Distar reading method

DISTAR and the Initial Teaching Alphabet–a system of teaching reading that didn’t catch on

Posted on December 2, 2020 | Leave a comment

Ever hear of DISTAR? The Direct Instructional System for Teaching and Remediation—DISTAR for short—is a phonics-based reading program developed in the 1960s.

Its advantages are

- Learning goes fast at first.

- One letter corresponds to only one sound.

- It uses a one-to-one logic system little children intuitively understand.

With these advantages, why is DISTAR not widely used?

- DISTAR uses a unique alphabet called the Initial Teaching Alphabet, not the standard English alphabet.

- Teachers need to know and consistently use this alphabet for the system to work.

- Most parents have no experience with this alphabet, so they cannot help their children without instruction.

- Eventually, students must be weaned from this alphabet to the standard English alphabet, causing confusion.

- Few books are written using this alphabet.

- Children who try to use this alphabet to handwrite can wind up with impossible-to-read handwriting.

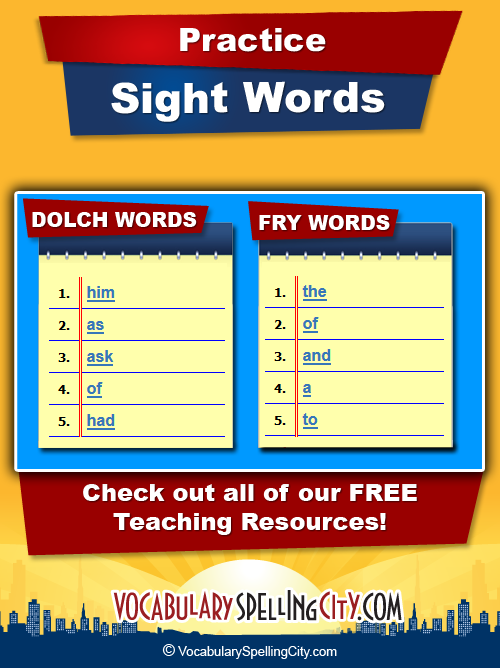

Initial Teaching Alphabet is shown below.

As you can see, some letters are the same as standard English letters, including 19 consonants and the five vowels used as closed or short vowels. Open or long vowels are written as two vowels joined. Digraphs, less used vowel sounds and certain consonant sounds are written as either double letters or single letters. But those letter shapes do not correspond to standard English letter shapes.

The Initial Teaching Alphabet was developed in the 1960s by Sir James Pitman. He hoped the alphabet could help children learn to read easier than using a traditional alphabet.

This alphabet uses a distinct typeface developed specifically for it. All letters are considered lower case. When capitals are needed, a larger version of the lowercase letter is used.

Because children needed to learn two alphabet systems in the primary grades if they learned using the Initial Teaching Alphabet and DISTAR , these systems were not widely used. During the 1960s, the teaching of reading was switching from a phonetic approach to a whole language approach, another reason for DISTAR’s and the Initial Teaching Alphabet’s lack of support.

Today research shows that a phonetic approach is the best way to teach young children to read.

Like this:

Like Loading...

This entry was posted in ABC's, DISTAR, Initial Teaching Alphabet. Bookmark the permalink.

-

Search for:

Is your child ready for essay writing? I tutor online middle and high school essay writing. Click the graphic above for my “how to” blog and tutoring information.

You may think revising means finding grammar and spelling mistakes when it really means rewriting—moving ideas around, adding more details, using specific verbs, varying your sentence structures and adding figurative language.

Learn how to improve your writing with these rewriting ideas and more. CLICK ON the photo above for more.

Learn how to improve your writing with these rewriting ideas and more. CLICK ON the photo above for more.Comical stories, repetitive phrasing, and expressive illustrations engage early readers and build reading confidence. Each story includes easy to pronounce two-, three-, and four-letter words which follow the rules of phonics. The result is a fun reading experience leading to comprehension, recall, and stimulating discussion. Each story is true children’s literature with a beginning, a middle and an end. Each book also contains a "fun and games" activity section to further develop the beginning reader's learning experience. CLICK ON the book collection above for more.

CLICK ON the painting above for Mrs. A's most recent artwork.

Follow this Blog via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

Join 96 other followers

Want a blog feed?

RSS - Posts

RSS - Comments

-

Recent Posts

- 1/3 of US children are good readers as reading ability declines

- 1651 book titles targeted to be banned in 2022

- Two games make phonics fun for beginning readers

- Do typefaces specifically designed for readers with dyslexia really help them to read faster or better?

- What fonts might help dyslexic readers read better?

Categories

CategoriesSelect Categorya right to learn to readABC’sacademic vocabularyADHDalternate perspectivesannotating textsarticlesasking questionsautismAward Winning Booksbanned booksbeginning readersblendsboard booksBook Apps for Early Readersbooks for beginning readersbooks on bikescolored pencilsComicphonics viewerscommitted parejtsCommon Core Standardscompound wordscomprehensionconsonantscoordinating conjunctionscovid slidecritical thinkingcursive handwritingCVC wordsdiagramsdigraphsDISTARdistinguishing b from dDolch wordsdouble vowel wordsdyslexiaearly chapter booksearly childhood educationeBooksEnglish as a second language (ESL)English grammarEnglish Language Learners (ELL)essay writingexceptions to phonics rulesExplode the Codeeye tracking problemsFANBOYSfiction readingfigurative languagefluencyfunny pagesGoogle Docsguessing at wordsguided reading levelsHandwritinghistory of teaching readinghomeschoolinghomework tipsHooked on Phonicshow to make learning funHow to Write a 5th Grade (or any other grade) essayhyperactivityidiomsillustrated booksinferencesInitial Teaching Alphabetinternal reward systemskenesthetic learningkeyboardingkindergarten readinesskinesthetic lerningknowing when to quitlearninglearning in infancyletter soundsletter tileslexile scorelisteningliteracyLittle Free Librarylong vowelsmain idea in a reading passageMcGuffey Readersmethods of teaching readingmethods of teaching spellingmethods of teaching vocabularymixing up lettersmodes of educationmultitasking when teachingmyopiaNate the GreatNational Assessment of Educational Progressnews stories for young readersNo Child Left Behindnonfiction readingopt outoutperforming schoolsparent choice in eucationphonemesphonicspicture booksPoint of Viewpractice reading skillsprereading skillsprimitive reflexesprinted handwritingpronoun-antecedent agreementpronunciation of wordsQuizreadiness for the next gradeReading & Writing Tutorreading comprehensionreading disabilitiesreading in kindergartenreading readiness. Reading Recoveryreading researchreading strategiesreading testsreading timereading tipsreading-writing connectionrecord keeping of child’s educationrepeating a grade in schoolscreen time for young childrensensory integrationsentence structureshort vowelssight wordssilent “e” wordsSimple View of Readingsinging as a reading skillskipping wordsslurring words read aloudsolutionssounds of Englishspacing of letters in wordsSpellingspoken language milestonessports v. academicssummer slidesyllablessystematic phonics instructionteaching in a pandemicteaching onlineteaching tipstechnologythe letter Qqthe nation’s report cardthird grade retentionthree cueingtutoringtypefaces / fontsunderstanding ShakespeareUS educationusing gestures to learnvocabularyvowelswhole languageWhy Johnny Can’t Readwordless booksworking memoryWorld Read Aloud Daywriting contestwriting makes better readersZoom

Reading Recoveryreading researchreading strategiesreading testsreading timereading tipsreading-writing connectionrecord keeping of child’s educationrepeating a grade in schoolscreen time for young childrensensory integrationsentence structureshort vowelssight wordssilent “e” wordsSimple View of Readingsinging as a reading skillskipping wordsslurring words read aloudsolutionssounds of Englishspacing of letters in wordsSpellingspoken language milestonessports v. academicssummer slidesyllablessystematic phonics instructionteaching in a pandemicteaching onlineteaching tipstechnologythe letter Qqthe nation’s report cardthird grade retentionthree cueingtutoringtypefaces / fontsunderstanding ShakespeareUS educationusing gestures to learnvocabularyvowelswhole languageWhy Johnny Can’t Readwordless booksworking memoryWorld Read Aloud Daywriting contestwriting makes better readersZoom

Review: Teach Your Child To Read in 100 Easy Lessons

Read this review of Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons to learn everything you need to know before trying this curriculum!

Pin this for reference!This post contains affiliate links and I may earn a small commission when you click on the links.

What is Teach Your Child To Read in 100 Easy Lessons?

Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons by Siegfried Engelmann is a book designed to help parents teach their kids how to read. The book is divided into 100 sequential lessons. Each lesson includes a script so parents know exactly what to say to their kids, and words and stories for kids to practice reading. The lessons get more difficult as the book progresses. The lessons take kids from learning the sounds of individual letters to reading multiple page stories. The book is based on the Distar method of teaching reading.

What is the Distar method?

Distar, which stands for Direct Instruction System for Teaching and Remediation, is a system of teaching developed by Siegfried Engelmann and Wesley Becker based on their research in Illinois preschools in the 1960s. In direct instruction, teachers follow a very specific script for each lesson. Because the teacher doesn’t have to worry about what they will say, or what they should do next in the lesson, they are free to concentrate on interacting with their student. In addition, the lessons can be studied and the scripts perfected with research to make them as effective as possible. DISTAR lessons move at a slow pace and include lots of review.

In addition, the lessons can be studied and the scripts perfected with research to make them as effective as possible. DISTAR lessons move at a slow pace and include lots of review.

What is Distar Orthography?

The book Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons uses a special set of characters to write the words that kids will be reading. These characters are an orthography, or a set of conventions for spelling or writing language. In the Distar Orthography, additional letters are added so that each letter only has one sound.

- Each vowel has 2 different letters. When a vowel is written with a line on top of the letter, kids read the long vowel sound. The letter written without the line makes the short vowel sound.

- Some extra joined letters are added for blended sounds. Ch, oo, qu, sh, th, and wh are all written with the 2 letters connected to show that those two letters work as a team to make only one sound.

- Silent letters are written smaller than the other letters in the word.

Why Use Distar Orthography?

When kids are first learning to read, this alternate Distar orthography can be really helpful to make a confusing language like English make more sense. This is the main reason that the book uses Distar orthography- to help kids understand the sounds that letters make. However, it can be tricky for kids to read other books at first, as they become used to seeing the Distar orthography. As the book progresses, the lessons slowly transition to using standard letters to replace the Distar orthography in the text.

What kind of experience do I need?

The great thing about using a book like Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons that follows the Distar Direct Instruction method is that you don’t need any teaching experience or specialized knowledge in teaching reading to teach your child using this resource. Because the lessons are organized in the book with a script for each one, you will just open the book to the next lesson and read the script to your child. No lesson planning or prep work is required. This makes the book a great starting point for families that are new to homeschooling.

No lesson planning or prep work is required. This makes the book a great starting point for families that are new to homeschooling.

How is Teach Your Child To Read in 100 Easy Lessons Organized?

Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons starts out with an introduction section that is written to the parent who will be teaching the lessons. The introduction explains how the book works and stresses the importance of following the script exactly. Because the script has been scientifically tested, the author argues that lessons will be most effective when taught exactly as presented. The introduction also explains the characters used in the Distar Orthography and includes a helpful chart for pronouncing all the letter sounds correctly.

The main portion of the book is divided into 100 lessons. The lessons are designed to be taught one per day over the course of several months. Each lesson includes both the script and the passages for kids to practice reading, together on the same pages. The book ends with a list of ideas for what kids could do now that they have completed the book. It also includes a suggested book list of next reading books.

The book ends with a list of ideas for what kids could do now that they have completed the book. It also includes a suggested book list of next reading books.

How Long Does it Take?

The book suggests that while most lessons can be completed in 12-15 minutes, it is best to plan for 20 minutes just in case. In our experience, the early lessons in the book didn’t even take that long. However, by the middle to the end of the book each lesson had a huge list of tasks and some took 45 minutes or more to finish. It worked best for us to split these lessons up into 2 or even sometimes 3 different sessions. At the end of the book, reading really “clicked” for my son, and we were able to skip parts of the lessons and concentrate mostly on reading the stories. This made the lessons go faster again.

It took us about 4 months to complete this book. During that time we were working on the lessons for about 15-20 minutes per day most days.

What age do you start teaching a child to read?

I purchased this book shortly before my son turned 4, because I wanted to learn more about how to teach reading and start exploring strategies. We started using the book shortly after my son’s 4th birthday, and finished it when he was about 4 ½. This book can be used for any child from preschool through elementary school that is learning to read.

We started using the book shortly after my son’s 4th birthday, and finished it when he was about 4 ½. This book can be used for any child from preschool through elementary school that is learning to read.

I tried this book briefly with my son a few months before we really started using it. He was easily frustrated and did not want to sit still during the lessons. I put the book away for a few months. I found that when we tried again, he was much more willing to pay attention to the lessons. If your child is struggling with the lessons on a consistent basis, it may help to put the book away for a few months and try again when they are older.

My son is definitely on the young side of the range of ages for this book. I have seen stories of this book being used successfully by kids as young as 3, and as old as 3rd grade. However, the older your child is, the more likely they will be to have success without getting frustrated. If you are in doubt about whether your child is ready, it would be a good idea to wait a bit to use the book if you can.

How are the lessons formatted?

The lessons each include a variety of different “tasks” or activities for the child to do. Common tasks for kids in the early lessons include practicing the sound for a new letter, repeating sounds they hear, sounding out words slowly, and reading by saying the words fast. By lesson 50, kids are practicing sounds and sounding out words, using rhyming patterns to read words quickly, practicing sight words, and reading short stories written using Distar Orthography. In lesson 100, kids read a 200+ word short story that is written using standard letters. The lessons also include practice writing letters, copying words, writing from dictation, and making up stories about pictures.

Another thing that is unique about Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons is the way that words are sounded out. The book teaches kids to use their finger to follow along under the words that they are reading. The book includes dots under each letter that makes a sound, and an arrow under each word. Kids will move their finger along the arrow, from dot to dot, saying a letter sound at each dot. The book stresses that it is important to connect the letter sounds together when saying the words slowly. This is a way for kids to begin to be able to sound out words on their own.

Kids will move their finger along the arrow, from dot to dot, saying a letter sound at each dot. The book stresses that it is important to connect the letter sounds together when saying the words slowly. This is a way for kids to begin to be able to sound out words on their own.

How do I Use Teach Your Child To Read in 100 Easy Lessons?

One of the best things about this book is how easy it is to use. When it is time to practice reading, all you need to do is open the book to the next lesson and begin reading the script to your child. The words that you say to your child are written in red for clarity. The book also includes directions for things you should do, such as point to specific letters, in parentheses. The book even includes information about common mistakes kids may make, and what to say to correct them if you notice those problems.

I did find that it helped to look ahead at the next day’s lesson as I was finishing the lesson each day with my son. I took about 30 seconds before putting the book away to make sure that I knew how to pronounce any new sounds that would be introduced in the next lesson. There is a helpful table at the beginning of the book that includes the correct pronunciation of each sound. This was especially useful since I’m long removed from learning any phonics myself. In the later lessons, the stories were often illustrated with a picture. The book suggested covering the picture until after the child reads the story. Each day I would take a minute to cover the next day’s picture with a sticky note as well.

There is a helpful table at the beginning of the book that includes the correct pronunciation of each sound. This was especially useful since I’m long removed from learning any phonics myself. In the later lessons, the stories were often illustrated with a picture. The book suggested covering the picture until after the child reads the story. Each day I would take a minute to cover the next day’s picture with a sticky note as well.

The author of the book provides supplementary videos and materials to help you use this book as well.

Our Experience Using Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons

I started using this book with my son shortly after he turned 4. I had purchased it several months earlier and tried it briefly. Unfortunately, it was obvious pretty quickly that he was not interested in the lessons and was struggling with them. When he turned 4 we tried again. This time, the lessons were much easier for him and his attention span was longer which helped as well.

Early lessons

At first, we found that the lessons were very easy. We were able to do multiple lessons per day and still come in under the 15-minute mark. Our biggest struggle at first was that I was trying to follow the script for the lessons exactly as it was presented. This meant that each lesson included a LOT of review. My son started to get bored with the lessons because there was so much repetition included. I found that the lessons went better once I Was willing to be more flexible with the lesson plans. If I felt that my son really understood a concept, I learned that I could skip some of the repetition with no consequences. (This is not what the introduction of the book says, by the way!) I found that my son was more patient with the lessons when I followed his cues.

We decided early on not to do any of the writing activities that accompanied each lesson. I really wanted to focus on reading, and I wanted to spend all our reading time practicing reading only. I also already had a handwriting curriculum that I loved and wanted to stick with. In addition, the handwriting lessons were teaching kids how to write lowercase letters. This was not a skill I was ready to introduce.

Middle lessons

As the lessons got more advanced, the book added more and more tasks to each lesson. By the middle of the book, some of the lessons included 10 or more tasks each. I realized that for us, this was too much for one lesson. Because my son was younger, his attention span was shorter and these longer lessons were just too much for him.

We started splitting the lessons into 2 parts and completing one lesson over the course of 2 days. This helped me to feel like we had plenty of time to get all the tasks done without rushing. When I was less stressed, I was able to be more patient with my son.

I quickly learned that trying to push a lesson past the end of his attention span was not productive. Those last few minutes were never when the good learning got done. Instead, they were almost always when one or both of us would get frustrated. For me, my relationship with my son, and the fact that I wanted him to enjoy reading, was much more important than getting the whole day’s lesson done in one day.

Instead, they were almost always when one or both of us would get frustrated. For me, my relationship with my son, and the fact that I wanted him to enjoy reading, was much more important than getting the whole day’s lesson done in one day.

Later lessons

At some point towards the end of the book, reading began to “click” for my son. He discovered that he could read other books, not just Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons. We have books available at child-level in several different rooms in our house all the time, and my son started to choose reading as an activity on a regular basis. Because he was doing so much practicing outside of our formal reading lessons, the lessons in the book started to get very easy for him again. By the time we reached the end of the book, we were just reading the stories and skipping all the extra practice activities- because he didn’t need them! He could read!

How Will I Know if this Program is Working?

One of the biggest signs that the program is working is that lessons are mostly fun to do, and not a huge struggle. Because the book includes so much review, the lessons should never seem hard to your child. If your child is struggling with the lessons or really resisting doing them, it might be a sign that they are too young or something else is going on. If possible, it might help to put the book away for several months and try again. During that time, you can focus on making sure your child knows the sounds of all the letters. This is a great way to prepare them for success with Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons.

Because the book includes so much review, the lessons should never seem hard to your child. If your child is struggling with the lessons or really resisting doing them, it might be a sign that they are too young or something else is going on. If possible, it might help to put the book away for several months and try again. During that time, you can focus on making sure your child knows the sounds of all the letters. This is a great way to prepare them for success with Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons.

What Should We Do After Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons?

The book claims that after completing all 100 lessons, kids will be reading “on a solid second grade level.” The end of the book includes a suggested reading list of a few books that kids who have finished the 100 lessons might enjoy reading. We found that after spending so much time reading out of a reading curriculum, it was fun to find some “real” books that my son could read. He was so excited to see his skills from Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Days transfer to stories that he knew! We were able to take advantage of our library’s easy reader section to find a variety of books that were appropriate for his reading level. We also celebrated by taking him to the library to get a library card of his own!

We also celebrated by taking him to the library to get a library card of his own!

One Year Later

At the time of writing this review, it has been about a year since we finished the last lessons in Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons. My son has continued to progress in reading, mostly on his own. I have been very intentional to make sure that he has access to books that are at an appropriate reading level for him. However, we have not needed to spend time drilling phonics or sight words since finishing Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons.

After a lot of research, I chose Learning Language Arts Through Literature as our curriculum this year. We are using both the blue book for 1st grade and the red book for 2nd grade. We are focusing mostly on grammar and vocabulary but enjoying the readers as well. I found that my son is WAY beyond grade level in reading and phonics skill, but has no experience in the other areas of language arts. Because of this, we are taking this year to practice some of those other areas.

Because of this, we are taking this year to practice some of those other areas.

Pros and Cons of Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons

Pros of Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons

- It is easy to use.

- No advance planning or prep work is required. Simply open the book to the next lesson and you are ready to begin.

- No knowledge or experience teaching reading is required. Just follow along in the book and read the script to your child.

- The book includes simple stories with silly illustrations that are fun and motivating to new readers.

- The lesson scripts are scientifically tested to be effective.

- The book is very well organized. New concepts are presented sequentially, and lots of review is included.

- The Distar orthography helps simplify English so each letter only makes one sound, which makes reading easier to learn.

- The book is inexpensive, especially compared to the cost of other learn to read phonics systems.

Cons of Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons

- The lessons can be boring or dry for some students.

- The lessons and illustrations are black and white. There is no color in the book. (Except for the script, which is written in red)

- Because the lessons are scripted, it is easy to become more focused on following the script than following your child and meeting their unique needs.

- It takes commitment to stick with this curriculum through all 100 lessons. Kids can get frustrated if they are too young or if they get bored by the large amount of review.

- The content of a few of the lessons might not be appropriate for some families. We skipped a story about a hunter who wanted to shoot animals with a gun. There were also a few places where I needed to re-word some sections that seemed to motivate kids through shame.

- Kids who are still in the early lessons of the book can only read with Distar orthography and not regular letters.

Try Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons for Yourself

Have you used Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons in your homeschool? You can learn more about the book and purchase a copy for yourself here. If you have used this resource, please share your thoughts in the comments!

| Hon P.A. Pedagogical psychology: Principles of teaching: Textbook for higher education. - 2nd ed. - M: Academic Project: Culture, 2005. -736 p. Ref. no. below Robert L. Holm Classroom Learning and Teaching Hong P.A. Pedagogical psychology: Principles of teaching: Textbook for higher education. - 2nd ed. - M: Academic Project: Culture, 2005. -736 p. - ("Gaudeamus") This unique book on educational psychology not only includes an overview of all the main concepts of teaching and learning, but also provides practical recommendations that allow teachers to effectively improve their professional skills and, through the application of a variety of applied methods, successfully resolve .  their specific problems. their specific problems. UDC 37.0 Foreword This book is written to help educators, as well as those involved in teaching, develop their own theories of learning and teaching in order to promote professional development. The book is applied in nature, its goal is to turn psychological concepts, principles and theories into strategies and methods that contribute to solving educational problems. Recent research and theoretical developments have led to a fusion of traditional behavioral and cognitive theories of learning that has a direct bearing on learning problems. Teachers can use the achievements of both psychological directions, which are given special attention in my book. In addition, a new understanding of the biological, psychological and cultural factors on which the potential of the student depends has been developed. This book provides the basic information needed to understand how people learn—gifted and average, physically fit and not, male and female. In the course of many years of communication with teachers, I have found that - regardless of the level of experience - they prefer books on educational psychology that can be directly applied to the teaching of the subject and the formation of skills. For this reason, special chapters are devoted to the study of general educational disciplines, acquaintance with the socio- 3 values and responsibilities, as well as learning strategies and problem-solving skills that modern teachers need to instill in their students. These questions are presented, I believe, in an interesting, informative way, demonstrating that the study of educational psychology is a useful and exciting activity. Features book I tried to include in the text information about the various components of effective learning, which, in fact, is discussed. In particular, because examples and practical advice help to remember or understand new ideas, I have used numerous illustrations of teacher actions and sample curriculums to show how the content of the book can be applied in practice. Chapter content and objectives Each chapter begins with an outline of the main topics and a list of work tasks related to those topics. You can read these sections to familiarize yourself with the contents of the chapter and decide what. in it is most important. The problems at the beginning of a chapter are often included in exam papers, so it may be helpful for you to formulate possible answers to questions about these problems. Opening episodes All chapters begin with short stories or episodes related to specific learning situations. Sometimes such stories are found within chapters. They illustrate the main ideas, and I often refer to them in the text to connect the content of the book with its practical application. Marginal notes It is known that notes placed in the margins of text help to understand the content most effectively. 4 Read the text and play it later. Making your own notes when you have any ideas will make it easier for you to read the book in the future. To facilitate this process, I have left my notes in the margins of the text. Some of them are general provisions that summarize the information presented in the text; others are matters that you may consider in connection with the practical application of the foregoing. You may well add your own notes to them. Breaking off reading to review my notes or make up your own will make it easier for you to work through the text, as well as review the material later. Case study tables Wherever possible, I have given practical examples. Often they are presented in the form of tables or figures, which summarize the various methods, evidence or research data that are of direct relevance to training. Probably, viewing the material in the form of tables will allow you to systematize and subsequently to restore the necessary information. Concept maps I have often heard from students that it is rather difficult to keep in mind all the information contained in a more or less voluminous section until it has been properly digested. To help solve this problem, I have created concept maps that show the structure of each chapter. It was found that such schemes, representing a set of concepts in a hierarchical order, contribute to the systematization and integration of the material. By looking at the concept maps that are located in each chapter after the conclusion, you will see how the material you have just read fits into a structure. Each concept map is designed to show how the content of each chapter can be useful for your personal theory 5 I Foreword learning and teaching. You can try to build your own concept maps or adapt mine to suit your ideas and interests. Tasks Each chapter contains one or more activities designed to help you practice the material and help you become an active reader who can use the information in the book for your own purposes. Literature I have selected the references that are mentioned most often in this chapter and placed them after the assignments. These links will allow you to explore the topics discussed in the chapter in more depth. Of course, all references mentioned in the text can be found at the end of the book. Thematic structure The book is organized in such a way that the information necessary for the current teacher to understand the processes of learning and teaching is presented in a certain sequence. First, we must0009 understand the student, and this "goal is devoted to the first three chapters. Chapter 1 deals with the main definitions adopted in the psychology of learning, and the historical development of this field of knowledge. The second part examines the three most important learning theories, which are directly relevant to teaching practice: operant learning (chapter 4), social learning (chapter 5) and cognitive information processing (chapter 6). Once we understand how learning happens and what the most relevant theories say about learning, we can look at learning in relation to certain types of academic disciplines. In the third part of the book, where 6 we are talking about learning and teaching, exploring the various outcomes of the educational process - from the point of view of how learning occurs. Particularly highlighted are educational methods that can contribute to the assimilation of the content of the academic discipline. Thanks Although I am considered the sole author of this book, it was not created by me alone. I had a lot of people who helped me: some helped in writing the text, others gave me an incentive to work, shared their ideas and knowledge that influenced the content. In addition, when needed, I received moral support. I would like to give special thanks to Dr. Virginia Blanford, editor of my book, who, despite the fact that work on the book began before her arrival, gave me unwavering support, advice and encouragement in choosing my own path; and Linda Witzling, production editor, who has helped me out many times. Jeanne Elsworth, Northern Arizona University; William J. Neji, Illinois State University; Sharon McNeely, Northeastern Illinois University; Sarah Peterson, Northern Illinois University; Elizabeth Popil, University of Idaho; Albert I. Rourke, University of Colorado Boulder, 7 who thoroughly read the first drafts of the book and whose suggestions greatly improved the final version, as well as to my colleagues at the University of Kansas who, by reading the text, stimulated the development of the ideas contained in it, or simply encouraged me - especially Robert Harrington, Peter Johnsen, William Lasheer, Neil Salkind, Everlyn Schwartz and Dick Tracy. I thank those who made the effort to decipher my often obscure handwriting and prepare the manuscript for printing—Peggy Billings, Jana. Maltby, Maria Martin, Deborah Wroughton and Judy Turner. Many thanks to my parents, Walter and Margery, who once instilled in me a love of learning and, moreover, of life; to my wife, Norma, and my sons, Robert and Keith, who not only treated me with unfailing love and support, but served as an example to me daily of how perseverance and patience lead to success; and also to my students with whom I have worked over the years and who have taught me much more than I have taught them. Part I UNDERSTAND STUDENT The importance of learning theories for teachers Learning and teaching Why study learning? Components of the learning process Why study learning theories? What is a theory? ' Early theories of learning Philosophical foundations Early research on learning Structural or functionalism? Emergence of Behaviorism Thorndike and the first theory of learning The emergence of cognitive theories: Gestalt psychology Gestalt psychology's perspective on learning Explaining learning: Gestalt psychology and behaviorism Chapter tasks 1. Explain the benefits of learning theories for teachers. 2. Derive a definition of teaching that will show its difference from development, activity and thinking. 3. Justify the use of theory in explaining how people learn. 4. Consider the philosophical interpretations of knowledge presented by Plato, Aristotle, Locke, Kant and Mill. 11 5. Compare structural and functional approaches to learning. 6. Explain Thorndike's laws of learning and their relation to educational practice. 7. Compare the points of view on learning developed by behaviorism and Gestalt psychology. 1 The importance of learning theories for teachers As you begin to read this book, you may shake your head and say to yourself, “Why do I need this? We can only get acquainted with a lot of theories that do not even agree with each other. I don't need them to be a good teacher." And you're not the only one who thinks so. This is the same opinion held by many of the teachers who begin to study the theory of learning. The apparent irrelevance of such theories was best expressed by a teacher I met a few years ago in class, whose work was generally quite successful. - Dr. Hong, Psychology - it's interesting, but I don't think I need this course. - Why is that, Bill? - Well, first of all, I teach social science, and these theories are about how monkeys learn to get bananas or how someone solves a math problem. - Um, anything else? - As much as you like. I teach eighth graders in a small rural town. I have to do a lot just to get them interested. And in these theories, all students, apparently, love to learn and always find the right solutions. And in my class, and with my friends teachers, everything happens in a completely different way. Do you want me to continue? - Until you've said all you can. - Okay, I already know how to teach; to that It same in the teacher's guide that I used 12 zuyu, it is quite easy to explain how to convey the content of the course. - I understand, continue. - Apparently, each theory explains only one of the types of learning, w\u only one of its components. As if all of them, like blind men, describe different parts of the elephant. And each inspires something of its own. - You are probably right, but don't you think that there may be reasons for this? - Maybe g but I would like scientists to reconsider all these theories and come up with one that will really be useful to me. And now I guess all I need to know is - who my students are, what the content of the course is, and what the school wants to teach them. Fortunately, we were interrupted and the conversation ended before my blood pressure reached a critical level. My first reaction was to feel irritated and frustrated at my inability to explain (or "inspire," as my interlocutor put it) the importance of being introduced to learning theories. This exchange of opinions, as well as other similar conversations in which I have had the opportunity to participate, are, in part, the reason for the appearance of this book. I believe that it is through understanding how a person learns, and only so, that one can become a good teacher. In addition, instead of relying on one theory, which is each D° G0 is OWN PERSONAL will give us answers to all questions, we are theO p IA the teachings should rather recognize that at present there is no best description of the learning process, just as there is no "best" 13 way of teaching. The suggestion that a good teacher does not need theories in order to carry out his work overlooks the personal theory of learning, which in hidden is available to every teacher. This implicit theory is a set of beliefs and hypotheses that serve to guide our actions, but may not be completely obvious to us (Gage, 1963). While not necessarily organized along the lines of traditional theories, these vaguely articulated beliefs nonetheless influence our behavior in a variety of situations. Implicit theories are built on the basis of our past experience. If I ask you to "teach me something you know," then you immediately engage the corresponding implicit theory. To make sure of the right choice, you can find out the topic that interests me. In addition, you may consider that you are able to explain or show what learning material you have, how I might respond, and how you would evaluate my progress and provide feedback. Not only do doctrine theories help us build more useful and accurate personal theories, they also form the context from which we observe and interpret events. Teachers with theoretical knowledge can approach an unfamiliar situation using a system of ideas that will prompt them with the appropriate course of action. Faced with a difficult student, a teacher familiar with B.F. Skinner (1953) may try to find out what events in the child's environment cause such behavior, and then consider what changes can be made to this environment. Other teachers may approach the problem with a different theoretical attitude; there are various al- Chapter 1. Learning and teaching ternatives. Understanding at least one theory already provides a basis for considering some problem. A good theory—that is, a theory that offers a mechanism for explaining student behavior—increases the likelihood that the teacher will be able to develop appropriate methods for solving problems and achieving goals. Learning and teaching Does teaching exist independently of teaching? Can we say that there is teaching if no one is learning at the moment? I remember my college national history teacher whose only method of teaching was to read his material to our stream of about 60 students. At 9 a.m. sharp, he entered the auditorium, stood in the pulpit, put his notes in order, and began to read. He did not take his eyes off them, completely ignoring those present. One spring morning, out of spite, someone sent a note around the hall asking everyone to quietly start leaving the audience at 9.twenty. At first, chuckling and hesitating, they all left; 15 minutes later the hall was empty. Our teacher, completely immersed in the events of the Reconstruction period, did not notice at all that no one was left in the audience. A student who lingered nearby watched as the red-faced teacher left her 10 minutes after everyone had left. Was the absent-minded professor “teaching” all the time when there was not a single student in the hall? This rather revealing example illustrates the relationship teaching and learning. 15 Part I. Understanding the student deliberately consider himself a teacher, without taking into account the nature and result of the learning process. teaching is carried out only in interaction Teaching J interconnected teachers and students who are trying to learn information with the teaching, rules or skills. Why study the process of learning? In the process of thinking about the relation of teaching to learning, it becomes immediately obvious that anyone who is interested in teaching must be aware of how the process of learning takes place. I once interviewed 160 teachers, wanting to know what they wanted to achieve by attending classroom learning theory courses. The following questions, which show what kind of information teachers can gain from studying the process of learning, make up a list of the ten most frequently asked questions. After reviewing it, you can note which of these questions you have encountered yourself. How can I draw students' attention to my lectures? To his suggested reading material? How can classes be arranged in such a way that students do not interfere with each other and treat classes truly responsibly? How can I be sure none of my students will fail one of those government tests that shows some high school students don't know where Mexico is and can't remember what century the Civil War was in? How can I help my students express themselves clearly? Why is it so difficult to achieve cooperation between students? 10 How can I get my students interested in learning? How can I help my students to use what they already know, what questions could you use when they are faced with Add during the course of learning? new problem? Why don't my students understand what they are reading? Why do some of my students have such low self-esteem? How can I give my students confidence in their own abilities? 16 As these questions show, teaching in the classroom has many facets. Learning is thought to begin before birth, when the embryo moves involuntarily in the uterus as a result of changes in environmental conditions such as pressure or temperature (Barclay, 1985). Teaching does not stop until death. The amount of diverse information received by a person during his life can make up a whole library. In order to understand the breadth and complexity of the knowledge and skills acquired by man, we must consider the factors that influence this process ess, and theories, who are trying to explain it. Components of the learning process There is no such definition applicable to the concept of learning, which would be accepted by all psychologists, teachers, theorists and researchers. Most will agree that learning involves acquiring elements of new knowledge, skills, beliefs, feelings and actions, as well as changing an existing one. 17 Initially, the teaching depends on a certain type of external conditions or experience. The process of learning, the factors influencing changes in this process, and the nature of the external conditions affecting it, can be the subject of heated debate. As the various theories of doctrine are examined in the following chapters, the reasons for these differences will become apparent. Now it is important for us to identify the main features of the learning process. Teaching suggests certain changes in behavior or the ability to implement these changes in the future. If Charles can complete the entire sequence of steps required to change a wheel on a car, we can say with certainty that he has learned how to change a wheel. Often we acquire knowledge and skills that we do not have to immediately demonstrate to others, as it happens to you now when reading this text. In certain situations, we simply observe the actions of others, and then we can reproduce them if necessary. This type of learning, known as observational learning, is a key concept of social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), which we will explore in detail in chapter five. Learning must be accompanied by relatively constant changes in behavior. This aspect of learning excludes changes in behavior that are temporary or due to outside influences. For example, even the most skilled musicians say that there are days when 18 when their game is full of mistakes and their attention is scattered. It would hardly be true to say that they "forgot how" to play. This is likely due to factors such as fatigue, illness, alcohol use, drug use, or lack of motivation. Behavioral changes do not have to persist throughout life; after all, over time we do forget some things. Although there is no set time frame to clarify the concept of persistence, changes in behavior that last only a few seconds cannot be considered learning. Learning — a process, the presence of which we can judge by changes in the performance of actions. Learning is an internal process that cannot be directly observed from outside. We can capture changes in behavior that give us reason. conclude that learning takes place, changes occur J Behavior transformation can lead to in appear in an increase in the ability to act to perform certain actions. For example, when we practice adding single digits, our results are likely to gradually improve. Note how the number of correctly solved addition problems by Sarah and Edwin increased over the course of five weeks.

Assuming that the problems used in testing were invariably of the same type, we can conclude that both children learned to add numbers.  Their results gradually increased over the five weeks. Based on this, the teacher can conclude that there is progress in learning. We also note that the improvement was not permanent: in one of the weeks, Sarah's results worsened. Such lapses are not uncommon in most skills. *~ We can all remember the tasks, the ability to ; Their results gradually increased over the five weeks. Based on this, the teacher can conclude that there is progress in learning. We also note that the improvement was not permanent: in one of the weeks, Sarah's results worsened. Such lapses are not uncommon in most skills. *~ We can all remember the tasks, the ability to ; 19 Part I. Understanding the Learner , the performance of which not only did not improve with us, but became even worse. The author of this book, for example, experienced such lapses in learning to play golf, when within a short period of time after instruction there were more inaccurate pitches than ever. Since we infer whether learning has taken place on the basis of the actions taken, it would be useful to pre-determine a certain indicator or criterion, based on To determine from which could be concepts of learning needed r J relevant criterion Child, what change in behavior is enough to serve indicator of learning. Learning is through exercise or experience. This characterization suggests that changes in behavior due to genetics, as well as age-related changes, should be distinguished from learning. One spring morning, my six-year-old son proudly asked me to “see what he had learned to do” while hanging from a low branch of a tree. The boy had only grown three inches in the last few months, and I said authoritatively, "I think you've grown taller and stronger." Although my son apparently did not notice this difference, this incident reminds us that human behavior also changes in the course of biological development. However, the learning-development dichotomy is not at all so obvious. 20 Catalog: full txt zhүkteu/download 7.19 Mb. Uznyzben Bөlis: |

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | |

| week | week | week | week | week | |

| Sarah | 13 | 17 | 16 | 19 | 23 |

| Edwin | 14 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 22 |

Assuming that the problems used in testing were invariably of the same type, we can conclude that both children learned to add numbers.

Their results gradually increased over the five weeks. Based on this, the teacher can conclude that there is progress in learning. We also note that the improvement was not permanent: in one of the weeks, Sarah's results worsened. Such lapses are not uncommon in most skills. *~ We can all remember the tasks, the ability to ;

Their results gradually increased over the five weeks. Based on this, the teacher can conclude that there is progress in learning. We also note that the improvement was not permanent: in one of the weeks, Sarah's results worsened. Such lapses are not uncommon in most skills. *~ We can all remember the tasks, the ability to ; 19

Part I. Understanding the Learner

, the performance of which not only did not improve with us, but became even worse. The author of this book, for example, experienced such lapses in learning to play golf, when within a short period of time after instruction there were more inaccurate pitches than ever.

Since we infer whether learning has taken place on the basis of the actions taken, it would be useful to pre-determine a certain indicator or criterion, based on

To determine from which could be

concepts of learning needed r J

relevant criterion Child, what change in behavior is enough to serve

indicator of learning. Should Sarah and Edwin's teacher stop teaching them addition, assuming they have already learned it? Would you change your mind if you learned that the test on which the scorecard was based consisted of 50 items? The question of how to define and how to evaluate learning based on the results of the actions performed, we will consider in more detail later.

Should Sarah and Edwin's teacher stop teaching them addition, assuming they have already learned it? Would you change your mind if you learned that the test on which the scorecard was based consisted of 50 items? The question of how to define and how to evaluate learning based on the results of the actions performed, we will consider in more detail later.

Learning is through exercise or experience. This characterization suggests that changes in behavior due to genetics, as well as age-related changes, should be distinguished from learning. One spring morning, my six-year-old son proudly asked me to “see what he had learned to do” while hanging from a low branch of a tree. The boy had only grown three inches in the last few months, and I said authoritatively, "I think you've grown taller and stronger." Although my son apparently did not notice this difference, this incident reminds us that human behavior also changes in the course of biological development.

However, the learning-development dichotomy is not at all so obvious.

Other features that contribute to a more effective reading of the book are briefly highlighted in the following sections.

Other features that contribute to a more effective reading of the book are briefly highlighted in the following sections.  0006

0006  The tables will also be helpful in considering your own role as a teacher in relation to the content of the book.

The tables will also be helpful in considering your own role as a teacher in relation to the content of the book.

In chapter 2, the learning process is considered from a biological and physiological point of view. In Chapter 3 discusses developmental factors that influence learning, such as language, cognition, culture, gender, and learning style.

In chapter 2, the learning process is considered from a biological and physiological point of view. In Chapter 3 discusses developmental factors that influence learning, such as language, cognition, culture, gender, and learning style.  In Chapter 7, I address subject areas such as reading, writing, math, science, and social studies. Chapter 8 discusses motivation and its role in the learning process. Chapter 9the process of learning values is analyzed, and chapter 10 deals with the development of learning strategies and skills for independent problem solving. Chapter 11 focuses on the learning needs of students who lack certain abilities. Finally, in the last part, chapter 12, the results are summed up, the main ideas are summarized, and the connecting threads of the book are revealed.

In Chapter 7, I address subject areas such as reading, writing, math, science, and social studies. Chapter 8 discusses motivation and its role in the learning process. Chapter 9the process of learning values is analyzed, and chapter 10 deals with the development of learning strategies and skills for independent problem solving. Chapter 11 focuses on the learning needs of students who lack certain abilities. Finally, in the last part, chapter 12, the results are summed up, the main ideas are summarized, and the connecting threads of the book are revealed.  I would also like to thank:

I would also like to thank:

We were going to discuss the early theories of learning. The conversation went something like this:

We were going to discuss the early theories of learning. The conversation went something like this:  I do not see anything new that I could learn from these theories - my guidance is enough for me.

I do not see anything new that I could learn from these theories - my guidance is enough for me.  I had no reason to be too angry with this young man, for I felt that he was only expressing what others, out of timidity or out of politeness, did not dare to say aloud. However, I did find in his comments a serious misunderstanding not only of the learning process, but also of the teaching process.

I had no reason to be too angry with this young man, for I felt that he was only expressing what others, out of timidity or out of politeness, did not dare to say aloud. However, I did find in his comments a serious misunderstanding not only of the learning process, but also of the teaching process.  Teachers can benefit from different theories of knowledge, since each point of view complements their views on how this extremely complex process proceeds.

Teachers can benefit from different theories of knowledge, since each point of view complements their views on how this extremely complex process proceeds.  Whatever decision you make will depend on your personal theory of how people learn and will not be random at all. This theory will guide your thoughts.

Whatever decision you make will depend on your personal theory of how people learn and will not be random at all. This theory will guide your thoughts.

Probably everyone will agree that in the absence of students listening to him, our professor could not teach - he talked to himself. The word teach can be defined as "to encourage someone to learn by example or experience" {American Heritage Dictionary, 1985). This definition suggests a relationship between the act of teaching and student behavior. Lecturer-. learning and teaching are inextricably linked. Too self-

Probably everyone will agree that in the absence of students listening to him, our professor could not teach - he talked to himself. The word teach can be defined as "to encourage someone to learn by example or experience" {American Heritage Dictionary, 1985). This definition suggests a relationship between the act of teaching and student behavior. Lecturer-. learning and teaching are inextricably linked. Too self-  If we don't understand the learning process, our teaching can be like an absent-minded professor.

If we don't understand the learning process, our teaching can be like an absent-minded professor.  Of course, traditional academic skills are important, but good behavior in society, respect for yourself and others, and an interest in the school and what it offers, also deserve special attention. If we were to identify all the different types of teaching that are practiced in schools, our list would be much longer. Suffice it to say that, in most cases, teachers are responsible for learning outcomes that must be recognized before teaching can begin.

Of course, traditional academic skills are important, but good behavior in society, respect for yourself and others, and an interest in the school and what it offers, also deserve special attention. If we were to identify all the different types of teaching that are practiced in schools, our list would be much longer. Suffice it to say that, in most cases, teachers are responsible for learning outcomes that must be recognized before teaching can begin.

In this case, there is a fact of teaching, that is, one can directly state its existence. Suppose that Charles, while attending a driving course, watched a video on how to change tires and read about it in a special manual, but never performed this operation in front of an instructor. We can establish the fact of learning based on the fact that a change in behavioral abilities has occurred. Of course, if after that Charles loses parts, fails to handle the jack, and eventually has to call emergency services, we will have to abandon our belief that he has mastered this skill.

In this case, there is a fact of teaching, that is, one can directly state its existence. Suppose that Charles, while attending a driving course, watched a video on how to change tires and read about it in a special manual, but never performed this operation in front of an instructor. We can establish the fact of learning based on the fact that a change in behavioral abilities has occurred. Of course, if after that Charles loses parts, fails to handle the jack, and eventually has to call emergency services, we will have to abandon our belief that he has mastered this skill.

When learning

When learning  Should Sarah and Edwin's teacher stop teaching them addition, assuming they have already learned it? Would you change your mind if you learned that the test on which the scorecard was based consisted of 50 items? The question of how to define and how to evaluate learning based on the results of the actions performed, we will consider in more detail later.

Should Sarah and Edwin's teacher stop teaching them addition, assuming they have already learned it? Would you change your mind if you learned that the test on which the scorecard was based consisted of 50 items? The question of how to define and how to evaluate learning based on the results of the actions performed, we will consider in more detail later.  Caring parents often believe that they teach their child to speak by repeating the words "mom" or "dad" that the child reproduces in his own way. Less biased observers state the spontaneous speech activity of the baby, in which various sounds are made without any or obvious external influence. The vocal apparatus-611 develops in such a way that the child can produce

Caring parents often believe that they teach their child to speak by repeating the words "mom" or "dad" that the child reproduces in his own way. Less biased observers state the spontaneous speech activity of the baby, in which various sounds are made without any or obvious external influence. The vocal apparatus-611 develops in such a way that the child can produce  -736 p.-03-2006

-736 p.-03-2006

These questions are presented, I believe, in an interesting, informative way, demonstrating that the study of educational psychology is a useful and exciting activity.

These questions are presented, I believe, in an interesting, informative way, demonstrating that the study of educational psychology is a useful and exciting activity.

By looking at the concept maps that are located in each chapter after the conclusion, you will see how the material you have just read fits into a structure. Each concept map is designed to show how the content of each chapter can be useful for your personal theory

By looking at the concept maps that are located in each chapter after the conclusion, you will see how the material you have just read fits into a structure. Each concept map is designed to show how the content of each chapter can be useful for your personal theory

In the third part of the book, where

In the third part of the book, where  I had a lot of people who helped me: some helped in writing the text, others gave me an incentive to work, shared their ideas and knowledge that influenced the content. In addition, when needed, I received moral support. I would like to give special thanks to Dr. Virginia Blanford, editor of my book, who, despite the fact that work on the book began before her arrival, gave me unwavering support, advice and encouragement in choosing my own path; and Linda Witzling, production editor, who has helped me out many times. I would also like to thank:

I had a lot of people who helped me: some helped in writing the text, others gave me an incentive to work, shared their ideas and knowledge that influenced the content. In addition, when needed, I received moral support. I would like to give special thanks to Dr. Virginia Blanford, editor of my book, who, despite the fact that work on the book began before her arrival, gave me unwavering support, advice and encouragement in choosing my own path; and Linda Witzling, production editor, who has helped me out many times. I would also like to thank:  I thank those who made the effort to decipher my often obscure handwriting and prepare the manuscript for printing—Peggy Billings, Jana. Maltby, Maria Martin, Deborah Wroughton and Judy Turner.

I thank those who made the effort to decipher my often obscure handwriting and prepare the manuscript for printing—Peggy Billings, Jana. Maltby, Maria Martin, Deborah Wroughton and Judy Turner.  Explain the benefits of learning theories for teachers.

Explain the benefits of learning theories for teachers.  This is the same opinion held by many of the teachers who begin to study the theory of learning. The apparent irrelevance of such theories was best expressed by a teacher I met a few years ago in class, whose work was generally quite successful. We were going to discuss the early theories of learning. The conversation went something like this:

This is the same opinion held by many of the teachers who begin to study the theory of learning. The apparent irrelevance of such theories was best expressed by a teacher I met a few years ago in class, whose work was generally quite successful. We were going to discuss the early theories of learning. The conversation went something like this:  Do you want me to continue?

Do you want me to continue?  And now I guess all I need to know is - who my students are, what the content of the course is, and what the school wants to teach them.

And now I guess all I need to know is - who my students are, what the content of the course is, and what the school wants to teach them.  In addition, instead of relying on one theory, which is each D° G0 is

In addition, instead of relying on one theory, which is each D° G0 is  Implicit theories are built on the basis of our past experience. If I ask you to "teach me something you know," then you immediately engage the corresponding implicit theory. To make sure of the right choice, you can find out the topic that interests me. In addition, you may consider that you are able to explain or show what learning material you have, how I might respond, and how you would evaluate my progress and provide feedback. Whatever decision you make will depend on your personal theory of how people learn and will not be random at all. This theory will guide your thoughts.

Implicit theories are built on the basis of our past experience. If I ask you to "teach me something you know," then you immediately engage the corresponding implicit theory. To make sure of the right choice, you can find out the topic that interests me. In addition, you may consider that you are able to explain or show what learning material you have, how I might respond, and how you would evaluate my progress and provide feedback. Whatever decision you make will depend on your personal theory of how people learn and will not be random at all. This theory will guide your thoughts.

twenty. At first, chuckling and hesitating, they all left; 15 minutes later the hall was empty. Our teacher, completely immersed in the events of the Reconstruction period, did not notice at all that no one was left in the audience. A student who lingered nearby watched as the red-faced teacher left her 10 minutes after everyone had left. Was the absent-minded professor “teaching” all the time when there was not a single student in the hall?

twenty. At first, chuckling and hesitating, they all left; 15 minutes later the hall was empty. Our teacher, completely immersed in the events of the Reconstruction period, did not notice at all that no one was left in the audience. A student who lingered nearby watched as the red-faced teacher left her 10 minutes after everyone had left. Was the absent-minded professor “teaching” all the time when there was not a single student in the hall?  Understanding the student

Understanding the student  After reviewing it, you can note which of these questions you have encountered yourself.

After reviewing it, you can note which of these questions you have encountered yourself.  Of course, traditional academic skills are important, but good behavior in society, respect for yourself and others, and an interest in the school and what it offers, also deserve special attention. If we were to identify all the different types of teaching that are practiced in schools, our list would be much longer. Suffice it to say that, in most cases, teachers are responsible for learning outcomes that must be recognized before teaching can begin.

Of course, traditional academic skills are important, but good behavior in society, respect for yourself and others, and an interest in the school and what it offers, also deserve special attention. If we were to identify all the different types of teaching that are practiced in schools, our list would be much longer. Suffice it to say that, in most cases, teachers are responsible for learning outcomes that must be recognized before teaching can begin.

In this case, there is a fact of teaching, that is, one can directly state its existence. Suppose that Charles, while attending a driving course, watched a video on how to change tires and read about it in a special manual, but never performed this operation in front of an instructor. We can establish the fact of learning based on the fact that a change in behavioral abilities has occurred. Of course, if after that Charles loses parts, fails to handle the jack, and eventually has to call emergency services, we will have to abandon our belief that he has mastered this skill.

In this case, there is a fact of teaching, that is, one can directly state its existence. Suppose that Charles, while attending a driving course, watched a video on how to change tires and read about it in a special manual, but never performed this operation in front of an instructor. We can establish the fact of learning based on the fact that a change in behavioral abilities has occurred. Of course, if after that Charles loses parts, fails to handle the jack, and eventually has to call emergency services, we will have to abandon our belief that he has mastered this skill.

When learning

When learning