How many syllables in elementary

Six Syllable Types | Reading Rockets

By: Louisa Moats, Carol Tolman

Six written syllable-spelling conventions are used in English spelling. These were regularized by Noah Webster to justify his 1806 dictionary's division of syllables. The conventions are useful to teach because they help students remember when to double letters in spelling and how to pronounce the vowels in new words. The conventions also help teachers organize decoding and spelling instruction.

Warm-up: Why double?

Read this fascinating tale. As you read, underline words in which there are two or more consonants between the first and second syllables.

Thunker's pet cats, Pete and Kate, enjoyed dining on dinner. They were fated to fatness. The pet Pete, who was cuter than Kate, was a cutter cat with sharp claws and teeth, scary scars, and one jagged ear.

Pete was ripping up ripening apples and biting bitter strips of striped bug bits as he stared into the starry night.

The cat Kate was not as scared or scarred. Kate liked licking slimy slops that slopped from a bucket, sitting at a site that sloped and caused the slop to slide. Kate liked sitting at the site where the slops slid.

— Created by Bruce Rosow (Moats & Rosow, 2003)

What do you notice about the vowel sounds that come before the doubled consonants?

Why teach syllables?

Without a strategy for chunking longer words into manageable parts, students may look at a longer word and simply resort to guessing what it is — or altogether skipping it. Familiarity with syllable-spelling conventions helps readers know whether a vowel is long, short, a diphthong, r-controlled, or whether endings have been added. Familiarity with syllable patterns helps students to read longer words accurately and fluently and to solve spelling problems — although knowledge of syllables alone is not sufficient for being a good speller.

Spoken and written syllables are different

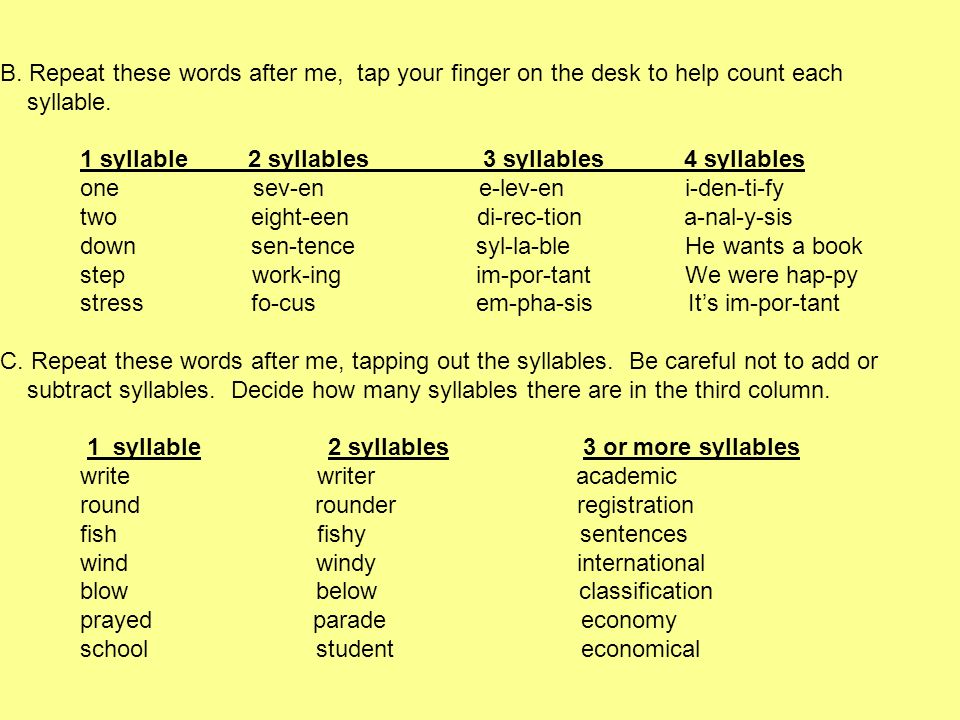

Say these word pairs aloud and listen to where the syllable breaks occur:

bridle – riddle table – tatter even – ever

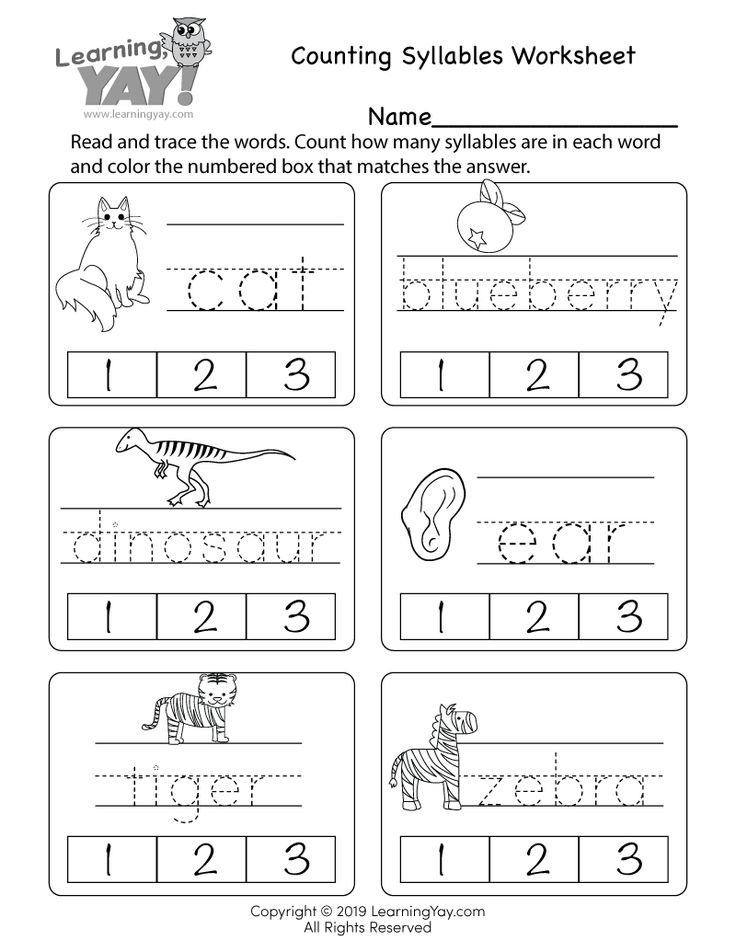

Spoken syllables are organized around a vowel sound. Each word above has two syllables. The jaw drops open when a vowel in a syllable is spoken. Syllables can be counted by putting your hand under your chin and feeling the number of times the jaw drops for a vowel sound.

Each word above has two syllables. The jaw drops open when a vowel in a syllable is spoken. Syllables can be counted by putting your hand under your chin and feeling the number of times the jaw drops for a vowel sound.

Spoken syllable divisions often do not coincide with or give the rationale for the conventions of written syllables. In the first word pair above, you may naturally divide the spoken syllables of bridle between bri and dle and the spoken syllables of riddle between ri and ddle. Nevertheless, the syllable rid is "closed" because it has a short vowel; therefore, it must end with consonant. The first syllable bri is "open," because the syllable ends with a long vowel sound. The result of the syllable-combining process leaves a double d in riddle (a closed syllable plus consonant-

le) but not in bridle (open syllable plus consonant-le). These spelling conventions are among many that were invented to help readers decide how to pronounce and spell a printed word.

These spelling conventions are among many that were invented to help readers decide how to pronounce and spell a printed word.

The hourglass illustrates the chronology or sequence in which students learn about both spoken and written syllables. Segmenting and blending spoken syllables is an early phonological awareness skill; reading syllable patterns is a more advanced decoding skill, reliant on student mastery of phoneme awareness and phoneme-grapheme correspondences.

Figure 5.1. Hourglass Depiction of the Relationship Between Awareness in Oral Language and Written Syllable Decoding

(Contributed by Carol Tolman, and used with permission.)

Click to see full image

Closed syllables

The closed syllable is the most common spelling unit in English; it accounts for just under 50 percent of the syllables in running text. When the vowel of a syllable is short, the syllable will be closed off by one or more consonants. Therefore, if a closed syllable is connected to another syllable that begins with a consonant, two consonant letters will come between the syllables (

com-mon, but-ter).

Two or more consonant letters often follow short vowels in closed syllables (dodge, stretch, back, stuff, doll, mess, jazz). This is a spelling convention; the extra letters do not represent extra sounds. Each of these example words has only one consonant phoneme at the end of the word. The letters give the short vowel extra protection against the unwanted influence of vowel suffixes (backing; stuffed; messy).

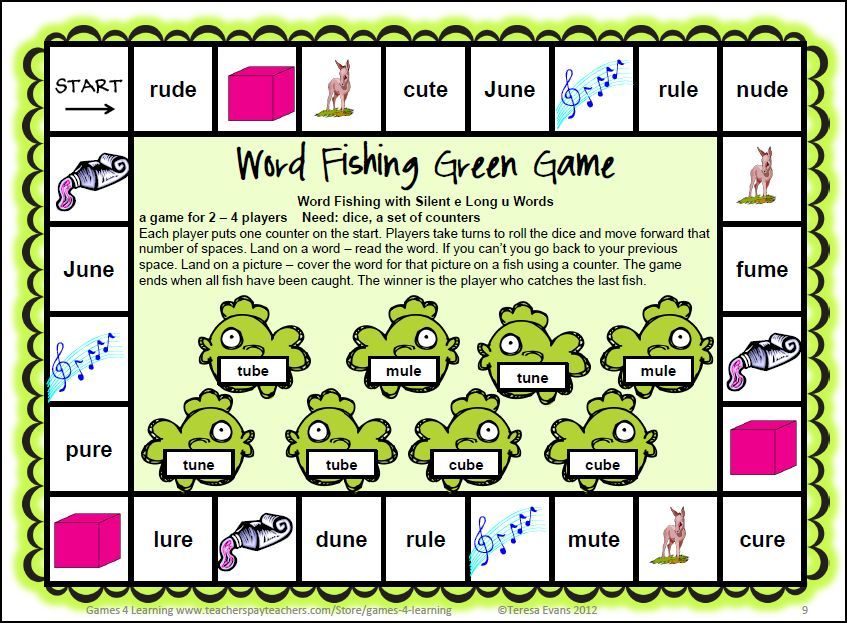

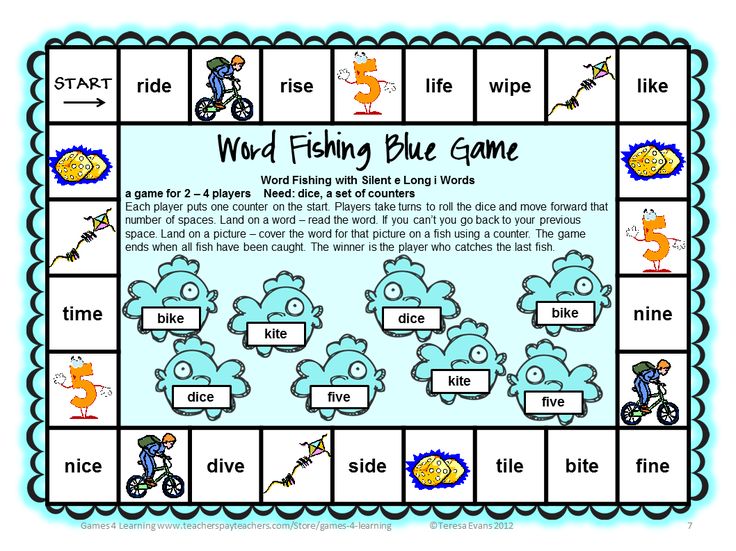

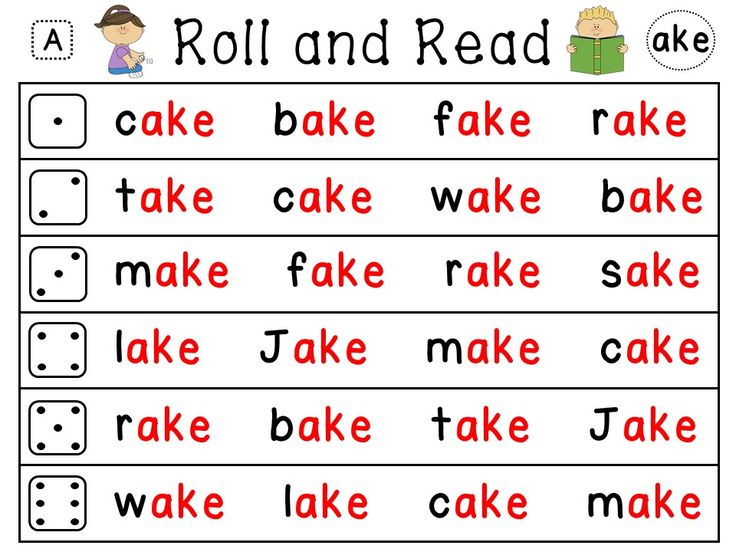

Vowel-Consonant-e (VCe) syllables

Also known as "magic e" syllable patterns, VCe syllables contain long vowels spelled with a single letter, followed by a single consonant, and a silent e. Examples of VCe syllables are found in wake, whale, while, yoke, yore, rude, and hare. Every long vowel can be spelled with a VCe pattern, although spelling "long e" with VCe is unusual.

Open syllables

If a syllable is open, it will end with a long vowel sound spelled with one vowel letter; there will be no consonant to close it and protect the vowel (to-tal, ri-val, bi-ble, mo-tor). Therefore, when syllables are combined, there will be no doubled consonant between an open syllable and one that follows.

Therefore, when syllables are combined, there will be no doubled consonant between an open syllable and one that follows.

A few single-syllable words in English are also open syllables. They include me, she, he and no, so, go. In Romance languages — especially Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian — open syllables predominate.

Vowel team syllables

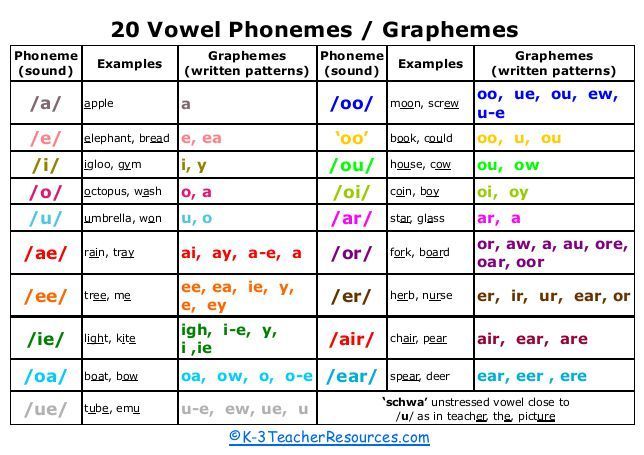

A vowel team may be two, three, or four letters; thus, the term vowel digraph is not used. A vowel team can represent a long, short, or diphthong vowel sound. Vowel teams occur most often in old Anglo-Saxon words whose pronunciations have changed over hundreds of years. They must be learned gradually through word sorting and systematic practice. Examples of vowel teams are found in thief, boil, hay, suit, boat, and straw.

Sometimes, consonant letters are used in vowel teams. The letter y is found in ey, ay, oy, and uy, and the letter w is found in ew, aw, and ow. It is not accurate to say that "w can be a vowel," because the letter is working as part of a vowel team to represent a single vowel sound. Other vowel teams that use consonant letters are -augh, -ough, -igh, and the silent -al spelling for /aw/, as in walk.

Other vowel teams that use consonant letters are -augh, -ough, -igh, and the silent -al spelling for /aw/, as in walk.

Vowel-r syllables

We have chosen the term "vowel-r" over "r-controlled" because the sequence of letters in this type of syllable is a vowel followed by r (er, ir, ur, ar, or). Vowel-r syllables are numerous, variable, and difficult for students to master; they require continuous review. The /r/ phoneme is elusive for students whose phonological awareness is underdeveloped. Examples of vowel-r syllables are found in perform, ardor, mirror, further, worth, and wart.

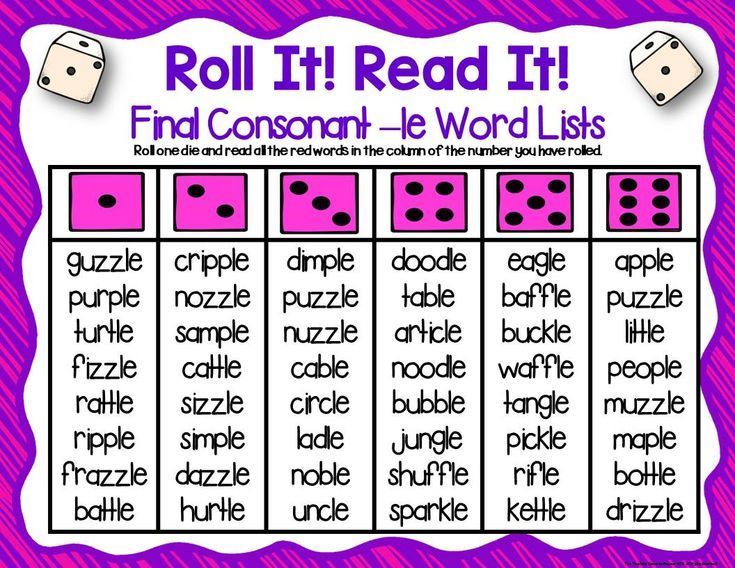

Consonant-le (C-le) syllables

Also known as the stable final syllable, C-le combinations are found only at the ends of words. If a C-le syllable is combined with an open syllable — as in cable, bugle, or title — there is no doubled consonant. If one is combined with a closed syllable — as in dabble, topple, or little — a double consonant results.

If one is combined with a closed syllable — as in dabble, topple, or little — a double consonant results.

Not every consonant is found in a C-le syllable. These are the ones that are used in English:

| -ble (bubble) | -fle (rifle) | -stle (whistle) | -cle (cycle) |

| -gle (bugle) | -tle (whittle) | -ckle (trickle) | -kle (tinkle) |

| -zle (puzzle) | -dle (riddle) | -ple (quadruple) |

Simple and complex syllables

Closed, open, vowel team, vowel-r, and VCe syllables can be either simple or complex. A complex syllable is any syllable containing a consonant cluster (i. e., a sequence of two or three consonant phonemes) spelled with a consonant blend before and/or after the vowel. Simple syllables have no consonant clusters.

e., a sequence of two or three consonant phonemes) spelled with a consonant blend before and/or after the vowel. Simple syllables have no consonant clusters.

| Simple | Complex |

|---|---|

| late | plate |

| sack | stack |

| rick | shrink |

| tee | tree |

| bide | blind |

Complex syllables are more difficult for students than simple syllables. Introduce complex syllables after students can handle simple syllables.

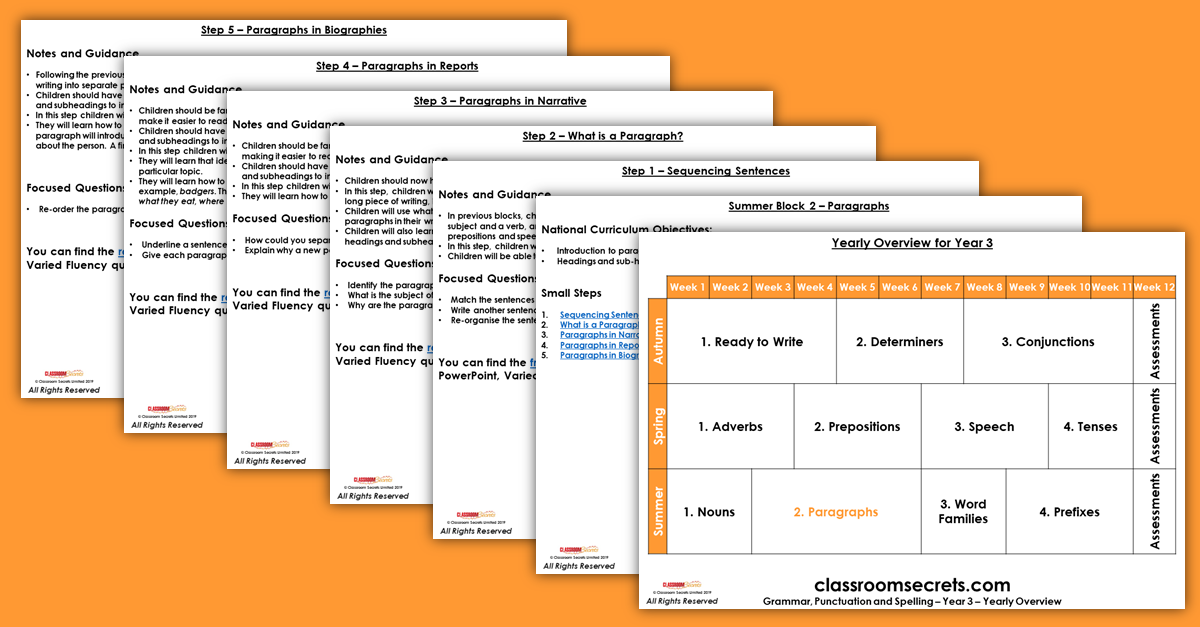

Table 5.1. Summary of Six Types of Syllables in English Orthography

| Syllable Type | Examples | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Closed | dap-ple hos-tel bev-er-age | A syllable with a short vowel, spelled with a single vowel letter ending in one or more consonants. |

| Vowel-Consonant-e (VCe) | com-pete des-pite | A syllable with a long vowel, spelled with one vowel + one consonant + silent e. |

| Open | pro-gram ta-ble re-cent | A syllable that ends with a long vowel sound, spelled with a single vowel letter. |

| Vowel Team (including diphthongs) | aw-ful train-er con-geal spoil-age | Syllables with long or short vowel spellings that use two to four letters to spell the vowel. Diphthongs ou/ow and oi/oy are included in this category. |

| Vowel-r (r-controlled) | in-jur-i-ous con-sort char-ter | A syllable with er, ir, or, ar, or ur. Vowel pronunciation often changes before /r/. |

| Consonant-le (C-le) | drib-ble bea-gle lit-tle | An unaccented final syllable that contains a consonant before /l/, followed by a silent e. |

| Leftovers: Odd and Schwa syllables | dam-age act-ive na-tion | Usually final, unaccented syllables with odd spellings. |

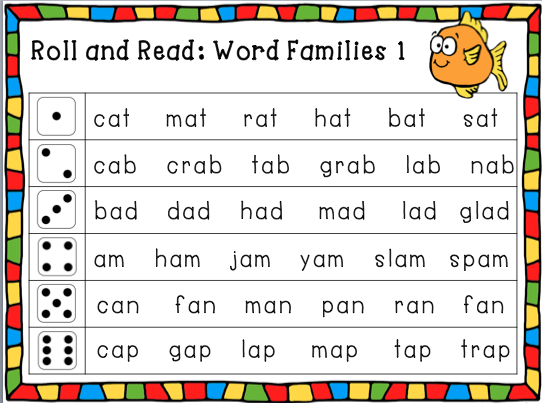

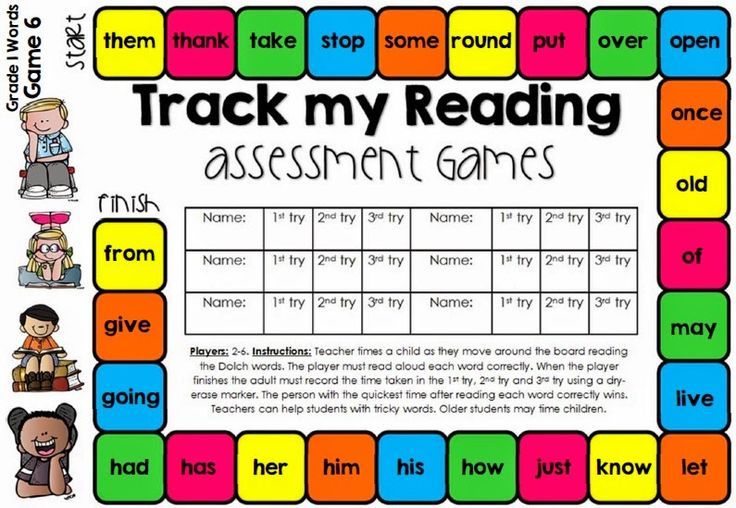

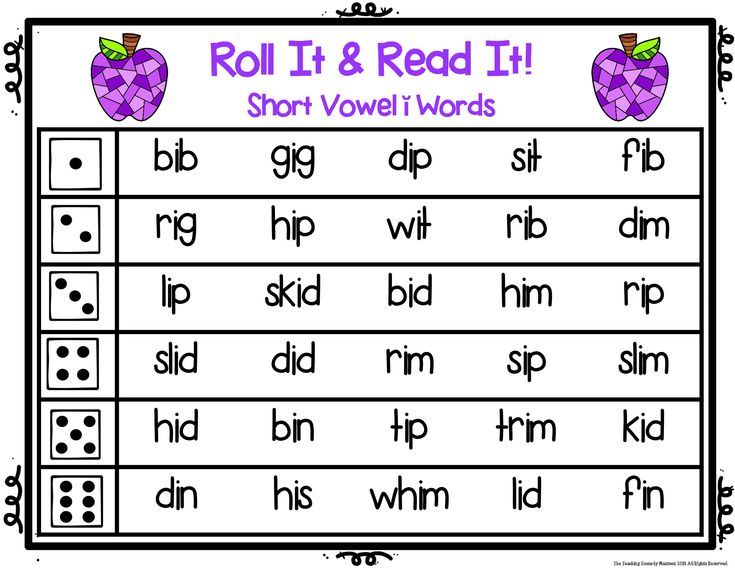

Syllable Games | Classroom Strategies

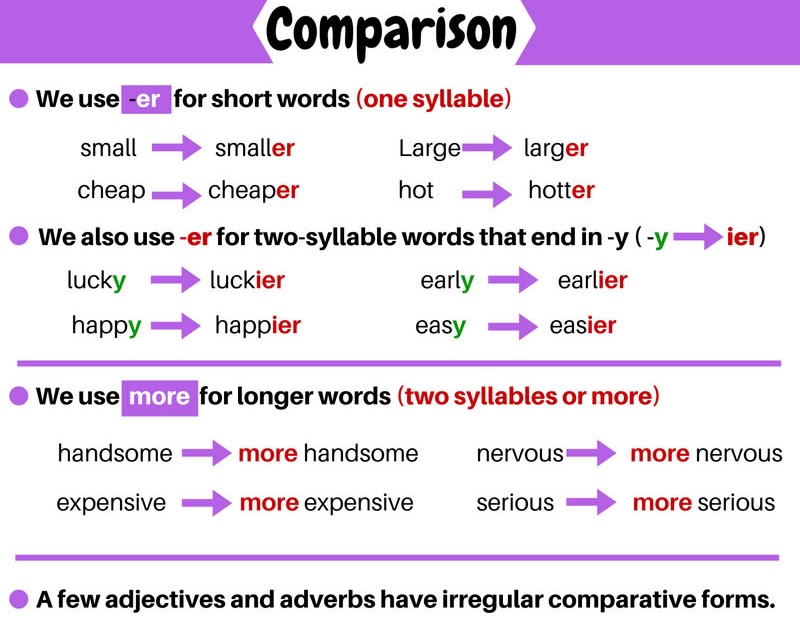

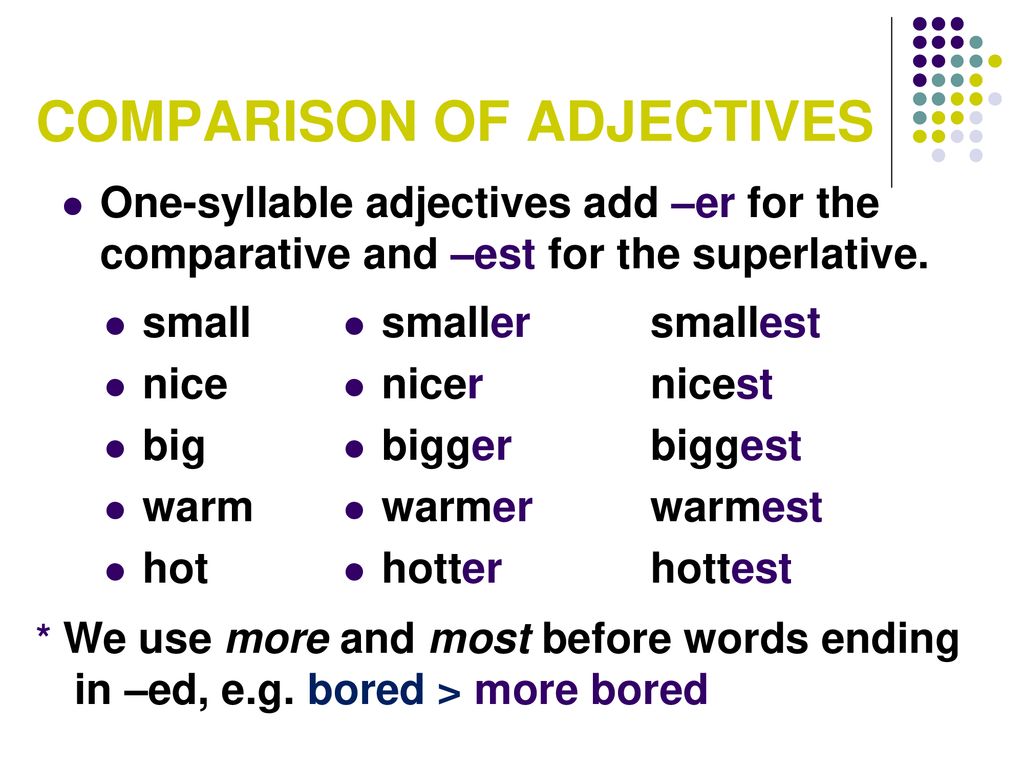

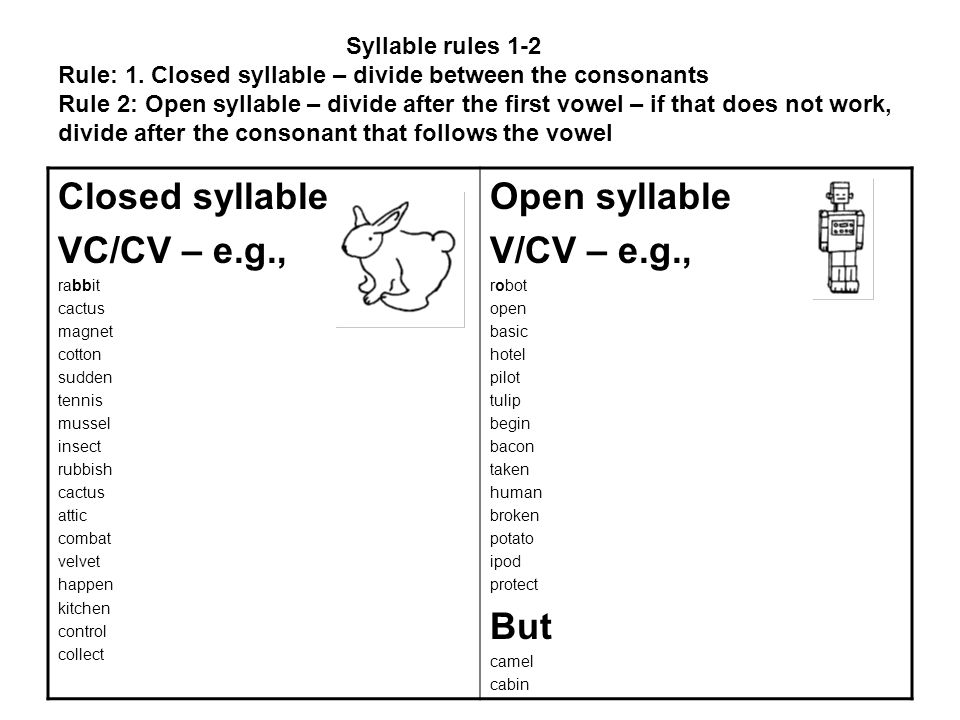

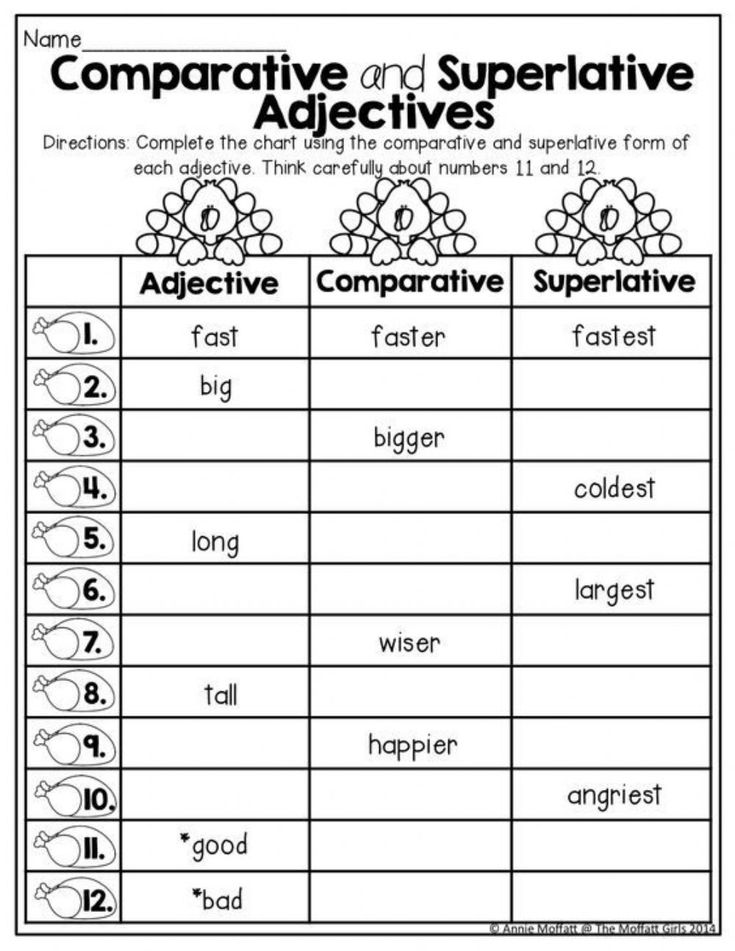

As students progress in their literacy understanding, they move from reading and writing single syllable words (often with consonant-vowel-consonant constructions) to reading and writing multisyllabic words. Instruction focused on teaching students about syllables often focuses on teaching different types of syllables (open and closed) and what occurs when syllables join together within a word.

| How to use: | Individually | With small groups | Whole class setting |

More phonological awareness strategies

Why teach about syllables?

- Dividing words into parts, or "chunks" helps speed the process of decoding.

- Knowing the rules for syllable division can students read words more accurately and fluently.

- Understanding syllables can also help students learn to spell words correctly.

Drumming out syllables

Students use a drum or tambourine to take turns drumming out the syllables in their names or other words. See the lesson plan.

This video is published with permission from the Balanced Literacy Diet. See many more related how-to videos with lesson plans in the Phonemic Awareness section.

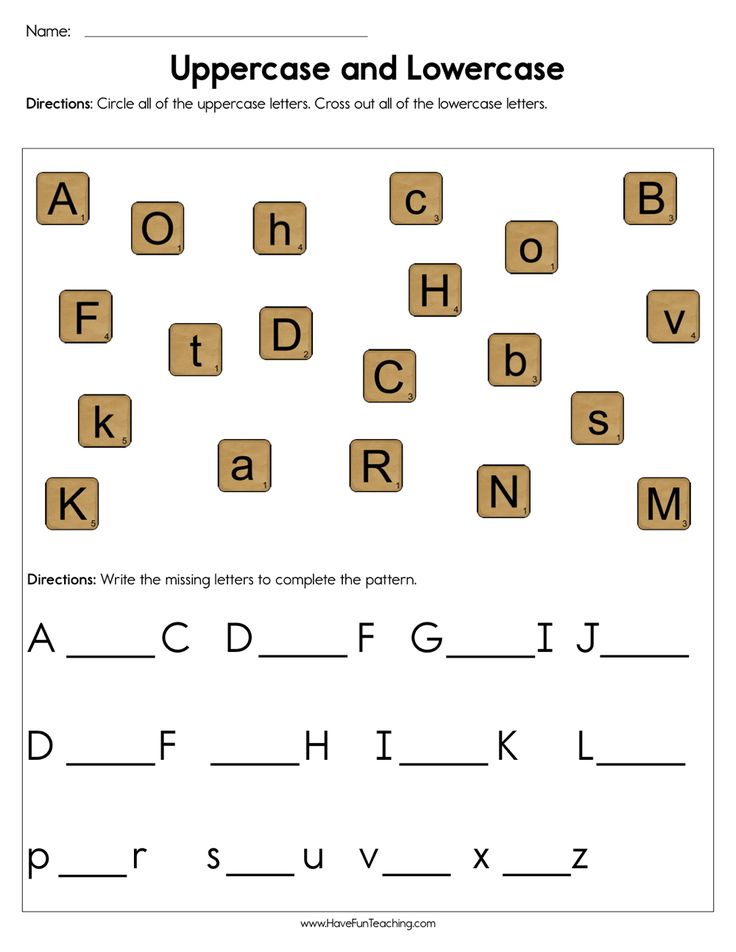

Syllables: kindergarten

This video depicts a kindergarten small group engaging in a syllables activity. There are 5 students in this demonstration and they are using manipulatives. (From the What Works Clearinghouse practice guide: Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade. )

)

Collect resources

Marker activity

This activity, from our article How Now Brown Cow: Phoneme Awareness Activities, is an example of how to teach students to use a marker (i.e., token) to count syllables.

The marker activity often used for word counting can be adapted for use in counting syllables. Teachers can provide each child with tokens and two or three horizontally connected boxes drawn on a sheet of paper. The children place a token in each box from left to right as they hear each syllable in a word.

Multisyllabic manipulation

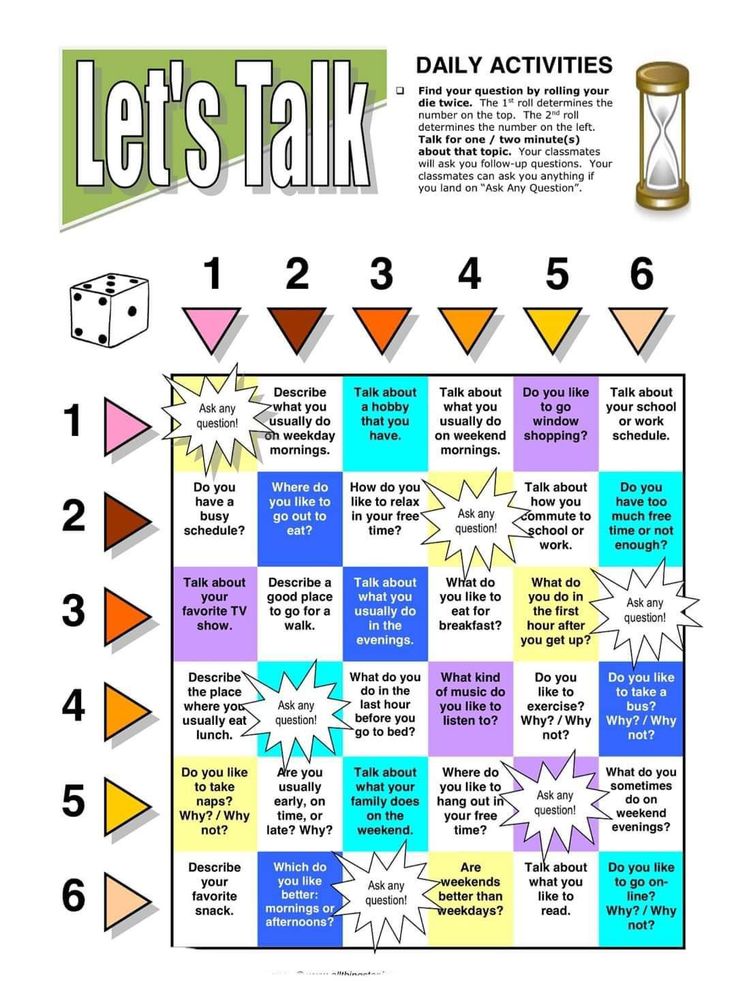

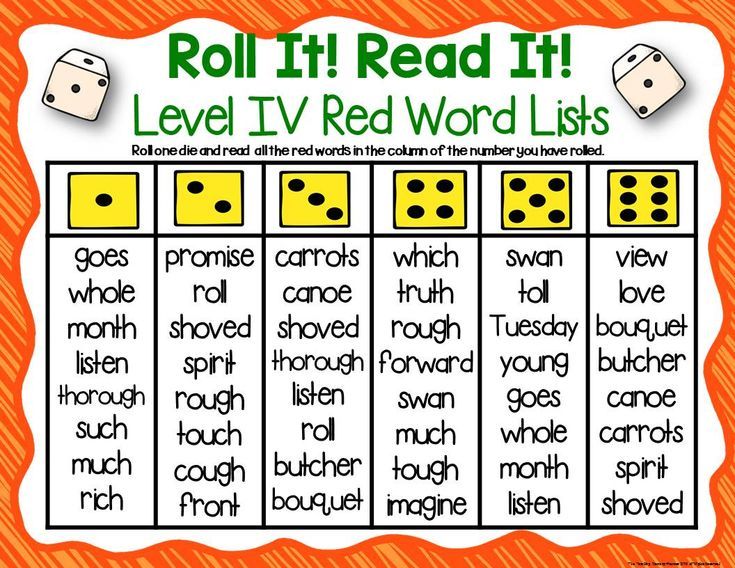

This example includes several activities and a chart of multisyllabic words. One specific activity from this page is the Multisyllabic Words Manipulation Game. Teachers can divide words from reading selections into syllables, write each syllable on a note card and display the syllables in jumbled order. Have students arrange the syllables to form the words.

Have students arrange the syllables to form the words.

Multisyllabic words manipulation >

Clapping games

Associating syllables with a beat can help students to better learn the concept of syllables within words. Here's a clapping game to help young learners understand about dividing words into syllables.

Basic words clapping game >

Using mirrors

The following link includes information on introductory activities such as using mirrors for teaching students about syllables. Information is also provided about the different syllable spelling patterns.

Using a mirror to understand syllables >

Jumping syllables

This activity teaches student to separate words into syllables. Students move syllables around to create new "silly" words which gives them practice manipulating different sounds.

Jumping syllables >

Find many more syllable activities developed by the Florida Center for Reading Research.

Differentiated instruction

for second language learners, students of varying reading skill, and for younger learners

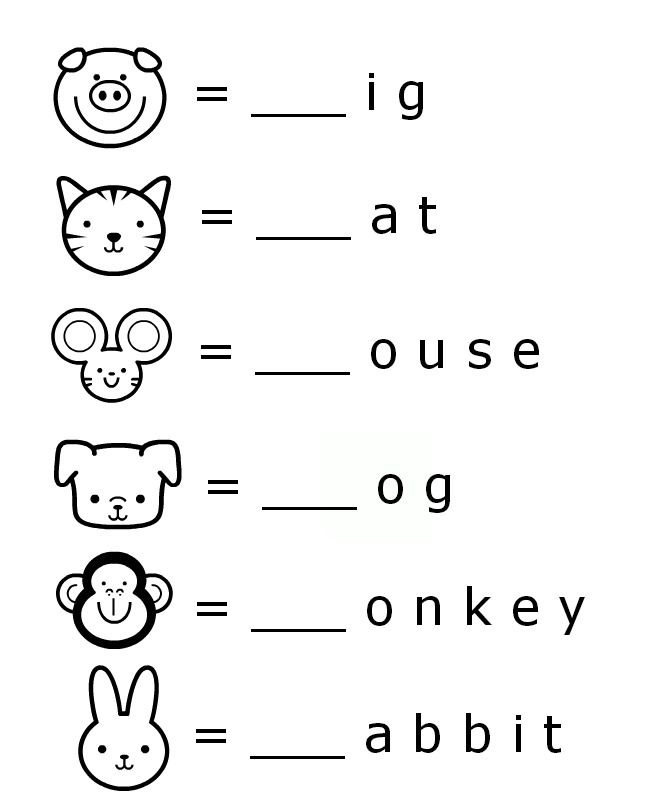

- Use pictures instead of words in activities for younger and lower level readers

- Include auditory and hands-on activities (i.

e., clapping hands, tapping the desk, or marching in place to the syllables in children's names)

e., clapping hands, tapping the desk, or marching in place to the syllables in children's names) - Include a writing activity for more advanced learners.

See the research that supports this strategy

Adams, M., Foorman, B., Lundberg, I., & Beeler, T. (2004). Phonemic Activities for the Preschool or Elementary Classroom.

Ellis, E. (1997). How Now Brown Cow: Phoneme Awareness Activities.

Moats, L. & Tolman, C. (2008). Six Syllable Types.

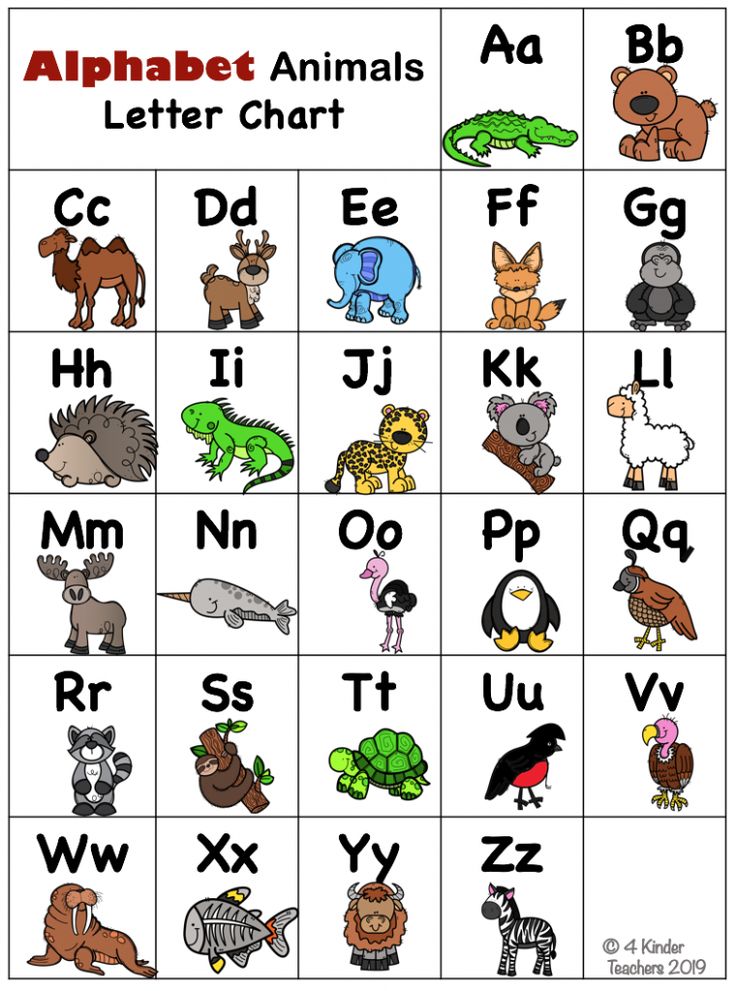

Children's books to use with this strategy

Island: A Story of the Galápagos

By: Jason Chin

Genre: Nonfiction

Age Level: 6-9

Reading Level: Independent Reader

Young readers will explore the evolving terrain and animals of the Galápagos in this nonfiction picture book. Charles Darwin first visited the Galápagos Islands almost 200 years ago, only to discover a land filled with plants and animals that could not be found anywhere else on earth. How did they come to inhabit the island? How long will they remain? Thoroughly researched and filled with intricate and beautiful paintings by award-winning author and artist Jason Chin.

Where Else in the Wild? More Camouflaged Creatures Concealed & Revealed

By: David Schwartz

Age Level: 3-6

Reading Level: Beginning Reader

Close-up, full color photographs of camouflaged creatures and a variety of poems ask readers to examine the image while learning about characteristics. A gatefold opens to provide additional information. (This may appeal to children who like "real" things.)

Dogku

By: Andrew Clements

Age Level: 6-9

Reading Level: Independent Reader

The picture book story of a dog who finds a home is told in completely (and surprisingly successfully) using haiku.

Tap Dancing on the Roof: Sijo (Poems)

By: Linda Sue Park

Genre: Poetry

Age Level: 6-9

Reading Level: Independent Reader

Like haiku, sijo – a little known, brief poetic form from Korea – looks at everyday activities from breakfast to the weather. Sophisticated illustrations complement the seemingly simple language to delight readers and listeners.

Comments

The language prefers some syllables to others not only because of the convenience of pronunciation

There are universal hierarchies of syllables in the language according to their occurrence (preference). For example, in a wide variety of languages, the syllable blog is more common than lbog . Are there abstract rules that prevent such syllables as lbog from gaining a foothold in the language, or is their rarer use due only to the inconvenience of pronunciation? Scientists have found that although syllables that optimize motor costs are fixed in the language, more abstract principles that are not related to the convenience of pronunciation of syllables also affect the selection of syllables. nine0010

Speech is made up of words, and words are combinations of sounds, some of which occur more often than others. Interestingly, there are series of syllables that differ in occurrence in a wide variety of languages in the same way (J. H. Greenberg, 1964. Some generalizations concerning initial and final consonant clusters, Russian translation of this article “Some generalizations concerning possible initial and final consonant sequences " was published in the journal "Problems of Linguistics" No. 4 for 1964 years).

H. Greenberg, 1964. Some generalizations concerning initial and final consonant clusters, Russian translation of this article “Some generalizations concerning possible initial and final consonant sequences " was published in the journal "Problems of Linguistics" No. 4 for 1964 years).

An example of such a universal syllable hierarchy: blif ≻ bnif ≻ bdif ≻ lbif . The syllable bnif is more common than bdif in a variety of languages, but less common than blif . The syllables in this series differ not only in the frequency with which they occur, but also in the ease of recognition. For example, errors in recognition of the syllable lbif will occur more often in subjects than the syllable blif . This pattern is common for adults, children, and speakers of different languages, regardless of whether such a syllable occurs in their native language, and is true even for people with dyslexia (see articles by I. Berent et al. , 2008. Language universals in human brains, I. Berent et al., 2009. Listeners’ knowledge of phonological universals: Evidence from nasal clusters; I. Berent et al., 2013. Phonological generalizations in dyslexia: The phonological grammar may not be impaired).

, 2008. Language universals in human brains, I. Berent et al., 2009. Listeners’ knowledge of phonological universals: Evidence from nasal clusters; I. Berent et al., 2013. Phonological generalizations in dyslexia: The phonological grammar may not be impaired).

Why are there such universal hierarchies of sound combinations according to their preference? A possible explanation is differences in the difficulty of pronouncing syllables. But syllables may be less common in a language, not only because they are harder to pronounce, but also because they are harder to recognize. Previously, it was shown that in the process of perceiving speech sounds in humans, the motor areas of the cortex responsible for the movements of the tongue and lips are activated. Such activation accurately reproduces what happens in the brain of a person who himself makes sounds. So, during the perception of labial consonants ( b , p , v , f ) the motor areas of the brain (see Motor cortex), which are responsible for the movements of the lip muscles, are more activated, and when the anterior lingual consonants are recognized ( z , s , t , l , n ) are areas responsible for tongue movements (F. Pulvermüller et al., 2006. Motor cortex maps articulatory features of speech sounds). Thus, people help themselves to recognize someone else's speech by playing in their head how they themselves would pronounce these sounds. nine0011

Pulvermüller et al., 2006. Motor cortex maps articulatory features of speech sounds). Thus, people help themselves to recognize someone else's speech by playing in their head how they themselves would pronounce these sounds. nine0011

Scientists have suggested that the simplicity or complexity of "internal playback" of syllables affects their preference. Less convenient combinations of sounds should require more active work of the motor cortex (the brain has to play "absurd" movements), which should be less of them. Therefore, the scientists decided to help the subjects' motor areas using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). TMS is a non-invasive technique that helps to activate or, conversely, turn off certain areas of the brain using electromagnetic impulses. Previously, it was shown that stimulation of the activity of certain motor areas improves the recognition of sounds of the corresponding group. Thus, stimulation of the motor areas responsible for the work of the labial muscles improved the recognition of labial consonants, and stimulation of the areas responsible for the functioning of the muscles of the tongue improved the recognition of the anterior lingual consonants (A. D'Ausilio et al., 2009. The motor somatotopy of speech perception).

D'Ausilio et al., 2009. The motor somatotopy of speech perception).

During the experiment, the subjects perceived sound stimuli by ear. These were either syllables from the hierarchical series, or derivatives of them, consisting of two syllables (for example, lbif - lebif ). Participants in the experiment had to determine how many syllables they heard. At the same time, the work of the motor areas of their brain, responsible for the work of the muscles of the lips, was stimulated in some experiments with the help of TMS. The scientists then compared the results to see if the recognition quality syllable hierarchy persisted when the motor areas of the brain were "helped" to work. It turned out that the hierarchy has not changed, that is, for example, syllable blif was still better than bdif . At the same time, TMS did not help to recognize the least convenient combinations of sounds, and even interfered with recognizing more convenient ones (Fig. 2). The same was true for other series of syllables (not found in English) arranged so that a labial consonant was always followed by an anterior lingual. The hierarchy of syllables was preserved despite artificial changes in the activity of motor areas. It turns out that differences in pronunciation difficulty are not the only reason for the preference hierarchy of syllables. nine0011

2). The same was true for other series of syllables (not found in English) arranged so that a labial consonant was always followed by an anterior lingual. The hierarchy of syllables was preserved despite artificial changes in the activity of motor areas. It turns out that differences in pronunciation difficulty are not the only reason for the preference hierarchy of syllables. nine0011

The researchers also checked with MRI what happens to the metabolism in the brain during the processing of syllables occupying different levels of the hierarchy. Scientists assumed that the least convenient syllables required the most motor input, but it turned out that the opposite is true. When less convenient syllables are recognized, the motor areas of the cortex responsible for lip movements are less active, and TMS does not help them. Apparently, syllables from the lower levels of the hierarchy (such as lbif ) are less preferred not because they are associated with the greatest motor costs, but, on the contrary, their lower preference reduces the activity of motor areas, which leads to worse recognition. That is, the activity of motor areas is not the cause of linguistic preferences, but their consequence. nine0011

That is, the activity of motor areas is not the cause of linguistic preferences, but their consequence. nine0011

Interestingly, when recognizing sounds masked by noise, motor areas, on the contrary, work most actively, as if trying to help a person to make out them (Y. Du et al., 2014. Noise differentially impacts phoneme representations in the auditory and speech motor systems ). But when it is necessary to recognize “uncomfortable” syllables, for some reason the motor areas “wash their hands”.

It turns out that the existence of universal series of syllables with different preferences is explained not only by differences in the complexity of their pronunciation and in the activity of the corresponding areas of the brain. Apparently, the basic elements that make up speech are also selected according to other criteria, such as productivity - the ability to combine well with many other syllables. This is suggested by the mistakes of the subjects, which they made when recognizing less convenient syllables: the subjects more often took such a syllable for two, adding a vowel between two consonants (instead of lbif - lebif ). Such constructions would be easier to combine with each other than to make combinations of several syllables like lbif . Apparently, not only the convenience of pronunciation of sounds and the complexity of their representations in the brain, but also more abstract linguistic laws play a role in the selection of syllables at the level of human physiology.

Such constructions would be easier to combine with each other than to make combinations of several syllables like lbif . Apparently, not only the convenience of pronunciation of sounds and the complexity of their representations in the brain, but also more abstract linguistic laws play a role in the selection of syllables at the level of human physiology.

Source: Iris Berent, Anna-Katharine Brem, Xu Zhao, Erica Seligson, Hong Pan, Jane Epstein, Emily Stern, Albert M. Galaburda, and Alvaro Pascual-Leone. Role of the motor system in language knowledge // PNAS . 2015. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1416851112.

Yulia Kondratenko

Hieroglyphics. Elemental Traits. Basic Chinese calligraphy rules

Learn Chinese from scratch!Hieroglyphics |

General Information

One of the main difficulties facing every Chinese learner is mastering Chinese characters, which have been the standard Chinese writing system for at least three and a half millennia. nine0011

nine0011

What are hieroglyphs? What is their specificity that distinguishes Chinese characters from other scripts of the world? To answer this question, you need to know that any writing system can be classified into one of two main types.

The first of them (phonetic) includes systems whose signs serve to record the sound of certain linguistic units. These include alphabets that include letters and record individual sounds (an example is the Chinese alphabet), and syllabic scripts , fixing whole syllables (this variety of phonetic scripts includes, in particular, Japanese katakana and hiragana ).

The second type of writing (ideographic, or hieroglyphic) is characterized by the fact that signs serve to record the lexical meaning of speech units - syllables or words. The Chinese writing system is of this type.

Hieroglyphic writing differs from alphabetic or syllabic in that it includes a much larger number of characters. The alphabet can have two or three dozen letters, syllabic systems have hundreds of characters, and hieroglyphic systems have several thousand or even tens of thousands. nine0011

The alphabet can have two or three dozen letters, syllabic systems have hundreds of characters, and hieroglyphic systems have several thousand or even tens of thousands. nine0011

In Chinese, each significant syllable (morpheme) is represented by a separate character; To write a word, you need as many characters as there are syllables in it. In total, the Chinese language has about 400 syllables that differ in sound composition; the presence of tones increases this number by three to four times. The number of different morphemes is many times greater, which is explained by the presence of homonyms. This is why there are so many characters in Chinese writing.

In the official list of only the most commonly used characters, there are 3000 of them. In order to read, for example, the People's Daily newspaper, you need to know at least 4 thousand hieroglyphs, and even more to understand special or literary texts. In The Big Chinese-Russian Dictionary, ed. prof. Oshanin more than 40 thousand hieroglyphs; in the Chinese explanatory dictionary "Kangxi Zidian" - there are about 48 thousand of them. nine0011

nine0011

The need to memorize a large number of characters is one of the main difficulties associated with mastering the Chinese writing system.

At the same time, most Chinese characters are complex in structure, which makes them difficult to memorize.

If you don’t remember something from this lesson, don’t worry, just move on to the next one (you don’t need to do this with the next!)

Main features

elementary hell . There are only eight main features:| horizontal | ||

| vertical | 千士巾 | |

| tilt right | 欠又文 | |

| left hinged | ||

| oblique intersecting | nine0094 戈戰戒||

| ascendant | 冰決波 | |

| dot right | 六玉交 | |

| dot left | 心小亦 |

In the first column - the trait, in the second - its name, in the third - examples.

Hooked Traits

Some traits have spelling variations. So, horizontal, vertical and folding to the right can end with a slight bend - "hook". There are a total of five such traits with a hook:

| horizontal hook down | ||

| vertical with left hook | 水月則 | |

| vertical with hook right | ||

| vertical curved hook up | 也巳兒 | |

| Inclined intersecting with hook up | 民划戎 |

Broken lines

In addition to the main lines and their variants with a hook, in hieroglyphs there are continuous spellings of several lines, which we will call broken lines. There are six such traits:

There are six such traits:

| horizontal polyline with vertical | 口曰田 | |

| horizontal broken line with hinged left | 又久夕 | |

| 3-fold, hinged to the left | 建延廷 | |

| vertical broken line with horizontal | 山世凶 | |

| left hinged broken with horizontal | 厶紅允 | |

| hinged to the left broken line with hinged to the right |

The name of the broken line (horizontal, vertical, folding) is given by its initial part. nine0011

Broken lines with a hook

Broken lines can also be combined with a hook. There are only five such traits:

There are only five such traits:

| horizontal broken line with vertical and left hook | 刁力那 | |

| horizontal polyline with vertical and right hook | 话讨许 | |

| horizontal triple broken with vertical and left hook | nine0094 乃鼐汤||

| horizontal broken line with right hinged and hook up | ||

| vertical doubly broken with left hook |

These 24 features make up all Chinese characters in their modern writing.

The number of strokes that form modern Chinese characters can vary greatly. If in the most simple hieroglyphs in their structure there are one or two lines, then in the most complex there can be two or three dozen or even more. For example, the sign "bright" consists of 28 lines, and "stuffy nose" of 36! However, such examples are by no means isolated. nine0011

For example, the sign "bright" consists of 28 lines, and "stuffy nose" of 36! However, such examples are by no means isolated. nine0011

It is very important to learn how to quickly and accurately distinguish its constituent features in a hieroglyph and correctly count their total number, because in many dictionaries, library catalogs, etc., hieroglyphs are arranged in ascending order of the number of features.

In addition, when writing hieroglyphs, it is necessary to strictly observe the sequence of strokes.

The sequence of writing strokes in a hieroglyph follows strict rules:

-

the hieroglyph is written from top to bottom; nine0011

-

the hieroglyph is written from left to right;

-

horizontal lines are written first, then vertical and fold-out ones; the lower horizontal line, if it does not intersect, is written after the vertical one;

-

first written folded to the left, then - folded to the right;

-

first, the lines that make up the outer contour of the sign are written, then the lines inside it; the line that closes the contour from below is written last; nine0011

-

First, a vertical line located in the center is written (if it does not intersect with horizontal lines), then - side lines;

-

the dot on the right is written last.

It should be borne in mind that a hieroglyph of any complexity, regardless of the number of its constituent features, must fit into a square of a given size. It is recommended to write hieroglyphs on squared paper, allocating four cells for each hieroglyph and making a gap between the hieroglyphs. Graphic elements in signs with a small number of strokes should be written enlarged, and in complex signs - compacted. nine0011

For example:

口器讓聲敬句

Tasks and exercises

-

Write one line each of the elementary features of Chinese characters.

-

Find familiar features in the following characters:

上主正本三開在羊

-

Based on the rules of calligraphy given in the lesson, determine the order of strokes when writing the following characters:

公里共六古天皂玉

究宗固涼羊森草旬

-

Determine how the characters in each of the following pairs differ:

木术手毛甲由午牛

The art of calligraphy

When we talked about calligraphy above in connection with the analysis of Chinese characters, we had in mind, first of all, the observance of the correct sequence of their elementary features. But the term "calligraphy", as you know, has another meaning - the ability to write not only correctly, but also beautifully. In China, calligraphy has long been one of the traditional types of high professional art, along with painting. nine0011

But the term "calligraphy", as you know, has another meaning - the ability to write not only correctly, but also beautifully. In China, calligraphy has long been one of the traditional types of high professional art, along with painting. nine0011

It is impossible to imagine a traditional Chinese painting without hieroglyphs masterfully written on it; and inscriptions in a variety of handwritings still adorn the study of a scientist in China or are hung on the doors of houses on major holidays.

And this is no coincidence. Hieroglyphs provide abundant food for the perception of them not just as signs of writing, but as certain artistic images containing no less diverse information than the text itself, and capable of delivering aesthetic pleasure. nine0011

The high standards that were traditionally set for everyone who sat down at the desk required the obligatory mastery of special skills, and they were given by years of hard training.

It is not surprising that in China the ability to write hieroglyphs correctly and beautifully has always been considered and is still considered an essential sign of intelligence.