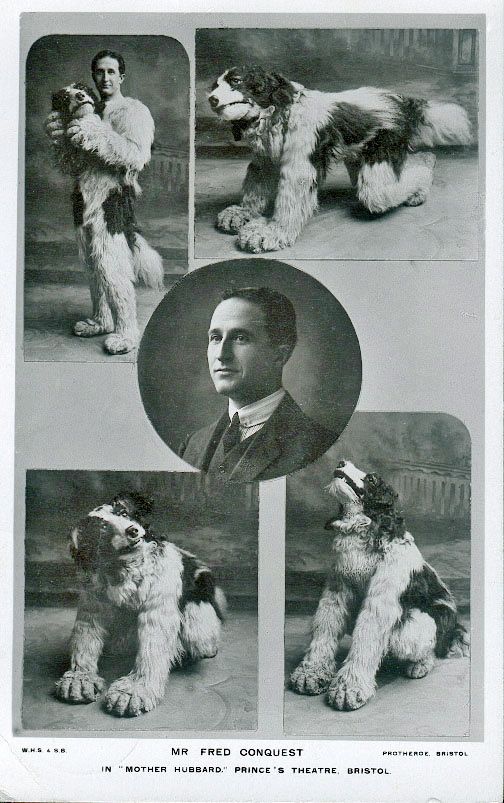

The night max wore his wolf suit

50 Years of Wild Things"-Rosenbach Museum and Library, Philadelphia

The best parts of childhood are those that resonate with you as an adult. For many, the oeuvre of Maurice Sendak is one such part. While his books, with their accompanying whimsical illustrations, are aimed at children, the ideas and themes they contain still resonate with many older people.

The Night Max Wore His Wolf Suit: 50 Years of Wild Things, on display at the Rosenbach Museum and Library until March 2, displays a considerable amount of the work behind the scenes of Sendak’s most enduring book, Where the Wild Things Are. Contained in a small room in the old mansion near Rittenhouse Square is a vast array of rough concept sketches, textual notes, and the finished ink drawings familiar to those who have read the book.

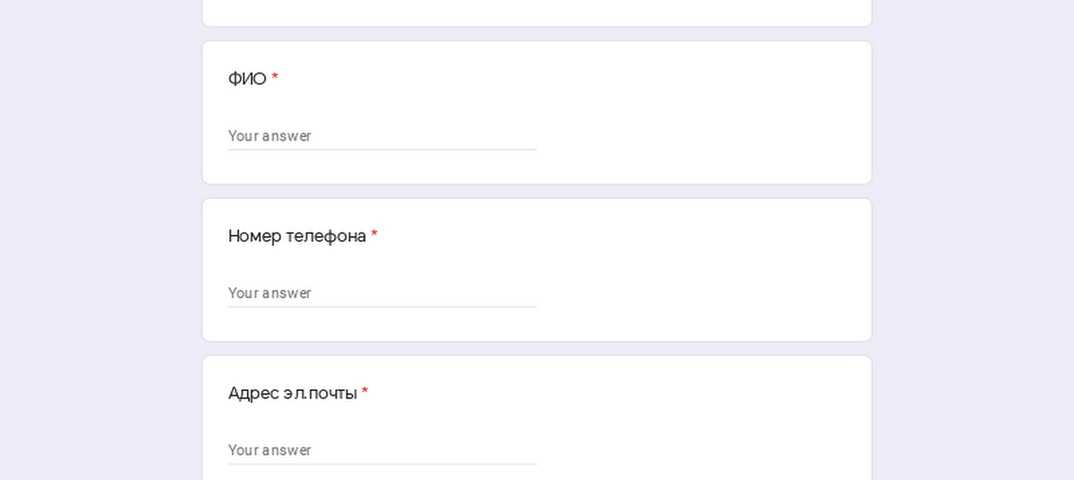

“Where the Wild Things Are p28-9”—Final drawing for Where the Wild Things Are.

Pen and ink, watercolor.

© 1963 by Maurice Sendak.

Used with permission of the Estate of Maurice Sendak.

Walking into the exhibit is a return to nostalgia and childhood, and learning about how this book came into creation is a fascinating journey through ever-changing fantastical and fictional worlds. When Sendak approached the project, he adapted an early mockup of a story called “Where the Wild Horses Are,” which he had written in 1955. Over the course of modifying the original story, he created the unforgettable character of Max and the uniquely empathetic Wild Things, which he based on his early childhood memories of his relatives.

Cases of early Sendak manuscripts and notes are pleasingly juxtaposed with tiny dummy books filled with line drawings and pencil sketches. It’s wonderful to see how the story many of us know and love developed during Sendak’s creative process. While the many pencil sketches on display are rough and quickly rendered, even the early ones show the same idea budding inside Sendak’s mind.

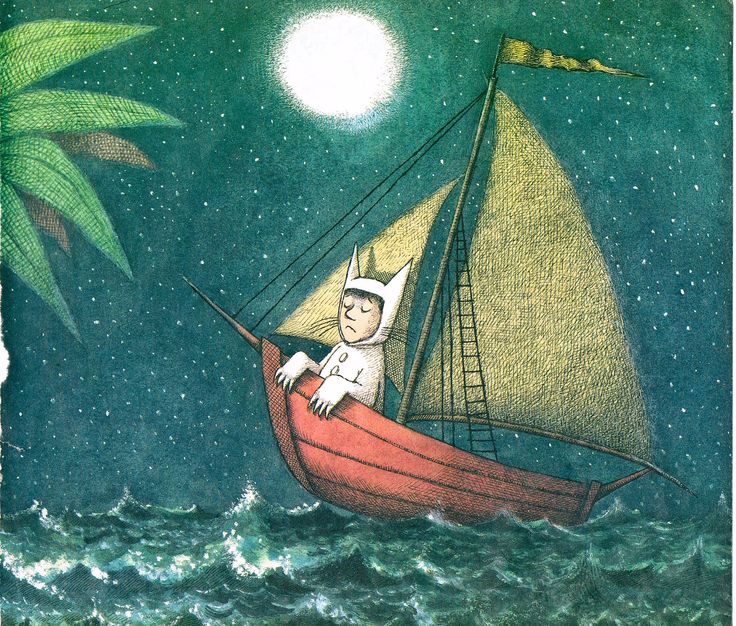

“Wild Things p20-1 prelim”—Preliminary drawing for Where the Wild Things Are.

Pencil.

© 1963 by Maurice Sendak.

Used with permission of the Estate of Maurice Sendak.

As I moved throughout the exhibit, it became quite clear through Sendak’s copious notes that he put much care and thought into the character of Max. At each step of the book’s development, he wrote to himself that he must not lose Max as the core of the story, even as the Wild Things began to emerge—that he not lose sight of Max’s complex and relatable personality.

According to the blurbs, the original concept drawings for Where the Wild Things Are depicted Max in rooms full of objects that he is upsetting with his wildness. However, in the final version, Sendak removed many of the objects to “isolate” Max as a boy who does not fit into his own world and must therefore create his own.

As a result, Max resonates strongly with the reader. Many readers can relate to the feeling that everything they do is too wild and destructive for others to understand and the feeling of isolation due to emotional and physical extremes. Max is a sympathetic character for many readers. Even though he is a child, his journey and emotions are something everyone who feels lost in the process of growing up, of becoming, can understand.

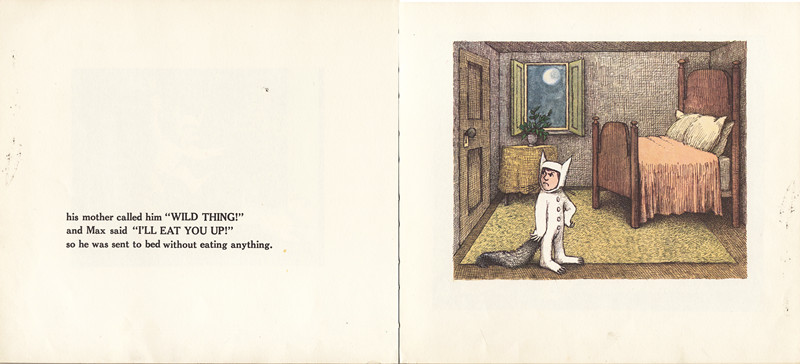

“Wild Things dummy p16”—Dummy book for Where the Wild Things Are.

Pen and ink, watercolor.

© 1963 by Maurice Sendak.

Used with permission of the Estate of Maurice Sendak.

The drawings of the Wild Things, as they develop from pencil lines to fully inked and colored beings, are positively adorable, bringing back many memories of reading this story as a child. From rough pencil sketch to the rich pen, ink, and watercolor final drawings, Maurice Sendak’s love for his story and for his characters is plain to see.

The exhibit also juxtaposes Sendak’s sketches and observations of the way children play; he would use his notes based on their actions for the “Wild Rumpus” of the final book. Maurice Sendak was an author who loved and understood children in ways that few other adults did—he understood their need for finding themselves, their needs for chaos and wildness and freedom. Ultimately, Where the Wild Things Are is still memorable because it displays a love, respect, and understanding of the minds of children without infantilizing them or projecting a premature adulthood.

“Where the Wild Things Are p13”—Final drawing for Where the Wild Things Are.

Pen and ink, watercolor.

© 1963 by Maurice Sendak.

Used with permission of the Estate of Maurice Sendak.

A small section of the exhibit is devoted to the impact Where the Wild Things Are had upon its publication. A blurb points out the daring quality of the book jacket, which does not feature Max; it creates a sense of “mystery”. Additionally, the book was originally deemed to be too scary for children due to the design of the Wild Things. However, a letter to Sendak’s publisher featuring children’s reactions would argue otherwise; many of the children found the story enjoyable rather than frightening.

A blurb points out the daring quality of the book jacket, which does not feature Max; it creates a sense of “mystery”. Additionally, the book was originally deemed to be too scary for children due to the design of the Wild Things. However, a letter to Sendak’s publisher featuring children’s reactions would argue otherwise; many of the children found the story enjoyable rather than frightening.

The Night Max Wore His Wolf Suit may be a small exhibit, but it's absolutely a gem—it is a veritable vault of memories and ideas. It reminded me that while Where the Wild Things Are is ostensibly for children, it's really for everyone who has ever felt like they didn't belong, who has felt powerless and felt like a misfit in the world.

Wild Things and the Heavenly Host — CenterForLit

Emelie Thomas | March 1, 2021

It’s a wild world we live in. Consumption runs rampant, our politics resemble a rumpus, and we are cordoned off from community. Max, the wild child from Maurice Sendak’s iconic Where the Wild Things Are, knows a thing or two about such predicaments. From the confines of his bedroom, Max travels to the wildest world of all, embarking on a mysterious, monster-filled journey which culminates in a reminder of hope and our heavenly haven. Perhaps the Wild Things can call us to turn from our rebellion and revel in the one in whom authority and glory resides.

From the confines of his bedroom, Max travels to the wildest world of all, embarking on a mysterious, monster-filled journey which culminates in a reminder of hope and our heavenly haven. Perhaps the Wild Things can call us to turn from our rebellion and revel in the one in whom authority and glory resides.

Maurice Sendak’s “wild things” look like monsters. Furred, feathered, and fanged, they can be frightening (I witnessed my nephew scream and refuse to sleep for fear of them when introduced at age four). They are a fascination, a figment of Mr. Sendak’s imagination — not the sort you’d expect to see strolling down the sidewalk. In the course of our reality-deadened, mundane days, this menacing menagerie would seem strange; and yet, the Bible shows us that we are constantly surrounded by formidable and fearful beings. Scripture describes terrific angels who greet our kind with words to ward off fright (“Fear not...”) and creatures surrounding the very throne of God, four living creatures full of eyes in front and behind and six wings apiece; elsewhere, there are dragons, great beasts resembling winged lions, four headed leopards[1], and terrible beasts with ten horns and seven heads[2]. Max’s wild things, who “roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws” are paltry when compared to these beings; yet, they can draw our attention to a transcendent reality whose terrors we would do well to regard.

Max’s wild things, who “roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws” are paltry when compared to these beings; yet, they can draw our attention to a transcendent reality whose terrors we would do well to regard.

‘There is gnashing of teeth — the wild things must be demonic!’ you might think. Perhaps… and we would do well to entertain this notion. Max becomes the king of the wild things, commanding them with words akin to Christ’s authority over the demons; yet, Max is no Christ-like king. Max entertains the wild things, engaging in their rumpus, and then, after telling them to “BE STILL!” Max sends the wild things to bed without anything to eat. Max does not have any food to give; he does not resemble the good shepherd, the Lamb who lays down his life for his sheep and bids them eat of his flesh. Max wears a wolf suit, acting in the guise of the one who snatches and scatters.

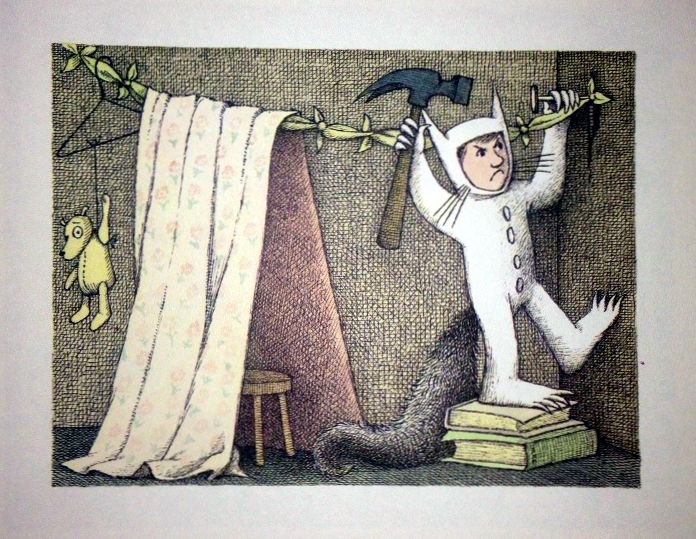

“The night Max wore his wolf suit…” begins Maurice Sendak at the beginning of the book, going on to depict Max making “mischief of one kind and another. ..” Max’s mischievous actions include pounding nails into the wall, hanging his stuffed animal in a noose, and stealing after his dog while wielding a fork-weapon. We are so familiar with Max and his wild things that we might not think twice about their actions (I love reading this book to my children, and admittedly, have a couple cutesy-looking wild things lurking in the corners of my stuffed-animal bin). Yet, upon closer examination, Max’s mischief at the outset of the story eerily parallels the thief, or wolf, in scripture, who “comes only to steal and kill and destroy[3]” (Max steals after his dog, kills his stuffed animal, and destroys the wall). Max does not enter through the door; by climbing in a different way, he gets sent in another direction entirely – to his room, without any supper.

..” Max’s mischievous actions include pounding nails into the wall, hanging his stuffed animal in a noose, and stealing after his dog while wielding a fork-weapon. We are so familiar with Max and his wild things that we might not think twice about their actions (I love reading this book to my children, and admittedly, have a couple cutesy-looking wild things lurking in the corners of my stuffed-animal bin). Yet, upon closer examination, Max’s mischief at the outset of the story eerily parallels the thief, or wolf, in scripture, who “comes only to steal and kill and destroy[3]” (Max steals after his dog, kills his stuffed animal, and destroys the wall). Max does not enter through the door; by climbing in a different way, he gets sent in another direction entirely – to his room, without any supper.

Jesus cautions us against the thief and the wolf. The threat of the demonic is real and it is all too easy to align ourselves with it, or to become complacent. Thankfully, although Max assumes the guise of the wolf in his collusion and coronation with the wild things, he is not THE wolf. Max is a sheep, like us. And his mischief, like ours, is a distortion wrought by fallenness. “I’LL EAT YOU UP!” cries Max as he defies his mother. Max’s challenge is poignant because eating is the start and the heart of our sinful, surfeit appetites. In our sin, we consume one another, affront those we love, and too-readily retreat into self-isolation.

Max is a sheep, like us. And his mischief, like ours, is a distortion wrought by fallenness. “I’LL EAT YOU UP!” cries Max as he defies his mother. Max’s challenge is poignant because eating is the start and the heart of our sinful, surfeit appetites. In our sin, we consume one another, affront those we love, and too-readily retreat into self-isolation.

If Max continues in the way of the wolf, he too will be scattered. His shepherd knows this. When Max climbs in another way, the door is shut on him (his bedroom door, that is). Yet, his journey brings him closer to the true door. Max takes his turn at being king, and discovers his emptiness; he sends the wild things to bed without anything, and acknowledges a void that mischief and rebellion cannot cover. “Max the king of all wild things was lonely, and wanted to be where someone loved him best of all.” Max is a sheep, and was never meant to be a wolf or a wild thing; because of this, he can still sense the shepherd’s summons.

“Then all around from far away across the world he smelled good things to eat…” The answer to Max’s deepest desire is a transcendent feast — food that nourishes the soul[4]. But Max cannot partake of it in his sinful, self-righteous state. As we do before approaching the Lord’s table, Max repents, turning from his self-erected throne; “... he gave up being king of where the wild things are”.

Yet the wild host surrounding Max bewail his departure: “Oh, please don’t go — we’ll eat you up — we love you so!” These wild things are not the cherubim and seraphim of the Almighty Creator, but they know one of the most fundamental gospel truths. Love consumes.

“So Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you. Whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day. For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink. Whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him. As the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so whoever feeds on me, he also will live because of me.” John 6:53-57

Whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him. As the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so whoever feeds on me, he also will live because of me.” John 6:53-57

Max leaves the wild things, “sailing back over a year / and in and out of weeks / and through a day” and leads us, the reader, back into the confines of his room. He has journeyed, at the last, to a place prepared for him, to the love of a parent, to a feast set out in his true home. So, too, Christ leads us into transcendence, preparing our heavenly, eternal home even as he enters our hearts, our homes, and our houses of worship in the here-and-now.

It’s a wild world we live in, but there is nothing new under the sun. There will come a day, after the rumpus described in Revelation, where the Son will say “BE STILL” and will draw all things to himself. He is, after all, all-in-all, more wildly wonderful than we can ever imagine.

[1] Daniel 7:6

[2] Danile 7:7, Revelation 13:1

[3] John 10:10, ESV

[4] “Oh taste and see that the Lord is good! Blessed is the man who takes refuge in him!” Psalm 34:8, ESV

Emelie Thomas is a nuclear trained Naval Officer with a degree in English Literature. She is married to Jay Thomas, who shares the same odd pedigree, and they are parents to three children. Emelie spends her days with the Nuclear Navy and spends her evenings celebrating literature and liturgy with her little ones.

She is married to Jay Thomas, who shares the same odd pedigree, and they are parents to three children. Emelie spends her days with the Nuclear Navy and spends her evenings celebrating literature and liturgy with her little ones.

| – Heather is not bad, but she is still my little daughter, so I will always worry about her , but I entrusted it to you, and I want to believe that I'm still quite good at reading people. - Mr. Vernon. I made a pact with you, and I will protect your daughter, no matter what the cost, and even more so, - Max frowned, - you knew my father long enough to tell me a little more about him than I knew him. - So you changed the terms of the contract a little? “No,” Max shook his head. "It's probably just a small request," he shrugged. "Okay, we'll do that," Vernon nodded. “Well, now I have to leave, and Heather, if I'm not mistaken, wants to meet friends, so it's time for you to pack,” Vernon got up from his chair. - Gather? Max asked and also stood up. - Yes. Black suit, now your uniform. Chapter 7 - This is still not enough for me, - the girl whispered and moved away from the door, behind which she had just heard a conversation between her father and this guy. "And he's handsome, whatever one may say," her consciousness agreed. "We need to call Maddison urgently," Heather said and went back to her bedroom. – Suit? Max asked. “Yes, it hangs in your closet,” Vernon smiled slightly. “Shit,” Max whispered. - What? the man asked. - I say, probably, the suit is expensive, - Max got out. "The car is in the garage," Vernon reminded him and left Max's new bedroom. The guy opened the closet, and there, in fact, there was a jacket, and on a hanger next to it were black pants, below, on a shelf, there was a box, there were shoes. “Double shit,” Max whispered and started to change. Pants and shoes were on when the door opened without knocking. “I have to go now,” it was Heather. Max was buttoning up the last buttons of his white shirt. – Weren't you taught to knock before entering your adult uncle's bedroom as a child? Max raised an eyebrow and took the jacket. Heather looked at Max and saw what looked like a tattoo on his chest. – Do you have a tattoo? she asked, ignoring his words. “Anything is possible,” he put on his jacket. Heather's face instantly changed when she saw the King. “What a handsome man,” she sat down in front of him to pet him. This picture was really cute. Max smiled slightly. Just now this girl was rude, and now she looks like a child. “You must have been late.” Max was fully prepared. – Shall we take it with us? “No, he doesn’t like to sit in cars for a long time, and they don’t let dogs in cafes,” Max said in a tone like Heather was a child. - But my friends and I will go for a walk in the park, and I would like to take a walk with him, - Heather looked at him in such a way that . - I can’t forbid you, - he stepped into the meeting and took the leash from the chair . "Here," he handed her the leash. “But I don’t promise that he will obey you,” Max opened the door. “Good.” She smiled broadly. Crazy girl, thought Max. A black and tinted Toyota RAW 4 was waiting for them in the garage. When Max saw her, a smile appeared on his face. He had such a car, but he had to sell it, and he bought himself a mustang and did not regret it at all. “You’re like a child,” Heather grumbled, and opening the back door, let the King in, and sat in the front seat herself. Max sat in the driver's seat, took out the keys that were in the glove compartment (not at all strange) and started the engine. He was very quiet. - Buckle up, Max warned. – Strap yourself in, – Max looked at her and Heather, rolling her eyes, buckled up. Max rode out and the gate closed behind him. The road was smooth, which is not surprising. – Why did you get a job with us? Hez asked. “So it is necessary,” he shrugged and turned into another street. Heather just nodded. I wonder if Max will tell her the truth? Ten minutes later they arrived at the cafe. “I won't be long, and then we'll go to the park,” Heather warned and jumped out of the car without waiting for an answer. Max looked after her as she entered the cafe, the company was visible through the large windows, although not very well, the sun was too bright. Max looked at the time. The king began to whimper softly. – I know that you hate to sit in the car for a long time, but you asked for it yourself, – Max looked at the dog and turned away. The guy was uncomfortable in a suit, his maximum formality was usually a shirt and a jacket, and this is a whole suit. Max spat and took off his jacket, unbuttoned the top buttons and took off his tie, and then threw it all into the next seat. “Idiot,” he whispered, and got out of the car. In the cafe, sitting at a table, Heather could clearly see both the car and Max. - He's hot, I would sleep with him - Mad looked at Max and giggled. - What? Heather was surprised. He is ten years older than you! - These guys are much more experienced than guys of our age, and people like him, - Mad pointed at Max, who was standing near the car and talking to someone on the phone, - they are very, very good at using what they have awarded their nature. - How do you know that? "And he's hot on top of everything," added Annie, Heather and Mad's second friend. “Exactly,” Mad agreed and took a sip of her drink. - Yes, okay. He's normal, although I'm sure he has a tattoo on his chest,” Heather said. - Where did you get that from? – Today I went into his room… – Without knocking as usual, Annie giggled, Heather nodded. "But he practically buttoned his shirt, so I can't tell for sure," Heather replied. “But I can find out,” Mad said, and her gaze turned into a predatory one. - Oh, not that! Come on without your seductions of my guards. – You yourself wanted to get rid of him! And even more so, I love older guys,” Mad said and her gears started working, her friends laughed, but part of Heather did not want Max to leave so early and another part of her could not stand it when her friend slept with older guys. “Okay, let’s go to the park,” Eni said, and the girls left the cafe after paying. Max whistled and the King ran to the car. "I'm Madison, but my friends just call me Mad." She smiled seductively. – Hello, just Mad, – Max smiled with a corner of his lips. - And I'm Eni, - a girl with blond hair and a blue sundress approached the guy and smiled slightly. The first she would definitely not start an acquaintance. “Max,” the guy introduced himself and looked at Heather. – Where are you now? – We are going to the park, are you with us? Mad answered for her friend. “I'll be there,” he replied, and Heather rolled her eyes and took the King's leash. Heather went ahead, followed by Annie, Madison bit her lip seductively and, after saying something like "see you", she followed her friends, wiggling her hips. Max, without even looking, got into the car and, starting the engine, slowly drove after them. Chapter 8 In the past two weeks, Heather and Max tried to kill each other 14 times. Max could hardly restrain himself to endure all the antics of Heather. Heather, in turn, tried to get rid of Max as soon as possible. Max took her to the boutique on Monday, but Heather told him to go with her and Max went because he shouldn't leave her alone, but who knew it would be a lingerie store? Heather didn’t think that was enough, and she literally dragged Max along and asked: “How do you like this one?” “Maybe blue is better? Or still leave the red. Max lasted exactly until the moment when Heather called him into the locker room and told him to evaluate the sets she had chosen. On Tuesday, Heather was helped by her friend Mad, she tried with all her skills to seduce Max so that Heather could sneak out of the cafe unnoticed, but neither her friend nor Heather herself could do anything. |

Center for Children's Books and Children's Programs

#2

sendak-wild-things-portrait.jpg

The American artist Maurice Sendak is one of the central figures in contemporary children's literature. And, let's add, one of the most mysterious and controversial. His work is well known in England, France, Germany, Scandinavia, and Japan. He is the winner of numerous prestigious literary awards - the Caldecott Medal (1964), the H.C. Andersen International Medal (1970), the Laura Ingalls Wilder Prize (1983) and many others. But, although the recognition of Maurice Sendak can now be considered unconditional, disputes about the master's work have not subsided so far.

Maurice Sendak was born in 1928 in Brooklyn, New York to Polish Jewish parents. The family was not rich, the area was poor and the children spent most of their time on the street. These street impressions subsequently returned more than once to Sendak's books. However, he was a sickly boy, and could rather observe life than participate in it. The 1930s were not only the time of the Great Depression, but also the heyday of American pop culture, the reign of Disney, King Kong, comics.

#1

Sendak admits that as a child, two figures dominated his thoughts - "Mickey Mouse and the stern bearded grandfather", whom Maurice knew only from a photograph, but who personified all Jewish culture and history for him. "He seemed to me very similar to God."

Maurice Sendak did not receive a special art education, but he carefully studied the work of other artists, the history of book illustration.

#5

After leaving school, Sendak worked as a window dresser in a toy store on Fifth Avenue and spent every spare moment in the picture book store. An unusual regular was noticed by one of the sellers and, having learned about his hobby, he introduced the young man to the editor of the Harper and Brothers publishing house, Ursula Nordström. The drawings of the young artist interested her, and Sendak received the first order - to illustrate the book by Marcel Aimé "Remarkable Farm" (1951). Thus began a long and fruitful collaboration between the artist and the publishing house.

An unusual regular was noticed by one of the sellers and, having learned about his hobby, he introduced the young man to the editor of the Harper and Brothers publishing house, Ursula Nordström. The drawings of the young artist interested her, and Sendak received the first order - to illustrate the book by Marcel Aimé "Remarkable Farm" (1951). Thus began a long and fruitful collaboration between the artist and the publishing house.

#6

Sendak-22.jpg

Sendak-1.jpg

Sendak-8.jpg

Sendak-9.jpg

Sendak-19.jpg

#8 illustrations for books by various authors, which Ursula Nordsterm specially selected for him. A year later, the first success came, it was brought to the artist by work on the book by Ruth Kraus "A Hole to Dig" (1952). This very unusual book consists of children's definitions of various objects: "Dogs - to kiss people. Hands - to hug. Buttons - for warmth. Lips - so that the crumbs do not fall on the floor. The book - so that you can look at it, etc. This work showed the artist's ability to cement, combine text and image into a single whole. In this case, this was especially important: without illustrations the text breaks up into a set of amusing phrases and nothing more. Sendak managed not only to connect the text and the image, but also to significantly expand and supplement the content. The illustration turns into a variation on the theme of each phrase, and the book becomes a collection of short sketches.0006

Hands - to hug. Buttons - for warmth. Lips - so that the crumbs do not fall on the floor. The book - so that you can look at it, etc. This work showed the artist's ability to cement, combine text and image into a single whole. In this case, this was especially important: without illustrations the text breaks up into a set of amusing phrases and nothing more. Sendak managed not only to connect the text and the image, but also to significantly expand and supplement the content. The illustration turns into a variation on the theme of each phrase, and the book becomes a collection of short sketches.0006

#10

Sendak-6.jpg

From 1951-1962 Maurice Sendak illustrated over 40 books. While American illustrators were increasingly fascinated by the play of color, abstraction and various forms of non-realistic art, Sendak, on the contrary, is increasingly turning to the traditions of the 18th and 19th centuries, he is attracted by the clarity of lines, thin shading and muted tones. He studies the works of Dürer, Hogarth, Blake, Bush, creatively transforms the finds of old masters in his works. The artist is especially admired by the works of English illustrators of the 19th century, primarily the work of Randolph Caldecott and George Cruikshank.

He studies the works of Dürer, Hogarth, Blake, Bush, creatively transforms the finds of old masters in his works. The artist is especially admired by the works of English illustrators of the 19th century, primarily the work of Randolph Caldecott and George Cruikshank.

#11

Sendak-5.jpg

Passion for book graphics of the 19th century, led to the creation of illustrations for a series of books by Elsie Homeland Minarik about the little bear cub. The artist does not just imitate the technique of an old engraving, but transfers the action of a fairy tale to Victorian England, placing the heroes (a family of bears!) In the atmosphere of Victorian life, dressing them in costumes of that era and, which is especially difficult, made the bears behave like respectable Victorians: their gestures , facial expressions, facial expressions (or muzzles?) - all of 19century. Maurice Sendak explained the choice of the era in this way: “I would like the mother bear to become the embodiment of warmth and strength, the embodiment of motherhood. And I dressed her in a Victorian dress, because the puffy skirts and sleeves, as well as her magnificent figure, all embody the stability and comfort that I sought to emphasize.

And I dressed her in a Victorian dress, because the puffy skirts and sleeves, as well as her magnificent figure, all embody the stability and comfort that I sought to emphasize.

#12

Sendak-24.jpg

In the fifties, a special manner of the artist to depict children was also formed: the little heroes of Sendak are usually stocky, as if a little flattened, round-faced, their eyes often remain sad, even when they are having fun, sometimes they are larger look like small adults than children. Responding to critics’ comments about the frequent portrait resemblance between the characters and their creator, Sendak admitted: “Yes, they are all kind of caricatures of myself ... They are ordinary children who grew up in Brooklyn and aged ahead of time ... Some of them look askance, as if they are carrying shoulders the burden of life.

#9

In 1956, the first book appeared, where Maurice Sendak acts not only as an artist, but also as a writer - Kenny and His Window. Little boy Kenny is trying to find answers to the questions that a four-legged rooster asked him in a dream: Can you see the horse on the roof? Can a broken promise be fixed? What does it mean to be miraculously saved? and others. If the boy finds the answers, he can live forever in a garden where the sun and moon shine at the same time, where you don't have to go to bed, where you can live forever. In search of answers to these questions, the boy gradually solves other problems that worry him. This is a fantasy book where dream, game and reality are mixed. All illustrations in the book are in muted brown tones. According to tradition, it is customary for children to see blue and pink dreams, and live in a bright world, with Sendak it is the other way around. But the illustrations do not seem gloomy - they are light and airy, only a little sad.

Little boy Kenny is trying to find answers to the questions that a four-legged rooster asked him in a dream: Can you see the horse on the roof? Can a broken promise be fixed? What does it mean to be miraculously saved? and others. If the boy finds the answers, he can live forever in a garden where the sun and moon shine at the same time, where you don't have to go to bed, where you can live forever. In search of answers to these questions, the boy gradually solves other problems that worry him. This is a fantasy book where dream, game and reality are mixed. All illustrations in the book are in muted brown tones. According to tradition, it is customary for children to see blue and pink dreams, and live in a bright world, with Sendak it is the other way around. But the illustrations do not seem gloomy - they are light and airy, only a little sad.

#13

Illustration_by_Maurice-Sendak_from_THE-SIGN-ON-ROSIE'S-DOOR_illustrationupclose.com.jpg

in 1958, "Note on Rosie's Door" appeared, where Sendak for the first time directly refers to his Brooklyn impressions. The book was born from the artist's observations of children playing in the courtyard of his house, it also reflects the author's childhood memories: fantasies and games that allowed the boy to pass the time during frequent illnesses. The heroine of the book, dreamer Rosie, has the gift of transforming and coloring the boring and monotonous life of street kids. The author admires the cheerfulness of the girl, her ability to captivate other children with her fantasies. Rosie is a born artist, and, in fact, this book is about the artist's magical gift to change the world with the power of his own imagination. Like any artist, Rosie is a tragic figure: success is replaced by neglect, the girl has to experience loneliness and misunderstanding, but the strength and attraction of the heroine lies in her resolute refusal to admit defeat, to reconcile.

The book was born from the artist's observations of children playing in the courtyard of his house, it also reflects the author's childhood memories: fantasies and games that allowed the boy to pass the time during frequent illnesses. The heroine of the book, dreamer Rosie, has the gift of transforming and coloring the boring and monotonous life of street kids. The author admires the cheerfulness of the girl, her ability to captivate other children with her fantasies. Rosie is a born artist, and, in fact, this book is about the artist's magical gift to change the world with the power of his own imagination. Like any artist, Rosie is a tragic figure: success is replaced by neglect, the girl has to experience loneliness and misunderstanding, but the strength and attraction of the heroine lies in her resolute refusal to admit defeat, to reconcile.

#14

Maurice Sendak's first books are distinguished by their novelty of attitude to the child, they are devoid of sweetness and tenderness, they are light, but not careless, on the contrary, they feel an inner tragedy: little heroes face the disorder of the adult world one on one, they are deprived of support elders, the only support of the child is fantasy. Critics noted the excessive gloom of the author's vision. But Sendak countered: “Too many parents and too many children's writers ignore the fact that children often suffer. My children are very cheerful, but under an hour and defenseless too. Defenselessness is the hallmark of childhood. And I often try to draw what children feel, or rather, how I imagine their feelings, that is, how I felt when I was a child. Perhaps this is the main distinguishing feature of the worldview of Maurice Sendak: he perceives childhood as a difficult and dangerous period of life, of course, wonderful and cheerful too, but ... The artist completely rejects the idea of childhood as a cloudless golden age, his view is closer to folk various trials lie in wait at every step, "fire, water and copper pipes

Critics noted the excessive gloom of the author's vision. But Sendak countered: “Too many parents and too many children's writers ignore the fact that children often suffer. My children are very cheerful, but under an hour and defenseless too. Defenselessness is the hallmark of childhood. And I often try to draw what children feel, or rather, how I imagine their feelings, that is, how I felt when I was a child. Perhaps this is the main distinguishing feature of the worldview of Maurice Sendak: he perceives childhood as a difficult and dangerous period of life, of course, wonderful and cheerful too, but ... The artist completely rejects the idea of childhood as a cloudless golden age, his view is closer to folk various trials lie in wait at every step, "fire, water and copper pipes

#15

Sendak-7.jpg

In the sixties, Maurice Sendak continued to explore the various possibilities of the picture book genre. In 1962, he created a series of four miniature books called "Tiny Library", which included: the comic alphabet "Alligators are everywhere", the counting rhyme "One is Johnny", the funny calendar "Bouillon with Rice" and the fairy tale "Pierre". Sendak chooses traditional genres of children's literature, which under the artist's brush, as if by magic, are transformed, acquiring new original features. In this work, for the first time, the comic gift of the artist manifested itself in full force.

Sendak chooses traditional genres of children's literature, which under the artist's brush, as if by magic, are transformed, acquiring new original features. In this work, for the first time, the comic gift of the artist manifested itself in full force.

#16

A1wx+e0rJ2L.jpg

1963 is a decisive year for Maurice Sendak. The artist creates a book that brings him worldwide fame - "Where the monsters live." The new book is the result of a long preparatory work (the first concept of the book dates back to 1955). Many years of studying the possibilities of book illustration led Sendak to create a new genre - picture books, where text and image are inextricably merged, carry an equal semantic load, mutually complement each other .

Maurice Sendak is not just an artist who writes text for his pictures, he treats word and image with equal seriousness.

#24

Poorly written books annoy me. The picture book is an amazingly poetic genre, and it must be treated with the greatest respect. Writing is more personal and more difficult. I know, if not for the words, I would never have become an illustrator. I never took up a book if I didn't like the text. I work on my own texts until I bring them to perfection, only then do I take up illustrations.

The picture book is an amazingly poetic genre, and it must be treated with the greatest respect. Writing is more personal and more difficult. I know, if not for the words, I would never have become an illustrator. I never took up a book if I didn't like the text. I work on my own texts until I bring them to perfection, only then do I take up illustrations.

Maurice Sendak

#22

The book begins with the fact that little Max, a boy of 4-5 years old, dressed up in a wolf costume, got so naughty that his mother calls him a “monster” in her heart and sends him to bed without supper. But the boy's bedroom suddenly magically turns into an enchanted forest inhabited by wild monsters. Max manages to pacify them, the monsters even choose the boy as their king, and arrange wild jumps and dances to celebrate. In the midst of the fun, Max suddenly feels that he misses home very much and sets off on the return voyage to his own bedroom, where dinner awaits him.

#21

61424242314777CCD6666CB1A77D869B52E9D29D881E0. jpeg

jpeg

Stronging to strengthen emotional tension, keep the figures of monsters and a boy, tries to clearly show how ordinary shafts are re -pampering (not up to Max) gradually subsides towards the last page, the tense dynamism of the previous scenes is replaced by peace and tranquility. The composition of each scene is built in such a way that the reader is, as it were, inside the image, and thus becomes a participant in all adventures. The artist's palette has become richer and brighter, but the clarity of lines and fine shading are preserved in this work.

#23

a096414f9afc8a748a6043feafb74825.jpg it should not be given to a tender and sensitive child. The little mischievous Max, who threatens to eat his own mother, cannot be allowed into the children's bedrooms. Books like these can give children nightmares.

#26

Sendak-10.jpg

Despite the obvious disapproval of some of the reading public, Where the Monsters Live was an undoubted success. Perhaps this is the first real children's bestseller that has received truly worldwide recognition: for decades, "Monsters" have been reprinted in huge numbers, the book has been translated into dozens of languages, it is read with equal enthusiasm in different countries, not only by children, but also by adults from among the most brave. One eight-year-old boy wrote to Maurice Sendak: “How much does it cost to travel to the country where the monsters live? If it's not too expensive, my sister and I would like to go there for the summer."

Perhaps this is the first real children's bestseller that has received truly worldwide recognition: for decades, "Monsters" have been reprinted in huge numbers, the book has been translated into dozens of languages, it is read with equal enthusiasm in different countries, not only by children, but also by adults from among the most brave. One eight-year-old boy wrote to Maurice Sendak: “How much does it cost to travel to the country where the monsters live? If it's not too expensive, my sister and I would like to go there for the summer."

#27

In 1964, for Where the Beasts Live, Maurice Sendak was awarded the Caldecott Medal, the highest award given annually to the best American children's book illustrator. In a speech at the award ceremony, Sendak said: “We strive to protect our children from new painful experiences, we are afraid to hurt the child, to excite him ... Our concern is understandable ... At the same time, we do not notice that from the earliest emotions, that fears and anxieties are an integral part of their lives, that they again and again try to overcome the feeling of despair in themselves. And it is fantasy that helps children achieve catharsis. It is fantasy that helps them tame the wild Monsters. I have always been concerned about this aspect of childhood - the terrible vulnerability of children, and their desire to become Lords of the Wild Monsters at all costs. And it is these properties that give truthfulness and passion to my work. ".

And it is fantasy that helps children achieve catharsis. It is fantasy that helps them tame the wild Monsters. I have always been concerned about this aspect of childhood - the terrible vulnerability of children, and their desire to become Lords of the Wild Monsters at all costs. And it is these properties that give truthfulness and passion to my work. ".

#28

Sendak-2.jpg

Childhood memories: first impressions from trips to Manhattan to the magical world of cinema, advertising, music and delicious food, however, like night terrors and loneliness formed the basis of the book "In the kitchen at night" (1970). The graphic form of the new book was suggested to the artist by a visit to an exhibition of comics by W. McKay. Sendak never hid his childhood passion for comics and other pop products. Defending his children's favorites, he emphasized that a hobby that was harmful from the point of view of modern parents and teachers did not prevent him from growing into serious literature and forever remaining a passionate book reader. It is no coincidence that the hero of the book - the boy Mickey - is the namesake of the great Mickey Mouse, he is similar in character to him - brave, resourceful, curious.

It is no coincidence that the hero of the book - the boy Mickey - is the namesake of the great Mickey Mouse, he is similar in character to him - brave, resourceful, curious.

#29

"In the kitchen at night" - a child's dream, or rather the dream of an adult (Sendak), who had a dream of his own childhood. What happens in the adult world after children are sent to bed is the mystery that every child seeks to unravel. Sendak admitted that the impetus for the creation of the book was the memory of an advertisement for bread seen in childhood "We bake while you sleep." The boy passionately wanted to see, at least with one eye, how this was happening.

Little Mickey, waking up at night, miraculously falls through the underground and, flying several floors, finds himself in the kitchen, where he falls right into the dough, from which the three chefs are going to bake a cake. Happily avoiding the oven, the boy even helps the cooks get milk for the dough by flying across the Milky Way in a bread crumb plane. Finally, the dough is ready, which means there will be a delicious pie for breakfast at home. The boy returns to bed. "And so, thanks to Mickey, we always have pie for breakfast."

Finally, the dough is ready, which means there will be a delicious pie for breakfast at home. The boy returns to bed. "And so, thanks to Mickey, we always have pie for breakfast."

A nighttime kitchen transformed by an artist into a fantasy city, where historic milk cartons, cans and bottles are transformed into New York skyscrapers. The city-dream keeps the memory of the most important events in the life of Sendak - here on the bag of flour are the years of the life of the artist's beloved dog, here on the giant bag of cream are two addresses where the artist lived in childhood, and here on the box is the date of birth of the author himself: "Patented on June 10 1928".

"In the Kitchen at Night" is stylistically unlike any of the artist's previous works, although the theme of childhood in New York and childhood dreams has already been developed by Sendak before. In this work, Sendak openly declared the close connection of his work with the traditions of mass culture of the 30s:

#30

I kept myself on the classic diet for a long time: Blake, English illustrators, Melville, but those simple toys and tinsel films of the 30s are undoubtedly much more closely connected with my life than W. Blake, although Blake's influence is also undoubtedly important, one might say this is my cornerstone. No one before him told me that childhood is so serious... But the material that I turned to now is the art on which I grew up. It shaped me... all those movies and Mickey Mouse. I love them! I love!

Blake, although Blake's influence is also undoubtedly important, one might say this is my cornerstone. No one before him told me that childhood is so serious... But the material that I turned to now is the art on which I grew up. It shaped me... all those movies and Mickey Mouse. I love them! I love!

Maurice Sendak

#31

"In the Kitchen at Night" is not as popular as "Where the Monsters Live", and this is understandable: the book is too autobiographical, created too "for itself" and at the same time so complex and multifaceted, it can be seen more as an artistic experiment, a "literary monument" than as an entertaining children's reading.

#32

91UQyQSqFnL.jpg

In 1981, a new picture book by Maurice Sendak "There, in the distance" was published, the main theme of the new work was children's loneliness, confrontation and confrontation between the adult world and the world of the child.

Critics have not accidentally combined the three books "Where the Monsters Live", "In the Kitchen at Night" and "Out There" into a trilogy. Sendak did not hide the connection between these books: "They are all variations of the same theme: how children cope with various feelings - anger, boredom, fear, despair, jealousy - and how they assert themselves in the real world." In one of the interviews, the artist admitted that the third book is the most unusual. Monsters now seems like a very simple book, maybe simplicity is the secret of their success, but I will never be able to return to such a simple form. I like “Night Kitchen” more, where the story unfolds on two levels, as it were. But this third book will have three levels.”

#33

The heroine of the book, the girl Ida, is forced to watch over her younger brother, as her father has gone on a long voyage, and her mother is so worried about separation that she does not notice anything around. Caring for her brother weighs on the girl, and as soon as she is distracted for a moment, the child is kidnapped by evil goblins. Ida goes in search of her brother and eventually saves him. The kidnapping of a child is not only a common fairy tale plot, perhaps suggested to the artist by the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, on which he worked in the 70s, but also the cruel reality of the modern adult world into which the child enters so defenseless. Sendak seeks to show the complexity of the heroine's experiences, her loneliness, a sense of abandonment, jealousy for her younger brother and an awakening sense of responsibility that made her make a magical flight to the land of goblins in order to save her brother, and thereby the family, which, as it were, fell apart after her father sailed away. The second psychological plan of the book is again, as in "In the Kitchen at Night", filled with childhood memories. So, Sendak admitted that in the image of Ida there is a lot from his sister Netley, who also had to look after her brothers.

Ida goes in search of her brother and eventually saves him. The kidnapping of a child is not only a common fairy tale plot, perhaps suggested to the artist by the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, on which he worked in the 70s, but also the cruel reality of the modern adult world into which the child enters so defenseless. Sendak seeks to show the complexity of the heroine's experiences, her loneliness, a sense of abandonment, jealousy for her younger brother and an awakening sense of responsibility that made her make a magical flight to the land of goblins in order to save her brother, and thereby the family, which, as it were, fell apart after her father sailed away. The second psychological plan of the book is again, as in "In the Kitchen at Night", filled with childhood memories. So, Sendak admitted that in the image of Ida there is a lot from his sister Netley, who also had to look after her brothers.

#34

The third layer of the book is symbolic, the book is permeated with allegories and symbols, which turns a simple plot into a deep and complex work that has absorbed a variety of images: literary, artistic, musical. Music has always been a source of inspiration for Maurice Sendak, accompanied the birth of all his works, evoking and reviving childhood memories, spurring the imagination. “I connect text and image, just like a composer connects words and music,” Sendak admitted. In "There in the distance" it is permeated with the music of Mozart, primarily with the melodies of the "Magic Flute". The illustrations often resemble opera scenery; in one of the scenes, Sendak even depicted a brilliant composer at work.

Music has always been a source of inspiration for Maurice Sendak, accompanied the birth of all his works, evoking and reviving childhood memories, spurring the imagination. “I connect text and image, just like a composer connects words and music,” Sendak admitted. In "There in the distance" it is permeated with the music of Mozart, primarily with the melodies of the "Magic Flute". The illustrations often resemble opera scenery; in one of the scenes, Sendak even depicted a brilliant composer at work.

"There in the distance" differs significantly from the previous two books: it is darker, there is no place for humor in it. The intonation of the text changes, the cheerful rhythm of the old books is replaced by a sad melody.

#62

il_fullxfull.1894425171_bpok.jpg

A special place in the work of Maurice Sendak is occupied by English children's poetry, the so-called "Mother Goose Songs". Poems created many years ago lost their original meaning in an hour, but in this way they give the artist the opportunity to fantasize freely, to create his own plot. Sendak was always attracted by the extraordinary figurativeness of folk poetry, its amazing rhythm. The artist specially collected and studied various publications, compared the works of different illustrators, and even wrote an article about it. Sendak particularly appreciated the illustrations by Randolph Caldecott, noting not only the elegance and liveliness of the English master, but also his serious attitude to the word, his ability to transform the text, creating his own original plot on its basis. "He could take a quatrain, devoid of any meaning, and turn it, without falling into moralizing and sentimentality, into a real book filled with deep content." The main merit of Caldecott, whom Sendak considers the founder of the genre of picture books, was the ability to combine text and image in such a way that they seem to complement each other: what is not said in words is conveyed through the image, and vice versa.

Sendak was always attracted by the extraordinary figurativeness of folk poetry, its amazing rhythm. The artist specially collected and studied various publications, compared the works of different illustrators, and even wrote an article about it. Sendak particularly appreciated the illustrations by Randolph Caldecott, noting not only the elegance and liveliness of the English master, but also his serious attitude to the word, his ability to transform the text, creating his own original plot on its basis. "He could take a quatrain, devoid of any meaning, and turn it, without falling into moralizing and sentimentality, into a real book filled with deep content." The main merit of Caldecott, whom Sendak considers the founder of the genre of picture books, was the ability to combine text and image in such a way that they seem to complement each other: what is not said in words is conveyed through the image, and vice versa.

#37

Sendak-3.jpg

Admiration for the skill of Randolph Caldecott made Sendak want to create his own picture book based on Mother Goose's poems. This is how Hector Protector and When I Sailed the Sea (1965) were born. “I acted in the traditional manner of Caldecott. I started with one stanza, the first line, and turned it into a series of pictures. The first stanza gave material for a whole stream of images. When I completed work on the first stanza and moved on to the next, it gave a new impetus to my imagination, the same happened with the third stanza and the fourth. I just made up a story in pictures that fit in four lines, which was great, because the poem itself did not give any clue what it was actually talking about ”

This is how Hector Protector and When I Sailed the Sea (1965) were born. “I acted in the traditional manner of Caldecott. I started with one stanza, the first line, and turned it into a series of pictures. The first stanza gave material for a whole stream of images. When I completed work on the first stanza and moved on to the next, it gave a new impetus to my imagination, the same happened with the third stanza and the fourth. I just made up a story in pictures that fit in four lines, which was great, because the poem itself did not give any clue what it was actually talking about ”

#38

Hector Protector all green

Protector Hector appeared before the throne,

Alas, the king did not like him,

And Protector Hector went out.

Maurice Sendak "Hector Protector", translated by Samuil Marshak

#39

What is the meaning of this poem? What happened there between Hector Protector and the king? Why did the former so anger the latter? We will never know the historical basis of this little poetic masterpiece. Readers are attracted by a funny absurdity, fascinated by the rhythm of the verse, in fact, he does the same as the illustrator: he comes up with his own story.

Readers are attracted by a funny absurdity, fascinated by the rhythm of the verse, in fact, he does the same as the illustrator: he comes up with his own story.

Maurice Sendak turned a short poem into a series of comic book-like pictures. In fact, the plot is presented not in words, but in drawings, and the text brings rhythm and movement to the book. The artist came up with and drew several versions of the story, the final one - Victorian - was chosen not only because the Victorian era always attracted the attention of the artist, but also because it made it possible to create a funny situation by drawing Queen Victoria herself - the personification of English common sense and respectability into an absurd situation.

#41

s-l1600.jpg

Mother Goose's poems formed the basis of Maurice Sendak's most profound and sad book "Higglety-Pigglety-Plu" (1967), dedicated to the memory of his beloved dog, the Seliham Terrier Jenny. Not wanting to put up with the death of a beloved creature, Sendak composes a fairy tale about a dog in which Jenny does not die, no. Feeling a strange longing and anxiety, the dog leaves the cozy reliable shelter where she was loved, where she seemed to have everything: two pillows, brush and comb, drops for eyes and ears, a thermometer, two bowls, two windows to look at the street, and even a wonderful woolen red sweater.Jenny suddenly realizes that it is not enough to have everything, there is something more important in life. she goes through a difficult life school, commits a selfless act, saves a child, and eventually becomes a prima donna in the magical Mother Goose Theater. The book is riddled with light irony and light sadness. A surprisingly poetic text elegant illustrations made in the style of book engravings 19centuries, they seem light and ghostly. The image takes on a resemblance to an old photograph, where the bygone time, in which people (and dogs) lived, and which we still remember, is forever stopped.

Not wanting to put up with the death of a beloved creature, Sendak composes a fairy tale about a dog in which Jenny does not die, no. Feeling a strange longing and anxiety, the dog leaves the cozy reliable shelter where she was loved, where she seemed to have everything: two pillows, brush and comb, drops for eyes and ears, a thermometer, two bowls, two windows to look at the street, and even a wonderful woolen red sweater.Jenny suddenly realizes that it is not enough to have everything, there is something more important in life. she goes through a difficult life school, commits a selfless act, saves a child, and eventually becomes a prima donna in the magical Mother Goose Theater. The book is riddled with light irony and light sadness. A surprisingly poetic text elegant illustrations made in the style of book engravings 19centuries, they seem light and ghostly. The image takes on a resemblance to an old photograph, where the bygone time, in which people (and dogs) lived, and which we still remember, is forever stopped. If in previous works Maurice Sendak always strived for dynamic drawing, here, on the contrary, he deliberately slows down the action, everything happens like in a dream, or like in a fairy tale...

If in previous works Maurice Sendak always strived for dynamic drawing, here, on the contrary, he deliberately slows down the action, everything happens like in a dream, or like in a fairy tale...

#43

has its own melody, only this time it's a sad song. In the book, we again meet a child abandoned by his parents. Jenny's little pupil surprisingly resembles Sendak in childhood, and this is no coincidence: he himself is a lonely abandoned child, shocked by the almost simultaneous death of his mother and beloved dog. And as if to console himself, Sendak composes an epilogue of the book, a fabulous happy ending.

#48

Now Jenny has everything. She is the brightest actress who has ever performed on the stage of the Mother Goose Theatre. She is a real star. She performs every day, and even twice on Saturdays. She found inner peace.

One day Jenny wrote a letter to her master.

Maurice Sendak "Higglety Pigglety Plu"

#49

You obviously already understood that I left forever. I have gained life experience. I became famous and even became a star. Every day I swallow a broom, and on Saturdays even twice. The broom is made of salami, you remember how much I loved it. I have plenty of food and drink, so don't worry. I can't tell you where Yonder Castle is, and I don't know it myself. But if you ever wander into these parts, look for me

I have gained life experience. I became famous and even became a star. Every day I swallow a broom, and on Saturdays even twice. The broom is made of salami, you remember how much I loved it. I have plenty of food and drink, so don't worry. I can't tell you where Yonder Castle is, and I don't know it myself. But if you ever wander into these parts, look for me

The cat mumbles

Higletty Pigletty Plu!

Maurice Sendak, translated by O. Mäeots

#52

The appeal to the poems of Mother Goose in this work is extremely important for Sendak: he draws life energy from folklore material, which allows him to overcome the fear of death, helps to overcome the feeling of loneliness and despair , and besides, it gives the whole book an additional philosophical meaning, turning a sad tale into a parable about life and death, love and separation.

#45

Sendak-20.jpg

In 1992, Maurice Sendak again turns to the texts of Mother Goose. He receives an offer from the famous collector of English children's folklore, Jonah Opie, to prepare illustrations for a collection of school songs, rhymes, teasers and sayings. Sendak gladly sets to work. The collection “I Saw ISO” differs from the artist’s previous works: if in previous books, text and image usually carried an equal load, mutually complementing each other, then in this case the emotional charge of the text is so great that the artist, as it were, is not needed. Feeling this, Sendak deliberately fades into the background, but not because he recognizes his own helplessness, but because he understands: in this case, he himself needs freedom.

He receives an offer from the famous collector of English children's folklore, Jonah Opie, to prepare illustrations for a collection of school songs, rhymes, teasers and sayings. Sendak gladly sets to work. The collection “I Saw ISO” differs from the artist’s previous works: if in previous books, text and image usually carried an equal load, mutually complementing each other, then in this case the emotional charge of the text is so great that the artist, as it were, is not needed. Feeling this, Sendak deliberately fades into the background, but not because he recognizes his own helplessness, but because he understands: in this case, he himself needs freedom.

#54

The cover of the book is very strict, it could well be suitable for a respectable memoir or a solid historical novel, and, if not for the cheerful giggling company at the very bottom, the reader would never have guessed what kind of meetings await him on the following pages . External severity is characteristic of many collections of English nonsense; the British take a joke quite seriously: a joke is no joke. But a riotous company hid behind a strict facade, which, traveling from page to page, takes part in all kinds of pranks. Sendak's illustrations in this case resemble children's drawings in the margins of school textbooks, this is both an illustration and a commentary at the same time. The artist almost completely abandons his favorite technique - to develop the plot with the help of illustrations, he contributes very little of himself, perhaps because, having returned to the world of childhood, he found himself on an equal footing with other children, and if you get out and imagine very much, you will be quickly pulled up caustic tease. And yet, despite the seeming "minority" of the illustrations, they are very important. “Sendak's illustrations gave the book additional strength, expanded its boundaries,” notes Iona Opi in the preface.

But a riotous company hid behind a strict facade, which, traveling from page to page, takes part in all kinds of pranks. Sendak's illustrations in this case resemble children's drawings in the margins of school textbooks, this is both an illustration and a commentary at the same time. The artist almost completely abandons his favorite technique - to develop the plot with the help of illustrations, he contributes very little of himself, perhaps because, having returned to the world of childhood, he found himself on an equal footing with other children, and if you get out and imagine very much, you will be quickly pulled up caustic tease. And yet, despite the seeming "minority" of the illustrations, they are very important. “Sendak's illustrations gave the book additional strength, expanded its boundaries,” notes Iona Opi in the preface.

Maurice Sendak was also drawn to the book because it gave him the opportunity to revisit a favorite topic: the complex problem of growing up. The artist admitted that he wanted the book to help the child deal with the disorder of life, so that it would become a kind of catechism for children, so that it could be carried in a pocket and opened when help was needed.

#57

My own attitude towards children is expressed in the language of poetry in the book. This poetry, which belongs to children, contains the ferocious joy with which children meet the trials of life. It expresses the heroism of children. They are so courageous, they can turn even the biggest grief into a joke. It is this property that attracts me most in children, and for this I love them. This is how I try to portray them.

Maurice Sendak

#58

Maurice Sendak admitted that he found in the texts of Mother Goose a worldview close to his own. Paradoxicality, grotesque, spontaneous cruelty and external deliberate rudeness are inherent in folklore, but we also find these features in the artist's work, they caused the greatest attacks from critics. But all these "monsters" in Mother Goose, like in Sendak, are not terrible, they sparkle with joy and love of life.

#59

The realization that I am a part of a centuries-old tradition warmed my heart while working on the book. I am not a loner, not an artist who sets out to scare people.

I am not a loner, not an artist who sets out to scare people.

Maurice Sendak

#60

Sendak-portr.jpg

In recent years, Sendak has turned to book illustration less and less. He teaches, works in film and television, creates costumes and scenery for theatrical productions.

And yet the book remains the main vocation of Maurice Sendak, his favorite thing. Again and again he returns to book illustration, each time creating a work new, unusual and kind in its own way. In a speech at the presentation of the Hans Christian Andersen Medal (1970) Maurice Sendak said: “My main desire is to combine in words and images, truthfully and fantastically, my fate, the Old World, the New World, childhood, my obsession with life, its spirit and artistic images created by my favorite artists. All this together, carefully mixed, turns into picture books, which contain both the immediate beauty of music and a deep unsolved mystery. It's the mystery that attracts me the most.

..

..

“Your master is an idiot,” Hez whispered.

“Your master is an idiot,” Hez whispered.  To which Max almost knocked her down on the spot, and then left the boutique and waited for the girl in the car.

To which Max almost knocked her down on the spot, and then left the boutique and waited for the girl in the car.