Syllable blending activities

Blending and Segmenting Games | Classroom Strategies

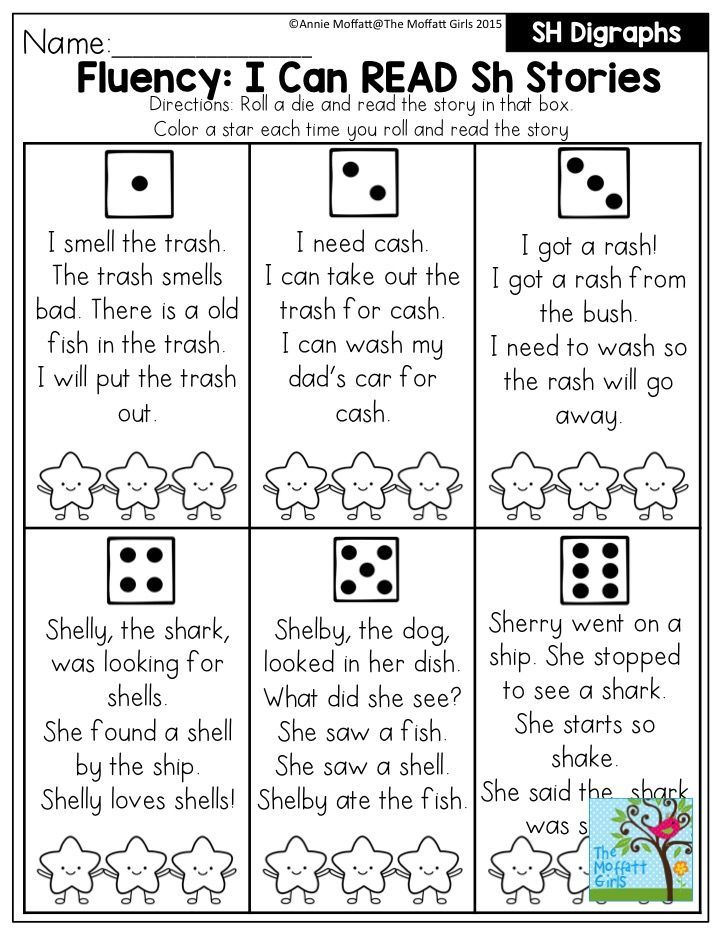

Children who can segment and blend sounds easily are able to use this knowledge when reading and spelling. Segmenting and blending individual sounds can be difficult at the beginning. Our recommendation is to begin with segmenting and blending syllables. Once familiar with that, students will be prepared for instruction and practice with individual sounds.

| How to use: | Individually | With small groups | Whole class setting |

What are blending and segmenting?

Blending (putting sounds together) and segmenting (pulling sounds apart) are skills that are necessary for learning to read and spell. When students understand that spoken words can be broken up into individual sounds (phonemes) and that letters can be used to represent those sounds, they have the insight necessary to read and write in an alphabetic language. Blending and segmenting games and activities can help students to develop phonemic awareness, a strong predictor of reading achievement.

Why teach blending and segmenting?

- Teaching students to identify and manipulate the sounds in words (phonemic awareness) helps build the foundation for phonics instruction.

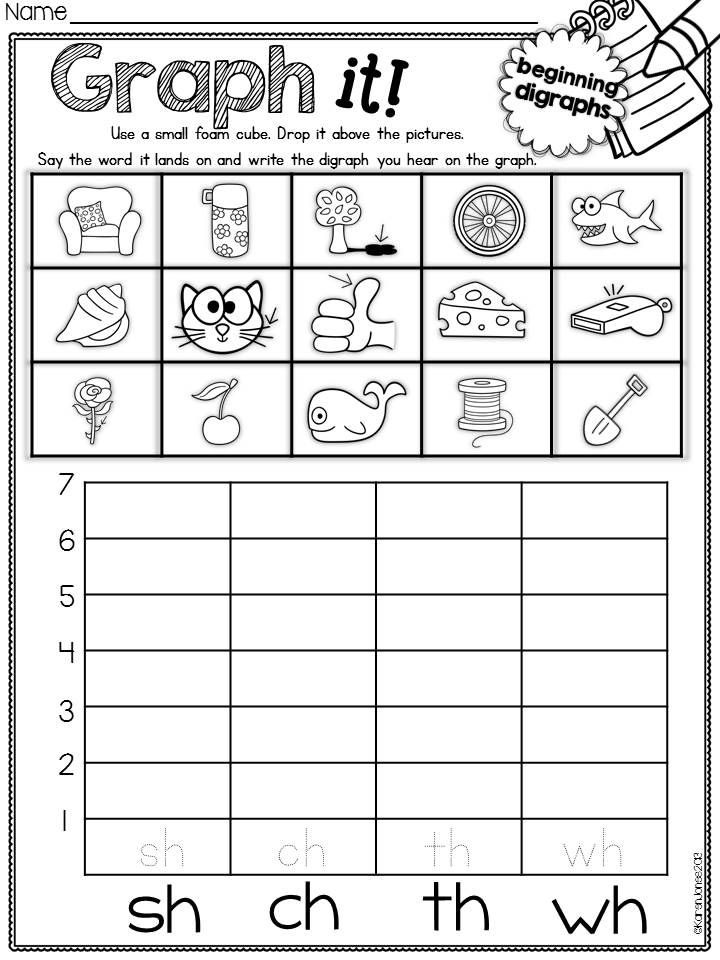

- Blending and segmenting activities and games can help students to develop phonological and phonemic awareness.

- Developing phonemic awareness is especially important for students identified as being at risk for reading difficulty.

How to teach blending and segmenting

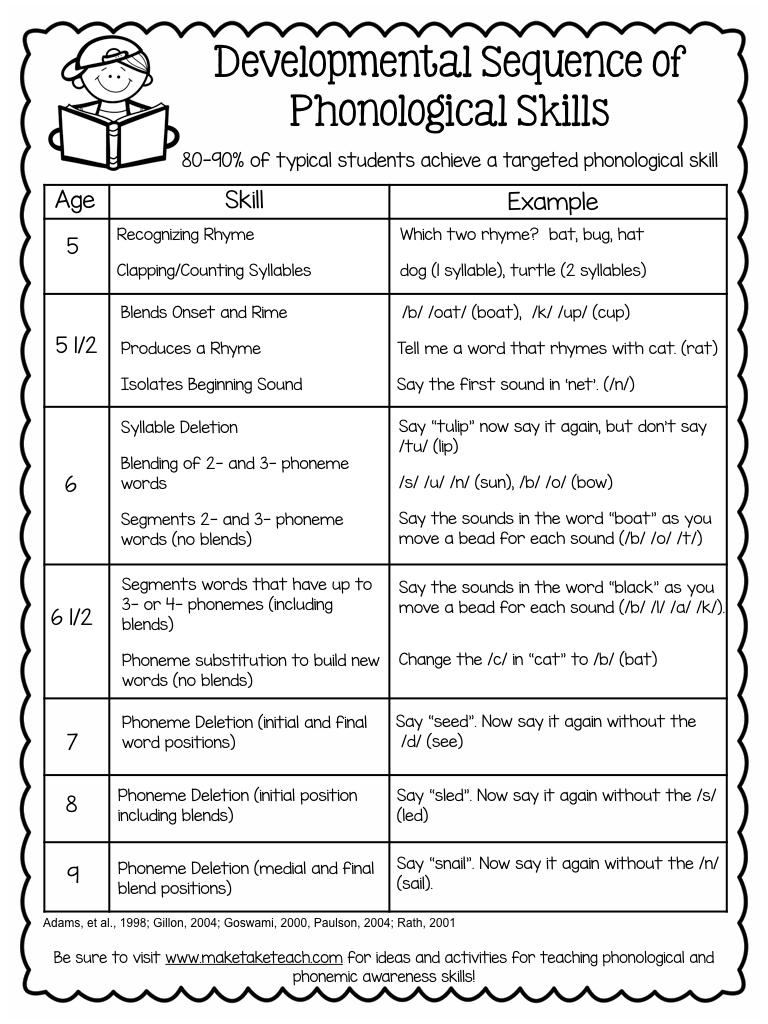

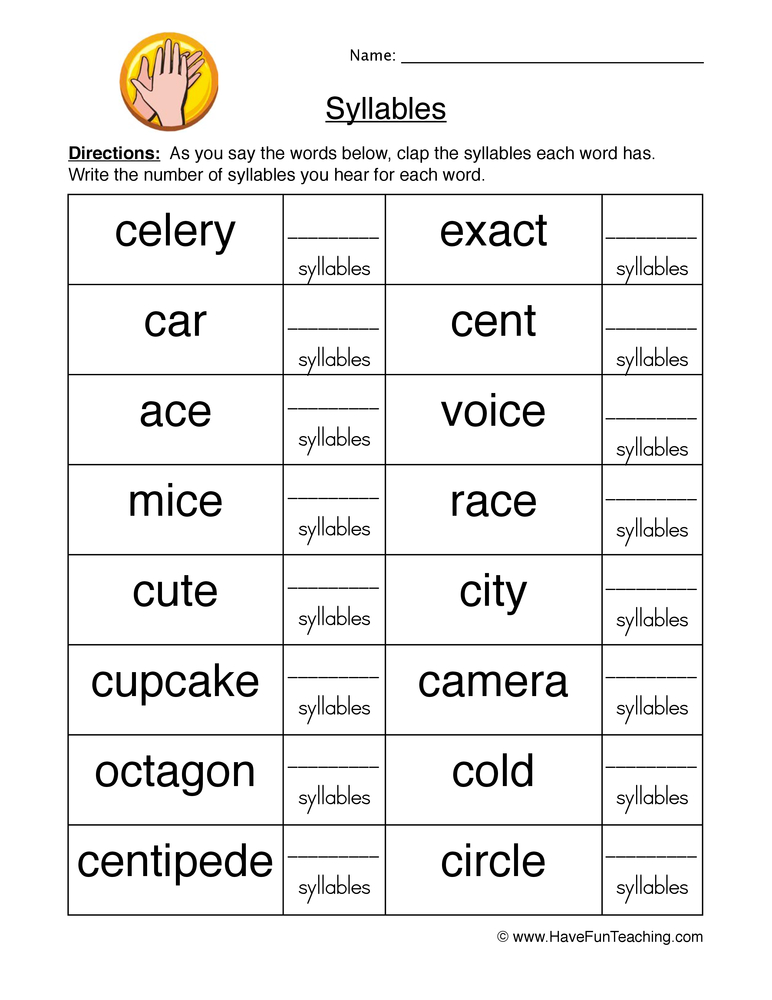

Segmenting and blending — especially segmenting and blending phonemes (the individual sounds within words) — can be difficult at first because spoken language comes out in a continuous stream, not in a series of discrete bits. Beginning with larger units of speech can help.

Early in phonological awareness instruction, teach children to segment sentences into individual words. Identify familiar short poems such as "I scream you scream we all scream for ice cream!" Have children clap their hands with each word.

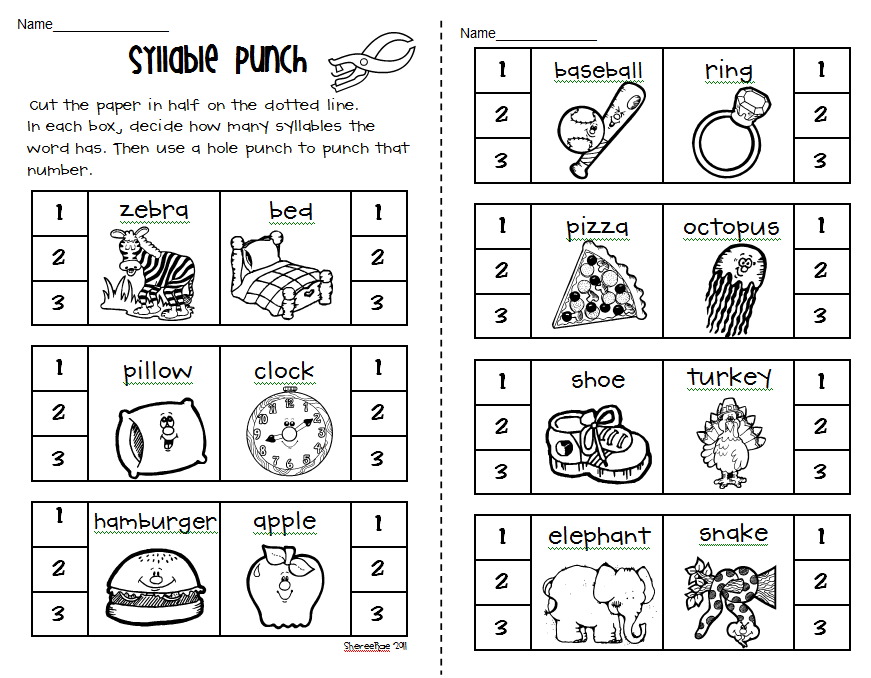

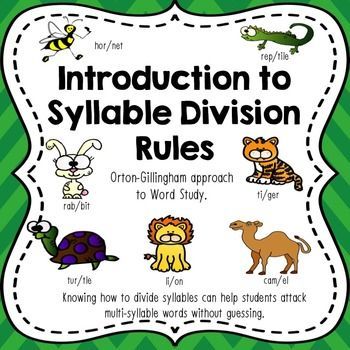

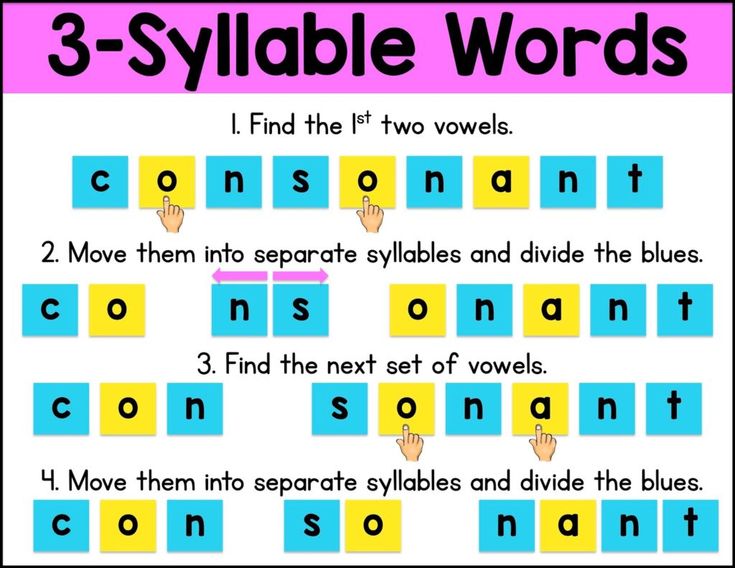

As children advance in their ability to manipulate oral language, teach them to segment words into syllables. For example, have children segment their names into syllables: e.g., Ra-chel, Al-ex-an-der, and Rod-ney. Likewise, have them blend syllables to make words.

Once in kindergarten, the focus of blending and segmenting instruction should shift to the phoneme level. This work can be challenging for students, so it can be useful to know which scaffolds can help students make the leap.

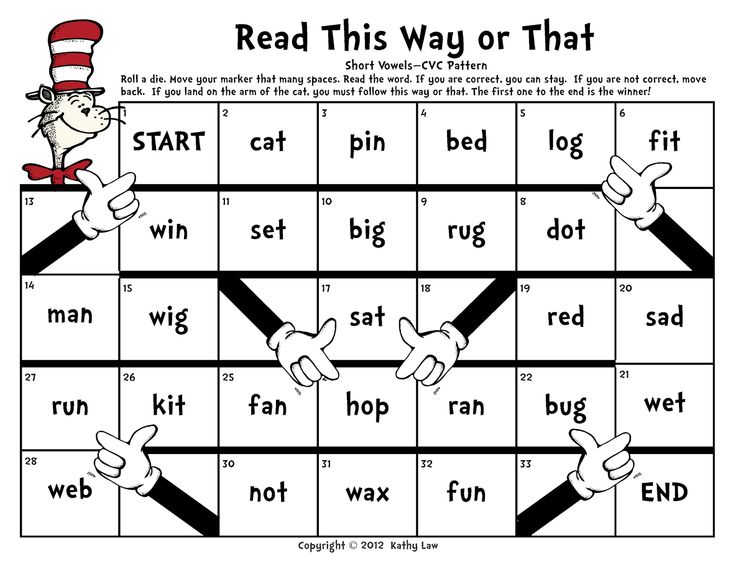

- Start with words that have only two phonemes (for example, am, no, in)

- Begin with continuous sounds (phonemes that can be held for a beat or two without distorting the sound). Have students practice blending and segmenting words with continuous sounds by holding the sounds using a method called “continuous blending” or “continuous phonation.” (e.g., “aaaammmm ... am”)

- Then, introduce a few stop sounds (phonemes that cannot be held continuously).

Ensure that students articulate the sounds cleanly, without adding an “uh” to the ends of sounds such as /t/ and /b/. Stop sound at the end of words (eg. at, up) are easier to blend than those that have stop sounds at the beginning (for example, be, go)

Ensure that students articulate the sounds cleanly, without adding an “uh” to the ends of sounds such as /t/ and /b/. Stop sound at the end of words (eg. at, up) are easier to blend than those that have stop sounds at the beginning (for example, be, go) - As students are ready, progress to words with three phonemes, keeping in mind that words beginning with continuous phonemes (for example, sun) are easier to blend and segment than those with stop sounds (for example, top).

- As students become more skilled at blending and segmenting, they may no longer need to hold sounds continuously, transitioning from “ssssuuunnn” to sun.

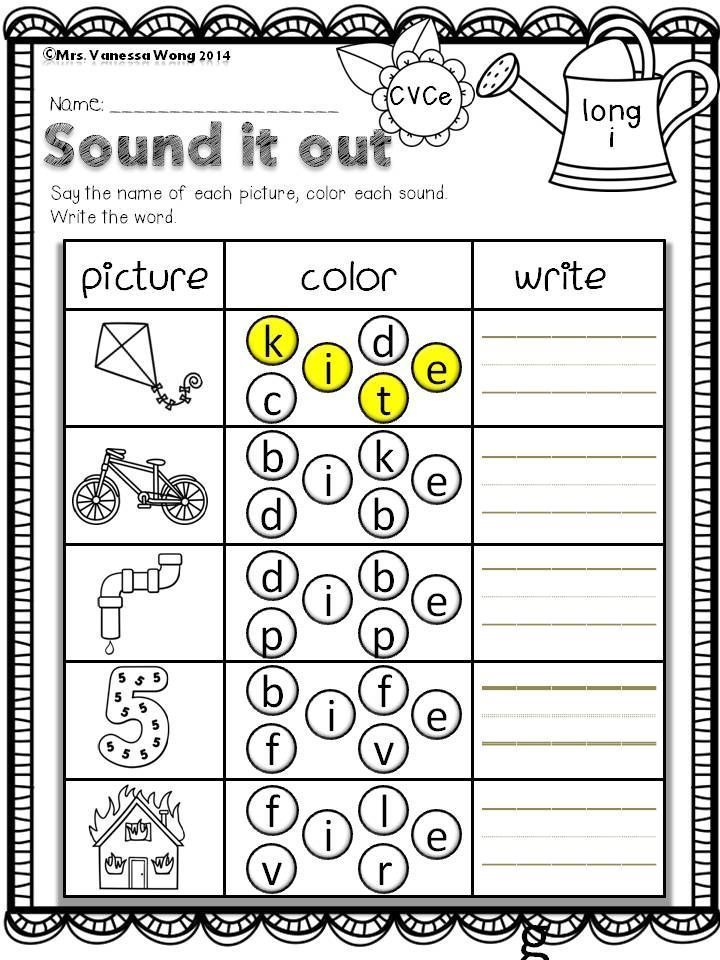

It can be helpful to anchor the sounds students are working with to visual scaffolds. Elkonin boxes, manipulatives (such as coins or tiles), and hand motions are popular supports. It’s important to remember, however, that the goal of blending and segmenting games is literacy and there is no better visual representation for a phoneme than a letter.

Collect resources

Blending: guess-the-word game

This activity, from our article Phonological Awareness: Instructional and Assessment Guidelines, is an example of how to teach students to blend and identify a word that is stretched out into its basic sound elements.

Objective: Students will be able to blend and identify a word that is stretched out into its component sounds.

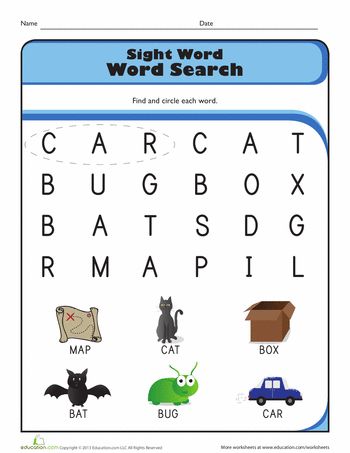

Materials needed: Picture cards of objects that students are likely to recognize such as: sun, bell, fan, flag, snake, tree, book, cup, clock, plane

Activity: Place a small number of picture cards in front of children. Tell them you are going to say a word using "Snail Talk" a slow way of saying words (e.g., /fffffllllaaaag/). They have to look at the pictures and guess the word you are saying. It is important to have the children guess the answer in their head so that everyone gets an opportunity to try it. Alternate between having one child identify the word and having all children say the word aloud in chorus to keep children engaged.

Talking in "Robot Talk," students hear segmented sounds and put them together (blend them) into words. See robot talk activity ›

See all Blending/Segmenting Activities from the University of Virginia PALS program

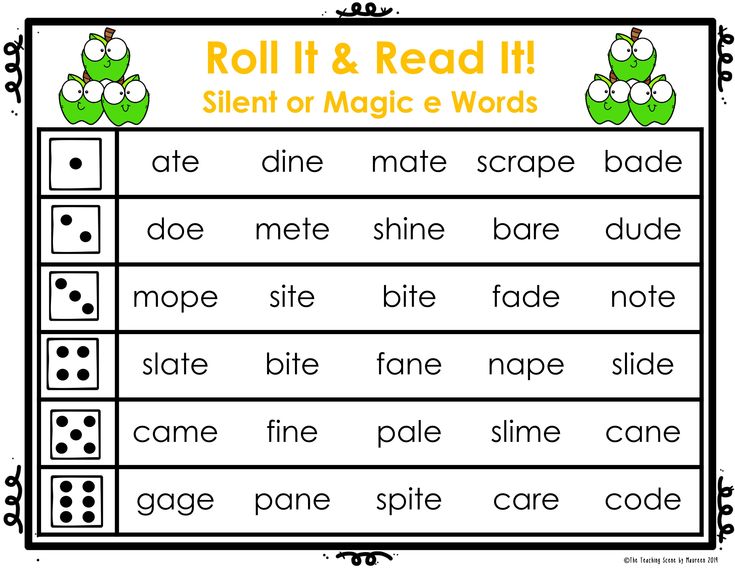

Blending slide

The "Reading Genie" offers teachers a simple way to teach students about blends. Teachers can use a picture or small replica of a playground slide and have the sounds "slide" together to form a word. See blending slide activity ›

Oral blending activity

The information here describes the importance of teaching blending skills to young children. This link provides suggestions for oral sound blending activities to help students practice and develop smooth blending skills. See oral blending activities ›

Sound blending using songs

This activity (see Yopp, M., 1992) is to the tune of "If You're Happy and You Know It, Clap Your Hands."

If you think you know this word, shout it out!

If you think you know this word, shout it out!

If you think you know this word,

Then tell me what you've heard,

If you think you know this word, shout it out!

After singing, the teacher says a segmented word such as /k/ /a/ /t/ and students provide the blended word "cat. "

"

Segmenting cheer activity

This link provides teachers with information on how to conduct the following segmentation cheer activity. See segmenting cheer activity ›

Write the "Segmentation Cheer" on chart paper, and teach it to children. Each time you say the cheer, change the words in the third line. Have children segment the word sound by sound. Begin with words that have three phonemes, such as ten, rat, cat, dog, soap, read, and fish.

Segmentation Cheer

Listen to my cheer.

Then shout the sounds you hear.

Sun! Sun! Sun!

Let's take apart the word sun.

Give me the beginning sound. (Children respond with /s/.)

Give me the middle sound. (Children respond with /u/.)

Give me the ending sound. (Children respond with /n/.)

That's right!

/s/ /u/ /n/-Sun! Sun! Sun!

Segmenting with puppets

Teachers can use the activity found on this website to help teach students about segmenting sounds. The activity includes the use of a puppet and downloadable picture cards. See segmenting with puppets activity ›

The activity includes the use of a puppet and downloadable picture cards. See segmenting with puppets activity ›

Differentiate instruction

For English-learners, readers of different ability levels, or students needing extra support:

- Incorporate print into blending and segmenting the individual sounds in words with students who know the spelling-sound correspondences in the words.

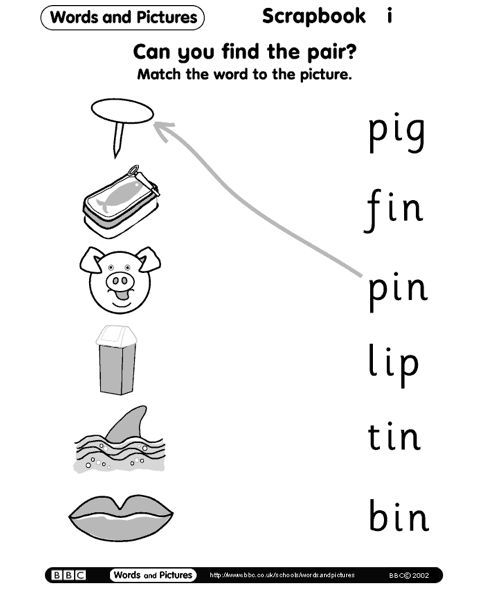

- Use picture-centered activities to support English-learners and younger students.

Related strategies

Find more activities for building phonological and phonemic awareness in our Reading 101 Guide for Parents.

See the research that supports this strategy

Chard, D., & Dickson, S. (1999). Phonological Awareness: Instructional and Assessment Guidelines.

Clemens, N., Solari, E., Kearns, D. M., Fien, H., Nelson, N. J., Stelega, M., Burns, M., St. Martin, K. & Hoeft, F. (2021, December 14). They Say You Can Do Phonemic Awareness Instruction “In the Dark”, But Should You? A Critical Evaluation of the Trend Toward Advanced Phonemic Awareness Training.

Fox, B., & Routh, D.K. (1976). Phonemic analysis and synthesis as word-attack skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 68, 70-74.

Gonzalez-Frey, S. & Ehri, L.C. (2021) Connected Phonation Is More Effective than Segmented Phonation for Teaching Beginning Readers to Decode Unfamiliar Words. Scientific Studies of Reading, 25:3, 272-285.

Sensenbaugh. (1996). ABCs of Phonemic Awareness.

Smith, S.B., Simmons, D.C., & Kameenui, E.J. (February, 1995). Synthesis of research on phonological awareness: Principles and implications for reading acquisition. (Technical Report no. 21, National Center to Improve the Tools of Education). Eugene: University of Oregon.

Yopp, H. K. (1992). Developing phonemic awareness in young children. The Reading Teacher, 45 , 696-703.

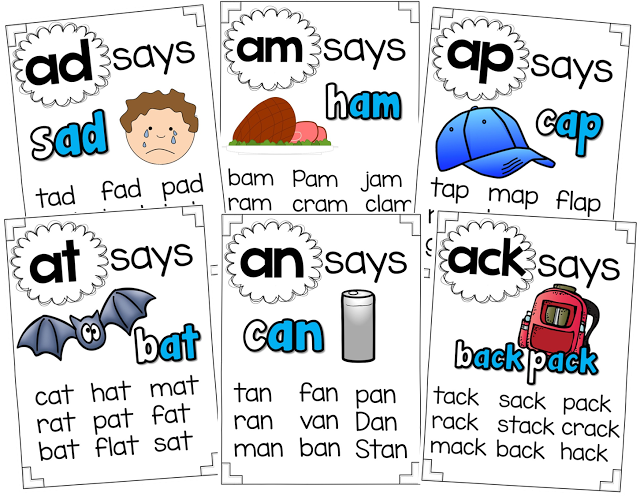

Onset-Rime Games | Classroom Strategies

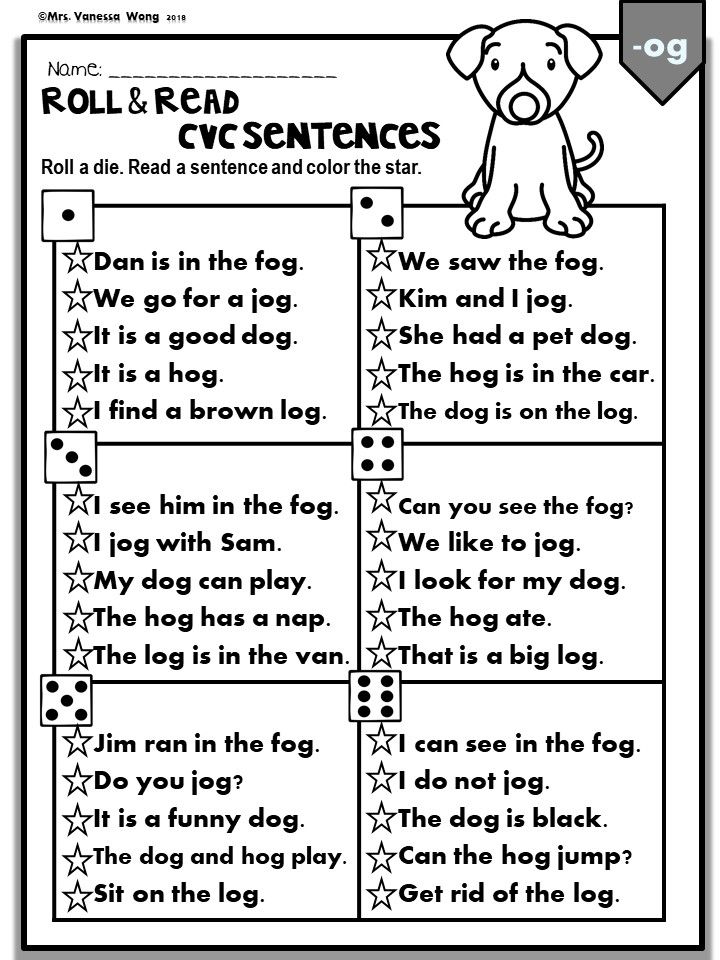

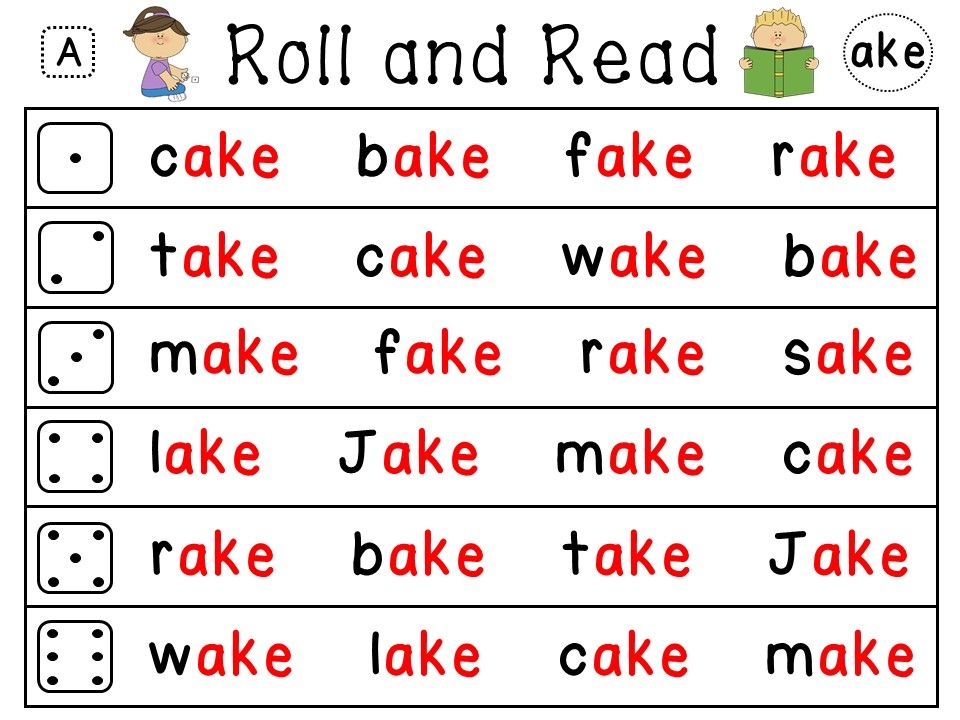

The “onset” is the initial phonological unit of any word (e.g. /c/ in cat) and the term “rime” refers to the string of letters that follow, usually a vowel and final consonants (e. g. /a/ /t/ in cat). Not all words have onsets. Similar to teaching beginning readers about rhyme, teaching children about onset and rime helps them recognize common chunks within words. This can help students decode new words when reading and spell words when writing.

g. /a/ /t/ in cat). Not all words have onsets. Similar to teaching beginning readers about rhyme, teaching children about onset and rime helps them recognize common chunks within words. This can help students decode new words when reading and spell words when writing.

| How to use: | Individually | With small groups | Whole class setting |

More phonological awareness strategies

Why teach about onset-rime?

- They help children learn about word families, which can lay the foundation for future spelling strategies

- Teaching children to attend to onset and rime will have a positive effect on their literacy skills

- Learning these components of phonological awareness is strongly predictive of reading and spelling acquisition

Whiteboard: explaining onset-rime

This video explains the phonological awareness skill onset-rime and shows examples. (From the What Works Clearinghouse practice guide: Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade. )

)

Make a word: using onsets and rimes

Students blend onsets with rimes and listen to see if the blend is a word. See the lesson plan.

This video is published with permission from the Balanced Literacy Diet. See related how-to videos with lesson plans in the Phonemic Awareness section as well as the Letter-Sounds and Phonics section.

Collect resources

From the Florida Center for Reading Research, download and print these activities:

These articles offer suggestions for how to use simple onset and rime activities to help students develop phonological awareness.

Construct-a-word: "ig" in Pig. The link below outlines a strategy that can be adapted to teach different onset and rime word patterns. This activity helps teachers isolate and teach the rime "ig" using the book If you Give a Pig a Pancake by Laura Numeroff. There is an instructional plan that accompanies the activity and extension ideas included to advance the learning process. See example >

Download blank templates

See the link below for more help building word families using onset and rimes.

Differentiated instruction

for second language learners, students of varying reading skill, and for younger learners

- Have students create and write word sorts of the target word pattern

- Use pictures instead of words in activities for younger and lower level readers

See the research that supports this strategy

Bear, D., Invernizzi, M., Templeton, S., & Johnston, F. (1996). Words their way: Word study for phonics, vocabulary, and spelling instruction. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Chard, D., & Dickson, S. (1999). Phonological Awareness: Instructional and Assessment Guidelines.

Ellis, E. (1997). How Now Brown Cow: Phoneme Awareness Activities.

Goswami, U., & Mead, F. (1992). Onset and rime awareness and analogies in reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 2, 153-162.

Wise, B. W., Olson, R. K., & Treiman, R. (1990). Subsyllabic units as aids in beginning readers word learning Onset-rime versus post-vowel segmentation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 4, 1-19.

Children's books to use with this strategy

Clang! Clang! Beep! Beep! Listen to the City

By: Robert Burleigh

Genre: Fiction

Age Level: 6-9

Reading Level: Independent Reader

Rhyming couplets describe city sounds with illustrations embedding the onomatopoeic sounds.

Cha Cha Chimps

By: Julia Durango

Genre: Fiction

Age Level: 3-6

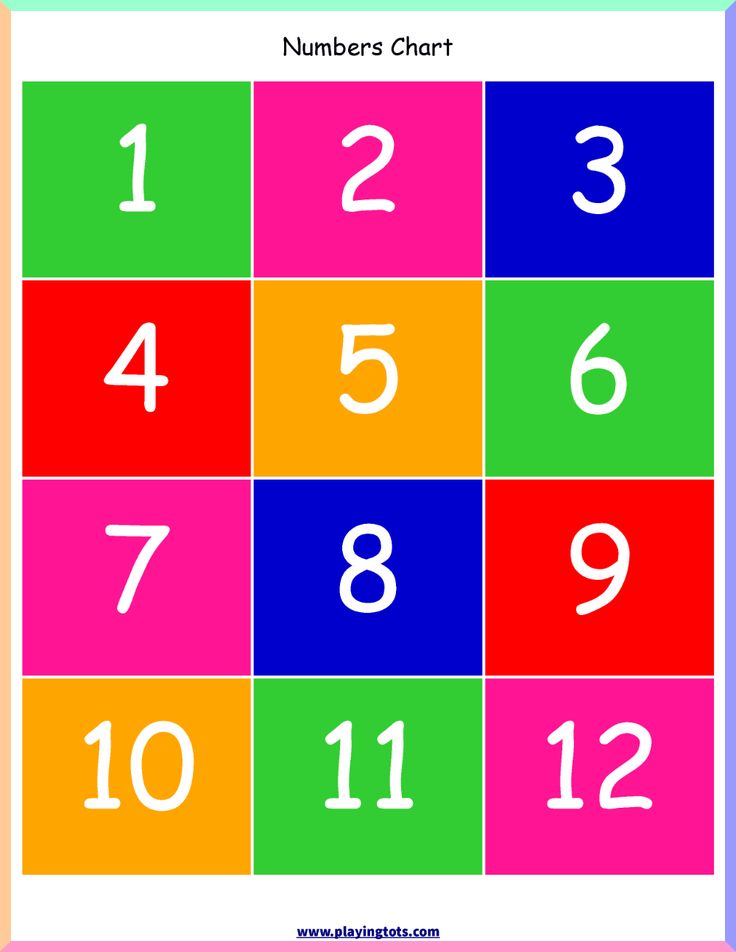

Reading Level: Beginning Reader

Chimps from one to ten counting sneak out to dance their rhyming way around and through this very funny counting book.

Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?

By: Bill Martin Jr

Age Level: 3-6

Reading Level: Beginning Reader

This title needs no introduction nor do its spin-offs like Baby Bear Baby Bear, What Do You See?, Panda Bear Panda Bear, What Do You See? or Polar Bear Polar Bear, What Do You Hear?

A Huge Hog Is a Big Pig

By: Francis McCall, Patricia Keeler

Genre: Nonfiction

Age Level: 3-6

Reading Level: Beginning Reader

This rhyming words game is illustrated with crisp photographs and is sure to tickle the imagination as another rhyming description is sought. For more experienced readers (grade 2-3), try Eight Ate: A Feast of Homonym Riddles by Marvin Terban — just what the title indicates.

To Market, To Market

By: Nikki McClure

Genre: Fiction

Age Level: 6-9

Reading Level: Independent Reader

A child and his mother go to a farmers' market to get fresh produce and goods. On alternating pages, the person responsible for growing each kind of food is introduced, bringing to light many unknown jobs as well as food sources. The bold linear illustrations are created by handsome paper cut-outs.

On alternating pages, the person responsible for growing each kind of food is introduced, bringing to light many unknown jobs as well as food sources. The bold linear illustrations are created by handsome paper cut-outs.

Time for Bed

By: Mem Fox

Genre: Fiction

Age Level: 0-3

Reading Level: Pre-Reader

It's bedtime for an ewe and her lamb, a cow and her calf and for a mother and her child. Watercolor illustrations show mothers and their babies settling in for the night.

Comments

Syllabic schemes for the prevention and correction of dysgraphia

Inability to master writing skills - dysgraphia - is quite common in children with speech disorders. Specialists distinguish several types of dysgraphia. Some of them are not very common, others are quite widespread. In particular, dysgraphia, based on difficulties in distinguishing phonemes and impaired phonemic analysis and synthesis.

The occurrence of these forms of dysgraphia is based on the speech problems that children have. They manifest themselves in the mixing of letters and syllables in writing, omissions and replacement of letters, "loss" of vowels. If you do not do the correction in time, "by itself" this problem will not go anywhere. The fact is that such errors are characteristic of children with impaired perception of order and phonemic hearing.

Is it possible to prevent dysgraphia?

Some parents whose children have some kind of speech impairment are pre-set for difficulties with schooling. Others, on the contrary, are unaware of such a connection between oral and written speech, and as a result, they face a disastrous result already in elementary school.

Experts say that it is in the prevention of dysgraphia that there is a great sense. it’s easier to teach a child to perceive sounds, syllables and words correctly in advance than to correct mistakes later. However, even with the discovery of dysgraphia, you should not give up.

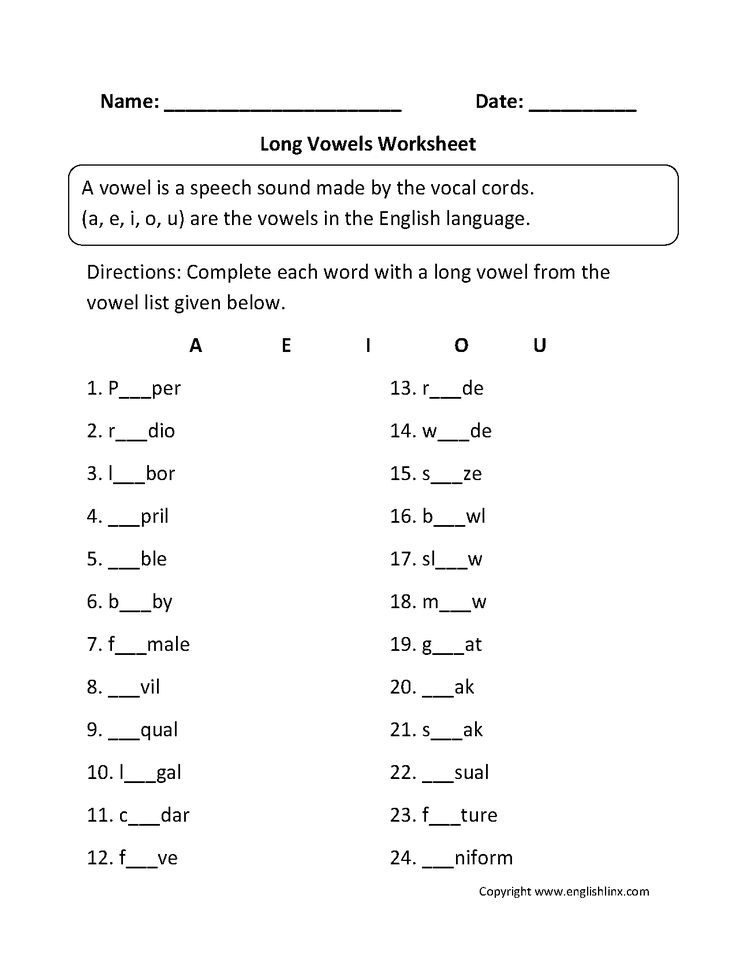

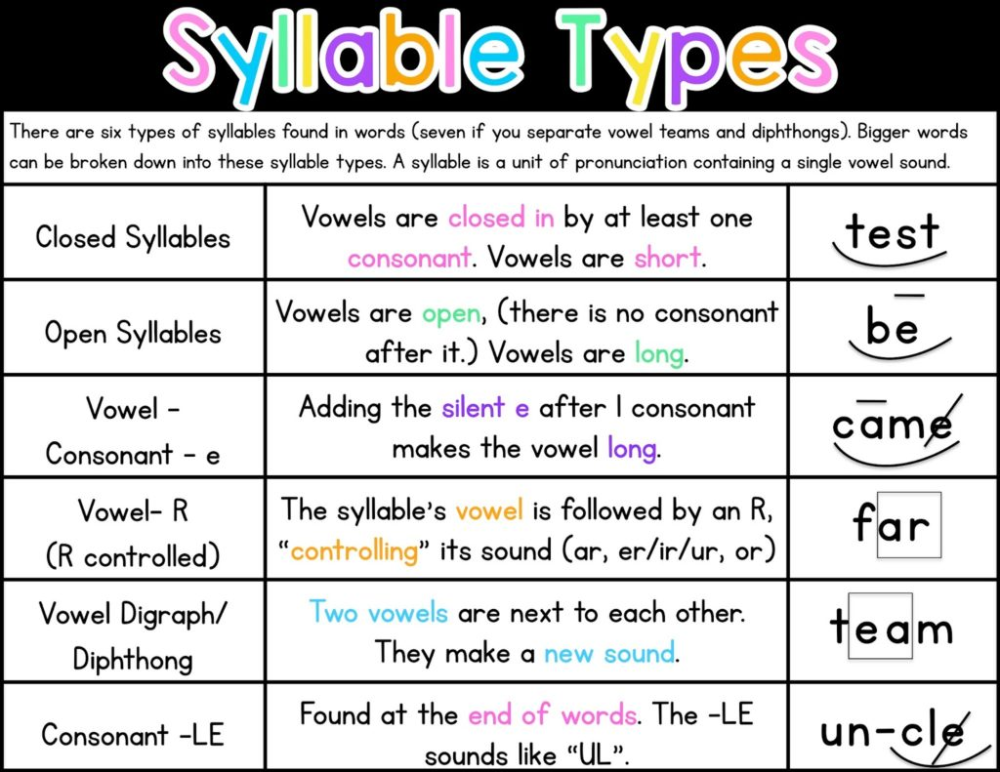

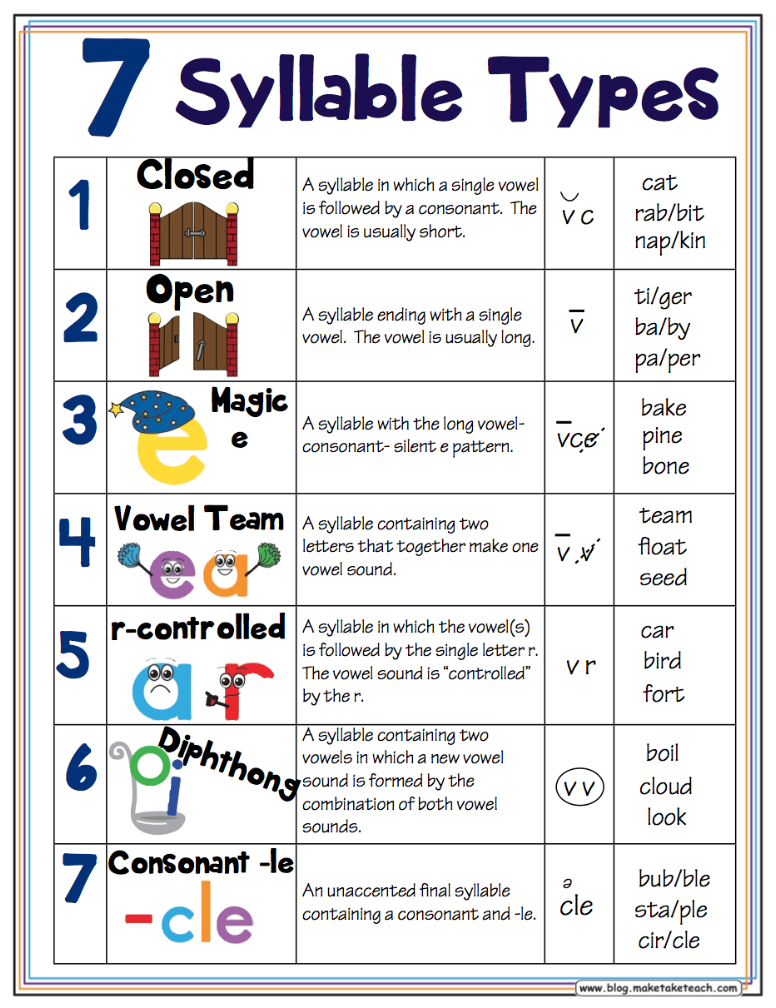

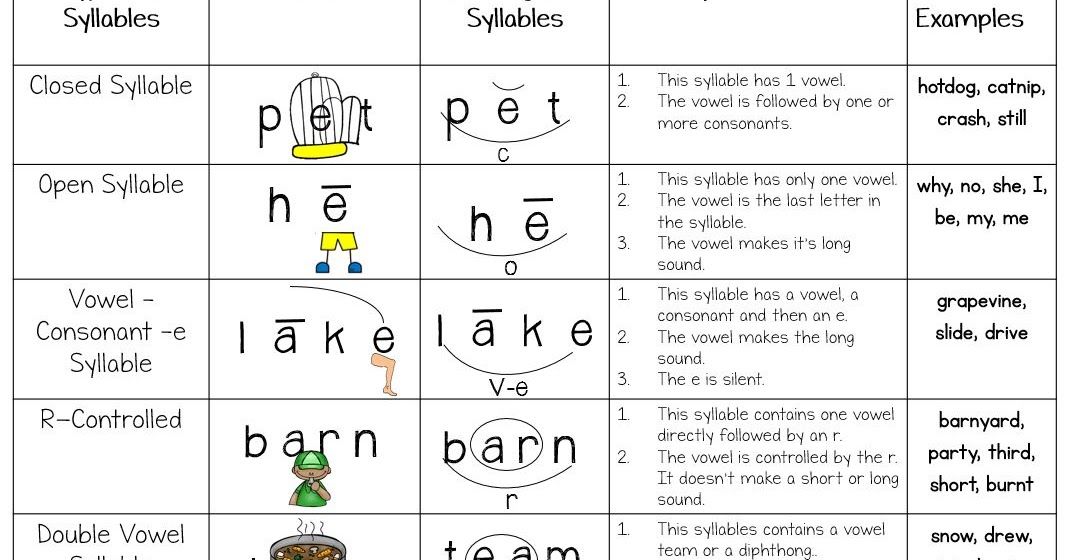

Difficulties with writing text, omitting or mixing letters in writing arise due to the fact that the child does not perceive the phonemes in the composition of the word by ear. Theory comes to the rescue. Spelling training is based on phonetics, confident mastering the skill of sound-letter analysis. However, first the child must master the concepts of “syllable”, “vowel and consonant sound”, “stressed and unstressed” well. It is on this that corrective work is being carried out with potential and obvious dysgraphics.

Read also: Development of syllabic analysis and synthesis skills

What is a syllable-alphabetic word scheme

As part of correctional work, exercises with syllable-letter word schemes are widely used. Such a gradual and visual analysis helps children deal with all the difficulties and minimize possible dysgraphic errors.

- The word the child is working with must first be divided into syllables. To do this, each syllable is first “slammed” with hands.

You can invite the child to play the conductor - to make a hand movement in the air for each syllable.

You can invite the child to play the conductor - to make a hand movement in the air for each syllable. - Now this part of the work is transferred to paper. By the number of syllables in the notebook, the required number of arcs or horizontal lines is displayed. At the beginning of the work, teachers suggest drawing arcs that more clearly indicate the division of a word into syllables.

- The next stage is the isolation of the syllable-forming sound. We pronounce each syllable slowly out loud. You need to put dots indicating the number of letters in each syllable. Then we “look for” a vowel. The child identifies the sound and names the letter that stands for it. It must be written above the corresponding line or arc.

- Next, the stressed syllable is determined and the stress mark is placed over the desired vowel.

- The next "move" is drawing up a diagram in the form of several squares according to the number of sounds. Vowels are indicated in red, consonants in green (soft sound) or blue (hard).

How to work with syllable-letter schemes

The main principle of work is gradualness. You can not move on to the next step until the child has fully mastered the previous ones.

- "Recognition" of vowels and consonants. Type exercises - raise the red circle if you hear a vowel, blue if you hear a consonant.

- Determining the place of a phoneme in a word. Tasks with word cards. The child must place the circle representing the vowel sound in the corresponding box. Arrange the cards in columns according to the model: a vowel at the beginning of a word, in the middle, at the end.

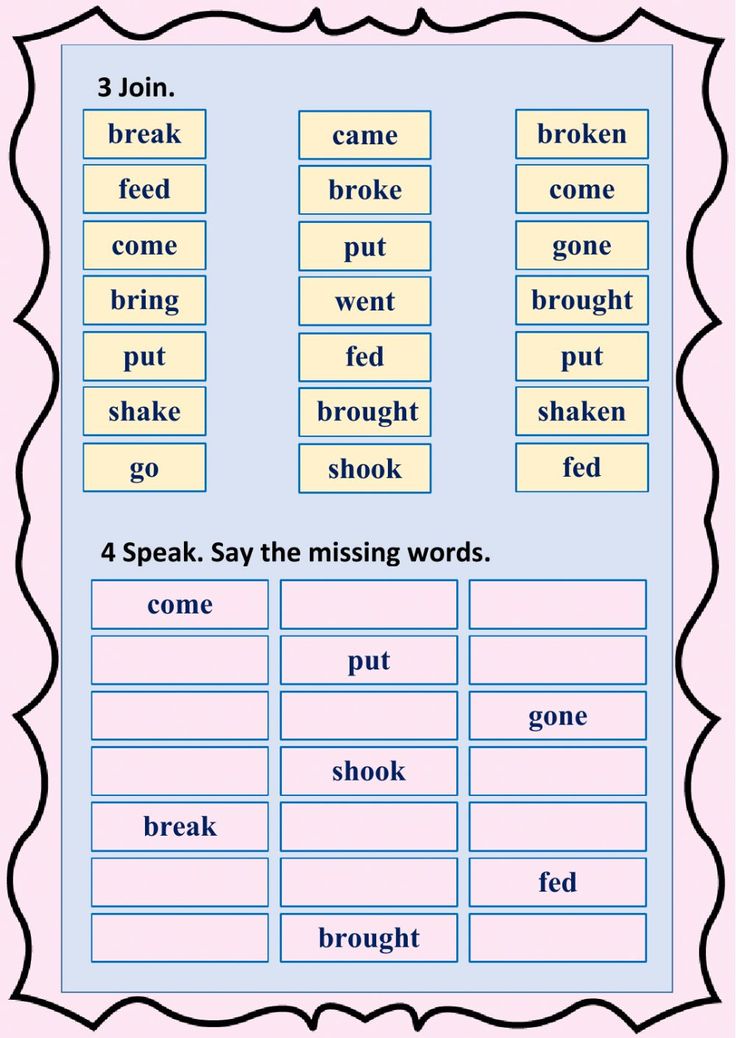

Drawing up a syllable-alphabetic scheme of words:

- one-syllable words are used first, then two- and three-syllable ones;

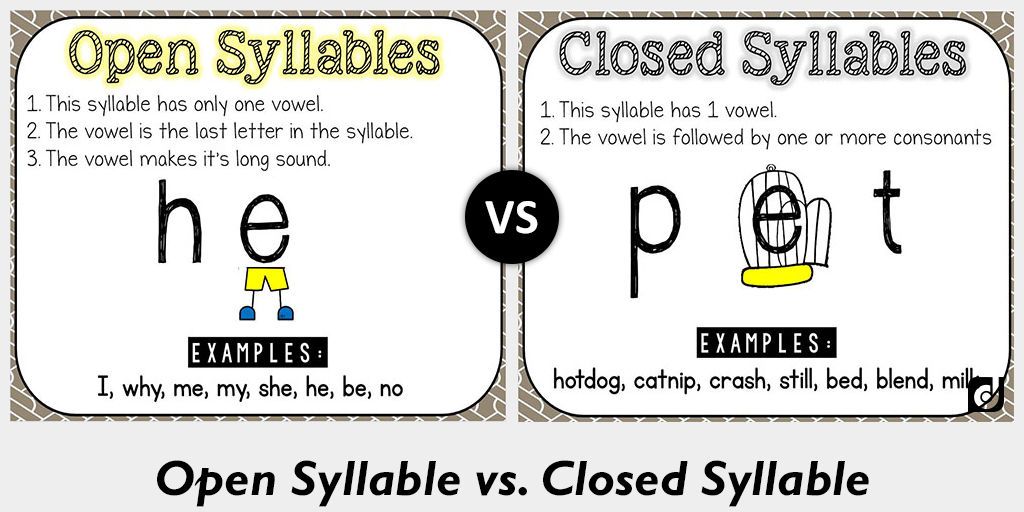

- at the beginning of work, only open syllables are taken for tasks;

- the word is spelled the way it is heard;

- Gradually, the types of syllables and sounds become more complex - one-syllable words with a confluence of consonants are introduced, then two-syllable words of a different sound structure.

The exercises are not limited to mechanical charting. To consolidate the material and maintain motivation and interest in children, different types of tasks should be offered:

- choose a word for the scheme proposed by the teacher;

- spell the word into the diagram;

- pick up a word (pictures) with vowels corresponding to the pattern;

- "find" the first syllable in the pictures laid out in a certain order, write down the syllables. Make a word out of them;

- draw up a word diagram and mark only vowels in it;

- mark in the scheme only a soft (hard) consonant;

- isolate from the dictation and write down in the notebook only those words that fit the drawn diagram.

Such exercises help children to visually see what sounds are in the word, what letters they stand for. As a result, this will positively affect the literacy of the letter. At the initial stages, all work should be based on visual stimuli and pronunciation of sounds and syllables. However, as the material is mastered, the “supports” must be gradually removed. It is the mental analysis and synthesis of the word that should become the goal of the work.

However, as the material is mastered, the “supports” must be gradually removed. It is the mental analysis and synthesis of the word that should become the goal of the work.

Read also: Modern ways to automate sounds

Having learned the rules of the relationship between the perception of a word by ear and its sound-letter designation, the child will learn to write correctly. Based on these skills, you can already move on to working out the writing of proposals.

Publication date: 10/15/2017. Last modified: 07/15/2022.

Russian language. Fundamentals, methods of primary education

The formation of words from the letters of the alphabet, accepted in the modern methodology, the writing of words in the wake of analysis and the “printing” used in some schools, give children the opportunity to establish a connection between the sound composition of the analyzed word and its designation in the form of a sequential series of strictly defined letters. Wrong DB Elkonin, when he claims that when working with the split alphabet and when writing, only letters, not sounds, are the object of the child's action. Here the child undoubtedly operates with both: without correlating each graphic sign with the sound it denotes, the student will not compose or write a single word. To establish a strong connection between sounds and letters, and practiced at the initial stage of literacy, the mandatory analysis of each word with a new sound, with a new syllable, before students compose it from letters, “print” or write, and then read.

Wrong DB Elkonin, when he claims that when working with the split alphabet and when writing, only letters, not sounds, are the object of the child's action. Here the child undoubtedly operates with both: without correlating each graphic sign with the sound it denotes, the student will not compose or write a single word. To establish a strong connection between sounds and letters, and practiced at the initial stage of literacy, the mandatory analysis of each word with a new sound, with a new syllable, before students compose it from letters, “print” or write, and then read.

Syllabic reading of words consisting of one-letter and two-letter syllables (cheers, balls, he, gone) is a necessary initial stage in establishing an associative chain that makes up the reading mechanism. At the same time, it is easier for a child who is beginning to master literacy to learn two-letter open and closed syllables as a reading unit than three-letter syllables with a vowel in the middle (ball) or with a confluence of two consonants at the beginning of it (one hundred). And D. B. Elkonin believes that the preliminary division into syllables makes it difficult to determine the sound composition of a word due to the loss of its sound continuity. Therefore, completely bypassing the syllable, from the very beginning he trains children in the sequential naming of all the sounds that make up words, and for this purpose he uses vocabulary material of various syllabic structures, consisting of 3-5 or more sounds. Such a stringing of names of sounds, in addition to everything, when switching to reading before the children master the syllable as a unit of reading, can delay the acceptance of letter-by-letter reading in children who have learned it before school.

And D. B. Elkonin believes that the preliminary division into syllables makes it difficult to determine the sound composition of a word due to the loss of its sound continuity. Therefore, completely bypassing the syllable, from the very beginning he trains children in the sequential naming of all the sounds that make up words, and for this purpose he uses vocabulary material of various syllabic structures, consisting of 3-5 or more sounds. Such a stringing of names of sounds, in addition to everything, when switching to reading before the children master the syllable as a unit of reading, can delay the acceptance of letter-by-letter reading in children who have learned it before school.

Underestimation of work with syllables of gradually increasing difficulty and early practical familiarization of children with the syllable-forming role of vowels, and therefore with the main feature of the term-concept "syllable" is, in our opinion, not an advantage, but a disadvantage of D. B. Elkonin's system .

Elkonin's system .

The method of teaching writing now accepted in the Soviet school is criticized by teachers, methodologists and researchers due to the fact that:

lined;

2) the accepted style of letters often does not make it possible to achieve from children an uninterrupted letter, which is so advantageous for cursive writing;

3) the complex design of a number of capital letters makes it necessary to transfer the teaching of their writing to a later period and for a long time limits the choice of sentences possible for writing.

In the modern Soviet methodology , the sound analytical-synthetic method of teaching literacy, laid down by the works of KD Ushinsky , was improved mainly on the basis of new data from the science of language. In this case, a particularly prominent place belongs to S.P. Redozubov . From the psychological side, the method of teaching literacy adopted by the Soviet school is covered in the works of T. G. Egorova, L. M. Schwartz, B. G. Ananiev, A. A. Lyublinskaya and others. , first-graders already in the preparatory period practically get acquainted with the first terms, meaning such generalized concepts as "sentence", "word", "syllable". They learn to use these concepts by dividing by ear simple sentences without prepositions and conjunctions into words, words into syllables, and again combining syllables into words. They can make a sentence from a picture, about a given subject, with a specified number of words; select drawings depicting objects with a specified initial sound or with a given number of syllables in their names, they themselves come up with words in accordance with the same tasks. Children learn the first sounds and letters ( a, y, m, w ) and begin to understand the difference between them: we see letters when we read and write, sounds - we pronounce and hear. They practice sound analysis of the first open and closed syllables into two sounds, in the formation of the same syllables from sounds, in composing and reading (based on the vowel) these first syllables, isolated from words and again negotiated to whole words.

G. Egorova, L. M. Schwartz, B. G. Ananiev, A. A. Lyublinskaya and others. , first-graders already in the preparatory period practically get acquainted with the first terms, meaning such generalized concepts as "sentence", "word", "syllable". They learn to use these concepts by dividing by ear simple sentences without prepositions and conjunctions into words, words into syllables, and again combining syllables into words. They can make a sentence from a picture, about a given subject, with a specified number of words; select drawings depicting objects with a specified initial sound or with a given number of syllables in their names, they themselves come up with words in accordance with the same tasks. Children learn the first sounds and letters ( a, y, m, w ) and begin to understand the difference between them: we see letters when we read and write, sounds - we pronounce and hear. They practice sound analysis of the first open and closed syllables into two sounds, in the formation of the same syllables from sounds, in composing and reading (based on the vowel) these first syllables, isolated from words and again negotiated to whole words.

Read the rest of the entry »

A. A. Lyublinskaya also speaks about the significance of the early primary generalization , associated with understanding the syllable-forming role of the vowel. First-graders experience difficulties “when dividing a word into syllables, if the teacher delays the acquaintance of children with the concept of “vowel sound”, without which the concept of “syllable” cannot be given. When they try to give students the first grammatical knowledge without introducing the children to the relevant terms, “children are deprived of the knowledge they need for the competent division of speech”, their work becomes more difficult instead of easier, and the formation of reading and writing skills is delayed.

Referring to the special study conducted by Lyublinskaya and Titova of the fact that children confuse the concepts of "word" and "syllable", BG Ananiev rightly emphasizes the dependence of the formation of reading and writing skills on the child's constant generalizations of the results of his analytical work on speech.

Learn more