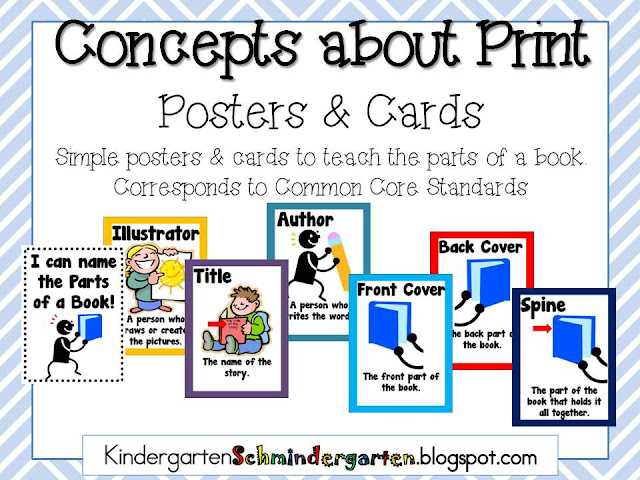

Teaching concepts about print

Concepts of Print: Ideas for Teachers

By: Michigan's Mission: Literacy

Discover 20 ways to help children learn about concepts of print — that print carries meaning, directionality in a book, letter and word awareness, upper case and lower case letters, punctuation, and more.

- Provide children with daily opportunities to participate in shared reading.

- Encourage children to bring books from home to share.

- Talk about the children’s own writing and drawings to help them.

- Model as you read that the message is in the print, demonstrating the one-to-one correspondence between spoken and written words.

- Make references to words, spaces, letters, lines of print, left to right, top to bottom, direction of print, in big books that you have read and as you model writing.

- Use environmental print to make references to words, spaces, letters and lines of print.

- Develop the concept of “left to right” by sticking a green dot on the left-hand top corner of the child’s desk to act as a reminder.

- Have children suggest where the teacher should start when transcribing stories or beginning to read their big books.

- Provide opportunities for paired reading. Ask an older student to read while a younger child follows along with his/her finger.

- Count the words in a line of print or clap for each word spoken to help develop the children’s concept of a word.

- Write a child’s news sentence onto sentence strips. Cut one sentence into individual words and encourage children to match words to the sentence strip, specifically using “first word,” “last word.”

- Use name cards, nursery rhymes, room item labels, etc., to help children recognize words that are important to them.

- Build up a bank of words frequently written or recognized by children. Display and refer to them when appropriate. Encourage children to refer to them when they are “writing.”

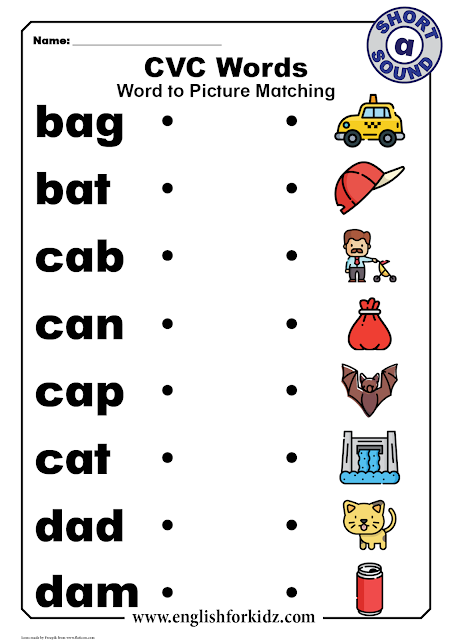

- Use a variety of incidental activities to develop the concept of letter, e.g., play with letter cars, magnetic letters, plastic letters and alphabet games.

Demonstrate and discuss that letters go together to make words.

Demonstrate and discuss that letters go together to make words. - Display an alphabet chart and talk about letters in other contexts, making sure the children can see that a letter is different from a word.

- Make available capital and lower case letters of the alphabet for children to use and manipulate.

- Model the use of conventions such as full stops, questions, pauses, etc., in context while modeling reading and writing.

- Make use of quality book and tape sets so that children can hear different interpretations of the print.

- Use elbow macaroni to “make sentences” with quotations and commas.

- Have student’s highlight (specific) punctuation.

Michigan's Mission: Literacy (2016)

Reprints

You are welcome to print copies for non-commercial use, or a limited number for educational purposes, as long as credit is given to Reading Rockets and the author(s). For commercial use, please contact the author or publisher listed.

Related Topics

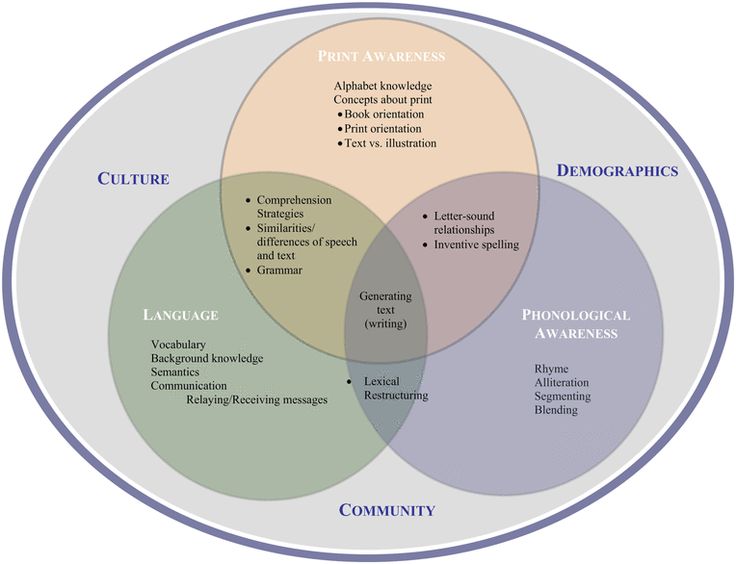

Print Awareness

New and Popular

Print-to-Speech and Speech-to-Print: Mapping Early Literacy

100 Children’s Authors and Illustrators Everyone Should Know

A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words

7 Great Ways to Encourage Your Child's Writing

Screening, Diagnosing, and Progress Monitoring for Fluency: The Details

Phonemic Activities for the Preschool or Elementary Classroom

Our Literacy Blogs

Shared Reading in the Structured Literacy Era

Kids and educational media

Meet Ali Kamanda and Jorge Redmond, authors of Black Boy, Black Boy: Celebrating the Power of You

Get Widget |

Subscribe

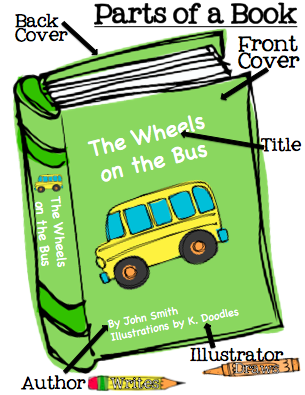

Print Awareness: Guidelines for Instruction

By: Texas Education Agency

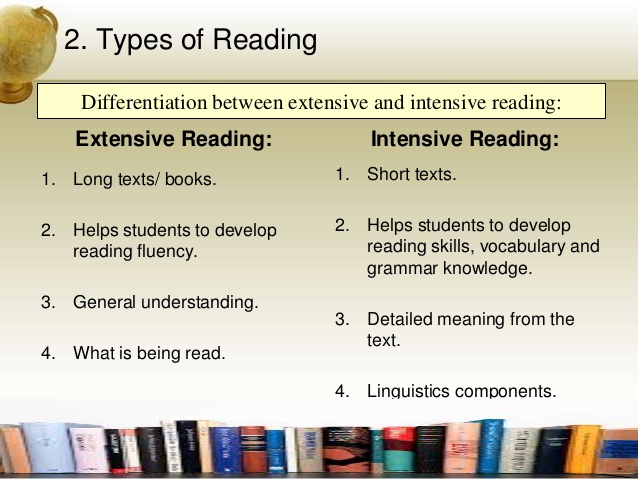

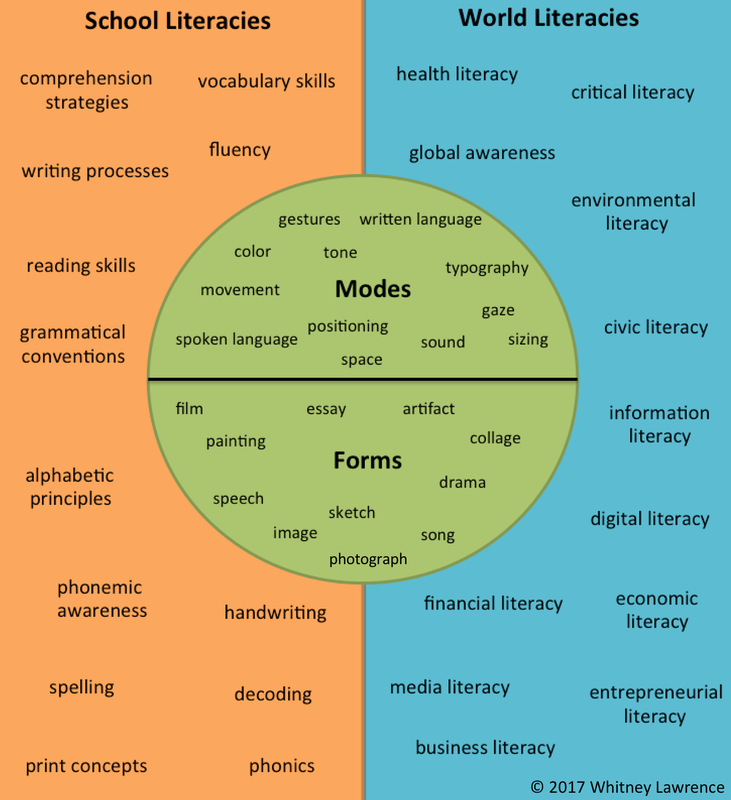

Print awareness is a child's earliest understanding that written language carries meaning. The foundation of all other literacy learning builds upon this knowledge. The following are guidelines for teachers in how to promote print awareness and a sample activity for assessing print awareness in young children.

Guidelines for promoting print awareness

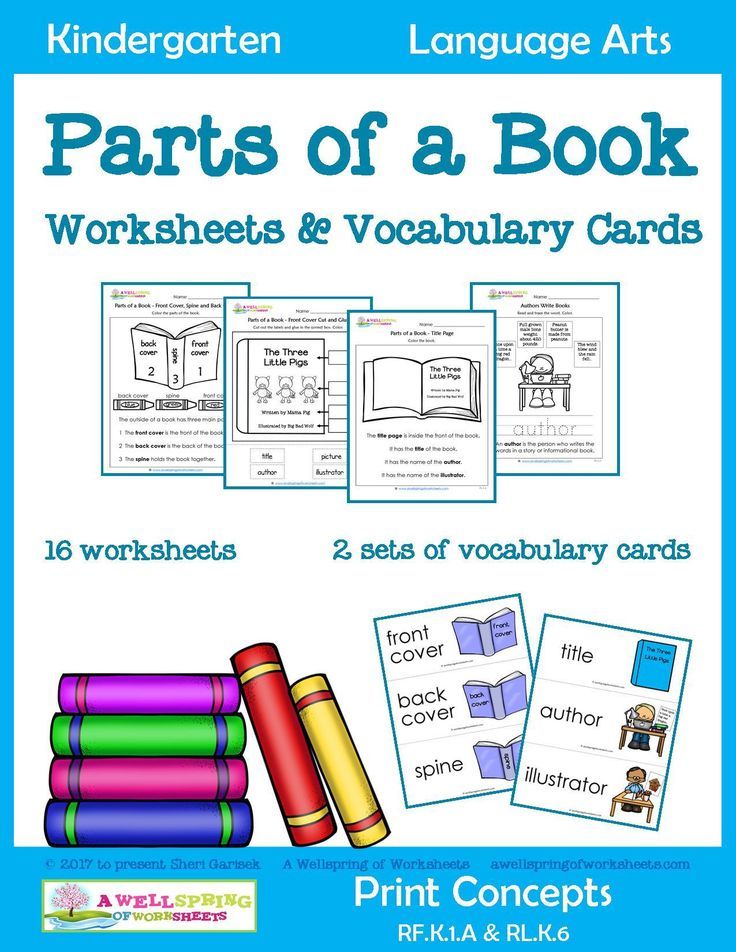

- The organization of books

Make sure students know how books are organized. They should be taught the basics about books – that they are read from left to right and top to bottom, that print may be accompanied by pictures or graphics, that the pages are numbered, and that the purpose of reading is to gain meaning from the text and understand ideas that words convey.

- Read to students

Read to children from books with easy-to-read large print. Use stories that have predictable words in the text.

- Use "big books" and draw attention to words and letters

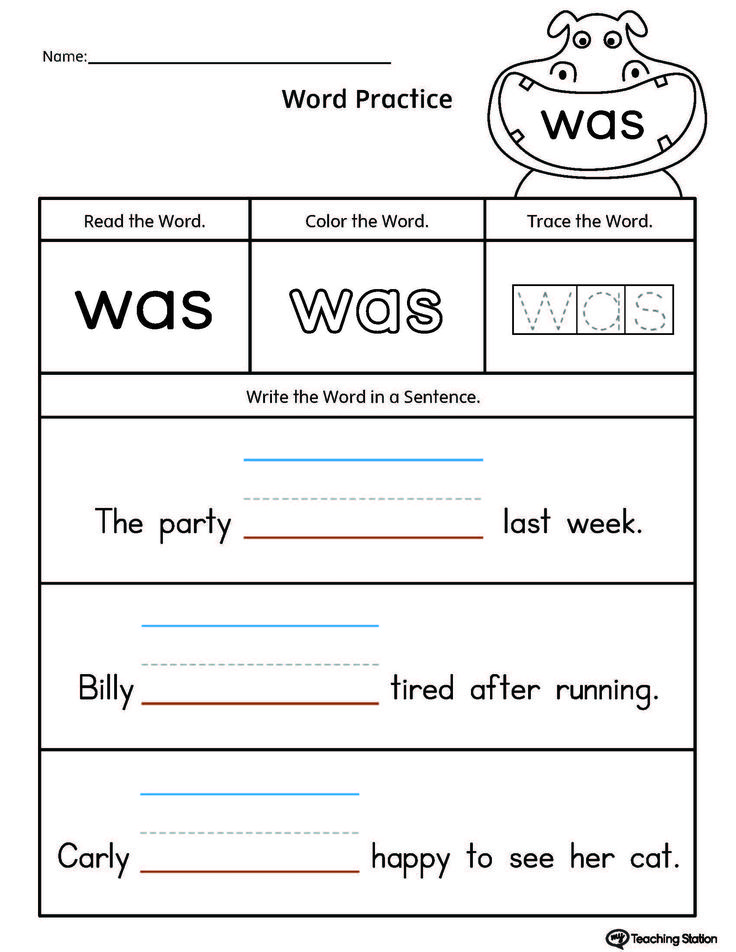

Help children notice and learn to recognize words that occur frequently, such as a, the, is, was, and you. Draw attention to letters and punctuation marks within the story.

- Label objects and centers in your classroom

Use an index card to label objects and centers within the classroom with words and pictures.

Use an index card with the word "house" for the house center and draw a picture of a house. Draw students' attention to these words when showing them the different centers.

Use an index card with the word "house" for the house center and draw a picture of a house. Draw students' attention to these words when showing them the different centers. - Encourage preschool children to play with print

They can pretend to write a shopping list, construct a stop sign, write a letter, make a birthday card, etc.

- Help children understand the relationship between spoken and written language

Encourage students to find on a page letters that are in their names: "Look at this word, 'big.' It begins with the same letter as the name of someone in this room, 'Ben.'"

- Play with letters of the alphabet

Read the book Chicka Chicka Boom Boom. Place several copies of each letter of the alphabet in a bowl and ask students to withdraw one letter. When everyone has a letter, ask each student to say the letter's name and, if the letter is in his or her own name, have the child keep the letter. Continue until the first child to spell his or her name wins.

- Reinforce the forms and functions of print

Point them out in classroom signs, labels, posters, calendars, and so forth.

- Teach and reinforce print conventions

Discuss print directionality (print is written and read from left to right), word boundaries, capital letters, and end punctuation.

- Teach and reinforce book awareness and book handling

- Promote word awareness by helping children identify word boundaries and compare words

- Allow children to practice what they are learning

Ask them to listen to and participate in the reading of predictable and patterned stories and books.

- Provide practice with predictable and patterned books

Also try using a wordless picture book like Pancakes. Go through each page asking the children to tell the story from the pictures. Write their narration on a large piece of paper. Celebrate the story they authored by eating pancakes!

- Provide many opportunities for children to hear good books and to participate in read-aloud activities

A sample activity for assessing print awareness

Give a student a storybook and ask him or her to show you:

- The front of the book

- The title of the book

- Where you should begin reading

- A letter

- A word

- The first word of a sentence

- The last word of a sentence

- The first and last word on a page

- Punctuation marks

- A capital letter

- A lowercase letter

- The back of the book

Excerpted and adapted from: Guidelines for Examining Phonics and Word Recognition Programs, Texas Reading Initiative, Texas Education Agency (2002). And from: Tips for Teaching Kids to Read; by Ed Kame'enui, Marilyn Adams, & G. Reid Lyon.

Related Topics

Curriculum and Instruction

Early Literacy Development

Print Awareness

New and Popular

Print-to-Speech and Speech-to-Print: Mapping Early Literacy

100 Children’s Authors and Illustrators Everyone Should Know

A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words

7 Great Ways to Encourage Your Child's Writing

Screening, Diagnosing, and Progress Monitoring for Fluency: The Details

Phonemic Activities for the Preschool or Elementary Classroom

Our Literacy Blogs

Shared Reading in the Structured Literacy Era

Kids and educational media

Meet Ali Kamanda and Jorge Redmond, authors of Black Boy, Black Boy: Celebrating the Power of You

Get Widget |

Subscribe

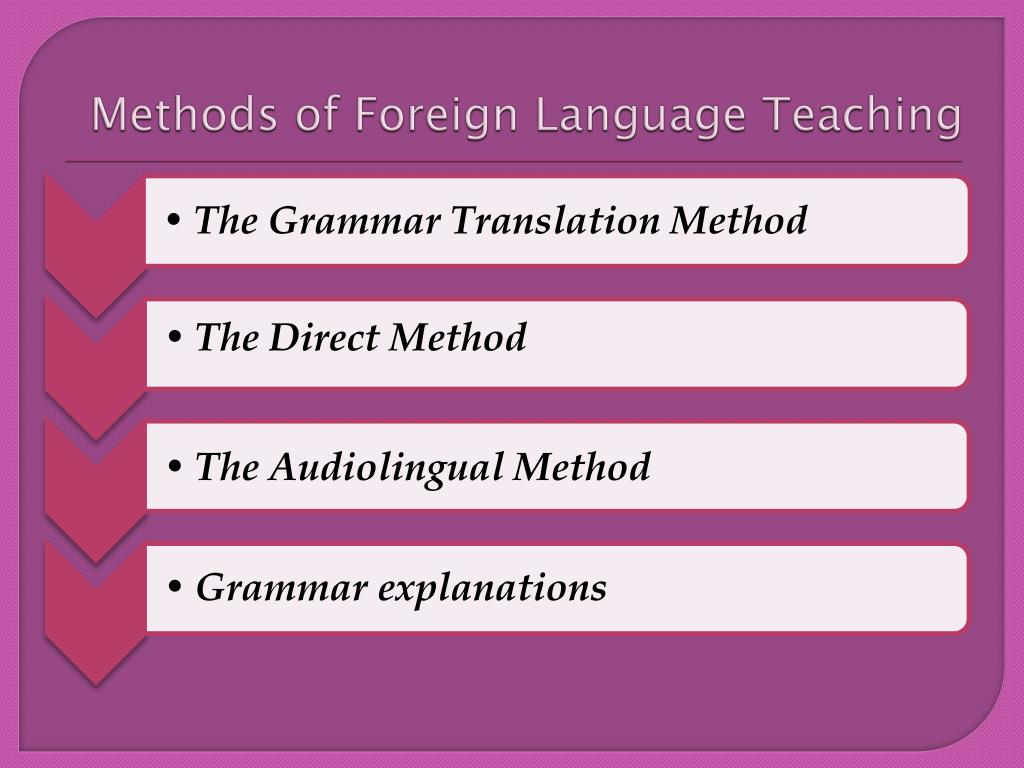

34_Bredikhina_Teaching Methods.

cdr

cdr %PDF-1.3 % 453 0 obj > endobj 452 0 obj >stream application/pdf

7јz؝cx϶[-xg۳c S?= r˯Ўuz'J ۳;ɫi:{\[әCq4vg mG|mK8go~Z?9!b(Zjv{NbjÓÛE}≥[xׇ[˞1]kxMjWRxoj1]dI-CK,ʰmQg]m%,/O("#[1v%{2\IG

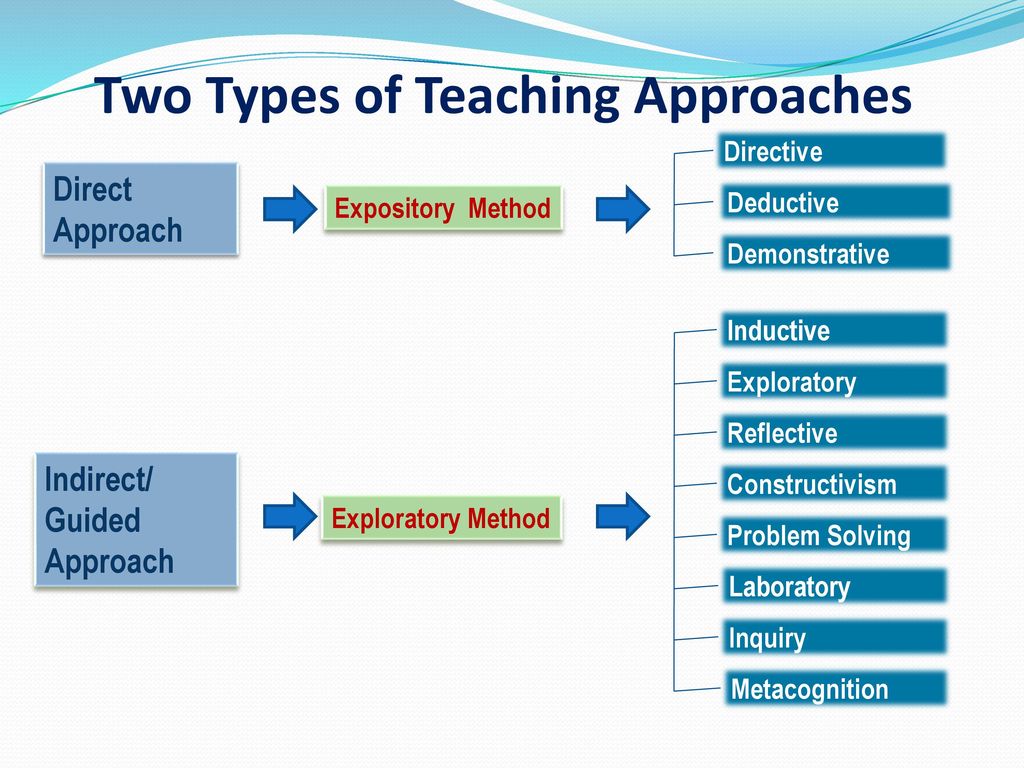

7јz؝cx϶[-xg۳c S?= r˯Ўuz'J ۳;ɫi:{\[әCq4vg mG|mK8go~Z?9!b(Zjv{NbjÓÛE}≥[xׇ[˞1]kxMjWRxoj1]dI-CK,ʰmQg]m%,/O("#[1v%{2\IG On the question of the methodological foundations of teaching Russian as a native, non-native and foreign language

The article analyzes the current situation in the field of teaching Russian as a native, non-native and foreign language. There is a tendency to blur the boundaries of the application of teaching methods. The expediency of singling out a separate methodology for teaching Russian as a non-native language is called into question. The problems of teaching foreigners in a Russian-speaking environment and the problems of teaching the Russian language to children with Russian as their native language are considered. It is suggested that it is necessary to create a syncretic methodology for teaching the Russian language, capable of responding to the challenges of our time. nine0014

KEYWORDS: Russian; Russian as a foreign language; methods of teaching the Russian language; methodology of the Russian language at school.

INFORMATION ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

- Dobrenko Evgenia Igorevna, teacher of the RFL, Academy of Russian Ballet. A. Ya. Vaganova.

- Sokolova Elena Vladimirovna, Candidate of Philology, Senior Lecturer, St. Petersburg State University. nine0031

- Teaching word analysis by composition (morpheme analysis).

- Training in word-formation analysis.

- Training in morphological analysis.

- Teaching proper spelling.

- Parsing training.

- Teaching proper punctuation.

- Completion of teaching literate writing - learning stylistics” [Badmaev, Khoziev 1999: 22].

- Balykhina T. M. Methods of teaching Russian as a non-native, new language. - M. : Publishing house of RUDN University, 2007. 185 p. nine0004

- Badmaev B. Ts., Khoziev B. I. Methods of accelerated learning of the Russian language: method. teacher's guide. - M .: Humanit. ed. Center "VLADOS", 1999. 232 p.

- Galperin P.Ya. General view on the doctrine of the so-called gradual formation of mental actions, ideas and concepts / pred. to the press M.A. Stepanova // Vestnik Mosk. university Ser. 14. Psychology. - 1998. No. 2. S. 3–8.

- Kirov E.F. Russian language as a non-native language and its theoretical foundations // Notes of the Mining Institute. — 2011. Vol. 193. S. 229–233.

- Kudoyarova T. V. Russian as a native, non-native and foreign language in schools of the CIS. To the round table "Actual problems of studying and teaching the Russian language in the countries of the post-Soviet space" [Electronic resource] // Website of the State Institute of the Russian Language.

A. S. Pushkin. 06/02/2015. — Access mode: https:// pushkininstitute. ru/cis_council (date of access: 05/13/2018).

A. S. Pushkin. 06/02/2015. — Access mode: https:// pushkininstitute. ru/cis_council (date of access: 05/13/2018). - Rosenblum S.A. Teaching migrant children in Russian schools as one of the aspects of inclusive education [Electronic resource] // Psychology of Relations: Network Journal. nineteen.02.2018. — Access mode: http://psiholog4you.ru/obuchenie-detey-migrantov-rossiyskih-shkolah/ (date of access: 05/13/2018).

- Fedosov V.A. On the communicative method of teaching Russian as a foreign language // Russian Language Abroad. — 2011. No. 1. S. 25–29.

- Balykhina T. M. Metodika prepodavaniya russkogo yazyka kak ne-rodnogo, novogo. - M. : Izd-vo RUDN, 2007. 185 s.

- Badmaev B. Ts., Khoziev B. I. Metodika uskorennogo obucheniya rus-skomu yazyku : metod. posobie dlya uchitelya. — M. : Humanit. izd. tsentr «VLADOS», 1999.232 s.

- Gal'perin P. Ya. Obshchiy vzglyad na uchenie o tak nazyvaemom po-etapnom formirovanii umstvennykh deystviy, predstavleniy i ponyatiy / podg.

Learn more

TO THE QUESTION ABOUT THE METHODOLOGICAL BASICS OF TEACHING RUSSIAN AS A NATIVE, NON-NATIVE AND FOREIGN LANGUAGE The article analyzes the current situation in the sphere of teaching Russian as a native, non-native and foreign language, points to the tendency to blur the boundaries of the methods of teaching, to casts doubt on the expediency of separate methods of teaching Russian as a non-native language, considers the problems of teaching Russian as a non-native language in the Russian-speaking environment and the problems of teaching Russian as a native language. The authors suggest the need to create a syncretic method of teaching the Russian language, able to respond to the challenges of our time. nine0014

nine0014

KEYWORDS: Russian language; Russian as a foreign language; Russian language teaching methods; methodology of the Russian language at school.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS: Dobrenko Evgenia Igorevna, Lecturer, Vaganova Academy .

Sokolova Elena Vladimirovna , Ph.D.0014 .

In recent years, in the field of teaching the Russian language, there has been a tendency towards the interpenetration of methods of teaching it as native, non-native and foreign [Kudoyarova 2015: 4]. This trend was considered primarily as characteristic of the teaching of the Russian language in the multi-ethnic environment of the countries of the post-Soviet space, however, some facts indicate that we can talk about its universal nature.

Three types of approaches to teaching the Russian language (RKR, RKN, RFL) are distinguished both on the basis of certain characteristics of students and on the basis of the features of the theoretical basis for creating one or another teaching methodology. Russian as a native language is taught to those students who from early childhood mastered speech activity in Russian and for whom Russian is the main means of communication. The Russian language as a non-native language is oriented towards non-native citizens of the Russian Federation, “who have a fairly good idea of the realities of Russian life, who speak Russian to a certain extent and, most importantly, understand well what the Russian mentality and culture are. Moreover, they themselves form to some extent the mentality and culture of the Russian Federation” [Kirov 2011: 230]. Russian as a foreign language has as its addressee foreigners who, for one reason or another, study Russian. It is traditionally believed that Russian as a native language is based on “descriptive grammar of the Russian language” [Kirov 2011: 230], and the method of Russian as a foreign language is based on “communicative grammar… supplemented by comparative grammar” [Kirov 2011: 230]; it is argued that the study of RKN has "much in common with the study of Russian as a native language" [Balykhina 2007: 12], and the specificity of RKN is due to different ways of mastering native and non-native languages - not "from the bottom up", but "from the top down" [Balykhina 2007: 12: 12].

Russian as a native language is taught to those students who from early childhood mastered speech activity in Russian and for whom Russian is the main means of communication. The Russian language as a non-native language is oriented towards non-native citizens of the Russian Federation, “who have a fairly good idea of the realities of Russian life, who speak Russian to a certain extent and, most importantly, understand well what the Russian mentality and culture are. Moreover, they themselves form to some extent the mentality and culture of the Russian Federation” [Kirov 2011: 230]. Russian as a foreign language has as its addressee foreigners who, for one reason or another, study Russian. It is traditionally believed that Russian as a native language is based on “descriptive grammar of the Russian language” [Kirov 2011: 230], and the method of Russian as a foreign language is based on “communicative grammar… supplemented by comparative grammar” [Kirov 2011: 230]; it is argued that the study of RKN has "much in common with the study of Russian as a native language" [Balykhina 2007: 12], and the specificity of RKN is due to different ways of mastering native and non-native languages - not "from the bottom up", but "from the top down" [Balykhina 2007: 12: 12]. Delimiting the concepts of Russian as a foreign language, ILV and RLNS (Russian language in national schools), E.F. Kirov proposes to use the achievements of Russian as a foreign language in the methodology of ILV and at the same time develop original principles for describing the language and its methodological presentation in the educational process. New principles should be based on integrative linguistics, integral linguistics [Kirov 2011: 231]. Symptomatic is the desire to address (in order to develop the most effective methodology for teaching a language) to certain universals that can be related to a wide variety of linguistic phenomena that are present even in languages of different structures - synthetic and analytical. The desire to develop a universal linguistic apparatus at the theoretical level corresponds to the currently observed syncretism in the methodological techniques used in the process of teaching the Russian language. nine0007

Delimiting the concepts of Russian as a foreign language, ILV and RLNS (Russian language in national schools), E.F. Kirov proposes to use the achievements of Russian as a foreign language in the methodology of ILV and at the same time develop original principles for describing the language and its methodological presentation in the educational process. New principles should be based on integrative linguistics, integral linguistics [Kirov 2011: 231]. Symptomatic is the desire to address (in order to develop the most effective methodology for teaching a language) to certain universals that can be related to a wide variety of linguistic phenomena that are present even in languages of different structures - synthetic and analytical. The desire to develop a universal linguistic apparatus at the theoretical level corresponds to the currently observed syncretism in the methodological techniques used in the process of teaching the Russian language. nine0007

These trends in the development of Russian language teaching methods are caused not only by the desire to increase the effectiveness of the educational process, but also by the changes taking place around us. Thus, the basic addressee of the RKN methodology gradually disappears: a category of citizens of the Russian Federation appears who almost do not speak Russian, who are largely alien to the Russian mentality and culture (and in these respects approaching foreigners) and are not always able to exert a formative influence on the mentality and culture of the Russian Federation. This category of citizens is formed by a large number of people with dual citizenship (not necessarily from neighboring countries), some of whom do not consider Russia as a country of permanent residence, but use the opportunities provided to them (as citizens of Russia) to satisfy their pragmatic interests. Under such conditions, the boundary between RFL and ILV naturally begins to blur, and it probably makes sense to consider the concept of ILV as temporary and already outgoing. In this case, it seems inappropriate to talk about the creation or improvement of any particular method of teaching RKN, but it should be considered as one of the approaches to teaching a certain category of students in the framework of Russian as a foreign language and proceed from the fact that when they are taught, speech should not be about corrective assistance in mastering, for example, the Russian language program in secondary school, but about creating a full-fledged system for including foreign speakers in the Russian-speaking space, like a well-established “sub-faculty-university” scheme.

Thus, the basic addressee of the RKN methodology gradually disappears: a category of citizens of the Russian Federation appears who almost do not speak Russian, who are largely alien to the Russian mentality and culture (and in these respects approaching foreigners) and are not always able to exert a formative influence on the mentality and culture of the Russian Federation. This category of citizens is formed by a large number of people with dual citizenship (not necessarily from neighboring countries), some of whom do not consider Russia as a country of permanent residence, but use the opportunities provided to them (as citizens of Russia) to satisfy their pragmatic interests. Under such conditions, the boundary between RFL and ILV naturally begins to blur, and it probably makes sense to consider the concept of ILV as temporary and already outgoing. In this case, it seems inappropriate to talk about the creation or improvement of any particular method of teaching RKN, but it should be considered as one of the approaches to teaching a certain category of students in the framework of Russian as a foreign language and proceed from the fact that when they are taught, speech should not be about corrective assistance in mastering, for example, the Russian language program in secondary school, but about creating a full-fledged system for including foreign speakers in the Russian-speaking space, like a well-established “sub-faculty-university” scheme. nine0007

nine0007

Nevertheless, no matter how we define the boundaries of the concepts of Russian as a foreign language and ILV, work on the optimization and intensification of the education of foreign children can go not only along the path of creating additional structures within a single process of school education. It can also affect the basics of teaching Russian as a native language.

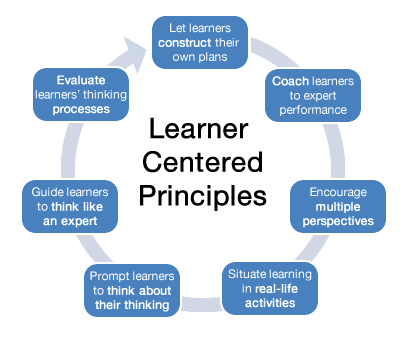

The low effectiveness of teaching children of migrants in the Russian-speaking community was repeatedly noted. And this is connected, first of all, with the way of presenting linguistic material in the Russian language lesson. However, along with the statement of the fact that this category of children lag behind Russian students, there is accumulating material that testifies to the advantages that a non-Russian-speaking child has over a Russian-speaking one if the newcomer undergoes correctly structured education within the framework of the Russian as a Foreign Language or the Russian Foreign Language: the literacy of such a child may be higher than the literacy of Russian children. O. V. Sineva, associate professor at the Moscow Institute of Open Education, sees the reason for this paradox in the following: the foreigner first learns the prepositional-case system and vocabulary of the Russian language, and only after that, unlike Russian children, spelling and analysis of words and sentences; the foreign phone prescribes and memorizes the word in its various forms, which makes the connection between the sound form of the word and the graphic one stronger; the foreigner very early (earlier than a Russian-speaking child) gets acquainted with the patterns of word formation in the Russian language and therefore he has fewer problems when writing them (for example, early acquaintance with the “apple-apple” model leads to the fact that, according to O. V. Sineva, “the foreign phone does not even think that there “maybe” a soft sign somewhere” [Rozenblum 2018]). These observations testify to the high effectiveness of Russian as a foreign language approaches to teaching the native language and raise the question of revising the basic provisions of the methods of teaching the Russian language at school.

O. V. Sineva, associate professor at the Moscow Institute of Open Education, sees the reason for this paradox in the following: the foreigner first learns the prepositional-case system and vocabulary of the Russian language, and only after that, unlike Russian children, spelling and analysis of words and sentences; the foreign phone prescribes and memorizes the word in its various forms, which makes the connection between the sound form of the word and the graphic one stronger; the foreigner very early (earlier than a Russian-speaking child) gets acquainted with the patterns of word formation in the Russian language and therefore he has fewer problems when writing them (for example, early acquaintance with the “apple-apple” model leads to the fact that, according to O. V. Sineva, “the foreign phone does not even think that there “maybe” a soft sign somewhere” [Rozenblum 2018]). These observations testify to the high effectiveness of Russian as a foreign language approaches to teaching the native language and raise the question of revising the basic provisions of the methods of teaching the Russian language at school. nine0007

nine0007

Attempts to improve the system of teaching the Russian language in Russian schools have been made for a long time and regularly, but they do not go beyond individual alternative methods and programs, but it seems that there is a need to create a single updated approach to teaching the Russian language, taking into account all the challenges that characterize the current situation around school education. There is a need for the emergence of a methodology that can qualitatively and quickly, at a lower cost, teach all students of the modern Russian school without exception, or at least make it easier for them to learn the Russian language. And at the end of 90s XX century, an approach was proposed that surprisingly echoes the patterns identified by O.V. Sineva.

In 1999, psychologists B. Ts. Badmaev and B. I. Khoziev created a method of accelerated learning of Russian grammar [Badmaev, Khoziev 1999], based on the theory of gradual formation of mental actions by P. Ya. Galperin. The general scheme of this methodological approach to teaching spelling and punctuation of the Russian language emphasizes the primary role of morphemics and word formation in teaching literate writing, which was so clearly manifested when comparing the learning outcomes of a Russian child and a migrant child. The general sequence of steps within the methodology of teaching the Russian language proposed by psychologists is as follows:

Galperin. The general scheme of this methodological approach to teaching spelling and punctuation of the Russian language emphasizes the primary role of morphemics and word formation in teaching literate writing, which was so clearly manifested when comparing the learning outcomes of a Russian child and a migrant child. The general sequence of steps within the methodology of teaching the Russian language proposed by psychologists is as follows:

It seems that an understanding of the importance of acquiring solid knowledge in morphemic and word-formation, as well as in morphology, is found in every textbook on the Russian language, because there are sections that teach morphemic and word-formation analysis, and spelling rules are distributed over specific parts of speech, and syntactic analysis of sentences accompanies the study of punctuation rules. However, it is easy to see that we are dealing, for the most part, with the formal principle of the distribution of material, and rarely where is a constant reliance on knowledge of a basic nature. Worst of all is the case with the sections "Morfemics" and "Word Formation", the repetition of which is episodic and in no way connected with the entire learning process. Thus, we are building a building of literate knowledge of the Russian language without a foundation. It is not surprising that the results of our work cannot fully please us. nine0007

However, it is easy to see that we are dealing, for the most part, with the formal principle of the distribution of material, and rarely where is a constant reliance on knowledge of a basic nature. Worst of all is the case with the sections "Morfemics" and "Word Formation", the repetition of which is episodic and in no way connected with the entire learning process. Thus, we are building a building of literate knowledge of the Russian language without a foundation. It is not surprising that the results of our work cannot fully please us. nine0007

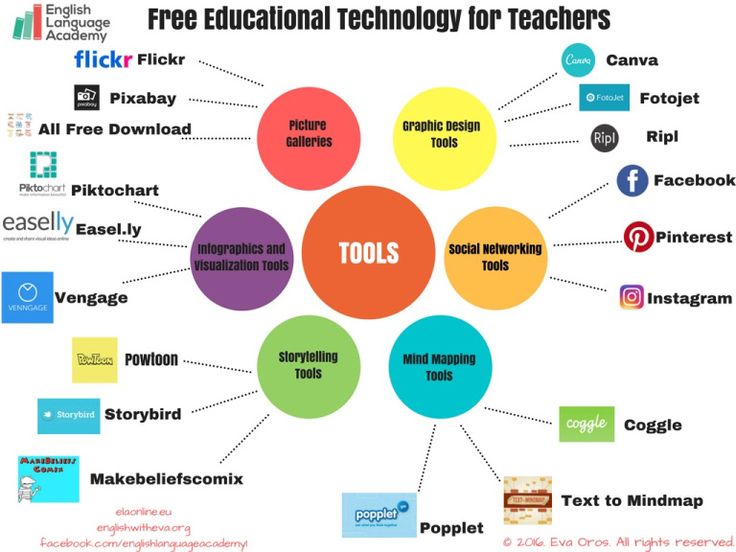

If in the above case the methods of teaching ILV and Russian as a native language agreed in the same assessment of the importance of knowledge of certain sections of the school curriculum and the sequence of their development, then the RFL method itself can be in demand in a modern school due to the leading way of presenting language material in it . In accordance with the communicative method prevailing in teaching Russian as a foreign language, when teaching the Russian language, it is customary to go from meaning to the form of its expression [Fedosov 2011: 25–26], in contrast to the leading principle of descriptive grammar — from formal classification to the rules of literate writing. If this approach is still possible when mastering the rules of spelling and punctuation, then when teaching coherent speech (development of speech), the principles of work adopted in the Russian as a foreign language may turn out to be more effective, especially in our time, when modern schoolchildren experience great difficulties in choosing the right way to express thoughts in a specific situation. The most striking example of such difficulties, but by no means the only one, can be the inability of most students to select a neutral version of any colloquial expression (or word) in the process of writing an essay. nine0007

If this approach is still possible when mastering the rules of spelling and punctuation, then when teaching coherent speech (development of speech), the principles of work adopted in the Russian as a foreign language may turn out to be more effective, especially in our time, when modern schoolchildren experience great difficulties in choosing the right way to express thoughts in a specific situation. The most striking example of such difficulties, but by no means the only one, can be the inability of most students to select a neutral version of any colloquial expression (or word) in the process of writing an essay. nine0007

Given all of the above, we have to state the fact that in the first quarter of the 21st century, teachers of the Russian language and linguists are faced with a special linguistic and multicultural situation that requires the creation of a new, largely universal methodology for teaching the Russian language, capable of meeting the needs of different categories secondary school students.

LITERATURE

REFERENCES