Homer the learn to read method

The Essential Early Learning Program and App for Kids 2-8

Learn & Grow App

Personalized to Age and Level

Increases Early Reading Scores by 74%

1,000+ Activities Across Subjects

Start Your Trial

Playful Learning They’ll Love

Our program delivers playful learning across subjects, building the skills kids need through lessons and activities they love.

Reading

A step-by-step pathway that leads to literacy

Math

Building blocks for math confidence

Social & Emotional Learning

Tools for navigating social skills, empathy, and confidence

Thinking Skills

Brain games for big thinking

Creativity

A space for imaginations to run wild

Explore our subjects

Ready to Sign Up?

Annual

$119.88

$59.99/yr.

($4.99/mo.)

Billed yearly at $59.99

Start Free Trial

SAVE 50%

Monthly

$9. 99/mo.

Billed monthly at $9.99

Start Free Trial

Included in your trial

Unlimited access to the Learn & Grow App

Up to 4 child profiles

Offline activities and printables

Resources and tips from learning experts

LIMITED TIME BONUS OFFER

Learn with

Sesame Street FREE with HOMER Learn & Grow SubscriptionHOMER's four-step learning framework meets Sesame Workshop's tried and true approach: teaching kids to be confident, curious, and kind.

Learn more

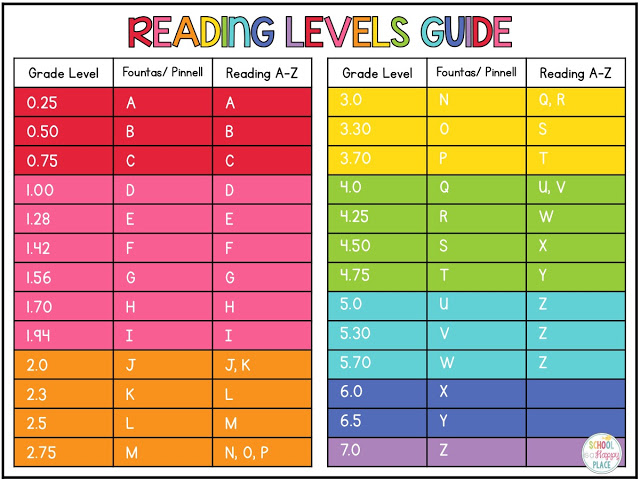

The Learning Journey That Grows with Your Child

Tap below to explore what they'll learn at each stage.

Toddler

Preschool

Pre-K

Early Learner

Growing Learner

Explore Ages

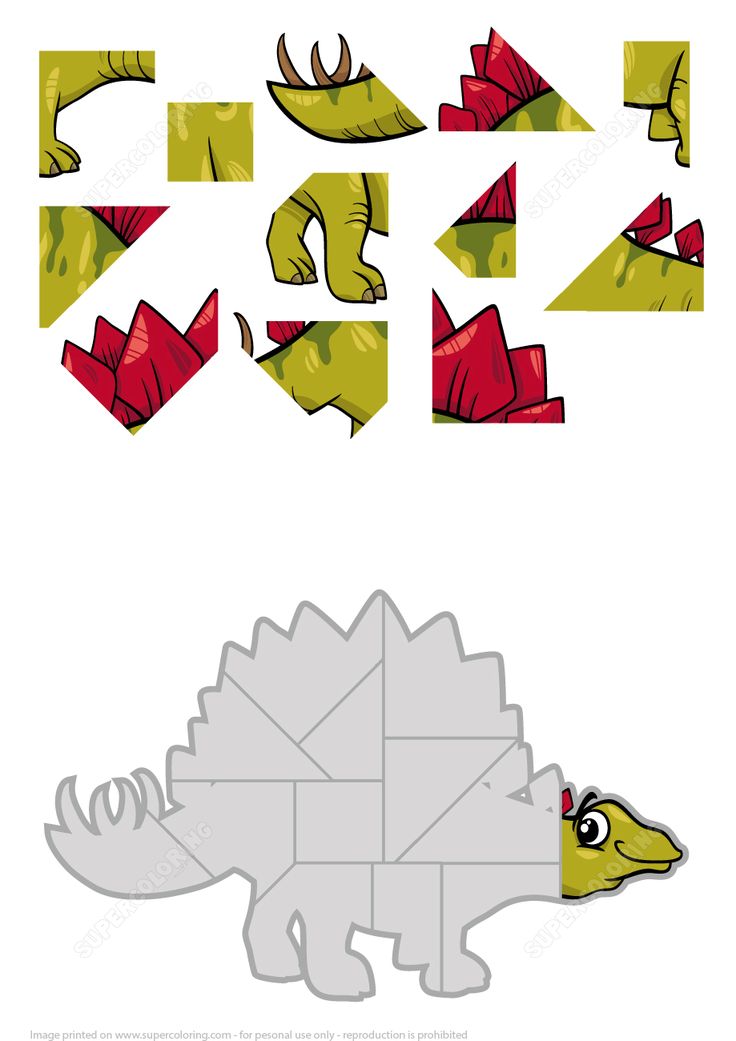

Personalized to Their Interests Across Subjects

Sports

Vehicles

Princesses

Dinosaurs

Animals

Kid Powered Learning

Personalized

Lessons, and activities personalized to age, interests, and skill level.

Proven

Research-backed, kid-tested, parent-approved.

“I Did It” Moments

Builds skills kids (and parents) are proud of.

Joyful

Fueled by activities kids actually want to play.

Safe & Easy

Ad-free, safe, and easy for kids to use.

The Buzz On HOMER

“HOMER is a parent’s dream! Kids are having fun, so they don’t know it’s learning. They ask to do more!”

Deb S.

“Both of my kids use HOMER’s learning program and have excelled! We’ve tried literally 20+ apps and websites, and NONE hold a candle to HOMER.”

Brittany

“My four-year-old daughter has sensory processing disorder; getting her to focus on learning can be a bit of a nightmare, but HOMER has her FULL attention.”

Katie M.

Personalization Made Easy

You tell us a little about your child, and we’ll come up with a learning journey made just for them!

We combine your child’s unique interests

with their age and current learning level

to create a personalized learning journey they love

that builds essential skills for school and life!

Get Started

The Most Effective Way for Your Child to Learn

Developed by experts, our research-based, four-step approach goes beyond rote memorization to build confidence, promote problem-solving, and foster a lifelong love of learning.

learn more

AS SEEN IN

Learn With Homer ~ Educational Website

alphabet Education Language Arts Learning Games Learning Websites Preschool Product Review

- Share

- Tweet

This post may contain affiliate links.

I love using high-quality educational technology for teaching my kids. There are so many great apps and websites available for learning now that really teach kids in creative ways. We have been trying out a new one the past few weeks called Learn With Homer. I have been using it with my 4-year-old preschooler. Learn With Homer is a website (or app) recommended for kids ages 3-7 that helps kids to learn to read. It was designed in a way that makes it easy to be done with little to no parent assistance. This gives kids the chance to work and learn on their own if they desire to. You can sign up either through the online platform or through an app on your tablet.

This is a sponsored post in behalf of Learn with Homer. I am being compensated for my tie in creating this post, but all thoughts are my own.

I am being compensated for my tie in creating this post, but all thoughts are my own.

They use The Homer Method to teach reading. The Homer Method is a 4-step method that teaches the letter sounds and symbols, then adds the letters into words, the words into ideas through stories then ideas into knowledge through thinking skills. In Learn With Homer they teach the synthetic phonics method meaning they teach the sounds then combine sounds into words. It was created by educator Stephanie Dua and uses the latest scientific knowledge of how children learn in their program.

Learn With Homer is a fun website that is set up like a small theme park called Pickle Wickle Park. There are different locations the kids can visit to explore and learn. There is their regular learning path that teaches reading skills, Adventures in History, Storytime, Discover the World, And Music. It includes more that 1000 different lessons! Each of these different locations has fun new things to do and learn. They teach songs, stories and poems from different seasons and styles and cultures around the world. They have fun history and science lessons teaching kids about animals, their body, presidents, and musicians. It is a great way to introduce new topics to young kids. Learn with Homer is updating their site this Fall with new navigation making it easier to discover all of the many things available on the website as well as adding a new interactive world!

They teach songs, stories and poems from different seasons and styles and cultures around the world. They have fun history and science lessons teaching kids about animals, their body, presidents, and musicians. It is a great way to introduce new topics to young kids. Learn with Homer is updating their site this Fall with new navigation making it easier to discover all of the many things available on the website as well as adding a new interactive world!

One thing I really loved about the site was how they brought in songs and stories from around the world. My son’s FAVORITE song of all on the website is a Swedish holiday song about gingerbread men called Tre Pepparkaksgubbar. It is all in Swedish. He plays it over and over! It was fun because we wanted to know more about what it meant so we spent some time investigating it online with him and my older kids. I love that it created some outside discovery and learning as well! We never would have learned about it otherwise.

My son has been having a blast learning on the website. We sit together and practice his reading a little each day as well as explore some of the other fun topics. He is always happy to have some special learning things that are just for him. I also see the skills he is learning from Learn With Homer. He is definitely benefiting from the reading sections.

You can try it our for free for 30 days. After that it is $7.95/month or $79.95 for a full year. HOWEVER, I have a discount code that will give you 50% off for one year of Learn With Homer!!

100 Best Learning Apps by Subject

Preschool Counting: How Many Drops to Fill the Dot?

Leave a Comment

how to learn to understand more and forget less - Knife

Slow (close) reading is a practice that opposes passive and thoughtless consumption of information. Unlike speed reading, which promises to teach us to read 100, 200, 300 books a year, or school reading, which distributes ready-made formulas and answers to all questions, slow reading involves deep, comprehensive immersion in the text and independent, responsible work with it.

The birth of this practice is often associated with the slow movement that appeared at the end of the 20th century. Its supporters seek to slow down the pace of life, which has greatly accelerated in recent times, in all its areas - from food and travel to fashion and science. However, the phenomenon of slow reading arose much earlier.

Around 200 AD, Judaism developed a method of oral commentary on the Torah, which was accompanied by meticulous reading of the sacred texts. Starting from the smallest details, phrases and phrases, the rabbis-interpreters tried to discover new, previously unnoticed and at the same time more accurate meanings in the words given by God. Subsequently, this occupation became a tradition and received the name Midrash ; the verb "darash", which is part of the root of this word, means "to demand, find out, inquire." Later, Neoplatonists began to interpret the texts in this way: philosophers like Proclus or Damascus wrote huge, sometimes thousands of pages, commentaries on individual dialogues of Plato. Their research became an example for philosophers, philologists and theologians for a long time.

Their research became an example for philosophers, philologists and theologians for a long time.

Friedrich Nietzsche was one of the first to notice the lack of thoughtful reading in an era of increased speed of life. In 1881, in his pivotal work Dawn, he wrote:

crazy, not sparing the forces of haste - an age that wants to do everything and cope with everything, with every old and every new book. Philology does not do everything so quickly - it teaches to read well, that is, slowly, peering into the depth of meaning, following the connection of thought, catching hints, seeing the whole idea of the book as if through an open door ... "

In the 20th century, the practice of slow reading gained a second wind, becoming an indispensable component of many literary criticism. For example, the formal school appeared in Russia , insisting that formal, stylistic elements are important in literature, which must be carefully analyzed. In France, Marcel Proust took a similar position: in his essay "Against Sainte-Beuve" he wrote that the text is primary, and not the personality of its author. Later, this idea was picked up and developed by his compatriot Roland Barthes in the essay "Death of the Author" (1967).

In France, Marcel Proust took a similar position: in his essay "Against Sainte-Beuve" he wrote that the text is primary, and not the personality of its author. Later, this idea was picked up and developed by his compatriot Roland Barthes in the essay "Death of the Author" (1967).

In England, Thomas Stearns Eliot spoke of the same thing.

In his opinion, a novel or a poem is an independent aesthetic object. Its meaning is revealed only in itself, in the interaction of its components, therefore it requires careful reading.

The same view was held in the United States by the so-called new critics, including Clint Brooks and Robert Penn Warren, who published Understanding Poetry in 1939 and Understanding Prose in 1943. The methods of close reading proposed in these works defined American education for decades to come.

One of the brightest American professors who taught slow reading to his students was Vladimir Nabokov. “Literature,” he said in his famous lectures, “real literature should not be swallowed in one gulp, like a drug useful for the heart or mind, this “stomach” of the soul.

Literature should be taken in small doses, crushed, crumbled, ground - then you will feel its sweet fragrance in the depths of your palms.

At the turn of the 20th-21st centuries, slow reading practices faded into the background in literary criticism. However, readers continue to gather in book clubs and organize reading groups, where they parse classic texts for different fields (and some even earn big money from this). However, such group reading gives a good result only if each participant carefully read and worked through the text, otherwise such meetings turn out to be superficial. And slow reading is an activity that deserves a responsible approach.

Why read slowly

In 1924, the brochure How to Read Books was published in the Soviet Union. Its author, pre-revolutionary professor of logic and philosophy Sergei Innokentyevich Povarnin, wrote about the dangers of quick, superficial reading as follows:

“The habit of ‘swallowing’ books can cause headaches.

It can contribute to the development of neuroses, neurasthenia and other diseases of the nervous system, and also be one of the causes of various bodily diseases derived from disruption of the normal functioning of the nervous system. Bad reading sometimes interferes with the normal development of abilities and often spoils them, for example, it weakens the ability to concentrate attention, memory, etc. It weakens the will and the ability to think.

Today, some of Povarnin's statements can be questioned, but one of them remains indisputable:

"Bad reading is harmful, first of all, because it deprives of the enormous benefit that good reading gives" .

What is this benefit?

First, slow reading is active activity . We are accustomed to treating fiction and philosophical literature as another source of information that is automatically recorded in our brain while we are reading. Therefore, it seems to us that the more books we swallow, the more information we use, the smarter we become - hence all these speed reading courses and lists of "50 main books". Unfortunately, it doesn't work that way.

Unfortunately, it doesn't work that way.

Fiction, like philosophical , has never been a source of ready-made knowledge. Both types of books require active reading, which excludes haste.

Slow reading develops critical thinking and the ability to think. Actively working with the book, the reader independently searches for additional information, checks sources, finds keywords, compares ideas, evaluates the author's judgments and thinks through his arguments. All this is a wonderful school of thought. The greatest European intellectual of the 20th century, Jacques Derrida, who was critical of the foundations of all European culture, admitted in one interview that he had read three or four books from his entire huge library. “But I read them very, very carefully,” he said.

Jacques Derrida shows his library

Secondly, serious and thoughtful work with a book sometimes leads to real insights. Slow reading makes us concentrate on a piece of text for a long time, perceive it as a problem that needs to be solved, and select keys to it. When our brain switches to passive mode after such intense activity, creative insights happen.

Slow reading makes us concentrate on a piece of text for a long time, perceive it as a problem that needs to be solved, and select keys to it. When our brain switches to passive mode after such intense activity, creative insights happen.

Looking at literature as a source of ready-made information also strengthens school education. Recall how often teachers demanded "knowledge of the text" and "content" from you, and in doing so, they usually meant the plot. But as early as the beginning of the 20th century, one of the predecessors of structuralism, Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp, in his work Morphology of a Fairy Tale, showed that, by and large, all stories consist of 31 varying functions, and even the most intricate of them are built according to the same schemes.

Does this mean that the plot doesn't matter? No, it's just not just about him. The authors waste paper and ink for a reason, choosing the right epithets and expressions and correcting the same paragraph a hundred times.

Tolstoy wrote about "Anna Karenina" in a letter to Nikolai Strakhov: "If I wanted to say in words everything that I had in mind to express in a novel, then I would have to write a novel - the very one that I wrote, first ".

A work of art fully reveals its meaning only when it is considered as an integral aesthetic object, consisting of a system of images, correspondences and interweaving. Each branch of lilac, a dissected frog, a grammatically incorrect phrase of the hero or his description play a role in the works of the great author. Skipping them or not attaching importance to them is the same as flipping through two paragraphs in a mathematics textbook. But in order for these details to play with colors and be filled with meanings, you need to use your imagination while reading. Do not be lazy to think about the state of mind of the hero, grab a wide oak tree with him or paint the missing colors on the wallpaper - all this will develop your emotional intelligence and empathy and give you the precious experience of thousands of unlived lives.

After all, art, as the Soviet literary critic Yuri Lotman said , “is the experience of what did not happen.”

Theory and practice of slow reading in literature, cinema and art from the Eshkolot project

Thirdly, slow reading of literary and philosophical texts changes our sensibility and forms a different view of the world. If Leo Tolstoy were read attentively in our schools, many of the students would become anarchists. Therefore, the literary critic Dmitry Petrovich Svyatopolk-Mirsky, in his work "On Conservatism" at the beginning of the 20th century, was surprised that the authorities, teaching Tolstoy's children, want to rely on him as one of the pillars of statehood.

Finally, deep and prolonged work with text trains memory and concentration. A book read in one sitting is forgotten in a week. If the book was read slowly, analyzed and asked questions, it will stick in the memory for a long time. This is because during the time we spend on reading with this approach, not just associative connections, but whole bunches and clusters manage to form in our head.

“In self-education,” Sergey Povarnin wrote in his brochure, “work on a book must be the most serious, persistent, difficult, and often very long. But there is nothing to regret about it: it will pay off in abundance. Even if you later forget the book, work on it will not be lost: it will remain in the form of useful skills, advanced development, accumulated skills and strength.

How to read slowly

General advice: before reading, turn off your mobile phone and other devices. Or don't turn it off, but put them on silent mode and put them away. The fact is that social media alerts stimulate the production of dopamine in our brain, and this prevents us from enjoying activities that require attention, including leisurely reading a well-written text.

Tip 1. Reread

At the beginning of the 19th century, the German philosopher and theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher introduced the term "hermeneutical circle" into scientific use.

At the first reading, we do not notice many details, because we are not yet fully familiar with the work. When we read the text again, we already have a general impression of it, and we begin to notice the details that the first time they didn’t tell us anything. As a result, our understanding of the meaning of the text becomes more voluminous and more accurate. Therefore, rereading is a necessary stage of slow reading, which, moreover, gives a separate pleasure.

In the preface to his lectures on European literature, Vladimir Nabokov said: “Let it seem strange, but you can’t read a book at all - you can only re-read it. A good reader, a select reader, co-participant and creative, is a re-reader.

Tip 2. Focus on a single passage

You can't slowly read a long piece - fortunately, this is not necessary. You need to practice your ability to read the text in small fragments.

The Soviet philologist Dmitry Sergeevich Likhachev recalled his studies at the university in the following way: “Academician Shcherba was the promoter of slow reading.

He and I managed to read only a few lines from The Bronze Horseman in a year. Each word seemed to us like an island that we had to discover and describe from all sides.

The same island, on which all attention is concentrated, should become a separate paragraph or line.

In a limited section of the text, the significance of each of its elements increases; words or punctuation marks take on additional weight .

That is why it sometimes seems to us that a short poem contains more meaning than some thick novel. The Russian formalist Yuri Nikolayevich Tynyanov associated this effect with the so-called tightness of the verse row - the close proximity to each other of words with an increased meaning, forcing us to move deeper.

Tip 3. Find key passages

The most "shocking" passages in any work are its title, beginning and end. If everything is obvious with the title, then with the beginning and end - not quite. Try to match the beginning and end of the book you are reading. For example, Gogol's "Inspector General" begins with the Governor telling his subordinates "unpleasant news" and one of them, Luka Lukich, exclaims: "Lord God!" - and ends with the Governor being "in the middle in the form of a pillar, with arms outstretched and his head thrown back." (Recall that Christ was crucified for the good news of the coming Kingdom of God.)

Try to match the beginning and end of the book you are reading. For example, Gogol's "Inspector General" begins with the Governor telling his subordinates "unpleasant news" and one of them, Luka Lukich, exclaims: "Lord God!" - and ends with the Governor being "in the middle in the form of a pillar, with arms outstretched and his head thrown back." (Recall that Christ was crucified for the good news of the coming Kingdom of God.)

In the story, one should also pay attention to the first and last appearance of the hero, to the description of his appearance, manners, clothes, room. Memories and dreams are no less significant - why did the author put them here? If a motive appears several times in a work, stop and think about what it can mean, remember where you met it for the first time. Some writers have marker words: Dostoevsky, for example, these are phrases like “I don’t know why he said that”, followed by key monologues of characters.

However, the most important passages in any work are those that are of personal interest to you. If you stumble upon something incomprehensible, do not rush, do not run forward - try to understand what exactly puzzled you and why.

If you stumble upon something incomprehensible, do not rush, do not run forward - try to understand what exactly puzzled you and why.

Your question to the text begins its real understanding.

Advice 4. Feel the style

Each author has his own voice: someone, like the aristocratic Turgenev, writes quietly and delicately, trying not to get into the soul of the characters, someone like Gogol, who loved to read his works to friends , adds ridiculous and sonorous words, someone, like Dostoevsky, hurriedly dictating a text to his stenographer wife, writes crookedly and unevenly. The way the author builds sentences, what metaphors he resorts to and for what purpose he uses them, reflects his view of the world. Chasing the plot, swallowing five books a week, means not seeing a person with an individual manner and temperament behind the printed letters.

It's bad when we don't hear the author's voice in a hurry, but it's even worse when we don't notice that there are more than one or two such voices in the book. “A novel,” wrote Russian culturologist of the 20th century Mikhail Bakhtin, “is a multi-style, contradictory, discordant phenomenon,” and not every recorded word necessarily belongs to the author.

“A novel,” wrote Russian culturologist of the 20th century Mikhail Bakhtin, “is a multi-style, contradictory, discordant phenomenon,” and not every recorded word necessarily belongs to the author.

Tip 5. Be suspicious

Everyone read Chekhov's story "The Man in the Case" at school. His hero, the Greek teacher Belikov, "was remarkable in that he always, even in good weather, went out in galoshes and with an umbrella, and certainly in a warm coat with wadding." We laughed at this man in unison, condemned him for his "disgust for the present", and praised Chekhov for bringing out such an absurd and pitiful type. But wait, did Chekhov tell us this story? Let's go back to the beginning.

“On the very edge of the village of Mironositsky, in the barn of Prokofy the belated hunters settled down for the night. There were only two of them: the veterinarian Ivan Ivanovich and the teacher of the gymnasium Burkin.

The story of the "case man" is told to us (or rather, to the veterinarian) by a provincial gymnasium teacher named Burkin. By all appearances, Burkin is a classic representative of the 19th century intelligentsia, who was carried away by the tendentious "democratic" literature that looked for "types" and denounced people for "inaction."

By all appearances, Burkin is a classic representative of the 19th century intelligentsia, who was carried away by the tendentious "democratic" literature that looked for "types" and denounced people for "inaction."

“Under the influence of people like Belikov,” says Burkin, “over the past ten or fifteen years, everything has become fearful in our city. They are afraid to speak loudly, to send letters, to make acquaintances, to read books, they are afraid to help the poor, to teach them to read and write…”

Who is Chekhov really laughing at here - the teacher of the Greek language (whom we know about only from the words of Burkin) or his colleague - a "thinking, decent" man of his time? And which of them is really "in the case"? It is good to ask such questions as often as possible. Are you sure that Humbert Humbert, the pedophile from Lolita, is completely frank with you? Do you remember who exactly told his literary friend Oblomov's whole life? But could not the narrator from "Poor Lisa" in the thirty years that have passed since the story described in the story, confuse or embellish something? How did Belkin in "The Station Agent" peep into the scene between Minsky, Dunya and Vyrin in the former's house? Does the author lead readers by the nose?

Tip 6.

Look in the dictionary

Look in the dictionary Train yourself to check the meanings of all unfamiliar words, especially adjectives: over time, they will significantly enrich your speech. Refer to the dictionary and when a word seems familiar to you, but you cannot give an exact definition. Do not be lazy to look at the origin of words that seem significant to you in the text. For this, you can use the Fasmer dictionary or other etymological dictionaries.

The ancient Greek language provides a particularly rich ground for reflection. In particular, Russian writers liked to resort to him. So, the surname "Stavrogin" was formed by Dostoevsky from the ancient Greek word σταυρός ("cross"). According to Tolstoy's original plan, Karenin was supposed to have the surname Stavrovich, but the writer changed his mind. His son Sergei Lvovich recalled this as follows: “Once he told me:“ Karenon - Homer has a head. From this word I got the surname Karenin.

Another easy way is to use a search engine.

In Dostoevsky's "Notes from the Underground" there is the following fragment: "I am told that the climate of St. Petersburg is becoming harmful to me and that with my insignificant means it is very expensive to live in St. Petersburg. I know all this, I know better than all these experienced and wise advisers and nods. But I remain in Petersburg; I will not leave Petersburg!”

Usually, under the word “nodder” there is a note with a reference to Dahl: “This word, obviously, was formed by Dostoevsky from the colloquial “nod”; this was the name of a person who nods his head, winks or gives secret signs to someone.

Does this interpretation clarify the meaning of the passage? Not really. However, on the net you can find out that the word “nodding” is a reference to the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, to those scenes in which Jesus was persuaded to come down from the cross: “And those who pass by blaspheme him, nodding their heads and saying: build up today: save yourself, and bring down from the cross” (Mark 15:29-30). It turns out that Dostoevsky's text refers the reader to the Bible: the "underground man" compares himself to Jesus Christ.

It turns out that Dostoevsky's text refers the reader to the Bible: the "underground man" compares himself to Jesus Christ.

Tip 7. Take notes, draw diagrams and plans

Notes in the margins of a book or in a separate notebook teach us not only a critical, active approach to the text, but also the ability to accurately and concisely formulate our thought. Intuitions and guesses that are not fixed on paper or electronic media will remain vague impressions and disappear into oblivion.

The habit of reading with a pencil, pen or marker in hand turns us for a moment into a creator, an equal participant in the dialogue with the author, a real reader.

Until then, we are ordinary listeners or guests.

The creation of plans and schemes can be of no less service. In his lectures on Anna Karenina, Vladimir Nabokov, with the help of graphs and comparisons, showed that the line of Anna and Vronsky chronologically forges ahead; reading Dickens or Proust, he drew plans of London or Paris in the margins. Lev Semenovich Vygotsky, having drawn the composition of Bunin's story "Light Breath", explained how art interacts with consciousness. Every reader can do this.

Lev Semenovich Vygotsky, having drawn the composition of Bunin's story "Light Breath", explained how art interacts with consciousness. Every reader can do this.

Let's take a scene from the eighth chapter of "Fathers and Sons", in which Pavel Petrovich examines the room of Fenechka, a girl who recently gave birth to a child from his brother Nikolai Petrovich:

"Chairs with backs in the form of lyres stood along the walls; they were bought by a dead general in Poland during a campaign; in one corner there was a bed under a muslin canopy, next to a wrought-iron chest with a round lid. In the opposite corner a lamp was burning in front of a large dark image of Nicholas the Wonderworker; a tiny porcelain testicle hung on a red ribbon on the saint's chest, attached to the radiance; on the windows, jars of last year's jam, carefully tied up, shone through with green light; on their paper covers, Fenechka herself wrote in large letters: “circle-maker” <...> In the wall, over a small chest of drawers, hung rather poor photographic portraits of Nikolai Petrovich in various positions, made by a visiting artist.

Just skimming the text with our eyes, we are unlikely to notice that something is missing in the description of the room. If you sketch out the plan of the room, it becomes clear that Pavel Petrovich does not mention Fenechka's bed, although there is definitely a place for her in the room. Could this bed be located in another room? No: the baby sleeps here. Can Pavel Petrovich be reproached for inattention? Hardly. Pavel Petrovich consciously does not look at the bed on which his brother recently conceived a child with Fenechka. With the same Fenechka, because of which Pavel Petrovich will soon shoot with Bazarov. Such a trick is called a transfer from one sign system to another - from verbal to graphic. And how much more information about the Kirsanov family can be taken from this fragment?

Tip 8. First read the text itself, and only then criticism

A good critical article is always the result of a slow, thoughtful reading of the text. It helps us expand our own understanding of the book. Journalistic criticism will evaluate its quality and reveal its relevance, philological criticism will show how the text is arranged and what influences its author has experienced, a scientific monograph will offer a new interpretation and explain its significance for culture. Especially valuable is the criticism of classical works, written "in hot pursuit", after the release of the book from the press: it is useful to see how differently contemporaries perceived the text, which seems to us canonical.

It helps us expand our own understanding of the book. Journalistic criticism will evaluate its quality and reveal its relevance, philological criticism will show how the text is arranged and what influences its author has experienced, a scientific monograph will offer a new interpretation and explain its significance for culture. Especially valuable is the criticism of classical works, written "in hot pursuit", after the release of the book from the press: it is useful to see how differently contemporaries perceived the text, which seems to us canonical.

However, the Russian philosopher of the 20th century Vladimir Bibikhin, in his courses on reading philosophy, warned students against being "captured" by someone else's concept. Any thought must first of all be allowed to be itself, without "placing" it in a certain era, direction or style. This also applies to fiction: before you get acquainted with criticism, read the work yourself.

More to read

Slow reading methods:

- David Meeks Slow Reading in a Hurried Age - more practical tips for slow reading;

- Boris Eikhenbaum "How Gogol's Overcoat" is made - about how to be attentive to the author's stylistic features;

- Vladimir Nabokov "On Good Readers and Good Writers" and his lectures on Russian and foreign literature - your impression of school classics may noticeably change;

- Yuri Lotman “The Structure of a Literary Text.

Analysis of the poetic text" - about the method of rigorous scientific analysis of the text;

Analysis of the poetic text" - about the method of rigorous scientific analysis of the text; - Sergey Povarnin "How to read books" - about the method of analytical reading;

- Harold Bloom "Western Canon" and Brodsky's list - about those books that should be read slowly.

Examples of slow poetry reading:

- Iosif Brodsky — an essay on Tsvetaeva, Rilka, Akhmatova, Pasternak, Mandelstam, Robert Frost and Wisten Hugh Auden;

- Thomas Stearns Eliot - articles and lectures "The Purpose of Poetry" and "Selected";

- Wystan Hugh Auden - collection of essays "Reading. Letter. About Literature";

- Olga Sedakova - essay.

Theoretical texts on slow reading:

- Marcel Proust Against Sainte-Beuve,

- Roland Barthes Death of an Author,

- Vladimir Bibikhin — course of lectures "Reading Philosophy".

A separate type of slow reading is the comments:

- Nabokov and Lotman to "Eugene Onegin",

- by the Russian philosopher Gustav Shpet to The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club by Charles Dickens,

- linguist Yuri Shcheglov to the novels of Ilf and Petrov,

- literary historian Alexander Dolinin to Vladimir Nabokov's novel "The Gift",

- a group of philologists led by Oleg Lekmanov to the "Egyptian stamp" by Osip Mandelstam,

- Soviet literary critic Alexander Anikst to Goethe's Faust, Hamlet and the rest of Shakespeare's plays,

- by the modern poet Vsevolod Zelchenko to the poem "Monkey" by Vladislav Khodasevich,

- by the philosopher Giorgio Agamben to the Epistle to the Romans,

- Proclus and Damascus to Plato's Parmenides,

- Jacques Derrida to the entire Western European philosophical tradition.

And the last piece of advice. Behind all the close attention to the text, behind all the practices of slow reading, it is important not to forget the words of the Georgian philosopher Merab Mamardashvili: “Literature is not a sacred cow, but only one of the spiritual tools of movement towards discovering oneself in the real test of life, unique, which only you experienced, and except for you and for you, no one will be able to extract the truth from this test.

How to learn to read 3 times faster in 20 minutes

October 6, 2020Education

Grab a book and check the effect for yourself right now.

Iya Zorina

Lifehacker author, athlete, CCM

Share

0Background: "Project PX"

Back in 1998, Princeton University hosted a seminar "Project PX" (Project PX), dedicated to high speed reading. This article is an excerpt from that seminar and personal experience of speeding up reading.

So, "Project PX" is a three-hour cognitive experiment that allows you to increase your reading speed by 386%. It was conducted on people who spoke five languages, and even dyslexics were trained to read up to 3,000 words of technical text per minute, 10 pages of text. Page in 6 seconds.

For comparison, the average reading speed in the US is between 200 and 300 words per minute. We have in connection with the peculiarities of the language - from 120 to 180. And you can easily increase your performance to 700-900 words per minute.

All that is needed is to understand the principles of human vision, what time is wasted in the process of reading and how to stop wasting it. When we analyze the mistakes and practice not making them, you will read several times faster and not mindlessly running your eyes, but perceiving and remembering all the information you read.

Preparation

For our experiment you will need:

- a book of at least 200 pages;

- pen or pencil;

- timer.

The book should lie in front of you without being closed (press the pages if it tends to close without support).

Find a book that you don't have to hold so that it doesn't closeYou will need at least 20 minutes for one exercise session. Make sure that no one distracts you during this time.

Helpful Tips

Before jumping straight into the exercises, here are a few quick tips to help you speed up your reading.

1. Make as few stops as possible when reading a line of text

When we read, the eyes move through the text not smoothly, but in jumps. Each such jump ends with fixing your attention on a part of the text or stopping your gaze at areas of about a quarter of a page, as if you are taking a picture of this part of the sheet.

Each eye stop on the text lasts ¼ to ½ second.

To feel this, close one eye and lightly press the eyelid with your fingertip, and with the other eye try to slowly glide over the line of text. Jumps become even more obvious if you slide not in letters, but simply in a straight horizontal line:

Jumps become even more obvious if you slide not in letters, but simply in a straight horizontal line:

How do you feel?

2. Try to go back as little as possible through the text

A person who reads at an average pace quite often goes back to reread a missed moment. This can happen consciously or unconsciously. In the latter case, the subconscious itself returns its eyes to the place in the text where concentration was lost.

On average, conscious and unconscious returns take up to 30% of the time.

3. Improve concentration to increase coverage of words read in one stop

People with average reading speed use central focus, not horizontal peripheral vision. Due to this, they perceive half as many words in one jump of vision.

4. Practice Skills Separately

The exercises are different and you don't have to try to combine them into one. For example, if you are practicing reading speed, don't worry about text comprehension. You will progress through three stages in sequence: learning technique, applying technique to increase speed, and reading comprehension.

You will progress through three stages in sequence: learning technique, applying technique to increase speed, and reading comprehension.

Rule of thumb: Practice your technique at three times your desired reading speed. For example, if your current reading speed is somewhere around 150 words per minute, and you want to read 300, you need to practice reading 900 words per minute.

Exercises

1. Determination of the initial reading speed

Now you have to count the number of words and lines in the book that you have chosen for training. We will calculate the approximate number of words, since calculating the exact value will be too dreary and time consuming.

First, we count how many words fit in five lines of text, divide this number by five and round it up. I counted 40 words in five lines: 40 : 5 = 8 - an average of eight words per line.

Next, we count the number of lines on five pages of the book and divide the resulting number by five. I got 194 lines, I rounded up to 39 lines per page: 195 : 5 = 39.

I got 194 lines, I rounded up to 39 lines per page: 195 : 5 = 39.

And the last thing: we count how many words fit on the page. To do this, we multiply the average number of lines by the average number of words per line: 39× 8 = 312.

Now is the time to find out your reading speed. We set a timer for 1 minute and read the text, calmly and slowly, as you usually do.

How much did it turn out? I have a little more than a page - 328 words.

2. Landmark and speed

As I wrote above, going back through the text and stopping the gaze take a lot of time. But you can easily cut them down with a focus tracking tool. A pen, pencil or even your finger will serve as such a tool.

Technique (2 minutes)

Practice using a pen or pencil to maintain focus. Move the pencil smoothly under the line you are currently reading and concentrate on where the tip of the pencil is now.

Lead with the tip of the pencil along the lines Set the pace with the tip of the pencil and follow it with your eyes, keeping up with stops and returns through the text. And don't worry about understanding, it's a speed exercise.

And don't worry about understanding, it's a speed exercise.

Try to go through each line in 1 second and increase the speed with each page.

Do not stay on one line for more than 1 second under any circumstances, even if you do not understand what the text is about.

With this technique, I was able to read 936 words in 2 minutes, so 460 words per minute. Interestingly, when you follow with a pen or pencil, it seems that your vision is ahead of the pencil and you read faster. And when you try to remove it, immediately your vision seems to spread out over the page, as if the focus was released and it began to float all over the sheet.

Speed (3 minutes)

Repeat the tracker technique, but allow no more than half a second to read each line (read two lines of text in the time it takes to say "twenty-two").

You probably won't understand anything you read, but that doesn't matter. Now you are training your perceptual reflexes, and these exercises help you adapt to the system. Do not slow down for 3 minutes. Concentrate on the tip of your pen and the technique for increasing speed.

Do not slow down for 3 minutes. Concentrate on the tip of your pen and the technique for increasing speed.

In the 3 minutes of this frenetic race, I read five pages and 14 lines, averaging 586 words per minute. The hardest part of this exercise is not to slow down the speed of the pencil. It's a real block: you've been reading all your life to understand what you're reading, and it's not easy to let go of that.

Thoughts cling to the lines in an effort to return to understand what it is about, and the pencil also begins to slow down. It is also difficult to maintain concentration on such useless reading, the brain gives up, and thoughts fly away to hell, which is also reflected in the speed of the pencil.

3. Expanding the area of perception

When you concentrate your eyes on the center of the monitor, you still see its outer areas. So it is with the text: you concentrate on one word, and you see several words surrounding it.

Now, the more words you learn to see in this way with your peripheral vision, the faster you can read. The expanded area of perception allows you to increase the speed of reading by 300%.

The expanded area of perception allows you to increase the speed of reading by 300%.

Beginners with a normal reading speed spend their peripheral vision on the fields, that is, they run their eyes through the letters of absolutely all the words of the text, from the first to the last. At the same time, peripheral vision is spent on empty fields, and a person loses from 25 to 50% of the time.

A boosted reader will not "read the fields". He will run his eyes over only a few words from the sentence, and see the rest with peripheral vision. In the illustration below, you see an approximate picture of the concentration of vision of an experienced reader: words in the center are read, and foggy ones are marked by peripheral vision.

Focus on central wordsHere is an example. Read this sentence:

The students once enjoyed reading for four hours straight.

If you start reading with the word "students" and end with "reading," you save time reading as many as five words out of eight! And this reduces the time for reading this sentence by more than half.

Technique (1 minute)

Use a pencil to read as fast as possible: start with the first word of the line and end with the last. That is, no expansion of the area of perception yet - just repeat exercise No. 1, but spend no more than 1 second on each line. Under no circumstances should one line take more than 1 second.

Technique (1 minute)

Continue to pace the reading with a pen or pencil, but start reading from the second word of the line and end the line two words before the end.

Speed (3 minutes)

Start reading at the third word of the line and finish three words before the end while moving your pencil at the speed of one line per half second (two lines in the time it takes to say "twenty-two" ).

If you don't understand anything you read, that's okay. Now you are training your reflexes of perception, and you should not worry about understanding. Concentrate on the exercise with all your might and don't let your mind drift away from an uninteresting activity.