Www learn to read com

Learn Reading

Scroll

A Multisensory Reading Program for Struggling, Dyslexic or Emerging Readers

THE LEARN READING LESSONS

The research-based, multisensory reading curriculum for struggling, dyslexic and emerging readers.

Want To Join My Adult Reading Class?

Click the button below to learn more!

Learn Reading is an Orton Gillingham and research based, multisensory, direct, explicit and comprehensive reading program.

Learn Reading has helped thousands of THE MOST STRUGGLING readers.

It can help yours too.Your student will be taught the

“Pencil Reading” blending technique to help them blend to the end.Your student will be taught the

“Vowel Placement Strategy” to help them know WHAT each vowel will say and WHEN.Your student will be taught using the

“Give a Goal” technique so they will learn how to read, NOT how to guess.

Chira Speers

“I love this course so much! My second grader has always struggled with reading...she spends most of her time decoding and trying to say the right word. This Learn Reading program has been amazing! She can break down the words and sound them out. She's reading new words that are fun and silly. This program forces her to slow down and think about each letter and word. Plus, it's fun to play the games together! Thank you so much for creating such an amazing program and sharing it!”

Daleea Barrett

“Over the moon excited about your program! The Tutor Training Guide is excellent. Not only does it walk you through step by step, it breaks it down and explains why you do this, and the importance of it....From what I have seen so far, the concept as a whole is brilliant!" step by step, it breaks it down and explains why you do this, and the importance of it....The concept as a whole is brilliant!”

Not only does it walk you through step by step, it breaks it down and explains why you do this, and the importance of it....From what I have seen so far, the concept as a whole is brilliant!" step by step, it breaks it down and explains why you do this, and the importance of it....The concept as a whole is brilliant!”

Amy Badger

“I have been using the Learn Reading course with my 5 year old preschooler and my 3rd grader. Both of them have been enjoying the well thought out activities and simple to follow methods for learning to read. It has been so rewarding to see how quickly the concepts make sense to everyone and confidence grows exponentially through the process. I have been so grateful to have round such a well thought out course that makes such a challenging task like learning to read doable and enjoyable for all of us!”

THE LEARN READING PROGRAM

$5/LESSON

The ONLY multisensory, research-based reading program that teaches “pencil reading”, the “give a goal” method and the “vowel placement strategy”, all proven to eliminate guessing in even the most struggling readers.

Includes:

Quick Training Guide

Video Tutorials

All Materials Needed

Downloadable, printable lessons

Free, unlimited support from April McMurtrey

THE LEARN READING LIBRARY

$6/MO

Receive ALL the training and tutorial videos in one place, AND the entire Learn Reading document cache. EVERY video and document (exluding the Learn Reading lessons) from EVERY course is included.

Includes:

Over 300 tutorial videos

Entire Learn Reading document cache

All 8 supplemental readers

Spelling words for every Learn Reading lesson

THE AT-HOME DYSLEXIA SCREENING

$89/SCREENING + REPORT

Receive a comprehensive, at-home dyslexia screening for students ages 6-106. You will finally know IF your student fits the dyslexia profile AND what to do next if they do.

You will finally know IF your student fits the dyslexia profile AND what to do next if they do.

Includes:

Quick video guides for both screener and student

11 different screening tests

A comprehensive, personalized report detailing the results and recommended next steps.

HOW TO TEACH READING

$77

Designed for parents to know how to best help their children with reading at home. In-depth instruction on the 5 essentials to teach reading effectively and what techniques to AVOID.

Includes:

Tutorial Videos that will teach you EXACTLY how to teach reading

All materials necessary to begin teaching immediately

A FREE gift of the FIRST 5 LESSONS in the Learn Reading Program!

TEACHING TIPS for PARENTS

$77

April’s favorite course! This course is packed FULL of teaching ideas which include specific techniques for those dealing with dyslexia and/or adhd. A must have for homeschool parents and tutors.

A must have for homeschool parents and tutors.

Includes:

Specific ways to teach students with dyslexia and/or adhd

Techniques for handling frustration, confusion or fear.

A FREE GIFT of the Teaching Tips e-book!

READING INTENSIVE WORKSHOP

FREE for Adult Nonreaders

This 2-week course is for ADULT NON-READERS ONLY. If you can read this description, then this course will be too easy for you and you should begin with Lesson 1 of the Learn Reading program (above).

Includes:

PRESCHOOL PACKET

$18

A 5-week course designed for children ages 3-6. The first 5 most common graphemes/phonemes are taught to prepare them for lesson 1 in the Learn Reading program. Plus recommended games and activities!

Plus recommended games and activities!

Includes:

Daily lessons for 5 weeks of focused teaching.

Training guide and videos

All materials necessary

Recommended activities for continued practice.

LEARN READING WORKBOOKS

$88/EA

These physical workbooks are an ALTERNATE CHOICE for those who prefer not to print each lesson in the Learn Reading program. They include the exact same lessons, training and coursework as in the online course.

Includes:

LEARN READING GAME CARDS

$34-42

Professional, boxed game card sets for every lesson in the Learn Reading Program. Each box contains PAIRED word cards (including WILD cards) for extra practice in each lesson. A must for tutors!

A must for tutors!

Includes:

Paired word cards for every lesson in the Learn Reading program.

Several WILD cards per box for games like “Slap it” or “Memory”.

Hours of fun learning to read!

Learn more

Includes:

Lesson 1

80 True Sight Words

Sight Word Games and Activities

Phonemic Awareness Exercises

Correct Sounds Audio Clip

Correct Sounds PDF

5 Essential Requirements to Teach Reading Effectively

Dyslexia Pre-screening

Reading Level Assessment - COMING SOON

All testimonials for Learn Reading are given on a volunteer basis. None have been paid or received any compensation. They are all simply happy parents.

None have been paid or received any compensation. They are all simply happy parents.

Learn Reading is the breakthrough program that helps even the MOST STRUGGLING students.

Authority Magazine

Thrive Global

Dystinct Magazine

Learn Reading Library

Library

$6/mo subscription

(Introductory offer. Normally $11/mo)

Yes! I Want the Library!

YOU WILL RECEIVE:

OVER 300 VIDEOS!

- ALL training videos for the Learn Reading program

- ALL videos in the "How to Teach Reading" course

- ALL videos in the "Teaching Tips for Parents and Teachers" course

- ALL Teaching Tips Videos for Students with Dyslexia and/or ADHD

- The COMPLETE Reading Intensive Workshop Course!

- ALL Supplemental Readers for ALL Learn Reading Lessons!

- Approved Spelling Words for Every Learn Reading Lesson!

- ALL videos in the "Dyslexia Screening Kit"!

- ALL Learn Reading YouTube videos (continuously updated)

- ALL Live Lesson Videos!

- ALL Learn Reading TikTok videos (continuously updated)

- ALL Correct Sounds Audio Clips

- ALL Learn Reading Full Length Webinars

- ALL Learn Reading Case Studies

PLUS!. ..

..

- Learn Reading Tutor Training Guide

- Word Games and Activities

- 80 True Sight Words List

- Phonemic Awareness Exercises

- Correct Sounds of the Alphabet

- Vowel Placement Charts

- Sight Words Game Graphic

NOTE: The document library does NOT include the Learn Reading lessons. You may access the Learn Reading lessons here: Learn Reading Lessons - Level 1.

PLUS!...

- Included in the Library Due to Popular Demand!

- ALL 8 Supplemental Readers for ALL the Learn Reading lessons!

- 5 Short Stories PER Lesson!

- Controlled Text to Eliminate Guessing!

- Extra Reading Practice After Every Lesson!

- Printable PDFs For Your Reader to Enjoy!

- Written Specifically for Each Lesson in the Learn Reading Program.

PLUS!...

- Included in the Library Due to Popular Demand!

- A List of Approved Spelling Words for Every Learn Reading Lesson!

- ONLY Contains Words That the Reader Has Learned HOW To Read and Spell.

- Controlled Text to Eliminate Guessing!

- Extra Spelling Practice After Every Lesson!

- Written Specifically for Each Lesson in the Learn Reading Program.

- Finally, Enjoy Anxiety-Free Spelling Tests!

PLUS!...

- 95 pages of April's favorite teaching tips!

- Rule #1 when it comes to teaching!

- How to teach kids with dyslexia!

- How to teach kids with ADHD!

- How to keep learning positive!

- How to make learning fun!

- How to encourage the sad, discouraged, or fearful student.

- How to keep going, when YOU are discouraged!

Discover April's collection of FAVORITE tips that she has used over her 30+ years of teaching!

This 95-page ebook is yours free with your subscription!

Yes! Enroll me in the Library for $6/mo

“This library has all of the content that I could possibly hope for! It is also very helpful that there is continuing content being updated regularly. It's a one stop shop!!”

It's a one stop shop!!”

HANNAH SEANEY

What You'll Get With Your Subscription:

With Continual Updates!

- Get!...THE COMPLETE LEARN READING VIDEOS VAULT!

- Plus!...THE LEARN READNG DOCUMENT VAULT!

- Plus!... CONTINUOUS UPDATES WITH CONTINUOUS ADDITIONS!

- Plus!....ALL 8 FULL SUPPLEMENTAL READERS!

- Plus!....APPROVED SPELLING WORDS FOR EVERY LESSON!

- Plus!...THE TEACHING TIPS FOR PARENTS AND TUTORS EBOOK!

Stay on top of April's continuous teaching tips, live examples, challenges, news, and more!

You'll never miss a thing!

WHO IS APRIL MCMURTREY?

- Certified Teacher

- Certified Reading Specialist

- Certified Dyslexia Therapist/Tester

- Certified Irlen Syndrome Screener

- Professional Educator/Presenter

- Teacher Trainer

- 30+ Years Teaching Reading

- Developer of the Learn Reading Curriculum

Enroll Me Now →

WANT THE LEARN READING LESSONS?

Learn Reading is an Orton-Gillingham and research based, multisensory, direct and explicit reading program.

It is designed for earners of ALL ages and levels, but caters specifically to

struggling, dyslexic, and emerging readers.

FOR ACCESS TO THE LEARN READING LESSONS

CLICK HERE.

I Want Access to the Library! →

30-DAY MONEY BACK GUARANTEE!

YOU MAY CANCEL AT ANY TIME.

(Access to the library will be discontinued upon cancellation.)

©2020 Conceptual Company. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy | Created with Leadpages

Read online “How to learn to learn. Skills of conscious assimilation of knowledge ”, Ulrich Boser - Litres

Translator M. Kulnev

editors A. Nikitin, A. Zhuravel

Zhuravel

Editor S. Turko

Head of Project A. Derkach

Proofreaders E. Aksenova, M. Smirnova

Computer proofreading A. Abramov

Cover design D. Izotov

© 2017 by Ulrich Boser

© Russian edition, translation, layout. Alpina Publisher LLC, 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is intended solely for private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes. The e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, including text, images and others, may not be copied or used in any other way without the permission of the copyright holder. In particular, such use is prohibited, as a result of which an electronic book, its part, fragment or element becomes available to a limited or indefinite circle of persons, including via the Internet, regardless of whether access is provided for a fee or free of charge.

Copying, reproduction and other use of an e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, beyond private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes, without the consent of the copyright holder is illegal and entails criminal, administrative and civil liability.

* * *

To my parents who ignited my love of learning

From the author

In writing this book, I have used texts that have previously appeared in the form of articles, reports, or blog posts. For clarity, I have edited the quotes and shared some of the text with sources to get feedback on them. If, speaking about someone, I call him only by his name, it means that it has been changed. If there are errors in the facts and quotations, or something in the text is not clear enough, I will try to correct it on my website www.ulrichboser.com.

As for quotations, I found it inconvenient to use footnotes at the bottom of the page in e-books, so I moved the notes to a separate section that provides sources of materials, some comments on them and additional literature. As for the conflict of interest, I have it - and who doesn't? I did work for various organizations and foundations mentioned in the book. You will also read about this in the notes section.

When I wrote about the events of my own life, especially those that happened a long time ago, I really wanted to end each sentence with the words "as far as I remember." Keep that in mind!

Foreword

Tucked away in a suburban cul-de-sac about ten miles north of New York City is a squat brick elementary school surrounded by sturdy farmhouses and time-tarnished colonial buildings. It was a cold morning on January 6, 1986, with the temperature barely above freezing. Parents taxied to the school building. Children jumped out of the cars, laughing and chatting. Occasionally, piercing screams were heard.

At about half past eleven in the morning, a green-eyed boy with a messy mop of blond hair sat down on a chair in one of the classrooms. He would be eleven a few days later and was almost certainly wearing a turtleneck sweater and corduroy pants. On the pages of notebooks crammed into his satchel, notes from school assignments were side by side, most likely with drawings inspired by the Dungeons and Dragons game.

The green-eyed boy was having trouble with his studies, and this morning was no exception. At the beginning of the lesson, it was about the rules for subtracting fractions, and the boy was called to the blackboard to write the solution to a homework problem. But he wrote the equation wrong, so the problem had to be redone.

Soon the boy became distracted, began to turn and fidget in his chair, like a beginner Houdini trying to get out of a trap, and the teacher remarked to him: “Concentrate, please!” Other students answered questions and solved problems. But the green-eyed boy did not understand anything. Therefore, he did not try to solve the problems on his own, but without thinking twice, he copied the answers from a neighbor.

Twenty minutes later, the teacher called him again and asked him a division example: “What is 770 divided by 77?” The boy did not know the answer. Another example is another embarrassed grimace. But the lesson has come to an end. While the teacher was explaining homework, the green-eyed boy was chatting with a friend about sports, books, holidays, God knows what else. Before everyone left the classroom, the teacher made another remark to him.

Before everyone left the classroom, the teacher made another remark to him.

In a certain sense, each of us is such a green-eyed boy. Too many kids do their homework with mistakes - it's so easy to get distracted! But that kid was me. At school, I was always behind. My grades were worse than ever. I swam in my exams. The teachers complained to my parents, called me unteachable, someone even told my mother that I should probably become a cook. And then one morning, on January 1986 years old, the school psychologist came to the office where our fourth grade was studying to watch me in the lesson.

When I try to remember this day, not a single detail comes to mind. But for many years I kept a detailed report of the psychologist - a black-and-white document, typewritten at one interval. It described how I managed to deceive the teacher, how neglected I was at work, and how I was completely unable to concentrate throughout the lesson. “Disinterested”, “inattentive”, “distracted” - such epithets, among others, were awarded to me by a psychologist.

My difficulties probably started in kindergarten. I was the youngest there and ended up staying for my second year because I couldn't cope with the program at all. In elementary school, teachers sent me for a special examination, and I diligently filled in the circles in a whole bunch of long tests with unpronounceable names - Bender's visuo-motor gestalt test, Zeitlin's study of adaptation mechanisms, projective drawing test ... In high school I spent several hours a week in a special education group, where they drove all the freaks and losers who did not fit into society and could not cope with the program.

The adults came up with more and more theories and possible explanations for my difficulties. Some thought that I was so bad at studying because my immigrant parents spoke German at home. Others claimed that I had problems with hearing: the connections in the brain responsible for the perception of information by ear were formed incorrectly. Still others were convinced that I lacked intelligence - that almost magical ability to think and solve problems.

There was some truth in each of these theories. My parents had lived in the country for more than a dozen years and spoke English, but at times they still switched to German in conversation. I did have problems listening to information - I still find it difficult to follow verbal instructions. And to be honest, I'm not a genius.

But there is another point of view on everything that happened then. Now, when I look back, it seems to me that I simply did not know how to study. I didn't think about how to think right. I did not ask myself questions, did not set goals, and, in general, did not even understand what it was like to know something. The ability to learn was beyond my understanding, and in the end I was "lost", as the psychologist wrote in his report.

Still, there were a few teachers who helped me master some basic learning strategies. I started asking myself different questions, like, “Do I really know something? Do I understand the logic of what I am being taught?” Also, I finally realized that everyone has a different pace of learning and that I might just have to put in a little more effort than my peers. In later years, I figured out how to be more focused and became a fan of all things quiet—I still buy whole boxes of earplugs to this day.

In later years, I figured out how to be more focused and became a fan of all things quiet—I still buy whole boxes of earplugs to this day.

Gradually I became more confident in my abilities and my grades began to improve. I was interested in school self-government. And sports - running, basketball, off-road cycling. I did well on my entrance exams, and with a bit of luck and a lot of work, I was accepted into Ivy League College [1] !

I did not base this book on my own academic experience. In fact, if you compare it to the experience of those who are stuck in end-of-the-world colleges or goofy corporate training programs, I was lucky: I had understanding parents, a good school, and generally attentive teachers. Yes, and my problems with auditory perception can not be called typical.

But in the end it was my experience that sparked my interest, and that interest was the start of my career. And today it seems to me that many people are similar to me in childhood: they simply do not think about how best to acquire new knowledge and skills. For example, they re-read the material many times, although this is far from the best way to learn it, or color fragments of the text with markers, despite the fact that the effectiveness of this action is also poorly supported by research. At the same time, they do not analyze their abilities and do not track their progress, although there is much evidence in favor of such methods.

For example, they re-read the material many times, although this is far from the best way to learn it, or color fragments of the text with markers, despite the fact that the effectiveness of this action is also poorly supported by research. At the same time, they do not analyze their abilities and do not track their progress, although there is much evidence in favor of such methods.

This situation continues despite the fact that most of us are constantly developing our skills and knowledge. Have you been offered a new computer program? Will have to master it. (Be sure to explain the key ideas to yourself so you can really understand them.) Found a new client? You need to present your ideas to him in such a way that they seem attractive to him. (When preparing a presentation, don't put too many graphs on one slide; this overloads short-term memory.) Want to remember a phone number? (Use your fingers; this is a great way to keep numbers in memory for a short time.)

Not long ago I went out for coffee and met one of my former special education teachers. We sat at Starbucks and shared memories. At some point, when we began to discuss the details of my elementary school years that had gone into the distant past - problems with homework, conflicts with some teachers and students - I suddenly felt like a child again. At least he vividly recalled his feelings of those days - acute shame, embarrassment and confusion. I tried to share with my interlocutor what I managed to learn over the following years about the learning process, but I did not clearly formulate my thoughts. Yes, I had all sorts of reasons for writing this book—to rethink discussions about education, to sharpen my own understanding of the process, and so on. who might need it.

We sat at Starbucks and shared memories. At some point, when we began to discuss the details of my elementary school years that had gone into the distant past - problems with homework, conflicts with some teachers and students - I suddenly felt like a child again. At least he vividly recalled his feelings of those days - acute shame, embarrassment and confusion. I tried to share with my interlocutor what I managed to learn over the following years about the learning process, but I did not clearly formulate my thoughts. Yes, I had all sorts of reasons for writing this book—to rethink discussions about education, to sharpen my own understanding of the process, and so on. who might need it.

A few years ago, an experiment was conducted in a New York girls' school. It was an old Catholic school, where everything looked gloomy and harsh, and crucifixes hung everywhere on the walls. The researchers invited female students in the first two grades of high school, girls in polo shirts and pleated skirts; they all then received small gifts for participating in the experiment.

In one of its parts, girls were taught to play darts. The psychologists who conducted the study divided them into several groups. The first group can be conditionally called "Result". The schoolgirls were told that they should learn the game by throwing darts as close to the center of the target as possible. In other words, the researchers told them that the surest way to win was to try to score a certain number of points.

Let's conditionally name the second group "Method of teaching". These girls learned how to play darts in a completely different way. They were aimed at gaining experience, and they learned how to throw darts correctly, mastering basic skills - for example, "keep your hand close to your body." And only after the girls began to show some skill, psychologists supported their desire to aim at the bull's-eye, gradually shifting the focus from intermediate learning tasks to achieving the final result [2] .

There was also a control group. What instructions were given to them? The researchers simply said, "Do your best!" In other words, the girls were free to use whatever approach they felt comfortable with. Let's call this group Worldly Wisdom.

What instructions were given to them? The researchers simply said, "Do your best!" In other words, the girls were free to use whatever approach they felt comfortable with. Let's call this group Worldly Wisdom.

To learn more about this experiment, I met with Anastasia Kitsantas, who conducted it with psychologist Barry Zimmerman. Several years have passed since the experiment, but Kitsantas still kept the little yellow darts in her office at George Mason University. On that rainy day, she took them out of the closet and showed me like a valuable relic from some forgotten South American tribe.

She kept these darts in memory of the study, which produced surprisingly significant results. By the end of the experiment, the girls in the Teaching Method group were head and shoulders above the others. Their results were almost twice as good as those of the World Wisdom group. In addition, they got much more pleasure from the process. “After the experiment was completed, some students asked me to tell more about this game and teach something else. These requests went on for several weeks,” Kitsantas told me.

These requests went on for several weeks,” Kitsantas told me.

The conclusion from the experiment was quite unambiguous and is supported by more and more new research. It turns out that learning is a process, a method, a system of understanding. This is an activity that requires focus, planning and analysis, and when people understand exactly how to learn, they acquire the required knowledge and skills much more effectively.

One of the most important predictors of learning outcomes was the process itself [3] . A recent analysis of studies has shown that the method of teaching has a very strong influence on the result in almost any field. Another analysis revealed the closest relationship between the learning process and the average academic score. After experimenting with darts, Kitsantas and Zimmerman conducted research in other areas: the results were similar. This led to the conclusion that targeted learning strategies significantly improve performance in a variety of activities - from playing volleyball to writing.

In the traditionally stern community of cognitive scientists, the latest wave of "learn to learn" research is generating a buzz comparable only to the second coming of Christ. Some scientists give their work catchy titles like "How to Boost Your IQ by 11 in 10 Minutes." (In this case, it is recommended to think aloud when solving problems.) Others give out interviews with enthusiasm. "We must spread this truth!" researcher Bennet Schwartz told me. (He advocates taking tests for himself.) [4]

Much of this excitement comes from the originality of the findings. The idea of a more focused approach to learning is only about 20 years old. For a long time, experts believed that learning ability was a matter of intelligence, and in general, they did not study it much. Apparently, they were simply convinced that a person either has the ability to learn or not. For them, intelligence and, therefore, the ability to achieve heights in any field was a kind of genetic gift from the gods - the same unchanging characteristic as, for example, eye color.

Schools, in turn, acted in harmony with science, and despite years of education—years spent in the classroom—most people never learned how to learn. Generally speaking, we simply did not have the right idea of how to increase our knowledge in this or that area or in this or that subject.

As an example, let's look at the word study. This is an extremely vague concept. What does "study" mean? Read a textbook? To solve problems? Remember? All of the above? Another example is the concept of practice. Practicing means doing the same thing over and over again? Do practical exercises require detailed feedback? Should they be difficult? Or vice versa - fun and exciting?

And there are many such misconceptions. When it comes to learning, people have a lot of beliefs that are completely unsupported by research. I work with some of the most respected education experts in the country. I recently did a survey: what do people know about the process of mastering skills? The results were stunning. The overwhelming majority of American respondents answered that they knew the basics of effective teaching and learning, but in fact, all their judgments come down to a huge number of intuitions and false beliefs, for the most part completely unfounded.

The overwhelming majority of American respondents answered that they knew the basics of effective teaching and learning, but in fact, all their judgments come down to a huge number of intuitions and false beliefs, for the most part completely unfounded.

For example, two-thirds of the respondents believe that students should be praised for being quick-witted. However, research shows the exact opposite: people learn better and learn more when their efforts are rewarded, not their intelligence. Half of the respondents believe that it is possible to learn effectively on their own, without any guidance, while one study after another shows that learning is a purposeful, active process. And finally, although there is no data to support the idea of learning styles - that some people are better at learning material kinesthetically, others visually, etc. - more than 80% of respondents believe in their existence [5] .

But it turned out that it is possible to improve and improve the learning process by spending not so much effort and time [6] . Many of the development strategies, hidden for the time being in the sterile conditions of scientific laboratories, make it possible to achieve very significant success with little additional effort, and during our meeting with Anastasia Kitsantas, she pointed out that even minor changes in attitudes can significantly increase the result. [7] . In the darts experiment, for example, about half of the girls on the Teaching Method team recorded their scores after each throw, and even that was enough to show significant improvement. “If you think about it, it’s absolutely phenomenal,” said Anastasia.

Many of the development strategies, hidden for the time being in the sterile conditions of scientific laboratories, make it possible to achieve very significant success with little additional effort, and during our meeting with Anastasia Kitsantas, she pointed out that even minor changes in attitudes can significantly increase the result. [7] . In the darts experiment, for example, about half of the girls on the Teaching Method team recorded their scores after each throw, and even that was enough to show significant improvement. “If you think about it, it’s absolutely phenomenal,” said Anastasia.

But, of course, most of us rarely think about something like that.

The value of the learning process goes far beyond modern science. In addition, this process reflects the nature of today's society - and the changing essence of professionalism.

Think back to your last Google search. Maybe you were looking for the address of a local pizzeria or Michael Jackson's hometown? According to a series of studies conducted by Betsy Sparrow and her colleagues, we are better at remembering exactly where we found information on the Internet than the details of the information itself [8] .

So, if you were looking for information about the hometown of Michael Jackson, you will remember the Wikipedia page dedicated to the King of Pop rather than the information itself (Gary, Indiana). And after searching for a pizzeria, the URL of the site (greatpizza.com) is more likely to remain in your memory than the real address of the restaurant. “We are becoming symbionts with our digital gadgets,” write Sparrow and colleagues, “forming interconnected systems with them that remember the information itself less than where it can be found” [9] .

A number of important conclusions can be drawn from such studies. Firstly, our brain and its various features are mainly responsible for the effectiveness of learning: it has the ability to dump information to “unload” information in order to store it not in its own convolutions, but somewhere else. In this respect, our smartphones, iPads, and laptops have become what one author has called a “brain prosthesis,” and recent research suggests that we are less likely to remember a painting we see in a museum if we take a picture of it. It seems that our brain knows that the image is stored on a digital device, and no longer spends effort on remembering.

It seems that our brain knows that the image is stored on a digital device, and no longer spends effort on remembering.

There is a second, more important, conclusion that leads us to a deeper understanding of the essence of the Digital Age: facts have lost a significant part of their value. For almost all of us today, it's not the data itself that matters, but how it helps us think better. More precisely, how to master new skills more effectively? What is the best way to deal with complex tasks? When does it make sense to store information in the head, and when is it preferable to trust the computer?

Let's turn to ancient history. Take, for example, the man known as Ötzi [10] . He lived in the Italian Alps about 5000 years ago, at the beginning of the Bronze Age. By modern standards, he was small in stature - a little over one and fifty, and his face was covered with a thick, matted beard. The forehead hung low over the eyes. His nose was once broken, which made him look like an elderly former boxer.

Ötzi died while making his way along a steep path among the alpine ridges, and fell under a rock, clenching his fists and stretching out his weary legs. An arrow hit him in the shoulder - blood gushed out in a stream, and death came quickly. The dead body of Ötzi, perfectly preserved thanks to eternal snow and ice, was discovered by random tourists only 1991 year.

Archaeologists who studied Ötzi's body concluded that he possessed important knowledge and skills. A bunch of half-finished arrows hung from his shoulder, indicating that he was familiar with the basics of weapon-making. The metal particles found on the hair suggested that the smelting process was also known to Ötzi firsthand. Judging by the not-too-successful attempts to mend clothes with the help of grass stalks, to some extent he also mastered the art of sewing.

But today we do not need the same knowledge that Ötzi possessed. From the moment he left his native Alpine valley, and literally until recently, information was, on the one hand, static, and on the other, very expensive. At the same time, we have become accustomed to reverently treat information: for centuries it could only be obtained from a rare few manuscripts, and later, after the invention of the printing press by Gutenberg, from worn folios. As children, many of us had to sit in libraries for hours, straining our eyes over dozens of books, magazines, and microfilm, in order to write a school report. Preparing for the tests, we studied textbooks, memorizing pages of text, dates and formulas.

At the same time, we have become accustomed to reverently treat information: for centuries it could only be obtained from a rare few manuscripts, and later, after the invention of the printing press by Gutenberg, from worn folios. As children, many of us had to sit in libraries for hours, straining our eyes over dozens of books, magazines, and microfilm, in order to write a school report. Preparing for the tests, we studied textbooks, memorizing pages of text, dates and formulas.

The same teaching principle continues to be applied in most schools, colleges and vocational education programs. It is enough to take any thick textbook from the shelf to be convinced of this. I have worked with curriculum specialists Morgan Polikoff and John Smithson and found that more than 95% of the material in one of the widely used elementary school math textbooks is designed to work at the lower levels of thinking - remembering facts and memorizing rules.

But in the age of the Internet, information has become incredibly cheap. With a search engine, we can figure out in a fraction of a second how, for example, blood plasma binds proteins. Any disputes at parties are very quickly resolved by moving a finger across the smartphone screen. Moreover, the very concept of professionalism is constantly changing. The life cycle of competence in a given area is getting shorter: for example, over the past ten years, Uber has gone from a little-known app to a literal household name.

With a search engine, we can figure out in a fraction of a second how, for example, blood plasma binds proteins. Any disputes at parties are very quickly resolved by moving a finger across the smartphone screen. Moreover, the very concept of professionalism is constantly changing. The life cycle of competence in a given area is getting shorter: for example, over the past ten years, Uber has gone from a little-known app to a literal household name.

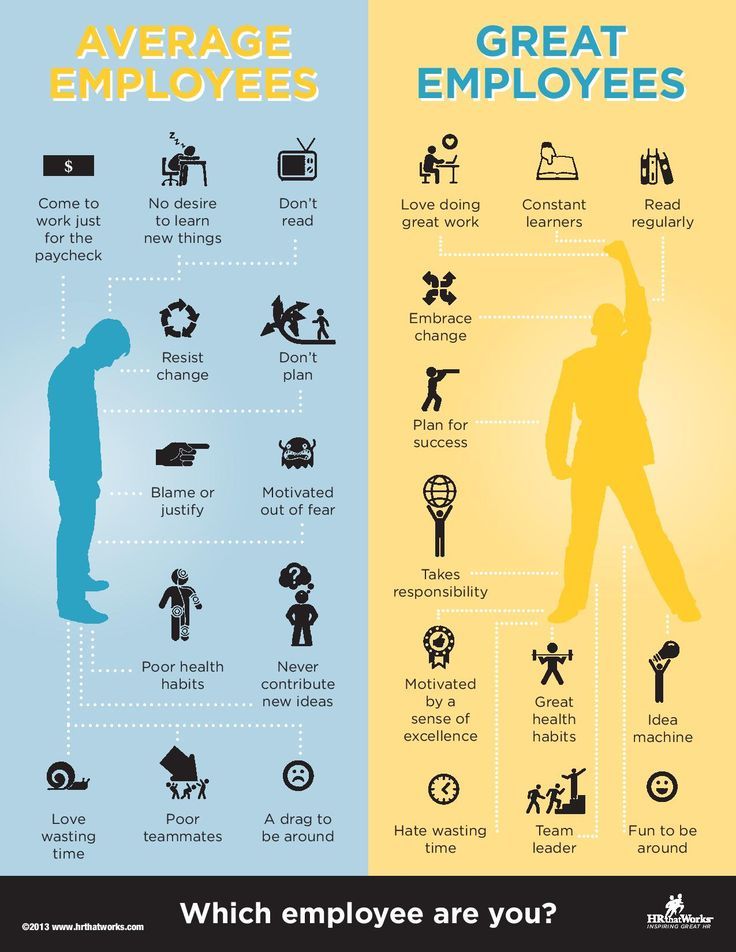

How and why do we acquire new knowledge and skills? Goals and objectives have also changed. To achieve excellence in your field, it is no longer enough just to practice. To be successful, we need more than just following simple procedures. The modern world requires people to learn and develop important thinking skills.

It's easy to go too far here, so let's clear things up right away. Facts continue to play a crucial role today. Knowledge is the basis of learning. Memorization remains an important tool, and what you know still largely determines what you are able to learn. I call it knowledge effect , and we will return to this topic often in the pages of the book: to achieve mastery, you need to be fluent in the basics.

I call it knowledge effect , and we will return to this topic often in the pages of the book: to achieve mastery, you need to be fluent in the basics.

But knowing the facts is only the beginning. Learning as a process also implies the ability to see relationships, determine cause and effect, find analogies and similarities. Ultimately, the goal of learning is to change our thinking about some fact or idea, and when we learn, we seek to acquire a certain system of thinking.

So, if we study microeconomics, we need to learn to think microeconomically. If we are learning to knit, we must learn to think like a professional knitter. Want to learn how to scuba dive? Try learning how to think like a world class diver. According to specialists in educational psychology, “learning should be perceived as a process of orientation in parts of an organized and understandable system” [11] .

The implications of this new approach are significant, and you can find the cause right here on your own smartphone. Advances in modern technology have drastically reduced the need for professions that require procedural thinking. To a certain extent, they can be called obsolete. With the advent of online travel services, the disappearance of travel agents is almost a foregone conclusion. ATMs destroyed bank tellers, and cash desks and self-service counters pushed out employees of shops and service institutions.

Advances in modern technology have drastically reduced the need for professions that require procedural thinking. To a certain extent, they can be called obsolete. With the advent of online travel services, the disappearance of travel agents is almost a foregone conclusion. ATMs destroyed bank tellers, and cash desks and self-service counters pushed out employees of shops and service institutions.

These changes are happening faster than even the most daring experts could imagine. For example, about ten years ago, Harvard economists Richard Murnane and Frank Levy published The New Division of Labor, in which they made various assumptions about what professions will continue to exist in the future [12] . For example, they believed that secretaries would disappear from offices very soon, as the corresponding duties would be completely taken over by computers. The same, in their opinion, applied to working professions.

But, they said, a computer could never drive a car. To two economists, driving seemed too complex an activity for any device to perform. Most of their predictions actually turned out to be correct. Secretarial work as such has practically disappeared, as have many working professions. But with cars on autopilot, experts missed: various companies, from Google to Tesla, have already launched the production of such cars, and taxis in which there are no taxi drivers drive around, for example, through the streets of Singapore.

To two economists, driving seemed too complex an activity for any device to perform. Most of their predictions actually turned out to be correct. Secretarial work as such has practically disappeared, as have many working professions. But with cars on autopilot, experts missed: various companies, from Google to Tesla, have already launched the production of such cars, and taxis in which there are no taxi drivers drive around, for example, through the streets of Singapore.

I once visited Murnane at his home near Boston. As soon as I saw him, I immediately thought: he is a typical Harvard economics professor! He had a gray beard, glasses, and a National Bureau of Economic Research sweatshirt. I noticed a hole in one of the socks.

When we sat down with him in the living room, Murnane began to prove to me that autopilots are just the exception that proves the rule. Technology is changing the world faster than most people can imagine, and in his opinion, to be successful today, you need to have "professional thinking skills. " From a practical point of view, this means that people should be able to solve “unstructured problems”. If you are a computer specialist, you must deal with technical problems that are not described in the instruction manual. If you are a speech therapist, you should be able to help children whose speech disorders are difficult to identify.

" From a practical point of view, this means that people should be able to solve “unstructured problems”. If you are a computer specialist, you must deal with technical problems that are not described in the instruction manual. If you are a speech therapist, you should be able to help children whose speech disorders are difficult to identify.

At the same time, according to Murnaine, people need to learn to develop understanding from new information. So, if you work in the advertising business, you should be able to explain to the client how he can benefit from what he heard on the news today. If you are a stockbroker, it is important for you to understand how climate change can affect grain sales.

Thus, this book is not just for students, and in the following pages I will talk about how to increase the effectiveness of any work related to knowledge. For example, when solving complex problems, it makes sense to look for analogies outside the scope of your activity. If you're having trouble making a movie, look for innovative tips in the music industry. If you are solving a marketing problem, refer to the experience of journalists.

If you are solving a marketing problem, refer to the experience of journalists.

TEST QUESTION #1

What is the most effective way to learn the main ideas of the text?

A. Circle key concepts in the text.

B. Reread the text.

B. Do a short practice test on the material presented in the text.

D. Highlight the main ideas of the text.

In this book, I will talk about how to improve your skills in solving new problems and teach you how to succinctly state the essence of the problem you are working on. A precise definition of the problem often contributes to its solution. We will also talk about various aspects of management, such as the importance of learning from colleagues and analyzing the results of the work done. After all, in the end, the role of a leader is largely about helping people grow and develop.

More broadly, we must understand that in an information world where facts and figures are pouring in, where even cars are already driving by themselves, we must learn to master new forms of skill quickly and efficiently. The ability to learn is our “master survival tool,” one of the most important talents of the modern age. This skill should take precedence over all others. If you know how to learn, you can learn almost anything, and from the point of view of society as a whole, we need more advanced forms of education, where information and knowledge reinforce the skill of problem solving - perhaps the most important thing in our lives.

The ability to learn is our “master survival tool,” one of the most important talents of the modern age. This skill should take precedence over all others. If you know how to learn, you can learn almost anything, and from the point of view of society as a whole, we need more advanced forms of education, where information and knowledge reinforce the skill of problem solving - perhaps the most important thing in our lives.

Still don't believe? Ask Google.

One could say that in a certain sense my interest in the learning process was rekindled by a single letter [13] . At the time, I was working on a project to measure the performance of school districts based on the amount of money spent. We had to get data for almost every county in the country, and it took months. But the data was inconclusive. There were problems with the statistics. For example, if you want to know how effective schools are in a given district, how do you account for the fact that poor children often come to school without breakfast?

And one day, late in the project, a letter arrived in my mailbox. My assistant loaded a lot of data into the statistical program and got confirmation of what we already knew: the results are not directly related to costs. In some places, the situation turned out to be simply egregious: there was a small, but negative correlation between the money spent and school grades. In other words, if you were Billy Bean from The Man Who Changed Everything, you would look at our data and decide that the more money spent on some schools, the lower their students' grades.

My assistant loaded a lot of data into the statistical program and got confirmation of what we already knew: the results are not directly related to costs. In some places, the situation turned out to be simply egregious: there was a small, but negative correlation between the money spent and school grades. In other words, if you were Billy Bean from The Man Who Changed Everything, you would look at our data and decide that the more money spent on some schools, the lower their students' grades.

1. Ivy League - eight of the most prestigious private universities in the US, located in the northwest of the country.

2. Barry J. Zimmerman and Anastasia Kitsantas, "Developmental Phases in Self-Regulation: Shifting from Process Goals to Outcome Goals," Journal of Educational Psychology 89, no. 1 (1997): 29.

3. Hester de Boer et al., Effective Strategies for Self-Regulated Learning: A Meta-Analysis (Gronigen: GION/RUG, 2013). See also Kiruthiga Nandagopal and K. Anders Ericsson, "An Expert Performance Approach to the Study of Individual Differences in Self-Regulated Learning Activities in Upper-Level College Students," Learning and Individual Differences 22, no. 5 (2012): 597–609.

5 (2012): 597–609.

4. Anastasia Kitsantas and Barry J. Zimmerman, "Comparing Self-Regulatory Processes Among Novice, Non-Expert, and Expert Volleyball Players: A Micro Analytic Study," Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 14, no. 2 (2002): 91–105; Barry J. Zimmerman and Anastasia Kitsantas, "Acquiring Writing Revision Skill: Shifting from Process to Outcome Self-Regulatory Goals," Journal of Educational Psychology 91, no. 2 (1999): 241. See also: Mark C. Fox and Neil Charness, "How to Gain Eleven IQ Points in Ten Minutes: Thinking Aloud Improves Raven's Matrices Performance in Older Adults," Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition 17, no . 2 (2010): 191–204.

5. Ulrich Boser, "Does the Public Know What Great Teaching and Learning Look Like?" Center for American Progress, in press. Note that the study uses a convenient sample that we believe can be extrapolated to the entire country. The document will be available on my site and the site of the center.

6. Louis Alfieri et al. , "Does Discovery-Based Instruction Enhance Learning?" Journal of Educational Psychology 103, no. 1 (2011): 1–18. See also Richard E. Mayer, "Should There Be a Three-Strikes Rule Against Pure Discovery Learning?" American Psychologist 59, no. 1 (2004): 14–19.

, "Does Discovery-Based Instruction Enhance Learning?" Journal of Educational Psychology 103, no. 1 (2011): 1–18. See also Richard E. Mayer, "Should There Be a Three-Strikes Rule Against Pure Discovery Learning?" American Psychologist 59, no. 1 (2004): 14–19.

7. Harold Pashler et al., "Psychological Science in the Public Interest," Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence 9, no. 3 (2008): 105–119. See also: Thomas K. Fagan and Daniel T. Willingham, "Do Visual, Auditory, and Kinesthetic Learners Need Visual, Auditory, and Kinesthetic Instruction?" American Educator (Summer 2005): 31–35.

8. Katherine Hobson, "Google on the Brain: How the Internet Has Changed What We Remember," Wall Street Journal, July 15, 2011. Full study: Betsy Sparrow, Jenny Lui, and Daniel M. Wegner, "Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips," Science 333, no. 6043 (2011): 776–778.

Linda A. Henkel, "Point and Shoot Memories: The Influence of Taking Photos on Memory for a Museum Tour," Psychological Science 25, no. 2 (2014): 396–402. Brain quotation from James Gleick, "Auto Correct This!" New York Times, August 4, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/05/opinion/sunday/auto-correct-this.html. Brenda Fowler, Iceman: Uncovering the Life and Times of a Prehistoric Man Found in an Alpine Glacier, 1st ed. (New York: Random House, 2000). I also got information from: Bob Cullen, "Testimony from the Iceman," Smithsonian, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/testimony-from-the-iceman-75198998/ (accessed 09/13/2016) and from the website of the South Tyrolean Museum of Archaeology: http://iceman .it/en/ (date of access: 20.09.2016).

2 (2014): 396–402. Brain quotation from James Gleick, "Auto Correct This!" New York Times, August 4, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/05/opinion/sunday/auto-correct-this.html. Brenda Fowler, Iceman: Uncovering the Life and Times of a Prehistoric Man Found in an Alpine Glacier, 1st ed. (New York: Random House, 2000). I also got information from: Bob Cullen, "Testimony from the Iceman," Smithsonian, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/testimony-from-the-iceman-75198998/ (accessed 09/13/2016) and from the website of the South Tyrolean Museum of Archaeology: http://iceman .it/en/ (date of access: 20.09.2016).

11. Richard Paul and Linda Elder's The Thinker's Guide for Students on How to Study and Learn a Discipline: Using Critical Thinking Concepts & Tools, Foundation for Critical Thinking (2003). See also: Lindsey Engle Richland and Nina Simms, "Analogy, Higher Order Thinking, and Education," Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 6, no. 2 (March 2015): 177–192.

2 (March 2015): 177–192.

Frank Levy and Richard J. Murnane, The New Division of Labor: How Computers Are Changing the Way We Work (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004). It was Ted Dintersmith who first told me about Levy and Murnane's prediction about self-driving cars. For a more modern take on the problem, see Derek Thompson, "What Jobs Will the Robots Take?" The Atlantic, January 23, 2014. http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/01/what-jobs-will-the-robots-take/283239/.

13. Ulrich Boser, "Return on Educational Investment: A District-by-District Evaluation of US Educational Productivity," Center for American Progress, January 2011. 50% figure taken from: Scott Freeman, Sarah L. Eddy, Miles McDonough , Michelle K. Smith, Nnadozie Okoroafor, Hannah Jordt, and Mary Pat Wenderoth, "Active Learning Increases Student Performance in Science, Engineering, and Mathematics," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, no. 23 (2014): 8410–8415; doi:10.1073/pnas.131

23 (2014): 8410–8415; doi:10.1073/pnas.131

11. Note that Freeman analyzed only the results of the exact sciences courses.

How to learn to read 3 times faster in 20 minutes

October 6, 2020Education

Grab a book and check the effect for yourself right now.

Iya Zorina

Lifehacker author, athlete, CCM

Share

0Background: "Project PX"

Back in 1998, Princeton University hosted a seminar "Project PX" (Project PX), dedicated to high speed reading. This article is an excerpt from that seminar and personal experience of speeding up reading.

So, "Project PX" is a three-hour cognitive experiment that allows you to increase your reading speed by 386%. It was conducted on people who spoke five languages, and even dyslexics were trained to read up to 3,000 words of technical text per minute, 10 pages of text. Page in 6 seconds.

For comparison, the average reading speed in the US is between 200 and 300 words per minute. We have in connection with the peculiarities of the language - from 120 to 180. And you can easily increase your performance to 700-900 words per minute.

We have in connection with the peculiarities of the language - from 120 to 180. And you can easily increase your performance to 700-900 words per minute.

All that is needed is to understand how human vision works, what time is wasted in the process of reading and how to stop wasting it. When we analyze the mistakes and practice not making them, you will read several times faster and not mindlessly running your eyes, but perceiving and remembering all the information you read.

Preparation

For our experiment you will need:

- a book of at least 200 pages;

- pen or pencil;

- timer.

The book should lie in front of you without closing (press the pages if it tries to close without support).

Find a book that does not need to be held so that it does not closeYou will need at least 20 minutes for one session of exercises. Make sure that no one distracts you during this time.

Helpful Hints

Before jumping straight into the exercises, here are a few quick tips to help you speed up your reading.

1. Make as few stops as possible when reading a line of text

When we read, the eyes move through the text not smoothly, but in jumps. Each such jump ends with fixing your attention on a part of the text or stopping your gaze at areas of about a quarter of a page, as if you were taking a picture of this part of the sheet.

Each eye stop on the text lasts ¼ to ½ second.

To feel this, close one eye and lightly press the eyelid with the tip of your finger, and with the other eye try to slowly slide over the line of text. Jumps become even more obvious if you slide not in letters, but simply in a straight horizontal line:

How do you feel?

2. Try to go back as little as possible through the text

A person who reads at an average pace quite often goes back to reread a missed moment. This can happen consciously or unconsciously. In the latter case, the subconscious itself returns its eyes to the place in the text where concentration was lost.

On average, conscious and unconscious returns take up to 30% of the time.

3. Improve your concentration to increase the coverage of words read in one stop

People with an average reading speed use a central focus rather than horizontal peripheral vision. Due to this, they perceive half as many words in one jump of vision.

4. Practice Skills Separately

The exercises are different and you don't have to try to combine them into one. For example, if you are practicing reading speed, don't worry about text comprehension. You will progress through three stages in sequence: learning technique, applying technique to increase speed, and reading comprehension.

Rule of thumb: Practice your technique at three times your desired reading speed. For example, if your current reading speed is somewhere around 150 words per minute, and you want to read 300, you need to practice reading 900 words per minute.

Exercises

1.

Determination of the initial reading speed

Determination of the initial reading speed Now you have to count the number of words and lines in the book that you have chosen for training. We will calculate the approximate number of words, since calculating the exact value will be too dreary and time consuming.

First, we count how many words fit in five lines of text, divide this number by five and round it up. I counted 40 words in five lines: 40 : 5 = 8 - an average of eight words per line.

Next, we count the number of lines on five pages of the book and divide the resulting number by five. I got 194 lines, I rounded up to 39 lines per page: 195 : 5 = 39.

And the last thing: we count how many words fit on the page. To do this, we multiply the average number of lines by the average number of words per line: 39× 8 = 312.

Now is the time to find out your reading speed. We set a timer for 1 minute and read the text, calmly and slowly, as you usually do.

How much did it turn out? I have a little more than a page - 328 words.

2. Orientation and speed

As I wrote above, returning through the text and stopping the gaze take a lot of time. But you can easily cut them down with a focus tracking tool. A pen, pencil or even your finger will serve as such a tool.

Technique (2 minutes)

Practice using a pen or pencil to maintain focus. Move the pencil smoothly under the line you are currently reading and concentrate on where the tip of the pencil is now.

Leading the lines with the tip of the pencilSet the pace with the tip of the pencil and follow it with your eyes, keeping up with stops and returns through the text. And don't worry about understanding, it's a speed exercise.

Try to go through each line in 1 second and increase the speed with each page.

Do not stay on one line for more than 1 second under any circumstances, even if you do not understand what the text is about.

With this technique, I was able to read 936 words in 2 minutes, so 460 words per minute. Interestingly, when you follow with a pen or pencil, it seems that your vision is ahead of the pencil and you read faster. And when you try to remove it, immediately your vision seems to spread out over the page, as if the focus was released and it began to float all over the sheet.

Interestingly, when you follow with a pen or pencil, it seems that your vision is ahead of the pencil and you read faster. And when you try to remove it, immediately your vision seems to spread out over the page, as if the focus was released and it began to float all over the sheet.

Speed (3 minutes)

Repeat the tracker technique, but allow no more than half a second to read each line (read two lines of text in the time it takes to say "twenty-two").

You probably won't understand anything you read, but that doesn't matter. Now you are training your perceptual reflexes, and these exercises help you adapt to the system. Do not slow down for 3 minutes. Concentrate on the tip of your pen and the technique for increasing speed.

In the 3 minutes of this frenetic race, I read five pages and 14 lines, averaging 586 words per minute. The hardest part of this exercise is not to slow down the speed of the pencil. This is a real block: you have been reading all your life in order to understand what you are reading, and it is not so easy to let go of this.

Thoughts cling to the lines in an effort to return to understand what it is about, and the pencil also begins to slow down. It is also difficult to maintain concentration on such useless reading, the brain gives up, and thoughts fly away to hell, which is also reflected in the speed of the pencil.

3. Expanding the field of perception

When you concentrate your eyes on the center of the monitor, you still see its outer areas. So it is with the text: you concentrate on one word, and you see several words surrounding it.

Now, the more words you learn to see in this way with your peripheral vision, the faster you can read. The expanded area of perception allows you to increase the speed of reading by 300%.

Beginners with a normal reading speed spend their peripheral vision on the fields, that is, they run their eyes through the letters of absolutely all the words of the text, from the first to the last. At the same time, peripheral vision is spent on empty fields, and a person loses from 25 to 50% of the time.

A boosted reader will not "read the fields". He will run his eyes over only a few words from the sentence, and see the rest with peripheral vision. In the illustration below, you see an approximate picture of the concentration of vision of an experienced reader: words in the center are read, and foggy ones are marked by peripheral vision.

Focus on central wordsHere is an example. Read this sentence:

The students once enjoyed reading for four hours straight.

If you start reading with the word "students" and end with "reading," you save time on reading as many as five words out of eight! And this reduces the time for reading this sentence by more than half.

Technique (1 minute)

Use a pencil to read as fast as possible: start with the first word of the line and end with the last. That is, no expansion of the area of perception yet - just repeat exercise No. 1, but spend no more than 1 second on each line. Under no circumstances should one line take more than 1 second.

Technique (1 minute)

Continue to pace the reading with a pen or pencil, but start reading from the second word of the line and end the line two words before the end.

Speed (3 minutes)

Start reading at the third word of the line and finish three words before the end, while moving your pencil at the speed of one line per half second (two lines in the time it takes to say "twenty-two" ).

If you don't understand anything you read, that's okay. Now you are training your reflexes of perception, and you should not worry about understanding. Concentrate on the exercise with all your might and don't let your mind drift away from an uninteresting activity.

4. Testing your new reading speed

Now it's time to test your new reading speed. Set a timer for 1 minute and read as fast as you can while still understanding the text. I got 720 words per minute - twice as fast as before I started using this technique.

These are great figures, but they are not surprising, because you yourself begin to notice how the scope of words has expanded.