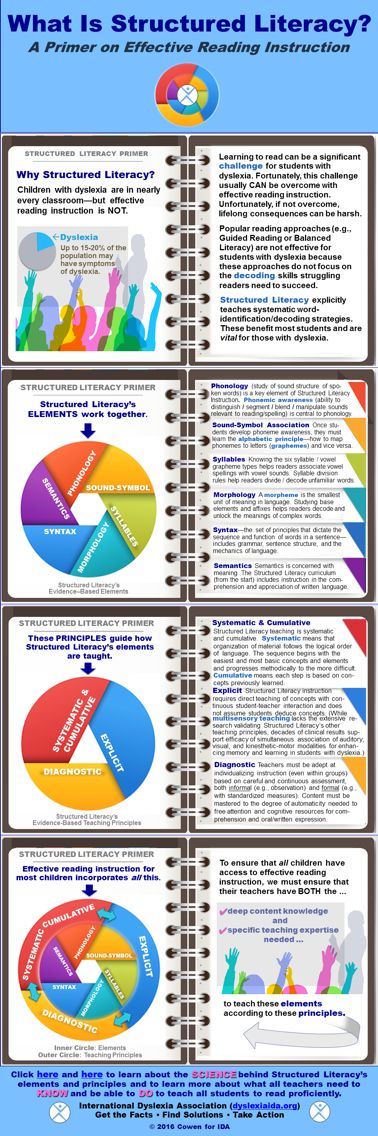

Teaching alphabetic principle

The Alphabetic Principle | Reading Rockets

Not knowing letter names is related to children's difficulty in learning letter sounds and in recognizing words. Children cannot understand and apply the alphabetic principle (understanding that there are systematic and predictable relationships between written letters and spoken sounds) until they can recognize and name a number of letters.

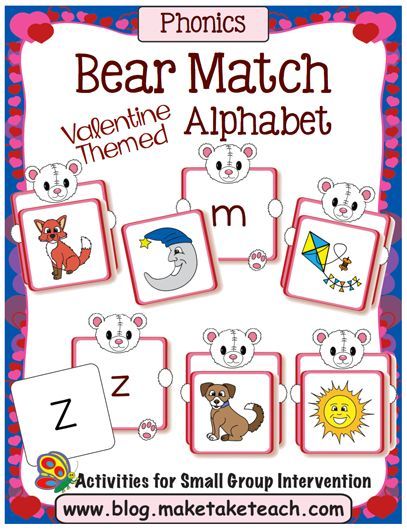

Children whose alphabetic knowledge is not well developed when they start school need sensibly organized instruction that will help them identify, name, and write letters. Once children are able to identify and name letters with ease, they can begin to learn letter sounds and spellings.

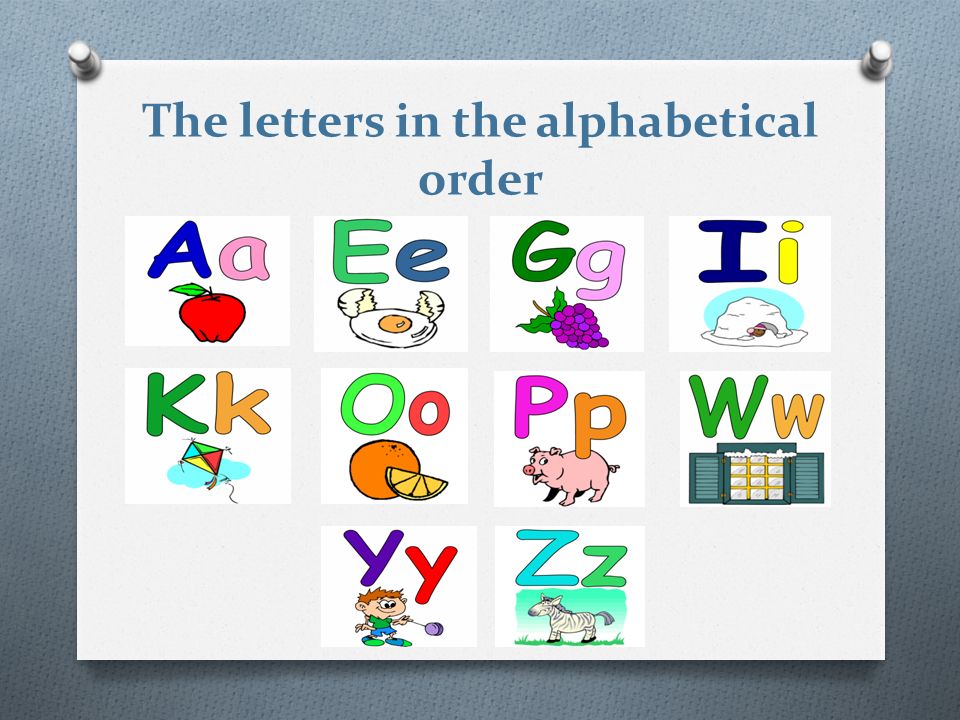

Children appear to acquire alphabetic knowledge in a sequence that begins with letter names, then letter shapes, and finally letter sounds. Children learn letter names by singing songs such as the "Alphabet Song," and by reciting rhymes. They learn letter shapes as they play with blocks, plastic letters, and alphabetic books.

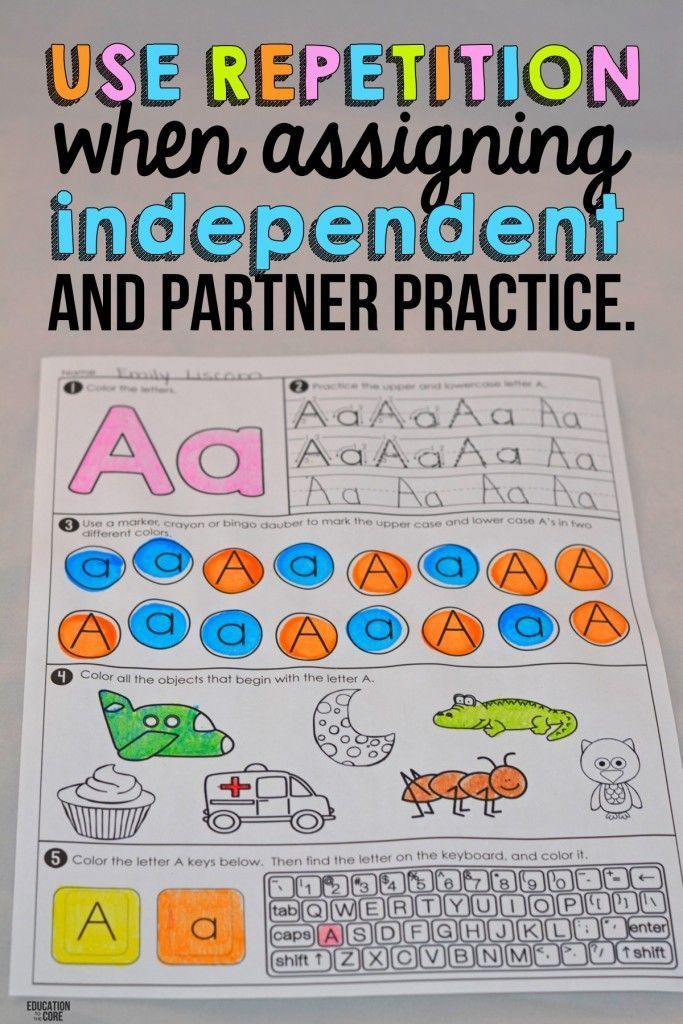

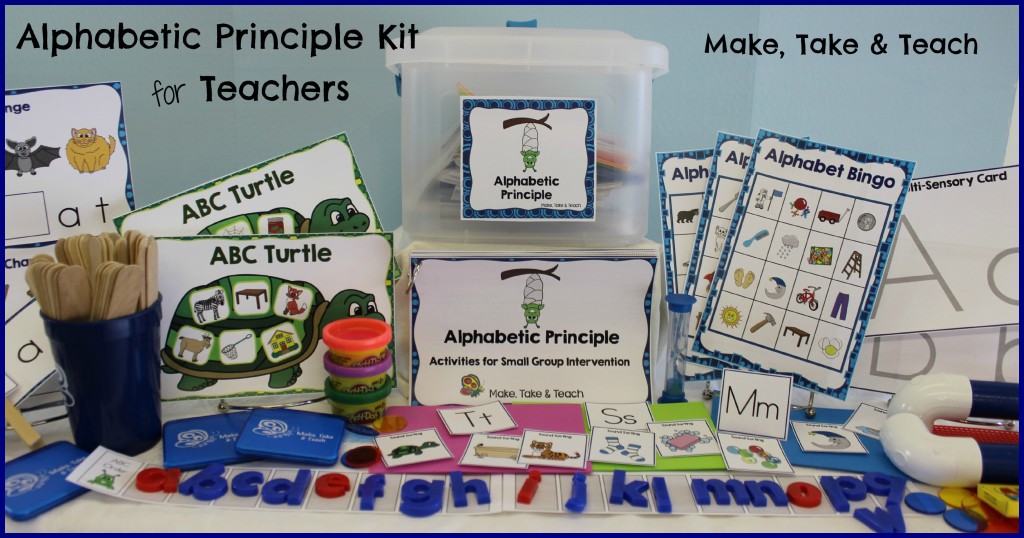

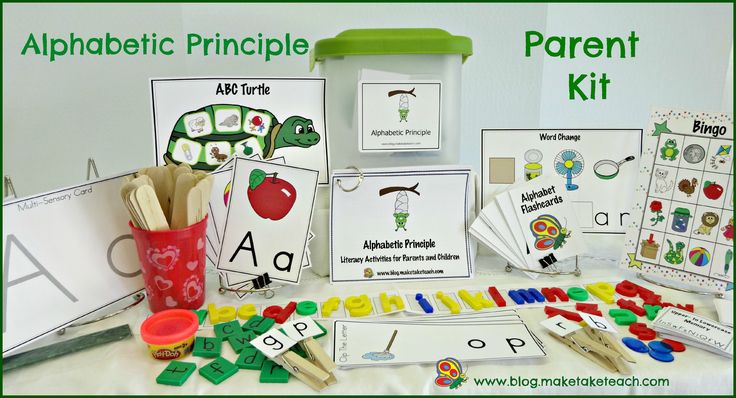

Informal but planned instruction in which children have many opportunities to see, play with, and compare letters leads to efficient letter learning. This instruction should include activities in which children learn to identify, name, and write both upper case and lower case versions of each letter.

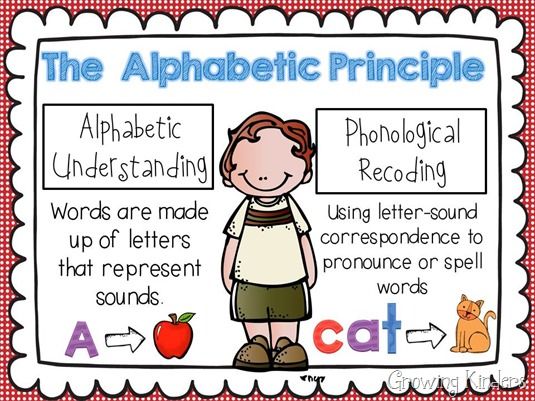

What is the "alphabetic principle"?

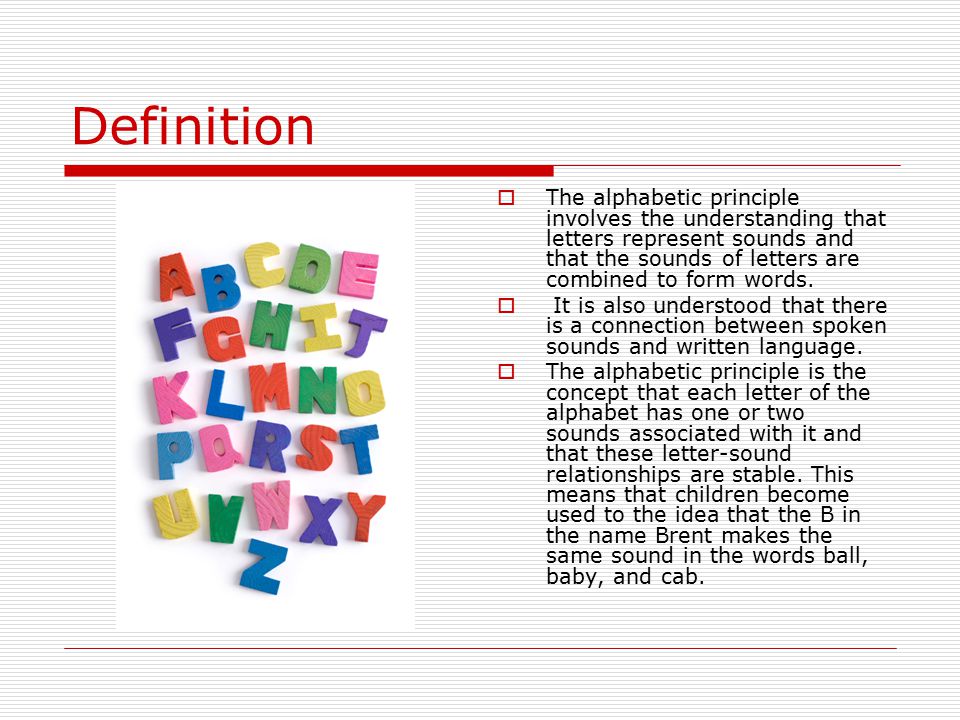

Children's reading development is dependent on their understanding of the alphabetic principle – the idea that letters and letter patterns represent the sounds of spoken language. Learning that there are predictable relationships between sounds and letters allows children to apply these relationships to both familiar and unfamiliar words, and to begin to read with fluency.

The goal of phonics instruction is to help children to learn and be able to use the Alphabetic Principle. The alphabetic principle is the understanding that there are systematic and predictable relationships between written letters and spoken sounds. Phonics instruction helps children learn the relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language.

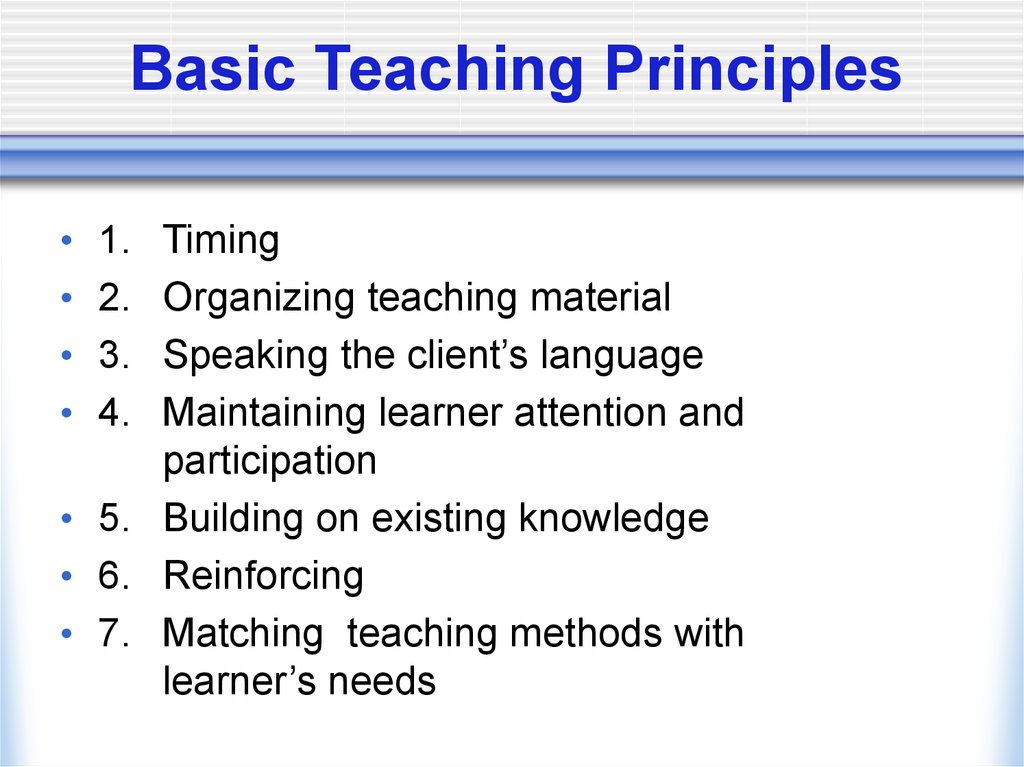

Two issues of importance in instruction in the alphabetic principle are the plan of instruction and the rate of instruction.

The alphabetic principle plan of instruction

- Teach letter-sound relationships explicitly and in isolation.

- Provide opportunities for children to practice letter-sound relationships in daily lessons.

- Provide practice opportunities that include new sound-letter relationships, as well as cumulatively reviewing previously taught relationships.

- Give children opportunities early and often to apply their expanding knowledge of sound-letter relationships to the reading of phonetically spelled words that are familiar in meaning.

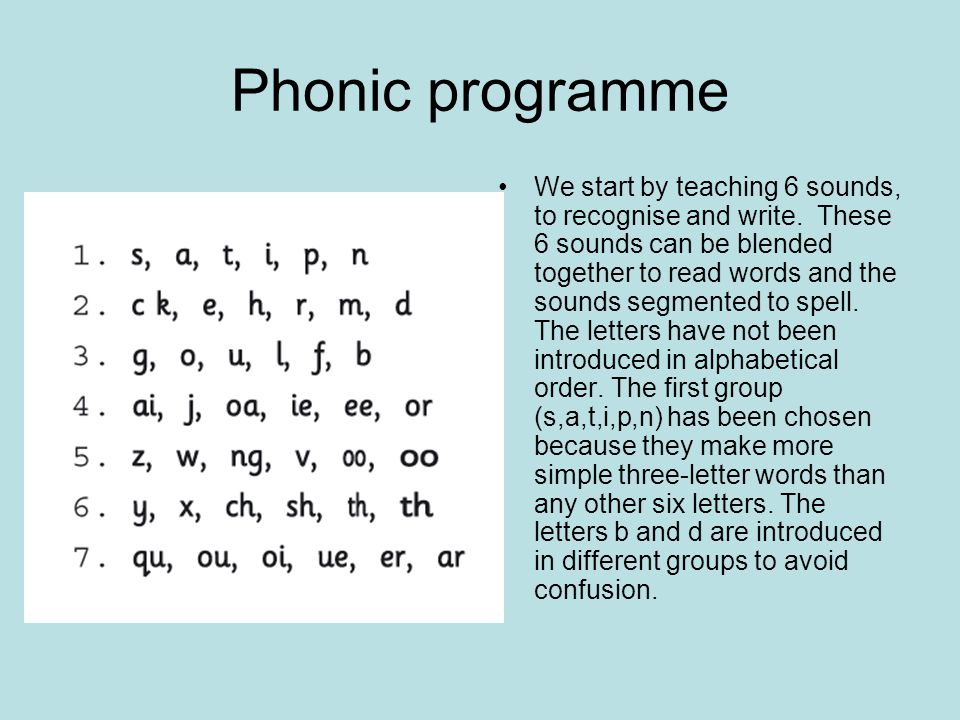

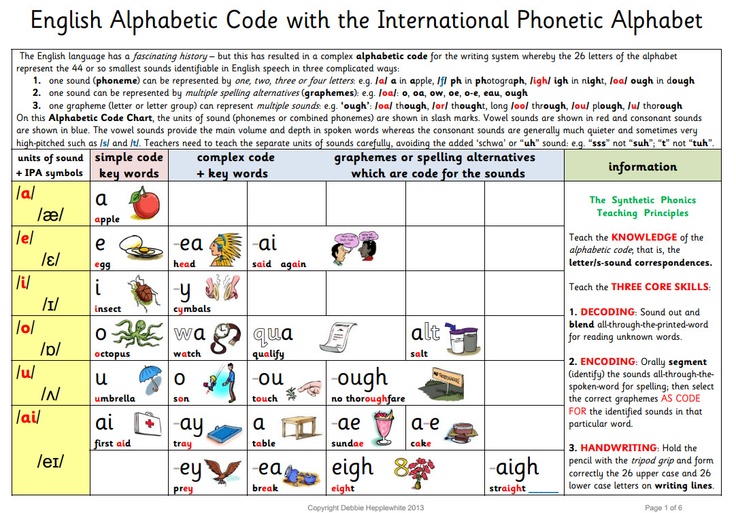

Rate and sequence of instruction

No set rule governs how fast or how slow to introduce letter-sound relationships. One obvious and important factor to consider in determining the rate of introduction is the performance of the group of students with whom the instruction is to be used. Furthermore, there is no agreed upon order in which to introduce the letter-sound relationships. It is generally agreed, however, that the earliest relationships introduced should be those that enable children to begin reading words as soon as possible. That is, the relationships chosen should have high utility. For example, the spellings m, a, t, s, p, and h are high utility, but the spellings x as in box, gh, as in through, ey as in they, and a as in want are of lower utility.

Furthermore, there is no agreed upon order in which to introduce the letter-sound relationships. It is generally agreed, however, that the earliest relationships introduced should be those that enable children to begin reading words as soon as possible. That is, the relationships chosen should have high utility. For example, the spellings m, a, t, s, p, and h are high utility, but the spellings x as in box, gh, as in through, ey as in they, and a as in want are of lower utility.

It is also a good idea to begin instruction in sound-letter relationships by choosing consonants such as f, m, n, r, and s, whose sounds can be pronounced in isolation with the least distortion. Stop sounds at the beginning or middle of words are harder for children to blend than are continuous sounds.

Instruction should also separate the introduction of sounds for letters that are auditorily confusing, such as /b/ and /v/ or /i/ and /e/, or visually confusing, such as b and d or p and g.

Instruction might start by introducing two or more single consonants and one or two short vowel sounds. It can then add more single consonants and more short vowel sounds, with perhaps one long vowel sound. It might next add consonant blends, followed by digraphs (for example, th, sh, ch), which permits children to read common words such as this, she, and chair. Introducing single consonants and consonant blends or clusters should be introduced in separate lessons to avoid confusion.

The point is that the order of introduction should be logical and consistent with the rate at which children can learn. Furthermore, the sound-letter relationships chosen for early introduction should permit children to work with words as soon as possible.

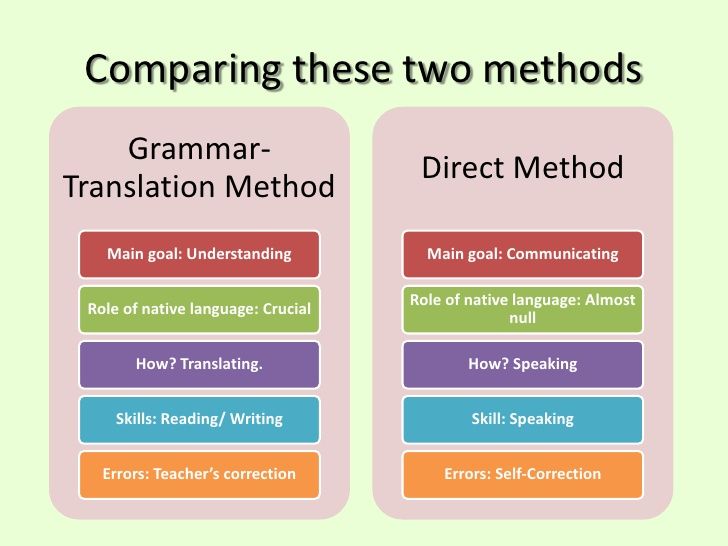

Many teachers use a combination of instructional methods rather than just one. Research suggests that explicit, teacher-directed instruction is more effective in teaching the alphabetic principle than is less-explicit and less-direct instruction.

Guidelines for rate and sequence of instruction

- Recognize that children learn sound-letter relationships at different rates.

- Introduce sound-letter relationships at a reasonable pace, in a range from two to four letter-sound relationships a week.

- Teach high-utility letter-sound relationships early.

- Introduce consonants and vowels in a sequence that permits the children to read words quickly.

- Avoid the simultaneous introduction of auditorily or visually similar sounds and letters.

- Introduce single consonant sounds and consonant blends/clusters in separate lessons.

- Provide blending instruction with words that contain the letter-sound relationships that children have learned.

Alphabetic Principle | Reading Rockets

Children's knowledge of letter names and shapes is a strong predictor of their success in learning to read. Knowing letter names is strongly related to children's ability to remember the forms of written words and their ability to treat words as sequences of letters.

Children whose alphabetic knowledge is not well developed when they start school need sensibly organized instruction that will help them identify, name, and write letters. Once children are able to identify and name letters with ease, they can begin to learn letter sounds and spellings.

Children appear to acquire alphabetic knowledge in a sequence that begins with letter names, then letter shapes, and finally letter sounds. Children learn letter names by singing songs such as the "Alphabet Song," and by reciting rhymes. They learn letter shapes as they play with blocks, plastic letters, and alphabetic books. Informal but planned instruction in which children have many opportunities to see, play with, and compare letters leads to efficient letter learning. This instruction should include activities in which children learn to identify, name, and write both upper case and lower case versions of each letter.

What is the "alphabetic principle"?

Children's reading development is dependent on their understanding of the alphabetic principle — the idea that letters and letter patterns represent the sounds of spoken language. Learning that there are predictable relationships between sounds and letters allows children to apply these relationships to both familiar and unfamiliar words, and to begin to read with fluency.

Learning that there are predictable relationships between sounds and letters allows children to apply these relationships to both familiar and unfamiliar words, and to begin to read with fluency.

The goal of phonics instruction is to help children to learn and be able to use the Alphabetic Principle. The alphabetic principle is the understanding that there are systematic and predictable relationships between written letters and spoken sounds. Phonics instruction helps children learn the relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language.

The alphabetic principle plan of instruction

The literacy program:

- Teaches letter-sound relationships explicitly and in isolation.

- Provides opportunities for children to practice letter-sound relationships in daily lessons.

- Provides practice opportunities that include new sound-letter relationships, as well as cumulatively reviewing previously taught relationships.

- Gives children opportunities early and often to apply their expanding knowledge of sound-letter relationships to the reading of phonetically spelled words that are familiar in meaning.

Rate and sequence of introduction

No set rule governs how fast or how slow to introduce letter-sound relationships. One obvious and important factor to consider in determining the rate of introduction is the performance of the group of students with whom the instruction is to be used. Furthermore, there is no agreed upon order in which to introduce the letter-sound relationships. It is generally agreed, however, that the earliest relationships introduced should be those that enable children to begin reading words as soon as possible. That is, the relationships chosen should have high utility. For example, the spellings m, a, t, s, p, and h are high utility, but the spellings x as in box, gh, as in through, ey as in they, and a as in want are of lower utility.

It is also a good idea to begin instruction in sound-letter relationships by choosing consonants such as f, m, n, r, and s, whose sounds can be pronounced in isolation with the least distortion. Stop sounds at the beginning or middle of words are harder for children to blend than are continuous sounds.

Stop sounds at the beginning or middle of words are harder for children to blend than are continuous sounds.

Instruction should also separate the introduction of sounds for letters that are auditorally confusing, such as /b/ and /v/ or /i/ and /e/, or visually confusing, such as b and d or p and g. Instruction might start by introducing two or more single consonants and one or two short vowel sounds. It can then add more single consonants and more short vowel sounds, with perhaps one long vowel sound. It might next add consonant blends, followed by digraphs (for example, th, sh, ch), which permits children to read common words such as this, she, and chair. Introducing single consonants and consonant blends or clusters should be introduced in separate lessons to avoid confusion.

The point is that the order of introduction should be logical and consistent with the rate at which children can learn. Furthermore, the sound-letter relationships chosen for early introduction should permit children to work with words as soon as possible. Many teachers use a combination of instructional methods rather than just one. Research suggests that explicit, teacher-directed instruction is more effective in teaching the alphabetic principle than is less-explicit and less-direct instruction.

Furthermore, the sound-letter relationships chosen for early introduction should permit children to work with words as soon as possible. Many teachers use a combination of instructional methods rather than just one. Research suggests that explicit, teacher-directed instruction is more effective in teaching the alphabetic principle than is less-explicit and less-direct instruction.

Guidelines for rate and sequence of introduction

The literacy program:

- Recognizes that children learn sound-letter relationships at different rates.

- Introduces sound-letter relationships at a reasonable pace, in a range from two to four letter-sound relationships a week.

- Teaches high-utility letter-sound relationships early.

- Introduces consonants and vowels in a sequence that permits the children to read words quickly.

- Avoids the simultaneous introduction of auditorially or visually similar sounds and letters.

- Introduces single consonant sounds and consonant blends/clusters in separate lessons.

- Provides blending instruction with words that contain the letter-sound relation.

Video: The Alphabetic Principle

In Houston, the teacher of an advanced kindergarten class connects letters and sounds in a systematic and explicit way.

Correction of dyslexia. How does reading instructions change the brain? — Logoprofy.ru

New advances in brain imaging technology are helping scientists figure out what happens in the brain when children read. By comparing images of children who are known to have difficulty reading with images of children who are strong readers, researchers are learning more about how to help children overcome reading problems. In addition, images that show what happens to children's brains before and after systematic, research-based learning to read show that the right teaching methods can normalize brain function and thus improve a child's reading skills.

According to the National Center for Learning Problems, one in five children has a significant reading disability. Reading disorders, which affect boys and girls equally, can cause difficulties at school and into adulthood. According to the International Dyslexia Association, the most common reading disorder, dyslexia, affects approximately 13–14% of the school-age population.

Many children with reading disabilities have trouble with a process called "decoding"—essentially figuring out the different sounds assigned to different letters and applying those letter-sound relationships correctly to pronounce written words. At the first stage of scientific research in the field of reading, experts hypothesized that the difficulties with deciphering were caused by a problem in the brain and were related to sound rather than sight. Brain studies have supported this hypothesis, joining other psychological studies to establish that dyslexia does not reflect vision problems or decreased intelligence.

Video lectures and tutorials on dyslexia correction!

Psychologists are now learning more about what happens in the brain while reading and are testing whether certain types of reading instructions can change the brain.

Sally Scheivitz, M.D., and Bennett Scheivitz, M.D., of Yale University, showed that when children with no reading problems tried to distinguish similar spoken syllables, speech areas in the left brain worked much harder than corresponding areas in the right brain. But when children with reading problems made the same attempt, those parts of the right brain worked harder, going into overdrive after a short delay. In a 2004 study, the Schiwitz found that when dyslexic second and third grade students learned to read through an experimental eight-month intervention, these critical left hemisphere areas became active, more like the brains of normal readers.

In a 2005 study, Panagiatos Simos, MD, of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at Houston, used a technology called magnetic imaging (MSI) to compare patterns of brain activity in children with good or poor pre-reading skills. Then they followed the children to the first grade. The images showed that children who became proficient readers by the end of first grade had effective brain activation patterns for reading as early as kindergarten. Children who had a good start with reading skills showed different patterns. However, 13 out of 16 children with reading difficulties responded to systematic reading instruction. After a year of direct instruction in "alphabet principle" (how letters work together to make words), comprehension (the meaning of words), and fluency (reading words aloud accurately), students with previous reading difficulties became average readers. What's more, the MSI images showed that over the course of first grade, children's brains began to bring critical reading areas - areas they hadn't used before - into the reading process.

Then they followed the children to the first grade. The images showed that children who became proficient readers by the end of first grade had effective brain activation patterns for reading as early as kindergarten. Children who had a good start with reading skills showed different patterns. However, 13 out of 16 children with reading difficulties responded to systematic reading instruction. After a year of direct instruction in "alphabet principle" (how letters work together to make words), comprehension (the meaning of words), and fluency (reading words aloud accurately), students with previous reading difficulties became average readers. What's more, the MSI images showed that over the course of first grade, children's brains began to bring critical reading areas - areas they hadn't used before - into the reading process.

More recently, scientists have discovered that brain activity is not the only thing that differs between children who read well and those who have difficulty reading. For example, Guinevere Eden, Ph.D. at Georgetown University, and colleagues found that dyslexic children don't just have different levels of activity in certain areas of the brain; they also show the worst connectivity between brain regions. And that connection could improve with focused reading of the instructions, they found. Researchers at the University of Washington, meanwhile, used brain imaging to show that children with dyslexia have an increase in their brain's gray matter - the body of brain cells - after intensive reading training. An increase in gray matter volume was consistent with improved reading.

For example, Guinevere Eden, Ph.D. at Georgetown University, and colleagues found that dyslexic children don't just have different levels of activity in certain areas of the brain; they also show the worst connectivity between brain regions. And that connection could improve with focused reading of the instructions, they found. Researchers at the University of Washington, meanwhile, used brain imaging to show that children with dyslexia have an increase in their brain's gray matter - the body of brain cells - after intensive reading training. An increase in gray matter volume was consistent with improved reading.

Other studies have found brain differences between children who respond to reading and those who do not. For example, in 2007, Simos' team used MSI to test brain activation in 15 first graders with severe reading disabilities who were not progressing despite quality reading instruction. The children received intensive training that focused on skills such as phonological decoding (figuring out how to pronounce a word) and rapid word recognition. Eight children showed a significant improvement in reading ability, and the MSI results confirmed that their brains began to function more than "normal" readers. The seven children who did not improve their reading skills also failed to show "normalizing" changes in their brains.

Eight children showed a significant improvement in reading ability, and the MSI results confirmed that their brains began to function more than "normal" readers. The seven children who did not improve their reading skills also failed to show "normalizing" changes in their brains.

Studies also show that improvements from reading the instructions persist. A 2008 study found that compared to good readers, poor fifth grade readers have lower activity in an area of the brain called the parietal cortex. After intensive training, poor readers showed increased activity in some parts of this region. One year after the intervention, this activity continued to increase, leading to normal levels of brain activation.

The Importance of Research in Correcting Dyslexia

Reading research has advanced significantly over the past 30 years and has accelerated in the last decade as intervention researchers collaborate with brain imaging researchers. Over the past three decades, many studies have confirmed that reading difficulties are often caused by specific differences in the way children process information.

Using brain imaging to study reading, psychologists and their colleagues in medicine and education found a biological explanation for 2004, finding that research-based learning can significantly improve how dyslexic students read and write. The researchers also found evidence that effective training improves brain function.

Equally promising is research showing that children who may otherwise have trouble learning to read can be identified early and trained before their reading problems become apparent. With targeted interventions, their brains can change in as little as a year. The news is reassuring: Most children who are at risk of reading problems can still learn to read.

Application

Research has highlighted the importance of quality teaching in the fundamentals of reading: comprehension, phonological understanding, alphabetical principle, and rules of spelling and writing. Children in early kindergarten, if not younger, should be screened to determine their risk of reading difficulties, and research-based education programs should be included in the primary school curriculum. A child who is at risk may need more intensive training, but the sooner the better.

A child who is at risk may need more intensive training, but the sooner the better.

Research cited and further reading

Blachman , BA (1994). What we learned from longitudinal studies of phonological processing and reading and some unanswered questions. Journal of Obstacle Studies, 27 (5), 287.

Blachman, BA, Fletcher, JM, Schatschneider, C., Francis, DJ, Clonan, SM, Shaywitz, BA, Shaywitz, SE (2004). Impact of intensive reading correction for second and third grade students and 1 year follow-up. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96 (3), 444-461.

Breyer, J.I., Simos, P.G., Fletcher, J.M., Castillo, E.M., Zhang, W., and Papanicolaou, A.C. (2003). Abnormal activation of the temporoparietal language areas during phonetic analysis in children with dyslexia. Neuropsychology, 17 (4), 610-621.

Forman B., Fletcher J. & Francis D. (1997). A scientific approach to teaching reading. Learning Obstacles Online.

Krafnik, AJ, Flowers, DL, Napoliello, EM, and Eden, GF (2011). Gray matter volume changes after reading reading in children with dyslexia. NeuroImage, 57 (3), 733-741.

Meyler A., Keller T.A., Cherkassky V.L., Gabrieli D.J., Just M.A. (2008). Modification of brain activation of poor readers during sentence comprehension with extended remedial instruction: a longitudinal study of neuroplasticity. Neuropsychology, 46 (10), 2580-2592.

NICHD Research Program on Reading Development, Disorders and Learning (1999). National Center for the Education of the Disabled. Received since http://www.ncld.org/students-disabilities/ld-education-teachers/nichd-research-program-reading-development-disorders-instruction

Richards T.L., Berninger V.V. (2008). Impaired communication with MRI in dyslexic children during a phonemic task: before but not after treatment. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 21 (4) 294-304.

B. A. Shaivitz, S. E. Shaivitz, B. A. Blachman, K. R. Pugh, R. K. Fulbright, P. Skudlarsky, et al. (2004). Development of the left occipitotemporal system for qualified reading in children after phonological intervention. Biological Psychiatry , 55, 926-933.

A. Shaivitz, S. E. Shaivitz, B. A. Blachman, K. R. Pugh, R. K. Fulbright, P. Skudlarsky, et al. (2004). Development of the left occipitotemporal system for qualified reading in children after phonological intervention. Biological Psychiatry , 55, 926-933.

Schewitz, SE (1996, Nov.). Dyslexia. Scientific American , 77-83.

Shaywitz, SE (2003). Overcoming Dyslexia: A new and complete scientific program to solve reading problems at any level. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Simos, PG, Fletcher, JM, Sarkari, S., Billingsley, RL, Castillo, EM, Pataraia, E., Francis, DJ, Denton, C., Papanicolauo, AC (2005). Early development of neurophysiological processes associated with normal reading and reading disorders: A study of a magnetic image source. Neuropsychology, 19 (6) 787-798.

Methods for teaching preschoolers to read | News

- Home→

- News→

- Methods for teaching preschoolers to read

Parents, wanting to develop their child, often immediately after giving up diapers begin to teach their child to read. Many manuals have been published about various methods, and parents are discussing on the net about the best method that brought success to their baby.

Many manuals have been published about various methods, and parents are discussing on the net about the best method that brought success to their baby.

Each of the methods of teaching reading has both positive and negative aspects, it remains to weigh everything and choose the most suitable for you.

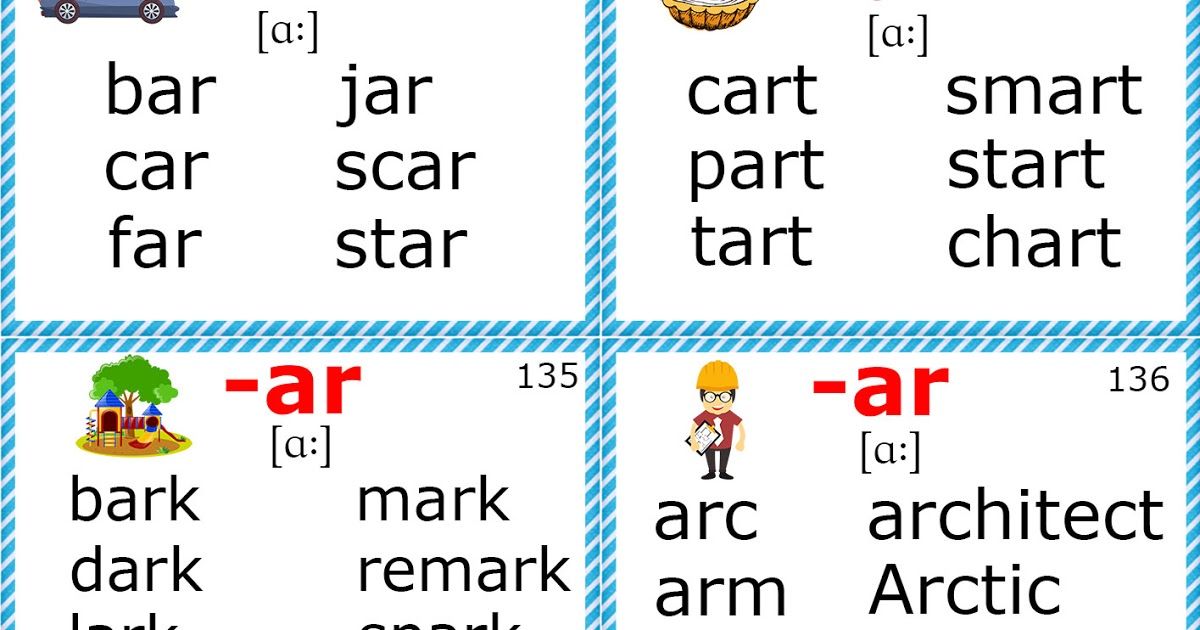

The use of the sound (phonetic) method has been known since the Soviet school. It is based on the alphabetical principle; the child, learning to pronounce letters and sounds, gradually moves to syllables, and then to words.

The advantage of the method is that the child will not be "relearned" at school, and the principle is 100% clear to parents. Speech therapists are very fond of the method, because, by doing it systematically, children get rid of speech defects. Any place is suitable for training, no need to spend money on benefits.

However, there are still more minuses: it is not suitable until 5-6 years old, the child has not yet reached the level of development necessary for perception, at first he will not understand what he is reading, this will come later.

Cubes and cards

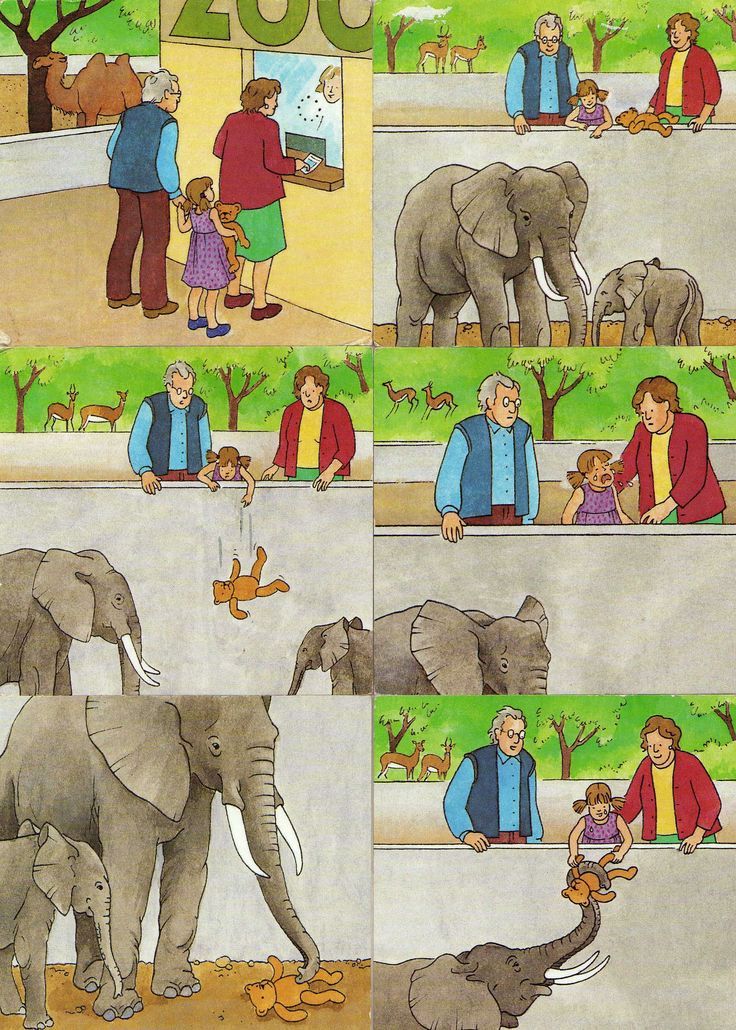

Zaitsev's Cubes imply learning to read in syllables, letter pairs in different combinations. For children, such training resembles a game, they move a lot, perform tasks with enthusiasm, this is an absolute plus. Kids quickly comprehend the structure and logic of words, moreover, there are no combinations of letters on the cubes that are not found in the Russian language. You can use Zaitsev's cubes from the age of 1, the author himself guarantees the success of his technique from any age.

The positive influence of cubes on the development of fine motor skills, and, as a result, the general development of intelligence, was noted. Of the minuses - "swallowing" endings, difficulties with the perception of the composition of the word, since only warehouses are familiar and nothing more.

It is not easy for a child in elementary school, especially with the phonemic analysis of a word. Also, the child looks for combinations of BE, VE, GE familiar from cubes in words, but there are practically none in Russian. The price of Zaitsev's allowances is quite high, the cubes are short-lived, often the kids just crumple them.

The price of Zaitsev's allowances is quite high, the cubes are short-lived, often the kids just crumple them.

Doman cards teach children to recognize whole words without dividing them into syllables or letters. Plus - training from 6 months, development of phenomenal memory, ability to analyze. The main disadvantage is the complexity, the cards must be made by yourself, and every day show them dozens of times to the baby. The school simply will not, especially in the robbery of the word.

The Montessori method

The Montessori method is as follows: children first write letters using special inserts, and only then study them. The kid repeats the sound after the adults and circles the letter with his finger. Many pluses: children are interested and fun, children begin to read without dividing words into syllables, quite quickly. Logic, ability to analyze, motor skills of hands develop.

The disadvantages are enormous time and material costs, each lesson must be carefully prepared, and materials and manuals are very expensive. The technique is best used in kindergarten, it will be difficult for a mother at home alone.

The technique is best used in kindergarten, it will be difficult for a mother at home alone.

An interesting article? Share it with others:

-

08/23/2021

Sociometry Grade 5 - methodology for conducting

-

01/04/2021

English - Vereshchagina's method

-

09/14/2020

Lozanov's method for learning English

-

09/07/2020

English - Vereshchagin's method

-

08/31/2020

Dmitry Petrov’s method for learning English

-

01/31/2022

How to choose a tutor for distance learning

-

24.

Learn more