What is literacy skill

What is literacy? | National Literacy Trust

The importance of literacy

Lacking vital literacy skills holds a person back at every stage of their life. As a child they won't be able to succeed at school, as a young adult they will be locked out of the job market, and as a parent they won't be able to support their own child's learning. This intergenerational cycle makes social mobility and a fairer society more difficult.

People with low literacy skills may not be able to read a book or newspaper, understand road signs or price labels, make sense of a bus or train timetable, fill out a form, read instructions on medicines or use the internet.

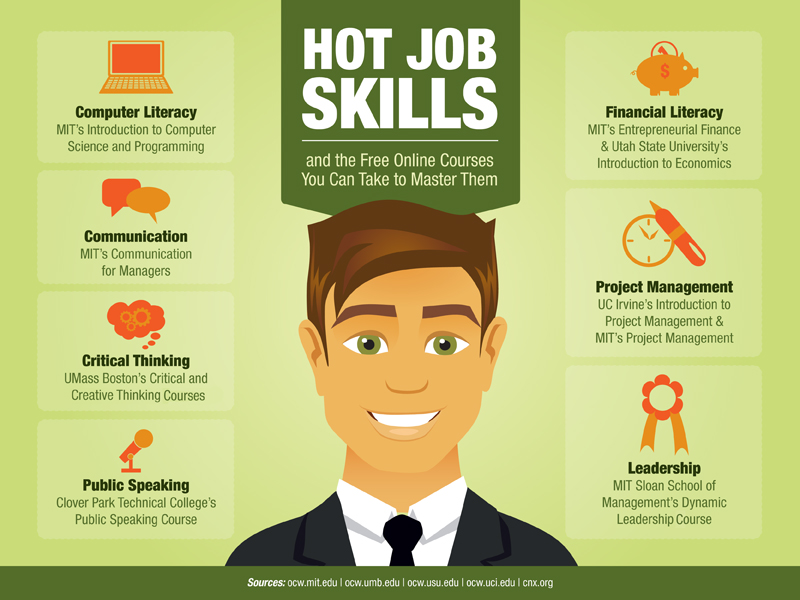

Low levels of literacy undermine the UK’s economic competitiveness, costing the taxpayer £2.5 billion every year (KPMG, 2009). A third of businesses are not satisfied with young people’s literacy skills when they enter the workforce and a similar number have organised remedial training for young recruits to improve their basic skills, including literacy and communication.

COVID-19 Research and Policy Observatory

Our research and policy observatory includes up-to-date research, policy and analysis on the impact of COVID-19 on children and young people’s learning, literacy and wellbeing.

Find out more.Literacy statistics

Our research underpins our programmes, campaigns and policy work to improve literacy skills, attitudes and habits across the UK.

-

Children who enjoy reading and writing are happier with their lives

Children who enjoy reading are three times more likely to have good mental wellbeing than children who don’t enjoy it. Read more.

-

1 in 11 disadvantaged children in the UK say that they don’t have a book of their own

Children who say they have a book of their own are six times more likely to read above the level expected for their age than their peers who don’t own a book.

Read more.

Read more. -

Children born into communities with the most serious literacy challenges have some of the lowest life expectancies in England

A boy born in Stockton Town Centre (an area with serious literacy challenges) has a life expectancy 26.1 years shorter than a boy born in North Oxford. Read more.

-

1 in 2 children in the UK enjoy reading

Only 1 in 2 children and young people said they enjoy reading in early 2022, which is as low as the number has ever been since we first asked the question in 2005. Read more.

-

2 in 5 children in the UK enjoy writing

In 2022, 2 in 5 children and young people said that they enjoy writing, a slight recovery from 2021, when it was at the lowest level we have recorded since 2010. Read more.

-

Audiobooks can support wider literacy engagement

1 in 5 children and young people said that listening to an audiobook or podcast has got them interested in reading books.

Read more.

Read more.

See more of our research reports.

Adult literacy rate

16.4% of adults in England, or 7.1 million people, can be described as having 'very poor literacy skills.' Adults with poor literacy skills will be locked out of the job market and, as a parent, they won’t be able to support their child’s learning.

Find out more.More information

-

How does England's literacy compare with other countries?

How does literacy in England stack up against other European countries?

Learn more -

Education in England, Wales, Northern Ireland & Scotland

How does the national curriculum work in England, Wales, Northern Ireland & Scotland?

Learn more -

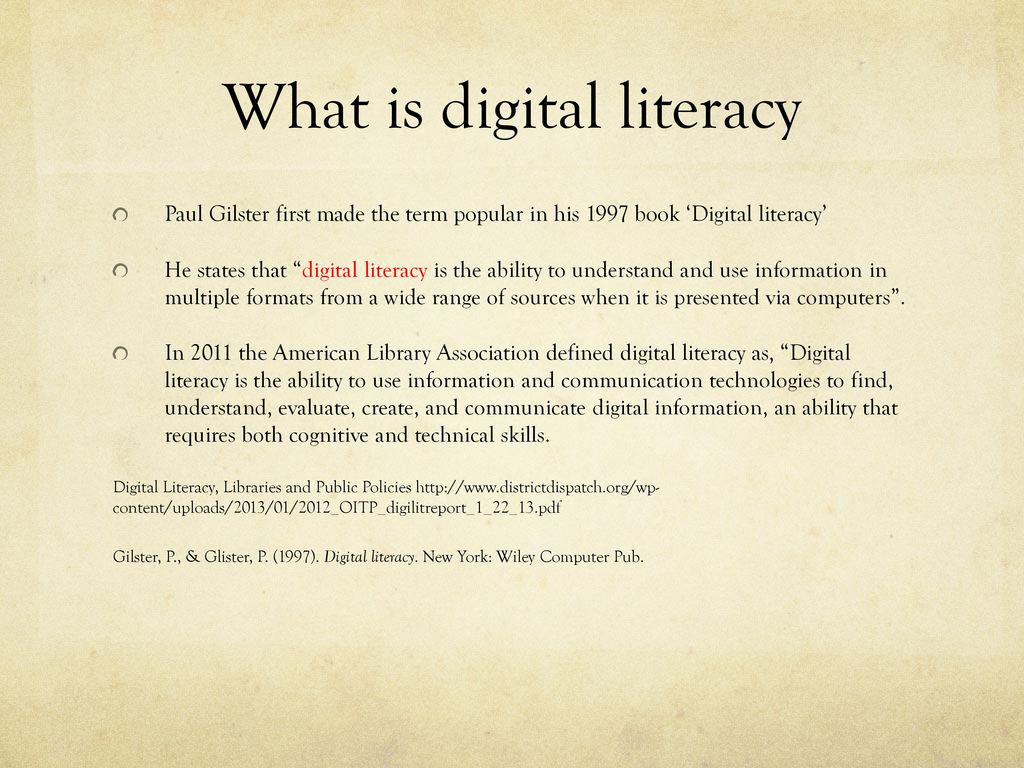

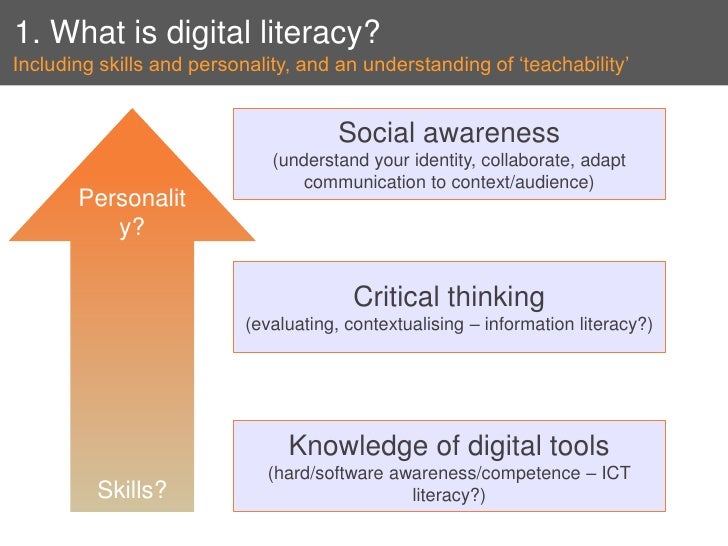

Literacy and digital technology

What opportunities and challenges does digital technology present to children's literacy?

Learn more

What are literacy skills? | Thoughtful Learning K-12

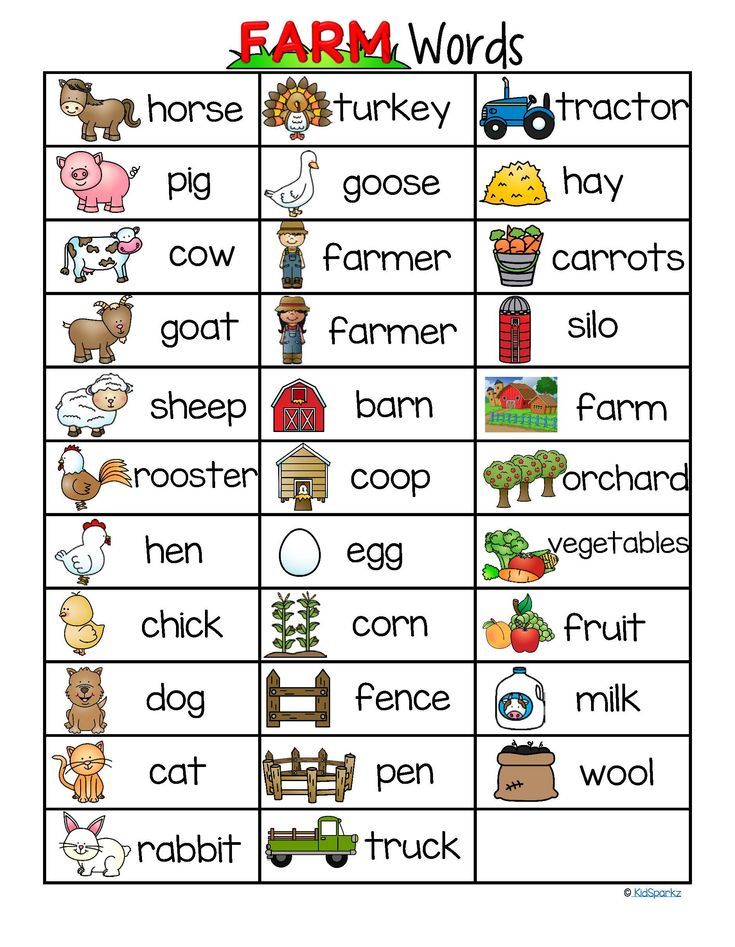

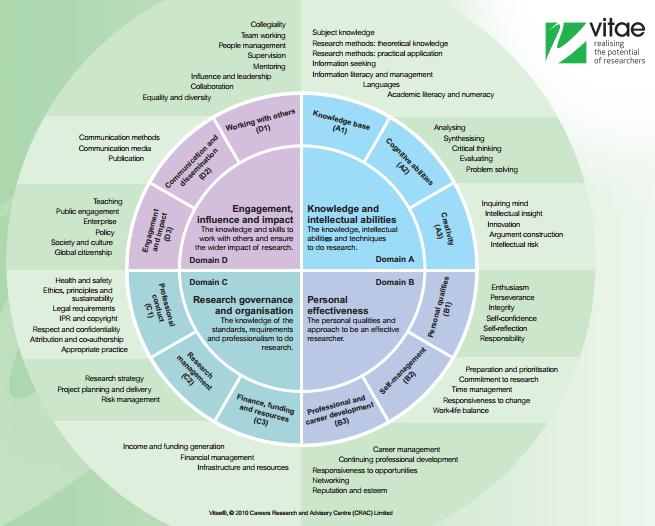

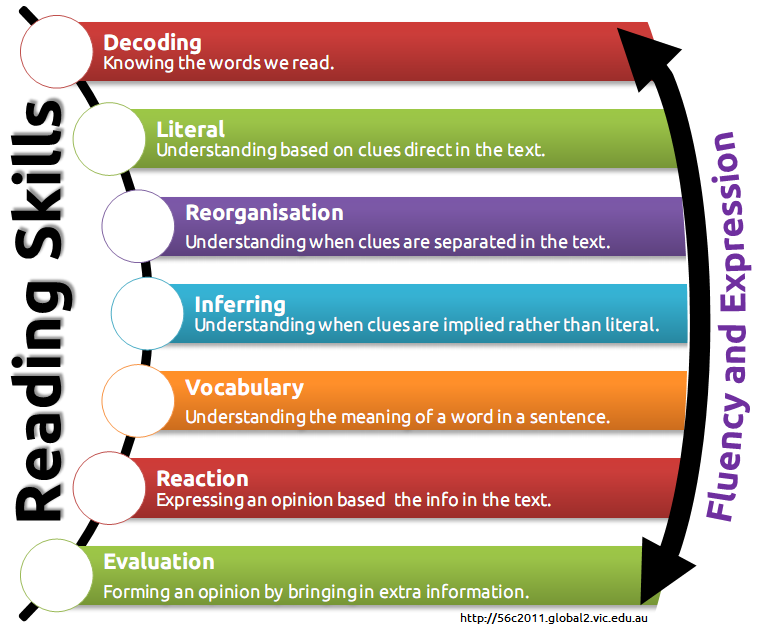

Literacy skills help students gain knowledge through reading as well as using media and technology. These skills also help students create knowledge through writing as well as developing media and technology.

These skills also help students create knowledge through writing as well as developing media and technology.

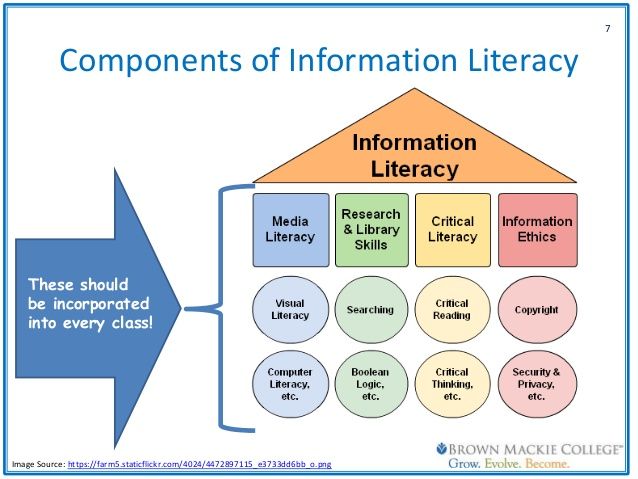

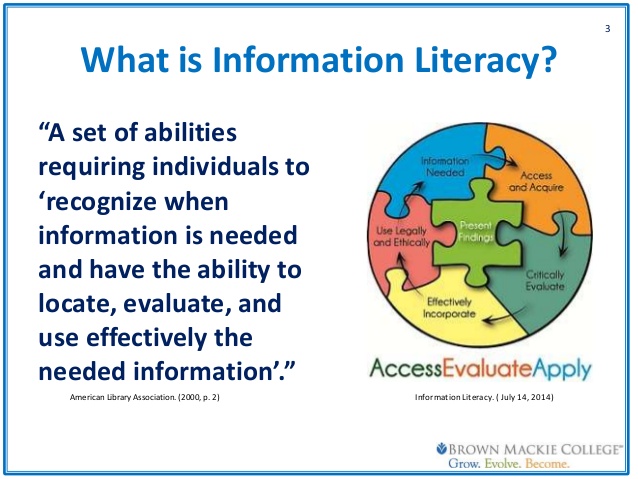

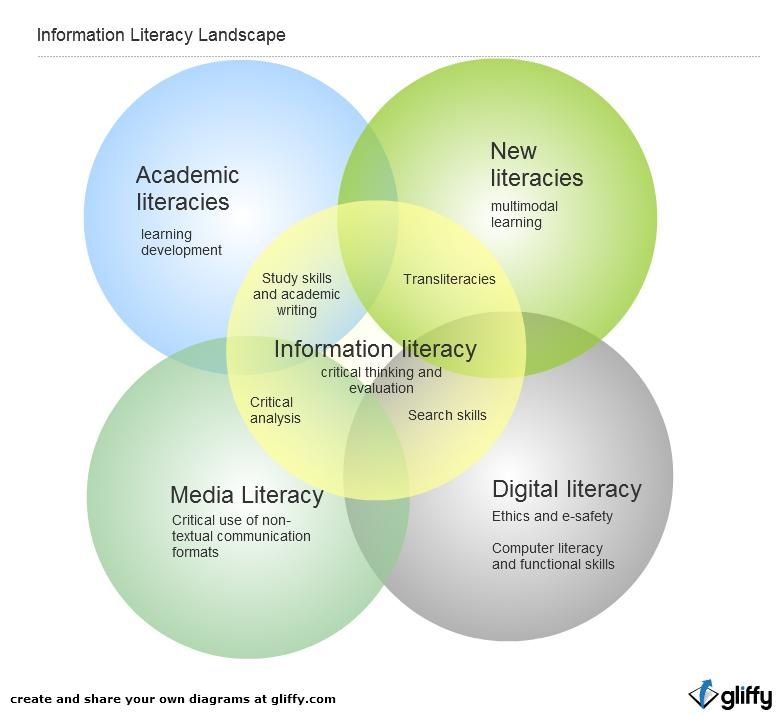

Information Literacy

Students need to be able to work effectively with information, using it at all levels of Bloom's Taxonomy (remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating). Information literacy involves traditional skills such as reading, researching, and writing; but new ways to read and write have also introduced new skills:

- Consuming information: The current excess of information requires students to gain new skills in handling it. When most information came through official publications like books, newspapers, magazines, and television shows, students encountered data that had been prepared by professionals. Now, much information is prepared by amateurs. Some of that work is reliable, but much is not.

Students must take on the role of the editor, checking and cross-checking information, watching for signs of bias, datedness, and errors. Students need to look at all information as the product of a communication situation, with a sender, subject, purpose, medium, receiver, and context.

Students must take on the role of the editor, checking and cross-checking information, watching for signs of bias, datedness, and errors. Students need to look at all information as the product of a communication situation, with a sender, subject, purpose, medium, receiver, and context. - Producing information: In the past, students were mostly consumers of information. When they produced information, it was largely for a single reader—the teacher—and was produced for a grade. It was therefore not an authentic communication situation, and students felt that writing was a purely academic activity. Now writing is one of the main ways students communicate. It has real-world applications and consequences. Students need to understand that what they write can do great good or great harm in the real world, and that how they write determines how powerful their words are. Students need to take on the role of professional writers, learning to be effective and ethical producers of information.

Media Literacy

Media literacy involves understanding the many ways that information is produced and distributed. The forms of media have exploded in the last decade and new media arrive every day:

Students' use of media has far outstripped educational use, and students will continue to adopt new media long before teachers can create curricula about it. It is no longer enough to teach students how books, periodicals, and TV shows work. Students need to learn how to critically analyze and evaluate messages coming to them through any medium.

As with information literacy, the key is to recognize the elements of the communication situation—sender, message (subject and purpose), medium, receiver, and context. These elements are constant regardless of the medium used. By broadening the student's perspective to see all media as part of a larger communication situation, we can equip students to effectively receive and send information in any medium. Students must learn to recognize the strengths and weaknesses of each medium and to analyze each message they receive and send.

Technology Literacy

We are living through a technological revolution, with huge changes taking place over brief spans of time. A decade ago, Facebook didn't exist, but now many people could not live without it. The average cellphone is now more powerful than computers from several years ago. We are surrounded by technology, and most of it performs multiple functions. In Growing Up Digital: How the Net Generation Is Changing Your World, Don Tapscott outlines the following eight expectations that students have of technology.

- Freedom to express their views, personalities, and identities

- Ability to customize and personalize technology to their own tastes

- Ability to dig deeper, finding whatever information they want

- Honesty in interactions with others and with organizations

- Fun to be part of learning, work, and socialization as well as entertainment

- Connecting to others and collaborating in everything

- Speed and responsiveness in communication and searching for answers

- Innovation and change, not settling for familiar technologies but seeking and using what is new and better

As you can see, students expect a great deal out of their technologies. You can help them use technology wisely:

You can help them use technology wisely:

- reading Web sites;

- using search engines;

- using map searches;

- accessing videos, podcasts, and feeds;

- evaluating Web resources;

- researching on the Internet;

- e-mailing, chatting, texting, microblogging;

- using social sites;

- visiting virtual worlds;

- blogging and using wikis; and

- using message boards, newsgroups, and VOIP (Skype).

By understanding how to evaluate this new information and how to use these new tools to create effective, well-grounded communication, students can harness the power of new technology and be inspired to learn.

LITERACY • Great Russian Encyclopedia

LITERACY, a certain degree of a person's proficiency in reading and writing in accordance with grammar. native language rules. One of the most important indicators of the socio-cultural development of the population. The specific content of the concept of "G." changed historically, expanding with the growth of societies. requirements for the socialization of the individual: from the simple ability to read - to the ability to read, write and perform elementary calculations. In the last decades of the 20th century in countries that have reached the universal level of education of the population, an indicator of the general level of education of the population is used. G. indicator retains its value in the historical. evaluation of cultural development.

The specific content of the concept of "G." changed historically, expanding with the growth of societies. requirements for the socialization of the individual: from the simple ability to read - to the ability to read, write and perform elementary calculations. In the last decades of the 20th century in countries that have reached the universal level of education of the population, an indicator of the general level of education of the population is used. G. indicator retains its value in the historical. evaluation of cultural development.

According to UN statistics, in 2000 there were 862 million illiterates (aged 15 and over) in the world, which is approx. 20% of the world's adult population. In order to attract communities. attention to this problem in 2001, the UN proclaimed the 10th anniversary of literacy (2003-12) and set a specific task: through targeted work with the relevant local socio-cultural categories of the population, to significantly raise the level of G. From 1966 is marked by International. literacy day (Sept. 8).

literacy day (Sept. 8).

The need for grammar and literacy arose in early class society and was associated with the appearance of writing.

In traditional societies. type G. - the property of the upper strata of society and some social categories associated with the system of management and service of letters. culture. The need for geology was felt by both the trade and artisan strata of the population, for whom the ability to read, write, and count is determined by the nature of their activities.

On the whole, it can be assumed that in the traditional European society at the end of the Middle Ages, approximately 10–15% of the population were literate, predominantly. urban. The peasantry (the main class of this society) remained illiterate. Real data on the state and development of G. of the population in the department. countries of Europe in the Middle Ages and during the transition to the New Age are fragmentary, concern only certain categories of the population (for example, recruits, newlyweds).

Main historical the reason that called for the need for universal geography was modernization. There are three major historical stage, reflecting a chronologically uneven picture of the entry of otd. groups of countries in the process of realizing universal literacy.

During the Reformation period, universal (in various forms) literacy education began to be implemented in a group of countries located around the basin of the North and Baltic Seas (England, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, numerous German principalities, Denmark, Holland, Switzerland ), which was connected with the opportunity and the need for everyone to read the Bible.

In the Age of Enlightenment France, the Habsburg Monarchy (Austria, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Hungary, Croatia, Slovakia, Northern Italy), the Commonwealth, Belgium joined this process.

In the 2nd half. 19th century countries of the southwest, south, southeast and east of Europe were involved in the process of universal literacy - from Portugal and Spain, South. Italy to the Balkan states (Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, Romania).

Italy to the Balkan states (Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, Romania).

In the first group of countries, the general G. of the population (up to 99%) was achieved by the 1880s, in the second - in the 1930s, in the third - in the main. to con. 20th century (There were also movements of certain countries to another, higher, or, conversely, lower group.)

Literacy in Russia. A satisfactorily holistic picture of the development of geology in Russia, made with due regard for the relevant pan-European context, does not yet exist. The first attempts to comprehend this problem as a practical the task of the state politicians belong to Catherine II, who tried to use the experience of Austrian for Russia. educational school reform of 1774, which introduced universal 6-year primary education.

First Russian the census (1897) showed Russia's huge lag behind the absolute majority of European countries. G. of the population was only 24% (literate were those who could at least read; registration was made for persons aged 9 years and older). Within the country, there were significant differences in population size. So, in the Baltic provinces, its high level was noted (Estland - 95%, Lifland - 92%, Courland - 85%), and in the east. parts of Ros. empire, the population was almost completely illiterate.

Within the country, there were significant differences in population size. So, in the Baltic provinces, its high level was noted (Estland - 95%, Lifland - 92%, Courland - 85%), and in the east. parts of Ros. empire, the population was almost completely illiterate.

After Oct. revolution of 1917, the problem of the general population population is put forward as the most important practical. political tasks. Its complete and quick solution was supposed to be possible (in addition to the organization of school universal education) with the help of frontal literacy training for the entire illiterate population of the country. In 1919, the USSR adopted a decree of the Council of People's Commissars "On the elimination of illiteracy among the population of the RSFSR" from 8 to 50 years of age. Mass societies were included in this process. organizations. At 1920 SNK created Vseros. the Extraordinary Commission for the Elimination of Illiteracy (VChK l / b), which took control of the organization of educational courses, teacher training, and the publication of educational literature. Each locality with the number of illiterate St. 15 had to have a literacy school (liqpunkt, the term of study was 3-4 months). By the autumn of 1920, courses for the liquidators of illiteracy were created only by the forces of the Cheka l / b in 26 provinces. In the autumn of 1923, the Vseros was created. voluntary society “Down with illiteracy!”, which by the end of the year united St. 100 thousand members. In the RSFSR, the society contained (1924) St. 11 thousand likpoints (over 500 thousand students). In the 2nd floor. 1920s about-in suffered osn. work in the village. In 1926, the number of persons aged 9–49 was 56.6%. In total, up to 10 million adults were taught to read and write in 1917–27, including 5.5 million people in the RSFSR. Data from pre-war owls. censuses on the rapid growth of Georgia (in 1920 - 41.7% of the literate, in 1926 - 51.1%, in 1939 - 81.2%) seem to confirm the unambiguity of the political. conclusion that the USSR also became a country of continuous H. However, in the postwar period, data on H.

Each locality with the number of illiterate St. 15 had to have a literacy school (liqpunkt, the term of study was 3-4 months). By the autumn of 1920, courses for the liquidators of illiteracy were created only by the forces of the Cheka l / b in 26 provinces. In the autumn of 1923, the Vseros was created. voluntary society “Down with illiteracy!”, which by the end of the year united St. 100 thousand members. In the RSFSR, the society contained (1924) St. 11 thousand likpoints (over 500 thousand students). In the 2nd floor. 1920s about-in suffered osn. work in the village. In 1926, the number of persons aged 9–49 was 56.6%. In total, up to 10 million adults were taught to read and write in 1917–27, including 5.5 million people in the RSFSR. Data from pre-war owls. censuses on the rapid growth of Georgia (in 1920 - 41.7% of the literate, in 1926 - 51.1%, in 1939 - 81.2%) seem to confirm the unambiguity of the political. conclusion that the USSR also became a country of continuous H. However, in the postwar period, data on H. of the entire population (from 9years) are not published - they are replaced everywhere (with reference to the decree of 1919) by a sample of ages from 9 to 49 years (in 1897 - 28.4% of literates, in 1926 - 56.6%, in 1939 - 84.0%, in 1959 - 98.5%). Thus, the exclusion from the calculation of ages over 50 years gives by 1959 the "required" indicator of G., close to 100%.

of the entire population (from 9years) are not published - they are replaced everywhere (with reference to the decree of 1919) by a sample of ages from 9 to 49 years (in 1897 - 28.4% of literates, in 1926 - 56.6%, in 1939 - 84.0%, in 1959 - 98.5%). Thus, the exclusion from the calculation of ages over 50 years gives by 1959 the "required" indicator of G., close to 100%.

Post-war owls. censuses make it possible to reconstruct a more realistic picture of the process, taking into account its demographics. mechanism. Describing education. the structure of the population as a whole, these censuses do not exclude from the general population, but they do not single out as an independent category of people who do not have completed primary education, and people without education. Those in the total composition of the population of the USSR over 9years was: in 1959 - 32.9%, in 1970 - 22.4%, in 1979 - 11.3%, in 1989 - 5.5%. It is these data that reflect the real picture of the process of development of G. in the USSR and the forced formation of characteristics of education. structures of modern society.

in the USSR and the forced formation of characteristics of education. structures of modern society.

Ros. The population census (2002) showed that the proportion of people without completed primary education decreased to 1%, including illiterates - to 0.6%.

Literacy for all

Literacy is a human right and the basis for lifelong learning. It empowers individuals, families and communities and improves their quality of life. Through its “multiplier effect”, literacy contributes to eradicating poverty, reducing child mortality, curbing population growth, achieving gender equality and promoting sustainable development, peace and democracy.

In today's rapidly changing, knowledge-based society, where social and political participation takes place both physically and virtually, acquiring basic literacy skills, improving them and applying them throughout life is of paramount importance.

Since its founding in 1946, UNESCO has played an important role in the overall literacy effort.

UNESCO's current policy is to promote literacy and create an enabling environment, which is an integral part of lifelong learning. The organization is also committed to ensuring that literacy continues to be a priority both nationally and internationally. In an effort to realize the vision of universal literacy, the Organization works with countries and partners through literacy programmes, outreach and its knowledge base.

UNESCO's overall approach to literacy for all aims to:

- build a strong foundation through early childhood education and education;

- providing quality basic education for all children;

- scaling up literacy programs for youth and adults lacking basic literacy skills;

- creating an environment conducive to literacy.

Since the majority of the world's illiterate people are women, UNESCO encourages targeted initiatives such as the Global Partnership for Girls' and Women's Education.

UNESCO monitors global literacy levels through the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), the EFA Global Monitoring Report and regional assessment programs such as the Research Project on Literacy Assessment (RAMAA), the South and East Africa Consortium for Educational Quality Monitoring (SACMEC) and the Latin American Laboratory for the Evaluation of Educational Quality (LLECE).