Farmer brown books

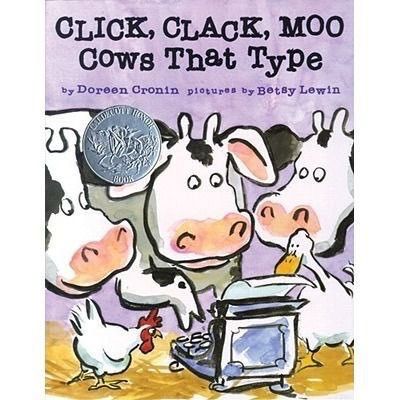

A List of Our Favorite Click Clack Books for Young Kids

This post may contain affiliate links.

Doreen Cronin the author of the popular Click Clack series. Check out this list of her Click Clack books so you don’t miss any of them.

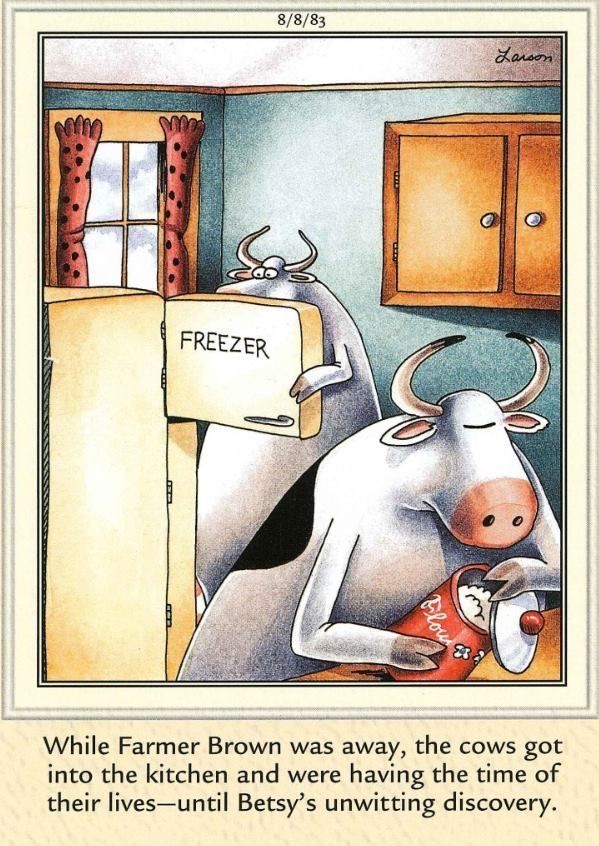

Kids of all ages will adore the animals on Farmer Brown’s farm! From ducks that won’t sleep to cows that type and all sorts of antics in between, your little ones will beg for one more read-aloud!

Below, I’ve featured just a handful of Click Clack books that kids of all ages will love!

You should be able to find them at your local library or bookstore. If you can’t find them locally, you can click each image cover to purchase them on Amazon.

Click, Clack, Moo I Love You! – Little Duck and all of her friends on the farm celebrate Valentine’s Day by inviting a newcomer to join in the fun.

Click, Clack, Quack to School! – They can stand in line (sort of), use indoor voices (perhaps), and are capable of sharing (rumor has it), so the Click Clack critters are ready for school…but is school ready for them?

Thump, Quack, Moo: A Whacky Adventure – As Farmer Brown designs the corn maze for the festival, Duck does some designing of his own. Guess who’s in for a big surprise?

Click, Clack, Surprise! – Everyone wants to look their best for the party. But Little Duck has never had a birthday before—so how better to learn how to prepare than to do what all the other animals do!

Click, Clack, Moo Cows That Type – Farmer Brown has a problem. His cows like to type. All day long he hears “ Click, clack, moo. Click, clack, moo. Click, clack, moo. ” But Farmer Brown’s problems get bigger when his cows start leaving him notes!

Click, Clack, Good Night – It’s bedtime on the farm. The cows, sheep, and chickens are all tucked in and snoozing away. Except for…Duck. So Farmer Brown sings him a song…reads him a book…turns on the white noise machine…and even debates the day’s top stories. But Duck just won’t tuck!

A Busy Day at the Farm – Follow the pigs, the cows, and Duck as they suffer through their impossibly busy schedules. From working out to having a picnic, it’s no wonder these animals are so tired at the end of the day! Readers will love watching the animals get the best of Farmer Brown.

From working out to having a picnic, it’s no wonder these animals are so tired at the end of the day! Readers will love watching the animals get the best of Farmer Brown.

Pool Party – On a hot summer day, Farmer Brown and the animals have a pool party! One by one, everyone gets cool in the pool. Splash! Splash! Splash! Everyone except the cows, that is. The cows don’t like to be splashed. The cows don’t like noise. The cows don’t like a crowded pool. Will everyone have fun in the sun?

Click, Clack, Quackity-Quack – The cows on Farmer Brown’s farm are typing again. Duck can’t wait to show everyone their latest note. Just what are they up to this time? Duck’s not telling, but if you follow the alphabet one letter at a time, you’ll find out.

Click, Clack, Splish, Splash

– Duck is about to trick poor Farmer Brown once again. While the farmer is sleeping the afternoon away, Duck and the other animals are planning a most unusual fishing trip. Sneaking past Farmer Brown is going to be as easy as 1, 2, 3!

Sneaking past Farmer Brown is going to be as easy as 1, 2, 3!

Click, Clack, Ho! Ho! Ho! – Farmer Brown is busy decorating his home in preparation for Santa’s arrival on Christmas Eve! But once again, Duck has gotten the whole barnyard stuck in quite a predicament! Will anyone be able to un-stuck Duck and save Christmas?

Click, Clack, Peep! – There’s more trouble on the farm, but Duck has nothing to do with it, for once. This time the trouble is a four-ounce puff of fluff who just won’t go to sleep, and whose play-with-me “peeps” are keeping the whole barnyard awake with him.

Giggle, Giggle, Quack – Farmer Brown is going on vacation. He asks his brother, Bob, to take care of the animals. “But keep an eye on Duck. He’s trouble.”

Click, Clack, ABC – From “ducks dashing” to “sheep sleeping,” children are sure to enjoy the alphabet like never before. Clever text and hilarious scenes are certain to help little ones learn their ABC’s!

Duck Stays in the Truck – Farmer Brown wants to go camping. He packs up the animals. He packs up his brother, Bob. The chickens want to hike. The cows want to fish. The pigs want to picnic. And Duck? Duck just wants to stay in the truck. How will Farmer Brown bring everyone together?

He packs up the animals. He packs up his brother, Bob. The chickens want to hike. The cows want to fish. The pigs want to picnic. And Duck? Duck just wants to stay in the truck. How will Farmer Brown bring everyone together?

Click, Clack, Boo! – Farmer Brown does not like Halloween. So he draws the shades, puts on his footy pajamas, and climbs into bed. But do you think the barnyard animals have any respect for a man in footy pajamas?

Click, Clack, 123 – From “1 farmer sleeping” to “10 fish ready to go,” children are sure to enjoy counting like never before. Clever text and hilarious scenes have never made counting so much fun!

Related Posts

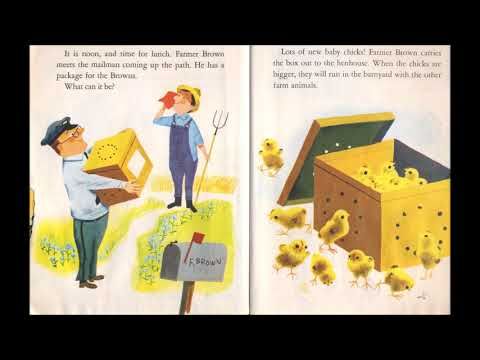

Dave Closser Farmer Brown (Paperback Book) (2021)

In case cover and title do not match, the title is correct

Tell your friends about this item:

Farmer Brown

Price

17. 99

99

Expected delivery Nov 7 - 14

Our customers say:

14-day return policy in accordance with European consumer protection law

Top ranking on Trustpilot

New wishlist...

This is a story of the loving relationship between a farmer and his sheep, pigs, goats and chickens. Farmer Brown has animals on his farm, but they are his friends, not his source of income. He has relied on his corn crop to bring in the money needed to keep the farm running. But he has never been particularly good at growing corn. One year he finally grows an amazing corn crop but loses it when torrential rains make it impossible for him to harvest. He is distraught. His chickens can feel that Farmer Brown is not himself, is sad, but don't know why. So, they come up with a scheme to try to help him out in the only way they know how. This children's story for early readers provides an opportunity for parents to engage with their children, explaining the subtle messages in the story around kindness, love and respect.

So, they come up with a scheme to try to help him out in the only way they know how. This children's story for early readers provides an opportunity for parents to engage with their children, explaining the subtle messages in the story around kindness, love and respect.

| Media | Books Paperback Book (Book with soft cover and glued back) |

| Released | February 13, 2021 |

| ISBN13 | 9781736406519 |

| Publishers | Dave Closser |

| Pages | 36 |

| Dimensions | 203 254 2 mm · 122 g |

| Language | English |

Show all

More by

Dave Closser-

Hardcover Book

Tree (2021)

Dave Closser

23.

49 Buy

49 Buy

See everything with Dave Closser (e.g. Paperback Bog and Hardcover bog)

what's wrong with the famous book about saison

Lost Beers blogger Roel Mulder analyzes the work of Ivan De Bats and tries to find out what the historical saison really was.

Would you like a saison? For thousands of beer drinkers and brewers, Phil Markowski's 2004 book Farmhouse Ales, and especially the contributions of Belgian brewer Ivan De Bats, have shaped the idea of what is and should be, the so-called "farmhouse ale". But has anyone bothered to check the sources on which this work was based? If not, then now I specifically intend to do this. Saison lovers be warned: my research may shake some of the strong beliefs you have cherished for most of your life.

I have already talked about the history of the saison before. There has been a massive resurgence of this beer in recent decades: thirty years ago it was brewed only by a few rural breweries in the province of Hainaut (in the French-speaking part of Belgium), and today, according to Ratebeer, there are 12,000 different saisons produced worldwide, and Untappdix list includes not less than 43,390.

There has been a massive resurgence of this beer in recent decades: thirty years ago it was brewed only by a few rural breweries in the province of Hainaut (in the French-speaking part of Belgium), and today, according to Ratebeer, there are 12,000 different saisons produced worldwide, and Untappdix list includes not less than 43,390.

A powerful impetus for the growth of his popularity was the book "Farm Ales", published in 2004 by American brewer Phil Markowski, who currently holds the post of head brewer at Two Roads Brewing in Stratford, Connecticut, USA. In his book, the author described various Belgian saisons of that time, gave a definition of saison, shared several secrets of making saison and its northern French counterpart, bière de garde. The essence of the whole book is this: the name "saison" speaks for itself, because it was originally a "farm ale", brewed on Belgian farms in the winter season, then, in the summer, to quench the thirst of brewers.

This book has inspired countless people around the world, and saison is now brewed everywhere from Trinidad to Tokyo by people who believe they are part of the Belgian farming tradition. This helped spread a hitherto completely unknown and probably endangered style at the time and increased the sales of this great Belgian beer, especially the one that is considered the standard - Saison Dupont, from the Dupont brewery in the small village of Tourpe in the province of Hainaut.

This helped spread a hitherto completely unknown and probably endangered style at the time and increased the sales of this great Belgian beer, especially the one that is considered the standard - Saison Dupont, from the Dupont brewery in the small village of Tourpe in the province of Hainaut.

It may therefore come as a shock to fans of Markowski's work that I claim that this influential book actually shows how strange and meager its author's knowledge of Belgian geography and history is. For example, he somehow thinks that Wallonia and the French departments of Nord and Pas de Calais were "once collectively known as Flanders." Unfortunately, this will seem ridiculous to anyone who is even remotely familiar with Belgium, its politics and linguistic problems. No less deplorable is the mythical “Kingdom of Flanders” invented by Markowski, as well as the border that, according to the author, separated Wallonia from the French departments of Nord and Pas de Calais since 1831. (I'm sorry to say this, but there never was such a kingdom, and the frontier dates back to 1713). In other words: for a Belgian to say that Wallonia is part of Flanders is the same as for an American to say that New York is part of Canada. This suggests a certain thought: if Markowski could not understand the state structure, then why should we believe his story of farmhouse ale?

In other words: for a Belgian to say that Wallonia is part of Flanders is the same as for an American to say that New York is part of Canada. This suggests a certain thought: if Markowski could not understand the state structure, then why should we believe his story of farmhouse ale?

At least Markowski thought of asking the Belgian to write a chapter on the history of the saison. Like Markowski, Ivan De Bats is a brewer. Then, working at the De Ranke brewery in Dottinies (admittedly one of the few Flemish breweries in Hainaut), he soon became one of the founders of the famous Brasserie de la Senne in Brussels. De Bats made a great contribution to the development of the Belgian market and created a great beer. In addition, what he wrote in the book "Farm Ales" has become a classic source of information about saison and its history for many.

In fact, De Bats' article is the only text I have ever seen on the history of the Belgian saison. In it, he paints a rather idyllic picture of the brewery farmers in Hainaut, who hardly ever left the farm, so to speak. That's why I was surprised when I recently discovered that most of the historical evidence I've been able to find for this beer doesn't exactly match what De Bats says in his famous article. Of course, in the past, saison was also defined as a beer brewed "in good season" (i.e., winter) that has been aged for several months or more. However, I learned that many industrial breweries in the 19th century produced and sold saison in the cities, especially in Liège, which is not even part of Hainaut. I realized that the time had come to take a closer look at De Baets' article and understand what exactly he was based on.

That's why I was surprised when I recently discovered that most of the historical evidence I've been able to find for this beer doesn't exactly match what De Bats says in his famous article. Of course, in the past, saison was also defined as a beer brewed "in good season" (i.e., winter) that has been aged for several months or more. However, I learned that many industrial breweries in the 19th century produced and sold saison in the cities, especially in Liège, which is not even part of Hainaut. I realized that the time had come to take a closer look at De Baets' article and understand what exactly he was based on.

These were the Walloon farms that De Bats considers the birthplace of saison.

Apparently De Bats talked to people at the Dupont brewery and some other (former) brewers. Perhaps he looked through their archives too. In addition, he tried several old bottles of saison and came to certain conclusions. However, it is rather strange that while De Bats admits that there are "very few records" of the rural beers he writes about, he can confidently state that today's examples are "like the beers of the past. "

"

In any case, what De Bats tells about the saison of the early twentieth century seems plausible. In 1900, the saison must have been relatively sour. In addition, it was less alcoholic than today - from about 3 to 3.5%. But over the course of the century, the saisons became less acidic and more bitter. In addition, they became more alcoholic, up to 4.5-6.5%, and as a result, saison became a beer that was brewed all year round. De Bats describes the rural flavor in which saisons were produced not only in Dupont, but also elsewhere: in the first half of the 20th century, farmers went to the local brewery several times during the winter and brewed a supply of saison. Marc Rozier of Dupont recounts that before World War II, farmers would take away bottles of saison and place them in an earthen pit where the beer was kept cold. I have no particular reason to doubt his words: I am sure that this was the case in this rural part of the region at that time. My idea, however, is that this is a very narrow view of what saison actually was.

De Bats talks about several things that I have touched on in my earlier articles, such as "making saisons in the summer was practically impossible" or that "saisons first appeared in Wallonia, in the south of Belgium, especially its production was widespread in the province of Hainaut. In short: there were certainly breweries in Belgium that continued to make it through the summer, and saison was much more typical of Liège than of Hainaut. De Bats does not support the assertion that "saisons were brewed on farms and for farmers", apparently considering this to be common knowledge. In fact, the oldest reference to this story that I found dates back to 1989 - its author is clearly based on what he was told at the Dupont brewery.

Saison and double saison sold in Liège in 1886. Evidence of the existence of a saison in Liège in the 19th century is plentiful, but there is practically none in Hainaut.

When De Bats touches on more specific things, he goes all out. For detailed information, De Bats turned to 19th and early 20th century brewing manuals and made several more or less educated guesses. I studied the same sources to understand what exactly he bases his point of view on. What follows may shock even those who are in love with the saison.

I studied the same sources to understand what exactly he bases his point of view on. What follows may shock even those who are in love with the saison.

Let's take a look at the grains used by the "farm breweries" that De Bats describes. He states that they "usually grew their own barley and malted it themselves." In support of this, De Bats speaks of the primitive ovens that were in use in Hainaut, referring to the 1879 brewing guide of Cartuyvel and Stammer. But when you look closely at this old book, you will read that is actually these gentlemen say about the beer in Hainaut: “The malt was usually prepared in breweries ... The most often used was six-row barley from the surrounding area, from the polder land (= Flanders), from Bos (Central France), Vendée (Western France) and from the banks of the Danube. Does it look like "homegrown" barley malted on a farm (not a brewery)? Not really.

De Bats also quotes French beer writer Georges Lacambre (1851) about drying malt, but for some reason selects it from the section on Walloon brown beer, a type of beer that, according to Lacambre (as opposed to saison), was commonly drunk fresh. Then De Bats, when talking about malting barley for biere de garde, refers to Wanderstichel (1905), but does not mention that the original text recommends using barley from polder lands, especially from the Cadzand region (in the Netherlands, right across the border!

Then De Bats, when talking about malting barley for biere de garde, refers to Wanderstichel (1905), but does not mention that the original text recommends using barley from polder lands, especially from the Cadzand region (in the Netherlands, right across the border!

Conclusion: Did these idyllic farms grow their own barley? Not if the sources that de Bats misquoted can be trusted.

Harvest of barley in Zeeland, one of the regions where the brewers of Hainaut bought their barley.

Now let's take a look at the hops. De Bats cites a book by Cartuywels and Stammer (1879) on the amount of hops used and notes: "Everyone knows that the Belgian hop, traditionally grown in the province of Hainaut, was used most often, since it was grown near the brewery and was the best available." Unfortunately, the authors say something completely different about the hops used in the Hainaut beers: “The hops most often used in the work came from Aalst and Poperinge.” You may be aware that these places are in Flanders, and not somewhere in Hainaut, "near the brewery. "

"

De Bats goes on to talk about using old hops, apparently to stimulate the development of lactic acid bacteria that would be incompatible with fresh hops. De Bats writes: “Farm breweries must have kept a supply of old or improperly stocked hops on hand. Old hops were used quite often, which brought saison closer to lambic." But he doesn't confirm it. And to make matters worse, lambic brewers in the 19th and early 20th centuries were actually adding fresh hops, not aged ones. It seems that De Bats takes his facts from scratch. And that is not all. As for the fermentation temperature, De Bats again quotes Lacambre from the same section on Walloon brown beer: it was a fresh beer that was very different from a saison.

I have to admit that after checking De Bats' statements, for me he just fell off his pedestal. In general, I do not believe that here he indicates the truthful sources. Even vice versa. So what went wrong? I think De Bats tried desperately to write about what happened on these farms, but found very little material. Instead, he turned to the brewing literature, which apparently talked about what professional brewers did, and then simply presented the information in his own way.

Instead, he turned to the brewing literature, which apparently talked about what professional brewers did, and then simply presented the information in his own way.

I think if De Bats had stayed closer to what the sources actually said, he would have come up with a completely different picture. At least Cartuywels and Stammer dedicate a short chapter to the beer from Hainaut, which, although it does not say anything about saison, speaks of "bierre de garde, aged or aged", which is at least close to the definition of saison . But the only real mention of saison found in old books is saison, which, according to Winderstichel, was brewed in "the province of Liège, parts of Limburg, Luxembourg and Namur, and even [attention!] in Hainaut." It was a lightly fermented (sweet) beer traditionally based on spelled. De Bats gives a footnote to the Liège saison, saying that it is a completely different beer, considering the current well-fermented (dry) saisons to be the only "real". Of course, personally De Bats may think so, but the Belgian of the 19th century almost always associated "saison" with "Liège saison". It's a little unfair that it's so easy to ignore it.

It's a little unfair that it's so easy to ignore it.

Liège, considered the home of the Saisons in the 19th century.

What's more, Yvan De Bats wants you to believe that pastoral and idyllic brewing was the norm in 19th century Hainaut, even though Wallonia was one of the most industrialized and urbanized regions in the world. He happily ignores what his sources say about industrial breweries located in cities like Ath, Shivre, Peruwelz, Tournai and Soigny. Instead, it seems to me that De Bats is trying to present an idealized vision of the countryside, and in doing so, he often paints himself into a corner, for example, when he talks about the kreusening technique used to carbonate beer. Realizing that such a complex technology, usually used by commercial breweries, cannot be mastered by simple farmers, he tries to break the deadlock, stating: “This technique was not often used in farm breweries (…) Later, this technique only spread when farm breweries were the only breweries ".

In several cases, De Bats does not cite sources at all. For example, when he says that “every brewer had his own recipe”, or that some brewers also used wheat, oats, buckwheat and malted spelled. The same is true with the use of spices - star anise, sage and coriander, or with a description of changes in the twentieth century. It's not that I find all of this unconvincing, but it would be nice if he provided links to some sources (besides who would use spices in beer, which was supposedly valued at the time for its sour wine taste? But this is another story).

Markowski's book with an article by De Bats has inspired people all over the world to drink and brew great beer, and that's great, of course. But I think that what De Bats writes hardly reflects the real history of saison or even a Dupont-like variety from the rural province of Hainaut. Clearly, the De Bats took Dupont as their starting point and used only the information that supported their story: Saison was a farmhouse beer. Think what you will, but I'll say this: I don't mind if Belgian brewers choose "cherries", but only for cherry lambic.

Think what you will, but I'll say this: I don't mind if Belgian brewers choose "cherries", but only for cherry lambic.

Baby foods - what and when to give. Is it possible to farm products?

What to add to the baby's diet besides milk after 5 months? Can farm products be used? What is better vegetables, fruits or cereals? What is the best way to make baby smoothies? We decided to find out the opinions of five well-known health experts about what should be complementary foods for a child up to a year old.

Dr. Joel Fuhrman, Family Practitioner, Nutritionist, Author of Disease-Proof Your Child: Feeding Kids Right

“I recommend starting the first meal with mashed banana mixed with breast milk or organic brown rice baby porridge diluted with breast milk or water. Gradually, you can introduce fresh fruits into the diet: apples, pears, peaches, papaya. If you offered fruit at one feeding, then next time give your baby steamed and blended vegetables, such as asparagus combined with sweet potatoes, green peas, corn, carrots.

Fruits and vegetables - exclusively organic. Strawberries and citrus fruits in the diet should be postponed until 12 months - they can provoke an allergic reaction. From 9months, you can offer pastes and urbechi from fresh nuts and seeds (except for peanuts). Before 12 months, it is better to avoid the following foods: cow's milk, butter and vegetable oil, cheese, wheat, any sweeteners, honey, salt.

Lilia Kulikova, pediatrician, highest category (3 children and 2 grandchildren).

From the age of six months, you can add various foods to your baby's diet, which can be conditionally divided into 2 groups.

Foods given with mother's milk (or formula).

- Fruit puree

Enter it first.

at 5 months - 50 gr. per day,

at 6 months - 60 gr. per day,

by the year - 100-120 gr. per day.We start with applesauce, the first time we give the baby on the tip of a spoon in the morning.

We give 4-5 days, then increase the dose. Puree should not contain sugar and it is best to make it yourself from farm products, you can of course buy a finished product, but then be sure to check the expiration date on the jar. Fresh fruits: apples, pears, it is better to bake or boil, chop kiwi and banana in a blender.

We give 4-5 days, then increase the dose. Puree should not contain sugar and it is best to make it yourself from farm products, you can of course buy a finished product, but then be sure to check the expiration date on the jar. Fresh fruits: apples, pears, it is better to bake or boil, chop kiwi and banana in a blender.

- Cottage cheese

Starting at 6 months. We begin to introduce from the tip of a spoon gradually increasing the portion, 8-9 months 25 grams, by the year we bring it to 50 grams. It is best to give cottage cheese before 18.00, if the baby does not want to eat just cottage cheese, you can mix it with fruit puree. Cottage cheese can only be given special, for children. You can buy it in any children's nutrition department.

- Yolk

We start introducing after 6 months. The yolk is given with milk or added to the vegetable mixture. You can not mix the yolk with cottage cheese. We start giving from the middle of the yolk, a portion of “2 match heads”, by the year we bring it to 1 yolk, if the child has not had allergic reactions to any products before, If they are prone to allergies, they give 1/2 yolk by the year.

When choosing eggs, check the expiration date. The child can be given both chicken and quail.

When choosing eggs, check the expiration date. The child can be given both chicken and quail.

- Juice

Juice is also given to a child from the age of 6 months. You can only give children, diluting it with boiled water 1: 1. It is best to cook fruit compotes for a child (apples, pears, prunes). Do not use raisins and sugar. Closer to the year, you can add fructose to the compote.

- Lemon

After 1 month, start adding 1-2 drops, gradually increasing to 10 drops.

Complementary food that replaces 1 breastfeeding (formula).

- Porridge

Dilute in water or breast milk (mixture) to the state of fruit puree.

Up to 8 months only corn, buckwheat, rice. We start with 20-30 ml. gradually increasing, once a laziness from a spoon. First we give in the morning, then in the evening, so that the child sleeps better, but not just before bedtime.

By 8 months we bring to 150-180 gr. We start with corn - 3 days, then buckwheat - 2 days, and then rice - 2 days, on the following days we change cereals every day. First we give porridge and breast milk. When we bring it to 180 gr, you can give it to drink with water or juice. That is, if the child eats 240 ml of the mixture (breast milk), we pour 30 ml. we breed porridge on it, and let everything else be drunk.

After 8 months you can give semolina and oatmeal, mixtures of cereals.

- Vegetables

1 day - marrow

Day 2 - zucchini + cauliflower

Day 3 - zucchini + cauliflower + potatoes

Day 4 - zucchini + cauliflower + potatoes + carrots, etc. You can also pumpkin, turnip, sweet pepper.Not allowed : red, onion, pepper, salt, garlic, cucumber, radish, green onion, mushrooms, radish, eggplant. You can not all red foods, such as strawberries, grapes, tomatoes. When choosing vegetables and fruits, give preference to yellow and green.

How to cook : Wash vegetables and keep in water for 30 minutes. What was cooked can be given for 2 days, after which we cook again. You can add vegetable oil to boiled foods from 6 months, 0.5 tablespoons, by the year a teaspoon. Vegetable puree can be given from 6 months at lunchtime. It is better to cook it yourself or mix it with ready-made (canned) mashed potatoes. We start with zucchini or cauliflower. We give as porridge - 30 ml. by 8 months up to 180 ml.

- Meat

Can be given from 7 months old, added daily to vegetable puree. Meat can be bought at the store, or you can cook it yourself from farm products. Beef, lean pork, chicken, turkey. We start with 1.3 tablespoons, bring up to 25 gr. by 9months, then 50 gr. up to a year.

- Fish

Possible from 10 months. You can use any, but low-fat grated fish - 1-2 times a week.

- Black tea

Can be given, but very weak tea leaves.

Sample feeding schedule

The schedule is made individually for each child, be sure to check with your pediatrician.

- 5 months - fruit puree, give 2 weeks, then we introduce another product, then we introduce, for example, porridge;

- 5.5 months - porridge, give 2 weeks, then introduce another product, such as cottage cheese;

- 6 months - cottage cheese, give 2 weeks;

- 6.5 months - vegetable puree, give 2 weeks;

- 7 months - meat, give 2 weeks;

- 7.5 months - yolk, give 2 weeks;

- 8 months - juice, give 2 weeks;

- 10 months - fish, give 2 weeks.

You can start introducing new food only for one product, without excluding anything that you ate before.

Kimberley Snyder, Dietitian, Bestselling Author of The Beauty Detox Solution, Founder of Glow Bio, Emerson's Mom (1yr 3m)

which he drank one teaspoon almost every day, no special purees were made for him. At about 7 months old, I started giving my son pieces of normal food that he could take and chew himself: broccoli, carrots, pumpkin, zucchini and other vegetables, steamed, and a variety of fresh fruits, cut so that the child can comfortably grab them with his fingers . And don't be put off by the fact that children this age may not have teeth - they grind food very effectively with their gums. Why did I decide to take this approach? Firstly, it is very natural: not all people in the world have blenders, and secondly, this process teaches babies to chew before swallowing; thirdly, it gives them an invaluable experience of interacting with food, its various textures and tastes, they learn to eat at such a speed and in such volume that their body requires.

At about 7 months old, I started giving my son pieces of normal food that he could take and chew himself: broccoli, carrots, pumpkin, zucchini and other vegetables, steamed, and a variety of fresh fruits, cut so that the child can comfortably grab them with his fingers . And don't be put off by the fact that children this age may not have teeth - they grind food very effectively with their gums. Why did I decide to take this approach? Firstly, it is very natural: not all people in the world have blenders, and secondly, this process teaches babies to chew before swallowing; thirdly, it gives them an invaluable experience of interacting with food, its various textures and tastes, they learn to eat at such a speed and in such volume that their body requires.

My son's favorite foods during the first few months of weaning were bananas, avocados, sweet potatoes, broccoli, zucchini, carrots, steamed green beans and yellow lentils. I don't salt my child's food."

Colin Campbell Professor of Biochemistry, Physician, bestselling author of The China Study (5 children and 7 grandchildren)

onions, carrots, asparagus, pumpkin, tomatoes, beets, celery and potatoes. Closer to the year, you can add broccoli, cauliflower, green beans - after all, these vegetables are more difficult to digest. No animal products in the diet!”

Closer to the year, you can add broccoli, cauliflower, green beans - after all, these vegetables are more difficult to digest. No animal products in the diet!”

Mark Hyman, dietitian, physician, bestselling author of Eat Fat, Get Thin

for someone later. Start with steamed sweet vegetables: carrots, sweet potatoes, pumpkins. Feel free to mix them with more neutral-tasting or slightly bitter vegetables. Also gradually introduce seasonal fruits (apples, pears, peaches). From cereals, it is better to choose millet, oatmeal, amaranth, brown rice. Closer to the first year of life, beans, peas, lentils, fish, chicken, meat, tofu will appear in the diet.

I recommend not giving dairy products to children until at least two years of age. Studies have shown that early consumption of cow's milk contributes to the development of allergies, lowers immunity and increases the chances of respiratory diseases.

Carlos González, pediatrician, author of My Baby Doesn't Want to Eat (father of three)

“Don't force your child to eat. Never, in no way, under any circumstances, for any reason.

Never, in no way, under any circumstances, for any reason.

It doesn't matter where you start complementary foods, as there is no reason to prefer this or that food. The main thing is variety, that is, the diet should include grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits.

If a child eats breast milk and then refuses fruit, then nothing terrible will happen; but if he first eats fruit and then does not want breast milk, he will lose a lot.

The only food that can satisfy all the needs of the human body at once - at least for a certain period of life - is breast milk. A newborn is perfectly fed for 6 or more months only with breast milk.

Every person, every creature has innate mechanisms that make him look for the right food and eat the right amount of it. And why are we sure that our children are deprived of these mechanisms? The babies of other species have them.

Children prefer familiar foods and are wary of new foods. This is one of the protective mechanisms that protects the child from poisonous plants and animals. If children regularly see what their parents eat, they themselves begin to eat these foods.

If children regularly see what their parents eat, they themselves begin to eat these foods.

Natalia Rose, nutrition and detox specialist, author of Detox For Women (mother of three)

“I recommend fresh raw fruit for the first meal, as they are ideal for baby's digestion. Start with easier-to-digest fruits: enter watermelon first, and then move on to melon. If you are introducing your first solid foods in winter, start with an apple, banana, and avocado.

If the baby responds well to fruits and there are no digestive problems, gradually move on to new fruits and berries. However, I do not recommend strawberries and honey in the first year of life. You may need to add a little water to denser fruits such as bananas to get the right consistency.

It is widely believed that if fruits and not vegetables are introduced into the baby's diet first, then he will have a sweet tooth and then will not want to eat vegetables at all. This is not true. Children love fruits because they are the purest and most vitamin-rich foods. The desire to eat vegetables will gradually appear, it is important not to force. Fruits are the most natural food for humans, and children naturally want them. Like mother's milk, they have a sweet taste and are very satiating.

Children love fruits because they are the purest and most vitamin-rich foods. The desire to eat vegetables will gradually appear, it is important not to force. Fruits are the most natural food for humans, and children naturally want them. Like mother's milk, they have a sweet taste and are very satiating.

After you have introduced a variety of fruits, move on to smoothies. Smoothies for toddlers are a great option: they're easy to make (you only have to use the blender once, and the smoothie lasts all day), they're incredibly nutritious, perfect for digestion, and your little one will love them.

Three ingredients must be present in the smoothie:

- Fruit

- Greenery

- Fats

Use fruit as a smoothie base, add some greens and avocado or a drop of vegetable oil that promotes brain development. Feel free to experiment with the ingredients, but make sure that the baby tastes good. Don't go overboard with the greens - if you're using the leaves instead of the green juice, make sure it's well mixed with the fruit.