Story of letters

Stories told through letters | The Flower Letters

Immerse yourself in a brand new storytelling experience full of history, romance and pulse pounding adventure, delivered to your doorstep 2X/Month.

Choose Your Adventure

Choose Your Adventure

Free Shipping In

US

Risk Free Cancel

Anytime

500,000 Letters

Delivered

Introducing

Our newest story

Welcome to a brand new storytelling experience full of history, romance, and pulse pounding adventure.

Ready to step back in time to experience powerful stories of love and intrigue, all told through actual letters?

Subscribe for $12/mo and receive 2 beautifully illustrated letters per month for an entire year. Each letter is packed with elements designed to enhance the storytelling experience. Whether it's a telegram, post card, coded message or map - each will draw you deeper into this truly immersive story experience.

Tired of getting mail you don't love? When you subscribe you'll look forward to checking your mail in anticipation of the next installment of our stories. Each story takes place on the pages of intimate and personal letters sent between characters, drawing you into their hopes and dreams and the greater world around them. Sit back, maybe make a cup of tea, take a break and immerse yourself into this brand new mailbox story experience.

The Adelaide Magnolia Collection is set in Jane Austen’s England. The year is 1817 and the Prince Regent is ruling in Mad King George’s stead.

The Adelaide Magnolia Collection is our newest story collection.

LEARN MORE

In our premier story, Audrey Rose, we explore what it might have been like to live through WWII. To experience the range of emotions leading up to the war…the triumphs and heartbreaks…the indelible moments that might carry you for months or even years of longing and wondering…

What if?

Will they ever come back to you?

Will your story end happily ever after?

Set in the anything-goes, rip-roaring Old West, the Lily Clara series is big on adventure, intrigue, and of course, unforgettable romance. Throw in an outlaw chase, a vengeful vigilante, and a good old fashioned Spanish treasure hunt, and the Lily Clara Collection is a wild western like no other!

Throw in an outlaw chase, a vengeful vigilante, and a good old fashioned Spanish treasure hunt, and the Lily Clara Collection is a wild western like no other!

We are proud to introduce an exciting new fantasy adventure storytelling experience! This time, in a temporary departure from historical fiction, we’re diving deep into a fantastical world to bring you full-tilt adventure, enchanted creatures, and an immersive inter-dimensional mystery you won’t want to miss!

LEARN MORE

Lose yourself in an

unforgettable journey.

The Flower Letters are more than just…letters. Each story collection is packed with historically accurate inserts designed to take you ever further into the story, era and experience. Our historical fiction stories are intricately researched and center around a specific era or event in our world's history.

From the moment you open your mailbox to the umpteenth time you find yourself re-reading that month’s delivery of letters and inserts, you may just find yourself lost in another time and place.

SHOP NOW

Lose yourself in an

unforgettable journey.

The Flower Letters are more than just…letters. They’re intricately researched, highly interactive works of historical fiction. Each series is centered around a specific era or event, giving you, the reader, a much richer and more compelling view of the lives of your characters.

This isn’t just a story you read. This is an immersive experience like never before. From the moment you open your mailbox to the umpteenth time you find yourself re-reading that month’s delivery of letters, you may just find yourself lost in another time and place.

LEARN MORE

Meet The Creators

Michael and Hannie Clark are the creators of The Flower Letters.

Michael is a business entrepreneur who keeps everything organized and running properly for The Flower Letters. He also contributes to the creation of the storylines and makes it possible for Hannie to have the time necessary to write and create the art for the letters.

Hannie is a 5x published author. Three of those books are children’s books that she has also illustrated. She sells original 3D floral art over at @hannieclarkcreative .

The Clarks live in Utah, USA and have been married for 17 years. They have two fantastic kiddies that are involved wholeheartedly in this Flower Letters adventure that they're on.

Tag and follow us on social @the.flower.letters

SHOP NOW

Use left/right arrows to navigate the slideshow or swipe left/right if using a mobile device

Stories Told Through Letters |The Audrey Rose Letters – The Flower Letters

Skip to contentCongrats! Your first two letters are on us. Your discount will be auto-applied at checkout. 🤩

Congrats! Get a FREE Collection Tin with the purchase of any pre-paid story collection. Your discount will be auto-applied at checkout. You must add both the Story Collection and Tin to cart. 🤩

THE STORY

Experience

OUR PROMISE

Audrey Rose Drollinger meets Corporal Charlie Henderson Burke at a Fourth of July Army Ranger dance in Tullahoma, Tennessee. From the moment he lays eyes on her, Charlie knows he’s a goner. He has to meet Audrey Rose…to share a dance, a moment, a true connection before leaving for basic training – and soon, the war raging on the other side of the world.

From the moment he lays eyes on her, Charlie knows he’s a goner. He has to meet Audrey Rose…to share a dance, a moment, a true connection before leaving for basic training – and soon, the war raging on the other side of the world.

When the music ends that night, their story is just beginning, as the two soon learn they have a great deal in common: a love for their country, loyalty to the army, and, of course, an immediate attraction to one another.

As their relationship develops through heartfelt letters, the couple moves closer and closer to one of the most important days of WWII. Neither can yet see is the significant role each will play in the day’s events… and whether both of them will make it out alive – or even together.

Sign up

When you sign up for our one-year monthly subscription, you’re subscribing to a unique twelve-month immersive experience! Each of our letter collections comes with 24 beautifully illustrated letters. These letters are the personal correspondence between the characters of our story.

Receive 2 letters per month

Subscribers will receive two letters a month for twelve months, mailed on the 2nd and 4th weeks of the month. Each letter has been thoroughly researched, and thoughtfully designed by hand. Some letters are richly illustrated, while others might be a series of authentically designed telegrams. You may even receive a fact-filled newspaper clipping or a treasure map along the way. The possibilities are endless. We think half the fun is not knowing what’s coming next!

Enjoy the story

Most importantly, our subscribers will receive one thrilling story filled with History, Mystery, Adventure, and Romance with every collection of the Flower Letters they subscribe to. And yes, you can even subscribe to more than one collection at a time!

Get creative with your postcards

Once a month, subscribers will also receive a beautifully illustrated postcard featuring that collection's signature flower. We wanted to do something to encourage our subscribers to keep the dying art of letter writing alive. Use your postcard to send love notes to your own dear ones. Or don’t! Keep them as mini art prints if you like. We’ll never know. ;-)

We wanted to do something to encourage our subscribers to keep the dying art of letter writing alive. Use your postcard to send love notes to your own dear ones. Or don’t! Keep them as mini art prints if you like. We’ll never know. ;-)

Money-Back Guarantee

As the creators of The Flower Letters and writers of our stories, we stand behind our work and want you to have an enjoyable experience with The Flower Letters. This is a new and exciting way to experience a story, and we have thousands of satisfied customers all over the world. First and foremost this should be a source of joy for you and anyone experiencing this for the first time. If you are not happy with your experience after the first two letters, we will issue you a full refund no questions asked.

Guaranteed Delivery

Additionally, this is designed to be a cohesive story experience. Getting every letter in order is important to us! Therefore, if a letter is missed, lost, stolen, or tattered just email us and we will happily resend the letter at no additional cost to you.

30,000+ happy customers and counting

See Why Customers Love their Letters

Audrey Rose Letters

“ I am in love. They are very well written, so well decorated and they come with little details and props to immerse you even more in their world. ”

Reyiel

shop this now >

Audrey Rose Letters

“ I LOVE this collection and the entire idea behind The Flower Letters. I cannot recommend this enough. ”

Kimberly W.

shop this now >

Audrey Rose Letters

“ Not only do you get two letters every month but you will also receive things like old fashioned postcards and telegrams too! ”

Samantha Davis

shop this now >

Complete Your CollectionFrequently Asked Questions

Are these stories true? Are these real letters between real people?

No. While our stories center around eras and historical events, the characters and story lines are fictional. Any similarities are coincidental. Check our Learn sections regularly - we'll share background and insights into the inspiration for our stories and characters.

Any similarities are coincidental. Check our Learn sections regularly - we'll share background and insights into the inspiration for our stories and characters.

I am ordering this as a gift for someone that doesn't have internet access - can they still fully participate in The Flower Letters?

Yes! We do provide some additional content online in our Learn section, but access to the internet is not required to participate in The Flower Letters.

I haven't subscribed yet? Am I too late?

No - you're not too late! Our model supports subscribers any time during the year. When you subscribe we'll start sending you the story you subscribe to and continue for 12 months until the story is finished. You will get the whole experience!

How long does it take for my letter to arrive?

We use USPS First Class mail and mail on the dates found here. Mail times vary but can take up to 1 week for US letters and4 to 6 weeks to for international arrival.

Do you mail internationally?

Yes! We currently mail to 35 different countries!

Loved Worldwide

What customers have been saying!

scroll to top

Use left/right arrows to navigate the slideshow or swipe left/right if using a mobile device

History of communication development. Mail / Habr

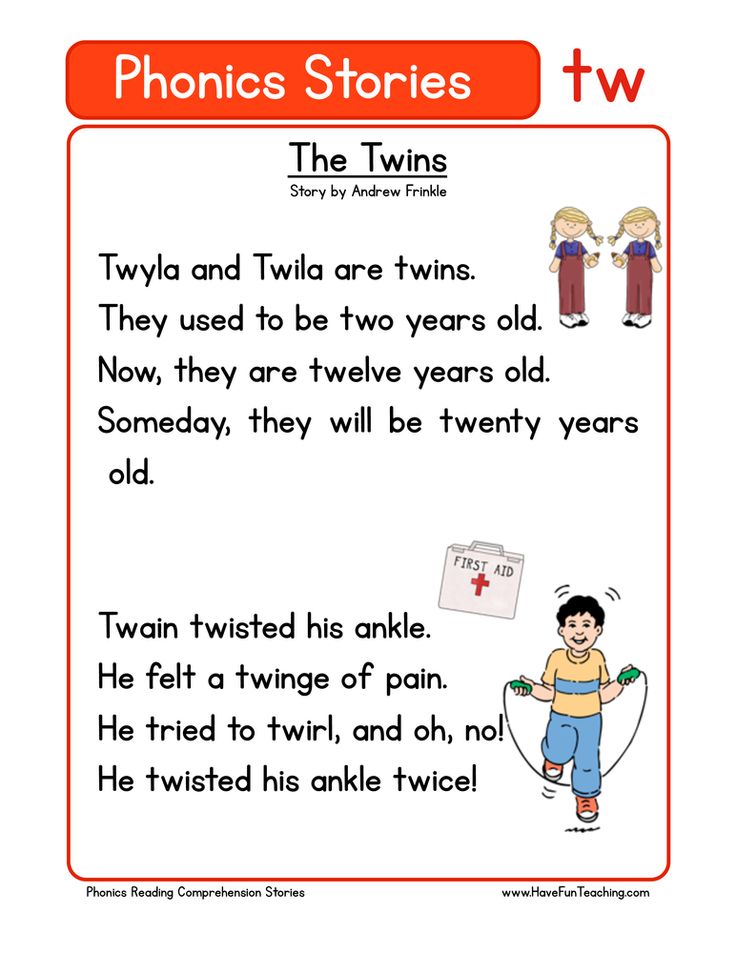

It's no secret that world history is closely connected with the exchange of information - without this process, the existence of human society is simply impossible. A key role in such an exchange is played by communication, that is, the transmission and reception of information using various technical means. In very ancient times, people did not have multi-core smartphones, so they used more primitive means: voice, sounds, fire, smoke, and the like.

Over time, the means and forms of communication changed - those who are smarter invented writing a little later and began to transmit information in writing. Since then, information has been transmitted in a more long-lasting form and especially intensively, and its first transfer can be safely considered the birthday of mail.

Since then, information has been transmitted in a more long-lasting form and especially intensively, and its first transfer can be safely considered the birthday of mail.

| By the way, the word "mail" comes from the Polish "poczta" and the Italian "posta". The latter, in turn, arose from "posta" and the late Latin "posita", which is most likely an abbreviation for "statio posita in ..." - a stop, a station for variable horses, located in a certain place. Thus, originally this word meant a station for the exchange of mail horses or couriers. The word "post" in the meaning of "mail" was first used in the XIII century. |

Today, the word "Post" means both the post office (post office, branch), and the message, and the totality of received correspondence (letters, parcels).

The most interesting museum expositions about mail were, perhaps, in the Museum of Communications. A.S. Popov in St. Petersburg and in the Postal Museum in Ufa (near the zero kilometer).

Petersburg and in the Postal Museum in Ufa (near the zero kilometer).

It's me, the postman Pechkin, who brought a parcel for your boy

Historians are of the opinion that the Russians adopted the device of the postal service from the conquerors - the Mongols. Then postal stations appeared on the main roads (at a distance of 30 to 100 miles from each other) - "pits" on which "yamchi" (messengers) changed horses. In turn, the words "yam" and "yamchi" come from two Tatar words - "dzyam" (road) and "yam-chi" (guide). From here came the word "coachman", which was called people involved in the transportation of people and goods on horse-drawn vehicles. Driver, not gonii horses ...

The work of the messengers was worn out (and were subjected to harsh punishments in case of dishonest performance of duties or failure to deliver the package), so they tried to recruit stronger people into their ranks. For example, the first parcel from Ufa to Moscow (via Kazan) in 1639 took the horse messenger Grishka Pogorelsky as much as 70 days (perhaps because he had outdated maps in the navigator). Try to ride a horse for 70 days ... but this is only in one direction.

Try to ride a horse for 70 days ... but this is only in one direction.

Model of a postal station of the 17th-18th century

The word "postman" (by the way, also a borrowed word) in pre-revolutionary Russia in the postal business began to be used from 1716, and before that, employees who delivered mail were called "postmen". At the same time, there were variations depending on the type of mail delivered: postmen delivered non-resident mail, and letter carriers delivered city letters.

Seriously with his reforms, the mail was pumped by Peter I - it was during his reign that the postal service in Russia appeared in all the main cities of the country. The post office became state, the first post offices in Russia were created, post offices were opened in provincial cities, and the position of postmaster was introduced.

At the same time, a new uniform for postal employees was introduced: a dark green cloth caftan with a departmental emblem - a postal horn (to announce his arrival) and a red eagle (the coat of arms meant that the postal worker was a government employee and was under guardianship and protection of big brother). Later, an under-arc bell was used to give a sound signal.

Later, an under-arc bell was used to give a sound signal.

By the end of the 18th century, the length of postal routes in Russia amounted to no less than 33 thousand miles (here they suggest that this is 35204.4 kilometers).

By the way, since we're talking about transport, we can't help but mention the railway. The first mail cars (between St. Petersburg and Moscow) began to run in 1851.

Covers and stamps

As now, as before, free cheese was only in mousetraps and cheeseburgers pierced like hamburgers. To put it simply, mail forwarding was not a free pleasure.

Letters at that time were written on paper, which was then folded with the text inside. Outside, on the clean side, the address was indicated, and the place of addition was often sealed with sealing wax. Then the letter was taken to the post office, where the employee (after weighing the item and receiving money for its forwarding) put an imprint of a special stamp. The resulting piece was called "cover" (presumably from the English "to cover" - to close) and was the prototype of modern envelopes.

The resulting piece was called "cover" (presumably from the English "to cover" - to close) and was the prototype of modern envelopes.

A stamp is a printing device used at the post office to obtain (manually or mechanically) stamp impressions that are used to cancel postage marks, confirm receipt of a postal item, control the route and time spent on the road, and also apply any - or notes.

Well, this is also the name of the print itself, which in itself carries quite a lot of different information (depending on color, shape, content, purpose, and so on).

This is interesting: it is believed that the stamp was invented by the royal mail farmer Henry Bishop, who was appointed in 1660 the first postmaster general of the United Kingdom. Initially, the invention was intended to control the time of mail passing, and the print contained only information about the month and day of delivery of the letter. And since they still did not know how to make stamps with a changeable date, the set for postal stations consisted of 366 stamps. |

The volumes of transfers were constantly growing, and soon this imperfect method of payment became very expensive, especially for the employees of the service. Therefore, in order to streamline the system of postage in 1845, the postal department carried out a number of reforms, among which was the introduction (first in St. Petersburg, and then in Moscow) of the first signs of postage. This is how stamped envelopes appeared - the same envelopes, but with a stamp already printed in a typographical way on the front side. Initially, they circulated only within the city, but already in 1848, variants of different denominations appeared, including for non-resident correspondence.

Since then, the appearance and design of the envelope have remained virtually unchanged.

Stamps

The stamp system was replaced by postage stamps - special signs, franking (a form of advance payment by the sender for the shipment and delivery of the shipment), which indicates the fact of payment for the services of the department (shipment and delivery of both domestic and international correspondence). Small and beautiful pieces of paper with a given value (face value) and a rich history.

Small and beautiful pieces of paper with a given value (face value) and a rich history.

My modest collection )

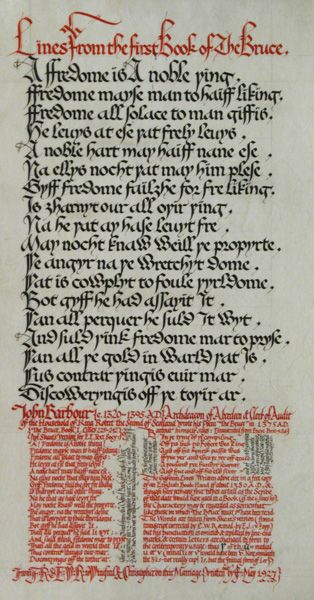

It is believed that their inventor in 1837 was the Englishman Rowland Hill, whose mother worked at the post office and repeatedly talked about the difficulties of work, the shortcomings of the postal system and the high cost of payment. To this, Hill once put forward the idea of a uniform postal rate (paid by the sender) in his pamphlet "Postal Reform, Its Significance and Expediency." It was there that the appearance of stamps was envisaged: “ Perhaps this difficulty (of using stamped envelopes in certain cases) might be obviated by using a bit of paper just large enough to bear the stamp and covered at the back with a glutinous wash, which the bringer might, by the application of a little moisture, attach to the back of the letter, so as to avoid the necessity of re-directing it "(" Perhaps this difficulty (of using stamped envelopes in certain cases) can be eliminated by using paper large enough to bear a stamp and covered on the back with a thin layer of adhesive that the sender can, with the help of a small moistening, attach on the back of the letter in order to avoid having to redirect it. ”). A little later, he became the author of the first stamp (“Black Penny”), but then it started…

”). A little later, he became the author of the first stamp (“Black Penny”), but then it started…

The world's first postage stamp

Stamps appeared in Russia a little later, in 1857 by A.P. Charulsky (an employee of the postal department) adopted foreign experience and proposed to introduce a stamp system in our cold regions.

The first drafts of Russian postage stamps (submitted by FM Kepler on October 21, 1856) were rejected by Charulsky. Later, the senior engraver of the EZGB Franz Mikhailovich Kepler joined the stamp project - after reading Charukovsky's feedback on the first samples, he began to make the first samples - one of several options was chosen, which became the first postage stamp in Russia. Beautiful? ;)

The first stamps had to be cut with scissors, although very soon they came to the conclusion that this was not the most convenient option. In 1847, Henry Archer, an employee of the Dublin Post Office, proposed perforating, that is, punching through round holes around the entire perimeter of the stamp. But few people know that postage stamps are perforated not only to facilitate the separation of stamps - the shape of the perforation and its dimensions are also one of the ways to protect against forgery.

But few people know that postage stamps are perforated not only to facilitate the separation of stamps - the shape of the perforation and its dimensions are also one of the ways to protect against forgery.

Mailboxes

The advent of stamped envelopes made it easier to pay for postage and made the presence of a postal official optional. All this contributed to the rapid emergence of mailboxes (for collecting and storing letters) right on the streets of the city.

There were a lot of options for the design of mailboxes at different times - both street, and "home", and vandal-resistant, and even with devices for issuing stamps - in many museums, as a rule, their entire collections.

War years

Civil letters are one thing, and the need to exchange information during hostilities, when mail was even more in demand, is quite another. The Great Patriotic War made itself felt - the movement of millions of people caused a huge increase in the flow of postal exchange, which is why the post office (as well as telegraphs, about which a little later) worked around the clock, processing thousands of parcels every day. To understand the scale - in the Bashkir Republic alone (Ufa was an important component of the postal system of those times), more than 20 million letters were processed, sent and delivered in a timely manner during the war years.

To understand the scale - in the Bashkir Republic alone (Ufa was an important component of the postal system of those times), more than 20 million letters were processed, sent and delivered in a timely manner during the war years.

A minute of entertaining arithmetic: the average speed of an LTE connection from Megafon in St. Petersburg was 50 megabits per second for reception. If we assume that all 20 million letters in the Bashkir Republic would have been written on A4 sheets during the war years (on both sides, that is, approximately 5000 characters per sheet), then the resulting volume of text (20.000.000 * 5 Kb = 95.367 GB) could have been downloaded in 4.5 hours. I would naively assume that the correspondence of the entire country could well be pumped out in a week ... so, what am I talking about.

An interesting fact: in the pre-margin period, letters were often written using the free space of the sheet both along and across. This was done in order to save paper and money to pay for one postal message.

|

By the way, letters and postcards addressed to the front were sent free of charge.

Our time

At the end of the last millennium, equipment and technologies began to develop especially intensively, mobile communications and the Internet appeared in Russia. The high level of penetration of these technologies has significantly affected the nature of communications between people: the flow of simple written correspondence continues to decline.

But the people of the country have practically lost nothing (except the joy of receiving a warm lamp letter) - after all, paper mail has been replaced by electronic mail. To transmit information, you don’t need to build a fire, start carrier pigeons ... and you don’t even need to know where the mailbox closest to your house is located - just get a phone / tablet / laptop anywhere in the city and be in touch. Any postal address, instant sending and receiving of letters, any file attachments, collective correspondence, forwarding, sorting - yes, yes, that's all. Being thousands of miles from the office, I was aware of what was happening at work.

Being thousands of miles from the office, I was aware of what was happening at work.

But once sending only in one direction would take more than one day ...

To be continued.

// Related links (Wikipedia): All about mail

You have just finished reading the first article about the history of communication development, all the rest will be published on the pages of a special project with MegaFon.

!important: The article does not claim to be complete and correct for all data.

Read online Postal History. From pigeon to electronic”, Mark Perov – LitRes

© Centerpolygraph, 2022

© Art design, Centerpolygraph, 2022

Foreword

Maybe the very concept of mail arose not so long ago by historical standards, but people always had to exchange information. And it’s good if you could come to a neighbor or relative and tell. What if he's far away? And if this is a military report or a weather warning? Yes, you never know what news needs to be conveyed. And the man began to come up with options - from screaming and knocking on a tree trunk to sending a faithful person with news. Then the messenger became a horse, and then all the achievements of technical progress began to be used to send mail. And now we can find out in the blink of an eye what is happening on the other side of the planet.

And the man began to come up with options - from screaming and knocking on a tree trunk to sending a faithful person with news. Then the messenger became a horse, and then all the achievements of technical progress began to be used to send mail. And now we can find out in the blink of an eye what is happening on the other side of the planet.

But the development of mail as a system of transmission of correspondence took hundreds of years, and for it man adapted many of his inventions. So from pigeon mail or signal smoke from campfires, we have come to deliver correspondence by drones and email.

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus once wrote: "Neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor the darkness of the night will keep the couriers from completing their predestined path as soon as possible." These words reflect the main task of the mail so correctly that they have become the unofficial motto of the United States Postal Service and are written on the pediment of the New York Post Office.

Today, the world's postal services process and deliver about 320.4 billion letters and 7.81 billion parcels per year. The international postal network has 5.26 million employees and 690.7 thousand postal institutions.

Postal history

It has millennia. As soon as people began to communicate outside the family and tribe, they needed some kind of medium to convey information. And they managed to come up with a lot of things.

How people communicated before writing

When scientists became interested in this question, they began to study the tribes living in the primitive system. And found out a lot of interesting things. First, the news can be simply told. If the information is urgent and important, then you can shout to be heard faster. And you can whistle. Whistling tongues are found in many parts of the world, especially in mountainous areas, since in the mountains, due to the acoustics, whistling is able to spread over long distances. These are not ordinary spoken languages, but invented to tell the news faster.

The whistling language of the Guanches, the indigenous inhabitants of the Canary Islands, is known. It has about 4 thousand words. In principle, the well-known Tyrolean folk songs “yodel” can also be attributed here. Historically, these were not songs, but a means of communication between shepherds in alpine meadows, so that there was no need to get to a neighboring pasture or village.

The first mention of whistling tongues is found in the "History" of Herodotus, which refers to the 5th century BC. e. “Their speech is unlike any other in the world: it resembles the squeak of bats,” he wrote about the cave dwellers of Ethiopia.

In Chinese texts of the 8th century AD. e. there is a description of a Taoist practice, the name of which can be translated as "Principles of whistling." It was believed that whistling poetry plunges a person into a meditative state. However, whistling was used not only for meditation. Whistling communities of the Hmong and Akha still exist in southern China.

As for the inhabitants of the Canary Islands, the first written mention of their whistling language (silbo gomero) dates back to 1402. Then the French explorer Jean de Betancourt went to conquer the Canary Islands, and in his team were two Franciscan priests who described the whole journey, including this unusual way of communicating with the Guanches. Then it was based on the language of the Gupnch themselves, which belonged to the Berber group, now the locals whistle phrases based on Spanish.

In the Americas, a Jesuit wrote about whistling tongues in 1755. He reported a whistling form of speech among the Aigua people in Paraguay: "They use a language that is difficult to learn because they whistle rather than talk."

There are such languages in parts of southern and eastern Africa.

Curiously, during the Second World War, the Australian Army hired native Papua New Guinean "Vam" speakers to whistle radio messages that Japanese eavesdroppers could not decipher.

As of 2018, there were about 70 whistled languages in the world.

On the Greek island of Euboea in the village of Antia, Sefirian is still spoken, the sound of which resembles bird sounds. Farmers and shepherds use it, but there are fewer and fewer such people. Local residents are doing their best to preserve their language - they organize classes, write to the local administration with a request to open a school and invite scientists to record the sound of the language.

In Mexico, the Sochiapanese Chinese and Mazatec are used for whistling. Interestingly, the inhabitants of Mexican communities use whistles to speak in the market, a situation that is unique to whistling languages, as they were created for long-distance conversations. Another surprising fact is that in Mexico only men communicate by whistling, although women usually understand what is being said.

In the north of Turkey, in the village of Kusköy, they speak the “language of birds”. He's been around for centuries. In 2017, along with silbo gomero, it was included in the UNESCO list of oral and intangible cultural heritage. Recently, it began to be studied at the elementary school and the Turkish University of Giresun at the Faculty of Tourism.

In 2017, along with silbo gomero, it was included in the UNESCO list of oral and intangible cultural heritage. Recently, it began to be studied at the elementary school and the Turkish University of Giresun at the Faculty of Tourism.

The Hmong people of the foothills of the Himalayas in Vietnam have their own version of a whistling language used by hunters and farmers. However, it has another popular use - the language of courtship. Although rarely practiced today, the whistling language of the Hmong was used by young people as a language of flirtation. The guys wandered around the villages, whistling poems to attract the attention of the girls. If the girls reciprocated, this could be the beginning of a relationship.

In addition to the voice, ancient people used improvised tools, the most famous of which was a hollow tree trunk. The sound from it carries over long distances. And later drums emerged from them. It is believed that this happened about 6 thousand years ago. For the same purposes, fires or smoke from them were used. Tom-tom drums are still used by African tribes to communicate over long distances, and the smoke from fires was used for the same purposes by the Indians of Canada back in the 20th century.

For the same purposes, fires or smoke from them were used. Tom-tom drums are still used by African tribes to communicate over long distances, and the smoke from fires was used for the same purposes by the Indians of Canada back in the 20th century.

The sounds of drums are varied in tone and duration, this allows you to convey messages with a certain meaning, and not just signal danger. In many villages in Africa, a meeting or the beginning of a ceremony is announced by the sounds of the conical okporo drum.

The body of the “talking drum” is shaped like an hourglass due to the narrow “waist” in the middle

louder or bassier. In Europe, no one thought of this.

Griots, West African wandering storytellers and musicians, are believed to have been the first to use this. They are known among the peoples of Hausa, Yoruba, Songhai, Wolof and others living in the modern states of Nigeria, Ghana, Benin, Niger, Togo. The performances of the griots included singing, dancing, and playing musical instruments.

The body of the talking drum is shaped like an hourglass due to the narrow "waist" in the middle. On both sides, the drum has a leather membrane, and the membranes are connected to each other by tension cords that run along the entire resonator body. The musician holds the drum under his arm and, pressing the cords with his shoulder and elbow, changes the tension of the membrane. The game is played with a single curved drumstick, and the resulting sounds have a clear difference in tone, these sounds are easily distinguished by pitch.

A drummer can not only play simple melodies on such a drum, but also do something like “bends”, that is, smoothly change the pitch of a “note” in the process of its sounding. This effect is also achieved by working with tension cords.

There is a similar drum in southern India, but the fact is that many West African languages are tonal, that is, the relative pitch with which a syllable is pronounced has a semantic difference. To memorize a word, one must not only learn the sequence of vowels and consonants, but also hear and be able to reproduce its tone. Speech in West African languages is a sequence of syllables "sung" at different pitches. In South India, the languages are completely different in this sense. The drum reproduces not a single word, but the tone pattern of the whole phrase. The listener just needs to know this phrase, and he will understand what is at stake. The appearance of "talking drums" and the style of playing them varied greatly from locality to locality and from ethnic group to ethnic group, but messages were transmitted with their help for thousands of kilometers.

Speech in West African languages is a sequence of syllables "sung" at different pitches. In South India, the languages are completely different in this sense. The drum reproduces not a single word, but the tone pattern of the whole phrase. The listener just needs to know this phrase, and he will understand what is at stake. The appearance of "talking drums" and the style of playing them varied greatly from locality to locality and from ethnic group to ethnic group, but messages were transmitted with their help for thousands of kilometers.

English missionary John Carrington, who lived and worked in the Belgian Congo from the late 1930s, not only learned the language of the local Kele people, but also mastered the translation of this two-tone language into the drum language. Returning to Europe, in 1949 he described his experiences in detail in a book called The Talking Drums of Africa.

As for signal fires, it is absolutely known that they were burned in ancient Greece, on the towers of the Great Wall of China, in Russia. The Indians of North America did the same. By giving puffs of smoke a certain color and shape, the Indians could transmit various information - warn of a military invasion, inform about the number of enemies and their location, and agree on help. To vary the density and color of the smoke, different raw materials were used - dry grass and thin brushwood created a translucent light curtain. To obtain dark and thick smoke, minerals, wet wood, animal bones, and fabric were used.

The Indians of North America did the same. By giving puffs of smoke a certain color and shape, the Indians could transmit various information - warn of a military invasion, inform about the number of enemies and their location, and agree on help. To vary the density and color of the smoke, different raw materials were used - dry grass and thin brushwood created a translucent light curtain. To obtain dark and thick smoke, minerals, wet wood, animal bones, and fabric were used.

In ancient times there were also rarer ways. Some did not reach us, and disappeared in the darkness of time, but some are known. For example, about the Chinese knot letter.

It is believed that this method arose even before the advent of hieroglyphs. The method of recording by tying knots on a rope is mentioned in the treatise "Tao Te Ching" ("The Book of the Way and Dignity"), written by the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu in the 6th-5th centuries BC. e. Cords connected to each other act as a carrier of information, and the knots and colors of the laces carry the information itself. Modern researchers put forward different theories. Some believe that the knots were supposed to save important historical events for posterity, others - that they were doing bookkeeping in this way.

Modern researchers put forward different theories. Some believe that the knots were supposed to save important historical events for posterity, others - that they were doing bookkeeping in this way.

On another continent, the Americas, knots were woven by representatives of the Inca civilization. They had their own nodular scripts "kipu", the device of which was similar to the Chinese nodular script. This counting system was used by the ancestors of the Incas. The message may contain a different number of hanging threads: from a few pieces to 2500. They were delivered by messengers "chaska" along specially laid imperial roads. Knots also recorded various aspects of social life: calendars, topographical information, taxes and laws, etc. It can be said that the entire Inca empire was ruled by means of a quipu.

Knots were tied in a certain way on multi-colored cords of various lengths. Depending on the color and place on the cord, their meaning differed. For example, in a kipu representing a military message, cords of different colors indicated the number of warriors armed with slings, spears, clubs, archers, etc. A simple knot denoted 10, a double knot denoted 100, and a triple knot denoted 1000 warriors. Special officials were instructed to weave and "read" the kippah.

A simple knot denoted 10, a double knot denoted 100, and a triple knot denoted 1000 warriors. Special officials were instructed to weave and "read" the kippah.

The oldest quipu known today consists of 12 hanging threads, some of which were knotted, and threads wrapped around sticks. It dates from around 3000 BC. e., in connection with which the kipu can be considered one of the most ancient types of writing among mankind after the Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs.

On the quipu, colorful cords of various lengths, knots were tied in a certain way

Europeans learned about the quipu in 1533 from the letter of the conquistador Hernando Pizarro. It says that “they [the Indians] counted by means of knots [tied] on several ropes” and that “the Indians have stores of firewood and corn, and everything else; and they [the Indians] count with the help of knots on their ropes what each cacique [chief] brought.”

The North American Indians called such records "wampum". These are cylindrical beads strung on cords from the shells of the species Busycotypus canaliculatus. These belts among the Algonquins and especially among the Iroquois could be both an adornment of clothes and money, and various important messages were transmitted with their help. Among the Iroquois tribes, such wampums were usually delivered by special messengers - wampumons. For a long time, treaties between whites and Indians were formalized exclusively through wampums. For example, a “written” treaty of alliance between Penn and the Quakers on the one hand and the Delawares on the other has survived. According to this treaty, the Delaware ceded to the Quakers a fairly large part of the territory of their tribe. This wampum depicts an Indian and a white symbolically holding hands.

These are cylindrical beads strung on cords from the shells of the species Busycotypus canaliculatus. These belts among the Algonquins and especially among the Iroquois could be both an adornment of clothes and money, and various important messages were transmitted with their help. Among the Iroquois tribes, such wampums were usually delivered by special messengers - wampumons. For a long time, treaties between whites and Indians were formalized exclusively through wampums. For example, a “written” treaty of alliance between Penn and the Quakers on the one hand and the Delawares on the other has survived. According to this treaty, the Delaware ceded to the Quakers a fairly large part of the territory of their tribe. This wampum depicts an Indian and a white symbolically holding hands.

In addition, the most important events in the history of the tribe were designated by the simplest conventional symbols on wampums. According to these "records", the old people, who knew the art of reading wampums, introduced new generations of warriors to tribal traditions. The name of the legendary Hiawatha (the creator of the most significant union of North American Indians - the Iroquois League) literally means "He who makes up the wampums." Soon after the appearance of white traders, the Indians stopped making wampums from simple shells and began to widely use glass beads brought to America from northern Bohemia.

The name of the legendary Hiawatha (the creator of the most significant union of North American Indians - the Iroquois League) literally means "He who makes up the wampums." Soon after the appearance of white traders, the Indians stopped making wampums from simple shells and began to widely use glass beads brought to America from northern Bohemia.

Knotted ropes were also among the Indians of Colombia and Panama, in Central America and Mexico, in the Amazon and even in Polynesia.

Mail in Antiquity

During the development of ancient states, mail was no longer carried by individual, sometimes randomly selected people, but by special messengers, first on foot, and then on horseback. In the ancient states of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Persia, China, the Roman Empire, there was a well-established state postal service.

It is believed that the first postal message appeared about 5000 years ago in Mesopotamia. Letters were then written on clay tablets, which were carried by messengers. Around the same time, the emergence of postal communications in Egypt.

Around the same time, the emergence of postal communications in Egypt.

Initially, it was a connection between military units or reports to the rulers of the country. Such were the messaging services in ancient Egypt, Assyria, Babylon and Persia. It is known that in Egypt during the IV dynasty of the pharaohs (2900-2700 BC) there was a service of special foot (walkers), as well as horse messengers, providing communication via military roads with Libya, Ethiopia and Arabia. Messengers were depicted even in wall paintings. It is known about professional messengers in Egypt in the era of the XII dynasty (1985-1785 BC BC), which carried the orders of the pharaohs all the way to Asia. Carrier pigeons were also used to transport letters.

The postal business in the Persian Monarchy is known under the name "Angareyon". Persia in its heyday included, in addition to the Persian lands proper, Asia Minor, Thrace, Macedonia, Babylonia, Egypt, Phenicia, Syria, Palestine, part of the Transcaucasus and Central Asia, Arabia and northwestern India.

The postal system was introduced in the 6th century BC. e. during the reign of Cyrus II (550–529years BC e.). Messages were delivered mainly by horse messengers (hangars). However, it is likely that a similar postal system existed in Persia much earlier. Historians Herodotus and Xenophon wrote that under Cyrus II, postal stations were installed on the most important roads, 20 kilometers apart, and between them there was also a division into parasangs (5 kilometers). These stations served as recreational couriers. At the end of the parasangs were pickets of couriers-riders.

Herodotus wrote about the road from Sardis to Susa, 450 parasangs (2500 km) long, which was divided into 111 stations. It was called royal and was the main route of the messengers, along which they carried the orders of the king and news for him from the Aegean coast of Asia Minor through Armenia and Assyria to the center of Mesopotamia to Susa. The same road of 80 parasangs supported communication between Susa and Babylon.

There were two branches from the royal road: to Tire and Sidon and to the borders of Bactria and India.

“In the darkness of the night, in cold and bad weather, another messenger mounted a horse and raced the message along its path ... Nothing in the world can argue with them in speed, pigeons and cranes can hardly keep up with them,” wrote the Greek historian Xenophon.

One of the capitals of Persia, the city of Susa, was more than 2.5 thousand kilometers away from the Mediterranean Sea. Horse messengers covered the entire distance in 5–6 days, while a foot messenger would need 9 days.0 days. Moreover, the letter was passed along the chain of messengers, like a baton.

The name of the postal service in Persia comes from the name of the messengers themselves - "angars" - they were horse couriers. The Persian word "khangar" means "royal courier", which may be derived from the Pahlavi (i.e. Parthian) "angird" - "horse messenger". Other scientists believe that the word "Angar" was formed from the Turkic ethnonym "Khangar-Kangar", which in ancient times was called the ancestors of the Pechenegs. Khangars served as couriers among the Persians, thanks to which the word "khangar" began to mean "courier" in the Persian language.

Khangars served as couriers among the Persians, thanks to which the word "khangar" began to mean "courier" in the Persian language.

An organization similar to angarion was preserved, according to Diodorus, by Alexander the Great and his successors. Subsequently, it served as a model for the introduction of state mail by Augustus in the Roman Empire.

In ancient Greece, the postal system was both land and sea. The problem was that Ancient Greece was not a single state. It consisted of city-states, policies that were either friends or at war with each other. Government mail was usually carried by messengers on foot. They were called hemerodromes ("day messengers"). Such messengers ran an average of 55 stages (about 10 km) per hour. There were also grammatophores ("letters").

Grammatophores delivered messages over short distances. Hemerodromes, armed with darts, were famous for their speed of running. The famous hemerodrom Euchis, sent after the battle of Salamis (480 BC) to Delphi for the sacred fire, ran almost 200 km in one day. More than once, hemerodromes have won victories by participating in the Olympic Games. Conversely, the winners of the games often became hemerodromes.

More than once, hemerodromes have won victories by participating in the Olympic Games. Conversely, the winners of the games often became hemerodromes.

The most famous of these couriers was Pheidippides, who, according to Plutarch, at 490 BC e. brought to Athens the news of the victory at the Battle of Marathon and died of exhaustion.

Riding messengers were sent already in antiquity to convey particularly hasty messages. And they used not only horses. As Diodorus Siculus writes, one of the commanders of Alexander the Great kept messengers at his headquarters - camel riders.

In Greece, the message was carried from beginning to end by one messenger. No one, under threat of death, dared to attack him, detain him or rob him. After all, he carried a letter of national importance. Often the messengers had distinctive signs by which they were immediately recognized. Even robbers and vagabonds were considered with these signs.

In ancient Rome, at first, only wealthy patricians, who owned numerous slaves, had their own messengers. These, as a sign of their profession, had sticks topped with goose wings. For government and private purposes, there were messengers and citizens who rented wagons and beasts of burden. They had their own boards. The foundations of state mail were laid by Gaius Julius Caesar, and the emperor Augustus developed the system. In those days, the mail was directly subordinate to the emperor; private messages could not be transmitted through it.

These, as a sign of their profession, had sticks topped with goose wings. For government and private purposes, there were messengers and citizens who rented wagons and beasts of burden. They had their own boards. The foundations of state mail were laid by Gaius Julius Caesar, and the emperor Augustus developed the system. In those days, the mail was directly subordinate to the emperor; private messages could not be transmitted through it.

Thanks to a single postal network, all parts of the vast empire were connected with each other. Until now, the famous Roman roads encircled a vast territory: modern England, all of Eastern Europe to the Rhine and to the Danube, the Balkans, Turkey, Syria, Palestine, Jordan, North Africa from Tangier to Alexandria with Egypt. And on all these roads messages were transported. From different parts of the vast empire, all roads led to Rome (hence the well-known saying). The roads converged at a majestic structure - a mile column, set in the middle of the forum at the foot of the temple of Saturn.

Postal transportation was carried out on land with the help of horses, by sea - on ships. Horse couriers were called "Veredaria" - they were the fastest couriers of Rome. Initially, the system consisted of couriers stationed along military roads and passing messages to each other. But since the couriers did not know the text, they could not provide any additional information about the brought event or decree. Therefore, after some time, interchangeable carts or horses were placed along the roads, which the courier changed while traveling from beginning to end. At the same time, carts and horses were forcibly rented from local residents, paying them money for this, and lodging for the night was not paid.

Roman Messenger

The locals were unhappy with the postal service, so a fee was set that the employees of the state post office had to pay to the peasants for the requisitioned horses. The number of horses that couriers could change at stations was also limited. Permits to use the mail were issued to provincial procurators, senators, equites, centurions, and others on imperial or military assignments.

Permits to use the mail were issued to provincial procurators, senators, equites, centurions, and others on imperial or military assignments.

Later, stations were established in large centers where riders and drivers could rest and spend the night. Usually they stood one from the other for a day's journey. There were mounted and pack animals and carts at the ready. Between each two such large stations, 6-8 smaller ones were arranged for changing horses. Even in the time of Julius Caesar, there was an extensive network of roads. Its length was 150,000 km. All the roads were lined with stone pillars indicating the distance in miles (a Roman mile equaled 1,500 m).

The Romans used to say: “Statio posita in…”, which means “a station located in such and such a place”. From the Latin word posita, it is likely that the word post came - "mail".

Urgent news was delivered by horse couriers, if the news was not urgent, then the messages were carried in light wagons, all sorts of things in carts. Sometimes whole military detachments were transported by state mail wagons. Traveling officials, especially veterans, and later priests, could use state mail only on the basis of special permits, which gave rise to various abuses.

Sometimes whole military detachments were transported by state mail wagons. Traveling officials, especially veterans, and later priests, could use state mail only on the basis of special permits, which gave rise to various abuses.

Gradually, the postal system began to be funded by the provinces. Another change was the allocation of the transport of heavy loads with the help of wagons pulled by oxen. This is believed to have taken place under Septimius Severus (193–211).

At first the praetorian prefect was the head of the Roman post office, and from the time of Constantine (306-337) the master of offices. The administration of the post in the provinces was carried out by governors, under whom special prefects were in charge of the technical part of the post. The surrounding population, both in Rome and in the conquered countries, had to supply horses, other means of transportation and riders.

Thanks to the excellent road network, security and order of communications, extensive correspondence between civil and military authorities, the vast expanses of the Roman Empire could be crossed fairly quickly. Caesar (63-44 BC), using interchangeable private horses, could travel 100 miles a day, and already the emperor Tiberius (14-37 AD) traveled 200 with the help of state mail. Of the most important provinces news was received in Rome daily. Stations along busier roads contained 20–40 draft horses and mules. This continued until the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Caesar (63-44 BC), using interchangeable private horses, could travel 100 miles a day, and already the emperor Tiberius (14-37 AD) traveled 200 with the help of state mail. Of the most important provinces news was received in Rome daily. Stations along busier roads contained 20–40 draft horses and mules. This continued until the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Riding and cargo horses, light two-wheeled wagons pulled by three mules, and heavy four-wheeled wagons pulled by eight mules in summer and ten in winter were used for fast transportation. Restrictions on the weight of goods were introduced: a rider could carry 30 libres (about 10 kg), a two-wheeled cart - 200 libres (about 60 kg), a four-wheeled cart - 1000 libres (about 300 kg).

Heavy transport used wagons (hangars) pulled by two pairs of oxen and carrying up to 1500 libres (about 500 kg).

For private mail, one had to use the services of traveling friends, so private correspondence could take an indefinite time to be delivered. The famous Roman orator Cicero said about this: “Although writing letters is an excellent way to talk and maintain relationships with friends living far away, but, unfortunately, there is no way to deliver these letters to their destination.” And the philosopher Seneca wrote to Luculus: “I received your letter many months after it was sent. I was therefore compelled to question the bearer of the letter in detail about your affairs ... ". But not only that! A case is known when a certain Augustin received a letter nine years later. Therefore, if the distance to the addressee was not too great, the Roman sent his slave, who traveled on foot up to 75 kilometers a day.

The famous Roman orator Cicero said about this: “Although writing letters is an excellent way to talk and maintain relationships with friends living far away, but, unfortunately, there is no way to deliver these letters to their destination.” And the philosopher Seneca wrote to Luculus: “I received your letter many months after it was sent. I was therefore compelled to question the bearer of the letter in detail about your affairs ... ". But not only that! A case is known when a certain Augustin received a letter nine years later. Therefore, if the distance to the addressee was not too great, the Roman sent his slave, who traveled on foot up to 75 kilometers a day.

Constantinople became the new capital of the Roman Empire in 330. At the same time, the distinction between stations for lodging for the night and for changing horses began to disappear. The stations were run by special people appointed by the local council. In some provinces, retired officials were obliged to manage them. According to the law of 381, these people served no more than 5 years and received the status of perfectissima for successful service. The position was unpopular due to high requirements (for example, it is forbidden to leave the post for more than 30 days) and costs.

According to the law of 381, these people served no more than 5 years and received the status of perfectissima for successful service. The position was unpopular due to high requirements (for example, it is forbidden to leave the post for more than 30 days) and costs.

There were up to 40 horses at the stations. The horses served for four years, since a quarter of them were replaced every year. Animal feed was provided from a provincial tax in kind. At the same time, the tabulars distributed horses at their discretion, without taking into account the travel time and the required number, which was corrected in 365. The weight of the goods carried was limited and it was forbidden to beat the horses with certain types of devices so that the horses would serve longer. The horses were looked after by grooms and veterinarians.

There were carpenters and blacksmiths at the stations who could repair passing wagons. These were hereditary public slaves who were supplied with food and clothing, but who were not given a salary.

The use of mail required a special permit, either for fast or heavy transport. Such permits were formally issued only for government purposes, but powerful people often obtained them for their own personal purposes. A permit was required for each trip: it indicated the route, the validity period and the number of animals that were allowed to change at the stations. It was forbidden to demand more from the station staff than specified in the permit, and to use draft animals that did not belong to the stations: if there was no free one, travelers should wait for it to appear, and not demand it from the nearest peasant. Emperor Constantine in his laws threatened arrest and other punishments for such demands.

Local landowners could sell grain for gold at the station and pay them taxes, so the closure of the state postal system was a great loss for them.

In the 4th-6th centuries, carts were replaced by camel riders. The unified transport system of the empire disappeared, fast transportation of goods was canceled. After the system closed, officials could use their own animals, organize together, or use private carriers.

After the system closed, officials could use their own animals, organize together, or use private carriers.

In China, the service of foot and horse messengers was founded during the Zhou Dynasty (1123-249years BC e.). It is known that 80 messengers and 8 main couriers were in the public service, for whom quarters for food were arranged at a distance of 5 kilometers, and accommodation points for the night at distances of about a day's journey. This postal system was later expanded.

India has had a postal service since antiquity. The Indian epic "Ramayana" (4th century AD) mentions road guards, who supervised the messengers who fled from station to station. By ringing bells, they demanded to give way, and also announced their arrival. On the belt of the messenger there was a metal plate with his name, number and station designation. Stations were huts where messengers passed messages to each other. For crossing the rivers, the messengers had swimming belts.

Messengers in different countries could have special identification marks so that others knew that a person was traveling on a state business. In Japan, the messengers held bells in their hands. Even princely processions had to give way to them. The messengers of Genghis Khan, who traveled huge distances from Europe to the ruler's headquarters, tied a sign - "paizu" to their foreheads. Depending on the importance of the messenger and the message, the tablets were wooden, silver or gold with the image of a falcon or a tiger.

In Japan, the messengers held bells in their hands. Even princely processions had to give way to them. The messengers of Genghis Khan, who traveled huge distances from Europe to the ruler's headquarters, tied a sign - "paizu" to their foreheads. Depending on the importance of the messenger and the message, the tablets were wooden, silver or gold with the image of a falcon or a tiger.

The Inca postal couriers were called "chasques"

It is known that the Maya also had a developed service of messengers, but there are no details about it. The Incas had mail in Peru and the Aztecs in Mexico. Here, long before the arrival of Europeans, there were postal messengers. Inca Garcilaso de la Vega tells about the mail of the Incas in his book "History of the State of the Incas", published in 1609 in Lisbon. Garcilaso de la Vega was born in 1539 in present-day Peru and was the son of an Inca princess and a captain of the conquistadors. In 1560 he left for Spain, where he became known as a writer.