What is alphabetic principle

The Alphabetic Principle | Reading Rockets

Not knowing letter names is related to children's difficulty in learning letter sounds and in recognizing words. Children cannot understand and apply the alphabetic principle (understanding that there are systematic and predictable relationships between written letters and spoken sounds) until they can recognize and name a number of letters.

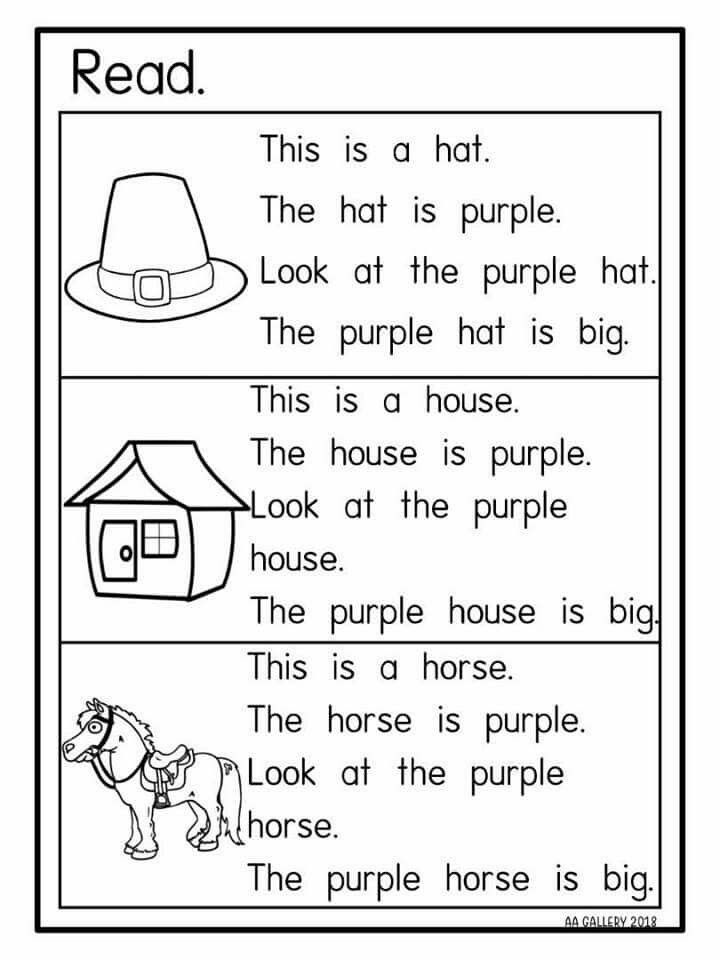

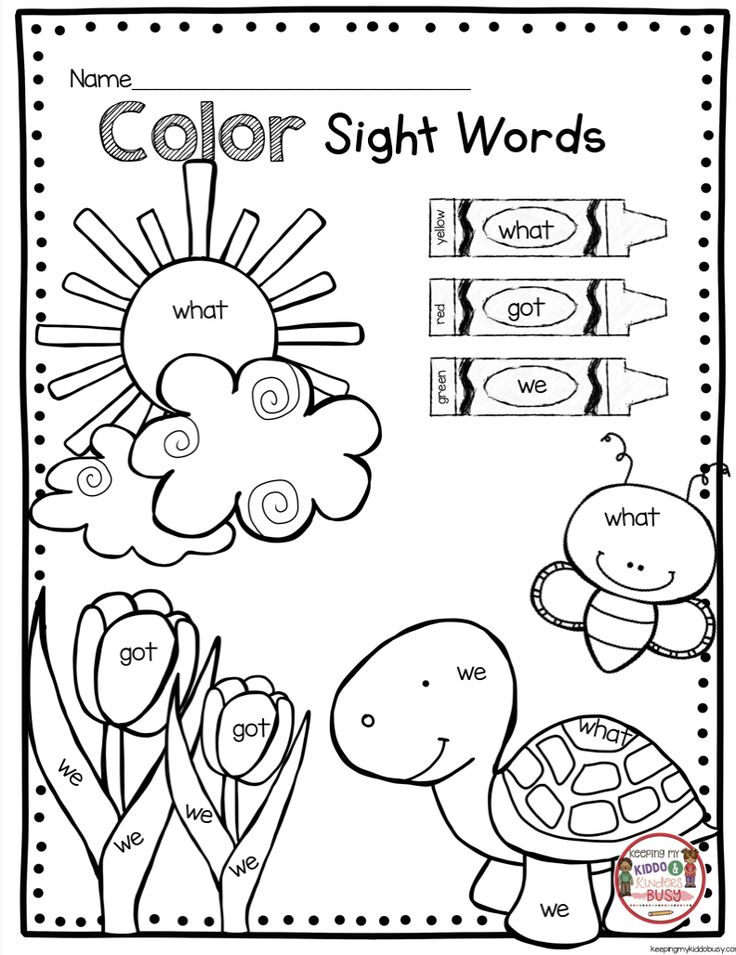

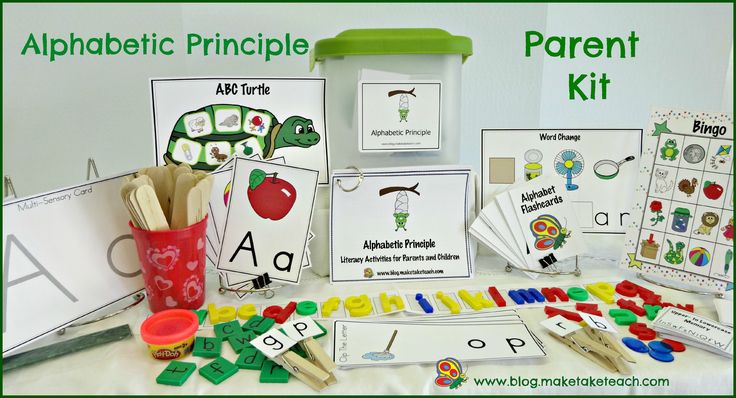

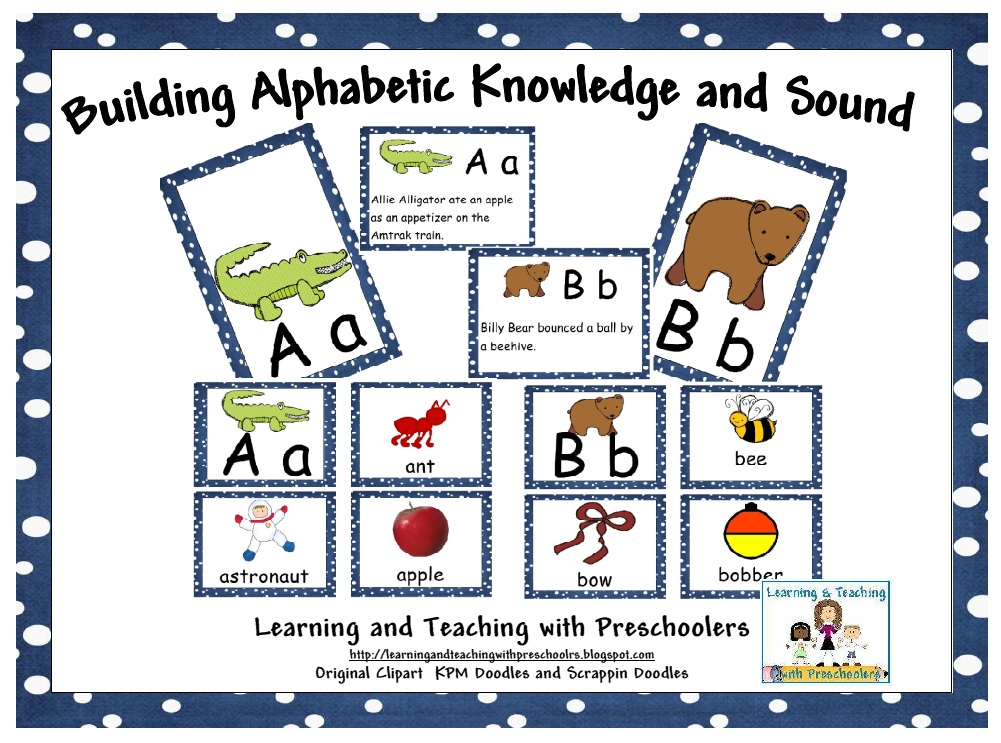

Children whose alphabetic knowledge is not well developed when they start school need sensibly organized instruction that will help them identify, name, and write letters. Once children are able to identify and name letters with ease, they can begin to learn letter sounds and spellings.

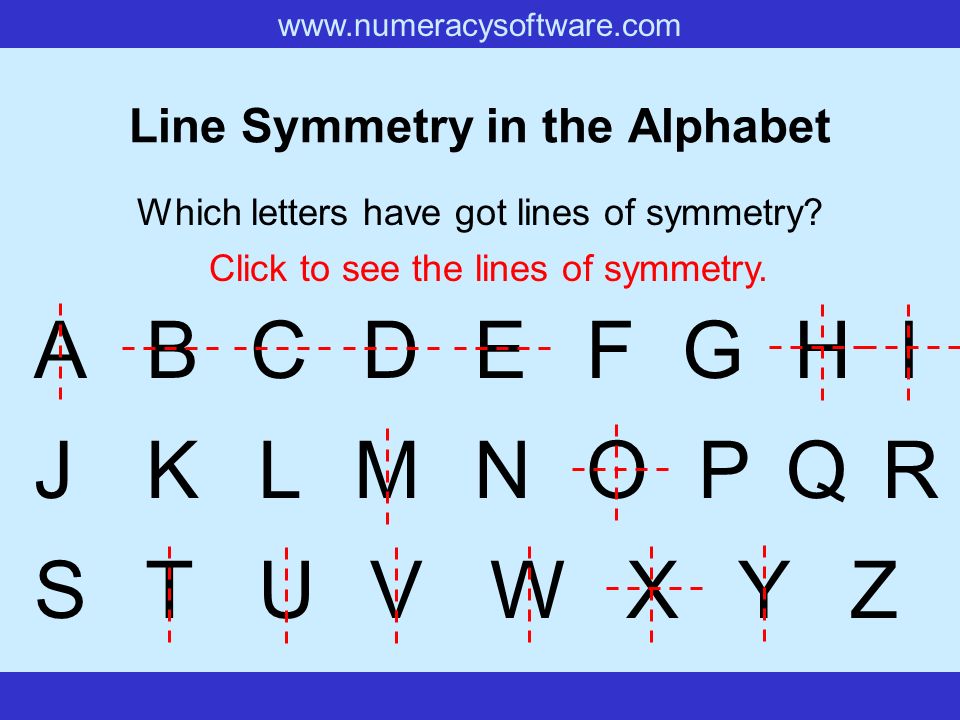

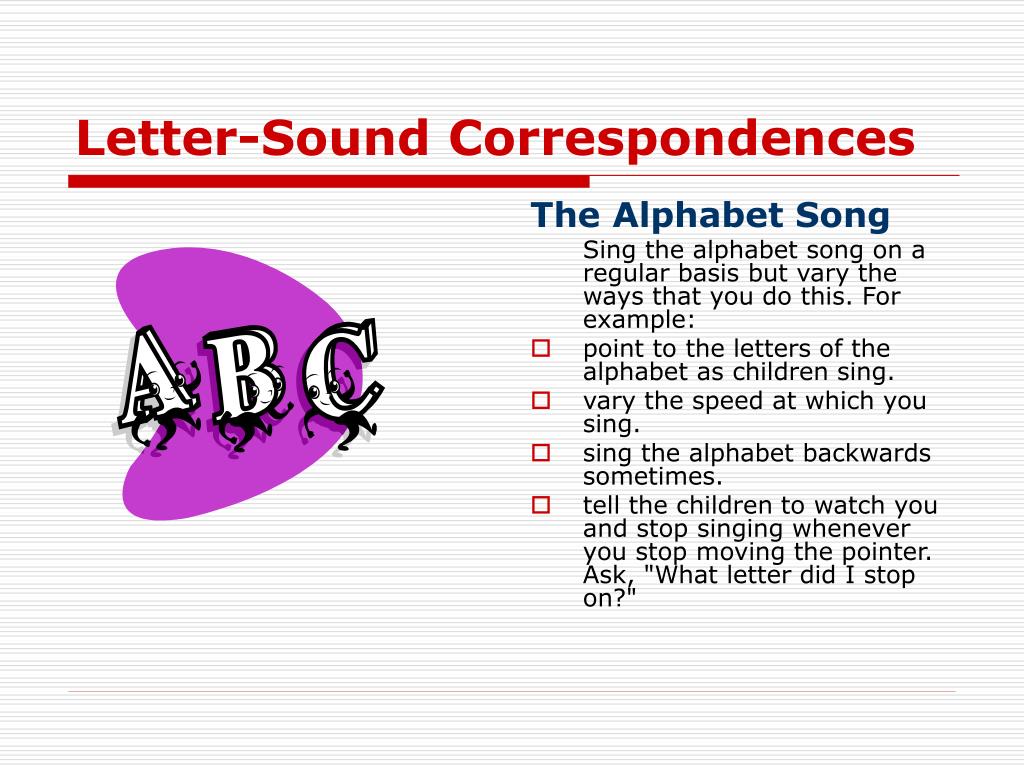

Children appear to acquire alphabetic knowledge in a sequence that begins with letter names, then letter shapes, and finally letter sounds. Children learn letter names by singing songs such as the "Alphabet Song," and by reciting rhymes. They learn letter shapes as they play with blocks, plastic letters, and alphabetic books.

Informal but planned instruction in which children have many opportunities to see, play with, and compare letters leads to efficient letter learning. This instruction should include activities in which children learn to identify, name, and write both upper case and lower case versions of each letter.

What is the "alphabetic principle"?

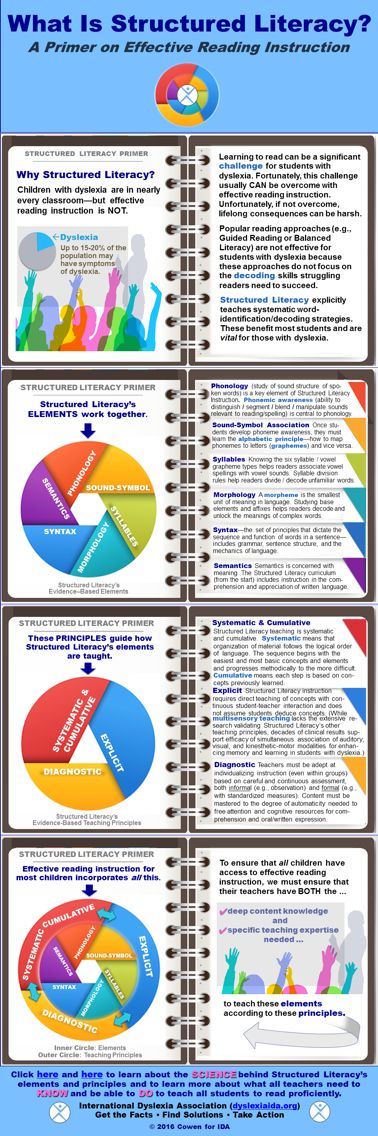

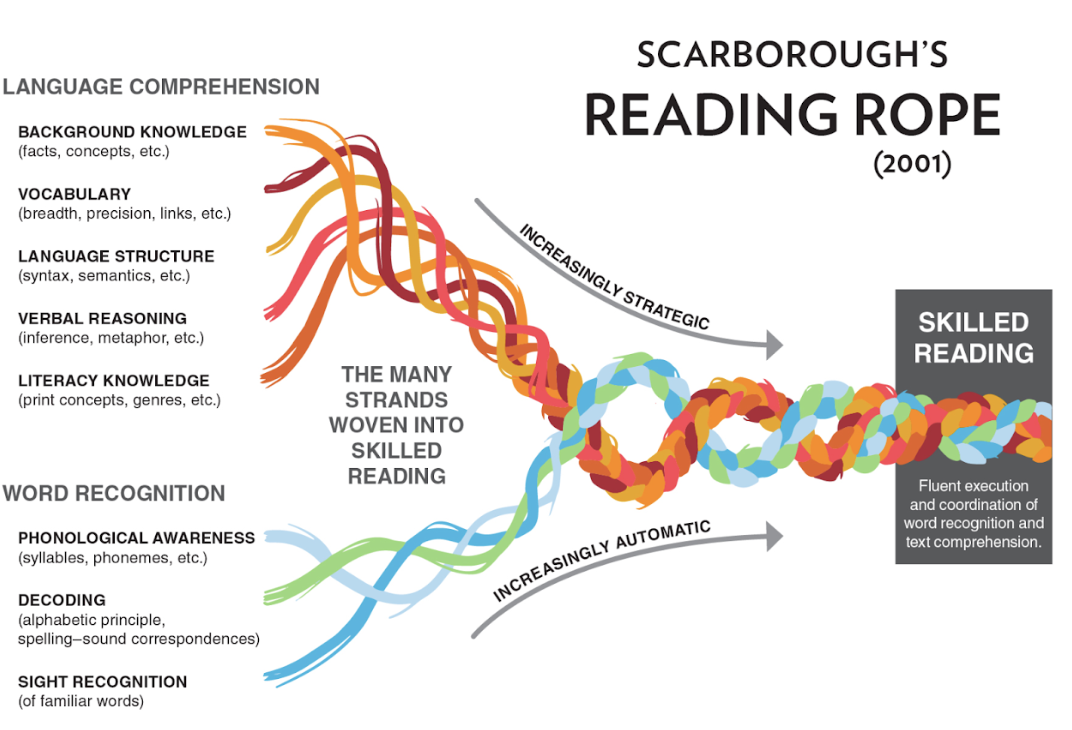

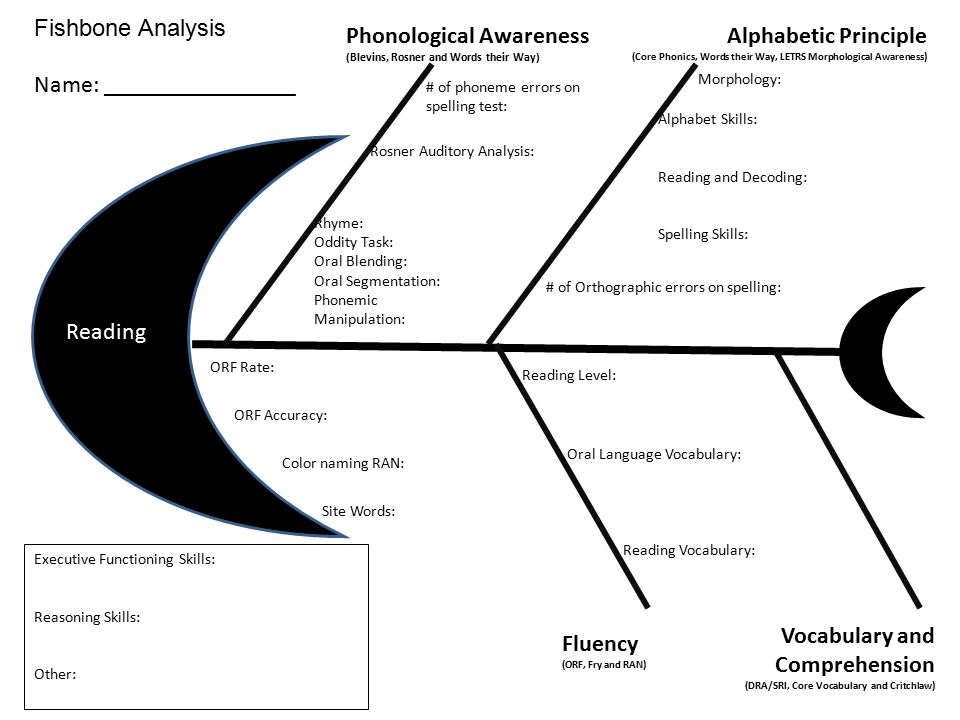

Children's reading development is dependent on their understanding of the alphabetic principle – the idea that letters and letter patterns represent the sounds of spoken language. Learning that there are predictable relationships between sounds and letters allows children to apply these relationships to both familiar and unfamiliar words, and to begin to read with fluency.

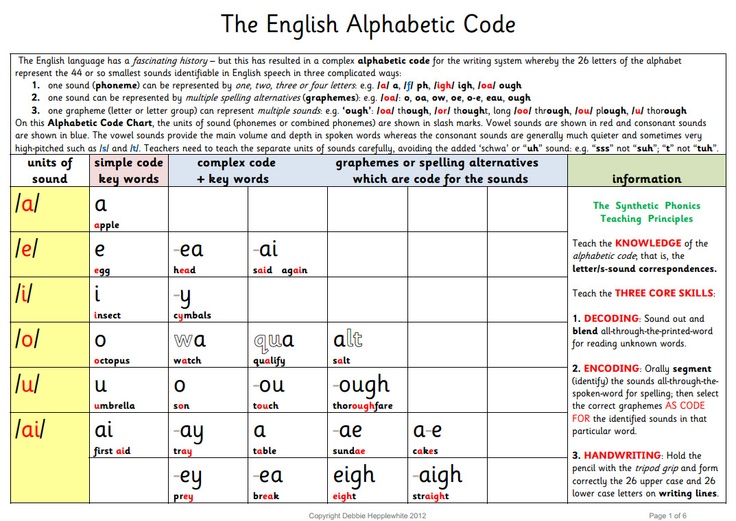

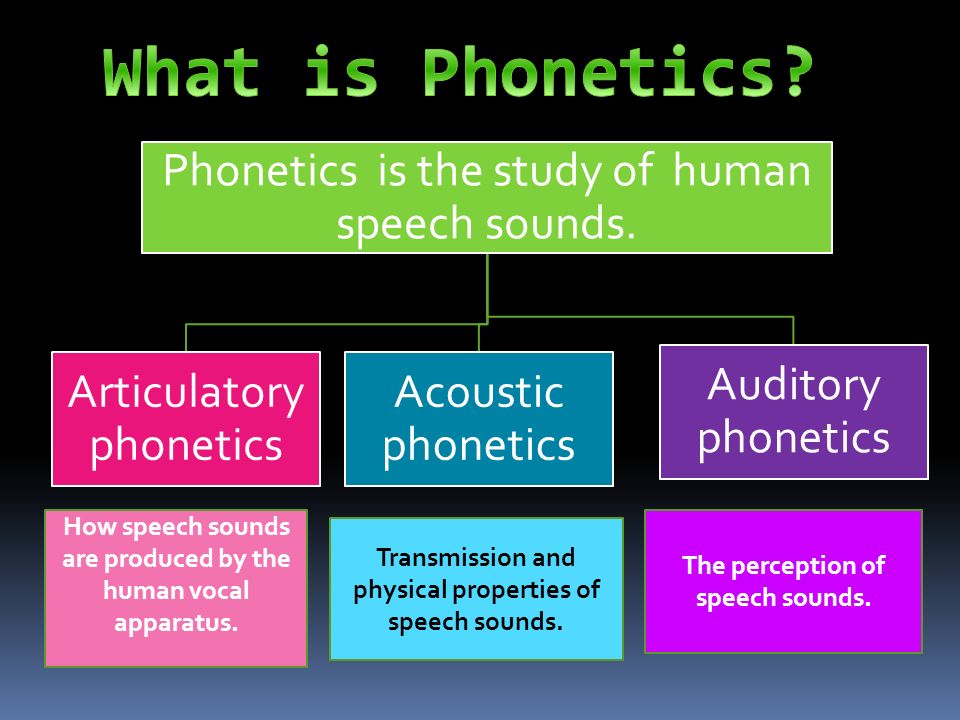

The goal of phonics instruction is to help children to learn and be able to use the Alphabetic Principle. The alphabetic principle is the understanding that there are systematic and predictable relationships between written letters and spoken sounds. Phonics instruction helps children learn the relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language.

Two issues of importance in instruction in the alphabetic principle are the plan of instruction and the rate of instruction.

The alphabetic principle plan of instruction

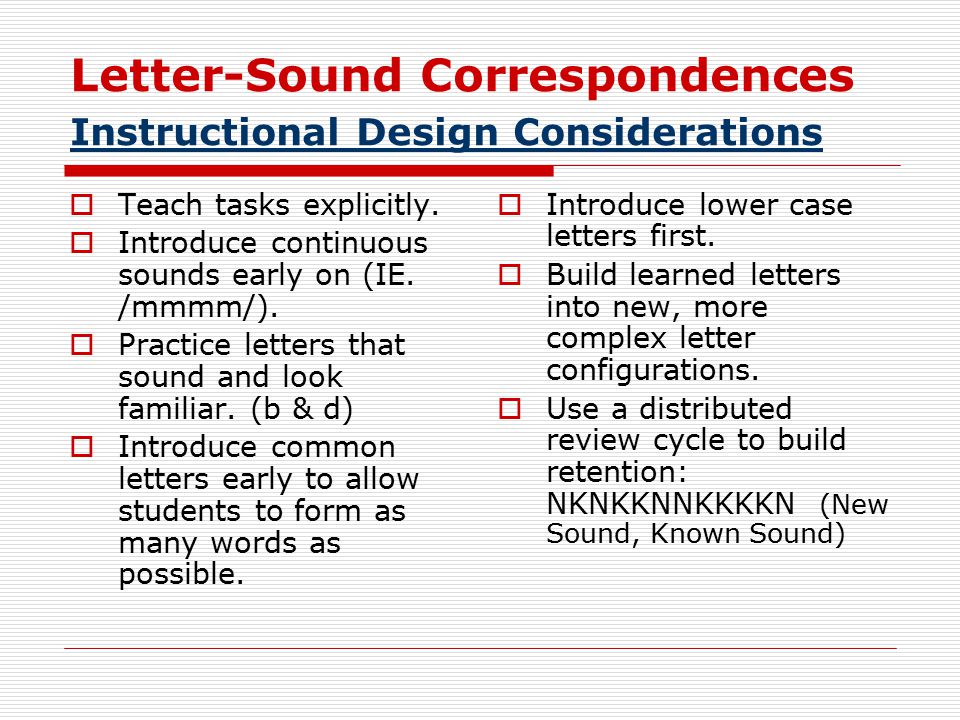

- Teach letter-sound relationships explicitly and in isolation.

- Provide opportunities for children to practice letter-sound relationships in daily lessons.

- Provide practice opportunities that include new sound-letter relationships, as well as cumulatively reviewing previously taught relationships.

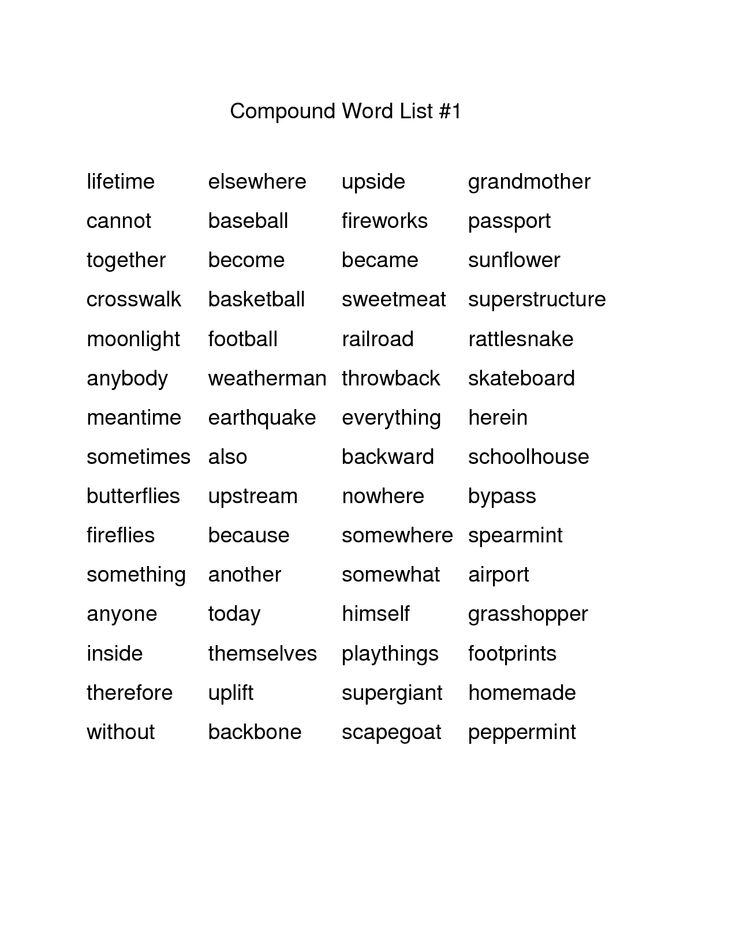

- Give children opportunities early and often to apply their expanding knowledge of sound-letter relationships to the reading of phonetically spelled words that are familiar in meaning.

Rate and sequence of instruction

No set rule governs how fast or how slow to introduce letter-sound relationships. One obvious and important factor to consider in determining the rate of introduction is the performance of the group of students with whom the instruction is to be used. Furthermore, there is no agreed upon order in which to introduce the letter-sound relationships. It is generally agreed, however, that the earliest relationships introduced should be those that enable children to begin reading words as soon as possible. That is, the relationships chosen should have high utility. For example, the spellings m, a, t, s, p, and h are high utility, but the spellings x as in box, gh, as in through, ey as in they, and a as in want are of lower utility.

Furthermore, there is no agreed upon order in which to introduce the letter-sound relationships. It is generally agreed, however, that the earliest relationships introduced should be those that enable children to begin reading words as soon as possible. That is, the relationships chosen should have high utility. For example, the spellings m, a, t, s, p, and h are high utility, but the spellings x as in box, gh, as in through, ey as in they, and a as in want are of lower utility.

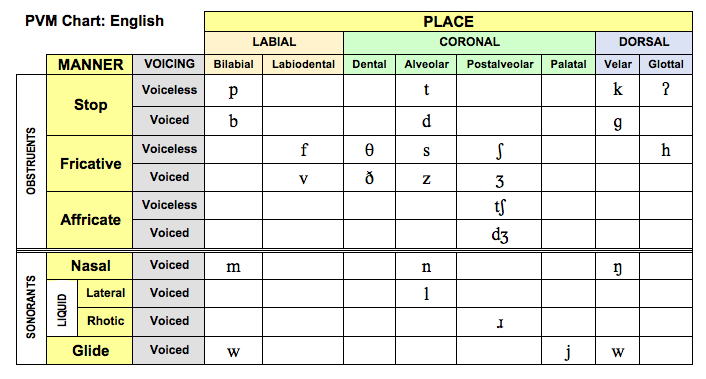

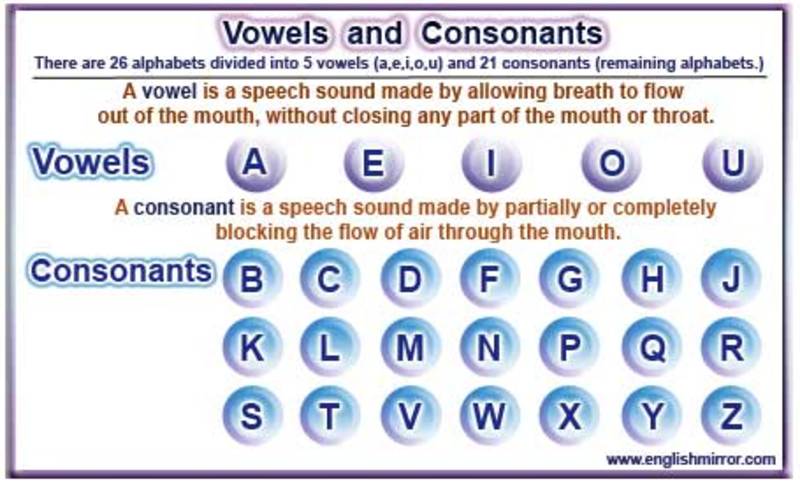

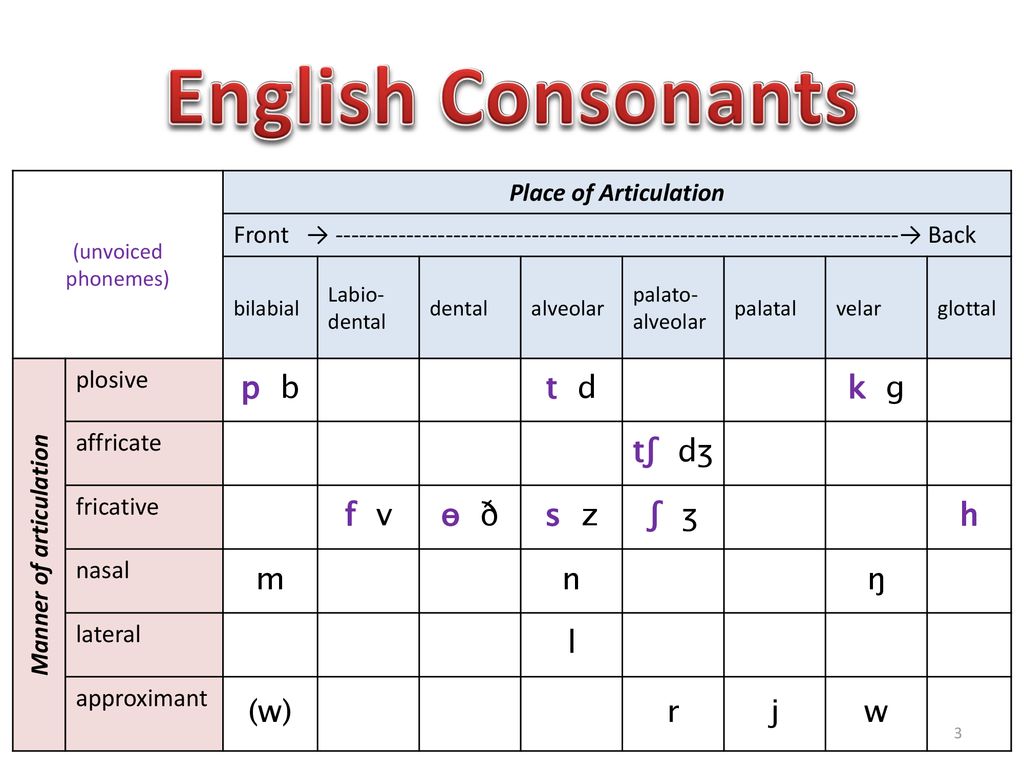

It is also a good idea to begin instruction in sound-letter relationships by choosing consonants such as f, m, n, r, and s, whose sounds can be pronounced in isolation with the least distortion. Stop sounds at the beginning or middle of words are harder for children to blend than are continuous sounds.

Instruction should also separate the introduction of sounds for letters that are auditorily confusing, such as /b/ and /v/ or /i/ and /e/, or visually confusing, such as b and d or p and g.

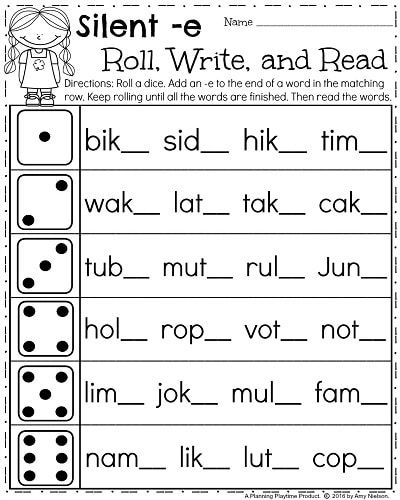

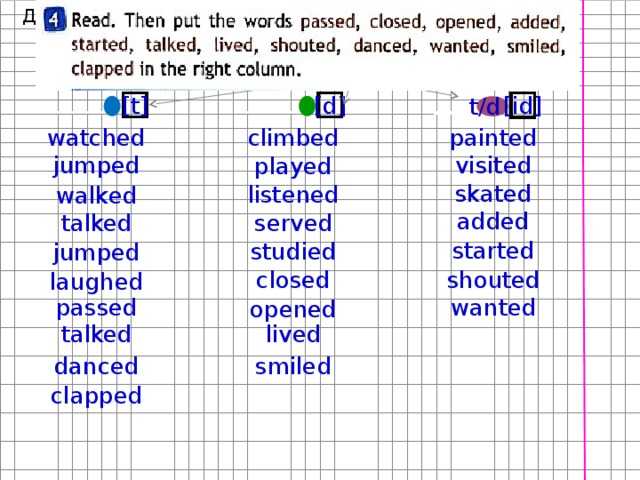

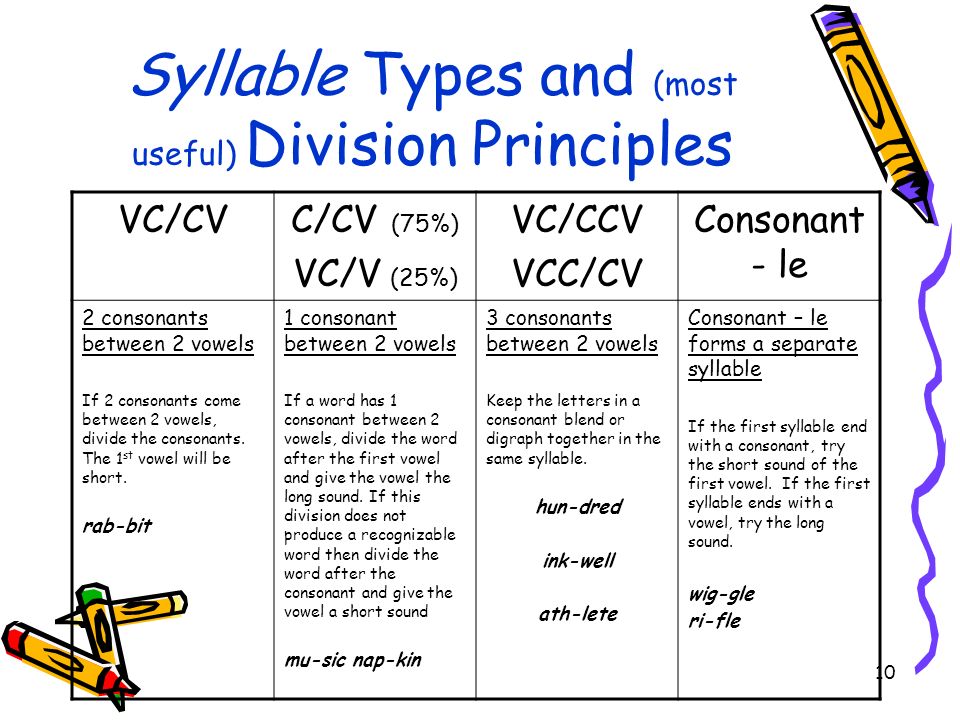

Instruction might start by introducing two or more single consonants and one or two short vowel sounds. It can then add more single consonants and more short vowel sounds, with perhaps one long vowel sound. It might next add consonant blends, followed by digraphs (for example, th, sh, ch), which permits children to read common words such as this, she, and chair. Introducing single consonants and consonant blends or clusters should be introduced in separate lessons to avoid confusion.

The point is that the order of introduction should be logical and consistent with the rate at which children can learn. Furthermore, the sound-letter relationships chosen for early introduction should permit children to work with words as soon as possible.

Many teachers use a combination of instructional methods rather than just one. Research suggests that explicit, teacher-directed instruction is more effective in teaching the alphabetic principle than is less-explicit and less-direct instruction.

Guidelines for rate and sequence of instruction

- Recognize that children learn sound-letter relationships at different rates.

- Introduce sound-letter relationships at a reasonable pace, in a range from two to four letter-sound relationships a week.

- Teach high-utility letter-sound relationships early.

- Introduce consonants and vowels in a sequence that permits the children to read words quickly.

- Avoid the simultaneous introduction of auditorily or visually similar sounds and letters.

- Introduce single consonant sounds and consonant blends/clusters in separate lessons.

- Provide blending instruction with words that contain the letter-sound relationships that children have learned.

Alphabetic Principle | Reading Rockets

Children's knowledge of letter names and shapes is a strong predictor of their success in learning to read. Knowing letter names is strongly related to children's ability to remember the forms of written words and their ability to treat words as sequences of letters.

Children whose alphabetic knowledge is not well developed when they start school need sensibly organized instruction that will help them identify, name, and write letters. Once children are able to identify and name letters with ease, they can begin to learn letter sounds and spellings.

Children appear to acquire alphabetic knowledge in a sequence that begins with letter names, then letter shapes, and finally letter sounds. Children learn letter names by singing songs such as the "Alphabet Song," and by reciting rhymes. They learn letter shapes as they play with blocks, plastic letters, and alphabetic books. Informal but planned instruction in which children have many opportunities to see, play with, and compare letters leads to efficient letter learning. This instruction should include activities in which children learn to identify, name, and write both upper case and lower case versions of each letter.

What is the "alphabetic principle"?

Children's reading development is dependent on their understanding of the alphabetic principle — the idea that letters and letter patterns represent the sounds of spoken language. Learning that there are predictable relationships between sounds and letters allows children to apply these relationships to both familiar and unfamiliar words, and to begin to read with fluency.

Learning that there are predictable relationships between sounds and letters allows children to apply these relationships to both familiar and unfamiliar words, and to begin to read with fluency.

The goal of phonics instruction is to help children to learn and be able to use the Alphabetic Principle. The alphabetic principle is the understanding that there are systematic and predictable relationships between written letters and spoken sounds. Phonics instruction helps children learn the relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language.

The alphabetic principle plan of instruction

The literacy program:

- Teaches letter-sound relationships explicitly and in isolation.

- Provides opportunities for children to practice letter-sound relationships in daily lessons.

- Provides practice opportunities that include new sound-letter relationships, as well as cumulatively reviewing previously taught relationships.

- Gives children opportunities early and often to apply their expanding knowledge of sound-letter relationships to the reading of phonetically spelled words that are familiar in meaning.

Rate and sequence of introduction

No set rule governs how fast or how slow to introduce letter-sound relationships. One obvious and important factor to consider in determining the rate of introduction is the performance of the group of students with whom the instruction is to be used. Furthermore, there is no agreed upon order in which to introduce the letter-sound relationships. It is generally agreed, however, that the earliest relationships introduced should be those that enable children to begin reading words as soon as possible. That is, the relationships chosen should have high utility. For example, the spellings m, a, t, s, p, and h are high utility, but the spellings x as in box, gh, as in through, ey as in they, and a as in want are of lower utility.

It is also a good idea to begin instruction in sound-letter relationships by choosing consonants such as f, m, n, r, and s, whose sounds can be pronounced in isolation with the least distortion. Stop sounds at the beginning or middle of words are harder for children to blend than are continuous sounds.

Stop sounds at the beginning or middle of words are harder for children to blend than are continuous sounds.

Instruction should also separate the introduction of sounds for letters that are auditorally confusing, such as /b/ and /v/ or /i/ and /e/, or visually confusing, such as b and d or p and g. Instruction might start by introducing two or more single consonants and one or two short vowel sounds. It can then add more single consonants and more short vowel sounds, with perhaps one long vowel sound. It might next add consonant blends, followed by digraphs (for example, th, sh, ch), which permits children to read common words such as this, she, and chair. Introducing single consonants and consonant blends or clusters should be introduced in separate lessons to avoid confusion.

The point is that the order of introduction should be logical and consistent with the rate at which children can learn. Furthermore, the sound-letter relationships chosen for early introduction should permit children to work with words as soon as possible. Many teachers use a combination of instructional methods rather than just one. Research suggests that explicit, teacher-directed instruction is more effective in teaching the alphabetic principle than is less-explicit and less-direct instruction.

Furthermore, the sound-letter relationships chosen for early introduction should permit children to work with words as soon as possible. Many teachers use a combination of instructional methods rather than just one. Research suggests that explicit, teacher-directed instruction is more effective in teaching the alphabetic principle than is less-explicit and less-direct instruction.

Guidelines for rate and sequence of introduction

The literacy program:

- Recognizes that children learn sound-letter relationships at different rates.

- Introduces sound-letter relationships at a reasonable pace, in a range from two to four letter-sound relationships a week.

- Teaches high-utility letter-sound relationships early.

- Introduces consonants and vowels in a sequence that permits the children to read words quickly.

- Avoids the simultaneous introduction of auditorially or visually similar sounds and letters.

- Introduces single consonant sounds and consonant blends/clusters in separate lessons.

- Provides blending instruction with words that contain the letter-sound relation.

Video: The Alphabetic Principle

In Houston, the teacher of an advanced kindergarten class connects letters and sounds in a systematic and explicit way.

ALPHABET • Great Russian Encyclopedia

Authors: Vyach. Sun. Ivanov

ALPHABET [Greek ἀλφάβητος, from the name of the first two letters of the Greek. A. - ἄλφα "alpha" and βῆτα "beta" (New Greek "vita")], a system of written signs that convey the sound image of the words of the language through symbols depicting individual sound elements. A.'s invention made it possible to record texts without referring to their meaning (unlike writing systems using ideograms and logograms), which made it possible to record, store and transmit a wide variety of texts in any languages, contributed to the spread of literacy and other achievements of Europe. civilization. All known alphabets are characterized by the presence of rules for designating phonemes in words and by a set of signs known to all who use them in a strictly defined sequence. The principle of ordering according to A. plays an important role in all modern. means of storing and searching for information (in dictionaries, other reference books, catalogs, etc.). nine0003

civilization. All known alphabets are characterized by the presence of rules for designating phonemes in words and by a set of signs known to all who use them in a strictly defined sequence. The principle of ordering according to A. plays an important role in all modern. means of storing and searching for information (in dictionaries, other reference books, catalogs, etc.). nine0003

The A. principle was invented by the West Semitic peoples (see West Semitic Letter ). All R. 3rd millennium BC e. Western Semitic (ancient Canaanite) scribes in the city of Ebla (modern Tel Mardikh, Northern Syria) created such a classification of cuneiform syllables borrowed from Mesopotamia, which they used to record the local Eblaite language. and the Mesopotamian Sumerian language, in which the signs were ordered according to the nature of the vowels with the same consonants: ma, mi, mu (in the Semitic languages there were only 3 vowels - a, i, u). Apparently, thanks to the use of the experience of cuneiform and Egyptian writing, app. Semites not later than the 1st half. 2nd millennium BC e. created such an initial type of consonant-syllabic writing, where there were signs for conveying consonants (for example, w) in combination with any vowel (syllables like wa, wi, wu, written not with different signs, as in cuneiform, but with one). Once in the set of all letters. signs were included and signs for vowels, A. finally took shape as an ordered set of letters. phoneme designations. nine0003

Semites not later than the 1st half. 2nd millennium BC e. created such an initial type of consonant-syllabic writing, where there were signs for conveying consonants (for example, w) in combination with any vowel (syllables like wa, wi, wu, written not with different signs, as in cuneiform, but with one). Once in the set of all letters. signs were included and signs for vowels, A. finally took shape as an ordered set of letters. phoneme designations. nine0003

Ancient alphabets.

The most ancient was A. of the city-state of Ugarit, known from the middle. 2nd millennium BC e. (see Ugarit letter). The order of characters in it in the main. corresponds to the order of signs in other West-Semitic alphabets, known since the last centuries of the 2nd millennium BC. e .: in Phoenician (see Phoenician letter), other Hebrew and some others.

Approximately at the turn of the 2nd-1st millennium BC. e. (perhaps a little earlier) the Phoenician A. of 22 letters was borrowed by the Greeks (see Greek letter), who significantly transformed it, turning it into other Greek. A. into a complete system. The correspondence between the letters A. and phonemes became one-to-one: all A. signs were used to record the phonemes to which they corresponded, and each phoneme corresponded to a certain letter A. The Etruscan A., closely related to other Greek (possibly brought by the Etruscans to Italy) has the same features. , where they moved at the end of the 2nd millennium BC by sea from Asia Minor) and the Asia Minor alphabets in Asia Minor of ancient times that have common features with it. The chronology of the creation and development of all a. turn of the 2nd-1st millennium BC. e. remains debatable. Later Greek. A. serves as a model for creating means. a number of other systems: Latin and other ancient Italic (those that experienced Etruscan influence), Armenian, Georgian, Gothic, Old Church Slavonic, and other alphabetic systems, where the order, names, and form of signs correspond exactly or with certain changes to Greek. The further spread of alphabetic language to record new languages was carried out on the basis of already created alphabetic characters, primarily Latin alphabetic (see Latin writing), Cyrillic, and others.

A. into a complete system. The correspondence between the letters A. and phonemes became one-to-one: all A. signs were used to record the phonemes to which they corresponded, and each phoneme corresponded to a certain letter A. The Etruscan A., closely related to other Greek (possibly brought by the Etruscans to Italy) has the same features. , where they moved at the end of the 2nd millennium BC by sea from Asia Minor) and the Asia Minor alphabets in Asia Minor of ancient times that have common features with it. The chronology of the creation and development of all a. turn of the 2nd-1st millennium BC. e. remains debatable. Later Greek. A. serves as a model for creating means. a number of other systems: Latin and other ancient Italic (those that experienced Etruscan influence), Armenian, Georgian, Gothic, Old Church Slavonic, and other alphabetic systems, where the order, names, and form of signs correspond exactly or with certain changes to Greek. The further spread of alphabetic language to record new languages was carried out on the basis of already created alphabetic characters, primarily Latin alphabetic (see Latin writing), Cyrillic, and others. In the 1st millennium BC. e. South Arabian A., which are an early offshoot of the Western Semitic systems, are attested. nine0003

In the 1st millennium BC. e. South Arabian A., which are an early offshoot of the Western Semitic systems, are attested. nine0003

In all known alphabetic systems, each letter has its own name. Names of letters in are stored in relatives. systems and when borrowing from one system to another (from Western Semitic to Greek). Names of letters in plural Western-Semitic traditions, except for Ugaritic (obviously, for the convenience of memorization and learning), were formed from words denoting objects that begin with the corresponding phonemes (“alef” 'bull', 'bet' 'house', etc.) . nine0003

The signs of the oldest known A., in particular Ugaritic, were not used to designate numbers. Later, in Western-Semitic A. of the 1st millennium BC. e. and in Greek A. the first letter in order [e.g., Greek. α (alpha)] can be a sign for the first whole number of the natural series after zero (i.e. α meant the number 1), the second - for the second (β meant the number 2), etc. This principle was preserved in the plural. systems based on the Greek. models, in particular in Old Slavonic and other Russian. When the shape of a letter changes, its ordinal place in alphabet and its numerical value are most often preserved, so for studying the history of alphabet, methods of designating numbers are of great importance. nine0003

systems based on the Greek. models, in particular in Old Slavonic and other Russian. When the shape of a letter changes, its ordinal place in alphabet and its numerical value are most often preserved, so for studying the history of alphabet, methods of designating numbers are of great importance. nine0003

Most modern nat. writing systems are based on A.: Latin, Slavic-Cyrillic (for example, Russian alphabet ), Arabic (see Arabic letter ), ind. syllabic (see Indian letter).

Alphabet of dispute and alphabet of reconciliation - News of Uzbekistan - Gazeta.uz

A draft law on amending the Uzbek alphabet in the Latin script has been published for discussion. It is proposed to replace the letter combinations and letters with an inverted apostrophe in the alphabet with letters with diacritical marks. Columnist Komil Jalilov examines how the alphabet has changed over the past century, how it has affected the development of the language and society, and tries to figure out how justified the new changes are.

Background of the issue

The 20th century was full of changes in terms of Uzbek writing. In the early 1920s, changes were made to the Arabic script, which had been used for ten centuries to record texts in the Uzbek language. These changes concerned the removal of letters from the alphabet, meaning sounds specific to the Arabic language, and the introduction of signs that convey vowels (the Arabic alphabet refers to the consonantal script (“abjad”), in which vowels within a word are usually not displayed in the letter). Changes in the alphabet were officially approved 18 October 1923 years by order of the People's Commissar of Education of the Turkestan ASSR.

Modified Arabic graphics did not last long. In 1929, in Samarkand, then the capital of the Uzbek SSR, the Republican Orthographic Conference was held, which approved a new Uzbek alphabet based on the Latin alphabet (“yanalif”). The Latin alphabet of the 1930s had 34 characters and was very different from the current Latin alphabet we are used to - try to read an advertisement in a 1933 magazine for comparison (see below).

However, the Latin alphabet was soon replaced. At 19In 40, the Supreme Council of the Uzbek SSR approved the Uzbek alphabet based on the Cyrillic alphabet, in which, with a slight change (for example, the apostrophe was replaced by the letter “b” in 1956), laws and decrees are still being issued, books and periodicals are being printed, typesetting sites.

Advertising on Gazeta.uz

In 1993, the law of the Republic of Uzbekistan “On the introduction of the Uzbek alphabet based on the Latin script” was adopted. Adviser to the Minister of Justice, blogger Shakhnoza Soatova recently voiced the opinion that the motives for switching to the Latin alphabet were political - "to move away from Soviet thinking." By the decision of the Supreme Council of the country of September 2, 19For 93 years, the full transition to the new alphabet was planned to be completed by the year 2000. However, in 1995, changes were made to the alphabet (it took on the form that we use now), and the full transition period was extended until 2005, and then until 2010. By 2010, the transition was not completed, and the country still uses two alphabets in parallel. Recently, the government approved a new "deadline" - January 2023: by this moment everyone should switch to the "improved" version of the Uzbek Latin alphabet. nine0003

By 2010, the transition was not completed, and the country still uses two alphabets in parallel. Recently, the government approved a new "deadline" - January 2023: by this moment everyone should switch to the "improved" version of the Uzbek Latin alphabet. nine0003

It turns out that the proposed replacement of the alphabet is already the fifth in the last 100 years, not counting changes to the spelling rules that were made in the intervals.

An interesting point. Most languages use the same alphabet no matter where the language is used. Iranians living outside of Iran write in the same Arabic script as in Iran itself. For the Russian language, the same Cyrillic alphabet is used in Russia itself, in the CIS countries and throughout the world. nine0003

The Uzbek language is an exception in this respect. Uzbeks living in Uzbekistan write in parallel in Cyrillic and Latin. Cyrillic is used in the CIS countries. For example, in Kyrgyzstan, textbooks for Uzbek-teaching schools are still published in Cyrillic. Afghanistan uses Arabic script - for an example, you can look at the BBC page in Uzbek, intended for residents of this country.

Afghanistan uses Arabic script - for an example, you can look at the BBC page in Uzbek, intended for residents of this country.

The variety of writing systems for transmitting texts in the same language cannot but have a negative impact on communication between native speakers from different countries, as well as on research in the field of computational linguistics (for example, machine translation). nine0031

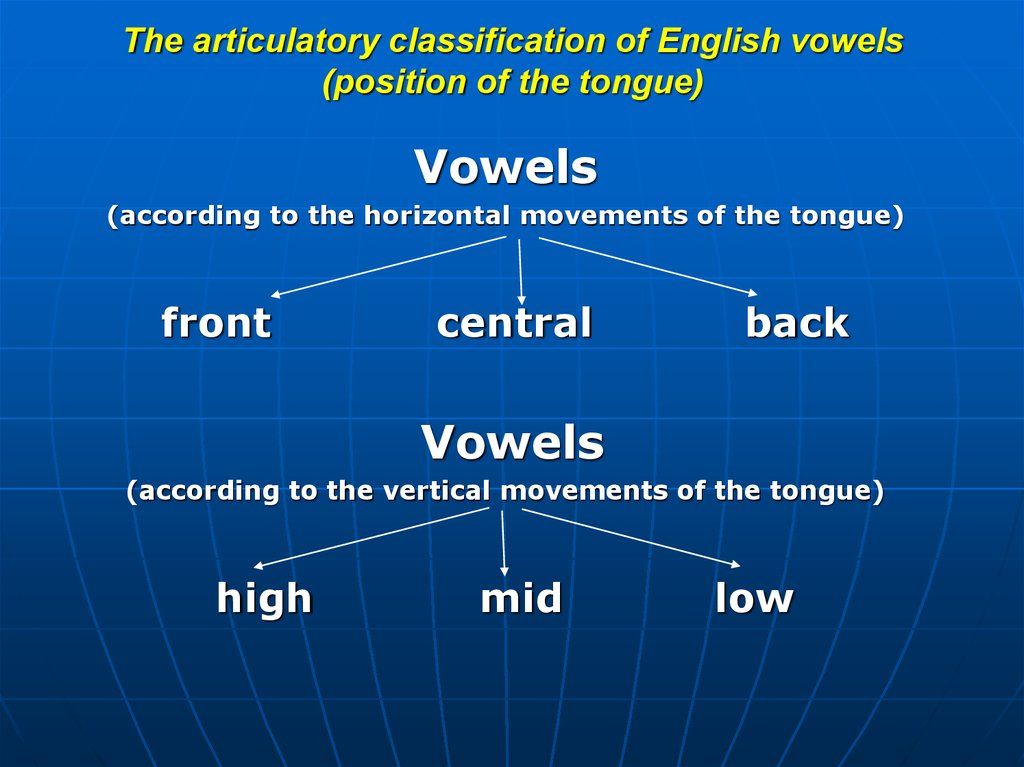

Theoretical digression

A small theoretical digression that will allow us to understand whether changes to the alphabet are needed and, if so, which ones. Scientists studying the process of reading and understanding have come to the conclusion that when we read, we do not decode individual letters one by one in order to understand the word, but we perceive the whole word. Let's do an experiment. Try to read: "Kshoka from home - bears to dance." Despite the errors in individual letters, you were able to read and understand the sentence, as the brain perceives the words as a whole, and not individual letters. nine0003

nine0003

The alphabet is a system of conventional signs, like, say, mathematical signs or modern emoji, and in this system, certain symbols correspond to sounds (more precisely, phonemes). As soon as a person studying a language has learned which symbols correspond to which sounds, has created a “sound-symbol” association for himself, the meaning of these symbols is lost. That is, it makes no difference whether, for example, the sound “sh” is conveyed by the symbol “ş”, as in Turkish or the proposed version of the Uzbek alphabet, “sh”, as in English or the current version of Uzbek, “sch”, as in German, or "ch" as in French. What association is accepted in society, that person will remember and use in the future. nine0003

Another important point. There are many languages, and each language has its own system of phonemes. And the writing systems (alphabets) used to transmit texts in these languages are much smaller. Since the most common writing systems today (for example, Latin) were created for a particular language (for example, for Latin), naturally, they cannot display all the phonemes of those languages for which they later began to be applied.

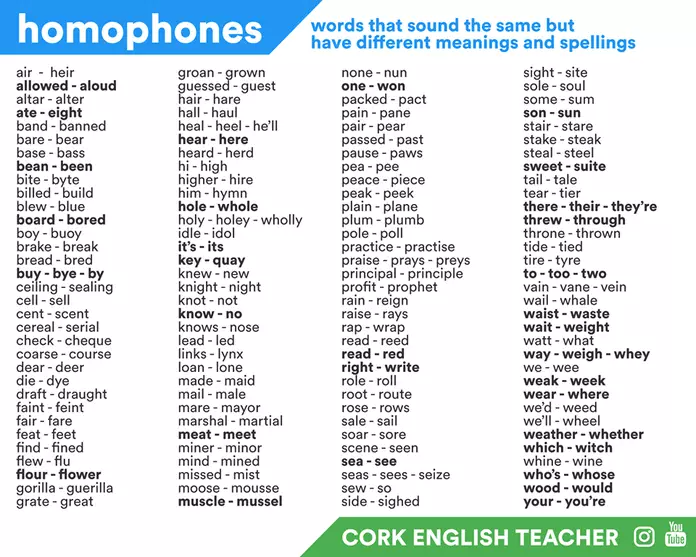

For example, 44 sounds of the English language are transmitted by only 26 Latin letters (and without the use of any special letters or diacritics). This means that a combination of several letters can correspond to one sound (for example, "sh", "ch" or "th"), just as the same letter or a combination of letters in different positions can convey different sounds (for example, the letter " a" in the words "can" and "call"). nine0003

An example from Russian. In the word "milk", the first "o" and the last "o" denote different sounds, that is, different phonemes are transmitted by the same symbol.

The alphabet is not a phonetic transcription, where each phoneme must correspond to only one character. Yes, there are languages whose alphabets have an almost perfect sound-to-letter correspondence, but there are relatively few such languages. In many languages, for various reasons, this ratio is violated. For example, in the Uzbek Cyrillic alphabet, different sounds can also be transmitted by the same letter, and one letter can mean several sounds. nine0003

nine0003

For example, for two completely different sounds (“zhzha” and “journal”), the same letter “zh” is fixed, and the sound ŋ, specific for the Turkic languages, found in separate words (for example, “singil”), is conveyed by the combination two letters - "ng". By the way, we see the same thing both in the current and in the proposed versions of the Uzbek Latin alphabet.

Or the letter "e" in the Uzbek Cyrillic alphabet, depending on the location, can mean one sound or two sounds (compare: "ber" - "er").

For such cases, there is the concept of the "alphabet principle", according to which the relationship between symbols in the alphabet and sounds does not have to follow the principle of "one sound - one letter", but these relationships must be systematic and predictable. That is, there are certain rules by which we write and pronounce words in a language.

An example of how the alphabetical principle works in the Uzbek language. In the words "maktab", "kitob" and "maktabim", "kitobim" the letter "b" conveys different sounds, but there is a rule that tells us that in both cases the same letter should be written. nine0003

nine0003

In summary. It is perfectly normal when, to convey one sound, you have to use not one character, but a combination of several characters. And it is perfectly normal when the same character in the alphabet conveys different sounds of the language.

Alphabet of Discord

On the portal for discussing draft regulations, the proposed draft law remains one of the leaders in terms of the number of views and comments. It is understandable - everyone uses the alphabet, changes will affect each of us in one way or another. Among the participants in the discussion, there are those who support the changes, and there are many who are strongly opposed. There are even those who offer their own, alternative versions of the alphabet. In a survey conducted in the Telegram channel of Gazeta.uz and in the comments on the website page, opinions were also sharply divided. nine0003

One cannot speak of unanimity among specialists either. Linguist, anthropologist Eldar Asanov expressed the opinion that the proposed version of the alphabet is imperfect, and it is better to continue using the current alphabet until it becomes possible to introduce a more perfect alphabet. One of the problems of the proposed option, in his opinion, is that the alphabet does not reflect synharmonism (consonance of vowels).

One of the problems of the proposed option, in his opinion, is that the alphabet does not reflect synharmonism (consonance of vowels).

One of the interlocutors with whom the author spoke on condition of anonymity, a private publisher, agrees that the proposed version of the alphabet is imperfect, since it does not reflect all the sounds specific to the Uzbek language. At the same time, he believes that the proposed option will ensure the integrity of the text in visual perception due to the absence of inverted apostrophes. nine0003

Another specialist, a philologist with an academic degree, with whom the author spoke, does not agree with the opinion about synharmonism. He believes that the phenomenon of synharmonism has been preserved only in certain dialects of the Uzbek language, but not in the literary language, so there is no need to introduce additional vowels into the alphabet. The National Encyclopedia of Uzbekistan also notes that the law of synharmonism is not observed in modern Uzbek.

Professor of the Tashkent State University of Uzbek Language and Literature, one of the authors of the Uzbek language textbook for schools Bakhtiyor Mengliev on his Facebook page indicated that “there are no perfect alphabets”, and the complex composition of the Uzbek language (an abundance of dialects) dooms attempts to improve the alphabet to failure. In his opinion, it is impossible to carry out the reform of the alphabet in a hurry, without weighing all the pros and cons, and the proposed reform "does more harm than good." nine0003

Another point that also divided people who are not indifferent to the problem is the absence of a letter corresponding to "ts" in Cyrillic. Some believe that the sound "ts" is not inherent in the Uzbek language and there is no need for a separate letter for it. Others argue that a fairly large number of words (including scientific terms) where “ts” is present have entered the Uzbek language. In addition, "ts" is used in the names of their own representatives of different nationalities ("Tsoi", for example). On this basis, they insist on fixing the Latin "c" in the alphabet. By the way: there is no “c” in the current version of the Latin alphabet, although it was in the first version of the alphabet adopted in 1993 year.

Another question pointed out by some participants in discussions around the alphabet. In both the current and proposed versions of the Uzbek Latin alphabet, the Cyrillic letters "h" and "x" correspond to "h" and "x". Some suggest leaving only the "h" and dropping the "x". They justify their opinion by the fact that the sound "x" is not characteristic of the Turkic languages and many people do not distinguish between "h" and "x", which leads to errors in writing. This point of view, for example, was supported by the entrepreneur and publisher Firuz Allaev. However, there is another side of the coin. The difference between "h" and "x" can be important for the meaning of the statement. For example, compare "shoh" - "branch" and "shoh" - "king". nine0003

In the midst of controversy in social networks, attention was drawn to another problem with the current version of the Latin script - incorrect perception (separation) of words with an apostrophe by computer systems. That is, words such as, for example, "O'zbekiston" (in case of incorrect input), "ta'lim" are not perceived by computer systems as one word. This creates certain problems for programmers and specialists in the field of computational linguistics, and also complicates the automatic search and systematization of information. nine0003

That is, words such as, for example, "O'zbekiston" (in case of incorrect input), "ta'lim" are not perceived by computer systems as one word. This creates certain problems for programmers and specialists in the field of computational linguistics, and also complicates the automatic search and systematization of information. nine0003

The philologists and teachers with whom the author spoke were mostly against the proposed changes. One of the interlocutors said that there was no logic in the proposed changes. As a specialist who studies the processes of mastering the native language, he believes that these changes will lead to a slowdown in the processes associated with the perception of the written text, for everyone - both for those who have learned to read in Cyrillic, and for those who have already been taught in the current Latin alphabet .

Another interlocutor, a school teacher, inquired about the costs involved in changing the alphabet. After all, it will be necessary to replace all documents, forms, seals, inscriptions on streets, buildings, entrances to settlements, reprint textbooks, books, dictionaries, maps. nine0003

nine0003

The third interlocutor believes that the changes were proposed by "people who want to curry favor", and after some time we can again raise the issue of changes to the alphabet "to please some official." He recalled that we had to change the alphabet too often, which is not good. (at 1922, 1929, 1934, 1940, 1956, 1993, 1995) the old linguodidactic model was destroyed and time, effort and money were spent to create a new one. With each such attempt, changes were made to the linguistic consciousness of the Uzbeks, and this could not but affect the standard Uzbek language. As a consequence, the language could not fully develop in any of these periods when the alphabet changed” (pp. 8-9).

Need a replacement?

In the explanatory note attached to the bill, the developers explained the need to improve the alphabet by the need to complete the full transition to the Latin alphabet, as well as by the desire to strengthen the authority of the Uzbek language within the country and in the world. nine0003

nine0003

Let's start with the authority of the language. As I said above, the alphabet is just a system of conventional signs. For the authority of the Uzbek language both within the country and in the world, it does not matter at all what symbols we designate certain sounds with.

The authority of the English language in the world is not strengthened by the alphabet. Above, I gave an example of the fact that not all English sounds are displayed in a letter with one letter and that the same letter does not always denote the same sound. The authority of the English language is supported by the abundance and quality of scientific, popular science, technical and other literature (including media - films, songs, computer programs and games) in this language, as well as the position of English-speaking countries in the world economy, politics, science and education. nine0003

Therefore, if we want to strengthen the authority of the Uzbek language, it is worth thinking about the quantity and quality of various kinds of content in this language.

And frequent changes in the alphabet can tear off the next generations from the accumulated baggage of information fixed in the previous alphabet (previous alphabets), and in no way contribute to strengthening the authority of the language.

With regard to the completion of the full transition to the Latin alphabet. In an explanatory note, in my opinion, it would be worth explaining exactly what problems associated with the current version of the Latin script hinder a complete transition and how the proposed version will eliminate these problems. nine0003

How is the proposed version of the alphabet more convenient, more perfect, closer to the Uzbek language than the current version? Is the proposed version of the alphabet able to put an end to this protracted epic with the transition once and for all? Will it not turn out that instead of two parallel alphabets we will use three? Will there be questions about the problems of the proposed version after a while? Unfortunately, the authors of the project did not answer these questions.

The questions are by no means idle, and they arise not only from me. For example, in a special group on Facebook dedicated to the Uzbek language, the question was raised about the appropriateness of replacing “sh” and “ch”, as well as the possibility of developing a keyboard for the correct input of “oʻ” and “gʻ”. Such questions should not be brushed aside, they should be given reasonable answers. After all, the questions of the alphabet and spelling, as I said above, concern everyone. nine0003

In my opinion, if the current version of the Latin alphabet was somehow flawed, unable to convey the text in the Uzbek language, we would not be able to print documents during this time, publish books, textbooks, newspapers, magazines, write ads, communicate in social networks, make up websites in Latin. But it's not like that.

As for convenience or beauty, you will agree that these concepts are relative. On the one hand, the current version of the Latin alphabet is convenient in that it allows you to type text on a standard QWERTY keyboard, which is found in any computer or smartphone. And the proposed letters with diacritical marks will have to be installed separately. Moreover, if "ş" or "ç" can be found in Turkish or Azerbaijani layouts, then the letters proposed to replace the current "o'" or "g'" ("o" and "g" with a straight dash at the top) must also search - according to the Wikipedia review, there are no such letters in the alphabets of other languages \u200b\u200busing the Latin script. nine0003

And the proposed letters with diacritical marks will have to be installed separately. Moreover, if "ş" or "ç" can be found in Turkish or Azerbaijani layouts, then the letters proposed to replace the current "o'" or "g'" ("o" and "g" with a straight dash at the top) must also search - according to the Wikipedia review, there are no such letters in the alphabets of other languages \u200b\u200busing the Latin script. nine0003

Many signs make mistakes. Photo: Shukhrat Latipov / Gazeta.uz.

On the other hand, the abundance of inverted apostrophes in words (for example, "qo'rg'on") complicates the perception of words, and for many such spelling may seem ugly. In addition, looking at, for example, publications on social networks, it is easy to notice that when writing the letters "o'" and "g'" many people make a mistake using various other characters instead of an inverted apostrophe.

As a philologist, when analyzing the proposed version, it is not entirely clear to me what principle was followed in its development. If, for example, the authors wanted to fix a separate letter for each sound, this principle is not observed, just as in the Uzbek Cyrillic or the current Latin alphabet (see above examples with "zh" and "ng").

If, for example, the authors wanted to fix a separate letter for each sound, this principle is not observed, just as in the Uzbek Cyrillic or the current Latin alphabet (see above examples with "zh" and "ng").

The principle of selecting diacritical marks is also not entirely clear. If we decide to introduce letters with diacritics into the alphabet, why not use those letters that are present in the same keyboard layout to facilitate text input? nine0003

Another interesting point. The proposed version contains "ç", a derivative of "c", but the letter "c" itself was decided not to be included. Will this create problems when learning the alphabet?

The alphabet is not a piece of clothing or a technique that you can change when you don't like it. Otherwise, the Germans, perhaps, would have changed the alphabet long ago, which makes them write as many as four letters for one sound “h” in the self-name of the country “Deutschland” (Germany).

Each replacement of the alphabet or even changes in individual characters, in addition to huge budget expenses, entails a gap between generations, loss of access to the accumulated knowledge base and a certain slowdown in the development of the language, and also changes people's attitude towards the language.

Learn more