When do kids learn to share

Sharing is Caring…AND a Developmental Milestone

Before we begin our discussion on sharing, I thought we could spend some time exploring developmental milestones. I know this might seem a little off topic, but I promise this all connects to sharing. Let’s start with what comes to your mind when you think about milestones that infants and toddlers achieve. You might imagine an infant learning how to take their very first steps or a young child learning to use the potty all on their own. There are so many wonderful milestones that parents look forward to, but one milestone that is often forgotten is learning to share. Child development specialists tell us that learning to take turns is considered a social milestone (Healthy Families British Columbia (HFBC), 2017).

So, what does this mean exactly? Well, just like infants cannot learn to walk until they are physically ready, children cannot learn to share until they are socially ready. This means it is completely normal for a two-year-old to swoop all their toys into their arms and shout, “No! Mine!” when they see another toddler approaching their toys. In fact, it is a part of typical social development for children to struggle with sharing. Toddlers might even push or grab to protect their toys and announce that they are not interested in sharing (HFBC, 2017). As odd as it might seem, parents can view these types of behaviors as a social milestone for toddlers.

As some of you read this, you might be thinking, “Even if sharing is a milestone, I can still help my child learn to share.” You are exactly right. Parents play a crucial role in showing their toddlers HOW to share. However, if you are a parent or have worked with children, you understand how challenging it can be to help a toddler learn a new skill, especially if they are not ready. Imagine a child who begins toilet teaching before they are ready. They might have lots of accidents, forget to tell someone they have to potty or simply be confused by the process of having to use the toilet. In this instance, parents might decide to try supporting their child with potty training when they are a little older and more ready. Sharing is much like toilet teaching in that until a child is ready to share, they will probably be confused with the idea.

Sharing is much like toilet teaching in that until a child is ready to share, they will probably be confused with the idea.

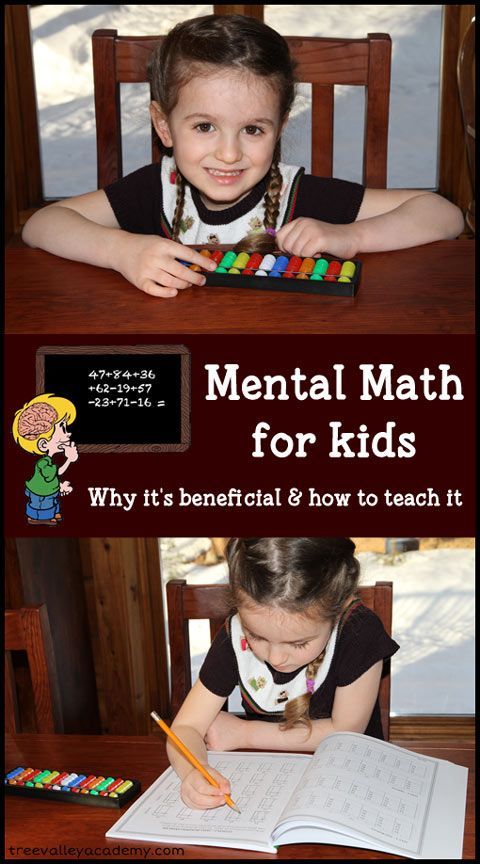

Of course, parents can still begin building the foundation for sharing if they understand when children will be able achieve the idea of taking turns. Let’s jump into this research and learn about when the experts say children can understand HOW to share. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) (n.d.), tells us that children who are younger than 3 CANNOT understand the idea of sharing. In fact, child development specialists explain that sharing skills usually do not appear until around 3.5 to 4 years of age (MacLaughlin, 2017). So, why is that toddlers cannot share?

When I started researching this topic, I learned there are a few reasons that toddlers struggle with sharing. According to Lindert (2012), toddlers lack the ability to SAY what they want. Toddlers are also still developing their independence, which means they are learning how to make decisions. Let’s start with the language piece of this information. Around the developmental age of 18-24 months, children can begin using two to three word sentences. (HFBC, 2017). This is a huge milestone for toddlers but being able to form only very short sentences creates a barrier for children when it comes to sharing.

Let’s start with the language piece of this information. Around the developmental age of 18-24 months, children can begin using two to three word sentences. (HFBC, 2017). This is a huge milestone for toddlers but being able to form only very short sentences creates a barrier for children when it comes to sharing.

Let’s imagine a scenario to better understand how sharing and language development are connected. Picture a two-year-old named Carter who proudly walks into daycare with their new stuffed bear. Little two-year-old Lucy sees the bear and shouts, “Me want it!” Carter of course does not want to just give Lucy the new bear, so Lucy begins to pull the bear from Carter’s hands as Carter screams, “No! My bear!” This seems like a typical interaction that we have all probably witnessed before. In this scenario, the children could only use three-word sentences. Even though adults are used to using complex sentences to explain what they need, we forget toddlers cannot do this quite yet. This means they do not have the language ability to talk about how to share things like a new stuffed animal.

This means they do not have the language ability to talk about how to share things like a new stuffed animal.

As mentioned before, Lindert (2012) also reminds us that toddlers are learning how to be independent. Toddlers are now able to make some of their own choices, like which toy they want to play with. However, they are not able to understand that all their friends do not share the same viewpoint as them. This means that little Lucy believed that EVERYONE, including Carter should have understood how badly she wanted the bear. You might be asking yourself why toddlers assume everyone knows how what they are thinking and feeling…this is a great question.

Child development specialists tell us that young children are still learning about empathy, which means they do not have the ability to try to understand others’ feel. (MacLaughlin, 2017). This means that Carter and Lucy could not step into each other’s shoes and ask one another how the stuffed bear made them feel. Instead, they could only focus on their own feelings. It can be overwhelming for parents to learn that their toddlers are still developing empathy skills. However, parents can be assured that there are still things they can do to help their toddlers learn how to share as they grow older.

It can be overwhelming for parents to learn that their toddlers are still developing empathy skills. However, parents can be assured that there are still things they can do to help their toddlers learn how to share as they grow older.

Some of the things that parents can try are:

• Intervene when your child expresses aggression. For example, if your child hits another child during their playdate because they didn’t want to share a toy, you can use a calm voice and say something like, “Hitting is not allowed.”

• Embrace parallel play. This is a type of play where children play beside each other, without interacting with each other. Toddlers enjoy parallel play and it’s a simple way to allow children to play with their own toys, while enjoying each other’s company.

• When toddlers do play together, encourage activities that do not involve a lot of toy sharing such as dancing to music together or playing games like hide-and-seek.

• Allow your child to have a long turn with a toy. Remember toddlers are still learning about empathy, so they cannot understand why another child would also like to play with the same toy that they are using. Parents can support other children by redirecting them to another activity until their child is done playing with the toy.

Remember toddlers are still learning about empathy, so they cannot understand why another child would also like to play with the same toy that they are using. Parents can support other children by redirecting them to another activity until their child is done playing with the toy.

(AAP, n.d & MacLaughlin, 2017)

I hope that these tips provide you with some guidance on how to help build the foundation for toddlers beginning to share. If you are someone who uses the Growing Great Kids Curriculum, please know that there are some additional resources that you may use to support parents with conversations around sharing. You might explore the subsection, E-Parenting and other Tips for Challenging Situations, located in the 13-15 Months Social and Emotional Development module, which talks in more detail about why toddlers cannot share. You may also utilize the 22-24 Months Social and Emotional Development module, which addresses topics like sharing and parallel play.

I thank you for taking time to read about toddlers and how to support them with sharing.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. (n.d.). Teaching kids to share. Retrieved from

https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/aap-press-room-

media-center/Pages/Teaching-Kids-to-Share.aspx

Healthy Families British Columbia. (2017). Toddler’s first steps a best change guide to

parenting your 6-to-36-months old child. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.

bc.ca/library/ publications/year/2017/ToddlersFirstSteps-Sept2017.pdf

Lindert, R. (2012). That’s mine! Scholastic Parent & Child, 19, 62. Retrieved from

https://search.proquest.com/docview/1021412249?accountid=196176

MacLaughlin, S. S. (2017, August 11). Helping young children with sharing. Retrieved from

https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/1964-helping-young-children-withsharing

An age-by-age guide to teaching your child to share

Toddler 1: “Nooooooo, it’s mine!”

Toddler 2: “I want it!”

How many parents have ever heard that scenario?

(I’d be surprised if any of you haven’t. )

)

And how many parents are sick of hearing it?

(I’d be surprised if any of you who have more than one child aren’t…)

Young children find sharing difficult!

We know that children develop the mental skills needed to engage in sharing behavior over time, and yet we find ourselves in a pickle over sharing all the time. Our own children take things from each other. Our child takes something from another child at preschool. Someone else’s child takes something from our child at the park.

When it’s just our own children at home, we might just step in and say: “Well if you can’t stop fighting over it, I’m just going to take it away so neither of you can have it.” In a public place, we immediately find ourselves getting hot and anxious not because of the children, but because of what the adults around us will think of our children – and, by extension, our parenting.

Being judged is hard, right?

So how should we handle these types of situations?I like to firstly take a step back and look at our overall goals, and then understand what is developmentally appropriate by age.![]()

Western parents are usually trying to socialize their children to be liked by others, and adults see this sharing behavior as an indication that their child will be liked. We also want them to share with others spontaneously, of their own volition: because we (in our society) think it’s the right thing to do, and not just because someone is telling them to do it.

Parents in different cultures use a variety of approaches at home to encourage sharing. In cultures where individualism is less pronounced and members of society are interdependent, parents may state that there are no privately owned toys: all toys belong to all the children in a household.

Teachers in Japanese preschools may start the school year with several of a usually-favored toy, and over the course of a few months they withdraw some of these to ‘force’ children to figure out arrangements to share the toys.

At the more individualistic-oriented end of the spectrum, parents who subscribe to the Resources for Infant Educarers (RIE) approach to parenting might have separate gated areas within their house where children spend some portion of the day when they are not actively supervised.

When the children are in the same space the parent is close by, narrating what the children are doing during tricky situations: “Maria, you’re playing with the truck. Nate would like to play as well. When you’re done with the truck, please let us know because Nate is waiting.” Maria might continue to play with the truck for some minutes but quite often she will voluntarily offer the truck to Nate sooner than you might expect, because there was no pressure on her to share and she was able to do it while saving face.

We should also acknowledge that, most of the time, we say “sharing” when we don’t really mean it: children are “sharing” when they split a banana or a cookie. “Sharing” a toy really means “giving up the thing you have and really want to keep to someone else” – a concept that young children can find confusing, which naturally leads to resistance. Using the phrase “taking turns” rather than “sharing” can help a child what is expected of them much more easily. “Taking turns” helps the child to see that they will get the toy back again.

Any discussion of sharing by age will, of course, depend on your child’s own temperament, experience with sharing, and development. So feel free to ‘size up’ or ‘size down’ depending on your child’s own abilities and experience.

Before age ~3

Very young toddlers do not understand the concept of sharing very well. Some studies have found that a child as young as 10-12 months will bring toys or offer food to parents in apparent acts of sharing, but they are likely seeking a positive reaction or approval from the parent, or it may be part of how the two play together, or they might even be trying to keep a toy away from a sibling. Many children will hold out an object as if to share it and then withdraw it, as they test what happens during social interactions.

By around age two, children can usually understand the concept of ownership and will protest their own toys being taken away more than neutral toys. But they have very little understanding of how others think: they don’t know that the other child doesn’t know they want the toy if they don’t ask, which is why you find yourself in the following exchange:

“I want the toy! Johnny won’t give it to me!”

“Well, did you ask him for a turn?”

“Noooooooo…”.

Parents’ tasks at this age focus around modelling sharing behaviors: “I’m going to have a cookie. Would you like to share it with me?” or “You have a lot of toys there. Would you mind if I use it now, please? Thanks! We’re sharing!”

You can set your child up for success by not taking favorite toys to playdates (and by putting these away for playdates at your house), and by playing in natural areas where there are lots of “toys” (sticks, rocks, sand, and the like).

Outside of situations where sharing is required, you can support the development of these capabilities by encouraging your child to name their own feelings and the feelings of other people and characters in books. Many young children can recognize facial expressions but may not understand what emotions go with those expressions. Their vocabulary around emotions might initially be limited to “happy” and “sad,” so introduce them to the names for other emotions as well (use an emotion wheel if you have trouble naming/remembering these yourself).

Importantly, parents are NOT telling children to share, or forcing one child to give up an item so another child can play with it. This just teaches children that a strong person can force a smaller person to give something up, which isn’t the lesson we want them to take from this interaction.

In a public place, sit close to the children to block any hits that may occur and talk them through what you see (without judging either child).

Age ~3 to ~5

Around this age children become much more interested in playing together rather than ‘parallel playing’ next to each other, so sharing suddenly becomes relevant: a child who doesn’t share might find that their friend doesn’t want to play with them again tomorrow. Children are also starting to develop the capability to understand what others think and want, and can take a short break from their own play to consider that another child might want the toy they currently have.

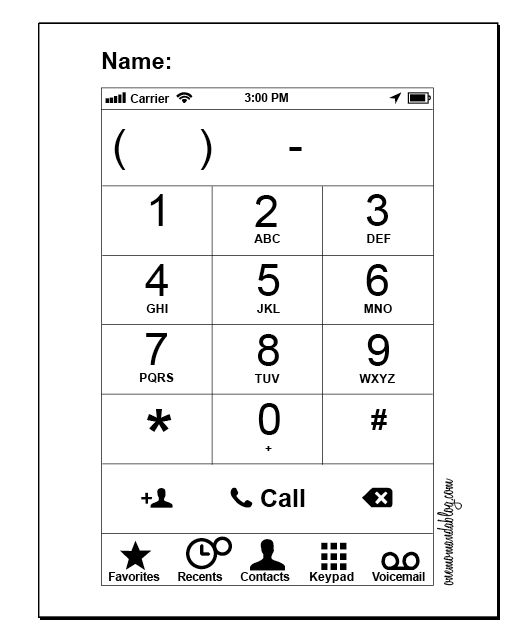

Their concept of time is evolving over this period too; at around age 3 they might still be focused entirely on the present and cannot foresee “five minutes from now” when they can have the toy. You can scaffold this knowledge by being honest about time: don’t say you’ll be there “in a minute” or “in just a sec” when you know it’s actually going to be at least five: say “I’ll be there in five minutes, which is when the big hand on the clock reaches the four.”

You can scaffold this knowledge by being honest about time: don’t say you’ll be there “in a minute” or “in just a sec” when you know it’s actually going to be at least five: say “I’ll be there in five minutes, which is when the big hand on the clock reaches the four.”

They are also developing some impulse control: the ability to wait and not just grab what they want, which is an enormous help with sharing. Parents can scaffold this ability by empathizing: “I know you want to play with the truck. Maria has it right now. It can be hard to wait. When Maria has finished, you can have the truck.” You can also suggest other toys the child might want to play with while they are waiting.

By this time the child might have a new sibling and you may find you need new strategies to deal with sharing than you had used with an only child. You may decide that all toys belong to everyone, or each child has a special few toys that they keep aside, or (if the age difference is pronounced) that small toys need to be kept away from baby and large toys are fair game for anyone as long as they aren’t currently being used. Decide on the rule that fits best with your overall parenting philosophy, but once you pick it, try to stick with it. Children have trouble when the rules change often or are rarely enforced.

Decide on the rule that fits best with your overall parenting philosophy, but once you pick it, try to stick with it. Children have trouble when the rules change often or are rarely enforced.

You can begin to scaffold the development of sharing strategies: things like taking turns, setting a timer, playing with another toy while waiting, and playing with the toy together. In the beginning you might need to suggest these strategies but over time, children will use these by themselves and will develop their own strategies too.

It’s important that the children involved agree to the strategies, rather than having you (or the older/bigger child) impose them, so the smaller/younger child gets to understand that their needs are important too. The child who has the toy should also have the option to say “I’m using this right now. I don’t want you to play with it.”

In public places, where a conflict between children is brewing, you might ask the other parent “Are you OK with letting them work it out by themselves?”

Age 5+

Hopefully by this age you’re starting to reap the benefits of the work you’ve put in thus far as the children becomes more able to use the skills you’ve been working on by themselves. The child may have a few very special possessions that they don’t want others to play with – special Lego structures, for example – which works in most families as long as there’s enough Lego to go around. We all have one or two special things that we don’t like other people to use, and children are no exception.

The child may have a few very special possessions that they don’t want others to play with – special Lego structures, for example – which works in most families as long as there’s enough Lego to go around. We all have one or two special things that we don’t like other people to use, and children are no exception.

If you’re still not seeing sharing behavior by this point, it might be time to step in with some new tools. You could role-play with your child: play alongside them, and when they ask you if they can use something that’s already in your hands, say ‘No, I’d like to keep playing with it.’ Then talk about how the child feels, and how their friend probably feels in a similar situation.

You might be tempted to praise “good sharing” when you see it, but a whole host of research tells us this is a bad idea: children are less likely to engage in an activity again after being praised for it, and are especially less likely to do the activity spontaneously (i.e. without first looking around to see if a suitable adult is watching). If you feel you need to reinforce the benefits of sharing, focus on the impact on the other child: “Carly looked so happy when you gave her the toy! She waited so patiently, and you gave it to her right when the timer went off, just like you said you would.”

If you feel you need to reinforce the benefits of sharing, focus on the impact on the other child: “Carly looked so happy when you gave her the toy! She waited so patiently, and you gave it to her right when the timer went off, just like you said you would.”

Most of all, have confidence that your child will learn to share when they are ready!

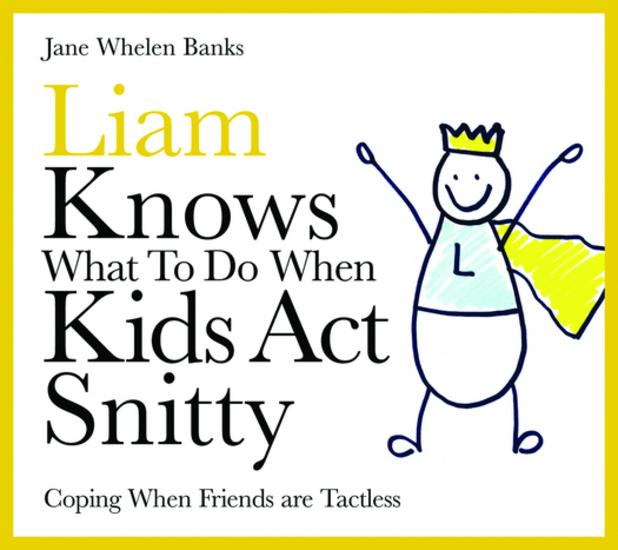

For a deeper dive on sharing, check out my podcast episode on this topic and also the excellent booklet “The Secret of Toddler Sharing: Why sharing is hard and how to make it easier.” It’s just 36 pages long and is packed with strategies like the ones I’ve outlined here that you can put to use immediately.

Want to get updates when I write these blog posts, that are lighter on the research than the podcasts but still packed with actionable strategies? Sign up below!

About the author, Jen

Jen Lumanlan (M.S., M.Ed.) hosts the Your Parenting Mojo podcast (www.YourParentingMojo.com), which examines scientific research related to child development through the lens of respectful parenting.

Should a child share toys?

Recently received the following letter:

“Hello. One problem worries me: I have two children - a 4-year-old boy and a 2-year-old girl.

The brother constantly offends his sister, is greedy, does not give toys, he has a favorite car that he drives at home, and so he does not allow her to even sit on it, let alone ride.

I understand that she is now of such an age that she is interested in everything. But how to explain to your son that you need to share with everyone, and not be greedy. After all, at home you explain to him that being greedy is not good, but he still continues to yell: This is mine! Do not touch!

I am the only one who takes care of their upbringing, dad is rarely at home and does not try to take care of them. Advise how to improve the relationship of children with each other?

This is a very good question that prompted me to write this article.

Is the child "greedy"? Let's figure it out

Often parents have an attitude that a child should definitely share his toys, and if he does not do this, then he is greedy.

Although, when it comes to us adults, it would be strange if someone told us that we should share with other people, for example, our mobile phone, wallet, computer, favorite cup, jewelry, car, or we are greedy!

Sounds funny, doesn't it?

The fact is that for a child his personal toys are the same value as our personal belongings are for us. He, just like an adult, has the right not to want to share his personal belongings with other people, including members of his family. This right must and must be respected.

I don't mean now the situation where you have to share the last piece of cake with your family or share the leftover soup or share other things that are meant for everyone. Now I mean exactly the personal things that are bought, donated to the child, and he has the right to decide how to deal with them.

What about older and younger children in the family?

When parents insist that older children share toys and other personal things with younger children, and even more so their favorite things, this definitely leads to jealousy between them.

The older child is very offended that the mother does not understand his feelings and takes the side of the younger one, taking his need for a toy more seriously than the older child's need to establish his personal boundaries and a sense of ownership.

You need to be calm about the fact that children do not want to share with each other and explain to them that each of them has the right to dispose of their toys as they want:

“This is your brother’s toy and he does not want to share it, it is his right. You also have your toys, you can share them whenever you want and with whom you want.”

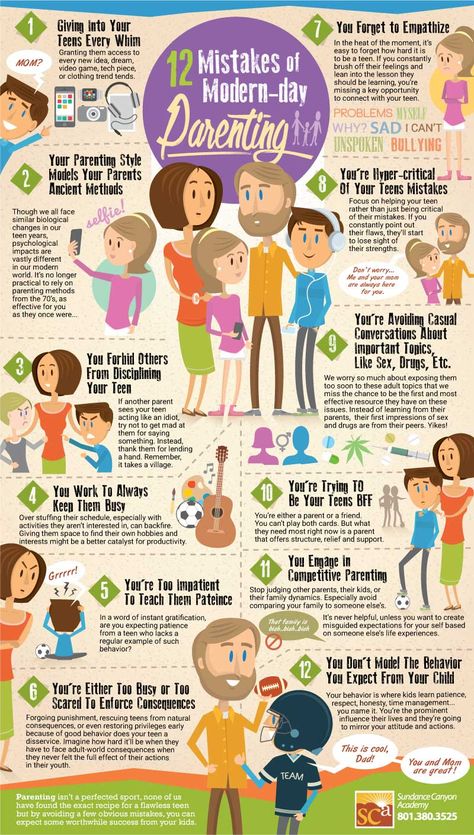

Children who are taught to share with everyone and cannot say “no” grow into adults who try to please others all the time and everywhere, cannot say “no”, do not know how to defend their interests and often act to their own detriment because they are brought up so that their feelings and needs mean nothing.

Or, on the contrary, compensating for what was not received in childhood, an adult will be unnecessarily stingy where it is necessary to give and share.

Recommendations for parents with several children in the family

1. In addition to common toys, each of the children must have their own toys.

2. It is desirable that new toys for children be bought at the same time (if this is not timed to coincide with the birthday). If something is bought to one, then the other also has something of his own (according to interests).

3. Each child should have a place in the room for their toys: their own shelf, their own container, their own box or corner.

4. It is necessary to explain to children that they can play together with common toys at any time, but they cannot touch and take each other's toys without asking. Children must learn to respect the other person's property and respect their right to say no.

5. It is important to teach a child to ask another child correctly and politely for permission to play with his toy or change temporarily.

It is also important to teach children to respect rejection. Say: “Sometimes you don't want to give out your toys either. It happens. You need to be able to respect the desire of another person.

6. If one toy is given to both children and there is always a division around it, help the children come up with some kind of schedule for using this toy: Monday, Wednesday, Friday - one plays as much as he wants, Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday - the other . You can hang such a schedule on the wall in the children's room (for older children).

Or you can come up with other options, but they must be fair and no one should be offended. No need to make a concession to someone who is younger. Both children have the same right to play with this toy, regardless of age.

(In the situation that Natalya describes, I, as a child psychologist, would advise you to buy a similar car for your youngest daughter, or instead of a car, something that you can also ride. Arrange with the older child so that he rides in another room or hallway, not in front of my sister.)

Arrange with the older child so that he rides in another room or hallway, not in front of my sister.)

7. Never label a child as “greedy”, it is very insulting and humiliating. It is as if you are saying to the child: “Not wanting to give another person your favorite thing is shameful and bad. You should!". Immediately think of yourself in a situation where you are asked to use your phone, computer or wear your favorite clothes. And if you refuse, they will say that you are a dishonorable person.

Conclusions

Be calm and understanding when your children do not want to share toys with each other. This is normal and does not mean that something is wrong with the children. Each child should have their own personal belongings and the opportunity to dispose of them at their own discretion.

Children should be taught to ask permission to play with another child's toys, to negotiate, to exchange toys, but also to respect the other's right to refuse. In a word, be polite and respect the boundaries of another person, regardless of his age, gender and other qualities.

P.S. If you liked this article, please share with your friends by clicking on the social media buttons on the left. And, as always, I welcome your comments and questions below.

See also:

Should a child be taught to share?

Author of article Kravtsova Elena Mikhailovna

7638 views

Just now your child was peacefully playing with another kid in the sandbox, and you were enjoying a warm day, rare for late autumn, when suddenly his bitter cry cuts the air. What happened? It turns out that the boy with whom they just made Easter cakes took his favorite scoop. The mother of the “opponent” persuades your sobbing child: “Well, for a minute, what are you sorry for?”. Familiar?

Familiar?

About whether it is necessary to teach the baby to share, we talked with a child psychologist Elena Mikhailovna Kravtsova .

Where does what come from?

At about 1.5 years old, many children shock their parents for the first time with their stinginess, they do not want to share with anyone. If they try to take away a toy, kids fight, scream or silently run away from peers who encroach on their property. Why is this happening?

The fact is that babies do not have an idea of \u200b\u200btime, so the argument “another child will play and give it back” does not work. For a baby, there is only “here and now”, and if someone takes his car, for a small owner it is “forever”.

This is normal!

Unwillingness to share is a sign of the normal development of the child. Children have different temperaments, so for some it will be stronger, for others it will be weaker. In any case, we must remember that “no” uttered by a child is a way to “defend” one’s independence, to declare oneself as a person. What adults might describe as greed is actually a normal sense of ownership. The kid begins to realize that he is a separate person and there is something in the world that belongs only to him. Children perceive their things as part of themselves. Therefore, the reluctance to share is just a completely desirable phenomenon in childhood.

What adults might describe as greed is actually a normal sense of ownership. The kid begins to realize that he is a separate person and there is something in the world that belongs only to him. Children perceive their things as part of themselves. Therefore, the reluctance to share is just a completely desirable phenomenon in childhood.

We respect the word "no" spoken by a child

Learning to say “no” is like learning to feel important. This ability is the key to high self-esteem and self-respect. All this develops only when others respect the feelings and interests of the child, do not try to “break” him.

What should parents do?

The main thing that can be advised is not to force children to share. It is better to calmly explain to the surrounding children that your baby has not played enough himself yet and is not ready to give his car or doll.

In no case should you insult or ridicule the little "miser", and even more so - take away his toy and give it to another child, even if it is a brother or sister. Remember: the more adults "pressure" on the baby, the less he wants to share.

Remember: the more adults "pressure" on the baby, the less he wants to share.

The wisest parental tactic during this period is to be sympathetic to the feelings of the child, while explaining to him what others are experiencing. “Vitya so wants to drive your truck, he probably never saw such a car. He'll be so upset if he doesn't get to play with that truck. Look how upset he is already."

The main task of parents is to gently, without violence, awaken a sense of empathy in the baby, make him want to share and make sure that his own interests are not infringed. If the baby refuses to empathize, do not insist. He's just not ready for this yet.

Be on the child's side

If another child's mother insists that your child share a toy, you should be politely firm. You can answer like this: “Unfortunately, my baby is not yet ready to share, he himself has not yet played enough.” And at the same time, you need to keep the thought in your head: “This is his full right.