5 levels of phonological awareness

5 Important Levels of Phonemic Awareness

by Manpreet Singh

Last Updated on October 13, 2022 by Editorial Team

We all see small children trying to pick words from family members; that is why a home is called the first school for a child. But, is a child while imitating parents and siblings showing phonemic awareness? The answer is no.

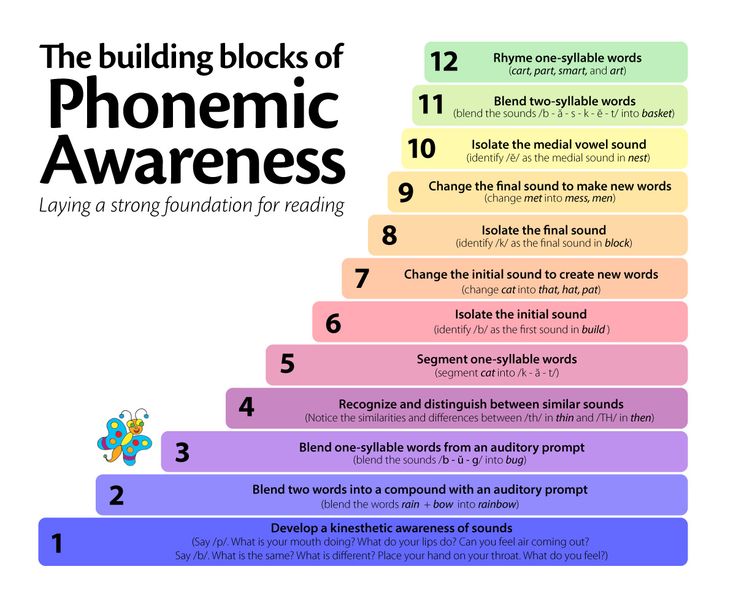

A child is admitted to a preschool or is home trained to learn to read and write. This ‘learning to read’ is called attaining phonemic awareness. It has five distinct levels that coincide with the milestones of a progressive learning curve. This means the student has to be conversant with the phoneme, the smallest unit of the sound of a letter, at the start. And then, the student learns to blend, rhyme, and identify them apart too.

Let’s go through crucial levels of phonemic awareness that play an important role in building reading skills.

If we break down a word into letters, we will realize that every letter corresponds to a starting sound, a middle sound, and an ending sound. All these sounds are called phonemes. The ability to manipulate these sounds and employ them to sound out words correctly is nothing but phonemic awareness. So, this awareness is achieved when a learner absorbs the following levels of phonemic cognition (Adams, 1990):

1. Phoneme segmentationThe phenome segmentation can include the segmentation of syllables. It further progresses to the segmentation of a word and then to that of a sentence. It involves literally counting and sounding out the phonemes separately to understand a word’s sound. Since phonemic awareness is the ability to recognize the sounds of parts of the word/letter/sentence, it means differently while moving from word to sentence segmentation. For example,

- When trying to grasp syllable segmentation, a learner is actually internalizing how the letter sounds differently.

Knowing which parts of the mouth are being used to sound a particular letter helps attain pronunciation proficiency. Also, it improves word recognition[1] and helps bring improved reading comprehension.

Knowing which parts of the mouth are being used to sound a particular letter helps attain pronunciation proficiency. Also, it improves word recognition[1] and helps bring improved reading comprehension. - On moving to word segmentation[2], cognition is focused on the starting, middle, and ending sounds that compose the word. It extracts some parts of phonological learning that teach rhyming and alliteration.

- Finally, when the sentence segmentation is learned, each word’s sound is worked out to help correct pronunciation and prosody while reading.

It refers to the blending and splitting of phonemes to create new words. Once the student learns the sound of each phoneme, the correct blending is required to read the word correctly.

So, the concept of onset-riming, which means sounding out the beginning (onset) and end (riming), is learned by splitting and blending the phonemes mentally. When teachers ask to speak and write, they are given the pretext to learn spellings using phoneme splitting and blending.

When teachers ask to speak and write, they are given the pretext to learn spellings using phoneme splitting and blending.

Phoneme rhyming and alliteration involve words that represent a common sound. Rhyming focuses on the commonality of ending sounds, while alliteration focuses on learning words that start with the same sound. When the teacher asks a child to write rhyming words, the answers are mostly those words that have the same letters in rhyming. This means, learning ‘pack’, ‘back’, and ‘lack’ are examples of rhyming.

Alliteration practice involves learning tongue twisters. ‘She sells seashells on the seashore’, and other such phrases give an idea of alliteration. It acquaints a child with various repetitions of the same sound.

4. Phoneme Comparing and ContrastingWords change when contrasting phonemes are used to make the word sound. Means, f, and v are the contrasting phonemes because these are sounded out by applying phonetic differences. And, using these sounds replaceable changes the meaning of the word entirely. Fan and Van may be rhyming, but phonetic difference leading to different meanings of words puts them in contrasting phoneme categories. (Essentials of Linguistics, e-book, Chapter 4: Speech Sounds in Mind)

And, using these sounds replaceable changes the meaning of the word entirely. Fan and Van may be rhyming, but phonetic difference leading to different meanings of words puts them in contrasting phoneme categories. (Essentials of Linguistics, e-book, Chapter 4: Speech Sounds in Mind)

Similarly, phonemic comparison can help know if the phonemes sounding similar are different/unique or are allophones of the same phoneme. While allophones are sounds, the phonemes are a set of those sounds. The comparison is helpful in understanding how a particular phoneme of the English language can be used to speak two different words having different sounds. For example, a Spanish person speaking dough and though will not use different phonemes, but allophones of the same phoneme.

5. Phoneme manipulationThe ability to move or alter individual phonemes while retaining in mind their specific roles in constituting a word’s sound is described as phonemic manipulation. Several activities happen behind a simple act of reading. Learners cognitively delete, add, substitute, or rearrange sounds to arrive at the correct way of voicing the word. This process is required to be fluent in reading connected text.

Learners cognitively delete, add, substitute, or rearrange sounds to arrive at the correct way of voicing the word. This process is required to be fluent in reading connected text.

Phoneme manipulation helps in building an advanced understanding of phonemic awareness. Through the processes of adding, deleting, and arranging, the learners can find ways to create new words. For example, removing ‘b’ from ‘blast’ can give ‘last’ (phoneme subtracting), and replacing ‘p’ in ‘plastic with ‘e’ can help generate the word ‘elastic’. The early readers can understand how these simple processes can lead to ease of populating the list of words they know. So, apart from building reading ease, phoneme manipulation helps to develop vocabulary.

To conclude,Building phonemic awareness means learning to read (from Book Overcoming Dyslexia, Schaywitz, 2003). It is the total of recognizing and blending phonemes to build words, further developing reading skills. The presence of this awareness in reading beginners is one of the parameters to assess learning difficulties in children if any.

The presence of this awareness in reading beginners is one of the parameters to assess learning difficulties in children if any.

References

- Müller, B., Richter, T., & Karageorgos, P. (2020). Syllable-based reading improvement: Effects on word reading and reading comprehension in Grade 2. Learning and Instruction, 66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101304

- Alhumsi, Mohammad & Shabdin, Ahmad. (2016). The Relationship between Phonemic Segmentation Skill and EFL Word Recognition – A Review of Literature. International Journal of Linguistics. 8. 31. 10.5296/ijl.v8i2.9097.

The Big Five: Phonological and Phonemic Awareness – Part 1

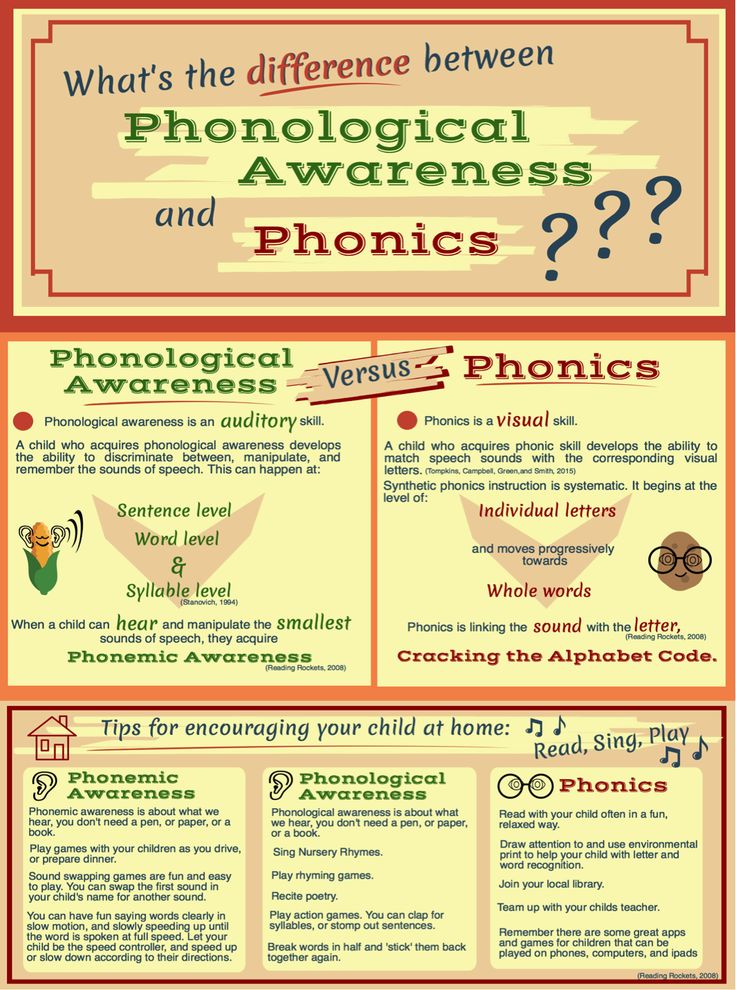

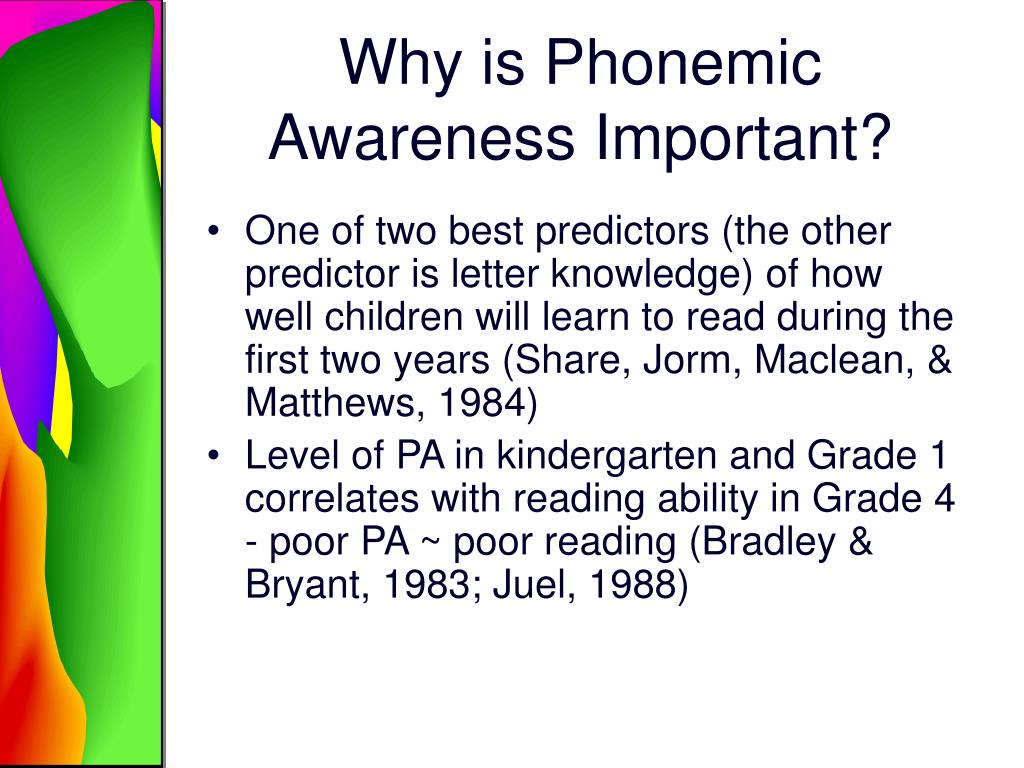

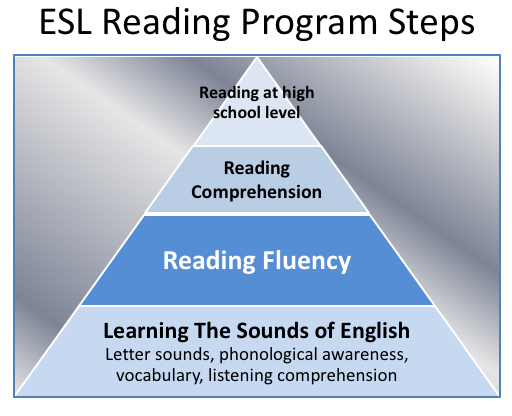

In “The National Reading Panel and the Big Five,” I introduced you to the origins of “The Big Five” essentials for reading. Today, I am going to discuss the first of the “Five,” which is Phonological and Phonemic Awareness. This area is so important to remediation, that I will cover it over two blogs. It is the foundation upon which all the other layers are built and, unless it is solid, the other layers will most definitely suffer, and the student will struggle to read. Phonological and phonemic awareness is, of course, the core deficit for dyslexic students, and the most common cause of poor reading. That said, these difficulties can be preempted and corrected before the child starts reading, but before we go any deeper into this topic, I need to define phonological and phonemic awareness.

It is the foundation upon which all the other layers are built and, unless it is solid, the other layers will most definitely suffer, and the student will struggle to read. Phonological and phonemic awareness is, of course, the core deficit for dyslexic students, and the most common cause of poor reading. That said, these difficulties can be preempted and corrected before the child starts reading, but before we go any deeper into this topic, I need to define phonological and phonemic awareness.

When we talk about a student having “auditory problems,” this refers to all the sounds they hear. “Phonological,” on the other hand, refers only to the sounds of spoken language. Students that have learning difficulties generally don’t have auditory problems that are not related to speech sounds. They can understand, speak, and communicate using language, because their phonological issues are related to parts of words, rather than whole words. Reading is a challenge for them because our ability to decode (read) is based on being able to break words apart, and to match those parts to their written parts or letters. In other words, as David Kilpatrick says, “they struggle to connect parts of spoken language to their alphabetic forms.” [Sources #1, below.]

In other words, as David Kilpatrick says, “they struggle to connect parts of spoken language to their alphabetic forms.” [Sources #1, below.]

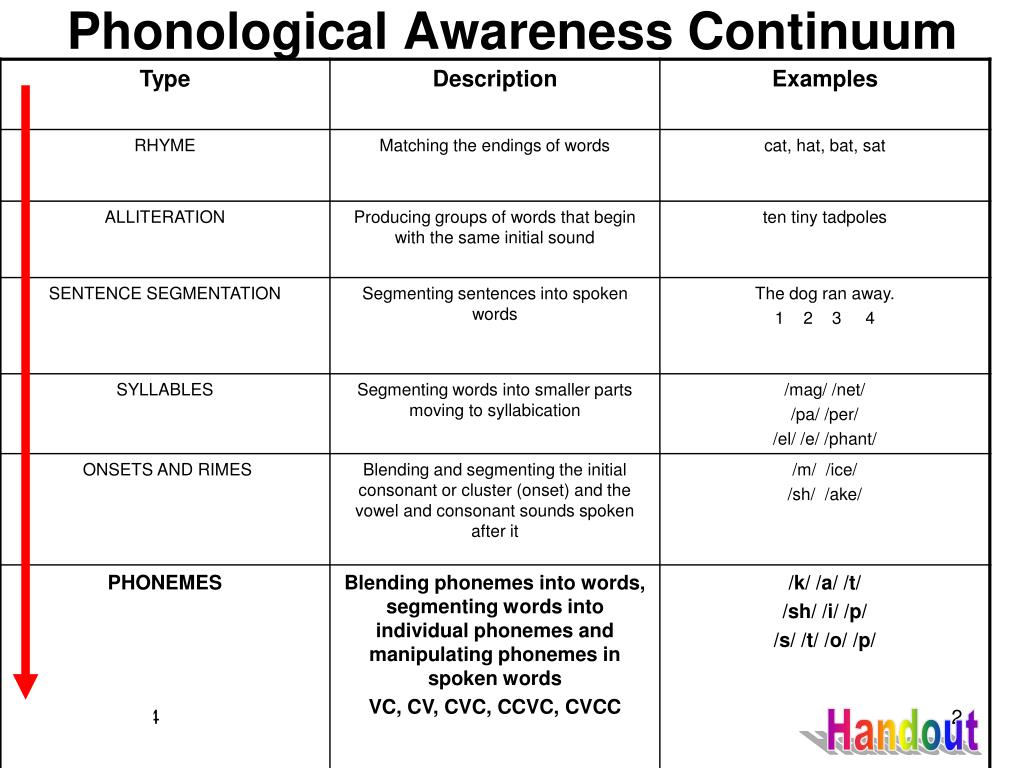

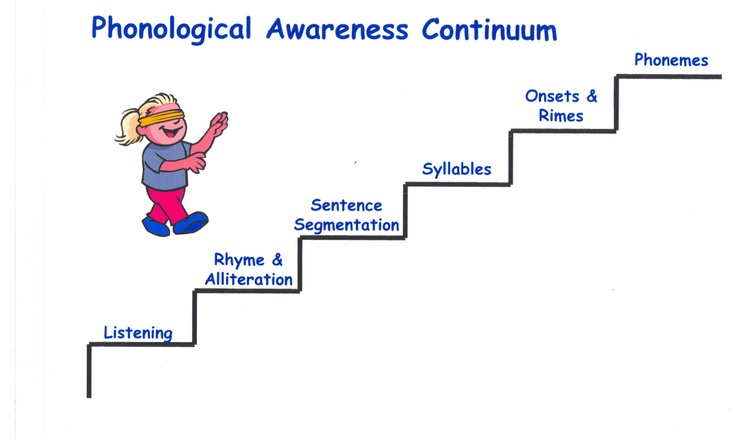

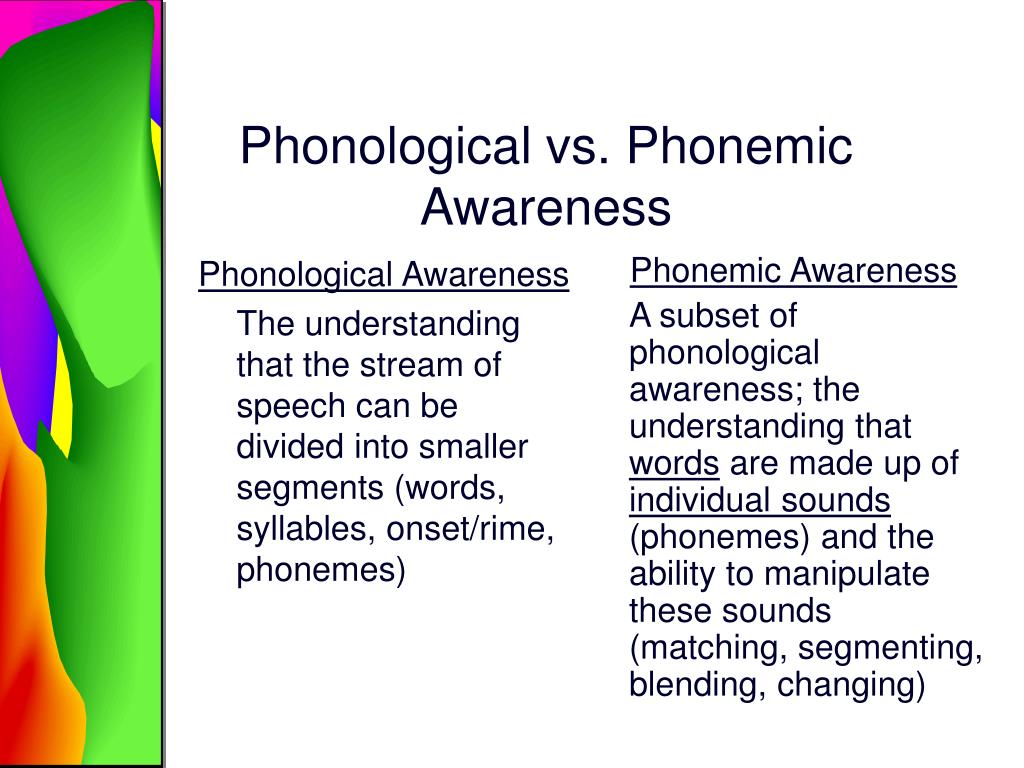

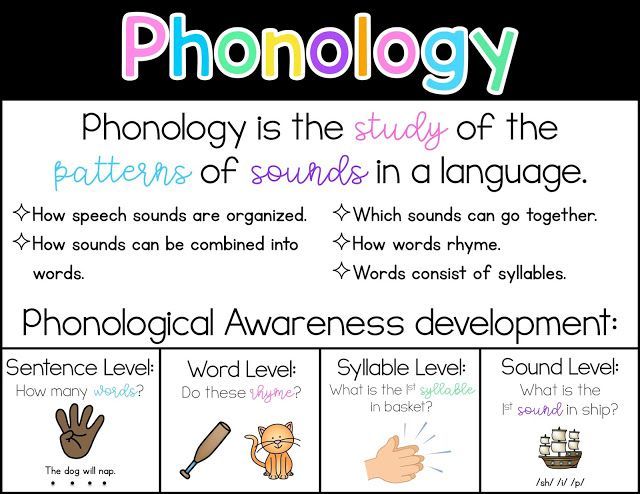

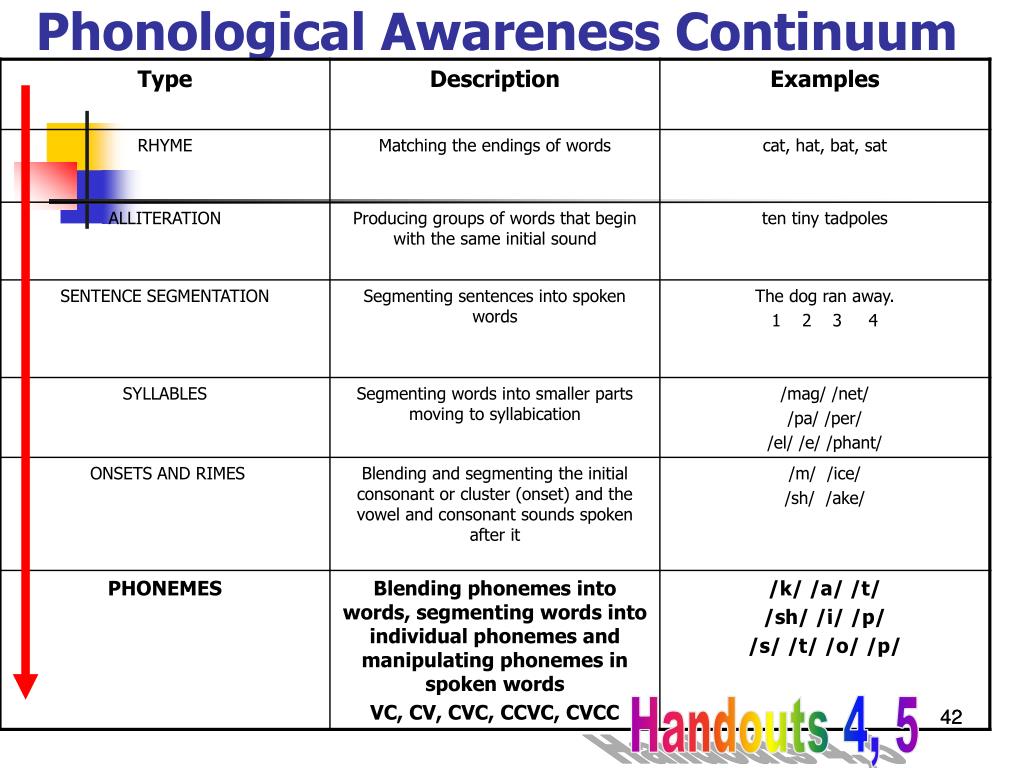

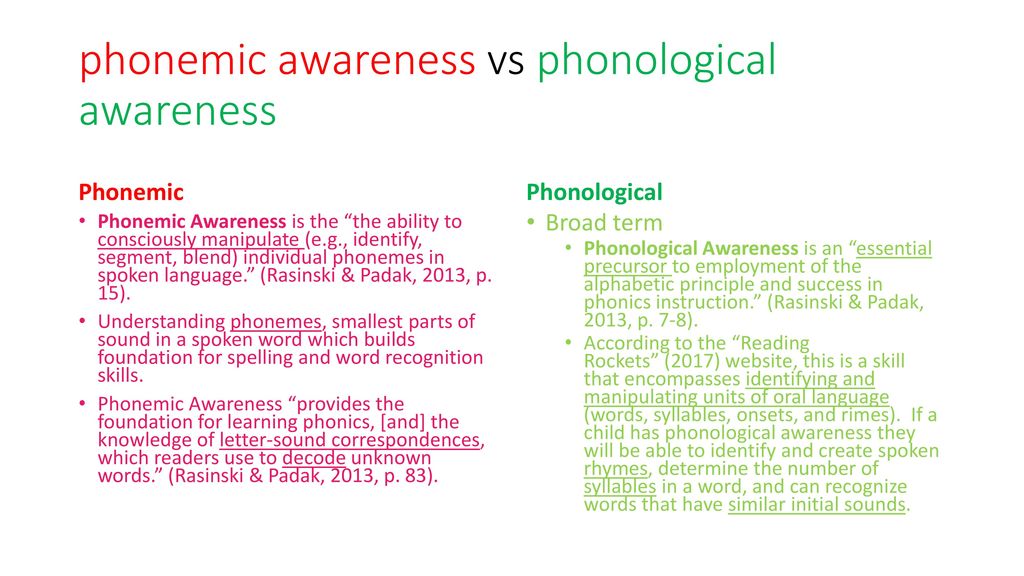

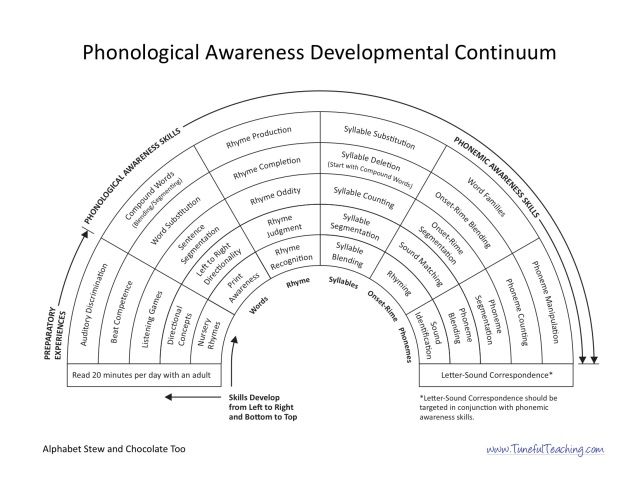

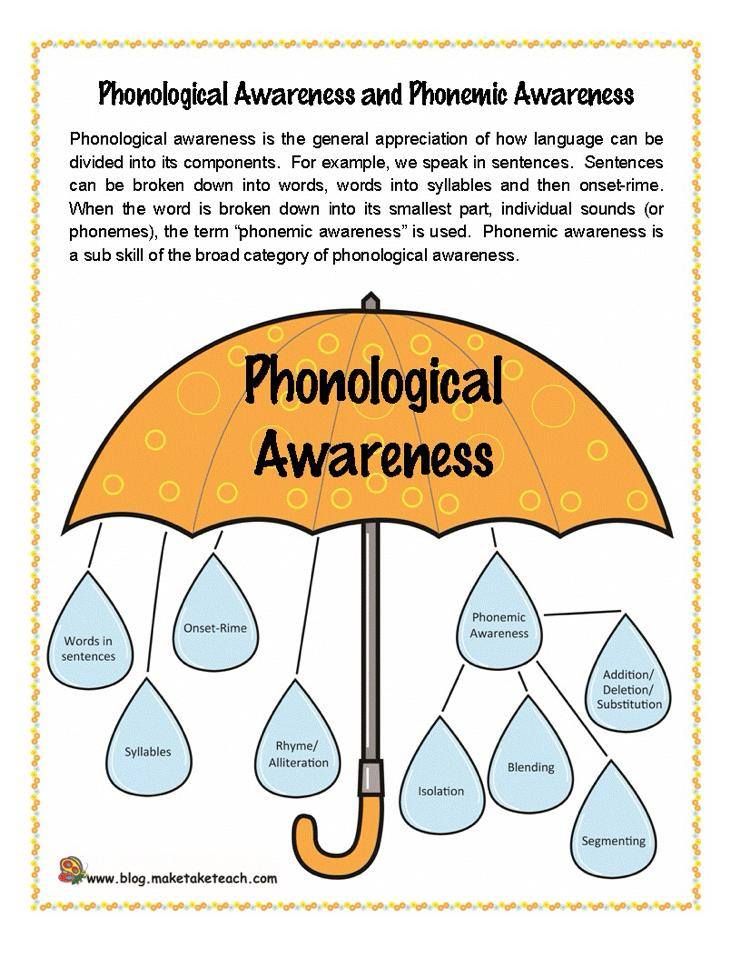

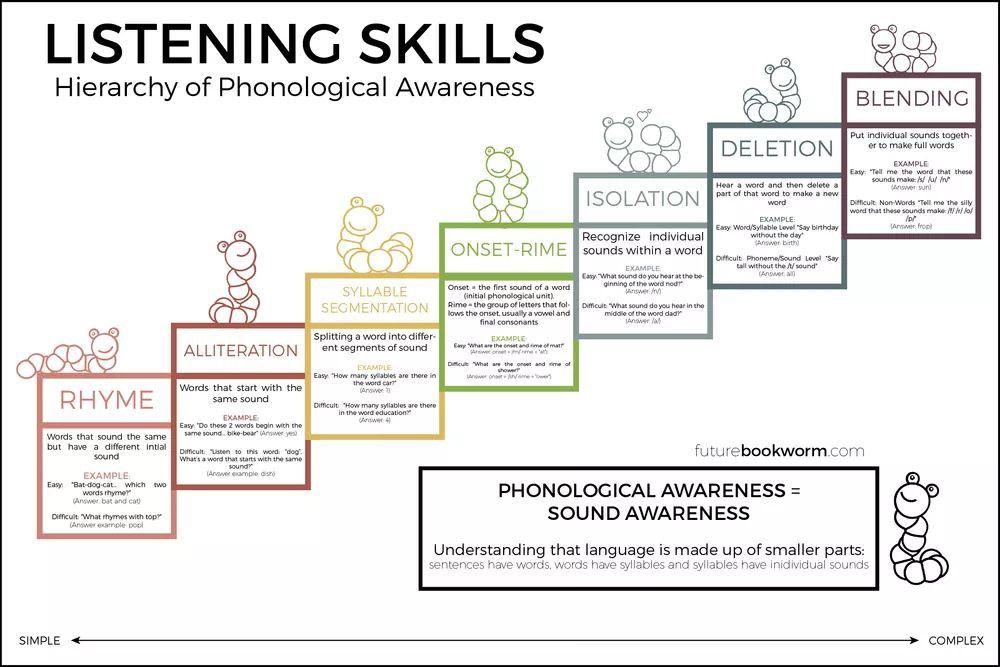

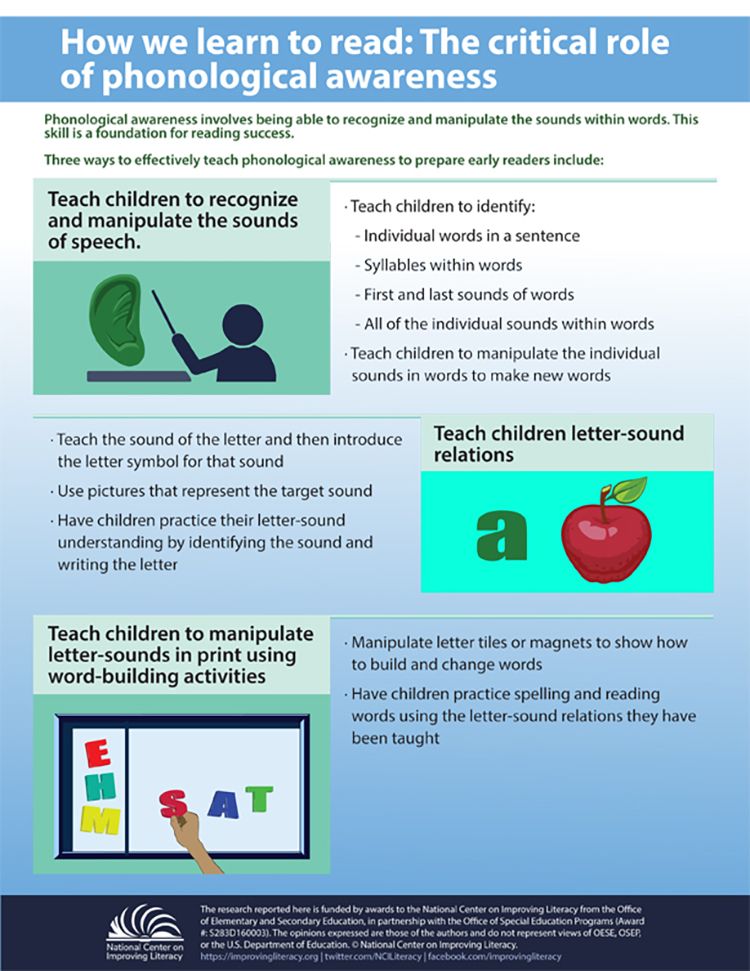

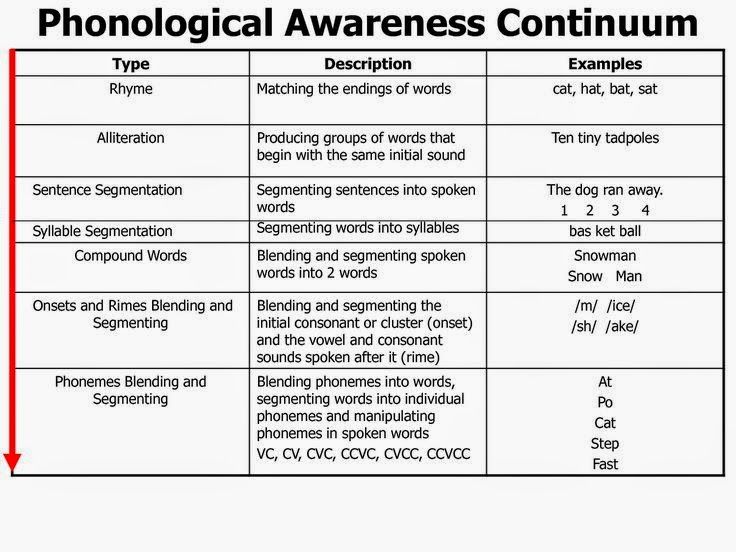

I like to think of Phonological Awareness as an umbrella term, with phonemic awareness as one of the skills that comes in under that umbrella. Phonological awareness includes:

● Rhyme

● Words

● Syllables

● Alliteration and Initial sounds

● Phonemes (Phonemic Awareness)

I will quote David Kilpatrick’s definitions of the differences between the two from his book, “Equipped for Reading Success”:

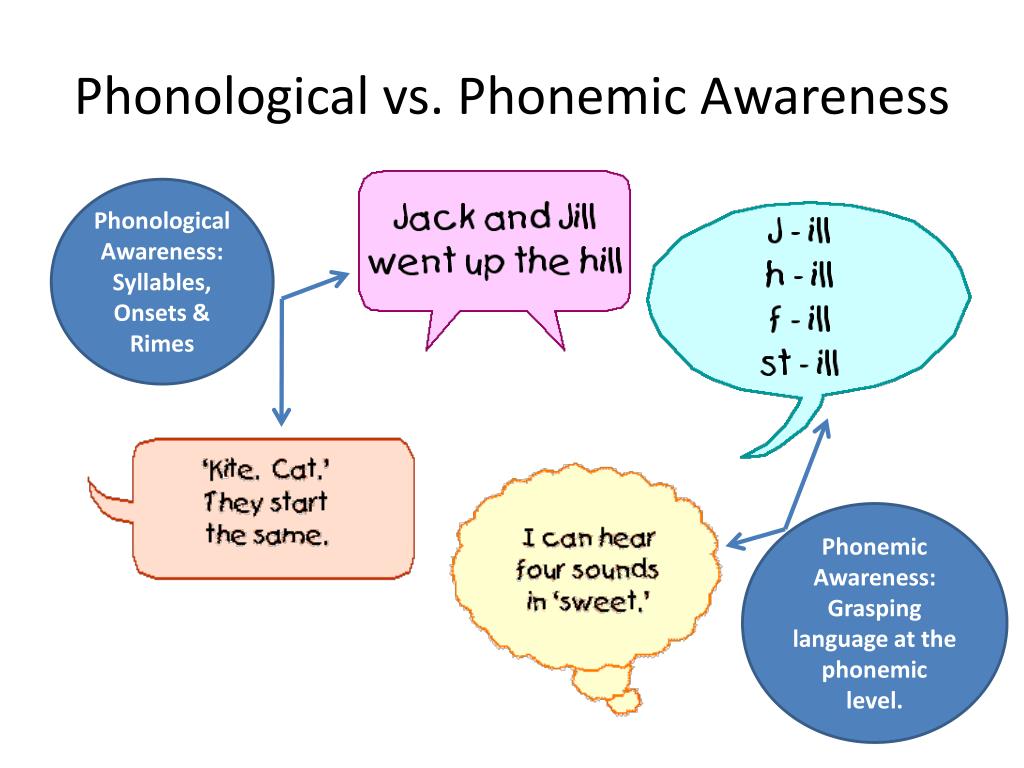

Phonological awareness: The ability to recognize and manipulate the sound properties of spoken words, such as syllables, initial sounds, rhyming parts, and phonemes.

Phonemic awareness: The ability to recognize and manipulate individual phonemes in spoken words.

Phonemic, or phoneme awareness is crucial to reading, and the other skills of phonological awareness, mentioned above, are its foundation. The order in which phonological awareness is developed is a complex subject, and I find myself tweaking it from time to time. The most important thing is to lay the foundation for phonemic awareness to be developed through rhyme, words, syllables, and alliteration and initial sound work. Later in this blog, I will talk about my current preferred order, along with some examples, but first we must define a phoneme.

The order in which phonological awareness is developed is a complex subject, and I find myself tweaking it from time to time. The most important thing is to lay the foundation for phonemic awareness to be developed through rhyme, words, syllables, and alliteration and initial sound work. Later in this blog, I will talk about my current preferred order, along with some examples, but first we must define a phoneme.

Phoneme comes from the Greek word, phonos, which means “sound” or “voice.” To quote David Kilpatrick again, “A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound in a spoken word.” Written letters represent the phonemes in our spoken language. Phonemes and letters are not the same; phonemes are the oral sounds while letters are a written representation of those sounds. It is really important that children understand that phonemes are the smallest parts of oral words, whereas letters are the smallest parts of written words.

It is worth repeating: Phonemic awareness is crucial to reading, and the other skills of phonological awareness are the foundation for phonemic awareness.

Now I will lay out my current order so this foundation can be developed. I will also mention the order in which I personally introduce phonemic awareness, once the foundation is in place, and I will discuss this in greater depth in part 2 of this blog.

Phonological Awareness

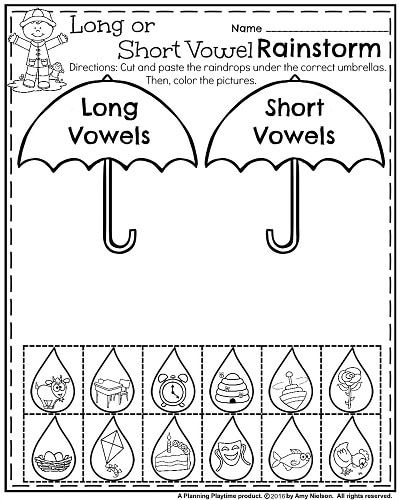

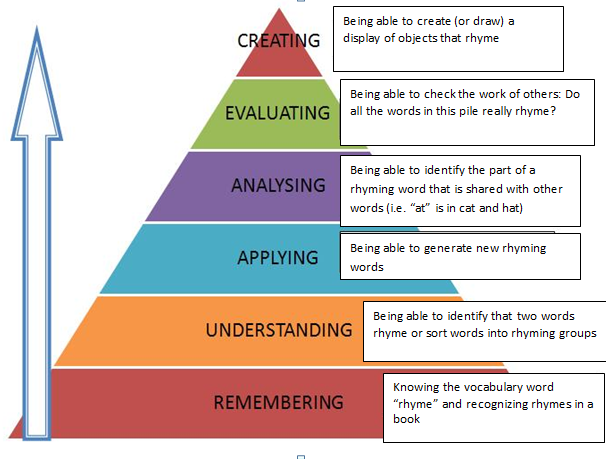

Rhyming: Words that have a similar sounding oral rime unit, for example “cat” and “mat,” “bear” and “flare.” Children can be asked if two words rhyme, or select from a group of three words, which one doesn’t rhyme. Lastly, they can be asked to supply words that rhyme with those being presented. If a child is experiencing difficulty, the last two concepts may be presented later, after some of the activities below.

Tip from a parent:

A parent recently shared with me that when her daughter was becoming distressed when trying to figure out whether two words rhymed. She hit on the idea of asking her daughter to think about whether her mouth moved in the same way as she said the end of each word, and also to feel her lips. These two tips really helped.

These two tips really helped.

Syllable Awareness: A syllable is a word, or a part of a word with one vowel sound. The children listen to multisyllable words, and are asked to count the syllables. They can clap or tap each syllable, or they could arrange tiles or cubes to represent each one. When describing syllables to children, you can call them chunks, or word parts. Example questions should be along the lines of:

● How many word-parts do you hear in “monkey?”

● How many syllables do you hear in “photograph?”

Blending of syllables: Children are asked to put two syllables together to form a word. For example, “Blend these two word parts together to make a word: win-dow.”

Syllable Segmentation: The parent, or teacher says a multisyllable word, and then asks the child to separate the word into its parts. For example, “Tell me the parts of this word: Doughnut (dough-nut), wonderful (won-der-ful).”

Segmentation of words in phrases and sentences: Before breaking sentences down into words, students should practice repeating single words, and then short phrases. Starting with three-word phrases or sentences and moving up to sentences with seven words, children are asked to repeat the sentence, and then figure out how many words are in that sentence. If they have difficulty, cubes or counters can be used as manipulatives.

Starting with three-word phrases or sentences and moving up to sentences with seven words, children are asked to repeat the sentence, and then figure out how many words are in that sentence. If they have difficulty, cubes or counters can be used as manipulatives.

For students who want to treat each syllable in multisyllable words as individual words, I use different colors or types of counters for syllables, to those which I use for words. This way, if the child has mistakenly selected word-counters for each syllable, it becomes a teaching opportunity, as the teacher or parent can go through the sentence again and discuss the multisyllable words. Then, together, they can exchange each group of syllable counters for a single word counter.

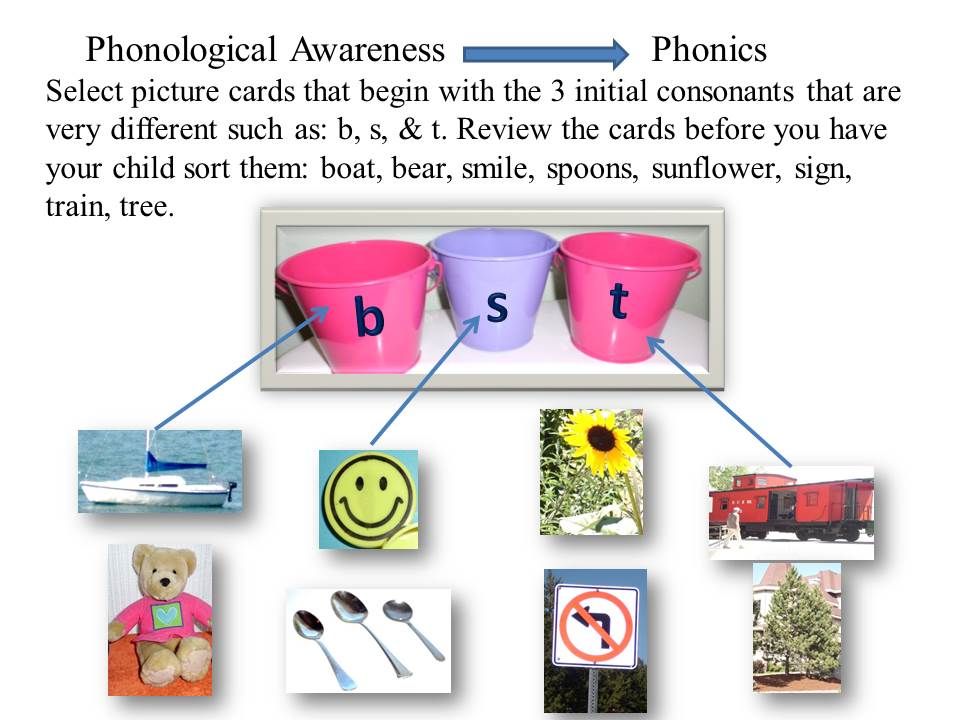

Alliteration and Initial sounds: This is word play that involves words sharing the same initial sound. An example would be, “Annie Apple and the ants.” Children are asked which words have same beginning sound. The teacher or parent can repeat the beginning sound after the child has identified the correct words.

Syllable Deletion: The teacher or parent starts by saying a compound word and asks the student to delete the initial and then the final syllable. For example, “Say cupcake without saying cup,” and, “Say sailboat without saying boat.” Then simple multisyllable words are introduced, and syllables are deleted. For example, “Say hamper without the ham.” The next stage is to delete syllables from three-syllable words, again starting with compound words. For example, “Say basketball without the ball.” From here a teacher can ask the student to remove syllables from the beginning of more complex words such as, “Say improvement without /im/,” and then on to removing the final syllable in a word such as clarinet: “Say clarinet without the /net/.”

Onset-Rime: This is where development charts of Phonological Awareness tell us phonemic awareness starts. I will define this term for you.

● Onset: The onset in a syllable is any consonant sounds that come before the vowel. In “cat,” the onset would be ‘c’ making a /k/ sound.

In “cat,” the onset would be ‘c’ making a /k/ sound.

● Rime: The rime in a syllable includes the vowel and any consonants that follow it. In “cat,” the rime would be /at/.

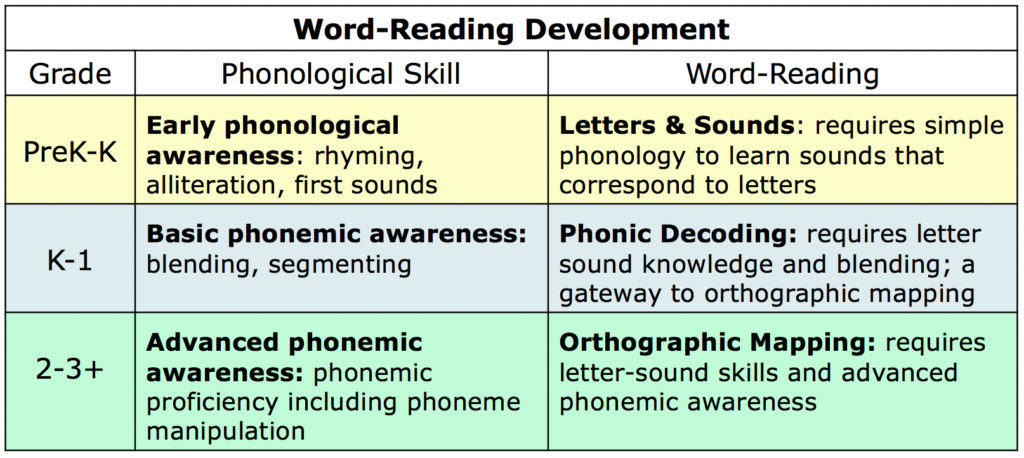

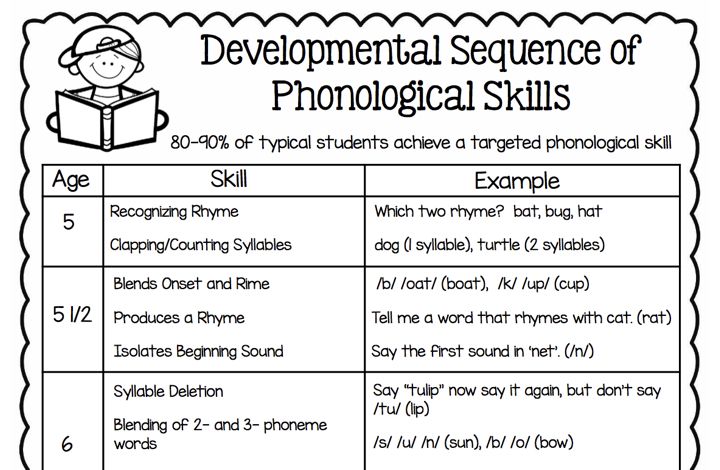

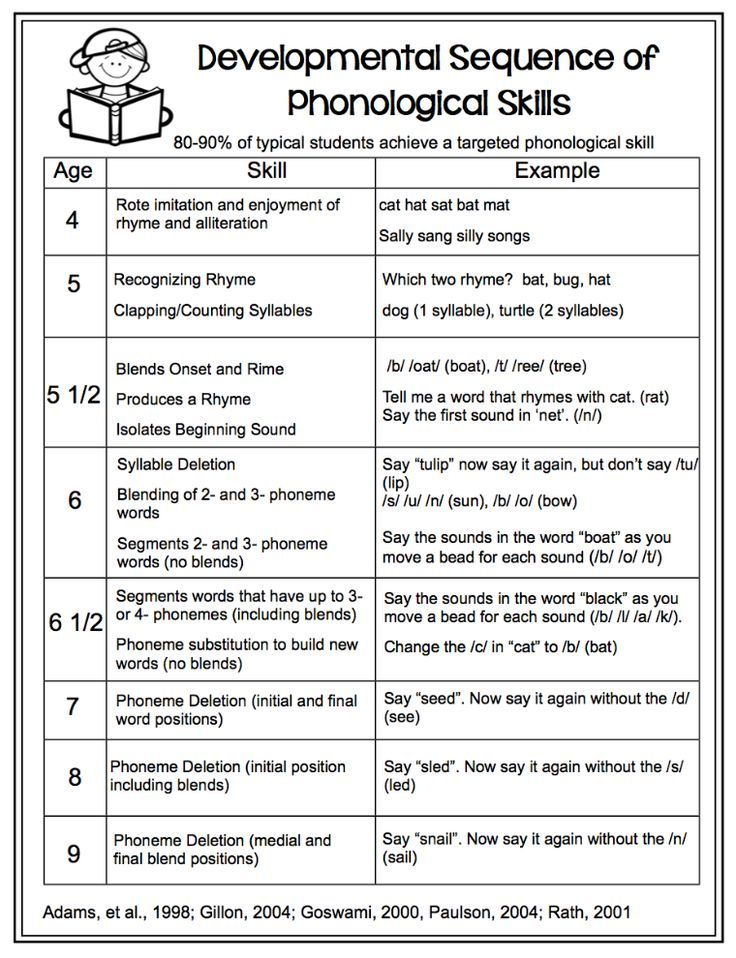

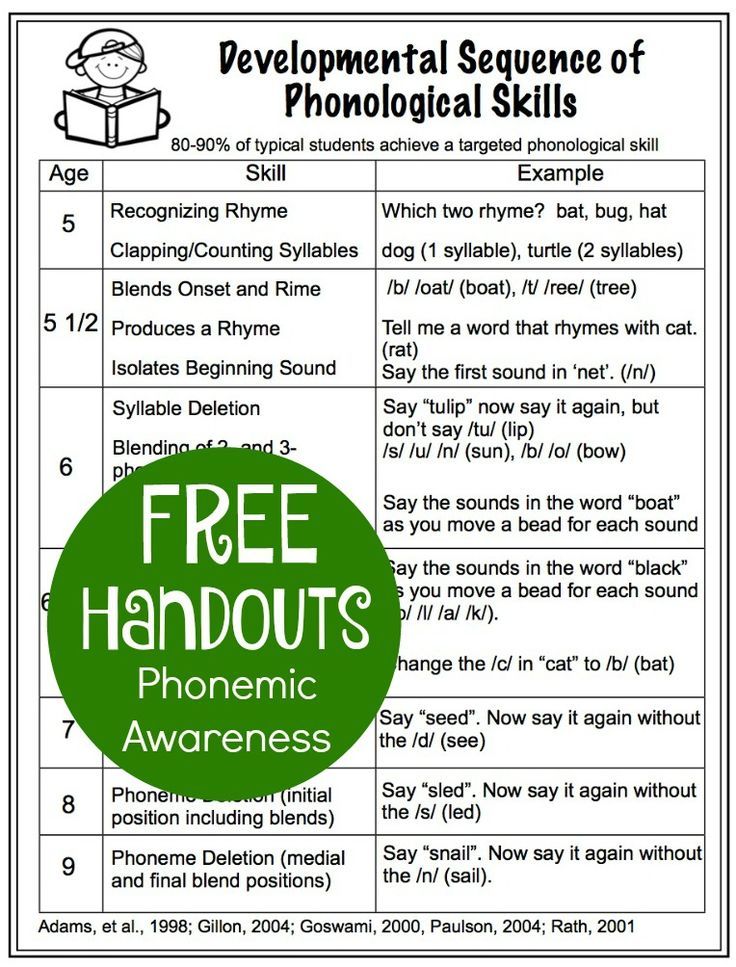

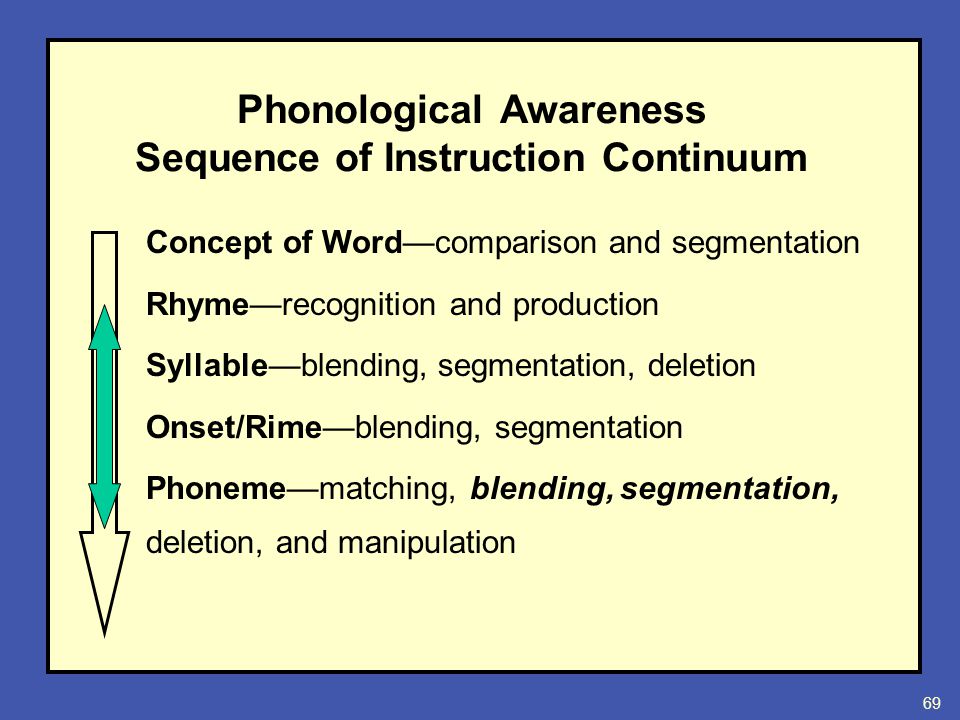

David Kilpatrick, in Equipped for Reading Success, separates his levels of phonological awareness into these levels:

1. Syllable Level (Also Alliteration and Rhyming): Pre-K to Kindergarten

2. Onset-Rime: Early Kindergarten to Second Grade

3. Phoneme Level: Basic, which is mid 1st Grade to Early 2nd Grade, and Advanced, which is late 1st Grade to 3rd Grade

He starts with a deletion of syllables, then works on onsets and rimes, and then moves on to substitutions of both.

His Phoneme Level covers manipulation of initial phonemes, then deletion of ending phonemes, onto substitution of phonemes, and finally working on reversal of phonemes. For teachers and parents not following this program, the following may be helpful, I will cover these in greater depth in part 2 of this blog.

1. Identification of phonemes

2. Blending of phonemes

3. Segmentation of phonemes

4. Deletion of phonemes

5. Addition of phonemes

6. Manipulation of phonemes

Part 2 will also include more resources, including assessment and curriculum materials for teaching phonological and phonemic awareness.

For further information about phonemic awareness, the Orton-Gillingham Online Academy offer a free webinar on this topic.

Sources:

1. David A.Kilpatrick, Ph.D. Equipped for Reading Success

2. Unlocking Literacy by Marcia K. Henry

3. Great Leaps Reading Grades K-2 by Kenneth U.Campbell

4. Great Leaps Language Growth Phonological Awareness and Language Activities by Kenneth U. Campbell.

Lorna Wooldridge is a dyslexia specialist tutor with over twenty-five years of experience and qualifications in the field of learning differences, from both the UK and USA. Lorna has a unique perspective on this condition as she has dyslexia, and her passion is to serve this community in any way she can.

Lorna has a unique perspective on this condition as she has dyslexia, and her passion is to serve this community in any way she can.

📖 Phonological Awareness, Speech Development, Chapter 11. Communication and Skill Development Disorders. Children's pathopsychology. Mash E. Page 87. Read online

At first, babies listen to the sounds of their parents' speech and soon begin to communicate using basic gestures and sounds. During their first year of life, they may learn a few words and even create new words to express their desires and emotions. After two years, language development is rapidly progressing, and their ability to coherently formulate their thoughts and express new concepts is the delight and admiration of parents. Adults play an important role in encouraging the development of a child's language skills by improving speech and enjoying children's expressions.

A language consists of phonemes that are basic sounds (such as plosives b, e or vowels and, e) and form the language. When a child constantly hears a particular phoneme, ear receptors stimulate the formation of appropriate connections and transmit them to the auditory part of the cerebral cortex. The formed perception map is a set of sounds similar to each other, which helps the child to recognize different phonemes. These cards form quickly; six-month-old babies of English-speaking parents already have auditory maps that differ from the auditory maps inherent, for example, in babies in Swedish families, which depends on the different activity of neurons for different sounds (Kuhl, 1995). By the first year of life, the cards are formed, and babies lose the ability to distinguish sounds that are not important for their native language.

When a child constantly hears a particular phoneme, ear receptors stimulate the formation of appropriate connections and transmit them to the auditory part of the cerebral cortex. The formed perception map is a set of sounds similar to each other, which helps the child to recognize different phonemes. These cards form quickly; six-month-old babies of English-speaking parents already have auditory maps that differ from the auditory maps inherent, for example, in babies in Swedish families, which depends on the different activity of neurons for different sounds (Kuhl, 1995). By the first year of life, the cards are formed, and babies lose the ability to distinguish sounds that are not important for their native language.

It is the rapid development of the perceptual map that causes difficulties in learning a second language after the first: the fact is that the connections in the brain are already formed, and the remaining neurons are almost unable to form new basic connections, say, for the Swedish language. When the described cycle is established, babies can make words out of sounds, and the more words they hear, the faster they learn the language. Sounds serve to strengthen and expand neural connections, which in turn ensures the formation of more words. Similar cortical circuits are formed as the basis for other activities, such as music. A young child who is learning to play a musical instrument may have neuronal circulation activated, which will favorably develop his spatial thinking and mathematical abilities (Hancock, 1996).

When the described cycle is established, babies can make words out of sounds, and the more words they hear, the faster they learn the language. Sounds serve to strengthen and expand neural connections, which in turn ensures the formation of more words. Similar cortical circuits are formed as the basis for other activities, such as music. A young child who is learning to play a musical instrument may have neuronal circulation activated, which will favorably develop his spatial thinking and mathematical abilities (Hancock, 1996).

Phonological awareness.

Not all children progress normally in their language development, some are very lagging behind, using mostly gestures or sounds to communicate, rather than speech. Others develop normally following verbal commands, but have difficulty finding words to express their thoughts clearly.

Psychology bookap

Although the development of speech is one of the main indicators of general intelligence, as well as the development of the school curriculum (Sattler, 1998), the difference in this indicator is in no way a sign of intellectual retardation or cognitive impairment in children. Rather, such deviations from the norm may indeed be only deviations and are accompanied by pronounced abilities in other areas. Albert Einstein, considered an intellectual genius, started talking late, stammering and making his parents think he was "not quite normal". Family tradition says that when a father asked the headmaster what profession he would advise his son to take, the answer was simple: “It does not matter, because he will never succeed in anything” (R. W. Clark, 1971, p. 10).

Rather, such deviations from the norm may indeed be only deviations and are accompanied by pronounced abilities in other areas. Albert Einstein, considered an intellectual genius, started talking late, stammering and making his parents think he was "not quite normal". Family tradition says that when a father asked the headmaster what profession he would advise his son to take, the answer was simple: “It does not matter, because he will never succeed in anything” (R. W. Clark, 1971, p. 10).

Because speech development is an indicator of overall mental development (Sattler, 1998), children with language delays or severe language delays are considered to be at risk. As is known, Albert Einstein's speech problems were precursors to his subsequent communication and learning disorders (Benasich, Curtiss & Tallal, 1993; B.A. Lewis, Freebarn & Taylor, 2000).

Phonology is the ability to memorize and store phonemes, as well as the rules for composing semantic compounds or words from sounds. The impairment of this ability is the main reason why most children and adults with communication and learning disabilities have language problems such as reading and writing.

The impairment of this ability is the main reason why most children and adults with communication and learning disabilities have language problems such as reading and writing.

A young child needs to realize that speech is divided into phonemes (English has 44, such as ba, ga, at and tr). Many children find it very difficult to understand that speech does not consist of individual phonemes that follow one another. Instead, the sounds are articulated at the same time as (overlapping) so that one can speak faster than if they were spoken consecutively (Liberman & Shankweiler, 1991).

By the age of seven, about 80% of children are able to break words and syllables into phonemes (Blachman, 1991), but there are those who cannot do this. These are children who have serious problems in mastering reading skills (B. A. Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 1994).

Early language problems become learning problems when they enter school as children have to learn to correlate spoken language with written language. Children who find it difficult to learn to read and write also find it difficult to learn the system of letters and sounds. These children cannot correctly pronounce the sounds in the syllables of words, which is called a lack of phonological awareness and is a harbinger of reading problems (Frost, 1998).

Children who find it difficult to learn to read and write also find it difficult to learn the system of letters and sounds. These children cannot correctly pronounce the sounds in the syllables of words, which is called a lack of phonological awareness and is a harbinger of reading problems (Frost, 1998).

Phonological awareness is a broad generalization that includes recognizing the relationships that exist between sounds and letters, determining rhythm and alliteration, and knowing that sounds can form different syllables in words. To determine the level of phonological awareness among primary school students, teachers ask them to rhyme words or rearrange sounds. For example, the teacher might say "cat" and ask the child to say the word without the first sound k, or say "home" and the child must say the word without m. the child pronounce these sounds together, adding them to the word "three".

While phonological awareness is a prerequisite for developing reading skills, it is also closely related to the development of expressive language (Edwards, Fourakis, Beckman, & Fox, 1999). In the process of reading, it is very difficult for those who experience significant difficulties in pronouncing sounds to differentiate phonemes, remember the names of ordinary objects and letters, as well as store phonological codes in short-term memory, recognize a phoneme and reproduce some speech sounds. For the most part, reading and comprehension depend on speed and the automatic ability to recognize individual words. Slow and inattentive children face very great difficulties in reading comprehension (Lyon, 1996).

In the process of reading, it is very difficult for those who experience significant difficulties in pronouncing sounds to differentiate phonemes, remember the names of ordinary objects and letters, as well as store phonological codes in short-term memory, recognize a phoneme and reproduce some speech sounds. For the most part, reading and comprehension depend on speed and the automatic ability to recognize individual words. Slow and inattentive children face very great difficulties in reading comprehension (Lyon, 1996).

Section summary.

- The development of speech is based on the innate ability and acquired capabilities to learn, store and reproduce the basic sounds in the language, it occurs very quickly, in early childhood.

- Deficiency in phonological awareness the ability to distinguish the sounds of a language is the main cause of communication disorders and impaired development of school skills.

Phonological games for preschoolers | Skyteach

3646

7

Before learning to swim, children get used to the water, learn to breathe correctly, and train to lie on the water. In the same way, before learning to read, a preparatory stage is needed - the child must learn to distinguish sounds and control them. This is called phonological awareness.

In the same way, before learning to read, a preparatory stage is needed - the child must learn to distinguish sounds and control them. This is called phonological awareness.

The development of phonological awareness includes the following steps:

- division of words in a sentence by ear;

- selection of rhyming words;

- distinguishing syllables in words;

- onset recognition and roman. Onset is the initial phoneme in a word, and rima is the sounds following the onset. For example, in the word dog d is onset, and og is rima;

- identification of phonemes in words;

- fusion and separation of phonemes.

I will tell you how to develop phonological awareness through games. The games from the selection are suitable for preschoolers, younger students, as well as for all students who have difficulty learning to read. Tasks are easily adapted for group and individual lessons.

Candy Count

This game teaches you how to count the number of words in a sentence.

You will need a candy wrapper or a printed wrapper and counters such as fruit puree lids or large buttons. Say a sentence and put as many candies in the package as there are words in the sentence. Then the students listen to the sentences and lay out the sweets themselves.

The student collected three "candies" after listening to the sentence twice: « Mommy likes pickles »Sample sentences:

- Children play.

- Read a book.

- Boys like cars.

- He likes dancing.

- Mary doesn't live here.

Hungry Spider

We train the ability to find rhyming words.

You will need a spider web drawn on a piece of paper, cards with flowers and pictures of rhyming words: pink/sink, red/bread, black/sack, green/bean, brown/clown, blue/shoe.

Attach the web to a board or wall, and arrange the cards with the pictures of the objects around the room. Read the rhyme aloud, filling in the gap with the first words of the pair:

Read the rhyme aloud, filling in the gap with the first words of the pair:

I'm A Hungry Spider (based on the tune “I'm a Little Teapot”)

I'm a hungry spider, in my web.

Looking for treats that rhyme with _____.

Can you find me a tasty treat?

Put it in my web. Let's eat!

Children must find an object with a rhyming name and fix it on the web, for example, with a magnet. For young children, make cobwebs on the floor with masking tape or masking tape.

A web of scotch tape on the floor on which a child puts real objects and Lego partsSource: Rhyming Activity: I’m a Hungry Spider

Pick a rhyming pair

Task to find consonance in words - rhymes.

You will need cards with rhyming words or real objects with rhyming names. The words must be familiar or learned beforehand. Each child receives a card, walks around the classroom and says the word out loud until they find a rhyme. If the class is large, then the children match in pairs.

If the class is large, then the children match in pairs.

Possible word pairs: flag/bag, cake/snake, duck/truck, star/car, boat/goat, bug/rug, pear/bear, log/frog. The number of words depends on the level of knowledge of the child.

Rhyming word pairs (left to right): flag/bag, cake/snake, duck/truck, star/car, boat/goat, bug/rug, pear/bear, log/frog. Figurines are taken, including from Lego and Kinder surprisesCalling animals

Task for distinguishing syllables.

You will need animal figurines, eg bull, donkey, camel, gorilla, elephant. We hide the animals behind our backs and invite the child to call them in turn, dividing the words into syllables. For example, ca-mel, e-le-phant. Clapping hands helps to clearly separate syllables.

In my lessons the animals usually miss their flight: This is the final call for passenger Donkey. Let's call him together. Don key! don key! Hurry up.

A child calls late passengers on board by syllablesMagic pockets

We practice the ability to distinguish syllables in words and count them.

You will need three or four pockets and a stack of word cards. Say the word in syllables - students will count the syllables and put the card in the appropriate pocket.

The student sorted into pockets the words on the cards Doman with one, two and three syllablesPop-it game

Learning to identify phonemes.

The teacher shows the picture and says the word and then breaks it down into phonemes, eg b-u-s . During the pronunciation of sounds, children push the appropriate number of buttons in the pop-it toy. If pop-it is not at hand, then the number of phonemes can be slammed.

A child pushed three pop-it buttons after hearing the word busPuppet conversation

Task to merge phonemes into words.

Put on a glove puppet and say that it speaks puppet language - this will be a temporary name for English. Ask the children to translate what the toy says. For example:

Teacher (doll voice): H-e-l-o.