Age for reading

Reading Milestones (for Parents) - Nemours KidsHealth

Reviewed by: Cynthia M. Zettler-Greeley, PhD

Nemours BrightStart!

en español Hitos en la lectura

This is a general outline of the milestones on the road to reading success. Keep in mind that kids develop at different paces and spend varying amounts of time at each stage. If you have concerns, talk to your child's doctor, teacher, or the reading specialist at school. Getting help early is key for helping kids who struggle to read.

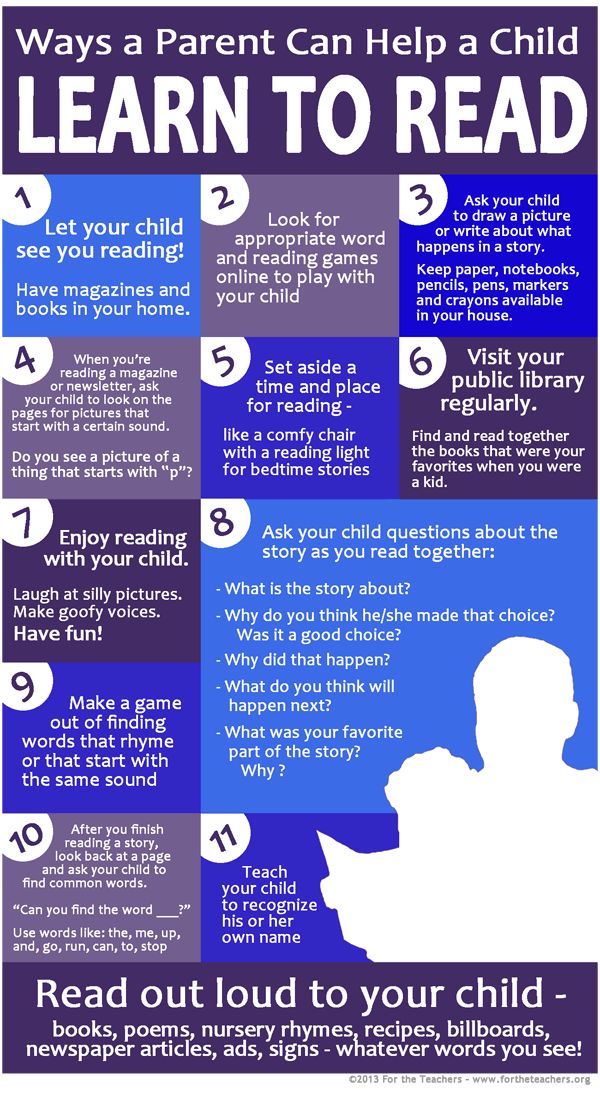

Parents and teachers can find resources for children as early as pre-kindergarten. Quality childcare centers, pre-kindergarten programs, and homes full of language and book reading can build an environment for reading milestones to happen.

Infancy (Up to Age 1)

Kids usually begin to:

- learn that gestures and sounds communicate meaning

- respond when spoken to

- direct their attention to a person or object

- understand 50 words or more

- reach for books and turn the pages with help

- respond to stories and pictures by vocalizing and patting the pictures

Toddlers (Ages 1–3)

Kids usually begin to:

- answer questions about and identify objects in books — such as "Where's the cow?" or "What does the cow say?"

- name familiar pictures

- use pointing to identify named objects

- pretend to read books

- finish sentences in books they know well

- scribble on paper

- know names of books and identify them by the picture on the cover

- turn pages of board books

- have a favorite book and request it to be read often

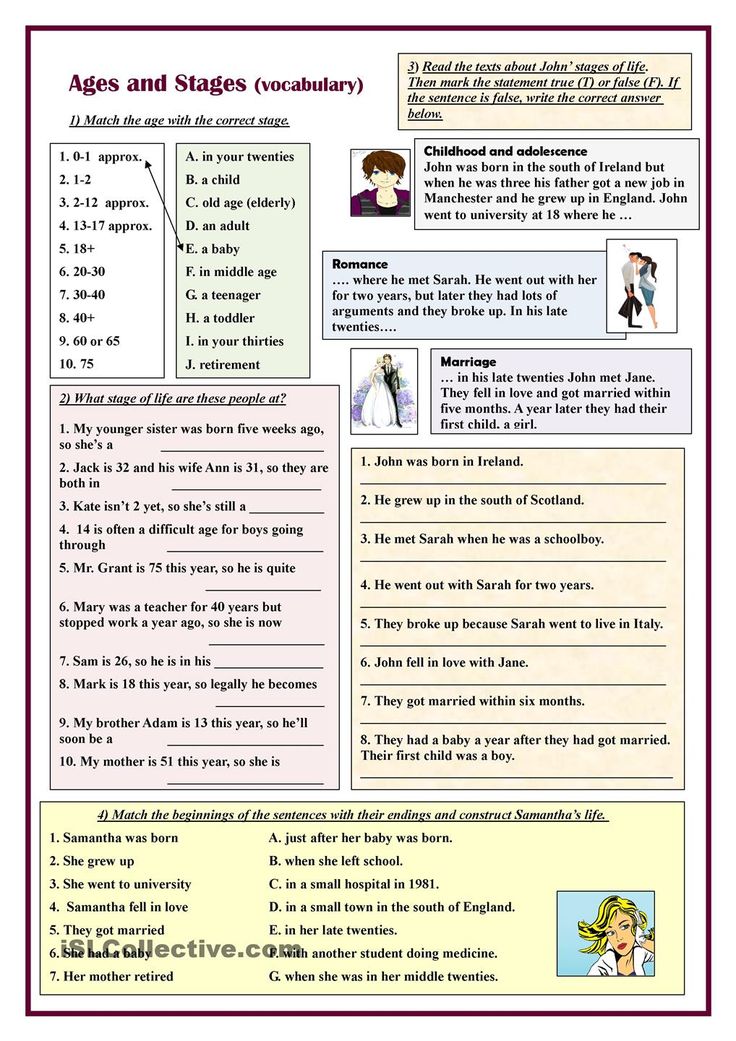

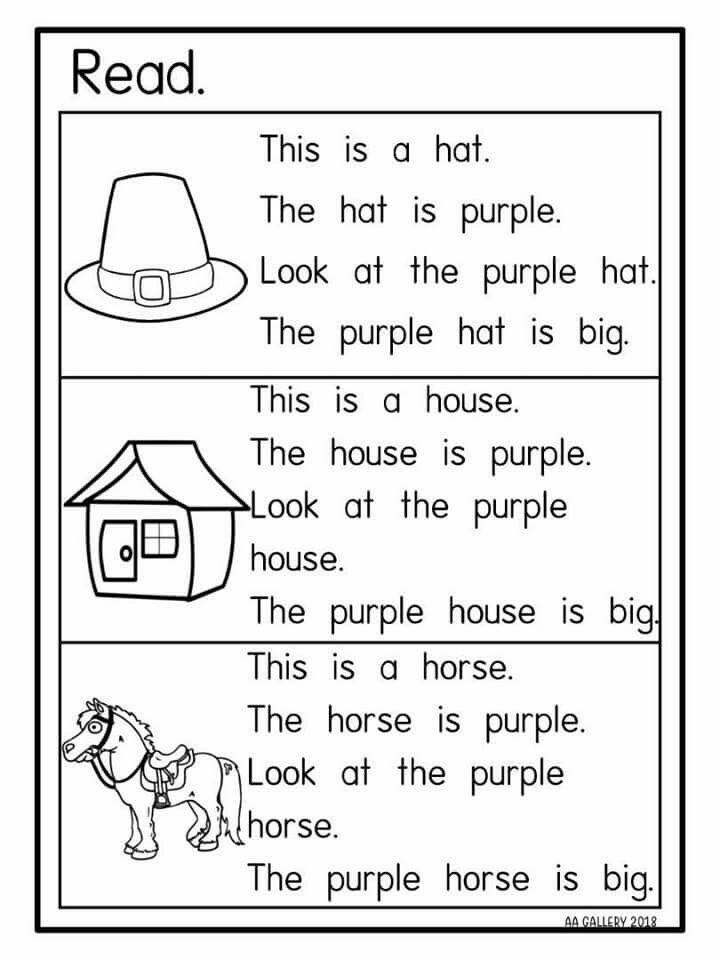

Early Preschool (Age 3)

Kids usually begin to:

- explore books independently

- listen to longer books that are read aloud

- retell a familiar story

- sing the alphabet song with prompting and cues

- make symbols that resemble writing

- recognize the first letter in their name

- learn that writing is different from drawing a picture

- imitate the action of reading a book aloud

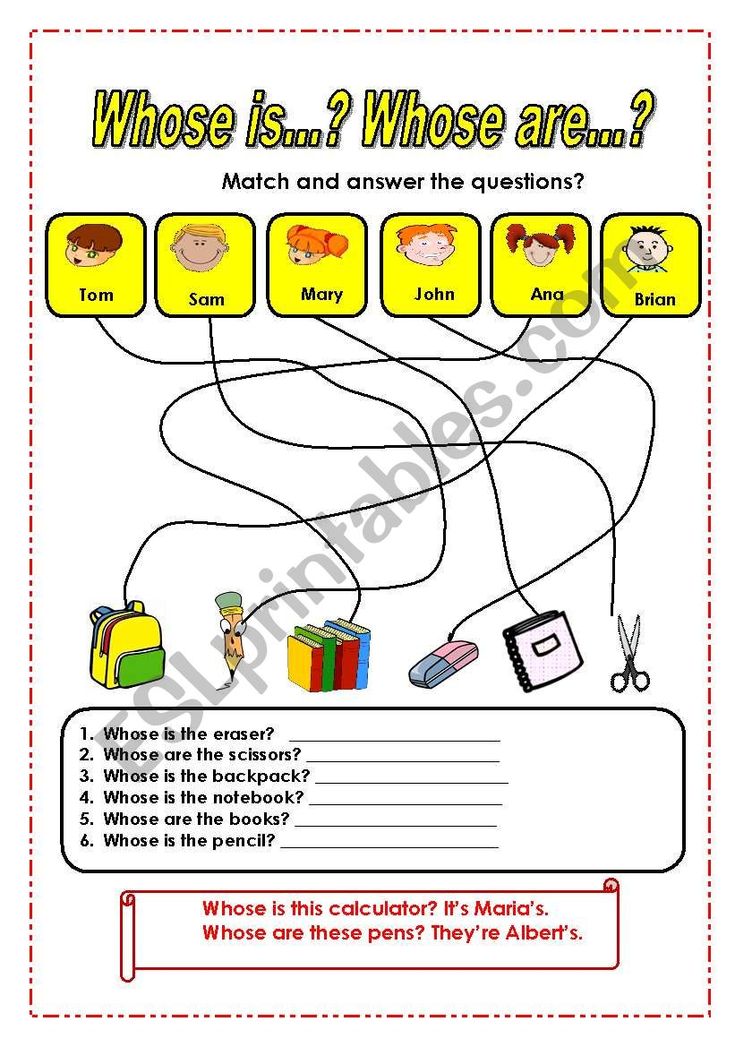

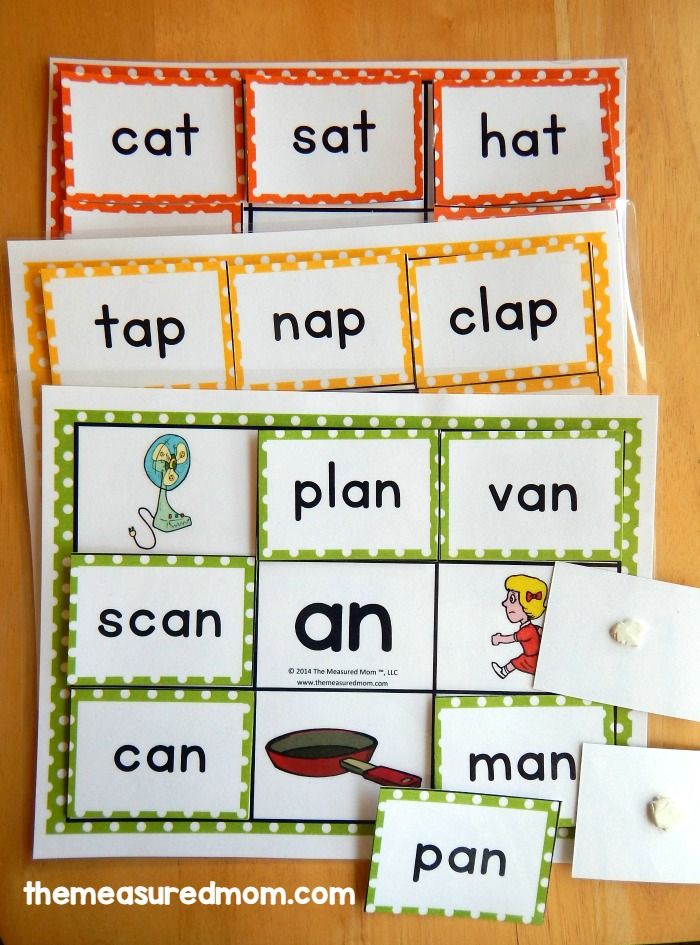

Late Preschool (Age 4)

Kids usually begin to:

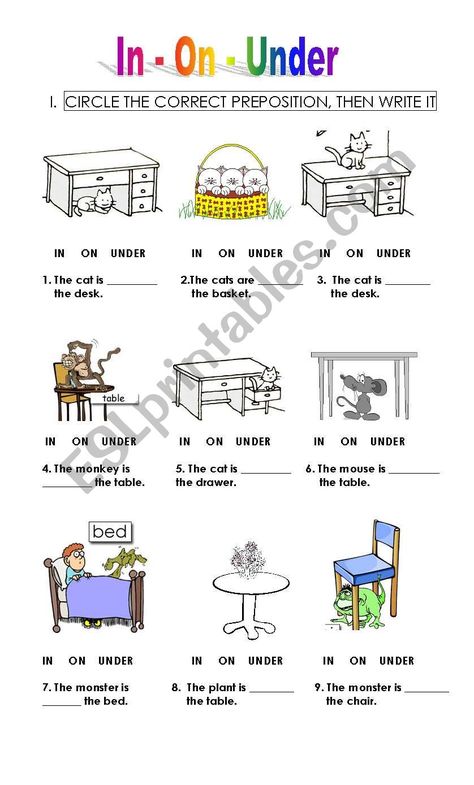

- recognize familiar signs and labels, especially on signs and containers

- recognize words that rhyme

- name some of the letters of the alphabet (a good goal to strive for is 15–18 uppercase letters)

- recognize the letters in their names

- write their names

- name beginning letters or sounds of words

- match some letters to their sounds

- develop awareness of syllables

- use familiar letters to try writing words

- understand that print is read from left to right, top to bottom

- retell stories that have been read to them

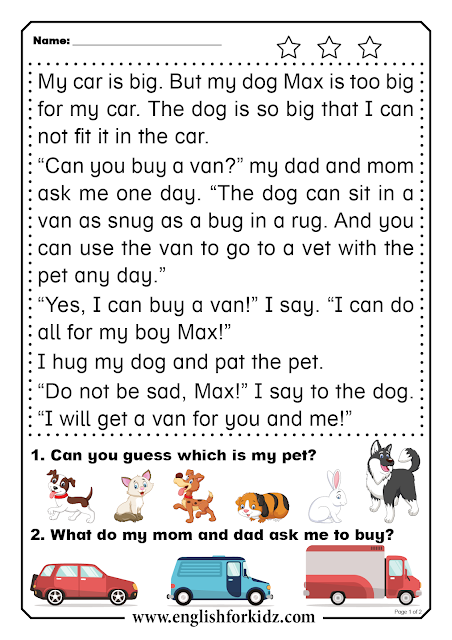

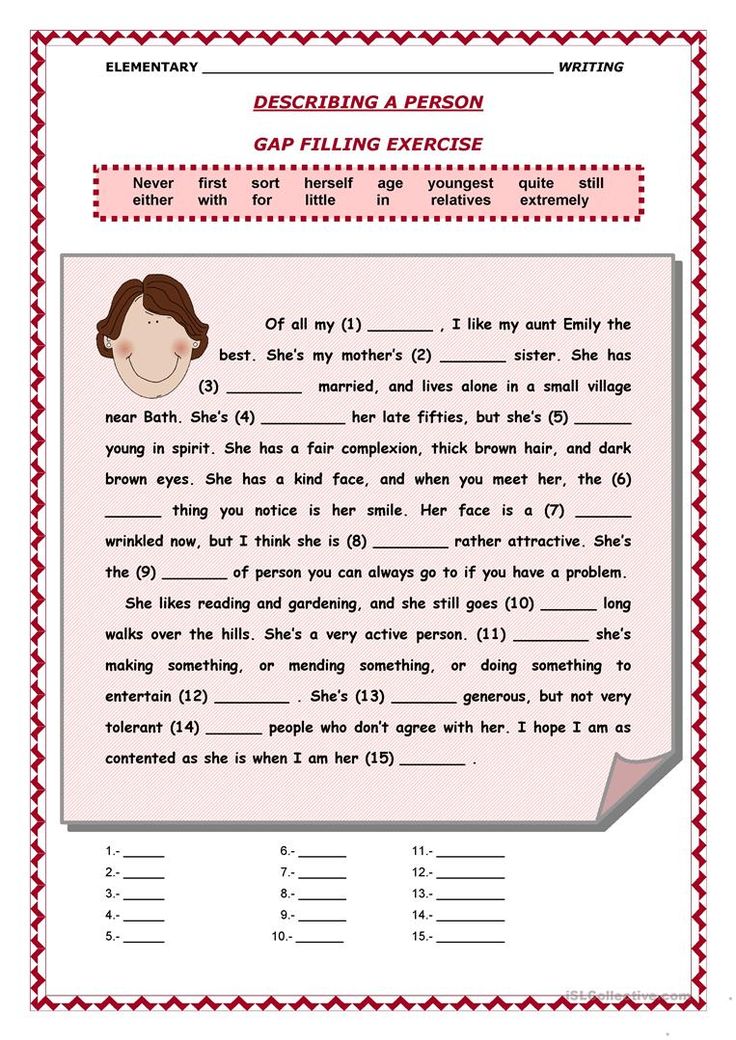

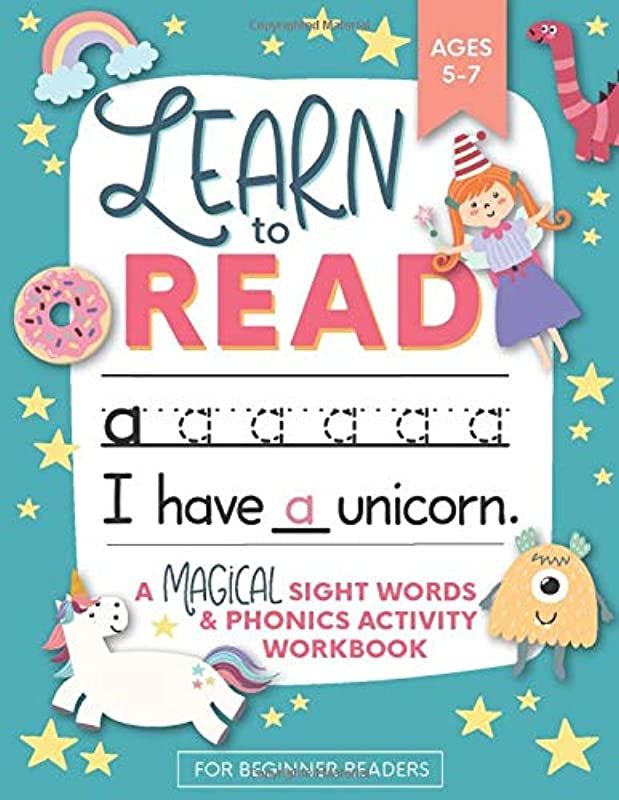

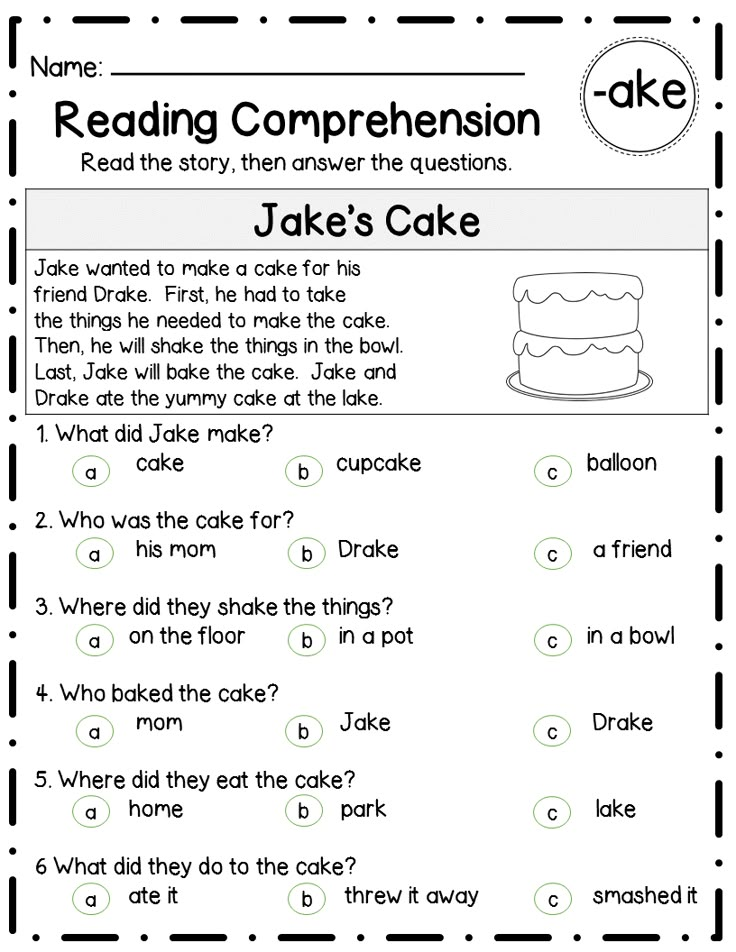

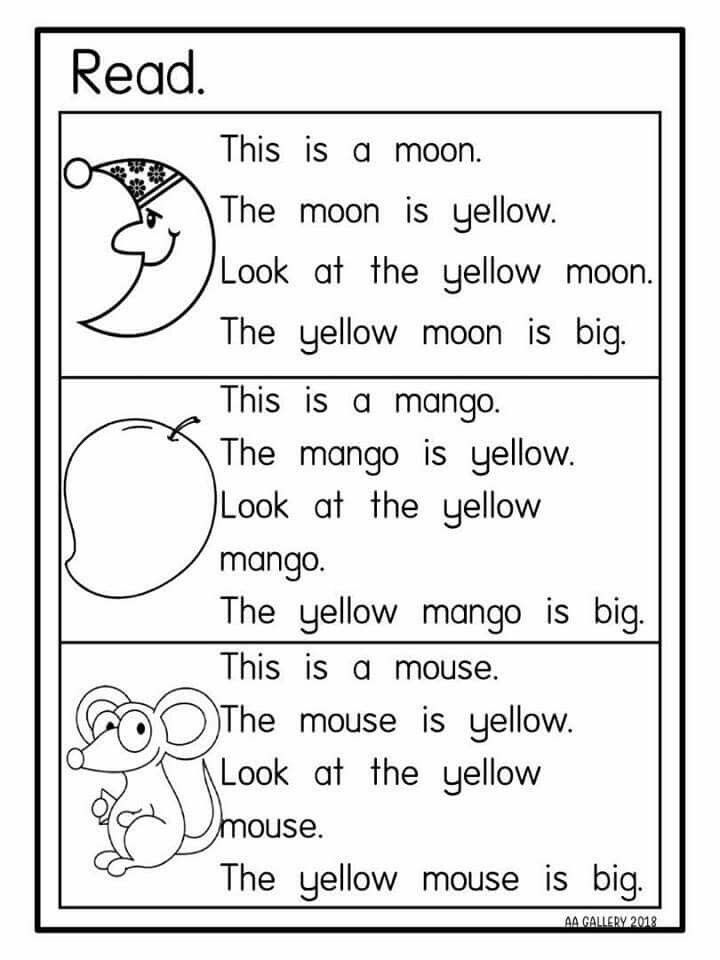

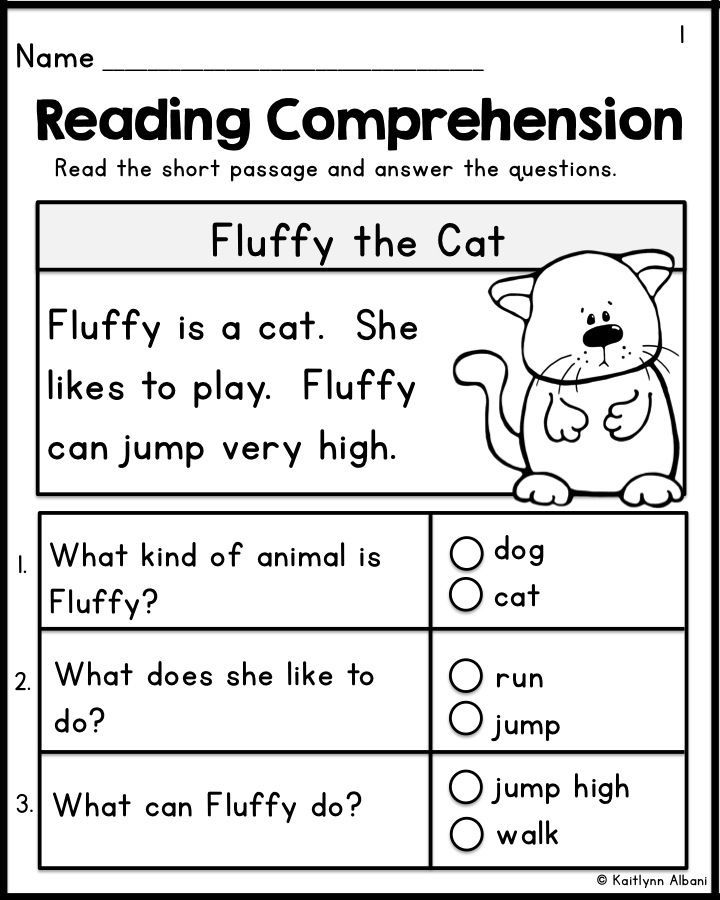

Kindergarten (Age 5)

Kids usually begin to:

- produce words that rhyme

- match some spoken and written words

- write some letters, numbers, and words

- recognize some familiar words in print

- predict what will happen next in a story

- identify initial, final, and medial (middle) sounds in short words

- identify and manipulate increasingly smaller sounds in speech

- understand concrete definitions of some words

- read simple words in isolation (the word with definition) and in context (using the word in a sentence)

- retell the main idea, identify details (who, what, when, where, why, how), and arrange story events in sequence

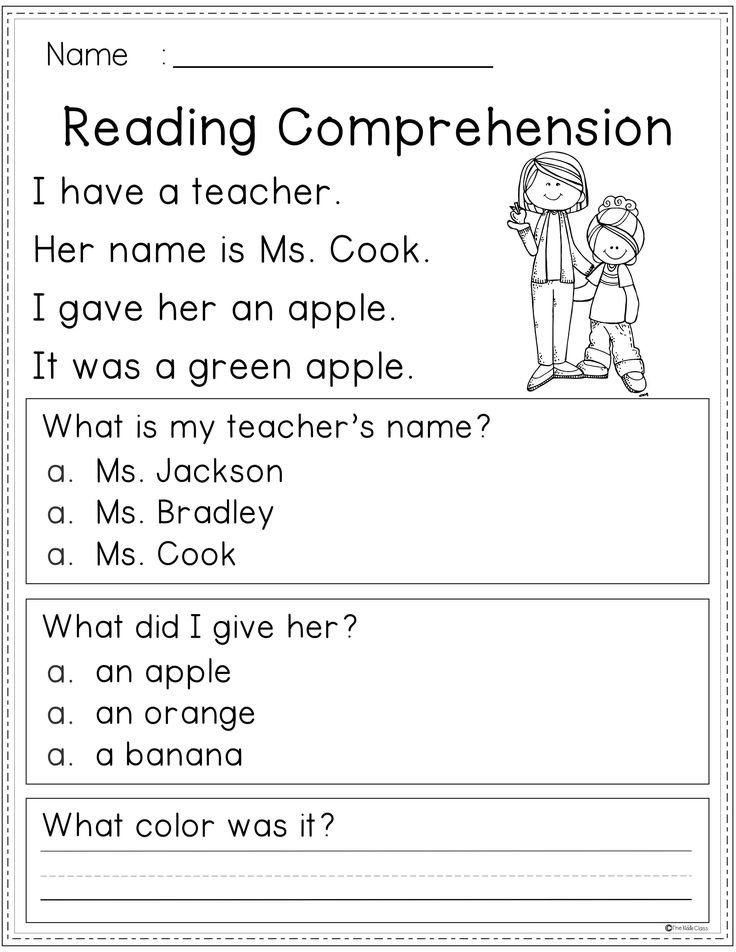

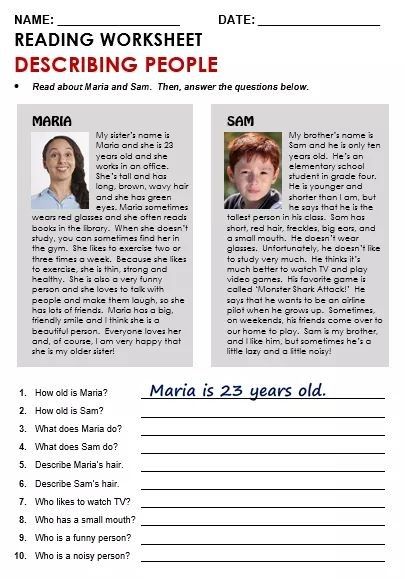

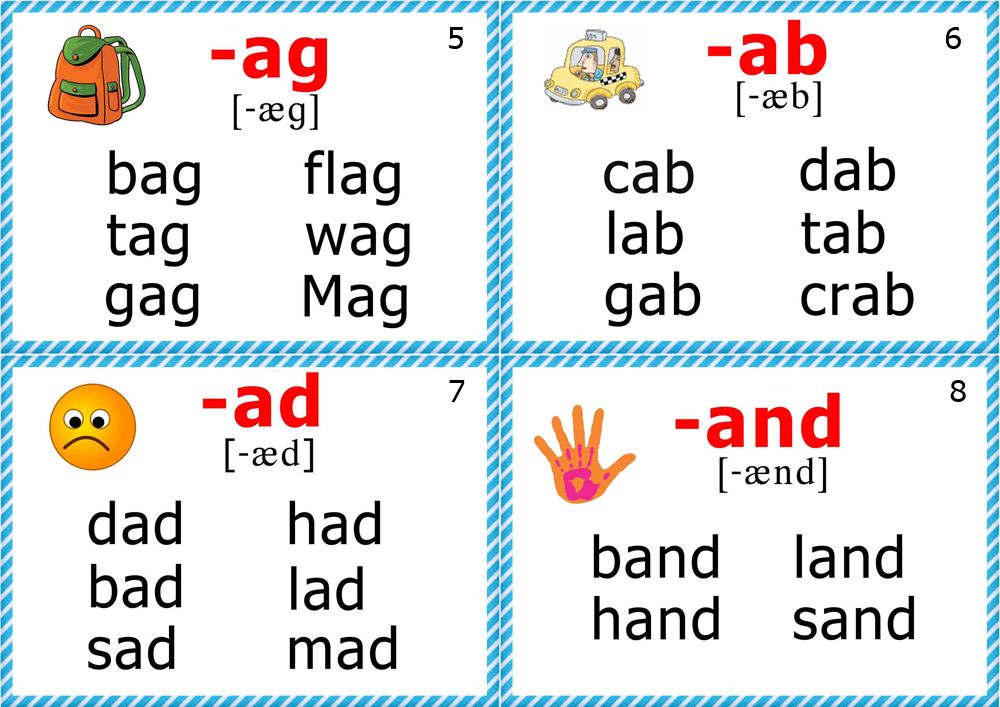

First and Second Grade (Ages 6–7)

Kids usually begin to:

- read familiar stories

- "sound out" or decode unfamiliar words

- use pictures and context to figure out unfamiliar words

- use some common punctuation and capitalization in writing

- self-correct when they make a mistake while reading aloud

- show comprehension of a story through drawings

- write by organizing details into a logical sequence with a beginning, middle, and end

Second and Third Grade (Ages 7–8)

Kids usually begin to:

- read longer books independently

- read aloud with proper emphasis and expression

- use context and pictures to help identify unfamiliar words

- understand the concept of paragraphs and begin to apply it in writing

- correctly use punctuation

- correctly spell many words

- write notes, like phone messages and email

- understand humor in text

- use new words, phrases, or figures of speech that they've heard

- revise their own writing to create and illustrate stories

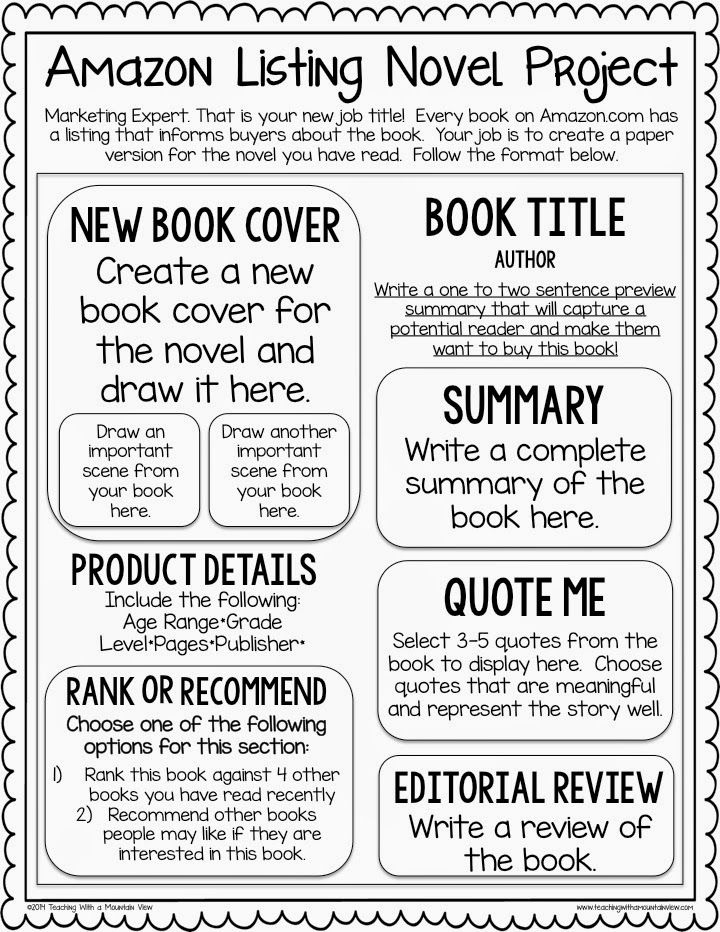

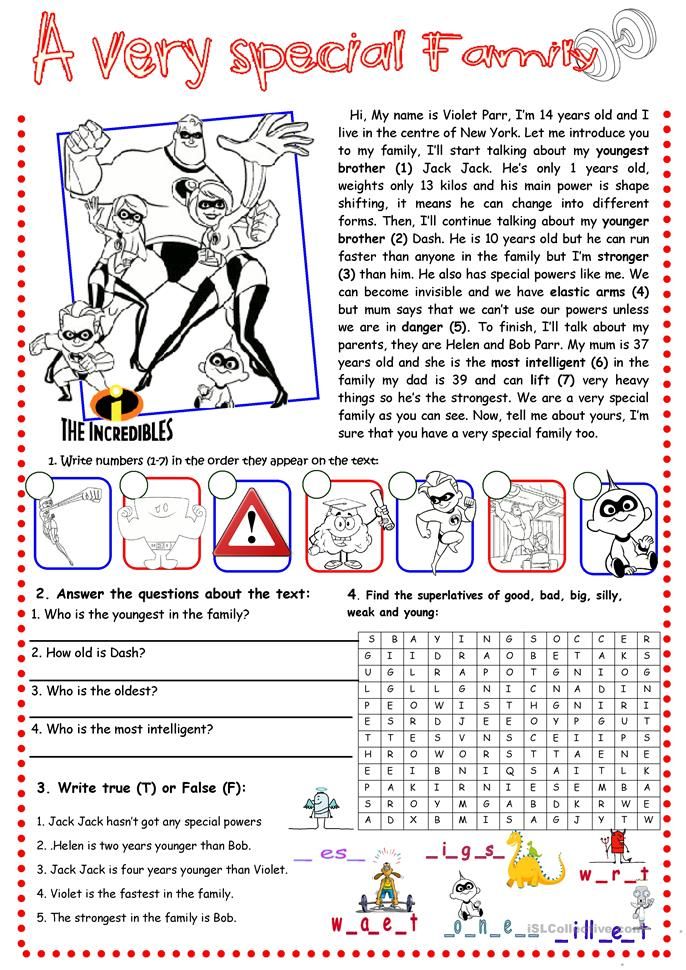

Fourth Through Eighth Grade (Ages 9–13)

Kids usually begin to:

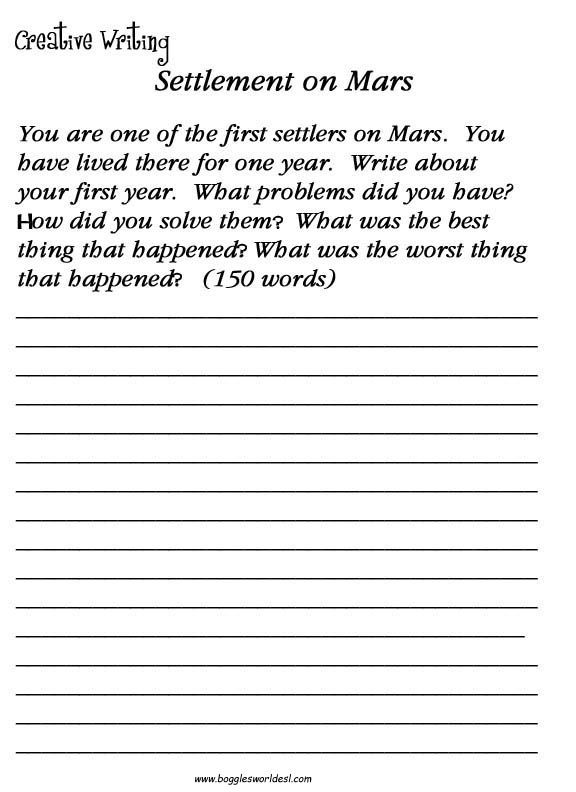

- explore and understand different kinds of texts, like biographies, poetry, and fiction

- understand and explore expository, narrative, and persuasive text

- read to extract specific information, such as from a science book

- understand relations between objects

- identify parts of speech and devices like similes and metaphors

- correctly identify major elements of stories, like time, place, plot, problem, and resolution

- read and write on a specific topic for fun, and understand what style is needed

- analyze texts for meaning

Reviewed by: Cynthia M. Zettler-Greeley, PhD

Date reviewed: May 2022

What is the best age to learn to read?

Loading

Family Tree | Education

What is the best age to learn to read?

(Image credit: Ozge Elif Kizil/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

By Melissa Hogenboom

2nd March 2022

In some countries, kids as young as four learn to read and write. In others, they don't start until seven. What's the best formula for lasting success? Melissa Hogenboom investigates.

I

I was seven years old when I started to learn to read, as is typical of the alternative Steiner school I attended. My own daughter attends a standard English school, and started at four, as is typical in most British schools.

Watching her memorise letters and sound out words, at an age when my idea of education was climbing trees and jumping through puddles, has made me wonder how our different experiences shape us. Is she getting a crucial head-start that will give her lifelong benefits? Or is she exposed to undue amounts of potential stress and pressure, at a time when she should be enjoying her freedom? Or am I simply worrying too much, and it doesn't matter at what age we start reading and writing?

Is she getting a crucial head-start that will give her lifelong benefits? Or is she exposed to undue amounts of potential stress and pressure, at a time when she should be enjoying her freedom? Or am I simply worrying too much, and it doesn't matter at what age we start reading and writing?

There's no doubt that language in all its richness – written, spoken, sung or read aloud – plays a crucial role in our early development. Babies already respond better to the language they were exposed to in the womb. Parents are encouraged to read to their children before they are even born, and when they are babies. Evidence shows that how much or how little we are talked to as children can have lasting effects on future educational achievement. Books are a particularly important aspect of that rich linguistic exposure, since written language often includes a wider and more nuanced and detailed vocabulary than everyday spoken language. This can in turn help children increase their range and depth of expression.

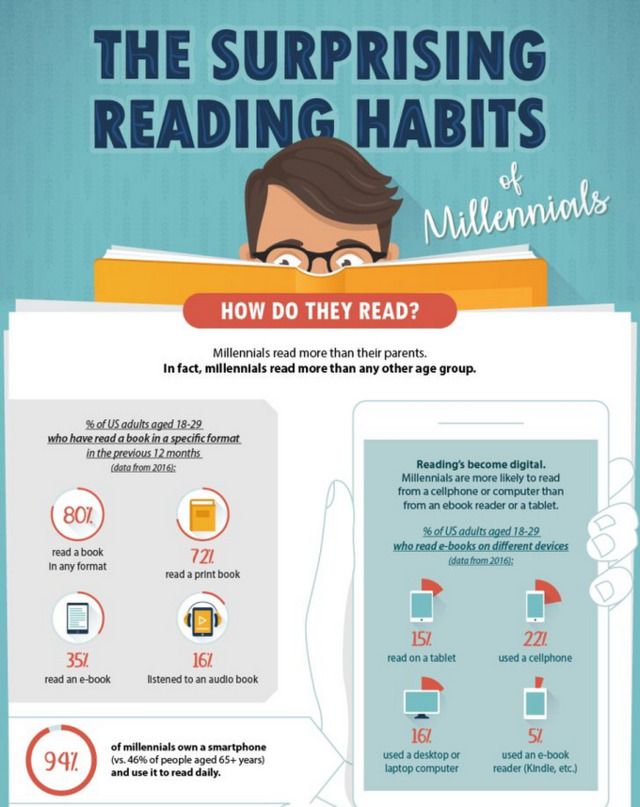

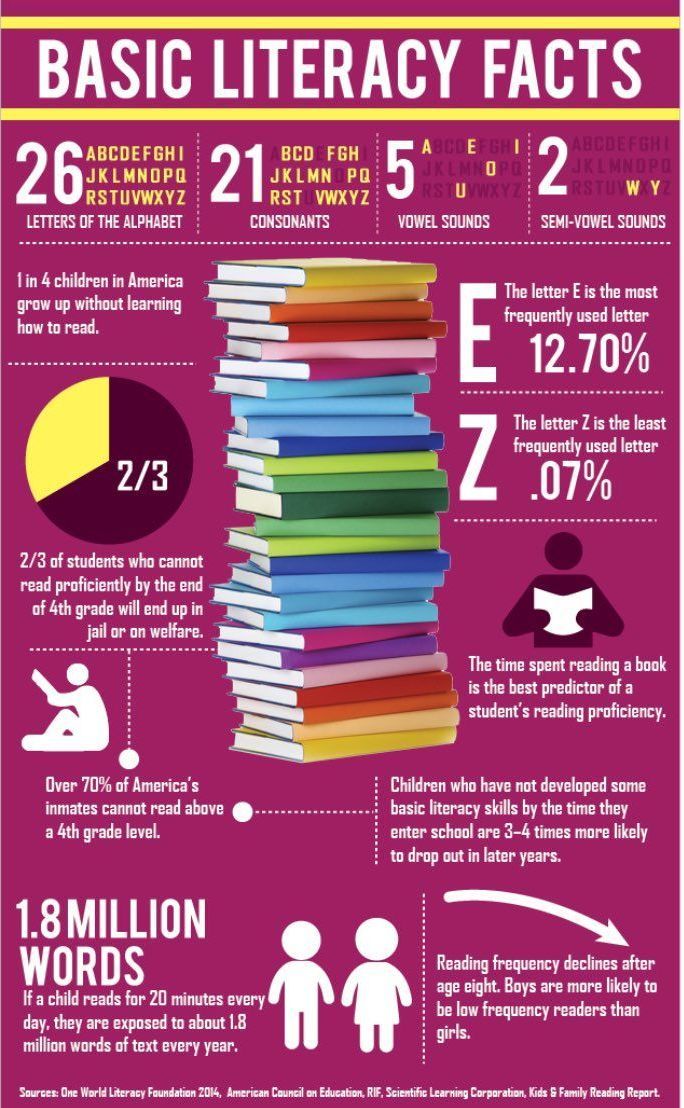

Since a child's early experience of language is considered so fundamental to their later success, it has become increasingly common for preschools to begin teaching children basic literacy skills even before formal education starts. When children begin school, literacy is invariably a major focus. This goal of ensuring that all children learn to read and write has become even more pressing as researchers warn that the pandemic has caused a widening achievement gap between wealthier and poorer families, increasing academic inequality.

There are many ways to enjoy reading. In this Namibian school, blind and visually impaired children learn the Braille script (Credit: Oleksandr Rupeta/NurPhoto/Getty Images)

Family Tree

In many countries, formal education starts at four. The thinking often goes that starting early gives children more time to learn and excel. The result, however, can be an "education arms race", with parents trying to give their child early advantages at school through private coaching and teaching, and some parents even paying for children as young as four to have additional private tutoring.

Compare that to the more play-based early education of several decades ago, and you can see a huge change in policy, based on very different ideas of what our children need in order to get ahead. In the US, this urgency sped up with policy changes such as the 2001 "no child left behind" act, which promoted standardised testing as a way to measure educational performance and progress. In the UK, children are tested in their second year of school (age 5-6) to check they are reaching the expected reading standard. Critics warn that early testing like this can put children off reading, while proponents say it helps to identify those who need additional support.

However, many studies show little benefit from an early overly-academic environment. One 2015 US report says that society's expectations of what children should achieve in kindergarten has changed, which is leading to "inappropriate classroom practices", such as reducing play-based learning.

The risk of "schoolification"

How children learn and the quality of the environment is hugely important. "Young children learning to read is one of the most important things primary education does. It's fundamental to children making progress in life," says Dominic Wyse, a professor of primary education at University College London, in the UK. He, alongside sociology professor Alice Bradbury, also at UCL, has published research proposing that the way we teach literacy really matters.

"Young children learning to read is one of the most important things primary education does. It's fundamental to children making progress in life," says Dominic Wyse, a professor of primary education at University College London, in the UK. He, alongside sociology professor Alice Bradbury, also at UCL, has published research proposing that the way we teach literacy really matters.

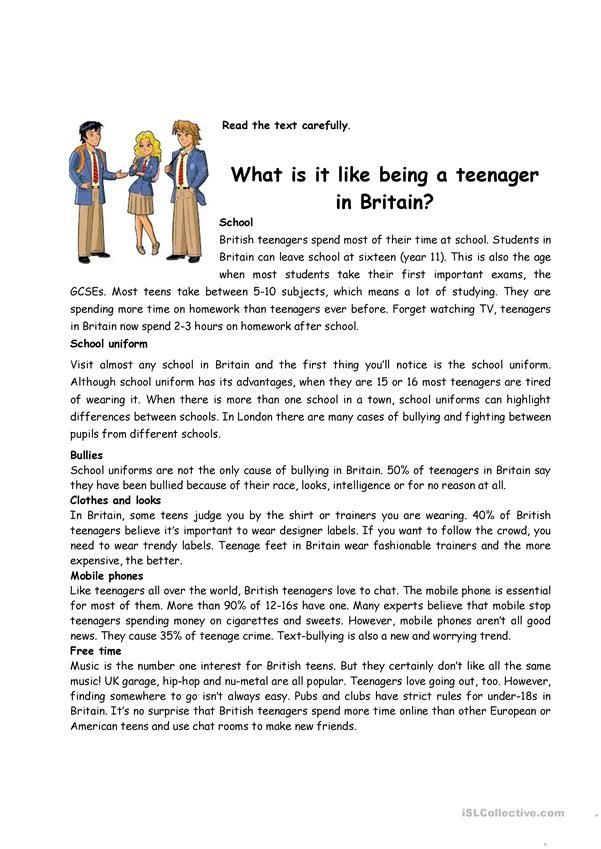

In a 2022 report, they state that English school system's intense focus on phonics – a method that involves matching the sound of a spoken word or letter, with individual written letters, through a process called "sounding out" – could be failing some children.

A reason for this, says Bradbury, is that the "schoolification of early years" has resulted in more formal learning earlier on. But the tests used to assess that early learning may have little to do with the skills actually needed to read and enjoy books or other meaningful texts.

For example, the tests may ask pupils to "sound out" and spell nonsense words, to prevent them from simply guessing, or recognising familiar words. Since nonsense words are not meaningful language, children may find the task difficult and puzzling. Bradbury found that the pressure to gain these decoding skills – and pass reading tests – also means that some three-year-olds are already being exposed to phonics.

Since nonsense words are not meaningful language, children may find the task difficult and puzzling. Bradbury found that the pressure to gain these decoding skills – and pass reading tests – also means that some three-year-olds are already being exposed to phonics.

"It doesn't end up being meaningful, it ends up being memorising rather than understanding context," says Bradbury. She also worries that the books used are not particularly engaging.

Language in all its richness – written, spoken, sung or read aloud – plays a crucial role in our early development (Credit: Xie Chen/VCG via Getty Images)

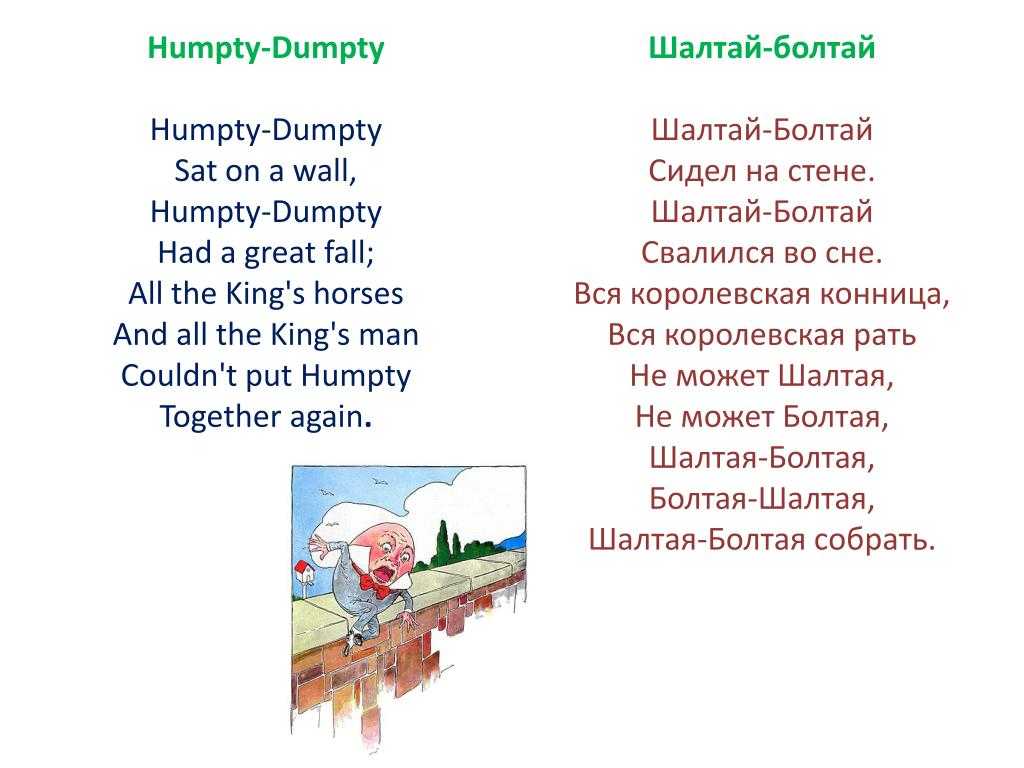

Neither Wyse nor Bradbury make the case for later learning per se, but rather highlight that we should rethink the way children are taught literacy. The priority, they say, should be to encourage an interest in and familiarity with words, using storybooks, songs and poems, all of which help the child pick up the sounds of words, as well as expanding their vocabulary.

This idea is backed up by studies that show that the academic benefits of preschool fade away later on. Children who attend intensive preschools do not have higher academic abilities in later grades than those who did not attend such preschools, several studies now show. Early education can however have a positive impact on social development – which in turn feeds into the likelihood of graduation from school and university as well as being associated with lower crime rates. In short, attending preschool can have positive effects on later achievement in life, but not necessary on academic skills.

Children who attend intensive preschools do not have higher academic abilities in later grades than those who did not attend such preschools, several studies now show. Early education can however have a positive impact on social development – which in turn feeds into the likelihood of graduation from school and university as well as being associated with lower crime rates. In short, attending preschool can have positive effects on later achievement in life, but not necessary on academic skills.

Too much academic pressure may even cause problems in the long run. A study published in January 2022 suggested that those who attended a state-funded preschool with a strong academic emphasis, showed lower academic achievements a few years later, compared to those who had not gained a place.

This chimes with research on the importance of play-based learning in the early years. Child-led play-based preschools have better outcomes than more academically focussed preschools, for example.

One 2002 study found that "children's later school success appears to have been enhanced by more active, child-initiated early learning experiences", and that overly formalised learning could have slowed progress. The study concluded that "pushing children too soon may actually backfire when children move into the later elementary school grade".

Similarly, another small study found that disadvantaged children in the US who were randomly assigned to a more play-based setting had lower behavioural issues and emotional impairments at age 23, compared to children who had been randomly assigned to a more "direct instruction" setting.

Preschool studies like these don't shed light on the impact of early literacy per se, and small studies in single locations must always be treated with care, but they suggest that how it is taught, matters. One reason why early education can result in positive social outcomes later in life may have nothing to do with the teaching at all, but with the fact that it provides childcare. This means parents can work uninterrupted and provide more income to the family home.

This means parents can work uninterrupted and provide more income to the family home.

Anna Cunningham, a senior lecturer in psychology at Nottingham Trent University who studies early literacy, argues that if a setting is too academically focused early on, it can cause the teachers to become stressed over tests and results, which can in turn affect the kids. "Of course it's not good to judge a five-year-old on their results," she says. Parental anxiety about how well their child is doing at school can also feed into this: according to a survey commissioned by an educational charity in the UK, school performance is one of parents' top concerns.

With the right support, children can learn to read in a wide range of settings, like this open-air school in Dhaka, Bangladesh (Credit: Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Later start, better outcomes?

Not everyone favours an early start. In many countries, including Germany, Iran and Japan, formal schooling starts at around six. In Finland, often hailed as the country with one of the best education system in the world, children begin school at seven.

In Finland, often hailed as the country with one of the best education system in the world, children begin school at seven.

Despite that apparent lag, Finnish students score higher in reading comprehension than students from the UK and the US at age 15. In line with that child-centred approach, the Finnish kindergarten years are filled with more play and no formal academic instruction.

Following this model, a 2009 University of Cambridge review proposed that the formal school age should be pushed back to six, giving children in the UK more time "to begin to develop the language and study skills essential to their later progress", as starting too early could "risk denting five-year-olds' confidence and causing long-term damage to their learning".

Research does back up this idea of starting later. One 2006 kindergarten study in the US showed there was improvement in test scores for children who delayed entry by one year.

Other research comparing early versus late readers, found that later readers catch up to comparable levels later on – even slightly surpassing the early readers in comprehension abilities. The study, explains lead author Sebastian Suggate, of the University of Regensburg in Germany, shows that learning later allows children to more efficiently match their knowledge of the world – their comprehension – to the words they learn. "It makes sense," he says. "Reading comprehension is language, they've got to unlock the ideas behind it."

The study, explains lead author Sebastian Suggate, of the University of Regensburg in Germany, shows that learning later allows children to more efficiently match their knowledge of the world – their comprehension – to the words they learn. "It makes sense," he says. "Reading comprehension is language, they've got to unlock the ideas behind it."

"Of course if you spend more time focusing on language earlier on, you are building a strong foundation of skills that takes years to develop. Reading can be picked up quickly but for language (vocabulary and comprehension) there's no cheap tricks. It's hard work," says Suggate. In other work looking at differing school entry ages, he found that learning to read early had no discernible benefits at age 15.

The question remains that if reading ability is not improved by learning early, then why start early? Individual variation in reading appetite and ability are one important aspect.

"Children are hugely different in terms of their foundational skills when they start school or start learning to read," explains Cunningham. In her study of Steiner-educated children, who only start formal education at about seven, she had to exclude 40% of the sample as the children could already read. "I think that's because they were ready for it," she says. She also found the older children were more ready "to learn the process to read in terms of their underlying language skills" because they had had three extra years of language exposure.

In her study of Steiner-educated children, who only start formal education at about seven, she had to exclude 40% of the sample as the children could already read. "I think that's because they were ready for it," she says. She also found the older children were more ready "to learn the process to read in terms of their underlying language skills" because they had had three extra years of language exposure.

World Book Day celebrates the joy of reading, and has become increasingly popular. Here, British Olympic Gold Medallist Greg Rutherford joins in (Credit: Matt Alexander/PA Wire)

Studies also show that reading ability is more closely linked to a child's vocabulary than to their age, and that spoken language skills are a high predictor of later literary skills. However, we know that many children who enter school are behind on their language skills, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Some argue that formal teaching allows these children to access the support and skills that others may pick up informally at home. This line of thinking is espoused by UK educational authorities, who say that teaching reading early to those behind on their spoken language is "the only effective route to closing this [language ability] gap".

This line of thinking is espoused by UK educational authorities, who say that teaching reading early to those behind on their spoken language is "the only effective route to closing this [language ability] gap".

Others favour the opposite approach, of immersing children in an environment where they can enjoy and develop their language comprehension, which is after all central to reading success. This is exactly what a playful learning setting helps encourage. "The job of teaching is to assess where your children are and give them the most appropriate teaching related to their level of development," says Wyse. The 2009 Cambridge review echoed this and stated: "There is no evidence that a child who spends more time learning through lessons – as opposed to learning through play – will 'do better' in the long run."

Cunningham, whose daughter has also recently started learning to read, has a reassuringly generous view of the ideal reading age: "It doesn't matter whether you start to read at four or five or six as long as the method they are taught is a good, evidenced method. Children are so resilient they will find opportunities to play in any context."

Children are so resilient they will find opportunities to play in any context."

Our obsession with early literacy appears to be somewhat unfounded, then – there's no need, nor clear benefit of rushing it. On the other hand, if your child is starting early, or shows an independent interest in reading before their school offers it, that's fine too, as long as there is plenty of opportunity to down tools and have fun along the way.

* Melissa Hogenboom is the editor of BBC Reel. Her book, The Motherhood Complex, is out now. She is @melissasuzanneh on Twitter.

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

What is the best age to learn to read?

0.00 aug. rating ( 0 % score) - 0 votes

What is the best age to learn to read? Modern parents ask themselves this question very early, because the fashion for early development is so strong. True, training and development are completely different things, but most parents and teachers do not see this difference. So. Modern methods of early development vying with each other say that after three it will be too late. In this regard, parents are thinking about how to buy a magical a miracle tablet a miracle method that will make a child read easily, playfully, and it's not too late.

It is quite possible to teach a child to read at almost any age, even at the age of one and a half or two years. But the younger the child, the more laborious and difficult it is. The younger the child, the less ready he is for this skill and the more difficult it is to interest him, and most importantly, the more difficult it is to maintain interest in reading for a long time.

It often happens that a two-year-old suddenly becomes interested in letters. Moms rejoice and decide that this is the best time to start, because the child has become interested. A week later, the baby begins to be interested in something else and the letters are already losing their attractiveness for him. But mothers decide to bring the matter to an end. And often ends in tears and conflicts. And then children up to 5-6 years old refuse to even look in the direction of letters and words.

Experience has shown that it is premature to start learning to read before the age of three. At three or three and a half years, when the child has already passed the well-known age crisis, he becomes calmer, more interested in studies, more stable in his own interests. Therefore, it is better to start after three years. And even better - already closer to four. And, contrary to a quote from a famous book, it is not too late to learn to read. And most importantly, kids under three years old have a lot of interesting things that they can learn and try. And then, later, there will be no time for that.

Therefore, it is better to start after three years. And even better - already closer to four. And, contrary to a quote from a famous book, it is not too late to learn to read. And most importantly, kids under three years old have a lot of interesting things that they can learn and try. And then, later, there will be no time for that.

Moreover, even later, after 4 years, it's not too late! In fact, teaching a 4-5 year old is many times easier than a three year old. And this must also be taken into account.

True, according to this logic, it turns out that the later, the better. But this is not true. Because after the child is already 6 years old, and he has not learned before and did not even try, learning is more difficult. The child begins to subconsciously struggle with mastering the skill according to the principle “I lived without it and I will continue to live”. His brain is already accustomed to a completely different activity and learning is very slow.

Therefore, we can conclude that the period from 3-3. 5 years to 5-5.5 is optimal for learning to read. The child is still interesting, but not difficult.

5 years to 5-5.5 is optimal for learning to read. The child is still interesting, but not difficult.

It is only important to remember that, of course, children should be taught to read only in the game.

Classes in the "School of Reading for Toddlers" are based on games!

What is special about this school?

- We are just playing! No learning "behind the desk"!

- We are engaged with joy, the tasks are structured in such a way as to really captivate the child with the game.

- All tasks are ready: download, print and play! If there is no printer, it will be possible to write or draw by hand.

- All you need is just to play the tasks. No tests, no checks, no expectations.

- You are just playing, and the child “suddenly” starts reading, and this will be an amazing discovery for him and a great joy for you!

>>Learn more!

To get an idea about school , download the open lesson with sample tasks.

Lena Danilova's blog "Live today!"

By clicking on the "Subscribe" button, I give the administration of the site Danilova.ru my consent to the processing of my personal data. The confidentiality of personal data is protected in accordance with the legislation of the Russian Federation.

0.00 avg. rating ( 0 % score) - 0 votes

When to start learning to read? At what age should children be taught to read? At 4 years old? 5 years? 6?

The answer to this question depends on the interpretation of the word "better". Who is better? What is better for?

From the point of view of the school methodologist, it is better to start in September, provided that the child is six and a half years old. At this age, a group of thirty children can already be seated at their desks and persuaded not to move for forty-five minutes. The author of the commercial method, of course, would like to start as early as possible: from the age of two, when it comes to classes in the kindergarten group (Zaitsev's method), or even from infancy, if home schooling is meant (adaptation by Lena Danilova). The younger the child, the more perplexed questions parents have, the longer the training lasts, the higher the profit.

The author of the commercial method, of course, would like to start as early as possible: from the age of two, when it comes to classes in the kindergarten group (Zaitsev's method), or even from infancy, if home schooling is meant (adaptation by Lena Danilova). The younger the child, the more perplexed questions parents have, the longer the training lasts, the higher the profit.

Well, when is the best time for me to start if I don't trust the school and I'm not in a hurry to sign up as a client for entrepreneurs?

First of all, I must decide on my goals. Why should my child be able to read? Certainly not to touch my grandmother (my mother-in-law) when she comes to visit us. The ability to read is necessary precisely in order to read - in order to use books. This means many hours of sitting at the table with all the notorious loads on the eyes and spine. Would I like my child to be a book reader by three, four, five? Of course no!

The terminology needs to be further clarified. When they say: “Oh, just think, he already knows how to read!” - they usually mean that the child can only parse words into warehouses. An adult who has exactly the same reading skills would be said to be illiterate. Such vagueness of terminology is very beneficial for entrepreneurs.

When they say: “Oh, just think, he already knows how to read!” - they usually mean that the child can only parse words into warehouses. An adult who has exactly the same reading skills would be said to be illiterate. Such vagueness of terminology is very beneficial for entrepreneurs.

Do you want your child to be able to read? No problem! - proudly declares Zaitsev. “According to our method, children learn to read in several lessons.

No doubt, children learn to read - yes, only in warehouses - but it's not that interesting!

Mastering reading skills can be conditionally represented as a ladder consisting of two steps. Those who are on the first step are able to parse words into warehouses. Those who have climbed the second step are able to recognize words instantly, “with one touch of the eye”; they read fluently, in an adult way.

The question is: which step is more difficult to overcome? Yes, of course, the second! Climbing from the first step to the second is a long, hard work that can only be done on your own. And so far only one method has been invented here: you need to sit down for books - and read, read, read until every common word in the Russian language has been read hundreds and thousands of times.

And so far only one method has been invented here: you need to sit down for books - and read, read, read until every common word in the Russian language has been read hundreds and thousands of times.

If I want to calculate the situation at least two moves ahead, then it makes sense to ask the question: “When will the child be physiologically ready to overcome the second step? When will his brain, eyes, spine be ripe for long, concentrated work, associated (let's be realistic) with certain health risks?

I think about the age of six. However, I am not an expert in child physiology. I proceed, rather, from pragmatic considerations. On the one hand, we would not like to hurry too much, and on the other hand, public education is arranged in such a way that the more a child knows before entering school, the better. Beginning in first grade, students are so heavily loaded with meaningless assignments that they hardly have time to learn anything useful.

Thus, the optimal age to start learning to read is easy to determine by the formula:

Six years minus the time to overcome the first stage.

One paradoxical consequence follows from this formula: the more effective the technique that allows you to master reading in warehouses, the later you should start. For example, I am not sure that I can prepare a child for the second stage in a few lessons. However, even with the most unhurried approach, one year is enough for me for sure.

The final conclusion is obvious. I will not teach my younger children to read until they are five years old. (Due to my initial inexperience, my first child had to learn this science from the age of two, the second child from four. But it was only at the age of seven that both finally began to read thick books with pleasure.)

I don’t want to say that an earlier start is harmful. It's not harmful - it's useless. There is probably only one truly worthy reason why you can start early. This is when the initiative comes from the child. This is when he himself persistently asks: “Mom, what is this letter? Dad, how do you pronounce this word? Dodging such questions would, of course, be wrong.

All other reasons I would probably call irrational. This includes, for example, parental impatience. In principle, such an understandable feeling... Since the beginning of pregnancy, 's parents have been impatiently waiting for the birth of a baby. There is fear behind the impatience. Is everything good with him? Are the arms and legs in place? Are there as many fingers as needed?.. And now the child is born. All is well. The arms and legs are in place. How many fingers do you need? But the fear of parents does not leave. How will it develop further? Is everything okay with the head? Will he be smart? Will it be good to study? Such burning questions! And it is so unbearable to wait - to wait for many more years before school teachers give their verdict on this matter! Parents can't wait . They want the child to take his first step as early as possible, to say his first word as early as possible, to read his first book as early as possible.

Well then. If it’s completely unbearable, then you can start teaching a child from the very first months of life.