How many letter sounds should a kindergartener know

How Many Letters and Letter Sounds Should Young Children Know, And By When?

No More Teaching A Letter A Week is the latest offering in the Not This But That series, edited by Ellin Keene and Nell Duke. In this new book, early literacy researcher Dr. William Teale argues that alphabet knowledge is more than letter recognition, and he identifies research-based principles of effective alphabet instruction. Literacy coach Rebecca McKay brings those principles to life through purposeful practices that invite children to create an identity through print.

In today's post adapted from the book, William Teale introduces how children learn the alphabet, and how phonics standards differ across the country.

by William Teale

This question becomes important in light of the differing standards for alphabet knowledge that can be found for preschoolers:

- Alaska, Alabama, Arizona, South Dakota—at least 10 letters

- Indiana—13 uppercase letters

- The Head Start Outcomes Framework—“Identifies at least 10 letters of the alphabet, especially those in their own name”

- Early Reading First Performance Targets—16 to 19 letters.

You get the picture—standards for alphabet knowledge vary considerably. What does research say about what standards should be? There is as yet no comprehensive answer to this question, in part because the question itself is multifaceted: Is it how many to be considered not at risk? To be successful in reading at third grade? At first grade? And so forth… It is also the case that few studies have addressed this question directly. The best indicator we have to date comes from research conducted by Piasta, Petscher, and Justice (2012). They investigated the diagnostic efficiency of various upper- and lowercase letter-naming standards for 371 preschoolers, and one particular question in the study attempted to identify “optimal benchmarks.” Findings indicated that an end-of-preschool/beginning of kindergarten benchmark of ten letters was adequate to determine negative predictive power (the vast majority of children reaching this benchmark would not be at risk for low literacy achievement in grade 1), but also that optimal benchmarks were eighteen uppercase letters and fifteen lowercase letters when considering the three later grade literacy outcomes of letter–word identification, spelling, and passage comprehension. Thus, Piasta, Petscher, and Justice (2012) advocate setting higher end-of-preschool benchmarks than those typically appearing in state early learning standards or Head Start standards.

Thus, Piasta, Petscher, and Justice (2012) advocate setting higher end-of-preschool benchmarks than those typically appearing in state early learning standards or Head Start standards.

Overall conclusions based on research about how young children learn the alphabet are outlined in the figure below.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

William Teale is Professor, University Scholar, and Director of the Center for Literacy at the University of Illinois at Chicago. His work was central to bringing forth the concept of emergent literacy, and he has published widely in the field for the past 35 years.

Former Teacher of the Year in Alabama, Rebecca McKay is a literacy coach, a Teacher Consultant for the National Writing Project, a former trainer of trainers for the Alabama Reading Initiative, and a national presenter on a variety of literacy topics.

Topics: Early Childhood Education, No More Teaching A Letter A Week, Not This But That, Phonics Word Study, William Teale, Comprehension, Language Arts, Rebecca McKay, Spelling

Popular Posts

Tweets by Heinemann Publishing

The Alphabetic Principle | Reading Rockets

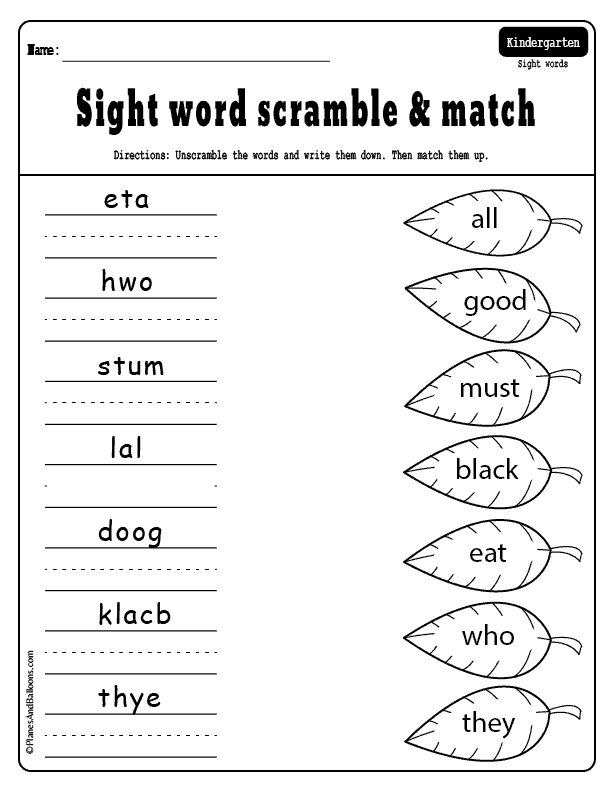

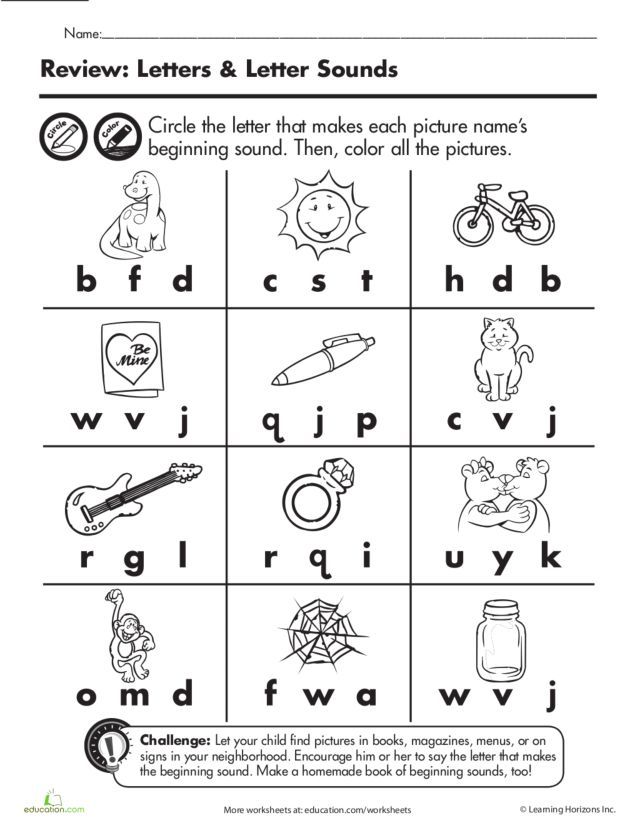

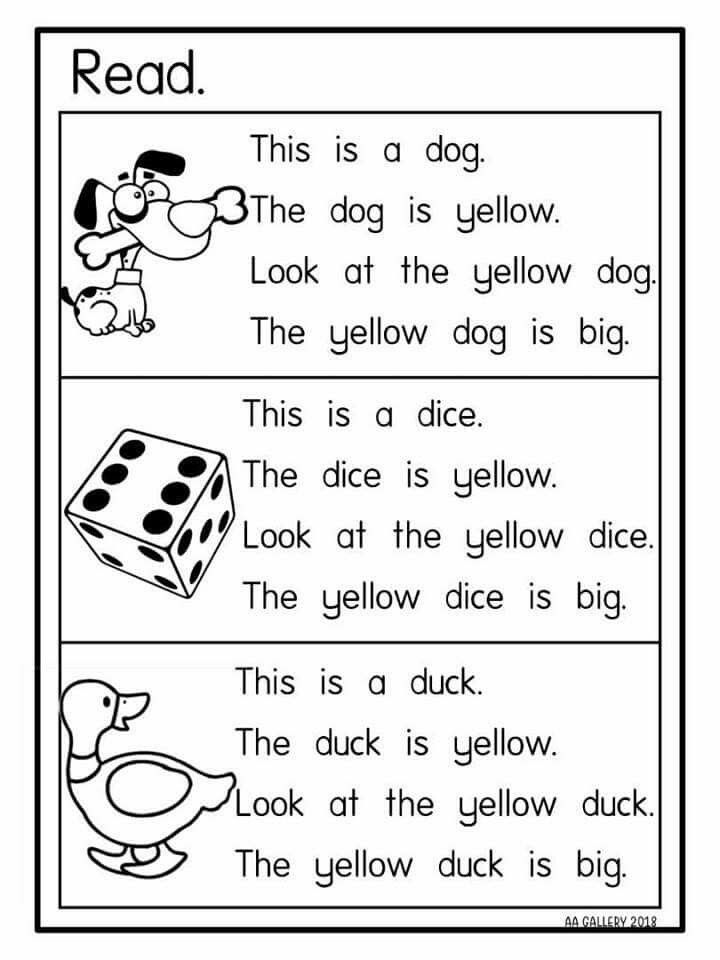

Not knowing letter names is related to children's difficulty in learning letter sounds and in recognizing words. Children cannot understand and apply the alphabetic principle (understanding that there are systematic and predictable relationships between written letters and spoken sounds) until they can recognize and name a number of letters.

Children cannot understand and apply the alphabetic principle (understanding that there are systematic and predictable relationships between written letters and spoken sounds) until they can recognize and name a number of letters.

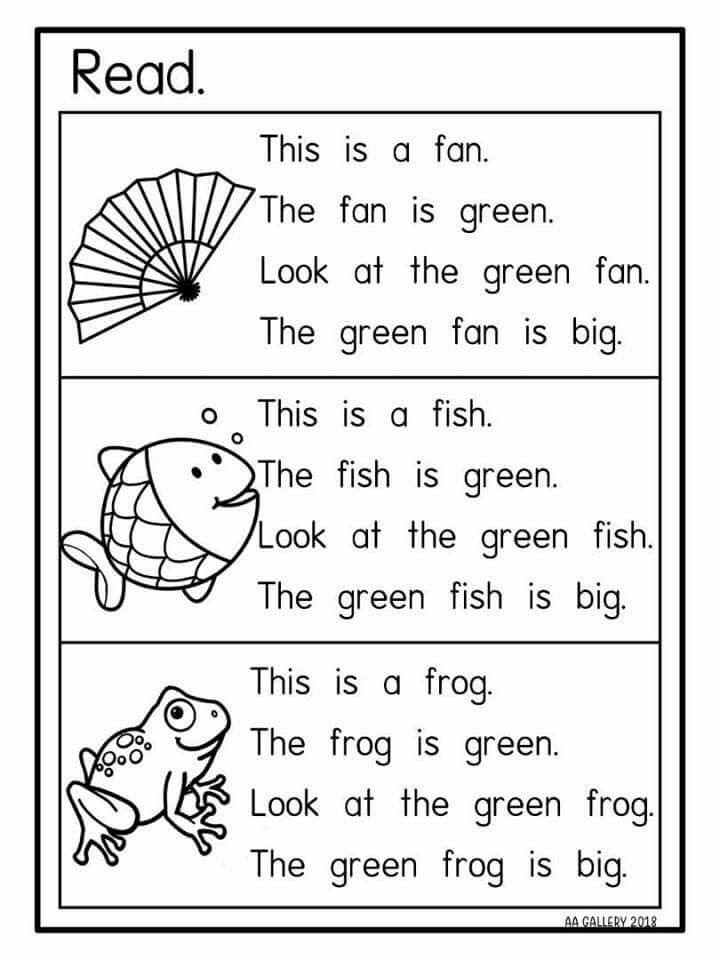

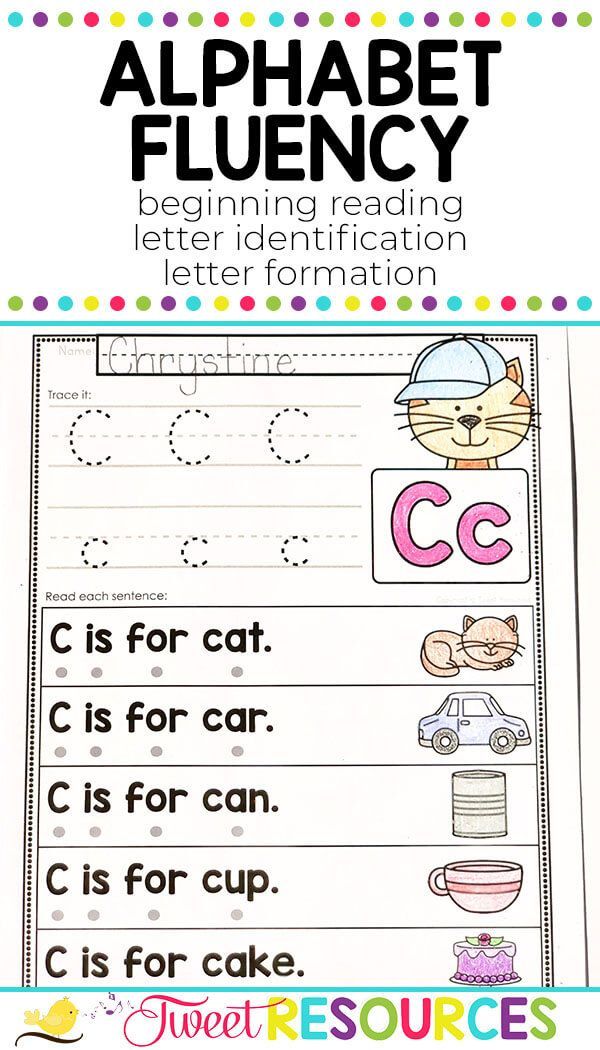

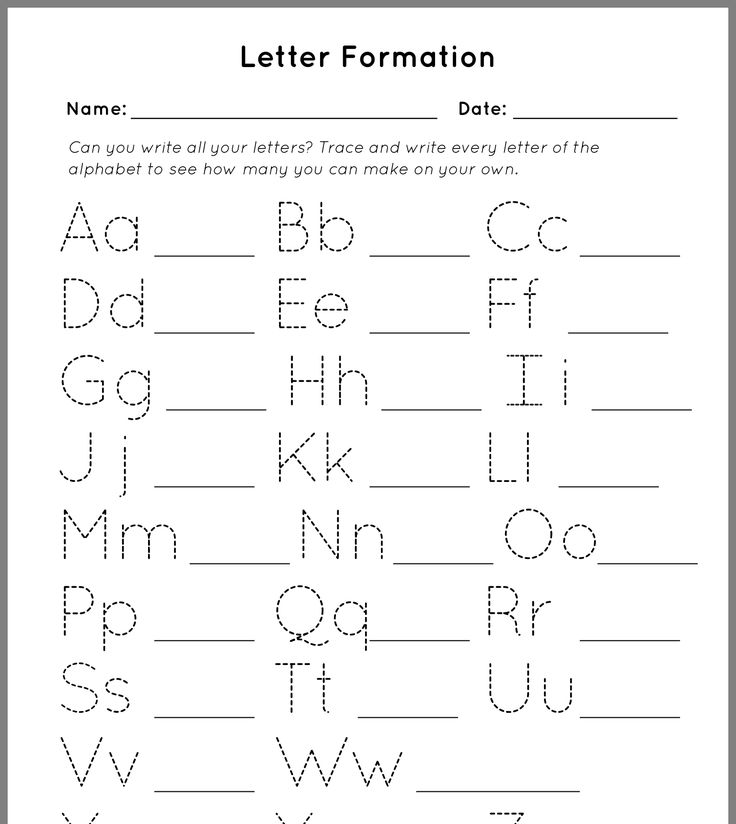

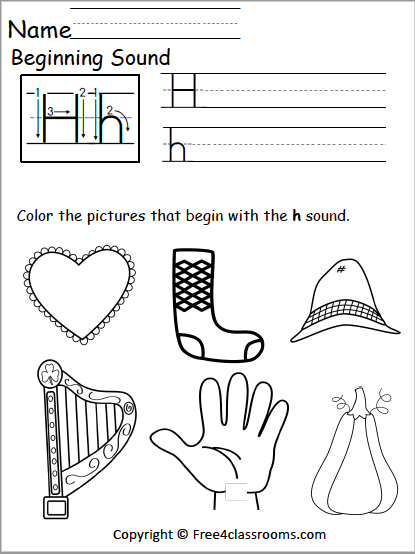

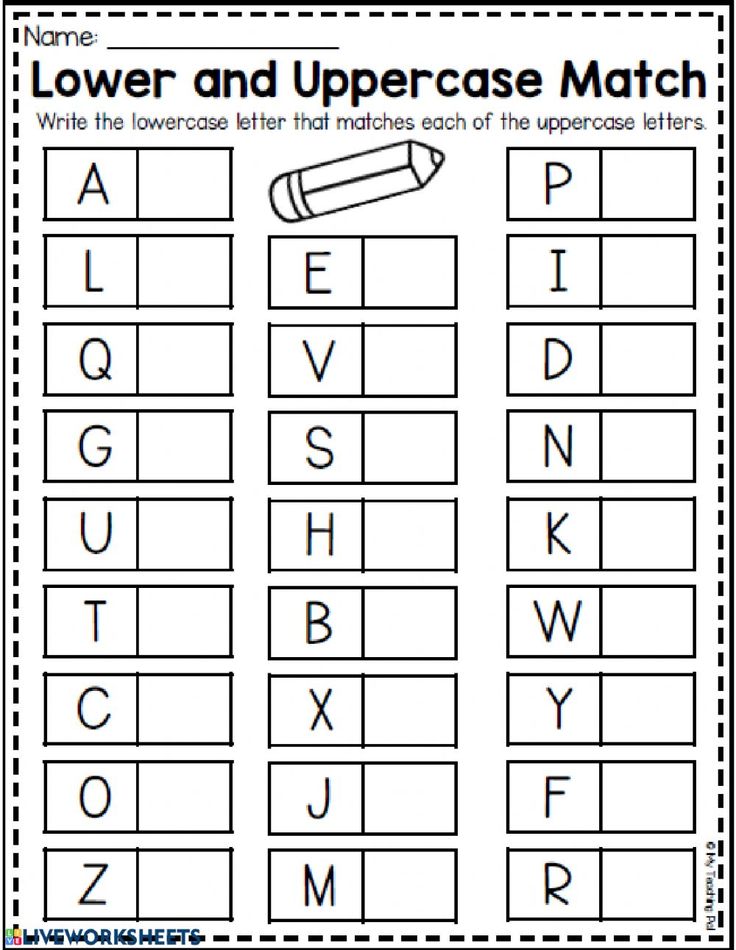

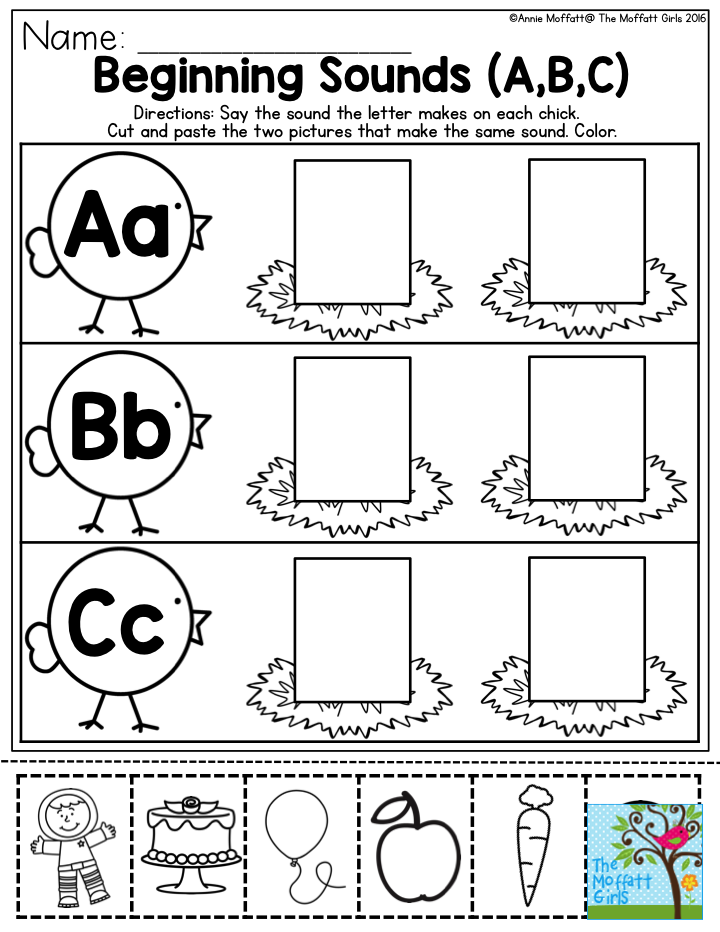

Children whose alphabetic knowledge is not well developed when they start school need sensibly organized instruction that will help them identify, name, and write letters. Once children are able to identify and name letters with ease, they can begin to learn letter sounds and spellings.

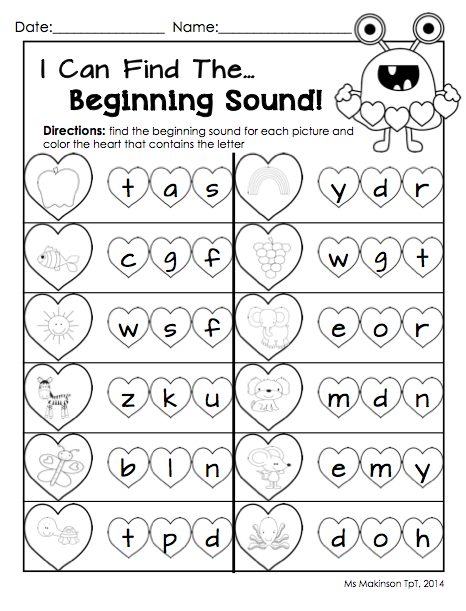

Children appear to acquire alphabetic knowledge in a sequence that begins with letter names, then letter shapes, and finally letter sounds. Children learn letter names by singing songs such as the "Alphabet Song," and by reciting rhymes. They learn letter shapes as they play with blocks, plastic letters, and alphabetic books. Informal but planned instruction in which children have many opportunities to see, play with, and compare letters leads to efficient letter learning. This instruction should include activities in which children learn to identify, name, and write both upper case and lower case versions of each letter.

This instruction should include activities in which children learn to identify, name, and write both upper case and lower case versions of each letter.

What is the "alphabetic principle"?

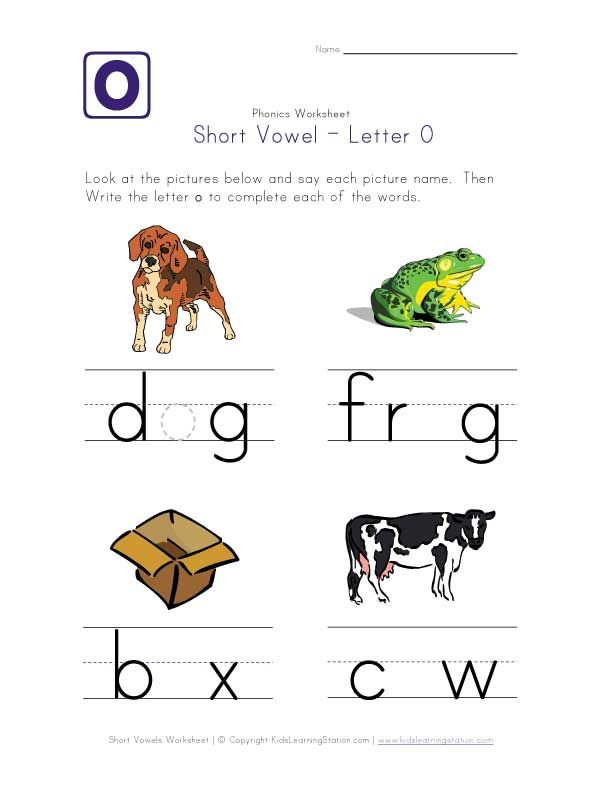

Children's reading development is dependent on their understanding of the alphabetic principle – the idea that letters and letter patterns represent the sounds of spoken language. Learning that there are predictable relationships between sounds and letters allows children to apply these relationships to both familiar and unfamiliar words, and to begin to read with fluency.

The goal of phonics instruction is to help children to learn and be able to use the Alphabetic Principle. The alphabetic principle is the understanding that there are systematic and predictable relationships between written letters and spoken sounds. Phonics instruction helps children learn the relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language.

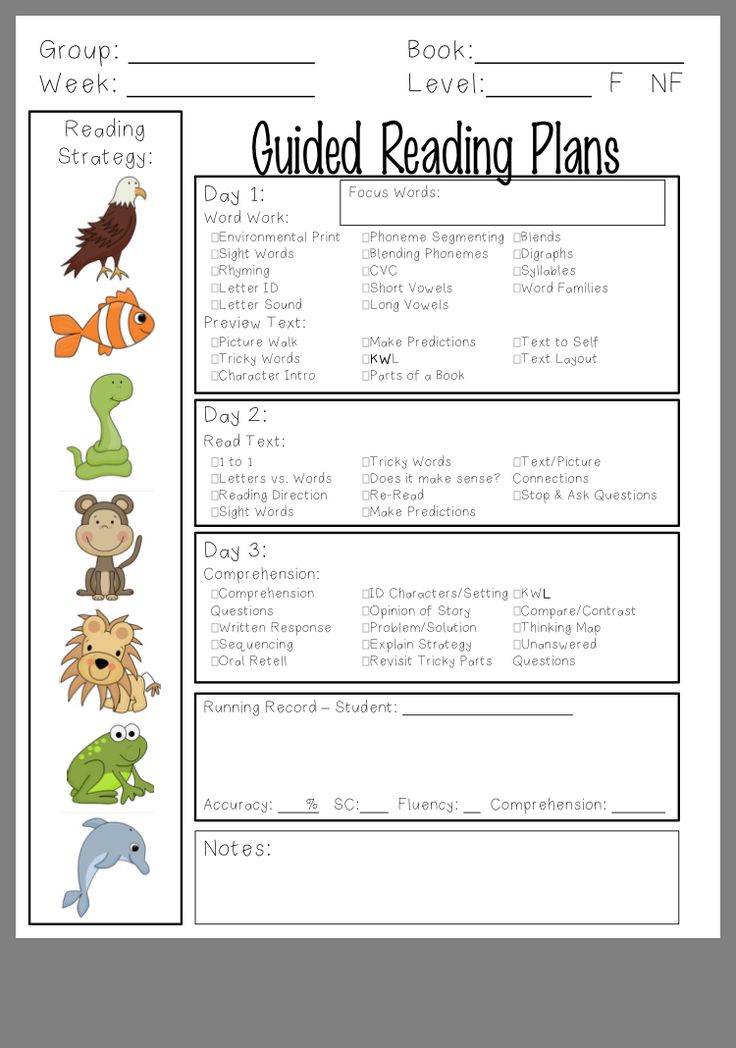

Two issues of importance in instruction in the alphabetic principle are the plan of instruction and the rate of instruction.

The alphabetic principle plan of instruction

- Teach letter-sound relationships explicitly and in isolation.

- Provide opportunities for children to practice letter-sound relationships in daily lessons.

- Provide practice opportunities that include new sound-letter relationships, as well as cumulatively reviewing previously taught relationships.

- Give children opportunities early and often to apply their expanding knowledge of sound-letter relationships to the reading of phonetically spelled words that are familiar in meaning.

Rate and sequence of instruction

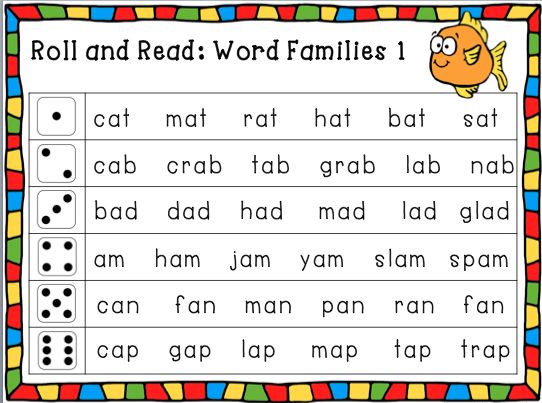

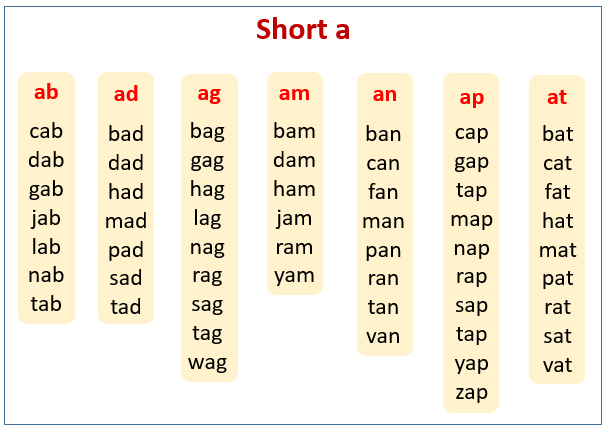

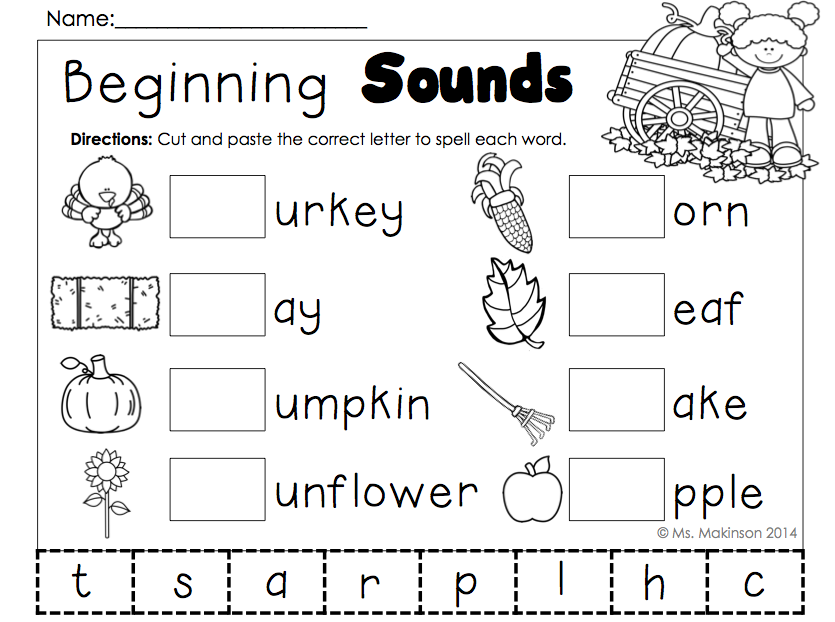

No set rule governs how fast or how slow to introduce letter-sound relationships. One obvious and important factor to consider in determining the rate of introduction is the performance of the group of students with whom the instruction is to be used. Furthermore, there is no agreed upon order in which to introduce the letter-sound relationships. It is generally agreed, however, that the earliest relationships introduced should be those that enable children to begin reading words as soon as possible. That is, the relationships chosen should have high utility. For example, the spellings m, a, t, s, p, and h are high utility, but the spellings x as in box, gh, as in through, ey as in they, and a as in want are of lower utility.

That is, the relationships chosen should have high utility. For example, the spellings m, a, t, s, p, and h are high utility, but the spellings x as in box, gh, as in through, ey as in they, and a as in want are of lower utility.

It is also a good idea to begin instruction in sound-letter relationships by choosing consonants such as f, m, n, r, and s, whose sounds can be pronounced in isolation with the least distortion. Stop sounds at the beginning or middle of words are harder for children to blend than are continuous sounds.

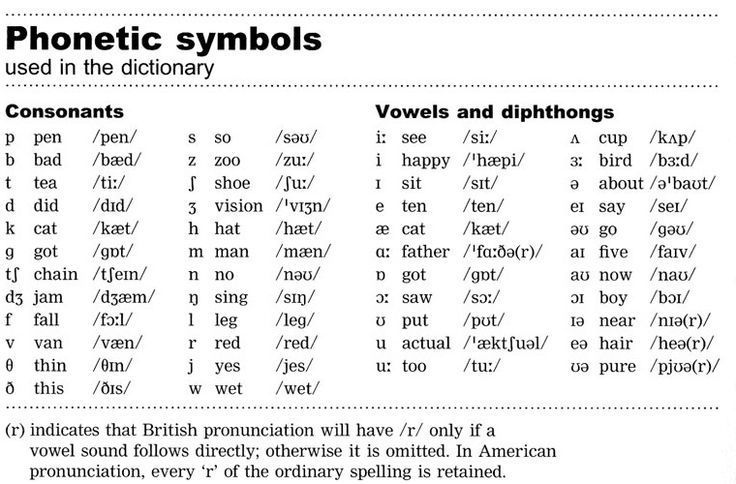

Instruction should also separate the introduction of sounds for letters that are auditorily confusing, such as /b/ and /v/ or /i/ and /e/, or visually confusing, such as b and d or p and g.

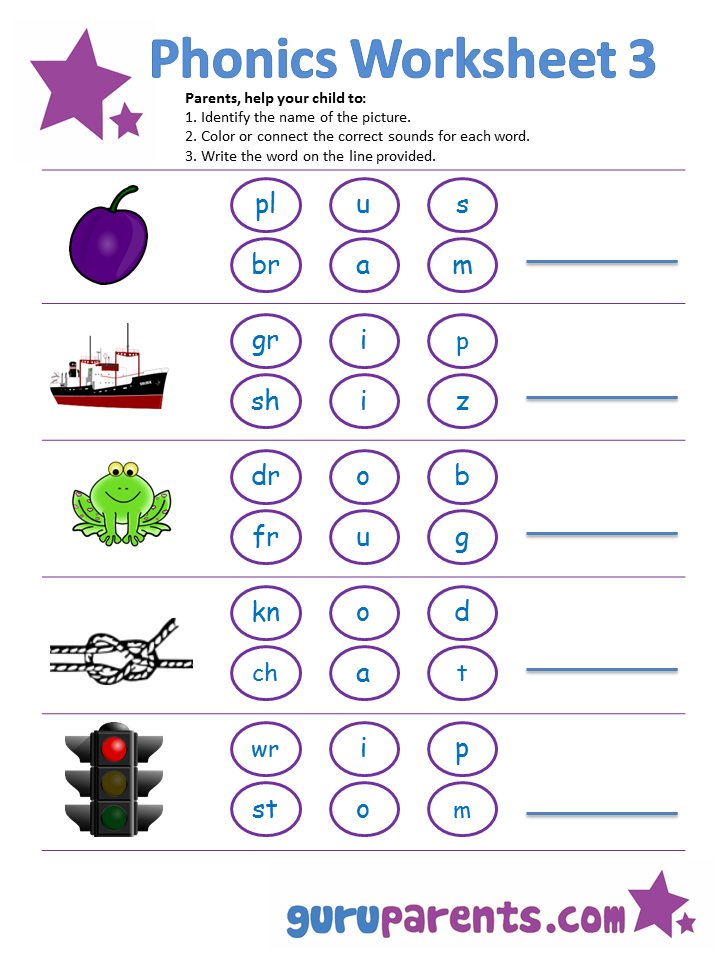

Instruction might start by introducing two or more single consonants and one or two short vowel sounds. It can then add more single consonants and more short vowel sounds, with perhaps one long vowel sound. It might next add consonant blends, followed by digraphs (for example, th, sh, ch), which permits children to read common words such as this, she, and chair. Introducing single consonants and consonant blends or clusters should be introduced in separate lessons to avoid confusion.

Introducing single consonants and consonant blends or clusters should be introduced in separate lessons to avoid confusion.

The point is that the order of introduction should be logical and consistent with the rate at which children can learn. Furthermore, the sound-letter relationships chosen for early introduction should permit children to work with words as soon as possible.

Many teachers use a combination of instructional methods rather than just one. Research suggests that explicit, teacher-directed instruction is more effective in teaching the alphabetic principle than is less-explicit and less-direct instruction.

Guidelines for rate and sequence of instruction

- Recognize that children learn sound-letter relationships at different rates.

- Introduce sound-letter relationships at a reasonable pace, in a range from two to four letter-sound relationships a week.

- Teach high-utility letter-sound relationships early.

- Introduce consonants and vowels in a sequence that permits the children to read words quickly.

- Avoid the simultaneous introduction of auditorily or visually similar sounds and letters.

- Introduce single consonant sounds and consonant blends/clusters in separate lessons.

- Provide blending instruction with words that contain the letter-sound relationships that children have learned.

For future first-graders

In Russia, children from 6.5 to 8 years old are admitted to the first grade. Some parents consider their children to be child prodigies who already have integrals on their shoulders, others think that in front of them are kids who have not yet run into. There is also a real fear - if the child stays at home, the first grade program will seem boring to him. But how do you know if it's time for the kids to go to school or not?

Studying for a first-grader is a physical load, and a lot of it.

Yes, a good teacher will do physical education lessons at the lessons, change the rhythm of learning, but all the same, the student will have to sit for 4-5 hours at the desk. How to determine whether a child is ready for school loads of the first grade, said Ekaterina Plyshevskaya, candidate of biological sciences, teacher of the psychological and physiological laboratory of the Vladimir Pedagogical Institute, which tests future first-graders, director of school No. 29 in the city of Vladimir.

How to determine whether a child is ready for school loads of the first grade, said Ekaterina Plyshevskaya, candidate of biological sciences, teacher of the psychological and physiological laboratory of the Vladimir Pedagogical Institute, which tests future first-graders, director of school No. 29 in the city of Vladimir.

So, the future student should be able to:

1. Show teeth

The number of permanent teeth is a sign of the physiological maturity of the child at this age. By the age of 7, there should be 6-8 permanent teeth, incisors should change and usually two molars. This is a sign that the child's bones are sufficiently formed so that he can sit without harm to his posture for 40 minutes during the lesson.

2. Reach out the left ear with the right hand

This is a "Philippine test" - a child, stretching his hand from above over his head, should cover half of his ear with a straightened palm, or better, cover his ear with his hand completely, without tilting his head.

This test, together with the previous one, shows the biological age of the child. Maybe, according to the documents, he is already 7 years old, and mentally he is age-appropriate and even ahead, but biologically he lags behind. Physically, the child is only six, he has not yet matured.

And school loads, especially with a program of increased complexity, can harm his health - he will start to get sick, psychophysiological disorders will begin. In these cases, it may be better to wait a year or choose a school with a simpler program.

3. Stand on one leg

Test "Romberg Pose": you need to stand on one leg, bend the other, press the foot to the knee, stretch your arms forward and close your eyes. By the age of 7, a child can stand like this for 8–10 seconds, if less, this is a sign of the physiological immaturity of the skeleton, unreadiness for school.

4. Draw “paths” without overstepping the edges

Fine motor test. You need to choose pictures where “waves” are drawn with two closely spaced lines, and ask the child to draw a third between them. If the line is drawn in the center, does not touch the other two - this is a sign that the hand is ready to learn to write.

You need to choose pictures where “waves” are drawn with two closely spaced lines, and ask the child to draw a third between them. If the line is drawn in the center, does not touch the other two - this is a sign that the hand is ready to learn to write.

Any child draws from the age of two, holding a pencil in his hand. But the peculiarity of the letter is smaller elements than in the drawing. If the child is not given such winding lines, then the hand is not ready for writing, and problems will arise: the child will not be able to display the elements of letters for the entire lesson, will quickly get tired, distracted, and eventually hate writing.

5. Count backwards

Modern children almost from two years old can count up to 10, from four - up to a hundred, up to a thousand. But this is a mechanical action, the child does not yet understand the number series. But the basics of logical thinking shows the ability to count backwards: from 10 to 1.

If a child can freely navigate the number series at least within ten, that is, count backwards, then he is ready to study mathematics. And a more difficult level is if a child can count through one without preparation: 10–8–6–4. This allows us to hope that the child will master the program of increased complexity without any problems.

6. Dress yourself

It is not necessary to tie the notorious shoelaces - just buy all Velcro shoes for your child, make life easier for everyone. But the child should be able to take off and put on his pants entirely, and not freeze in one leg, thinking about life. Should be able to put on a jacket and wrap a scarf - let it be crooked, the teacher will correct. But the procedure of dressing and undressing "from and to" must be mastered.

7. Available with plug

Yes, many children by the age of 7 can only use a spoon. I had the first class, where out of 30 children 10 did not know how to eat with a fork. And mothers, knowing that they were right, reported: “I feed him at home.”

And mothers, knowing that they were right, reported: “I feed him at home.”

At home, you can communicate with your child however you want, but at school, he must be able to pick up a plate and hold a spoon and fork. The break is short, and if the child does not know how to eat himself, he will remain hungry.

8. Follow the teacher's instructions

School is a society. By the first grade, a child should be able to understand the instructions of an adult, not a family member.

“We got the textbooks. They took pens, ”as my experience shows, many children do not understand even such simple instructions. Those who went to kindergarten have fewer problems, but "home" children often simply do not hear strangers.

It is necessary to prepare children from the age of five to follow simple instructions. Yes, there are problems with kindergarteners, parents can inspire the child what is right - only what they say, and you don’t need to listen to the rest.

But even here it is important not to overdo it: a child should not perceive any adult as the ultimate truth. Children need to understand boundaries. When the teacher says: “We took pens and write,” this must be done. When a stranger comes up on the street and says, “Come with me,” no way! A child of 5–6 years old is already able to learn such boundaries.

What to do if he is not yet ready?

To determine if a child is ready for school, look only at him. Not the neighbors, not the teachers. When a mother comes to me for a consultation and complains that a child at the age of 6 does not read, but “a neighbor says that she has been reading in two languages since the age of four”, I always answer: “Well, you say so too.”

With regard to physical development, one must look at the combination of signs. If, by the age of 6.5, milk teeth have just begun to fall out, in the “Philippine test” the child does not reach the ear, the “Romberg position” does not work out - it means that the child simply has not yet physically matured. He will not be able to sit through 40 minutes of the lesson, he will quickly get tired, skip explanations, and there will be problems with mastering the material. Then you just need to let the child "ripen", to postpone admission to school for a year.

He will not be able to sit through 40 minutes of the lesson, he will quickly get tired, skip explanations, and there will be problems with mastering the material. Then you just need to let the child "ripen", to postpone admission to school for a year.

If only one sign does not correspond to the school norm - for example, the teeth have not begun to change, now this is a frequent case, but you see that the child can complete tasks for a long time and with concentration, and does not take off every 10 minutes - it's time to go to school. And the teeth will grow in due time.

If a child is not psychologically ready: he is afraid to be alone, he cannot dress himself, he does not remember where he put his thing a minute ago, and his age allows him to postpone going to school for a year, it is better to do this. You won't believe how quickly children change at this age, there is a whole era between 6 and 7 years old. Schooling is always easier for seven-year-olds than for six-year-olds, unless we are talking about a child prodigy.

If it's already seven and a half, and the problems have not disappeared, choose a school with a sparing program. Closer to home, with low class sizes. Do not pursue programs of increased complexity: if the child later shows the ability and interest in serious subjects, transfer to another school.

There is nothing in the elementary school program that cannot be made up for in a couple of months. The main thing is not to discourage the child's desire to learn.

Source: https://vogazeta.ru/articles/2020/8/4/children/14171-8_veschey_kotorye_dolzhen_umet_buduschiy_pervoklassnik

Phonetic analysis of the word. What it is? How to do it? Examples

Let's learn how to phonetically analyze the most difficult words

Start learning

166.6K

the same letter. And there are a great many such examples in the Russian language. To understand why this happens, they came up with a phonetic parsing of words. Now we will tell you what it is and show with examples how it is customary to parse words into syllables, sounds and letters.

To understand why this happens, they came up with a phonetic parsing of words. Now we will tell you what it is and show with examples how it is customary to parse words into syllables, sounds and letters.

What is phonetic analysis

Phonetic , or sound-letter, word analysis is an analysis of the sounds and letters that make up this word.

There are 33 letters in the Russian language, from which we compose words and write them down on paper. When we pronounce a word, we hear sounds - this is how the letters in its composition sound. In some words, the same letter can mean two sounds at the same time or not sound at all. This is where sound-letter analysis comes in handy: it is needed so that we can analyze sounds and letters, write correctly, and also pronounce words.

Five in Russian in your pocket!

All the rules of the Russian language at hand

How phonetic parsing of a word is done

Sound-alphabetic parsing is usually done according to the following algorithm:

-

Number of syllables, stress.

-

Full transcription of the word.

-

Vowel sounds: stressed or unstressed, which letter is indicated.

-

Consonants: voiced, sonorous or voiceless, paired or unpaired; hard or soft, paired or unpaired; which letter is indicated.

-

The total number of letters and sounds.

You can disassemble words by sounds and letters orally or in writing. These methods are slightly different from each other, so let's consider each one separately. We write down the word and all the sounds that are included in it.

Syllables and stress. We count and write down the number of syllables in a word, we denote the one on which the stress falls.

Sounds. From the next line in a column, we rewrite all the letters in the order in which they appear in the word. Opposite each of them we record the sound and enclose it in square brackets.

From the next line in a column, we rewrite all the letters in the order in which they appear in the word. Opposite each of them we record the sound and enclose it in square brackets.

Vowel sounds. Next to each vowel we write whether it is stressed or unstressed. And then we indicate what letter it is designated.

Consonants. Next to each consonant, indicate whether it is voiced or voiceless. Further - paired or unpaired in deafness-sonority. After that, we write, hard or soft sound, and then - paired or unpaired in terms of softness-hardness. At the end, you need to indicate which letter denotes the sound.

Number of letters, sounds. We count and write down the number of letters and sounds in a word.

Now let's use this algorithm with examples.

Example No. 1. Written phonetic analysis of the verb search

Search [abysk'ivat'] - 4 syllables, 2nd stressed.

o - [a] - ch., unstressed.

b - [b] - acc., sound. couple, tv par.

s - [s] - ch., shock.

s - [s] - acc., deaf. couple, tv par.

k - [k'] - acc., deaf. steam, soft par.

and - [and] - Ch., unstressed.

c - [c] - acc., sound. couple, tv par.

a - [a] - Ch., unstressed.

t - [t'] - acc., deaf. steam, soft par.

b — [–]

10 points, 9 stars

Example No. 2. Written phonetic analysis of the adjective spring

Spring [v'is'en':y'] - 3 syllables, 2nd stressed.

in - [in '] - acc. , sound. steam, soft par.

, sound. steam, soft par.

e - [i] - gl., unstressed.

s - [s'] - acc., deaf. steam, soft par.

e - [e] - ch., percussion.

n - [n':] - acc., sonorn. unpaired, soft par.

and - [and] - Ch., unstressed.

th - [th'] - acc., sonorn. unpaired, soft unpaired

8 points, 7 stars

Example No. 3. Written phonetic analysis of a noun professor

Professor [praf'es:ar] - 3 syllables, 2nd stressed.

p - [n] - acc., deaf. couple, tv par.

р - [р] - acc., sonorn. unpaired, tv. par.

o - [a] - ch., unstressed.

f - [f'] - acc., deaf. steam, soft par.

e - [e] - ch., percussion.

s - [s:] - acc., deaf. couple, tv par.

o - [a] - ch. , unstressed.

, unstressed.

р - [р] - acc., sonorn. unpaired, tv. par.

9 points, 8 stars

Sample oral phonetic analysis

If you need to do sound-letter analysis orally, follow this algorithm:

-

Syllables and stress. Count and name the number of syllables in a word, indicate the one that is stressed.

-

Vowel sounds. Name the vowels in the order in which they sound in the word. For each of them, determine whether it is percussion or unstressed. Then specify the letters with which they are indicated.

-

Consonants. For each of the consonants, determine whether it is voiced or voiceless, and then - paired or unpaired according to deafness-voicedness. After that, establish whether the sound is hard or soft, as well as paired or unpaired in terms of softness-hardness.

At the end of the analysis of each of the consonants, specify which letter it is designated in the word.

At the end of the analysis of each of the consonants, specify which letter it is designated in the word. -

Number of letters, sounds. Count and name the number of letters and sounds in a word.

Let's practice oral phonetic analysis on the example of the same words that we have analyzed above.

Example No. 1. Oral phonetic analysis of the verb search

2. Vowels:

first - unstressed [a], marked with the letter about ;

second - shock [s], designated by the letter s ;

third - unstressed [and], marked with the letter and ;

fourth - unstressed [a], designated by the letter a .

3. Consonants:

[b] - voiced double, solid double, marked with the letter b ;

[s] - deaf double, solid double, marked with the letter from ;

[k'] - deaf double, soft double, marked with the letter to ;

[c] - voiced double, hard double, marked with the letter in ;

[t'] - deaf double, soft double, marked with the letter t ;

letter ь does not represent sound.

4. In the word search 10 letters and 9 sounds.

Example No. 2. Oral phonetic analysis of the adjective spring

2. Vowels:

the first is unstressed [i], marked with the letter e ;

second - shock [e], designated by the letter e ;

third - unstressed [and], marked with the letter and .

3. Consonants:

[v'] - voiced double, soft double, marked with the letter in ;

[s'] - deaf double, soft double, marked with the letter from ;

[n'] - voiced unpaired (sonor), soft paired, marked with the letter n . The second n does not form a sound in a word;

[d'] - voiced unpaired (sonor), hard unpaired, marked with the letter and .

4. The word spring has 8 letters and 7 sounds.

Example No. 3. Oral phonetic analysis of the noun professor

2. Vowels:

first - unstressed [a], marked with the letter about ;

second - shock [e], designated by the letter e ;

third - unstressed [a], designated by the letter about .

3. Consonants:

[p] - deaf double, hard double, marked with the letter p ;

[p] - voiced unpaired (sonor), solid paired, marked with the letter p ;

[f'] - deaf double, soft double, marked with the letter f ;

[s] - deaf double, solid double, marked with the letter with . The second with does not form a sound in a word;

[p] - voiced unpaired (sonor), solid paired, marked with the letter p .

4. The word professor has 9 letters and 8 sounds.

Test yourself

Let's see how well you understand what phonetic parsing is. Below you will find three tasks with which you can practice this skill.

Task 1

Disassemble the following words according to their sound composition: busy, guest, vacancy, pronounce, speaking.

Task 2

Perform oral phonetic analysis of words: box, hospital, go, union, marine.

Task 3

Read the short text below and make a written phonetic analysis of all the nouns in it.

We wandered in the forest in spring and observed the life of hollow birds: woodpeckers, owls. Suddenly, in the direction where we had previously planned an interesting tree, we heard the sound of a saw. It was, we were told, cutting firewood from deadwood for a glass factory.