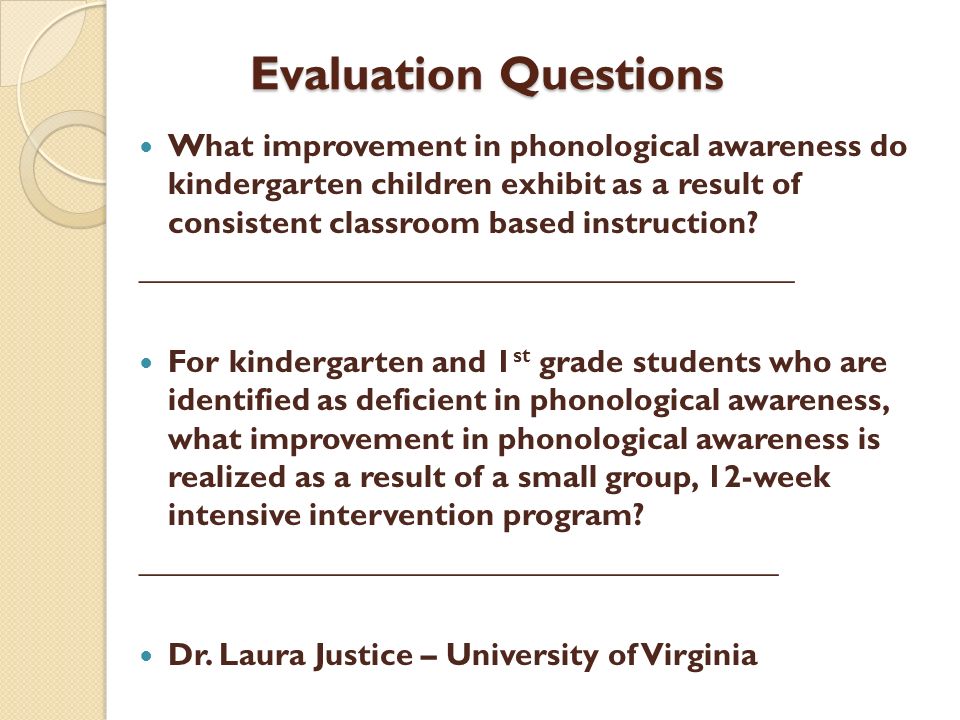

What is the importance of students developing their phonological awareness

Phonological awareness

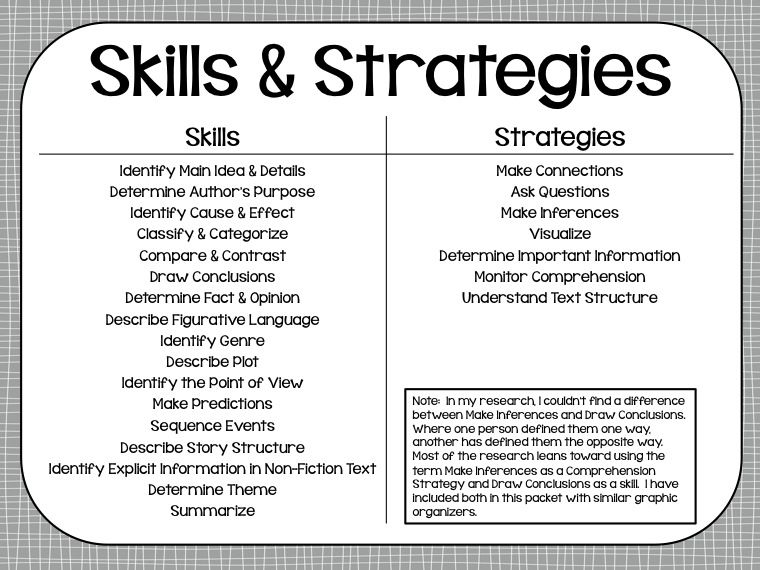

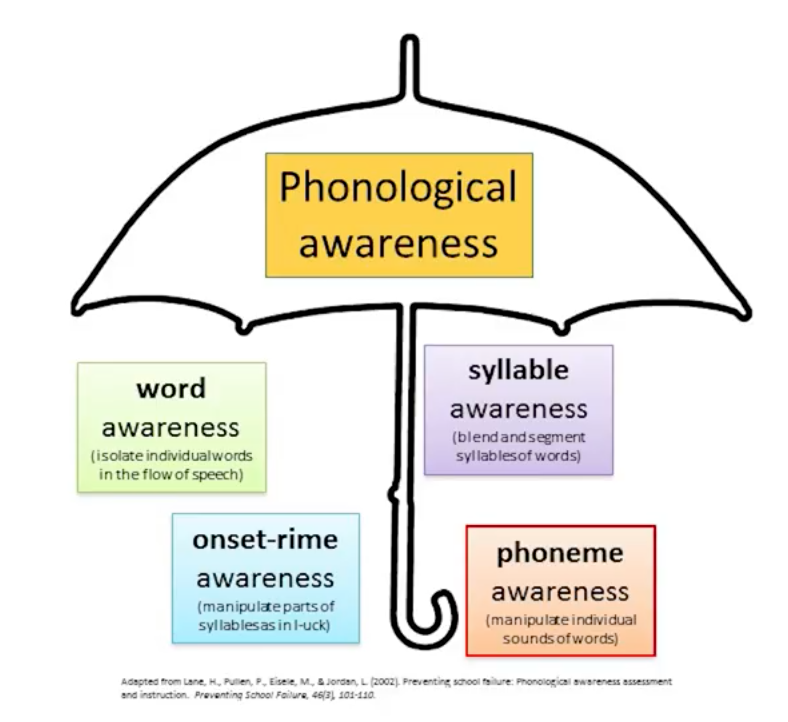

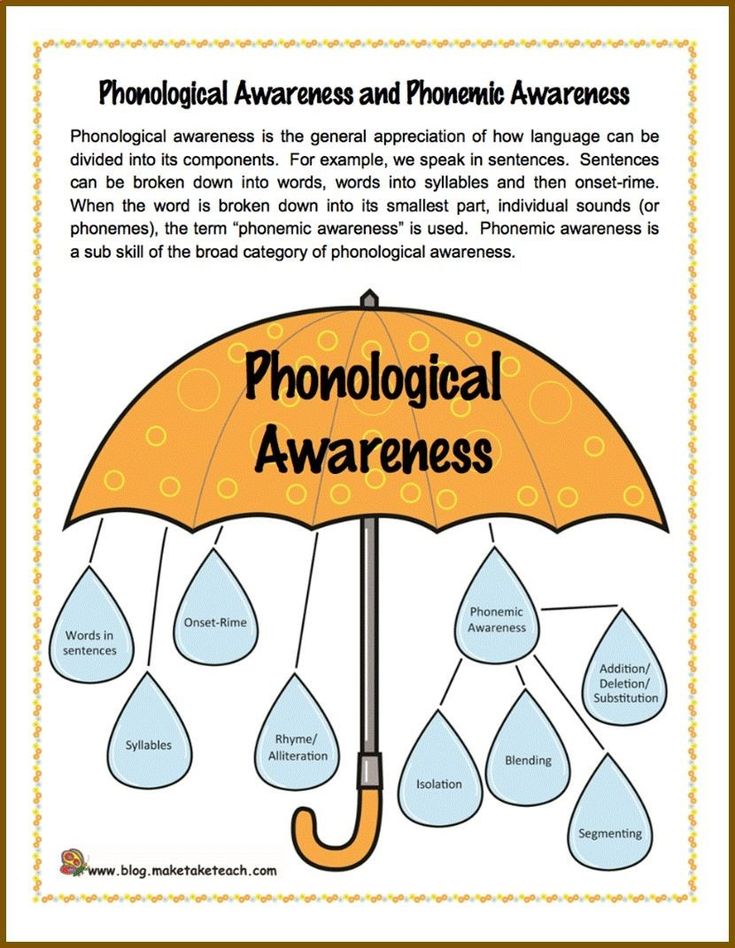

Phonological awareness is a crucial skill to develop in children. It is strongly linked to early reading and spelling success through its association with phonics. It is a focus of literacy teaching incorporating:

- recognising phonological patterns such as rhyme and alliteration

- awareness of syllables and phonemes within words, and

- hearing multiple phonemes within words.

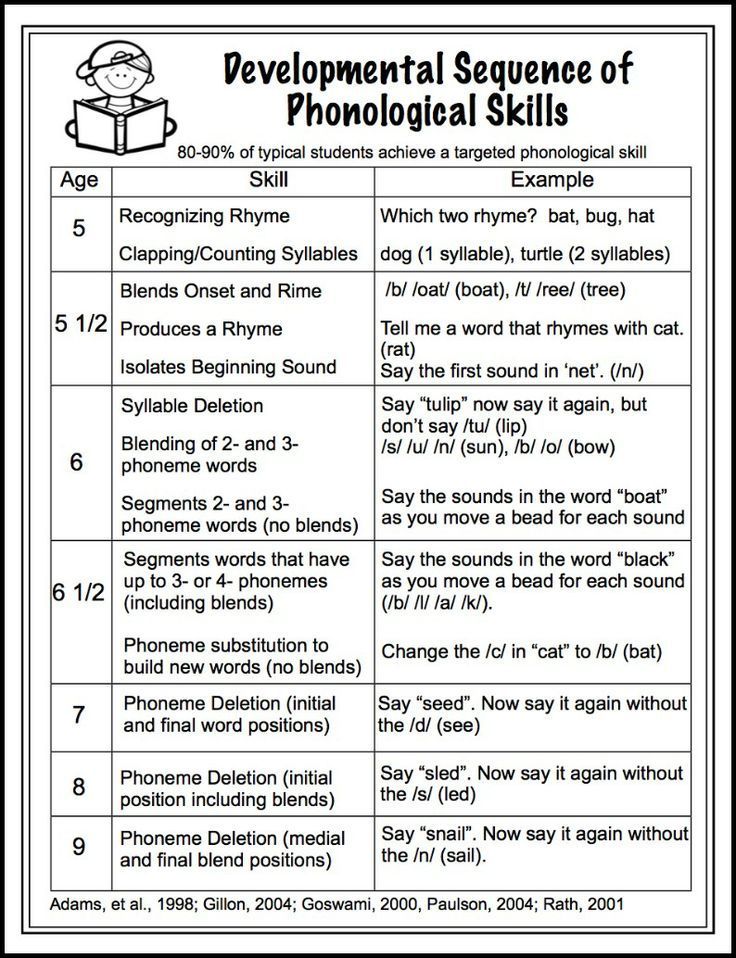

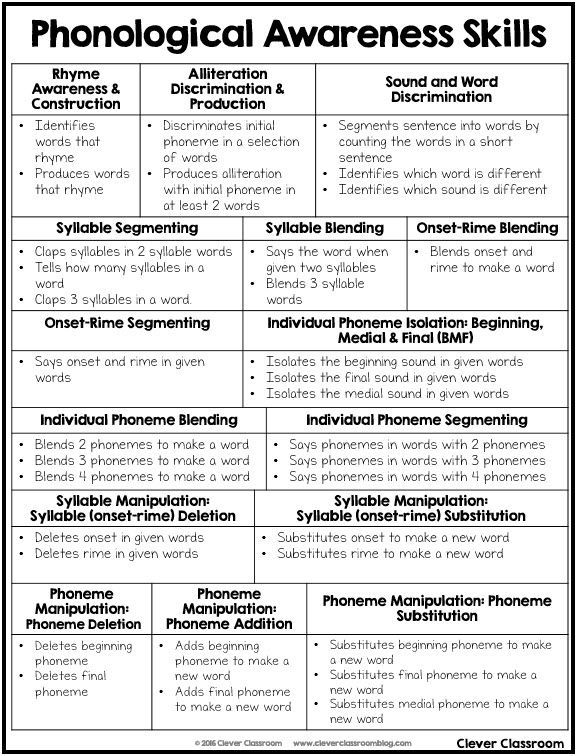

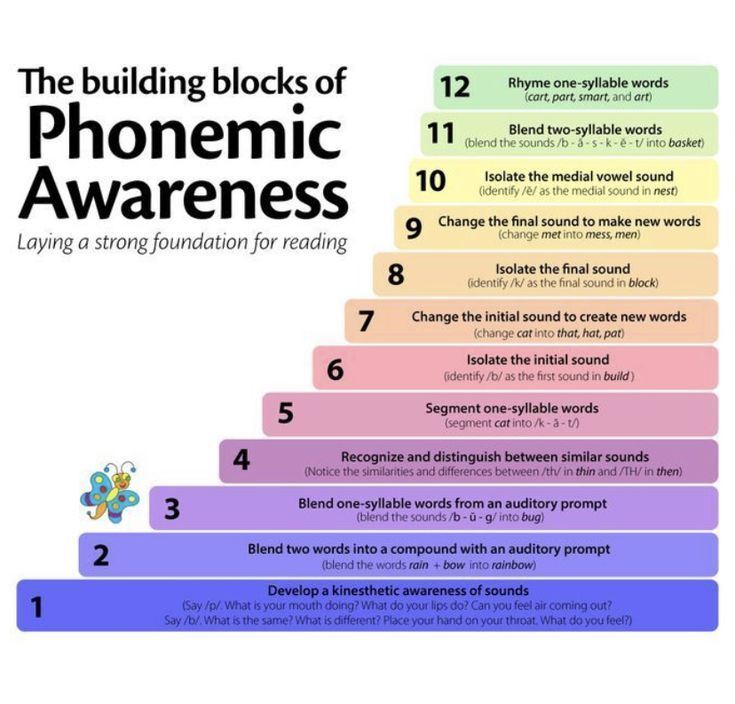

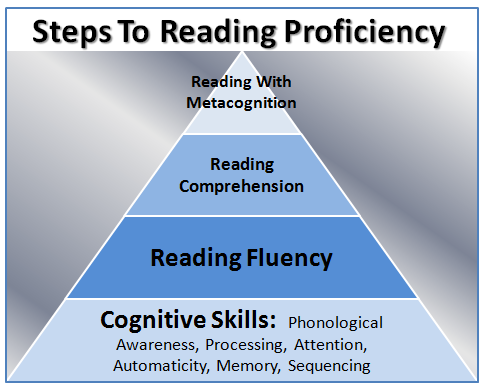

Phonological awareness skills can be conceptualised within a sequence of increasing complexity:

- Syllable Awareness (docx - 274.77kb)

- Rhyme awareness and production (docx - 400.87kb)

- Alliteration - Sorting initial and final sounds (docx - 679.3kb)

- Onset-Rime segmentation (docx - 250.94kb)

- Initial and final sound segmentation (docx - 422.36kb)

- Blending sounds into words (docx - 1.

63mb)

- Segmenting words into sounds (docx - 572.86kb)

- Deleting and manipulating sounds (docx - 4.95mb)

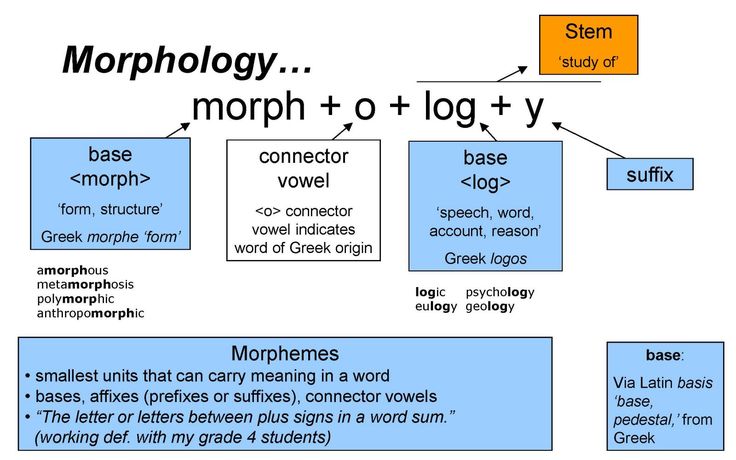

The diagram below displays this concept:

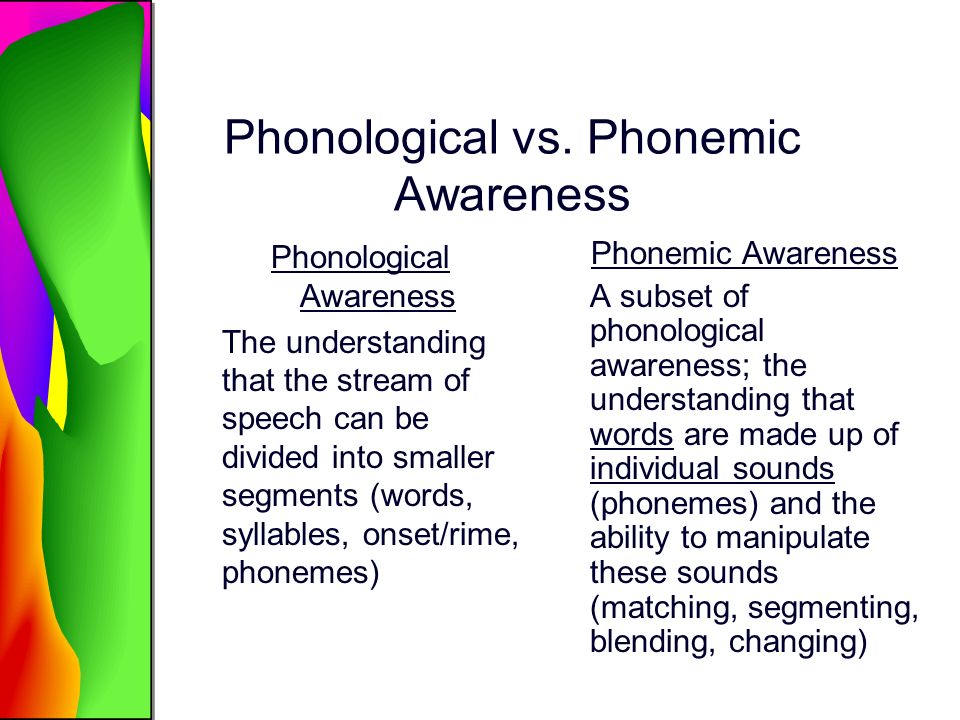

Phonological awareness consists of all the above competencies, and phonemic awareness is a critical subset of phonological awareness. Phonemic awareness includes onset-rime identification, initial and final sound segmenting, as well as blending, segmenting, and deleting/manipulating sounds (see diagram above).

While phonological awareness includes the awareness of speech sounds, syllables, and rhymes, phonics is the mapping of speech sounds (phonemes) to letters (or letter patterns, i.e. graphemes). Phonological Awareness and Phonics are therefore not the same, but these literacy focuses tend to overlap.

Phonics builds upon a foundation of phonological awareness, specifically phonemic awareness. As students learn to read and spell, they fine-tune their knowledge of the relationships between phonemes and graphemes in written language. As reading and spelling skills develop, focussing on phonemic awareness improves phonics knowledge, and focussing on phonics also improve phonemic awareness.

As reading and spelling skills develop, focussing on phonemic awareness improves phonics knowledge, and focussing on phonics also improve phonemic awareness.

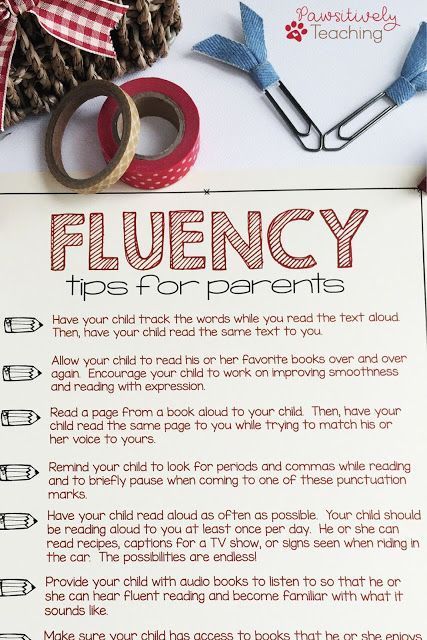

Developing strong competencies in phonological awareness is important for all students, as the awareness of the sounds in words and syllables is critical to hearing and segmenting the words students want to spell, and blending together the sounds in words that students read. Focussing on phonological awareness is recommended to form a key component of early childhood education for literacy, starting with syllable, rhyme, and initial/final sound (alliteration) awareness.

In the early years of primary school, the focus of phonological awareness includes syllable, rhyme, and alliteration awareness, but has a stronger focus on phonemic awareness, especially sound blending, segmentation, and manipulation — as these are the strongest predictors of early decoding success.

Phonological awareness is a key early competency of emergent and proficient reading, including an explicit awareness of the structure of words, syllables, onset-rime, and individual phonemes. Together with phonics, phonological awareness (in particular phonemic awareness) is an essential competency for breaking the code of written language as per the Four Resources Model for Reading and Viewing

Together with phonics, phonological awareness (in particular phonemic awareness) is an essential competency for breaking the code of written language as per the Four Resources Model for Reading and Viewing

In this video, the teacher leads a whole class lesson that focuses on rhyming words.

In this video the teacher explicitly teaches onset and rime through a mini lesson. Students make differentiated onset-rime booklets to practise the skill of onset-rime segmentation.

In this video, the teacher leads a whole class lesson that focuses on syllables.

National reports on the teaching of reading in the US, UK and Australia support the inclusion of phonological awareness in early literacy programs. Hill (2016, p.110) notes the importance of phonological awareness as ‘a precursor to decoding’ which needs to be explicitly taught (Adams, 2011).

FoundationReading

- Understand concepts about print and screen, including how books, film and simple digital texts work, and know some features of print, including directionality (Content description VCELA142)

- Recognise all upper- and lower-case letters and the most common sound that each letter represents (Content description VCELA146)

Speaking and listening

- Identify rhyming words, alliteration patterns, syllables and some sounds (phonemes) in spoken words (Content description VCELA168)

- Blend and segment onset and rime in single syllable spoken words and isolate, blend and segment phonemes in single syllable words (first consonant sound, last consonant sound, middle vowel sound) (Content description VCELA169)

- Replicate the rhythms and sound patterns in stories, rhymes, songs and poems from a range of cultures (Content description VCELT172)

Writing

- Understand that punctuation is a feature of written text different from letters and recognise how capital letters are used for names, and that capital letters and full stops signal the beginning and end of sentences (Content description VCELA156)

- Understand that sounds in English are represented by upper- and lower-case letters that can be written using learned letter formation patterns for each case (Content description VCELY162)

Reading

- Understand concepts about print and screen, including how different types of texts are organised using page numbering, tables of content, headings and titles, navigation buttons, bars and links (Content description VCELA177)

Speaking and listening

- Identify the separate phonemes in consonant blends or clusters at the beginnings and ends of syllables (Content description VCELA203)

- Manipulate phonemes by addition, deletion and substitution of initial, medial and final phonemes to generate new words (Content description VCELA204)

Writing

- Recognise that different types of punctuation, including full stops, question marks and exclamation marks, signal sentences that make statements, ask questions, express emotion or give commands (Content description VCELA190)

Speaking and listening

- Manipulate more complex sounds in spoken words through knowledge of blending and segmenting sounds, phoneme deletion and substitution (Content description VCELA238)

- Identify all Standard Australian English phonemes, including short and long vowels, separate sounds in clusters (Content description VCELA239)

Links to the Victorian Curriculum - English as an Additional Language (EAL)

Pathway A

Speaking and listening

Level A1

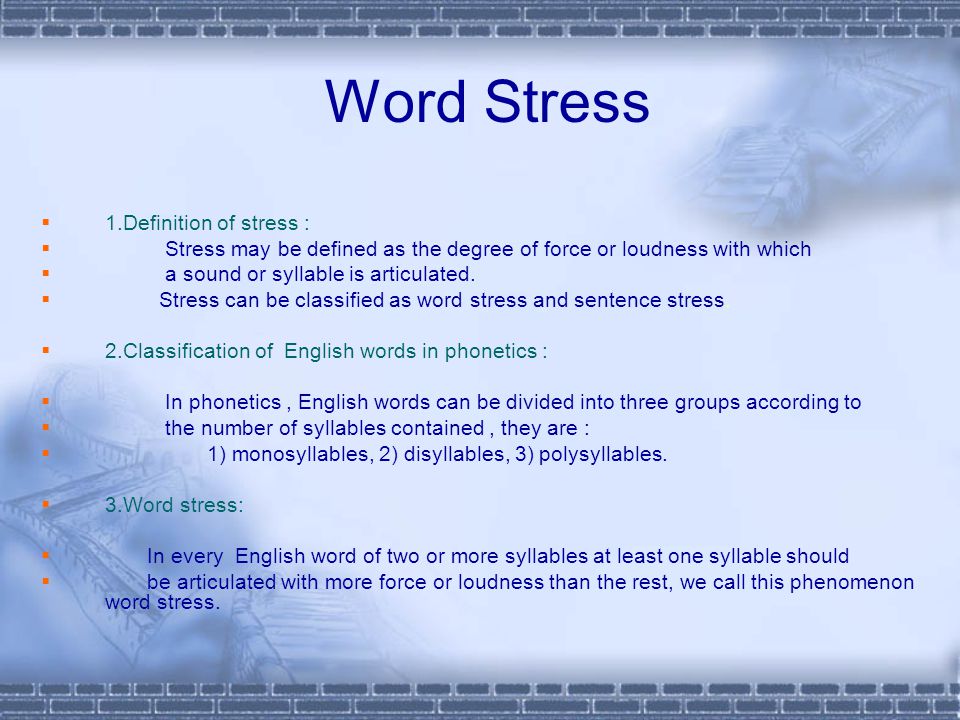

- Imitate pronunciation, stress and intonation patterns (VCEALL027)

- Use intelligible pronunciation but with many pauses and hesitations (VCEALL028)

Level A2

- Repeat or modify a sentence or phrase, modelling rhythm, intonation and pronunciation on the speech of others (VCEALL109)

- Identify and produce phonemes in blends or clusters at the beginning and end of syllables (VCEALL110)

Reading

Level A1

- Identify some sounds in words (VCEALL050)

- Recognise some common letters and letter patterns in words (VCEALL051)

Level A2

- Relate most letters of the alphabet to sounds (VCEALL131)

- Use knowledge of letters and sounds to read a new word or locate key words (VCEALL132)

Writing

Level A1

- Spell with accuracy some consonant–vowel–consonant words and common words learnt in the classroom (VCEALL080)

Level A2

- Spell with accuracy familiar words and words with common letter patterns (VCEALL159)

Pathway B

Speaking and listening

Level BL

- Use comprehensible pronunciation for familiar words

- Repeat or re-pronounce words of phrases, when prompted, if not understood (VCEALL183)

Level B1

- Use comprehensible pronunciation for a range of high-frequency words learnt in class (VCEALL262)

- Repeat or re-pronounce words of phrases, when prompted, if not understood (VCEALL263)

Level B2

- Use clear pronunciation for common words and learnt key topic words (VCEALL343)

- Self-correct and improve aspects of pronunciation that impede communication (VCEALL344)

Level B3

- Self-correct and improve aspects of pronunciation that impede communication, and focus on correction (VCEALL423)

Reading and viewing

Level BL

- Recognise the letters of the alphabet (VCEALL208)

- Attempt to self-correct (VCEALL211)

Level B1

- Identify common syllables and patterns within words (VCEALL288)

- Self-correct with guidance (VCEALL291)

Level B2

- Apply knowledge of letter–sound relationships to read new words with some support (VCEALL368)

- Self-correct pronunciation (VCEALL371)

Level B3

- Apply knowledge of letter–sound relationships to deduce the pronunciation of new words (VCEALL447)

- Self-correct a range of aspects of speech (VCEALL450)

Writing

Level BL

- Spell a number of high-frequency words accurately (VCEALL237)

Level B1

- Spell accurately common words encountered in the classroom (VCEALL318)

Level B2

- Spell frequently used words with common patterns with increased accuracy (VCEALL398)

Level B3

- Spell most words accurately, drawing on a range of strategies but with some invented spelling still evident (VCEALL477)

For example activities to develop the major phonological awareness skills, see: Examples to Promote Phonological Awareness

Adams, M. J. (2011). The relation between alphabetic basics, word recognition and reading. In S. J. Samuels & A. E. Farstrup (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (4th ed.) (pp. 4-24). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

J. (2011). The relation between alphabetic basics, word recognition and reading. In S. J. Samuels & A. E. Farstrup (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (4th ed.) (pp. 4-24). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Allington, R., Baker, M., Baumann, J., Hoffman, J., Stumpf Jongsma, K., Klein, A., Larson, D., Logan, J. & Morrow, L. (1998). Phonemic awareness and the teaching of reading: A position statement from the Board of Directors of the International Reading Association. Newark, Delaware: International Reading Association.

Hill, S. (2012). Developing early literacy: assessment and teaching (2nd ed.). South Yarra, Vic. Eleanor Curtain Publishing.

Why Phonological Awareness Is Important for Reading and Spelling

By: Louisa Moats, Carol Tolman

The phonological processor usually works unconsciously when we listen and speak. It is designed to extract the meaning of what is said, not to notice the speech sounds in the words. It is designed to do its job automatically in the service of efficient communication. But reading and spelling require a level of metalinguistic speech that is not natural or easily acquired.

It is designed to do its job automatically in the service of efficient communication. But reading and spelling require a level of metalinguistic speech that is not natural or easily acquired.

On the other hand, phonological skill is not strongly related to intelligence. Some very intelligent people have limitations of linguistic awareness, especially at the phonological level. Take heart. If you find phonological tasks challenging, you are competent in many other ways!

This fact is well proven: Phonological awareness is critical for learning to read any alphabetic writing system (Ehri, 2004; Rath, 2001; Troia, 2004). Phonological awareness is even important for reading other kinds of writing systems, such as Chinese and Japanese. There are several well-established lines of argument for the importance of phonological skills to reading and spelling.

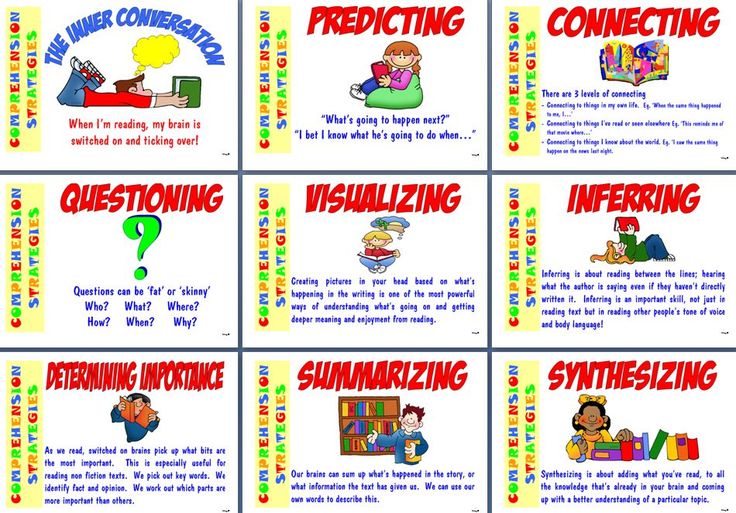

Phoneme awareness is necessary for learning and using the alphabetic code

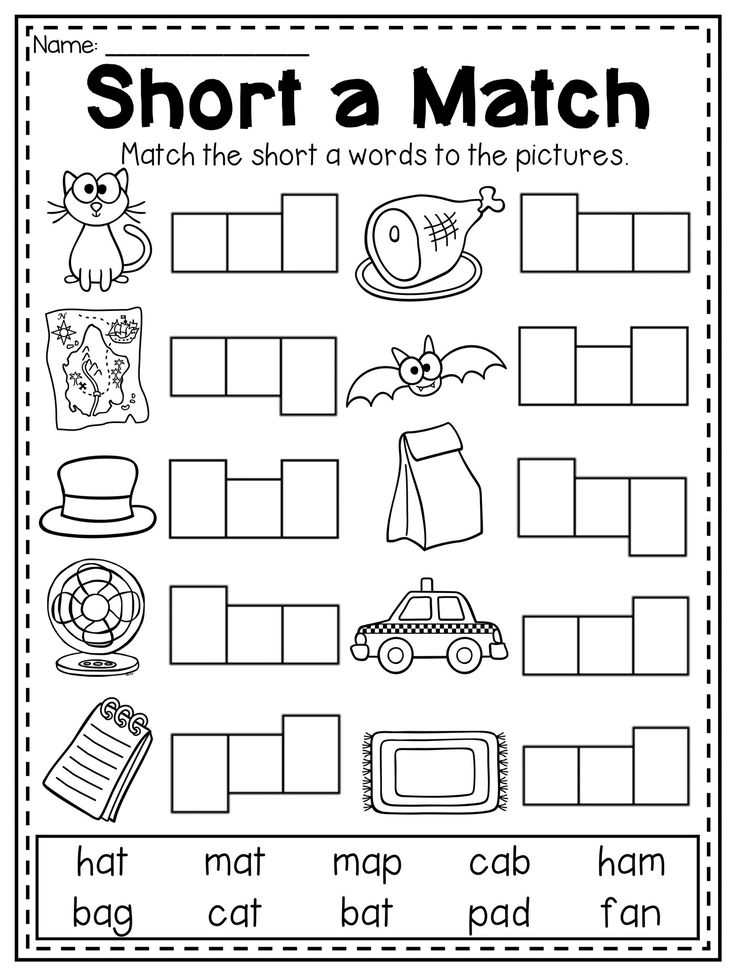

English uses an alphabetic writing system in which the letters, singly and in combination, represent single speech sounds. People who can take apart words into sounds, recognize their identity, and put them together again have the foundation skill for using the alphabetic principle (Liberman, Shankweiler, & Liberman, 1989; Troia, 2004). Without phoneme awareness, students may be mystified by the print system and how it represents the spoken word.

People who can take apart words into sounds, recognize their identity, and put them together again have the foundation skill for using the alphabetic principle (Liberman, Shankweiler, & Liberman, 1989; Troia, 2004). Without phoneme awareness, students may be mystified by the print system and how it represents the spoken word.

Students who lack phoneme awareness may not even know what is meant by the term sound. They can usually hear well and may even name the alphabet letters, but they have little or no idea what letters represent. If asked to give the first sound in the word dog, they are likely to say "Woof-woof!" Students must be able to identify /d/ in the words dog, dish, and mad and separate the phoneme from others before they can understand what the letter d represents in those words.

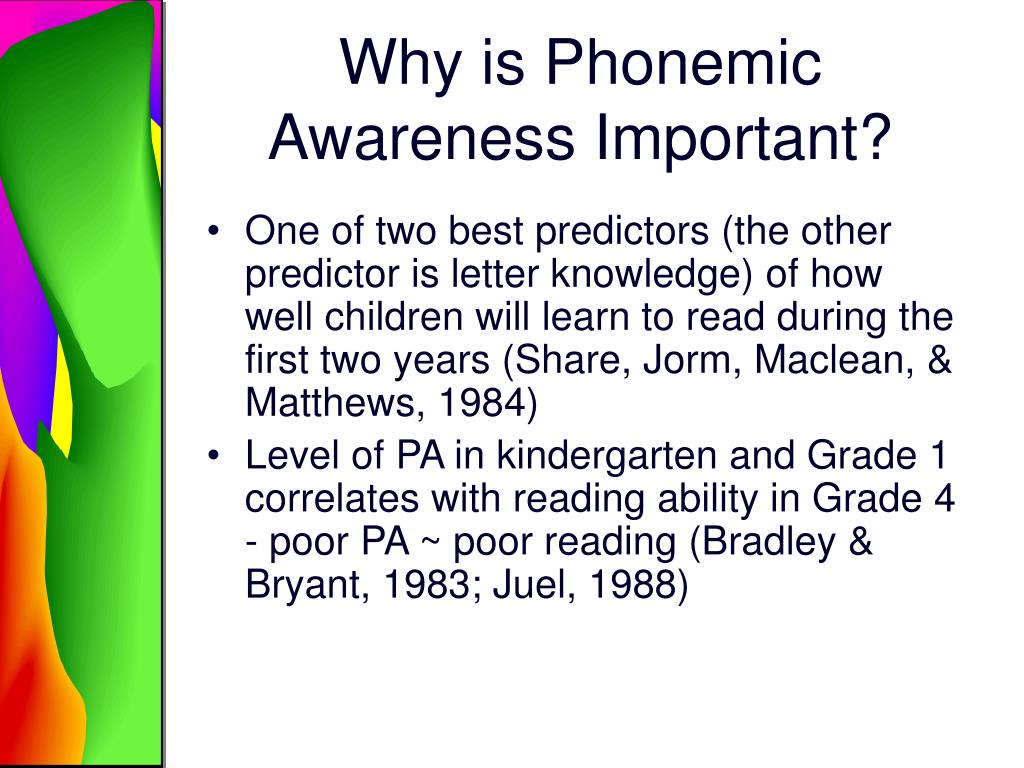

Phoneme awareness predicts later outcomes in reading and spelling

Phoneme awareness facilitates growth in printed word recognition. Even before a student learns to read, we can predict with a high level of accuracy whether that student will be a good reader or a poor reader by the end of third grade and beyond (Good, Simmons, and Kame'enui, 2001; Torgesen, 1998, 2004). Prediction is possible with simple tests that measure awareness of speech sounds in words, knowledge of letter names, knowledge of sound-symbol correspondence, and vocabulary.

Even before a student learns to read, we can predict with a high level of accuracy whether that student will be a good reader or a poor reader by the end of third grade and beyond (Good, Simmons, and Kame'enui, 2001; Torgesen, 1998, 2004). Prediction is possible with simple tests that measure awareness of speech sounds in words, knowledge of letter names, knowledge of sound-symbol correspondence, and vocabulary.

The majority of poor readers have relative difficulty with phoneme awareness and other phonological skills

Research cited in Module 1 has repeatedly shown that poor readers as a group do relatively less well on phoneme awareness tasks than on other cognitive tasks. In addition, at least 80 percent of all poor readers are estimated to demonstrate a weakness in phonological awareness and/or phonological memory. Readers with phonological processing weaknesses also tend to be the poorest spellers (Cassar, Treiman, Moats, Pollo, & Kessler, 2005).

Instruction in phoneme awareness is beneficial for novice readers and spellers

Instruction in speech-sound awareness reduces and alleviates reading and spelling difficulties (Adams, Foorman, Lundberg, & Beeler, 1998; Gillon, 2004; NICHD, 2000; Rath, 2001). Teaching speech sounds explicitly and directly also accelerates learning of the alphabetic code. Therefore, classroom instruction for beginning readers should include phoneme awareness activities.

Teaching speech sounds explicitly and directly also accelerates learning of the alphabetic code. Therefore, classroom instruction for beginning readers should include phoneme awareness activities.

Phonological awareness interacts with and facilitates the development of vocabulary and word consciousness

This argument is made much less commonly than the first four points. Phonological awareness and memory are involved in these activities of word learning:

- Attending to unfamiliar words and comparing them with known words

- Repeating and pronouncing words correctly

- Remembering (encoding) words accurately so that they can be retrieved and used

- Differentiating words that sound similar so their meanings can be contrasted

📖 Phonological Awareness, Speech Development, Chapter 11. Communication and Skill Development Disorders. Children's pathopsychology. Mash E. Page 87. Read online

At first, babies listen to the sounds of their parents' speech and soon begin to communicate using basic gestures and sounds. During their first year of life, they may learn a few words and even create new words to express their desires and emotions. After two years, language development is rapidly progressing, and their ability to coherently formulate their thoughts and express new concepts is the delight and admiration of parents. Adults play an important role in encouraging the development of a child's language skills by improving speech and enjoying children's expressions. nine0008

During their first year of life, they may learn a few words and even create new words to express their desires and emotions. After two years, language development is rapidly progressing, and their ability to coherently formulate their thoughts and express new concepts is the delight and admiration of parents. Adults play an important role in encouraging the development of a child's language skills by improving speech and enjoying children's expressions. nine0008

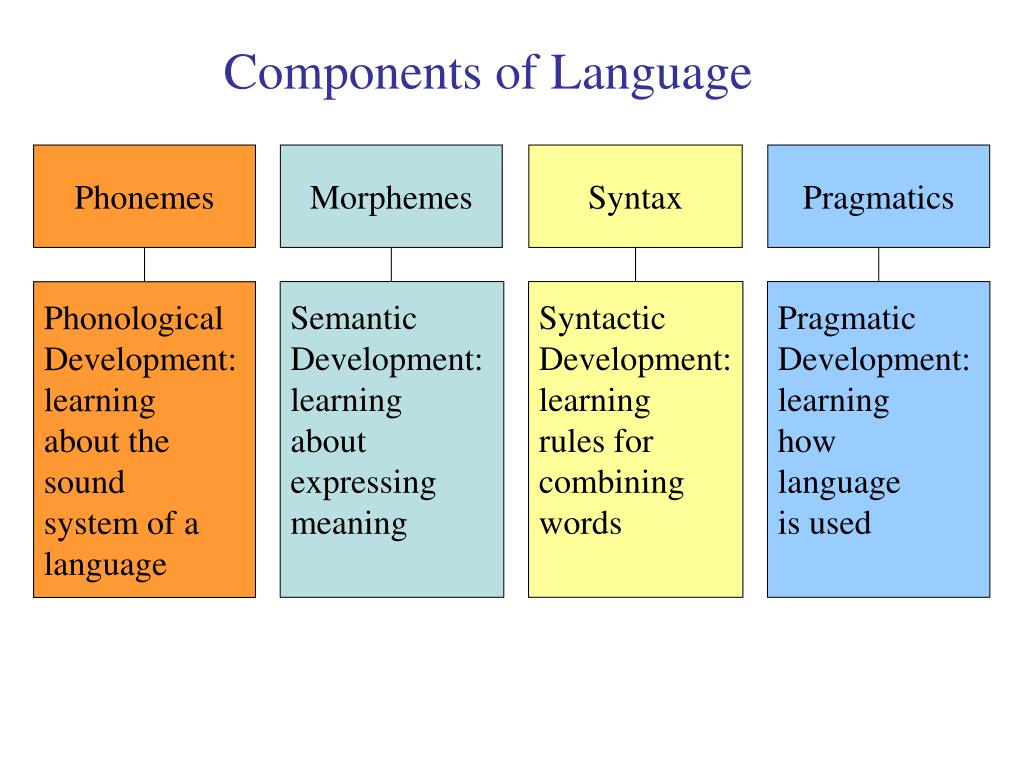

A language consists of phonemes that are basic sounds (such as plosives b, e or vowels and, e) and form the language. When a child constantly hears a particular phoneme, ear receptors stimulate the formation of appropriate connections and transmit them to the auditory part of the cerebral cortex. The formed perception map is a set of sounds similar to each other, which helps the child to recognize different phonemes. These cards form quickly; six-month-old babies of English-speaking parents already have auditory maps that differ from the auditory maps inherent, for example, in babies in Swedish families, which depends on the different activity of neurons for different sounds (Kuhl, 1995). By the first year of life, the cards are formed, and babies lose the ability to distinguish sounds that are not important for their native language.

By the first year of life, the cards are formed, and babies lose the ability to distinguish sounds that are not important for their native language.

It is the rapid development of the perceptual map that causes difficulties in learning a second language after the first: the fact is that the connections in the brain are already formed, and the remaining neurons are almost unable to form new basic connections, say, for the Swedish language. When the described cycle is established, babies can make words out of sounds, and the more words they hear, the faster they learn the language. Sounds serve to strengthen and expand neural connections, which in turn ensures the formation of more words. Similar cortical circuits are formed as the basis for other activities, such as music. A young child who is learning to play a musical instrument may have neuronal circulation activated, which will favorably develop his spatial thinking and mathematical abilities (Hancock, 1996).

Phonological awareness.

Not all children progress normally in their language development, some are very lagging behind, using mostly gestures or sounds to communicate, rather than speech. Others develop normally following verbal commands, but have difficulty finding words to express their thoughts clearly.

Psychology bookap

Although the development of speech is one of the main indicators of general intelligence, as well as the development of the school curriculum (Sattler, 1998), the difference in this indicator is in no way a sign of intellectual retardation or cognitive impairment in children. Rather, such deviations from the norm may indeed be only deviations and are accompanied by pronounced abilities in other areas. Albert Einstein, considered an intellectual genius, started talking late, stammering and making his parents think he was "not quite normal". Family tradition says that when a father asked the headmaster what profession he would advise his son to take, the answer was simple: “It does not matter, because he will never succeed in anything” (R. W. Clark, 1971, p. 10).

W. Clark, 1971, p. 10).

Because speech development is an indicator of overall mental development (Sattler, 1998), children with language delays or severe language delays are considered to be at risk. As is known, Albert Einstein's speech problems were precursors to his subsequent communication and learning disorders (Benasich, Curtiss & Tallal, 1993; B.A. Lewis, Freebarn & Taylor, 2000).

Phonology is the ability to memorize and store phonemes, as well as the rules for composing semantic compounds or words from sounds. The impairment of this ability is the main reason why most children and adults with communication and learning disabilities have language problems such as reading and writing. nine0008

A young child needs to realize that speech is divided into phonemes (English has 44, such as ba, ga, at and tr). Many children find it very difficult to understand that speech does not consist of individual phonemes that follow one another. Instead, the sounds are articulated at the same time as (overlapping) so that one can speak faster than if they were spoken consecutively (Liberman & Shankweiler, 1991).

Instead, the sounds are articulated at the same time as (overlapping) so that one can speak faster than if they were spoken consecutively (Liberman & Shankweiler, 1991).

Early language problems become learning problems when they enter school as children have to learn to correlate spoken language with written language. Children who find it difficult to learn to read and write also find it difficult to learn the system of letters and sounds. These children cannot correctly pronounce the sounds in the syllables of words, which is called a lack of phonological awareness and is a harbinger of reading problems (Frost, 1998).

Phonological awareness is a broad generalization that includes recognizing the relationships that exist between sounds and letters, determining rhythm and alliteration, and knowing that sounds can form different syllables in words. To determine the level of phonological awareness among primary school students, teachers ask them to rhyme words or rearrange sounds. For example, the teacher might say "cat" and ask the child to say the word without the first sound k, or say "home" and the child must say the word without m. the child pronounce these sounds together, adding them to the word "three".

To determine the level of phonological awareness among primary school students, teachers ask them to rhyme words or rearrange sounds. For example, the teacher might say "cat" and ask the child to say the word without the first sound k, or say "home" and the child must say the word without m. the child pronounce these sounds together, adding them to the word "three".

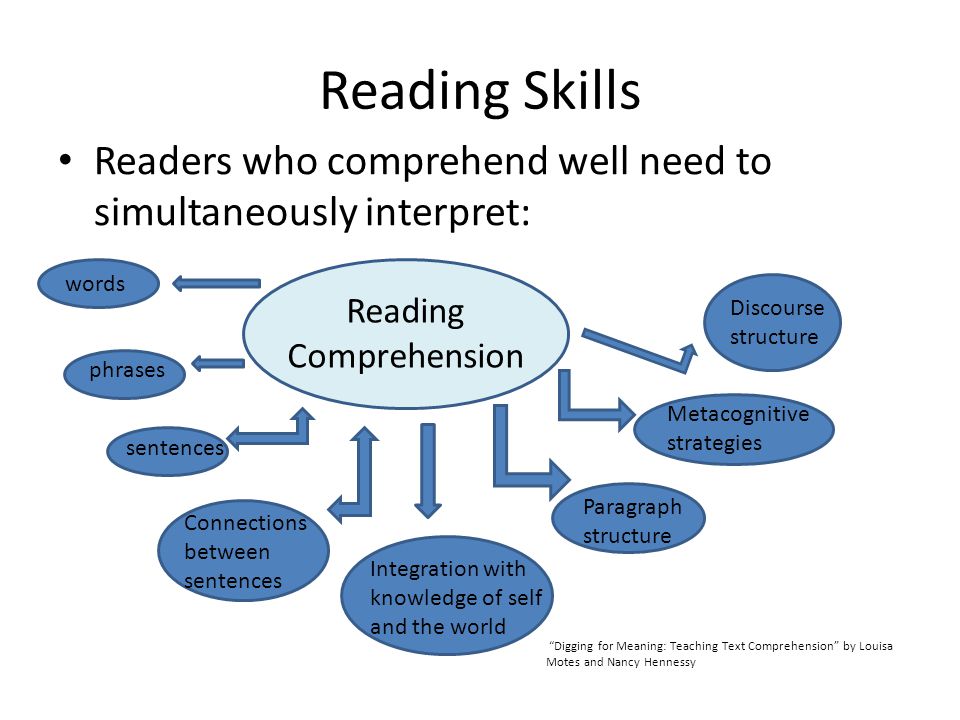

While phonological awareness is a prerequisite for developing reading skills, it is also closely related to the development of expressive language (Edwards, Fourakis, Beckman, & Fox, 1999). In the process of reading, it is very difficult for those who experience significant difficulties in pronouncing sounds to differentiate phonemes, remember the names of ordinary objects and letters, as well as store phonological codes in short-term memory, recognize a phoneme and reproduce some speech sounds. For the most part, reading and comprehension depend on speed and the automatic ability to recognize individual words. Slow and inattentive children face very great difficulties in reading comprehension (Lyon, 1996).

Slow and inattentive children face very great difficulties in reading comprehension (Lyon, 1996).

Section summary.

- The development of speech is based on the innate ability and acquired capabilities to learn, store and reproduce the basic sounds in the language, it occurs very quickly, in early childhood.

- Deficiency in phonological awareness the ability to distinguish the sounds of a language is the main cause of communication disorders and impaired development of school skills.

Literacy as a result of language development and its impact on the psychosocial and emotional development of children

Bruce Tomblin, PhD

University of Iowa, USA

, 2nd ed. (English). Translation: June 2016

Introduction

One of the most amazing achievements in the preschool years is the effortless development of speech and language. From the point of view of the development of oral speech, the preschool years are a period of language learning. When children enter school, they are expected to use these newly acquired language skills as tools for learning and, to an increasing extent, for negotiating with others. The important role of oral and written communication in the lives of schoolchildren suggests that individual differences in these skills may entail risks to broader academic and psychosocial competence. nine0008

From the point of view of the development of oral speech, the preschool years are a period of language learning. When children enter school, they are expected to use these newly acquired language skills as tools for learning and, to an increasing extent, for negotiating with others. The important role of oral and written communication in the lives of schoolchildren suggests that individual differences in these skills may entail risks to broader academic and psychosocial competence. nine0008

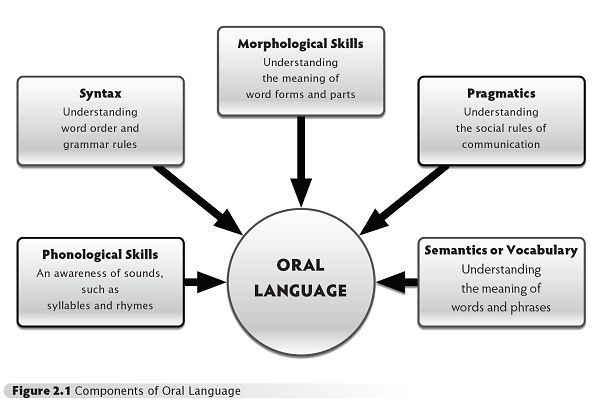

Subject

Oral language competence includes several systems. Children must master the system of representing the meaning of things in their world. Children should also achieve ease in using the forms of language, from the sound structure of words to the grammatical structure of sentences. In addition to this, social competence must be added to this knowledge. The development of these skills, which occurs in the preschool period, will allow the child to successfully act as a listener and speaker in various communication contexts. For the most part, this learning occurs naturally, without specially organized training, and, as you know, is unconscious in nature. Even as preschoolers, children begin to develop awareness of some of this knowledge. They can rhyme words, and they can also manipulate parts of words, such as dividing the word "child" into two syllables: /di/ and /tya/. This ability to think about the properties of words is called phonological processing. There is a solid body of evidence that early reading development in alphabetic languages, such as English, depends on the development of acquired phonological processing skills. nine0083 1

For the most part, this learning occurs naturally, without specially organized training, and, as you know, is unconscious in nature. Even as preschoolers, children begin to develop awareness of some of this knowledge. They can rhyme words, and they can also manipulate parts of words, such as dividing the word "child" into two syllables: /di/ and /tya/. This ability to think about the properties of words is called phonological processing. There is a solid body of evidence that early reading development in alphabetic languages, such as English, depends on the development of acquired phonological processing skills. nine0083 1

Learning to read also requires some skills. It is customary to distinguish between two main aspects of reading - word recognition and reading comprehension. Word recognition is about understanding how a word is pronounced. Experienced readers can do this using numerous "hints", but what is important is that they are able to use the conventional rules regarding the relationship between a sequence of letters and their pronunciation (decoding). It turns out that phonological processing abilities play an important role in the development of this knowledge and in the ability of an individual to recognize words. However, decoding printed words is not essential for reading competence. The reader needs to be able to interpret printed text in much the same way that he understands sentences when he hears them. The skills used in this process of reading comprehension are similar or the same as those used in listening comprehension. nine0008

It turns out that phonological processing abilities play an important role in the development of this knowledge and in the ability of an individual to recognize words. However, decoding printed words is not essential for reading competence. The reader needs to be able to interpret printed text in much the same way that he understands sentences when he hears them. The skills used in this process of reading comprehension are similar or the same as those used in listening comprehension. nine0008

Issues

Children may enter school with poor listening, speaking and/or phonological processing skills. Children with poor listening and speaking skills are defined as children with language impairments (LI) and most of them will also show poor phonological processing abilities. According to the current estimate, about 12% of children entering school in the US and Canada have JAN. 2.3 There are other children who are competent enough in listening and speaking to be considered "normal" in this regard, but for whom phonological processing remains a weakness. These children may be considered at risk for developing reading disorders (RD) when they enter school. Reading disorder is traditionally defined as a low level of reading proficiency that occurs after sufficient opportunities have been gained to learn to read. Therefore, the diagnosis of RF is made after two or three years of learning to read. RF prevalence rates among schoolchildren vary between 10% and 18%. nine0083 4.5 Behavioral problems such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and internalizing type problems such as shyness and anxiety have been found to be common among children with RF and similarly among children with JD .6

These children may be considered at risk for developing reading disorders (RD) when they enter school. Reading disorder is traditionally defined as a low level of reading proficiency that occurs after sufficient opportunities have been gained to learn to read. Therefore, the diagnosis of RF is made after two or three years of learning to read. RF prevalence rates among schoolchildren vary between 10% and 18%. nine0083 4.5 Behavioral problems such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and internalizing type problems such as shyness and anxiety have been found to be common among children with RF and similarly among children with JD .6

Scientific context

The relationship between oral language development, reading development, and social development has been studied by several researchers who have attempted to determine the extent to which these problems are related to each other and to identify the basis for these relationships. nine0008

Key questions

Significant research questions have been about the extent to which early language status portends later reading and behavioral problems, and what possible grounds for these relationships might be. In particular, two hypotheses are clearly traced in the literature. According to one hypothesis, the relationship between oral language and further outcomes is of a causal nature. According to another hypothesis, the association of behavioral problems with language problems and reading problems may stem from a common pathological condition - for example, retardation of neurobiological maturation, which leads to poor achievement in both areas. nine0008

Recent research findings

A number of researchers have studied the psychosocial consequences and outcomes of reading in primary school children with ID. Some studies have noted that children with language impairments had a lower level of reading development, and RF was more common. 7-12 In these studies, the prevalence of RF in children with JAN ranged from 25% to 90%. 11 It has been found that the strong relationship between RF and YN is due to the limitations that these children have in both language comprehension and phonological awareness. nine0083 13.14 Lack of phonological awareness may put them at risk of having difficulty learning decoding skills, and problems with listening comprehension may lead to difficulty in reading comprehension.

Several studies have found an increased rate of behavioral problems among children with UI. 2.15-20 The most common behavioral problem reported in these studies was ADHD; however, problems of the internalizing type, such as anxiety disorder, have also been noted. Some studies have found that these behavioral problems seem to vary depending on the setting in which the child is observed, with these problems reported mostly by the children's teachers rather than their parents. nine0083 21 This has been interpreted as evidence that such behavioral problems may occur more frequently in the school setting than at home and are thus a response to school stress. Further support for this view comes from evidence that a predominance of behavioral problems in children with RF and/or JAN is found in children with both disorders. 6 Thus, these studies support the notion that JON combined with RF results in the child experiencing excessive failure, especially in the classroom, which in turn leads to behavioral problems of a reactive nature. These findings, however, cannot explain why behavioral problems are found in preschool children with ID. nine0083 22 This information can be used to argue that a common factor, such as neurodevelopmental delay, contributes to the development of all these disorders.

nine0083 21 This has been interpreted as evidence that such behavioral problems may occur more frequently in the school setting than at home and are thus a response to school stress. Further support for this view comes from evidence that a predominance of behavioral problems in children with RF and/or JAN is found in children with both disorders. 6 Thus, these studies support the notion that JON combined with RF results in the child experiencing excessive failure, especially in the classroom, which in turn leads to behavioral problems of a reactive nature. These findings, however, cannot explain why behavioral problems are found in preschool children with ID. nine0083 22 This information can be used to argue that a common factor, such as neurodevelopmental delay, contributes to the development of all these disorders.

Conclusions

Overall, the literature supports a strong relationship between oral language skills and subsequently developed reading and behaviour. This fact stems mainly from studies of children with JD as they enter school. The basis of the relationship between early oral language and later reading development is believed to be causal, with oral language skills being fundamental precursors to later successful reading. This influence of language on reading primarily includes two components of language ability - phonological processing and listening comprehension. Children with underdeveloped phonological processing skills are at risk of early decoding problems that can later lead to reading comprehension problems. Children with hearing comprehension problems are at risk of developing reading comprehension problems, even if they can decode words. A common characteristic of children with JD is that both aspects of language are impaired, and therefore the resulting reading problems affect both aspects of reading (decoding and comprehension). The basis of the relationship between spoken language and subsequent behavioral problems is less understood.

This fact stems mainly from studies of children with JD as they enter school. The basis of the relationship between early oral language and later reading development is believed to be causal, with oral language skills being fundamental precursors to later successful reading. This influence of language on reading primarily includes two components of language ability - phonological processing and listening comprehension. Children with underdeveloped phonological processing skills are at risk of early decoding problems that can later lead to reading comprehension problems. Children with hearing comprehension problems are at risk of developing reading comprehension problems, even if they can decode words. A common characteristic of children with JD is that both aspects of language are impaired, and therefore the resulting reading problems affect both aspects of reading (decoding and comprehension). The basis of the relationship between spoken language and subsequent behavioral problems is less understood. Behavioral problems can arise from oral and written communication needs in the classroom. Accordingly, communication failure serves as a stress factor, and behavioral problems are an inadequate response to this stress factor. On the other hand, oral and written language disorders may share an underlying etiology with behavioral problems. nine0008

Behavioral problems can arise from oral and written communication needs in the classroom. Accordingly, communication failure serves as a stress factor, and behavioral problems are an inadequate response to this stress factor. On the other hand, oral and written language disorders may share an underlying etiology with behavioral problems. nine0008

Recommendations

Evidence strongly suggests that a foundation of oral language competence is essential to the successful achievement of academic and social competence. Children with poor language skills, who are therefore at risk of developing psychosocial and reading problems, can be successfully identified at school entry. Remedial techniques are available to enhance language development: in particular, there are numerous programs designed to support the development of phonological processing skills. Similarly, in elementary school, listening comprehension can be improved. These methods are aimed at consolidating language skills. In addition, remedial efforts should consider methods that help provide these children with an adapted and supportive educational environment and reduce potential stressors that can lead to inappropriate behaviour. In the future, research is needed to study the mechanisms that cause this complex of oral-speech, written and behavioral problems. Of particular relevance would be research conducted in the school setting and aimed at studying how children respond to communicative expectations and failures. nine0008

Literature

- Snow CE, Burns MS, Griffin P, eds. Preventing reading difficulties in young children . Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998.

- Beitchman JH, Nair R, Clegg M, Patel PG, Ferguson B, Pressman E, Smith A. Prevalence of speech and language disorders in 5-year-old kindergarten children in the Ottawa-Carleton region. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 1986;51(2):98-110.

- Tomblin JB, Records NL, Buckwalter P, Zhang X, Smith E, O'Brien M.

Prevalence of specific language impairment in kindergarten children. nine0152 Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 1997;40(6):1245-1260.

Prevalence of specific language impairment in kindergarten children. nine0152 Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 1997;40(6):1245-1260. - Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA. Unlocking learning disabilities: The neurological basis. In: Cramer SC, Ellis W, eds. Learning disabilities: Lifelong issues . Baltimore, Md: P.H. Brooks Publishing; 1996:255-260.

- Commission on Emotional and Learning Disorders in Children. One million children: A national study of Canadian children with emotional and learning disorders . Toronto, Ontario: Leonard Crainford; nineteen70.

- Tomblin JB, Zhang X, Buckwalter P, Catts H. The association of reading disability, behavioral disorders, and language impairment among second-grade children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 2000;41(4):473-482.

- Aram DM, Ekelman BL, Nation JE. Preschoolers with language disorders: 10 years later. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 1984;27(2):232-244.

- Bishop DV, Adams C. A prospective study of the relationship between specific language impairment, phonological disorders and reading retardation. nine0152 Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 1990;31(7):1027-1050.

- Catts HW. The relationship between speech-language impairments and reading disabilities. J ournal of Speech & Hearing Research 1993;36(5):948-958.

- Silva PA, Williams S, McGee R. A longitudinal study of children with developmental language delay at age 3: Later intelligence, reading and behavior problems. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 1987;29(5):630-640.

- Stark RE, Bernstein LE, Condino R, Bender M, Tallal P, Catts H. 4-year follow-up-study of language impaired children. Annals of Dyslexia 1984;34:49-68.

- Stark RE, Tallal P. Language, speech, and reading disorders in children: neuropsychological studies . Boston, Mass: Little, Brown and Co.

; 1988.

; 1988. - Catts HW, Fey ME, Zhang XY, Tomblin JB. Estimating the risk of future reading difficulties in kindergarten children: A research-based model and its clinical implementation. nine0152 Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools 2001;32(1):38-50.

- Catts HW, Fey ME, Zhang X, Tomblin JB. Language basis of reading and reading disabilities: Evidence from a longitudinal investigation. Scientific Studies of Reading 1999;3(4):331-362.

- Beitchman JH, Hood J, Inglis A. Psychiatric risk in children with speech and language disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 1990;18(3):283-296.

- Beitchman JH, Hood J, Rochon J, Peterson M. Empirical classification of speech/language impairment in children: II. behavioral characteristics. nine0152 Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1989;28(1):118-123.

- Beitchman JH, Tuckett M, Batth S. Language delay and hyperactivity in preschoolers: Evidence for a distinct subgroup of hyperactives.

Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 1987;32(8):683-687.

Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 1987;32(8):683-687. - Beitchman JH, Brownlie EB, Wilson B. Linguistic impairment and psychiatric disorder: pathways to outcome. In: Beitchman JH, Cohen NJ, Konstantareas M, Tannock R, eds. Language, learning, and behavior disorders: Developmental, biological, and clinical perspectives . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1996:493-514.

- Stevenson J, Richman N, Graham PJ. Behavior problems and language abilities at three years and behavioral deviance at eight years. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 1985;26(2):215-230.

- Benasich AA, Curtiss S, Tallal P. Language, learning, and behavioral disturbances in childhood: A longitudinal perspective. nine0152 Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1993;32(3):585-594.

- Redmond SM, Rice ML. The socioemotional behaviors of children with SLI: Social adaptation or social deviance? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 1998;41(3):688-689.