Sesame street where can you be b

Our Mission and History - Sesame Workshop

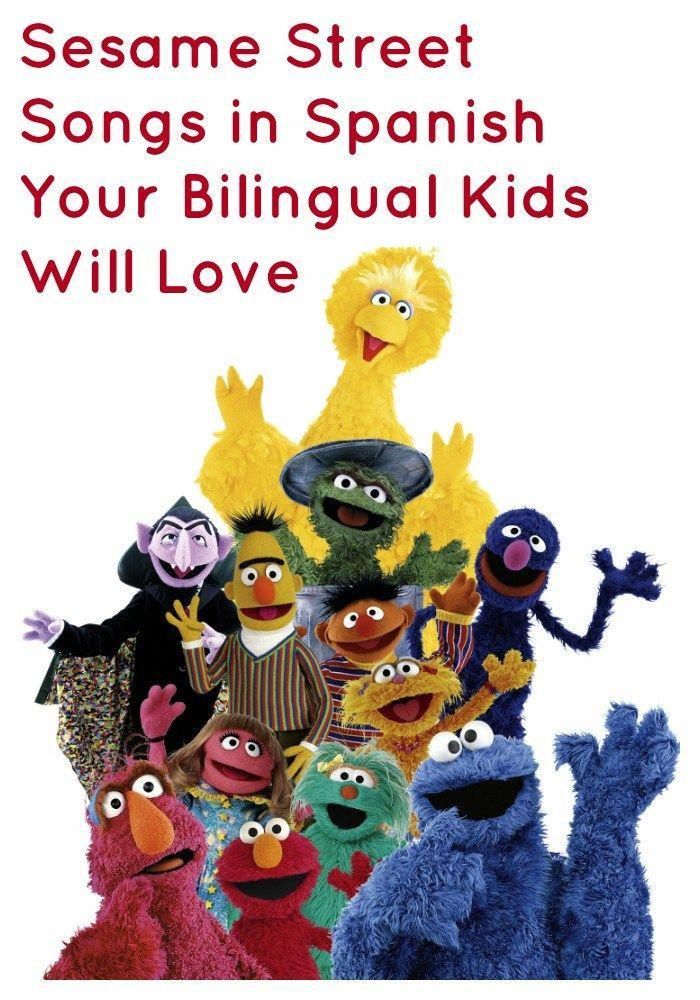

Our Mission and History - Sesame Workshop Skip to contentSesame Workshop is a nonprofit on a mission to help kids everywhere grow smarter, stronger, and kinder.

There are so many ways to help kids grow smarter, stronger, and kinder, and we’re doing everything we can to meet their needs in more than 150 countries. You’ll find us on screens, in classrooms, in communities — everywhere families can use a trusted hand to help little ones reach their full potential. Our unforgettable characters bring joyful learning into children’s lives — and help Sesame Workshop change the world, one smile at a time.

We have always focused on preschool-age children because research shows they have the greatest potential to learn…and because there’s no joy like the joy of a preschooler.

- 2020-Current

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

2020-Current

2020: Promoting Racial Justice

In the wake of nationwide protests over police brutality and historic racism, Sesame Workshop built on its long tradition of modeling diversity, equity, and inclusion and began a new focus on anti-racism and racial justice, informed by expert advisories, ongoing research, and the voices of children and caregivers. A CNN Town Hall, “Coming Together: Standing Up to Racism” was followed by a brand-new special, “The Power of We,” modeling ways children can stand up to racism. Rich offerings of short and long form programming, resources across multiple platforms, and Sesame Street in Communities content are planned for 2021, signaling the Workshop’s continuing commitment to tackle racism and its impact on children.

2020: Helping Children and Families Cope and Thrive in a Pandemic

When COVID-19 emerged, families everywhere suddenly faced unprecedented challenges. To help them regain a sense of normalcy, foster playful learning at home, and stay close to friends and family even from afar, Sesame Workshop quickly created Caring for Each Other, a global initiative featuring video playdates, international TV specials, free resources for parents, and kid-friendly Muppet messages reaching families in over 40 languages and more than 100 countries. Caring for Each Other is updated as needs evolve, continuing to offer comfort and support to children and caregivers alike.

2021: New Neighbors help out with the ABCs of Racial Literacy

Five-year-old Wes and his dad, Elijah, debuted along with the ABCs of Racial Literacy–free, bilingual resources to help families celebrate their identities while giving them tools to have open conversations with children about race and identity, engage allies to become upstanders against racism, and more. In one video, Elijah tells his new friend, Elmo, about melanin–and explains that the color of our skin is an important part of who we are.

2021: Elmo Adopts a Puppy

When Elmo and Grover encounter a sweet, music-loving stray puppy, they name her Tango and set off to find her “furever home.” Soon, everyone realizes Tango belongs with Elmo at 123 Sesame Street, Tango, who was in development for two years, helps children learn how to meet new animals, gently play with and care for pets, and more. After debuting in an animated special, Tango joined Sesame Street’s 52nd Season as both an animated character and a live-action Sesame Street Muppet.

2021: Ji-Young Moves to Sesame Street

See Us Coming Together: A Sesame Street Special” debuted on Thanksgiving Day and introduced the world to Ji-Young, a guitar-playing, skateboarding seven-year-old Korean American character performed by puppeteer Kathleen Kim. The special, celebrating the rich diversity of Asian and Pacific Islander (API) communities, is part of Coming Together, an initiative created to support families of all backgrounds through ongoing conversations about race.

2010-2019

2013: Supporting Children with Incarcerated Parents

2.7 million children in the United States have a parent in state or federal prison, but few resources exist to support young children and families coping with that reality. To help children with an incarcerated parent cope, we launched an initiative to equip adults and children with strategies and resources to help them feel comforted and connected through this difficult time.

2016: Meet Zari

In Afghanistan, Sesame co-production Baghch-e-Simsim stars our first Afghan Muppet, Zari — an energetic six-year old girl who loves to go to school and play sports. Zari promotes gender equity, serving as a role model for young girls and showing boys that it’s okay for girls to go to school, play cricket, and aspire to a career. Zari’s younger brother, Zeerak, joined the cast the following year. Zeerak looks up to his big sister, promoting the idea that women’s place in society extends beyond the home.

Zari promotes gender equity, serving as a role model for young girls and showing boys that it’s okay for girls to go to school, play cricket, and aspire to a career. Zari’s younger brother, Zeerak, joined the cast the following year. Zeerak looks up to his big sister, promoting the idea that women’s place in society extends beyond the home.

2017: Understanding Autism with Julia

An estimated one in 59 children in the United States is on the autism spectrum. While the diagnosis is common, public understanding of autism is not. Through the See Amazing in All Children initiative, we help support families of autistic children and reduce the isolating misconceptions that still surround autism with the help of Julia, the first Sesame Street Muppet with autism. Julia’s 2017 television debut was greeted with hundreds of media stories and millions of social media impressions, but the biggest marker of our success was the overwhelming response from the autism community and beyond.

2017: Restoring Hope to a Generation

Over 30 million children have been displaced in the global refugee crisis, losing homes and loved ones and enduring the kinds of trauma that puts them at risk for lifelong impairment. Children are remarkably resilient—we know that if we reach them early, we can help change their trajectories. But we also know we can’t do it alone—we need partners who understand the plight of refugees as well as we understand the needs of young children. So, with a historic support from the MacArthur Foundation, we teamed up with the International Rescue Committee to build the largest early childhood intervention in the history of humanitarian response.

Children are remarkably resilient—we know that if we reach them early, we can help change their trajectories. But we also know we can’t do it alone—we need partners who understand the plight of refugees as well as we understand the needs of young children. So, with a historic support from the MacArthur Foundation, we teamed up with the International Rescue Committee to build the largest early childhood intervention in the history of humanitarian response.

2018: Spreading the Power of Learning Through Play

Less than 3% of global humanitarian aid is dedicated to education, with only a small fraction benefitting young children. The LEGO Foundation, building on the bold philanthropy of the MacArthur foundation, granted Sesame Workshop $100 million to provide children affected by the Rohingya and Syrian crises with the chance to learn through play and develop the skills they need to thrive. Working in partnership with BRAC, the International Rescue Committee, and New York University’s Global TIES for Children, our play-based curriculum will foster engagement between children and their caregivers, nurture developmental needs, and build resilience, helping to set children on a path of healthy development.

2018: Growing and Innovating

In 2018, we partnered with Nelvana to create Esme & Roy, Sesame Workshop’s first new animated show in over ten years. The program follows a young girl and her best friend on their adventures as the best monster babysitters in Monsterdale. Aimed at children ages four to six, it offers a creative new approach to teaching “learning through play” and mindfulness strategies. Met with an enthusiastic critical response, Esme & Roy was part of a new wave of innovative content. Today, working for new platforms and with new partners, we have more shows in development than ever before.

2019: 50 Years of Helping Kids Everywhere Grow Smarter, Stronger, and Kinder

November 10, 2019 marked the 50th Anniversary of Sesame Street. A yearlong celebration honoring the longest-running children’s show in American history included a road trip across the U.S. with free events for families, a landmark Sesame Workshop study on personal identity, and a celebrity-filed primetime special on November 9.

2019: New York City’s Official Sesame Street

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio declared May 1, 2019 to be “Sesame Street Day” as he unveiled the city’s newest street sign and proclaimed that West 63rd Street between Central Park West and Broadway will now officially be known as Sesame Street. The event featured Sesame Street Muppets Big Bird, Cookie Monster, Elmo, and friends, plus Sesame Street cast members of yesterday and today and Council Member Helen Rosenthal, who sponsored the street naming resolution. Inspiring remarks were delivered by Mayor de Blasio, Sesame Workshop president and CEO Jeff Dunn, and Council Member Rosenthal, with a large crowd of onlookers joining a spirited sing-a-long of the Sesame Street theme song, “Sunny Days.”

2000-2009

2000: Breaking a Culture of Silence

In South Africa in the late 1990s, an estimated 1 in 4 children were affected by the HIV/AIDS crisis, either orphaned by the disease or infected themselves. Working with South Africa’s Department of Education, we developed the first-ever preschool curriculum to address HIV and AIDS, and created our groundbreaking HIV+ Muppet, Kami. Today, Kami and her friends still help reduce the stigma surrounding AIDS in the region.

Working with South Africa’s Department of Education, we developed the first-ever preschool curriculum to address HIV and AIDS, and created our groundbreaking HIV+ Muppet, Kami. Today, Kami and her friends still help reduce the stigma surrounding AIDS in the region.

2001: Coping with National Tragedy

In September 2001, Sesame Street was in the middle of production. Following the terror attacks on 9/11, we knew we had to address children’s emotional needs in the aftermath. We created a special series of Sesame Street episodes to give kids tools for coping with fear, loss, and culturally-motivated bullying—including one starring real New York City firefighters. In 2005, following the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, we aired a special episode about Big Bird dealing with the aftermath when his nest is destroyed in a storm. We also created a series of resources that families still turn to during natural disasters.

2006: Military Kids Serve, Too

In 2006, military deployments were at record levels, but existing resources often overlooked the youngest members of military families. Sesame Street reported for duty with a multimedia initiative that equipped families with child-friendly tools to tackle the unique challenges of military life. Topics include deployments and homecomings, grief and loss, military-to-civilian transitions, and how to stay healthy as a family.

Sesame Street reported for duty with a multimedia initiative that equipped families with child-friendly tools to tackle the unique challenges of military life. Topics include deployments and homecomings, grief and loss, military-to-civilian transitions, and how to stay healthy as a family.

1990-1999

1990: Celebrating Color

As part of a race-relations initiative, Whoopi Goldberg and Elmo compared and celebrated the colors and textures of their skin and fur in a now-classic segment. This tradition would continue through the years with “I Love My Hair,” “Lupita Nyong’o Loves Her Skin,” and other segments that promote empathy, cultural competence, and mutual respect and understanding.

1994: Bridging Painful Divides

In the mid-1990s, a Sesame Street co-production in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza introduced original characters who modeled cooperation and mutual respect to the youngest generation of Israelis and Palestinians, earning a letter of commendation from President Bill Clinton. Throughout the mid-2000s, Sesame Workshop produced other empathy-building co-productions in high-conflict areas, including Sesame Tree in Northern Ireland and Rruga Sesam and Ulica Sezam in Kosovo.

Throughout the mid-2000s, Sesame Workshop produced other empathy-building co-productions in high-conflict areas, including Sesame Tree in Northern Ireland and Rruga Sesam and Ulica Sezam in Kosovo.

1980-1989

1983: Farewell Mr. Hooper

Will Lee, who portrayed beloved shopkeeper, Mr. Hooper, passed away in 1983. The decision was made not to replace the actor, or have the character “move away.” Sesame Workshop’s curricular experts and script writers carefully planned how to tell young children about death. The program won an Emmy Award and struck an emotional chord with a generation of viewers.

1984: Elmo Loves You

Everyone’s favorite furry red monster was once an unnamed background character. Before long, Elmo’s signature voice and cheerful attitude began to emerge. In 1984, he made his first appearance as “Elmo.” He would go on to be a Sesame superstar —one of the most recognized children’s characters in the world!

1985: Snuffy, Revealed

For many years, the adults on Sesame Street thought that the shaggy, elephant-like creature called Mr. Snuffleupagus was Big Bird’s imaginary friend. But Snuffy wasn’t imaginary. Big Bird knew he was real, but his grown-up friends didn’t believe him. That changed in 1985. In the wake of a string of high-profile child abuse cases, we wanted to show children that the caring adults in their lives would believe them. By acknowledging that Big Bird was right about Snuffy all along, Sesame Street validated children’s feelings, encouraging them to share important things with their parents and caregivers.

Snuffleupagus was Big Bird’s imaginary friend. But Snuffy wasn’t imaginary. Big Bird knew he was real, but his grown-up friends didn’t believe him. That changed in 1985. In the wake of a string of high-profile child abuse cases, we wanted to show children that the caring adults in their lives would believe them. By acknowledging that Big Bird was right about Snuffy all along, Sesame Street validated children’s feelings, encouraging them to share important things with their parents and caregivers.

1970-1979

1971: Beyond Sesame Street

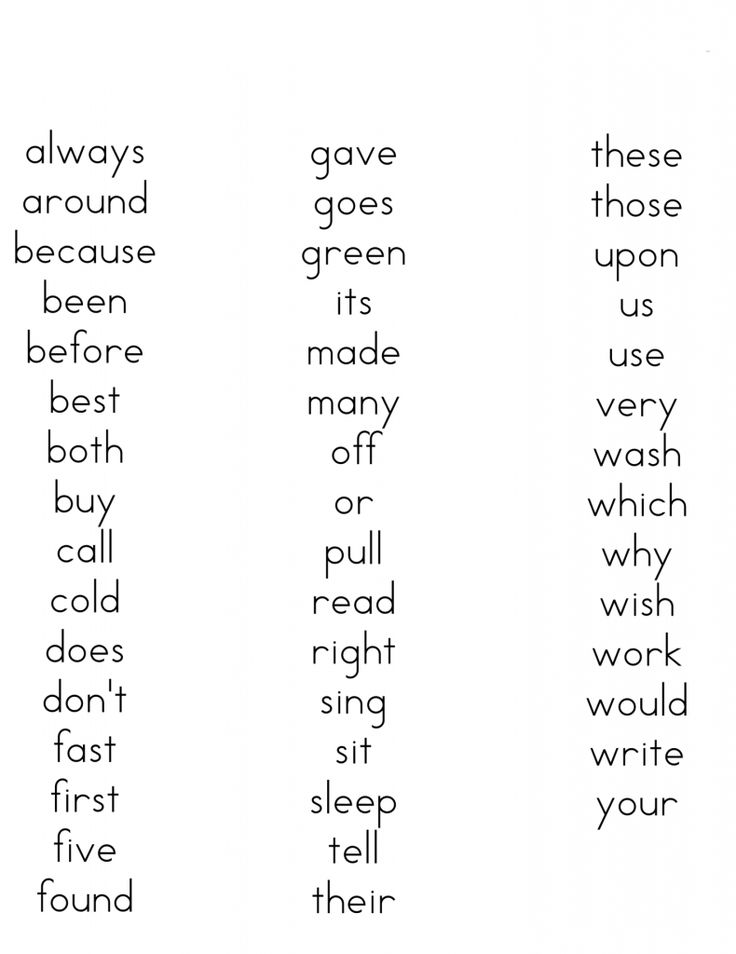

Once Sesame Street found its preschool audience, Sesame Workshop—then known as the Children’s Television Workshop—asked how we could serve other populations and meet other educational goals. In 1971, we launched The Electric Company to combat the literacy crisis facing children ages 7-10. Throughout the years, we created other classic animated and live-action shows like 3-2-1 Contact, DragonTales, and GhostWriter to meet kids’ changing needs.

1972: The Longest Street in the World

The success of Sesame Street in the United States sparked interest from broadcasters around the world. The first international co-productions—Vila Sésamo in Brazil and Plaza Sésamo in Mexico—premiered in 1972, followed by Germany’s Sesamstrasse in 1973. Through this process, we developed a model for creating co-productions that reflected the educational priorities and cultural sensibilities of individual countries—a model that’s still in use today.

1960-1969

1966: The Big Question

Against the backdrop of the Civil Rights movement and the War on Poverty, Sesame Street founders Joan Ganz Cooney and Lloyd Morrissett had a simple but revolutionary idea: television could help prepare disadvantaged children for school. They tapped educational advisors, researchers, television producers, artists, and other visionaries to create what would become the longest-running children’s show in American television history.

1969: Welcome to the Neighborhood

Sesame Street’s first episode opened with Gordon showing a new child around the neighborhood, telling her she’d “never seen a street like Sesame Street.” With celebrity guests, catchy songs and animations, and the beloved Muppets of Sesame Street, the show was an instant hit with children and parents alike. By the end of its first season, Sesame Street had reached millions of preschoolers.

Sesame Workshop

50 Years of Impact

Take an in-depth look at the remarkable history of Sesame Street and the non-profit behind it. This exclusive book can’t be bought — but you can view the entire resource right here

View 50 Years of Impact

Sesame Workshop received WSJ. Magazine’s Public Service Innovator Award

Sesame Street is the first TV show to win a Kennedy Center Honor

Sesame Street has won 193 Emmy Awards

Winner of the first-ever Macarthur 100&Change Award

Winner of five Peabody Awards including an Institutional Award

Named one of the “World’s Most Innovative Companies” by Fast Company

Recipient of a Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award 2017”

Awarded the IBC2018 International Honour for Excellence

Awarded the IBC2018 International Honour for Excellence

Help Prepare the Next Generation to Build a Better World

Make a gift today and help us transform how the world supports children, wherever they may be, for generations to come.

Donate Today

We’d Love to Keep You Posted on the Workshop

What's your email address?

Crypto Donations

Sesame Workshop accepts cryptocurrency donations through The Giving Block. Crypto donations are one of the most tax-efficient ways to give to Sesame Workshop. Your crypto contribution is tax-deductible to the fullest extent permitted by law if you pay taxes in the U.S. By making a charitable gift, you may also be eligible to significantly reduce what you would otherwise owe in capital gains taxes.

Matching Gifts

You can increase your impact by making use of your company’s matching gift program. In these instances, you will be recognized for the full amount of your gift plus any employer match.

To find out if your company has a matching gift policy, please enter your employer's name in the search box. Thank you for your support!

Matching Gift and Volunteer Grant information provided by

Donor-Advised Funds

Simply select your fund from the drop-down list above, type “Sesame Workshop” in the designation field, and enter the amount you’d like to give. Your gift will help us continue to meet children’s most pressing needs—whatever they may be.

Your gift will help us continue to meet children’s most pressing needs—whatever they may be.

Make a Sesame Workshop Donation

Make a gift today and help Sesame Workshop transform how the world supports children, wherever they may be, for generations to come.

Videos | Sesame Street | PBS KIDS

Videos | Sesame Street | PBS KIDSScroll Up

Scroll Down

See More

Watch Full Episodes

"That's Home" Song

Cookie Monster's Doggie Treats!

Hooray for Getting Clean!

Wheels on Grover's Bus

12 Amazing Vehicles

N is for Nature

Elmo & Rosita: Nature or Not Nature Game

Old MacDonald with Keke Palmer

Cookie Monster Foodie Truck: Spinach

Counting to 5

I Wonder, What if, Let's Try: Storybook

K is for kindness

H is for Holiday with Anderson .

Each Leaf is a Promise song

"Be Careful With the Words You Use" Song

F is for Friends with Amanda Gorman

B is for Books

Cookie Monster Foodie Truck: Succotash

Abby's Amazing Adventures: Rollercoaster

I Wonder, What if, Let's Try: Make a Pond

7 Beavers

W is for Weather

S is for Shapes

Cookie Monster Foodie Truck: Pancakes

We Can Grow Together song

G is for Garden

Elmo's World Alphabet

I Wonder, What If, Let's Try: Dentist

Cookie Monster Foodie Truck: Crunchy Snack

D is for Dance

Abby's Amazing Adventures: Choreographer

Abby's Amazing Adventures: Astronaut

Astro Team Alpha

Elmo and Tango's Mysterious Mysteries: Treasure

P is for Pretend

I Wonder, What If, Let's Try: Hiking Snacks

Naomi Osaka: Sunny Days

I Wonder, What If, Let's Try: Dog

I Wonder, What If, Let's Try: Coffee Can Shaker

I is for Instrument

A Monster and His Dog Song

I Want to Be a Service Dog Song

B is for Bugs

Elmo and Tango's Mysterious Mysteries: The Missing Cricket

Elmo's World: Colors

Kacey Musgraves Sings All The Colors

Cookie Monster Foodie Truck: Tofu

E is for Engineer

How Do You Build a Robot Dog Song

Elmo and Tango's Mysterious Mysteries: Wheel

5 Dogs, 5 Bones

Elmo's World: Kindness

Hey Friend with Josh Groban

Quiero Ser Tu Amigo

Anyone Can Be Friends

Sharing Song

Come and Play

Monster Foodies Truck: Milk

Come Together with John Legend

Try a Little Kindness with Tori Kelly

We Can All Be Friends

Word on the Street: Proud

Happy to Be Me

What I Am

Monster Foodie Truck: Prickly Pear Cactus

A is for Apple

Stop and Think

Sesame Street Alphabet Song

Town Alphabet

Count to 19

Elmo's Ducks

Pumpkin Face

10 Doggies

Make an Instrument, Join the Band

It's Halloween

Pretend

Let Santa Know We're Here

Valentine's Day Song

Thanksgiving Song with Leon Bridges

Jingle Bells

See More

Sesame Street : VIKENT.

RU

RU Sesame Street - children's television educational program.

The main idea of the Sesame Street TV project is to provide children from disadvantaged families with the opportunity to receive primary education. The word Sesame in the title is taken from an Arabic fairy tale where Ali Baba opens a cave with the words: Open Sesame!.

In the late 1960s, television producer Joan Cooney set out to start an epidemic. Her target was three-, four- and five-year-olds.

The causative agent of the infection was television, and the virus she wanted to spread was literacy. It was supposed to be broadcast for a whole hour five days a week. The hope was that if this hour proved contagious enough, it could be the tipping point for the start of an epidemic of universal literacy. The transfer was supposed to help children from poor families before they go to elementary school. […]

Educationists define television as a medium of low involvement. Television is like a wave of the common cold, which spreads through the population like lightning, but causes only a runny nose and disappears in a day.

Television is like a wave of the common cold, which spreads through the population like lightning, but causes only a runny nose and disappears in a day.

However, Cooney, Lesser, and their third partner, Lloyd Morrisett of the New York-based Markle Foundation, decided to give it a try. They invited some of the most famous creative people of the time. They borrowed the technique of TV commercials to teach children arithmetic and used vivid cartoon images to teach the alphabet. They invited celebrities who danced and sang, comedians for funny skits who told children about the benefits of working together or about their own perception. […]

The creators of Sesame Street achieved the incredible, and the story of how they did it is a great illustration of the second part of the tipping point, the stickiness factor.

They found that with a small but significant change in the presentation of the material, they could overcome the weakness of television as an educational tool and make the information memorable.

The Sesame Street project became successful because its creators figured out how to make television sticky.

In fact, the uniqueness of the program is the result of just the opposite process: the final product was developed purposefully and with great effort.

Sesame Street was built around one big idea: if you can keep children's attention, you can educate them.

This sounds like something obvious. But many television critics still argue that the danger of television is addictiveness and that children and even adults watch it like zombies. According to this view, it is the external properties of television that hold our attention (violence, bright colors, loud and unusual sounds, fast-paced shots, close and far shots, excessive activity, and everything else that we associate commercial TV with). In other words, we do not need to be aware of what is happening on the screen, or perceive what we see in order to look further. This is what many people mean when they say TV is passive. We look when we are stimulated by all this whistle and roar. And we turn away or change the channel if we're bored.

We look when we are stimulated by all this whistle and roar. And we turn away or change the channel if we're bored.

However, the early television researchers of the 1960s and 1970s, such as Daniel Anderson of the University of Massachusetts, began to realize that preschool children watch television in a very different way. Everyone thought that children would sit, look at the screen and disconnect from the outside world, says Elizabeth Lorch, a psychologist at Amherst College. - But when we began to carefully observe the behavior of children, we found that quick glances are a more common way of looking. Everything was not so simple. Children did not just sit and watch, they divided their attention between different activities, and this was not an accident. […]

Children, the researchers realized, are much more difficult than one might imagine in terms of viewing and remembering. We concluded, the researchers wrote, that the 5-year-olds in the toy group watched TV using a strategy of dividing their attention between the toys and watching TV in such a way as to see the most informative episodes of the program. This strategy proved to be so effective that the children could not take in more if they watched the program even with focused attention.

This strategy proved to be so effective that the children could not take in more if they watched the program even with focused attention.

Putting both of these studies together (experiment with toys and experiment with program editing), one can draw a rather radical conclusion about children and television. Children do not watch TV if they are specially stimulated, and turn away from the screens if they are bored. They look if they understand everything, and if not, they turn away. If you're in the educational TV business, you should take this into account. That is, if you want to understand whether children receive knowledge (and what) from the TV program, then you should understand what children pay attention to. And if you need to understand what knowledge children do not receive, then you need to find out what they do not pay attention to. […]

Head of the Sesame Street Research Group Ed Palmer was a psychologist at the University of Oregon in his younger years, specializing in the use of television as a teaching medium. When the Children's Television Study Group was formed in the late 1960s, Palmer naturally joined. I was the only kids TV scientist they could find,” he says, chuckling.

When the Children's Television Study Group was formed in the late 1960s, Palmer naturally joined. I was the only kids TV scientist they could find,” he says, chuckling.

Palmer was given the task of determining whether the intricate educational concept that scientific consultants had developed for Sesame Street was actually reaching viewers. It was a difficult task. Many members of the Sesame Street crew believe that without Ed Palmer, the TV show would not have lasted even one season.

Palmer's discovery was what he called the distraction technique. He played an episode of Sesame Street on a TV screen, and on a nearby screen he showed a slide show, showing a slide every seven and a half seconds .

We had the most incredible set of slides, says Palmer. - For example, a person running down the street with arms outstretched forward; image of a high-rise building; a leaf floating on a water ripple; rainbow; microscope image; Escher drawing. We strived for originality. Preschoolers were brought into the room two by two and offered to watch a TV show. Palmer and his assistants sat at a distance with pencils and paper, calmly recording when the children were watching Sesame Street and when they lost interest in it and switched to a slide show. Each time the slide changed, Palmer and his assistants made a new mark, so by the end of the show they had a nearly second-by-second report of which passages from the watched series kept the viewers' attention and which did not.

We strived for originality. Preschoolers were brought into the room two by two and offered to watch a TV show. Palmer and his assistants sat at a distance with pencils and paper, calmly recording when the children were watching Sesame Street and when they lost interest in it and switched to a slide show. Each time the slide changed, Palmer and his assistants made a new mark, so by the end of the show they had a nearly second-by-second report of which passages from the watched series kept the viewers' attention and which did not.

We took large sheets of graph paper, 60 by 90 centimeters, and glued several of them together, says Palmer. - The slides changed every seven and a half seconds, so there were almost four hundred slides per program. We've connected the transition points with a red line so that it looks like a stock market report. The line could drop sharply or gradually drop, and we asked ourselves: What is going on there? At another point, it could rise to the very top of the graph, and we would say: This piece definitely captures the attention of children. We tabulated the percentages of these distractions. Sometimes the result was 100%. The average attention score for most of the transmission duration was 85-90%. If the producers achieved such a result, they were very pleased. If it was around 50%, they sat down at their desk again.

We tabulated the percentages of these distractions. Sometimes the result was 100%. The average attention score for most of the transmission duration was 85-90%. If the producers achieved such a result, they were very pleased. If it was around 50%, they sat down at their desk again.

Palmer also researched other shows for children, such as Captain Kangaroo and Tom and Jerry. He compared the attention-grabbing snippets from them to the corresponding episodes from Sesame Street. Everything that Palmer learned, he reported to the show's producers and writers so that they could correct the material. One of the traditional myths about television is that children love to watch animals. The producers put a cat or an anteater or an otter into the program and made them jump in different directions,” says Palmer. - They thought it would be interesting. But the technique of distracting stimuli showed that every time it was not at all what was needed.

Much effort went into creating the Sesame Street character Alphabet Man, who specialized in puns. Palmer proved that the kids can't stand him. It was removed.

Palmer proved that the kids can't stand him. It was removed.

The application of the distraction technique showed that none of the fragments of the Sesame Street broadcast should exceed four minutes, and the optimal variant is three minutes.

Palmer forced the producers to simplify the dialogue and abandon some of the tricks taken from adult television. To our surprise, we found that the preschool audience didn't like it when the adults on the show got into long discussions,” he recalls. - They didn't like it when two or three people spoke at the same time. The producer instinctively tried to use the turmoil to cheer up the viewer. It seems to you that what is happening on the screen is full of energy. However, the children turned away from the screen. Instead of taking the signal that something exciting was happening, they were taking the signal that there was confusion. And they lost interest.

After the third or fourth season, I could already tell, Palmer continues, that our Attention Score rarely dropped below 85% . We hardly fixed the level at 50 or 60%, and if it happened, we made adjustments. Do you remember Darwin's theory that the fittest survive? We had a mechanism for determining the strongest, and we decided what was worthy of later life.

We hardly fixed the level at 50 or 60%, and if it happened, we made adjustments. Do you remember Darwin's theory that the fittest survive? We had a mechanism for determining the strongest, and we decided what was worthy of later life.

Malcolm Gladwell, Tipping Point: How Small Changes Lead to Big Change, Moscow, Alpina Publishers, 2010, p. 86-88.96-100.

Sesame Street. Part 1. What was supposed to be "Street ... | by Ksyusha s.

Joan Cooney (producer) and Gerald Lesser (psychologist from Harvard University) were the originators of the program. "Sesame Street" was conceived as an educational and developmental television program, aimed primarily at those segments of the population who did not have the opportunity to receive a quality education. Gradually, the show began to touch on very serious and complex topics, to explain to children that people are different, that some children do not have parents, and some children live with drug-addicted parents. The broadcast was also meant to be a strong channel of support for children and parents. Joan Cooney saw this project as an opportunity to influence the literacy and emotional intelligence of 3-5 year olds, as well as their parents. This age was not chosen by chance, as Joan wanted to develop an interest in learning in children and lay the foundations of emotional intelligence in them before they go to school. The creators considered involving parents in the viewing process the key point, and therefore various references to pop culture or modern events periodically appear in the show. The 1 hour, 5 days a week television format was able to reach large numbers of people at a low cost and have a strong impact.

The broadcast was also meant to be a strong channel of support for children and parents. Joan Cooney saw this project as an opportunity to influence the literacy and emotional intelligence of 3-5 year olds, as well as their parents. This age was not chosen by chance, as Joan wanted to develop an interest in learning in children and lay the foundations of emotional intelligence in them before they go to school. The creators considered involving parents in the viewing process the key point, and therefore various references to pop culture or modern events periodically appear in the show. The 1 hour, 5 days a week television format was able to reach large numbers of people at a low cost and have a strong impact.

Initially, Lesser did not share his colleague's optimism and believed that television was not capable of solving the problems of education, because the educational process should be individual. His main complaint was that television does not have the potential and ability to implement such an approach, in which it would be possible to discover the strengths of the child and develop them, as well as weaknesses in order to avoid their manifestation. He also believed that the TV is just a talking box that is not able to provide individual attention and influence on feelings that a child would respond to. In the sum of these factors, Lesser believed that television would be a medium of low involvement, compared, for example, with books. And the broadcast information will not have a strong effect. However, despite these doubts, the creation team decided to try to run the show.

He also believed that the TV is just a talking box that is not able to provide individual attention and influence on feelings that a child would respond to. In the sum of these factors, Lesser believed that television would be a medium of low involvement, compared, for example, with books. And the broadcast information will not have a strong effect. However, despite these doubts, the creation team decided to try to run the show.

Communication techniques borrowed from television advertisements (“In the 1960s, it seemed logical that if a 60-second commercial could sell a four-year-old child’s breakfast of oatmeal, it could sell alphabet knowledge to the same child.”) and also used bright images from cartoons. Sesame Street quickly achieved incredible success and marked a turning point in the history of television, allowing it to be truly educational. This was largely due to the “stickiness” factor. "Sesame Street" was built around one idea:

“If you can keep children's attention, you can teach them.

”

Before the launch of the show, a lot of research was done to study the mechanics of attention in children.

The early television researchers of the 1960s and 1970s, such as Daniel Anderson of the University of Massachusetts, began to realize that children were not watching television in the way they were supposed to.

“Everyone thought that children would sit, look at the screen and switch off from the outside world. But as we carefully observed children's behavior, we found that quick glances were a more common form of browsing. Children didn't just sit and watch, they divided their attention between different activities, and this was no accident. What made them look at the screen again wasn't trivial things like flashing and flashing."0005

, said Elizabeth Lorch, a psychologist at Amherst College. This made it possible to abandon the assumption that children are completely immersed in passive viewing, abstracting from the outside world.

And one day Lorch edited an episode of Sesame Street so that some key scenes were presented in a different order. If we consider this from the point of view of the passive viewing hypothesis, which holds attention only due to bright colors, loud sounds and fast changing pictures, then such editing should not have a serious impact on children's attention. After all, all the same key elements of the show, such as bright colors, puppets and songs, remained. However, the children stopped watching it. They did not understand what was happening, they got bored and turned away from the screen. In another experiment, Elizabeth Lorch and Dan Anderson showed two groups of five-year-olds an episode of Sesame Street. At the same time, children from the second group were placed in a room where there were also many toys. As the researchers predicted, children in the non-toy room watched the program about 87% of the time they were monitored, while children in the toy room watched about 47%. But when both groups of children were tested for understanding what they were watching, the results were absolutely identical. This was an amazing moment of exploration.

This was an amazing moment of exploration.

“We concluded that five-year-olds in the toy group watched TV using a strategy of dividing their attention between toys and watching TV in such a way as to see the most informative episodes of the program. This strategy was so effective that the children could not have taken in more if they had watched the program even with focused attention," the researchers wrote.

Sesame Street Goes Out

The turning point even before the official launch of the show was the sudden insight of Ed Palmer (a psychologist at the University of Oregon who specialized in television as an educational medium and was a scientific advisor on the project). He decided to test pilot releases in 60 families. Initially, all psychologists and scientific consultants agreed that in program in no case should you mix reality and fantasy . Therefore, in the 5 pilot episodes, the dolls existed in one space, and the street in another. And Palmer noticed an absolutely shocking thing, at moments with the street and the real world, the children lost all interest. It became clear to him that if the show was released in this format, it would be a complete failure.

And Palmer noticed an absolutely shocking thing, at moments with the street and the real world, the children lost all interest. It became clear to him that if the show was released in this format, it would be a complete failure.

Then the creators decided to ignore the recommendations and combine the world of reality and fantasy.

The program went on the air on November 10, 1969 years old. In the late 1960s, the Sesame Street Project created a children's television research group. For the first 3 seasons, they researched each episode, conducted many experiments and tested which of the hypotheses regarding children's attention and TV are working and which are not. The method of distracting stimuli became a find, it helped to understand at what point the children are ready to switch the focus of attention from the TV show to the adjacent screen with a slide show, and at what moments the cartoon held their attention no matter what. So a huge number of episodes were tested, which allowed us to create something like a checklist of a successful episode, which would allow us to keep the attention of children at least 85% of the screen time. An approximate checklist that I managed to collect from research and personnel analysis:

An approximate checklist that I managed to collect from research and personnel analysis:

- the optimal duration of the fragment is no more than 4 minutes. Better than 3 minutes. About 40 episodes in 1 program in total

- lack of turmoil

- absence of several adults and dialogue between them

- simplified dialogues

- absence of puns and speech constructions with multiple meanings

- central placement of key objects of attention

- one fragment - one idea28

The show's producer Joan Cooney has repeatedly said that “without research, there would be no Sesame Street.

In the 1970s, Sesame Street began to develop as a franchise. The first issue of the magazine of the same name has been published. It was designed for that part of the audience that was no longer relevant to learn the alphabet and numbers, but who still loved the characters of the program and wanted to learn something new with their help. But the magazine was not only for children 6+, there were also parents pages where parents told something about children.

But the magazine was not only for children 6+, there were also parents pages where parents told something about children.

Sesame Street also released 17 video games based on the program, where children had to complete tasks in a playful way: get ready for school, learn English, learn music and get acquainted with the sciences.

Since 1972, the TV show began to appear in other countries, and the first were Brazil and Mexico. At launch, it was clear that each country would have its own accents and unique themes. For example, in Brazil and Mexico, Plaza Sésamo emphasizes literacy, difference and gender equality. Also, each country had its own characters, for example, in Russia there were the following characteristic characters:

- Dinara / Aunt Dina

(She is about 30, she is a native of Tatarstan. Dinara married Yura, and together they adopted a child, a charming boy Kolya Aunt Dinara is very kind, she speaks several languages and introduces the residents of Sesame Street to the traditions and customs of different peoples) - Kolya

(He is 6 years old, he is the adopted son of Aunt Dinara and Uncle Yura. Kolya is a charming, kind boy. He is friends with all the puppet characters of Sesame Street)

Kolya is a charming, kind boy. He is friends with all the puppet characters of Sesame Street) - Sisters Yamila and Altyn

(Recently arrived in Russia from Kazakhstan Altyn learns to speak Russian and shares Businka's love for dancing)

Another interesting example is the appearance of Zarya doll with colored hair and wearing a hijab. She became a new character in the Afghan version of the children's television show Sesame Street. According to the creators, Zari should become a role model for girls and show that dreaming about a career and getting an education is normal, as well as help in the fight for the rights of women and girls. Sherry Westin, Sesame Workshop's executive vice president of global influence and philanthropy, said the new hero is a way for children of both genders to identify with a strong character. "It's a way to make sure we're not just teaching, but modeling, and very effectively," she said, adding that the study showed that images of confident, educated girls also helped shape boys' opinions on gender equality.

It also seemed to me a key moment when a new character appeared in the American show - Carly. It seems to me that this is one of the few characters who worked with the most difficult and taboo topic. The peculiarity of this character is that Carly's mother, according to the plot, was a drug addict. And even now, for me, a viewer in 2019, it seems like a revelation to speak on a children's TV show on such topics. However, if you look at the statistics, then the appearance of this character was a very important and necessary step.

According to BBC article in USA , 5.7 million children under 11 live with parents who are addicted to opioids. These children feel lonely in their situation, become more antisocial and are bullied. The latter also occurs when other children do not have sufficient understanding of what is happening and the ability to empathize. Due to the fact that such topics were raised in programs, it was possible to create a more comfortable environment in children's groups and give children from families who had previously ignored visibility and support.

Sesame Street still exists today. I think this could be considered an indicator that she is doing an excellent job with her mission as a project. But, in order not to be unfounded, I will devote another 3,000 characters to a review of research conducted by psychologists and scientific consultants in order to understand how the program manages to achieve its goals.

Over 1,000 studies have shown that Sesame Street helps preschoolers in many countries achieve better educational outcomes than children who don't watch the show. One of the most comprehensive I found to be Sesame Street Impact: A Meta-Analysis of Child Education in 15 Countries. It was conducted in 2013 and summarizes the results of 24 studies conducted with more than 10,000 children in 15 countries. The results showed significant positive program impacts, aggregated from learning outcomes in each of three categories: cognitive outcomes, including literacy and numeracy; knowledge about the world, including health and safety; social reasoning and attitudes towards outgroups. The effects were significant and were observed in both low- and middle-income countries and high-income countries.

The effects were significant and were observed in both low- and middle-income countries and high-income countries.

Thus, based on market research and international census (2013) estimates, Sesame Street's reach represents 16% of the global population. In this way, Sesame Street helps educate 156 million children in more than 150 countries around the world.

In order not to list an infinite number of positive statistics and not to produce entities, the results can be viewed briefly and with links here. I will just summarize everything: the program really helped a huge number of children. It was a real breakthrough in the field of talking with children about the structure of their bodies, society and the world. Originally conceived for the underprivileged, the TV show also gained attention among middle-class children. Children who watched the show before school performed better in both learning and communication than children who did not. Also, it will not be superfluous to note that, due to its mass nature, the show created a new cultural code in which generations developed. It powerfully dictated new values. Some of the scientific consultants of the project even used phrases such as “infected with the literacy virus”, “sowed the seeds of tolerance and empathy”.

It powerfully dictated new values. Some of the scientific consultants of the project even used phrases such as “infected with the literacy virus”, “sowed the seeds of tolerance and empathy”.

These shoots, it seems to me, can be seen in the current agenda.

In addition to the fact that the series continue to be released to the present, the project is also developing in reality. For example, there is a "sesame workshop" - a non-profit organization that arranges various events and trips to help children overcome various difficulties. Of particular interest is the range of issues they focus on. Among them there are both widespread and very non-obvious difficult situations: children from military families, children with HIV-positive status, refugee children or, for example, children who have experienced traumatic experiences.

Thus, the project still exists and continues its mission: in a playful way, it introduces children to a large, ambiguous, complex, but very interesting world.