Average age kids learn to read

Learning to read: What age is the "right" age?

Some kids just “get” how to read, while others struggle for years. When should parents worry?

Photo: Tony Lanz

Jenna Levinson* was reading fluently by the age of four.

“I remember I was wearing an Earth Day T-shirt with a picture of a globe on it,” recalls her mom, Stephanie. “And she said to me, ‘Why does your shirt say, “Love your mother?”’ I was pretty surprised. We hadn’t ever tried to teach her to read.”

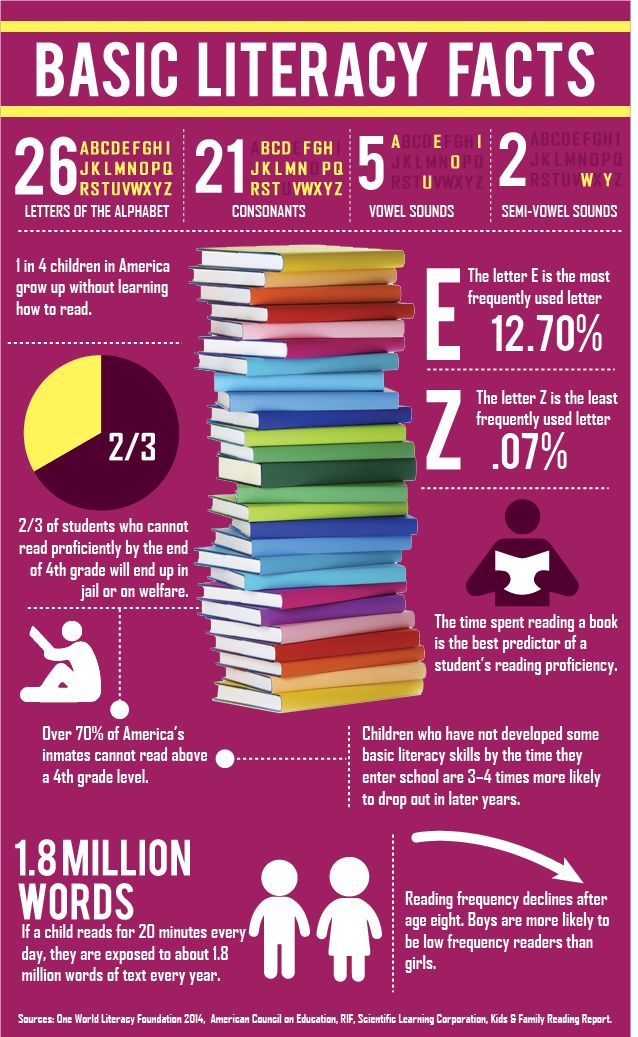

Jenna’s younger sister, Sadie, has taken a decidedly different route toward literacy. Well into second grade, the seven-year-old “is just starting to be able to read a simple book out loud to me,” says Levinson, who lives in Winnipeg. “She’s progressing, but she still guesses a lot, struggles with vowel sounds, mixes up her Ds and Bs—things like that.”

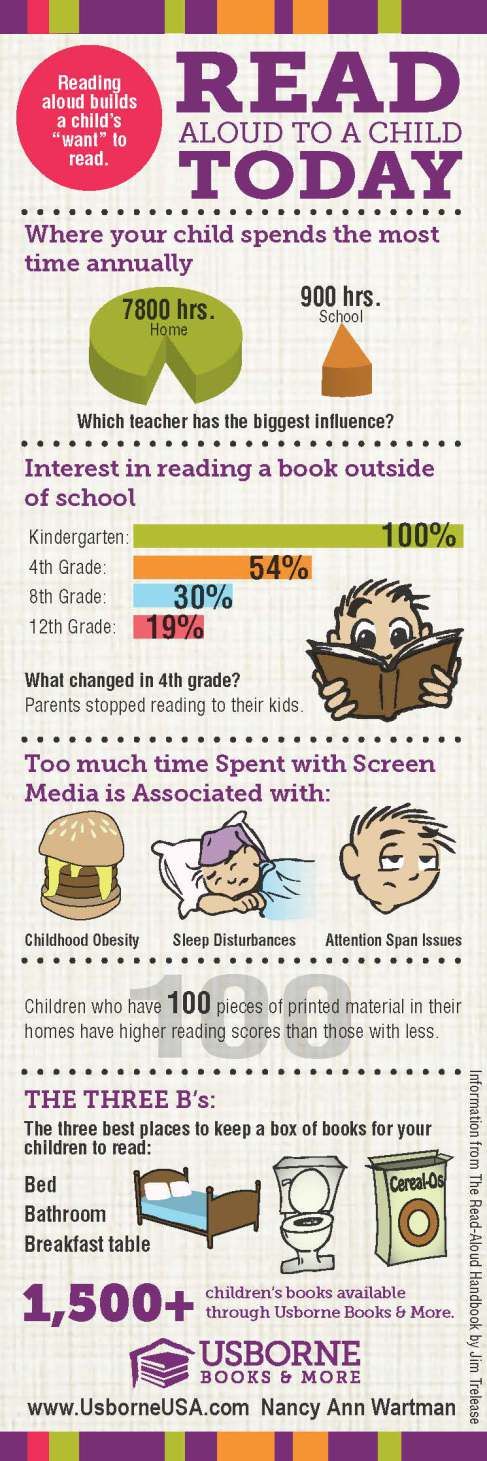

Levinson says she’s read constantly to both kids since babyhood. “Jenna would listen to as many books as you wanted to read to her, and Sadie would grab the book and throw it across the room. ” Watching her daughters’ radically different approaches to literacy has left her, like many parents, wondering if there’s something innate that helps some kids pick up the ability to read easily and if there’s a “right” age to learn how to read.

9 best educational websites for kids (that are actually fun, too!)

Experts say no. “The brain isn’t naturally hard-wired to read in the way that it’s wired to speak or listen,” explains Bev Brenna, an education professor at the University of Saskatchewan who specializes in literacy education. There simply isn’t one age where kids can or should be reading—despite the deeply ingrained North American ideal that children learn to read in first grade, around age six.

“There’s actually no evidence to support that belief,” says Carol Leroy, director of the Reading and Language Centre at the University of Alberta. Attaining literacy is, rather, a very gradual process. It begins with infants playing with or even chewing on board books and being read to by parents or caregivers, and continues through to independent reading. While some kids, like Jenna, seem to pick it up on their own, most need to be taught how to make sense of those squiggles on the page. And some kids take longer than others to do so.

While some kids, like Jenna, seem to pick it up on their own, most need to be taught how to make sense of those squiggles on the page. And some kids take longer than others to do so.

Home-schooler Sue Holloway, for example, tried to teach her older son, Walker, when he was seven. “I got a ‘learning to read’ book, and he hated it. We fought about it a lot, and I finally just let it go,” says Holloway, who lives in South Gillies, Ont. Two years later, Walker began reading independently. “I have no idea how he figured it out, but he did, and now he really loves to read and does so every night.” Holloway’s younger son, Rowan, is still trying to get the hang of reading at the age of eight. But home-schooling gives them the luxury of being able to learn at their own pace. And Holloway says she often hears of home-schooled kids learning to read at about age nine—and going on to complete high school and attend university without any negative effects.

For kids who attend school, the stakes are different. Even if there’s no biologically correct age to read, students who aren’t reading according to a school’s timetable can fall behind and experience distress as a result. If the gap between slower readers and their peers isn’t identified and dealt with early on, it can widen over time and lead to other issues.

“Kids who aren’t reading can’t participate, because they don’t understand the basic mechanics and, therefore, can’t understand what the other children are doing,” says Leroy. And if you don’t understand the basics, you can’t point out the last word of the sentence when asked or circle all the words that start with S. In gym class, a slow reader may struggle to figure out which sign to line up behind if he wants to play soccer or skip. “Around grade two or three, they start to become really conscious of their reading—they can

lose their confidence, stop taking risks, become afraid of being teased,” says Leroy. “That’s where we start to get behaviour issues; some kids will withdraw or stir up trouble to avoid reading, because it’s so painful for them.”

“That’s where we start to get behaviour issues; some kids will withdraw or stir up trouble to avoid reading, because it’s so painful for them.”

The effects can last well beyond grade school, says Chicago literacy expert Timothy Shanahan, author of the blog Shanahan on Literacy. A British study released in 2013, for example, showed that children’s literacy and math levels at age seven were predictive of their overall earnings at the age of 42.

Fortunately, says Brenna, today’s teachers are trained to recognize and accommodate the needs of kids at all levels, so everyone can learn. They might use strategies like choral reading—where all the kids in the class read out loud together—or reading back stories they’ve dictated to the teacher.

Any classroom will typically contain students with a wide range of reading levels, says Leroy. The rule of thumb, she says, is to double the grade to get the range. “So in third grade, there could be six years’ difference between the lowest and the highest level of readers in the class. Similarly, in a first-grade classroom, there’s bound to be at least one kid without any reading skills and at least one kid who’s reading independently.”

Similarly, in a first-grade classroom, there’s bound to be at least one kid without any reading skills and at least one kid who’s reading independently.”

So what’s a parent of a late reader to do? Be vigilant, but don’t panic, say all three experts. If you think your child is struggling with reading or isn’t getting the help he or she needs, says Shanahan, the first step is to talk to the teacher—don’t hesitate to bring up the subject and brainstorm strategies for supporting reading. If you’re still concerned after meeting with the teacher, says Brenna, ask for a referral to another member of the school’s or the board’s team, such as a special education teacher or speech-language pathologist. “A team approach is often very helpful in developing an action plan for literacy, and most students respond well to additional supports at the school level,” says Brenna. Your child’s doctor, as well as speech-language pathologists and educational psychologists, can also help to create a support plan.

Above all, say the experts, don’t push, because it will turn reading into a power struggle. “The biggest priority has to be how the child feels about reading,” says Leroy. “So entice kids by making it fun.” And be reassured by the fact that many kids who are slow to pick it up become lifelong book lovers.

If your child isn’t reading at grade level by the end of grade three, Leroy says you should investigate whether she is struggling with other subjects, create a plan with the teacher and discuss having a thorough assessment. In some cases, the delay may be caused by an underlying condition.

“I kept hearing, ‘She’s going at her own pace,’ or ‘She’s behind, but I’m not worried yet,’” recalls Toronto mom Jessica Miller* about her daughter Sabrina’s lagging reading skills in first and second grade. When Sabrina’s school didn’t take action by the end of grade two, Miller and her husband paid to have Sabrina tested privately—and found out that she is dyslexic. Miller’s first grader, Gavin, isn’t showing any signs of delayed reading, but she’s adamant that she will have him tested at the first sign of any trouble: “I’m not falling for, ‘He’s in the range.’”

Miller’s first grader, Gavin, isn’t showing any signs of delayed reading, but she’s adamant that she will have him tested at the first sign of any trouble: “I’m not falling for, ‘He’s in the range.’”

Levinson, meanwhile, is doing whatever she can to make reading enjoyable for Sadie. “She loves making up stories and dictating them to me, and will happily read those out loud,” she says. “We get library books on whatever she’s interested in—mummies, wizards, jewellery making. We’ve done treasure hunts at the grocery store and word searches. I have literally done reading time with her sitting on my shoulders.”

That’s the right approach, says Leroy. “If a kid wants to stand on his head while he reads—if he wants you to stand on your head while he reads—do it. With children this age, we forget how much they’re in control of their own learning already.”

Online resources:

ABRACADABRA is a free language and reading program developed at Concordia University in Montreal. Kids can use the “light” version, which contains activities for teaching comprehension and fluency. abralite.concordia.ca

Kids can use the “light” version, which contains activities for teaching comprehension and fluency. abralite.concordia.ca

Saskatchewan Reads, created by Saskatchewan’s provincial reading team, is a user-friendly site with strategies and resources for teaching primary students to read. saskatchewanreads.wordpress.com

Read more:

15 creative ways to get kids reading (that really work!)

Essential tips for teaching kids to read

Stay in touch

Subscribe to Today's Parent's daily newsletter for our best parenting news, tips, essays and recipes.- Email*

- CAPTCHA

- Consent*

Yes, I would like to receive Today's Parent's newsletter. I understand I can unsubscribe at any time.**

FILED UNDER: app-school-age Books Family Literacy Day June 2015 Mcdonalds2018 Reading

Reading Milestones (for Parents) - Nemours KidsHealth

Reviewed by: Cynthia M. Zettler-Greeley, PhD

Zettler-Greeley, PhD

Nemours BrightStart!

en español Hitos en la lectura

This is a general outline of the milestones on the road to reading success. Keep in mind that kids develop at different paces and spend varying amounts of time at each stage. If you have concerns, talk to your child's doctor, teacher, or the reading specialist at school. Getting help early is key for helping kids who struggle to read.

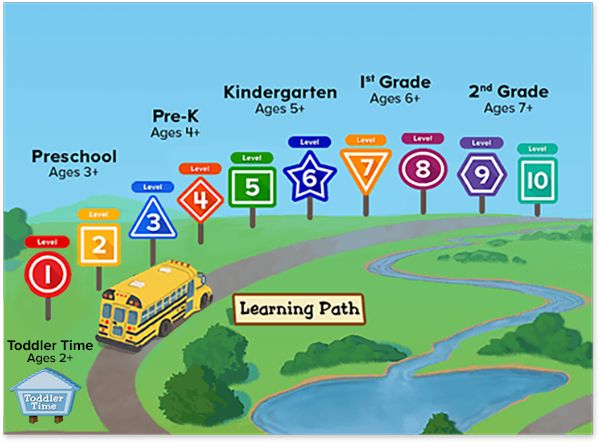

Parents and teachers can find resources for children as early as pre-kindergarten. Quality childcare centers, pre-kindergarten programs, and homes full of language and book reading can build an environment for reading milestones to happen.

Infancy (Up to Age 1)

Kids usually begin to:

- learn that gestures and sounds communicate meaning

- respond when spoken to

- direct their attention to a person or object

- understand 50 words or more

- reach for books and turn the pages with help

- respond to stories and pictures by vocalizing and patting the pictures

Toddlers (Ages 1–3)

Kids usually begin to:

- answer questions about and identify objects in books — such as "Where's the cow?" or "What does the cow say?"

- name familiar pictures

- use pointing to identify named objects

- pretend to read books

- finish sentences in books they know well

- scribble on paper

- know names of books and identify them by the picture on the cover

- turn pages of board books

- have a favorite book and request it to be read often

Early Preschool (Age 3)

Kids usually begin to:

- explore books independently

- listen to longer books that are read aloud

- retell a familiar story

- sing the alphabet song with prompting and cues

- make symbols that resemble writing

- recognize the first letter in their name

- learn that writing is different from drawing a picture

- imitate the action of reading a book aloud

Late Preschool (Age 4)

Kids usually begin to:

- recognize familiar signs and labels, especially on signs and containers

- recognize words that rhyme

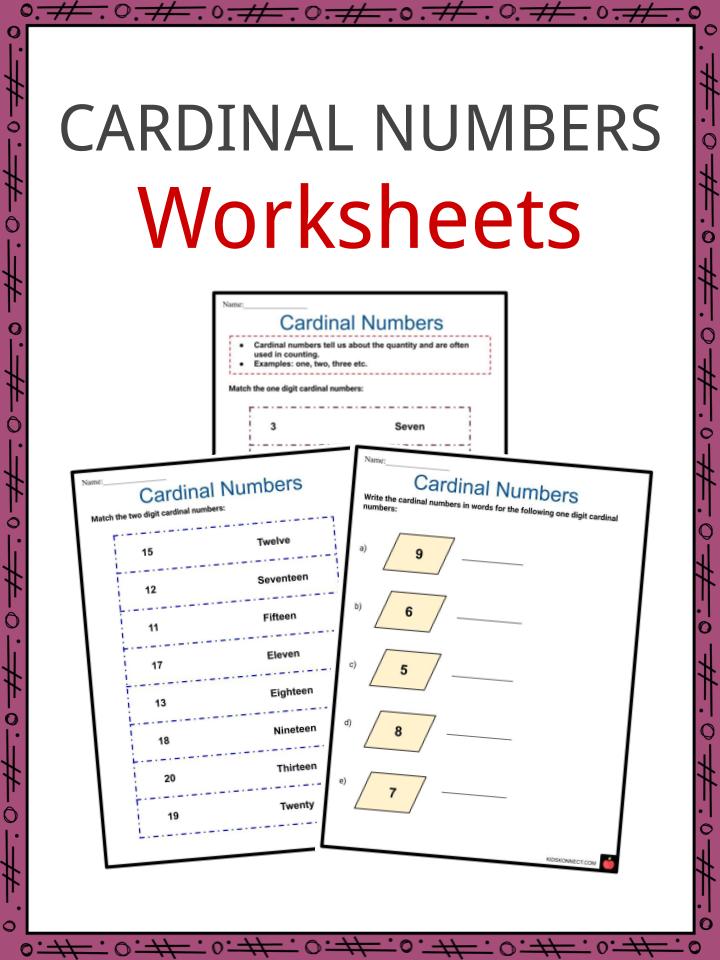

- name some of the letters of the alphabet (a good goal to strive for is 15–18 uppercase letters)

- recognize the letters in their names

- write their names

- name beginning letters or sounds of words

- match some letters to their sounds

- develop awareness of syllables

- use familiar letters to try writing words

- understand that print is read from left to right, top to bottom

- retell stories that have been read to them

Kindergarten (Age 5)

Kids usually begin to:

- produce words that rhyme

- match some spoken and written words

- write some letters, numbers, and words

- recognize some familiar words in print

- predict what will happen next in a story

- identify initial, final, and medial (middle) sounds in short words

- identify and manipulate increasingly smaller sounds in speech

- understand concrete definitions of some words

- read simple words in isolation (the word with definition) and in context (using the word in a sentence)

- retell the main idea, identify details (who, what, when, where, why, how), and arrange story events in sequence

First and Second Grade (Ages 6–7)

Kids usually begin to:

- read familiar stories

- "sound out" or decode unfamiliar words

- use pictures and context to figure out unfamiliar words

- use some common punctuation and capitalization in writing

- self-correct when they make a mistake while reading aloud

- show comprehension of a story through drawings

- write by organizing details into a logical sequence with a beginning, middle, and end

Second and Third Grade (Ages 7–8)

Kids usually begin to:

- read longer books independently

- read aloud with proper emphasis and expression

- use context and pictures to help identify unfamiliar words

- understand the concept of paragraphs and begin to apply it in writing

- correctly use punctuation

- correctly spell many words

- write notes, like phone messages and email

- understand humor in text

- use new words, phrases, or figures of speech that they've heard

- revise their own writing to create and illustrate stories

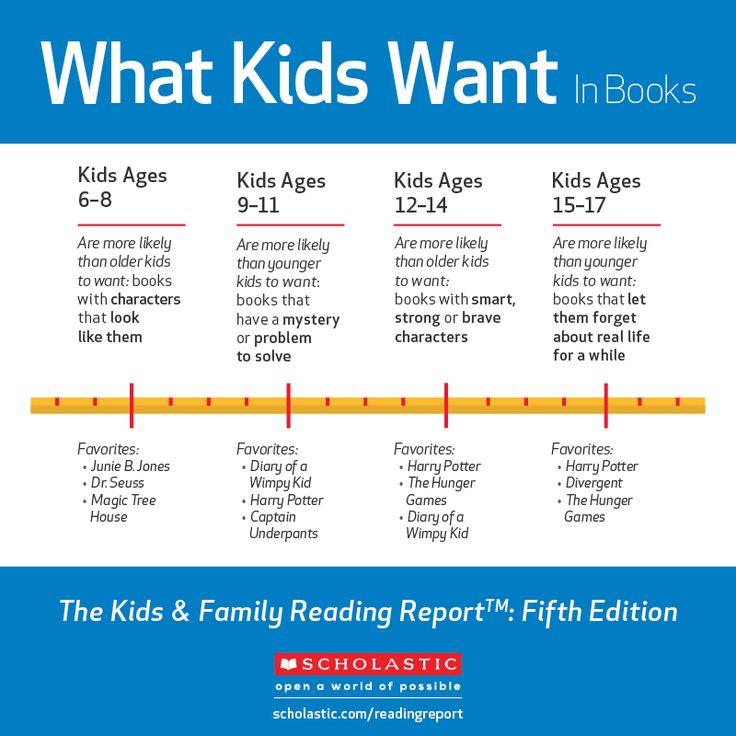

Fourth Through Eighth Grade (Ages 9–13)

Kids usually begin to:

- explore and understand different kinds of texts, like biographies, poetry, and fiction

- understand and explore expository, narrative, and persuasive text

- read to extract specific information, such as from a science book

- understand relations between objects

- identify parts of speech and devices like similes and metaphors

- correctly identify major elements of stories, like time, place, plot, problem, and resolution

- read and write on a specific topic for fun, and understand what style is needed

- analyze texts for meaning

Reviewed by: Cynthia M. Zettler-Greeley, PhD

Zettler-Greeley, PhD

Date reviewed: May 2022

Is it necessary to teach a child to read before school and how is this related to the further reading literacy of children?

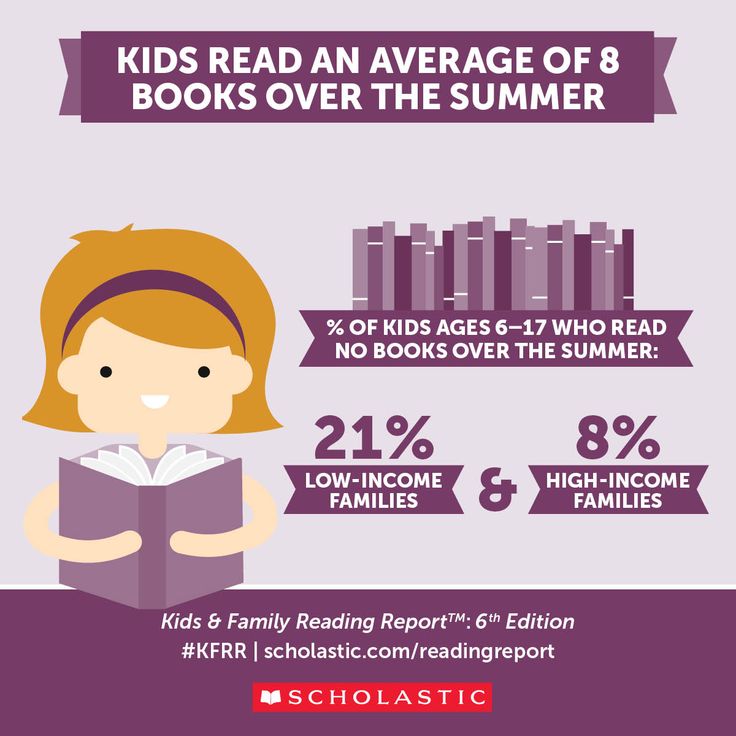

A study by our colleagues in the Laboratory showed that educational inequality manifests itself even before school. This is due to how differently they deal with children in families with different levels of cultural capital.

firestock

Many schools now have an unwritten rule that children must be able to read by the first grade. But visiting kindergartens in our country is not mandatory. In addition, the problem of their availability is also far from being solved everywhere. Therefore, this difficult task - the formation of early reading literacy - falls on the shoulders of parents.

Andrey Zakharov and Anastasia Kapuza, members of the International Laboratory for Education Policy Analysis, decided to take a closer look at this issue and find out exactly how parents teach children to read in different families and what results these efforts bring.

Kapuza Anastasia Vasilievna

International Laboratory for Education Policy Analysis: Intern Researcher

We conducted a study based on the data of the international monitoring PIRLS, which took place in 2011. It was attended by 4461 fourth-graders from 202 Russian schools. We were interested in how the level of literacy of children at school entry and in the 4th grade is associated with the cultural capital of the family, attendance at kindergarten, and various reading teaching practices used by parents with different levels of education.

How parents teach their children to read before school

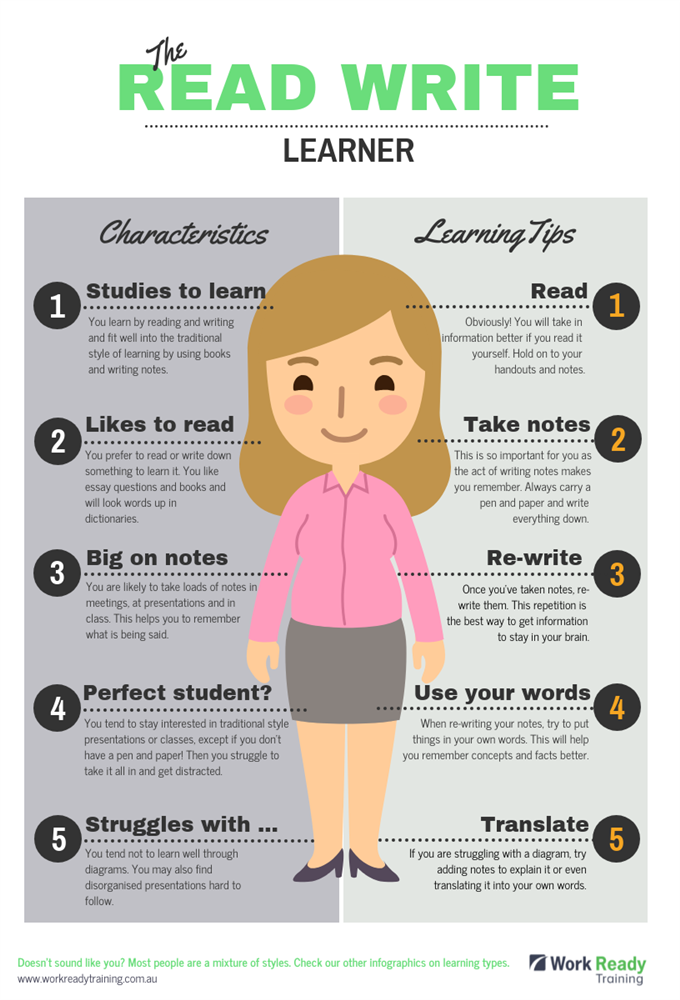

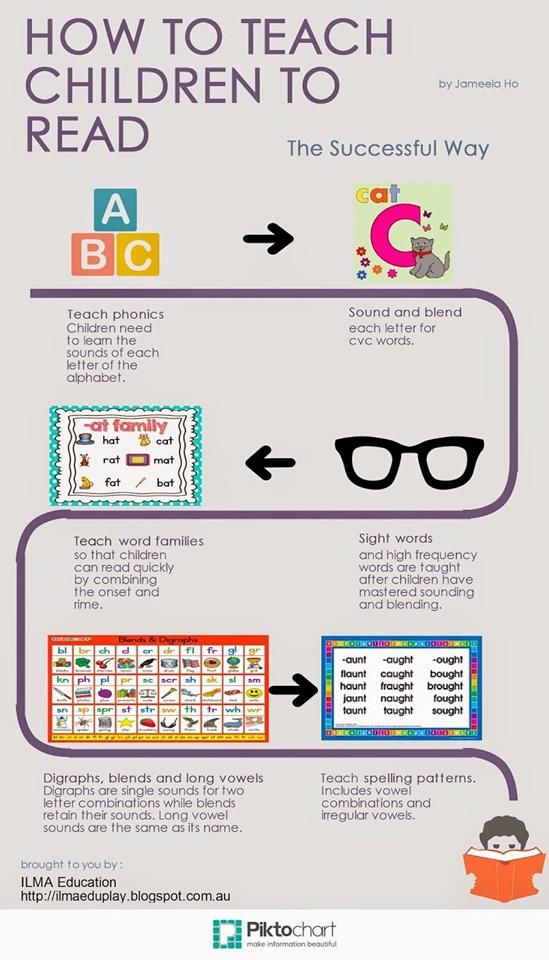

Ways of teaching reading can be divided into formal and informal. Formal ones are more focused on the mechanics of the reading process. That is, on the perception and pronunciation of letters, syllables and words. For example, this is learning the alphabet or playing with words. In informal practices, more attention is paid to the comprehension of texts - this is the joint reading and discussion of books.

Andrey Zakharov

Deputy Head of the International Laboratory for Education Policy Analysis

In general, parents with higher education are more likely to start teaching their children to read before school. Moreover, strategies for engaging with children are also related to the level of education of parents. The longer a child goes to kindergarten, the more often parents without higher education work with him. That is, such children are taught to read both in the garden and at home. At the same time, parents more often use the whole diverse set of practices: both formal and informal. We called this approach “reinforcement strategy” . We assume that this strategy is a response to requests from kindergarten teachers who encourage parents to engage with their children.

Parents with higher education use “compensation strategy” . In such families, they are more involved with children if they do not go to kindergarten. Moreover, such parents use predominantly informal practices - they try to instill in the child an interest in reading, are engaged in language development and general education.

Moreover, such parents use predominantly informal practices - they try to instill in the child an interest in reading, are engaged in language development and general education.

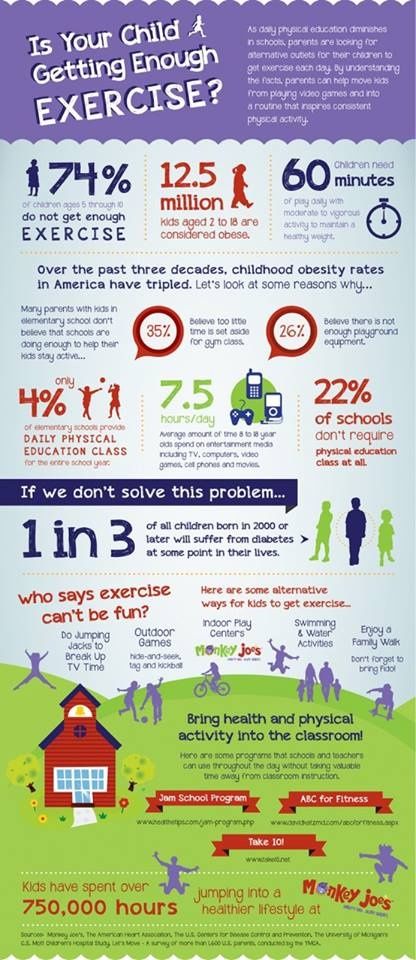

The more often parents work with their children before school, the higher the level of children's reading literacy - both when entering the first grade, and later, in the 4th grade. For children from families with a large amount of cultural capital, an increase in the level of reading literacy is associated with the use of informal practices by parents. But parents without higher education can apply any practice - the results of children will only get better.

Reading Literacy and Kindergarten

A child's progress in reading also depends on whether he attended kindergarten. This is very important for families with little cultural capital. The longer a child goes to kindergarten, the better he reads when entering school. This is due to the combined effect of the joint efforts of teachers and parents.

But for children from families with a large amount of cultural capital, the duration of kindergarten attendance is not critical for their level of reading literacy.

- The compensation strategy probably works, the researchers conclude. - Parents with higher education compensated for the absence of a kindergarten by studying at home.

As a result, children from families with low cultural capital, who did not go to kindergarten, find themselves in the most difficult situation. They are less likely to learn to read by grade 1, because neither teachers nor parents teach them. Such children are more likely to lag behind their peers in the classroom at school.

Parent support for children's reading in grade 4

Of course, schools do not leave children with poor reading skills unattended. They are trying to somehow influence families. Parents without higher education are more likely to join classes with children in the 4th grade. Apparently, under the pressure of the school (on average, students from such families read worse), such parents begin to pay more attention to reading to children and discussing what they have read with them. But in 4th grade it may be too late for that.

But in 4th grade it may be too late for that.

- We were surprised to see that frequent activities with children in the 4th grade were negatively associated with their reading literacy, the researchers say. - At first they didn't even believe it, so they made the same analysis for other PIRLS member countries. In many countries, the trend has repeated. This is explained by the fact that by the fourth grade children should already be able to read, and if they have to constantly do extra work with them at this age, it means that they have problems with reading.

Outgoing train

On the example of reading, we see that the strategies for teaching children, which are chosen by parents with different amounts of cultural capital, give different results:

Parents with higher education are involved in the education of children before school. They are like passengers who come to the train in advance and take good seats. As a result, their children show a higher level of reading literacy both when they enter the 1st grade and the 4th grade. Parents without higher education prefer to delegate the function of teaching to school. They are connected only when teachers begin to draw their attention to the need to work with children. For example, when in elementary school it becomes obvious that the child is lagging behind in reading. Then the parents are somewhat belatedly connected to the education of children - as if trying to jump into the car of the departing train, but the time has already passed.

Parents without higher education prefer to delegate the function of teaching to school. They are connected only when teachers begin to draw their attention to the need to work with children. For example, when in elementary school it becomes obvious that the child is lagging behind in reading. Then the parents are somewhat belatedly connected to the education of children - as if trying to jump into the car of the departing train, but the time has already passed.

It is clear that it is impossible to force parents to take care of their children. But this state of affairs reduces the chances of successful study for a certain part of the children. If they do not read well in the primary grades, then it will be more difficult for them to learn the material in the classroom and do their homework. All this leads to the fact that the gap in educational achievements between students from different families will grow.

When to start teaching your child to read: 2 learning approaches

Reading is a fun app for teaching children to read 3-7 years old

A colorful journey into the world of a fairy tale will allow your child to immerse themselves in the study of letters and syllables. Learning to read will no longer be a boring, routine task and will become a fun adventure to save the Magic Land.

Learning to read will no longer be a boring, routine task and will become a fun adventure to save the Magic Land.

Early and timely development

Parents often ask the question: "At what age should a child be taught to read?". There are two approaches to teaching reading - early development and timely development.

According to the first, a child is an open book. His learning abilities are enormous, so you need to give him as many opportunities for development as possible in the very first years of life.

The ability to absorb information is much higher in a child's brain than in an adult ... We should be concerned not that we give the child too much information, but that it is often too little to fully develop the child.

Masaru Ibuka Japanese engineer, one of the founders of Sony; creator of innovative concepts for the upbringing and education of young children.

Evgeny Komarovsky, a well-known pediatrician, tells how to ensure the correct early development of a child. The expert emphasizes the importance of a harmonious combination of early mental development and physical development for the most comfortable growing up of your child.

According to the second approach, development must be timely. The child is able to understand and assimilate the material to which they have grown up and acquired the ability to perceive this material in the corresponding structures of the brain. And this means that the perception of information, its processing, analysis and feedback will depend on the age of the child.

One of the main concepts of child neuropsychology is the concept of developmental heterochrony.

It means that different structures of the child's brain and mental functions mature at different rates. Therefore, they reach full maturity at different stages of development. Each mental function has its own cycle, in which there are phases of rapid or slow development. If the brain center has reached the level of maturity, it will perceive the corresponding impact of the environment. If not achieved, then he will not perceive or will perceive limitedly. So there were certain "rules" of development. For example, the fact that a child goes to school at the age of about seven years.

Zheleznyak Nadezhdapsychologist, author of seminars and books on the psychology of art

How quickly a child learns to read, and what kind of child can be called a reader

The younger the child, the more time it will take him to learn to read steadily. For a 3-4 year old child, it can be several months or even a year. In fact, the child learns to read and grows with it. For a 6-7 year old child, a shorter period is needed.

In fact, the child learns to read and grows with it. For a 6-7 year old child, a shorter period is needed.

The creators of methods, manuals and owners of children's development centers often give much shorter periods - from two days to two months. At the same time, they mean "can read from a pedagogical point of view."

In pedagogy, a child is considered to be a reader if he understands the fusion of sounds, letters and can read a simple syllable: MA, NA, PA, etc. The rest is a matter of reading technique. However, there are exceptions to the rules and practices - these are brilliant children.

"Readings" - a game application that the child goes through and learns to read. Letters, warehouses (according to the Zaitsev method), short words, long words, sentences - everything in order to learn to read, the child works out in the game.

We, the creators of "Reading", have noticed that children complete the application for different periods.

Three-year-old children for a period of a year or more, 4-5 year olds on average for six months, and 6-7 year old children go through the application completely and learn to read in a month or even faster.

Children of genius and reading

It is striking in the fate of children of genius that they all begin to read very early, at the age of 2-4 years. And not just connect letters into syllables, but read books. Thus, the ability to learn to read at an early preschool age may be a sign of a child's giftedness. However, the fate of such people are often tragic. Genius coexists with ineptitude, disorder in life, problems in socialization and health problems. There are few truly brilliant people. And the more they are struck by their unfortunate destinies, early deaths. I found stories about five geniuses of the last 100 years, but only one of the five could live to old age. Here are two examples of the typical fate of geniuses.

William Sidis (1898-1944) came from a family of Russian emigrants, learned to read at the age of 2. By the age of 8, he already knew 8 languages. At the age of 7, he successfully passed the exams at Harvard, although he was actually enrolled there only at 11 years old. Professors predicted the young man an excellent career in various fields, but, contrary to expectations, William hid from reporters all his life and worked as an accountant. He died at the age of 46 from a cerebral hemorrhage.

By the age of 8, he already knew 8 languages. At the age of 7, he successfully passed the exams at Harvard, although he was actually enrolled there only at 11 years old. Professors predicted the young man an excellent career in various fields, but, contrary to expectations, William hid from reporters all his life and worked as an accountant. He died at the age of 46 from a cerebral hemorrhage.

Pasha Konoplev is an example of a brilliant child of the Soviet era. Learned to read at the age of 3. At preschool age, watching his mother, he begins to use a slide rule and solves rather complex mathematical problems. At the age of 5 he masters playing the piano himself, at 8 he studies physics. At the age of 15, he entered the faculty of the VMK at Moscow State University, and at 19to graduate school. However, after the age of 25, the psyche begins to falter and this promising young man dies at 29 from the effects of treatment with potent drugs.

Reading - a fun app for teaching children aged 3-7 to read

A colorful journey into the world of a fairy tale will allow your child to immerse themselves in the study of letters and syllables. Learning to read will no longer be a boring, routine task and will become a fun adventure to save the Magic Land.

Learning to read will no longer be a boring, routine task and will become a fun adventure to save the Magic Land.

How to know when it's time to teach your child to read and what is important to remember

Learning to read is as much a stage in a child's development as any other. All children learn to move - crawl, walk, run. They learn to interact with objects in this world, to control their body. They learn to communicate first with their mother, then with other people...

By indirect signs, we can understand that the child is ready to master some skill. For example, when a baby gets on its feet, we understand that it will soon go. We give him more opportunities to do so. However, in infancy, a person often performs the mechanisms of development laid down in him unconsciously. A child cannot fail to learn to walk, unless, of course, we are talking about a healthy child.

The older the child, the more difficult the brain works for him, the psyche and character are connected.

For example, communication in kindergarten did not go well, and even the mother, in a conversation with a friend in front of the child, confirmed that she considers her son unsociable and ... It is quite possible that the child will avoid communication.

Reading is the same. So when should you start teaching your child to read? If your child shows interest in books, looks at pictures, is interested in letters, runs his finger over the text, then it's time. You can tell him about how you read. That text is made up of sentences, sentences are made up of words, and words are made up of letters. And be sure to tell us that all people were once children and also learned to read. And then reading also seemed difficult to them, but gradually, reading more and more, adults got used to it so much that now they don’t notice individual letters, but they read interesting stories in books and magazines, that’s how I tell you now ...

It is impossible to accurately answer the question: "When do children learn to read?". At whatever age the child shows readiness - move gradually. Above, we talked about the fact that the child may have difficulties. Therefore, do not put pressure on him, do not show impatience, because this may affect the child's perception of learning in general and his impression of the learning process. The last thing we want is for the child to feel uncomfortable after our classes, so that the classes do more harm than good - and these are quite real situations when children remember for the rest of their lives that reading is difficult and therefore boring.

At whatever age the child shows readiness - move gradually. Above, we talked about the fact that the child may have difficulties. Therefore, do not put pressure on him, do not show impatience, because this may affect the child's perception of learning in general and his impression of the learning process. The last thing we want is for the child to feel uncomfortable after our classes, so that the classes do more harm than good - and these are quite real situations when children remember for the rest of their lives that reading is difficult and therefore boring.

Natalia Sosnina

Co-author and methodologist of the Readings educational application. Since 2016, together with her husband and children, they have been developing a game to make learning to read interesting and understandable. The application is based on N.A. Zaitsev. In her free time she likes to spend time with her family and travel.

Learn more about Natalia on VK, Instagram and the Readings YouTube channel.