Why is emergent literacy important

ABC’s of Early Literacy: The importance of developing early literacy skills

Carrie Shrier, Michigan State University Extension -

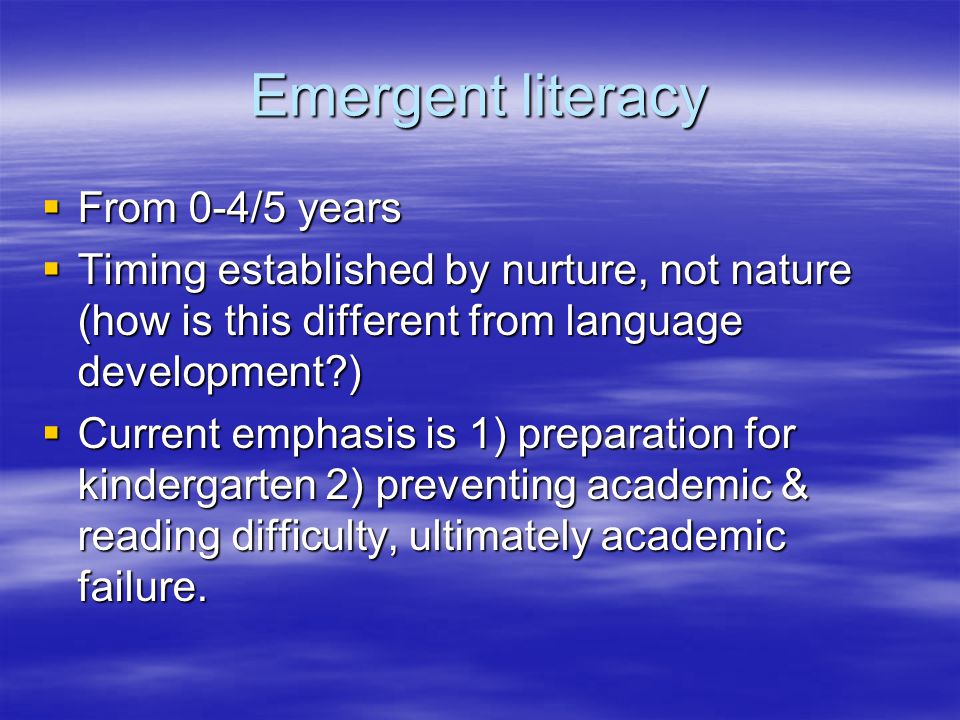

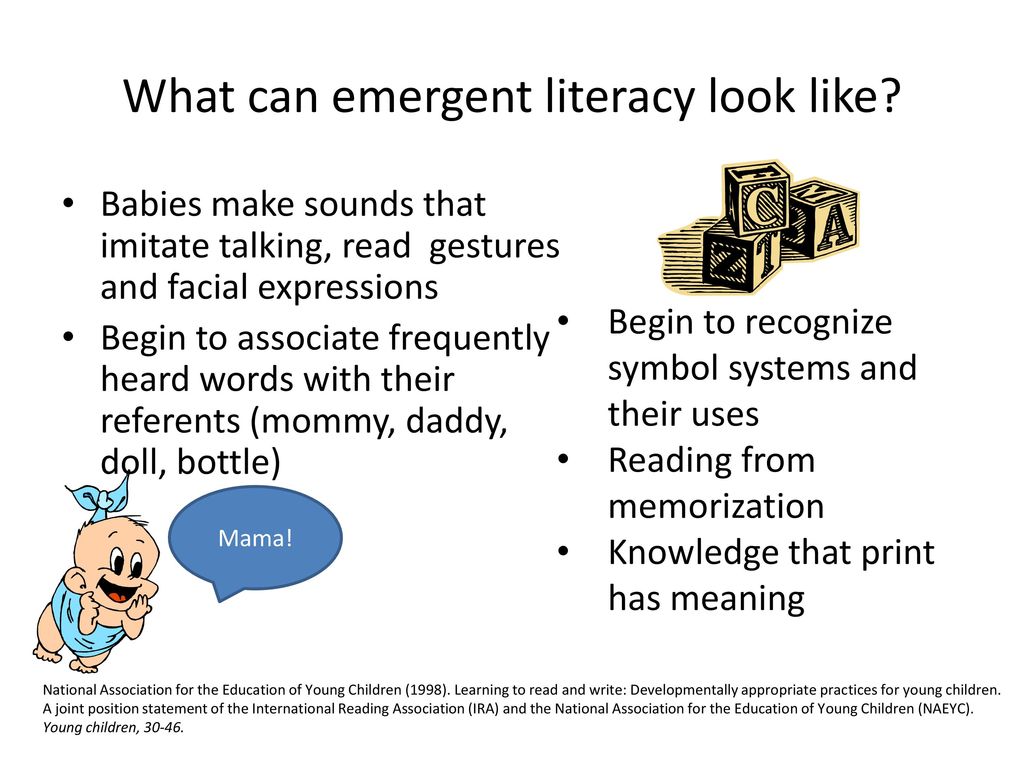

Emergent literacy, or reading readiness, skills begin to develop very early in life. These critical school-readiness skills go beyond knowing the ABC’s. Learn more about how to support your children’s reading readiness and school success!

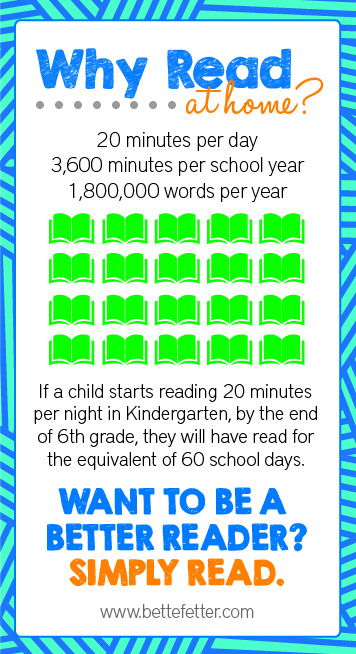

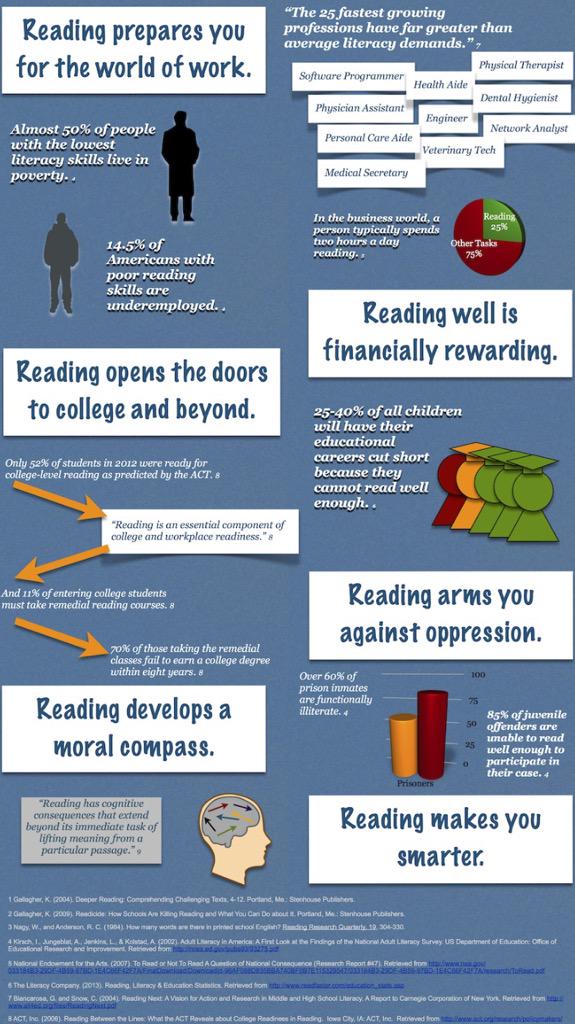

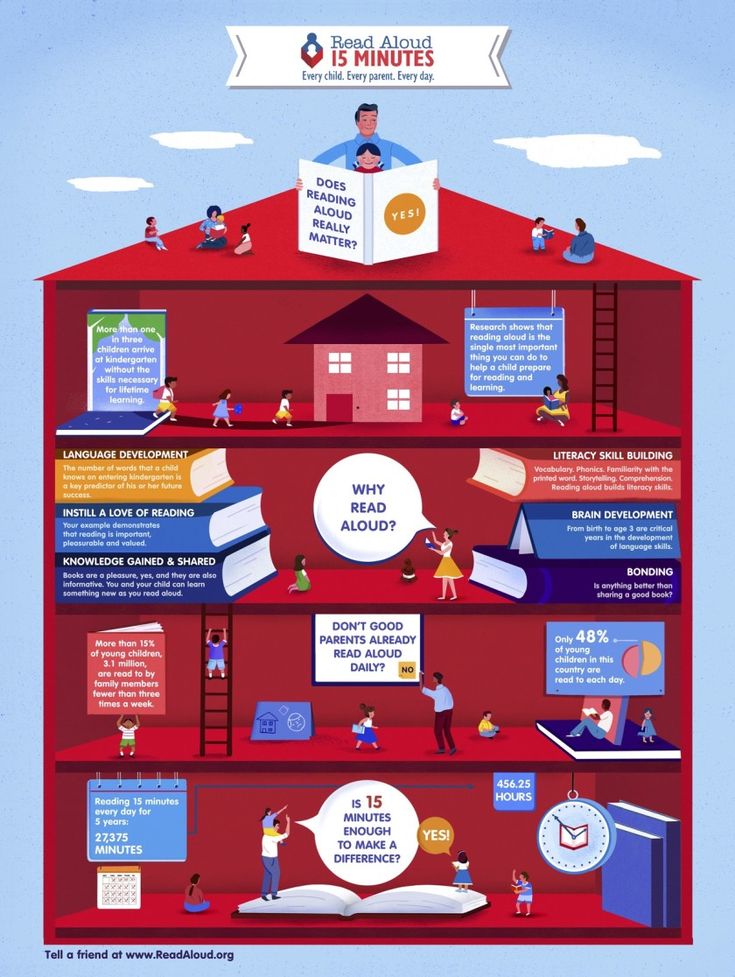

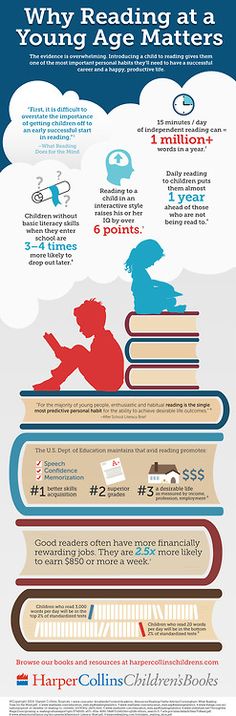

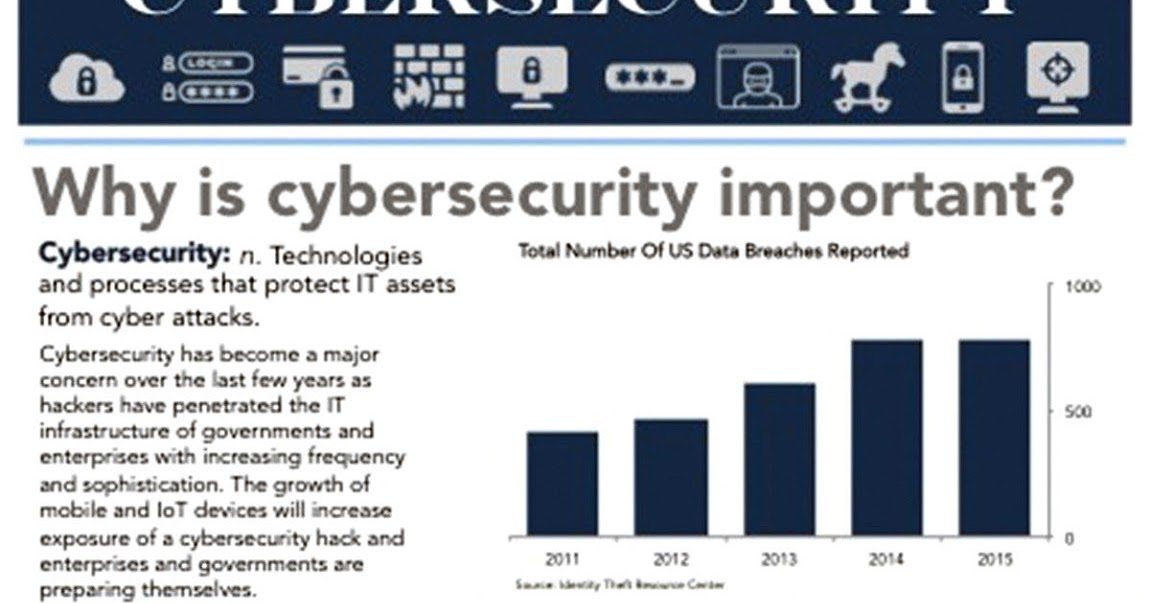

There are many activities parents and child care providers can do to support children's emergent literacy skills. Photo credit: Pixabay.Did you know that preschoolers whose parents read to them, tell them stories and sing songs with them tend to develop larger vocabularies, become better readers and preform better in school? Did you know that reading proficiently by the end of the third grade is considered a “make it or break it” benchmark? Or that 83 percent of children who are not reading on grade level by the beginning of fourth grade are at risk of failing to graduate from high school on time? In order to be sure that your child is reading on grade level, it’s important to support their emergent literacy development.

Emergent literacy skills are critical “getting ready to read” skills that children need to develop before the can learn to read.

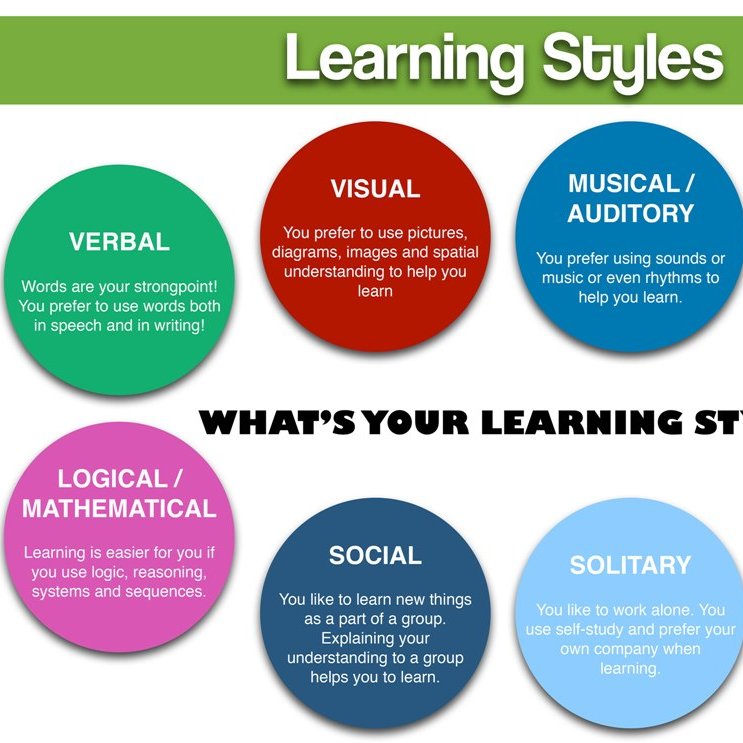

These early literacy skills begin early on as young children learn to use verbal and nonverbal communication patterns, including speech and sign language, to express themselves. Parents and other primary caregivers often understand these early attempts at communication best. Along with language development, children are building their vocabulary. They learn new vocabulary in many ways, including through reading books and talking with adults in their environment. Studies have shown that the larger a child’s vocabulary, the quicker they will learn to read, as they are familiar with more of the words they will encounter.

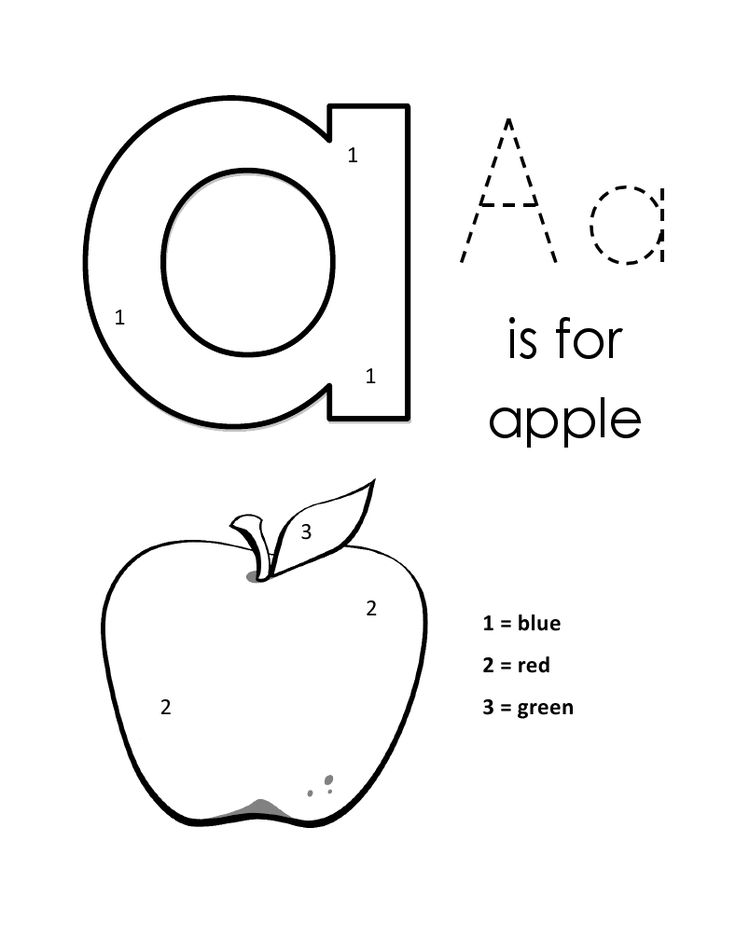

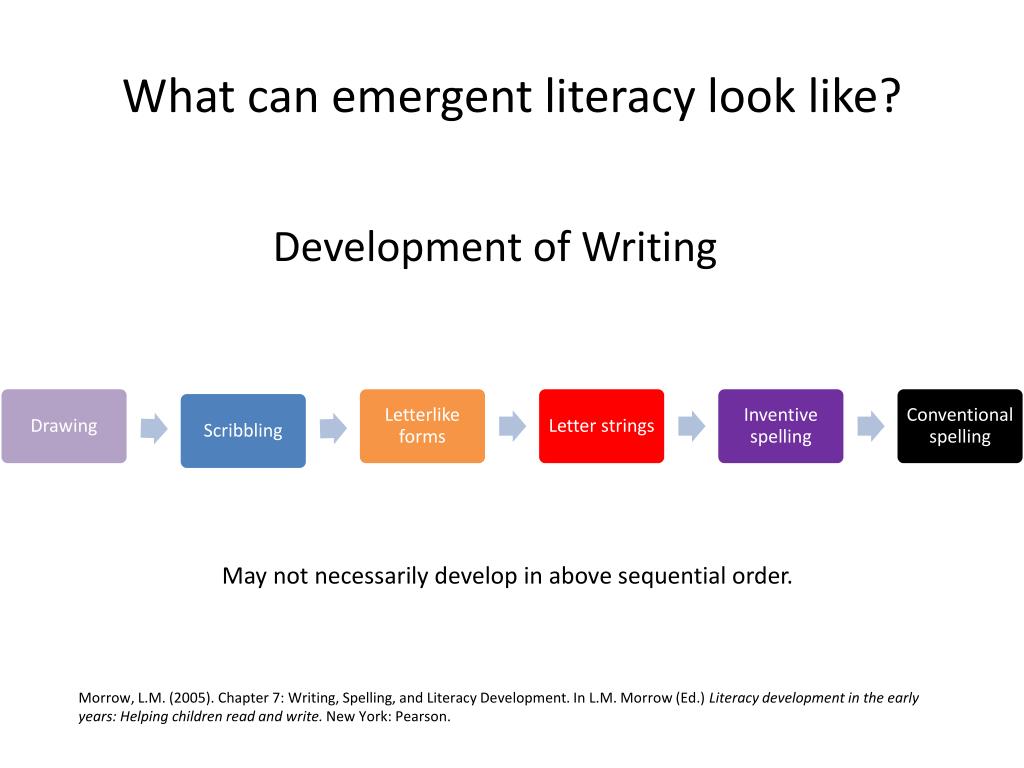

Experimental writing is another critical early literacy skill. Children’s first efforts at writing typically resemble scribbling, but children usually know what they have “written” if you ask them! Often, the first legible marks are letters in the child’s name. When children do not have access to writing materials, they may enter Kindergarten not even knowing how to hold pencils or crayons!

When children do not have access to writing materials, they may enter Kindergarten not even knowing how to hold pencils or crayons!

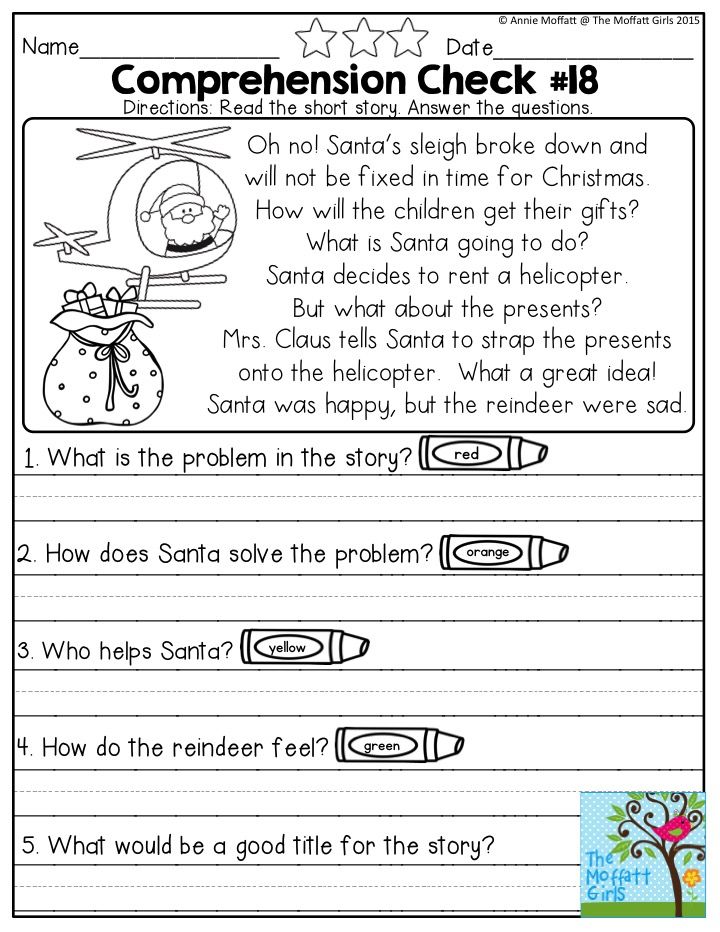

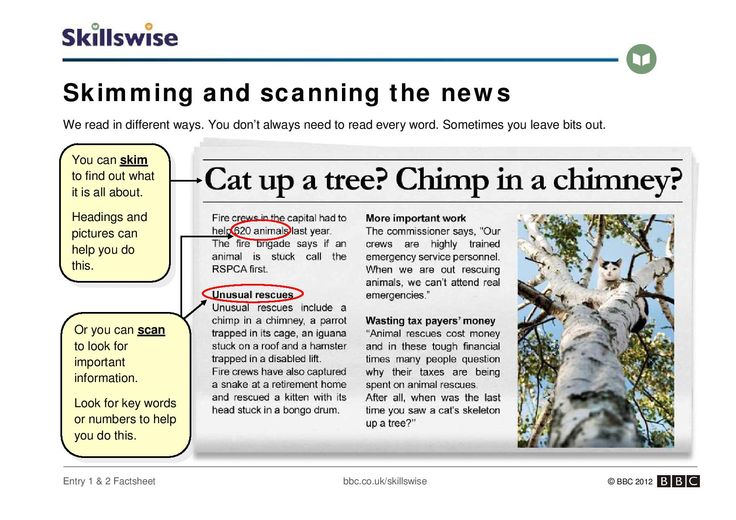

As children begin to understand that print on the page stands for something, they are developing what is known as print awareness. When children begin to develop this skill, they may hold a book correctly, even though it is upside down and backwards, for instance. As these skills progress, they will know where a story begins and ends, and learn that text is read from left to right.

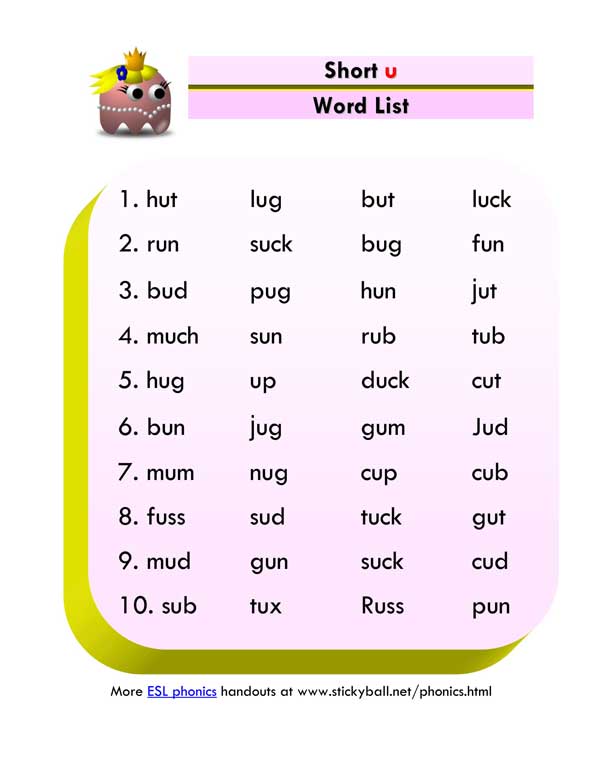

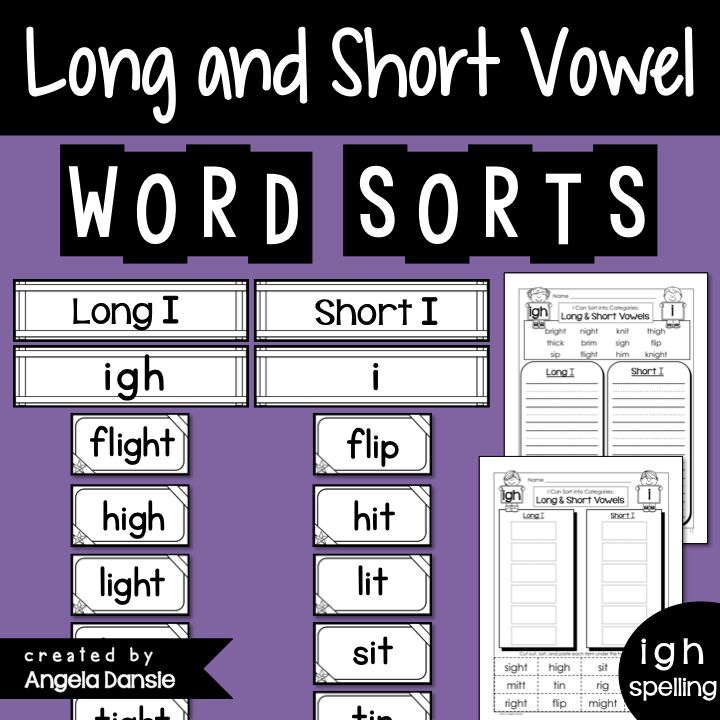

Two additional emergent literacy skills that are important for children to learn to read are the concepts of letter knowledge and alphabetical principle. Letter knowledge is knowing the letters of the alphabet and recognizing them in print. Alphabetical principle is the concept of associating letters with sounds and sounds with words, knowing for instance that “B” makes the “buh" sound. These skills are critical for children to be able to learn to decipher the text on the page. Children will often begin to notice letters that are familiar to them first, such as the letters in their name, or other letters they frequently see around them such as the S on stop signs.

Children will often begin to notice letters that are familiar to them first, such as the letters in their name, or other letters they frequently see around them such as the S on stop signs.

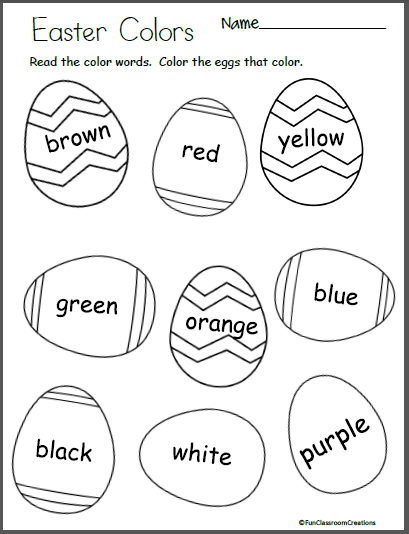

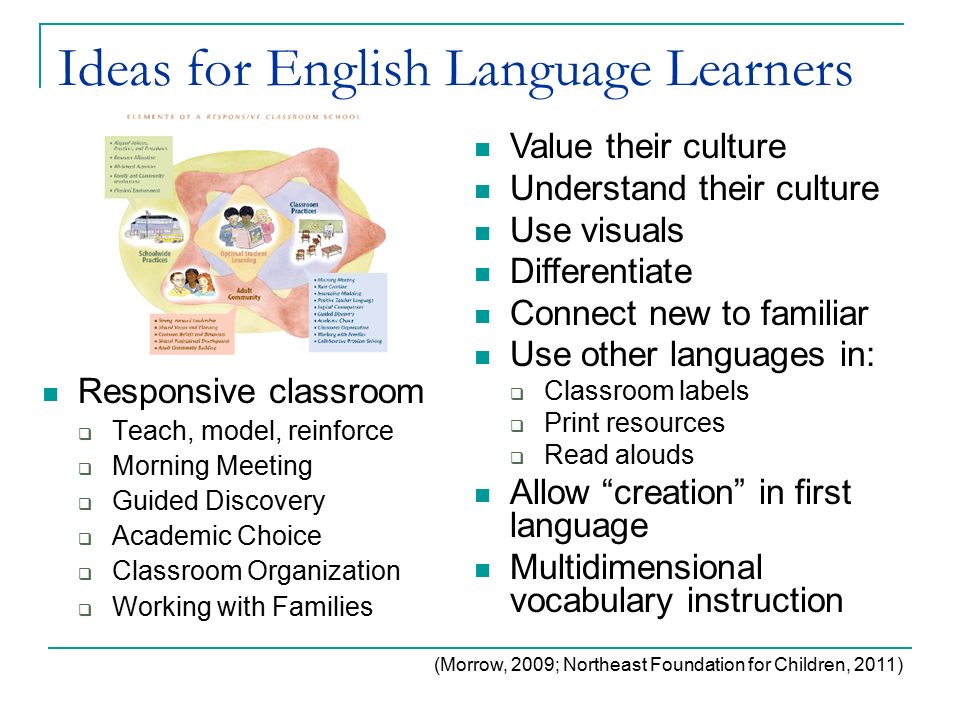

There are many activities parents and child care providers can do to support children’s emergent literacy skills. Talking with children, reading to them, signing, playing games, saying nursery rhymes, playing word games, having access to writing materials and books, and taking them to the library will support their literacy. Michigan State University Extension recommends engaging in 30 minutes a day of literacy activities with your child.

Learn more about how you can support your children’s continued academic success, find articles on a wide variety of topics and learn about informational programs offered both online and in a community near you at MSU Extension.

This article was published by Michigan State University Extension. For more information, visit https://extension.msu.edu. To have a digest of information delivered straight to your email inbox, visit https://extension.msu.edu/newsletters. To contact an expert in your area, visit https://extension.msu.edu/experts, or call 888-MSUE4MI (888-678-3464).

For more information, visit https://extension.msu.edu. To have a digest of information delivered straight to your email inbox, visit https://extension.msu.edu/newsletters. To contact an expert in your area, visit https://extension.msu.edu/experts, or call 888-MSUE4MI (888-678-3464).

Did you find this article useful?

You Might Also Be Interested In

What It Is And Why It’s Important

What Is Emergent Literacy?

Emergent literacy is the stage during which children learn the crucial skills that lead to writing and reading.

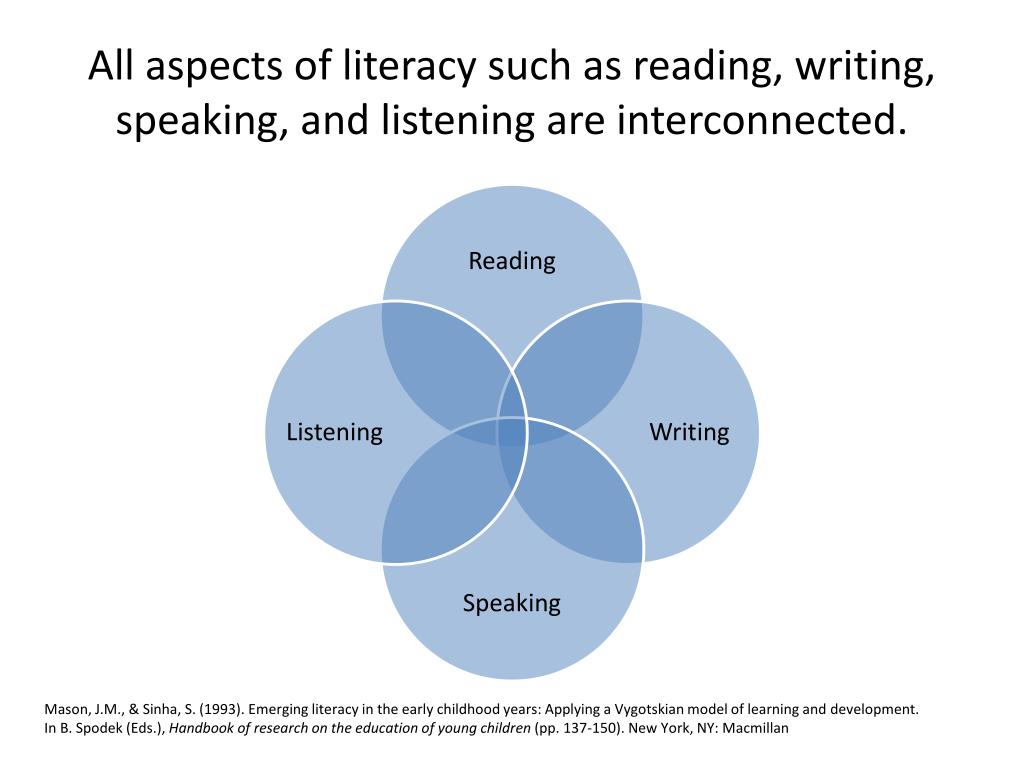

Literacy builds on the foundations of language to include the advanced ways in which we use language to communicate — primarily through reading, writing, listening, watching, and speaking with one another.

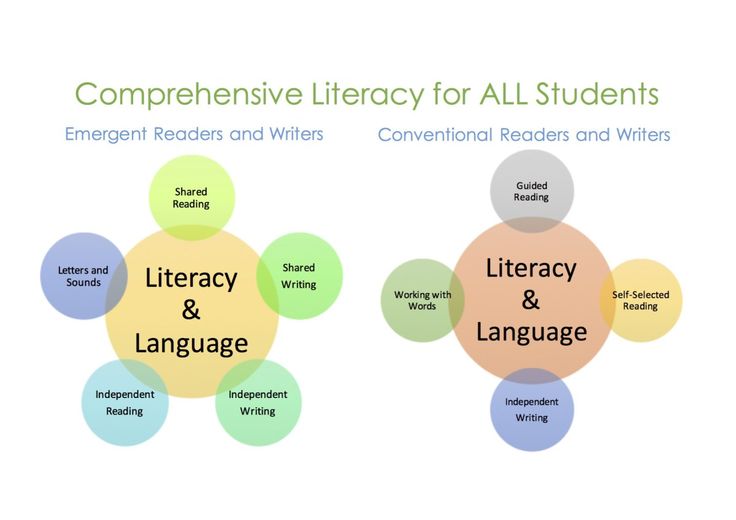

Components Of Emergent Literacy

Emergent literacy is made up of several different parts. Your child will encounter these essential components as they begin to explore reading. They include:

- An interest and enjoyment in print — handling books and relating them to their stories or information.

- Print awareness: how to handle a book, reading from left to right. Your child recognizes pictures and some symbols, signs, or words.

- An interest in telling and listening to stories. They attend to, repeat, and use some rhymes, phrases, or refrains from stories or songs.

- They make marks and use them to represent objects or actions. An understanding that words are made up of letters, recognizing letters when they see them.

- Your child comprehends meaning from pictures and stories.

And the list goes on! Really, emergent literacy components help your child understand the basic tools they’ll need to read all sorts of books and other materials in the future.

Why Is Emergent Literacy Important?

Almost every skill we learn in life requires some preliminary learning in order to finally achieve mastery. For example, you probably didn’t wake up one day knowing how to make pancakes (although if you did, we would love to learn your secrets!).

Instead, you first had to learn what ingredients you needed, how much to measure each item, how long to cook the batter, and so on.

Reading and writing require these same preparatory steps, also known as emergent literacy.

Emergent literacy preps your child’s brain with the skills they’ll need to learn how to read. And while this may sound complex, many emergent literacy skills develop naturally!

When your child points at something and you follow their direction or when you call their attention to noises, objects, or people in their surroundings by speaking to them, you’re helping your child develop emergent literacy skills.

You’re helping them acquire the same tools they’ll incorporate into their future learning, from reading their very first storybook to writing a master’s thesis.

Supporting Your Child’s Emergent Literacy Skills

Here are some fun and easy ways you can stimulate your child’s emergent literacy skills at home.

Read Aloud

Reading aloud is the most effective way for a child to learn to love books and the power of stories. Loving to read begins with loving to listen to stories!

Our team at HOMER believes that investing in read-aloud sessions with your child substantially improves many of the skills they need on their lifelong reading journey.

For emergent readers, there are few things more wonderful (or effective) than sitting down with mom or dad and uncovering the worlds that live between the covers of a book.

With you as their guide, your child will grow more confident and reassured as they gradually learn about the things they love (like how many different types of dogs exist or how the sky makes rainbows).

Reading aloud to your child also helps strengthen their imagination and build their curiosity. While listening to you recount the wonderful world inside of a story, your child’s mind will be actively running through images, scenarios, and all the colorful possibilities that lie beyond the page.

Reading aloud is one of the easiest, most rewarding ways for you to bond with your child while helping them learn. Consider that by reading aloud to them and encouraging their participation, you are empowering them as learners.

Additionally, you will reap the benefits of understanding their interests more deeply, engaging with their budding imagination, and instilling confidence in their learning process.

Let Your Child Take Charge

As your child grows, their sense of independence and autonomy continues to develop. While we know these early years are precious, we also know you’re hopeful your child will grow into a strong, independent learner who reads well and frequently.

Allowing your child to assert their unique personality and independence every now and then can be beneficial in engaging their emergent literacy skills.

These moments may seem small at first, but even the simplest freedoms in your child’s routine can have huge impacts on their individualism! It’s all about allowing your child to exert a certain amount of control over their reading time.

For example, instead of you turning the pages during your reading time together, allow your child to dictate when the pages should be turned. This may take some getting used to for them as they learn the pace of reading aloud in conjunction with the words they see printed.

You can also let them experiment with narrating! Even if your child cannot read yet (we know they’re called emergent readers for a reason!), allowing them to use their toddler-talk through the story shows them that they will read one day not far away.

Finally, letting your child pick out the book you’ll read together is a great way to engage their sense of independence. It gives them something to look forward to while reading with you and also gives you insight into their interests.

It gives them something to look forward to while reading with you and also gives you insight into their interests.

If you find your child keeps reaching for the same book multiple times, don’t worry — rereading is highly beneficial, too!

Take Your Time

Don’t be afraid to slow it down for your child while you’re reading together, or even just in your daily speech.

We know we’re all guilty of it. For so long, our babies aren’t sure how to “properly” talk back yet, so there may be the occasional time when we find ourselves mumbling to our baby without really engaging them, or simply saying nothing at all!

Taking time to be more conscientious of the ways in which you talk to your child, especially in their very young years, can help them gain the skills they’ll need to read, speak, and write.

Especially when reading together, there’s no need to rush! We recommend taking your sweet time. Even if it’s just with one page of a book at a time, slow down and ensure your child is engaged.

Consider these questions:

- Does your child recognize every animal on a page?

- Do they know what color this character’s hair is or whose hair it resembles in your family?

- Do they know what sound a truck makes?

- When you say the word “surprise,” does your child react in a way that conveys understanding (throwing their hands up in exclamation or even clapping)?

Addressing these questions can help you and your child slow down and take in all the details that are in a story.

Keep The Conversation Going

If you like the idea of our last emergent literacy strategy, this one pairs perfectly with it!

We know half of the adventure in helping your child learn to read is figuring out what gaps in their understanding still need to be filled. The other part of the journey is keeping them engaged and interested and seeing how far your conversations with one another can go!

As your child expands their vocabulary and begins utilizing it, we encourage you to elaborate on the things they may point out to you. For example, if you’re walking together and they see a dog, they may point at it and say, “puppy!”

For example, if you’re walking together and they see a dog, they may point at it and say, “puppy!”

In any scenario like this, following up their observation with a cheer is great. Following up with more questions is even better! After affirming they saw the right thing (or correcting them if they mistakenly called it a kitty, for example), ask them about details and descriptions.

You could say, “Does this puppy have long ears? Yes, he does! Feel how soft his ears are. Isn’t his fur shiny, brown, and so soft? What a cute puppy.”

Injecting these details and descriptions into your conversations might feel silly, but it helps your child immensely!

By expanding on the image they identified, you’re directly contributing to their understanding of the scene in front of them. The next time they see a puppy in a park, they may take your lead and say, “Look! A big puppy!”

This progress shows that your child’s emergent literacy is growing!

Let Your Child “Write”

Emergent literacy incorporates writing as well as reading. This may sound a little crazy — how can your child write if they don’t know how to read yet?

This may sound a little crazy — how can your child write if they don’t know how to read yet?

While your child may not be able to correctly write out words, we certainly encourage you to let them try! Even if it’s just scribbling, allowing your child to practice “writing” gets their brain going in the right direction.

It also prepares them for what writing is really like and shows them that they have the power to put words on paper. There are stages of learning how to write, and scribbling is the first step!

Asking for your child’s help with writing out short tasks can boost their confidence and their excitement about learning to write. Good options include grocery lists, birthday cards, get-well-soon cards, thank you notes, or notes for their siblings and family.

Whatever keeps them excited and engaged is a great vehicle for motivating their writing skills!

Emergent Literacy Is Just The Beginning!

We know that emergent literacy is only the start of your child’s reading and writing journey.

While you and your child are probably thrilled at the idea of their eventual independence and confidence when it comes to handling books, it’s going to take some time. And that’s perfectly OK!

Every child is different and will learn how to read and write in their own time. The important part is enjoying the adventures you have together on the way there!

We hope our emergent literacy tips were helpful! If you ever want to change up your routine and explore new ways to touch on these skills, our Learn & Grow app is a great place to start! The personalized practices will give your child the tools they need for their learning journey.

Author

Early childhood literacy

Preschoolers learn a lot about written language long before they learn to read and write in traditional ways. And this is quite natural: children live in a world full of written symbols. Every day they observe and themselves take part in various activities related to books, calendars, lists and inscriptions. Gradually, they learn to understand how written symbols convey meaning. Children's active efforts to develop literacy skills through informal experiences are called emergent literacy.

Gradually, they learn to understand how written symbols convey meaning. Children's active efforts to develop literacy skills through informal experiences are called emergent literacy.

Younger preschoolers look for familiar elements of written speech when they “read” fairy tales that they remember and recognize familiar inscriptions. However, they do not yet understand the symbolic function of the printed word. Many preschool children believe that one letter stands for a whole word. At first, they do not even distinguish between drawing and writing. Around the age of four, some of the distinctive features of block text appear in their writing, such as the alignment of figures. However, at the same time, children often use drawing elements - for example, write the word "sun" with a yellow felt-tip pen or draw it in the form of a circle. They express their understanding of the symbolic function of drawings in the “drawing” of letters.

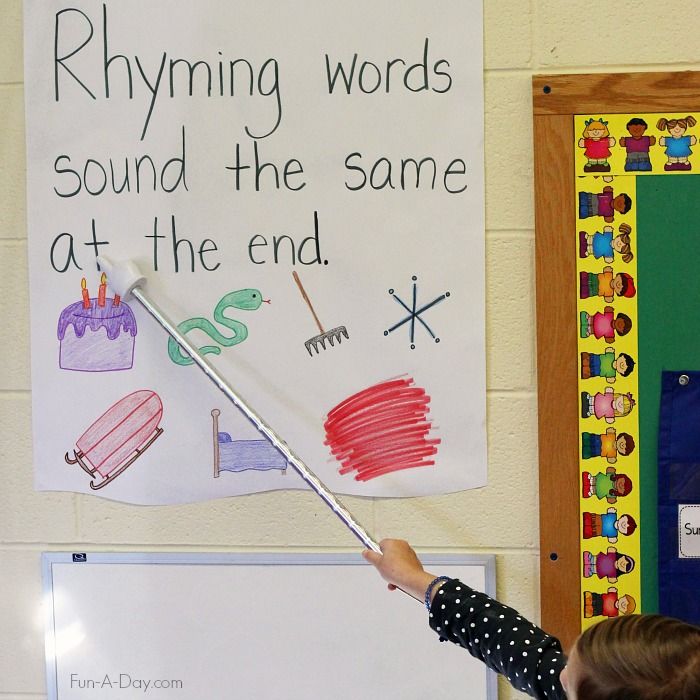

The development of literacy skills is based on speaking and knowledge of the world around. Over time, children's progress in language acquisition and literacy skills begin to support each other. Phonological awareness, that is, the ability to analyze and use the sound structure of colloquial speech, which is evidenced by sensitivity to changes in the sounds that make up words, as well as to rhyme and mispronunciation, is considered an indicator of advanced emergent literacy. Combined with an understanding of the correspondences between sounds and letters, this ability allows children to isolate fragments of speech and associate them with the corresponding written characters. Vocabulary and grammatical knowledge also play an important role in this process. In the course of story conversations between an adult and a child, various speech skills are improved, which are of great importance for the development of literacy.

Over time, children's progress in language acquisition and literacy skills begin to support each other. Phonological awareness, that is, the ability to analyze and use the sound structure of colloquial speech, which is evidenced by sensitivity to changes in the sounds that make up words, as well as to rhyme and mispronunciation, is considered an indicator of advanced emergent literacy. Combined with an understanding of the correspondences between sounds and letters, this ability allows children to isolate fragments of speech and associate them with the corresponding written characters. Vocabulary and grammatical knowledge also play an important role in this process. In the course of story conversations between an adult and a child, various speech skills are improved, which are of great importance for the development of literacy.

The more informal opportunities for learning literacy skills that preschool children have, the better their speech and emergent literacy, and subsequently their reading skills, are developed. By drawing children's attention to the fact that letters stand for sounds, by playing games with speech and sounds, adults increase children's awareness of the sound structure of speech and how it is displayed in written text. Interactive reading and discussion of the content of the book with preschoolers stimulates different aspects of the development of speech and literacy skills. Children benefit greatly from adult help with writing assignments in the form of a composition, such as writing a letter or a story.

By drawing children's attention to the fact that letters stand for sounds, by playing games with speech and sounds, adults increase children's awareness of the sound structure of speech and how it is displayed in written text. Interactive reading and discussion of the content of the book with preschoolers stimulates different aspects of the development of speech and literacy skills. Children benefit greatly from adult help with writing assignments in the form of a composition, such as writing a letter or a story.

Read about how to support self-learning in early childhood literacy in the Idea Fair section.

Based on materials from the book "Child Development" by Laura Burke.

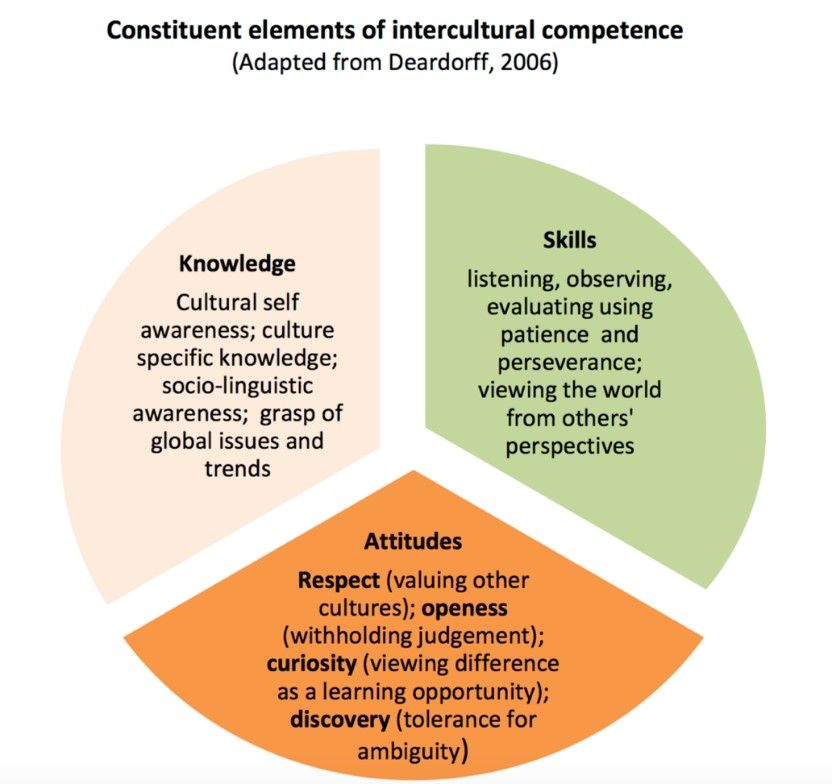

Competency-Based Approach and Cultural Literacy: On the Sources of Formation of New Requirements in the Educational Systems of English-speaking Countries / I. K. Petrova. - Text: direct // Education and upbringing. - 2018. - No. 3 (18). — S. 2-5. — URL: https://moluch.ru/th/4/archive/94/3399/ (date of access: 26.

10.2022).

10.2022).

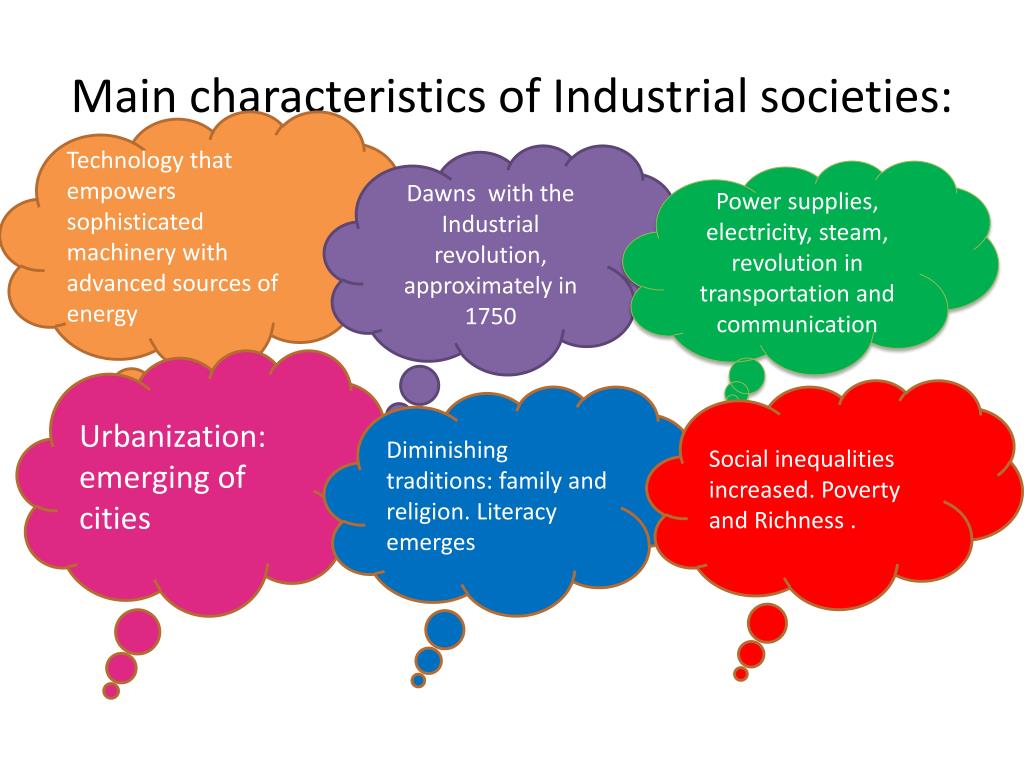

A competency-based approach to assessing the effectiveness of the education received by a graduate developed in the United States in the 1970s. This was favored by the then socio-economic situation: with the growth of high-tech industries and the withdrawal of some traditional industries to the countries of the "third world", the flow of personnel into the service sector and the growth in the number of small businesses required a more flexible system of training and retraining of workers and a greater variety of specializations.

Formally, the term "competence" to express the potential realizable ability of an individual to a certain type of activity was proposed by the American linguist and philosopher N. Chomsky, in the context of linguistic problems. As the Russian authors K. E. Stein and D. I. Petrenko point out, in his works N. Khomsky contrasts the ability (“competence” - competence) of the individual to create and perceive speech messages - the realization of this ability (“performance”, performance), which is reminiscent of the opposition of "language" and "word" in the constructions of F. de Saussure [1].

de Saussure [1].

It should be noted that the competency-based approach was essentially not alien to the domestic education system, which was initially focused on training personnel for the national economy, and which had a practical orientation at its highest levels. However, the general cultural component of Soviet educational programs usually suffered, on the one hand, from excessive ideologization and, on the other hand, from underestimation of a number of trends that developed in the culture of Western countries in the 2nd half of the 20th century.

As O. N. Yarygin notes in his review of various interpretations of the term [2], “in psychology and the field of human resource development, it is customary to trace the history of the term “competence” from the article by D. McClelland “Testing competence, not intelligence” , in which it was shown that intelligence tests are not enough for the correct selection of personnel, since high intellectual indicators do not provide high performance in practical activities.

D. McClelland himself illustrates his idea with the following example: if an inhabitant of the Boston ghetto wants to become a policeman, his intellectual abilities will be tested through a three-hour test, which requires knowledge of such words as “pyroman” and “lexicon”, borrowed into English from ancient Greek. “If,” he says, “you don’t know enough of those words… you don’t qualify and must be satisfied with a job for which the Massachusetts Civil Services Commission doesn’t yet require an intelligence test—for example, a janitor.” ].

One of the modern followers of D. McClelland, the Dutch researcher M. Mulder, defines competence as follows:

“A professional is competent when he acts according to set standards of performance, responsibly and efficiently. You can also say that this professional

has sufficient competence. Professional competence is seen as a universal, integrated and internalized ability to provide sustainable, effective (decent) work (including problem solving, innovation and change) in a specific professional area, position, role, organizational context and work situation.

Competence consists of various competencies. Competence is part of general competence, it is a set of interrelated knowledge, skills and attitudes that can be used in the context of real work” [4].

M. Mulder notes that secondary and higher education was commercialized in the course of its distribution, and obtaining a diploma at some point turned into an end in itself for many. In this situation, not every educational institution was able to take into account the needs of society as a whole, in particular the needs of the labor market. This problem was called the ‘diploma disease’, since the presence of a diploma did not provide reliable guarantees for the professional suitability of young specialists.

Thus, a whole “competence movement” arose. Various trade unions and organizations, as well as employers, began to put forward their requirements for job seekers. Educational institutions, in turn, began to adjust curricula in such a way as to meet the practical requirements of enterprises and trade unions.

“However,” writes M. Maulder, “since the concept of “professional competence” is multidimensional, like the concept of “intellectuality,” different concepts of competence have arisen. Sometimes they were praised, sometimes they were scolded, due to inconsistency with the intended content and disappointing practical results that did not provide the promised quality” [4].

New ideas have gained popularity among businessmen and those involved in the training and selection of personnel for new industries and new types of commercial activities. Quite quickly, the competency-based approach began to prevail in the US education system, aimed at developing professional skills and personal qualities that were most in demand by employers and promised a quick and full return on investment. These important shifts hardly affected the economic and educational space of the USSR, separated by the Iron Curtain. The names of Chomsky and McClelland began to advance in our country much later, during the period of Perestroika and entry into the world market, which launched similar socio-economic processes in the post-Soviet space.

In 1989–1996 Based on the competence-based approach, the Council of Europe has developed the Common European Framework of Reference: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. This document, developed as part of the Language Learning for European Citizenship project and containing common methods for assessing the level of foreign language proficiency, was approved in 2001 and recommended for use in all EU countries.

The pragmatism of the competency-based approach led to its widespread use outside the United States, however, this was followed by criticism. In Europe, Chomsky, McLelland and their followers are criticized for vagueness of wording, fragility of criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of the educational process and terminological confusion, exacerbated by the need for translation into other languages (which often contain words derived from the same Latin roots, but differing in meaning) [ 5]. In Russia, the dispute between linguists about the legitimacy of the use of certain Chomsky terms has also not yet been exhausted [6], [7].

Over time, practice has shown that it is short-sighted to neglect the cultural outlook and the general development of the intellect for the sake of a speedy return on investment. Obviously, the globalization of the economy, coupled with the mobility of the workforce and the rapid development of new means of communication - mobile communications and the Internet - place increased demands on the general cultural competencies of managers and staff of companies involved in international supply chains, as well as on employees of the media, advertising, recruiting and tourism. agencies, etc.

The need to develop a general outlook for future specialists was very convincingly substantiated by the American culturologist and educator E. D. Hirsch, the author of the concept of “cultural literacy” (cultural literacy) and several books on this topic, which quickly became bestsellers [8].

As O. A. Ansimova writes, his concept “… has been relevant for American linguists, culturologists, teachers and other specialists in the field of humanitarian knowledge for several decades… In Russia, it is still little known and has practically no history of study. This is probably due to the fact that, until recently, the problem of overcoming the low level of literacy or the lack of national identity in Russia was not so acute. In other words, the researchers ignored "cultural literacy", since it was taken for granted, immanently inherent in "the most reading nation" [9].

This is probably due to the fact that, until recently, the problem of overcoming the low level of literacy or the lack of national identity in Russia was not so acute. In other words, the researchers ignored "cultural literacy", since it was taken for granted, immanently inherent in "the most reading nation" [9].

Unlike the USSR, with its unified educational space, standardized programs and textbooks, primary and secondary education in the United States was almost completely dependent on local authorities. And if the children of the American “middle class” traditionally got acquainted with classical English literature, then this cultural background was absent among the inhabitants of the ghetto and in emigrant families. Meanwhile, according to Hirsch’s calculations, 80% of “cultural literacy” has been in use for more than a hundred years” (“80% percent of literate culture has been in use for more than a hundred years”) [10]. Thus, a significant part of the common cultural heritage of English-speaking countries (and even Europe as a whole) is inaccessible to some social strata in the United States. This complicates social dialogue, hinders the development of an adequate civic position and career growth for people from poor families.

This complicates social dialogue, hinders the development of an adequate civic position and career growth for people from poor families.

Developed by E. D. Hirsch et al., a list of terms, names, quotations, and cultural borrowings that have entered the English language has been published under the title Cultural Literacy: What Every American Should Know? (“Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know”) and caused heated discussion [10]. For example, R. I. Vorontsov notes that some terms and concepts from the Hirsch list, including those related to Russia, are extremely simplified and “reflect the stereotypes of mass consciousness” [11] .

To promote his ideas and attract a wide range of educators, culturologists and literary scholars to cooperate, E. D. Hirsch founded the Core Knowledge Foundation, which is engaged in the development of teaching aids, programs and other materials for schools that have expressed a desire to increase the information content of the educational course [12].

With brief explanations, Hirsch's list has been reprinted several times and eventually used in the current reform of the US education system to develop recommendations for the creation of programs that include "basic knowledge" (Common Core curriculum). Similar lists were compiled in Europe for German, Dutch, Swedish, and some other languages (see, for example, [13]).

In the 2000s, this work became for the English-speaking countries a kind of program for the development of general cultural competencies, temporarily pushed into the background in the 70s and 80s. At the same time, in Russia, the works of Hirsch and his colleagues are mainly used by English teachers to develop students' linguistic and cultural competence, although the original meaning of this project is much broader.

It is noteworthy that supporters of increasing the requirements for the informative richness of education note that mastering "cultural literacy" does not interfere with the development of students' individuality and creative abilities [14].

Hirsch's ideas gained him many admirers in other English-speaking countries as well, primarily in Great Britain, where they were highly appreciated by the Ministry of Education. The Hirsch list was used there, as in the United States, as one of the important reference points in the development of updated requirements for curricula and graduates. A number of British schools, which have the status of "academies", have received a recommendation to pay more attention to classical literature and the basic concepts of modern culture. In his review of the National Curriculum, Education Minister Michael Gove said that schools should focus on learning key facts, equipping children with the necessary knowledge to help them learn at a higher level [15]. According to P. Bennett, interest in Hirsch's ideas is now flaring up with renewed vigor in Canada, as opposed to the "lite" (curriculum-lite) programs of the previous period [16].

In Russia, several attempts have also been made to compile a "dictionary of cultural literacy" based on the Russian language and literature [17], [18], [19]. Comparing them with each other, N. A. Sudakova proposed her own concept of a linguocultural dictionary for schoolchildren [20]. Tellingly, Russian authors generally do not oppose competencies and skills to intelligence and knowledge as mutually exclusive educational goals. In particular, the concept of “general cultural competence” (as opposed to professional competence), reflected in the Federal State Educational Standard, has entered and consolidated in Russian pedagogical literature. This concept partially covers those skills and knowledge, for the sake of which, in fact, the Core Knowledge project was started.

Comparing them with each other, N. A. Sudakova proposed her own concept of a linguocultural dictionary for schoolchildren [20]. Tellingly, Russian authors generally do not oppose competencies and skills to intelligence and knowledge as mutually exclusive educational goals. In particular, the concept of “general cultural competence” (as opposed to professional competence), reflected in the Federal State Educational Standard, has entered and consolidated in Russian pedagogical literature. This concept partially covers those skills and knowledge, for the sake of which, in fact, the Core Knowledge project was started.

Perhaps such a combination of a competency-based approach with information-rich educational materials is the best way to develop an educational system that can absorb the best achievements of world pedagogical thought.

At the same time, it seems that the Russian version of the "dictionary of cultural literacy" would be very useful - at least as a cultural reference. This is clearly required both by the rapid development of the media and by the ongoing migration flow in the post-Soviet space.

This is clearly required both by the rapid development of the media and by the ongoing migration flow in the post-Soviet space.

Literature:

- Stein K. E., Petrenko D. I. Language competence: from A. A. Potebnya to N. Chomsky // Rhema. Rema. - 2015. - No. 4. - S. 105–120.

- Yarygin Oleg Nikolaevich "Competence" and "Competence" as emergent properties of human activity // Vector of Science TSU. - 2011. - P.345–348

- McClelland, D. C. Testing for Competence Rather Than for " Intelligence " / D. McClelland. // American Psychologist, - 1973.-Vol. 28.-No. 1 - P.1-14

- Mulder, M. - Conceptions of Professional Competence. // International Handbook of Research in Professional and Practice-based Learning. - 2014. - P.107-137.

- Hébrard, Pierre. Ambiguities and paradoxes in a competence-based approach to vocational education and training in France// European journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults.

- 2013. - 4/2. - S. 111–127

- 2013. - 4/2. - S. 111–127 - Misheneva Yu. I. Competence approach in teaching foreign languages // Concept. - 2014. - Special issue No. 08. - P. 31–35

- Medintseva I. P. Competence-based approach in education // Pedagogical excellence: materials of the II Intern. scientific conf. (Moscow, December 2012). - M.: Buki-Vedi, 2012. - URL https://moluch.ru/conf/ped/archive/65/3148/ (date of access: 05/18/2018).

- E. D. Hirsch, Jr. // Encyclopaedia Britannica.—URL: https://www.britannica.com/biography/E-D-Hirsch-Jr

- Ansimova O. K. The concept of linguistic and cultural literacy: relevance and prospects // Philology and literary criticism. - 2014. - No. 7 - URL: http://philology.snauka.ru/2014/07/844

- Hirsch E. D., Jr., Kett J. F., Trefil J. The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy. - ISBN 0-618-22647-8 - Boston; N.-Y.: Houghton Mifflin Company. - 2002. - 647 p.

- Vorontsov R. I. Cultural literacy: the American version // Universum: Bulletin of Herzen University.

- 2009. - No. 3. - P.51–57.

- 2009. - No. 3. - P.51–57. - Kohn Alfie. What Does It Mean to Be Well Educated? - ISBN: 978-0807032671 - Penguin Random House - 2014. - 90 p.

- Izotov AI American culture in the mirror of the national corpus of the Czech language: Literature, mythology, folklore. — ISBN 978-5-91172-028-5. — M.: Azbukovnik, 2010. — 200 p.

- Baer J. The Impact of the Core Knowledge Curriculum on Creativity // Creativity Research Journal. - 2003. - No. 15.2/3. — S. 297–300.

- Abrams F. Cultural literacy: Michael Gove's school of hard facts // BBC Radio 4's Analysis. URL: http://www.bbc.com/news/education-20041597 (accessed 05/18/2018).

16. Bennett P. W. Knowledge Matters: Why is the Core Knowledge Curriculum Experiencing a Revival? // Educhatter. Lively Commentary on Canadian Education. URL: https://educhatter.wordpress.com/2015/09/21/knowledge-matters-why-is-the-content-lite-curriculum-in-retreat/ (accessed 05/18/2018).

17. Stepanov Yu. S. Constants. Dictionary of Russian culture. - M .: School Languages of Russian Culture, 1997. - 824 p.

Stepanov Yu. S. Constants. Dictionary of Russian culture. - M .: School Languages of Russian Culture, 1997. - 824 p.

- Pushnykh V.A., Shevchenko N.N. Are you literate, or 5000 words that will help you check it. - Tomsk: Tomsk University Press. - 1994. - 86 p.

- Kozyrev V. A., Pentina A. Yu., Chernyak V. D. — How to check cultural literacy: vocabulary and test tasks: educational and methodological material for students in the areas of pedagogical education. - St. Petersburg: Publishing House of the Russian State Pedagogical University im. A. I. Herzen, 2008.

- Sudakova N.A. About the concept of the school cultural dictionary // Bulletin of the TSPU. - 2013. - No. 3 (131). — S. 196–201.

Basic terms (automatically generated) : Russia, USA, Europe, knowledge, cultural literacy, English, competence, performance evaluation, approach, post-Soviet space.

Cultural diplomacy in the system of international relations on.

..

.. The authorities of countries in the post-Soviet space work in a free market society

7. Gurbangeldiyev J. Cultural diplomacy - language interethnic dialogue.

[2] Other examples: small grants of embassies USA , Japan for countries where cultural artifacts ...

Linguistic and regional studies in teaching foreign languages

Therefore, for the entry of Russia in European Educational space It is important not only the study of of the country, but also its

Formation of linguistic and studies senior ... Language , Knowledge , English Language , foreign language , foreign language. ..

..

Features

assessment knowledge foreign language ...Evaluation of results in points. TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) is a comprehensive test developed in USA for those who want to get an education or work in English language . When evaluation of oral speech is assessed

Relevance

knowledge foreign language in the modern worldKnowledge of English language is one of the conditions for employment in companies operating in foreign markets or having foreign partners (and there are more and more of them in Russia ).

About efficiency early learning English language .

Ways to successful intercultural communication | Journal article...

As you know, the ISS is a joint project Russia , USA , European

Knowledge English language for Russian cosmonauts is required at a fairly high level.

- to form a foreign cultural identity, which implies knowledge of language ...

Development of socio-cultural competence

students in the classroom...as performance indicator activities. In accordance with this, competence is a dynamic combination of knowledge , skills and

Sociocultural Competence , competence , training , foreign communicative competence .

Teaching foreign languages

in modern Russia ...English language , intercultural communication, American culture , language , type of communication, USA , special role, world communication, intercultural communication, company.

Professional

English Language Russian System...Key words: English language , level, students, knowledge , specialists.

Basic terms (automatically generated): English language , Russia , foreign language , level proficiency , modern

Common European competencies foreign language proficiency .