What sounds does the letter a make

Learn Pronunciation with Speak Method

The Sounds of the Alphabet: Learn Pronunciation with Speak Method| English Online with Speak Method |

|

| Online Classes | Pronunciation Facts | R, Th, T and other sounds | 500 Words Practice |

| Local Classes | Business Communication | TOEFL Prep | ESL Stories |

| Contact us | Vowel

Sounds |

Grammar and Idioms | For Young People |

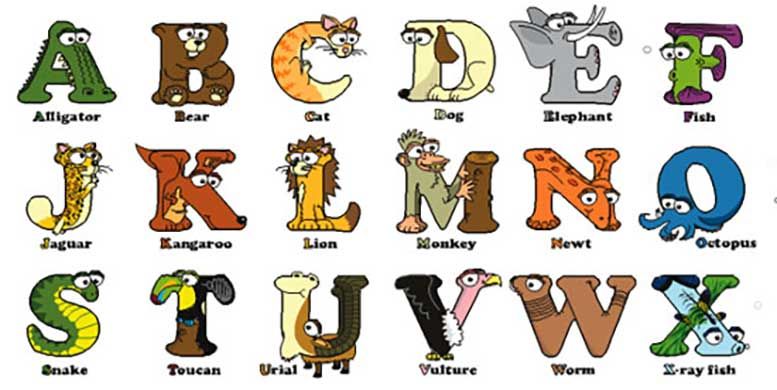

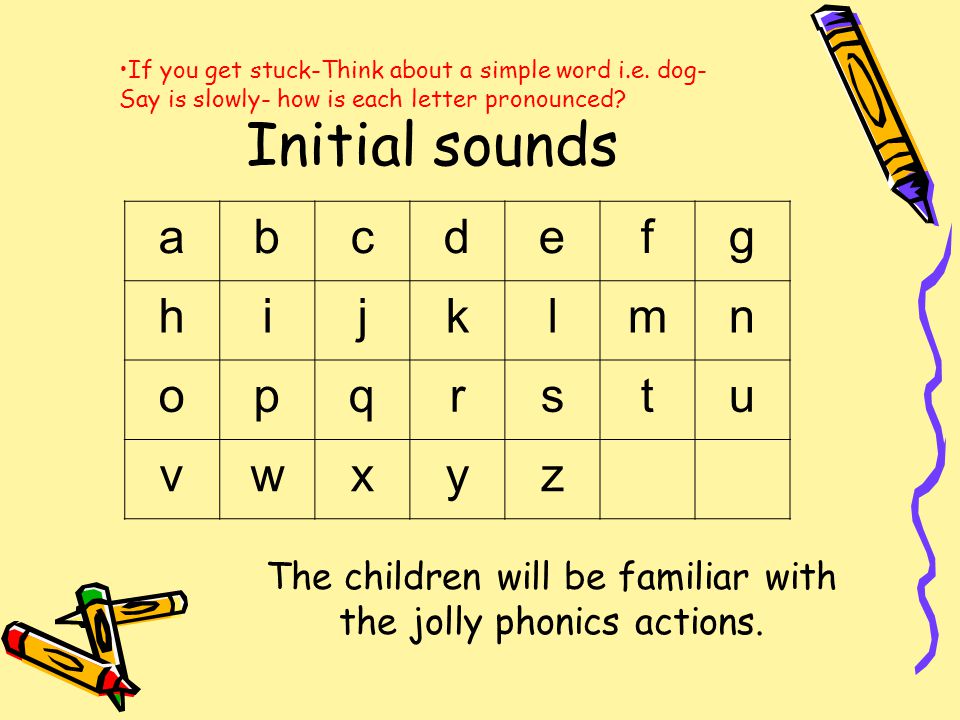

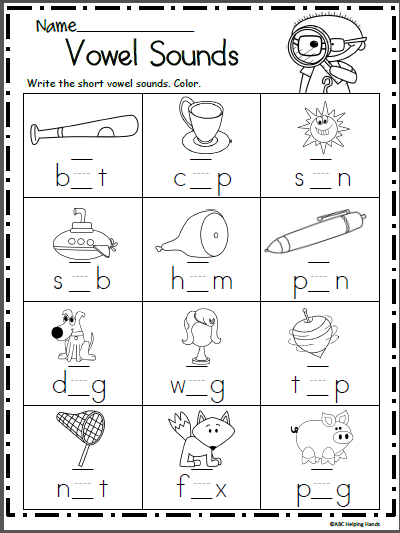

With

this alphabet chart, understand how to say

the names of the letters and read about all the sounds of each letter

from the alphabet. These are the basic phonetic sounds for American English. To learn important sounds using free videos

online, go to Pronunciation in

English: 500 Words.

|

Letter |

Sound of Letter Name |

All sounds of letter |

Examples |

|

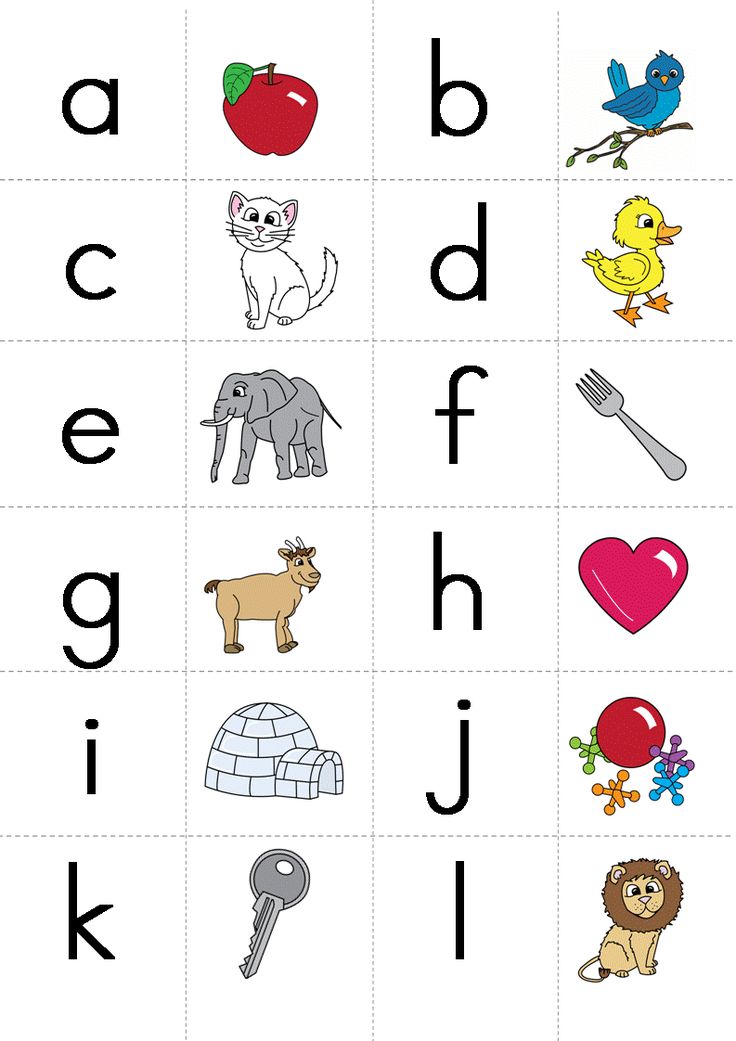

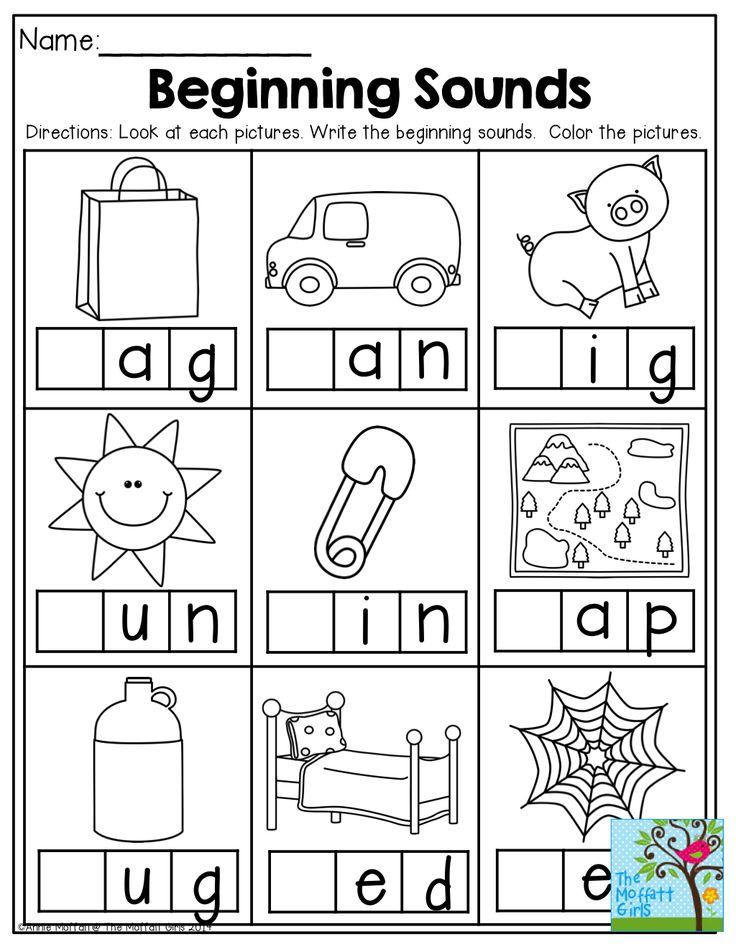

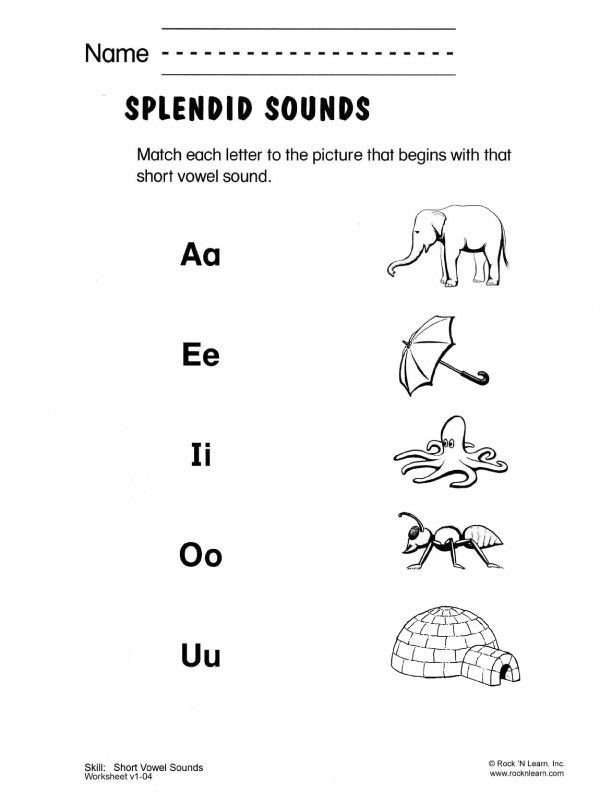

A, a |

ā-ee (long a to long e, also spell "ay") |

, ā, ah, ā-uh, uh |

cat, late, all, and, around |

|

B, b |

Bee |

buh |

bike |

|

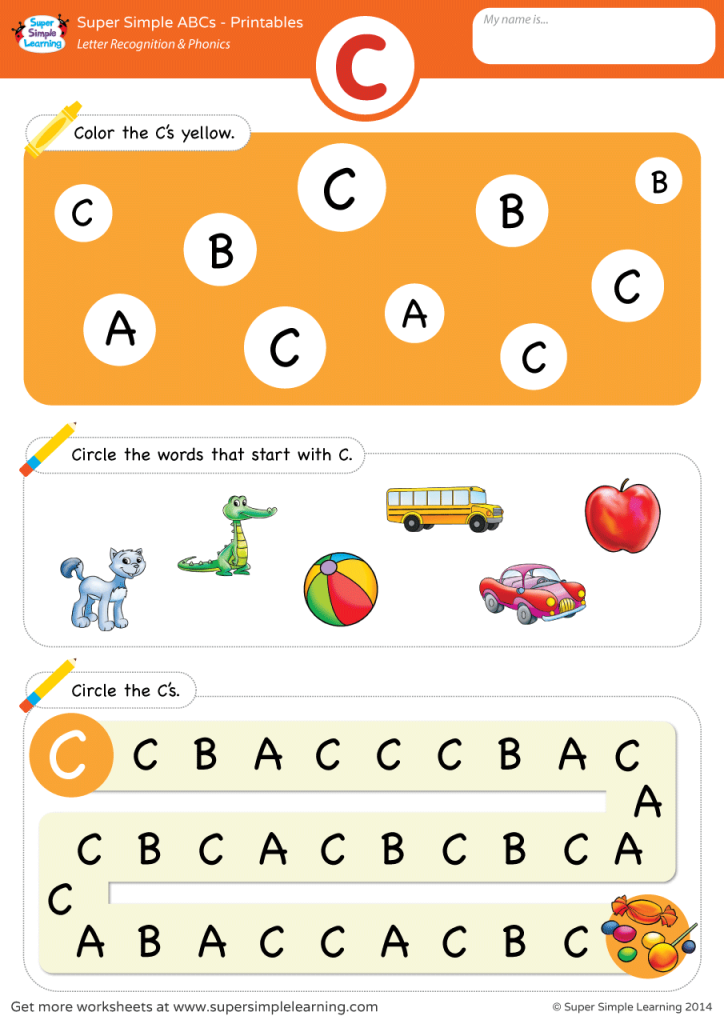

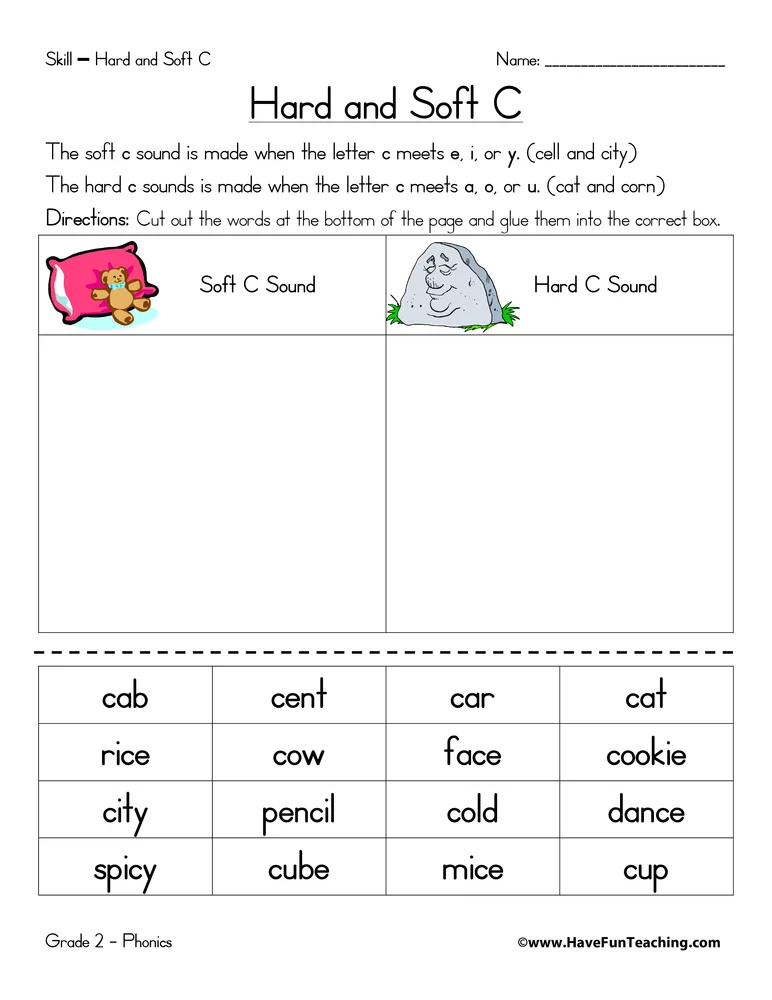

C, c |

See |

kuh, suh |

cake, city |

|

D, d |

Dee |

duh |

did |

|

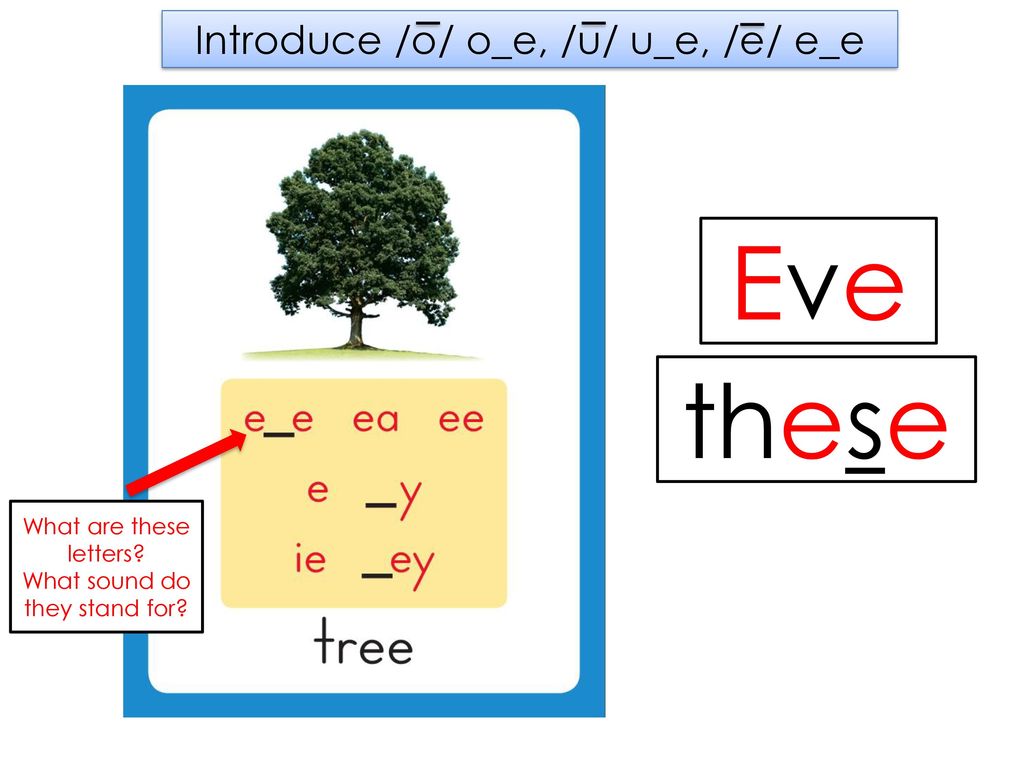

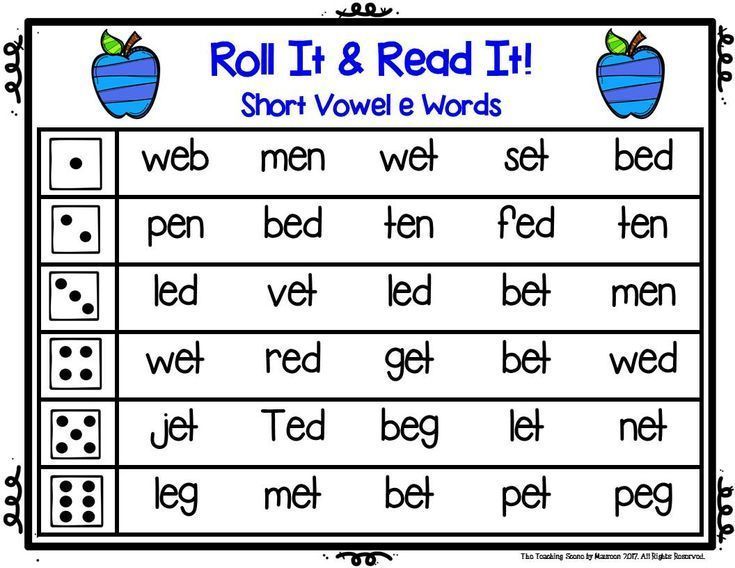

E, e |

Ee |

eh, ee, silent |

bed, free, late |

|

F, f |

Ef |

fuh |

fed |

|

G, g |

Jee |

guh, juh |

glad, large |

|

H, h |

ā-ch |

huh, silent |

hotel, what |

|

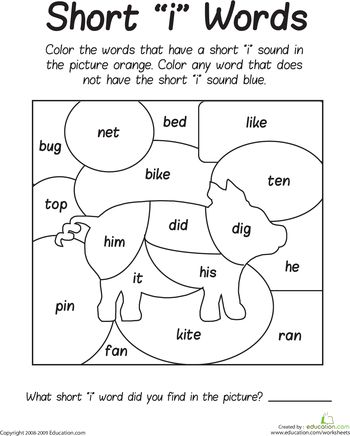

I, i |

ah-ee |

ah-ee, ĭ |

light, sit |

|

J, j |

Jay |

juh |

jump |

|

K, k |

Kay |

kuh |

kite |

|

L, l |

El |

luh, ul |

lot, full |

|

M, m |

Em |

muh |

mother |

|

N, n |

En |

nuh |

nest |

|

O, o |

ō (oh) |

ah, ō, uh, oo, ů |

hot, slow, computer, fool, good |

|

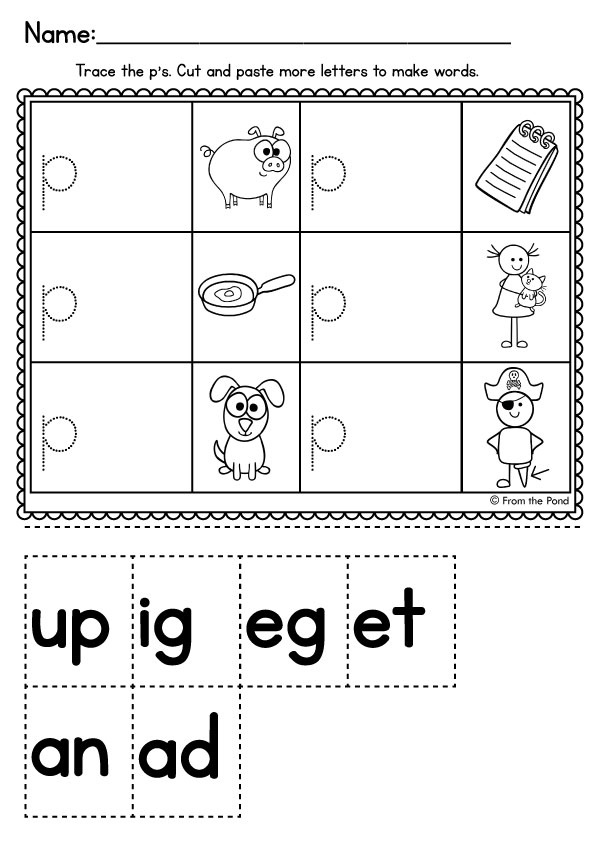

P, p |

Pee |

puh |

put |

|

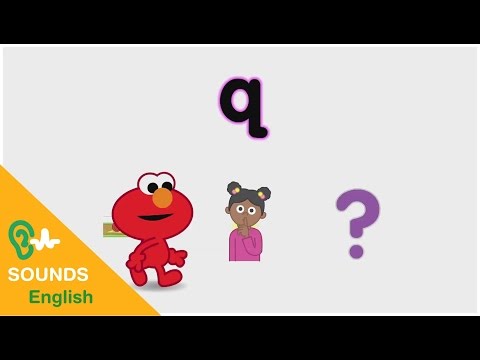

Q, q |

Kyoo (kyū) |

kwuh |

quick |

|

R, r |

Ah-r |

ruh, ur |

race, stir |

|

S, s |

Es |

suh, zuh |

stick, is |

|

T, t |

Tee |

tuh, duh, N, silent, stopped tuh |

table, better, mountain, interview, hot |

|

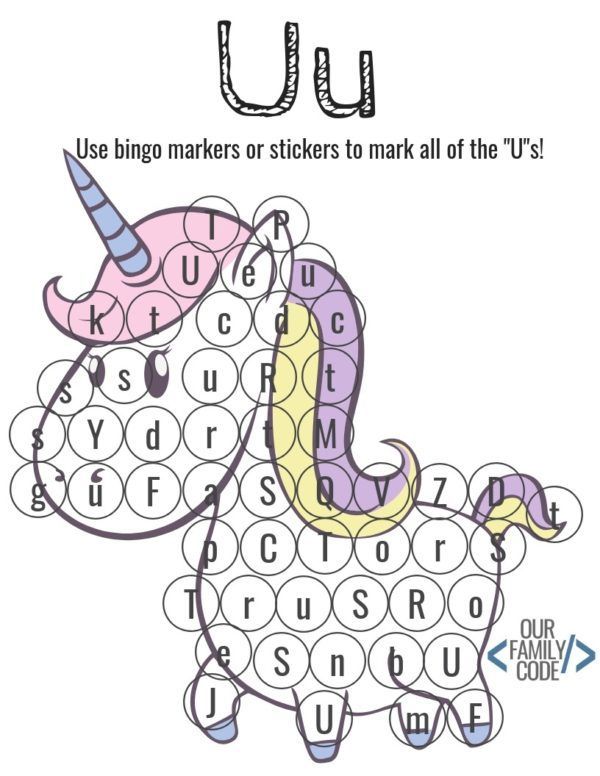

U, u |

Yoo (yū) |

uh, yoo, oo, ů |

up, use, flute, full |

|

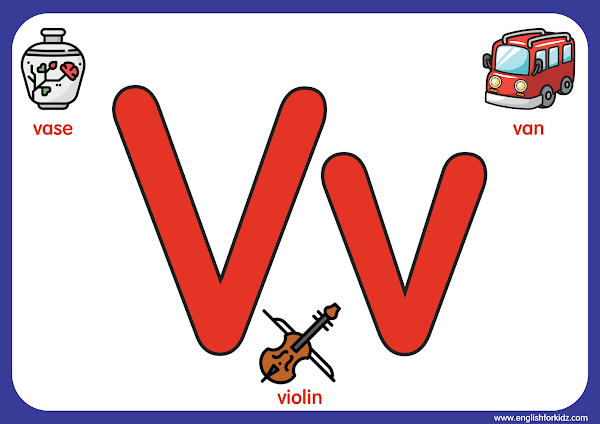

V, v |

Vee |

vuh |

very |

|

W, w |

Dubōyoo |

wuh, silent |

well, slow |

|

X, x |

Eks |

ks, zuh |

box, xylophone |

|

Y, y |

Wah-ee |

yuh, ee, ah-ee (i), ĭ |

yes, happy, try, cylinder |

|

Z, z |

Zee |

zuh |

zebra |

|

|

|

|

|

pronunciation English

pronunciation Learn More Sound American: Change Your Speech The 500 Common English Words What is a Vowel? English Free Online |

Speakmethod. com: English

Pronunciation, Seattle, WA

com: English

Pronunciation, Seattle, WA

English online with Speak Method

Why letters don’t ‘make’ sounds. – The Literacy Blog

UncategorizedJohn

Someone called Robert has added a comment to my post ‘Masha Bell rings the wrong note on reading’. In it, he is objecting to the emphasis I made on the fact that many teachers say that letters ‘make’ sounds when they do no such thing. He thinks that this detracted from my argument in the posting because he believes it is ‘nit-picking’ and that ‘Masha [Bell] knows quite well that letters do not make sounds in the same way that people make sounds’.

This is an interesting question. I’m sure when we raise this issue with teaching professionals on our courses, many immediately think it to be a nit-picking/angels dancing on the head of a pin sort of a point.

It isn’t! I’m quite sure that Robert is right when he claims that Masha understands that spellings represent sounds in the language, after all, she learnt English as a second, third, or possibly, fourth language. So, let’s be clear: for Masha, it isn’t a question about knowledge of how the code works; it’s actually a question of pedagogy.

Here’s why. Very many teaching practitioners have developed the habit of saying that letters ‘make’ or ‘say’ sounds. They don’t! Letters or, to use more accurate vocabulary, spellings represent sounds in the English language.

It may appear that this is a trivial point but, in fact, it underpins the whole orientation of the alphabetic code: sounds in speech precede the written representations of them. Humans make sounds; the spellings represent them. Letters or spellings do not have or possess any agency or power of their own. The writing system was invented to represent sounds in the language and the writing system is symbolic. It is also arbitrary: there is no particular reason why we represent the sound /o / as in ‘hot’ by the spelling < o > (except for the fact that the English alphabet is derived mainly from Latin).

It is also arbitrary: there is no particular reason why we represent the sound /o / as in ‘hot’ by the spelling < o > (except for the fact that the English alphabet is derived mainly from Latin).

This may seem to be of merely theoretical significance. Again, it isn’t! It has profoundly practical implications because when, at an early stage in their reading and writing development, young children are coming to grips with the writing system and they are told that the letters ‘make’ sounds, they are left wondering where all these sounds come from. When this is compounded by the kind of unstructured teaching that tells them that the spelling < a > ‘makes’ the sound /a / in ‘mat’, the sound /o / in ‘wasp’, the sound /or / in ‘water’, the sound /ae / in ‘baby’, or even the sound /e / as in ‘many’, they can easily jump to the conclusion that there is ‘no rhyme nor reason’ to the way reading and writing works. It appears to them as if the spelling can ‘make’ any sound and, furthermore, that there is no logic to what they are trying to learn.

This isn’t, of course, the case. There are very common patterns in the English language that are remarkably consistent. For example, after the sound /w /, we very often spell the sound /o / with the spelling < a >, as in ‘was’, ‘swan’, ‘watch’, and so on. Similarly, the spelling of the sound /or / before the sound /l / is often spelled with the spelling < a >, as in ‘wall’, ‘also’, and others. The same is true for many other patterns.

You may think that young children would have difficulty with understanding the role of symbols in representing sounds. Not so! Even at an early age, children are coming to terms with symbolic language: that something can stand for something else. This understanding is usually developed through symbolic play, followed by drawing, and then what Vygotsky referred to as the second-order symbolism of writing. So, by the time the pupil is ready to begin school, for most pupils, teaching them that spelling symbols represent the sounds in their speech and that the sounds in their speech can be represented by spelling symbols is something they find easy to grasp. And, as long as the teacher knows how to teach this system, from simple to complex, it is easy to learn.

And, as long as the teacher knows how to teach this system, from simple to complex, it is easy to learn.

Hi, my name's John Walker and I'm the director of Sounds-Write. By giving your email address and clicking on the link you receive in your email, you will receive a free sample of our ‘Help your child to read and write’ workbook and our monthly newsletter. We won’t pass your email address on to anybody else and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Email address:

Vowel sound [a], letters A, a

Lesson 1. ABCD - video lessons on the study of sounds and letters

In this lesson, children will get acquainted with the vowels A,a and the sound [a] along with the stork, whose name is Alyosha. They will see how the printed letters A are written, and they will help Alyosha to finish the erased letters. They will find out when the capital letter A is written, and when it is small, they will play an interesting game and see how black and white pictures turn into color ones. At the end of the lesson, Alyosha goes on an excursion to the forest and sees where words with the letters A,a meet in life.

At the end of the lesson, Alyosha goes on an excursion to the forest and sees where words with the letters A,a meet in life.

Summary of the lesson "The vowel sound [a], letters A, a"

Here are two pillars obliquely,

And between them is a belt.

Do you know this letter? BUT?

The letter A is in front of you. writer ─ Samuil Yakovlevich Marshak. In our lesson we will study letter A together with a stork. Let's get to know each other better.

Stork is big and smart a bird that is not afraid of people and very often lives near human habitation. And our stork's name is Alyosha. His name begins with sound [a] and ends with the sound [a] . We will record all sounds in square brackets.

Sound [a] is indicated on the letter large letter A and small letter a . Alyosha wants to learn a lot about the letter A. Therefore, we will now tell him everything, everything about her.

Alyosha wants to learn a lot about the letter A. Therefore, we will now tell him everything, everything about her.

As we have already said, the letter A in writing means one sound [a] . The sound [a] is a vowel sound which easy to pronounce and can be sung loudly and for a long time. Let's try to pull sound ah-ah-ah-ah-ah … Its easy pull and sing. Such sounds that are easy to pull are called vowels. So A - vowel . Since letter And denotes a vowel sound, then we will depict it in red.

So, sound [a] we we pronounce and hear, we see and write the letter .

As we said, the letter A can be large (it is called capital ) and small (it is called lowercase ).

And now we will show Alyosha how these letters are written. A large letter is always greater than a small letter, and a small letter is always smaller, than the big .

A large letter is always greater than a small letter, and a small letter is always smaller, than the big .

̶ Alyosha, for me now need your help. Someone joked and erased half of all the letters. Please help me restore them.

Well, we learned how to write letters, and now tell Alyosha, when these letters are written . If someone or something is given names, then these names are written with a capital letter (there are many storks, but our stork is called Alyosha, and we write his name with a capital letter). Another with a capital letter are spelled names, patronymics and surnames of people. For example: Anna Alexandrovna, Alice, Aibolit. C capital letter names of animals are written. For example: cow Agafya, cat Anfisa and the dog Artemon.

And also with a capital letter are written names of cities, rivers, lakes and villages.

Also capital letters spell words at the beginning of a sentence.

Example:

The bus was driving down the road. And the kids were in it.

All other words are written with a small letter.

Well, we got to know with the letters A, and . Now let's play a very interesting game. It is necessary to name two objects, in the names which we hear sound [a] .

Did it happen to you?

Oh, who came to visit us?

Look, this is Dunno. Wow, in the name Dunno also has letters and . And with two.

Now look at the words. What did you notice?

The letter A can be at the beginning of a word, in the middle and at the end.

And in one word there can be one or more letters a .

Well, we got acquainted with sound [a] , which on the letter can be designated: large letter A and small letter a .

And in order to better remember the letter a, let's Alyosha we will take a walk into the forest and see where the words from sound [a] may meet in our lives.

Won hare sitting. And butterflies fly. AT these words have sound [a] .

Let's go further, otherwise it's like an oblique scared.

Wow, so many colors. Interestingly, in their names there is sound [a] .

Let's think.

̶ Alyosha, name the flowers, which you know.

̶ Well done.

Listen to where these sounds are.

Of course, in the middle.

Well, we got acquainted with the letter A and sound [a] .

The letter A is the very first in the alphabet with which we will meet a little later.

Next lesson 2 Vowel sound [o], letters O, o

Get a complete set of video tutorials, tests and presentations ABVGDyka - video lessons on the study of sounds and letters

To add a comment, register or log in

The letter a makes a sound.

Vowels and consonants and sounds

Vowels and consonants and sounds Determining the borders of the Crimean Khanate is rather problematic, it is obvious that it had no definite borders with most neighboring states. This is what V.D. Smirnov, who studied the history of the Crimean Khanate in detail and quite well. He emphasizes that the issue of territorial boundaries, the area of the Crimean Khanate is further complicated by the fact that the emergence of the Khanate itself as a separate state center is fraught with many ambiguities. Its history becomes completely reliable only from the moment when it came into close contact with the Ottoman Empire, falling into vassal dependence on it under Sultan Mohammed II. Early history has many blank spots. Only one coastal strip, long mastered by European colonists, is a definite exception, but also not to the full extent.

Therefore, we can only determine the approximate boundaries of this state. The Crimean Khanate is, first of all, Crimea itself, however, its southern coast initially belonged to the Genoese, and since 1475 went to the Turkish sultan; independent before the invasion of the Turks on the peninsula was the Principality of Theodoro. As a result, the khan owned only the foothill and steppe part of the Crimea. Perekop was not a border, through it the khan had an exit from the Crimea to the “field”, where the northern outlines of the Crimean Khanate were lost in the boundless steppe expanses. A significant part of the Tatars constantly wandered beyond Perekop. In the spring, they rushed to the steppe expanses of the Northern Black Sea region to pastures and the Crimean uluses proper. Known are those tracts in the steppe where in the 15th century military forces guarded the nomad camps, which, to a certain extent, can be considered the approximate borders of the Crimean Khanate. Thus, the Molochnaya (or Mius) River begins as the border of the Crimean Khanate from the side of Astrakhan and the Nogays. In the north, the Crimean possessions reach Horse Waters. In 1560, all the Crimean uluses were pushed back beyond the Dnieper, to the borders of the Lithuanian principality.

As a result, the khan owned only the foothill and steppe part of the Crimea. Perekop was not a border, through it the khan had an exit from the Crimea to the “field”, where the northern outlines of the Crimean Khanate were lost in the boundless steppe expanses. A significant part of the Tatars constantly wandered beyond Perekop. In the spring, they rushed to the steppe expanses of the Northern Black Sea region to pastures and the Crimean uluses proper. Known are those tracts in the steppe where in the 15th century military forces guarded the nomad camps, which, to a certain extent, can be considered the approximate borders of the Crimean Khanate. Thus, the Molochnaya (or Mius) River begins as the border of the Crimean Khanate from the side of Astrakhan and the Nogays. In the north, the Crimean possessions reach Horse Waters. In 1560, all the Crimean uluses were pushed back beyond the Dnieper, to the borders of the Lithuanian principality.

Thus, the borders of the Crimean Khanate under the first Crimean khans outside the peninsula are determined from the eastern side by the Molochnaya River, and maybe expand further, to the Mius. In the north, on the left bank of the Dnieper, they go beyond Islam Kermen, up to the Horse Waters River. In the west, the Crimean nomad camps stretch across the Ochakov steppe to Belgorod to Blue Water.

In the north, on the left bank of the Dnieper, they go beyond Islam Kermen, up to the Horse Waters River. In the west, the Crimean nomad camps stretch across the Ochakov steppe to Belgorod to Blue Water.

Almost the same borders of the Crimean Khanate are indicated by a number of researchers, but Tunmann stands out among them, who even accompanied his work with a rather detailed map. In determining the more precise boundaries of the Crimean Khanate, the “Map of the Crimean Khanate after the Kyuchuk-Kainarji Peace of 1774-1783”, compiled and drawn by N.D., is of great importance. Ernst. Analysis of these data makes it possible to fairly accurately determine the boundaries of the Crimean Khanate. The territory of the Khanate was heterogeneous in terms of natural and climatic conditions. The northern slopes of the Crimean mountains, the valleys of Salgir, Alma, Kacha, Belbek with their orchards and vineyards, and finally, the steppes in the Crimea itself and beyond its borders created special, unique conditions for the development of the economy.

In addition to these geographical conditions, it is important to note that the Crimea was the country of the most ancient agricultural culture. The Tatars met here with a number of nationalities whose economic structure was determined by the centuries-old past. Some of the peoples of the Crimea - Greeks, Karaites, Genoese and others - became part of the population of the yurt; on the other hand, many Tatars settled in the Greek villages in the vicinity of Kaffa, Sudak, Balaklava and in these cities themselves.

Joint life, the beginning of the process of assimilation with the former population inevitably led to a change in the economic structure of the Tatars, nomadic pastoralists who found themselves in a region with ancient traditions of agricultural culture.

Socio-political structure of the Crimean Khanate

A characteristic feature of the socio-political structure of the Crimean Khanate was the preservation of tribal traditions for many centuries. A number of additional factors that accompanied the history of the Crimean Khanate also had a significant impact on all spheres of state life and, in particular, on the management system. To be on the Crimean throne, especially to rule in the Crimean Khanate, was far from an easy task. Each khan had to carefully weigh both his domestic and foreign policies, taking into account numerous nuances. It was necessary to deeply know the ancient traditions of their people, among which tribal relations were extremely significant.

A number of additional factors that accompanied the history of the Crimean Khanate also had a significant impact on all spheres of state life and, in particular, on the management system. To be on the Crimean throne, especially to rule in the Crimean Khanate, was far from an easy task. Each khan had to carefully weigh both his domestic and foreign policies, taking into account numerous nuances. It was necessary to deeply know the ancient traditions of their people, among which tribal relations were extremely significant.

Back in the 17th and even in the 18th century, the Tatars - both Crimean and Nogai - were divided into tribes, divided into clans. At the head of the birth were beys - the highest Tatar nobility, who concentrated in their hands significant wealth (cattle, land, pastures), captured or granted by the khans, and, at the same time, great power. Large yurts - the destinies (beyliks) of these clans, which became their patrimonial possessions, turned into feudal principalities, almost independent of the power of the khan, with their own administration and court, with their own militia.

The vassals of the beys and khans were one step lower on the social ladder - murzas (Tatar nobility). A special group was the Muslim clergy. The next step was occupied by the Tatar “simple” (without titles) population of the uluses, the step below was the dependent local population, and slave slaves were at the bottom step of the social ladder.

Thus, the tribal organization of the Tatars was a shell of relations typical of many nomadic peoples who preserved the traditions of their ancestors. Nominally, the Tatar clans, headed by beys and murzas, were in vassal dependence on the khans, in particular, they were obliged to field an army during military campaigns, but in fact the highest Tatar nobility was a full-fledged mistress in essence in all spheres of the life of the khanate. The dominance of beys, murz was a characteristic feature of the political system of the Crimean Khanate.

The main princes and murzas of the Crimea belonged to a few specific families. The oldest of them settled in the Crimea long ago and have been known since the 13th century. Which of them occupied a dominant position in the 14th century? There is no unanimous answer to this. First of all, the genus Yashlau (Suleshev), Shirinov, Barynov, Argynov, Kipchaks can be attributed to the oldest.

The oldest of them settled in the Crimea long ago and have been known since the 13th century. Which of them occupied a dominant position in the 14th century? There is no unanimous answer to this. First of all, the genus Yashlau (Suleshev), Shirinov, Barynov, Argynov, Kipchaks can be attributed to the oldest.

In 1515, the Grand Duke of All Rus' Vasily III insisted that Shirin, Baryn, Argyn, Kipchak, i.e., the princes of the main Tatar families, be singled out by name for presenting gifts (commemoration). The princes of these four families, as is known, were called "Karachi" (karach-bey). The institute of Karachi was a common phenomenon in Tatar life. In Kazan, in Kasimov, in Siberia, among the Nogai, the main princes were called Karachi. At the same time, as a rule, there were four karaches everywhere, with the exception of some cases.

But Karachi was not all equal in weight and importance. The most important was the importance of the first prince (bey), in essence, the second person in the state after the sovereign. We note the same concept among the Tatars. The position of the first prince in the Crimea was close enough to that of the khan.

We note the same concept among the Tatars. The position of the first prince in the Crimea was close enough to that of the khan.

The first prince also received the right to certain incomes, the commemoration had to be sent in such a way: two parts to the khan, and one part to the first bey.

As is known, the Shirinskys were the first among the beys of the Crimean Khanate. Moreover, beys from this clan occupied a leading position not only in the Crimea, but also in other Tatar uluses. At the same time, despite the dispersion over individual Tatar kingdoms, a certain connection, a certain unity, remained between the entire Shirinsky family, but Crimea is considered the main nest from which the family of these beys spread.

Shirinov's possessions in the Crimea stretched from Perekop to Kerch. Solkhat - Old Crimea - was the center of Shirinov's possessions.

As a military force, the Shirinskys were something united, acting under a common banner. The independent Shirin princes, both under Mengli Giray I and under his successors, often took a hostile position towards the khan. “And from Shirin, sir, the tsar does not live smoothly,” the Moscow ambassador stated in 1491. “And from Shirina, he had great strife,” note the ambassadors of the Moscow sovereign a century later. Such enmity with the Shirinskys, apparently, was one of the reasons that forced the Crimean khans to move their capital from Solkhat to Kyrk-or.

The independent Shirin princes, both under Mengli Giray I and under his successors, often took a hostile position towards the khan. “And from Shirin, sir, the tsar does not live smoothly,” the Moscow ambassador stated in 1491. “And from Shirina, he had great strife,” note the ambassadors of the Moscow sovereign a century later. Such enmity with the Shirinskys, apparently, was one of the reasons that forced the Crimean khans to move their capital from Solkhat to Kyrk-or.

The Mansurovs' possessions covered the Evpatoria steppes. The Beymis of the Argyn beys was located in the region of Kaffa and Sudak. The beylik of the Yashlavskys occupied the space between the Kyra-or (Chufut-kale) and the Alma River.

In their yurts-beyliks, the Tatar beys were absolute masters, this is also confirmed by the khan's labels (compliance letters).

As already noted, the beys and murzas largely limited the power of the Crimean khans: the heads of the most powerful clans - the karachis - made up the Divan (Council) of the Khan, which was the highest state body of the Crimean Khanate, where the most important issues of domestic and foreign policy of the state were resolved. The sofa was also the highest court. The congress of the khan's "vassals" could be complete or incomplete, and this did not matter much in its validity. But the absence of influential beys and, above all, the tribal aristocracy (karach-beys) could paralyze the implementation of the decisions of the Divan.

The sofa was also the highest court. The congress of the khan's "vassals" could be complete or incomplete, and this did not matter much in its validity. But the absence of influential beys and, above all, the tribal aristocracy (karach-beys) could paralyze the implementation of the decisions of the Divan.

Based on this, without the Council (Divan), the khan, in general, could not solve any issue. This is also confirmed by the reports of the Russian ambassadors to their sovereign: “Khan without a yurt (i.e. Divan - author) cannot do any great deed, about which it is necessary between states.”

The princes not only influenced the decision of the khan, but it was on them that the choice of the khans depended. Repeatedly as a result of conspiracies, the beys khan was overthrown from the throne. The beys of Shirinsky were especially "distinguished" in this. No less influential, but less privileged in the Crimea, was the Nogai clan of the Mansurovs (Mansur).

In favor of the beys and murzas was a tithe from all the cattle owned by the Tatars, and from all the booty captured during predatory campaigns, which were organized and led by the Tatar aristocracy, which also received significant income from the sale of captives.

The main activity of the service nobility was military, in the guard of the khan. The Horde was also a certain combat unit, headed by the Horde princes. Numerous lancers commanded the khan's detachments (an ancient Mongolian term was still applied to them - lancers of the right and left hands).

The governors of the cities were the same serving khan princes: prince of Kyrkor, Ferrik-Kermensky, prince Islam of Kermensky and governor of Ordabazar. The position of the governor of this or that city, as well as the title of prince, was transferred to members of the same family. Among the feudal lords close to the khan's court were also the highest clergy of the Crimea, which, to one degree or another, influenced the domestic and foreign policy of the Crimean Khanate.

Crimean khans have always been representatives of the Girey family. They had a very magnificent title: "Ulug Yortni, ve Tehti Kyrying, ve Desht and Kypchak, Ulug Khani", which respectively meant: "Great Khan of the Great Horde and the throne (state) of Crimea and the steppes of Kypchak. "

"

Before the Ottoman invasion, the Crimean khans were most often elected by representatives of the highest aristocracy, primarily Karach Beys. But since the conquest of the Crimea, the elections of the khan were extremely rare, this was already an exception to the rule. The High Porte appointed and dismissed khans depending on their interests. It was usually enough for the padishah, through a noble courtier, to send one of the Gireys, destined to be the new khan, an honorary fur coat, a saber and a sable hat, studded with precious stones, with a hatti sheriff, that is, an order signed with his own hand, which was read collected in the Divan karach- beys; then the former khan without grumbling (most often) abdicated the throne. If he decided to resist, then for the most part, without much effort, he was brought to obedience by the garrison stationed in Kaffa and the fleet sent to the Crimea. Deposed khans were usually sent to Rhodes. It seemed something extraordinary that the khan retained his dignity for more than five years. During the existence of the Crimean Khanate, according to V.D. Smirnov, 44 khans, but they ruled 56 times. There are other versions: in recent studies, it is most often noted that 48 khans occupied the Crimean throne, and they ruled 68 times (see chart-table). This means that the same khan was either deposed from the throne for some kind of offense, then again elevated to the throne with appropriate honors. So, Mengli-Girey I and Kaplan-Girey occupied the throne three times, and Selim-Girey became the “record holder”: he was enthroned four times. It also came to oddities: two khans - Dzhanibek-Girey and Maksud-Girey did not even have time to reach the Crimea after their appointment to the khan's throne, as they were already removed from the unoccupied throne.

During the existence of the Crimean Khanate, according to V.D. Smirnov, 44 khans, but they ruled 56 times. There are other versions: in recent studies, it is most often noted that 48 khans occupied the Crimean throne, and they ruled 68 times (see chart-table). This means that the same khan was either deposed from the throne for some kind of offense, then again elevated to the throne with appropriate honors. So, Mengli-Girey I and Kaplan-Girey occupied the throne three times, and Selim-Girey became the “record holder”: he was enthroned four times. It also came to oddities: two khans - Dzhanibek-Girey and Maksud-Girey did not even have time to reach the Crimea after their appointment to the khan's throne, as they were already removed from the unoccupied throne.

Gerai is the generic name of the dynasty of the Crimean khans (at present, the Russified version - Giray) has become more common.

There are a number of assumptions about the origin of the name of the first Crimean Khan. In particular, a version was put forward that the khan, forced to hide from his persecutors, found shelter with the shepherds and later, becoming khan, added Gerai (kerai - shepherd) to his name as a token of gratitude. It was also suggested that he took this name as a token of gratitude to his tutor. There are other versions: more convincing is the assumption that the future khan received the name from his parents after birth. This name was quite common, and its definition was very flattering - "worthy, correct." And the prefix Hadji appeared in Giray after he made a hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca (probably in 1419G.).

In particular, a version was put forward that the khan, forced to hide from his persecutors, found shelter with the shepherds and later, becoming khan, added Gerai (kerai - shepherd) to his name as a token of gratitude. It was also suggested that he took this name as a token of gratitude to his tutor. There are other versions: more convincing is the assumption that the future khan received the name from his parents after birth. This name was quite common, and its definition was very flattering - "worthy, correct." And the prefix Hadji appeared in Giray after he made a hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca (probably in 1419G.).

It is interesting to note that of the six sons of Hadji-Gerai (hereinafter referred to as Giray), only one, the youngest, Mengli, added his father's name to his name - Giray. In the future, all descendants inherited this name (including Azezar Giray, who lives in England and is, in essence, the heir to the Crimean khans).

I would like to highlight once again the most important factors that had a huge impact on the position of the highest position in the state-political structure of the Crimean Khanate. In order to present to a certain extent not only the enormous responsibility for the fate of his people, which was assigned to him, but also, to some extent, the tragedy of the position of the “highest position” in the state. At the same time, this situation led not only to tragedy in the fate of the Khan himself, but often the entire Crimean Khanate and its people.

In order to present to a certain extent not only the enormous responsibility for the fate of his people, which was assigned to him, but also, to some extent, the tragedy of the position of the “highest position” in the state. At the same time, this situation led not only to tragedy in the fate of the Khan himself, but often the entire Crimean Khanate and its people.

Such a factor as the election of the khan at kurultais (general gatherings) played a rather large positive value in the initial period of history, when the nobility, the beys could protect the interests of their clan, tribe, people. However, in the course of historical development, when the political and economic situation changed, a new time came with its new requirements, the system remained the same. And later, when the highest nobility defended, first of all, their interests, and not the people, their ambitions and whims, the khan became a “toy” in the hands of his own “vassals”. The situation became even more aggravated if unity disappeared among the beys, and the most powerful clans began to sort things out among themselves (in the Crimea, the Shirinsky and Mansurov clans were often at enmity). The enmity of the clans could continue for a long time, bringing great harm to both the state and the people. At the same time, the Crimean Khan had no real power to solve such problems.

The enmity of the clans could continue for a long time, bringing great harm to both the state and the people. At the same time, the Crimean Khan had no real power to solve such problems.

This or that bey (the Nogai were especially often “distinguished” in this respect), regardless of the interests of the state, with the prohibitions of the khan and even the Turkish sultan, raided the territory of the state with which the Crimean the khanate and Turkey concluded a peace or even an allied treaty. And neither the khan nor the sultan, in general, could cope with such an "anarchist bey".

The vassal dependence of the Crimea on Turkey did not contribute to the rise of the prestige of the Crimean Khan. Possessing, in fact, unlimited power, the Turkish sultan was not at all interested in the power of the Crimean Khanate, just as he was not interested in the independence of its khans. The main criterion for appointment to the khan's throne was not how successfully and skillfully the applicant would rule for his people and his state, but how useful and, most importantly, how obedient this khan would show himself to the Turkish sultan in the future.

As a result, very often, far from their homeland (somewhere in Persia), without any benefit to it, soldiers of the Crimean Khanate perished in wars endlessly waged by the Brilliant Porta.

So, paraphrasing, we can rightfully say: “You are heavy Giray's hat!” The khan's prerogatives, which he enjoyed even under Ottoman rule, included public prayer (khutba), i.e. offering to him "for health" in all mosques during the Friday service, commanding troops, minting coins, the value of which he often, in his own way discretion, raised or lowered, the right to establish fees and tax their subjects.

In addition to the khan, there were six higher ranks of state rank: kalga, Nuraddin, orbey and three seraskirs or Nogai generals Kalga-sultan - the first person after the khan, the governor of the sovereign. In the event of the death of the khan, the reins of government rightfully passed to him until the arrival of a successor. If the khan did not want or could not take part in a military campaign, the kalga took command of the troops. The residence of the kalgi-sultan was in Ak-Mechet (the territory of modern Simferopol), not far from the capital of the khanate - Bakhchisarai. He had his own vizier, his own divan-efendi, his own qadi, his court consisted of three officials, like the khan's. Kalga Sultan sat every day in his divan. This divan had jurisdiction over all crimes in the county, even if it was a death sentence. But the kalga had no right to make a final verdict, he only analyzed the process, and the khan could approve the verdict. Kalga Khan could appoint only with the consent of Turkey, most often when appointing a new Khan, the Istanbul court also appointed Kalga Sultan.

The residence of the kalgi-sultan was in Ak-Mechet (the territory of modern Simferopol), not far from the capital of the khanate - Bakhchisarai. He had his own vizier, his own divan-efendi, his own qadi, his court consisted of three officials, like the khan's. Kalga Sultan sat every day in his divan. This divan had jurisdiction over all crimes in the county, even if it was a death sentence. But the kalga had no right to make a final verdict, he only analyzed the process, and the khan could approve the verdict. Kalga Khan could appoint only with the consent of Turkey, most often when appointing a new Khan, the Istanbul court also appointed Kalga Sultan.

Nuraddin Sultan - second person. In relation to the kalga, he was the same as the kalga in relation to the khan. During the absence of the khan and kalga, he took command of the army. Nuraddin had his own vizier, his divan effendi and his qadi. But he did not sit in the Divan. He lived in Bakhchisarai and moved away from the court only if he was given an assignment. On campaigns he commanded small corps. Usually a prince of the blood.

On campaigns he commanded small corps. Usually a prince of the blood.

A more modest position was occupied by the Orbeians and the Seraskirs. These officials, unlike the kalgi-sultan, were appointed by the khan himself. One of the most important persons in the hierarchy of the Crimean Khanate was considered the Mufti of Crimea, or kadiesker. He lived in Bakhchisarai, was the head of the clergy and the interpreter of the law in all controversial or important cases. He could confuse the Cadians if they judge incorrectly.

Dictionary

Bei - the highest Crimean Tatar nobility.

Weights (Gerai) - the ruling dynasty of the Crimean khans.

Sofa - council of the highest nobility in the Crimean Khanate, the largest landowners (owned beyliks).

Murza - Crimean Tatar nobility (nobility)

Beylik - patrimonial land ownership of the highest Crimean Tatar nobility of the beys.

Mufti - in the Crimean Khanate - the head of the Crimean Muslims. Usually appointed by the Turkish Sultan.

Usually appointed by the Turkish Sultan.

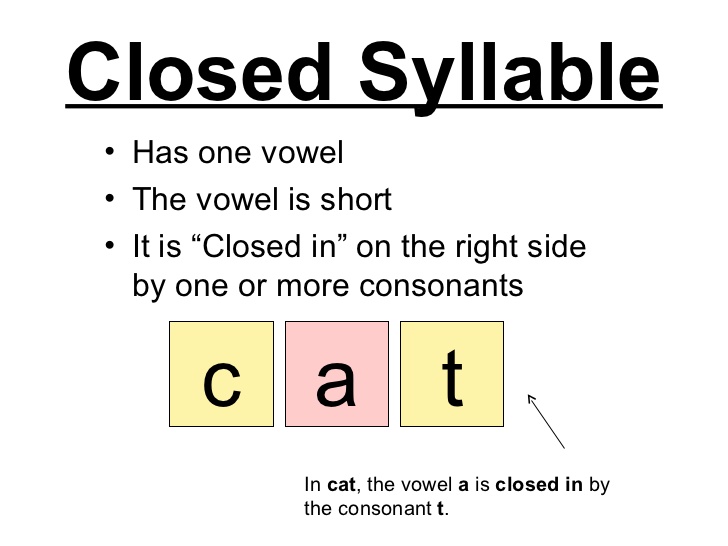

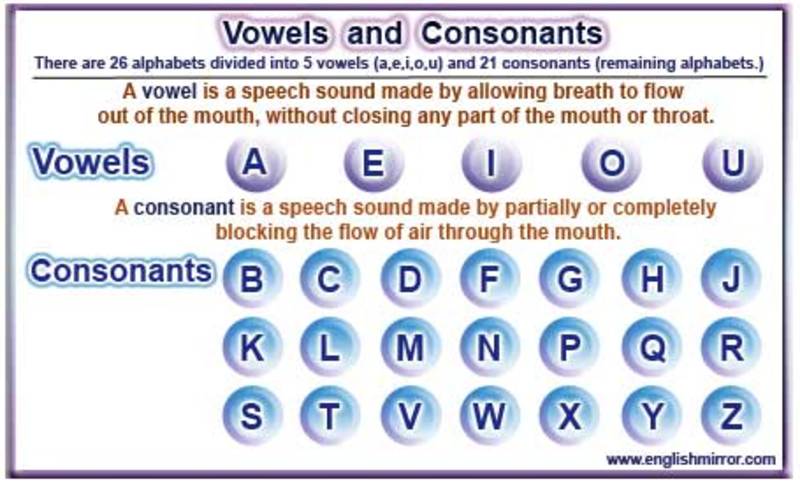

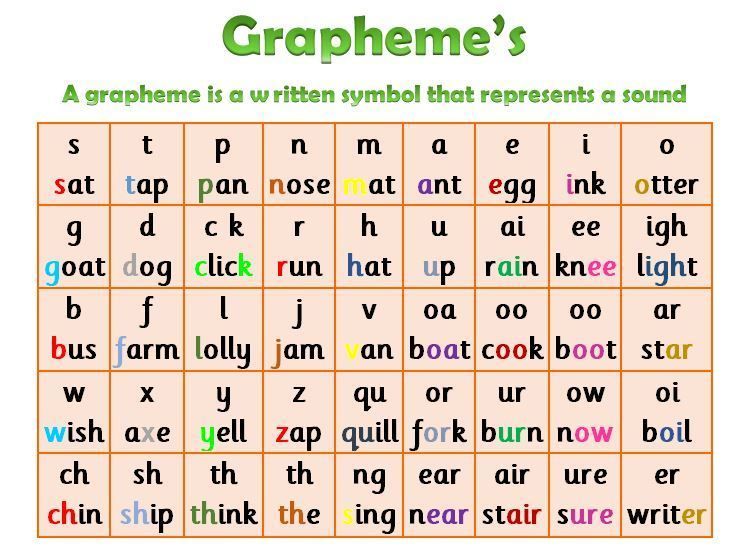

What is the difference between vowels and consonants and sounds? What rules do they follow? How is the hardness and softness of sounds and letters indicated? You will get answers to all these questions in the presented article.

General information about vowels and consonants

Vowels and consonants are the basis of the entire Russian language. Indeed, with the help of their combinations, syllables are formed that add up to words, expressions, sentences, texts, and so on. That is why quite a lot of hours are devoted to this topic in high school.

and sounds in the Russian language

A person learns what vowels and consonants are in the Russian alphabet from the first grade. And despite all the seeming simplicity of this topic, it is considered one of the most difficult for students.

So, in the Russian language there are ten vowels, namely: o, i, a, s, u, i, e, e, y, e. During their direct pronunciation, you can feel how the air passes through the oral cavity without any obstacles . At the same time, we hear our own voice quite clearly. It should also be noted that vowels can be pulled (ah-ah-ah-ah, uh-uh-uh, i-i-i-i-i, u-u-u-u-u and so on ).

At the same time, we hear our own voice quite clearly. It should also be noted that vowels can be pulled (ah-ah-ah-ah, uh-uh-uh, i-i-i-i-i, u-u-u-u-u and so on ).

Features and letters

Vowels are the basis of the syllable, that is, they organize it. As a rule, there are as many syllables in Russian words as there are vowels themselves. Let's give a good example: u-che-no-ki - 5 syllables, re-bya-ta - 3 syllables, he - 1 syllable, o-no - 2 syllables, and so on. There are even words that consist of only one vowel sound. Usually these are interjections (Ah!, Oh!, Woo!) and unions (and, a, etc.).

Endings, suffixes and prefixes are very important topics in the Russian language discipline. Indeed, without knowing how such letters are written in a particular word, it is rather problematic to compose a competent letter.

Consonant letters and sounds in Russian

Vowels and consonants, letters and sounds vary considerably. And if the former can be easily pulled, then the latter are pronounced as short as possible (except for hissing ones, since they can be pulled).

It should be noted that in the Russian alphabet the number of consonant letters is 21, namely: b, c, d, e, g, h, d, k, l, m, n, p, p, s, t, f, x, c, h, w, w. The sounds denoted by them are usually divided into deaf and voiced. What is the difference? The fact is that during the pronunciation of voiced consonants, a person can hear not only the characteristic noise, but also his own voice (b!, z!, p!, etc.). As for the deaf, they cannot be pronounced loudly or, for example, shouted. They create only a kind of noise (sh-sh-sh-sh-sh, s-s-s-s-s, etc.).

Thus, practically everything is divided into two different categories:

- voiced - b, c, d, e, g, h, d, l, m, n, r;

- deaf - k, p, s, t, f, x, c, h, w.

Softness and hardness of consonants

Not everyone knows, but vowels and consonants can be hard and soft. This is the second most important feature in the Russian language (after voiced and deaf).

A distinctive feature of soft consonants is that during their pronunciation, the human language takes on a special position. As a rule, it shifts slightly forward, and its entire middle part rises slightly. As for when they are pronounced, the tongue is pulled back. You can compare the position of your speech organ yourself: [n] - [n '], [t] - [t ']. It should also be noted that voiced and soft sounds sound somewhat higher than hard ones.

As a rule, it shifts slightly forward, and its entire middle part rises slightly. As for when they are pronounced, the tongue is pulled back. You can compare the position of your speech organ yourself: [n] - [n '], [t] - [t ']. It should also be noted that voiced and soft sounds sound somewhat higher than hard ones.

In Russian, almost all consonants have pairs based on softness and hardness. However, there are those who simply do not have them. These include hard - [g], [w] and [c] and soft - [y"], [h"] and [w"].

Softness and hardness of vowels

that in Russian there are soft vowels.Soft consonants are quite familiar to us sounds, which cannot be said about the above.Partly this is due to the fact that in high school there is practically no time for this topic.It is already clear with which vowels consonants become soft.However, we still decided to dedicate you to this topic.0005

So, those letters are called soft, which are able to soften the consonants going before them. These include the following: i, e, i, e, u. As for such letters as a, y, s, e, o, they are considered hard, since they do not soften the consonants going in front. To see this, let's give a few examples:

These include the following: i, e, i, e, u. As for such letters as a, y, s, e, o, they are considered hard, since they do not soften the consonants going in front. To see this, let's give a few examples:

Designation of the softness of consonants in the phonetic analysis of the word

The sounds and letters of the Russian language are studied by phonetics. Surely, in high school you were asked more than once to make a certain word. During such an analysis, it is imperative to indicate whether it is separately considered or not. If yes, then it must be denoted as follows: [n '], [t '], [d '], [in '], [m '], [n ']. That is, at the top right, next to the consonant letter in front of the soft vowel, you need to put a kind of dash. The following soft sounds are marked with a similar icon - [th "], [h"] and [w "].

Sounds belong to the phonetics section. The study of sounds is included in any school curriculum in the Russian language. Acquaintance with sounds and their main characteristics occurs in the lower grades. A more detailed study of sounds with complex examples and nuances takes place in middle and high school. This page only provides basic information. by the sounds of the Russian language in a compressed form. If you need to study the device of the speech apparatus, the tonality of sounds, articulation, acoustic components and other aspects that are beyond the scope of the modern school curriculum, refer to specialized textbooks and textbooks on phonetics.

A more detailed study of sounds with complex examples and nuances takes place in middle and high school. This page only provides basic information. by the sounds of the Russian language in a compressed form. If you need to study the device of the speech apparatus, the tonality of sounds, articulation, acoustic components and other aspects that are beyond the scope of the modern school curriculum, refer to specialized textbooks and textbooks on phonetics.

What is sound?

Sound, like words and sentences, is the basic unit of language. However, the sound does not express any meaning, but reflects the sound of the word. Thanks to this, we distinguish words from each other. Words differ in the number of sounds (port - sport, crow - funnel) , a set of sounds (lemon - firth, cat - mouse) , a sequence of sounds (nose - sleep, bush - knock) up to a complete mismatch of sounds (boat - boat, forest - park) .

What sounds are there?

Russian sounds are divided into vowels and consonants. There are 33 letters and 42 sounds in Russian: 6 vowels, 36 consonants, 2 letters (ь, ъ) do not indicate a sound. The discrepancy in the number of letters and sounds (not counting b and b) is due to the fact that there are 6 sounds for 10 vowels, 36 sounds for 21 consonants (if we take into account all combinations of consonant sounds deaf / voiced, soft / hard). On the letter, the sound is indicated in square brackets.

There are 33 letters and 42 sounds in Russian: 6 vowels, 36 consonants, 2 letters (ь, ъ) do not indicate a sound. The discrepancy in the number of letters and sounds (not counting b and b) is due to the fact that there are 6 sounds for 10 vowels, 36 sounds for 21 consonants (if we take into account all combinations of consonant sounds deaf / voiced, soft / hard). On the letter, the sound is indicated in square brackets.

There are no sounds: [e], [e], [yu], [i], [b], [b], [g '], [w '], [c '], [th], [h ], [sch].

Scheme 1. Letters and sounds of the Russian language.

How are sounds pronounced?

We pronounce sounds while exhaling (only in the case of the interjection "a-a-a", expressing fear, the sound is pronounced while inhaling.). The division of sounds into vowels and consonants is related to how a person pronounces them. Vowel sounds are pronounced by the voice due to the exhaled air passing through the tense vocal cords and freely exiting through the mouth. Consonant sounds consist of noise or a combination of voice and noise due to the fact that the exhaled air meets an obstacle in its path in the form of a bow or teeth. Vowel sounds are pronounced loudly, consonant sounds are muffled. A person is able to sing vowel sounds with his voice (exhaled air), raising or lowering the timbre. Consonant sounds cannot be sung, they are pronounced equally muffled. Hard and soft signs do not represent sounds. They cannot be pronounced as an independent sound. When pronouncing a word, they affect the consonant in front of them, make it soft or hard.

Consonant sounds consist of noise or a combination of voice and noise due to the fact that the exhaled air meets an obstacle in its path in the form of a bow or teeth. Vowel sounds are pronounced loudly, consonant sounds are muffled. A person is able to sing vowel sounds with his voice (exhaled air), raising or lowering the timbre. Consonant sounds cannot be sung, they are pronounced equally muffled. Hard and soft signs do not represent sounds. They cannot be pronounced as an independent sound. When pronouncing a word, they affect the consonant in front of them, make it soft or hard.

Transcription of a word

Transcription of a word is a recording of sounds in a word, that is, in fact, a recording of how the word is pronounced correctly. Sounds are enclosed in square brackets. Compare: a - letter, [a] - sound. The softness of consonants is indicated by an apostrophe: p - letter, [p] - hard sound, [p '] - soft sound. Voiced and voiceless consonants are not marked in writing. The transcription of the word is written in square brackets. Examples: door → [dv'er '], thorn → [kal'uch'ka]. Sometimes stress is indicated in transcription - an apostrophe before a vowel stressed sound.

The transcription of the word is written in square brackets. Examples: door → [dv'er '], thorn → [kal'uch'ka]. Sometimes stress is indicated in transcription - an apostrophe before a vowel stressed sound.

There is no clear correspondence between letters and sounds. In the Russian language, there are many cases of substitution of vowel sounds depending on the place of stress of a word, substitution of consonants or dropping out of consonant sounds in certain combinations. When compiling a transcription of a word, the rules of phonetics are taken into account.

Color scheme

In phonetic analysis, words are sometimes drawn with color schemes: letters are painted with different colors depending on what sound they mean. Colors reflect the phonetic characteristics of sounds and help you visualize how a word is pronounced and what sounds it consists of.

All vowels (stressed and unstressed) are marked with a red background. Iotated vowels are marked green-red: green means a soft consonant sound [y ‘], red means the vowel following it. Consonants with solid sounds are colored blue. Consonants with soft sounds are colored green. Soft and hard signs are painted in gray or not painted at all.

Consonants with solid sounds are colored blue. Consonants with soft sounds are colored green. Soft and hard signs are painted in gray or not painted at all.

Designations:

— vowel, — iotated, — hard consonant, — soft consonant, — soft or hard consonant.

Note. The blue-green color is not used in the schemes for phonetic analysis, since a consonant cannot be both soft and hard at the same time. The blue-green color in the table above is only used to show that the sound can be either soft or hard.

What yes letters and sounds in Russian? Which letters represent which sounds? What is the difference between soft and hard consonants? When is a consonant hard and when is it soft? Why do we need soft (b) and hard signs (b)?

Want to find answers to all these questions? Then read on!

Below you will find an interactive Russian alphabet with audio. For each letter [in square brackets], the sounds that it can stand for are indicated, as well as examples of words with this letter.

And here, for sure, you will immediately have two questions:

№1 Why do some letters have two sounds?

This is a feature of the Russian language. Some letters can represent two different sounds: a hard and a soft consonant. To clearly demonstrate this principle, I specially selected two examples for such letters: one with a hard consonant, and the other with a soft consonant.

#2 Why are no sounds shown for 'ь' and 'ъ'?

These are soft and hard signs. By themselves, they do not represent any sounds. They show us how to read the previous consonant: a consonant before a hard sign will be hard, and a consonant before a soft sign will be soft.

Also, sometimes we need to separate a consonant from a vowel, and for this we will write one of these signs between them. This is how we distinguish, for example, the words "seed" and "family".

What sounds can't a Russian pronounce?

What is good for a Russian is death for a German.

However, things are not so simple in linguistics, and this law also works in the opposite direction.

Almost in any language for Russians there are sounds that cannot be reproduced on the fly.

Some of them take months to master.

Traditionally, Chinese is considered the most difficult language. In practice, mastering pronunciation in it is not difficult for people with good hearing.

Of the sounds that our speech apparatus is not accustomed to making, in this language the most difficult sound is the sound "r" - something between "g" and "r".

Chinese is complicated, first of all, by its tones, which are from 4 to 9 (in Cantonese). There are even more tones in the Vietnamese language - about 18.

If we talk about European languages, in particular, about German, then the most difficult ones for a Russian person are ä, ö, ü. But it is not difficult to learn how to pronounce them, because in our speech there are words, during the pronunciation of which we involuntarily make similar sounds, for example, in the words "muesli" or "honey".

Beavers wandered along a log

French is a little harder to master with its nasal consonants and the "r" sound. What is the norm for France (elegant grading), Russian speech therapists are trying to fix.

In our country, people who were not able to pronounce a firm “r” were called burrs, and the tongue twister about a Greek who put his hand into the river, and about beavers on a log is one of the exercises designed to help in staging this sound.

In some dialects of German, this grazing also sounds, but more rolling - such as was used by the famous "French sparrow" Edith Piaf. In the English, the letter “r” is not pronounced at all, but is only indicated by a sound that is more similar, as in Chinese, to “g”.

East is a delicate matter

Oriental culture is very different from the Slavic, and the Semitic language family also differs sharply. For example, it has sounds that do not have exact analogues in Russian.

These include, in particular, guttural, pronounced not by the mouth, but by the throat. There are four of them in Hebrew, as well as in Arabic. On the territory of modern Israel, they were practically reduced, but among those Jews who were born in Arab countries, they are found.

There are four of them in Hebrew, as well as in Arabic. On the territory of modern Israel, they were practically reduced, but among those Jews who were born in Arab countries, they are found.

The same can be said about some Caucasian languages with their guttural sounds, for example, Adyghe, Chechen, etc. You can imagine these sounds if you remember going to the lore. The very “a” that he makes us say, pressing the root of the tongue with a spatula, is precisely guttural.

The sharpness of the sound of Arabic speech, which seems to many Slavs not very melodic, is due to the presence of such throat sounds.

Interdental sounds, in which the tip of the tongue is located between the upper and lower teeth, are also unusual for Russian people, but they are present in some European languages, for example, in English.

It is also very difficult to pronounce the Arabic back-lingual, also found in the languages of the northern peoples. The famous Baikal is the Yakut Baigal changed by the Russians for the convenience of pronunciation, where the “g” is just back-lingual.

Dust flies across the field from the clatter of hooves

Onomatopoeia of the clatter of horse hooves and clicking of the tongue is just entertainment for Russian people. But there are peoples for whom such sounds are the speech norm. Those who watched the film "The Gods Must Be Crazy" remember how one of the main characters and all his Aboriginal compatriots spoke a language that sounds very strange to us.

Khoisan languages. They are spoken by only about 370,000 people in southern Africa and Tanzania. They are distributed mainly among the inhabitants of the area surrounding the Kalahari Desert. These languages are gradually dying out. The clattering consonants are called "klixes", and their number sometimes reaches 83. In addition to the Khoisan languages, klixes are also found as the main constituents of speech in Bantu and Dahalo.

With the desire and patience, a Russian person can master any language, including Khoisan. It's just a matter of time.