Why is fluency important to reading

What Is Fluency? Why Is Fluency Important? :: Read Naturally, Inc.

What Is Fluency?

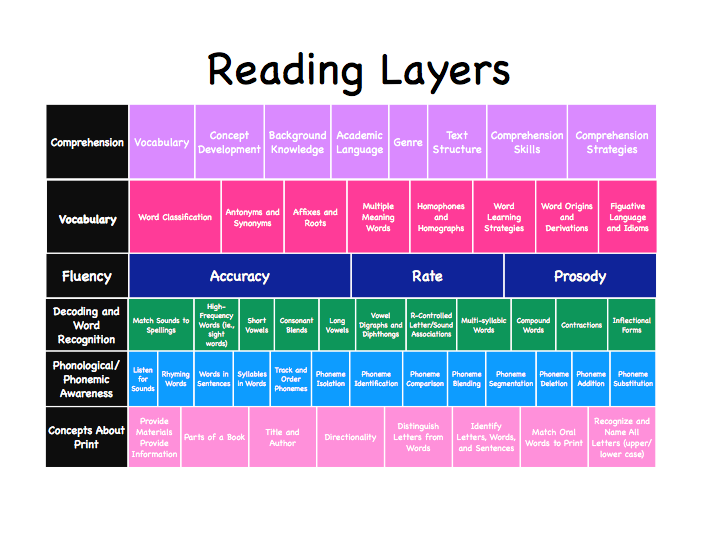

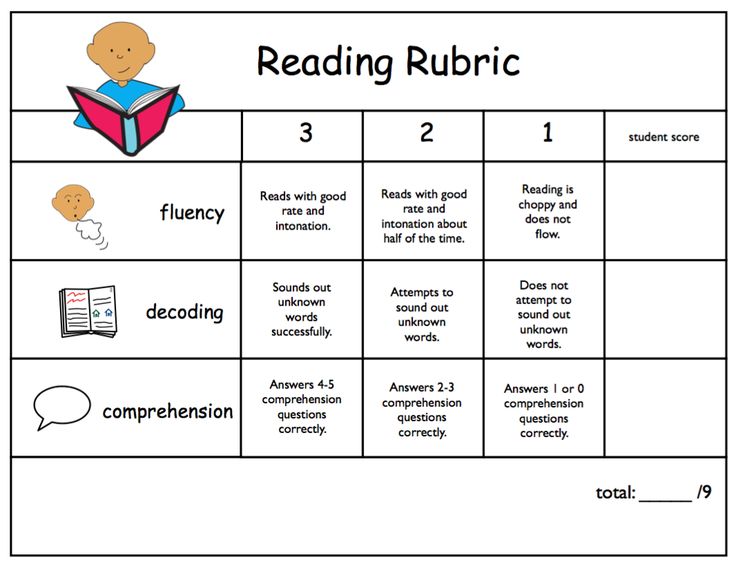

Fluency is the ability to read "like you speak." Hudson, Lane, and Pullen define fluency this way: "Reading fluency is made up of at least three key elements: accurate reading of connected text at a conversational rate with appropriate prosody or expression." Non-fluent readers suffer in at least one of these aspects of reading: they make many mistakes, they read slowly, or they don't read with appropriate expression and phrasing.

Developing reading fluency with Read Naturally Strategy programs

Key Concepts

Why Is Fluency Important?

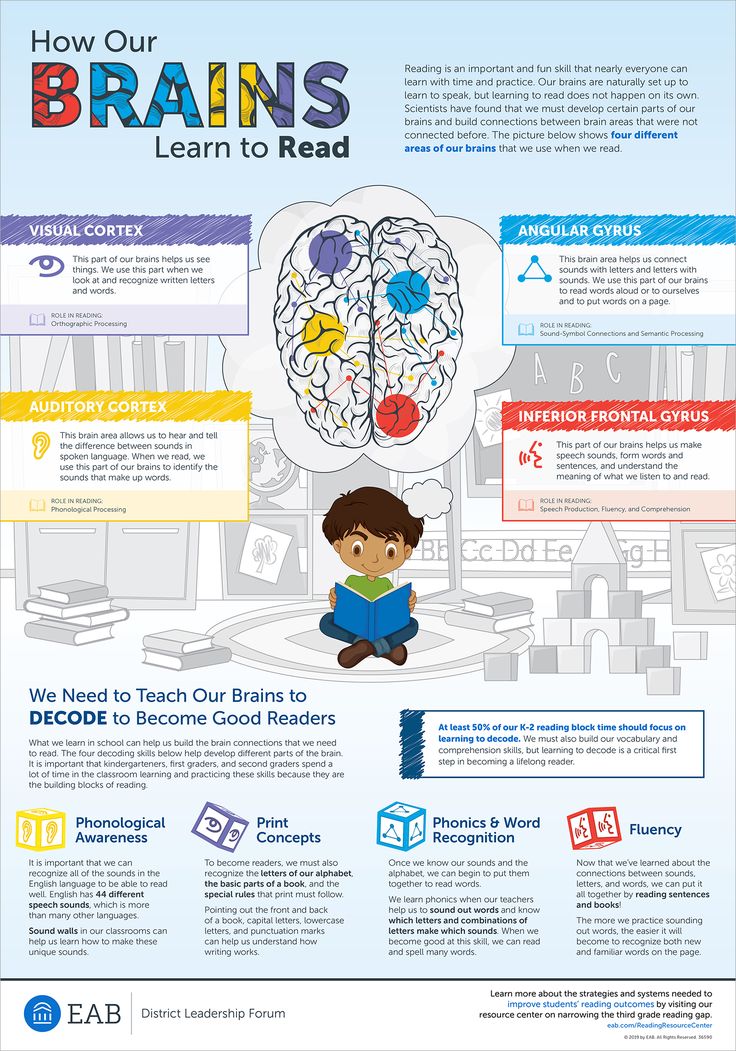

For many years, educators have recognized that fluency is an important aspect of reading. Reading researchers agree. Over 30 years of research indicates that fluency is one of the critical building blocks of reading, because fluency development is directly related to comprehension.

Here are the results of one study by Fuchs, Fuchs, Hosp, and Jenkins that shows how oral reading fluency correlates highly with reading comprehension.

| Measure | Validity Coefficients |

|---|---|

| Oral Recall/Retelling | .70 |

| Cloze (fill in the blank) | .72 |

| Question Answering | .82 |

| Oral Reading Fluency | .91 |

To interpret this type of correlation data, consider that a perfect match would be 1.0. As you can see, oral recall/retelling, fill in the blank, and question answering are all above 0.6, which indicates there is a strong correlation. But oral reading fluency is by far the strongest, with a .91 correlation.

Many researchers, including Breznitz, Armstrong, Knupp, Lesgold, and Pinnell, have found that fluency is highly correlated with reading comprehension—that is, when a student reads fluently, that student is likely to comprehend what he or she is reading.

Why are reading fluency and reading comprehension so highly correlated? Dr. S. Jay Samuels, a professor and researcher well known for his work in fluency, put forth a theory called the automaticity theory. According to Dr. Samuels, people have a limited amount of mental energy. If you want to multitask or to become proficient at a complex task such as reading, you first need to master the component tasks so you can do them automatically. For example, a reader who must focus his or her attention on decoding words may not have enough mental energy left over to think about the meaning of the text. However, a fluent reader who can automatically decode the words can instead give full attention to comprehending the text. To become proficient readers, our students need to become automatic with text so they can pay attention to the meaning.

S. Jay Samuels, a professor and researcher well known for his work in fluency, put forth a theory called the automaticity theory. According to Dr. Samuels, people have a limited amount of mental energy. If you want to multitask or to become proficient at a complex task such as reading, you first need to master the component tasks so you can do them automatically. For example, a reader who must focus his or her attention on decoding words may not have enough mental energy left over to think about the meaning of the text. However, a fluent reader who can automatically decode the words can instead give full attention to comprehending the text. To become proficient readers, our students need to become automatic with text so they can pay attention to the meaning.

See also:

- Determining who needs fluency instruction

- Hasbrouck-Tindal oral reading fluency norms

- Video: Why reading fluency is important

Challenges Faced by Non-Fluent Readers

Students become fluent by reading. Some students learn to read fluently without explicit instruction. For others, however, fluency doesn't develop in the course of normal classroom instruction.

Some students learn to read fluently without explicit instruction. For others, however, fluency doesn't develop in the course of normal classroom instruction.

Research analyzed by the National Reading Panel suggests that just encouraging students to read independently isn't the most effective way to improve reading achievement. Too often, simply encouraging at-risk students to read doesn't result in increased reading on their part. During sustained silent reading, at-risk readers may get a book with mostly pictures and look at the pictures, or they choose a difficult book so they will look like everyone else and then pretend to read.

Even if at-risk students do read, they read more slowly than the other students. In a 10-minute reading period, a proficient reader who reads 200 words a minute silently could read 2,000 words. In the same 10 minutes, an at-risk student who reads 50 words a minute would only read 500 words. This is equal reading time but certainly not an equal number of words read.

These students need to read more, but just asking them to read on their own often doesn't work. The National Reading Panel has concluded that a more effective course of action is for us to explicitly teach developing readers how to read fluently, step by step.

Research-Proven Fluency Strategies

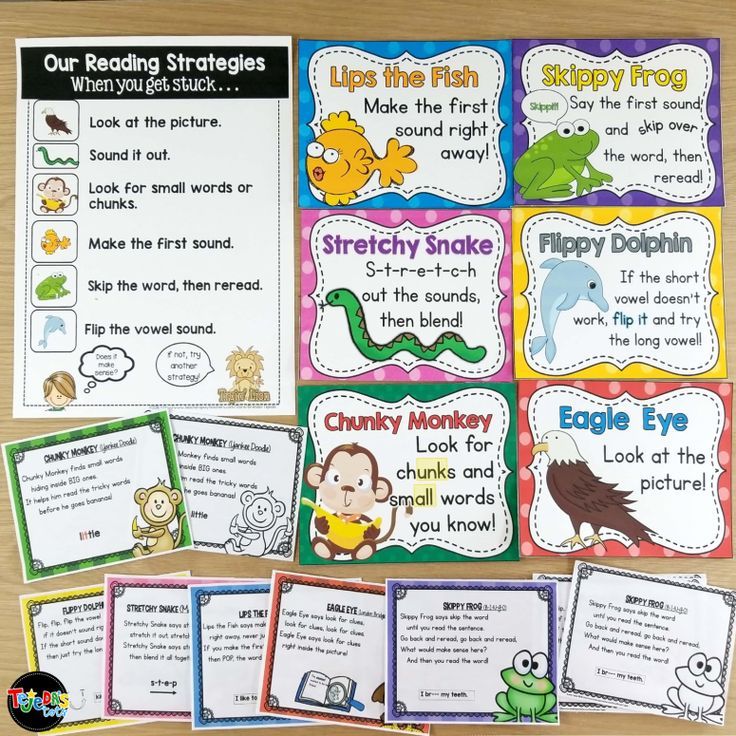

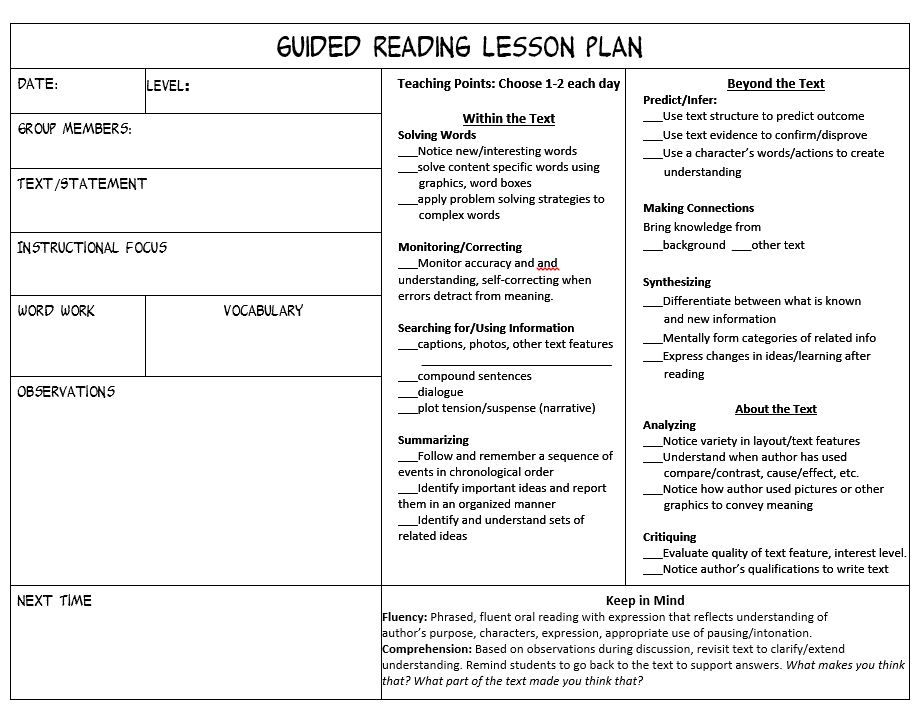

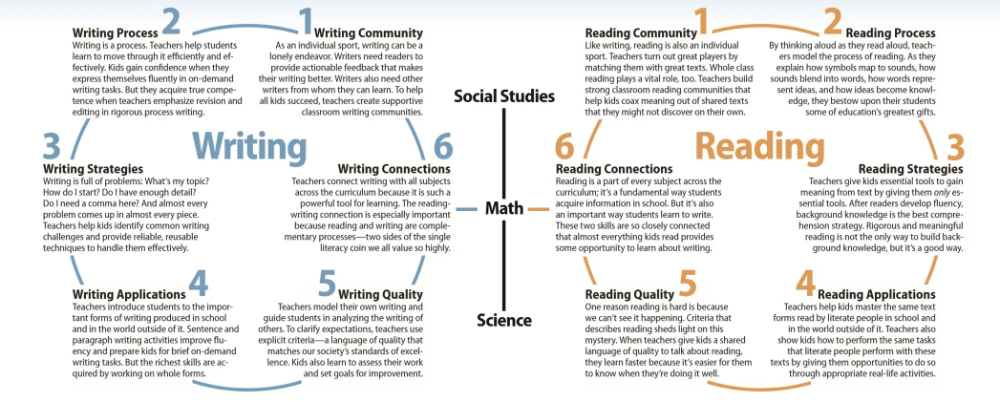

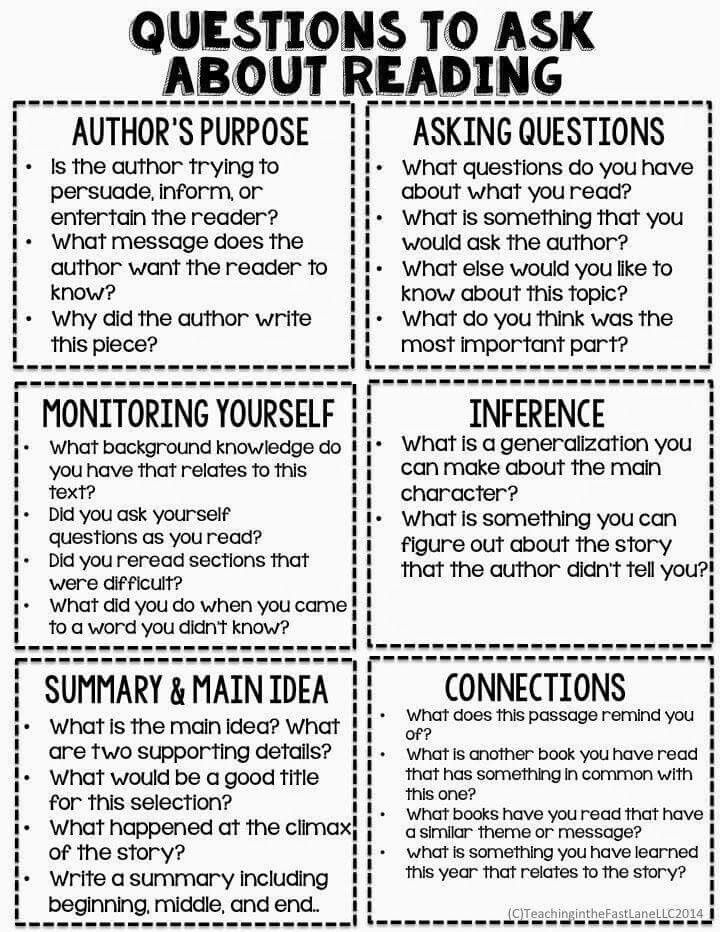

How do we explicitly teach students to read fluently? The National Reading Panel found data supporting three strategies that improve fluency, comprehension, and reading achievement—teacher modeling, repeated reading, and progress monitoring.

Teacher Modeling

The first strategy is teacher modeling. Research demonstrates that various forms of modeling can improve reading fluency. Examples of teacher modeling include:

- Teacher-assisted reading

- Peer-assisted reading

- Audio-assisted reading

Teacher modeling involves more than just listening to someone else read. Students must be actively involved 100 percent of the time and in a multisensory way.

Teacher modeling teaches word recognition in a meaningful context, demonstrates correct phrasing, and gives students practice tracking across the page. A child can benefit from teacher modeling once he or she knows at least 50 sight words and has a good sense of beginning sounds.

The reading rate of the model reader is important. Christopher Skinner, a reading researcher, found that students who read lists of words with him slowly were more fluent with the words than students who read with him at a faster rate. The slower rate enables students to learn new words and clarify difficult words. As students learn more words, they naturally become more fluent.

Another form of modeling is the neurological impress method. In the neurological impress method, a proficient and a struggling reader read together from a passage, with the more able reader reading near the rate of the struggling reader. Heckelman (1969) showed that after 29 15-minute sessions, 24 seventh- through ninth-grade boys, who were an average of 3 years behind in reading, gained an average of 1. 9 years in reading based on the Oral Gilmore and the California Achievement Test.

9 years in reading based on the Oral Gilmore and the California Achievement Test.

Repeated Reading

Another technique that research has shown significantly builds reading fluency is repeated reading. In fact, the National Reading Panel says this is the most powerful way to improve reading fluency. This involves simply reading the same material over and over again until accurate and expressive.

In the 1970s, LaBerge and Samuels studied what happens when students read passages over and over again. They found that when students reread passages, they got faster at reading the passages, understood them better, and were able to read subsequent passages better as a result of the repeated reading.

Repeated reading is a form of mastery learning. The students read the same words so many times that they begin to know them and are able to identify them in other text. Besides helping students bring words to mastery, repeated reading changes the way students view themselves in relation to the act of reading.

Progress Monitoring

People who play video games are presented with a specific goal and with immediate, relevant feedback about their progress toward that goal. This combination of having a goal and getting feedback on progress can be very motivating.

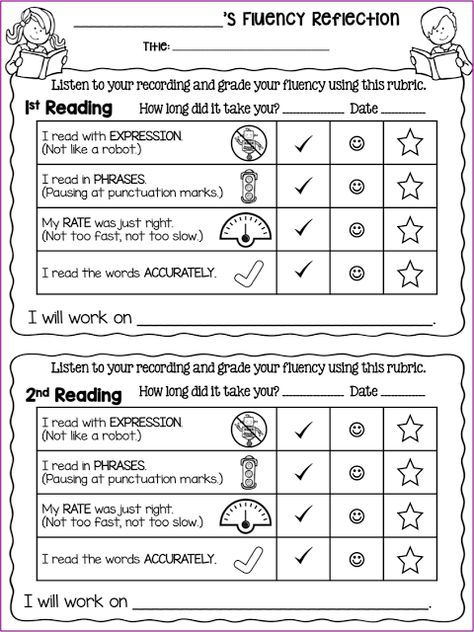

Progress monitoring takes advantage of this combination to motivate students to read. You give students a specific, individual reading goal, and you tell them exactly how you're going to know they've met it. Then, you give them the means to measure how they're doing. Finally, you make it simple enough that they'll know they've met their goal even before you do. This progress monitoring is what motivates students to practice reading the same story over and over until achieving mastery.

Developing Reading Fluency With Read Naturally Strategy Programs

The research-based Read Naturally Strategy combines these three strategies into highly effective programs that accelerate reading achievement. Students become confident readers by developing fluency, phonics skills, comprehension, and vocabulary while reading leveled text. The time-tested intervention programs engage students with interesting nonfiction stories and yield powerful results.

Students become confident readers by developing fluency, phonics skills, comprehension, and vocabulary while reading leveled text. The time-tested intervention programs engage students with interesting nonfiction stories and yield powerful results.

Learn more about the Read Naturally Strategy

Research basis for the Read Naturally Strategy

The Read Naturally Strategy is available in a variety of formats:

Choosing the right Read Naturally Strategy program

| One Minute Reader® Structured, supplemental reading program for developing literacy skills independently. Available in these formats: One Minute Reader Live (component of web-based Read Live for supplemental reading at school) One Minute Reader books/audio CDs (for a school-to-home checkout program) |

Bibliography

Armstrong, S. W. (1983). The effects of material difficulty upon learning disabled children's oral reading and reading comprehension. Learning Disability Quarterly, 6, pp. 339–348.

Learning Disability Quarterly, 6, pp. 339–348.

Breznitz, Z. (1987). Increasing first graders' reading accuracy and comprehension by accelerating their reading rates. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(3), pp. 236–242.

Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Hosp, M. K., & Jenkins, J. R. (2001). Oral reading fluency as an indicator of reading competence: A theoretical, empirical, and historical analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5(3), pp. 239–256.

Heckelman, R. G. (1969). A neurological-impress method of remedial-reading instruction. Academic Therapy Quarterly, 5(4), pp. 277–282.

Hudson, R. F., H. B. Lane, and P. C. Pullen. (2005). Reading fluency assessment and instruction: What, why, and how. Reading Teacher 58(8), pp. 702-714.

Knupp, R. (1988). Improving oral reading skills of educationally handicapped elementary school-aged students through repeated readings. Practicum paper, Nova University (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 297275).

ED 297275).

LaBerge, D., & Samuels, S. J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cognitive Psychology, 6, pp. 292–323.

Lesgold, A., Resnick, L. B., & Hammond, K. (1985). Learning to read: A longitudinal study of word skill development in two curricula. In G. Waller & E. MacKinon (eds.), Reading research: Advances in theory and practice. New York, NY: Academic Press.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Pinnell, G. S., Pikulski, J. J., Wixson, K. K., Campbell, J. R., Gough, P. B., & Beatty, A. S. (1995). Listening to children read aloud: Data from NAEP's integrated reading performance record (IRPR) at grade 4 (NCES Publication 95-726). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Educational Statistics.

Samuels, S. J. (2002). Reading fluency: Its development and assessment. In A. E. Farstrup & S. J. Samuels (eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction, 3rd ed., pp. 166–183. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Samuels, S. J. (1997). The method of repeated readings. The Reading Teacher, 50(5), pp. 376–381.

Samuels, S. J. (2006). Towards a model of reading fluency. In S. J. Samuels and A. E. Farstrup (eds.), What research has to say about fluency instruction. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Samuels, S. J. (1997). The method of repeated readings. The Reading Teacher, 50(5), pp. 376–381.

Skinner, C. H., Logan, P., Robinson, S. L., & Robinson, D. H. (1997). Demonstration as a reading intervention for exceptional learners. School Psychology Review, 26(3), pp. 437–447.

Why is Reading Fluency So Important? • Teacher Thrive

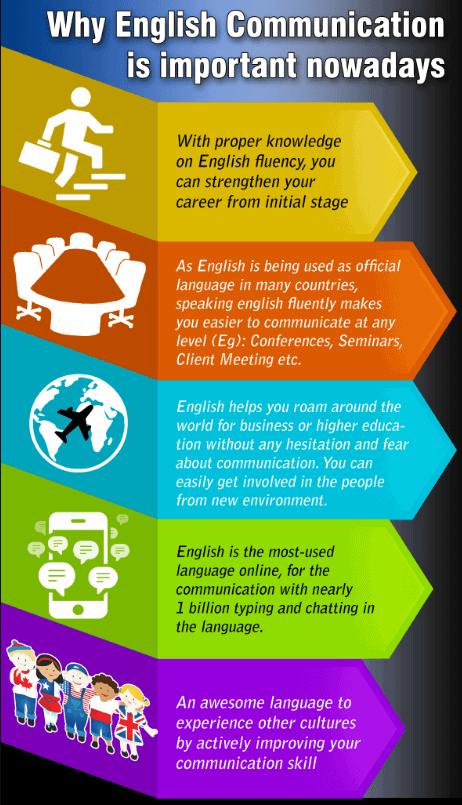

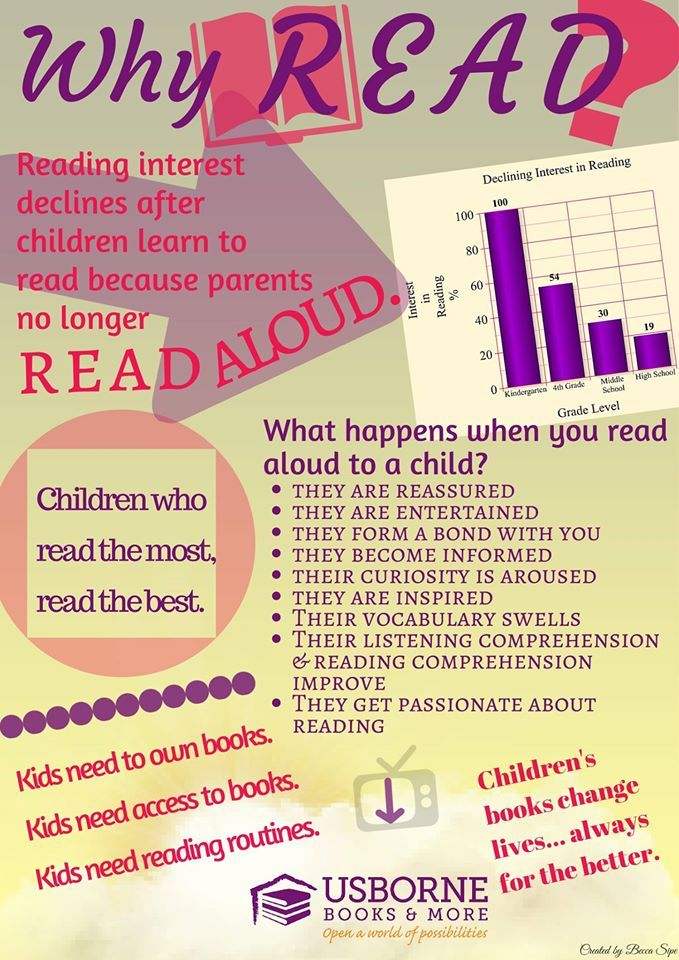

Reading fluency is important because it is one of the most reliable determiners of a student’s ability to comprehend text. In fact, reading fluency has been called the bridge between decoding and comprehension (Chard & Pikulski 2005). If you’re neglecting to incorporate meaning fluency instruction within your reading program (don’t worry, you’re not alone), I have some pretty staggering statistics I would like to share with you!

In fact, reading fluency has been called the bridge between decoding and comprehension (Chard & Pikulski 2005). If you’re neglecting to incorporate meaning fluency instruction within your reading program (don’t worry, you’re not alone), I have some pretty staggering statistics I would like to share with you!

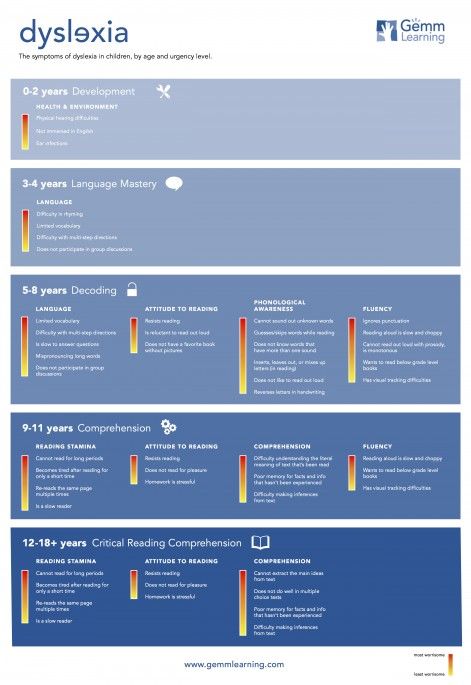

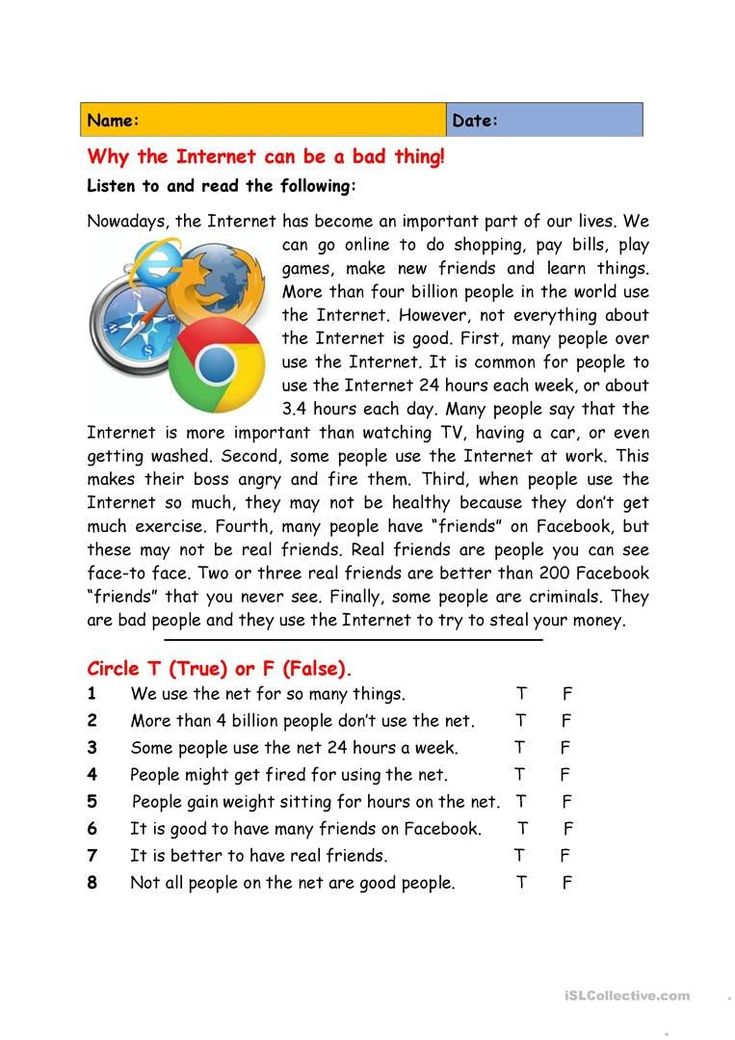

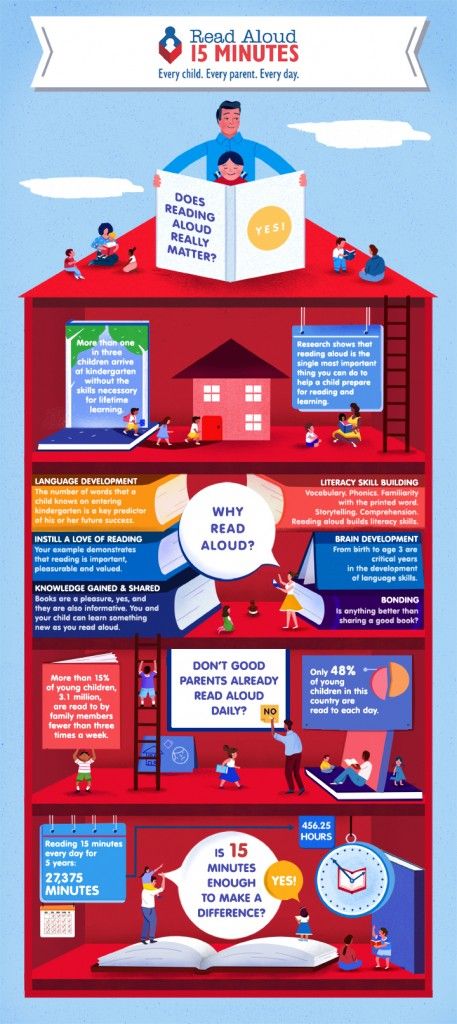

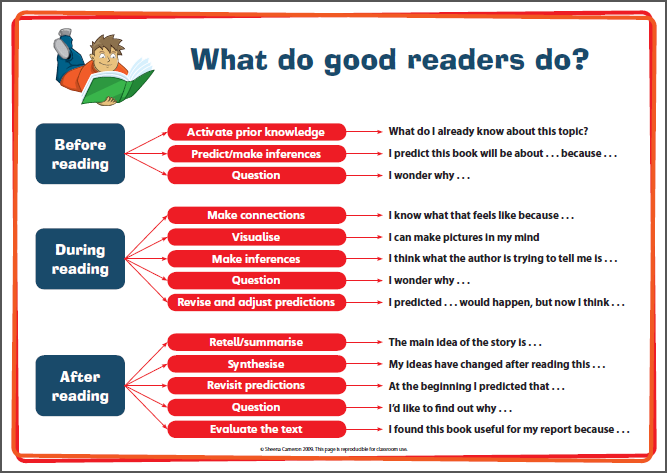

The graphic below contains data from years of research and a study published in the Scientific Studies of Reading (Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Hosp, M. K., & Jenkins, J. R. 2001) The study compared the participants’ ability to complete various tasks with the participants’ comprehension of the text. The following data expresses the correlation strength of each of these measures to reading comprehension. Correlations are expressed with validity coefficients, which are numbers that quantify the strength that two things correlate to each other. Keep in mind that a validity coefficient of 1.0 represents a perfect correlation.

The first task we will look at is oral recall or retelling. This is where a reader orally recalls or retells what he/she read. For this measure, the validity coefficient is 0.70. This is to say that a readers’ ability to accurately recall or retell a text has a 0.70 correlation to her ability to comprehend.

This is where a reader orally recalls or retells what he/she read. For this measure, the validity coefficient is 0.70. This is to say that a readers’ ability to accurately recall or retell a text has a 0.70 correlation to her ability to comprehend.

The study also looked at cloze activities. These are tasks that require readers to complete missing words from a text. The validity coefficient for this measure was 0.72.

Researchers also examined readers’ ability to answer questions about a text. This measure had a validity coefficient of 0.82.

Finally, we have oral reading fluency. The ability to read fluently had the strongest correlation to reading comprehension. This validity coefficient was 0.91.

Incorporating Reading Fluency into Your Classroom

Reading fluency gets a lot of attention in the primary grades. Unfortunately, students in grades 4-8 who still struggle with fluency don’t get the attention they need. Many of these students need explicit instruction and meaningful practice for fluency in order to become competent readers.

It’s not easy for teachers who work with older students to fit fluency practice into their already tight schedules. Here are a few fluency activities that you can easily work into your day.

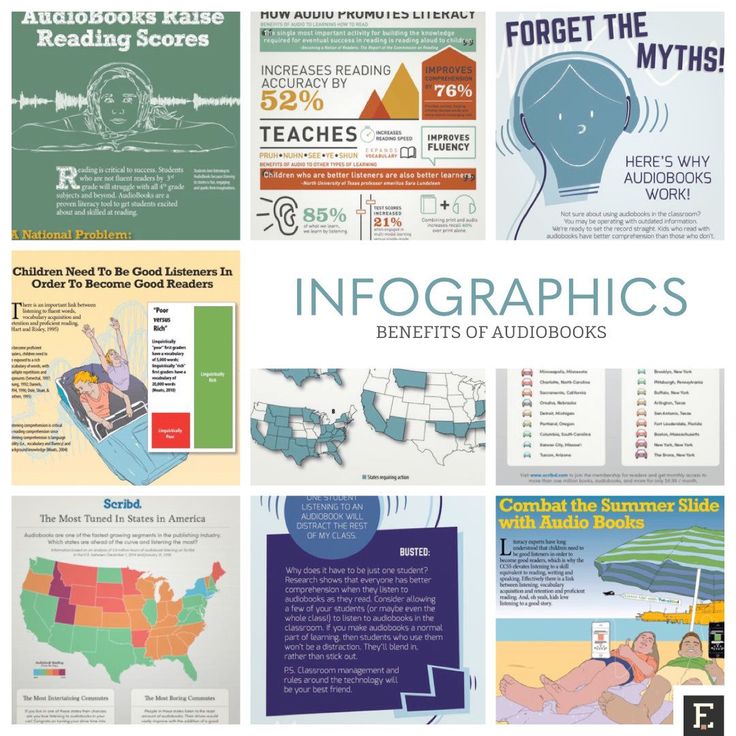

Audio-Assisted Reading

Audio-assisted reading is when you have a student follow along in a text while listening to an audio recording (audio CD, audiobook, or iPod). After the student gains confidence using the audio version, he/she can then transition to reading the text independently.

This is such an effective way for improving word recognition, as well as building proper phrasing and expression. This is also a great strategy to use in content areas such as science and social studies; oftentimes, publishers include the audio version of the textbook for teachers to use. You can also record your own audio-versions of close reading passages or short stories for your students to use. If you’re doing a novel study, check your public library for audio CDs for the title you are using. You can also make a listening center in your classroom using jack extenders so that multiple students can read along at the same time.

You can also make a listening center in your classroom using jack extenders so that multiple students can read along at the same time.

Poetry Performances

Holding “poetry slams” is a perfect disguise for fluency practice. Find relatively long poems (haikus might not be the best choice:-) from your favorite authors that are age-appropriate for your students. I love using work from Shel Silverstein or Jack Prelutsky for younger students. If you teach middle school students you may want to look into poems by Langston Hughes or Edgar Alan Poe. Poetry offers smaller, non-threatening text for students to work with, and more reluctant readers may be more motivated by the creativity and playfulness that the genre offers. The assonance and alliteration of poetry also make this medium perfect for fluency practice.

Gather a large selection of poems and have your students choose one they would like to practice and eventually “perform”. Performances can take the place as simple readings in front of the class, in a small group, or with a partner. Students can also make a PowerPoint presentation that they narrate by reading the poem. Presenting options are endless; the most important thing is to get them reading and rereading the poem in order to improve fluency.

Students can also make a PowerPoint presentation that they narrate by reading the poem. Presenting options are endless; the most important thing is to get them reading and rereading the poem in order to improve fluency.

Students LOVE readers’ theater. They get so excited by the idea of performing in a play, even though this activity does not require students to memorize any text. Unlike a real play, there are no costumes, props, or sets needed.

There are several free resources if you’re looking for scripts. Dr. Chase Young has written several for younger students, and Aaron Shepard has some great scripts for older students. You can also write your own scripts, or even have your students write their own, based on picture books or a chapter from a novel. BONUS: Aaron Shepard’s site has a video of The Chamber Readers reading one of his scripts; what a perfect way to provide a model for your students!

Partner Reading

This strategy pairs two readers together with the same piece of text. You can pair your students by listing your class in order from highest to lowest according to reading ability. Then divide the list in half. Place the top student in the first list with the top student in the second list. Continue until all students have been paired up.

You can pair your students by listing your class in order from highest to lowest according to reading ability. Then divide the list in half. Place the top student in the first list with the top student in the second list. Continue until all students have been paired up.

Students in the pairs will take turns reading the text, by dividing it into paragraphs, subheadings, pages, etc. The students can also read the text simultaneously (choral reading). I really like this strategy for reading within science and social studies books, which can be particularly difficult for students. However, you can use parter reading for any text.

Repeated Readings

Timed repeated readings are a systematic way for students to work on fluency, and it offers a great opportunity for students to monitor their own progress. Students are given a passage they have never read before. They will complete a “cold reading”, where they read for exactly one minute. The total words read (minus certain errors) are counted and this is their “cold score”, which they graph on a chart. They then practice reading the passage and have opportunities to listen to it read by a fluent model. Following practice and modeling, the students will then complete a “hot reading”, which is another one-minute session. Again, they count the total words read (minus miscues) to find their “hot score”. Their hot scores are then graphed above their cold scores.

They then practice reading the passage and have opportunities to listen to it read by a fluent model. Following practice and modeling, the students will then complete a “hot reading”, which is another one-minute session. Again, they count the total words read (minus miscues) to find their “hot score”. Their hot scores are then graphed above their cold scores.

If you are looking for a robust and systematic way to utilize repeated readings, check out the program Flow Reading Fluency Digital!

Development of reading fluency in primary school students

Reading can be compared to the main road in the land of knowledge. All subsequent education - mathematics, biology, social sciences will be based on the child's ability to understand what is written, use the language, on his ability to isolate the meaning of the written text.

Reading is one of the complex and significant forms of human mental activity that performs psychological and social functions. Reading is a complex intellectual process, multi-level and multi-link in structure, active in flow.

Reading is a complex intellectual process, multi-level and multi-link in structure, active in flow.

In order to read correctly and at high speed, you need the coordinated work of several analyzers: visual, speech-motor, speech-auditory. The process of reading begins with visual perception, discrimination and recognition of letters. In the future, the letters are correlated with the corresponding sounds and the sound-producing image of the word is reproduced, its reading is carried out. And, finally, due to the correlation of the sound form of the word with its meaning, the understanding of what is being read is carried out.

Reading skill characteristics include:

- correctness;

- consciousness;

- fluency;

- expressiveness.

Without the ability to read clearly, without errors, expressively, the student will not understand the meaning of the text, and the main goal of reading will not be achieved. Therefore, working on the technical side of the reading process, on developing a fairly fast pace, is very important.

Reading fluency is the normal pace of reading that contributes to the conscious and correct perception of the text.

In elementary school students, and especially in students with speech disorders, very often this skill is not sufficiently formed. There are few methodological developments on this problem.

The purpose of work is to develop reading fluency in primary school students.

The implementation of this goal was carried out in the process of solving the following tasks:

- Reading literature on this topic.

- Selection of special exercises aimed at developing fluent reading.

- Creation of didactic games and visual material.

- The use of special exercises, didactic games and aids in speech therapy classes to overcome dyslexia.

- Development of a methodology for developing reading fluency in younger students and the implementation of experimental teaching of students.

- Formation in children of interest in books, in independent reading.

Based on the methodological developments of Lalaeva R.I., Kornev A.N., Kostromina S.N., Nagaeva L.G., Kozyreva L.M., Gorodilova V.I. and taking into account the principles of consistency and systematicity, accessibility and specificity, a methodology was created, the purpose of which is to help students with speech disorders (fuzzy, blurry articulation, deficiencies in the development of phonemic and lexico-grammatical aspects of speech) in mastering the skill of fluent reading.

To achieve this goal, it is necessary that parallel work be carried out in the following areas:

- development of phonemic analysis, synthesis, representations;

- development of phonemic perception, differentiation of letters denoting acoustic-articulatory close sounds;

- development of mobility of the articulatory apparatus, the formation of the skill of pronunciation of words of a complex syllabic composition;

- activation and replenishment of vocabulary;

- improvement of the grammatical structure of speech;

- development of visual perception, attention and memory;

- formation of activity, independence, skills of control and self-control.

This technique is a system of exercises and speech games presented on cards (size 10*15) and designed as individual albums, as well as a set of visual material for group reading. The addressee is students of 2-3 grades. Selectively, the methodology can also be used in work with students of the 1st and 4th grades.

The optimal conditions for correctional and developmental work are the joint activities of students, teachers, speech therapists and parents. Classes are recommended to be carried out 3 times a week, lasting 10-15 minutes (with individual lessons 5-10 minutes), with daily training exercises at home.

Based on the tasks listed above, 2 sections of the methodology were developed.

The first section is aimed at developing the skill of fluent reading through various, unusual exercises with syllables, words, sentences and texts, the implementation of which in a relaxed atmosphere creates a positive emotional background and ensures the formation of a number of perceptual and mental operations and abilities, which, as components components are included in the reading process. In other words, the child with difficulty in reading is encouraged to take a break from this "tedious" activity for a while and instead engage in fun exercises with verbal material; the implementation of these exercises leads to the formation of a number of important operations that underlie reading; having mastered them, the child subsequently reads much better.

In other words, the child with difficulty in reading is encouraged to take a break from this "tedious" activity for a while and instead engage in fun exercises with verbal material; the implementation of these exercises leads to the formation of a number of important operations that underlie reading; having mastered them, the child subsequently reads much better.

The proposed set of exercises is aimed at the formation and automation of reading skills in the following sequence:

1) reading syllables;

2) reading words;

3) reading phrases and sentences;

4) reading tongue twisters and tongue twisters;

5) reading texts.

Here are some examples of cards:

1. Reading open syllables .

Tasks:

- read syllables in green, red, etc.;

- read syllables consisting of large letters, from letters of small print;

- read syllables with the vowel A, with the vowel I, etc.;

- come up with words that begin with these syllables;

- read the syllables in columns, line by line;

- read 1 line of syllables in one breath, 2 lines of syllables;

- read the syllables in columns from bottom to top, in lines from right to left;

- read the syllables for a while.

2. Reading words

3. Reading sentences

4. Reading tongue twisters

| Sha-sha-sha - mother washes the baby Shu-shu-shu - I'm writing a letter Ash-ash-ash - Vova has a pencil Zha-zha-zha - the hedgehog has needles Zhu-zhu-zhu - let's give milk to a hedgehog Cha-cha-cha - a candle burns in the room Choo-choo-choo - I knock with a hammer Och-ouch-ouch - the night has come Scha-scha-scha - we bring home a bream Ash-ash-ash - we put on a raincoat Lo-lo-lo - it's warm outside Lu-lu-lu - the table is in the corner Ul-ul-ul - our chair broke Ra-ra-ra - it's time for Katya to sleep Ro-ro-ro - there is a bucket on the floor Ry-ry-ry - mosquitoes fly |

5. Text reading

| Rearrangers Read the poem |

| On a winter evening… we return… from a ski… walk…. We are... out of the birch... grove. In the distance one could see the neighboring ... village .... The road took us to a little... rivers.... It left... a steep climb up the hill... - and we are at school... . On the square ... near school ... a teacher was waiting for us ... from groups ... guys. Weekend… day we always spend… for fresh… air…. Tomorrow with new ... strength ... for learning. |

The second section is devoted to developing the skill of fluent, clear reading in speech therapy classes to overcome lexical and grammatical disorders and fill in the gaps in the development of the sound side of speech (I and II stages of correctional work).

When conducting classes with a group of children, a speech therapist very often has to deal with a lack of practical material for students to read. Therefore, the second section includes exercises aimed at correcting and improving various aspects of speech:

Therefore, the second section includes exercises aimed at correcting and improving various aspects of speech:

1. Development of a clear auditory-pronunciation differentiation of oppositional sounds on the material:

- syllables;

- words;

- phrases and sentences;

- tongue twisters and tongue twisters;

- text.

2. Activation and replenishment of the dictionary both by accumulating new words that are different parts of speech, and by developing the ability to actively use various methods of word formation. Students should be encouraged to read:

- single root words;

- words formed with the help of different prefixes from the same root;

- words that have the same prefixes, but different roots;

- words formed with the help of suffixes from one root;

- words that have the same suffixes but different roots;

- different words with the same endings;

- antonyms, synonyms.

3. Improving the grammatical structure of speech by students mastering word combinations, the connection of words in a sentence, models of various syntactic constructions.

Practical reading material includes exercises to develop the following skills:

- use of prepositional case constructions;

- the use of nouns in the singular and plural;

- agreement of nouns with adjectives, numerals;

- differentiation of verbs singular. and many others. numbers, changing past tense verbs by gender;

- the use of sentences of complex syntactic constructions.

Thus, the second section presents exercises that develop not only reading fluency, but also one of its most important qualities - awareness.

Examples of reading cards:

1. Differentiation C - G

a) on the material of words

| - compare pairs of words by spelling and meaning. Orally make up a sentence with each word. slide - crust grotto - mole - read the words without errors Chickens, kettlebell, injection, caviar, road, shop, pocket, rope, - complete the words by adding the syllable ha or ka Ru… nit… …zeta kocher… ma…zin |

b) on the material of phrases

Gift, to give, donated.

Offended, offended, offended.

Runaway, runaway, runaway.

Gait, walking, marching.

Clean, clean, clean.

Greenery, greenery, greenery.

Freshness, refresh, fresh.

Fun, have fun, cheerful.

Freeze, freeze, frosty.

Repair deformed text using words with the same root.

It's snowing. The lungs smoothly fall to the ground ... . And now they have already dressed in ... a fur coat on the roofs of houses, streets, squares. Toddlers expanse. Ka-tyat ... clods, they mold fat ones . ...

...

3. The use of words in the accusative and dative cases

| Read the sentences by changing the words in brackets. Tell me (fairy tale, little sister). |

Related:

Building Reading Literacy in Elementary School Students

Tips for Developing Reading Fluency in Your Child - Child Development

Every parent of an aspiring reader knows that learning letters and words is only the beginning. As your child stumbles through every sentence, works on vocabulary, and his confidence alternates with frustration, you may be wondering, “When will my child finally be able to read well?”

Learning to read fluency will take longer than just reading sentences sequentially, as it involves reading at high speed, with conscious reading comprehension and confidence. To make a child a good reader, the ability to decipher written words alone is not enough. Even more important for successful reading is the ability to recognize and read words easily (without any effort) and with feeling. Research has shown that reading fluency is a predictor of overall academic excellence, and that a lack of verbal fluency often results in comprehension problems along the way.

To make a child a good reader, the ability to decipher written words alone is not enough. Even more important for successful reading is the ability to recognize and read words easily (without any effort) and with feeling. Research has shown that reading fluency is a predictor of overall academic excellence, and that a lack of verbal fluency often results in comprehension problems along the way.

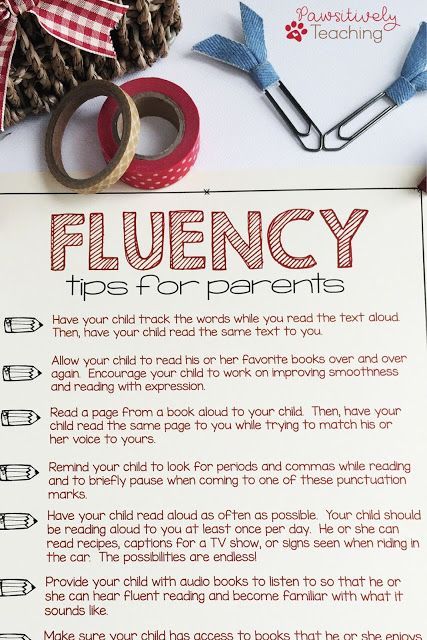

Here are five expert tips to help you develop your child's reading fluency.

Read aloud with expression. Jesse Wise from the USA, as a "model parent educator" and homeschooling consultant, emphasizes that the process of modeling reading fluency is the most useful thing that adults can do for their children to help achieve good reading speed. Children need to hear texts read smoothly and easily. It is also very important for them to hear examples of reading with expression. When you read aloud, don't be afraid to emphasize emotions that reflect the tone of the text, such as excitement or sadness, joy or surprise. Show your child that a correctly read word helps to reveal its meaning.

Show your child that a correctly read word helps to reveal its meaning.

Practice and more practice. Reading, like any other skill, requires repeated, consistent practice to become perfect. The goal of reading fluency is to read so smoothly and easily that it happens automatically and effortlessly. The only thing it takes is time and effort.

Wise says: “Athletes and musicians practice a lot to achieve mastery. I think the same strategy works for reading as well. Fluency is best developed by repeatedly reading the same passage aloud until fluency is achieved. To do this, simulate reading aloud using a specific piece of text. Choose a small paragraph of about a hundred words. Have your child read it several times - up to four times in one go.

Pinpoint problems. There are three main elements of reading fluency: speed, accuracy, and prosody (how well the reader uses changes in tone of voice, intonation, accents, stresses, pauses, etc. to convey meaning and emotion). When you listen to your child read aloud, pay attention to all three components and try to understand which of them is having difficulty.

to convey meaning and emotion). When you listen to your child read aloud, pay attention to all three components and try to understand which of them is having difficulty.

Wise says that fluency problems can manifest themselves in a variety of ways. “Does the child guess about an unfamiliar word from the context or from the phonetic sound? Is it hard for him?” Weisz asks. One way to find out if his current reading comfort level is exceeded is to count the number of words he or she stumbles over. According to Weiss, “If a child misreads more than one out of every 20 words, he will focus on word recognition rather than fluency”—and therefore have difficulty.

Make reading fun. While practice is important, don't make reading a chore that your child will simply become afraid of. Instead of turning this process into a fixed-schedule routine, try turning reading aloud into a series of fun activities with your child.

If your child is a young, up-and-coming actor, create a theatrical performance from a favorite story.