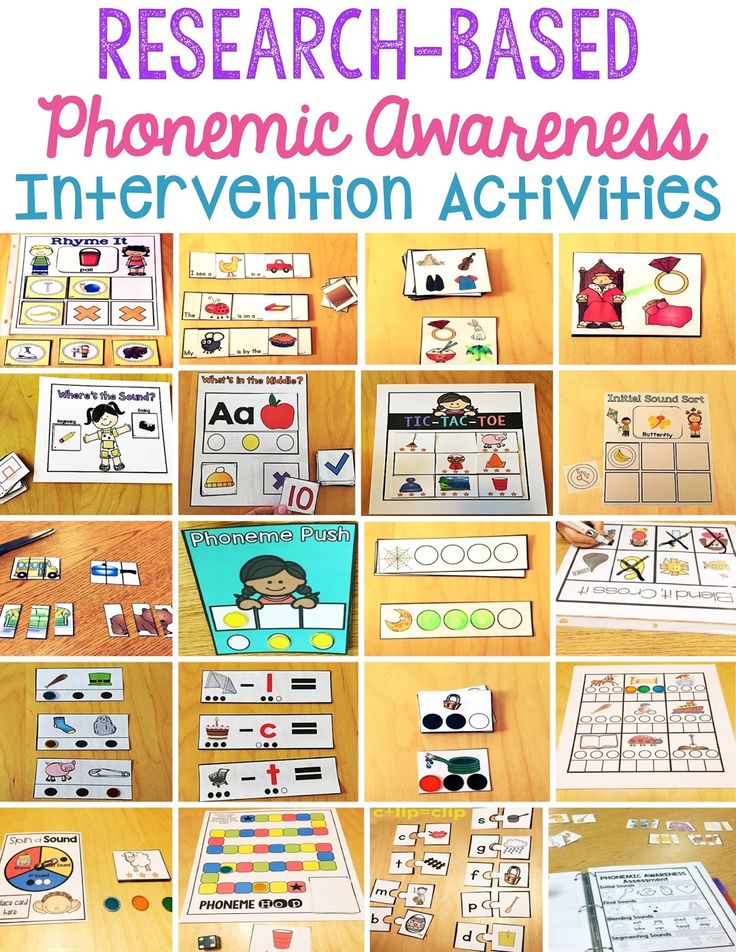

Activities for phonological awareness

Phonemic Awareness Activities For A Strong Reading Foundation

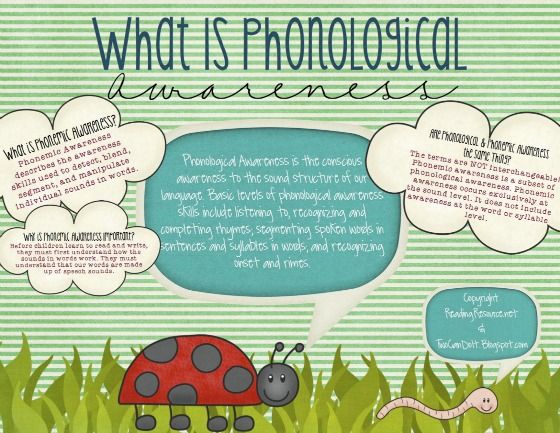

What Is Phonemic Awareness?

Phonemic awareness is a concept that deals with identifying and manipulating single sounds in words, known as “phonemes”.

A phoneme is the smallest possible unit of sound in a language. Phonemes blend together to form words, and every word we use is made up of a combination of them.

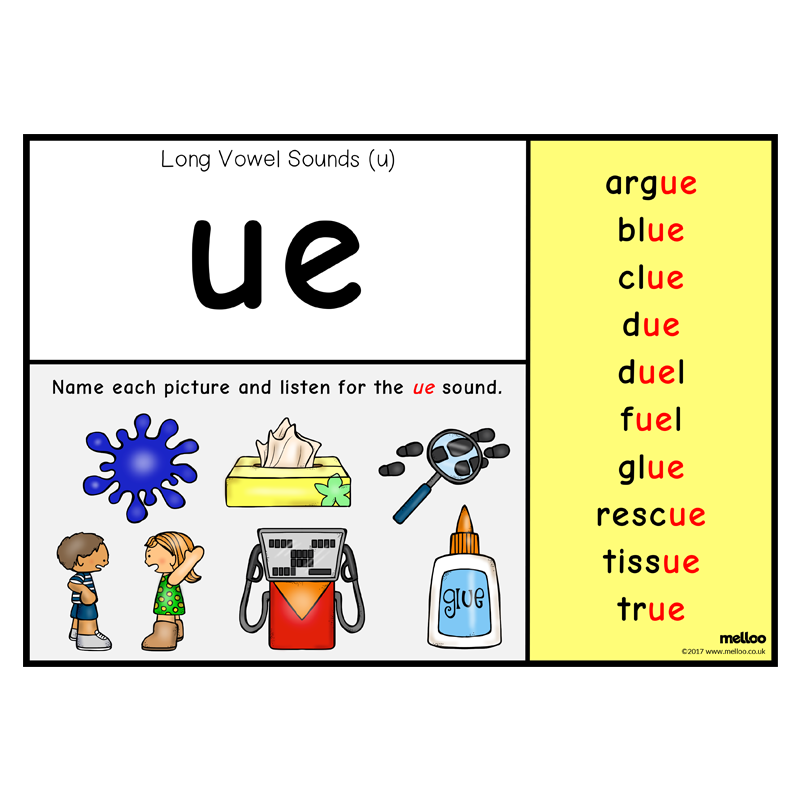

Even though there are only 26 letters in the alphabet, there are 44 unique phonemes in English (and 250 different ways to spell them!). Fortunately, especially in words beginners need to read, most of the sounds are linked to one main letter.

If you change any letter in a word, though, you change everything! For example, take the word “rag.” If the first sound, or phoneme, of the word is changed to a “b,” then you’re left with an entirely new word (bag) with its own distinct meaning.

So when you think about it, building phonemic awareness is really about your child playing around with sounds and then switching sounds in words. It’s like a Dr. Seuss book come to life!

Why Is Phonemic Awareness Important?

It’s hard to learn how to read if you can’t match sounds to letters. That’s where phonemic awareness comes in.

Kids are often asked to “sound out” words they don’t recognize or understand. A firm grasp of phonemic awareness is the backbone of this technique!

Understanding how to break down unfamiliar words into individual phonemes can be an incredible, powerful tool for your child to use on their learning journey.

Phonemic awareness skills can also help build your child’s confidence and familiarity with the sounds and letters they are trying to read. The more comfortable they are with letter sounds the better prepared they will be for a lifetime of learning and reading!

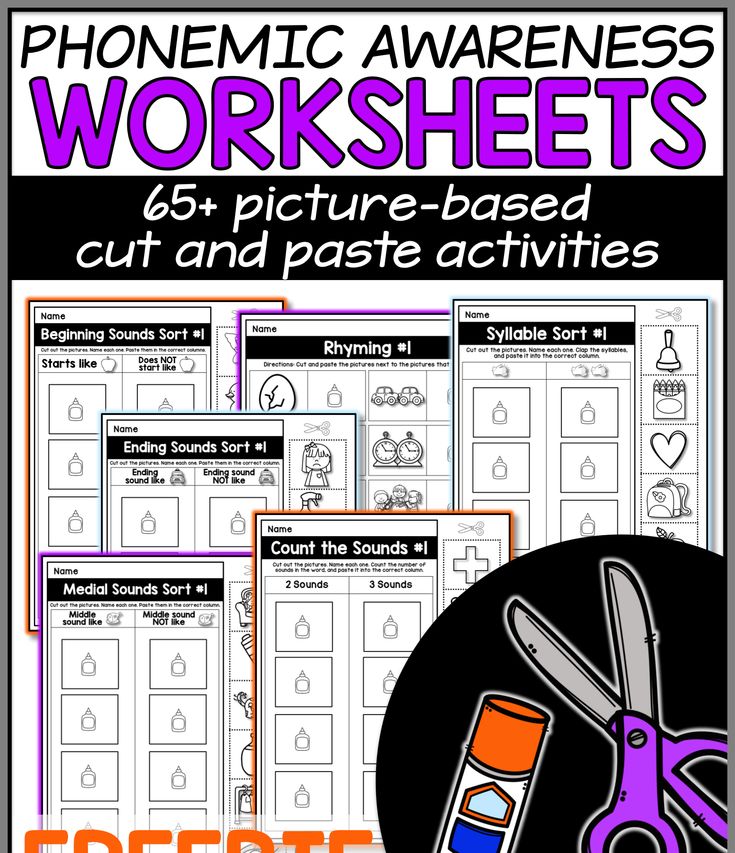

Fun And Easy Phonemic Awareness Activities

Now that we’ve discussed what phonemic awareness is and why it’s important, we’ll walk you through some fun and easy activities you can use to help develop your child’s phonemic awareness skills.

Guess-That-Word

If you’d like to give this activity a go, lay out a few items or pictures in front of your child. Aim to use familiar objects that they can easily name.

Let them know you’ll be using “snail talk” or “slow-motion” talk, meaning you will be announcing the names of the items in a funny voice. Their goal is to guess the name of the item or picture in question before you finish saying the word.

For example, if there’s a picture of a cat in front of your child, drag out the C, A, and T sounds as long as you can. Your child can jump in anytime and shout the word of the object as loudly as they can!

This game works on blending phonemes, an essential part of phonemic awareness. The game helps encourage children to pay attention to the individual sounds that make up words.

Mystery Bag

Those little plastic letter magnets that are probably hanging out on your fridge will come in handy for this one!

If you choose to do this activity, you’ll need a spare box or paper bag. Place three plastic letters that can be used to make an easy-to-sound-out word (pat or cat, for example) inside the bag.

Place three plastic letters that can be used to make an easy-to-sound-out word (pat or cat, for example) inside the bag.

Suggest your child pull out one letter at a time. Ask them what sound each letter makes. For younger children, you can place the letters together to spell a word and sound it out for them. Then let them copy you.

You can ask older children to try to make a word on their own. If they make tap instead of pat that’s fine, of course! With more advanced readers, also consider adding more letters to make longer words.

Additionally, you can try letter swapping or letter deletion. Your child makes slip but what happens when you “steal” the “s” or the “l”? This kind of letter change is challenging but is also excellent practice!

Finally, you can also put lots of letters in the bag and then pull out a few and see if you can make a real word, a nonsense word, or (lacking a vowel) no word at all.

The mystery of the Mystery Bag is how versatile it is!

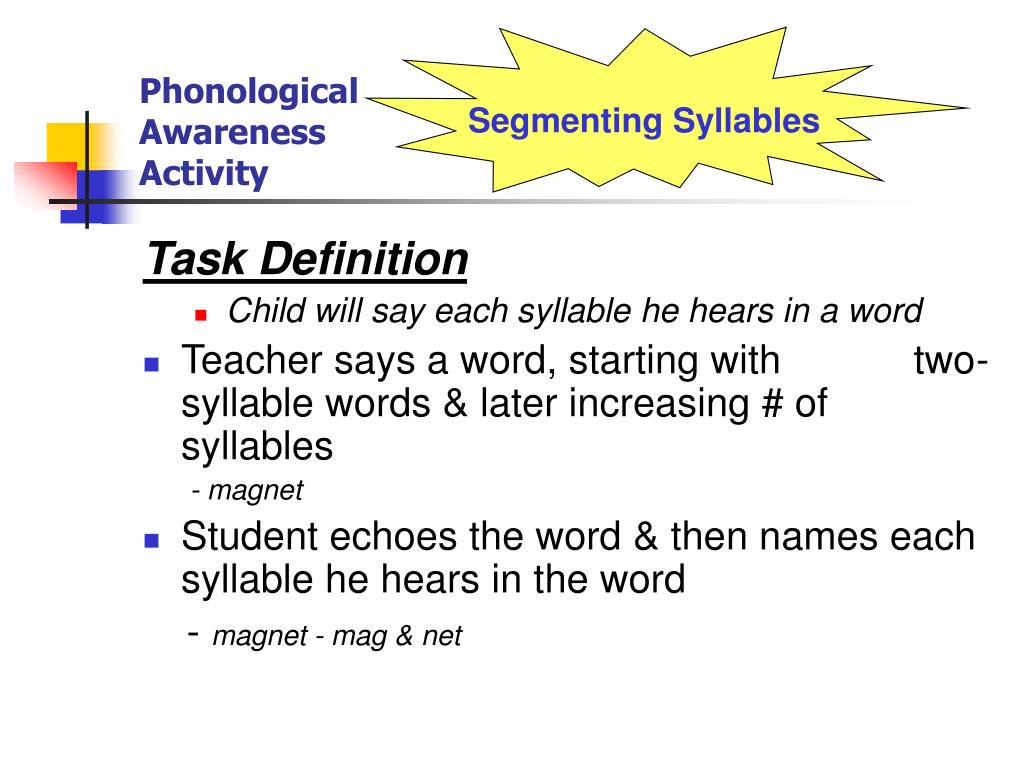

Clapping It Out

If your child loves to sing, this might be the activity for them!

You can sing any song or nursery rhyme. Simply have your child clap with the different syllables. Make sure you encourage them to clap loudly and enthusiastically for a fun learning experience!

Simply have your child clap with the different syllables. Make sure you encourage them to clap loudly and enthusiastically for a fun learning experience!

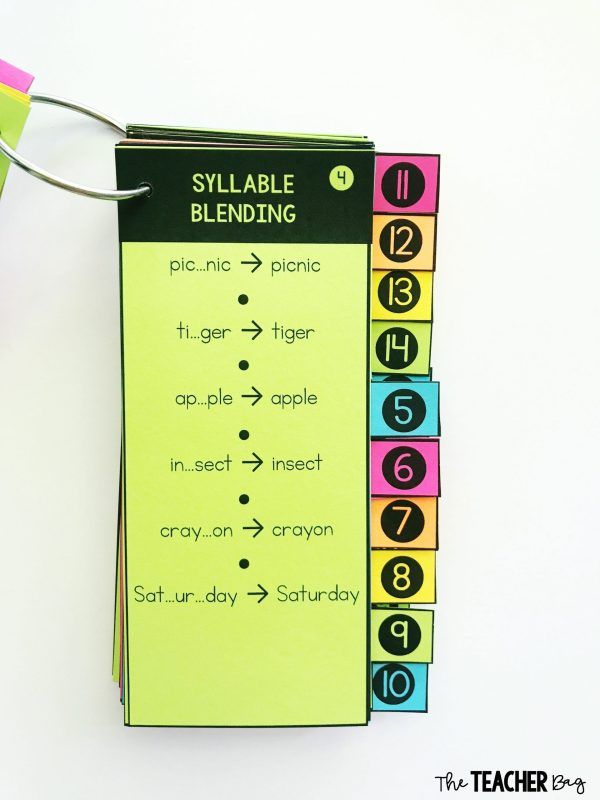

This activity is great for helping your child with their syllable awareness as well as their segmentation skills.

Make Some Noise!

If you’d like to explore this activity with your child, grab a few things from around the house that make a lot of noise. Whistles, pots and pans, bells, or bubble wrap are all great options.

Instruct your child to close their eyes (no peeking!) and listen to the sound you make. Once the sound is over and they think they know what caused it, they can take a guess.

Encourage them to give their answer in full sentences (“The sound I heard was a door opening.”).

After your child is able to correctly identify several individual sounds, you can mix things up by adding more noises one after another. For example, if you close a noisy door, ring a bell, then delicately tap a glass cup with a fork, your child would try to identify all three sounds.

Although this game does not deal explicitly with letter sounds, it works on an extremely important skill — listening!

By helping your child practice their detailed listening skills, you can help them engage in more focused ways when they are listening and playing with word sounds.

I-Spy With Words

Another fun way to engage phonemic awareness skills is by playing the game I-Spy, but instead of colors, play with sounds. Plus, it’s mobile; you can take this game anywhere, so it’s perfect for busy families on the go!

You can say, “I spy with my little eye something that starts with the /a/ sound . . .” and wait for your child to shout out something they see that begins with that sound.

This helps them with focusing and identifying the initial letter sound in words, an important building block for strong reading as they grow.

Rhyme Matching Game

If you want to try this activity, print out pictures of common items that rhyme. For example, chair/bear, rat/mat, and so on.

Your child will try to match the pictures to make rhyming pairs. This activity could take some getting used to for your child, but patience and practice are on your side!

If you find that your young learner needs a little bit more exposure to rhymes in order to understand how to match up the pictures, don’t be afraid to break it down for them.

You can tell them that rhymes are words that sound the same at the end. If it seems helpful, you can sit with your child and brainstorm rhyming words with them. Having you walk them through it step-by-step could be the extra support they need!

Make Your Own Rhyme

We mentioned that all of these phonemic awareness activities may make you feel like you’re living inside a Dr. Seuss book. But your child will love becoming their very own tongue-twisting, silly master of rhyming!

Dr. Seuss makes up all kinds of words in his books in order to create rhymes. Your child can do the very same thing (and learn a lot from it!).

You can get them started by providing them with a funny example. Something like, “There’s a noodle in my schmoodle.” Encourage them to come up with their own funny rhyme!

Drawing A Phonetic Alphabet

If you feel like your child needs to focus specifically on the phonetic sounds our alphabet makes, this might be a great exercise to choose.

You can work with your child to draw animals that make the same sounds as alphabetic letters.

For example, draw a big, winding snake in the shape of an “s.” Since snakes hiss, they’re a wonderful representation of the sss sound.

Another option could be a buzzing bee. When bee’s fly near your ear, they make a loud “buzzz-zzz,” sound. You could help your child draw a bee flying across the pattern, with a dashed line in the shape of a “z” to show their path!

Feel free to get creative, colorful, and fun here. This will help your child hone in on their isolation skills, as well as help them learn to pay attention to their phonemes!

Find The Best Phonemic Awareness Activities For Your Child

We know your child is unique. Which learning activities they respond to best might be slightly different from those a child in their class or the kid next door responds to.

Which learning activities they respond to best might be slightly different from those a child in their class or the kid next door responds to.

This is normal! Phonemic awareness activities are all about what helps your child learn in the most fun, effective, and easiest way possible.

We hope some of these suggestions gave you creative, new ideas for working on phonemic awareness in your home. If you ever find yourself wanting to explore more ideas, try our learning quiz to find more options that are just right for your child!

No matter which of these phonemic awareness activities you choose, your child is on their way to a happy, lifelong love of learning. We’re so excited to be on this journey with you!

Author

Phonological and Phonemic Awareness: Activities for Your Kindergartener

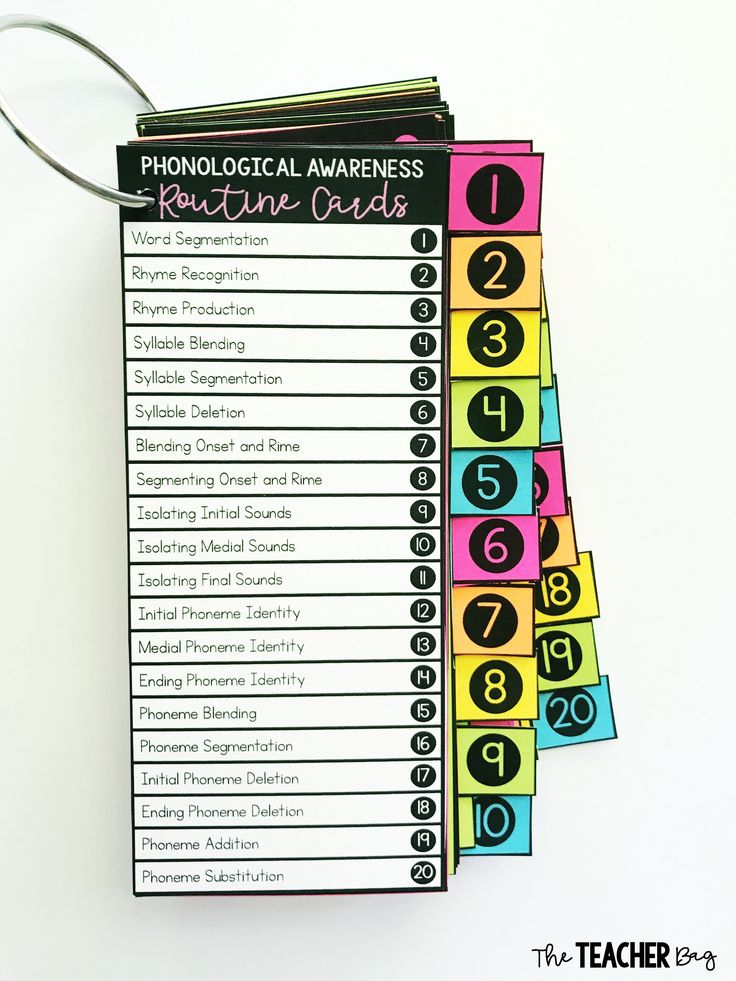

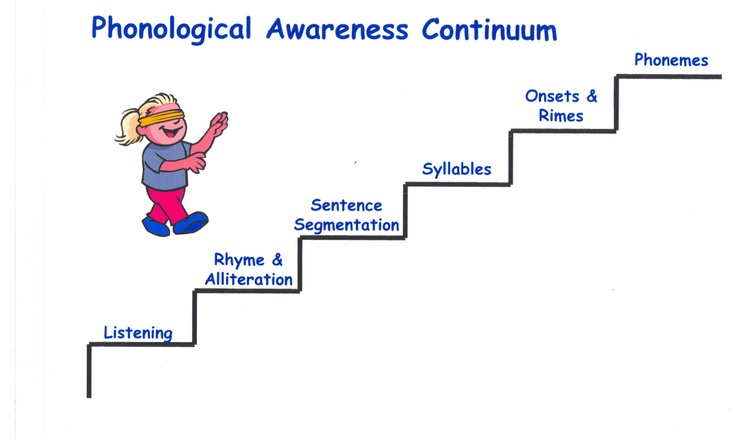

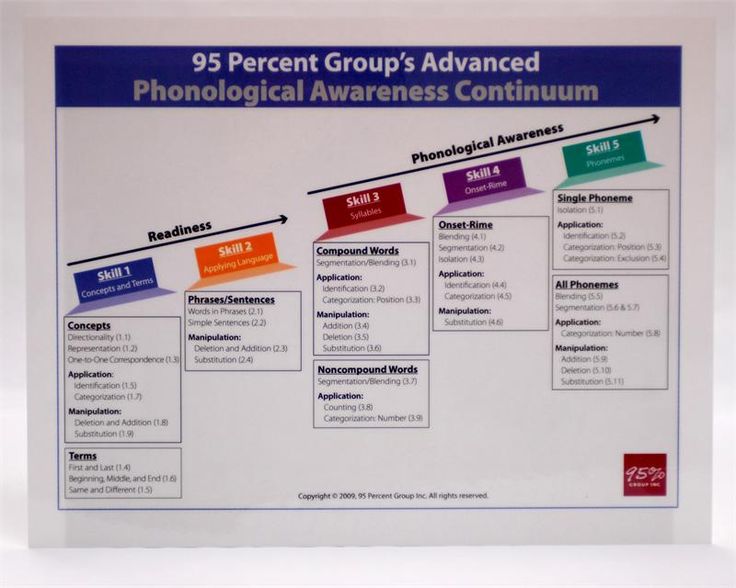

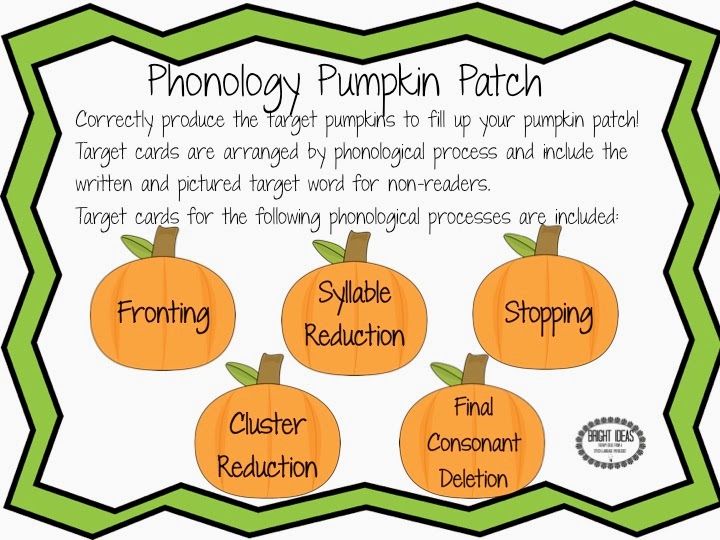

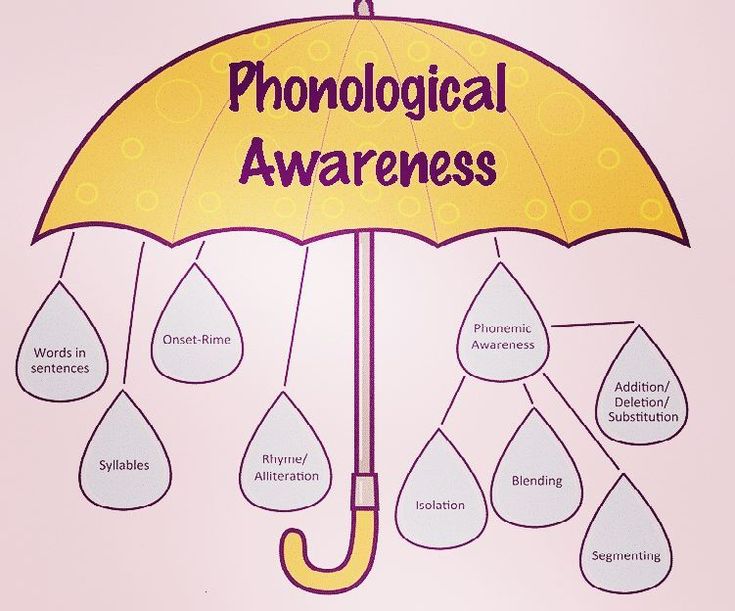

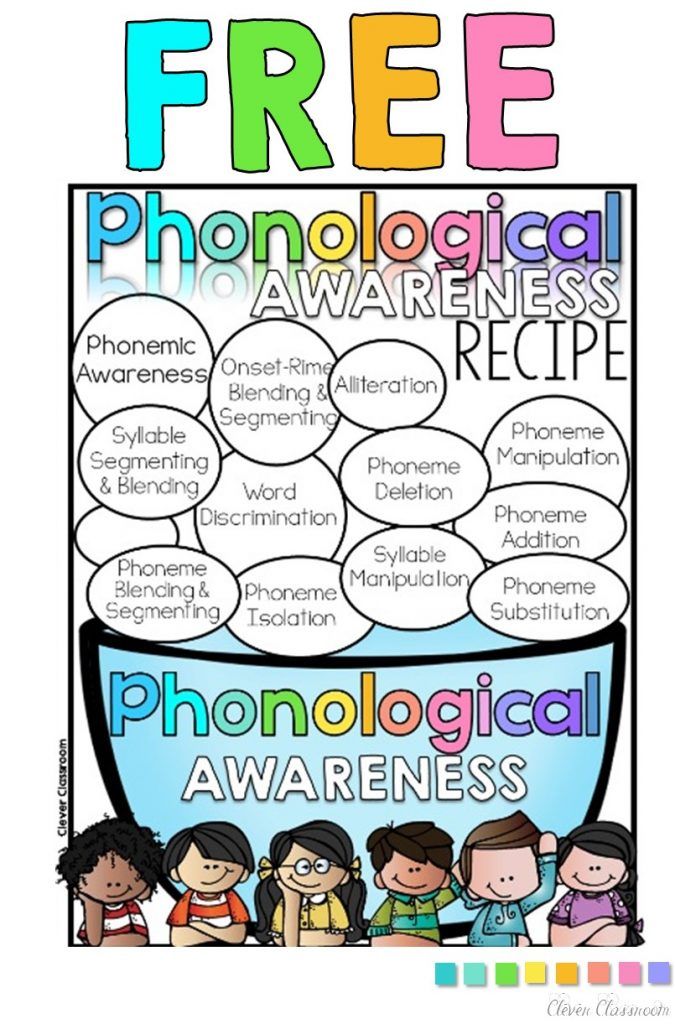

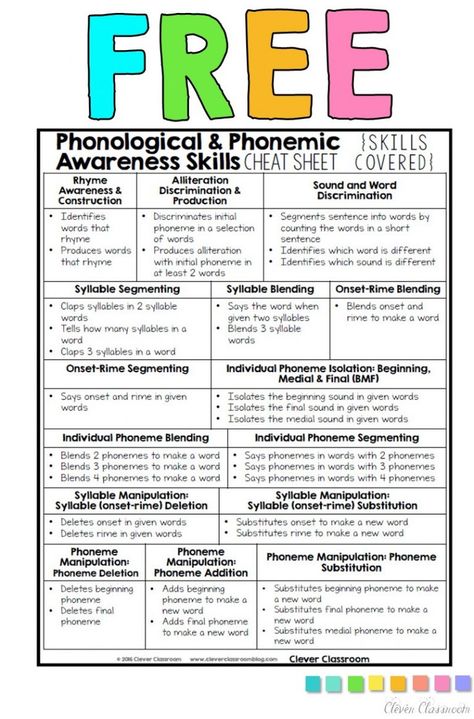

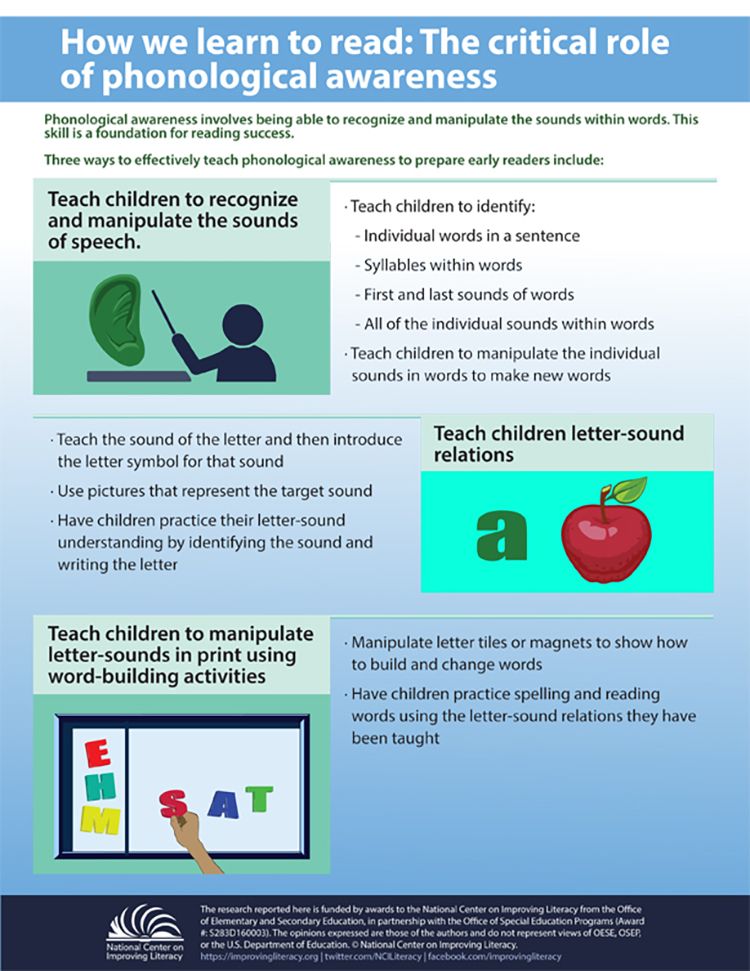

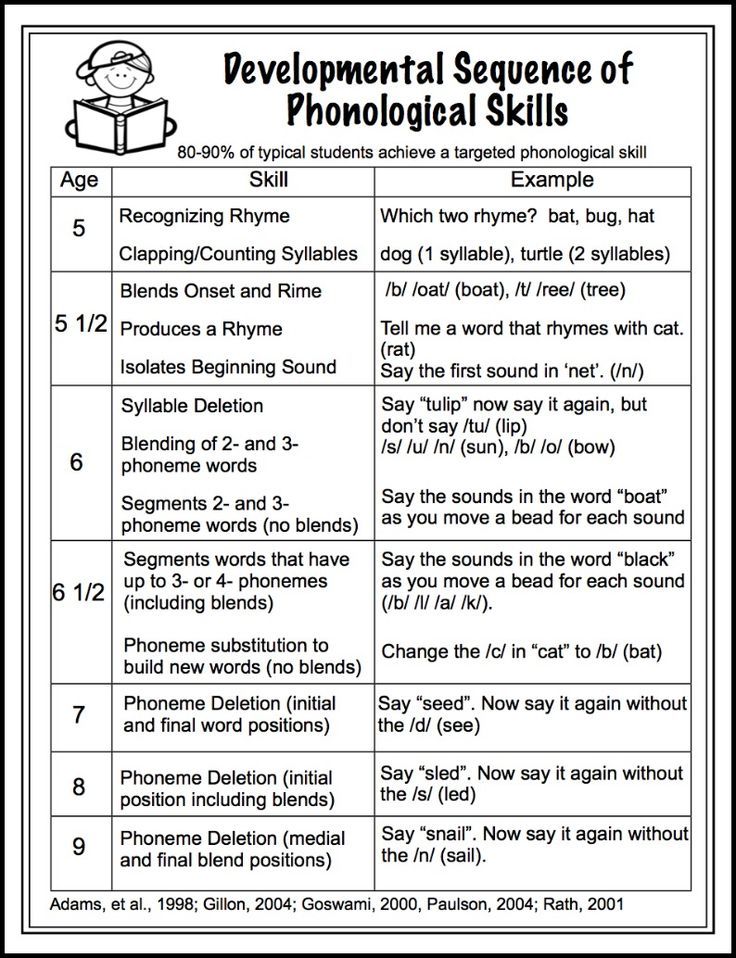

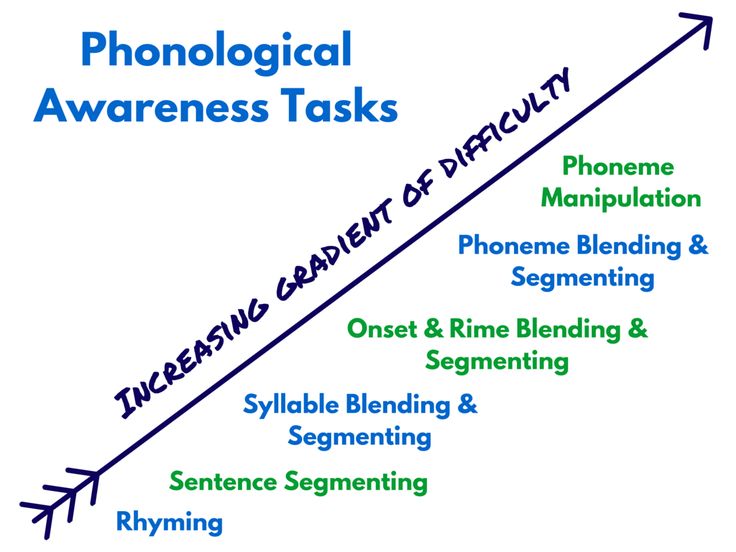

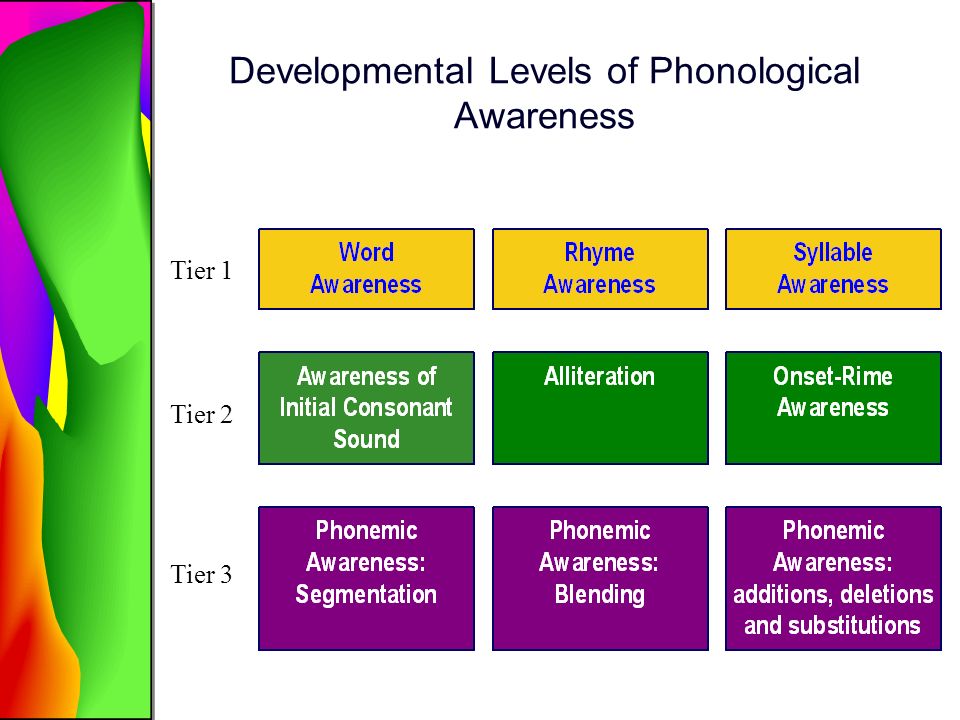

That's a complicated sounding term, but it's meaning is simple: the ability to hear, recognize, and play with the sounds in spoken language. Phonological awareness is really a group of skills that include a child's ability to:

Phonological awareness is really a group of skills that include a child's ability to:

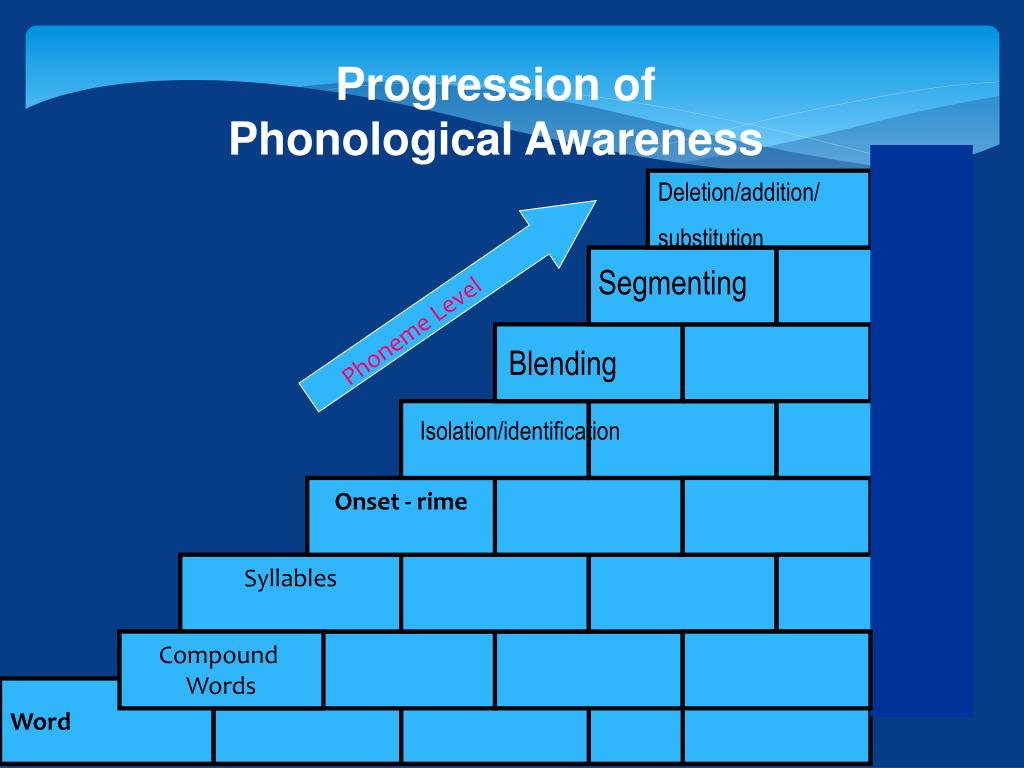

The most sophisticated phonological awareness skill (and the last to develop) is called phonemic awareness — the ability to hear, recognize, and play with the individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. When playing with the sounds in word, children learn to:

Strong phonemic awareness is one of the strongest predictors of later reading success. Children who struggle with reading, including kids with dyslexia, often have trouble with phonemic awareness, but with the right kind of instruction they can be successful. Learn some of the warning signs for dyslexia in this article, Clues to Dyslexia in Early Childhood.

Parents can make a big difference in helping their children become readers by practicing these pre-reading oral skills at home. Try some of the simple rhyming and word sound games described here.

Why phonemic awareness is the key to learning how to read

This video is from Home Reading Helper, a resource for parents to elevate children’s reading at home provided by Read Charlotte. Find more video, parent activities, printables, and other resources at Home Reading Helper.

Find more video, parent activities, printables, and other resources at Home Reading Helper.

Try these speech sound activities at home

Rhyme time

“I am thinking of an animal that rhymes with big. What's the animal?” Answer: pig. What else rhymes with big? (dig, fig, wig)

Road trip rhymes

While you're out driving in the car, spot something out the window and ask your child, "what rhymes with tree or car or shop?" Then switch roles and have your child spot something and ask you for a rhyme. This can turn into a game of nonsense rhymes ("What rhymes with tree stump?") but that's great for practicing sounds, too!

Word families

Word families are sets of words that rhyme. Start to build your family by giving your child the first word, for example, cat. Then ask your child to name all the "kids" in the cat family, such as: bat, fat, sat, rat, pat, mat, hat, flat. This will help your child hear patterns in words.

Start to build your family by giving your child the first word, for example, cat. Then ask your child to name all the "kids" in the cat family, such as: bat, fat, sat, rat, pat, mat, hat, flat. This will help your child hear patterns in words.

Silly tongue twisters

Sing songs and say silly tongue twisters. These help your child become sensitive to the sounds in words.

Tongue ticklers

Alliteration or "tongue ticklers" — where the sound you're focusing on is repeated over and over again — can be a fun way to provide practice with a speech sound. Try these:

- For M: Miss Mouse makes marvelous meatballs!

- For S: Silly Sally sings songs about snakes and snails.

- For F: Freddy finds fireflies with a flashlight.

Syllable shopping

While at the grocery store, have your child tell you the syllables in different food names. Have them hold up a finger for each word part. Eggplant = egg-plant, two syllables. Pineapple = pine-ap-ple, three syllables. Show your child the sign for each and ask her to say the word.

Eggplant = egg-plant, two syllables. Pineapple = pine-ap-ple, three syllables. Show your child the sign for each and ask her to say the word.

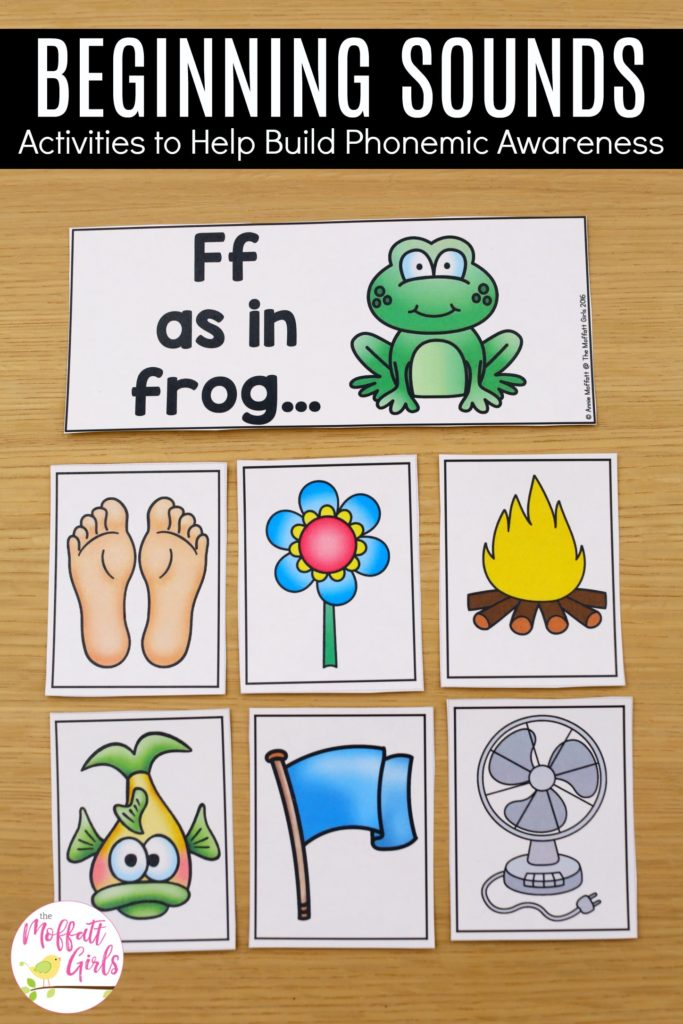

"I spy" first sounds

Practice beginning sounds with this simple "I spy" game at home, on a walk, or at the grocery store. Choose words with distinctive, easy-to-hear beginning sounds. For example, if you're in the bathroom you can say, “I spy something red that starts with the "s" ssss sound (soap).”

Sound scavenger hunt

Choose a letter sound, then have your child find things around your house that start with the same sound. “Can you find something in our house that starts with the letter “p” pppppp sound? Picture, pencil, pear”

Which letter sounds do I teach first?

Reading expert Linda Farrell recommends that you begin with teaching the letter names, and then focus on the letter sounds that are closest to their letter names (such as /v/). And here's a great tip for teaching the trickier letter name–letter sound combinations — use arm motions. In this video, Linda demonstrates motions for /x/ and /y/. (From our video series Reading SOS: Expert Answers to Family Questions About Reading.)

In this video, Linda demonstrates motions for /x/ and /y/. (From our video series Reading SOS: Expert Answers to Family Questions About Reading.)

Sound games

Practice blending sounds into words. Ask "Can you guess what this word is? m - o - p." Hold each sound longer than normal.

First sounds

When you’re reading together with your child, pick a word from the book and say it with emphasis on the first sound. Pick another word and compare them. “Zzz-zookeeper and rrr-rhinoceros. Can you hear what sound zzz-zookeeper starts with? Is it the same as rrr-rhinoceros?

Jump, skip, hop!

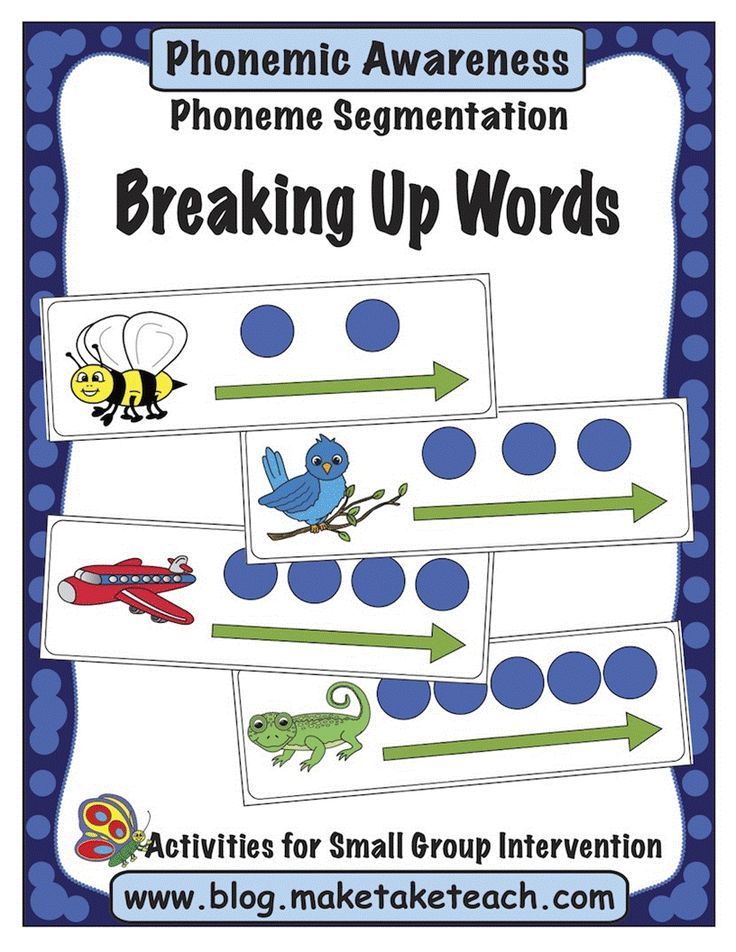

Create simple picture cards that you draw or cut out of magazines. Have your child, identify what's in the picture, and then break that word into its individual sounds. For example dog is d-o-g, three sounds (phonemes). Three sounds? You and your child do three jumping jacks, skips, or hops (followed by a high-five). You can also do this game outdoors without the cards, just call out simple words for your child.

Three sounds? You and your child do three jumping jacks, skips, or hops (followed by a high-five). You can also do this game outdoors without the cards, just call out simple words for your child.

Snail talk

Tell your child you're going to communicate in "snail talk" and they need to figure out what you're saying. Take a simple word and stretch it out very slowly (e.g., /fffffllllaaaag/), then ask your child to tell you the word. Switch roles and have your child stretch out a word for you.

"I spy" blending

Here's an easy phoneme blending game you can play while talking a walk. For blending, you can say, “I see a sign that says s-t-o-p” Then your child has to blend the sounds to guess your word — stop. (Remember to say only the sounds in the word — not the letters.) Keep the words short, moving from two to three to four sounds depending on your child’s skill level.

Sound counting

Using LEGO bricks, beads, or pennies, say a word and have your child show you how many sounds the word makes. For example, top = t-o-p = three sounds, so your child would place three objects in a row. Then have them tap each object as they say the sound. Remember, your child is just showing you the sounds they hear. So the word bike would be = b-i-k (silent e) = only three sounds.

For example, top = t-o-p = three sounds, so your child would place three objects in a row. Then have them tap each object as they say the sound. Remember, your child is just showing you the sounds they hear. So the word bike would be = b-i-k (silent e) = only three sounds.

Rime house

Try this activity from the Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR). The FCRR "At Home" series was developed especially for families! Watch the video and then download the activity: Rime House. See all FCRR phonological awareness activities here.

Phoneme dominoes

Try this activity from the Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR). The FCRR "At Home" series was developed especially for families! Watch the video and then download the activity: Phoneme Dominoes. See all FCRR phonological awareness activities here.

Picture slide

Try this activity from the Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR). The FCRR "At Home" series was developed especially for families! Watch the video and then download the activity: Picture Slide. See all FCRR phonological awareness activities here.

More phonological and phonemic awareness resources

📖 Phonological Awareness, Speech Development, Chapter 11. Communication and Skill Development Disorders. Children's pathopsychology. Mash E. Page 87. Read online

At first, babies listen to the sounds of their parents' speech and soon begin to communicate using basic gestures and sounds. During their first year of life, they may learn a few words and even create new words to express their desires and emotions. After two years, language development is rapidly progressing, and their ability to coherently formulate their thoughts and express new concepts is the delight and admiration of parents. Adults play an important role in encouraging the development of a child's language skills by improving speech and enjoying children's expressions. nine0008

During their first year of life, they may learn a few words and even create new words to express their desires and emotions. After two years, language development is rapidly progressing, and their ability to coherently formulate their thoughts and express new concepts is the delight and admiration of parents. Adults play an important role in encouraging the development of a child's language skills by improving speech and enjoying children's expressions. nine0008

A language consists of phonemes that are basic sounds (such as plosives b, e or vowels and, e) and form the language. When a child constantly hears a particular phoneme, ear receptors stimulate the formation of appropriate connections and transmit them to the auditory part of the cerebral cortex. The formed perception map is a set of sounds similar to each other, which helps the child to recognize different phonemes. These cards form quickly; six-month-old babies of English-speaking parents already have auditory maps that differ from the auditory maps inherent, for example, in babies in Swedish families, which depends on the different activity of neurons for different sounds (Kuhl, 1995). By the first year of life, the cards are formed, and babies lose the ability to distinguish sounds that are not important for their native language.

By the first year of life, the cards are formed, and babies lose the ability to distinguish sounds that are not important for their native language.

It is the rapid development of the perceptual map that causes difficulties in learning a second language after the first: the fact is that the connections in the brain are already formed, and the remaining neurons are almost unable to form new basic connections, say, for the Swedish language. When the described cycle is established, babies can make words out of sounds, and the more words they hear, the faster they learn the language. Sounds serve to strengthen and expand neural connections, which in turn ensures the formation of more words. Similar cortical circuits are formed as the basis for other activities, such as music. A young child who is learning to play a musical instrument may have neuronal circulation activated, which will favorably develop his spatial thinking and mathematical abilities (Hancock, 1996).

Phonological awareness.

Not all children progress normally in their language development, some are very lagging behind, using mostly gestures or sounds to communicate, rather than speech. Others develop normally following verbal commands, but have difficulty finding words to express their thoughts clearly.

Psychology bookap

Although the development of speech is one of the main indicators of general intelligence, as well as the development of the school curriculum (Sattler, 1998), the difference in this indicator is in no way a sign of intellectual retardation or cognitive impairment in children. Rather, such deviations from the norm may indeed be only deviations and are accompanied by pronounced abilities in other areas. Albert Einstein, considered an intellectual genius, started talking late, stammering and making his parents think he was "not quite normal". Family tradition says that when a father asked the headmaster what profession he would advise his son to take, the answer was simple: “It does not matter, because he will never succeed in anything” (R. W. Clark, 1971, p. 10).

W. Clark, 1971, p. 10).

Because speech development is an indicator of overall mental development (Sattler, 1998), children with language delays or severe language delays are considered to be at risk. As is known, Albert Einstein's speech problems were precursors to his subsequent communication and learning disorders (Benasich, Curtiss & Tallal, 1993; B.A. Lewis, Freebarn & Taylor, 2000).

Phonology is the ability to memorize and store phonemes, as well as the rules for composing semantic compounds or words from sounds. The impairment of this ability is the main reason why most children and adults with communication and learning disabilities have language problems such as reading and writing. nine0008

A young child needs to realize that speech is divided into phonemes (English has 44, such as ba, ga, at and tr). Many children find it very difficult to understand that speech does not consist of individual phonemes that follow one another. Instead, the sounds are articulated at the same time as (overlapping) so that one can speak faster than if they were spoken consecutively (Liberman & Shankweiler, 1991).

Instead, the sounds are articulated at the same time as (overlapping) so that one can speak faster than if they were spoken consecutively (Liberman & Shankweiler, 1991).

Early language problems become learning problems when they enter school as children have to learn to correlate spoken language with written language. Children who find it difficult to learn to read and write also find it difficult to learn the system of letters and sounds. These children cannot correctly pronounce the sounds in the syllables of words, which is called a lack of phonological awareness and is a harbinger of reading problems (Frost, 1998).

Phonological awareness is a broad generalization that includes recognizing the relationships that exist between sounds and letters, determining rhythm and alliteration, and knowing that sounds can form different syllables in words. To determine the level of phonological awareness among primary school students, teachers ask them to rhyme words or rearrange sounds. For example, the teacher might say "cat" and ask the child to say the word without the first sound k, or say "home" and the child must say the word without m. the child pronounce these sounds together, adding them to the word "three".

To determine the level of phonological awareness among primary school students, teachers ask them to rhyme words or rearrange sounds. For example, the teacher might say "cat" and ask the child to say the word without the first sound k, or say "home" and the child must say the word without m. the child pronounce these sounds together, adding them to the word "three".

While phonological awareness is a prerequisite for developing reading skills, it is also closely related to the development of expressive language (Edwards, Fourakis, Beckman, & Fox, 1999). In the process of reading, it is very difficult for those who experience significant difficulties in pronouncing sounds to differentiate phonemes, remember the names of ordinary objects and letters, as well as store phonological codes in short-term memory, recognize a phoneme and reproduce some speech sounds. For the most part, reading and comprehension depend on speed and the automatic ability to recognize individual words. Slow and inattentive children face very great difficulties in reading comprehension (Lyon, 1996).

Slow and inattentive children face very great difficulties in reading comprehension (Lyon, 1996).

Section summary.

- The development of speech is based on the innate ability and acquired capabilities to learn, store and reproduce the basic sounds in the language, it occurs very quickly, in early childhood.

- Deficiency in phonological awareness the ability to distinguish the sounds of a language is the main cause of communication disorders and impaired development of school skills.

Development of the phonological system of language in children

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION OF THE MOSCOW REGION

State educational institution of higher education of the Moscow Region

Moscow State Regional University (MGOU)

Faculty of Special Pedagogy and Psychology

Department of Logopedics

Abstract

in the discipline: “Ontogenesis of speech activity”

on the topic: “Development of phonological language systems in children”

Completed by a student:

14. C(D)OOB.20.DL.1 group 2 course

C(D)OOB.20.DL.1 group 2 course

Full -time education

Faculty of Special Pedagogy and Psychology

Chugunova Olga Aleksandrovna

Content

Introduction 3

PRELINGSTIC Development (birth - 1 year) 4

Development after speech establishment (1 year and older) 6

Quick Display 8

Production 9

Conclusion 12

List of references 13

. These two sides of one process - the process of mastering the native language - are closely interconnected. On the one hand, the improvement of speech skills, the practical assimilation of language means are a necessary condition for the subsequent awareness of linguistic reality; on the other hand, “the conscious operation of language, its elements and their relations is not a self-contained, purely theoretical relation to linguistic reality, isolated from the construction of a speech utterance. The significance of understanding linguistic phenomena also lies in the fact that, on its basis, speech skills and abilities are transferred from an automatic plan to an arbitrary plan . .. which ensures greater efficiency of communications and further speech development. nine0008

.. which ensures greater efficiency of communications and further speech development. nine0008

Phonological development refers to how children learn to translate sounds into meanings or language (phonology) during their growth stages.

Perception

Children do not speak their first words until they are about one year old, but already at birth they can distinguish some utterances in their native language from utterances in languages with different prosodic features.

1 month

Categorical perception

Infants at the age of 1 month perceive some speech sounds as categories of speech (they display categorical perception of speech). Infants up to 10–12 months old can distinguish not only native sounds, but also non-native contrasts. Older children and adults lose the ability to distinguish between non-native contrasts. Thus, familiarity with one's native language seems to cause a restructuring of the perceptual system. The restructuring reflects the system of contrasts in the native language. nine0008

nine0008

4 months

At four months, babies still prefer infant speech to adult speech. While 1-month-olds only show this preference if they are presented with a full speech signal, 4-month-olds prefer infant-controlled speech. This shows that between 1 and 4 months of age, infants improve tracking of suprasegmental information in speech addressed to them. By 4 months, infants finally learned what features they should look for at the suprasegmental level. nine0008

5 months

Babies prefer to hear their own name over similar-sounding words. They may have associated the meaning of "I" with their name, although it is also possible that they simply recognize the form due to its high frequency.

6 months

As exposure to surrounding language increases, infants learn to ignore sound differences that do not make sense in their native language, such as two acoustically different versions of the vowel /i/ that simply differ due to the variance between speaking. By 6 months, babies learn to perceive different acoustic sounds that represent the same sound. a category, such as /i/, which is spoken by a man and not by a woman, as members of the same phonological category /i/. nine0008

By 6 months, babies learn to perceive different acoustic sounds that represent the same sound. a category, such as /i/, which is spoken by a man and not by a woman, as members of the same phonological category /i/. nine0008

8 months

While babies don't usually understand the meaning of most individual words, they do understand the meaning of certain phrases they hear frequently, such as "Stop" or "Come here."

9 months

Infants can distinguish native from non-native language input using only phonetic and phonotactic patterns, i.e. without the help of prosodic cues. They seem to have learned the phonotactics of their native language, i.e., what combinations of sounds are possible in the language. nine0008

10-12 months

Infants are now unable to distinguish between most sound contrasts that do not belong to the same sound category in their native language. Their perceptual system is tuned to the contrasts characteristic of their native language. In terms of word comprehension, we checked the size of the vocabulary of children aged 10-11 months and found a range from 11 to 154 words. At this age, children usually do not yet begin to speak and, therefore, do not have a productive vocabulary. So, it is clear that the vocabulary of understanding develops earlier than the production vocabulary. nine0008

At this age, children usually do not yet begin to speak and, therefore, do not have a productive vocabulary. So, it is clear that the vocabulary of understanding develops earlier than the production vocabulary. nine0008

O. G. Prikhodko distinguishes a number of stages or periods in the pre-speech development of children: In it, the main role is played by unconditioned food and protective or defensive reflexes. The main manifestation is vocal reactions, closely related to vital physiological functions. In addition, during this period, the vocal reactions of the newborn include coughing, sneezing, yawning, grunting, sucking sounds;

G., 2003). nine0152

G., 2003). nine0152 At the age of 1, children are just beginning to speak, and their utterances are not at all like adults. The perceptual abilities of children are also still developing. In fact, both productive and perceptual abilities continue to develop during the school years, with the perception of some prosodic facial features not fully developed until about age 12.

Perception

14 months

Children can distinguish newly learned "words" associated with objects if they do not sound the same. While children at this age are able to distinguish monosyllabic minimal pairs on a purely phonological level, if the task of recognition is combined with the meaning of a word, the additional cognitive load required to learn the meanings of words does not allow them to spend extra effort on distinguishing similar phonology. nine0008

16 months

Children's vocabulary ranges from 92 to 321 words. [13] The volume of industrial vocabulary at this age is usually about 50 words. This shows that the vocabulary of intelligible speech is growing faster than the vocabulary of industrial speech.

This shows that the vocabulary of intelligible speech is growing faster than the vocabulary of industrial speech.

18-20 months

At 18-20 months, infants can distinguish newly learned 'words', even if they are phonologically similar. While infants can distinguish syllables like them shortly after birth, they can only now distinguish them if they are presented to them as meaningful words and not just a sequence of sounds. Children can also detect such mispronunciations." It has been found that mispronounced words are less recognizable than correctly pronounced words. This suggests that infants' representations of familiar words are phonetically very accurate. This result has also been used to suggest that infants transition from verbal to verbal segment based on the phonological system around 18 months of age. nine0008

Of course, children need to learn the sound features of their language, because then they also need to learn the meaning associated with these different sounds. Young children have a remarkable ability to memorize the meanings of words that they extract from the speech they hear, that is, to map meaning onto sounds. Often children already associate meaning with a new word after one use. This is called "fast display". Children as young as 15 months can successfully complete this task if the experiment is done with fewer items. This task shows that children between the ages of 15 and 20 months can attach meaning to a new word only after a single exposure. Rapid display is a necessary ability for children to acquire the number of words they need to learn during the first few years of life: children acquire an average of nine words per day between 18 months and 6 years of age. nine0008

Young children have a remarkable ability to memorize the meanings of words that they extract from the speech they hear, that is, to map meaning onto sounds. Often children already associate meaning with a new word after one use. This is called "fast display". Children as young as 15 months can successfully complete this task if the experiment is done with fewer items. This task shows that children between the ages of 15 and 20 months can attach meaning to a new word only after a single exposure. Rapid display is a necessary ability for children to acquire the number of words they need to learn during the first few years of life: children acquire an average of nine words per day between 18 months and 6 years of age. nine0008

2-6 years old

At 2 years old, babies show their first signs of phonological awareness, ie they are interested in wordplay, rhyming and alliteration. Phonological awareness continues to develop until the early grades of school.

Children are early aware of syllables as units of speech, while they do not show awareness of individual characteristics. phonemes before school age. Another explanation is that individual sounds are not easily translated into beats, so clapping for individual phonemes is much more difficult than clapping for syllables. One of the reasons phoneme understanding gets so much better when children go to school is that learning to read provides visual aids on how to break words down into smaller pieces. nine0008

phonemes before school age. Another explanation is that individual sounds are not easily translated into beats, so clapping for individual phonemes is much more difficult than clapping for syllables. One of the reasons phoneme understanding gets so much better when children go to school is that learning to read provides visual aids on how to break words down into smaller pieces. nine0008

12-14 months

Babies usually say their first word at 12-14 months of age. The first words have a simple structure and contain the same sounds used in later babble. The lexical items they create are likely stored as whole words, rather than as individual segments that are collected in a network as they are spoken. This is indicated by the fact that babies at this age can reproduce the same sounds differently in different words.

16 months

The vocabulary of children at this age is typically around 50 words, although the vocabulary size of children in the same age group varies greatly, with most children ranging from 0 to 160 words.

18 months

Children's performances become more stable at about 18 months. When their words differ from the adult forms, these differences are more systematic than before. These systematic transformations are called "phonological processes", and often resemble processes that are usually characteristic of the adult phonology of the world's languages (cf. adult Jamaican Creole duplication: "yellow yellow" = "very yellow"). Listed below are some common phonological processes. nine0008

2 years

The volume of the production vocabulary ranges from 50 to 550 words at the age of 2 years. Effects on the rate of word acquisition, and therefore on the wide range of vocabulary sizes of children of the same age, include the amount of speech children are exposed to by caregivers, as well as differences in how rich the child's vocabulary is. hears. It also seems that children build vocabulary faster if the speech they hear is more often related to their focus of attention. This will happen if the guardian talks about the ball that the child is currently looking at. nine0008

This will happen if the guardian talks about the ball that the child is currently looking at. nine0008

4 years

tested the phonological memory of 4-5 year old children, that is, how well these children can memorize a sequence of unfamiliar sounds. They found that children with better phonological memory also had larger vocabulary at both ages. Moreover, phonological memory at age 4 predicted children's vocabulary at age 5, even after adjusting for earlier vocabulary and non-verbal intelligence.

7 years old

Children produce mainly adult segments. Their ability to create complex sound sequences and polysyllabic words continues to improve into middle childhood. nine0008

All children in the process of mastering speech make mistakes in pronunciation - these are not real mistakes. They are caused by the development of the child's individual phonological code and deviations in phonological development.

The most typical mistakes of children mastering the "adult" system of sounds:

- voiceless consonants are pronounced at the beginning of a word as voiced (aunt-child) - up to three years;

- voiced consonants are replaced by voiceless consonants at the end of a word (ded-det) - usually disappears by the age of three; nine0152

- loss of the final consonant (Kolya-Koya) - disappears by three years and three months;

- a sound correctly pronounced by pressing the middle of the tongue against the hard palate is produced by the tip of the tongue (lip-oak) - up to three years and six months;

- inability to pronounce hissing sounds (splinter-sepka) — manifests itself up to three years and six months;

- the presence of a specific sound affects the pronunciation of the whole word (horn-gog) - up to three years nine months;

- the child "swallows" unstressed, "weak" syllables (telephone-teffon") - up to four years; nine0152

- the child "loses" sounds (bunt-bat) - up to four years;

- in some cases, children replace smooth consonants with other sounds (hand-bow) or replace plosive consonants (flag-slug).

The central factors that determine the algorithm of phonological development are the maturation and extension of the repertoire of articulatory skills, cognitive development and development of language abilities with the gradual abolition of paradigmatic and syntagmatic restrictions. Moving from the syncretic to the segmental level of operating with phonological constructions, the child forms a system of phonemic oppositions and their differential signs, which are generalizations of articulatory or acoustic images. He includes the newest sound in his phonological system later than the articulatory probabilities of its realization ripen (Gvozdev A.N., 1948, Beltyukov V.I., 1979). The absence of such a probability forces him to choose a compromise path: phonemic oppositions (of the language of adults) merge in the face of that member of them, the one that experiences the least articulatory restrictions, that is, the original individual sound.