There sight word

Teach Your Child to Read

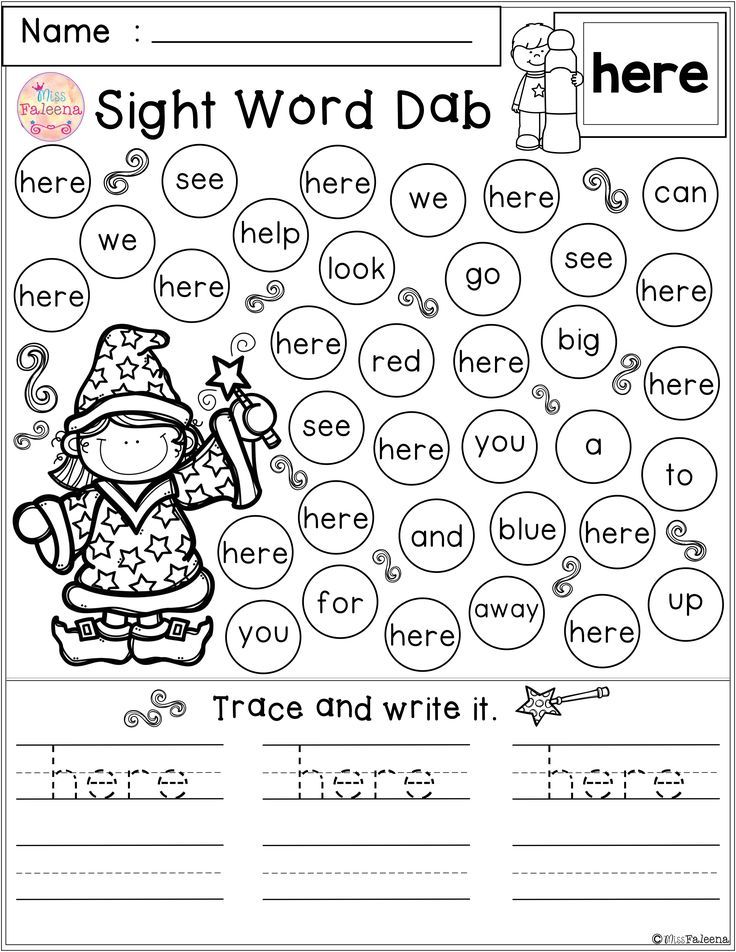

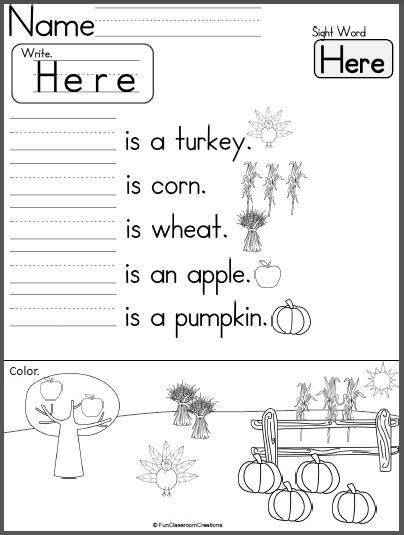

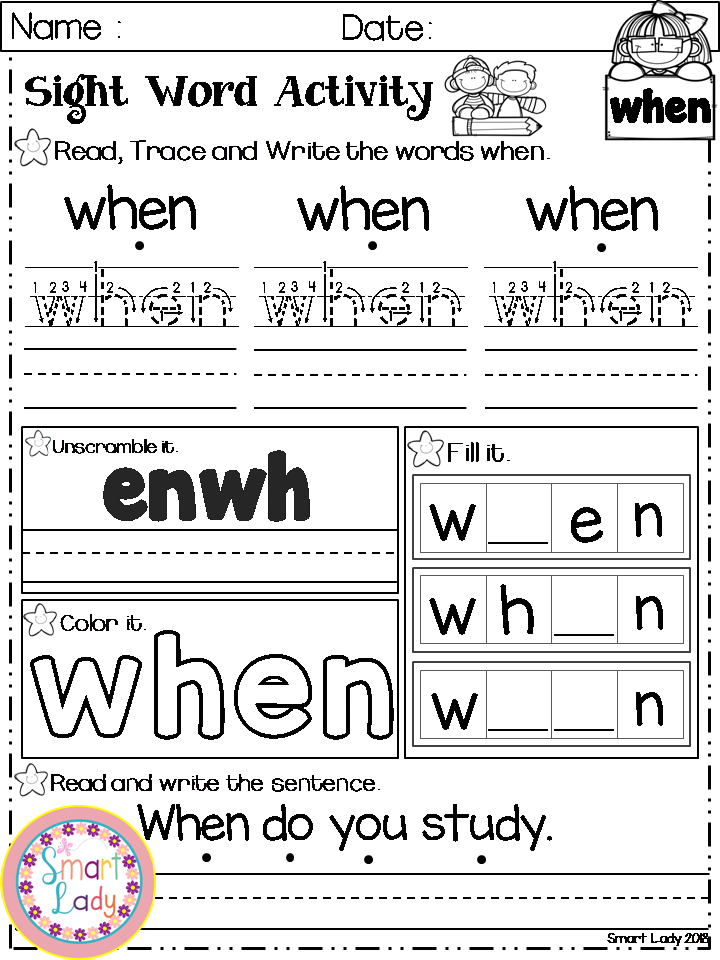

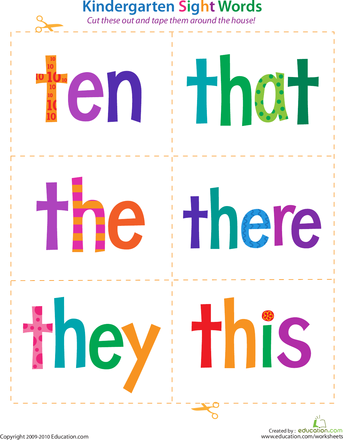

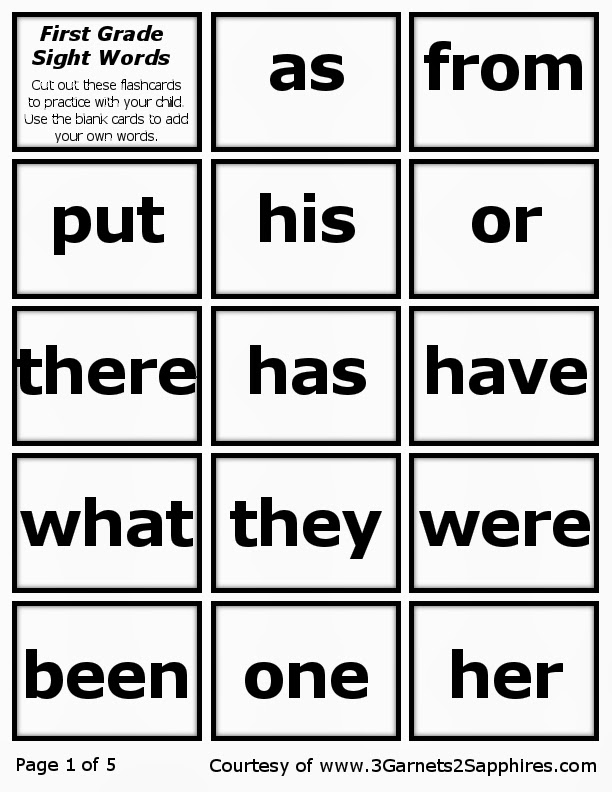

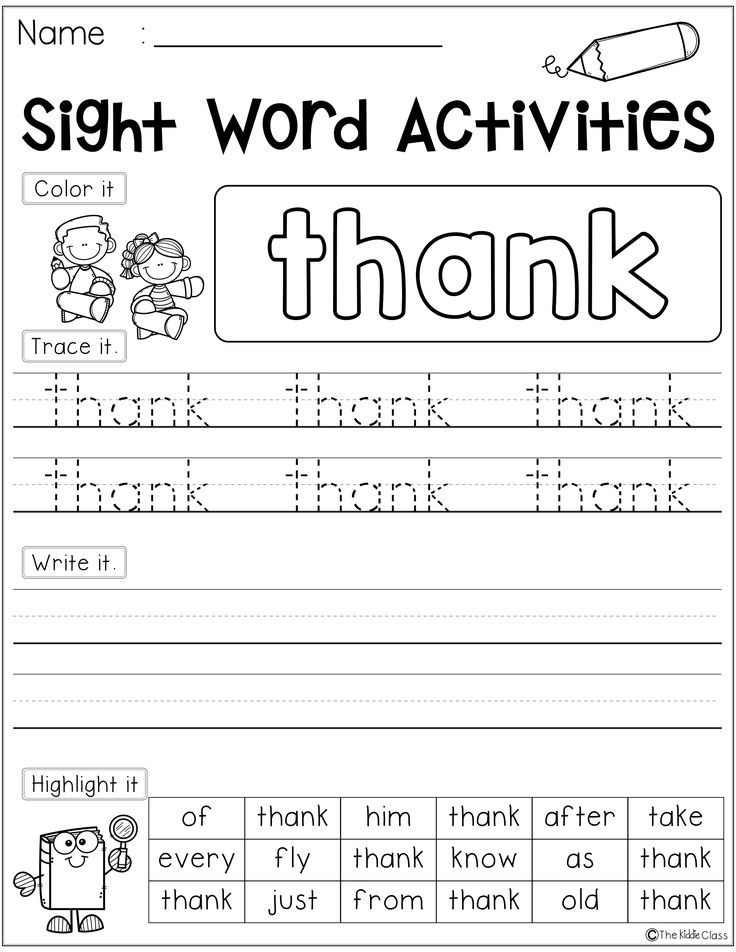

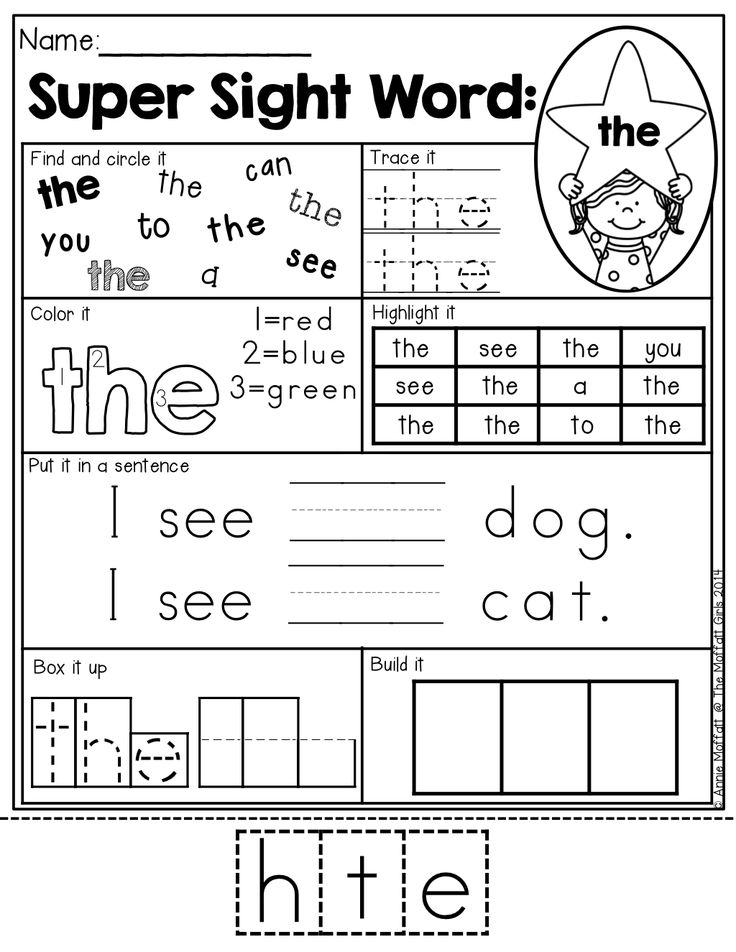

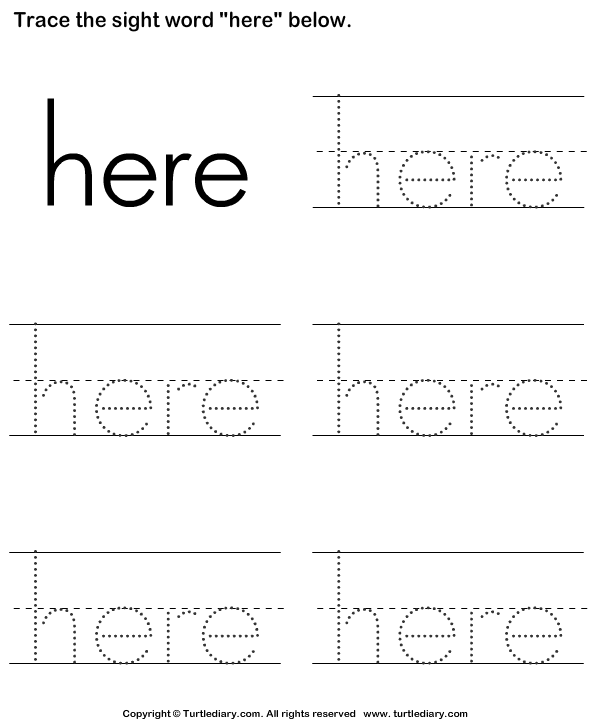

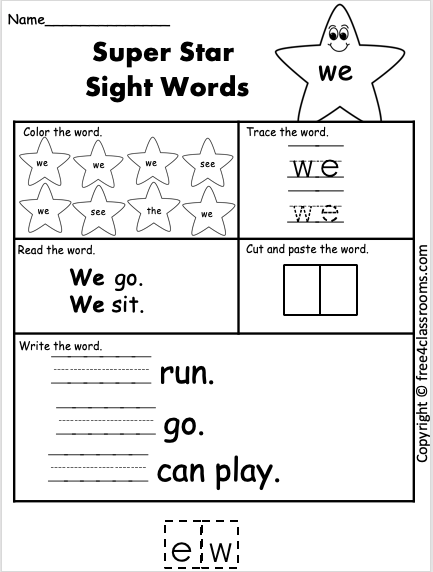

Print your own sight words flash cards. Create a set of Dolch or Fry sight words flash cards, or use your own custom set of words.

More

Follow the sight words teaching techniques. Learn research-validated and classroom-proven ways to introduce words, reinforce learning, and correct mistakes.

More

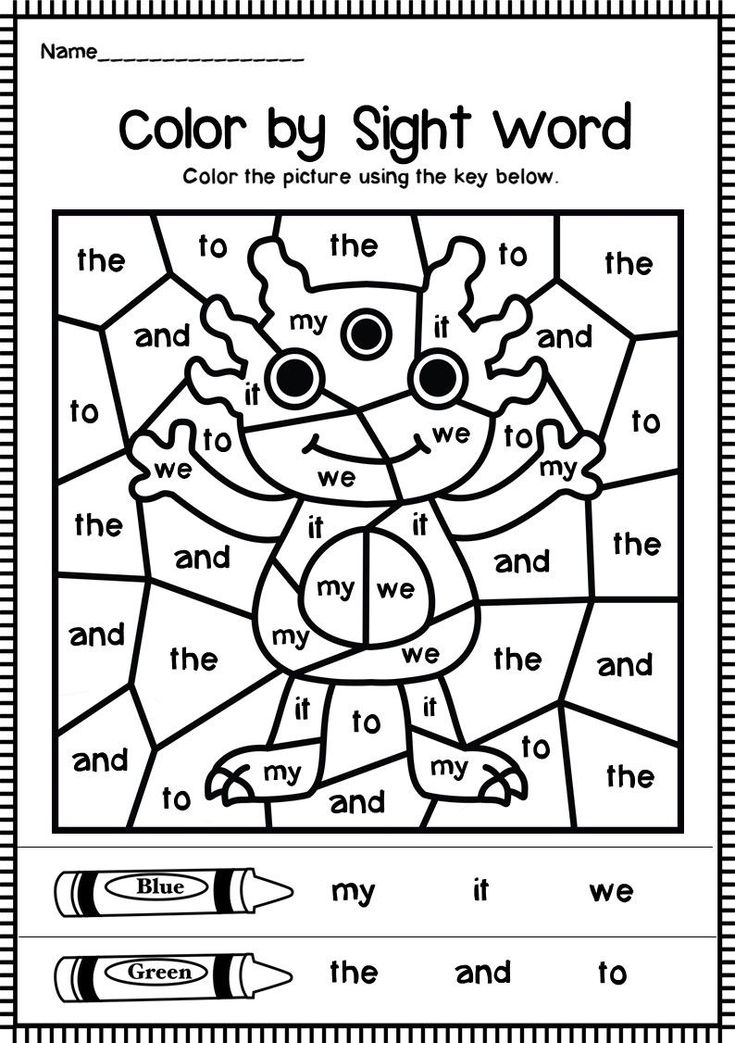

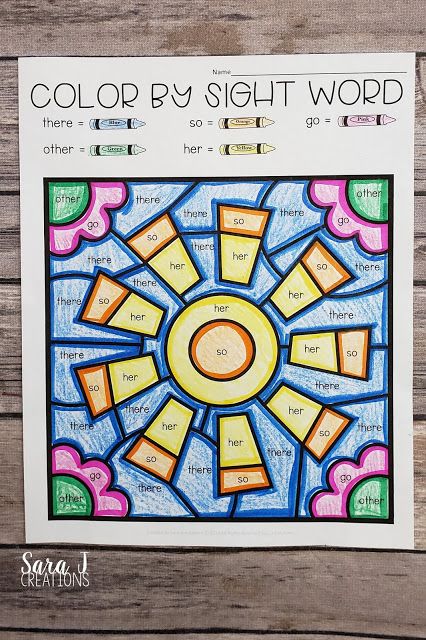

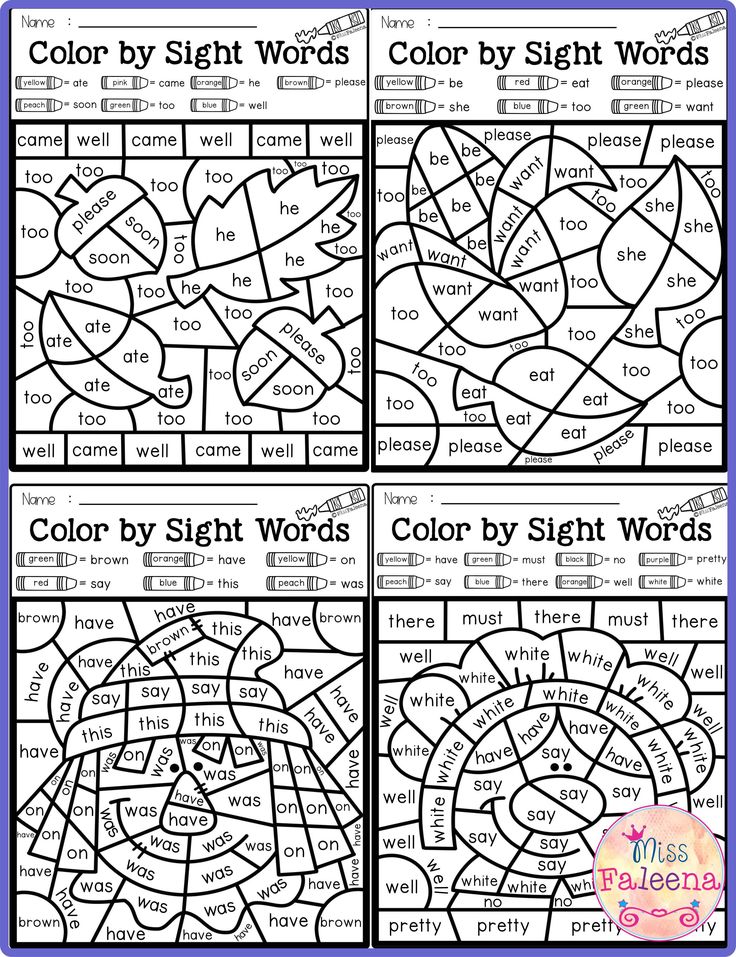

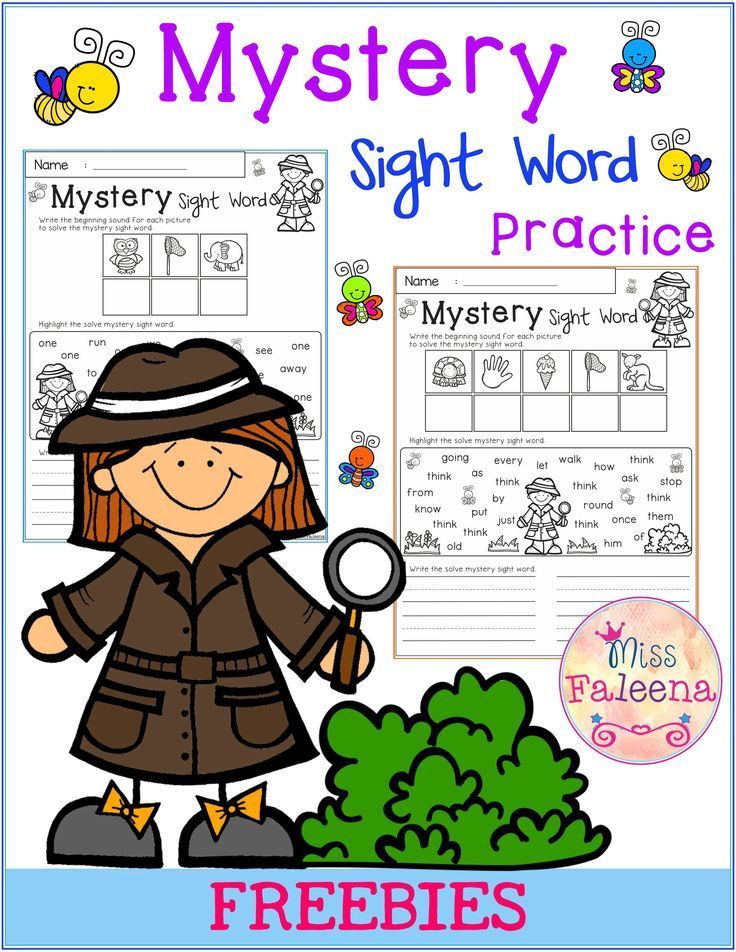

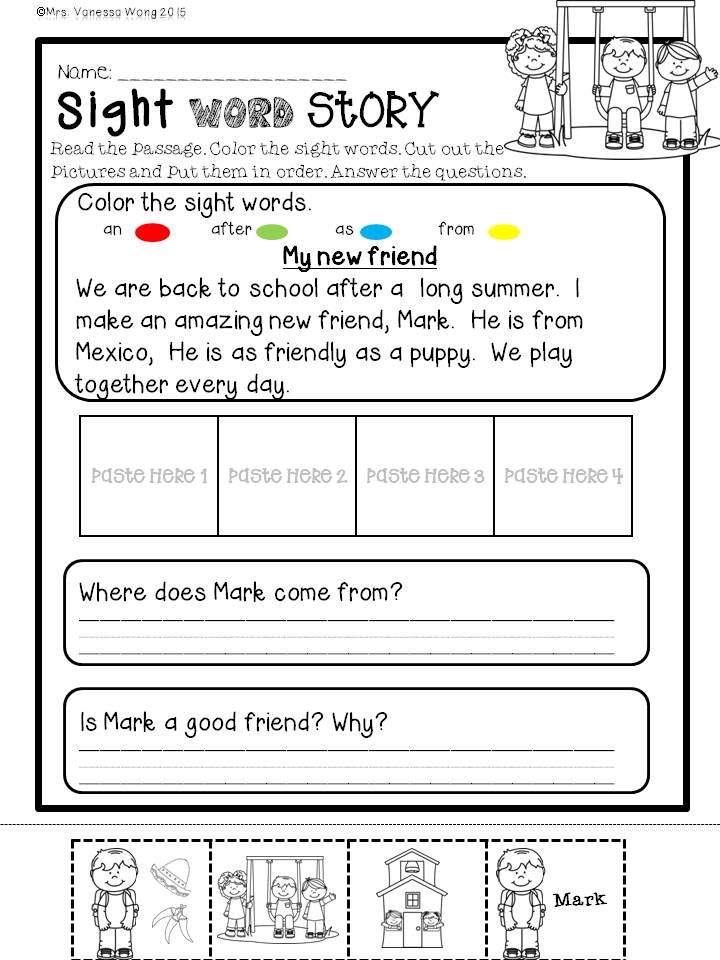

Play sight words games. Make games that create fun opportunities for repetition and reinforcement of the lessons.

More

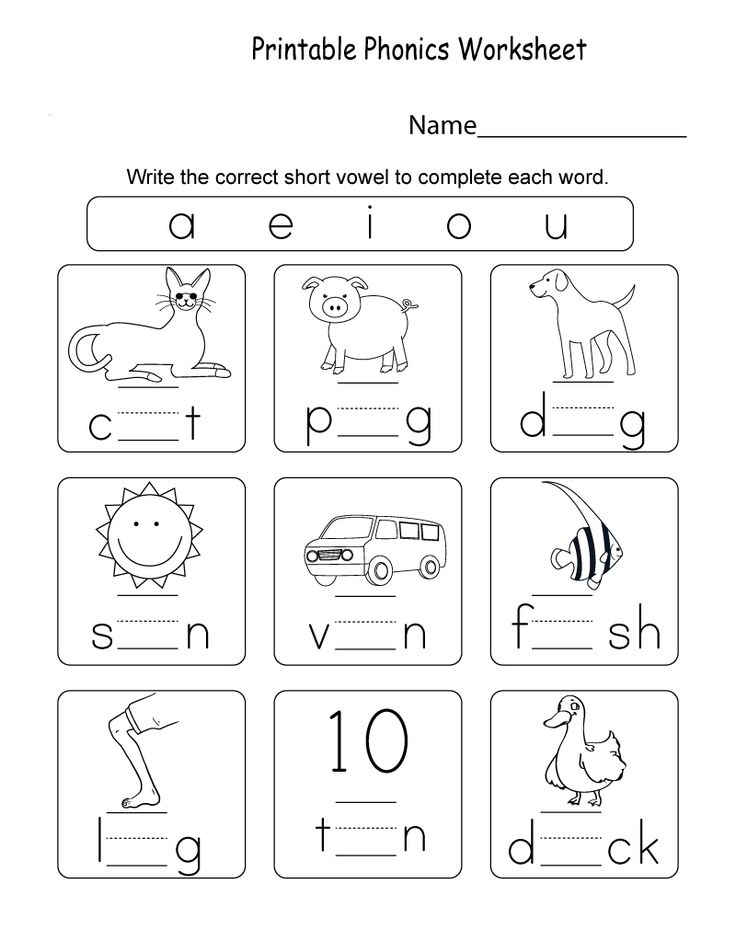

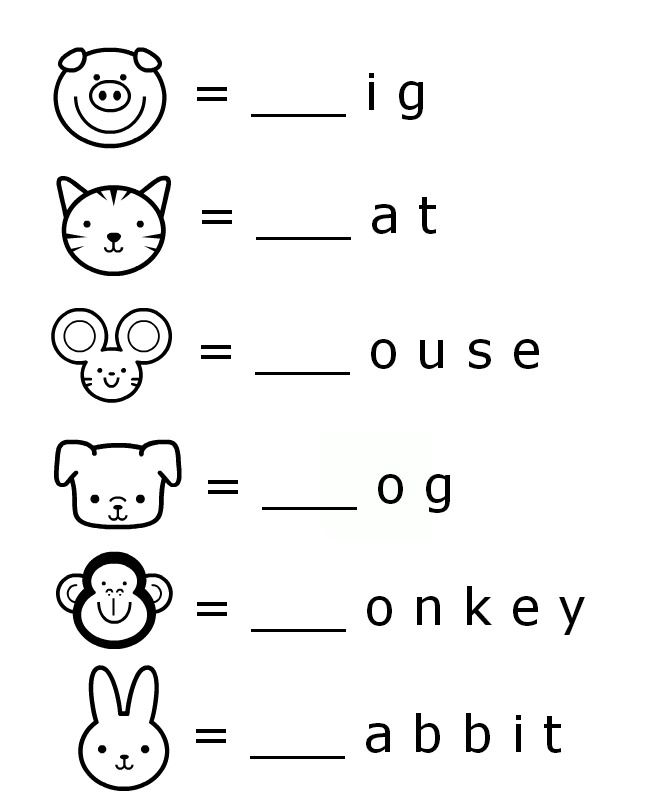

Learn what phonological and phonemic awareness are and why they are the foundations of child literacy. Learn how to teach phonemic awareness to your kids.

More

A sequenced curriculum of over 80 simple activities that take children from beginners to high-level phonemic awareness. Each activity includes everything you need to print and an instructional video.

More

Teach phoneme and letter sounds in a way that makes blending easier and more intuitive. Includes a demonstration video and a handy reference chart.

More

Sightwords.com is a comprehensive sequence of teaching activities, techniques, and materials for one of the building blocks of early child literacy. This collection of resources is designed to help teachers, parents, and caregivers teach a child how to read. We combine the latest literacy research with decades of teaching experience to bring you the best methods of instruction to make teaching easier, more effective, and more fun.

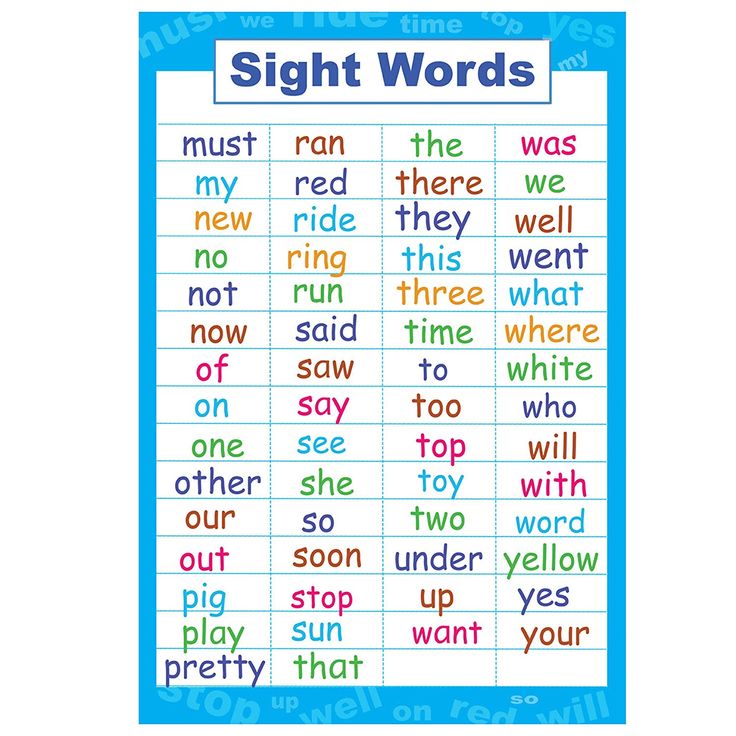

Sight words build speed and fluency when reading. Accuracy, speed, and fluency in reading increase reading comprehension. The sight words are a collection of words that a child should learn to recognize without sounding out the letters. The sight words are both common, frequently used words and foundational words that a child can use to build a vocabulary. Combining sight words with phonics instruction increases a child’s speed and fluency in reading.

This website includes a detailed curriculum outline to give you an overview of how the individual lessons fit together. It provides detailed instructions and techniques to show you how to teach the material and how to help a child overcome common roadblocks. It also includes free teaching aids, games, and other materials that you can download and use with your lessons.

It provides detailed instructions and techniques to show you how to teach the material and how to help a child overcome common roadblocks. It also includes free teaching aids, games, and other materials that you can download and use with your lessons.

Many of the teaching techniques and games include variations for making the lesson more challenging for advanced students, easier for new or struggling students, and just different for a bit of variety. There are also plenty of opportunities, built into the lessons and games, to observe and assess the child’s retention of the sight words. We encourage you to use these opportunities to check up on the progress of your student and identify weaknesses before they become real problems.

Help us help you. We want this to be a resource that is constantly improving. So please provide us with your feedback, both the good and the bad. We want to know which lessons worked for your child, and which fell short. We encourage you to contribute your own ideas that have worked well in the home or classroom. You can communicate with us through email or simply post a response in the comments section of the relevant page.

You can communicate with us through email or simply post a response in the comments section of the relevant page.

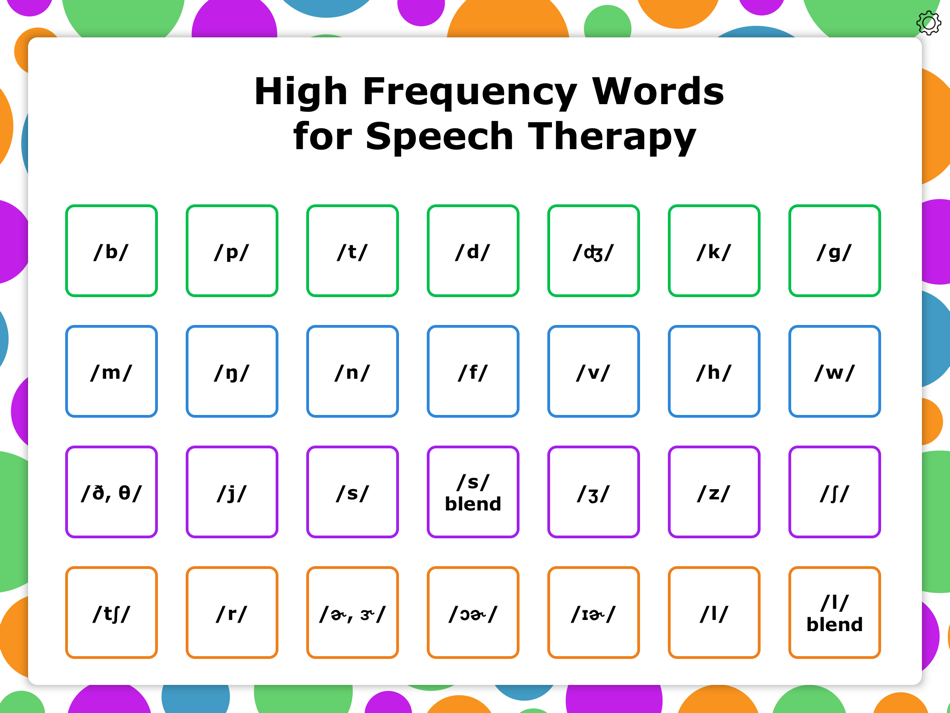

A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words

We have visited many schools to observe intervention lessons and core reading instruction. For years we have been struck that even schools embracing research-based reading instruction teach high-frequency words through rote memorization. It is as if the high-frequency words are a special set of words that need to be memorized and can’t be learned using sound–symbol relationships.

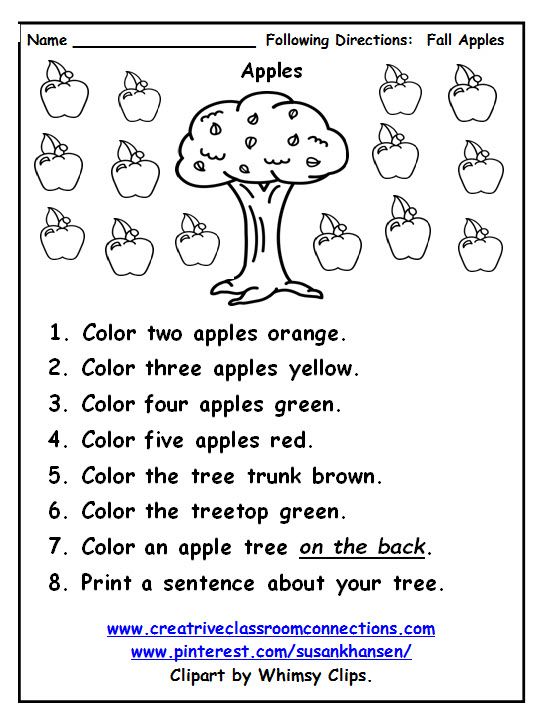

A number of years ago, a teacher we respect enormously asked for help because many of her Tier 2 students and all of her Tier 3 students in first and second grades were failing to learn high-frequency words, even though they were progressing in their phonics lessons. We observed her teaching the digraph th to a group of four Tier 3 first grade students. This lesson was in April. Her students had learned to read CVC words and this was their first lesson with digraphs. The high-frequency words the students were responsible for knowing in this lesson were the color words: blue, red, yellow, orange, purple, and green. None of the four students could spell more than two of the words accurately. All four students had difficulty reading those words when they were mixed into lists with other high-frequency words. (Indeed, they were having difficulty reading all the high-frequency words in the lists.)

The high-frequency words the students were responsible for knowing in this lesson were the color words: blue, red, yellow, orange, purple, and green. None of the four students could spell more than two of the words accurately. All four students had difficulty reading those words when they were mixed into lists with other high-frequency words. (Indeed, they were having difficulty reading all the high-frequency words in the lists.)

These students could read words that followed spelling patterns they had learned and practiced, but they struggled learning words that made no sense to them from a sound–spelling viewpoint. We suggested that the students learn high-frequency words according to spelling patterns, and not according to frequency number or theme.

Together with the teacher, we organized the high-frequency words to fit into the phonics lessons so that the words were tied to spelling patterns students were learning. First, we focused on identifying decodable high-frequency words such as but, him, and yes and integrating them into phonics lessons instead of teaching them as words that had to be memorized. Next, we identified irregularly spelled high-frequency words such as said, you, and from. These words have two or three letter sounds students knew and only one or two letters that had to be memorized. We integrated 2 or 3 of these words into a phonics lessons, and students learned to identify the letters spelled as expected and to learn “by heart” the letters not spelled as expected.

Next, we identified irregularly spelled high-frequency words such as said, you, and from. These words have two or three letter sounds students knew and only one or two letters that had to be memorized. We integrated 2 or 3 of these words into a phonics lessons, and students learned to identify the letters spelled as expected and to learn “by heart” the letters not spelled as expected.

With this approach, students had an easier time learning to read the word said because they knew that only the letters ai are an unexpected spelling. Students also soon stopped confusing was and saw because they learned to think about the first sound before reading or spelling those words. The teacher told us that she, her students, and their parents were thrilled that they were no longer “banging their heads against the wall” going over and over the words as students tried to memorize how to read or spell high-frequency words with little success.

Current practices

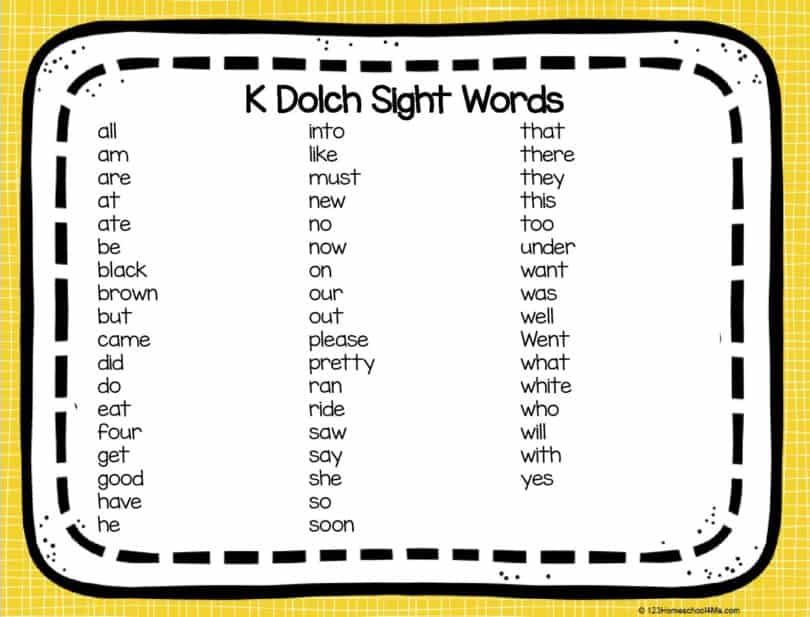

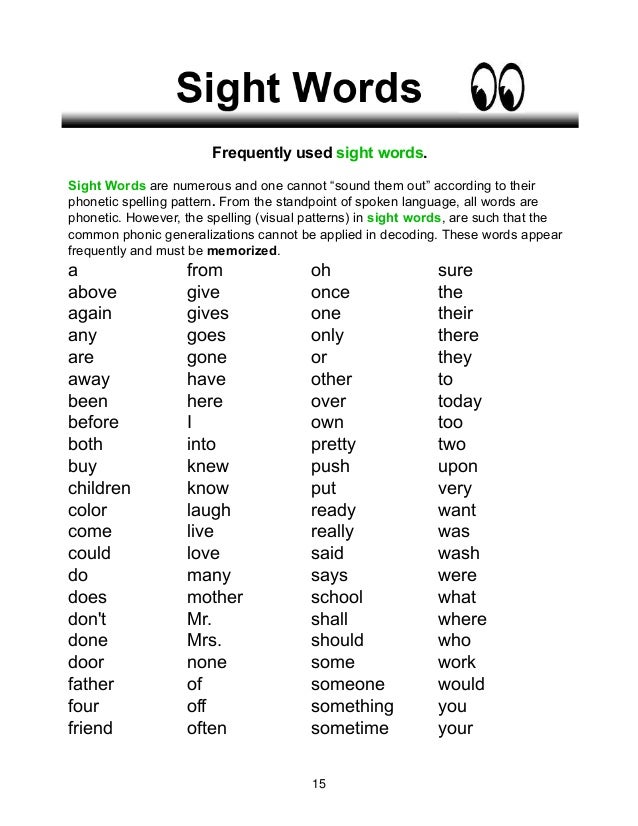

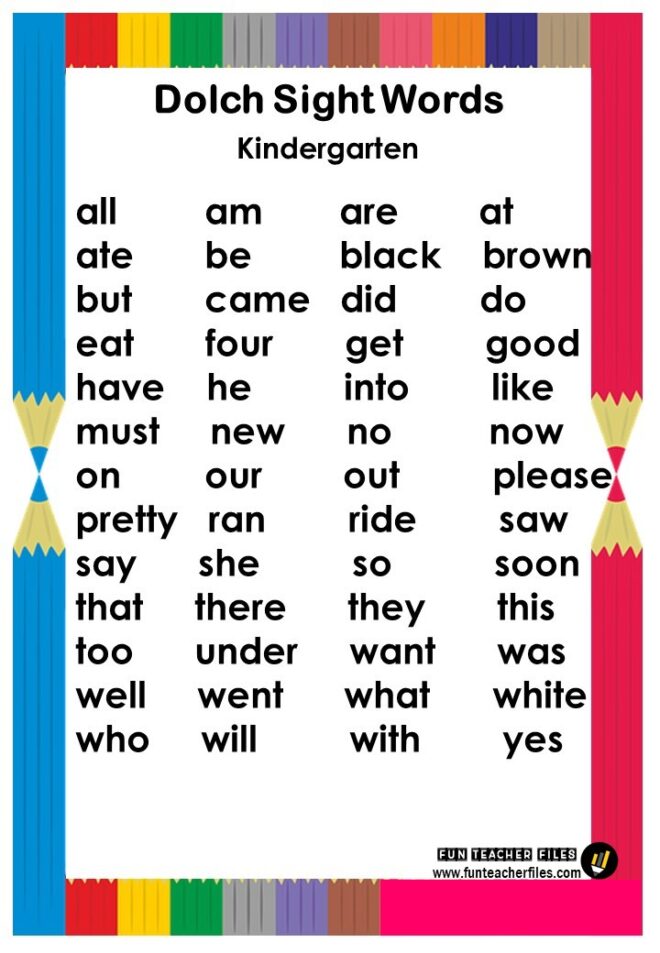

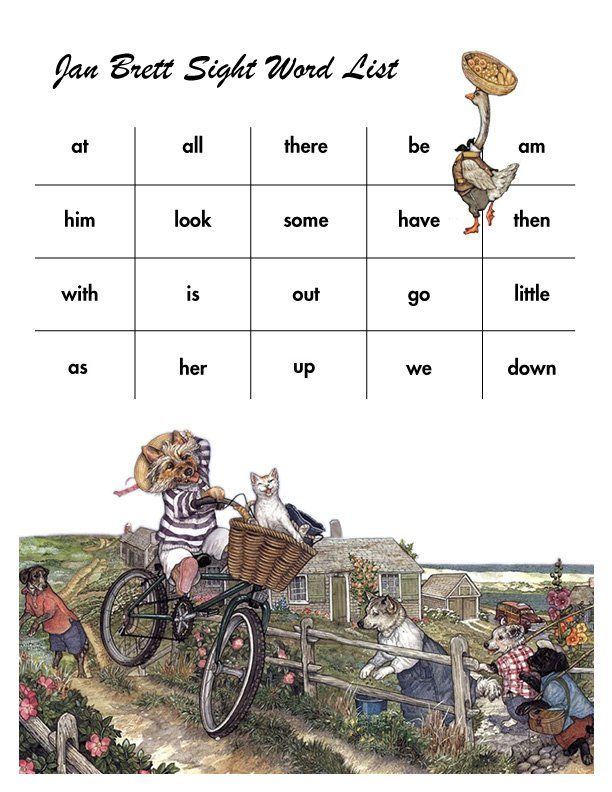

High-frequency words are often referred to as “sight words”, a term that usually reflects the practice of learning the words through memorization. These words might be on the Dolch List, Fry Instant Words, or selected from stories in the reading program. Common practice often includes sending these “sight words” home for students to study and memorize, or drilling with flash cards in school. Students may start with word #1 and progress through the words in the order of frequency. Some teachers, like our friend above, group the words in categories, such as numbers or colors, whenever possible. In essence, high-frequency word instruction is often fully divorced from phonics instruction. While this method works for many students, it is an abysmal failure with others.

These words might be on the Dolch List, Fry Instant Words, or selected from stories in the reading program. Common practice often includes sending these “sight words” home for students to study and memorize, or drilling with flash cards in school. Students may start with word #1 and progress through the words in the order of frequency. Some teachers, like our friend above, group the words in categories, such as numbers or colors, whenever possible. In essence, high-frequency word instruction is often fully divorced from phonics instruction. While this method works for many students, it is an abysmal failure with others.

Overview of suggested restructuring

Integrating high-frequency words into phonics lessons allows students to make sense of spelling patterns for these words. To do this, high-frequency words need to be categorized according to whether they are spelled entirely regularly or not. Restructuring the way high-frequency words are taught makes reading and spelling the words more accessible to all students. The rest of this article describes how to “rethink” teaching of high-frequency words and fit them into phonics lessons.

The rest of this article describes how to “rethink” teaching of high-frequency words and fit them into phonics lessons.

Teach 10–15 “sight words” before phonics instruction begins

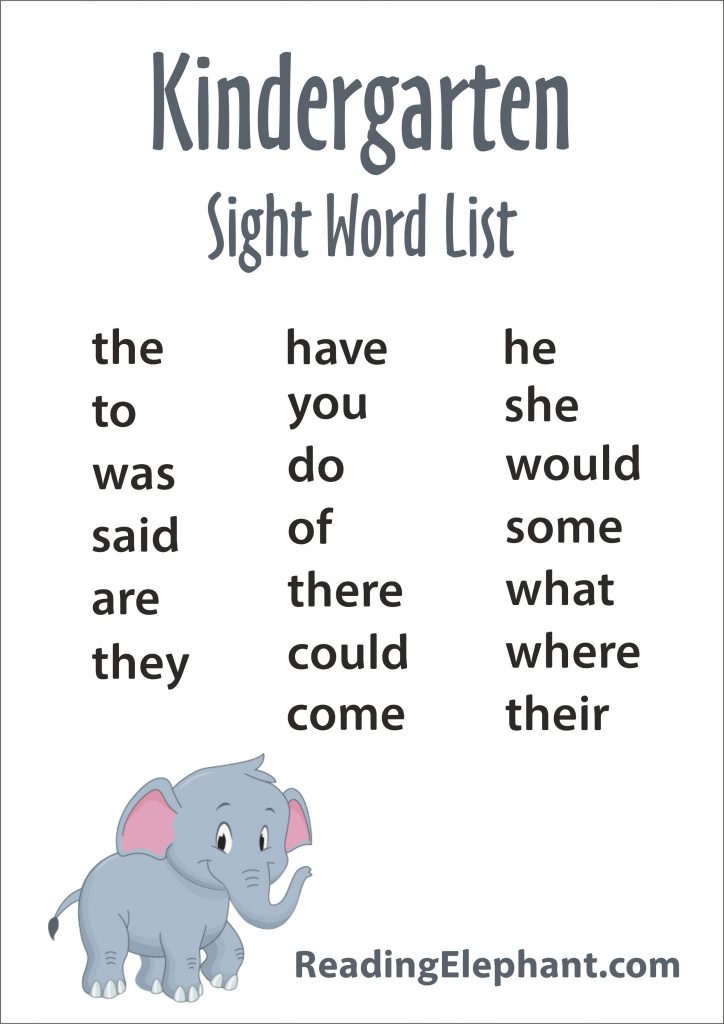

Many kindergarten students are expected to learn 20 to 50, or even more, high-frequency words during the year. The words are introduced and practiced in class and students are asked to study them at home. Learning these “sight words” often starts before formal phonics instruction begins.

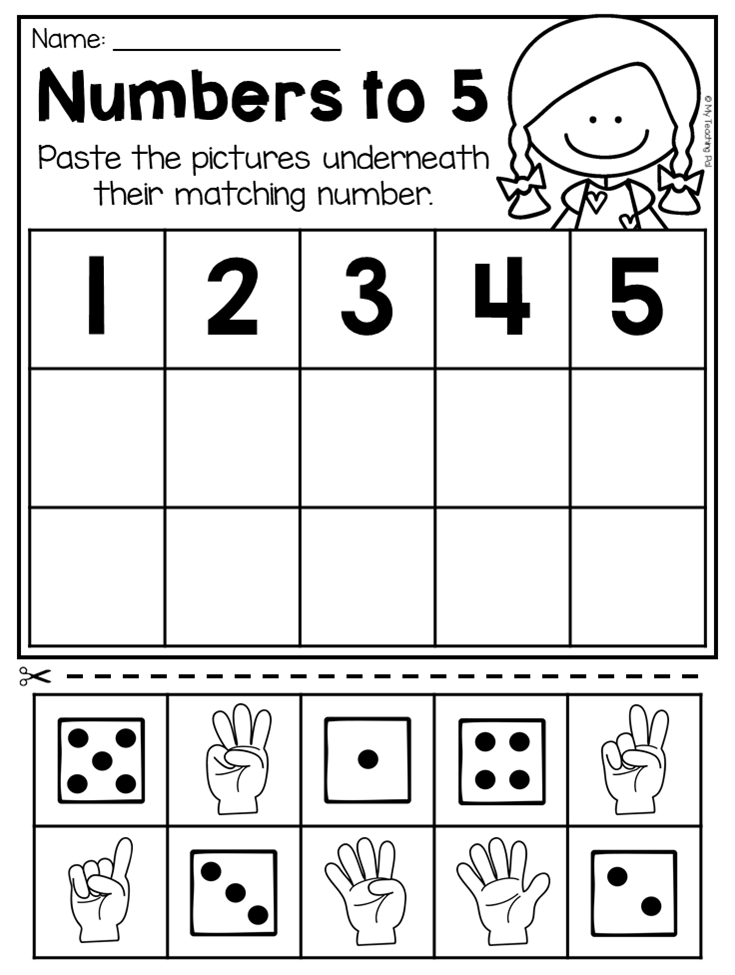

Children do need to know about 10–15 very-high-frequency words when they start phonics instruction. However, these words can be carefully selected so that they are the “essential words” that are not decodable when the short vowel patterns VC and CVC are taught. Words such as at, can, and had are easier for students to learn using phonics than by simply memorizing them.

We recommend teaching 10–15 pre‐reading high-frequency words only after students know all the letter names, but before they start phonics instruction. (Students who have not learned their letter names inevitable struggle to learn words that have letters they cannot identify.) Teaching students to read the ten words in Table 1 as “sight words” even before they begin phonics instruction is unlikely to overburden even “at risk” students. These ten words can be used to write decodable sentences when phonics instruction begins. The words in Table 1 are suggestions only, and teachers may revise or add words based on their reading materials and their students. For example, the words are and said are often added.

(Students who have not learned their letter names inevitable struggle to learn words that have letters they cannot identify.) Teaching students to read the ten words in Table 1 as “sight words” even before they begin phonics instruction is unlikely to overburden even “at risk” students. These ten words can be used to write decodable sentences when phonics instruction begins. The words in Table 1 are suggestions only, and teachers may revise or add words based on their reading materials and their students. For example, the words are and said are often added.

To teach these ten pre-reading sight words, we recommend introducing one word at a time. Teaching these words in the order listed can minimize confusion for students. For example, the and a are unlikely to be confused, as are I and to. However, to and of are widely separated on the table because both are two-letter words with the letter o, and t and f have similar formations.

As we recommended above, the words in Table 1 should not be taught or practiced until a student knows all the letter names.

Students can demonstrate they know these words in a number of ways, including (1) finding the word in a list or row of other words, (2) finding the word in a text, (3) reading the word from a card, and (4) spelling the word.

If students know letter sounds and can identify the first sound in a word, the following words can be tied to beginning letter sounds because the initial sound is spelled as expected: to, and, was, you, for, is. The word I is easily recognized by students who know their letter names. On the other hand, the words the, a, and of cannot be tied to known letter sounds.

Teaching a “ditty” to help students learn the, a, and of works for many students. Teachers have had success teaching students to sing the ditties below. It is important that students have the word in front of them when they say the ditty. They should point to the word when they say it in the ditty, and point to the letters when they say them in the ditty.

They should point to the word when they say it in the ditty, and point to the letters when they say them in the ditty.

- The: I can say ‘thee’ or I can say ‘thuh’, but I always spell it ‘t’ ‘h’ ‘e’

- A: I can say ‘ā’ or I can say ‘uh’, but I always spell it with the letter ‘a’

- Of is hard to spell, but not for me. I love to spell of. ‘o’ ‘f’ of, ‘o’ ‘f’ of, ‘o’ ‘f’ of

Table 1: 10 Sight Words for Pre-Readers to Learn

| Word | Dolch Frequency Rank | Fry Frequency Rank |

|---|---|---|

| the | 1 | 1 |

| a | 5 | 4 |

| I | 6 | 20 |

| to | 2 | 5 |

| and | 3 | 3 |

| was | 11 | 12 |

| for | 16 | 13 |

| you | 7 | 8 |

| is | 22 | 7 |

| of | 9 | 2 |

Dolch words are from: Dolch, E. W. (1936). A basic sight vocabulary. The Elementary School Journal, 36(6), 456-460.

W. (1936). A basic sight vocabulary. The Elementary School Journal, 36(6), 456-460.

Dolch Rankings were found on lists at K12 Reader and Mrs. Perkins Dolch Words.

Fry words and rankings are from: Fry, E., & Kress, J.K. (2006). The Reading Teacher’s Book of Lists. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco.

Flash Words and Heart Words defined

For instructional purposes, high-frequency words can be divided into two categories: those that are phonetically decodable and those with irregular spellings. We call high-frequency words that are regularly spelled and thus decodable “Flash Words”.

Although their spelling patterns are easily decoded, Flash Words are used so frequently in reading and writing that students need to be able to read and spell them “in a flash”. Examples of Flash Words at the cvc level are can, not, and did. Irregularly spelled words are called “Heart Words” because some part of the word will have to be “learned by heart.” Heart Words are also used so frequently that they need to be read and spelled automatically. Examples of Heart Words are: said, are, and where.

Examples of Heart Words are: said, are, and where.

Words on any high-frequency word list can easily be categorized into Flash Words and Heart Words. However, be cautioned that a word may change categories. For example, early in a phonics scope and sequence, see may be a Heart Word because the long e spelling patterns haven’t been taught. When students learn that ee spells long e, see becomes a Flash Word. Further, many of the Heart Words can be categorized into words with similar spellings. This article categorizes words on the Dolch List of 220 High Frequency Words (Dolch 220 List)1. The method we use to categorize words on the Dolch 220 List works with any high-frequency word list.

Flash Words

One hundred and thirty-eight words (63%) on the Dolch 220 List are decodable when all regular spelling patterns are considered. Tables 2A, 2B, and 2C show the 138 decodable words categorized by spelling patterns. These tables can help teachers determine when to introduce the words during phonics lessons. Table 2A may be most useful for teachers of beginning reading because it lists the 60 one-syllable decodable words with the short vowel spelling pattern.

These tables can help teachers determine when to introduce the words during phonics lessons. Table 2A may be most useful for teachers of beginning reading because it lists the 60 one-syllable decodable words with the short vowel spelling pattern.

Table 2A: Flash Words (Decodable Words)

60 One-Syllable Words with Short Vowel Spelling Patterns

(Numbers in parentheses are the Dolch frequency ranking)

| VC | CVC | Digraphs | Blends | Words Ending in NG and N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by digraph) | (Sorted by ending blends, then beginning blends) | (Sorted by ending letters) |

| at (21) | had (20) hot (203) | that (14) | and (3) | sing (213) |

| am (37) | can (42) but (19) | with (23) | just (78) | bring (155) |

| an (72) | ran (111) run (163) | then (38) | must (149) | long (167) |

| it (8) | him (22) cut (188) | them (52) | fast (182) | thank (216) |

| in (10) | did (45) get (51) | this (55) | best (210) | think (110) |

| if (65) | will* (59) yes (60) | much (142) | went (62) | drink (159) |

| on (17) | big (61) red (80) | pick (185) | ask (70) | |

| off* (132) | six (120) well* (109) | wish (217) | its (75) | |

| up (24) | sit (191) let (112) | when (44) | jump (98) | |

| us (169) | not (49) tell (141) | which (192) | help (113) | |

| got (93) ten (153) | stop (131) | |||

| black (151) |

*Students easily understand that two consonants at the end of a word spell one sound.

1The source for words on the Dolch 220 List is: Dolch, E. W. (1936). A basic sight vocabulary. The Elementary School Journal, 36(6), 456-460. Tables in this article show frequency rankings for words on the Dolch 220 list. Rankings for words on the Dolch 220 List can be found in many places, but we did not find a primary source that can be attributable to Dr. Dolch.

Rankings were retrieved on March 15, 2013, from K12 Reader and Mrs. Perkins Dolch Words.

Flash Words that can be taught with spellings students know will vary at any given time, depending on which phonics patterns students have been taught. For example, the words had, am, and can will be decodable when students have learned short a and vc and cvc spelling patterns. That, when, pick, and much will be decodable after students learn digraphs and can read words with digraphs. The words just, went, black, and ask will be decodable when students learn to read words with blends.

Flash Words should be introduced when they fit into the phonics pattern being taught, which is different from teaching them based on their frequency of use. Flash Words are different from other decodable words only because of their frequency. They are called Flash Words because students will need lots of practice to read and spell these words “in a Flash”. These are called “Flash Words” instead of “sight words” because students do not have to memorize any part of Flash Words. They can use their knowledge of phonics patterns to read and spell the words.

Flash Words are different from other decodable words only because of their frequency. They are called Flash Words because students will need lots of practice to read and spell these words “in a Flash”. These are called “Flash Words” instead of “sight words” because students do not have to memorize any part of Flash Words. They can use their knowledge of phonics patterns to read and spell the words.

Flash Words with advanced vowels to teach with early phonics instruction

Table 2B shows 60 one-syllable words with more advanced vowel spelling patterns. A few of these are so frequent that they will need to be taught when students are still learning the short vowel spelling patterns (VC and CVC) during phonics lessons.

Table 2B: Flash Words (Decodable Words)

60 One-Syllable Words With R‐Controlled, Long, and Other Vowel Spellings

(Numbers in parentheses are the Dolch Frequency Ranking)

| r-Controlled Vowels | CV Long Vowel | VCe (silent e) | Vowel Teams with Long Vowel Sounds | Vowel Teams with Other Vowel Sounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel sound, then vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel sound, then vowel spelling) |

| for* (16) | I* (6) | came (69) | play (127) | out* (31) |

| or* (123) | he* (4) | take (94) | may (130) | round (140) |

| start (150) | she* (15) | make (114) | say* (183) | found (200) |

| far (205) | be* (33) | made (162) | see* (48) | down* (40) |

| her* (28) | we* (36) | gave (164) | green (99) | now* (66) |

| first (146) | me* (58) | ate (177) | sleep (116) | how* (88) |

| hurt (186) | go* (35) | like (53) | keep (143) | brown (117) |

| so* (47) | ride (76) | three (170) | look (26) | |

| no* (68) | five (119) | eat (125) | good (82) | |

| my* (56) | white (152) | read (197) | new (148) | |

| by* (103) | clean (208) | soon (161) | ||

| fly (138) | right (90) | draw (207) | ||

| try* (147) | light (184) | saw* (106) | ||

| why (198) | own (199) | |||

| show (202) | ||||

| grow (209) |

* Many programs teach these words as Heart Words when students are still learning to read words with short vowels.

Traditionally, many words in Table 2B would be taught as “sight words” and not included as part of phonics lessons. These words might be introduced as they are encountered in a story, or they might be taught in order. For example, he would be taught as high-frequency word #4, then she taught as high-frequency word #12, with we (#26), be (#33), and me (#58), following later.

Under the new model, words with asterisks in Table 2B are still introduced when short vowels are being taught. The difference in the new model is that these words are grouped together by vowel spelling pattern to make it easier for students to remember the words. Instead of teaching he in isolation as a word to be memorized, we teach he, be, we, me, and she together (as shown in the CV column in Table 2b) and point out that the letter e spells the long e sound. Go, no, and so can be taught together, as can my, by, and why.

Students will learn words more easily when grouped together by similar spelling than by memorizing words one at a time as whole units. If the curriculum requires a Flash Word to be taught before the vowel pattern has been introduced, teachers can refer to Table 2B to find words that can be grouped together.

Flash Words with two and three syllables

Table 2C shows 16 Flash Words with two syllables and one Flash Word with three syllables. We recommend teaching these words after students have learned to read two‐syllable words in phonics instruction. If these words must be introduced earlier, students will learn them more easily if the teacher breaks the words into syllables and shows any known letter sounds in each syllable. This way students learn to read each syllable and blend the syllables into a word, instead of having to memorize the whole word.

Table 2C: Flash Words (Decodable Words)

17 Two-Syllable Words and 1 Three-Syllable Word

(Numbers in parentheses are the Dolch Frequency Ranking)

| CVC | "A" Spells Schwa in First Syllable | Short Vowels and r-Controlled Vowels | Short Vowel and Long Vowel | All Other Two-Syllable Words | Three-Syllable Word |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seven* (134) | about* (84) | after (108) | myself (139) | little (39) | every** (96) |

| upon (211) | around* (85) | never (133) | open* (165) | over (73) | |

| away* (101) | better (172) | funny (175) | going (115) | ||

| under (196) | yellow 118) | ||||

| before (124) |

* These words have a schwa sound in the first or second syllable.

** This word is often pronounced with two syllables, especially in conversation.

Heart Words

The Dolch 220 List has 82 Heart Words (37%) that are shown on Tables 3A and 3B. Heart Words have Heart Letters, which are the irregularly spelled part of the word. For example, o is the Heart Letter in the words to and do.

Some of the Dolch Heart Words with similar spelling patterns can be grouped together, even though the spelling patterns are not regular. Table 3A (on the next page) shows 45 Heart Words grouped according to similar spelling patterns. The table also lists twelve words not on the Dolch List. These twelve words have similar spelling patterns to the Dolch words listed, and the words are likely to be words already in young students’ vocabularies. For example, could and would are Dolch words. We recommend adding should when could and would are taught, even though it is not on the Dolch 220 List.

The groups of words in Table 3A can be added to any phonics or spelling lesson, with the Heart Letters pointed out. For example, the words his, is, as, and has can all be taught as vc and cvc words in which the letter s is the Heart Letter because it spells the sound /z/.

For example, the words his, is, as, and has can all be taught as vc and cvc words in which the letter s is the Heart Letter because it spells the sound /z/.

Table 3A: Heart Words

59 Words Grouped by Similar Spelling Patterns

45 Words from the Dolch List and 14 Not on the Dolch List

(Numbers in Parentheses Are the Dolch Frequency Ranking)

(Diamond [♦] indicates word is not on the Dolch List, but it fits the spelling pattern)

| Unusual Spelling Pattern | High-Frequency Words |

|---|---|

| s at the end of the word spells /z/ | his (13), is (27), as (32), has (166) |

| v is followed by e because no English word ends in v | have (34), give (144), live (206) |

| o-e spells short u /ŭ/ | some (30), come (64), done (180) |

| o spells /ōō/ (as in boot) | to (2), do (41), into (77) |

| rhyming words spelled with the same last four letters | there (29), where (95) |

| s spells /z/ in a vce word | those (179), these (212) |

| all spells /ŏll/ | all (25), call (167), fall (193), small (195), ball ♦ |

| oul spells /ŏŏ/ (as in cook) | could (43), would (57), should ♦ |

| e at the end is after a phonetic r-controlled spelling | were (50), are (63) |

| vcc and cvcc words with o spelling long o /ō/ | old (102), cold (136), hold (173), both (190) |

| cvcc words with i spelling long i /ī/ | find (167), kind (189), mind ♦ |

| words similar in meaning and spelling | one (54), once (160) |

| a after w sometimes spells short o /ŏ/ | want (86), wash (201), watch ♦ |

| ue spells /ōō/ as in boot | blue (79), glue ♦, clue ♦, true ♦ |

| u spells /ŏŏ/ (as in cook) | put (91), full (178), pull (187), push ♦ |

| rhyming words with silent l | walk (121), talk ♦ |

| rhyming words - the letter a spells short i or short e (depending on dialect) | any (83), many (218) |

| oo at the end of a word spells /ōō/ (as in boot) | too (92), boo ♦, moo ♦ |

| or spells /er/ | work (145), word ♦, world ♦ |

| uy spells long i /ī/ | buy (174), guy ♦ |

Teaching Heart Words

Table 3B shows 37 Heart Words not easily grouped by spelling patterns. Most of the words are more difficult for spelling than for reading.

Most of the words are more difficult for spelling than for reading.

As with all Heart Words, these words can also be incorporated into phonics instruction when students learn to read the regularly spelled letters a word. For example, when students know the digraph th, they and their can be introduced. The digraph th in both these Heart Words is a regular spelling for the sound /th/. The Heart Letters are ey in they and eir in their. Similarly, the Heart Letter in the word what is a, and the Heart Letter in the word from is o.

Table 3B: Heart Words

37 Words that Do Not Fit into Spelling Patterns

(Numbers in parentheses are the Dolch Frequency Ranking)

| the (1) | very (71) | here (105) | does (154) | use (181) |

| a (5) | yours (74) | two (122) | goes (156) | carry (194) |

| of (9) | from (81) | again (126) | write (157) | because (204) |

| you (7) | don’t (87) | who (128) | always (158) | together (214) |

| was (11) | know (89) | been (129) | only (168) | please (215) |

| said (12) | pretty (97) | eight (135) | our (171) | shall (219) |

| they (18) | four (100) | today (137) | warm (176) | laugh (220) |

| what (46) | their (104) |

Students enjoy drawing a heart above Heart Letters, and the hearts help them remember the irregular spellings.

For example, in the word said, the hearts would go above ai because those letters are an unexpected spelling for short e (/ĕ/). A student’s practice card for the word said is shown at the right.

Implementing the new model

In order to implement the new phonics-based model for teaching high-frequency words, teachers will need to fit high-frequency words into phonics instruction. To do this, generally a committee of three or four kindergarten and first grade teachers organizes their lists of high-frequency words according to Heart Words and Flash Words by spelling patterns. Next they determine when and how high-frequency words fit into the phonics scope and sequence. These same teachers provide professional development to show other teachers how to implement the new model.

Sometimes a coordinated effort to change the way high-frequency words are taught is not an option, and teachers are able to only partially implement the suggestions in this article. These teachers continue to introduce the words as determined by their curriculum. However, they tell students whether the “sight word” is a Flash Word or a Heart Word, and they introduce the words by teaching letter–sound relationships as outlined in this article. Further, teachers introduce words with similar spelling patterns whenever possible. For example, if only the word would is scheduled to be introduced, they also teach could and should, which fit the spelling pattern. Finally, these teachers do not hold students accountable for high-frequency words that are beyond the spelling patterns that have been taught in phonics lessons.

These teachers continue to introduce the words as determined by their curriculum. However, they tell students whether the “sight word” is a Flash Word or a Heart Word, and they introduce the words by teaching letter–sound relationships as outlined in this article. Further, teachers introduce words with similar spelling patterns whenever possible. For example, if only the word would is scheduled to be introduced, they also teach could and should, which fit the spelling pattern. Finally, these teachers do not hold students accountable for high-frequency words that are beyond the spelling patterns that have been taught in phonics lessons.

The new model allows a different approach for working with students who have difficulty learning high-frequency words. For example, students working on short vowel patterns may confuse her and here, which are often introduced early as part of the “sight word” list. A teacher who recognizes the source of this confusion would not expect students to continue trying to memorize the two words. Instead, the teacher would include her as part of instruction on r-controlled vowels and include here when silent e is taught. Students will be less likely to misread or misspell these words when they understand the relation of the spelling er to the sound /er/ and the spelling ere to the sound /ēr/.

Instead, the teacher would include her as part of instruction on r-controlled vowels and include here when silent e is taught. Students will be less likely to misread or misspell these words when they understand the relation of the spelling er to the sound /er/ and the spelling ere to the sound /ēr/.

Traditionally, students would have continued struggling with and failing to memorize these easily confused words. With the new model, those students are not held accountable for accurately reading and spelling the words until they can understand and use the sound–spelling correspondences. All teachers using this approach say that students learn to spell and read the words much more easily than with the traditional approach.

About the authors

Linda Farrell and Michael Hunter are founding partners of Readsters, LLC. They provide professional development and write curriculum to support excellent reading instruction to students of all ages. Their favorite work is in the classroom where they can model effective reading instruction and coach teachers. Their most unusual work so far has been helping develop early reading instruction for children in Africa who are learning to read in 12 different mother tongue languages that Linda and Michael don’t even speak.

Their favorite work is in the classroom where they can model effective reading instruction and coach teachers. Their most unusual work so far has been helping develop early reading instruction for children in Africa who are learning to read in 12 different mother tongue languages that Linda and Michael don’t even speak.

Tina Osenga was a founding partner at Readsters, and she is now retired.

How to determine the perfect and imperfect form of the verb?

Let's learn how to write without errors and make interesting stories

Start learning

194.1K

Harry Potter's girlfriend used the time-wheel to be in two places at the same time. Different types of verbs will help to describe the actions of Miss Granger. There are only two of them: perfect and imperfect. Let's talk about them in more detail.

Basic Definitions

First, let's remember what a verb is.

The verb is a part of speech that designates an action or state as a process and expresses this meaning using the categories of aspect, voice, mood, tense and person.

Verbs answer questions: what to do? what to do? what have you been doing? What did you do? what do they do? what will do?

Examples of verbs:

The form in Russian is a constant grammatical feature of verbs, which is possessed by conjugated verbs, infinitives, gerunds and participles. It shows how some action of the verb proceeds in time:

-

completed and one-time (read, passed)

-

unfinished and repeatable (lives, does).

What types of verbs are there in Russian:

Now we will learn what a perfect and imperfect form of a verb is and give examples of perfect and imperfect verbs.

Demo lesson in Russian

Take the test at the introductory lesson and find out what topics separate you from the "five" in Russian.

Perfective verbs

Perfective verbs in indefinite form answer the question: what to do?

Perfective verbs have two tense forms:

In any tense form they call:

-

an action that is limited by some limit;

-

result, completion of an action or a separate stage.

Examples of perfective verbs:

-

what did you do? sat down - past tense, the action is completed and was done once, that is, it was not repeated;

-

what will they do? they will talk - the future simple tense, the action will be done and will not be repeated.

-

what to do? close, pay, perform;

-

what to do? identify, answer, simplify.

Perfective verbs can also denote actions that have already begun or are about to begin: I spoke, I will speak.

Imperfect verbs

Imperfect verbs in the indefinite form answer the question: what to do?

Imperfective verbs have three tenses:

They denote:

In any tense, they denote a repeated or ongoing action, without indicating whether the action has been completed.

Examples of imperfective verbs:

-

what did you do? jumped - past tense, the action could be repeated several times and it is not known whether the result was achieved;

-

what are they doing? they are watching - the present tense, the action continues and it is not known how long the action has been going on and how long it will continue;

-

what shall I do? I will dance - the future is a difficult time, the action can be repeated and there are no signs that it will be completed.

-

what to do? talk, paint, run;

-

what to do? drag, go.

Imperfective verbs can also denote actions that have begun, are beginning or will begin: I looked, I look, I will light.

Now we know what questions are answered by perfective and imperfective verbs. And here is a cheat sheet to fix and learn the difference of two types:

Free English lessons with a native speaker

Practice 15 minutes a day. Learn English grammar and vocabulary. Make language a part of life.

Formation of verb types

Perfective verbs can be formed from imperfective verbs in different ways.

Ways of education:

-

Adding a prefix: read - read, sit - sit up.

-

Dropping suffixes: give - give, save - save.

-

Replacement of suffixes: decide - decide, jump - jump.

-

Replacement of suffixes and alternation of letters in the root: forgive - forgive, wither - wither.

When forming imperfective verbs, the alternation of consonants and vowels is possible at the root: be late - be late, state - state, protect - protect.

Learn Russian at the Skysmart online school with attentive teachers and interesting examples from modern texts.

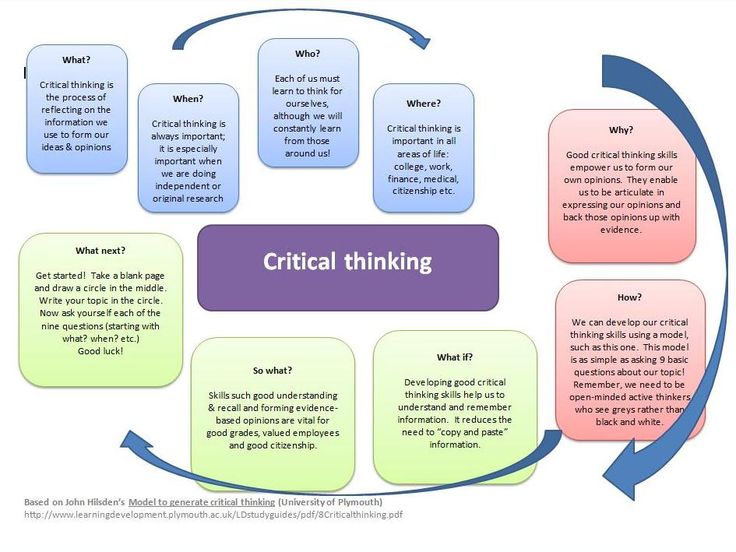

Determine the form of the verb

If you are in doubt how to understand what kind of verb you have: perfect or imperfect, use these methods:

| How to determine the aspect of a verb |

|---|

|

Now you can easily tell your classmates how to determine the form of a verb in Russian.

Examples of pairs of perfective and imperfective verbs

Aspective pair are verbs that have a perfective and imperfective form.

Some Russian verbs have the same lexical meaning, but differ in the grammatical meaning of the form. For example: what to do? decide what to do? decide.

Such aspectual pairs differ in the way of word formation:

-

Through the suffix: quit - throw, meet - meet, offend - offend, reach - achieve, decide - decide.

-

Through the prefix: cook - cook, call - name, work - process, speak - talk, read - finish reading.

The aspectual pairs of verbs may differ:

-

Emphasized.

fall asleep - fall asleep, cut - cut.

-

Roots.

what to do? catch - what to do? to catch;

put - put;

to invest - to invest;

to take - to take;

search - find.

The aspect of the verb may depend on the context of the sentence. For example:

-

She is now (what is she doing?) sleeping with a friend. — Present tense, imperfective form.

-

Tomorrow (what will she do?) she is staying with a friend. — Future tense, perfect form.

Such verbs are called two-part verbs, they include: telegraph, take possession, spend the night, injure, marry, execute, promise, use, attack and others. Two aspect verbs can denote both a complete action and an action in length.

Table of perfect and imperfect verbs

| | imperfective | Perfect look |

|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | What to do? play | What to do? play |

| Past tense | What did you do? played | What did you do? played |

| Present | What am I doing? playing | - |

| Future tense | What will I do? will play | What will I do? play |

Russian cheat sheets for parents

All the rules for the Russian language at hand

Mother tongue day: will the words “zoom”, “covidivory” and other borrowings from the era of coronavirus remain with us |

AS: Can we say that the Russian language has changed a lot under the influence of the pandemic?

MC: No, I don't think so. The language itself has not changed much. There were some new words, a lot of jokes and memes. But our way of life, communication, way of communication has changed a lot. This is probably even more important than changing the language.

Due to self-isolation, we have started using zoom more. As a result, a very special kind of communication has appeared - this is communication on the screen. For example, during a conference, meeting or lecture, a large number of people can be on the screen at the same time. But at the same time, each of them is in its own private space.

AS: How many new words have appeared in the Russian language since the beginning of the pandemic?

MC: We cannot say that there are many, but, naturally, new words have appeared that are associated with the disease and the social situation. For some words, the combinability jumped sharply. These are, for example, words such as “quarantine” or “isolation”. Words such as “lockdown” appeared, the names of diseases and viruses – “coronavirus”, “covid” and so on.

A huge number of label words have also appeared that we do not use in speech, but use them as jokes or memes. There are a lot of them, but they are quickly becoming obsolete. This, for example, is such a word as "mascophobia". We see that in different periods of the pandemic, different words were the most important. For example, over the past six months or a year, the vaccine has been in the spotlight and the word “anti-vaxur” has become widely used.

And, although there are a lot of jokes and memes, this is still not a replenishment of our vocabulary. It's just a joke at the moment. At some time, balcony singing appeared as a reaction to the fact that somewhere in Italy people began to go out onto balconies and sing arias, entertaining each other.

So the vocabulary has not changed much, but speech behavior, which is more dependent on communication, has certainly changed. For example, it became unclear where we are looking during an online conversation: at ourselves, at another, at a dot on the screen, or even reading something else or turning off the camera and doing something else during the meeting.

AS: Is it possible to say that the words that have entered the Russian language over the past two years are mostly anglicisms?

MK: If we are talking about jokes, then in different ways. There are also anglicisms. Let's say covidiots. This is a fusion of "covid" and "idiots" - someone who either follows the rules too much or doesn't follow the rules at all. That is, extremes.

Or “covidivors”, a combination of the words “covid” and “divors” (from the English Divorce - divorce, ed. note). That is, covid-related divorces. These are borrowings. But there are others. I gave an example of "mascophobia", and there are hundreds of such words. Recently, a large dictionary of the era of the coronavirus has even appeared.

If we are talking about a small circle of important words, then these are indeed mostly borrowings, and more recently. “Covid”, “coronavirus”, “saturation” (although this term existed before). But there are, as I mentioned, the words “quarantine” and “isolation”, which were borrowed a long time ago and have already become Russian words. Also, a number of terms have become common, simply because they are needed to describe diseases.

Also, a number of terms have become common, simply because they are needed to describe diseases.

I also remembered the word "zoom". Interestingly, you can “zoom” not only with the help of zoom. This is the new type of communication I was talking about. It is so important that a new word was needed for it. And the name of this platform was borrowed.

AS: Why are these words not translated into Russian and can they be replaced by some Russian-language synonyms if there is such an indication from above?

MK: Recently, the Russian language as a whole has begun to turn less to translation. By "Russian" I mean all of us native speakers. We are more willing to borrow words. Maybe because of laziness, maybe because of the fashion of foreign words, or for some other reason. But we began to borrow words more easily than in the 20th century, especially than in Soviet times.

It's hard to say how to translate, say, the word "coronavirus". Here everything is a component of the “virus” - this is a long-standing borrowing, which should no longer be considered as such. And the “crown” came to us from outside, after it first struck most of the world and received its stable name.

Here everything is a component of the “virus” - this is a long-standing borrowing, which should no longer be considered as such. And the “crown” came to us from outside, after it first struck most of the world and received its stable name.

It seems to me that such internationalism, based on world English now, is convenient for international communication. We say “coronavirus” and understand each other, at least in terms of the topic of conversation.

And, let's say, such borrowing as “lockdown”, on the one hand, is quite frequent. On the other hand, it competes with such words as "quarantine" and "isolation". The meanings of these words overlap at least partially. I can't say that it has firmly entered the Russian language, it needs to be studied carefully.

But, in my opinion, the usual word "quarantine", an old borrowing, which is no longer considered as such, is more convenient in this case. The word "lockdown" rather gives a social assessment of the situation, while "quarantine" is more individual.

AS: So, it can be said that the borrowing of English words in recent times, especially in the era of the pandemic, is typical for all languages, not only for Russian?

MK: Of course. It's just convenient. Not necessary, but convenient. Doctors especially. When such a global phenomenon is called in different languages in a similar way.

AS: You said that in Soviet times there were fewer such borrowings. Was it due to the greater isolation of the country?

MK: Yes, of course, in Soviet times there were many borrowings immediately after the revolution. And in this sense, perestroika and revolution produced similar effects and consequences. Because it broke through the borders.

Although there is a difference. Today it is entirely Anglicisms, with a few exceptions. And post-revolutionary borrowings are those very internationalisms. Because after all, the ideology behind these borrowings was a world revolution.

Today's anglicisms are also completely understandable and obvious, just based on the role of the English language in the modern world.

AS: How do you think these new words and concepts that appeared along with the pandemic will take root and stay in the Russian language?

MK: First, we need to divide these words into groups. If we talk about words-labels, words-jokes and words-memes, then, of course, they will not linger. They didn't linger anymore. Those words that appeared in the first wave are almost forgotten. Words associated with illness, with social phenomena, and partly with communications, rather took root. This is, for example, the word "zoom" in colloquial language.

When the pandemic passes or ceases to play such a role as it does today, I think that all these words will lose their frequency and again go into a narrowly professional sphere. It seems to me that this is a natural thing. But, as I said, there is a chance that words like “zoom” and “zoom” will remain, because this phenomenon must survive the pandemic. Clearly, this way of communicating will take a much larger place in our communication than before the pandemic. We won't give up on amenities. For two years, society has become accustomed to this method of communication, and in some types of communication it is much more convenient.

Clearly, this way of communicating will take a much larger place in our communication than before the pandemic. We won't give up on amenities. For two years, society has become accustomed to this method of communication, and in some types of communication it is much more convenient.

Seems like a completely natural thing to me. When the phenomenon is superimportant, then the words that existed in the language become frequent. And when the phenomenon disappears, or at least becomes not so important, then the words "go to the bottom."

In this case, they will either simply lose their frequency, like the word "quarantine" and "vaccines", or go into the professional sphere. For example, the name of the disease is “covid”. If covid is not among us, then we will not need a word. But for doctors, it will remain relevant, at least for describing this historical cuisine.

AS: And Russian-language synonyms for the word “covid” will not appear over time?

MK: I don't think so. This is an abbreviation for the words corona, virus and disease - a disease. No, it's not relevant. It is much more interesting to look at the distribution of two words - “coronavirus” and “covid”. Because, if we approach these concepts pedantically, then coronavirus is the name of a virus, and covid is the name of the disease caused by this virus. But, of course, in ordinary language these distinctions are not respected. Both words refer to both the virus and the disease. But if in the first wave the word “coronavirus” was popular, then later, as it seems to me, “covid” pushed out “coronavirus”.

This is an abbreviation for the words corona, virus and disease - a disease. No, it's not relevant. It is much more interesting to look at the distribution of two words - “coronavirus” and “covid”. Because, if we approach these concepts pedantically, then coronavirus is the name of a virus, and covid is the name of the disease caused by this virus. But, of course, in ordinary language these distinctions are not respected. Both words refer to both the virus and the disease. But if in the first wave the word “coronavirus” was popular, then later, as it seems to me, “covid” pushed out “coronavirus”.

And yet, now this disease is called covid. This word began to be written in Cyrillic Russian letters. For a long time it was written, and still sometimes found, in Latin. But I do not think that any Russian variants appear. There was such a typically Russian abbreviation: they began to say simply “corona” from “coronavirus”. Because this is an important language mechanism: if a word is very important, then it is often abbreviated.

AS: Can we say that the changes associated with the emergence of new vocabulary amid the pandemic are the main changes in the Russian language over the past couple of years?

MK: In a couple of years - rather, yes. But if we take a slightly longer period, three, five or ten years, then I noticed an active entry into the general space of psychotherapeutic vocabulary. A lot of new words have appeared - “abuse”, various types of “shaming”. Some Russian words have expanded their meaning - "borders", "injuries" and so on.

Changes related to political correctness are very important. They began to appear 10-15 years ago, and they are growing. There are also very important phenomena associated with social processes, with new ideologies, with ideologies that came to Russia belatedly from outside. Changes in such areas are taking place, it’s just that the pandemic dealt a strong blow to us and to the language, which fit in a very short time.

AS: You mentioned the trend towards political correctness and the introduction of new psychotherapeutic concepts. According to your estimates, will the Russian language develop in the same directions in the coming years, or are new trends already emerging?

MK: These guidelines will remain. After all, we are talking about trends caused by some external events. I am not ready to predict what new social movements will appear in the world. But we see that now in a number of foreign countries political correctness in the field of transgender issues is becoming very important. And, of course, this direction will also be served by the language. Of course, something new will appear, but I am not ready to predict what exactly, because changes always come from the outside, and the language simply reflects these trends.

Therefore, first of all, the already mentioned trends will develop. New vocabulary related to youth cultures will appear, especially in the field of music, where the percentage of borrowings is very high.