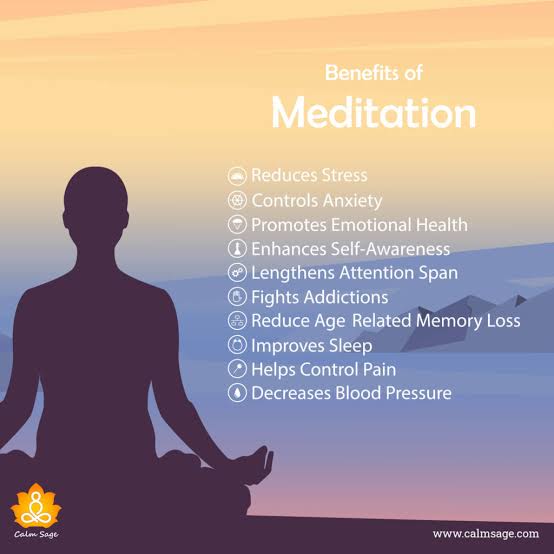

Benefits of meditation and mindfulness

What are the benefits of mindfulness?

Welcome to ‘CE Corner'

"CE Corner" is a quarterly continuing education article offered by the APA Office of CE in Psychology. This feature will provide you with updates on critical developments in psychology, drawn from peer-reviewed literature and written by leading psychology experts. "CE Corner" appears in the February 2012, April, July/August and November issues of the Monitor.

To earn CE credit, after you read this article, purchase the online exam.

Upon successful completion of the test (a score of 75 percent or higher), you can print your CE certificate immediately. APA will immediately send you a "Documentation of CE" certificate. The test fee is $25 for members; $35 for nonmembers. The APA Office of CE in Psychology retains responsibility for the program. For more information, call (800) 374-2721, ext. 5991.

Overview

CE credits: 1

Exam items: 10

Purchase the online exam

Learning objectives:

As a result of having participated in this continuing education program, participants will be able to:

- Identify the definition of mindfulness and what practices develop mindfulness.

- Identify at least four benefits of the effect of mindfulness meditation on therapists and therapist trainees.

- Understand the relationship between therapists' mindfulness and psychotherapy outcome based on the research to date.

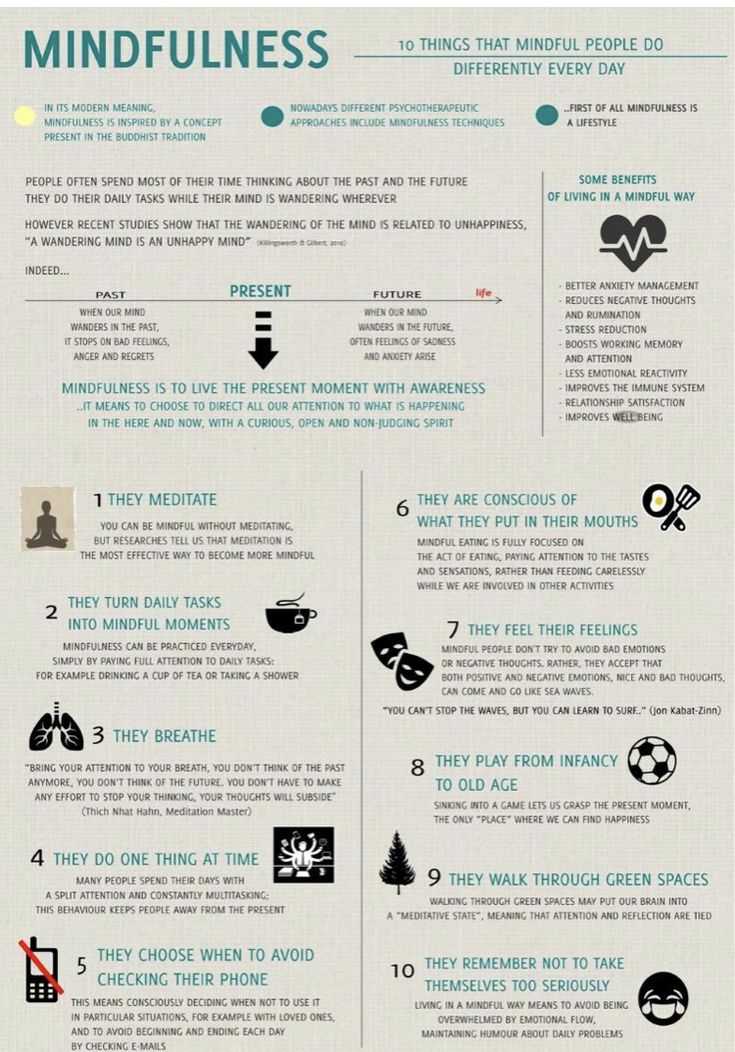

Mindfulness has enjoyed a tremendous surge in popularity in the past decade, both in the popular press and in the psychotherapy literature. The practice has moved from a largely obscure Buddhist concept founded about 2,600 years ago to a mainstream psychotherapy construct today.

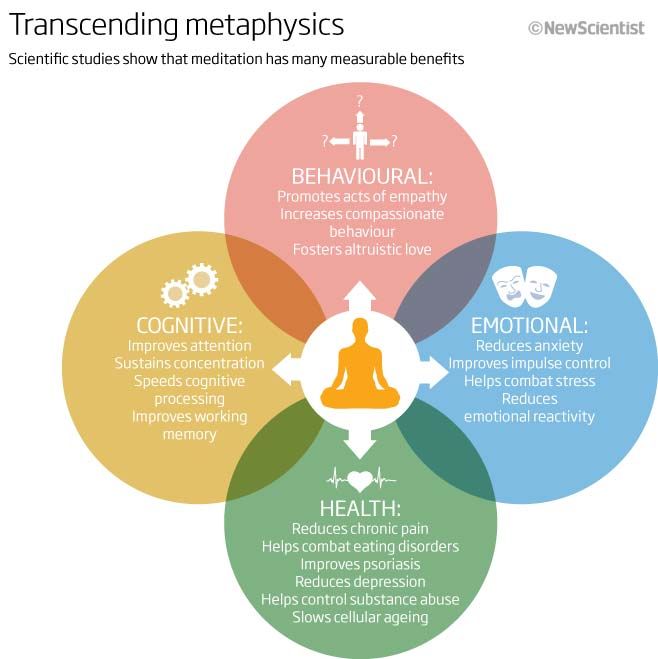

Advocates of mindfulness would have us believe that virtually every client and therapist would benefit from being more mindful. Among its theorized benefits are self-control, objectivity, affect tolerance, enhanced flexibility, equanimity, improved concentration and mental clarity, emotional intelligence and the ability to relate to others and one's self with kindness, acceptance and compassion.

But is mindfulness as good as advertised? This article offers an overview of the research on mindfulness and discusses its implications for practice, research and training.

Empirically supported benefits of mindfulness

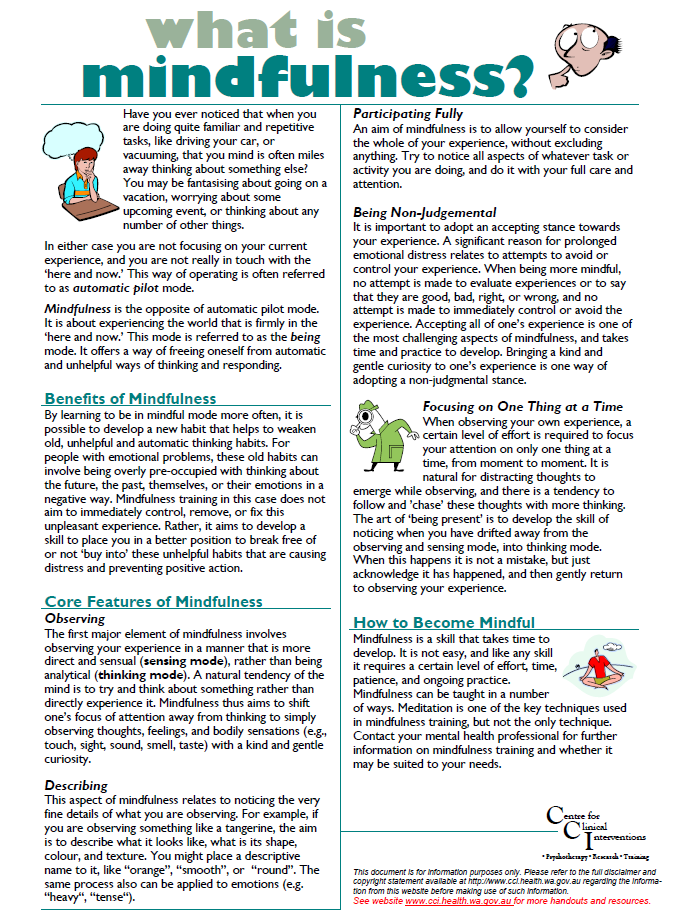

The term "mindfulness" has been used to refer to a psychological state of awareness, the practices that promote this awareness, a mode of processing information and a character trait. To be consistent with most of the research reviewed in this article, we define mindfulness as a moment-to-moment awareness of one's experience without judgment. In this sense, mindfulness is a state and not a trait. While it might be promoted by certain practices or activities, such as meditation, it is not equivalent to or synonymous with them.

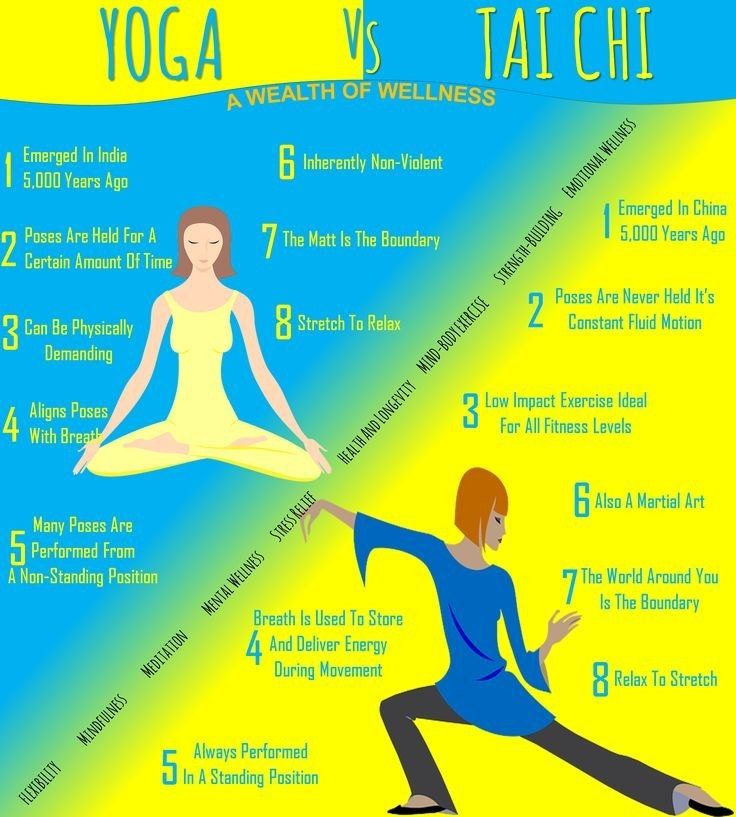

Several disciplines and practices can cultivate mindfulness, such as yoga, tai chi and qigong, but most of the literature has focused on mindfulness that is developed through mindfulness meditation — those self-regulation practices that focus on training attention and awareness in order to bring mental processes under greater voluntary control and thereby foster general mental well-being and development and/or specific capacities such as calmness, clarity and concentration (Walsh & Shapiro, 2006).

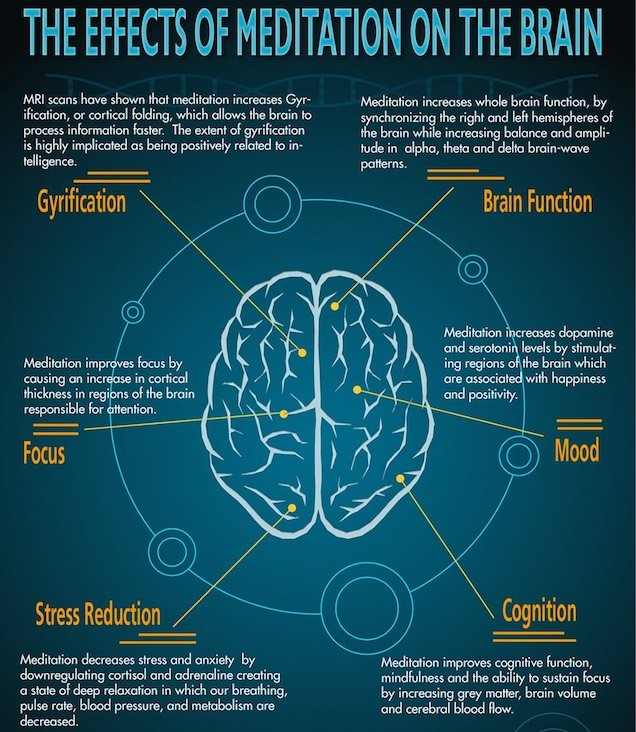

Researchers theorize that mindfulness meditation promotes metacognitive awareness, decreases rumination via disengagement from perseverative cognitive activities and enhances attentional capacities through gains in working memory. These cognitive gains, in turn, contribute to effective emotion-regulation strategies.

More specifically, research on mindfulness has identified these benefits:

Reduced rumination. Several studies have shown that mindfulness reduces rumination. In one study, for example, Chambers et al. (2008) asked 20 novice meditators to participate in a 10-day intensive mindfulness meditation retreat. After the retreat, the meditation group had significantly higher self-reported mindfulness and a decreased negative affect compared with a control group. They also experienced fewer depressive symptoms and less rumination. In addition, the meditators had significantly better working memory capacity and were better able to sustain attention during a performance task compared with the control group.

Stress reduction. Many studies show that practicing mindfulness reduces stress. In 2010, Hoffman et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 39 studies that explored the use of mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. The researchers concluded that mindfulness-based therapy may be useful in altering affective and cognitive processes that underlie multiple clinical issues.

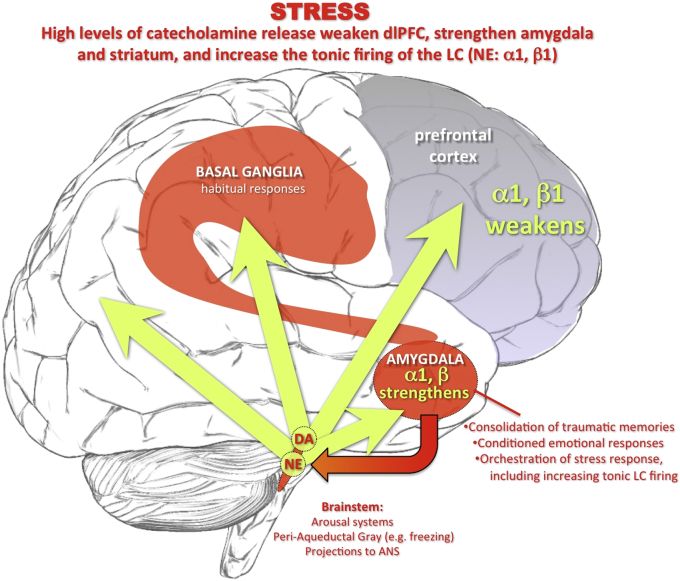

Those findings are consistent with evidence that mindfulness meditation increases positive affect and decreases anxiety and negative affect. In one study, participants randomly assigned to an eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction group were compared with controls on self-reported measures of depression, anxiety and psychopathology, and on neural reactivity as measured by fMRI after watching sad films (Farb et al., 2010). The researchers found that the participants who experienced mindfulness-based stress reduction had significantly less anxiety, depression and somatic distress compared with the control group. In addition, the fMRI data indicated that the mindfulness group had less neural reactivity when they were exposed to the films than the control group, and they displayed distinctly different neural responses while watching the films than they did before their mindfulness training. These findings suggest that mindfulness meditation shifts people's ability to use emotion regulation strategies in a way that enables them to experience emotion selectively, and that the emotions they experience may be processed differently in the brain (Farb et al., 2010; Williams, 2010).

In addition, the fMRI data indicated that the mindfulness group had less neural reactivity when they were exposed to the films than the control group, and they displayed distinctly different neural responses while watching the films than they did before their mindfulness training. These findings suggest that mindfulness meditation shifts people's ability to use emotion regulation strategies in a way that enables them to experience emotion selectively, and that the emotions they experience may be processed differently in the brain (Farb et al., 2010; Williams, 2010).

Boosts to working memory. Improvements to working memory appear to be another benefit of mindfulness, research finds. A 2010 study by Jha et al., for example, documented the benefits of mindfulness meditation among a military group who participated in an eight-week mindfulness training, a nonmeditating military group and a group of nonmeditating civilians. Both military groups were in a highly stressful period before deployment. The researchers found that the nonmeditating military group had decreased working memory capacity over time, whereas working memory capacity among nonmeditating civilians was stable across time. Within the meditating military group, however, working memory capacity increased with meditation practice. In addition, meditation practice was directly related to self-reported positive affect and inversely related to self-reported negative affect.

The researchers found that the nonmeditating military group had decreased working memory capacity over time, whereas working memory capacity among nonmeditating civilians was stable across time. Within the meditating military group, however, working memory capacity increased with meditation practice. In addition, meditation practice was directly related to self-reported positive affect and inversely related to self-reported negative affect.

Focus. Another study examined how mindfulness meditation affected participants' ability to focus attention and suppress distracting information. The researchers compared a group of experienced mindfulness meditators with a control group that had no meditation experience. They found that the meditation group had significantly better performance on all measures of attention and had higher self-reported mindfulness. Mindfulness meditation practice and self-reported mindfulness were correlated directly with cognitive flexibility and attentional functioning (Moore and Malinowski, 2009).

Less emotional reactivity. Research also supports the notion that mindfulness meditation decreases emotional reactivity. In a study of people who had anywhere from one month to 29 years of mindfulness meditation practice, researchers found that mindfulness meditation practice helped people disengage from emotionally upsetting pictures and enabled them to focus better on a cognitive task as compared with people who saw the pictures but did not meditate (Ortner et al., 2007).

More cognitive flexibility. Another line of research suggests that in addition to helping people become less reactive, mindfulness meditation may also give them greater cognitive flexibility. One study found that people who practice mindfulness meditation appear to develop the skill of self-observation, which neurologically disengages the automatic pathways that were created by prior learning and enables present-moment input to be integrated in a new way (Siegel, 2007a). Meditation also activates the brain region associated with more adaptive responses to stressful or negative situations (Cahn & Polich, 2006; Davidson et al., 2003). Activation of this region corresponds with faster recovery to baseline after being negatively provoked (Davidson, 2000; Davidson, Jackson, & Kalin, 2000).

Meditation also activates the brain region associated with more adaptive responses to stressful or negative situations (Cahn & Polich, 2006; Davidson et al., 2003). Activation of this region corresponds with faster recovery to baseline after being negatively provoked (Davidson, 2000; Davidson, Jackson, & Kalin, 2000).

Relationship satisfaction. Several studies find that a person's ability to be mindful can help predict relationship satisfaction — the ability to respond well to relationship stress and the skill in communicating one's emotions to a partner. Empirical evidence suggests that mindfulness protects against the emotionally stressful effects of relationship conflict (Barnes et al., 2007), is positively associated with the ability to express oneself in various social situations (Dekeyser el al., 2008) and predicts relationship satisfaction (Barnes et al., 2007; Wachs & Cordova, 2007).

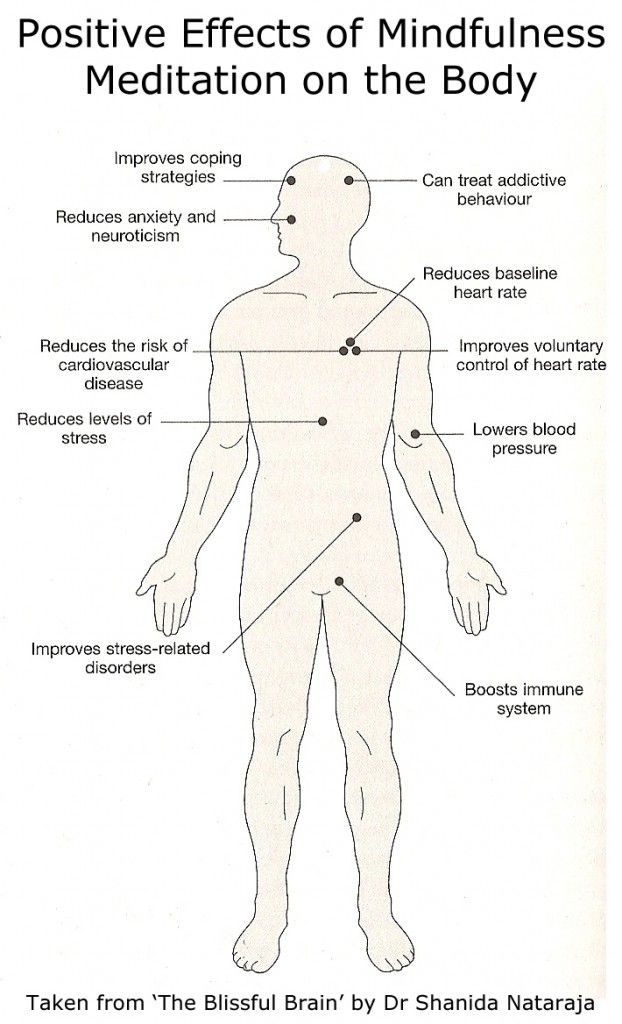

Other benefits. Mindfulness has been shown to enhance self-insight, morality, intuition and fear modulation, all functions associated with the brain's middle prefrontal lobe area. Evidence also suggests that mindfulness meditation has numerous health benefits, including increased immune functioning (Davidson et al., 2003; see Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004 for a review of physical health benefits), improvement to well-being (Carmody & Baer, 2008) and reduction in psychological distress (Coffey & Hartman, 2008; Ostafin et al., 2006). In addition, mindfulness meditation practice appears to increase information processing speed (Moore & Malinowski, 2009), as well as decrease task effort and having thoughts that are unrelated to the task at hand (Lutz et al., 2009).

Evidence also suggests that mindfulness meditation has numerous health benefits, including increased immune functioning (Davidson et al., 2003; see Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004 for a review of physical health benefits), improvement to well-being (Carmody & Baer, 2008) and reduction in psychological distress (Coffey & Hartman, 2008; Ostafin et al., 2006). In addition, mindfulness meditation practice appears to increase information processing speed (Moore & Malinowski, 2009), as well as decrease task effort and having thoughts that are unrelated to the task at hand (Lutz et al., 2009).

The effects of meditation on therapists and therapist trainees

While many studies have been conducted on the benefits of applying mindfulness approaches to psychotherapy clients (for reviews, see Didonna, 2009 and Baer, 2006), research on the effects of mindfulness on psychotherapists is just beginning to emerge. Specifically, research has identified these benefits for psychotherapists who practice mindfulness meditation:

Empathy. Several studies suggest that mindfulness promotes empathy. One study, for example, looked at premedical and medical students who participated in an eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction training. It found that the mindfulness group had significantly higher self-reported empathy than a control group (Shapiro, Schwartz, & Bonner, 1998). In 2006, a qualitative study of therapists who were experienced meditators found that they believed that mindfulness meditation helped develop empathy toward clients (Aiken, 2006). Along similar lines, Wang (2007) found that therapists who were experienced mindfulness meditators scored higher on measures of self-reported empathy than therapists who did not meditate.

Several studies suggest that mindfulness promotes empathy. One study, for example, looked at premedical and medical students who participated in an eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction training. It found that the mindfulness group had significantly higher self-reported empathy than a control group (Shapiro, Schwartz, & Bonner, 1998). In 2006, a qualitative study of therapists who were experienced meditators found that they believed that mindfulness meditation helped develop empathy toward clients (Aiken, 2006). Along similar lines, Wang (2007) found that therapists who were experienced mindfulness meditators scored higher on measures of self-reported empathy than therapists who did not meditate.

Compassion. Mindfulness-based stress reduction training has also been found to enhance self-compassion among health-care professionals (Shapiro, Astin, Bishop, & Cordova, 2005) and therapist trainees (Shapiro, Brown, & Biegel, 2007). In 2009, Kingsbury investigated the role of self-compassion in relation to mindfulness. Two components of mindfulness — nonjudging and nonreacting — were strongly correlated with self-compassion, as were two dimensions of empathy — taking on others' perspectives (i.e., perspective taking) and reacting to others' affective experiences with discomfort. Self-compassion fully mediated the relationship between perspective taking and mindfulness.

Two components of mindfulness — nonjudging and nonreacting — were strongly correlated with self-compassion, as were two dimensions of empathy — taking on others' perspectives (i.e., perspective taking) and reacting to others' affective experiences with discomfort. Self-compassion fully mediated the relationship between perspective taking and mindfulness.

Counseling skills. Empirical literature demonstrates that including mindfulness interventions in psychotherapy training may help therapists develop skills that make them more effective. In a four-year qualitative study, for example, counseling students who took a 15-week course that included mindfulness meditation reported that mindfulness practice enabled them to be more attentive to the therapy process, more comfortable with silence, and more attuned with themselves and clients (Newsome, Christopher, Dahlen, & Christopher, 2006; Schure, Christopher, & Christopher, 2008). Counselors in training who have participated in similar mindfulness-based interventions have reported significant increases in self-awareness, insights about their professional identity (Birnbaum, 2008) and overall wellness (Rybak & Russell-Chapin, 1998).

Decreased stress and anxiety. Research found that premedical and medical students reported less anxiety and depressive symptoms after participating in an eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction training compared with a waiting list control group (Shapiro et al., 1998). The control group evidenced similar gains after exposure to mindfulness-based stress reduction training. Similarly, following such training, therapist trainees have reported decreased stress, rumination and negative affect (Shapiro et al., 2007). In addition, when compared with a control group, mindfulness-based stress reduction training has been shown to decrease total mood disturbance, including stress, anxiety and fatigue in medical students (Rosenzweig, Reibel, Greeson, Brainard, & Hojat, 2003).

Better quality of life. Using qualitative and quantitative measures, nursing students reported better quality of life and a significant decrease in negative psychological symptoms following exposure to mindfulness-based stress reduction training (Bruce, Young, Turner, Vander Wal, & Linden, 2002). Evidence from a study of counselor trainees exposed to interpersonal mindfulness training suggests that such interventions can foster emotional intelligence and social connectedness, and reduce stress and anxiety (Cohen & Miller, 2009).

Evidence from a study of counselor trainees exposed to interpersonal mindfulness training suggests that such interventions can foster emotional intelligence and social connectedness, and reduce stress and anxiety (Cohen & Miller, 2009).

Similarly, in a study of Chinese college students, those students who were randomly assigned to participate in a mindfulness meditation intervention had lower depression and anxiety, as well as less fatigue, anger and stress-related cortisol compared to a control group (Tang et al., 2007). These same students had greater attention, self-regulation and immunoreactivity. Another study assessed changes in symptoms of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder among New Orleans mental health workers following an eight-week meditation intervention that began 10 weeks after Hurricane Katrina. Although changes in depression symptoms were not found, PTSD and anxiety symptoms significantly decreased after the intervention (Waelde et al., 2008). The findings suggest that meditation may serve a buffering role for mental health workers in the wake of a disaster.

The findings suggest that meditation may serve a buffering role for mental health workers in the wake of a disaster.

Other benefits for therapists. To date, only one study has investigated the relationship between mindfulness and counseling self-efficacy. Greason and Cashwell (2009) found that counseling self-efficacy was significantly predicted by self-reported mindfulness among masters-level interns and doctoral counseling students. In that study, attention mediated the relationship between mindfulness and self-efficacy, suggesting that mindfulness may contribute to the development of beneficial attentional processes that aid psychotherapists in training (Greason & Cashwell, 2009). Other potential benefits of mindfulness include increased patience, intentionality, gratitude and body awareness (Rothaupt & Morgan, 2007).

Outcomes of clients whose therapists meditate

While research points to the conclusion that mindfulness meditation offers numerous benefits to therapists and trainees, do these benefits translate to psychotherapy treatment outcomes?

So far, only one study suggests it does. In a study conducted in Germany, randomly assigned counselor trainees who practiced Zen meditation for nine weeks reported higher self-awareness compared with nonmeditating counselor trainees (Grepmair et al., 2007). But more important, after nine weeks of treatment, clients of trainees who meditated displayed greater reductions in overall symptoms, faster rates of change, scored higher on measures of well-being and perceived their treatment to be more effective than clients of nonmeditating trainees.

In a study conducted in Germany, randomly assigned counselor trainees who practiced Zen meditation for nine weeks reported higher self-awareness compared with nonmeditating counselor trainees (Grepmair et al., 2007). But more important, after nine weeks of treatment, clients of trainees who meditated displayed greater reductions in overall symptoms, faster rates of change, scored higher on measures of well-being and perceived their treatment to be more effective than clients of nonmeditating trainees.

However, the results of three other studies were not as encouraging. Stanley et al. (2006) studied the relationship between trait mindfulness among 23 doctoral-level clinical psychology trainees in relation to treatment outcomes of 144 adult clients at a community clinic that used manualized, empirically supported treatments. Contrary to expectation, therapist mindfulness was inversely correlated with client outcome.

This is consistent with other findings that suggest an inverse relationship exists between therapists' mindfulness and client outcomes (Bruce, 2006; Vinca & Hayes, 2007). Other research suggests that no relationship exists between therapist mindfulness and therapy outcome (Stratton, 2006).

Other research suggests that no relationship exists between therapist mindfulness and therapy outcome (Stratton, 2006).

What might be behind these results? It could be that "more mindful" people are likely to score lower on self-reports of mindfulness because they are more accurately able to describe their "mindlessness." Conversely, people who are less mindful may not realize it and therefore may be inclined to rate themselves higher on such measures.

Overall, while the psychological and physical health benefits of mindfulness meditation are strongly supported by research, the ways in which therapists' mindfulness meditation practice and therapists' mindfulness translate to measureable outcomes in psychotherapy remain unclear. Future research is needed to examine the relations between therapists' mindfulness, therapists' regular mindfulness meditation practice and common factors known to contribute to successful treatment outcomes.

Important next steps in research

Future research holds tremendous potential for learning more about the neurophysiological processes of meditation and the benefits of long-term practice on the brain. Research on neuroplasticity may help explain the relationships among length and quality of meditation practice, developmental stages of meditators and psychotherapy outcomes. More research is needed to better understand how the benefits of meditation practice accumulate over time.

Research on neuroplasticity may help explain the relationships among length and quality of meditation practice, developmental stages of meditators and psychotherapy outcomes. More research is needed to better understand how the benefits of meditation practice accumulate over time.

In addition, psychologists and others need to explore other ways to increase mindfulness in addition to meditation. Given that current research does not indicate that therapists' self-reported mindfulness enhances client outcomes, better measures of mindfulness may need to be developed or different research designs that do not rely on self-report measures need to be used. Garland and Gaylord (2009) have proposed that the next generation of mindfulness research encompass four domains: 1. performance-based measures of mindfulness, as opposed to self-reports of mindfulness; 2. scientific evaluation of notions espoused by Buddhist traditions; 3. neuroimaging technology to verify self-report data; and 4. changes in gene expression as a result of mindfulness. Research along these lines is likely to enhance our understanding of mindfulness and its potential benefits to psychotherapy.

Research along these lines is likely to enhance our understanding of mindfulness and its potential benefits to psychotherapy.

Research is also needed on effective and practical means of teaching therapists mindfulness practices. Future research could investigate ways mindfulness practices and mindfulness meditation could be integrated into trainees' practicum and clinical supervision. Since mindfulness-based stress reduction has been successfully used with therapist trainees (e.g., Shapiro et al., 2007), the technique may be a simple way for therapists to integrate mindfulness practices into trainees' practicum class or group supervision. Future research questions could include: Does therapists' practice of mindfulness meditation in clinical supervision with their supervisees affect the supervisory alliance or relational skills of supervisees? Does practicing formal mindfulness meditation as a group in practicum or internship aid in group cohesion, self-care, relational skills or measurable common factors that contribute to successful psychotherapy?

Given the limited research thus far on empathy, compassion, decreased stress and reactivity, more research is needed on how mindfulness meditation practice affects these constructs and measurable counseling skills in both trainees and therapists. For example, how does mindfulness meditation practice affect empathy and compassion for midcareer or late-career therapists who are experienced at mindfulness?

For example, how does mindfulness meditation practice affect empathy and compassion for midcareer or late-career therapists who are experienced at mindfulness?

Shapiro and Carlson (2009) have suggested that mindfulness meditation can also serve psychologists as a means of self-care to prevent burnout. Future research is needed on not only how the practice of mindfulness meditation helps facilitate trainee development and psychotherapy processes, but also how it can help therapists prevent burnout and other detrimental outcomes of work-related stress.

In addition, despite abundant theoretical work on ways to conceptually merge Buddhist and Western psychology to psychotherapy (e.g., Epstein, 2007, 1995), there is a lack of literature on what it looks like in session when a therapist uses mindfulness and Buddhist-oriented approaches to treat specific clinical issues.

In conclusion, mindfulness has the potential to facilitate trainee and therapists' development, as well as affect change mechanisms known to contribute to successful psychotherapy. The field of psychology could benefit from future research examining cause and effect relationships in addition to mediational models in order to better understand the benefits of mindfulness and mindfulness meditation practice.

The field of psychology could benefit from future research examining cause and effect relationships in addition to mediational models in order to better understand the benefits of mindfulness and mindfulness meditation practice.

Purchase the exam online.

Daphne M. Davis, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow at the Trauma Center at Justice Resource Institute in Brookline, Mass.

Jeffrey A. Hayes, PhD, is a professor of counseling psychology at the Pennsylvania State University department of educational psychology, counseling and special education.

5 Science-Backed Reasons Mindfulness Meditation Is Good for Your Health

Ask a group of people why they meditate and you’ll get a list of replies as varied as the people you’re asking—generally, the reason will have something to do with each individuals’ idea of the best, most-fulfilled (dare we say happier) version of themselves.

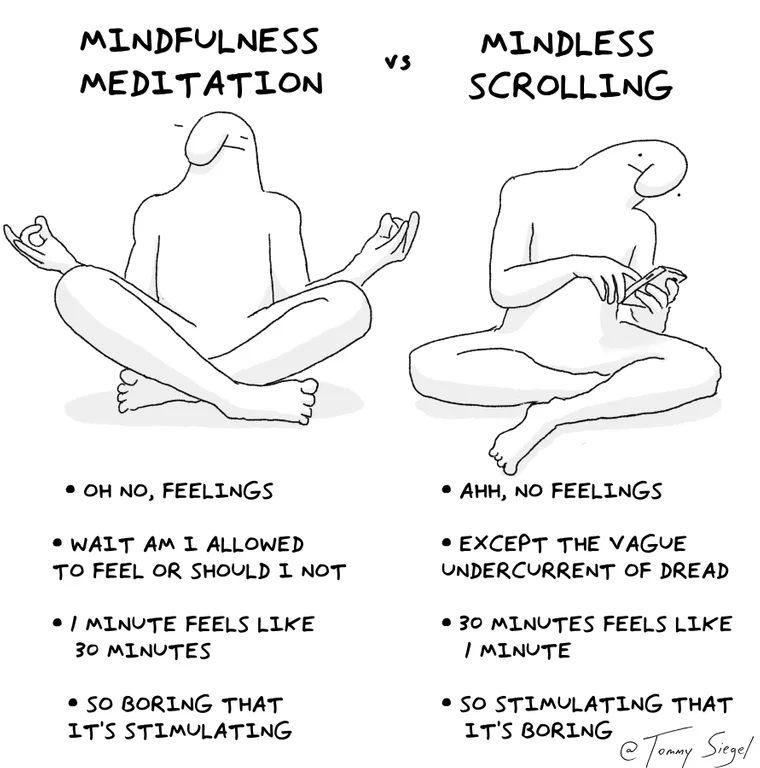

In recent decades, researchers have been gaining insight into the benefits of practicing this ancient tradition. By studying more secular versions of mindfulness meditation, they’ve found that learning to pay attention to our current experiences and accept them without judgment might indeed help us to be happier. Studies to date suggest that mindfulness affects many aspects of our psychological well-being—improving our mood, increasing positive emotions, and decreasing our anxiety, emotional reactivity, and job burnout.

By studying more secular versions of mindfulness meditation, they’ve found that learning to pay attention to our current experiences and accept them without judgment might indeed help us to be happier. Studies to date suggest that mindfulness affects many aspects of our psychological well-being—improving our mood, increasing positive emotions, and decreasing our anxiety, emotional reactivity, and job burnout.

But does mindfulness affect our bodies as well as our minds?

Recently, researchers have been exploring this question—with some surprising results. While much of the early research on mindfulness relied on pilot studies with biased measures or limited groups of participants, more recent studies have been using less-biased physiological markers and randomly controlled experiments to get at the answer. Taken together, the studies suggest that mindfulness may impact our hearts, brains, immune systems, and more.

Though nothing suggests mindfulness is a standalone treatment for disease nor the most important ingredient for a healthy life, here are some of the ways that it appears to benefit us physically.

Heart disease is the leading killer in the United States, accounting for about 1 in 4 deaths every year. So, whatever decreases the risks or symptoms of heart disease would significantly impact society’s health. Mindfulness may help with that.

In one study, people with pre-hypertension were randomly assigned to augment their drug treatment with either a course in mindfulness meditation or a program that taught progressive muscle relaxation. Those who learned mindfulness had significantly greater reductions in their systolic and diastolic blood pressure than those who learned progressive muscle relaxation, suggesting that mindfulness could help people at risk for heart disease by bringing blood pressure down.

Those who learned mindfulness had significantly greater reductions in their systolic and diastolic blood pressure than those who learned progressive muscle relaxation, suggesting that mindfulness could help people at risk for heart disease by bringing blood pressure down.

In another study, people with heart disease were randomly assigned to either an online program to help them practice meditation or to a waitlist for the program while undergoing normal treatment for heart disease. Those who took the mindfulness program showed significant improvements on the six-minute walking test (a measure of cardiovascular capacity) and slower heart rates than those in the waitlist group.

While one review of randomly controlled studies showed that mindfulness may have mixed effects on the physical symptoms of heart disease, a more recent review published by the American Heart Association concluded that, while research remains preliminary, there is enough evidence to suggest mindfulness as an adjunct treatment for coronary disease and its prevention.

Mindfulness may also be good for hearts that are already relatively healthy. Research suggests that meditating can increase respiratory sinus arrhythmia, the natural variations in heart rate that happen when we breathe that indicate better heart health and an increased chance of surviving a heart attack.

People tend to lose some of their cognitive flexibility and short-term memory as they age. But mindfulness may be able to slow cognitive decline, even in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

In a 2016 study, people with Alzheimer’s disease engaged in either mindfulness meditation, cognitive stimulation therapy, relaxation training, or no treatment, and were given cognitive tests over two years. While cognitive stimulation and relaxation training seemed to be somewhat beneficial in comparison to no treatment, the mindfulness training group had much more robust improvements on cognitive scores than any other group.

Why might that be true? A 2017 study looking at brain function in healthy, older adults suggests meditation may increase attention. In this study, people 55 to 75 years old spent eight weeks practicing either focused breathing meditation or a control activity. Then, they were given the Stroop test—a test that measures attention and emotional control—while having their brains monitored by electroencephalography. Those undergoing breath training had significantly better attention on the Stroop test and more activation in an area of the brain associated with attention than those in the active control group.

Those undergoing breath training had significantly better attention on the Stroop test and more activation in an area of the brain associated with attention than those in the active control group.

While this research is preliminary, a systematic review of research to date suggests that mindfulness may mitigate cognitive decline, perhaps due to its effects on memory, attention, processing, and executive functioning.

When we encounter viruses and other disease-causing organisms, our bodies send out troops of immune cells that circulate in the blood. These cells, including pro- and anti-inflammatory proteins, neutrophils, T-cells, immunoglobulins, and natural killer cells, help us to fight disease and infection in various ways. Mindfulness, it turns out, may affect these disease-fighting cells.

In several studies, mindfulness meditation appeared to increase levels of T-cells or T-cell activity in patients with HIV or breast cancer. This suggests that mindfulness could play a role in fighting cancer and other diseases that call upon immune cells. Indeed, in people suffering from cancer, mindfulness appears to improve a variety of biomarkers that might indicate progression of the disease.

Indeed, in people suffering from cancer, mindfulness appears to improve a variety of biomarkers that might indicate progression of the disease.

Indeed, in people suffering from cancer, mindfulness appears to improve a variety of biomarkers that might indicate progression of the disease.

In another study, elderly participants were randomly assigned to an eight-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) course or a moderate-intensity exercise program. At the end, participants who’d practiced mindfulness had higher levels of the protein interleukin-8 in their nasal secretions, suggesting improved immune function.

Another study found increases in interleukin-10 in colitis patients who took a mindfulness meditation course compared to a mind-body educational program, especially among patients whose colitis had flared up. Yet another study found that patients who had greater increases in mindfulness after an MBSR course also showed faster wound healing, a process regulated by the immune system.

Studies have found effects on markers of inflammation, too—like C-reactive protein, which in higher levels can harm physical health. Research shows that people with rheumatoid arthritis have reduced C-reactive protein levels after taking an MBSR course versus being on a waitlist for the course. Overall, these findings suggest that mindfulness meditation can have disease-fighting powers through our immune response.

Mindfulness may reduce cell aging

Cell aging occurs naturally as cells repeatedly divide over the lifespan and can also be increased by disease or stress. Proteins called telomeres, which are found at the end of chromosomes and serve to protect them from aging, seem to be impacted by mindfulness meditation.

Studies suggest that long-time meditators may have greater telomere lengths. In one experimental study, researchers found that breast cancer survivors who went through MBSR preserved the length of their telomeres better than those who were on a waitlist. However, this study also found that general supportive therapies impacted telomere length; so, there may not be something special about MBSR that impacts cell aging.

However, this study also found that general supportive therapies impacted telomere length; so, there may not be something special about MBSR that impacts cell aging.

On the other hand, another study with breast cancer survivors found no differences in telomere length after taking an MBSR course; but they did find differences in telomere activity, which is also related to cell aging. In fact, a 2018 review of research ties mindfulness training to increased telomere activity, suggesting it indirectly affects the integrity of the telomeres in our cells. Perhaps that’s why scientists are at least optimistic about the positive effects of meditation on aging.

Of course, while the above physiological benefits of mindfulness are compelling, we needn’t forget that mindfulness also impacts our psychological well-being, which, in turn, affects physical health. In fact, it’s quite likely that these changes have synergistic effects on one another.

First of all, a great deal of research suggests that mindfulness can help healthy people reduce their stress. And thanks to Jon-Kabat Zinn’s pioneering MBSR program, there’s now a large body of research showing that mindfulness can help people cope with the pain, anxiety, depression, and stress that might accompany illness, especially chronic conditions.

And thanks to Jon-Kabat Zinn’s pioneering MBSR program, there’s now a large body of research showing that mindfulness can help people cope with the pain, anxiety, depression, and stress that might accompany illness, especially chronic conditions.

For example, drug addictions, at heart, come about because of physiological cravings for a substance that relieves people temporarily from their psychological suffering. Mindfulness can be a useful adjunct to addiction treatment by helping people better understand and tolerate their cravings, potentially helping them to avoid relapse after they’ve been safely weaned off of drugs or alcohol. The same is true for people struggling with overeating.

Mindfulness can be a useful adjunct to addiction treatment by helping people better understand and tolerate their cravings, potentially helping them to avoid relapse after they’ve been safely weaned off of drugs or alcohol.

Fascinating though it is, we shouldn’t overplay meditation’s effects on physical health at the expense of its importance to emotional health. In fact, it may be difficult to separate out the two, as a key impact of mindfulness is stress reduction, and psychological stress has been tied to heart health, immune response, and telomere length. This idea is further supported by the fact that other stress-reducing therapies also seem to impact physical health, as well.

In fact, it may be difficult to separate out the two, as a key impact of mindfulness is stress reduction, and psychological stress has been tied to heart health, immune response, and telomere length. This idea is further supported by the fact that other stress-reducing therapies also seem to impact physical health, as well.

Still, it’s encouraging to know that something that can be taught and practiced can have an impact on our overall health—not just mental but also physical—more than 2,000 years after it was developed. That’s reason enough to give mindfulness meditation a try.

This article was adapted from Greater Good, the online magazine of UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, one of Mindful’s partners. View the original article.

Why It's Time for You to Meditate: A Helpful Guide to Mindfulness Practice

You can develop mindfulness to everything else along the same lines. There is a variant of meditation - conscious walking. When, when moving, you do not dissolve in the thoughts and concerns of the day, but concentrate on how you lift one leg, move it in space, put it on the ground, then lift the other and so on. For beginners, this may be unusual and difficult, but it allows you to see and realize how difficult it really is to concentrate on something that is not very exciting and how the brain begins to resist and throw up all sorts of topics for thought. nine0003

When, when moving, you do not dissolve in the thoughts and concerns of the day, but concentrate on how you lift one leg, move it in space, put it on the ground, then lift the other and so on. For beginners, this may be unusual and difficult, but it allows you to see and realize how difficult it really is to concentrate on something that is not very exciting and how the brain begins to resist and throw up all sorts of topics for thought. nine0003

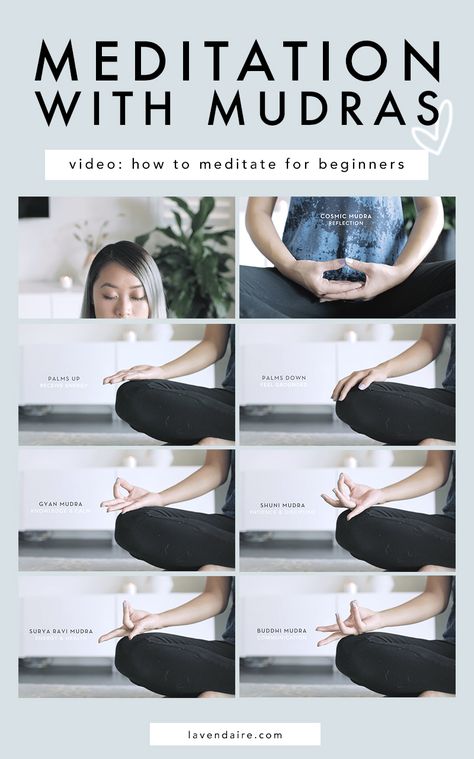

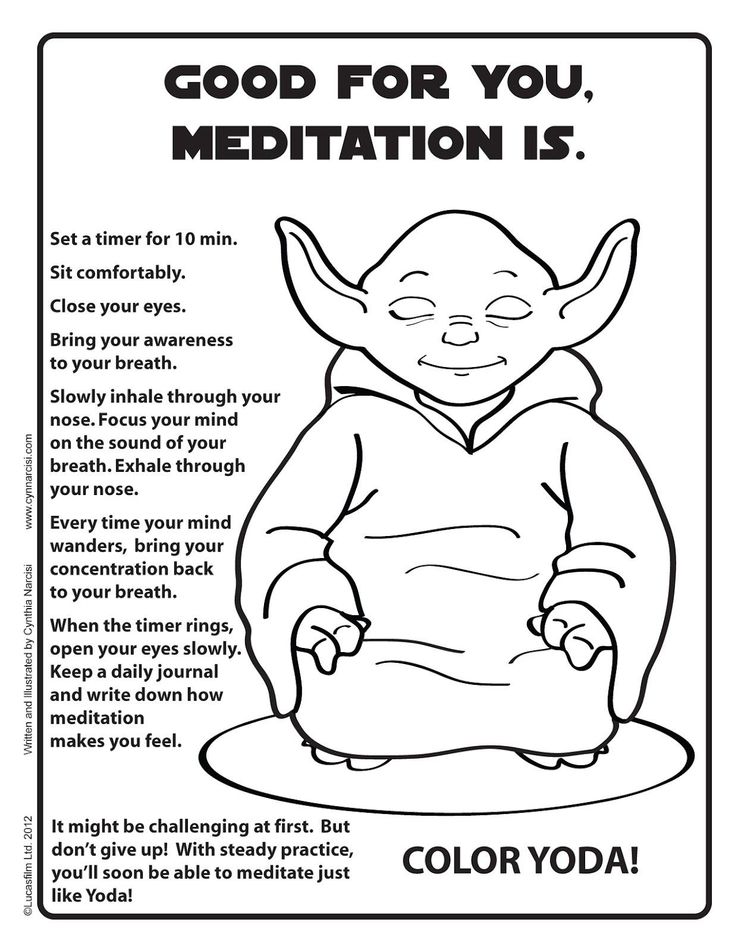

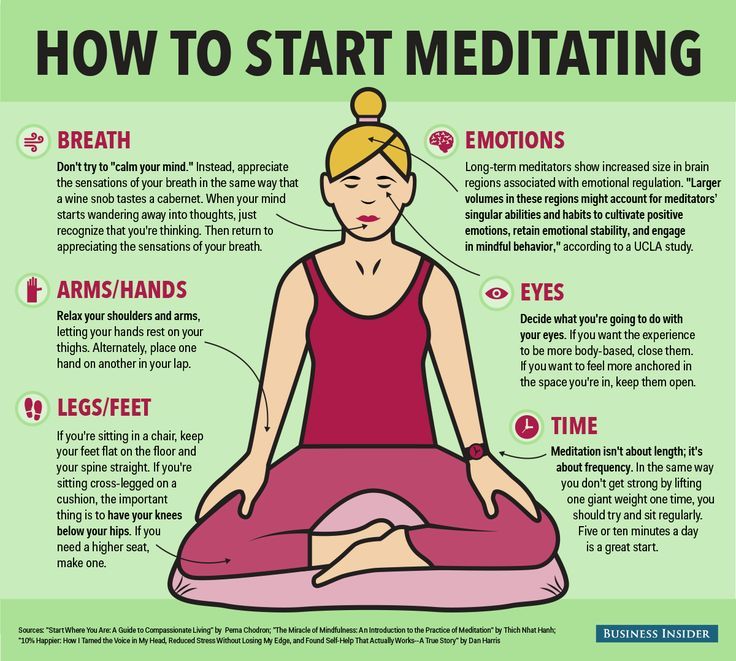

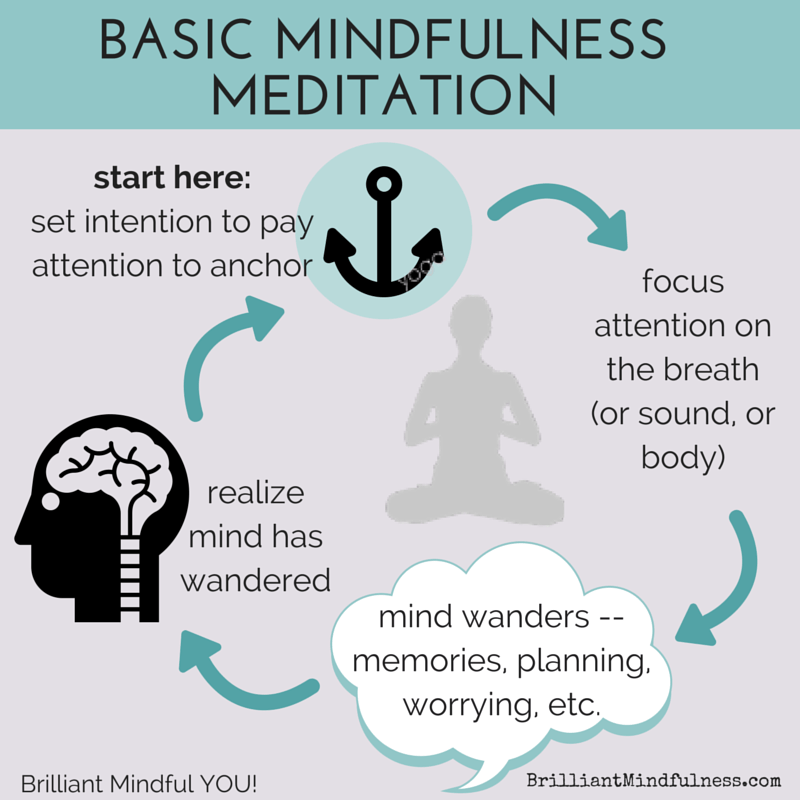

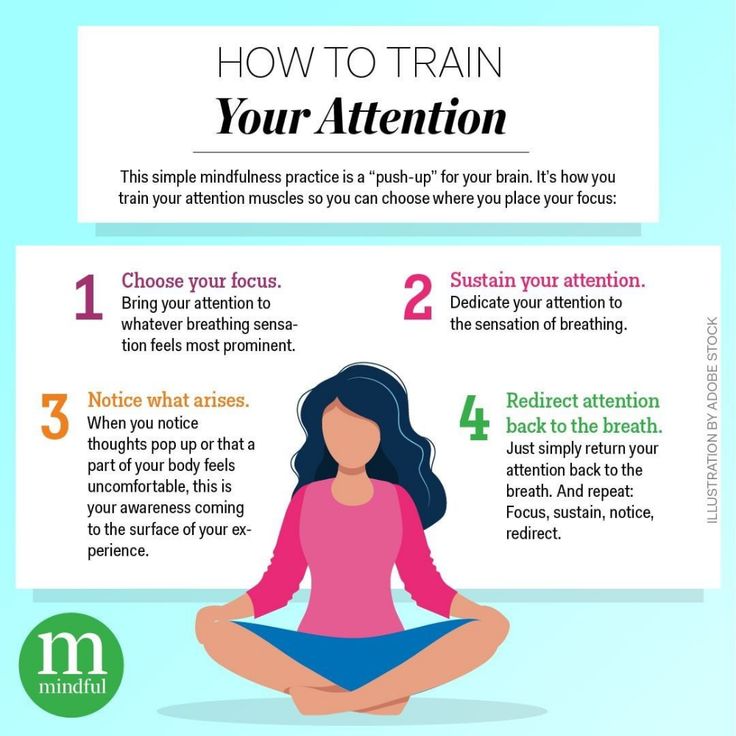

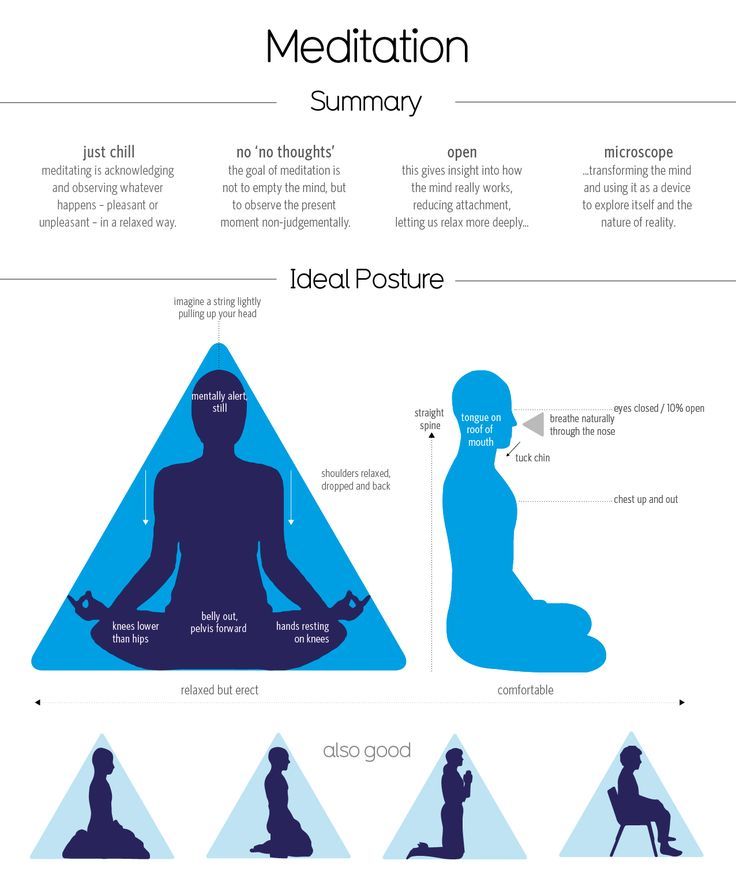

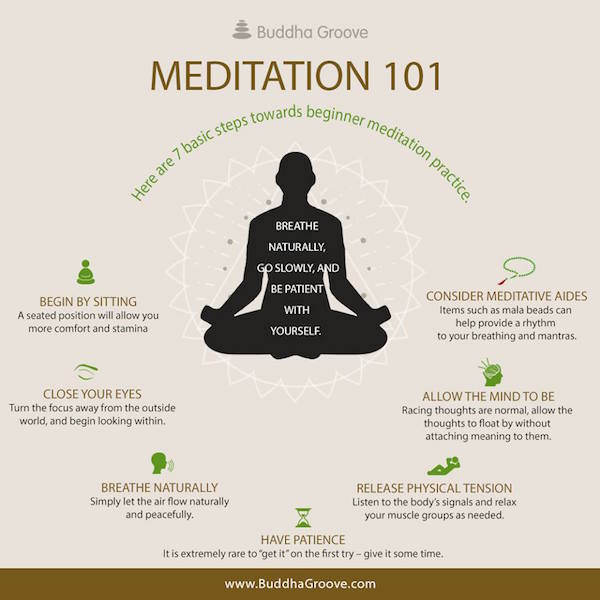

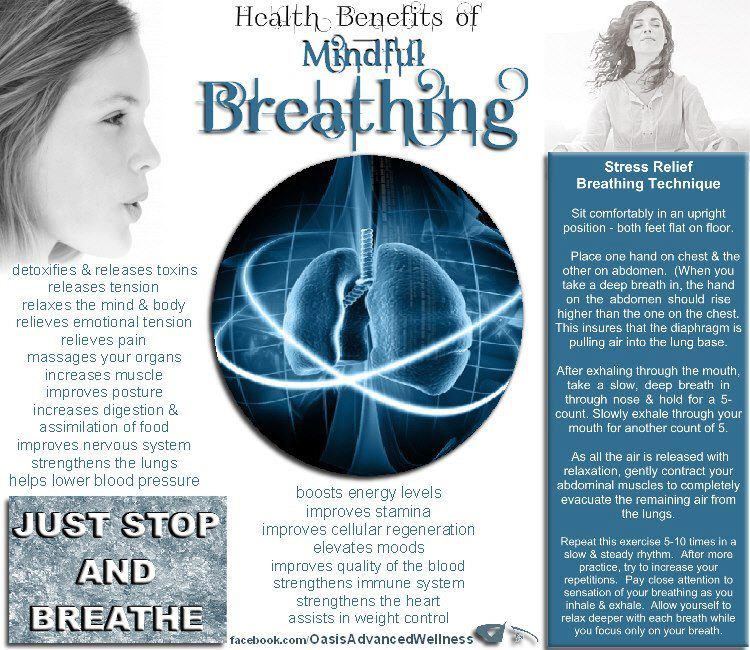

The most basic technique is mindfulness of the breath. Close your eyes and just watch how you breathe. Try starting with a minute - for a beginner, it can be excruciatingly long, but interesting nonetheless. Track your sensations from the contact of air and nostrils, try to feel how your chest expands when you inhale and your stomach drops when you exhale. But the key trick here is to pay attention to how you are distracted by your thoughts, and go back to observing sensations. nine0003

Another direction is mindfulness of thoughts. The essence of this meditation is that you observe what thoughts arise in your head. This is an interesting experiment - to track how ideas appear and go, how quickly they replace each other, what emotions they evoke. In cognitive therapy, there are various exercises based on Buddhist meditations: you can imagine that thoughts are clouds floating in the sky, or in your imagination you can put each thought in a boat and watch how they float down the river. Another option is to imagine a white room with two doors, and imagine that every thought that enters your mind enters through one door and exits through another. The essence of this approach is to realize how many thoughts the brain generates every second, and learn to observe them. nine0003

This is an interesting experiment - to track how ideas appear and go, how quickly they replace each other, what emotions they evoke. In cognitive therapy, there are various exercises based on Buddhist meditations: you can imagine that thoughts are clouds floating in the sky, or in your imagination you can put each thought in a boat and watch how they float down the river. Another option is to imagine a white room with two doors, and imagine that every thought that enters your mind enters through one door and exits through another. The essence of this approach is to realize how many thoughts the brain generates every second, and learn to observe them. nine0003

Meditation without the supervision of a specialist can lead to hell.

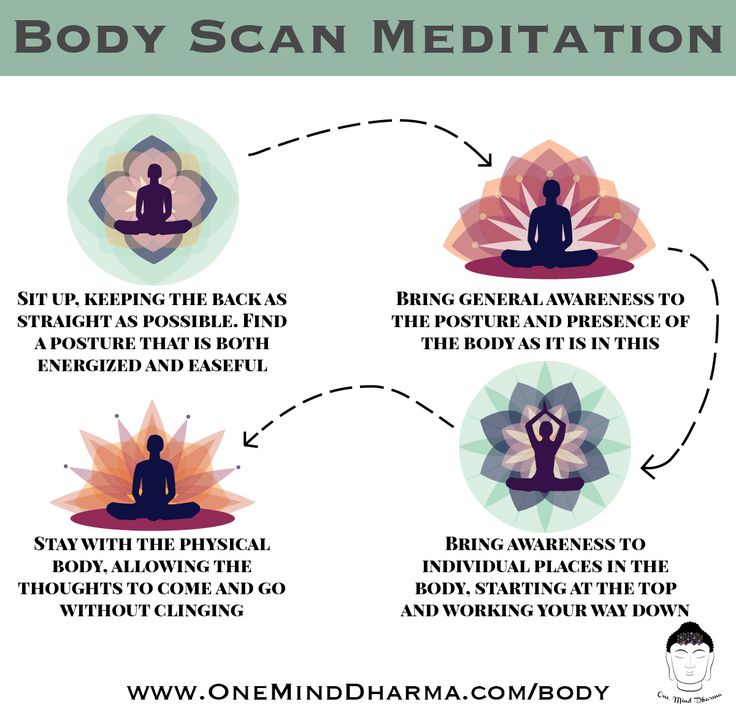

Another popular variation is mindfulness of sensations in the body, otherwise known as body scanning. Here - as a rule, with an instructor (this can be a living person in some kind of joint meditation class, and an application, and a video on YouTube, there is a lot of such content now) - you consistently pass your attention through your whole body.

First, concentrate on the sensations in your toes, then study how your left heel feels, receive the signals that your calf and shin give you, rise to your knees - and so on, higher and higher, gradually covering your entire body with attention. Such meditation allows you to relax very well and relieve muscle tension. It is nice to do it before bed to make it easier to fall asleep. nine0003

However, there is always a great danger of overdoing it and starting to meditate very intensely, because, for example, in traditional practices you cannot move, instead you need to concentrate extremely and clearly focus your attention. But here it is just useful to remember the goals, and if your goal is not religious ecstasy and getting into nirvana, but simply relaxation, it is important to allow yourself to treat meditation a little easier in order to really be able to relax and not overwork.

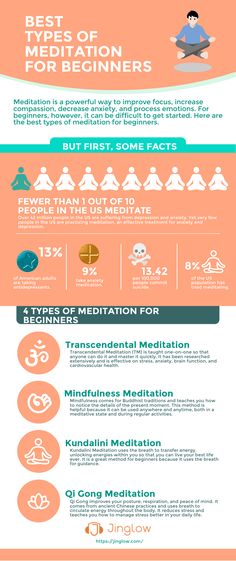

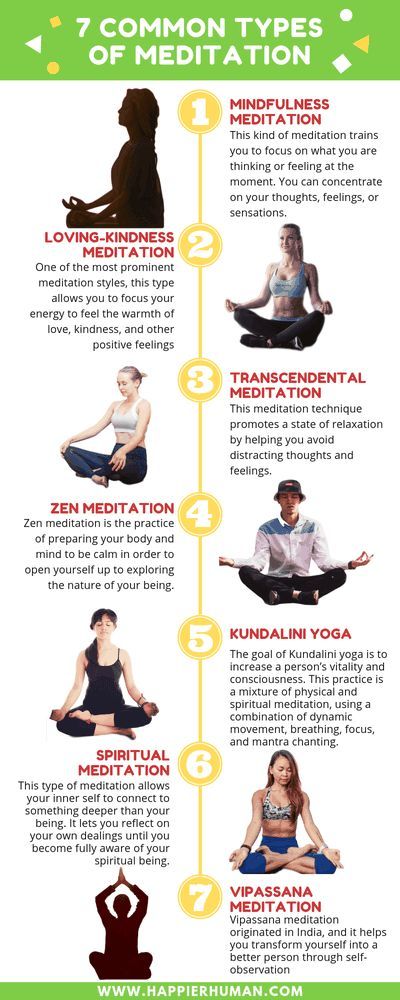

There are other directions and types, a little more esoteric, we will mention them in order to form a complete picture. Transcendental Meditation involves concentrating on a word or mantra and constantly repeating it to yourself. Vipassana is a practice aimed at “seeing things as they are”, for which they usually take a vow of silence and do not say anything for several days, only silently observe the external and internal world. The Loving-Kindness Meditation is an exercise in compassion for yourself, others, and the world. And meditation on the chakras is already hardcore, involving the opening of the third eye, so it is better to be as careful as possible with it. However, this is not all, but it is quite enough for a start. nine0003

Transcendental Meditation involves concentrating on a word or mantra and constantly repeating it to yourself. Vipassana is a practice aimed at “seeing things as they are”, for which they usually take a vow of silence and do not say anything for several days, only silently observe the external and internal world. The Loving-Kindness Meditation is an exercise in compassion for yourself, others, and the world. And meditation on the chakras is already hardcore, involving the opening of the third eye, so it is better to be as careful as possible with it. However, this is not all, but it is quite enough for a start. nine0003

HeadSpace

The world's most popular meditation app. It has more than a hundred different practices that help you concentrate or, conversely, relax. Of the minuses - there is only in English.

« Practice »

Application in Russian. It has a free 10-short-lesson course for beginners—the perfect entry point for beginners.

« Mo: meditation and sleep »

Startup from Mail.ru, contains more than two hundred classes in the most popular areas: anti-stress, productivity, sleep, personal relationships and self-esteem. to the Russian market, offers more than a thousand meditations, bedtime stories and a lot of content for quality sleep.

Insight Timer

A free application for meditators and even more of a social network where you can chat, upload your own meditations and share your impressions with other members of the community. A timer function is available - you can select the background noise and determine the time you want to spend in meditation. nine0003

Probably, you will also be interested:

How Meditation will help Save the world, and not only you

Your meditation will take place with these headphones

9000 Photo: Gettyimages: Gettyimages .

com; Press Service Archives

com; Press Service Archives Benefits of Meditation: How to Use the Power of Meditation

The practice of meditation has been around for thousands of years, and research continues to uncover a wide range of benefits from meditation. Meditation can positively impact many aspects of health, including mental, physical, and emotional health. Whether you have experience with meditation or are just starting out, meditation can bring many benefits to your mental and physical health. Consistent meditation practice can lead to real and lasting positive changes. nine0003

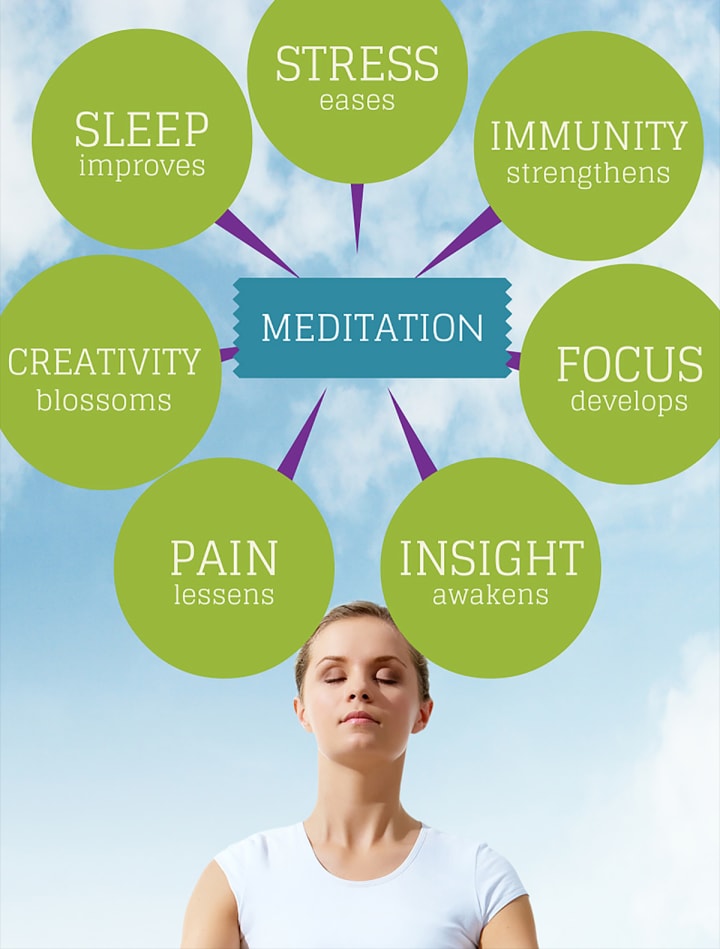

MENTAL AND COGNITIVE BENEFITS OF MEDITATION

One of the benefits of meditation is improved concentration and attention. Mindfulness meditation is a type of meditation aimed at becoming aware and acknowledging your inner thoughts while staying in the present moment. The practice of mindfulness meditation increases awareness of inner thoughts and improves the ability to reduce wandering and distracting thoughts. Controlling distracting thoughts improves the ability to focus on a task. Meditation can also help increase focus and mental discipline. nine0003

Controlling distracting thoughts improves the ability to focus on a task. Meditation can also help increase focus and mental discipline. nine0003

There is evidence that regular practice of meditation can lead to physical changes in the brain that have cognitive benefits. Regular practice of meditation can increase the volume of gray matter in the hippocampus, which is responsible for memory. Research has also shown that it positively affects the posterior cingulate region of the brain, which is an important part of learning and cognition, and the frontal cortex, which is responsible for memory and decision making.

THE EMOTIONAL BENEFITS OF MEDITATION

The consistent practice of meditation increases your ability to recognize and understand inner thoughts and, as a result, enhances self-awareness. Deeper self-awareness and understanding of thoughts can help increase feelings of compassion and kindness. Mindfulness training can also help a person communicate their thoughts and feelings to others, which can help improve interpersonal relationships.

One style of meditation called love-kindness meditation or "metta" focuses on developing positive thinking, compassion, inner and outer empathy. Meditation can help increase positive emotions, reduce negative thoughts about yourself and others, and build resilience. Practicing love-kindness meditation can also help in self-acceptance and self-knowledge. Love-kindness meditation can help develop and maintain positive relationships. In general, meditation can improve overall emotional well-being. nine0003

REDUCING STRESS AND ANXIETY

Meditation can be helpful in reducing psychological stress and anxiety. Many different styles and styles of meditation can help manage stress and anxiety, including progressive relaxation, breathwork, mindfulness-based meditation, and transcendental meditation. Mindfulness-based stress reduction meditation focuses on relaxing both the mind and body. It promotes understanding of inner thoughts and focuses attention on the present moment. nine0003

nine0003

Transcendental Meditation can lower the levels of certain hormones in the body, including epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol. These hormones are associated with increased levels of stress because they activate the sympathetic nervous system or the fight-or-flight response. Meditation reduces the response of the sympathetic nervous system and can lower your heart rate and slow your breathing.

Mindfulness meditation techniques are also used as a treatment in conjunction with cognitive behavioral therapy called mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy aims to replace negative thoughts with more positive ones and to develop positive coping strategies. This theory, combined with mindfulness training, which aims to be aware of one's thoughts, can help reduce anxiety and negative thoughts and aid in the development of positive coping skills. Mindfulness training may have other mental health benefits, as there is evidence that mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is beneficial for people with depression. Mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy can help people with depression by reformulating negative thought patterns. nine0003

Mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy can help people with depression by reformulating negative thought patterns. nine0003

SLEEP AND INSOMNIA

Many people turn to meditation to cope with insomnia or improve the quality of sleep. Many people experience sleep disturbances due to high levels of stress and wandering thoughts before falling asleep. Meditation can effectively reduce stress levels and achieve a more relaxed state, both physical and mental.

One meditation technique that can help a person relax their body is progressive relaxation. Progressive relaxation involves tensing and then relaxing the muscles of the body, one muscle group at a time, moving up or down the body. As the muscles tense and then relax, the body becomes more relaxed and ready for sleep. A body scan is a similar technique in which a person visualizes areas of tension in the body and uses focused breathing to release tension from those areas. nine0003

Breathing techniques can be used to slow breathing and lower the heart rate. Mindfulness meditation can help you fall asleep as it eases the mind by acknowledging wandering thoughts and then focusing them on the breath and feelings. This technique focuses the mind on the present and reduces the number of disturbing thoughts. These meditation techniques help to relax the mind and body in order to better prepare for falling asleep.

Mindfulness meditation can help you fall asleep as it eases the mind by acknowledging wandering thoughts and then focusing them on the breath and feelings. This technique focuses the mind on the present and reduces the number of disturbing thoughts. These meditation techniques help to relax the mind and body in order to better prepare for falling asleep.

PHYSICAL BENEFITS

PAIN RELIEF

Some people who experience chronic pain turn to meditation to reduce or help manage their pain. There is evidence that meditation and mindfulness practice can change certain structures and pathways in the brain, resulting in decreased sensitivity to pain. Meditation also trains the mind for better sensory processing of pain. One study found that meditation practiced along with yoga reduced white blood cell inflammation in the body, which is similar to the physical pain reduction used in pain medications such as ibuprofen. Another study found that meditation reduced amygdala activity associated with anticipation of pain. Changes in the dorsal anterior cingulate and somatosensory cortex also reduce pain sensitivity. nine0003

Changes in the dorsal anterior cingulate and somatosensory cortex also reduce pain sensitivity. nine0003

Meditation is helpful for people with chronic pain to reduce the anxiety and stress associated with pain. Mindfulness meditation can reduce anxiety associated with pain and focus the mind on the present moment. Meditation techniques such as progressive relaxation can also help release the tension that has accumulated in the body due to pain. The practice of meditation can also help in enhancing positive emotions and developing positive coping mechanisms for those experiencing chronic pain. nine0003

HEART HEALTH

One of the many health benefits of meditation is improved heart health. Research shows that meditation can lower your heart rate and blood pressure. More specifically, the practice of transcendental meditation or mantra meditation, which involves silently repeating mantras to achieve a relaxed and still state, is effective in lowering blood pressure. Lowering blood pressure and heart rate can reduce the chance of developing heart disease. In addition, people diagnosed with high blood pressure (hypertension) or heart disease can also benefit from meditation to maintain their cardiovascular health. Meditative practice can also help increase other heart-healthy habits such as quality sleep, physical activity, and a balanced diet, as meditation reduces stress and increases positive thinking and motivation. nine0003

Lowering blood pressure and heart rate can reduce the chance of developing heart disease. In addition, people diagnosed with high blood pressure (hypertension) or heart disease can also benefit from meditation to maintain their cardiovascular health. Meditative practice can also help increase other heart-healthy habits such as quality sleep, physical activity, and a balanced diet, as meditation reduces stress and increases positive thinking and motivation. nine0003

IMMUNE SYSTEM

Meditation can benefit physical health by improving the body's immune system. The practice of meditation can increase the levels and function of immune-specific cells such as T cells, as well as anti-inflammatory proteins and antibodies. An increased immune system response means the body is better able to fight off infections. In addition, meditation can improve the quality of sleep, reduce stress levels and increase positive emotions, which positively affects the immune system response. nine0003

nine0003

DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

Meditative practice can benefit those who experience digestive health problems such as Chron's disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Meditation has been shown to help reduce some of the symptoms of these diseases, including fatigue and stomach pain. As mentioned earlier, meditation can help manage pain and improve sleep quality. Meditation can also help reduce the stress and anxiety that make the condition worse. The digestive system is linked to the mind and the level of stress and anxiety in the body. Therefore, reducing stress and anxiety through meditation practice can be helpful in improving the overall health of the digestive system. nine0003

THE BENEFITS OF MEDITATION FAQ

HOW TO LEARN TO MEDITATE?

There are many sources on various meditation techniques, including

- Books

- Guided Audio Meditation

- Guided Video Meditation

- Online and face-to-face meditation courses

- Mindfulness Meditation Application

HOW LONG SHOULD THE MEDITATION LAST?

There is no exact time frame, although 10 minutes is recommended as the minimum duration to achieve the benefits of meditation. Meditation practice can last from 15 minutes to half an hour. Consistency is the most important thing in meditation. The regular practice of meditation is more important than the duration of each meditation. nine0003

Meditation practice can last from 15 minutes to half an hour. Consistency is the most important thing in meditation. The regular practice of meditation is more important than the duration of each meditation. nine0003

AT WHAT AGE SHOULD I START MEDITATION?

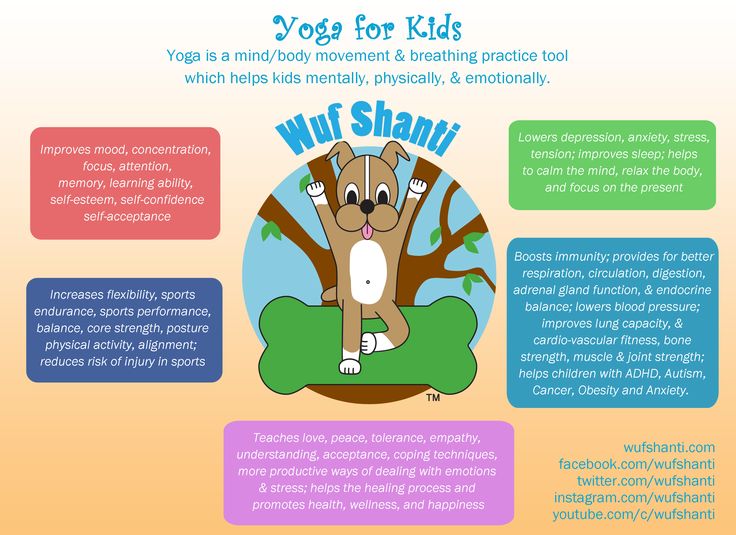

Meditation can be started at any age. Starting the practice of meditation as a child can be helpful. At an early age, children often start practicing techniques such as breathing and progressive relaxation.

WHICH IS THE BEST PLACE FOR MEDITATION?

Meditation does not require a specific place. It is important to be in a comfortable position and in an environment with a minimum of distractions. Most people sit, but there are options to lie down or even walk. nine0003

Resources for Anaachan meditation

Meditation wiki

Meditation for chakras

Meditation techniques

Meditation of body scan

Manageable Meditation to remove anxiety

Meditation Sleep

Mind-Body Connection

Gratitude Meditation

Anxiety Meditation

Management meditation

Night meditation

Self -knowledge

Transcendental meditation

Visualization meditation

Blogs on meditation

How Meditation helps to cope with a stress of

How Meditation changes the brain

How Meditation

9000 Meditative MEDITIONGifts for meditation

Benefits of meditation

What is meditation?

What is awareness? nine0003

Meditation Apps

Meditation for Beginners

Resources

How Meditation Can Help Manage Illness | Everyday Health

Calming the Nerves and Heart with Meditation - The Science in the News

What is Love-Kindness Meditation? (Including 4 scripts + video)

How to Meditate Before Sleep: Improve Sleep and Fight Insomnia.