Teaching children how to read and write

9 Fun and Easy Tips

With the abundance of information out there, it can seem like there is no clear answer about how to teach a child to read. As a busy parent, you may not have time to wade through all of the conflicting opinions.

That’s why we’re here to help! There are some key elements when it comes to teaching kids to read, so we’ve rounded up nine effective tips to help you boost your child’s reading skills and confidence.

These tips are simple, fit into your lifestyle, and help build foundational reading skills while having fun!

Tips For How To Teach A Child To Read

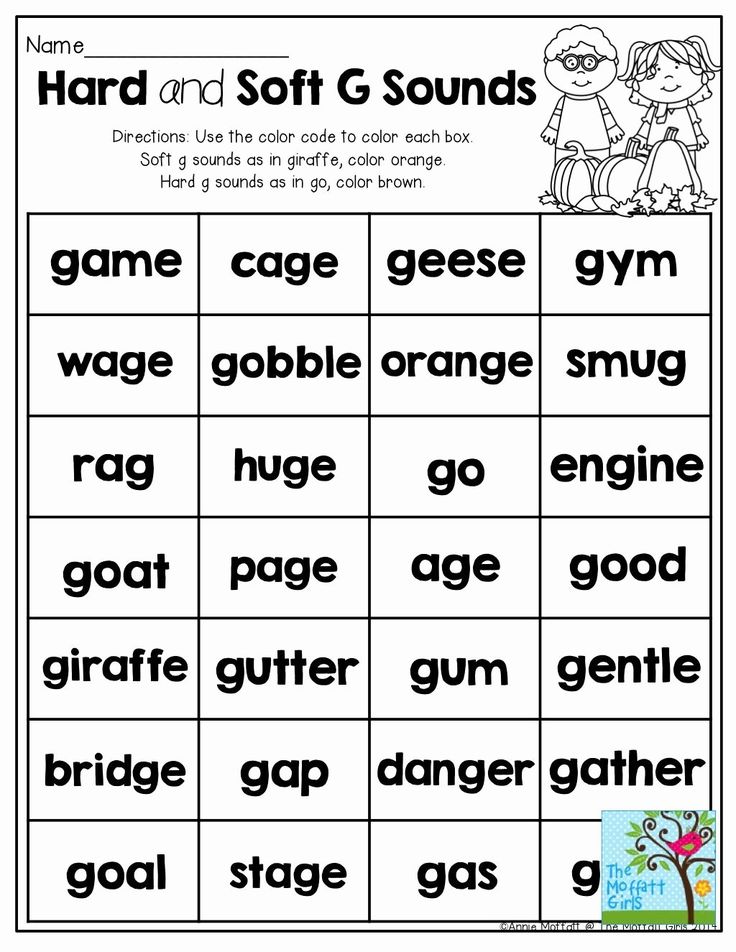

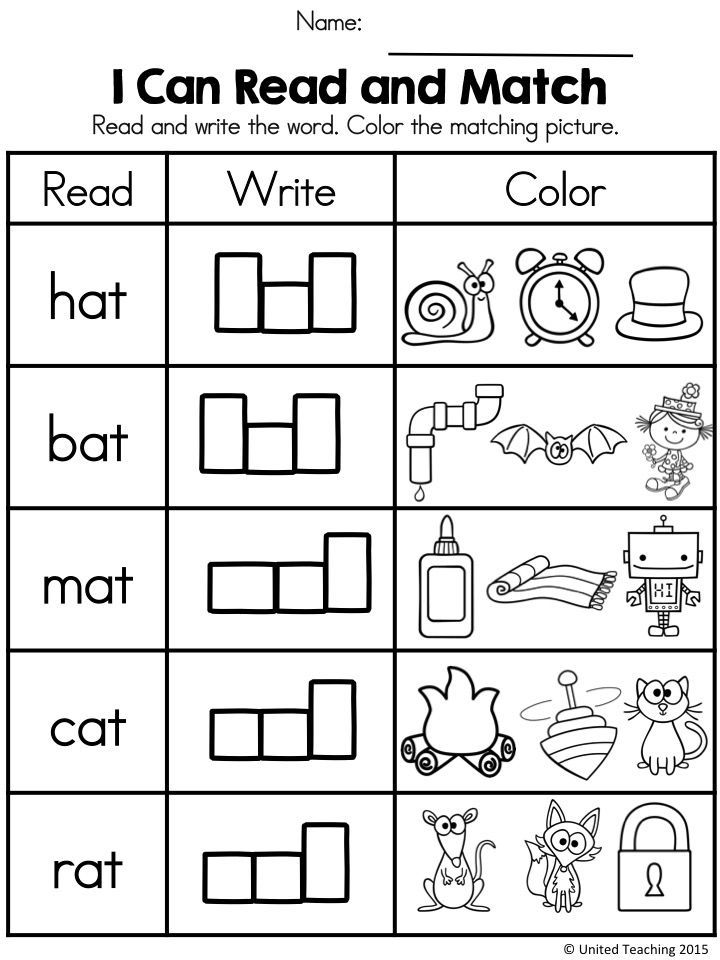

1) Focus On Letter Sounds Over Letter Names

We used to learn that “b” stands for “ball.” But when you say the word ball, it sounds different than saying the letter B on its own. That can be a strange concept for a young child to wrap their head around!

Instead of focusing on letter names, we recommend teaching them the sounds associated with each letter of the alphabet. For example, you could explain that B makes the /b/ sound (pronounced just like it sounds when you say the word ball aloud).

Once they firmly establish a link between a handful of letters and their sounds, children can begin to sound out short words. Knowing the sounds for B, T, and A allows a child to sound out both bat and tab.

As the number of links between letters and sounds grows, so will the number of words your child can sound out!

Now, does this mean that if your child already began learning by matching formal alphabet letter names with words, they won’t learn to match sounds and letters or learn how to read? Of course not!

We simply recommend this process as a learning method that can help some kids with the jump from letter sounds to words.

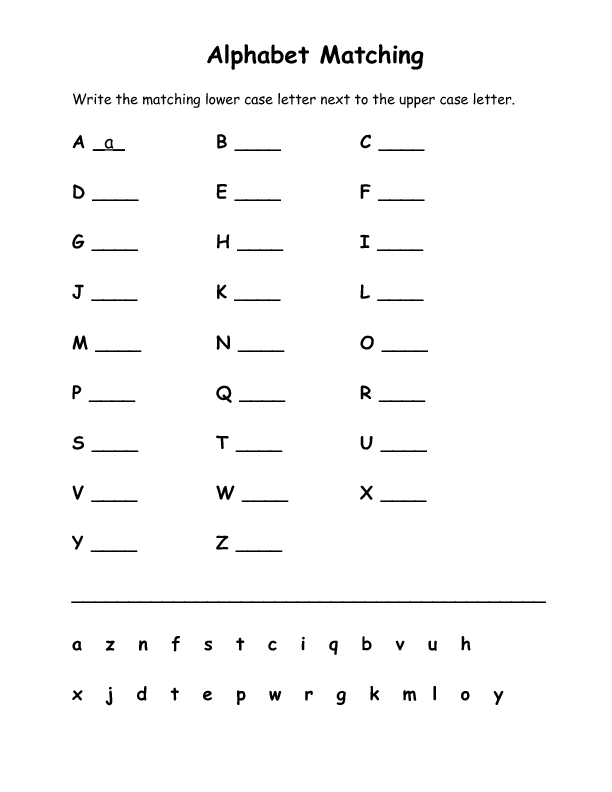

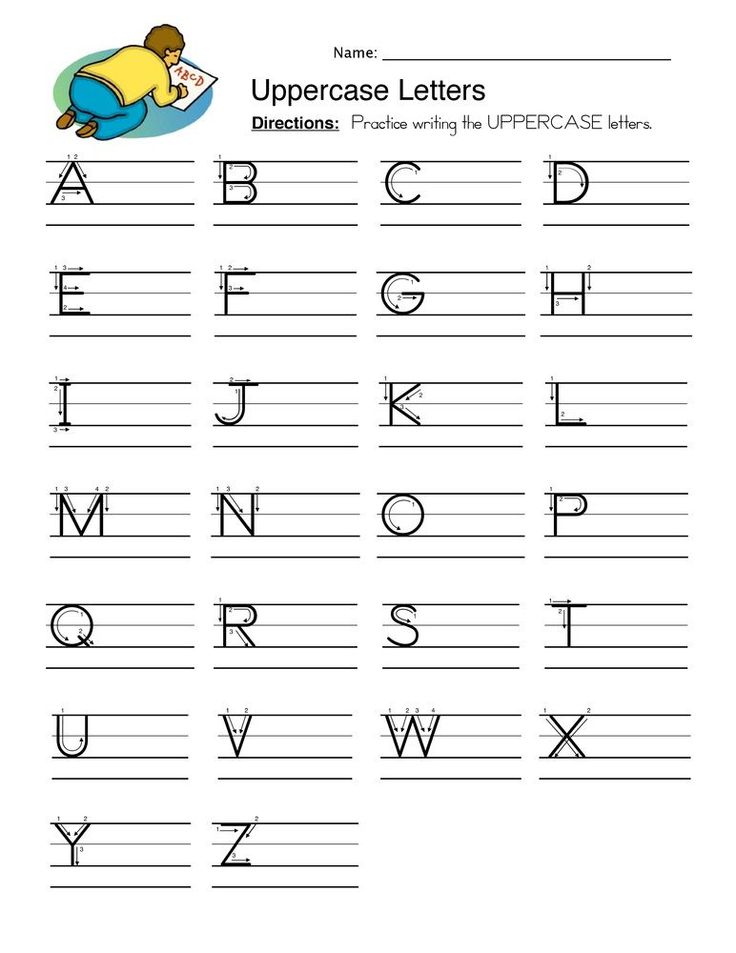

2) Begin With Uppercase Letters

Practicing how to make letters is way easier when they all look unique! This is why we teach uppercase letters to children who aren’t in formal schooling yet.

Even though lowercase letters are the most common format for letters (if you open a book at any page, the majority of the letters will be lowercase), uppercase letters are easier to distinguish from one another and, therefore, easier to identify.

Think about it –– “b” and “d” look an awful lot alike! But “B” and “D” are much easier to distinguish. Starting with uppercase letters, then, will help your child to grasp the basics of letter identification and, subsequently, reading.

To help your child learn uppercase letters, we find that engaging their sense of physical touch can be especially useful. If you want to try this, you might consider buying textured paper, like sandpaper, and cutting out the shapes of uppercase letters.

Ask your child to put their hands behind their back, and then place the letter in their hands. They can use their sense of touch to guess what letter they’re holding! You can play the same game with magnetic letters.

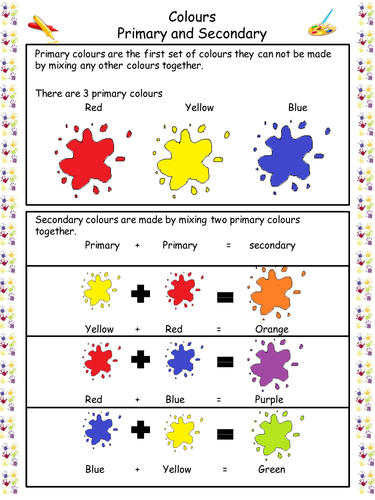

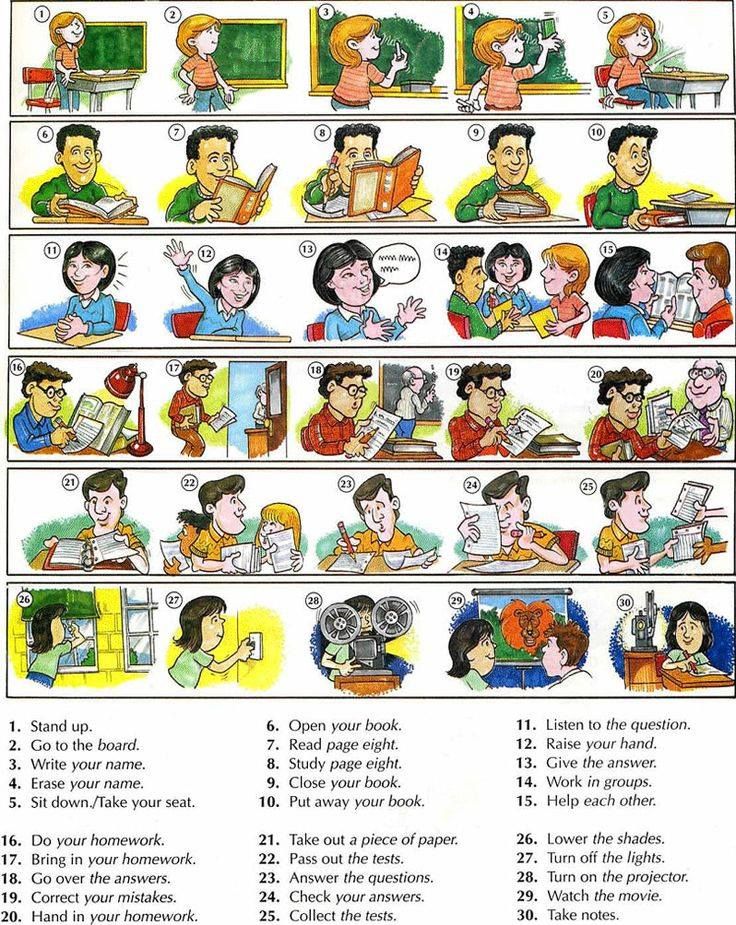

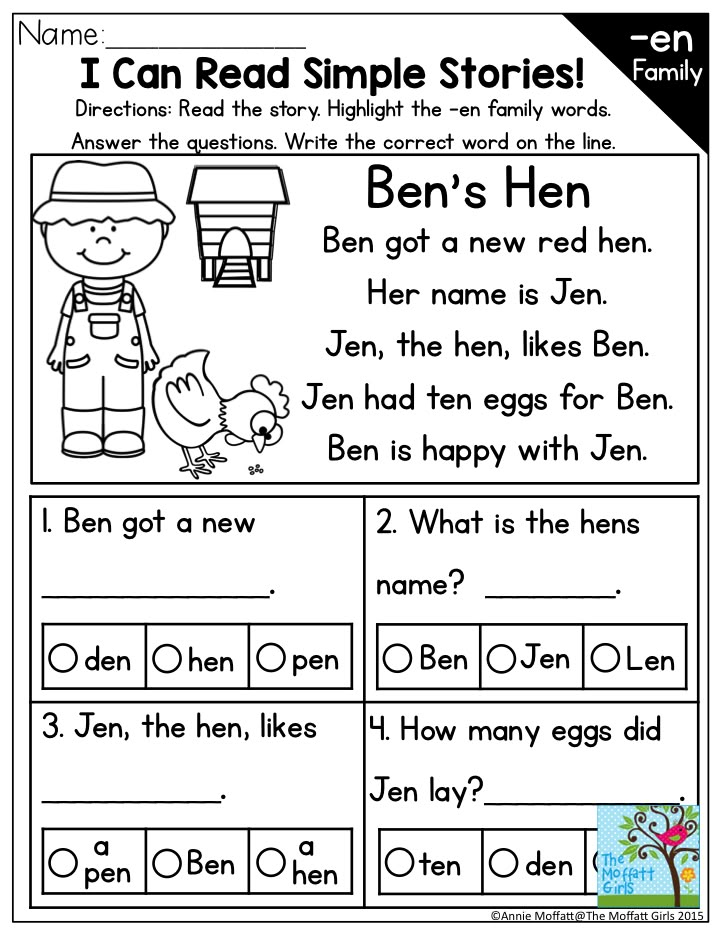

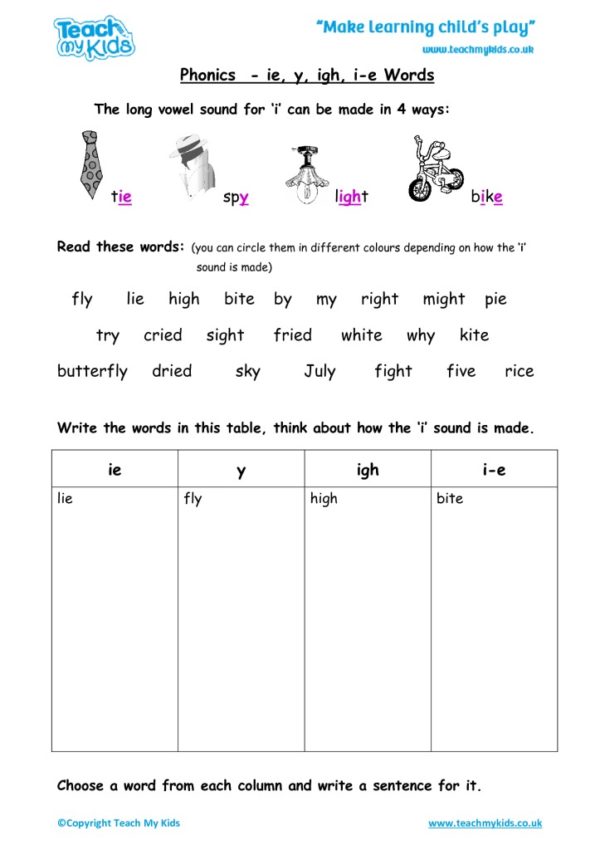

3) Incorporate Phonics

Research has demonstrated that kids with a strong background in phonics (the relationship between sounds and symbols) tend to become stronger readers in the long-run.

A phonetic approach to reading shows a child how to go letter by letter — sound by sound — blending the sounds as you go in order to read words that the child (or adult) has not yet memorized.

Once kids develop a level of automatization, they can sound out words almost instantly and only need to employ decoding with longer words. Phonics is best taught explicitly, sequentially, and systematically — which is the method HOMER uses.

If you’re looking for support helping your child learn phonics, our HOMER Learn & Grow app might be exactly what you need! With a proven reading pathway for your child, HOMER makes learning fun!

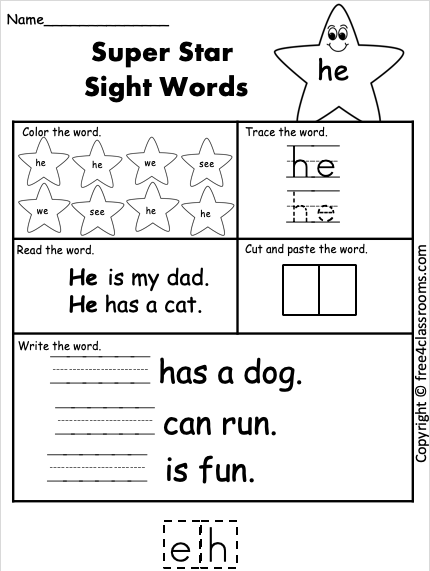

4) Balance Phonics And Sight Words

Sight words are also an important part of teaching your child how to read. These are common words that are usually not spelled the way they sound and can’t be decoded (sounded out).

Because we don’t want to undo the work your child has done to learn phonics, sight words should be memorized. But keep in mind that learning sight words can be challenging for many young children.

So, if you want to give your child a good start on their reading journey, it’s best to spend the majority of your time developing and reinforcing the information and skills needed to sound out words.

5) Talk A Lot

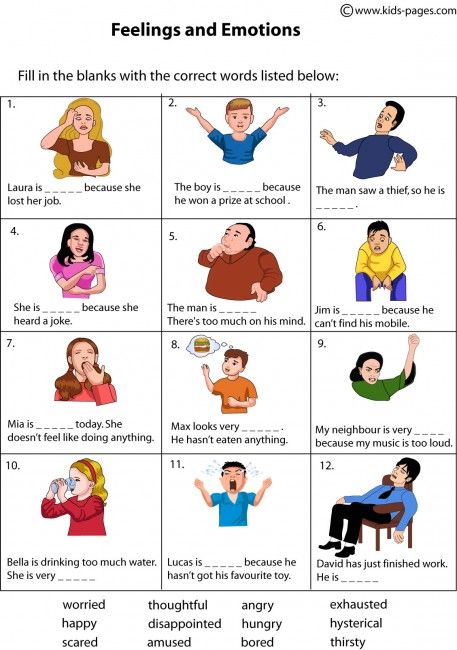

Even though talking is usually thought of as a speech-only skill, that’s not true. Your child is like a sponge. They’re absorbing everything, all the time, including the words you say (and the ones you wish they hadn’t heard)!

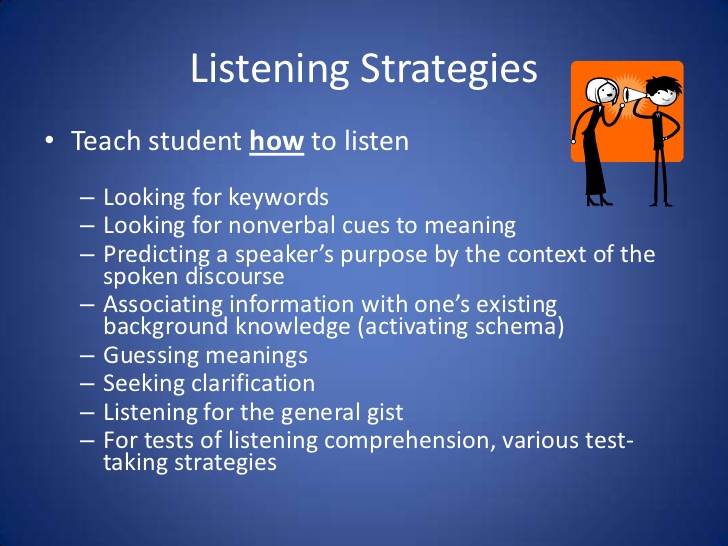

Talking with your child frequently and engaging their listening and storytelling skills can increase their vocabulary.

It can also help them form sentences, become familiar with new words and how they are used, as well as learn how to use context clues when someone is speaking about something they may not know a lot about.

All of these skills are extremely helpful for your child on their reading journey, and talking gives you both an opportunity to share and create moments you’ll treasure forever!

6) Keep It Light

Reading is about having fun and exploring the world (real and imaginary) through text, pictures, and illustrations. When it comes to reading, it’s better for your child to be relaxed and focused on what they’re learning than squeezing in a stressful session after a long day.

We’re about halfway through the list and want to give a gentle reminder that your child shouldn’t feel any pressure when it comes to reading — and neither should you!

Although consistency is always helpful, we recommend focusing on quality over quantity. Fifteen minutes might sound like a short amount of time, but studies have shown that 15 minutes a day of HOMER’s reading pathway can increase early reading scores by 74%!

It may also take some time to find out exactly what will keep your child interested and engaged in learning. That’s OK! If it’s not fun, lighthearted, and enjoyable for you and your child, then shake it off and try something new.

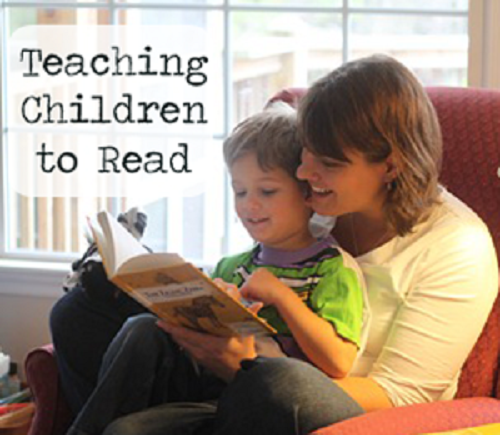

7) Practice Shared Reading

While you read with your child, consider asking them to repeat words or sentences back to you every now and then while you follow along with your finger.

There’s no need to stop your reading time completely if your child struggles with a particular word. An encouraging reminder of what the word means or how it’s pronounced is plenty!

Another option is to split reading aloud time with your child. For emerging readers, you can read one line and then ask them to read the next. For older children, reading one page and letting them read the next page is beneficial.

For emerging readers, you can read one line and then ask them to read the next. For older children, reading one page and letting them read the next page is beneficial.

Doing this helps your child feel capable and confident, which is important for encouraging them to read well and consistently!

This technique also gets your child more acquainted with the natural flow of reading. While they look at the pictures and listen happily to the story, they’ll begin to focus on the words they are reading and engage more with the book in front of them.

Rereading books can also be helpful. It allows children to develop a deeper understanding of the words in a text, make familiar words into “known” words that are then incorporated into their vocabulary, and form a connection with the story.

We wholeheartedly recommend rereading!

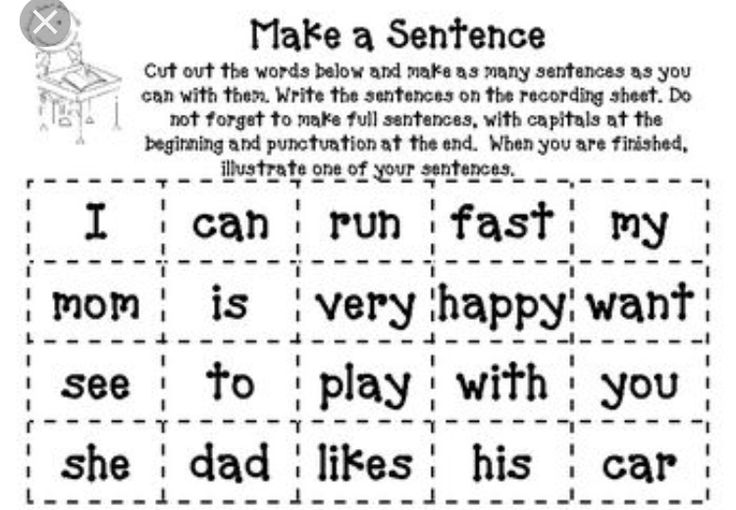

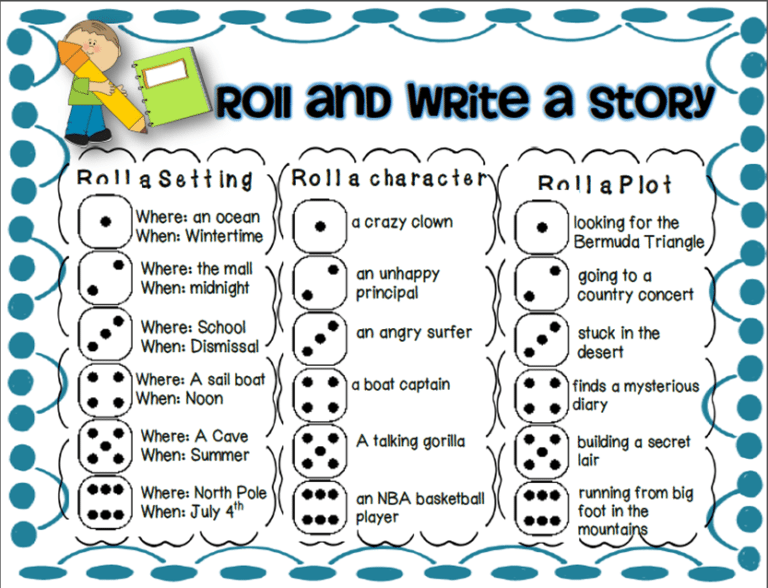

8) Play Word Games

Getting your child involved in reading doesn’t have to be about just books. Word games can be a great way to engage your child’s skills without reading a whole story at once.

One of our favorite reading games only requires a stack of Post-It notes and a bunched-up sock. For this activity, write sight words or words your child can sound out onto separate Post-It notes. Then stick the notes to the wall.

Your child can then stand in front of the Post-Its with the bunched-up sock in their hands. You say one of the words and your child throws the sock-ball at the Post-It note that matches!

9) Read With Unconventional Materials

In the same way that word games can help your child learn how to read, so can encouraging your child to read without actually using books!

If you’re interested in doing this, consider using PlayDoh, clay, paint, or indoor-safe sand to form and shape letters or words.

Another option is to fill a large pot with magnetic letters. For emerging learners, suggest that they pull a letter from the pot and try to name the sound it makes. For slightly older learners, see if they can name a word that begins with the same sound, or grab a collection of letters that come together to form a word.

As your child becomes more proficient, you can scale these activities to make them a little more advanced. And remember to have fun with it!

Reading Comes With Time And Practice

Overall, we want to leave you with this: there is no single answer to how to teach a child to read. What works for your neighbor’s child may not work for yours –– and that’s perfectly OK!

Patience, practicing a little every day, and emphasizing activities that let your child enjoy reading are the things we encourage most. Reading is about fun, exploration, and learning!

And if you ever need a bit of support, we’re here for you! At HOMER, we’re your learning partner. Start your child’s reading journey with confidence with our personalized program plus expert tips and learning resources.

Author

Teaching children to read isn’t easy. How do kids actually learn to read?

A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger Report

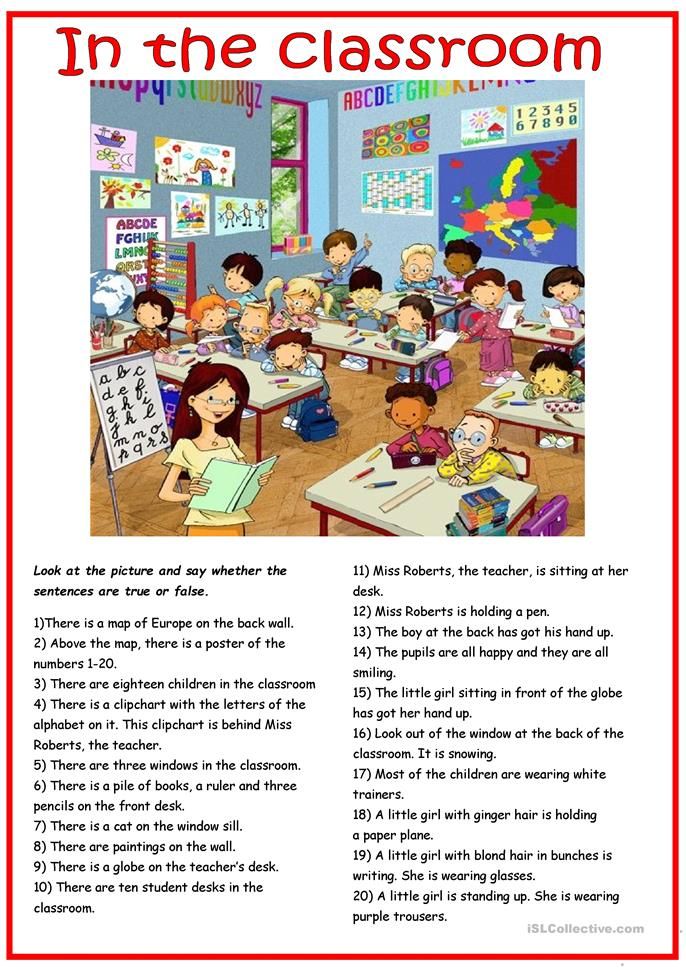

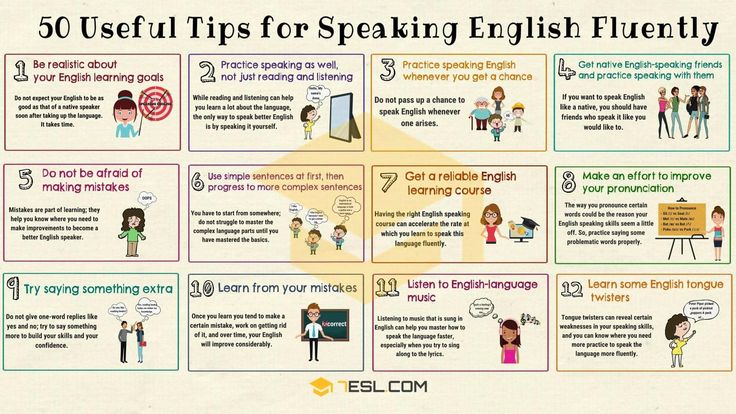

Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger ReportTeaching kids to read isn’t easy; educators often feel strongly about what they think is the “right” way to teach this essential skill. Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

How do kids actually learn how to read?

Research shows kids learn to read when they are able to identify letters or combinations of letters and connect those letters to sounds. There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

If children can’t master phonics, they are more likely to struggle to read. That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

How should your child’s school teach reading?

Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on reading instruction, said phonics are important in kindergarten through second grade and phonemic awareness should be explicitly taught in kindergarten and first grade. This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

The wars over how to teach reading are back. Here’s the four things you need to know.

Wiley Blevins, an author and expert on phonics, said a good test parents can use to determine whether a child is receiving research-based reading instruction is to ask their child’s teacher how reading is taught. “They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

“Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

Rasmussen’s school uses a structured approach: Children receive lessons in phonemic awareness, phonics, pre-writing and writing, vocabulary and repeated readings. Research shows this type of “systematic and intensive” approach in several aspects of literacy can turn children who struggle to read into average or above-average readers.

What should schools avoid when teaching reading?

Educators and experts say kids should be encouraged to sound out words, instead of guessing. “We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

“When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

Related: Teacher Voice: We need phonics, along with other supports, for reading

Blevins and Shanahan caution against organizing books by different reading levels and keeping students at one level until they read with enough fluency to move up to the next level. Although many people may think keeping students at one level will help prevent them from getting frustrated and discouraged by difficult texts, research shows that students actually learn more when they are challenged by reading materials.

Blevins said reliance on “leveled books” can contribute to “a bad habit in readers.” Because students can’t sound out many of the words, they rely on memorizing repeated words and sentence patterns, or on using picture clues to guess words. Rasmussen said making kids stick with one reading level — and, especially, consistently giving some kids texts that are below grade level, rather than giving them supports to bring them to grade level — can also lead to larger gaps in reading ability.

How do I know if a reading curriculum is effective?

Some reading curricula cover more aspects of literacy than others. While almost all programs have some research-based components, the structure of a program can make a big difference, said Rasmussen. Watching children read is the best way to tell if they are receiving proper instruction — explicit, systematic instruction in phonics to establish a foundation for reading, coupled with the use of grade-level texts, offered to all kids.

Parents who are curious about what’s included in the curriculum in their child’s classroom can find sources online, like a chart included in an article by Readingrockets.org which summarizes the various aspects of literacy, including phonics, writing and comprehension strategies, in some of the most popular reading curricula.

Blevins also suggested some questions parents can ask their child’s teacher:

- What is your phonics scope and sequence?

“If research-based, the curriculum must have a clearly defined phonics scope and sequence that serves as the spine of the instruction. ” Blevins said.

” Blevins said.

- Do you have decodable readers (short books with words composed of the letters and sounds students are learning) to practice phonics?

“If no decodable or phonics readers are used, students are unlikely to get the amount of practice and application to get to mastery so they can then transfer these skills to all reading and writing experiences,” Blevins said. “If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

- What are you doing to build students’ vocabulary and background knowledge? How frequent is this instruction? How much time is spent each day doing this?

“It should be a lot,” Blevins said, “and much of it happens during read-alouds, especially informational texts, and science and social studies lessons. ”

”

- Is the research used to support your reading curriculum just about the actual materials, or does it draw from a larger body of research on how children learn to read? How does it connect to the science of reading?

Teachers should be able to answer these questions, said Blevins.

What should I do if my child isn’t progressing in reading?

When a child isn’t progressing, Blevins said, the key is to find out why. “Is it a learning challenge or is your child a curriculum casualty? This is a tough one.” Blevins suggested that parents of kindergarteners and first graders ask their child’s school to test the child’s phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency.

Parents of older children should ask for a test of vocabulary. “These tests will locate some underlying issues as to why your child is struggling reading and understanding what they read,” Blevins said. “Once underlying issues are found, they can be systematically addressed. ”

”

“We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs. But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York

Rasmussen recommended parents work with their school if they are concerned about their children’s progress. By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

“Teachers aren’t there doing necessarily bad things or disadvantaging kids purposefully or willfully,” Rasmussen said. “You have many great reading teachers using some effective strategies and some ineffective strategies.”

What can parents do at home to help their children learn to read?

Parents want to help their kids learn how to read but don’t want to push them to the point where they hate reading. “Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

“Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

- Challenge kids to find everything in the house that starts with a specific sound.

- Stretch out one word in a sentence. Ask your child to “pass the salt” but say the individual sounds in the word “salt” instead of the word itself.

- Ask your child to figure out what every family member’s name would be if it started with a “b” sound.

- Sing that annoying “Banana fana fo fanna song.” Jiban said that kind of playful activity can actually help a kid think about the sounds that correspond with letters even if they’re not looking at a letter right in front of them.

- Read your child’s favorite book over and over again. For books that children know well, Jiban suggests that children use their finger to follow along as each word is read. Parents can do the same, or come up with another strategy to help kids follow which words they’re reading on a page.

Giving a child diverse experiences that seem to have nothing to do with reading can also help a child’s reading ability. By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

This story about teaching children to read was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

Teaching children to read and write

Submitted by Ilya Danshyn on Mon, 11/15/2021 - 14:31

Learning to read and write

Talking, singing, playing with sounds and words, reading, writing and drawing with your child are all great ways to create a good foundation for your child to read and write in the future.

Regular daily activities at home or occasional activities in bookstores or libraries are all excellent opportunities for children to learn to read and write. nine0003

And You don't need much time to practice reading and writing with your child - just five minutes a few times a day is enough. The key is to do it at different times and use different opportunities to help your child learn. It can be the simplest activity, such as making a shopping list, playing rhymes, or reading fairy tales before bed.

It can be the simplest activity, such as making a shopping list, playing rhymes, or reading fairy tales before bed.

It's never too early to involve your child in activities that will teach him to read and write - even babies love to hear stories and engage in conversation. The following are activities for children of all ages. If you have several young children of different ages, you can combine or change activities according to their interests and skills. nine0003

Infants, Toddlers and Preschoolers: Teaching Reading and Writing

Communication and Singing

Communication and singing with young children helps them develop their listening and speaking skills. Here are some ideas to get you started:

- Use rhyme when you get it right. Use phrases like “a little gray top will come and bite on the flank”, or make up nonsense rhymes about what you are doing, for example: “I’ll cook this beauty for the cat.” nine0027

- Sing traditional nursery rhymes to your child.

Thanks to them, the baby begins to understand what language, rhyme, repetition and rhythm are. Think back to something you heard as a child, no matter what language.

Thanks to them, the baby begins to understand what language, rhyme, repetition and rhythm are. Think back to something you heard as a child, no matter what language. - If you have a baby, repeat the sounds he makes, or make up sounds and see if he can repeat them. For example: “Cows say “mu-u-u-u”. Can you say "moo-o-o-o"?

- While eating, talk about the meals you have cooked, what you have done with the food, what the food tastes like and looks like. nine0027

- Talk about what's going on outside: how the leaves rustle, the birds sing, or the noise of the cars. Ask your child if they can mimic the sounds that wind, rain, water, planes, trains, and cars make.

- Play "I am a spy" to guess the colors. This can be a lot of fun, especially for preschoolers. For example: “I am a spy, and I look secretly and see something green. What green can I look at?

Reading and studying with books

Even in toddlers, reading aloud develops vocabulary, listening and understanding skills, and forms the basis for further development of the ability to connect sounds and words. Your child may like:

Your child may like:

- Read books that have rhyme, rhythm and repetition.

- Turn the pages and talk about what he sees (for preschool children). To guide your child's gaze, slide your finger from left to right across the page as you read and point to certain words or phrases. It is important that the child has fun. nine0027

- Flipping through books with windows that open or books that are fun to touch and feel - this activity will be especially appreciated by toddlers. Such books will help satisfy the need of toddlers to touch and explore. You can even make your own book with items your child loves to look at and touch.

- Read stories interactively. Ask, for example: “What do you think will happen next?” or “Remember when we were on the bus?” nine0027

- Correlate what is told in books with real life. For example, if you have read a book about games under a tree, you can take the child to the yard, sit it under the tree, show the leaves and branches, and play as described in the book.

- Do what you read about. For example, ask him to jump like a kangaroo from a book.

Drawing and Writing Activities

Scribble writing and drawing help young children practice the skills they will need later to develop pencil and pen skills. Toddlers and preschoolers can do the following:

- Draw and write with pens, pencils, crayons and markers. The kid will definitely want to add his own inscriptions or a bright multi-colored drawing to greeting cards or letters.

- Write some letters or your name on all the drawings the child has made: write the letters in one color and have the child circle them in another color.

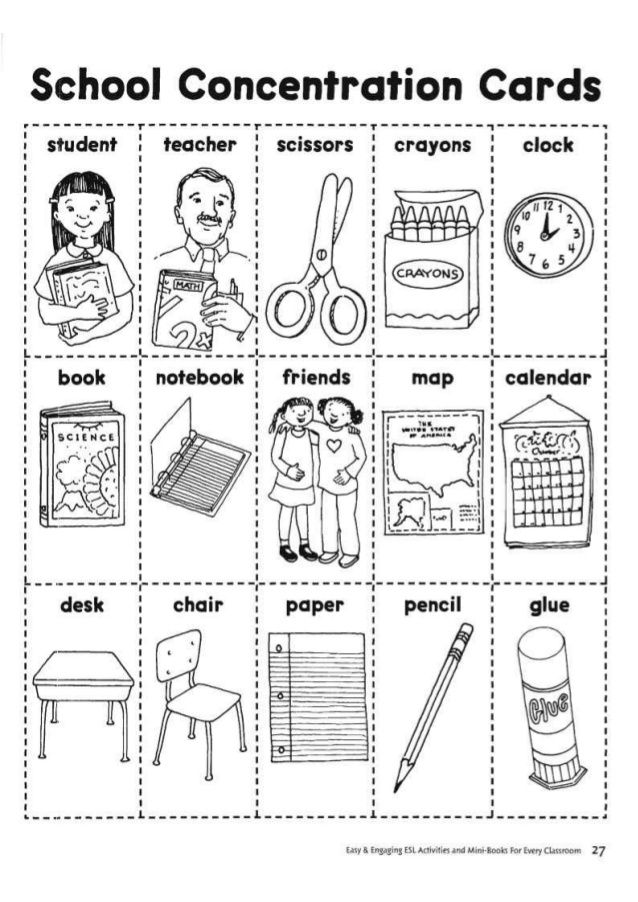

- Make letters of the alphabet or numbers from salt dough or plasticine.

- Use the letters of the alphabet in various forms - on cubes, on puzzle pieces, and magnetic letters that can be hung on a refrigerator or board. nine0027

- Cut or draw the main household items (chair, table, TV, wall, door, etc.

), then write their names on separate small pieces of paper. Ask your child to match the name of the object with its image.

), then write their names on separate small pieces of paper. Ask your child to match the name of the object with its image. - Encourage the child to talk about their drawings. Help your child write down the words he uses to describe them.

Senior preschool children: extra classes to teach reading and writing

In addition to those already listed, as school gets closer and if your child is interested, you can try the following activities: - thanks to such games, your child learns sounds. For example: “I will think of something that starts with “m”. What do you think I'm looking at that starts with that letter?"

Ask your child to tell you about what they enjoyed doing in kindergarten this week. Sometimes you can write down what the child says.

Ask your child to tell you about what they enjoyed doing in kindergarten this week. Sometimes you can write down what the child says. Reading and activities using books

- Read and talk about fairy tales. Ask the child: "What was the story about?" or “Did you like this character? Why?"

- Older children love alphabet books. Ask your child to name words that begin with the same sound as the letter you point to.

- Invite the child to make a story book with his own pictures. With your help, he can do this on a computer or using pencils and paper. If the child is interested, help him write at least a few letters in the story. nine0027

- While walking or shopping, ask your child to choose or name certain letters or words on billboards, shop signs, road signs, or items in a supermarket.

The same can be done at home with catalogs and advertising magazines.

The same can be done at home with catalogs and advertising magazines. - Sign up to the library with your child, offer him to take books home. Many libraries also host meetings and events for young readers.

Drawing and writing activities

- Ask your child to write their name and the names of other family members on greeting cards or photographs. Once your child has learned to use all the letters correctly, they are ready to learn how to write in uppercase and lowercase (capital and small) letters.

- Invite the child to write a shopping list or play "restaurant" and make a menu for him.

- Ask your child to make a book with a word on one side of the page and a picture with that word on the other. When you work with your child, help him as needed, make these activities interesting for him. nine0003

10-12 months

13–18 months

19–24 months

25–36 months

37–48 months

49–60 months

-72 months

Child Gender

Both

Parent Gender

Both

Generic Content

Off

Licensed Content

Off

Premature Content

Off

0 Mandatory Content

Fundamentals of teaching preschoolers to read and write.

| Consultation (preparatory group) on the topic:

| Consultation (preparatory group) on the topic: Fundamentals of teaching preschoolers to read and write.

The family plays an important role in shaping a person's personality. Raising your child is a great art, since the process of education itself is a continuous work of the heart, mind and will of the parents. Every day they have to look for ways to approach the child, to think about the resolution of many specific situations put forward by life. Especially many questions arise when it becomes necessary to prepare a child for school.

One of these questions makes parents think: “How to teach a child to read and write?” nine0003

Learning to read is based not on the letter, but on the sound. Before showing the child a new letter, for example M, you should teach him to hear the sound [m] in syllables and words. At first, both the sounds and the letters corresponding to them should be named the same - [m], [b], and not em or be. Speaking like this, we pronounce two sounds - [e] and [m].

It only confuses the kids. Another gross mistake is reading letter by letter, i.e. the child first names the letters: M A - and only after that he adds up the syllable itself: M A. This habit of misreading is very persistent and is corrected with great difficulty. If a child can read words of three or four letters in this way, then reading more complex words will be inaccessible. Correct reading is reading in syllables (until fluent reading is formed). At first, let the child draw the first letter of the syllable for a long time until he recognizes the next letter. The main thing is that he does not stop after the first letter, read the letters of the syllable together. First of all, children are taught to read syllables like AP, UT, IK, etc. Then they move on to syllables like MA, BUT, VU. After the skill of reading syllables is sufficiently automated, they proceed to reading words like MAC, MOON, STICK, etc. increasing word complexity. If in oral speech a child replaces some sounds, for example, [W] with [S] (“sapka”) or [R] with [L] (“lyba”), it is not recommended to learn the corresponding letters with him until the sound pronunciation is completely corrected .

It only confuses the kids. Another gross mistake is reading letter by letter, i.e. the child first names the letters: M A - and only after that he adds up the syllable itself: M A. This habit of misreading is very persistent and is corrected with great difficulty. If a child can read words of three or four letters in this way, then reading more complex words will be inaccessible. Correct reading is reading in syllables (until fluent reading is formed). At first, let the child draw the first letter of the syllable for a long time until he recognizes the next letter. The main thing is that he does not stop after the first letter, read the letters of the syllable together. First of all, children are taught to read syllables like AP, UT, IK, etc. Then they move on to syllables like MA, BUT, VU. After the skill of reading syllables is sufficiently automated, they proceed to reading words like MAC, MOON, STICK, etc. increasing word complexity. If in oral speech a child replaces some sounds, for example, [W] with [S] (“sapka”) or [R] with [L] (“lyba”), it is not recommended to learn the corresponding letters with him until the sound pronunciation is completely corrected . Otherwise, the child may form an incorrect connection between the sound and the letter denoting it. nine0003

Otherwise, the child may form an incorrect connection between the sound and the letter denoting it. nine0003 "Can parents correct their child's speech?"

Undoubtedly, it is difficult to overestimate the role of the mother or other close people in the development of the child's speech. Pay special attention to your own speech, since for children aged 1 to 6 years, the speech of their parents is a role model and the basis for subsequent speech development. It is important to adhere to the following rules:

- you can not "lisp", that is, speak in a "babble" language or distort sound pronunciation, imitating a child's speech; nine0042 - it is desirable that your speech is always clear, fairly smooth, emotionally expressive, moderate in pace;

- when communicating with a child, do not overload your speech with hard-to-pronounce words, incomprehensible expressions and turns. Phrases should be fairly simple. Before reading the book, new, unfamiliar words found in the text must not only be explained to the child in a form that is understandable to him, but also illustrated in practice;

- only specific questions should be asked, not rushed with an answer; nine0042 - the child should not be punished for mistakes in speech, mimicked or corrected irritably. It is useful to read to children poetic texts appropriate for their age. It is very important to develop auditory attention, mobility of the articulatory apparatus, fine motor skills of the hand.

It is useful to read to children poetic texts appropriate for their age. It is very important to develop auditory attention, mobility of the articulatory apparatus, fine motor skills of the hand. Before teaching a child to write, it is necessary to form the correct grip of the pen. Many kids do it wrong. The child's hands should lie on the table so that the elbow of the right hand (for right-handers) protrudes slightly beyond the edge of the table, and the hand moves freely along the line, and the left lies on the table and holds the sheet. The pen is placed on the upper part of the middle finger, and the nail phalanges of the thumb and forefinger hold it at a distance of 1.5–2 cm from the end of the rod. Teach your child to navigate on a sheet of paper: show the top right, bottom left, middle of the sheet, etc. Then they are taught to see the lines, find the beginning, end of the line. nine0003

"How to help a child if he forgets, confuses, writes letters incorrectly?"

If a child writes letters in the wrong direction (mirror), he confuses the arrangement of the elements of the letters, most often this is a consequence of unformed spatial representations. Check if your child can correctly show his right ear, left leg, etc., tell what he sees to his right, what to his left. Very useful activity games such as "Tangram", "Pythagoras", "Fold the square", various "constructors". It happens that a child confuses letters that are completely different in spelling: M and B, T and D. The reason for this may be that the child does not distinguish the corresponding sounds by ear. At the same time, his physical hearing may be absolutely normal. Teach your child to find difficult sounds in syllables, words. To make it easier for a child to memorize letters, the following techniques are recommended:

Check if your child can correctly show his right ear, left leg, etc., tell what he sees to his right, what to his left. Very useful activity games such as "Tangram", "Pythagoras", "Fold the square", various "constructors". It happens that a child confuses letters that are completely different in spelling: M and B, T and D. The reason for this may be that the child does not distinguish the corresponding sounds by ear. At the same time, his physical hearing may be absolutely normal. Teach your child to find difficult sounds in syllables, words. To make it easier for a child to memorize letters, the following techniques are recommended: - Letter coloring, hatching.

- Sculpting letters from plasticine by a child, bending letters from wire.

- A child cutting out a letter along a contour drawn by an adult.

- "Writing" with wide gestures of all the studied letters in the air.

- Comparison of the letter and its elements with familiar objects, other letters: the letter U - hare ears, etc.

- Tracing with a finger a letter cut out of fine sandpaper or velvet paper, recognizing letters by touch with eyes closed. nine0042 - Laying out letters from various materials: braid, buttons, matches, etc.

- A child's stroke of letters written by an adult.

- Writing a letter according to reference points set by an adult."Should I study before school?" This is a question parents often ask teachers. It can be answered quite definitely: yes, it is necessary. But teaching preschoolers requires special knowledge. Therefore, before you start learning, you need to prepare for this. It is better not to teach at all than to teach incorrectly and then retrain. nine0003

Teaching reading and counting, preparing a hand for writing at preschool age is best done in a playful way, since knowledge is thus better absorbed by children.

When teaching, it is important to maintain a sense of proportion. If a child knows too little, he will have to work hard at school to keep up with other children.