What is phonological recoding

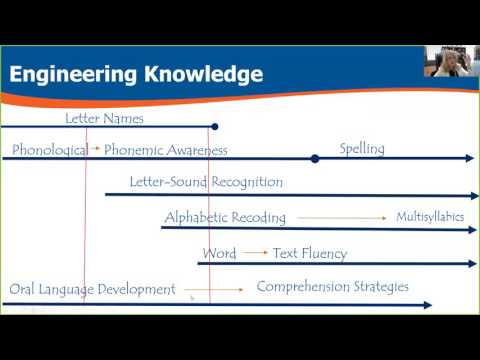

The Alphabetic Principle: From Phonological Awareness to Reading Words

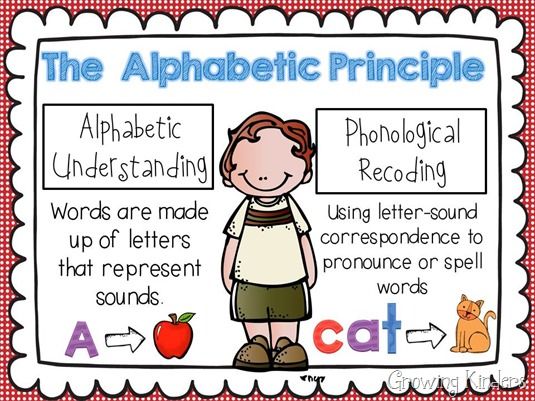

What Is The Alphabetic Principle?

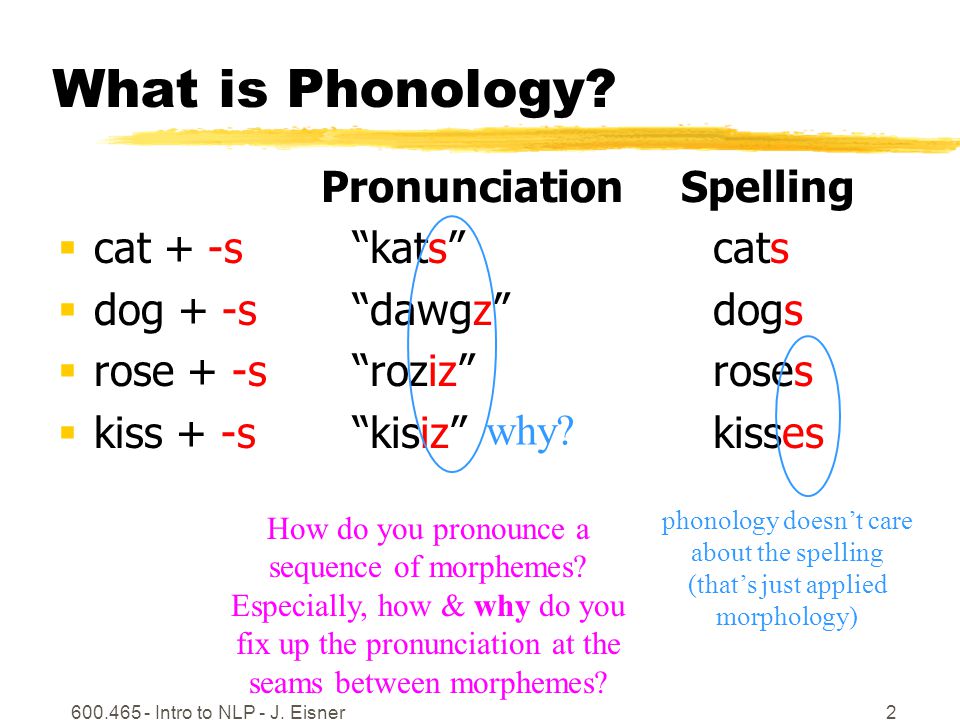

Connecting letters with their sounds to read and write is called the “alphabetic principle.” For example, a child who knows that the written letter “m” makes the /mmm/ sound is demonstrating the alphabetic principle.

Letters in words tell us how to correctly “sound out” (i.e., read) and write words. To master the alphabetic principle, readers must have phonological awareness skills and be able to recognize individual sounds in spoken words. Learning to read and write becomes easier when sounds associated with letters are recognized automatically.

The alphabetic principle has two parts:

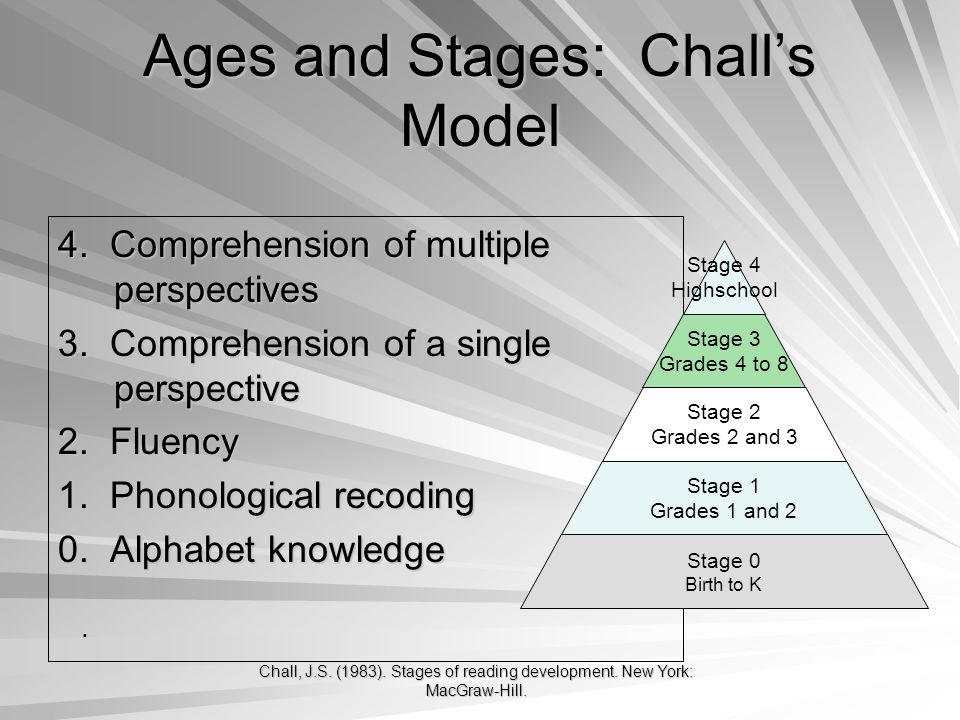

- Alphabetic understanding is knowing that words are made up of letters that represent the sounds of speech.

- Phonological recoding is knowing how to translate the letters in printed words into the sounds they make to read and pronounce the words accurately.

The alphabetic principle is critical in reading and understanding the meaning of text. In typical reading development, children learn to use the alphabetic principle fluently and automatically. This allows them to focus their attention on understanding the meaning of the text, which is the primary purpose of reading.

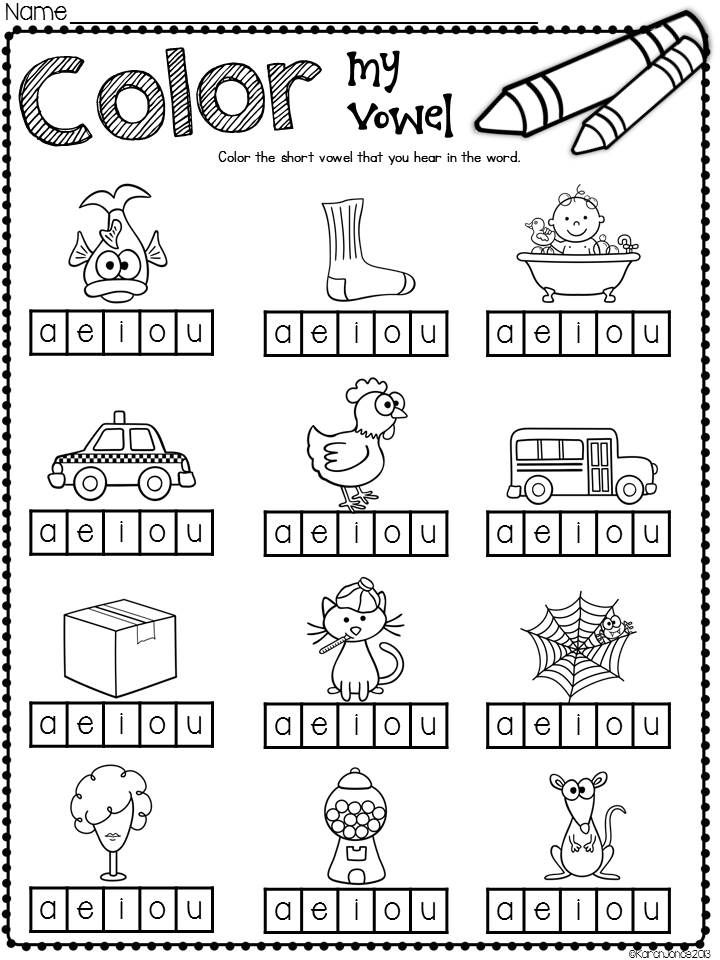

Learning and applying the alphabetic principle takes time and is difficult for most children. There are many letters to learn the sounds of, and there are many ways to arrange the letters to produce the vast number of different words used in print. Also, in English, the same letter can represent more than one sound, depending on the word (e.g., the /a/ sounds are different in the words “mat” and “mate”). In Spanish, by contrast, which also includes the vowel “a” in its alphabet, the /a/ sound is always pronounced the same way (e.g., the /a/ in “casa”) regardless what word it is in.

Irregular Words

Some words, called irregular words, cannot be read accurately using the alphabetic principle to “sound them out” (e. g., the words “was,” “is,” and “know” are not accurately pronounced using phonics rules). Irregular words require a different teaching approach than teaching how to read words that follow a rule-based, letter-sound structure.

g., the words “was,” “is,” and “know” are not accurately pronounced using phonics rules). Irregular words require a different teaching approach than teaching how to read words that follow a rule-based, letter-sound structure.

Despite the presence of irregular words, learning the alphabetic principle thoroughly and using it to read unfamiliar words, is a much better strategy than trying to memorize how to accurately read each word as a whole word, or guessing what the word might be based on its first letter and the words before or after it in the text.

Explicit Phonics Instruction

Explicit phonics instruction—i.e., how the alphabetic principle works, step by step—and extensive practice enables most children to learn the alphabetic principle. Below are effective strategies for teaching the alphabetic principle. These same strategies can be used with children who struggle learning to read, including children with reading disabilities or dyslexia. For students who struggle, highly systematic and explicit instruction plus lots of accuracy practice will be necessary for them to learn the alphabetic principle thoroughly.

All alphabetic languages can be taught using phonics and the alphabetic principle to guide instruction. However, alphabetic languages—English, Spanish, French, Turkish, Vietnamese, and many others—differ dramatically in their alphabetic principle complexity. For example, English is quite complex—there are many rules and exceptions to those rules that need to be learned to read and write correctly. Spanish is much less complex. Letters typically make only one sound regardless of the word they are in and rule exceptions are very few compared to English. For example, Spanish vowels only make one sound. In some cases, the vowel is silent as the letter “u” is in the word, “que.”

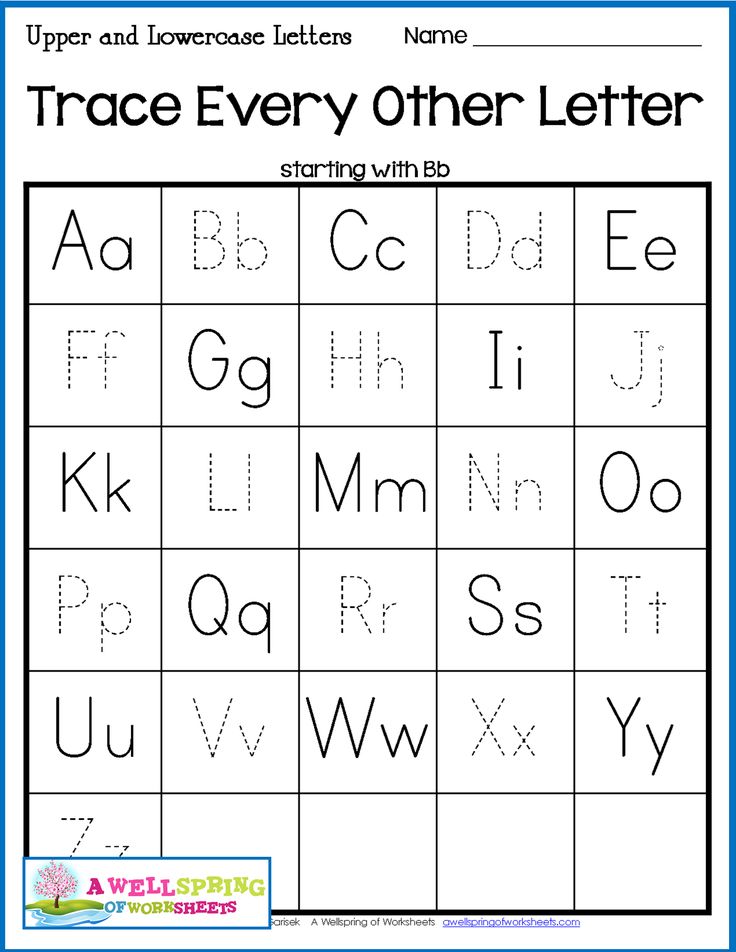

Teach Students To Connect Letters To Their Most Common Sound Or Sounds

All 26 letters in English make at least one predictable or common sound depending on the other letters in the word. For example, each of the three letters in the word “mat” makes its most common sound. In the word “meat” the “m” and “t” make the same sound as they do in “mat” and the “ea” letter combination makes its most common sound when these letters are together in a word. Notice that in the word “meat,” there is only one sound for “ea” even though there are two letters. Teachers can sequence and deliver instruction in a way that helps students efficiently learn the “rules” for the different sounds that letters and letter combinations make.

Notice that in the word “meat,” there is only one sound for “ea” even though there are two letters. Teachers can sequence and deliver instruction in a way that helps students efficiently learn the “rules” for the different sounds that letters and letter combinations make.

Teach Students To Read Words Using What They Know About The Sounds That Letters And Letter Combinations Make

In using the alphabetic principle, students “blend” the sounds made by individual letters into a whole word. For example, the sounds /m/ /a/ /t/ made by the letters “m,” “a,” and “t” are blended together seamlessly to make the word “mat.” Students should begin learning to read by producing the individual sounds in words and blending the sounds together quickly to produce the whole word with simple CVC words (consonant-vowel-consonant) before progressing to more complex word types that follow other important phonics rules. During instruction, teachers can use a strategy such as “I Do, We Do, You Do” to show students what to do (how to blend), practice with them (students do it with the teacher), and then the students do it on their own to show their teacher they know how to do it. Teaching several of the most common sounds for a few individual letters allows students to read many different words depending on letter order. Teaching other rule types (e.g., letter combinations such as “ea” and “th,” the “Bossy E” rule when “e” comes at the end of a CVC word, and so forth) enables students to accurately read a vast number of words they have never encountered in text.

Teaching several of the most common sounds for a few individual letters allows students to read many different words depending on letter order. Teaching other rule types (e.g., letter combinations such as “ea” and “th,” the “Bossy E” rule when “e” comes at the end of a CVC word, and so forth) enables students to accurately read a vast number of words they have never encountered in text.

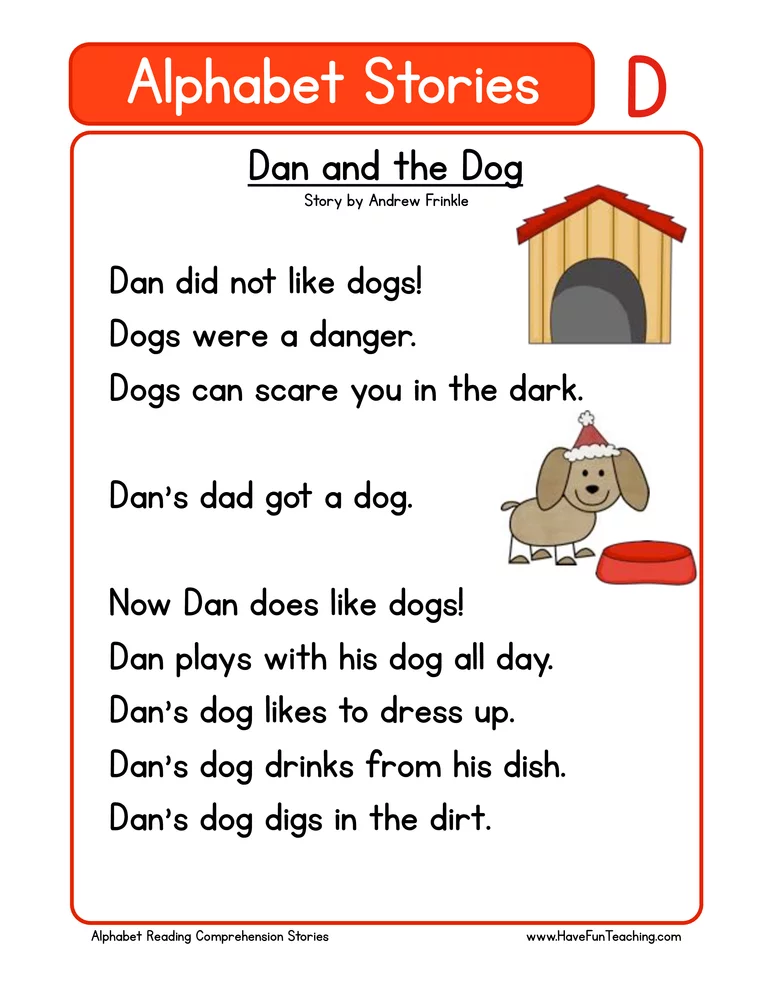

Have Students Begin Reading Texts That Contain A High Percentage Of Decodable Words

Early in learning to read, students can begin reading simple books that contain words they can read on their own using the rules of the alphabetic principle. These decodable texts have a high percentage of words that follow common alphabetic principle rules. Students can practice reading these books to build their reading fluency, which helps them focus their attention on understanding the meaning of the text.

Many common words such as “was,” “said” and “of” are irregular words—i.e., they do not follow common alphabetic principle rules. The most common irregular words should be taught early in reading development so that students will be able to read more expanded and interesting texts that are otherwise highly decodable.

The most common irregular words should be taught early in reading development so that students will be able to read more expanded and interesting texts that are otherwise highly decodable.

Infographics

Suggested Citation

Baker, S.K., Santiago, R.T., Masser, J., Nelson, N.J., & Turtura, J. (2018). The Alphabetic Principle: From Phonological Awareness to Reading Words. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Office of Special Education Programs, National Center on Improving Literacy. Retrieved from http://improvingliteracy.org.

References

Carnine, D., Silbert, J., & Kame’enui, E. J. (1997). Direct instruction reading. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Ehri, L. C. (1991). Development of the ability to read words. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 2), 383–417. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Harn, B., Simmons, D. C., & Kame’enui, E. J. (2003). Institute on Beginning Reading II: Enhancing alphabetic principle instruction in core reading instruction [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://oregonreadingfirst.uoregon.edu/downloads/instruction/big_five/enh...

Liberman, I. Y., & Liberman, A. M. (1990). Whole language vs. code emphasis: Underlying assumptions and their implications for reading instruction. Annals of Dyslexia, 40(1), 51–76. doi:10.1007/bf02648140

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction No. 00-4769). Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Retrieved from http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/nrp/smallbook.htm

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360–407. doi:10.1598/rrq.21.4.1

doi:10.1598/rrq.21.4.1

Wagner, R. K., & Torgesen, J. K. (1987). The nature of phonological processing and its causal role in the acquisition of reading skills. Psychological Bulletin, 101(2), 192–212. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.101.2.192

Related Resources

Enhancing the Core: Alphabetic Principle

Oregon Reading First Center

Read presentation slides summarizing ways to enhance alphabetic principle instruction in core reading contexts.

Topic: Phonics

Reading Basics Webinar

Michigan Alliance for Families

This 50-minute webinar overviews the five big ideas of reading, discusses tips for supporting your child's literacy development at home, and explains how schools assess and monitor your child's progress.

Topic: Beginning Reading, Assessments

Foundational Skills Mini-Course: Module 1: Nuts and Bolts

Achieve the Core

Watch this introductory video to a seven part series on promoting foundational literacy skills in accordance with Common Core State Standards.

Topic: Beginning Reading

Alphabetic Principle: Concepts and Research

| Print this page. |

Concepts and Research

- What is the Alphabetic Principle?

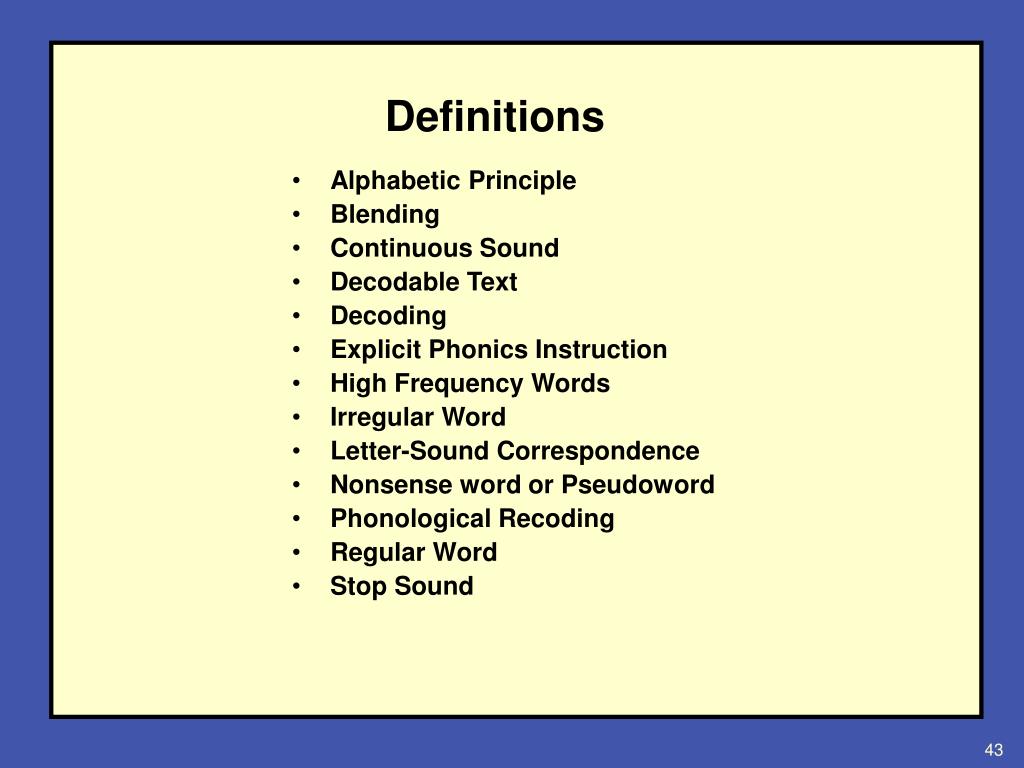

- Definitions of key Alphabetic Principle terminology

- Examples of Alphabetic Principle skills

- Alphabetic Principle Research

What is the Alphabetic Principle?

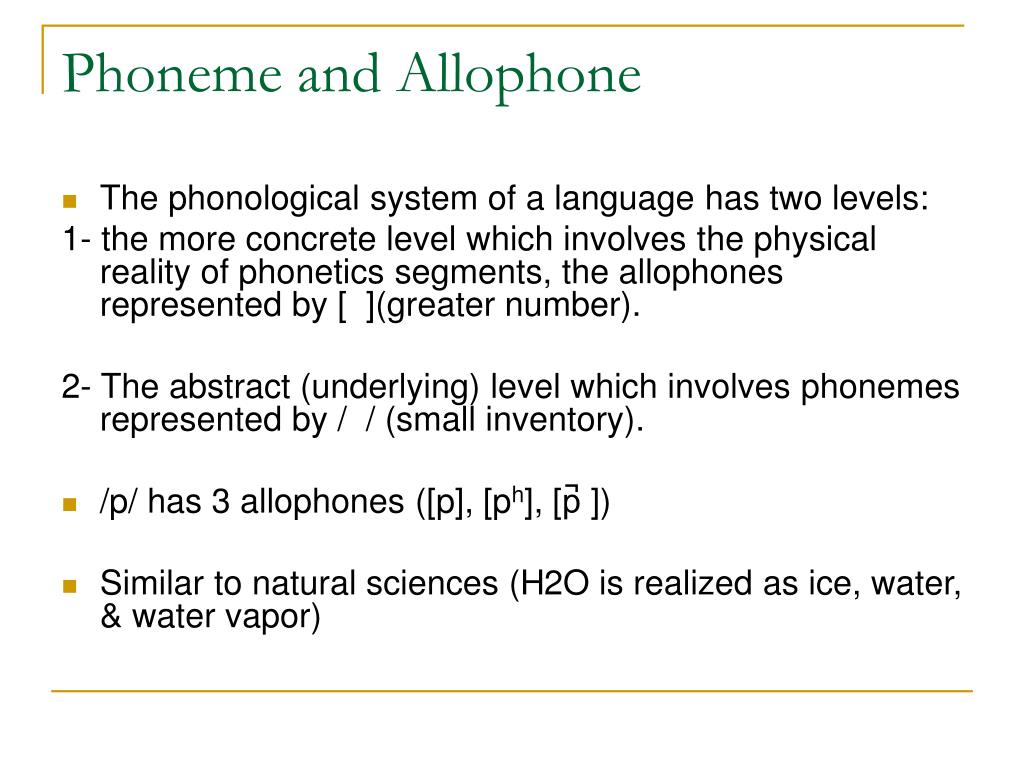

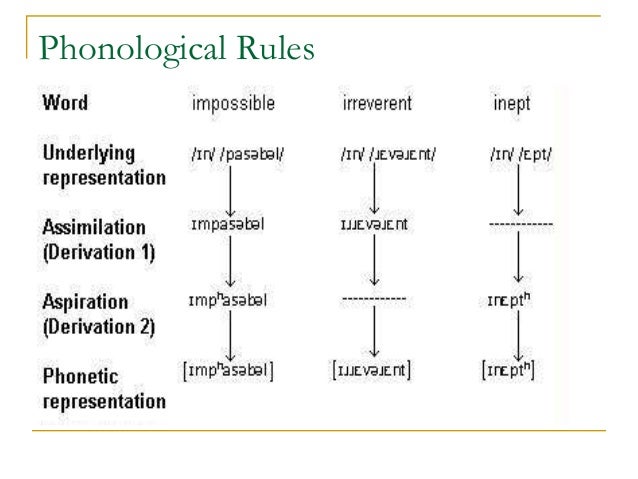

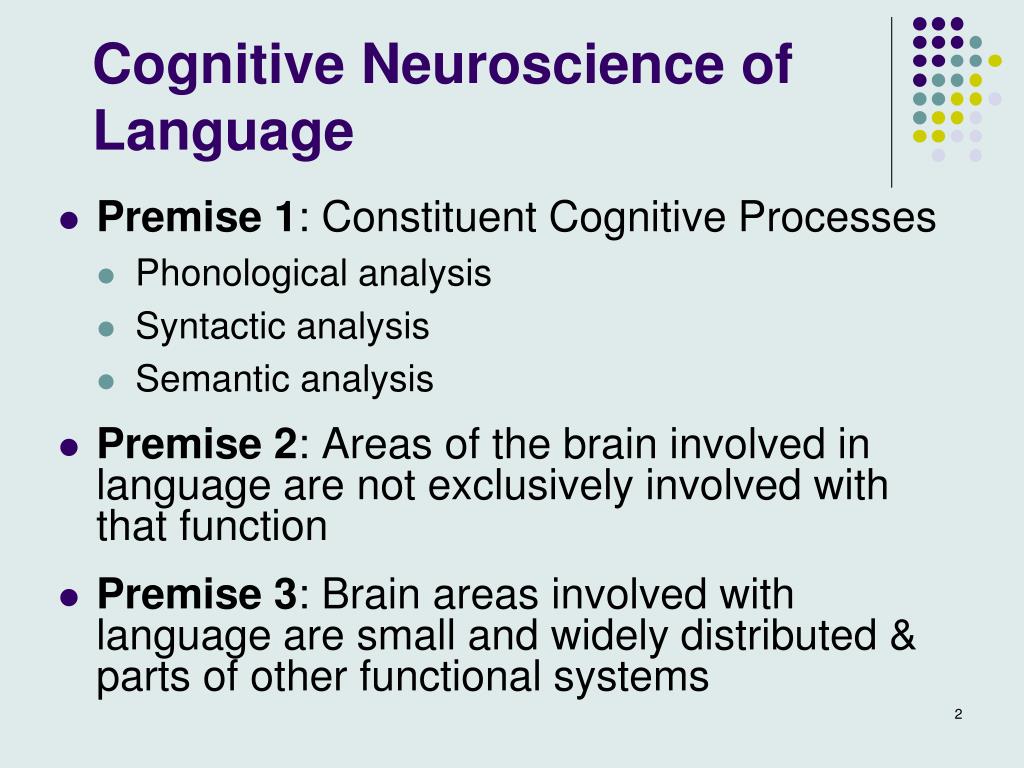

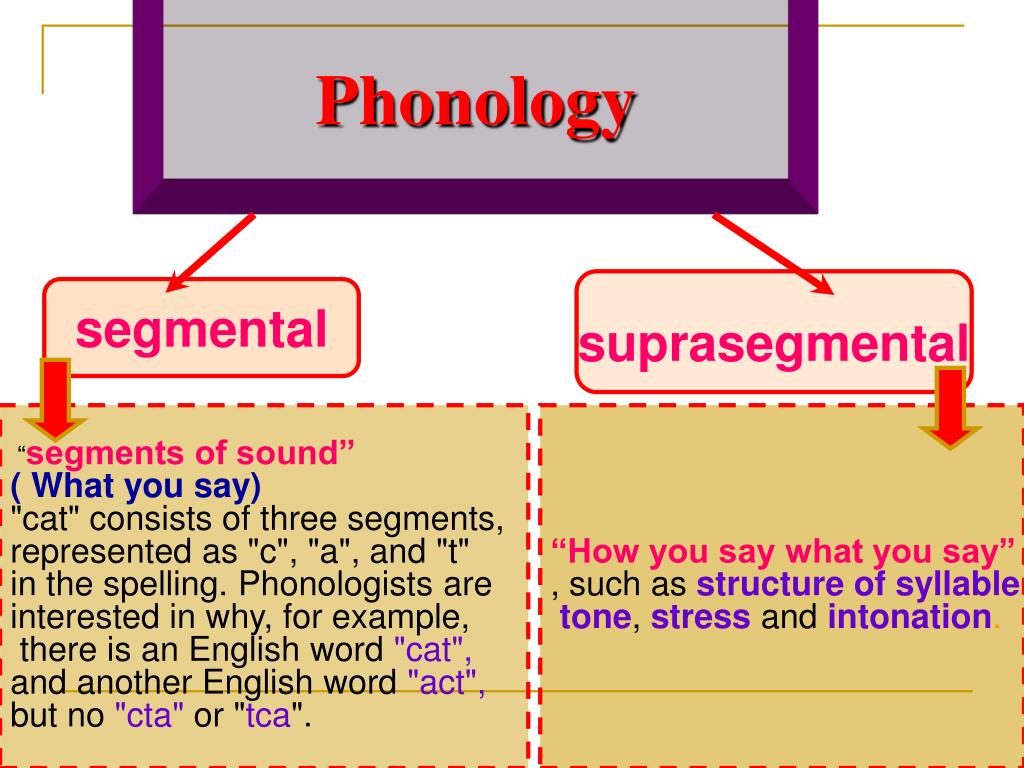

The alphabetic principle is composed of two parts:

- Alphabetic Understanding: Words are composed of letters that represent sounds.

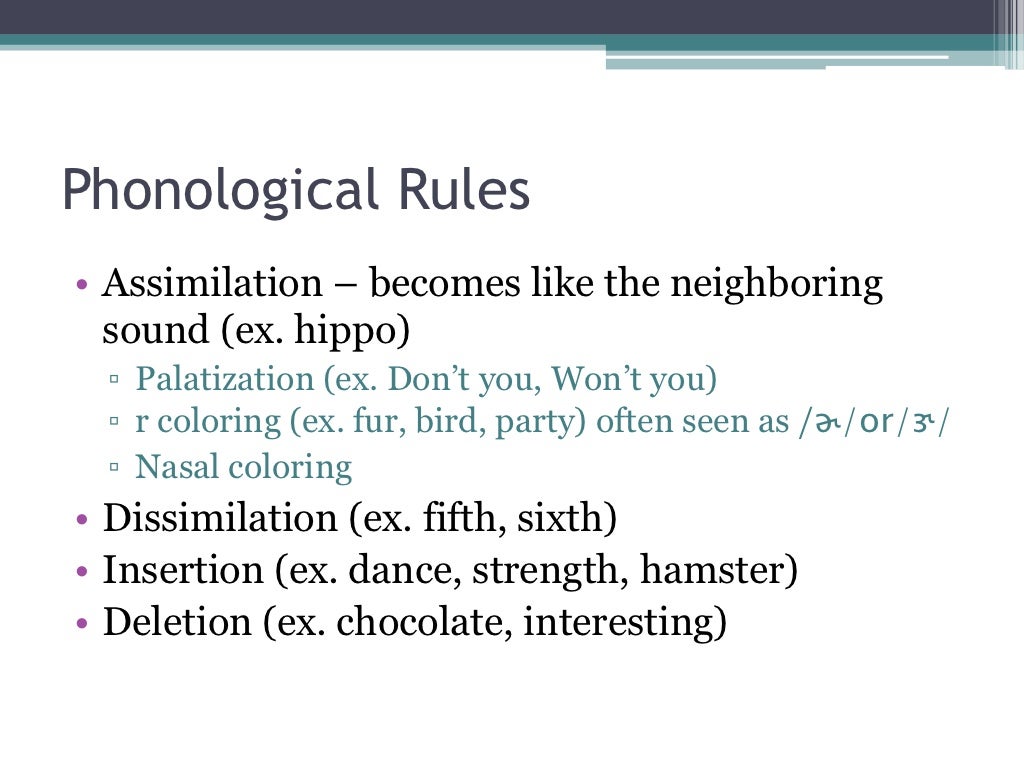

- Phonological Recoding: Using systematic relationships between letters and phonemes (letter-sound correspondence) to retrieve the pronunciation of an unknown printed string or to spell words. Phonological recoding consists of:

- Regular Word Reading

- Irregular Word Reading

- Advanced Word Analysis

Regular Word Reading

A regular word is a word in which all the letters represent their most common sounds. Regular words are words that can be decoded (phonologically recoded).

Regular words are words that can be decoded (phonologically recoded).

Because our language is alphabetic, decoding is an essential and primary means of recognizing words. There are simply too many words in the English language to rely on memorization as a primary word identification strategy (Bay Area Reading Task Force, 1997, see References).

Beginning decoding ("phonological recoding") is the ability to:

- read from left to right, simple, unfamiliar regular words.

- generate the sounds for all letters.

- blend sounds into recognizable words.

Beginning spelling is the ability to:

- translate speech to print using phonemic awareness and knowledge of letter-sounds.

Progression of Regular Word Reading

| Sounding Out (saying each individual sound out loud) | Saying the Whole Word (saying each individual sound and pronouncing the whole word) | Sight Word Reading (sounding out the word in your head, if necessary, and saying the whole word) | Automatic Word Reading (reading the word without sounding it out) |

Simple Regular Words - Listed According to Difficulty

| Word Type | Reason for Relative Ease/Difficulty | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| VC and CVC words that begin with continuous sounds | Words begin with a continuous sound | it, fan |

| VCC and CVCC words that begin with a continuous sound | Words are longer and end with a consonant blend | lamp, ask |

| CVC words that begin with a stop sound | Words begin with a stop sound | cup, tin |

| CVCC words that begin with a stop sound | Words begin with a stop sound and end with a consonant blend | dust, hand |

| CCVC | Words begin with a consonant blend | crib, blend, snap, flat |

| CCVCC, CCCVC, and CCCVCC | Words are longer | clamp, spent, scrap, scrimp |

Irregular Word Reading

Although decoding is a highly reliable strategy for a majority of words, some irregular words in the English language do not conform to word-analysis instruction (e. g., the, was, night). Those words are referred to as irregular words.

g., the, was, night). Those words are referred to as irregular words.

Irregular Word: A word that cannot be decoded because either (a) the sounds of the letters are unique to that word or a few words, or (b) the student has not yet learned the letter-sound correspondences in the word (Carnine, Silbert & Kame'enui, 1997; see References).

Texas Center for Reading and Language Arts, 1998; see References

- In beginning reading there will be passages that contain words that are "decodable" yet the letter sound correspondences in those words may not yet be familiar to students. In this case, we also teach these words as irregular words.

- To strengthen students' reliance on the decoding strategy and communicate the utility of that strategy, we recommend not introducing irregular words until students can reliably decode words at a rate of one letter-sound per second. At this point, irregular words may be introduced, but on a limited scale.

- The key to irregular word recognition is not how to teach them. The teaching procedure is simple. The critical design considerations are how many to introduce and how many to review.

Advanced Word Analysis

Advanced word analysis involves being skilled at phonological processing (recognizing and producing the speech sounds in words) and having an awareness of letter-sound correspondences in words.

Advanced word analysis skills include:

- Knowledge of common letter combinations and the sounds they make

- Identification of VCe pattern words and their derivatives

- Knolwedge of prefixes, suffixes, and roots, and how to use them to "chunk" word parts within a larger word to gain access to meaning.

Knowledge of advanced word analysis skills is essential if students are to progress in their knowledge of the alphabetic writing system and gain the ability to read fluently and broadly.

Texas Center for Reading and Language Arts, 1998; see References

Go to top of page

Definitions of key Alphabetic Principle terminology:

- Alphabetic Awareness: Knowledge of letters of the alphabet coupled with the understanding that the alphabet represents the sounds of spoken language and the correspondence of spoken sounds to written language.

- Alphabetic Understanding: Understanding that the left-to-right spellings of printed words represent their phonemes from first to last.

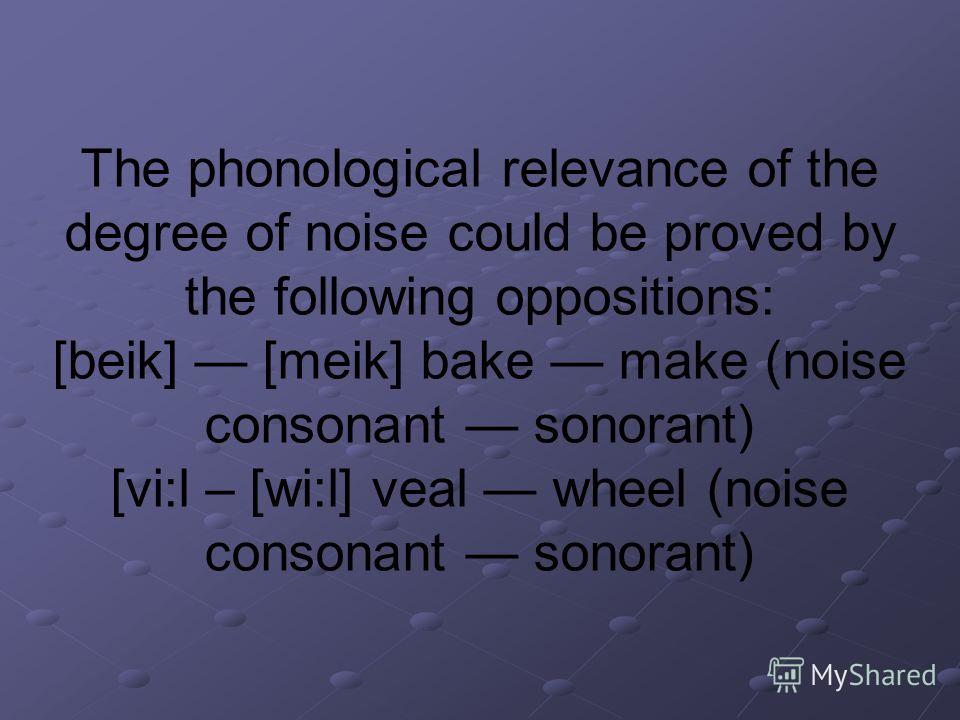

- Continuous Sound: A sound that can be prolonged (stretched out) without distortion (e.g., r, s, a, m).

- Decodable Text: Text in which the majority of words can be identified using their most common sounds. Reading materials in which a high percentage of words are linked to phonics lessons using letter-sound correspondences children have been taught. Decodable text is an intermediate step between reading words in isolation and authentic literature. These texts are used to help students focus their attention on the sound-symbol relationships they are learning. Effective decodable texts contain some sight words that allow for the development of more interesting stories.

- Decoding: The process of using letter-sound correspondences to recognize words.

- Grapheme: The individual letter or sequence of written symbols (e.

g., a, b, c) and the multiletter units (e.g., ch, sh, th) that are used to represent a single phoneme.

g., a, b, c) and the multiletter units (e.g., ch, sh, th) that are used to represent a single phoneme. - Irregular Word: A word that cannot be decoded because either (a) the sounds of the letters are unique to that word or a few words, or (b) the student has not yet learned the letter-sound correspondences in the word.

- Letter Combination: A group of consecutive letters that represents a particular sound(s) in the majority of words in which it appears.

- Letter-Sound Correspondence: A phoneme (sound) associated with a letter.

- Most Common Sound: The sound a letter most frequently makes in a short, one syllable word, (e.g., red, blast). Click here to see a list of the most common sounds of single letters.

- Nonsense or Pseudoword: A word in which the letters make their most common sounds but the word has no commonly recognized meaning (e.g., tist, lof).

- Orthography: A system of symbols for spelling.

- Phonological Recoding: Translation of letters to sounds to words to gain lexical access to the word.

- Regular Word: A word in which all the letters represent their most common sound.

- Sight Word Reading: The process of reading words at a regular rate without vocalizing the individual sounds in a word (i.e., reading words the fast way).

- Sounding Out: The process of saying each sound that represents a letter in a word without stopping between sounds.

- Stop Sound: A sound that cannot be prolonged (stretched out) without distortion. A short, plosive sound (e.g., p, t, k).

- VCe Pattern Word: Word pattern in which a single vowel is followed by a consonant, which, in turn, is followed by a final e (i.e., lake, stripe, and smile).

Go to top of page

Alphabetic Principle Skills

To develop the alphabetic principle across grades K-3, students need to learn two essential skills:

- Letter-sound correspondences: comprised initially of individual letter sounds and progresses to more complex letter combinations.

- Word reading: comprised initially of reading simple CVC words and progresses to compound words, multisyllabic words, and sight words.

Kindergarten Skills

- Letter-sound correspondence: identifies and produces the most common sound associated with individual letters.

- Decoding: blends the sounds of individual letters to read one-syllable words.

- When presented with the word fan the student will say "/fffaaannn/, fan."

- Sight word reading: Recognizes and reads words by sight (e.g., I, was, the, of).

First Grade Skills

- Letter-sound and letter-combination knowledge: produces the sounds of the most common letter sounds and combinations (e.g., th, sh, ch, ing).

- Decoding: sounds out and reads words with increasing automaticity, including words with consonant blends (e.g., mask, slip, play), letter combinations (e.g., fish, chin, bath), monosyllabic words, and common word parts (e.g., ing, all, ike).

- Sight words: Reads the most common sight words automatically (e.g., very, some, even, there).

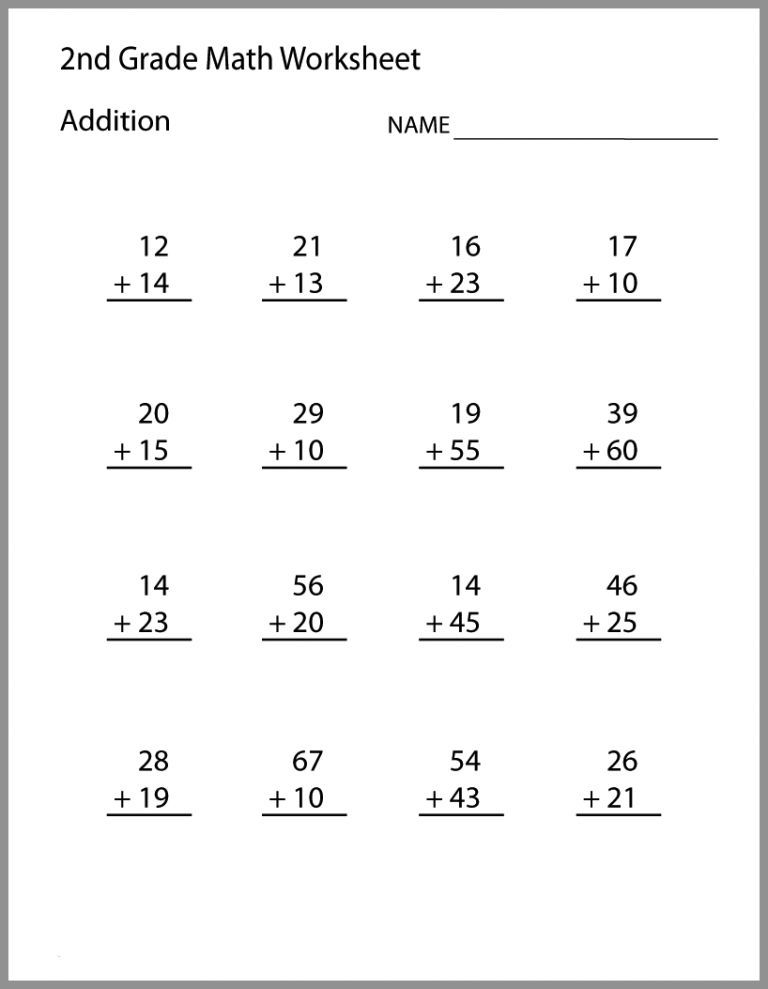

2nd and 3rd Grade Skills

- Letter-Sound Knowledge: produces the sounds that correspond to frequently used vowel diphthongs (e.g., ou, oy, ie) and digraphs (e.g., sh, th, ea).

- Decoding and Word Recognition:

- applies advanced phonic elements (digraphs and diphthongs), special vowel spellings, and word endings to read words.

- Reads compound words, contractions, possessives, and words with inflectional word endings.

- Uses word context and order to confirm or correct word reading efforts (e.g., does it make sense?).

- Reads multisyllabic words using syllabication and word structure (e.g. base/root word, prefixes, and suffixes) in word reading.

- Sight word reading: increasing number of words read accurately and automatically.

| What Teachers Should Know | What Teachers Should Be Able to Do |

|---|---|

|

|

| (modified from Moats, 1999; see References) | |

What Does the Lack of Alphabetic Understanding Look Like?

Children who lack alphabetic understanding cannot:

- Understand that words are composed of letters.

- Associate an alphabetic character (i.e., letter) with its corresponding phoneme or sound.

- Identify a word based on a sequence of letter-sound correspondences (e.g., that "mat" is made up of three letter-sound correspondences /m/ /a/ /t/).

- Blend letter-sound correspondences to identify decodable words.

- Use knowledge of letter-sound correspondences to identify words in which letters represent their most common sound.

- Identify and manipulate letter-sound correspondences within words.

- Read pseudowords (e.g., "tup", with reasonable speed).

Go to top of page

Alphabetic Principle Research Says:

Letter-sound knowledge is prerequisite to effective word identification. A primary difference between good and poor readers is the ability to use letter-sound correspondence to identify words (Juel, 1991; see References).

Students who acquire and apply the alphabetic principle early in their reading careers reap long-term benefits (Stanovich, 1986; see References).

Teaching students to phonologically recode words is a difficult, demanding, yet achievable goal with long-lasting effects (Liberman & Liberman, 1990; see References).

The combination of instruction in phonological awareness and letter-sounds appears to be the most favorable for successful early reading (Haskell, Foorman, & Swank, 1992; see References).

Good readers must have a strategy to phonologically recode words (Ehri, 1991; NRP, 2000; see References).

During the alphabetic phase, reading must have lots of practice phonologically recoding the same words to become familiar with spelling patterns (Ehri, 1991; see References).

Awareness of the relation between sounds and the alphabet can be taught (Liberman & Liberman, 1990; see References).

Because our language is alphabetic, decoding is an essential and primary means of recognizing words. There are simply too many words in the English language to rely on memorization as a primary word identification strategy (Bay Area Reading Task Force, 1996; see References).

The table below illustrates the important correlation between the ability to decode words and reading comprehension.

| (Foorman, et. al., 1997; see References) |

Go to top of page

15 Learning Disorder Terms Parents Need to Know

If your child has a speech, reading, or learning or attention disorder, you may have come across these terms on social media, forums, or at professional appointments. .

Terms such as phonological awareness, auditory processing disorder, auditory accuracy, phonological memory…

Understanding these 15 terms will help you better organize the help you need for your child:

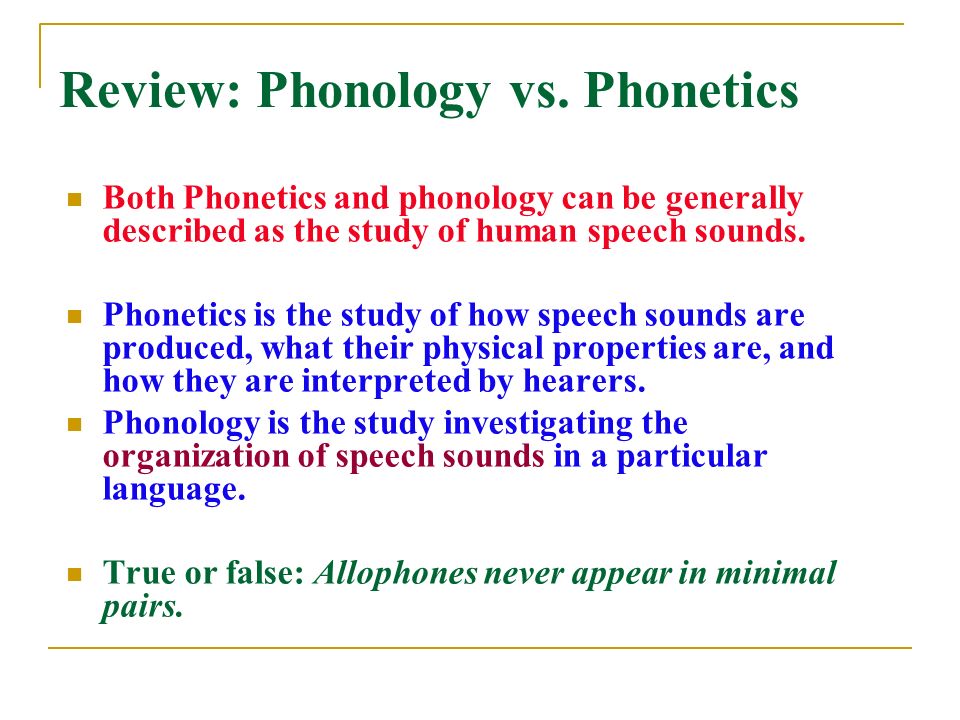

1. Phonetics

Phonetics - this term refers to the sound structure of the language: the relationship between a letter or a combination of letters (for example: chi, shu, cha, yes) and the speech sounds they represent.

Phonetics is the foundation of reading and writing skills. Thanks to phonetics, the child decodes written words in the process of reading.

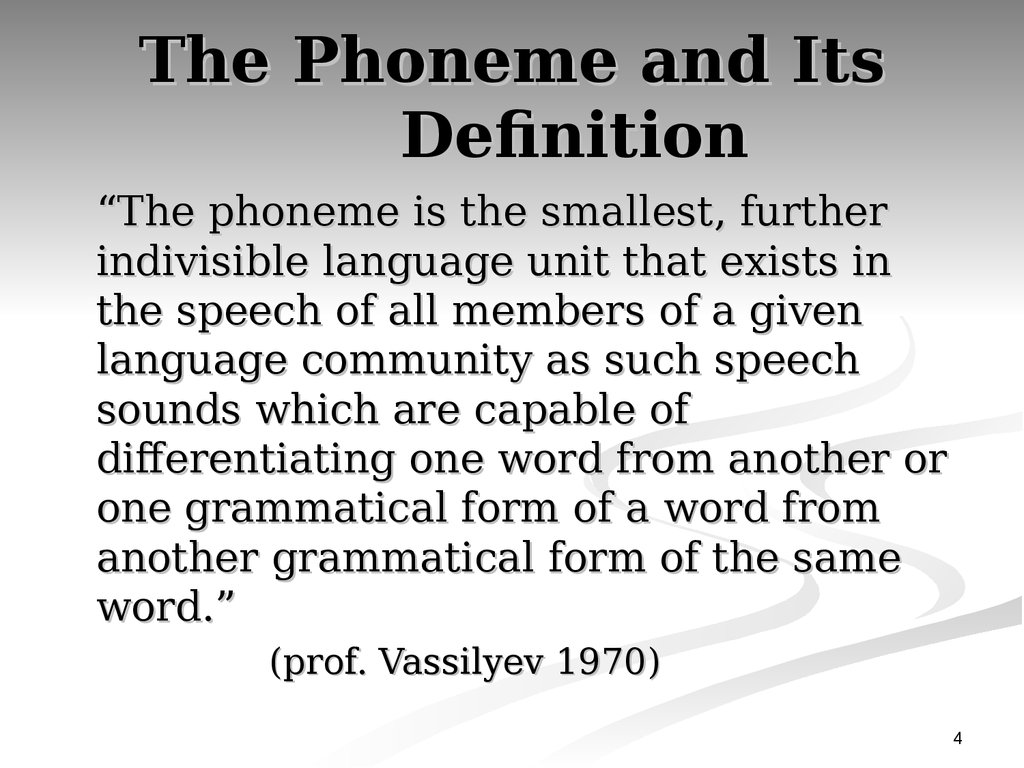

2. Phonemes

A phoneme is the sound of speech. When we speak Russian, we make 42 different speech sounds. But there are only 33 letters in the Russian alphabet. This is one of the reasons why Russian is difficult to learn.

3. Phonemic perception

Phonemic perception is the ability to perceive individual speech sounds (phonemes) in words and work with them.

Learn how to develop phonemic awareness from an early age.

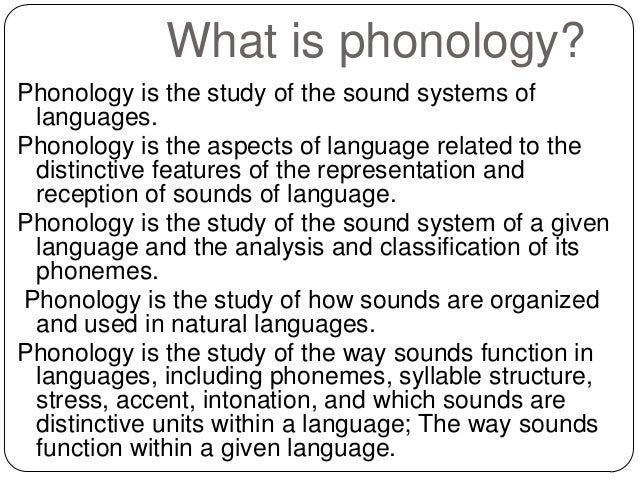

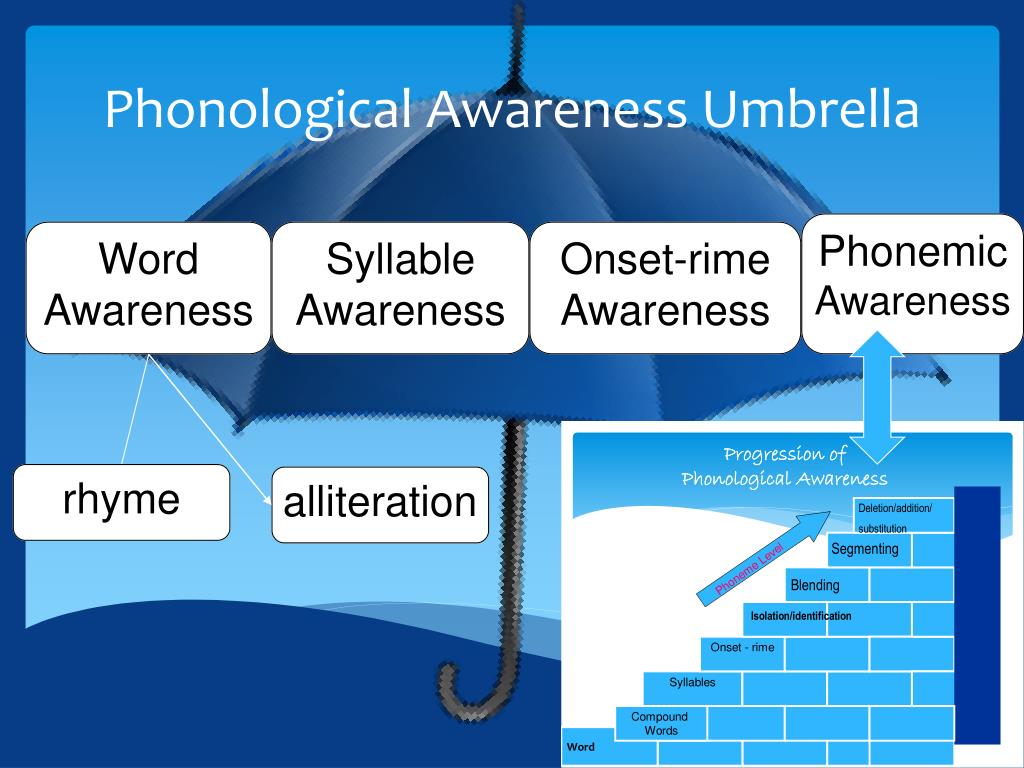

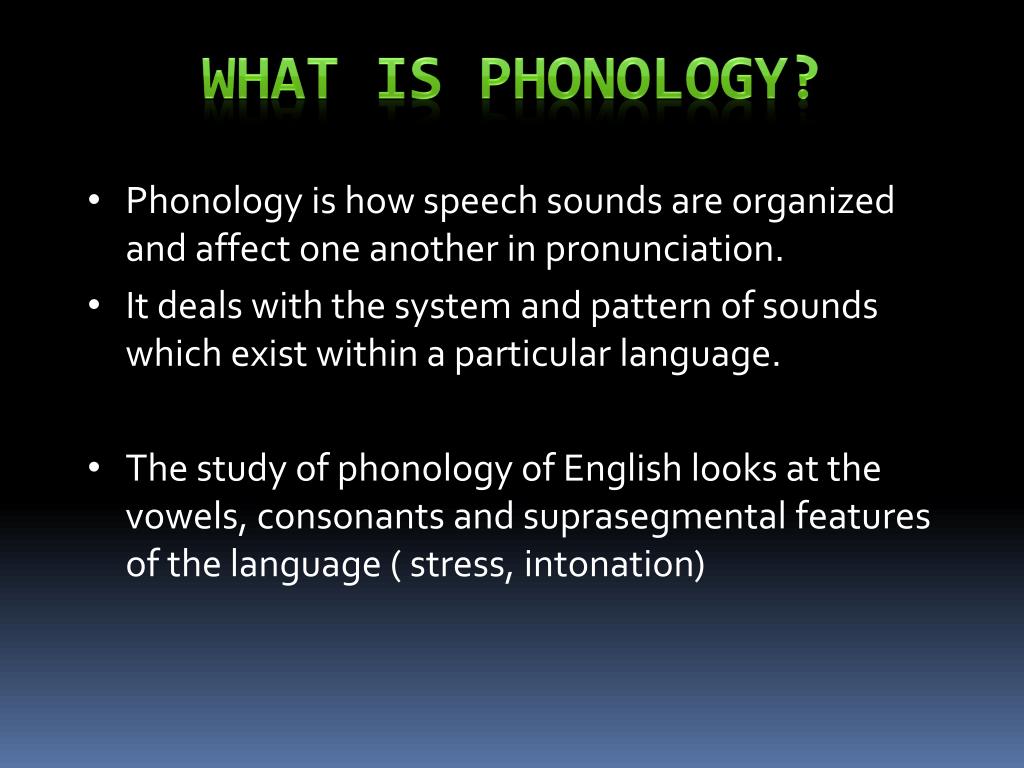

4. Phonological awareness

Phonological awareness is the awareness that words are made up of smaller parts (such as syllables and sounds).

The term includes a range of sound-related skills that a student needs to develop reading skills. As the child develops phonological awareness, he/she not only comes to understand that words are made up of small sound units (phonemes), but also learns that words can be broken down into larger sound "chunks" known as syllables. .

As the child develops phonological awareness, he/she not only comes to understand that words are made up of small sound units (phonemes), but also learns that words can be broken down into larger sound "chunks" known as syllables. .

5. Phonological accuracy

Phonological accuracy refers to the ability to correctly distinguish between individual phonemes (e.g., in similar-sounding words that begin with the same sound) or other aspects of phonology (e.g., rhyming, number of syllables).

Phonological accuracy is key to listening and reading skills. This allows the student to make a clear distinction between similar-sounding words (e.g. "heron" and "saber" or "picture" and "basket"), including morphological differences that can drastically change the word's meaning and/or grammatical function (e.g. " known" and "unknown" or "inserted" and "exposed").

The ability to quickly and accurately identify speech sounds is critical to learning the rules of phonetics and matching spoken language to text correctly.

A child with well-developed phonological accuracy will more easily develop decoding skills, understand word and sentence structure, develop vocabulary, follow instructions, and participate more actively in class work.

Well developed phonological precision helps in:

-

Understanding and following verbal instructions

-

Listening skills

-

Development of reading skills

-

Learning the rules of phonetics

6. Phonological fluency

Phonological fluency is the understanding that words are made up of different sounds and the ability to quickly and accurately identify and manipulate these sounds.

Phonological fluency is critical to learning to read. This allows the student to memorize sequences of sounds and manipulate them quickly and accurately. This makes it easier to both write words and decode them. The more effectively the reader is able to decode, the more of his cognitive resources (mental abilities) he can focus on understanding the text.

A student with good phonological fluency will also find it easier to learn new words while reading. When confronted with a new word, a student who can accurately pronounce the word is more likely to recognize and understand its meaning.

Well-developed phonological fluency helps in:

-

Learning the rules of phonetics

-

Development of reading skills

-

Development of writing skills

7. Phonological memory

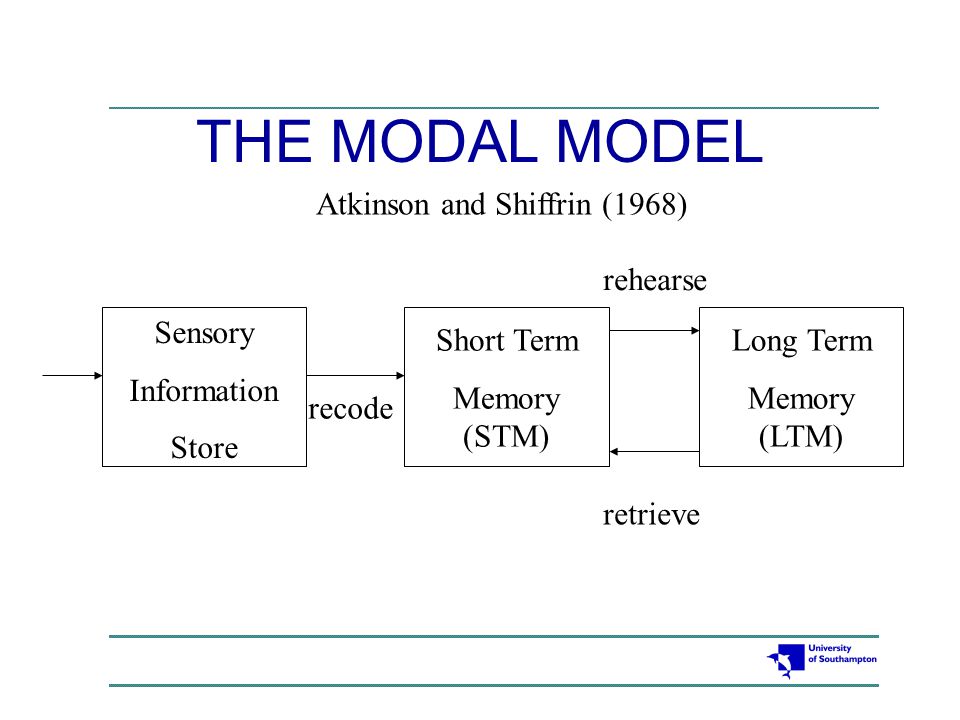

Phonological memory is the ability to retain speech sounds in memory. This is essential for spoken language and tasks such as comparing phonemes and making connections between phonemes and letters. It also helps with listening and reading understanding of sentences, as it allows you to remember the sequence of words in order.

Phonological memory plays a key role in the development of oral and written language skills. This allows the student to:

-

Memorize and manipulate sound sequences

-

Associate spoken words with written ones

-

Memorize new words by determining their meanings

-

Remember the beginning of a sentence by listening to it to the end.

The ability to remember speech sounds is important for the correct understanding of sentences when changing the order of words in a sentence changes its meaning (for example, "The monkey bites the boy" and "The boy bites the monkey").

Accurate memory of word order also contributes to building accurate ideas about sentence structure and acquiring knowledge of syntax.

A student with a well-developed phonological memory develops phonemic perception and decoding skills more easily, knowledge of vocabulary and sentence structure is formed. Such a student follows instructions better and takes a more active part in class work with presentations, etc.

Such a student follows instructions better and takes a more active part in class work with presentations, etc.

8. Auditory Processing / Auditory Perception

Auditory processing refers to what the brain does with the audio information it "hears". This includes various skills such as identifying and locating sounds, listening to background noise, and processing what is heard when the sound is fuzzy.

When a student manipulates the auditory information he has heard, but it doesn't sound right, this is called an auditory processing disorder (or auditory perception disorder).

This can happen if the child has difficulty understanding speech in background noise or has difficulty identifying where the sound is coming from. Or it could be a problem in distinguishing speech sounds that sound similar.

Find out 5 common hearing loss (HAI) myths!

9. Sequencing of audio information

Sequencing of audio information refers to the ability to identify and remember the order in which a series of sounds were presented. This is very important for matching sound sequences to letter sequences in decoding and writing.

This is very important for matching sound sequences to letter sequences in decoding and writing.

Organizing audio information is critical to developing speaking and writing skills. The ability to identify and remember the order of sounds in words is important for recognizing subtle differences between words (such as "pot" and "top") and for developing phonemic perception and decoding skills.

A student who has a well-developed ordering of sound information understands and absorbs information better, develops better oral and written speech skills and concentrates attention. Such a student becomes an expert reader and a successful student.

See also: How do weak cognitive skills affect learning?

10. Listening word comprehension

Listening word comprehension refers to the ability to accurately identify words heard based on auditory cues alone, without the aid of visual or contextual cues.

Listening comprehension of words is critical to the development of spoken language and vocabulary, and therefore essential to the development of reading and writing. This skill allows the student to accurately and efficiently identify words in speech and helps him form a correct understanding of the information presented by ear.

A student with well developed listening comprehension will find it easier to follow instructions and participate in class discussions; it is easier to answer questions, complete tasks and remember information; and it's much easier to become a proficient reader.

He will also find it easier to carry on a conversation in a noisy environment or when there are distractions.

11. Hearing accuracy

Hearing accuracy is the ability to accurately identify differences between sounds and correctly identify sound sequences.

Accuracy in listening is the foundation of speech and reading skills. This skill allows the student to quickly and accurately identify and distinguish between rapidly changing sounds, which is very important for distinguishing between phonemes (the smallest units of speech that distinguish one word from another).

A student with well-developed listening comprehension will find it much easier to follow instructions and participate in class work; it is easier to remember questions, tasks and information; and it's much easier to become a proficient reader. He will also be able to:

-

Read and write fast

-

Focus on verbally presented information

-

Maintain a conversation in a noisy environment or when there are distractions.

12. Listening comprehension

Listening comprehension is the ability to understand consecutive sentences and extract meaning from what is heard.

Listening comprehension is one of the foundations of oral and written speech. To develop more complex speech skills, a child needs to develop good listening comprehension. Well developed listening comprehension allows the student to recognize the meanings formed by combinations of words and series of sentences.

To develop more complex speech skills, a child needs to develop good listening comprehension. Well developed listening comprehension allows the student to recognize the meanings formed by combinations of words and series of sentences.

A student with good listening comprehension will find it much easier to respond to assignments and class discussions; it will be easier to answer questions and remember information; and it is easier to become a proficient reader and a successful learner. He will also be able to do well:

-

Focus on oral information

-

Making sense of history

-

Correctly follow verbal instructions

-

Correctly understand and answer questions

MOSCOW SCHOOL OF PHONOLOGY • Big Russian Encyclopedia

MOSCOW SCHOOL OF PHONOLOGY (MPS), one of the main directions in Russian phonology, based, along with the Leningrad (Petersburg) phonological school [L(P)FSh] and phonological theory of the Prague Linguistic School , on the ideas of J. A. Baudouin de Courtenay on the essence of the phoneme. The IDF originated in con. 1920s Its founders are R. I. Avanesov, P. S. Kuznetsov, A. A. Reformatsky, V. N. Sidorov, their like-minded people are A. M. Sukhotin, I. S. Ilyinskaya, G. O. Vinokur, A. I. Zaretsky and others. The formation of the IMF was also influenced by phonological. the theory of N.F. Yakovlev, who also continued the tradition of Baudouin de Courtenay. Generalization, deepening and development of the IPF theory in the form of a holistic concept was carried out by M.V. Panov, who gave a comprehensive description of the phonetic. level (tier) Rus. language, introduced the concept of the phoneme paradigm (the totality of all the sounds embodying it).

A. Baudouin de Courtenay on the essence of the phoneme. The IDF originated in con. 1920s Its founders are R. I. Avanesov, P. S. Kuznetsov, A. A. Reformatsky, V. N. Sidorov, their like-minded people are A. M. Sukhotin, I. S. Ilyinskaya, G. O. Vinokur, A. I. Zaretsky and others. The formation of the IMF was also influenced by phonological. the theory of N.F. Yakovlev, who also continued the tradition of Baudouin de Courtenay. Generalization, deepening and development of the IPF theory in the form of a holistic concept was carried out by M.V. Panov, who gave a comprehensive description of the phonetic. level (tier) Rus. language, introduced the concept of the phoneme paradigm (the totality of all the sounds embodying it).

The basis of the IPF theory is the doctrine of the phoneme. The most important provision is the need for consistent application of the morphemic criterion in determining the phonemic composition of a language. This is the main difference between the IFS and the L(P)FS and from other schools. To assign different sounds to one phoneme, it is necessary and sufficient that the sounds be in an additional distribution (distribution) depending on the phonetic. positions and occupied the same place in the same morpheme, that is, they alternated positionally. The phoneme is represented by the whole series (set, set) of positionally alternating sounds. This series may include a variety of sounds: articulatory and acoustically near and far, as well as zero sound. So, in Russian in language, the phoneme /s/ can be represented by the sounds [s] (“with father”), [s°] (“with stepfather”), [s'] (“with sister”), [s'°] (“with aunt ”), [s] (“with my brother”), [s '] (“with my uncle”), [w °] (“with my brother-in-law”), [g] (“with my wife”), [w '] ( “with a child”), zero sound (“with generous”), etc.

To assign different sounds to one phoneme, it is necessary and sufficient that the sounds be in an additional distribution (distribution) depending on the phonetic. positions and occupied the same place in the same morpheme, that is, they alternated positionally. The phoneme is represented by the whole series (set, set) of positionally alternating sounds. This series may include a variety of sounds: articulatory and acoustically near and far, as well as zero sound. So, in Russian in language, the phoneme /s/ can be represented by the sounds [s] (“with father”), [s°] (“with stepfather”), [s'] (“with sister”), [s'°] (“with aunt ”), [s] (“with my brother”), [s '] (“with my uncle”), [w °] (“with my brother-in-law”), [g] (“with my wife”), [w '] ( “with a child”), zero sound (“with generous”), etc.

IMF developed a detailed theory of positions - the conditions for the use and implementation of phonemes in speech. Positional alternations are associated with phonetic. or morphological. positions. Sounds due to phonetic. positions and alternating in the same morphemes represent a phoneme. Phonemes due to morphological. positions and alternating in the same morphemes form a morphoneme (see Morphonology).

positions. Sounds due to phonetic. positions and alternating in the same morphemes represent a phoneme. Phonemes due to morphological. positions and alternating in the same morphemes form a morphoneme (see Morphonology).

IMF put forward the provision on parallel and intersecting rows of positionally alternating sounds. Parallel rows do not have common members, while intersecting rows have - in phoneme neutralization positions. The ratio of phonemes represented by non-intersecting sets of sounds and phonemes represented by intersecting sets that have a part in common with other phonemes is different in different languages.

IFS introduced the concept of hyperphoneme - a special case of incomplete implementation in the sep. morphemes of the entire range of positionally alternating sounds that embody the phoneme. It is understood as a functional unit, represented by otd. a sound or a series of positionally alternating sounds belonging to the common part of neutralized phonemes, irreducible in these morphemes uniquely to one of these phonemes. So, the first vowel of the root dog-/dog- (“dog”, “dog”, “dog breeder”, etc.) is never stressed, but is realized accordingly by sounds [a ə ], [ə]. These positionally alternating sounds can only be representatives of the phonemes /o/ and /a/, but which of them is impossible to decide here. The hyperphoneme /o ∣ a/ appears in this root. The concept of a superphoneme is also introduced - phonological. unit, which is formed by phonemes alternating in the same morphemes, depending on the phonetic. positions. So, in the reflexive postfix -sya / -s in all verb forms (except for participles that are characteristic of written speech and uncharacteristic of oral speech), the presence and absence of a vowel phoneme depends solely on the phoneme preceding this postfix: after the consonants, a variant with a vowel phoneme appears (" to be afraid”, “we are afraid”, “were afraid”, “be afraid”), after vowels - without it (“I am afraid”, “are afraid”, “were afraid”, “be afraid”, “afraid”, etc.

So, the first vowel of the root dog-/dog- (“dog”, “dog”, “dog breeder”, etc.) is never stressed, but is realized accordingly by sounds [a ə ], [ə]. These positionally alternating sounds can only be representatives of the phonemes /o/ and /a/, but which of them is impossible to decide here. The hyperphoneme /o ∣ a/ appears in this root. The concept of a superphoneme is also introduced - phonological. unit, which is formed by phonemes alternating in the same morphemes, depending on the phonetic. positions. So, in the reflexive postfix -sya / -s in all verb forms (except for participles that are characteristic of written speech and uncharacteristic of oral speech), the presence and absence of a vowel phoneme depends solely on the phoneme preceding this postfix: after the consonants, a variant with a vowel phoneme appears (" to be afraid”, “we are afraid”, “were afraid”, “be afraid”), after vowels - without it (“I am afraid”, “are afraid”, “were afraid”, “be afraid”, “afraid”, etc. ). The superphoneme <а∣ø> appears in this postfix.

). The superphoneme <а∣ø> appears in this postfix.

In the process of development and improvement, the IFS also uses ideas close to it, expressed by representatives of other schools. So, she participates in the development of the concepts of differential and integral features of the phoneme, previously put forward by the Prague linguistic. school.

The main provisions established in the analysis of the phoneme are also applied by the IFS when considering the supersegmental units of the language and phenomena: stress, tones, intonation, boundary signals (according to M.V. Panov, dierema; they indicate the nature of sounds on the boundaries between words and between morphemes within words), synharmonism, etc.

Construction of phonological language models, including the definition of all its phonemes and their relationships in different positions, from the point of view of the IMF, is possible only when all words, grammatical. forms and morphemes of a given language and all phonetic. phonological implementations. units. Hence the close attention of the representatives of the IPF to the sound matter of the language, including its study by the methods of instrumental phonetics.

phonological implementations. units. Hence the close attention of the representatives of the IPF to the sound matter of the language, including its study by the methods of instrumental phonetics.

The ideas of the IFS have found application primarily in the theory of writing - graphics and spelling, the creation of alphabets, practical. transcriptions and transliterations, in the historical phonetics, dialectology and linguistic geography, in teaching a non-native language. The position that positionally alternating units are modifications of the same unit of a higher level of language (tier) is increasingly used not only in phonology, but also in describing the phenomena of word formation, morphology, syntax, vocabulary, poetics, etc.

The ideas of the IPF are developed by its representatives of the second and following generations: K. V. Gorshkova (problems of historical phonetics and phonology, the history of the development of the phonological system of the Russian language in its dialect division; clarified the concept of the phoneme paradigm), Valery V. Ivanov (questions historical phonology of the Russian language, syntagmatics and paradigmatics of phonemes), L. E. Kalnyn (research in the field of Slavic phonetics and phonology), V. A. Vinogradov (questions of general, Russian and African phonology, phonological foundations of teaching phonetics non-native language; clarified the concept of hyperphoneme), L. L. Kasatkin (problems of Russian lit. and dialect phonetics, contribution to the development of the theory of phonetic and phonological positions, phonetic alternations; identified a latent period in the history of a phoneme; introduced the concepts of superphoneme, phoneme as a two-way linguistic sign), S. M. Kuzmina (correlation spelling aphia, phonetics and phonology), N.K. Pirogova (studies in the field of vocalism in Russian. lit. language of the 20th century), E. L. Barkhudarova (research in the field of consonantism of the Russian literary language of the 20th century), M. L. Kalenchuk (problems of Russian orthoepy and the development of the concept of orthoepic positions), etc.

Ivanov (questions historical phonology of the Russian language, syntagmatics and paradigmatics of phonemes), L. E. Kalnyn (research in the field of Slavic phonetics and phonology), V. A. Vinogradov (questions of general, Russian and African phonology, phonological foundations of teaching phonetics non-native language; clarified the concept of hyperphoneme), L. L. Kasatkin (problems of Russian lit. and dialect phonetics, contribution to the development of the theory of phonetic and phonological positions, phonetic alternations; identified a latent period in the history of a phoneme; introduced the concepts of superphoneme, phoneme as a two-way linguistic sign), S. M. Kuzmina (correlation spelling aphia, phonetics and phonology), N.K. Pirogova (studies in the field of vocalism in Russian. lit. language of the 20th century), E. L. Barkhudarova (research in the field of consonantism of the Russian literary language of the 20th century), M. L. Kalenchuk (problems of Russian orthoepy and the development of the concept of orthoepic positions), etc.