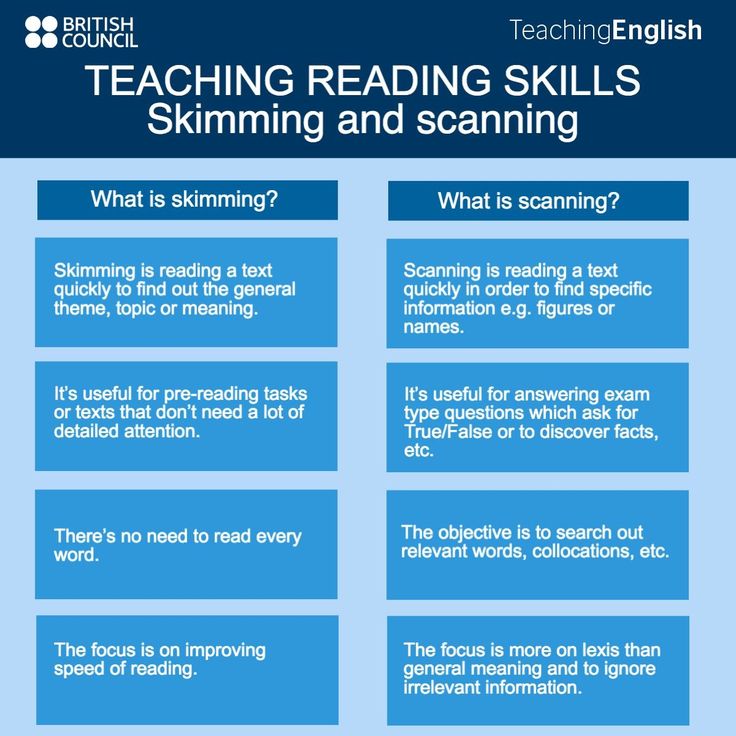

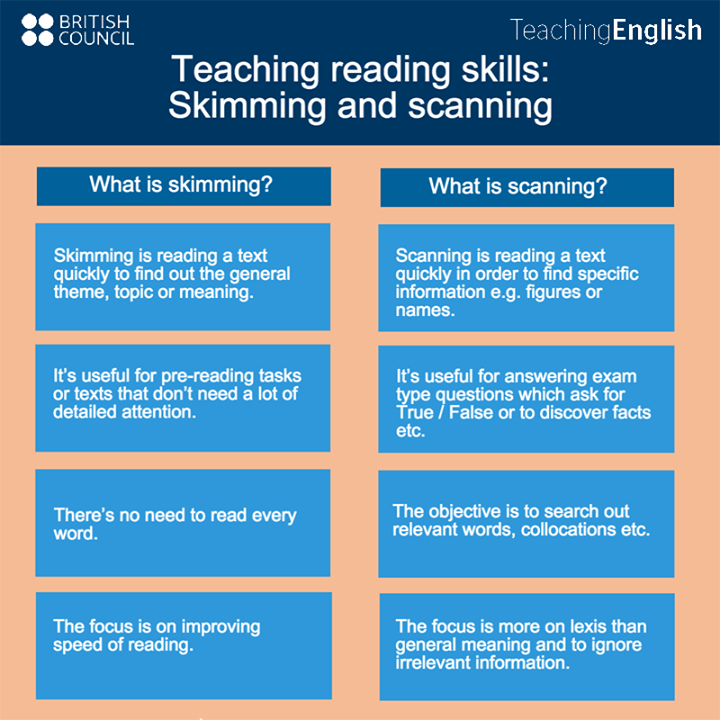

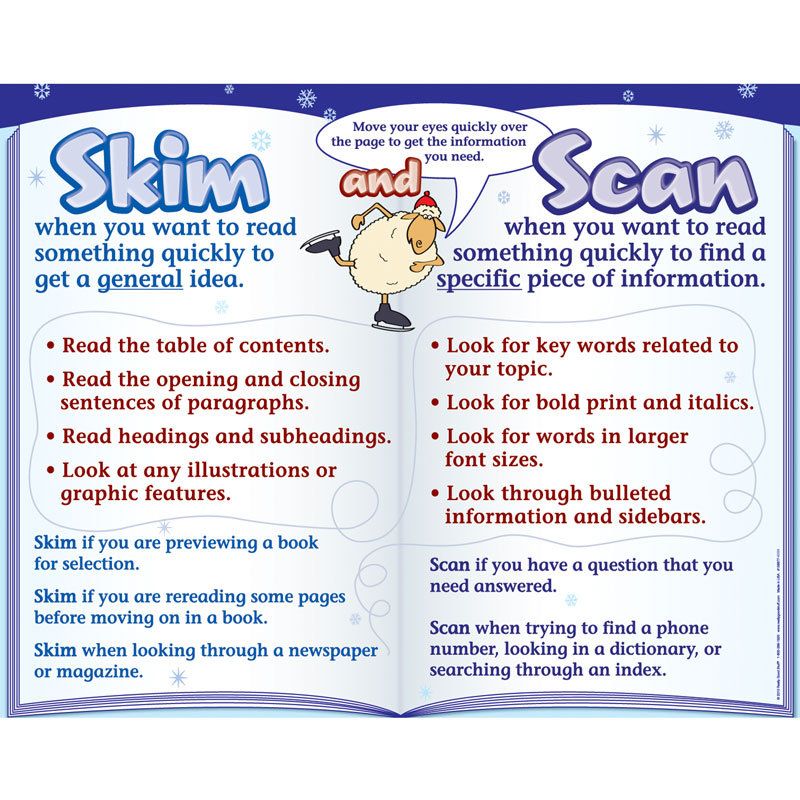

- Some believe that it is enough to skim through the text to highlight the essence;

- Others are convinced that one must read carefully, deeply.

This will allow you to understand the meaning of what is written, determine the position of the author, etc.

This will allow you to understand the meaning of what is written, determine the position of the author, etc.

In fact, the effectiveness of reading each appears in its own way. One is enough to read the material once to remember the most important points, to understand it. Others will have to hit the wall, re-reading the material several times in order to understand it. Each person is individual and perceives information in his own way. What comes easily to some may be incomprehensible to others. The main thing is not to reproach yourself for "stupidity / stupidity" and inaction. Patience and a little effort!

Effective Reading Strategies

DissHelp has compiled 5 of the most common and useful literature study methods used by most students and scholars in their research projects. According to the results of a sociological study, it is these methods that allow you to quickly study the material, understand and remember it.

Strategy #1. Pseudo reading.

Have you noticed that the more material to study, the less important points in it. Sometimes meaningful thoughts can be squeezed into a couple of paragraphs. Long texts often contain the author's judgments, background, examples, details that emphasize the importance of a particular concept or thought, etc. In such cases, deep reading takes a lot of time and effort, so it is enough to skim through the text.

Pseudo-reading involves reading paragraph by paragraph. Here it is important to understand the general meaning of what is written, to determine the structure (what and where is indicated) for orientation. With this reading, it is necessary to write out key words, dates, basic definitions, names, highlight the most important points.

Strategy #2. We read from the end.

At the end of each work, the author sums up everything written above. So why not save time and start learning the material from the end? After all, it is here that the key points and aspects are collected.

The only disadvantage of this strategy is that without special training and basic knowledge of the subject, it will be difficult to understand the conclusions.

Therefore, before using this technique, you need to familiarize yourself with the topic, have a minimal understanding of it, briefly look at the content of the text (understand the structure and train of thought of the researcher). It is also advisable to study the annotation foreword and the opinions of other experts.

Literature Study MethodsStrategy #3. Scanning.

Scanning is a cursory review of all material. In fact, this is the same pseudo-reading, but here it is important to initially highlight: the surnames and names of theories encountered, dates, names, definitions and terms, formulas, etc. If you write them out in the same sequence as they are indicated in the material, you can get a brief project plan.

When using this strategy, it is important to note the following points from the outset:

- What do you want to know: why are you studying the material?

- What will be useful to you: what terms, formulas and other points do you need for further development, use?

Scanning text allows you to process it in the shortest possible time, but not always the researcher manages to adequately understand all the nuances.

Strategy #4. We set a goal - we get a result.

This method assumes that even from the beginning of the study of the material, the researcher develops a certain plan:

- What should he learn?

- How much time is he willing to spend on that?

- What result will he get?

- After the first reading of the material, it is necessary to write down complex and incomprehensible terms, and then study them in more detail with the help of additional literature;

- After reading the paragraphs / subparagraphs / chapters or the entire text, you need to write out the main points: what the author is talking about, the evidence base, contradictions;

- Next, we determine how the studied information can be useful to the reader?

- Determine what you have learned and how you can use it.

This type of information processing makes it possible to understand what has been studied and how to use it in the future.

Strategy #5. We read and write.

It should be noted that this option only applies to drafts. It assumes that the author, as he reads the work (its parts), along the way highlights the main terms and definitions, key points and thoughts of the author. This is done directly in the text using multi-colored highlighters, etc. Agree that spoiling a book in this way is barbaric.

This option is often used by students when preparing for seminars and exams, when they find answers to the questions, print them out, and then study and highlight the most important.

Reading is an exciting and cognitive process that contributes to the development of personality and professionalism, culture and art, and spirituality. Make good use of your free time.

Reading strategies - Studopedia

Share

What do you think of rational reading? Apparently such when work with large volumes of information, with a large number of books is carried out with maximum productivity and with minimal effort and time. It is clear that work with books should begin with psychological preparation. By viewing the first book, you need to determine for yourself whether to read it or put it aside, whether it is advisable or not to work on it, and if appropriate, then in what class you need to read: either study the entire book in depth, or superficially review it, reading only separate parts , either find the necessary section in it and read this section selectively, or quickly find the necessary facts and thoughts in the book. In accordance with the task set for oneself, it is desirable to choose a specific reading strategy and work through the book in a planned way. Then move on to the second, to the third book, and so on. At the same time, it is desirable that reading strategies be worked out in advance.

It is clear that work with books should begin with psychological preparation. By viewing the first book, you need to determine for yourself whether to read it or put it aside, whether it is advisable or not to work on it, and if appropriate, then in what class you need to read: either study the entire book in depth, or superficially review it, reading only separate parts , either find the necessary section in it and read this section selectively, or quickly find the necessary facts and thoughts in the book. In accordance with the task set for oneself, it is desirable to choose a specific reading strategy and work through the book in a planned way. Then move on to the second, to the third book, and so on. At the same time, it is desirable that reading strategies be worked out in advance.

Studies by psychologists who are not supporters of learning speed reading types, but recognize the reality of the existence of readers with high reading speeds, have shown that one of the main foundations of speed reading skills is FORMED (note, not innate, but acquired as a result of practical training) READING HABITS FOR THE FOUR READING STRATEGIES:

1. The viewing strategy of reading.

The viewing strategy of reading.

2. Analytical strategy of reading.

3. Selective reading strategy.

4. Search strategy for reading.

Therefore, in order to learn how to read quickly, you need to FORM A STABLE MENTAL INSTALLATION to READ ALL TEXTS IN ONLY ONE OF THE FOUR STRATEGIES (and nothing else!).

| LETTER CHARTS | |||||||

| b P X in to | about t l With at | g a f d c | s Yu e n sh | w m sch s h | e R I th and | ||

| s d h I in | about f Yu th b | X uh sch and | g h m to R | w c sh a e | t P With l n | ||

| 9 | |||||||

| p h d and m | c l h R sh | x With Yu sch I | in G at and th | about a e s f | t to n uh b | ||

Focuses on fluency and phonics with additional support for vocabulary.

Focuses on fluency and phonics with additional support for vocabulary.

Guided by the belonging of the text to a particular class, you will remember the text reader corresponding to this class. Reading in the third grade can be attributed to the viewing strategy of reading.

Guided by the belonging of the text to a particular class, you will remember the text reader corresponding to this class. Reading in the third grade can be attributed to the viewing strategy of reading.  Readers with skim reading skills not only use their mental forecasting skills, but also know how to move their eyes through the text reasonably (rationally) in terms of time and effort.

Readers with skim reading skills not only use their mental forecasting skills, but also know how to move their eyes through the text reasonably (rationally) in terms of time and effort.

This strategy will help you find the information you need, for example, find out what new publications have appeared in your specialty.

This strategy will help you find the information you need, for example, find out what new publications have appeared in your specialty.  For search reading, a two-speed mode is used, similar to selective reading.

For search reading, a two-speed mode is used, similar to selective reading.  It is necessary to additionally develop an attitude (habit) to expand the field of perception when reading. This is an element of qualified reading. In order for the expansion of the field of perception during reading to become a habit, such a skill has been developed, always during search reading it is necessary not only to see paragraphs, semantic blocks, semantic integral units, but also to remember the need to expand the field of perception.

It is necessary to additionally develop an attitude (habit) to expand the field of perception when reading. This is an element of qualified reading. In order for the expansion of the field of perception during reading to become a habit, such a skill has been developed, always during search reading it is necessary not only to see paragraphs, semantic blocks, semantic integral units, but also to remember the need to expand the field of perception.