Teach young children

New skills for kids & behaviour management

Helping children learn new skills as part of behaviour management

When children can do the things they want or need to do, they’re more likely to cooperate. They’re also less likely to get frustrated and behave in challenging ways. This means that helping children learn new skills can be an important part of managing behaviour.

When children learn new skills, they also build independence, confidence and self-esteem. So helping children learn new skills can be an important part of supporting overall development too.

Here’s an example: if your child doesn’t know how to set the table, they might refuse to do it – because they can’t do it. But if you show your child how to set the table, they’re more likely to do it. They’ll also get a sense of achievement and feel good about helping to get your family meal ready.

There are 3 key ways you can help children learn everything from basic self-care to more complicated social skills:

- modelling

- instructions

- step by step.

Remember that skills take time to develop, and practice is important. But if you have any concerns about your child’s behaviour, development or ability to learn new skills, see your GP or your child and family health nurse.

When you’re helping your child learn a skill, you can use more than one teaching method at a time. For example, your child might find it easier to understand instructions if you also break down the skill or task into steps. Likewise, modelling might work better if you give instructions at the same time.

Modelling

Through watching you, your child learns what to do and how to do it. When this happens, you’re ‘modelling’.

Modelling is usually the most efficient way to help children learn a new skill. For example, you’re more likely to show rather than tell your child how to make a bed, sweep a floor or throw a ball.

Modelling can work for social skills. Prompting your child with phrases like ‘Thank you, Mum’, or ‘More please, Dad’ is an example of this.

You can also use modelling to show your child skills and behaviour that involve non-verbal communication, like body language and tone of voice. For example, you can show how you turn to face people when you talk to them, or look them in the eyes and smile when you thank them.

Children also learn by watching other children. For example, your child might try new foods with other children at preschool even though they might not do this at home with you.

How to make modelling work well

- Get your child’s attention, and make sure your child is looking at you.

- Move slowly through the steps of the skill so that your child can clearly see what you’re doing.

- Point out the important parts of what you’re doing – for example, ‘See how I am …’. You might want to do this later if you’re modelling social skills like greeting a guest.

- Give your child plenty of opportunities to practise the skill once they’ve seen you do it – for example, ‘OK, now you have a go’.

Instructions

You can help your child learn how to do something by explaining what to do or how to do it.

How to give good instructions

- Give instructions only when you have your child’s attention.

- Use your child’s name and encourage your child to look at you while you speak.

- Get down to your child’s physical level to speak.

- Remove any background distractions like the TV.

- Use language that your child understands. Keep your sentences short and simple.

- Use a clear, calm voice.

- Use gestures to emphasise things that you want your child to notice.

- Gradually phase out your instructions and reminders as your child gets better at remembering how to do the skill or task.

A picture that shows your child what to do can help them understand the instructions. Your child can check the picture when they’re ready to work through the instructions independently. This can also help children who have trouble understanding words.

Sometimes your child won’t follow instructions. This can happen for many reasons. Your child might not understand. Your child might not have the skills to do what you ask every time. Or your child just might not want to do what you’re asking. You can help your child learn to cooperate by balancing instructions and requests.

Step-by-step guidance: breaking down tasks

Some skills or tasks are complicated or involve a sequence of actions. You can break these skills or tasks into smaller steps. The idea is to help children learn the steps that make up a skill or task, one at a time.

How to do step-by-step guidance

- Start with the easiest step if you can.

- Show your child the step, then let them try it.

- Give your child more help with the rest of the task or do it for them.

- Give your child opportunities to practise the step.

- When your child can do the step reliably and without your help, teach them the next step, and so on.

- Keep going until your child can do the whole skill or task for themselves.

An example of step-by-step guidance

Here’s how you could break down the task of getting dressed:

- Get clothes out.

- Put on underpants.

- Put on socks.

- Put on shirt.

- Put on pants.

- Put on a jumper.

You could break down each of these steps into parts as well. This can help if a task is complex or if your child has learning difficulties. For example, ‘Put on a jumper’ could be broken down like this:

- Face the jumper the right way.

- Pull the jumper over your head.

- Put one arm through.

- Put your other arm through.

- Pull the jumper down.

Forwards or backwards steps?

You can help your child learn steps by moving:

- forwards – teaching your child the first step, then the next step and so on

- backwards – helping your child with all the steps until the last step, then teaching the last step, then the second last step and so on.

Learning backwards has some advantages. Your child is less likely to get frustrated because it’s easier and quicker to learn the last step. Also the task is finished as soon as your child completes the step. Often the most rewarding thing about a job or task is getting it finished!

In the earlier example, you might teach your child to get dressed by starting with a jumper. You’d help your child get dressed until it came to the final step – the jumper.

You might help your child put the jumper over their head and put their arms in – then you might let your child pull the jumper down by themselves. Once your child can do this, you might encourage your child to put their arms through by themselves and then pull the jumper down. This would go on until your child can do each step, so they can do the whole task for themselves.

When your child is learning a new physical skill like getting dressed, it can help to put your hands over your child’s hands and guide your child through the movements. Phase out your help as your child begins to get the idea, but keep saying what to do. Then simply point or gesture. When your child is confident with the skill, you can phase out gestures too.

Phase out your help as your child begins to get the idea, but keep saying what to do. Then simply point or gesture. When your child is confident with the skill, you can phase out gestures too.

Tips to help children learn new skills

No matter which of the methods you use, these tips will help your child learn new skills:

- Make sure that your child has the physical ability and developmental maturity to handle the new skill. You might need to teach your child some basic skills before working on more complicated skills.

- Consider timing and environment. Children learn better when they’re alert and focused, so it can be good to work on new skills in the morning or after rest time. It’s also good to avoid distractions, like the TV or younger siblings.

- Give your child the chance to practise the skill. Skills take time to learn, and the more your child practises, the better.

- Give lots of praise and encouragement, especially in the early stages of learning.

Praise your child when they follow your instruction, practise the skill or try hard, and say exactly what your child did well.

Praise your child when they follow your instruction, practise the skill or try hard, and say exactly what your child did well. - Avoid giving negative feedback. Rather than saying your child has done it ‘wrong’, use words and gestures to explain 1-2 things your child could do differently next time.

Remember that behaviour might get worse before it improves, especially if you’re asking more from your child. A positive and constructive approach can help – for example, ‘Well done for getting the knots on your laces right! Would you like to do the loops together today?’

Teaching children to read isn’t easy. How do kids actually learn to read?

A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger ReportTeaching kids to read isn’t easy; educators often feel strongly about what they think is the “right” way to teach this essential skill. Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

How do kids actually learn how to read?

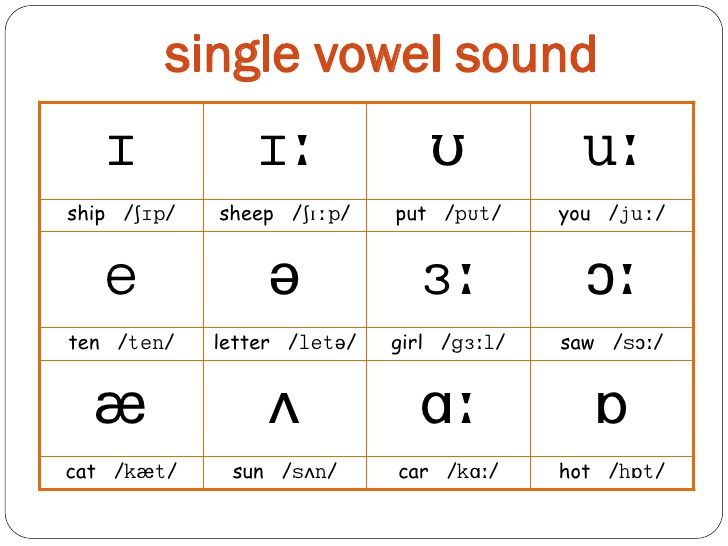

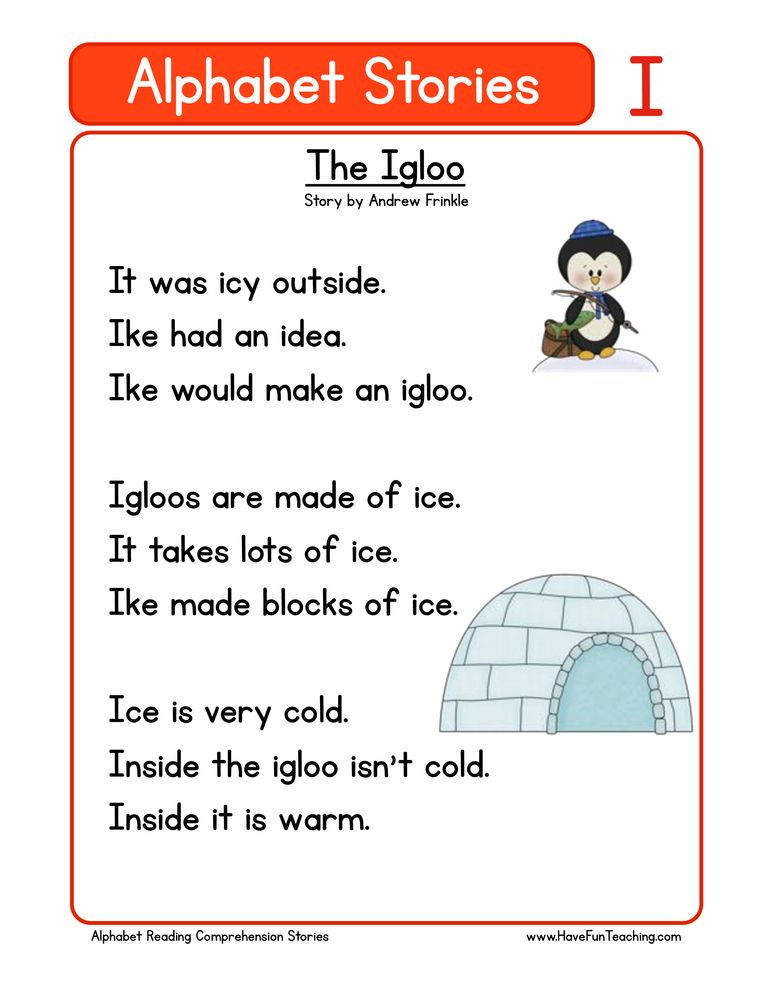

Research shows kids learn to read when they are able to identify letters or combinations of letters and connect those letters to sounds. There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

Reading Matters

The Hechinger Report has been covering reading for over a decade, as debates about how to teach it have intensified. Check in with us for the latest in reading research.

If children can’t master phonics, they are more likely to struggle to read. That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

How should your child’s school teach reading?

Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on reading instruction, said phonics are important in kindergarten through second grade and phonemic awareness should be explicitly taught in kindergarten and first grade. This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

The wars over how to teach reading are back. Here’s the four things you need to know.

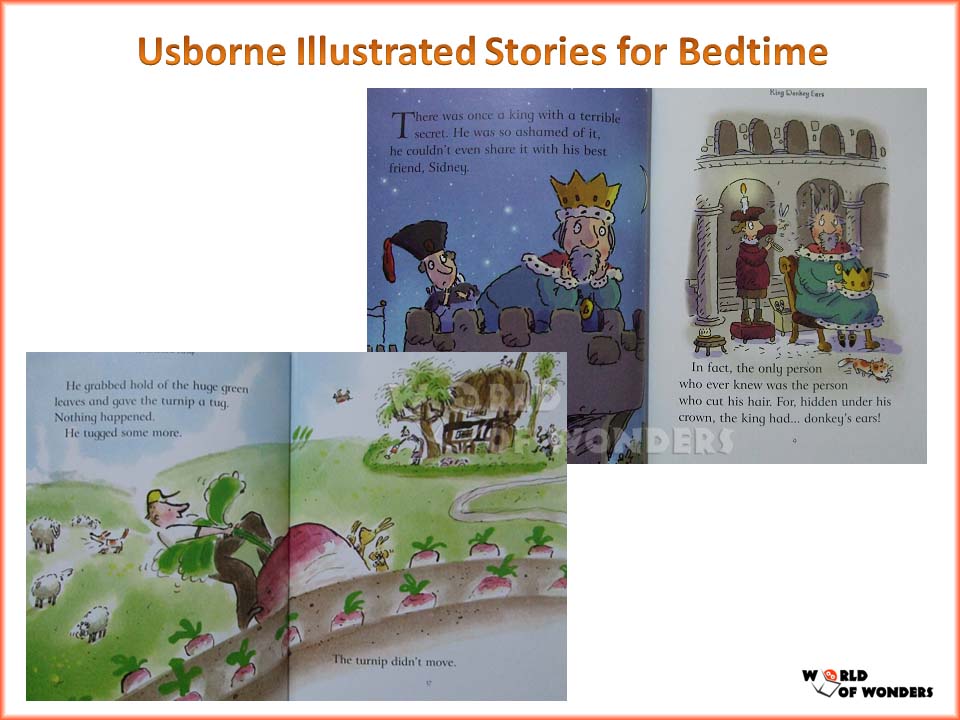

Wiley Blevins, an author and expert on phonics, said a good test parents can use to determine whether a child is receiving research-based reading instruction is to ask their child’s teacher how reading is taught. “They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

Rasmussen’s school uses a structured approach: Children receive lessons in phonemic awareness, phonics, pre-writing and writing, vocabulary and repeated readings. Research shows this type of “systematic and intensive” approach in several aspects of literacy can turn children who struggle to read into average or above-average readers.

What should schools avoid when teaching reading?

Educators and experts say kids should be encouraged to sound out words, instead of guessing. “We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

Related: Teacher Voice: We need phonics, along with other supports, for reading

Blevins and Shanahan caution against organizing books by different reading levels and keeping students at one level until they read with enough fluency to move up to the next level. Although many people may think keeping students at one level will help prevent them from getting frustrated and discouraged by difficult texts, research shows that students actually learn more when they are challenged by reading materials.

Blevins said reliance on “leveled books” can contribute to “a bad habit in readers.” Because students can’t sound out many of the words, they rely on memorizing repeated words and sentence patterns, or on using picture clues to guess words. Rasmussen said making kids stick with one reading level — and, especially, consistently giving some kids texts that are below grade level, rather than giving them supports to bring them to grade level — can also lead to larger gaps in reading ability.

How do I know if a reading curriculum is effective?

Some reading curricula cover more aspects of literacy than others. While almost all programs have some research-based components, the structure of a program can make a big difference, said Rasmussen. Watching children read is the best way to tell if they are receiving proper instruction — explicit, systematic instruction in phonics to establish a foundation for reading, coupled with the use of grade-level texts, offered to all kids.

Parents who are curious about what’s included in the curriculum in their child’s classroom can find sources online, like a chart included in an article by Readingrockets.org which summarizes the various aspects of literacy, including phonics, writing and comprehension strategies, in some of the most popular reading curricula.

Blevins also suggested some questions parents can ask their child’s teacher:

- What is your phonics scope and sequence?

“If research-based, the curriculum must have a clearly defined phonics scope and sequence that serves as the spine of the instruction. ” Blevins said.

” Blevins said.

- Do you have decodable readers (short books with words composed of the letters and sounds students are learning) to practice phonics?

“If no decodable or phonics readers are used, students are unlikely to get the amount of practice and application to get to mastery so they can then transfer these skills to all reading and writing experiences,” Blevins said. “If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

- What are you doing to build students’ vocabulary and background knowledge? How frequent is this instruction? How much time is spent each day doing this?

“It should be a lot,” Blevins said, “and much of it happens during read-alouds, especially informational texts, and science and social studies lessons. ”

”

- Is the research used to support your reading curriculum just about the actual materials, or does it draw from a larger body of research on how children learn to read? How does it connect to the science of reading?

Teachers should be able to answer these questions, said Blevins.

What should I do if my child isn’t progressing in reading?

When a child isn’t progressing, Blevins said, the key is to find out why. “Is it a learning challenge or is your child a curriculum casualty? This is a tough one.” Blevins suggested that parents of kindergarteners and first graders ask their child’s school to test the child’s phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency.

Parents of older children should ask for a test of vocabulary. “These tests will locate some underlying issues as to why your child is struggling reading and understanding what they read,” Blevins said. “Once underlying issues are found, they can be systematically addressed. ”

”

“We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs. But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York

Rasmussen recommended parents work with their school if they are concerned about their children’s progress. By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

“Teachers aren’t there doing necessarily bad things or disadvantaging kids purposefully or willfully,” Rasmussen said. “You have many great reading teachers using some effective strategies and some ineffective strategies.”

What can parents do at home to help their children learn to read?

Parents want to help their kids learn how to read but don’t want to push them to the point where they hate reading. “Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

“Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

- Challenge kids to find everything in the house that starts with a specific sound.

- Stretch out one word in a sentence. Ask your child to “pass the salt” but say the individual sounds in the word “salt” instead of the word itself.

- Ask your child to figure out what every family member’s name would be if it started with a “b” sound.

- Sing that annoying “Banana fana fo fanna song.” Jiban said that kind of playful activity can actually help a kid think about the sounds that correspond with letters even if they’re not looking at a letter right in front of them.

- Read your child’s favorite book over and over again. For books that children know well, Jiban suggests that children use their finger to follow along as each word is read. Parents can do the same, or come up with another strategy to help kids follow which words they’re reading on a page.

Giving a child diverse experiences that seem to have nothing to do with reading can also help a child’s reading ability. By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

This story about teaching children to read was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

How to teach mathematics to young children. And is it necessary? Often parents do not fully understand when and what it is time to do with their children. And when a child at the age of one and a half or two is told: “Come on, baby, we will learn letters and numbers” - this is not for age. And what about age? How to do math with the little ones?

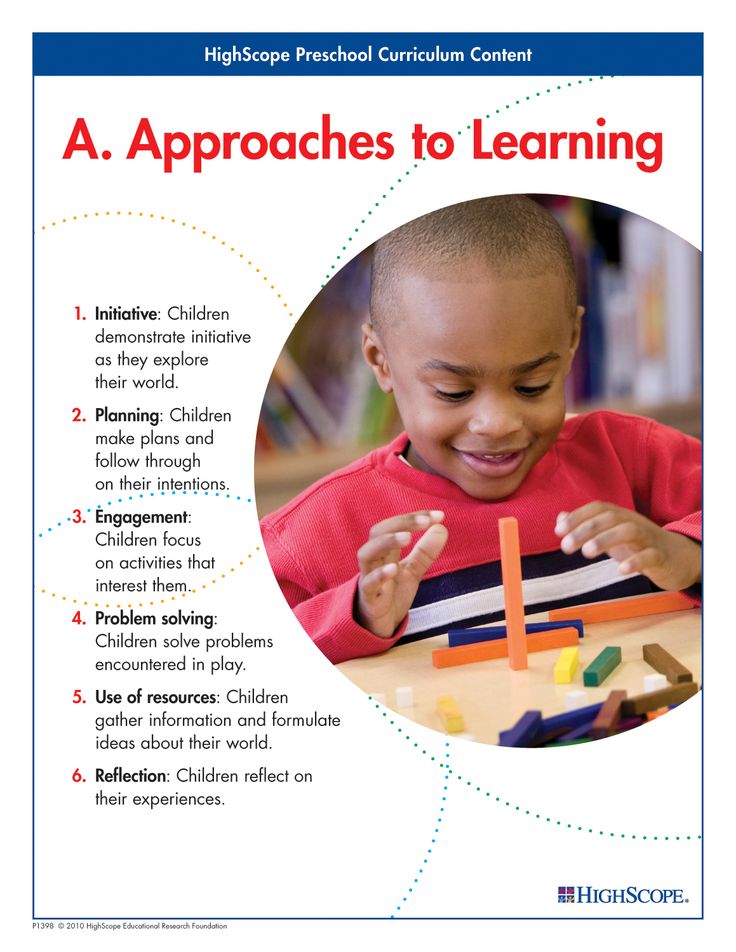

1. Play. Many

Play is a natural state for young children and their main activity, including cognitive. In the game, information is best absorbed and skills are mastered. If you want your child to understand something, play it with him. The language of the game is the most understandable language for children.

2. Translate everything into body language

Everything that we do with the child should be passed through his body. Through the game and through the body.

In our classes with kids, we translate everything into some movements understandable to the child. Wave with one hand, wave with both hands. Stand on one foot, pat one knee, hide one knee, hide two knees. Hide one ear. How many fingers I raised - knock so many times. How many times I say meow, so many times jump. How many times I clapped, take so many steps.

We translate one movement into another, and then we begin to translate them into quantity. We speak to the child in the language of the body of the child - the language he understands.

3. No abstractions

four-five-..." and so on. But this is not yet an account.

Right. Draw some line and say: “here I have 1, here I have 10, here I have 20, show me where 15 is.” And when he counts, then he will know where 15 is. And until he goes through all the steps in order, he does not know.

And until he goes through all the steps in order, he does not know.

What do we do when we work with preschoolers in our math clubs?

- First, we advise parents not to rush into counting.

- Secondly, we make maximum use of various counting materials. Everything that we count, we must count on some objects.

Example. For four-year-olds, for example, playing with counting beads is like magic or a trick in a circus. You can put any beads on a string - five of one color, five of another. This is quite enough for a small child. And then you squeeze a few beads in the middle into a fist: “How many beads have I hidden now? What colour?". And then the child says: "Let me guess for you, and you guess." He thinks to me, and I look and say - yeah, you hid one blue and two red ones. The child opens his palm - and indeed, one is blue and one is red!

We use everything: counting sticks, counting cubes and just cubes, numikon and its Russian analogue, which is called "Alice", count on the fingers (we definitely count on the fingers!) . .. When the children are all these 1-2-3-4 -5 touch them with their fingers, shift them from hand to hand or from bunch to bunch, they will begin to understand them.

.. When the children are all these 1-2-3-4 -5 touch them with their fingers, shift them from hand to hand or from bunch to bunch, they will begin to understand them.

4. Choose, compare, do the same...

In fact, these are logical tasks. Identification of similarities, differences, patterns. And children cope with them, and do them with passion and very diligently.

For very young children (2-3 years old), we ask you to arrange the cubes: red ones on a red plate, blue ones on a blue one. It happens that children do not yet know what word what color is called, but they cope with the task.

Everyone coped, you can move on. Here I will put a turret of three cubes, you put the same one. Many children say: "No, I'll add this, and you repeat it." Also good. In this version, you can make a small mistake and ask the child: “I definitely did it, how did you do it? And look carefully? Or maybe this cube needs to be moved to the edge? Or turn the triangular cube the other side?

5.

Speak

Speak What other tower can be built from the same three cubes? Yes, a triangular cube on the side, not just on top. And now - another one, similar to the first one, but it has a cube on the edge. And we voice everything we do. Because without speech, we will not move anywhere. On, above, below, in the middle, on the edge... This is important, this is spatial thinking.

With children from four years old, you can build according to schemes, from five years old, you can sketch what you have built in the cells.

Lessons with toddlers (2-4 years old) should be playful! Everything that the child learns, he must beat, as well as feel with his body and touch with his own hands. The time for abstract concepts will come later. Now the child should play, move, talk and touch!

Photo: Shutterstock (pan_kung)

6 Ways to Teach Your Child to Learn

One of the most common parenting questions is “My child doesn’t want to learn, what should I do?”. But in order to want to learn, you must at least be able to learn. And this is a skill! Our blogger, child psychologist Olga Kondrashova talks about how to acquire and develop this skill.

But in order to want to learn, you must at least be able to learn. And this is a skill! Our blogger, child psychologist Olga Kondrashova talks about how to acquire and develop this skill.

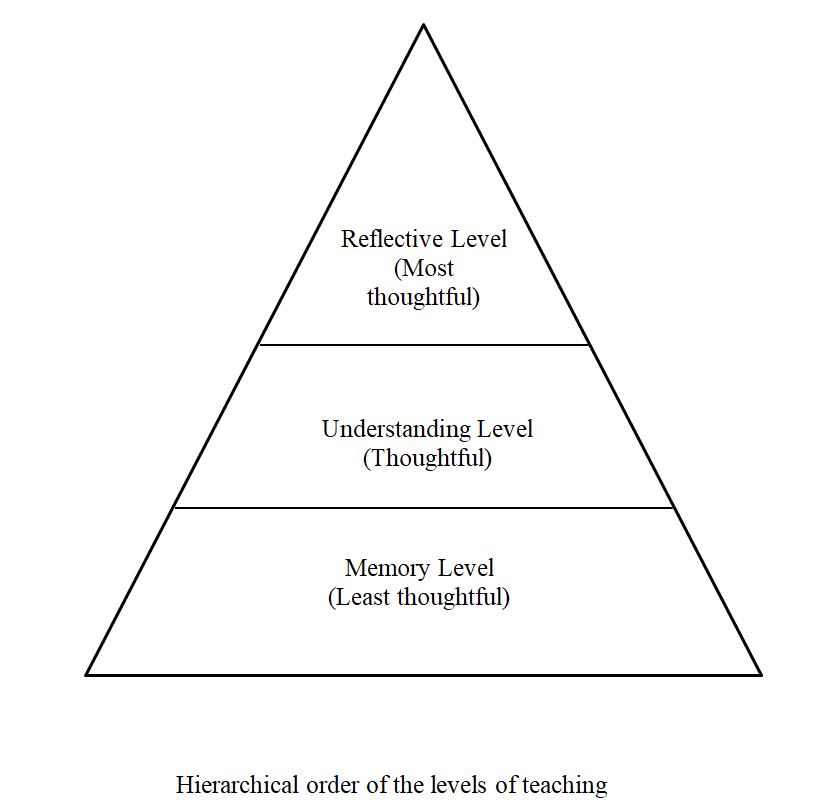

You should not expect that a child will be able to do it on his own: while a small person is in grades 1-2 (in grade 3, responsibility for oneself more or less begins to turn on), he is not yet very collected, organized, simply “sane”. Therefore, he needs outside control, that is, he must simply be taught to learn, to show how it is done.

Of course, there are children who, due to increased anxiety, for example, fear of the teacher or parents, or, conversely, excessive fascination with the teacher (more common among girls), are themselves worried about doing homework. But this is rather an exception to the general rule. So, the responsibility for a child's ability to learn lies largely with adults!

Now there are many expert assessments that come down to the thesis - the child's interest is above all. I agree that it is criminal to crush the initiative of a child. But, unfortunately, excitement from novelty falls even in an adult, and the ability to return oneself to concentration, whether it be solving a problem or simply assimilating new information, I think, will remain relevant. At least until we are "chip" with already built-in programs, by analogy with gadgets. But for now, you and I have children, not robots. And after a certain time, your child will move from elementary school to high school, where it will be more difficult to study.

I agree that it is criminal to crush the initiative of a child. But, unfortunately, excitement from novelty falls even in an adult, and the ability to return oneself to concentration, whether it be solving a problem or simply assimilating new information, I think, will remain relevant. At least until we are "chip" with already built-in programs, by analogy with gadgets. But for now, you and I have children, not robots. And after a certain time, your child will move from elementary school to high school, where it will be more difficult to study.

In addition, the motivational priority shifts in high school — the child “flies” from the importance of learning to the importance of establishing social connections (friends are above all!)

he will no longer fall into hopelessness or despair - "everything is useless, everything is already so neglected, such a wild volume, I can no longer cope with it, there is no point in even starting!". There will be no such problems if the child already has a conscious experience of "inclusion" in the lessons. How to keep the attention of the child during the lessons?

How to keep the attention of the child during the lessons?

1. Give new meaning to boring tasks

For example, a child needs to learn how to write letters beautifully. Options: “OK, how are we going to write a message to Santa Claus? He won’t understand anything in your scribbles, it will be a shame if you don’t get what you ask for for the New Year ”... Or: “Let's write a letter to grandmother? You just need to write so that she can read, she doesn’t see very well!” Or: “What if you find yourself on a desert island? Then you will need to write a message to people and send it in a bottle. Let's learn to write legibly!

2. Stimulate intrinsic motivation

You can ask a child and encourage him to think about what this or that skill will give him - the ability to read, write, count, memorize. This can become the basis of his own intrinsic motivation - the strongest and brightest stimulus. Alas, it burns brightly, but not for very long. It will be necessary to periodically remind the child about the benefits of what he himself once thought of and what he himself came to.

3. Change roles - instead of a student "teacher"

All lecturers know that if you want to know a subject better, give a lecture on it. We turn the child into a teacher, put all his bunnies, cars, bears, dolls in front of him and play school. By the way, you can also play along in the role of the most naughty and most "talentless" student - "Oh, how difficult it is to write these numbers! I can't do it at all!" Or deliberately make a lot of mistakes. Usually children are very happy when they see themselves from the outside.

This technique relieves tension, allows you to speak in a safe mode and realize the difficulty of learning. And this, as you remember, improves self-control and increases "sanity", that is, the child sees an obstacle (laziness, inattention, inability to force himself to finish) with which he needs to cope.

Plus, this reduces the fear of making mistakes. This is a very important point, because children at school are constantly in the zone of anxiety and incompetence - every day they are faced with new material, new tasks and new requirements for their intellectual abilities. The ability to calmly endure failures and mistakes is an important quality that allows you to move forward, and not fall into the pit "I am a worthless clumsy."

The ability to calmly endure failures and mistakes is an important quality that allows you to move forward, and not fall into the pit "I am a worthless clumsy."

4. Teach him to do his homework

After some time, when you see that the child has mastered the skill of "doing homework", we gradually begin to leave him alone. But it is necessary to make sure that the child understands that failure to do homework and poor study in general have negative emotional consequences for him. That is, you need to create a field of expectations around it, in which there are necessarily two topics.

First, let him know that you appreciate his efforts. You can say: “We are happy when you are doing well” or “We are upset when you are not doing well.” So the child will learn that you respect his work, his efforts on himself, his ability to show his will, his growing and strengthening independence. This also allows one to form such an important quality of character as the ability to achieve goals and respect oneself for the result achieved.

The child will learn to motivate himself with this experience and the feeling of joy and elation that will follow each self-conquest. An important nuance - try to make your comments for the child clear and specific. Not just "You're great!" or “Excellent!”, but “How glad I am that you managed to finish everything!”.

Second - say that if something does not work out, then this is not a disaster! This will allow the child to avoid excessive anxiety about punishments and disappointment in him and remove a negative emotional connotation from the learning process. For example, you can tell him: “If something doesn’t work out so well for you, know that we will always help you”, “We will not scold you for a bad grade. Let's just agree, if something doesn't work out for you or you don't understand something at school, speak right away and together we will sort out difficult places or explain to you what you didn't understand. We will always help, the main thing is not to launch the item, ok?".![]()