Why rhyming is important

Module: Having Fun with Phonemic Awareness: Resources for Early Learning

Home / Educators / Professional Development (3 - 5 YEARS) / Having Fun with Phonemic Awareness

- Introduction

- Play with Rhymes

- Play with Sounds and Words

- Try It

- Wrap Up

- Standards

Resources (PDFs)

- Self-Assessment

- Learning Log

- Mystery Sound Games

- Best Practices

- Standards

Vocabulary

- phonemic awareness: the ability to recognize that spoken words are made up of separate sounds (phonemes, the smallest units of sound), and to manipulate those sounds in speech

- phonics: the understanding that letters represent the sounds in words

- phonemes: the smallest units of sound

- phonological awareness: the ability to recognize that words are made up of a variety of sound units

- nonsense words: made-up words, used for the phonemic principle being taught

- sound matching: the ability to match words that begin or end with the same sound

Play with Rhymes

Before watching this video, read the text below. When instructed, watch the video from the beginning to end.

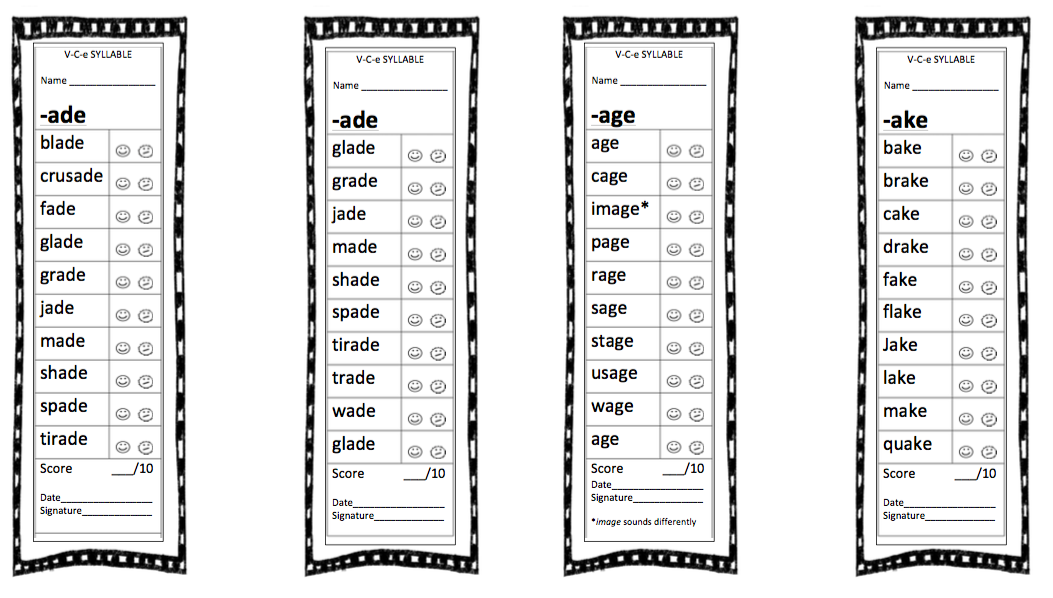

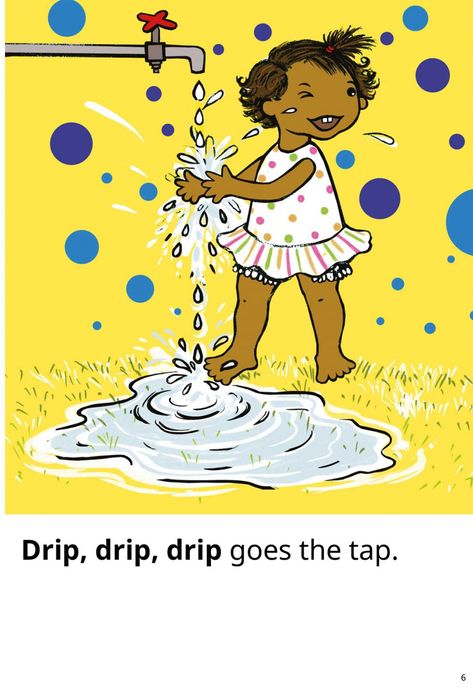

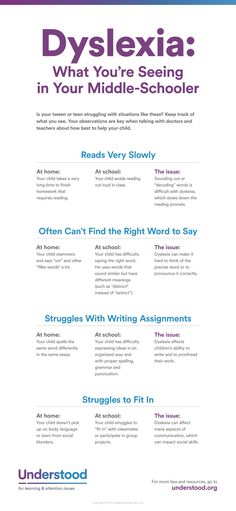

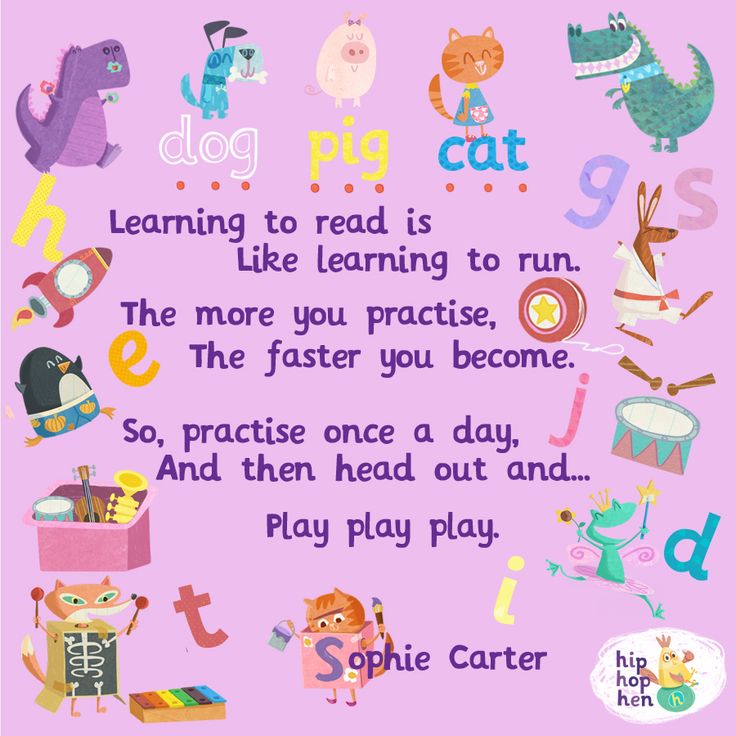

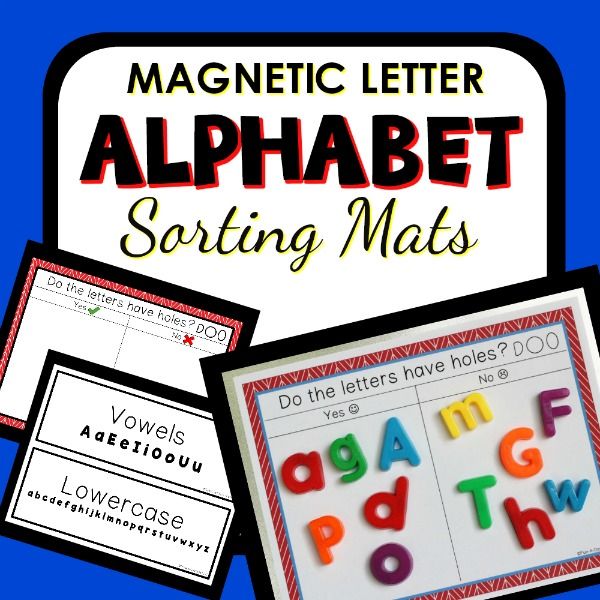

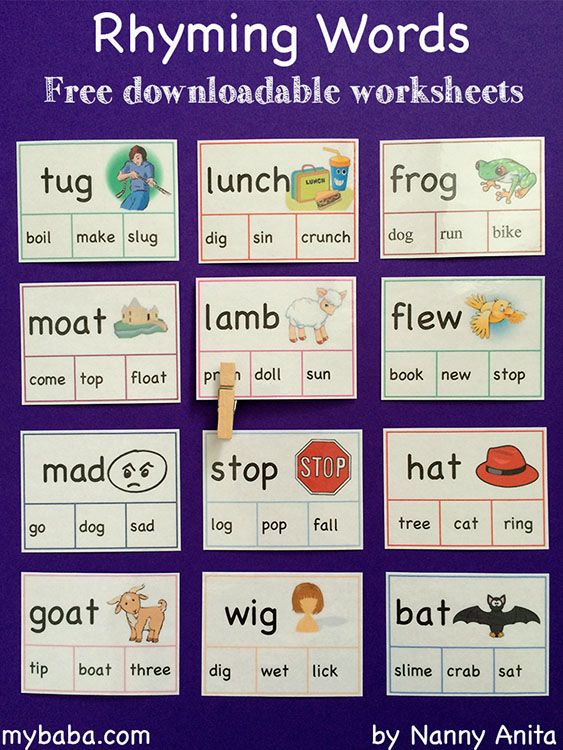

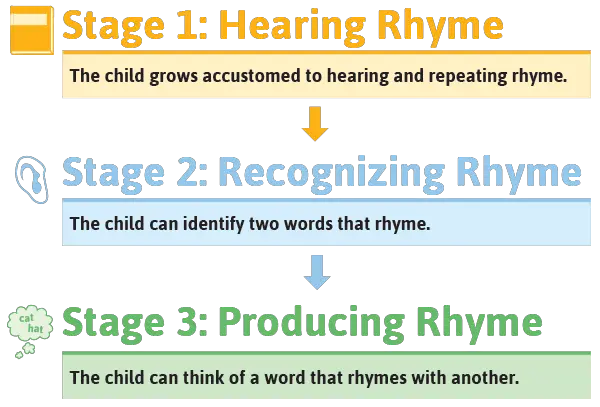

Rhyming is a helpful first step toward phonemic awareness. When children play with rhymes, they listen to the sounds within words and identify word parts. For example, the /at/ sound in the word mat is the same /at/ sound in cat, rat, sat, and splat. Children typically learn to recognize rhyming words first and generate their own rhymes later. It is important to recognize that these skills are not always learned on a schedule. For some children, recognizing rhyme can be difficult. You can use different methods to help develop children’s skills.

- Have children listen to and identify rhymes in books. Before reading, ask children to listen for rhyming words and raise their hands when they hear them. Or, stop before you get to the rhyming word and have children supply it.

- Prompt children to produce words that rhyme

. Both real words and “nonsense words” are useful, such as Peggy and leggy; turtle and Yertle.

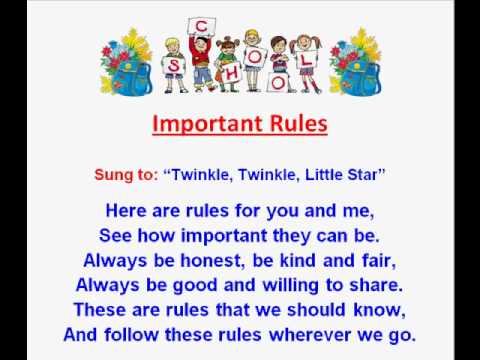

- Provide opportunities to recite rhymes in song. Music is a natural part of a child’s world. They can be active participants, clapping, snapping, and adding their own motions to songs. For example, “I’m a little lizard, my oh my! My skin has scales, it’s nice and dry.”

In this video, you’ll see educators use rhyming games, songs, and read-aloud books to teach phonemic awareness skills. As you watch, look for effective strategies used by the educators in the video and jot down answers to this viewing question in your Learning Log.

- How do the educators use rhyme to develop children’s phonemic awareness skills?

Review

What is phonemic awareness and why is it important?

- Phonemic awareness is the ability to recognize that words are made up of separate sounds.

- Phonemic awareness also includes the ability to manipulate sounds in speech.

- Phonemic awareness lays the foundations for learning to read and write.

- Research shows that children with good phonemic awareness skills are more successful in learning to read and write.

- Phonemic awareness can be integrated into other learning areas. In the video, children learned about reptiles in “Rhyming Reptiles,” while also learning phonemic awareness by suggesting rhyming words (snake, take; lizard, blizzard).

Why is rhyming an important skill for children to learn?

- Recognizing rhyming words is a basic level of phonemic awareness.

- Rhyming requires that children listen closely for sounds within words.

- Children who recognize rhyme learn that words are made up of separate parts.

- An early goal is to have children listen to a pair of words and decide whether or not the words rhyme.

- Eventually, the goal is to have children generate words that rhyme.

How can educators teach rhyming skills to children?

- Use music and songs to teach rhyme. Sing active songs that invite children to use movement. Fingerplays such as “Itsy Bitsy Spider” invite active participation in a rhyming game.

- Use books and read-aloud stories to teach rhyme. Rhyming texts, both fiction and nonfiction, support literacy in general and help children learn phonemic awareness skills.

- Before reading, ask children to listen for words that rhyme.

- Encourage children to raise their hands when they recognize a rhyming word.

- Stop and have children supply a rhyming word in the text.

- After you have read a poem or story aloud, ask for rhyming words. (What word rhymes with mittens?)

- Use games to teach rhyme.

- Toss a beanbag onto a picture grid. Have children think of a word that rhymes with the picture (fish, wish; goat, boat

).

- Play “I Say Night.” Teach children to respond with a rhyming word: I say night. You say (right.) Or I say bread. You say .

- Play rhyming partners. As children “buddy up” for an activity, give one child a random word, for example, mitten. The first child to suggest a rhyming word becomes that child’s buddy.

- Toss a beanbag onto a picture grid. Have children think of a word that rhymes with the picture (fish, wish; goat, boat

).

- Use nursery rhymes to teach rhyme. Traditional nursery rhymes are fun to teach. Children can learn them quickly and enjoy repeating them.

- Make a chart of rhyming words. (If possible, connect the words to concepts being taught in the curriculum, such as colors, plants, weather, etc.) Add a word each day (pink, clink, wink, sink, blink). Once you have a bank of words, have children create their own silly rhymes. (Wink, wink, wink. Watch me blink.)

- Have fun with rhymes. Children enjoy saying rhymes in different voices. Whisper them, shout them, sing them, and chant them.

- Children need not suggest real words when supplying rhymes. Nonsense words (alligator, shmalligator) enable children to focus on the sound rather than the meaning. In time, children will develop the ability to generate real words that begin with the same sound, contain the same sound, or end with the same sound.

Reflect

Think about the learning environment at your own program as you answer these reflection questions in your Learning Log.

- What daily activities do you do with children to teach phonemic awareness?

- What did you learn that you will take back to your learning environment and put into practice?

NEXT

Why Is Rhyming Important? - The Measured Mom

PSPKK123November 2, 2016 • 37 Comments

This post contains affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Sharing is caring!

Why is rhyming important? We’ve got the answer!

image via iStock(This post contains affiliate links. )

)

Do you know what’s one of the best predictors of how well a kindergartner will learn to read? It’s if he knows his nursery rhymes.

Jack and Jill went up the hill.

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall.

Baa, baa, black sheep, have you any wool?

Jack Sprat would eat no fat. His wife would eat no lean.

All those nonsensical verses from your childhood really do matter. They matter, because they rhyme.

Why is rhyming important?

1. Rhyming teaches children how language works. It helps them notice and work with the sounds within words.

2. Rhymes help children experience the rhythm of language. As they recite nursery rhymes they learn to speak with animated voices. Someday they’ll read with expression, too.

3. When children are familiar with a nursery rhyme or rhyming book, they learn to anticipate the rhyming word. This prepares them to make predictions when they read, another important reading skill.

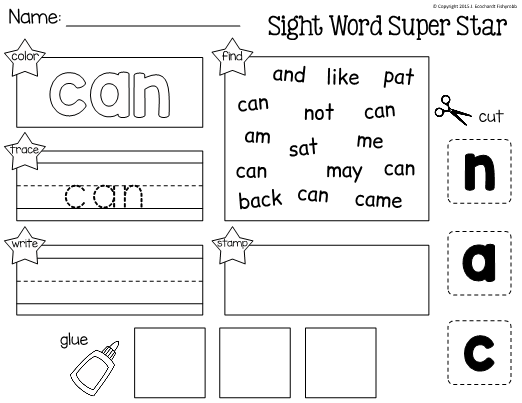

4. Rhyming is important for writing, too. It can help children understand that words that share common sounds often share common letters. For example, the rhyming words cat and bat both end with –at.

5. When listening to rhyming songs and poems children create a mental picture, expanding the imagination.

6. Because rhyming is fun, it adds joy to the sometimes daunting task of learning to read.

Also read: How to teach your child to rhyme

Members get more!

Members of The Measured Mom Plus get access to our one-click library of printables, with new printables added each month! Not a member yet? Learn more here.

CLICK HERE TO LEARN MORE

Teach rhyming with our nursery rhyme books!

25 Nursery rhyme books and posters

$6.00

This bundle contains 25 printable nursery rhyme books and posters – in both color and black and white! We love using these little books with new readers. They’re perfect for teaching concepts of print, building phonics and sight word knowledge, and building confidence.

They’re perfect for teaching concepts of print, building phonics and sight word knowledge, and building confidence.

Buy Now

Do you have our little letter books yet?

26 Letter Books of Nursery Rhymes & Songs

$7.00

Print a little book for every letter of the alphabet! Each book contains six nursery rhymes or songs. The books come in both color and black and white.

Buy Now

WATCH THE MEMBER TRAINING

In this 7-minute training, members will get quick tips for teaching this important foundational skill.

CLICK TO WATCH THE MEMBER WORKSHOP

Free Reading Printables for Pre-K-3rd Grade

Join our email list and get this sample pack of time-saving resources from our membership site! You'll get phonemic awareness, phonics, and reading comprehension resources ... all free!

Sharing is caring!

Filed Under: Reading, Pre-reading Tagged With: rhyming, preschool, kindergarten, Pre-K

You May Also Enjoy These Posts:

How to teach writing in kindergarten

The best book lists for early childhood

Reader Interactions

Trackbacks

The power of rhyme: why it is important to read poetry to children

Olesya Akhmedzhanova

“If the Christmas tree had legs, it would run along the path…”, suddenly remembered the lines of the poem that I learned in childhood with my mother. And although I am already an adult, this information does not go anywhere: the story about the Christmas tree is firmly planted in my head. So today we are talking about poetry. Why they are useful, how to read them correctly and which books to choose.

And although I am already an adult, this information does not go anywhere: the story about the Christmas tree is firmly planted in my head. So today we are talking about poetry. Why they are useful, how to read them correctly and which books to choose.

Why read poetry to a child

Poetry is one of the methods for developing a child's speech. They are built on sound combinations: “bee” rhymes with “tree”, “toy” with “cracker”, and “heart” with “ring”. Such a fun phonetic game with sounds gradually prepares the baby for reading and develops a sense of language. The child listens to the words and understands how one can combine one sound with another. And kids easily memorize verses, which means they develop memory and thinking.

I want to look out the window,

Go to sleep soon cat

Instead of me

Poems also help when studying letters. To fix any sounds, you can use rhymes: for example, when you pass the letter “sh”, tell us about the cat on the window, “h” about the titmouse and the fox, “e” about the piglet and the naughty child. Or come up with your own original examples.

Or come up with your own original examples.

How to read poetry

Start a tradition of reading poetry to your baby before bed. It is important to do this with expression: sigh loudly, be surprised, admire or laugh. Start with simple couplets and quatrains. Choose, for example, classic textbooks.

Skok-jump,

My horse,

Now a meadow, now a bridge.

Clay head,

Straw ponytail.

Poem and illustration from the book "Let's Read"

Then move on to more complex poems: with enumerations, interesting rhymes, or a funny plot.

He also ordered a pie

with centers inside,

Two full vases of jelly,

cream - three,

Four strudel

(say,

so as not to spare jam), , ,

curd puddings

five pieces

and six servings of cream

A poem and an illustration from the book "The Prince and the Svintus"

Poems + illustrations

Another childish (and we must admit, ours too) love: when there are poems in the book, "seasoned" with beautiful illustrations. They can describe the plot and show the characters.

They can describe the plot and show the characters.

... They danced

from morning to afternoon:

plié, relevé! batman, pirouette!

Poem and illustration from the book "Little Ballerinas"

Or be an independent work of art, which is successfully complemented by poetry. As, for example, in the amazing "Beautiful Book of Animals".

If we decide to become a flamingo for fun,

We need to get bright pink feathers:

We will be of a different color - we won’t find a match,

Not a single flamingo will build a better house nearby 9004 9002 ... this delicate color has been preserved,

We will have to get dinner right in the mud.

A poem and an illustration from the book "A beautiful book about animals"

In such books, you can look at pictures and melodiously accompany them with poetry reading. So you will introduce the child to the world of animals and, perhaps, learn with him the first verse about the mighty tiger, the pensive chameleon and the tender butterfly.

6 funny and beautiful poetry books

Every year we release bright and unusual poetry books. We choose the best: with high-quality illustrations, funny and melodic poems that you want to read, reread and learn by heart. They are perfect for introducing a child to rhymes.

A cute, funny poem about a boy who does not want to go to bed and offers his mother to put someone else to bed instead of him: a dog, a cat, a fish, a brother, a neighbor… Is this situation familiar to you? Of course, it's such a shame to go to bed when everyone is still awake, and there are so many interesting things going on around! This is a good book to read before bed. The kid recognizes himself in the hero, and perhaps, along with the book, there will be a way to go to bed with a good mood, and not a scandal.

A classic reader for the little ones: a collection of fairy tales most loved by kids, as well as poems, stories in pictures, the first cognitive information about the world around. All the main characters are animals, and the stories are based on how the baby's day goes. So he wakes up, and his beloved mother meets him, and at the very end of the book, he goes to sleep under a lulling poem.

All the main characters are animals, and the stories are based on how the baby's day goes. So he wakes up, and his beloved mother meets him, and at the very end of the book, he goes to sleep under a lulling poem.

The book is about a child's boundless fantasy, the ability to see the good in any situation, to believe, hope and be able to wait. She explains that you need to keep your promises, be patient and friendly, protect the weak, take care of your pets, and not betray your friends. The book contains bright, realistic illustrations and poems that are easy to remember. Read the story several times, and the child himself will be able to reproduce the text from memory by looking at the pictures.

This is one of our most beautiful animal books. It has green forests, yellow sands, sea depths and dense jungles. Instead of the usual text in the book, there are verses. They were written by the author of numerous children's books, the winner of literary awards and a zoologist by education, Nicola Davis. She studied whales, bats and even worked for the BBC's Wildlife channel. In 2017, the book won Best Science Book for Children and won the Royal Society's Young People's Book Prize, the Royal Society's science award that selects outstanding non-fiction books from around the world.

She studied whales, bats and even worked for the BBC's Wildlife channel. In 2017, the book won Best Science Book for Children and won the Royal Society's Young People's Book Prize, the Royal Society's science award that selects outstanding non-fiction books from around the world.

This charming tale of friendship, interaction, the challenges and joys of ballet will appeal to all dancers and audiences, regardless of age. The wonderful poems of Marina Boroditskaya are easy and fun to read. And dynamic and atmospheric illustrations are so nice to look at.

When funny characters, great poetry, and cool illustrations meet, great books like The Prince and the Svintus come together. English writer Peter Bentley came up with it while looking at his son Theo, "who eats everything he sees." Despite the fact that the verses seem simple, not only kids will enjoy, but also moms and dads, grandparents. This is an uplifting book for children ages 4 to 104 when you open it.

Post cover freepik

More about rhyme. An essay on the importance of rhyme and its role in poetry.

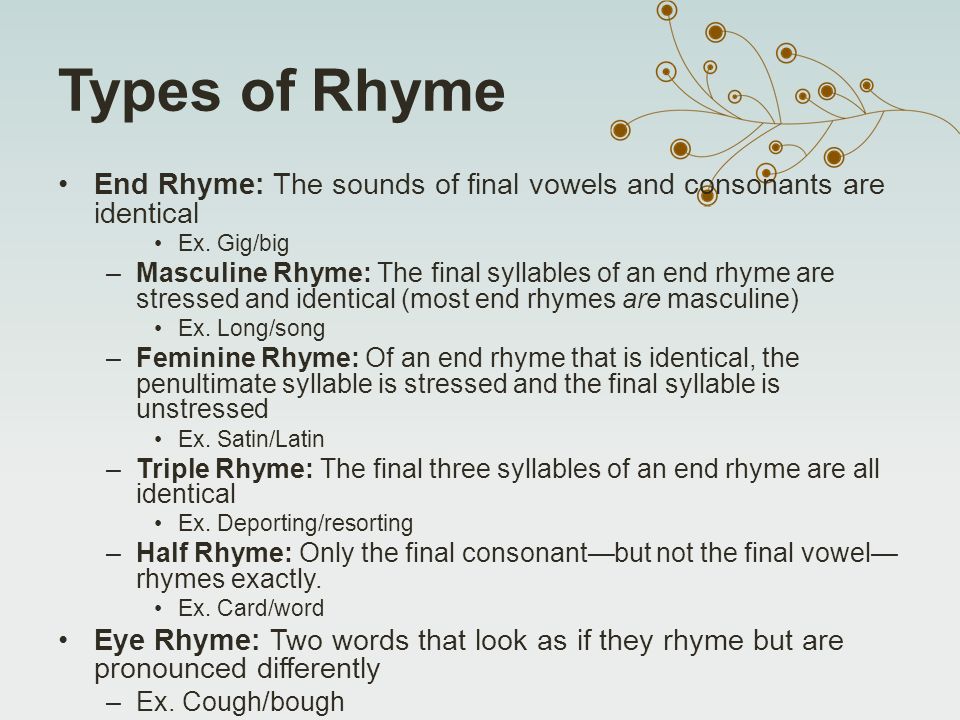

In the previous lesson on rhyme, we spoke strictly about its varieties. In the same lesson, which I will divide into two parts, I will publish two articles, or rather, even excerpts from textbooks on the versification technique of modern poets. The essays are very informative: they also mention the forms of poems, types of rhyme, the concepts of "bad" and "good" rhyme, the mention of verbal rhyme (is it as defective as modern critics used to think) and much more.

I hope the material will be of interest to you! :)

T. Bondarenko

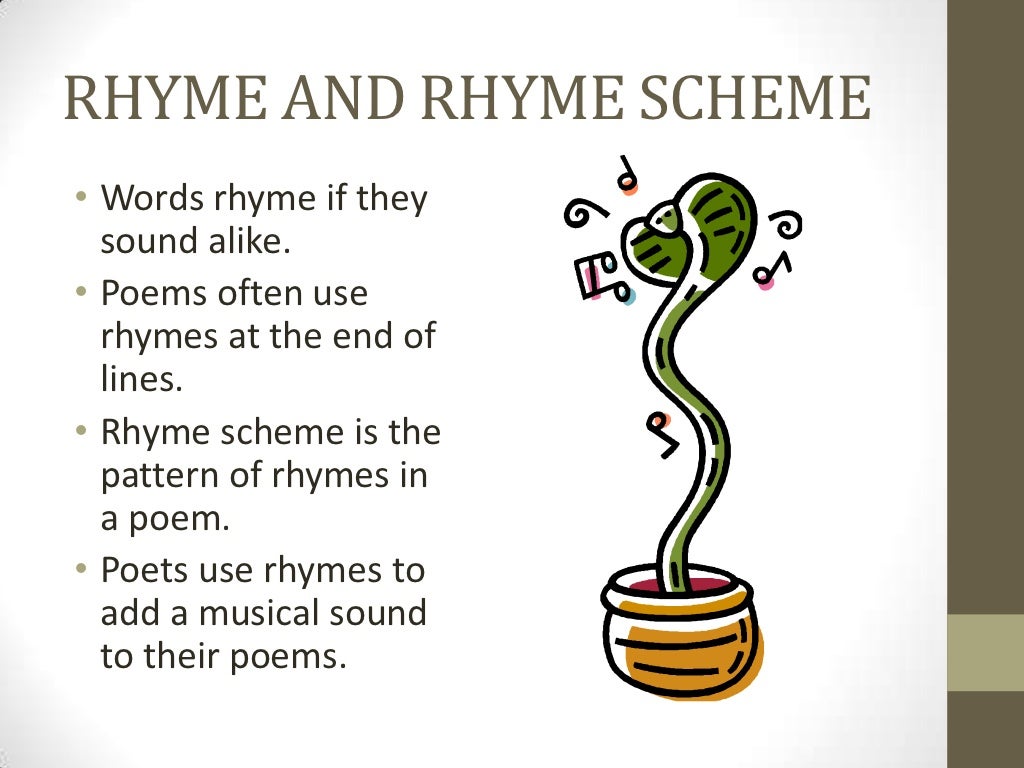

Rhyme

Let's start by stating a paradoxical fact. Very many people who write poetry cannot give a clear answer to the question - why, in fact, rhyme is needed in poetry. Silent about this and manuals for beginners. Even on a site dedicated to rhyme, Rifma. com.ru, I could not find an answer. Alas, even serious people are confused about this. So in the book "the theory of rhyme" by V. Onufriyev we find the following mumbling:

com.ru, I could not find an answer. Alas, even serious people are confused about this. So in the book "the theory of rhyme" by V. Onufriyev we find the following mumbling:

..."Rhyme is the consonance of the ends of poetic lines,

..."creating a sense of their unity and kinship;

... "one of the most striking and characteristic expressive means of poetry.

... "Mayakovsky noted its semantic meaning:

......" it brings you back to the previous line, makes all the lines, "

... "...forming one thought to stick together."

... "Speaking in an organizational capacity, rhyme accentuates

... "the ends of the verses, forms pauses after itself,

... "giving the opportunity to comprehend the lines and enjoy the euphony of the words...

Apart from the obvious stupidity that the rhyme "forms" pauses, everything else is indistinct mumbling. About creating kinship, unity, enjoying euphony, and the opportunity to comprehend...

And the answer is simple: rhyme is a RHYTHMIC element of verse. Again - his majesty the rhythm! Rhyme, of course, can carry another load, but the main thing that makes rhyme rhyme is the fulfillment of a rhythmic function.

Again - his majesty the rhythm! Rhyme, of course, can carry another load, but the main thing that makes rhyme rhyme is the fulfillment of a rhythmic function.

Let's explain on the example of

So let's say, a blank verse can be written

"Above the gray plain of the sea, the wind gathers clouds ...

or

"Over the gray plain of the sea

" The wind collects clouds

or

"Over the gray

" plain of the sea

"the wind of the clouds collects

, etc.

The line - the MOST IMPORTANT rhythmic unit of the verse - here turns out to be designed only purely typographically. The sound structure of the verse itself allows a very ambiguous breakdown into lines. In the absence of rhyme, the line structure of verses is blurred, the most important rhythmic component is sharply depleted.0163 Therefore, white verses, after the introduction of rhyme, forever found themselves on the sidelines of versification. And now, in almost 100% of cases, they are a surrogate produced by incompetent people. (blank verse is traditionally used in drama - but this is a slightly different area than just poetry - and I will not discuss this circumstance here).

(blank verse is traditionally used in drama - but this is a slightly different area than just poetry - and I will not discuss this circumstance here).

Once again we emphasize the main purpose of rhyme - the RHYTHMIC function. Everything else is OPTIONAL. Theoretically, rhyme can be located anywhere, but in Russian versification it is traditionally located at the ends of lines. Of course, rhyme does not create any pauses. Pauses create a rhythmic division into lines. (although not 100% required, lines without pauses after them are possible).

Well, let's take the previously analyzed example:

"Only sometimes it flashes on"

"A dolphin's back on a blue wave ..."

Here the pause is created by typographical division into lines, and not at all by rhyme. It is enough to write it differently:

"Only sometimes a dolphin's back flashes on a blue wave ..."

To see that it is the other way around here - rhyme is created by dividing into lines, and without it, rhyme disappears, and poetry in general. Another example from the so-called Paradise verse

Another example from the so-called Paradise verse

"The priest went to the market. To look at some goods"

Here one can clearly hear the rhyme "bazaar-goods". But it's not all about harmony. In construction

"Pop went to the bazaar to look at some product" or

"Pop went to the bazaar to look at some product"

the feeling of rhyme disappears. Although the sounds are the same.

This example clearly shows that consonance feels like rhyme precisely at the ends of phrases when it is used to reinforce the string (phrase) rhythm.

Of course, rhyme is NOT the ONLY rhythmic element of the line division of a poem. The division into lines is still based, first of all, on phrasal division - division into easily pronounceable, relatively complete in meaning and grammar, and rhythmically organized pieces. The rhyme is a SECONDARY though VERY POWERFUL means of string structure.

There are quite fancy classifications of rhymes. However, reading such works is of interest only for broadening one's horizons. And for practical purposes, it's almost completely useless. Therefore, we will focus only on what writers of poetry need to know.

And for practical purposes, it's almost completely useless. Therefore, we will focus only on what writers of poetry need to know.

Here is an excerpt from the "theory of rhymes"

... "If words are consonant with each other, then they say that they rhyme.

... "In fact, it is not words that rhyme, and not even sounds inside words

..." (let alone letters), but phonemes and their combinations.0004

If there are correct provisions, here again a methodological error: In fact, it is not sounds and not words that rhyme, but LINES. So in the above example, "on - the back" is perceived as a rhyme only with an artificial typographical division into two lines. And in itself, the consonance of individual sets of phonemes outside the framework of the lowercase rhythm is in no way a rhyme, even if it is clearly audible. In addition, in a sense, the letters rhyme. Statistics show that poets prefer to use rhymes that also coincide in spelling, and to a certain extent avoid using phonetically accurate, but literally different rhymes. However, this should rather be attributed to a certain tendency to read printed verses with the eyes.

However, this should rather be attributed to a certain tendency to read printed verses with the eyes.

So what is rhyme?

Rhyme is a rhythmic sound element that performs the function of amplifying and emphasizing the string (phrase) rhythm. In Russian versification, end rhyme is used - the consonance of the ends of the lines.

Why end? There is no convincing answer to this question yet. Personally, I think this is due to the fact that the beginning of the line is more clearly defined than the end. Earlier, when describing the intralinear rhythm, the fact was noted that lines with different beginnings are perceived as rhythmically different (iambic and trochee; dactyl, amphibrach and anapaest). While the difference in line endings does not create a sense of a different rhythm. Therefore, from the point of view of rhythm, it is more useful to rhythmically emphasize the weaker elements - the ends of the lines.

So, rhyme is the consonance of the endings of lines (more strictly, poetic phrases). The main rhyme-forming role is played by the coincidence of STOCKS. Although a rhyme is possible, built on the coincidence of only one shock sound /sea-boat, field-years/, combinations with a larger number of matching sounds are usually used.

The main rhyme-forming role is played by the coincidence of STOCKS. Although a rhyme is possible, built on the coincidence of only one shock sound /sea-boat, field-years/, combinations with a larger number of matching sounds are usually used.

Here it is necessary to pay attention to the confusion in terminology - assonance is called both a rhyme where only one stressed vowel matches and nothing more, and vice versa, a rhyme where a stressed vowel does not match, but a sufficient number of consonants and unstressed vowels / cloud - apple / . It seems to me that it is still more correct to call a rhyme where stressed vowels do not match - dissonance / as it is sometimes called /. And a rhyme where only one stressed vowel matches - assonance. However, the issues of terminology for practice are not so important.

The opinion is often expressed that dissonances are not rhymes at all. In the light of what has been said, it is clear that the answer to this question should be given on the basis of whether rhyme performs its main function - rhythmic - emphasizing the ends of lines. But such an answer cannot be given in the abstract. In one verse, dissonance may sound like a rhyme, but in another it does not. Here is an example of a verse built entirely on dissonances http://www.stihi.ru/poems/2003/09/10-1483.html Here the dissonant rhyme sounds quite satisfactory.

But such an answer cannot be given in the abstract. In one verse, dissonance may sound like a rhyme, but in another it does not. Here is an example of a verse built entirely on dissonances http://www.stihi.ru/poems/2003/09/10-1483.html Here the dissonant rhyme sounds quite satisfactory.

There is even an opinion that assonance - the coincidence of only one stressed vowel - is "not a rhyme". But this already comes from stupid aestheticism. And it can lead anywhere. Indeed, in poetry, such a rhyme often does not sound very good. But not in all cases. But in songs, assonance rhyme is a common thing. Which is quite understandable. When singing, only vowel sounds are sung, it is on them that the emphasis is placed / just do not mumble about the "vocalization of consonants" by Vysotsky /. In addition, in the song, the string rhythm is also emphasized by musical means, so the requirements for the "quality" of rhymes are lower there.

At first glance, it may seem that the ideal rhyme would be an exact repetition of "frost-frost", "mirror-mirror", or the classic "boot-shoes". /Such rhymes are called tautological/. If the theory of euphony and sound similarity were true, then it would be so. However, in reality, such rhymes create a very unpleasant impression!

/Such rhymes are called tautological/. If the theory of euphony and sound similarity were true, then it would be so. However, in reality, such rhymes create a very unpleasant impression!

So take the lines from Okudzhava's song (apparently experimental - everywhere except for the last two stanzas there are tautological rhymes):

[i]"She walked about the wire

"Waving her white hand

"And Morozov grabbed her passion

"With her calloused hand...[/i]

Here the hand-hand rhyme sounds so unpleasant that the people immediately changed it to

"waved her white leg"

The reason for this is that a pleasant rhythm for a person is not just a repetition, but a COMBINATION of repetition and DEVELOPMENT, MOVEMENT!

Or in other words - RHYTHMICALLY ORGANIZED FORWARD MOVEMENT. Marking time, running in circles - emotionally empty, and even disgusting. Exact repetitions in rhymes create a feeling of marking time, moving in a circle, chewing rubber. /in music, such things are called - bubblegum (bubble gum) / It should be borne in mind that starting from the line level, not only SOUND, but also MEANING becomes an important component. Words that sound the same but have different meanings are perceived differently. For example:

Words that sound the same but have different meanings are perceived differently. For example:

"And though we are almost strangers

"By visiting my house almost..."

or

"In the midnight cold delirium

"I am delirious over bumps in the marsh..." than hand-to-hand. And, accordingly, such a rhyme is usually regarded not as bad, but as cool. Moreover, even words that are formally grammatically cognate can rhyme normally if they are far enough away in meaning. Well, let's say "I'll forget it, I'll wake it up" Or, for example, from the classics:

"When I fell seriously ill...

"I couldn't think of a better idea...

"Verbal", and even one-root rhyme - by Pushkin! From a formalist point of view - terrible! But in real speech practice, the meaning of the word "sick" is far from "could not" and therefore, at the semantic level, they are not perceived as having the same root. And the specialist rightly regards this rhyme not as "terrible" but as "spectacular". But "boot - low shoes" - at all levels: both sound and grammatical and semantic is perceived as tautological. And such a rhyme will almost always sound "bad".

But "boot - low shoes" - at all levels: both sound and grammatical and semantic is perceived as tautological. And such a rhyme will almost always sound "bad".

We emphasize once again that the perception of rhyme depends on the meaning of the content of the verses. In particular, in meaningless verses, single-root rhymes such as "tomorrow-breakfast", and even those with different roots but very close in sound "burnt-tempered", sound much worse. The same can be said about poems that seem meaningful, but devoid of action, dynamics, when the content of the verse is marking time.

Somehow I had to listen to an author's song with very precise rhymes and a very static plot - the feeling that I was chewing a sole for several minutes - an obsessive impression that there was an endless repetition of the same thing (which, of course, was aggravated by the monotonous musical style of the bard song).

ABOUT "VERBAL" RHYMS

Special attention should be paid to the so-called "verbal" rhymes. A term widely used by semi-literate "experts". But not used by specialists. In fact, we should not be talking about "verbal", but about grammatical rhymes. For example, "fell-walked", "tortured-jumped", "flew-crouched", "killed-asked", etc.

A term widely used by semi-literate "experts". But not used by specialists. In fact, we should not be talking about "verbal", but about grammatical rhymes. For example, "fell-walked", "tortured-jumped", "flew-crouched", "killed-asked", etc.

Such rhymes really, usually don't sound very good. But the point here is not that they are "verbal", and not even that they are "easy" to invent. /according to statistics - the most words in the Russian language that rhyme in this way/. And the fact that grammatical endings of words rhyme here. "al-al" "el-el" "il-il" ...

That is, the famous "shoe-shoes" peeps through here. These are rhymes of a tautological kind - rhyming parts both in sound, grammar, and meaning - are one and the same.

However, they still do not sound as rude as "low shoes". This is due to the fact that grammatical endings are not so strongly isolated in the sense of the word as the roots of words.

Semantic perception focuses on the root - and the root is different here. "tortured" and "jumped" are different words and very far in meaning from each other, therefore the rhyming part "-al" is perceived not as a literal repetition as a low shoe. But in a brain-fucking verse, where the meaning is not involved, the same rhyme will sound worse.

"tortured" and "jumped" are different words and very far in meaning from each other, therefore the rhyming part "-al" is perceived not as a literal repetition as a low shoe. But in a brain-fucking verse, where the meaning is not involved, the same rhyme will sound worse.

The same can be said not only about the "verbal" rhyme, but about any other grammatical rhyme, for example desire-consciousness /any-any/. thieves-bad /noy-noy/ etc. Just due to the peculiarities of the Russian language, this happens much more often with verbs.

And "verbalism" itself has nothing to do with it. So "congratulated-put" - in all respects a full-fledged rhyme, because consonance is formed not only by the coincidence of the ending "silt", but the main rhyming element - the stressed vowel - is located in the roots of words.

As far back as Pushkin's time, attempts were made to "prohibit" "verbal" rhyme. There was even a poet who wrote an entire poem without using a single (!) "verbal" rhyme. The very fact that now his name is not known to anyone except specialists speaks for itself. But in Pushkin's "The Bronze Horseman", for example, 20% of rhymes are "verbal" ...

The very fact that now his name is not known to anyone except specialists speaks for itself. But in Pushkin's "The Bronze Horseman", for example, 20% of rhymes are "verbal" ...

In any case, of course, I agree that most of the hacky rhymes among beginners are "verbal" and that novice poets should avoid grammatical rhymes. And not only because they are bad, but also because they are too light. You need to learn to overcome the constant temptation - to do not "the right way", but "the way it is easier". And it's not just about verbs - I had to meet poems entirely built on grammatical rhymes, although not containing a single verb!

And again, I want to remind you that it is not sounds or words that rhyme, but lines. Even more than that - lines in a particular poem. As we have already seen, not only sound, but also meaning plays a role in the perception of rhyme. Therefore, there are no rhymes that are absolutely "bad" or absolutely "good".

Let's say, rhymes traditionally considered "classically" bad

"I-me" "you-myself" . ....

....

And here are examples:

"I once walked there too"

"But the north is harmful for me ...

"Sigh and think to yourself"

"When the devil takes you..."

You can of course, patting a classic on the shoulder, say "Well, Pushkin is forgivable..." Yes, of course, classics also have blunders and failures. But first you would need to check yourself - are you really well versed in the things that you undertake to judge? Does Pushkin need your "forgiveness"?

RHYME 2

ABOUT "GOOD" AND "BAD" RHYMS

....."Dirt is a substance in the wrong place"

.....saying of chemists

I would beat out this saying in golden letters. There is nothing "bad" or "good" in and of itself. Everything is good only in its place. Of course, there are "bad" rhymes - these are those that usually sound "bad", especially in the hands of beginner versifiers - they are almost 100% complete. It is advisable for beginners to avoid such rhymes. Until they develop good hearing and taste. There are rhymes that sound good most of the time. But it is not worth raising all this to an absolute.

There are rhymes that sound good most of the time. But it is not worth raising all this to an absolute.

First, poetry does not consist of rhymes alone.

----------

Rhyme is important, but not the only component. Even the sound in verse is far from being determined by rhyme alone. Unfortunately, such banal things have to be constantly reminded. Someone believes that poetry is rhyming, someone - that word-weaving, someone - that poetry is a heap of images, someone - that a riot of feelings, etc. They are all wrong, of course. All this is in poetry, in different proportions by different authors, but poetry does not come down to one thing.

Rhyme is a poet's tool. And it's stupid when a tool becomes an end in itself. Of course, the master must own the tool. But you don't have to be a virtuoso at all. And even if he knows how to masterfully rhyme, he should not bite out of the blue at all. There are no free cakes - and for exquisite rhymes, the poet often pays with a failure in other components of the verse. The author has the right to focus his attention on other components of the verse, albeit to the detriment of the quality of the rhyme. You can write quite worthy poems using hackneyed and gray rhymes. And you can write no poetry, although with "good" rhymes.

The author has the right to focus his attention on other components of the verse, albeit to the detriment of the quality of the rhyme. You can write quite worthy poems using hackneyed and gray rhymes. And you can write no poetry, although with "good" rhymes.

The best carpenter is not the one with the most expensive and ingenious planers. And not the one who knows how to juggle chisels. Undoubtedly, it is interesting to look at a carpenter who knows how to juggle with axes, but such wretches have a very distant relation to carpentry. And it says nothing about the quality of the products of such a carpenter.

Secondly, rhyme, being far from the only element of verse, must be in harmony with the rest. So, a rumbling rhyme is quite appropriate for poster poems, but will be out of place in an elegy or philosophical reflection. A bright rhyme - but only in one pair of lines, against the background of the rest of the gray rhyme will "stick out", unless such a selection is justified by the content of the verse. Better evenly "bad" rhymes than such a non-builder. Well, like a piece of parquet among the asphalt site - it looks just stupid. Somehow I had to make a similar remark to the author, but, alas, he did not want to understand it at point-blank range ... The use of obviously "bad" rhymes can be a completely conscious device. See for example the verse http://www.stihi.ru/poems/2001/07/07-29.html where the author specifically selected the worst rhymes. Moreover, even the absence of rhyme can be used as an expressive means: http://www.stihi.ru/poems/2002/07/13-171.html

Better evenly "bad" rhymes than such a non-builder. Well, like a piece of parquet among the asphalt site - it looks just stupid. Somehow I had to make a similar remark to the author, but, alas, he did not want to understand it at point-blank range ... The use of obviously "bad" rhymes can be a completely conscious device. See for example the verse http://www.stihi.ru/poems/2001/07/07-29.html where the author specifically selected the worst rhymes. Moreover, even the absence of rhyme can be used as an expressive means: http://www.stihi.ru/poems/2002/07/13-171.html

Of course, without special justification, the quality of rhyme should not fall below the level of city sewerage. But this should be attributed to ANY OTHER component of poetry.

Reaching the top in everything at once is the lot of geniuses, and even then, only in individual masterpieces. And to demand this, even from a genius, in every verse is simply stupid. Especially from mere mortals. By the way, they called the king of Russian rhyme - you know who? And in my opinion, not without reason. *) And the fact that he remained little known to the general public - only proves the thesis that rhyming is not yet poetry.

*) And the fact that he remained little known to the general public - only proves the thesis that rhyming is not yet poetry.

Let's take, for example, a series of rhymes by one author, written out in a row.

myself-you, I-me, scolded-driven, decided-sweet, lady-epigram,

days-his, could-pledge, steppe-his, sometimes-tear,

alone-silence, myself-wife, breguet-lunch ,

alive-gold, that-his, backstage-rushed

yawn-remember, develop-beats, endured-tired,

won-he, office-years,

right-wrong .....

Esthete right there of course exclaim - what a monstrous graphomania! But this is Pushkin. The rhymes are written in a row. But not in a row along the lines, but the last rhymes in each Onegin stanza are taken. One can, of course, breed demagoguery about the "progress" of poetry since the time of Pushkin. (It will be demagogy, because even then such rhyming was considered weak). And you can get rid of the ideas about the inherent value of rhymes in themselves. And try to understand why exactly at the ENDS of stanzas Pushkin preferred to put weak rhymes. And if you think about it and analyze the sound, then the answer is easily found. Strong rhyme would, roughly speaking, give the impression of an exclamation mark at the end. And weak - creates the effect of ellipsis. So that it turns out a soft ending and no immediate continuation is expected. A pause is created to move on to the next stanza. This effect is further enhanced by the adjacent rhyming of the last couple of lines. As if the light is dimmed before dimming and moving on to the next fragment of the video sequence. Check - clearly place the ellipsis at the end of each Onegin stanza - and make sure that he will be completely in his place there. But typographically it would not be very nice. As I have said before, a good poet should avoid using punctuation other than easily guessed. And here Pushkin skillfully creates the desired effect by purely poetic means, without resorting to typographical ones.

And try to understand why exactly at the ENDS of stanzas Pushkin preferred to put weak rhymes. And if you think about it and analyze the sound, then the answer is easily found. Strong rhyme would, roughly speaking, give the impression of an exclamation mark at the end. And weak - creates the effect of ellipsis. So that it turns out a soft ending and no immediate continuation is expected. A pause is created to move on to the next stanza. This effect is further enhanced by the adjacent rhyming of the last couple of lines. As if the light is dimmed before dimming and moving on to the next fragment of the video sequence. Check - clearly place the ellipsis at the end of each Onegin stanza - and make sure that he will be completely in his place there. But typographically it would not be very nice. As I have said before, a good poet should avoid using punctuation other than easily guessed. And here Pushkin skillfully creates the desired effect by purely poetic means, without resorting to typographical ones.

----------------

*) D.D.Minaev

RHYME 3

EXTENDED RHYTHM

Let us now return to the thesis that it is not words or sounds that rhyme, but LINES. This means that proper rhyme need not be restricted to a final stressed vowel with adjacent consonants. Let's reconsider Pushkin's previously cited lines:

"When I fell seriously ill"

"And I couldn't think of anything better"

The consonance connecting these lines does not really boil down to "I fell ill - I couldn't" For clarity, we cut the lines like this

"... fell ill

".. could not

here you can immediately see the coincidence of the vowel "a"

"... sick

".. Could not

but this is not the end of the matter!

"..kU fell ill

"..could not think

Thus, the real consonance of the lines turns out to be much richer than the formal one fell ill, could not! Or let's take, for example, what some were going to generously forgive Pushkin: "I-me"

"There once walked and I

"But the north is harmful for me . ..

..

Cut off for clarity:

"...lyal and I

"...for me

Considering that the letter E in the word "me" is pronounced the same as "and" in the first line, then the consonance is

"...LYAL AND I

" ... FOR ME

is much richer than the formal me-me. But that's not all - in these lines the stressed vowel on the second syllable

"There once walked AND I

" But the north is harmful for me ...

i.e. there is also an assonant "internal rhyme". Let's take Pushkin's "yourself-you", highlighting the consonances (taking into account that in oral pronunciation I-E A-O in the unstressed position

sound similar):

"SIGHING AND THINKING TO YOURSELF

"WHEN THE FUCK IS FROM YOU" , and not necessarily in a row. I would call this phenomenon extended rhyme (extended rhyme), leaving the established term "rhyme" only for the final consonance formed around one stressed vowel. Extended rhyme is not such a rare occurrence. In the case when additional, non-terminal, consonances are sufficiently "rich", it is customary to speak of an "internal" rhyme

For example:

"The main cannon was no longer bored

"A glorious song sounded on the brig . .."

.."

Here, in addition to the end complex "did not miss - ..he sounded" there is a rhyme at the beginning of the line "the main-glorious"

It should be noted that sometimes "internal rhyme" is called alliteration - a sound echo that does not perform a rhythmic line-selecting function. In my opinion, it is better to call it simply alliteration, so as not to be confused with rhyme elements. does not apply. Personally, I would leave the term "internal rhyme" only for cases when this consonance is in the same place within the line, and is regularly carried out throughout the entire verse, i.e. when internal consonance is a constant element of rhythm.0163 Extended rhyming greatly enriches the possibilities of the poet. You can use even the "weakest" end rhymes, supplementing them with the consonance of other parts of the lines, and as a result, get a completely decent sounding of poetry.

And they gathered to forgive Pushkin because they approached formally, having read the lines with their eyes and not having tried the sound. Once again I have to remind you: poetry is a sound speech. Even if there are no analytical abilities, the ears are in place. You can just make sure that the sound is normal, despite the formally "bad" rhyme.

Once again I have to remind you: poetry is a sound speech. Even if there are no analytical abilities, the ears are in place. You can just make sure that the sound is normal, despite the formally "bad" rhyme.

CONCLUSION OF THE CONVERSATION ABOUT RHYME

Here I will make a digression - on the website of the stichera I constantly encounter the "deafness" of the public - the sloppy habit of reading poetry with their eyes (and even casually diagonally). Even "bulging" internal rhymes manage not to notice, paying attention only to the ends of the lines, and even then, often without even trying to sound. However, many authors, apparently, read their own poems only with their eyes, not noticing sound flaws, or even gross mistakes. But they like to play in typographic druk ... Once again I will underline the verses - the speech is sounding. And if the sound is indifferent or inaccessible to you, leave poetry alone. And if not, then at least try to develop this very hearing, and not build your deafness into an absolute truth. When I say quit poetry, I don't mean quit writing. In the end - let people have fun if it pleases them. But you don't have to imagine yourself a "poet" and have some serious hopes and claims. And even more so to pass off your exercises as peaks.

When I say quit poetry, I don't mean quit writing. In the end - let people have fun if it pleases them. But you don't have to imagine yourself a "poet" and have some serious hopes and claims. And even more so to pass off your exercises as peaks.

And once again - the lines rhyme not "in general" but specific lines in a particular poem. In addition to purely sound means of highlighting similar lines, rhythmic parallelism can be used, both at an obvious level (alternance) and at a less obvious level (location of caesura, word divisions, location of pyrrhias and spondees). In addition, elements of GRAMMATIC and SENSITIVE symmetry can be used.

Apparently, all this should not be attributed to the elements of the actual rhyme, although these things can perform the same function and can significantly enhance the rhyme. Conversely, flaws in all of these elements can weaken and make even seemingly "normal" rhymes sound bad. (in reality, of course, it is not the sound that changes, but the feeling of the rhythm).

And to everything that has been said, one can also add a stylistic component. In one verse, "cool" rhymes will be appropriate, in another - they will look like outright chicanery and mannerisms. Even in verse, where in principle both are acceptable, it is not always appropriate to mix styles of rhyme - often a verse in a single style sounds better. What will sound better - a stylistically very smoothly constructed line with a "weak" rhyme or a line with a "strong" rhyme, but stylistically rougher? "Weak" rhyme, in a line that sounds like a piece of natural, without the slightest violence, speech of the hero - or "strong" rhyme, but with obvious signs of artificial construction?

And finally, if the current level of poetic technique does not allow - then what should be preferred - a verse with a crooked content and correct rhyme - or a verse with well-built other components and clumsy rhyme? Of course, to each his own, but personally, in many cases I prefer to sacrifice (up to a certain limit, of course) the quality of rhyming. The main thing is that the adoption of such a decision should be conscious, and not come from deafness or a disregard for the rules of versification. A footballer has the right to deliberately kick the ball for a corner or out of bounds, but only after assessing the situation, and not out of negligence or inability to handle the ball, and even more so not because he believes that the rules are not written for him.

The main thing is that the adoption of such a decision should be conscious, and not come from deafness or a disregard for the rules of versification. A footballer has the right to deliberately kick the ball for a corner or out of bounds, but only after assessing the situation, and not out of negligence or inability to handle the ball, and even more so not because he believes that the rules are not written for him.

So, summing up the discussion of rhyme, we see that rhyme does not come down simply to the consonance of the ends of lines, or lines in general. The perception ("sound") of rhyme is influenced by many other components of the verse - rhythmic, grammatical, semantic, stylistic. And in the end, not a rhyme, not a line, but a verse as a whole should sound. And sound is not the only component of poetry. Although, of course, there are rhymes, usually bad-sounding, which are not recommended for beginners, it is not worth elevating this or that rule to the absolute. Particular attention should be paid to the "verbal" rhymes. More precisely, on any grammatical. It is not recommended for beginners to use them, because. such rhymes are hard to make sound "good". Besides, they are too easy to find, and laziness was born before us. The habit of giving yourself indulgence is hardly useful for cultivation. Of course, you can use bad rhymes as a kind of surrogate in a situation where the technique does not allow you to achieve better. In the end, people want not just to study, but to get some, albeit modest, results. But it is important to understand that you are playing by easy rules. And when learning, do not lose your head and imagine the real level at which you are.

More precisely, on any grammatical. It is not recommended for beginners to use them, because. such rhymes are hard to make sound "good". Besides, they are too easy to find, and laziness was born before us. The habit of giving yourself indulgence is hardly useful for cultivation. Of course, you can use bad rhymes as a kind of surrogate in a situation where the technique does not allow you to achieve better. In the end, people want not just to study, but to get some, albeit modest, results. But it is important to understand that you are playing by easy rules. And when learning, do not lose your head and imagine the real level at which you are.

And I want to pay attention to one more thing - I repeat, poetry consists not only of rhymes. Poems are made up of more than just the ends of lines.

Hard work on the ability to rhyme is, of course, necessary, but teaching versification should in no way be reduced ONLY to this. Nothing else can be overlooked. And, having mastered rhyming, one should not assume that he has already comprehended everything in poetic technique.

This is just one of many components. (rhythm, strophic, sound, composition, figurativeness, style, content, etc.) I met many poems in which the author is proud of the non-banality of rhymes, but swims in rhythm and strophic, and allows a bunch of clumsy inversions and transfers, sound and semantic flaws , stylistic carelessness, blunders in content .... To a large extent, the bias in rhyme is facilitated by the remarks of semi-literate reviewers who do not know how to do anything else, how to find fault with "verbal" (sometimes "hackneyed") rhymes. As a result, the author has the impression that it is enough to start rhyming in an original and non-verbal way - and you are already in the poets. At the same time, strange monsters arise - arbitrarily crooked rhymes - if only they are not "verbal" and not "hackneyed". And the author, in response to a remark about the quality of rhymes, proudly declares that "on the other hand" they are not beaten ... Who cares, but for me the rhyme love-blood is better than love-locomotive.