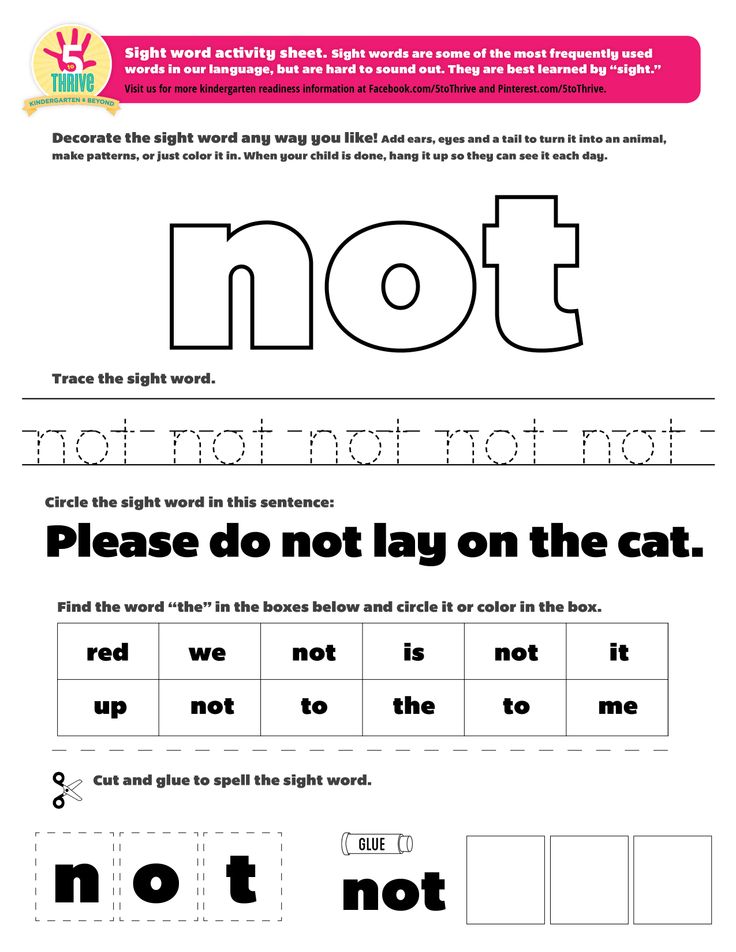

Sight word not

Sounding Out Words vs. Sight Words | Learning to Read by Decoding

Early readers must know how to tackle and instantly recognize two types of words to read fluently. One is decodable words; the other is non-decodable words. For kids with reading issues, including , learning to read both types of words can be a challenge.

This chart can help you know the difference between decodable words and non-decodable words, and what can help your child learn both.

| Decodable words | Non-decodable words | |

|---|---|---|

| What they are | Words that kids can sound out using the rules of phonics. Examples include: pot, flute , and snail. | Words that can’t be sounded out and that don’t follow the rules of phonics. They need to be memorized so they’re instantly recognizable. Examples include: right, enough, and sign. (Note: Some decodable words are also taught as sight words. These words are used so frequently that kids need to recognize them instantly.) |

| Skills required | Kids need to have phonemic awareness (part of a broader skill called phonological awareness). This skill allows students to rapidly map sounds to letters and blend sounds to read words. Kids also rely on working memory to help them keep in mind the sounds at the beginning of a word as they decode the rest of the word. | Kids need good memory skills to store words in their long-term phonological memory. That allows them to quickly retrieve words when they see them. Kids need fast-enough processing speed to read words automatically and fluently. |

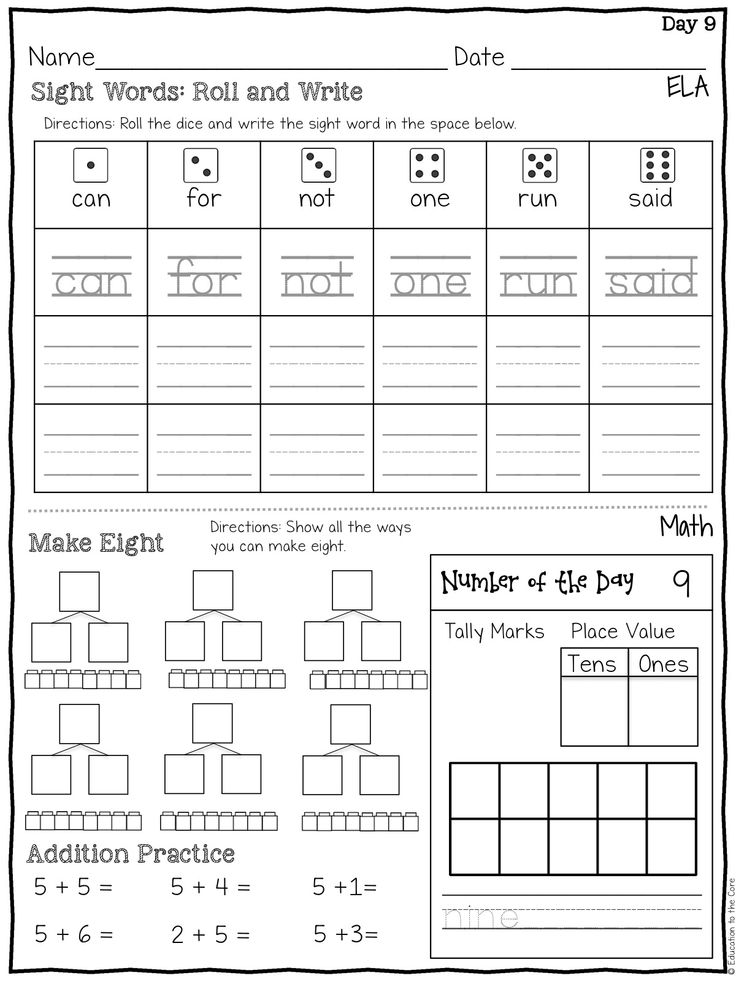

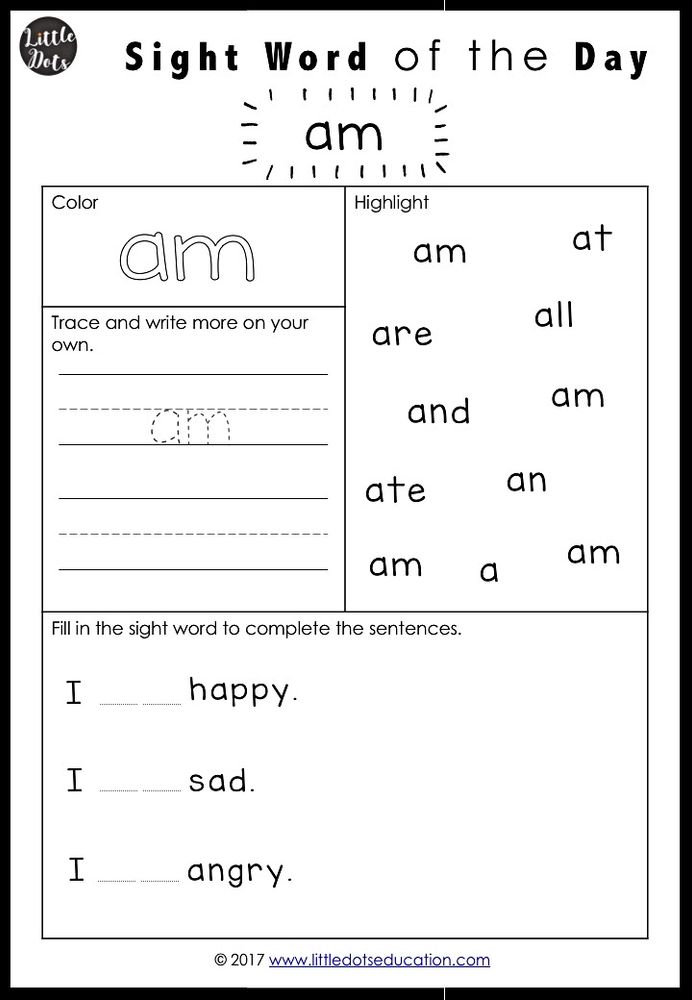

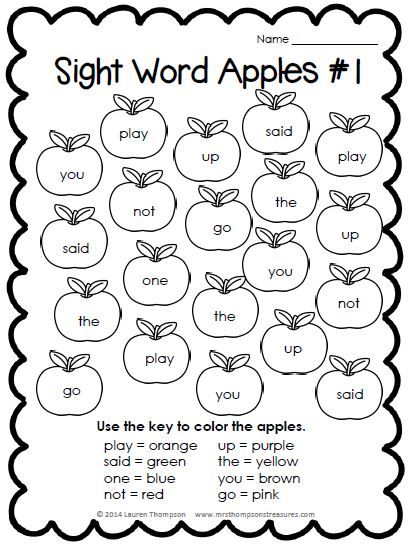

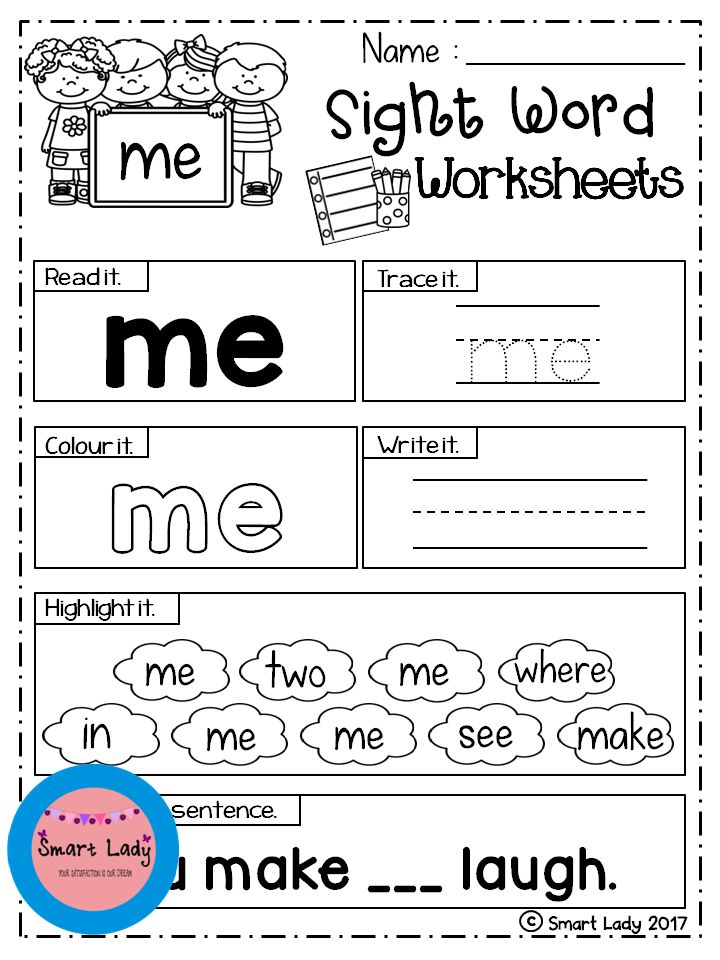

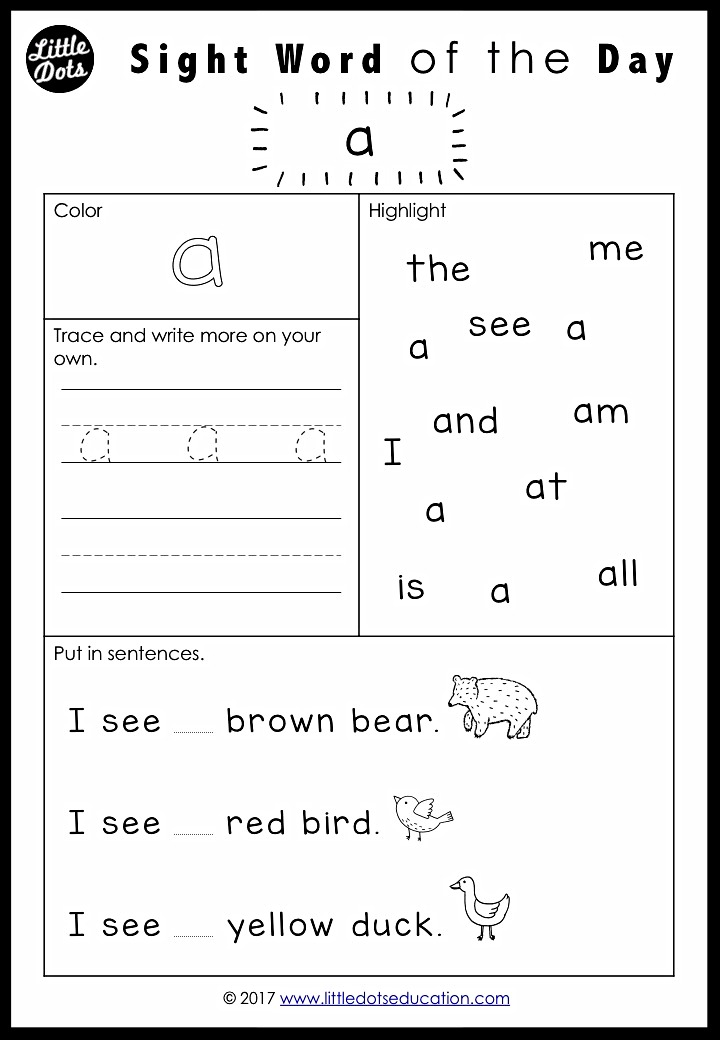

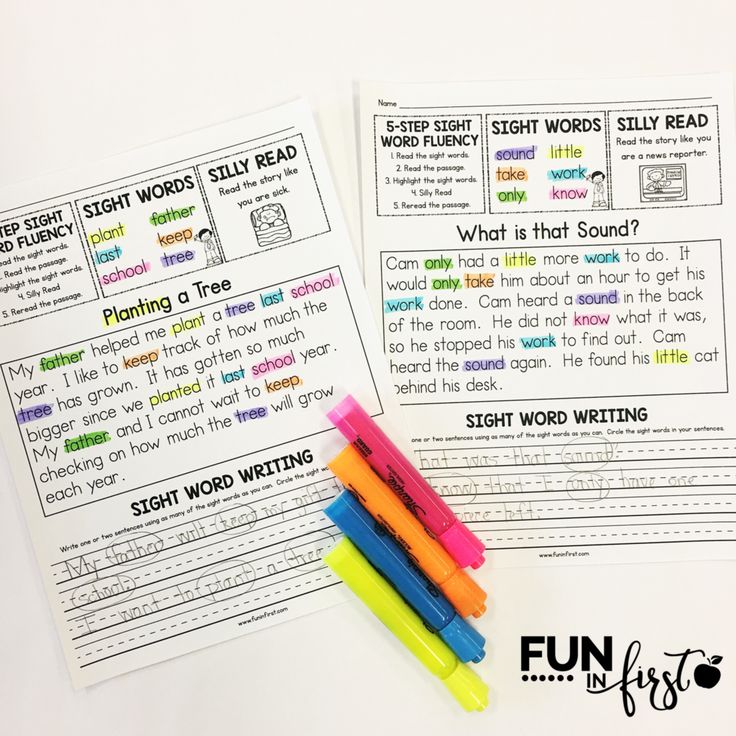

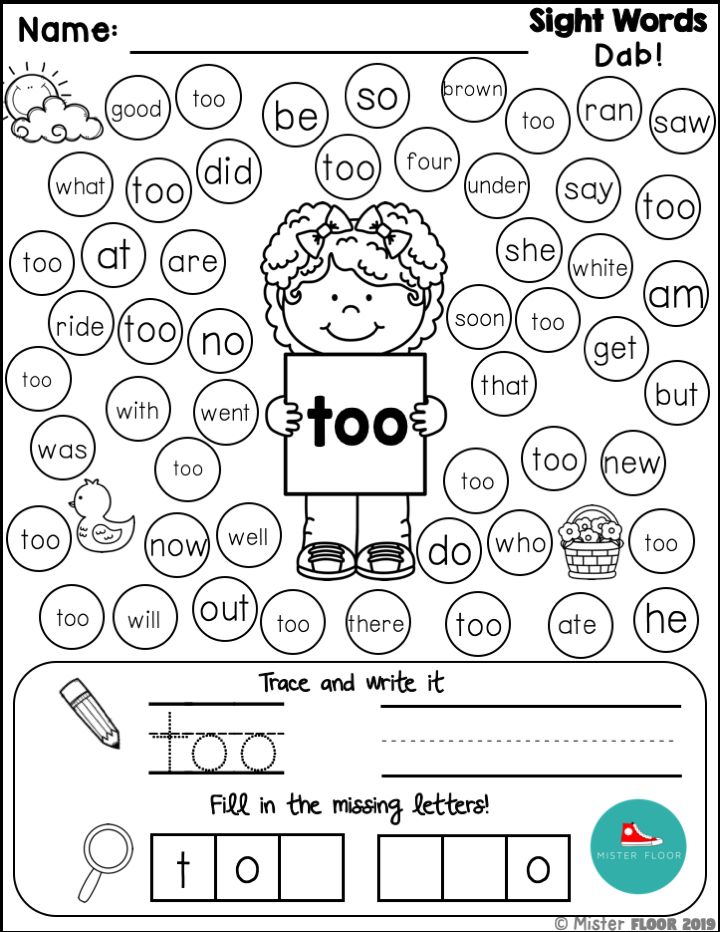

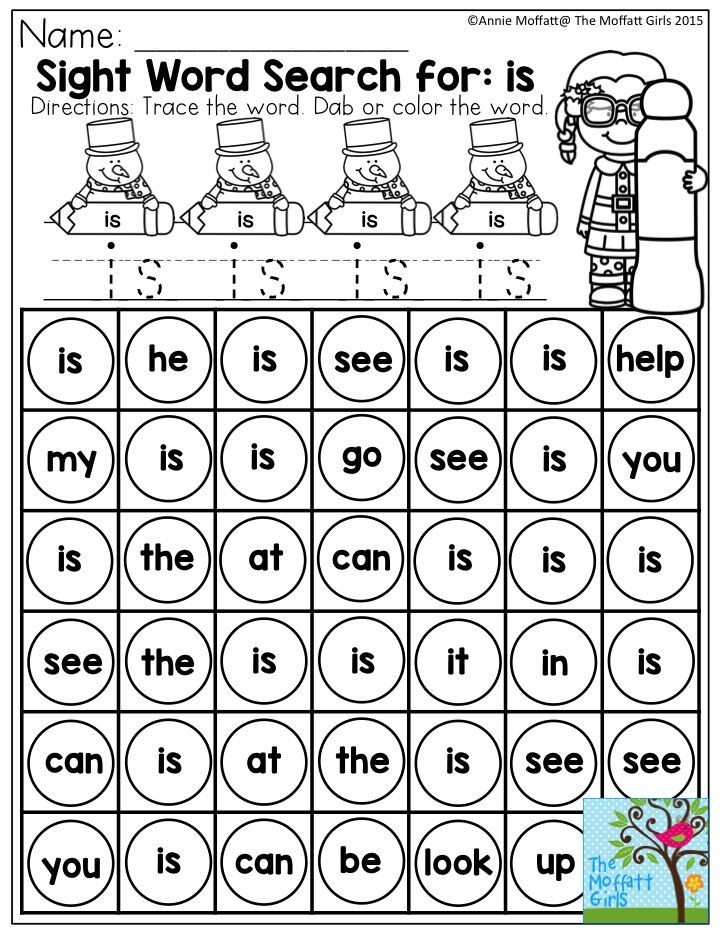

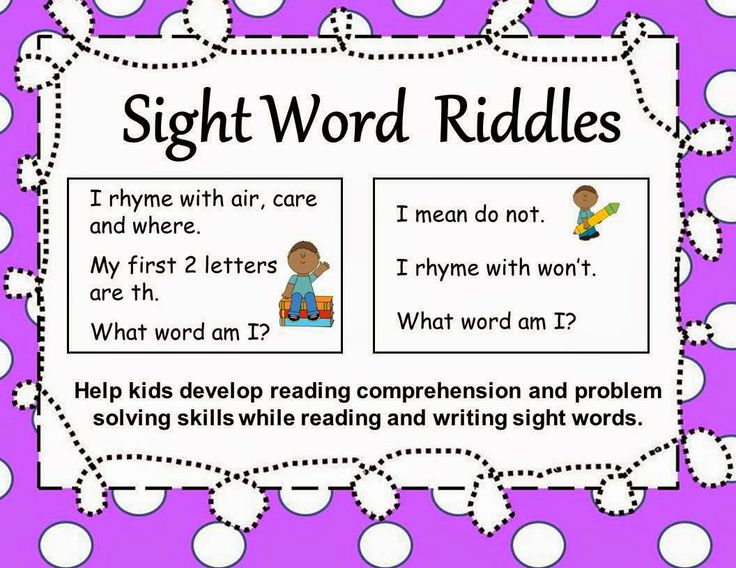

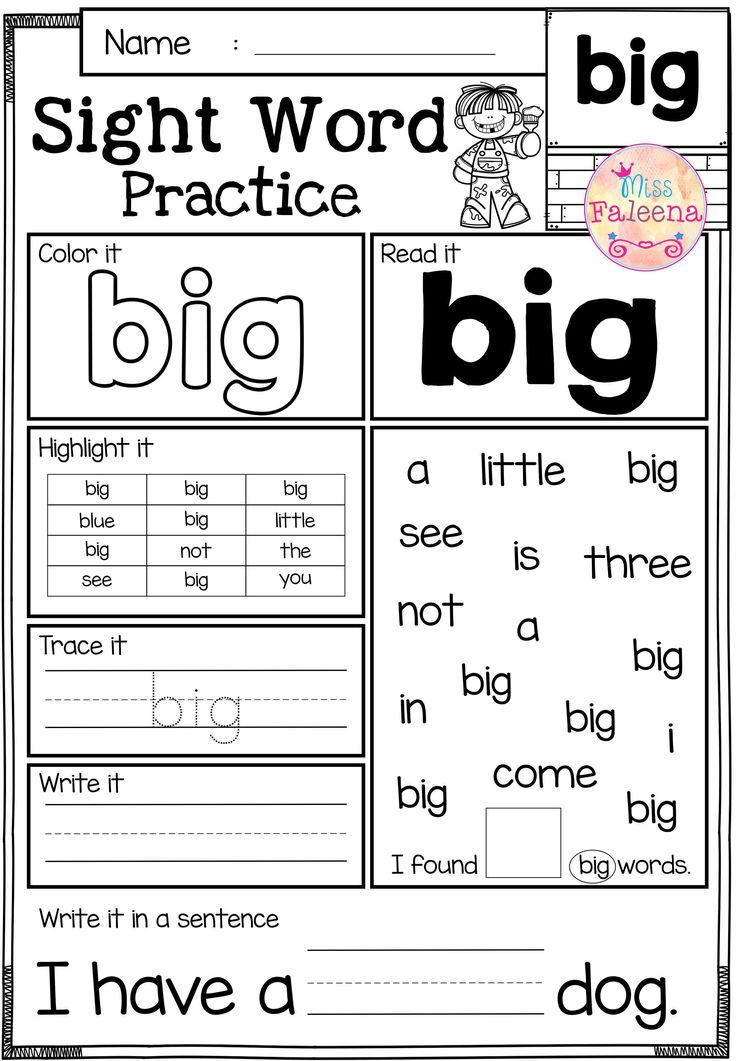

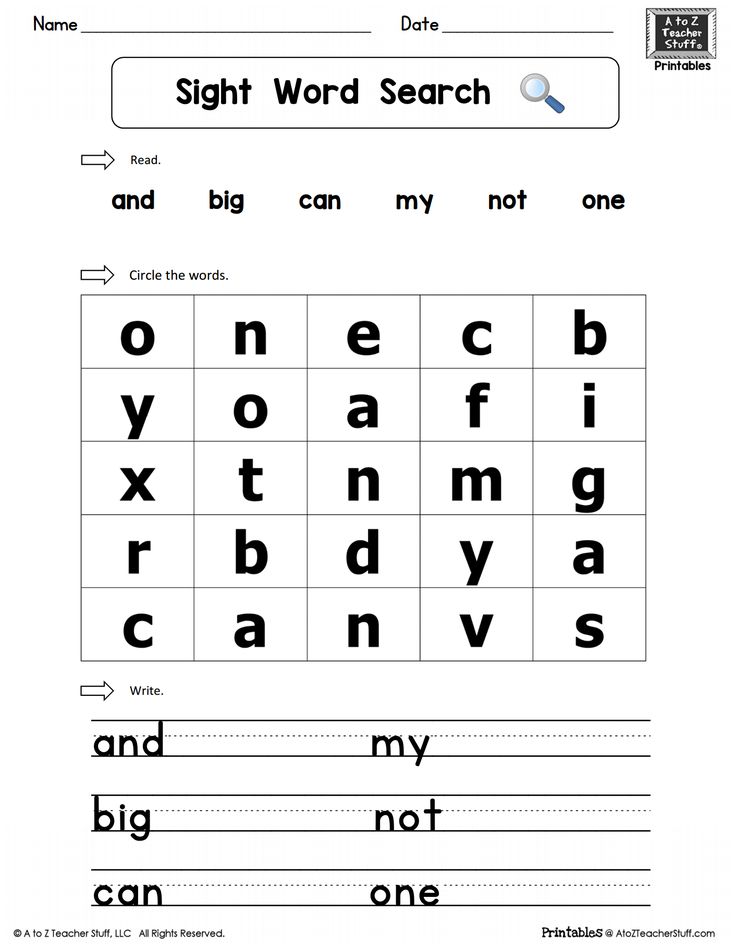

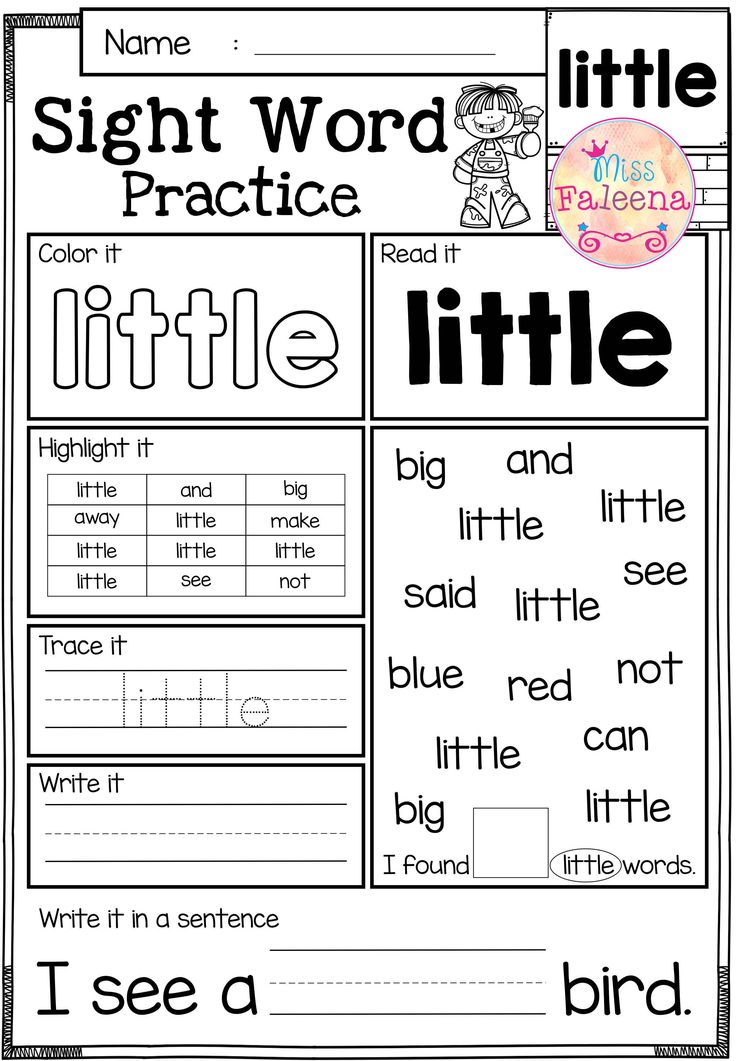

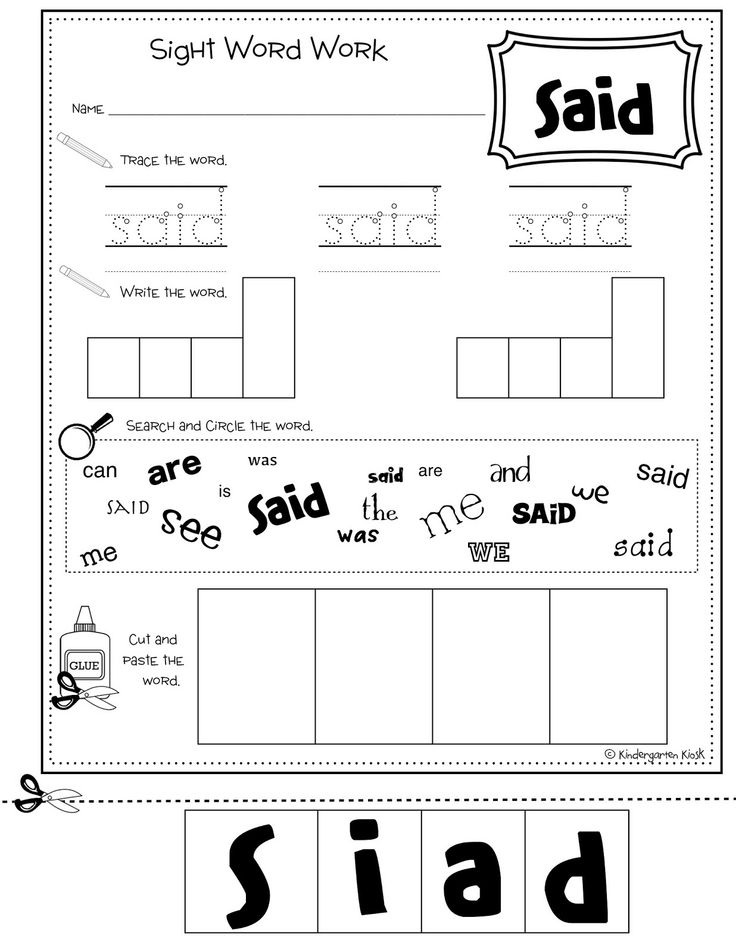

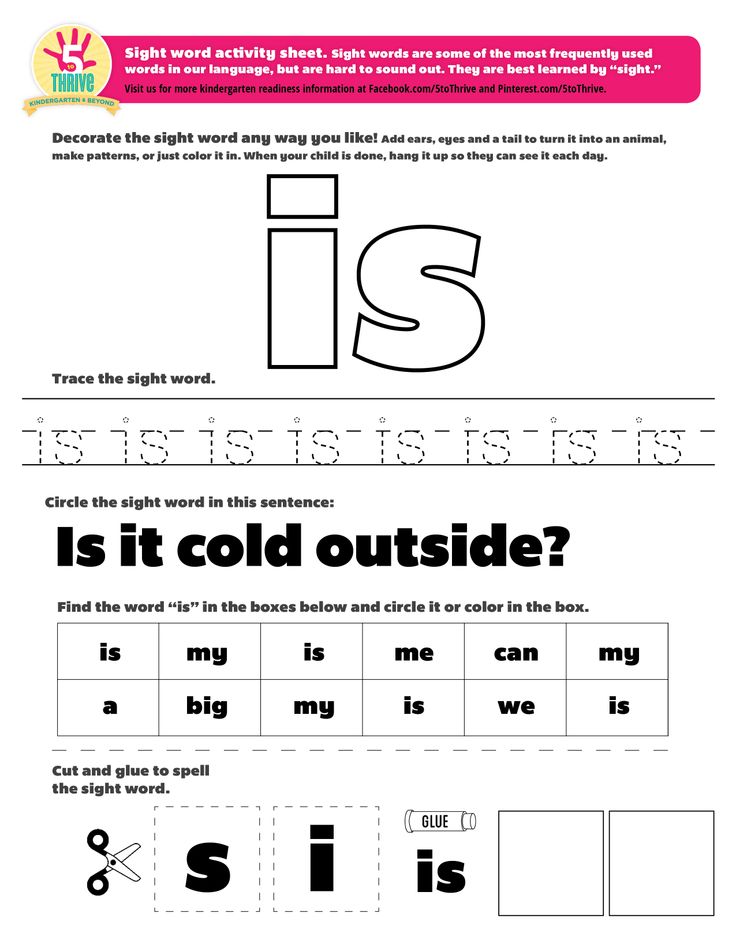

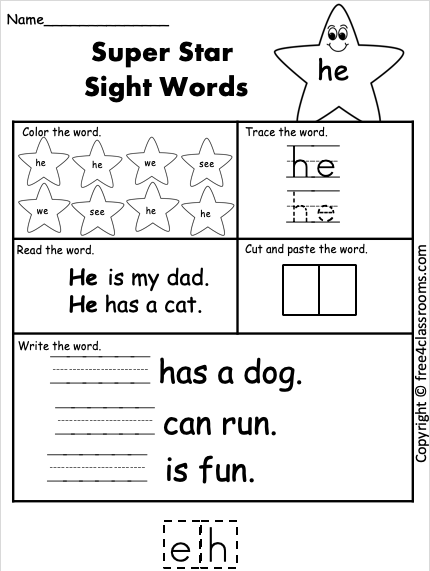

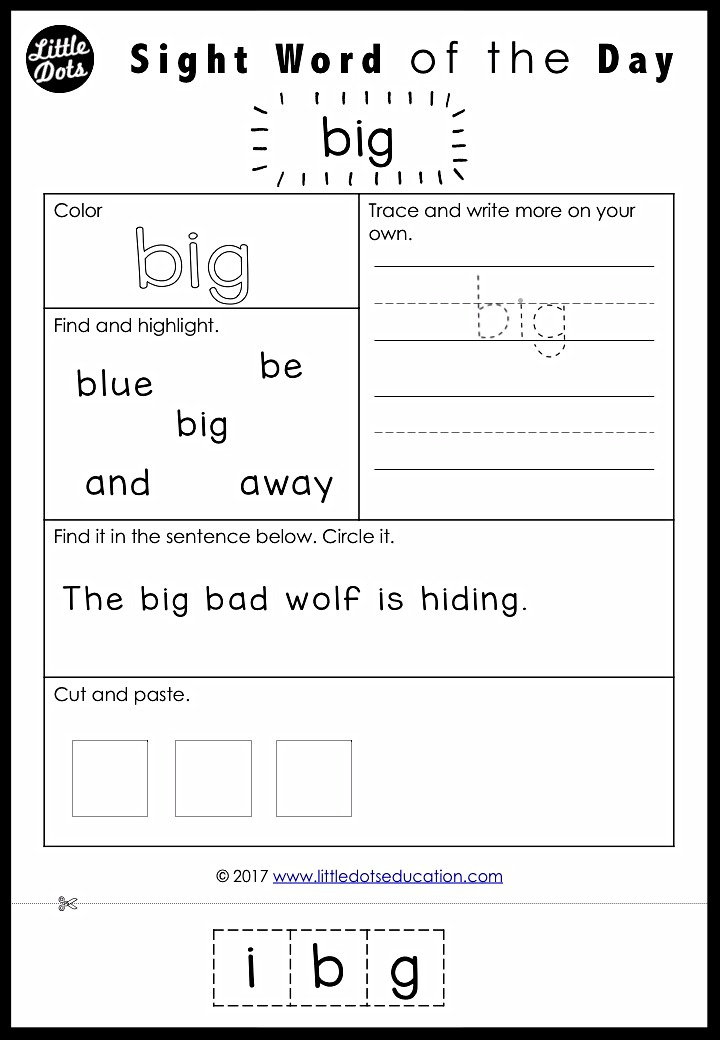

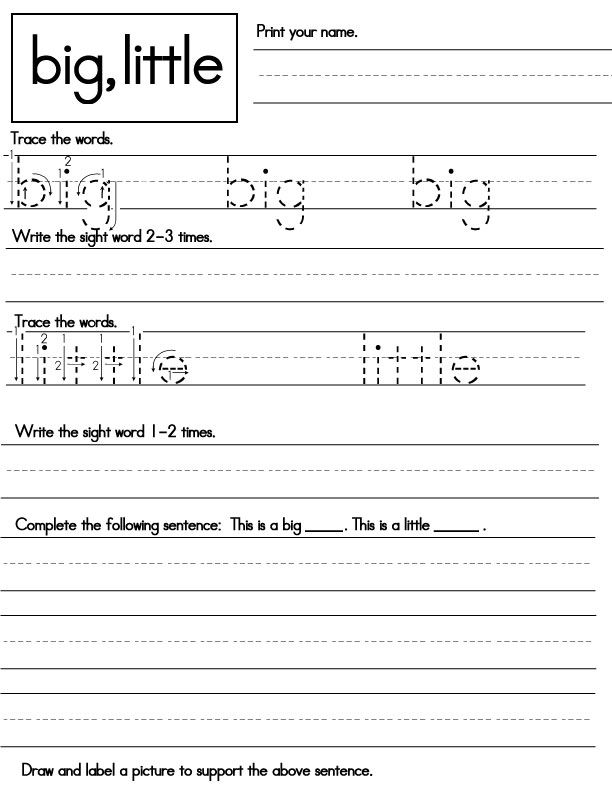

| How these words are taught | For kids with reading challenges such as dyslexia, teachers typically use multisensory structured language education (MSLE). That includes multisensory techniques to help kids connect letters to sounds. One such teaching approach is Orton–Gillingham. A few reading programs are based on this approach. There are also other reading programs that are mainly used in general education. In the early grades, these programs focus on decoding skills. | Teachers introduce groups of words to students, based on grade level. Students may take these words home and work on memorizing them. Kids learn best when working and practicing with small groups of words on a regular basis until the words are instantly recognizable. It can help if students practice reading these words in meaningful sentences. It can also help to find the irregular part of the word and highlight it to make it easier to remember. For example, in the word said, the irregular part of the word is ai. |

| What kids need to know | There are rules that can help them sound out words. | Some common words don’t follow rules and can’t be sounded out. These words need to be memorized. Words with similar meaning or similar spellings can be learned in groups. For example, these ight words: right, night, flight. |

| How you can help | There are multisensory techniques and tools parents can use to teach phonics. There are also strategies for building phonological awareness at different ages. | There are strategies for teaching non-decodable words to struggling readers. Parents can review lists of sight words, including non-decodable words, with their child. |

If your child is struggling with reading and you’re concerned the cause might be dyslexia, there are steps you can take. Your child might be eligible for services and supports at school that can help.

Also, hear an expert explain why learning to read is harder than learning to speak. And learn about how different learning and thinking differences make it hard to read.

Learning to read involves both decoding and recognizing sight words at a glance.

High-frequency words can be decodable or non-decodable.

Struggling readers may benefit from multisensory reading instruction.

When To Teach Sight Words With Preschoolers

3-5 years old learning to read with phonics sight words

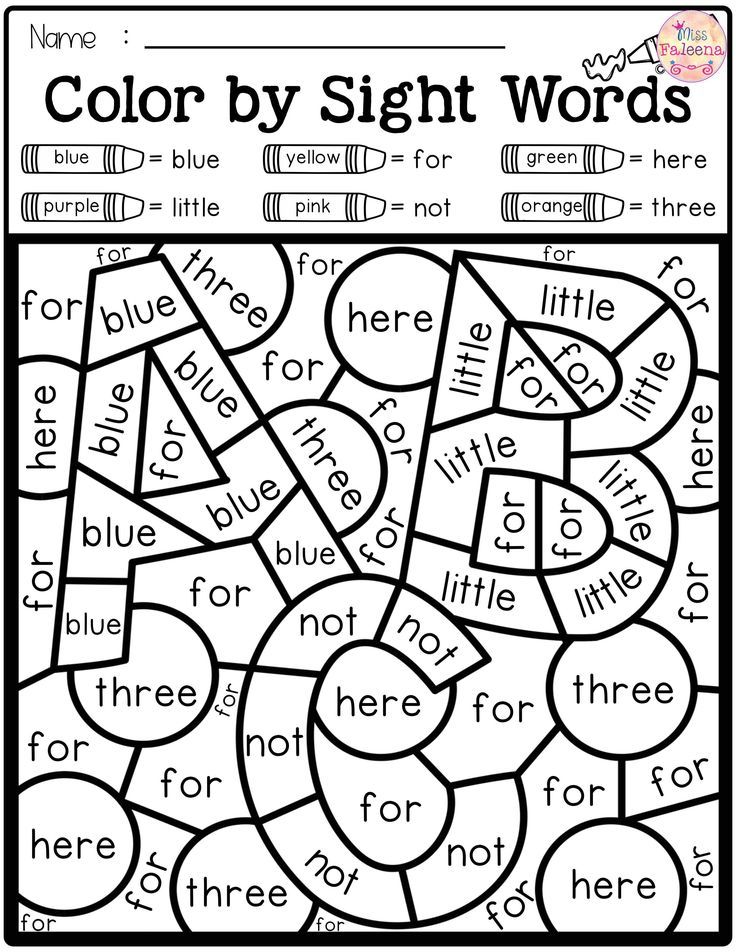

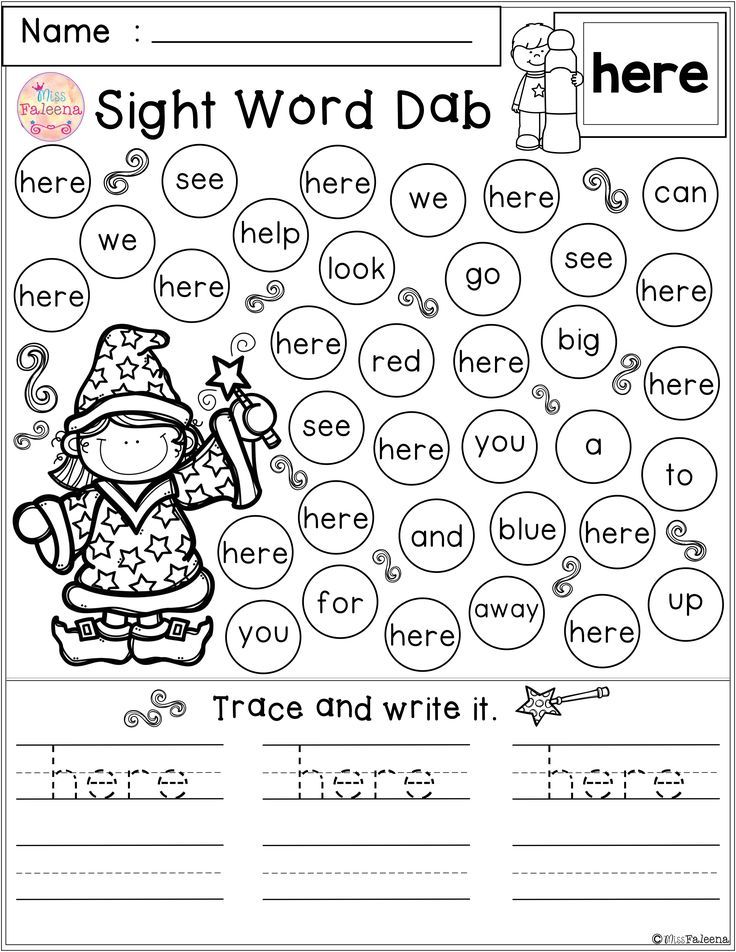

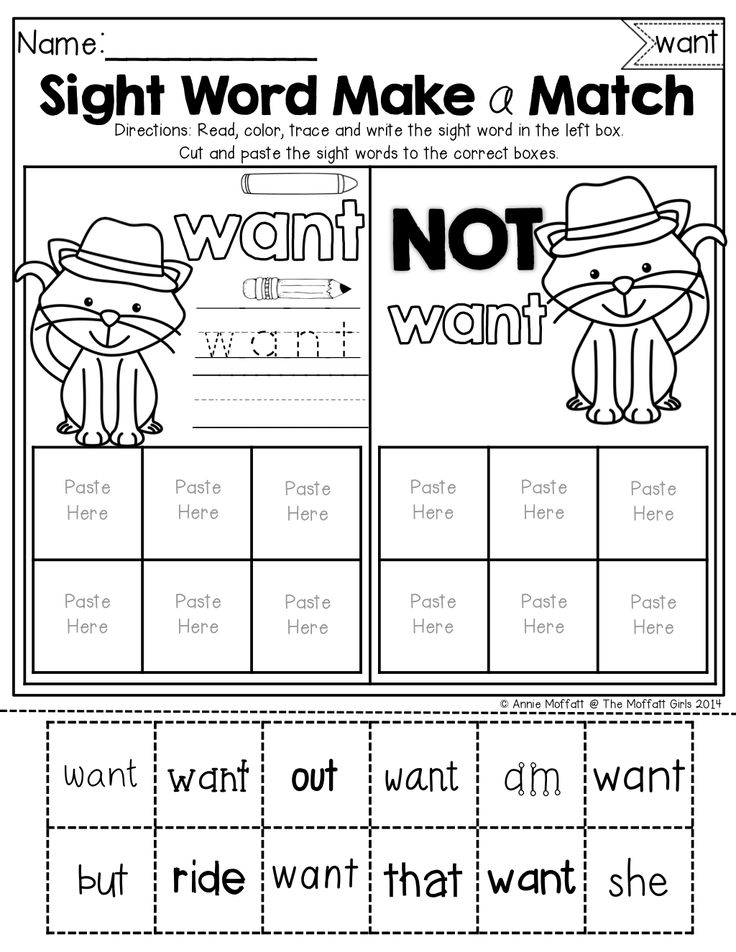

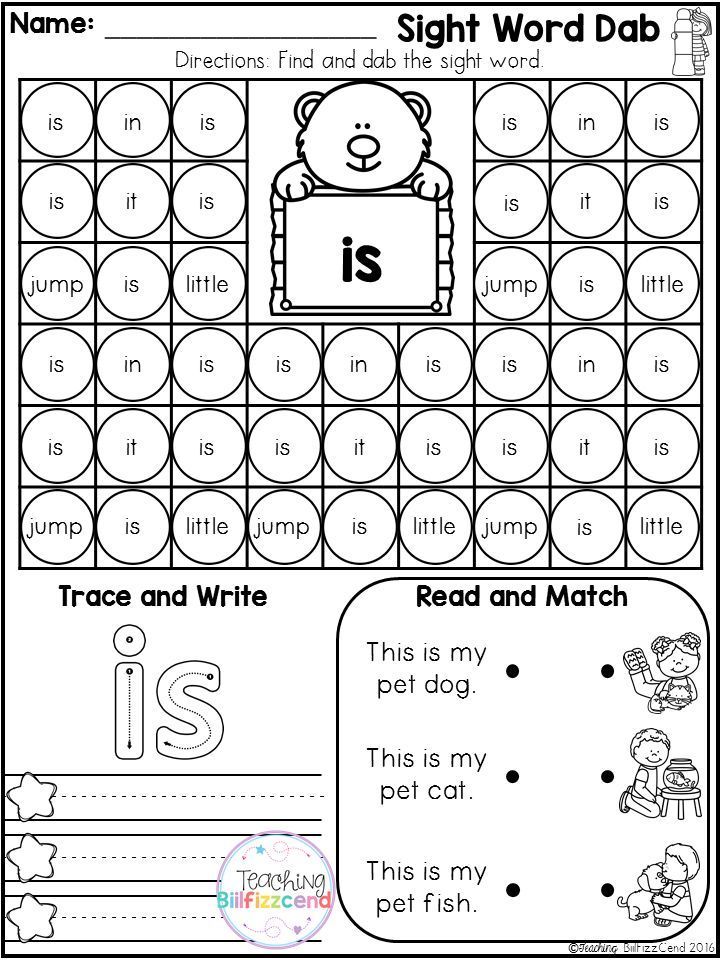

No doubt you’ve come across sight words lists and sight words worksheets when looking for alphabet activities on Pinterest to help your preschooler get ready for reading.

Now that's got you wondering when to teach sight words with your preschooler and questioning if it's really necessary for children to memorize so many words.

My hope is that this article will help you understand the meaning of sight words and avoid problems that can come from getting your preschooler to memorize lots of words too early in the journey to reading.

Meaning of Sight WordsYou might be wondering about the meaning of sight words, and if they are the same as high-frequency words.

A sight word is any word that is recognized and read at a glance.

Why Teach Sight Words?Advocates of teaching sight words say that the most common words used in English should be memorized so they can be recognized on sight to improve reading fluency and comprehension.

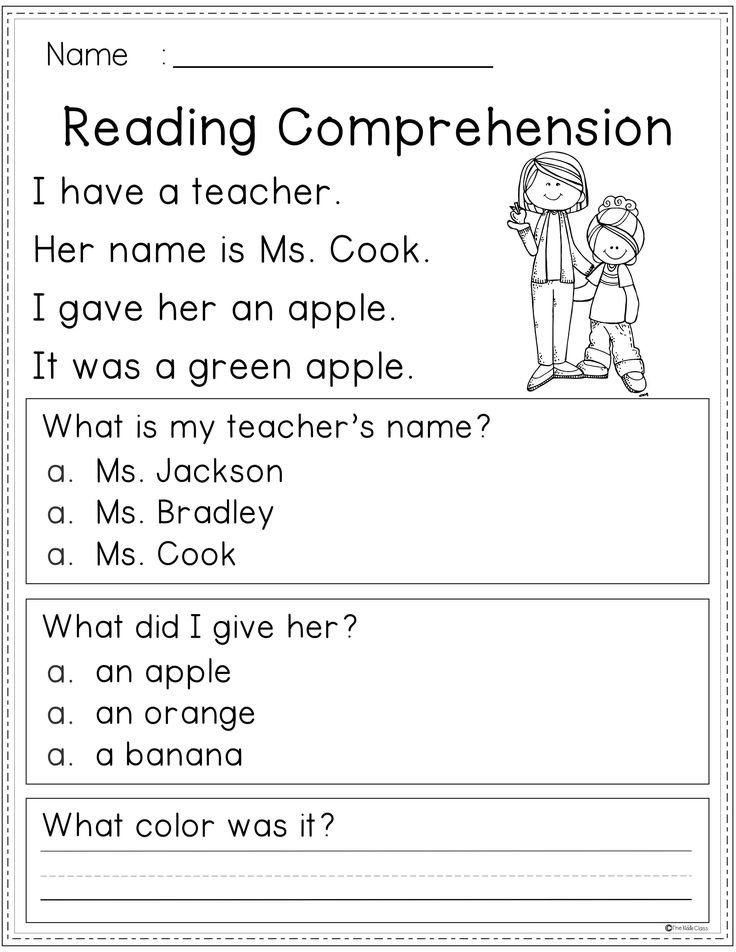

The idea is that children who can recognize these common English words at a glance can then concentrate on understanding what they have read instead of having to stop and decode each word.

The Problem With Sight Words

One of the biggest mistakes when it comes to helping children learn to read at home is getting them to memorize lists of sight words before they understand that words are made up of speech sounds in a row.

Memorizing sight words does NOT equal learning to read!

It used to be thought that reading is a visual memory process. This “whole word” or “whole language” approach assumed that if children see words often enough, those words will be stored in the memory as visual images.

This is why some beginning reader books feature predictable and repetitive sentences with lots of high-frequency words and pictures to provide context and help children guess the right word.

A good example is the Dick and Jane series, or levelled reader books with text like “Feet are neat! They can jump. They can ride.”

Why Teach Phonics First?Current research from cognitive scientists and neuroscientists indicates that the best way to teach children to read is through phonics. That means explicit instruction of the code between speech sounds and written symbols.

That means explicit instruction of the code between speech sounds and written symbols.

Specifically addressing the question of sight words vs phonics, Stanford Professor Bruce McCandliss found that beginning readers who focus on letter-sound relationships increase activity in the area of their brains best wired for reading compared with memorizing whole words.

Reading programs that put phonics first discourage guessing at words or relying on pictures for context. Children practice reading skills by sounding out decodable text using existing knowledge of the phonetic code.

High-frequency words that are tricky or cannot be decoded are taught as they are encountered.

All words eventually become “sight words” for a skilled reader.

Although it seems as if skilled readers have memorized words because they recognize words automatically, that’s just because decoding happens so fast!

See for yourself how quickly you can read words that you’ve never seen before such as “thab” or “porlain”. It’s because these words have letter sequences that follow regular phonetic rules.

It’s because these words have letter sequences that follow regular phonetic rules.

Although there IS a time to invite your child to memorize a few high-frequency words to improve reading fluency, you can create problems if you encourage your preschooler to memorize lots of words too early in the journey to reading.

First, it’s a waste of time and energy to focus on getting your preschooler or kindergartener to memorize words that can be easily decoded using phonics knowledge.

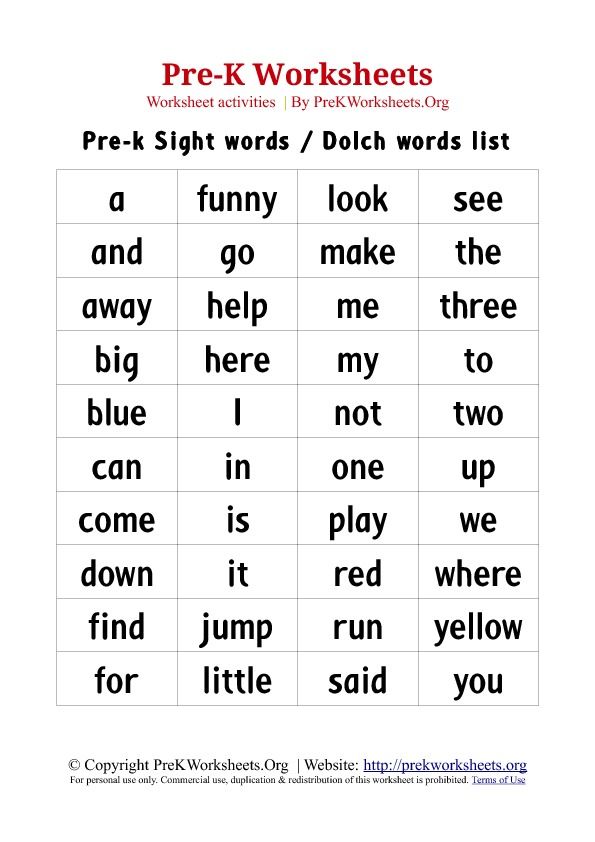

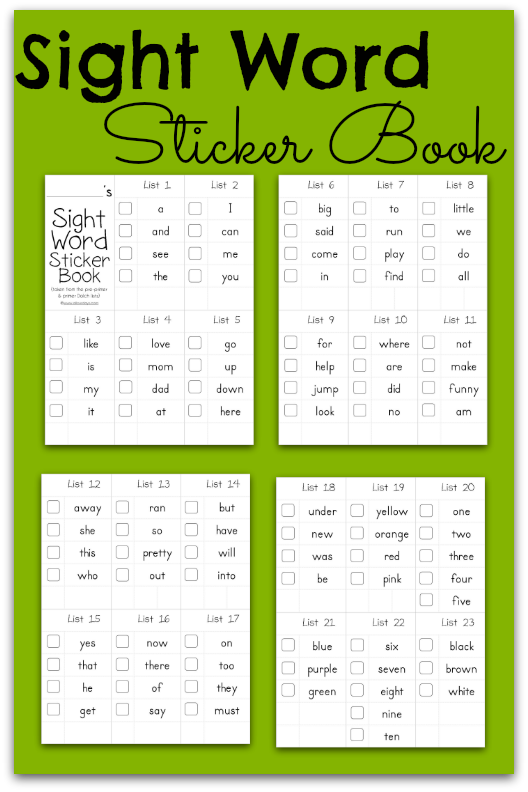

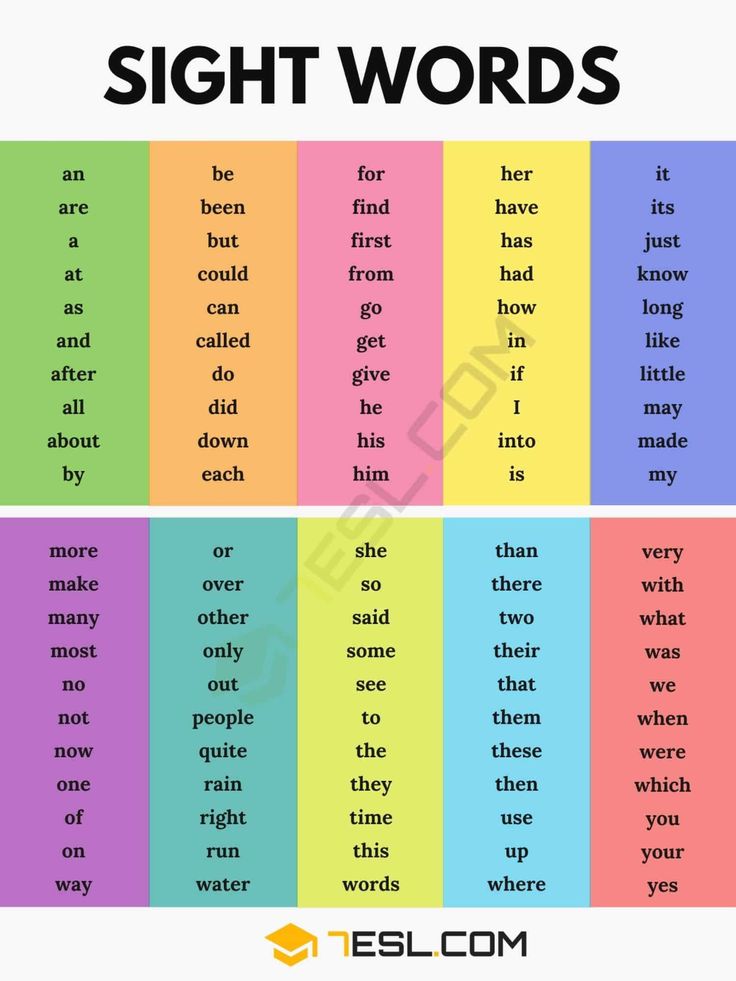

Two common sight words lists are the Fry sight word list and the Dolch sight word list. At first glance, you might think that many words on these sight words lists are not decodable. But this simply isn’t true!

If you look at the pre-primary and primary Dolch words and the first 100 Fry words for Kindergarten, you’ll see that many of these words can be easily sounded out and read by a child with a knowledge of the sound-letter associations for the alphabet letters (i. e., and, a, in, it, on, at, had, but, not, can, him, am, its, did, get, up, big, red, jump, help, run, will, yes, went, well, ran, must).

e., and, a, in, it, on, at, had, but, not, can, him, am, its, did, get, up, big, red, jump, help, run, will, yes, went, well, ran, must).

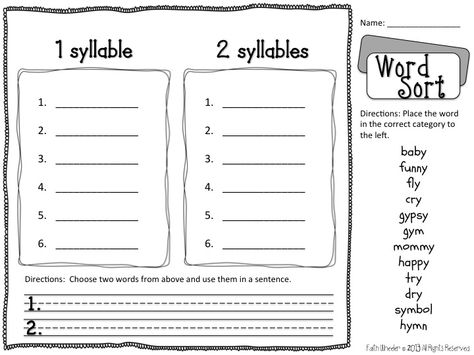

Some words are tricky because they include digraphs that a child may not have learned yet. A digraph is two letters that represents a single speech sound.

Once a child learns specific digraphs including or, oo, ow, ee, ue, ay, a_e, th, ou, i_e, a_e, ea, ew, er, wh, ir, then even more sight words from the Dolch and Fry word lists can also be easily decoded using phonics knowledge (i.e., for, look, down, see, blue, away, make, play, three, that, with, out, like, this, now, came, ride, good, brown, eat, new, soon, our, ate, say, under, or, when, time, number, way, than, been, first, made, white).

There is no need to memorize words that can be decoded!

A child who has memorized 100 words can only “read” 100 words. A child who has learned the sound-letter correspondences for the alphabet and several digraphs can read hundreds of words!

Instead of looking for strategies to make sight words stick in your child’s memory, you can just teach your child how to READ them using phonics.

A problem with teaching sight words that are actually decodable is that children can begin to think that the English language doesn’t make sense. Then they might get in the habit of guessing at words instead of looking for patterns.

This is a real concern when young preschoolers are introduced to sight words before they have started developing phonemic awareness and understand that words are made up of individual speech sounds in a row.

Guessing at words is common among children who have been taught using the whole word approach.

Instead of paying attention to each phonogram (sound-letter correspondence) in an unknown word and sounding it out, they try to figure out the word based on clues from the initial letter, the shape of the word and accompanying pictures. They may even have been told to skip words they don’t know!

An example is a child who says “horse” when the word is “house” because he or she is relying on how the word looks instead of noticing the ou and trying to decode the word sound by sound.

In contrast, learning phonics is all about learning the patterns of sound-letter correspondences to build the reading network in the brain.

Remember, teaching children to sound out “l-oo-k” sparks more optimal brain wiring than getting them to memorize the word “look”.

Plus, a child who knows the oo phonogram can easily decode other words with the same phonogram such as book, took, shook, foot, hook, wood, cook and wool.

Sight Words vs PhonicsIt’s not a question of phonics OR sight words when it comes to helping your child learn to read!

It’s a matter of making sure that your child has a solid understanding of phonics BEFORE asking your child to memorize whole words.

When To Start Sight Words?The ideal time to teach sight words is AFTER your child has already begun using existing phonics knowledge to sound out words and is well on the way to developing strong decoding skills.

At this stage, your child understands that words are made up of sounds in a row and understands that a letter or combination of letters represents an individual speech sound.

Now that your child has a solid phonetic base, it’s OK to encourage your child to memorize some high frequency words to boost reading fluency.

How many sight words should a kindergartener know?You might also be wondering how many sight words your kindergartener should know, and which sight words to teach.

To find out exactly how many sight words your child needs to know, find some decodable readers that you plan to use with your child and see which tricky high-frequency words they include (e.g., the, you, is, I, said, are, there).

When you choose to focus on phonics first and then teach tricky high-frequency words as they are encountered, you’ll find that your list is much shorter than those Dolch and Fry sight words lists that you’ll find on Pinterest. No more feeling pressured to get your child to memorize hundreds of words!

If you’re looking for a reading program that doesn’t require your child to memorize hundreds of words, check out The Playful Path to Reading™. It takes the guesswork out of helping your child learn phonics using fun, hands-on activities. You can watch my FREE CLASS if you first want to learn more about my gentle, child-led approach to teaching reading at home.

It takes the guesswork out of helping your child learn phonics using fun, hands-on activities. You can watch my FREE CLASS if you first want to learn more about my gentle, child-led approach to teaching reading at home.

How to determine the perfect and imperfect form of the verb?

Let's learn how to write without errors and make interesting stories

Start learning

202.7K

Harry Potter's girlfriend used the time-wheel to be in two places at the same time. Different types of verbs will help to describe the actions of Miss Granger. There are only two of them: perfect and imperfect. Let's talk about them in more detail.

Basic definitions

First, let's remember what a verb is. nine0003

The verb is a part of speech that designates an action or state as a process and expresses this meaning using the categories of aspect, voice, mood, tense and person.

Verbs answer questions: what to do? what to do? what have you been doing? What did you do? what do they do? what will do?

Examples of verbs:

The form in Russian is a constant grammatical feature of verbs, which is possessed by conjugated verbs, infinitives, gerunds and participles. It shows how some action of the verb proceeds in time:

-

completed and one-time (read, passed)

-

unfinished and repeatable (lives, does).

What types of verbs are there in Russian:

-

perfective;

-

imperfect appearance.

Now let's find out what the perfect and imperfect form of the verb is and give examples of perfect and imperfect verbs. nine0003

nine0003

Demo lesson in Russian

Take the test at the introductory lesson and find out what topics separate you from the "five" in Russian.

Perfective verbs

Perfective verbs in the indefinite form answer the question: what to do?

Perfective verbs have two tense forms:

In any tense form they call:

-

an action that is limited by some limit;

nine0029

result, completion of an action or a separate stage.

Examples of perfective verbs:

-

what did you do? sat down - past tense, the action is completed and was done once, that is, it was not repeated;

-

what will they do? they will talk - the future simple tense, the action will be done and will not be repeated.

-

what to do? close, pay, perform;

-

what to do? identify, answer, simplify.

Perfective verbs can also denote actions that have already begun or are about to begin: I spoke, I will speak.

Imperfect verbs

Imperfect verbs in the indefinite form answer the question: what to do?

Imperfective verbs have three tense forms:

They denote:

-

action in length, without indicating its limit; nine0003

-

action incomplete.

In any tense form, they denote a recurring or continuing action, without indicating whether the action has been completed.

Examples of imperfective verbs:

-

what did you do? jumped - past tense, the action could be repeated several times and it is not known whether the result was achieved;

-

what are they doing? they are watching - the present tense, the action continues and it is not known how long the action has been going on and how long it will continue; nine0003

-

what will I do? I will dance - the future is a difficult time, the action can be repeated and there are no signs that it will be completed.

-

what to do? talk, paint, run;

-

what to do? drag, go.

Imperfective verbs can also denote actions that have begun, are beginning or will begin: I looked, I look, I will light.

Now we know what questions are answered by perfective and imperfective verbs. And here is a cheat sheet to fix and learn the difference of two types:

Formation of verb types

Perfective verbs can be formed from imperfective verbs in different ways.

Ways of education:

-

Adding a prefix: read - read, sit - sit up.

-

Rejection of suffixes: give - give, save - save. nine0003

-

Replacement of suffixes: decide - decide, jump - jump.

-

Replacement of suffixes and alternation of letters in the root: forgive - forgive, wither - wither.

When forming imperfective verbs, the alternation of consonants and vowels is possible at the root: be late - be late, state - state, protect - protect.

Learn Russian at the Skysmart online school with attentive teachers and interesting examples from modern texts. nine0003

Determine the form of the verb

If you are in doubt about how to understand what kind of verb you have: perfect or imperfect, use these methods:

| How to determine the aspect of a verb |

|---|

|

Now you can easily tell your classmates how to determine the form of a verb in Russian.

Examples of pairs of perfective and imperfective verbs

Aspective pair are verbs that have a perfective and imperfective form. nine0003

Some Russian verbs have the same lexical meaning, but differ in the grammatical meaning of the form. For example: what to do? decide what to do? solve.

Such aspectual pairs differ in the way of word formation:

-

Through the suffix: quit - throw, meet - meet, offend - offend, reach - achieve, decide - decide.

-

Through the prefix: cook - cook, call - name, work - process, speak - talk, read - finish reading. nine0003

The aspectual pairs of verbs can differ:

-

Stress.

fall asleep - fall asleep, cut - cut.

-

Roots.

what to do? catch - what to do? catch;

put - put;

invest - invest;

take - take;

search - find.

The aspect of the verb may depend on the context of the sentence. For example:

-

She is now (what is she doing?) sleeping with a friend. — Present tense, imperfective form.

-

Tomorrow (what will she do?) is staying with a friend. — Future tense, perfect form.

Such verbs are called two-part verbs, they include: telegraph, take possession, spend the night, injure, marry, execute, promise, use, attack and others. Two aspect verbs can denote both a complete action and an action in length. nine0003

nine0003

Table of perfect and imperfect verbs

| | imperfective | Perfect look |

|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | What to do? play | What to do? play |

| Past tense | What did you do? played | What did you do? played |

| Present | What am I doing? playing | - |

| Future tense | What will I do? will play | What will I do? play |

Cheat sheets for parents

All Rules in Russian at hand

Lidia Kazantseva

Author Skysmart

to the previous article

174. 3k

3k

Ravigan Comony

for the next article

Corpoents

Get a plan for the development of speech and writing at a free introductory lesson

At an introductory lesson with a tutor

-

We will identify gaps in knowledge and give advice on learning

-

We will tell you how the classes are going

-

We will select the course

90 "0 0 "search Daria Markasova

15129 1 07/13/2020

The story of how a student did not believe me, or Why the verbs "search" and "find" are not an aspect pair

We lived together and peacefully, until one day at the lesson we came across the word “find”. One of the students decided to clarify with me the translation of this verb into Chinese. Our dialogue looked something like this:

Our dialogue looked something like this:

Agree, the situation is awkward. I don't want to tell a student that the teacher who taught him before gave the wrong information. And even less do you want to look stupid yourself, standing at the pulpit.

I will say right away that the student did not have to be convinced for a long time. I replied that, perhaps, in some old textbooks it was written like that, but the authors of modern textbooks no longer consider the verbs “search” and “find” as an aspect pair. The student quickly found confirmation of my words in the electronic dictionary and calmed down. But I was interested in the question of where my Chinese colleague got such information from. This was the impetus for a little research. nine0003

It is only unclear why they forgot about the existence of the verb "find". They say that you can’t throw words out of a song, but, apparently, a verb from a language is easy.

As it turned out, the idea that the pair of verbs "search - find" is specific is not at all a mistake of an individual teacher or textbook author. This is a kind of incident not only in the practice of language teaching, but also in Russian aspectological theory in general.

Of course, this delusion did not arise from scratch. Of course, “search” and “find” are two verbs that are closely related in meaning. They correlate as a designation of process and result, as well as pairs of verbs “select - select” or “put - put”, which are really specific. In addition, these verbs often occur in the same context. I’m sure everyone has heard the phrase “he who seeks will always find” more than once. Even without any detailed analysis of the frequency of use, it is obvious that the imperfective verb “find” is much less common in speech than the verb “search”, as well as the perfective verb “find”. But this, of course, does not mean at all that it does not exist in the Russian language. nine0003

First, I analyzed the information in the Russian language textbooks for secondary schools of the following authors: M. M. Razumovskaya, E. I. Bykova, L. M. Rybchenkova and some others. In none of them are the verbs "search" and "find" marked as a specific pair. But, I suppose, this does not mean that there are no textbooks where such a pair appears. So, for example, on the INFOOUROK website there is a summary of the Russian language lesson for the fourth grade, in which such a species pair is present (link https://infourok.ru/material.html?mid=169034). Unfortunately, the summary does not indicate which textbook is used to teach the Russian language at this school, but I suspect that the teacher did not take the information out of thin air.

Much more interesting is the situation with grants for foreign students. For example, in “Practical Grammar” by I. B. Ignatova, a textbook for students of the preparatory faculty “We study the types of the verb” by L. V. Arkhipova, as well as in the manual “Pure Grammar” by E. R. Laskareva, the verbs “search - find” are listed along with other heterogeneous verbs that form aspect pairs. This pair is also considered as a species pair in Yu. D. Apresyan's Lexical Semantics. It will not be difficult to find similar information on sites dedicated to the Russian language. Here, for example, is a screenshot of the site nado5.ru (full link to the article http://www.nado5.ru/e-book/vidy-glagola). nine0003

This pair is also considered as a species pair in Yu. D. Apresyan's Lexical Semantics. It will not be difficult to find similar information on sites dedicated to the Russian language. Here, for example, is a screenshot of the site nado5.ru (full link to the article http://www.nado5.ru/e-book/vidy-glagola). nine0003

And from the site hi-edu.ru/ (full link to the material http://www.hi-edu.ru/e-books/xbook107/01/part-093.htm).

It can be seen that in many practical and theoretical works, the pair "search - find" is included in the number of species. I would only like to ask the authors of these works where they divided the verb “find” and with what perfective verb they pair it.

Why is it that a couple of verbs “search for – find” is not specific?

Many authors still agree that the pair "search - find" is not specific. Firstly, as we have already seen above, in most Russian language textbooks this pair is not mentioned among the aspectual ones formed by verbs of different roots. Secondly, this point of view is supported by many authors involved in the study of theoretical issues of the Russian language. Look, for example, "Introduction to Russian Aspectology" by A. A. Zaliznyak or "Problems of Functional Grammar" by A. V. Bondarko. The authors, as a rule, say that these verbs are a purely lexical pair, and not a specific one, since they do not meet the criterion of Yu. S. Maslov's specific pairing. This criterion will be discussed below. nine0003

Secondly, this point of view is supported by many authors involved in the study of theoretical issues of the Russian language. Look, for example, "Introduction to Russian Aspectology" by A. A. Zaliznyak or "Problems of Functional Grammar" by A. V. Bondarko. The authors, as a rule, say that these verbs are a purely lexical pair, and not a specific one, since they do not meet the criterion of Yu. S. Maslov's specific pairing. This criterion will be discussed below. nine0003

The main requirement for establishing aspectual pairs is the common meaning of perfective and imperfective verbs. According to the above criterion, in order to combine verbs into an aspect pair, there must be contexts in which the semantic meaning between perfective and imperfective verbs is eliminated, that is, when a perfective verb can be replaced by an imperfective verb without changing the meaning of the statement.

Compare, for example, the following two sentences:

1) After much persuasion, he still convinces his sister to return home and they go there the next day.

2) After much persuasion, he nevertheless convinced his sister to return home and they went there the next day.

The highlighted forms of perfective and imperfective verbs in this context have the same meaning.

Now look at the sentences:

1) He finally finds the keys and we enter the apartment .

2) He finally found the keys and we entered the apartment .

The verbs of the "find - find" pair can replace each other in this context, but the verb "search" in this context cannot be used in any way. The verb "search" cannot take on the same meaning as the verb "find" in any context.

Conclusion

The verb "search" denotes an action - a process aimed at achieving a result, which in turn is denoted by the verb "find". The connection between these two verbs is similar to the connection between the verbs “to aim” and “to hit”.

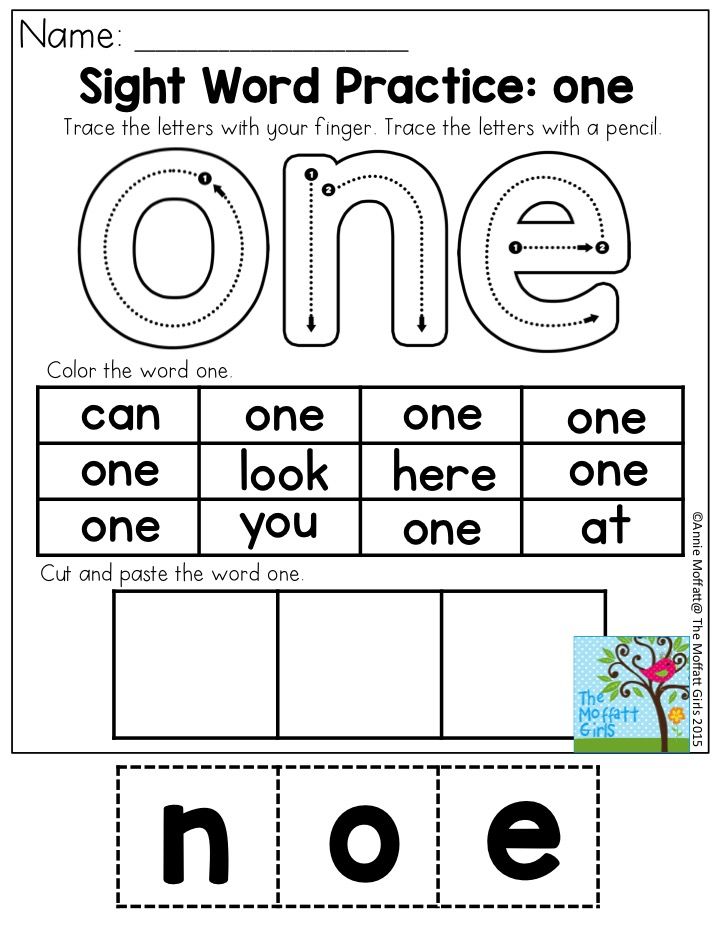

Kids turn a word into a sight word by mapping unexpected (non-phonetic) sequences of letters to their sounds.

Kids turn a word into a sight word by mapping unexpected (non-phonetic) sequences of letters to their sounds.

They can talk about the letter patterns in irregular sight words that don’t follow the rules.

They can talk about the letter patterns in irregular sight words that don’t follow the rules.