How to child

Guide to Modern Parenting - Well Guides

By Perri Klass, M.D. and Lisa Damour

Illustrations by Julia Rothman

We all want to be the best parents we can be for our children, but there is often conflicting advice on how to raise a kid who is confident, kind and successful. And every aspect of being a parent has been more complicated and more fraught during the pandemic, with parents managing complex new assignments and anxious new decisions, all while handling the regular questions that come up in daily life with the children we love. Throughout the circus act of parenting, it’s important to focus on balancing priorities, juggling responsibilities and quickly flipping between the needs of your children, other family members and yourself. Modern parents have the entire internet at their disposal and don’t follow any single authority. It’s hard to know whom or what to trust. Here, we’ll talk about how to help your child grow up to be a person you really like without losing yourself in the process.

Your Parenting Style

Good news: There is no one right way to raise a child.

Research tells us that to raise a self-reliant child with high self-esteem, it is more effective to be authoritative than authoritarian. You want your child to listen, respect and trust you rather than fear you. You want to be supportive, but not a hovering, helicopter parent.

All of these things are easy to set as goals, but hard to achieve. How do you find the right balance?

As your child develops, the challenges will change, and your thinking may evolve, but your approach should be consistent, firm and loving. Help your child learn through experience that making an effort builds confidence and helps you learn to tackle challenges. Calibrate your expectations about what your child is capable of doing independently, whether you have an infant learning to sleep through the night, a toddler helping to put toys away, or an older child resolving conflicts.

Remember, there is no one right way to raise a child. Do your best, trust yourself and enjoy the company of the small person in your life.

Do your best, trust yourself and enjoy the company of the small person in your life.

More on Parenting Styles

Conquering the Basics

Your healthy attitude toward sleep, food and discipline will affect your children in the most important ways.

How to Put a Baby to Sleep

Right from the beginning, babies vary tremendously in their sleep patterns. And parents, too, vary in terms of how they cope with interrupted nights.

There are two general schools of thought around babies and sleep after those early months when they need nighttime feedings — soothe the baby to sleep or don’t — and many parents find themselves wavering back and forth. Those who believe in sleep training, including many sleep experts, would argue that in helping babies learn to fall asleep by themselves and soothe themselves back to sleep when they wake during the night, parents are helping them master vital skills for comfort and independence.

Two techniques for this are:

- Graduated extinction, in which babies are allowed to cry for short, prescribed intervals over the course of several nights.

- Bedtime fading, in which parents delay bedtime in 15-minute increments so the child becomes more and more tired.

And many parents report that these strategies improve their children’s sleep patterns, as well as their own. But there are also parents who find the idea of letting a baby cry at night unduly harsh.

Whatever you try, remember, some babies, no matter what you do, are not reliably good sleepers. Parents need to be aware of what sleep deprivation may be doing to them, to their level of functioning, and to their relationships, and take their own sleep needs seriously as well. So, ask for help when you need it, from your pediatrician or a trusted friend or family member.

Bedtime

For older children, the rules around sleep are clearer: Turn off devices, read aloud at bedtime, and build rituals that help small children wind down and fall asleep.

Establishing regular bedtime routines and consistent sleep patterns will be even more important as children grow older and are expected to be awake and alert during school hours; getting enough sleep on a regular basis and coming to school well-rested will help grade-school children’s academic performance and their social behavior as well. Keeping screens out of the bedroom (and turned off during the hours before bed) becomes more and more important as children grow — and it’s not a bad habit for adults, either. Even when education went remote during the pandemic, keeping children’s sleep schedules regular helped them stay on course.

Keeping screens out of the bedroom (and turned off during the hours before bed) becomes more and more important as children grow — and it’s not a bad habit for adults, either. Even when education went remote during the pandemic, keeping children’s sleep schedules regular helped them stay on course.

As your child hits adolescence, her body clock will shift so that she is “programmed” to stay up later and sleep later, often just as schools are demanding early starts. Again, good family “sleep hygiene,” especially around screens at bedtime, in the bedroom, and even in the bed, can help teenagers disconnect and get the sleep they need. By taking sleep seriously, as a vital component of health and happiness, parents are sending an important message to children at every age.

More About Sleep and Your Child

How to Feed Your Child

There’s nothing more basic to parenting than the act of feeding your child. But even while breast-feeding, there are decisions to be made. (Yes, breast-feeding mothers should eat spicy food if they like it. No, they shouldn’t respond to all infant distress by nursing.) Pediatricians currently recommend exclusive breast-feeding for the first six months, and then continuing to breast-feed as you introduce a range of solid foods. Breast-feeding mothers deserve support and consideration in society in general and in the workplace in particular, and they don’t always get it. And conversely, mothers are sometimes made to feel inadequate if breast-feeding is difficult, or if they can’t live up to those recommendations.

(Yes, breast-feeding mothers should eat spicy food if they like it. No, they shouldn’t respond to all infant distress by nursing.) Pediatricians currently recommend exclusive breast-feeding for the first six months, and then continuing to breast-feed as you introduce a range of solid foods. Breast-feeding mothers deserve support and consideration in society in general and in the workplace in particular, and they don’t always get it. And conversely, mothers are sometimes made to feel inadequate if breast-feeding is difficult, or if they can’t live up to those recommendations.

You have to do what works for you and your family, and if exclusive breast-feeding doesn’t, any amount that you can do is good for your baby. As children grow, the choices and decisions multiply; that first year of eating solid foods, from 6 to 18 months, can actually be a great time to give children a range of foods to taste and try, and by offering repeated tastes, you may find that children expand their ranges.

Small children vary tremendously in how they eat; some are voracious and omnivorous, and others are highly picky and can be very difficult to feed. Let her feed herself as soon as and as much as possible; by “playing” with her food she’ll learn about texture, taste and independence. Build in the social aspects of eating from the beginning, so that children grow up thinking of food in the context of family time, and watching other family members eat a variety of healthy foods, while talking and spending time together. (Children should not be eating while looking at screens.) Parents worry about picky eaters, and of course about children who eat too much and gain weight too fast; you want to help your child eat a variety of real foods, rather than processed snacks, to eat at mealtimes and snacktimes, rather than constant "grazing," or "sipping," and to eat to satisfy hunger, rather than experiencing food as either a reward or a punishment.

Don’t cook special meals for a picky child, but don’t make a regular battlefield out of mealtime.

Some tips to try:

- Talk with small children about "eating the rainbow," and getting lots of different colors onto their plates (orange squash, red peppers, yellow corn, green anything, and so on).

- Take them to the grocery store or the farmer's market and let them pick out something new they'd like to try.

- Let them help prepare food.

- Be open to deploying the foods they enjoy in new ways (peanut butter on almost anything, tomato sauce on spinach).

- Some children will eat almost anything if it's in a dumpling, or on top of pasta.

- Offer tastes of what everyone else is eating.

- Find some reliable fallback alternatives when your child won’t eat anything that’s offered. (Many restaurants will prepare something simple off the menu for a child, such as plain pasta or rice.)

Above all, encourage your child to keep tasting; don't rule anything out after just a couple of tries. And if you do have a child who loves one particular green vegetable, it's fine to have that one turn up over and over again.

Bottom line: As long as a child is growing, don’t agonize too much.

Family meals matter to older children as well, even as they experience the biological shifts of adolescent growth. Keep that social context for food as much as you can, even through the scheduling complexities of middle school and high school. Keep the family table a no-screen zone, and keep on talking and eating together. Some families found that the pandemic meant more opportunities for family meals, which helped them through the hard times, but if the stresses of the recent past have pushed your family toward more snacking and more fast food, know that you are not alone. It will always help to re-set as a family, to stock healthy foods in the house, and to eat together and connect over food.

More on Your Child's Diet

How to Discipline

Small children are essentially uncivilized, and part of the job of parenting inevitably involves a certain amount of correctional work. With toddlers, you need to be patient and consistent, which is another way of saying you will need to express and enforce the same rules over and over and over again. “Time outs” work very effectively with some children, and parents should watch for those moments when they (the parents) may need them as well. Seriously, take a breather when you are feeling as out of control as your child is acting. Many parents have been under extraordinary stress during the pandemic; be sure you are taking care of yourself, and get help if you need it.

With toddlers, you need to be patient and consistent, which is another way of saying you will need to express and enforce the same rules over and over and over again. “Time outs” work very effectively with some children, and parents should watch for those moments when they (the parents) may need them as well. Seriously, take a breather when you are feeling as out of control as your child is acting. Many parents have been under extraordinary stress during the pandemic; be sure you are taking care of yourself, and get help if you need it.

Distraction is another good technique; you don’t have to win a moral victory every time a small child misbehaves if you can redirect the behavior and avoid the battle. The overall disciplinary message to young children is the message that you don’t like the behavior, but you do love the child.

Think praise rather than punishment. Physical discipline, like hitting and spanking, tends to produce aggressive behavior in children. Keep in mind that it’s always a parental win if you can structure a situation so that a child is earning privileges (screentime, for example) by good behavior, rather than losing them as a penalty. Search for positive behaviors to praise and reward, and young children will want to repeat the experience. But inevitably, parenthood involves a certain number of “bad cop” moments, when you have to say no or stop and your child will be angry at you — and that’s fine, it goes with the territory. Look in the mirror and practice saying what parents have always said: “I’m your mother/father, I’m not your friend.”

Keep in mind that it’s always a parental win if you can structure a situation so that a child is earning privileges (screentime, for example) by good behavior, rather than losing them as a penalty. Search for positive behaviors to praise and reward, and young children will want to repeat the experience. But inevitably, parenthood involves a certain number of “bad cop” moments, when you have to say no or stop and your child will be angry at you — and that’s fine, it goes with the territory. Look in the mirror and practice saying what parents have always said: “I’m your mother/father, I’m not your friend.”

As parents, we should be trying to regulate our children’s behavior — or to help them regulate their own — and not trying to legislate their thoughts:

- It is OK to dislike your brother or your classmate, but not to hit him.

- It is OK to feel angry or frustrated, as long as you behave properly.

Our “civilizing” job as parents may be easier, in fact, if we acknowledge the strength of those difficult emotions, and celebrate the child who achieves control. And take advantage of the opportunity to demonstrate what you do when you have lost control or behaved badly: Offer a sincere parental apology.

And take advantage of the opportunity to demonstrate what you do when you have lost control or behaved badly: Offer a sincere parental apology.

It’s also worth recognizing that we have all been living through extraordinary times, and that a child who is, for example, angry or frustrated because activities have been canceled, or interrupted, should not feel bad about expressing those emotions. Even young children can understand that what’s “wrong” or “bad” is the pandemic – not the child’s feelings.

More on Discipline

Social Issues

Parenting in the Time of Covid

This is an anxious time to be a parent. You’re helping children navigate a pandemic world in which new information – sometimes scary, sometimes confusing – has to be absorbed and reacted to on a regular basis. You may be helping an anxious child handle fears about going out into the world, or trying to enforce safety protocols with a child who is just eager to declare the pandemic “over. ” You may be dealing with economic pressures, with worries over vulnerable family members, or with grief for people who have been lost. And many of the everyday decisions of parenthood have become more heavily weighted and more frightening. It can’t be said too often: understand that you are living – and parenting – through very difficult times, and as far as possible, take care of yourself.

” You may be dealing with economic pressures, with worries over vulnerable family members, or with grief for people who have been lost. And many of the everyday decisions of parenthood have become more heavily weighted and more frightening. It can’t be said too often: understand that you are living – and parenting – through very difficult times, and as far as possible, take care of yourself.

If you are anxious, if you are depressed, if you are angry, think about the coping strategies that help you, and look for additional help if you need it, from your partner, if you have one, from close friends and family, from your spiritual community, from your doctor, from a mental health professional. Understand that parents have faced a difficult – and at times impossible – set of “assignments,” and that they have in large part responded with everyday heroism in taking care of their children. But they need to care of themselves as well.

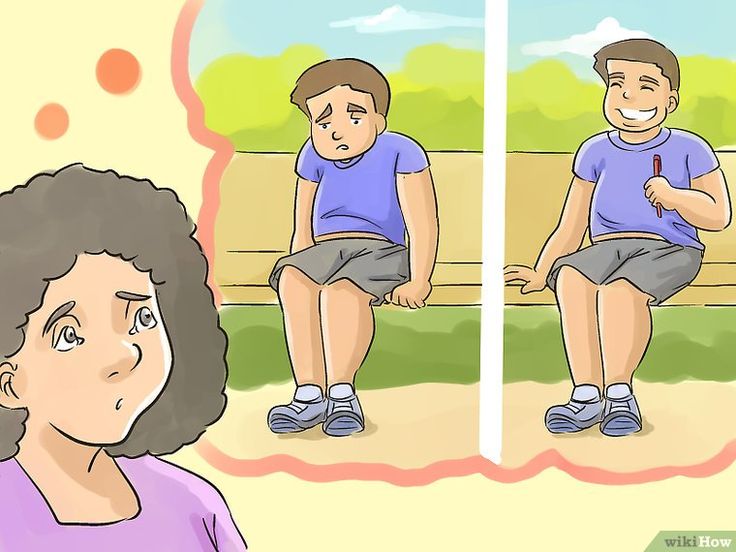

Bullying

You can take steps to help your children manage both bullying and conflict — and you're at your most useful when you know which of the two you’re trying to address. Children who are being bullied are on the receiving end of mistreatment, and are helpless to defend themselves, whereas children in conflict are having a hard time getting along. Fortunately, most of the friction that happens among children is in the realm of conflict —an inevitable, if unpleasant, consequence of being with others — not bullying.

Children who are being bullied are on the receiving end of mistreatment, and are helpless to defend themselves, whereas children in conflict are having a hard time getting along. Fortunately, most of the friction that happens among children is in the realm of conflict —an inevitable, if unpleasant, consequence of being with others — not bullying.

If children are being bullied, it’s important to reassure them that they deserve support, and that they should alert an adult to what’s happening. Further, you can remind your children that they cannot passively stand by if another child is being bullied. Regardless of how your own child might feel about the one being targeted, you can set the expectation that he or she will do at least one of three things: confront the bully, keep company with the victim, alert an adult.

When the issue is conflict, you should aim to help young people handle it well by learning to stand up for themselves without stepping on anyone else. To do this, you can model assertion, not aggression, in the inevitable disagreements that arise in family life, and coach your children to do the same as they learn how to address garden-variety disputes with their peers.

To do this, you can model assertion, not aggression, in the inevitable disagreements that arise in family life, and coach your children to do the same as they learn how to address garden-variety disputes with their peers.

More About Gender

Morality

All parents have in common the wish to raise children who are good people. You surely care about how your child will treat others, and how he or she will act in the world. In some households, regular participation in a religious institution sets aside time for the family to reflect on its values and lets parents convey to their children that those beliefs are held by members of a broad community that extends beyond their home.

Even in the absence of strong spiritual beliefs, the celebration of religious holidays can act as a key thread in the fabric of family life. Though it is universally true that children benefit when their parents provide both structure and warmth, even the most diligent parents can struggle to achieve both of these on a regular basis. The rituals and traditions that are part of many religious traditions can bring families together in reliable and memorable ways. Of course, there are everyday opportunities to instill your values in your child outside of organized religion, including helping an elderly neighbor or taking your children with you to volunteer for causes that are important to you.

The rituals and traditions that are part of many religious traditions can bring families together in reliable and memorable ways. Of course, there are everyday opportunities to instill your values in your child outside of organized religion, including helping an elderly neighbor or taking your children with you to volunteer for causes that are important to you.

Above all, however, children learn your values by watching how you live.

More on Morality and Children

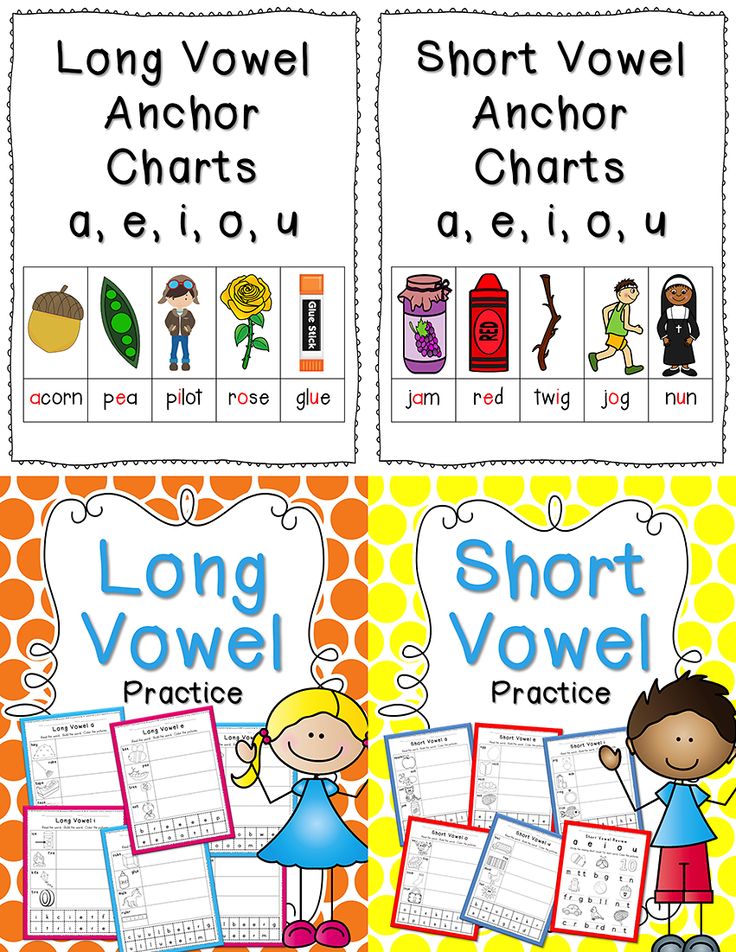

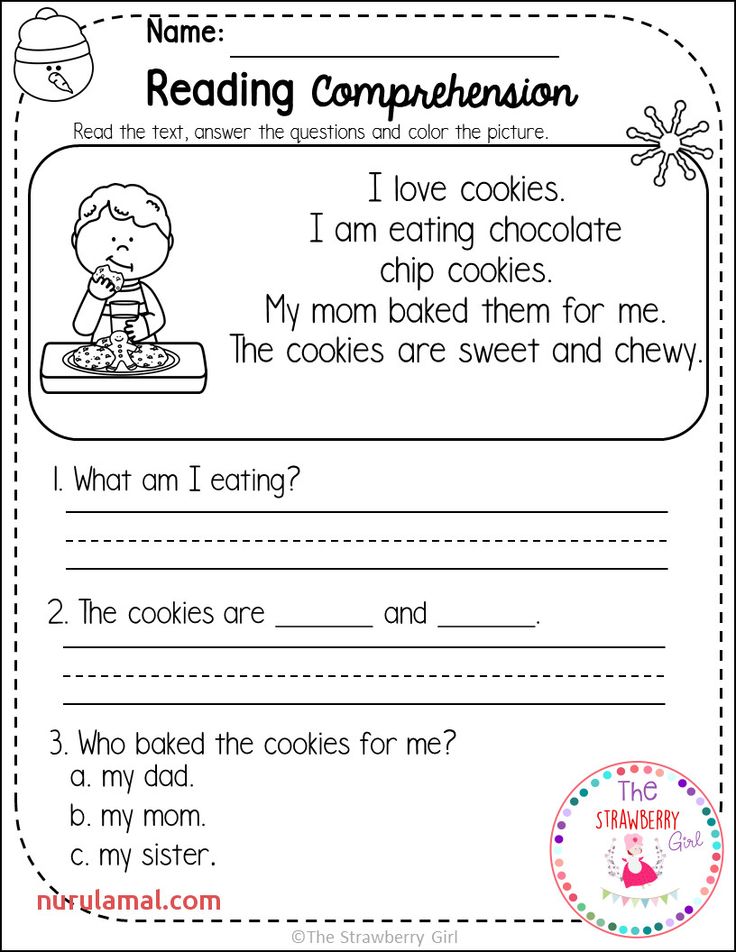

Academic Pressure

When it comes to school, parents walk a difficult line: You want your children to strive and succeed, but you don’t want to push them in ways that are unfair, or cause needless stress. At every age and skill level, children benefit when parents help them focus on improving their abilities, rather than on proving them. In other words, children should understand that their intellectual endowment only gets them started, and that their capabilities can be increased with effort.

Many children struggled during the course of the pandemic, faced with learning in ways that were harder for them than regular school – this may be especially true for children with learning differences and special needs, but it applies across the board. As they return to in-person schooling, children need time to catch up, and they need to feel comfortable asking for that time, or for extra help – so they need to hear the message that what matters is the learning and understanding that they gain, not some rigid schedule that they may have fallen behind.

Children who adopt this growth mindset – the psychological terminology for the belief that industry is the path to mastery – are less stressed than peers who believe their capacities are fixed, and outperform them academically. Students with a growth mindset welcome feedback, are motivated by difficult work, and are inspired by the achievements of their talented classmates.

To raise growth-mindset thinkers you can make a point of celebrating effort, not smarts, as children navigate school. (This may be more important than ever as schools reopen and children return following their different experiences with remote or hybrid education.) When they succeed, say, “Your hard work and persistence really paid off. Well done!” And when they struggle, say, “That test grade reflects what you knew about the material being tested on the day you took the test. It does not tell us how far you can go in that subject. Stick with it and keep asking questions. It will come.”

(This may be more important than ever as schools reopen and children return following their different experiences with remote or hybrid education.) When they succeed, say, “Your hard work and persistence really paid off. Well done!” And when they struggle, say, “That test grade reflects what you knew about the material being tested on the day you took the test. It does not tell us how far you can go in that subject. Stick with it and keep asking questions. It will come.”

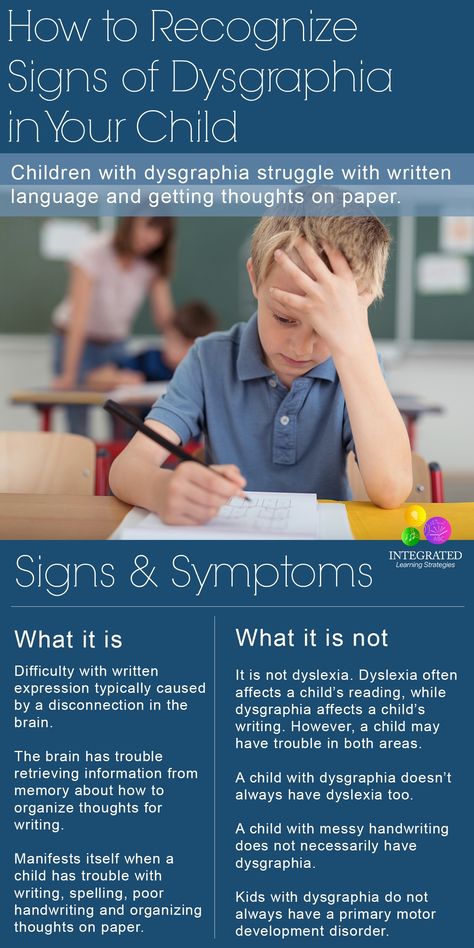

Parents should step in when students face academic challenges that cause constant or undue stress. Some students hold themselves, or are held by adults, to unrealistic standards. Others missed a step along the way, had a hard time during the pandemic, study ineffectively or are grappling with an undiagnosed learning difference. Parents should be in touch with teachers about how things are going. Determining the nature of the problem will point the way to the most helpful solution.

More on Children and School Pressure

Technology

Here’s how to raise a child with a healthy attitude toward shiny screens and flashing buttons.

Screen Time

You could try to raise a screen-free child, but let’s be honest, you’re reading this on a screen. As in everything else, the challenge is in balancing the ideal and the real in a way that’s right for your family. The pandemic upended many families’ rules and practices, as everything from visits with grandma from teenage social networks to math class started to happen on screens. And some aspects of those experiences may help you think about positive screen-related experiences you want to build into your children’s lives going forward: regular dates for watching a movie as a family, reading a book on an iPad, FaceTiming with out-of-town relatives. Technology plays such an important role in children’s lives now that when we talk about it, we’re talking about everything from sleep to study to social life.

“Technology is just a tool and it can be an extremely enriching part of kids’ lives,” said Scott Steinberg, co-author of “The Modern Parent’s Guide to Facebook and Social Networks. ” “A lot of what we’re teaching about parenting around technology is just basic parenting,” he said. “It comes down to the Golden Rule: Are they treating others in a respectful and empathetic manner?”

” “A lot of what we’re teaching about parenting around technology is just basic parenting,” he said. “It comes down to the Golden Rule: Are they treating others in a respectful and empathetic manner?”

Phones and social media give older kids opportunities to reckon with responsibilities they haven’t had before, such as being sent, or asked to share, an inappropriate image, said Ana Homayoun, author of the book “Social Media Wellness: Helping Teens and Tweens Thrive in an Unbalanced Digital World.” Parents need to keep talking about this side of life with their children so they don’t leave their kids to navigate it alone.

And then there’s the question of protecting family time. Mr. Steinberg advises setting household rules that govern when devices may be used, and have clear, age-appropriate policies so kids know what they can and can’t do.

Some of these policies will be appropriate for all ages, including parents, such as:

- No phones at the dinner table.

- No screens for an hour before bedtime.

It’s important to practice what you preach. And if your family needs to re-set some of these rules as children return to the classroom, you can talk it through with your children, explaining why it matters to use devices well, but set some limits. And in addition to taking time for family meals and family conversations, parents should be taking the time to sit down with young children and look at what they’re doing online, rather than leaving them alone with their devices as babysitters.

Parents as Digital Role Models

When a parent wants to post on social media about something a child did that may embarrass the child, Ms. Homayoun said, it’s worth stepping back to consider why. Are you posting it to draw attention to yourself?

You should respect your child’s privacy as much as you respect the privacy of friends, family members and colleagues. As cute as it may seem to post pictures of a naked toddler, consider a "no butts" policy. That may not be the image that your child wants to portray 15 years from now.

“We need to, from a very early age, teach kids what consent looks like,” Ms. Homayoun said. “It doesn’t begin when a kid is 15, 16 or 17. It begins when a kid is 3 and he doesn’t want to go hug his uncle.” Or when he doesn’t want you to post that video of him crying over a lost toy.

Our children will create digital footprints as they grow, and it will be one of our jobs to help them, guide them and get them to think about how something might look a few years down the line — you can start by respecting their privacy and applying the same standards throughout their lives.

Tech Toys

It’s easy to dismiss high-tech toys as just pricey bells and whistles, but if you choose more enriching options, you can find toys that help kids grow. For young children, though, there’s a great deal to be said for allowing them, as much as possible, to explore the nondigital versions of blocks, puzzles, fingerpaints and all the rest of the toys that offer tactile and fine motor experiences. As children get older, some high-tech games encourage thinking dynamically, problem solving and creative expression.

As children get older, some high-tech games encourage thinking dynamically, problem solving and creative expression.

“These high-tech games can be an opportunity to bond with your kids. Learn more about how they think and their interests,” Mr. Steinberg said. Some games encourage kids to be part of a team, or lead one. And others let them be wilder than they might be in real life – in ways that parents can appreciate: “You can’t always throw globs of paint around the house but you can in the digital world,” he said.

The Right Age for a Phone?

“Many experts would say it’s about 13, but the more practical answer is when they need one: when they’re outside your direct supervision,” Mr. Steinberg said. Ms. Homayoun recommends them for specific contexts, such as for a child who may be traveling between two houses and navigating late sports practices.

Consider giving tiered access to technology, such as starting with a flip phone, and remind children that privileges and responsibilities go hand in hand. A child’s expanding access to personal technology should depend on its appropriate use.

A child’s expanding access to personal technology should depend on its appropriate use.

To put these ideas into practical form, the website of the American Academy of Pediatrics offers guidelines for creating a personalized family media use plan.

More on Technology and Kids

Time Management

Balance both your schedule and your child’s with a reasonable approach to time.

Overscheduling

As the world opens up, children whose lives had been more circumscribed will have the chance not only to return to school, but also to get back to sports, lessons and extracurricular activities. At the same time, pandemic protocols can make all of this even more complicated, for kids and for parents. We all know the cliché of the overscheduled child, rushing from athletic activity to music lessons to tutoring, and there will probably be moments when you will feel like that parent, with a carload of equipment and a schedule so complicated that you wake up in the middle of the night worrying you’re going to lose track. But it’s also a joy and a pleasure to watch children discover the activities they really enjoy, and it’s one of the privileges of parenthood to cheer your children on as their skills improve.

But it’s also a joy and a pleasure to watch children discover the activities they really enjoy, and it’s one of the privileges of parenthood to cheer your children on as their skills improve.

Some children really do thrive on what would be, for others, extreme overscheduling. But the complexities of managing social contacts in a time of Covid protocols make it even more important to set priorities so that a child gets to do whichever activities really matter to that particular kid. Know your child, talk to your child, and when necessary, help your child negotiate the decisions that make it possible to keep doing the things that mean the most, even if that means letting go of some other activities.

Remember, children can get a tremendous amount of pleasure, and also great value, from learning music, from playing sports, and also from participating in the array of extracurricular activities that many schools offer. However, they also need a certain amount of unscheduled time. The exact mix varies from child to child, and even from year to year. On the one hand, we need to help our children understand the importance of keeping the commitments they make — you don’t get to give up playing your instrument because you’re struggling to learn a hard piece; you don’t quit the team because you’re not one of the starters — and on the other, we need to help them decide when it’s time to change direction or just plain let something go.

The exact mix varies from child to child, and even from year to year. On the one hand, we need to help our children understand the importance of keeping the commitments they make — you don’t get to give up playing your instrument because you’re struggling to learn a hard piece; you don’t quit the team because you’re not one of the starters — and on the other, we need to help them decide when it’s time to change direction or just plain let something go.

So how do you know how much is too much? Rethink the schedule if:

- Your child isn’t getting enough sleep.

- Your child doesn’t have enough time to get schoolwork done.

- Your child can’t squeeze in silly time with friends, or even a little downtime to kick around with family.

And make sure that high school students get a positive message about choosing the activities that they love, rather than an anxiety-producing message about choosing some perfect mix to impress college admissions officers. The point of scheduling is to help us fit in the things we need to do and also the things we love to do; overscheduling means that we’re not in shape to do either.

The point of scheduling is to help us fit in the things we need to do and also the things we love to do; overscheduling means that we’re not in shape to do either.

Taking Care of Yourself

Being a parent is the job of your life, the job of your heart, and the job that transforms you forever. But as we do it, we need to keep hold of the passions and pastimes that make us who we are, and which helped bring us to the place in our lives where we were ready to have children. We owe our children attention — and nowadays it’s probably worth reminding ourselves that paying real attention to our children means limiting our own screentime and making sure that we’re talking and reading aloud and playing. But we owe ourselves attention as well, and this has been an extraordinarily stressful and anxious time for many parents.

Your children will absolutely remember the time that you spent with them, and that has special meaning for many families after the ways the lockdowns and isolation months of the recent past — but you also want them to grow up noticing the way you maintain friendships of your own, the way you put time and energy into the things that matter most to you, from your work to your physical well-being to the special interests and passions that make you the person they know. They will see how you hold on to what matters most, and how you make sure to do it safely – the same imperatives you’re trying to get them to incorporate in their own lives. Whether you’re taking time to paint or dance, or to knit with friends, or to try to save the world, you are acting and living your values and your loves, and those are messages that you owe to your children.

They will see how you hold on to what matters most, and how you make sure to do it safely – the same imperatives you’re trying to get them to incorporate in their own lives. Whether you’re taking time to paint or dance, or to knit with friends, or to try to save the world, you are acting and living your values and your loves, and those are messages that you owe to your children.

You may not be able to pursue any of your passions in quite the same way and to quite the same extent that you might have before you had a child — and before every social interaction carried a Covid question. You may have to negotiate the time, hour by hour, acknowledging what is most important, and trading it, perhaps, for what is most important to your partner, if you have one. You’ll be, by definition, a different painter, as you would be a different runner, a different dancer, a different friend and a different world-saver. But you may well come to realize that the experience of taking care of a small child helps you concentrate in a stronger, almost fiercer way, when you get that precious hour to yourself.

How to Find Balance

As children return to in-person learning, the distinction between schoolwork and homework will become an issue for some. Lots of parents worry that their children get an unreasonable amount of homework, and that homework can start unreasonably young. While it may be easy to advise that homework can help a child learn time management and study habits, and to let children try themselves and sometimes fail, the reality is that many of us find ourselves supervising at least a little, and parents who have been supervising remote learning may find it harder to pull back and let the child work. This is another reason to be in touch with your child’s teacher, and aware of how things are going in school. You should speak up if it seems that one particular teacher isn’t following the school’s guidelines for appropriate amounts of homework. And for many children, it’s helpful to talk through the stages of big projects and important assignments, so they can get some intermediate dates on the calendar. If the homework struggle dominates your home life, it may be a sign of another issue, like a learning disability.

If the homework struggle dominates your home life, it may be a sign of another issue, like a learning disability.

For many families nowadays, the single biggest negotiation about time management is around screen time, and of course, screen time has now become part of schoolwork for many children. Screen time can be homework time (but is the chatting that goes on in a corner really part of the assignment?) or social time or pure entertainment time. Bottom line: As long as a child is doing decently in school, you probably shouldn’t worry too much about whether, by your standards, the homework looks like it is being done with too many distractions.

And remember, some family responsibilities can help anchor a child to the nonvirtual world: a dog to be walked or trash to be taken out. And when it comes to fun, let your child see that you value the non-homework part of the evening, or the weekend, that you understand that time with friends is important, and that you want to be kept up to date on what’s going on, and to talk about your own life. Ultimately, we have to practice what we preach, from putting down our own work to enjoy unstructured family time to putting down our phones at the dinner table to engage in a family discussion. Our children are listening to what we say, and watching what we do.

Ultimately, we have to practice what we preach, from putting down our own work to enjoy unstructured family time to putting down our phones at the dinner table to engage in a family discussion. Our children are listening to what we say, and watching what we do.

How to Talk to Children in Preschool Through 4th Grade

Kids: They’re just like us. Except, you know, not really—they’re shorter and cuter, and they’re working through complex developmental processes—cognitive, emotional, and social—that determine both who they are today and who they will eventually become.

As Mo Willems—a kid celebrity if there ever was one—reminded me, “Childhood is an inherently difficult time.” Kids are new to the world, and they have very little control over what happens in their lives. To make matters worse, as a 4-year-old friend told me, a lot of grown-ups—even teachers—aren’t very good at talking to kids. When I interviewed her recently, she shared that, much too often, they just tell kids what to do and don’t even ask questions. “They don’t say, ‘Hi, how are you doing?’” she said, shaking her head. “They don’t say, like, ‘Who are the people in your family?’” Sometimes, she added, even when grown-ups do try making conversation with kids, they use voices that are too loud, or they come on a little too strong. An 8-year-old friend of mine echoed that last point: “It’s good for adults to be funny—but not too funny,” she told me.

“They don’t say, ‘Hi, how are you doing?’” she said, shaking her head. “They don’t say, like, ‘Who are the people in your family?’” Sometimes, she added, even when grown-ups do try making conversation with kids, they use voices that are too loud, or they come on a little too strong. An 8-year-old friend of mine echoed that last point: “It’s good for adults to be funny—but not too funny,” she told me.

So, how should teachers approach talking to children? Thinking through my own experience with children, which includes training and work as an elementary school teacher, and consulting a few experts—the traditional kind, as well as a few very thoughtful friends who haven’t yet celebrated double-digit birthdays—I’ve collected a few insights and tricks for talking to kids ages 4ish to 10ish.

Take Time to Understand Where They Are Developmentally

When it comes to addressing how adults misunderstand little kids, Erika Christakis, the author of The Importance of Being Little, articulates a fundamental irony: “I think we have a mismatch problem, where we both underestimate and overestimate children,” she told The Atlantic in 2016, explaining that when kids are provided with developmentally appropriate conditions, for example, they do not—contrary to popular belief—have short attention spans. At the same time, kids can’t follow rapidly changing adult schedules, or be expected to put themselves in others’ shoes.

At the same time, kids can’t follow rapidly changing adult schedules, or be expected to put themselves in others’ shoes.

When I interviewed Christakis in 2019, she called the unwillingness to consider the child’s perspective “adultification,” and she attributes many obstacles that children face in American society, such as packed schedules and insufficient appreciation for the importance of unstructured play, to this tendency.

Nancy Close, a child psychologist and assistant professor at the Yale Child Study Center, says that, though all children are different, younger children tend to be more egocentric—“either they are impacting something or something is impacting them”—and that the older a child is, the more able she likely is to be able to “hold another’s point of view with much more flexibility.” (For a thorough overview of typical stages of child development, the book Yardsticks, by Chip Wood, is a great resource.)

When talking with a child, adults should be aware of how that child situates herself in the world, and frame the interaction accordingly. For instance, a teacher who is touching base with two children who are in conflict should be aware of their developmental needs: Kindergartners might respond well to direct questions about how they feel, while fourth graders would likely be better able to share their thoughts on rule systems that are equitable for all.

For instance, a teacher who is touching base with two children who are in conflict should be aware of their developmental needs: Kindergartners might respond well to direct questions about how they feel, while fourth graders would likely be better able to share their thoughts on rule systems that are equitable for all.

Take Them Seriously—and Never Condescend

Kids are brilliant at picking up on tone and subtext; it’s an evolutionary necessity. Just as you’d never use a condescending tone of voice or baby talk in a classroom, react seriously to what the kids you’re talking to are saying. Keep in mind that even little kids can think about very big topics and consider them with great seriousness. Don’t introduce things that are scary—debates on nuclear disarmament can wait a few years—but don’t feel the need to stick to sunshine and lollipops either.

Seth Aronson, a psychologist and professor at the William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis, and Psychology in New York City, suggests that adults let children guide conversations about emotional or heavy topics—and that the first step to navigating potentially tricky conversations is that adults should be able to tolerate their own anxieties around talking about those topics with kids. Again, all kids are different: Let the child in front of you determine the content and register of your conversation.

Again, all kids are different: Let the child in front of you determine the content and register of your conversation.

As you’re talking, don’t rush to fill in silences—doing so can heighten kids’ anxiety. Phrases that you’d use with an adult conversation partner—“I agree,” “I see what you mean,” “Say more”—go a long way not only in furthering the content of a conversation but in helping kids feel respected and heard.

Listen for the Subtext

Children often don’t have the linguistic or emotional tools to say what they really mean. Fred Rogers had an anecdote he liked to tell: Soon after he entered a preschool classroom, a little boy informed him that his teddy bear’s ear had come off in the wash. Rogers realized that the boy wasn’t relaying a simple incident—rather, he was conveying his concern that something similar might happen to him. As soon as Rogers told the children present that it wasn’t possible for humans to lose body parts while taking a bath, all of them visibly relaxed.

While it’s important to pay close attention to what children are saying, or trying to say, it’s also imperative to take stock of their nonverbal communication. Close, the child psychologist, recommends that if a child is crossing his arms or pouting, for instance, you express your genuine reactions to his body language. “You might say, ‘You just said you’re excited, but it doesn’t really look like you’re feeling that,” Close said.

Give Compliments That Are Meaningful, Specific, and True—or Could Be True One Day

Children want to know that their efforts are recognized by adults. Compliment them on things they do (“I can tell you’ve been working hard on your drawing skills”) or mirror back the qualities you know they’d like to see in themselves (“It’s so great that you’re such a supportive friend”). Even if a child is not characteristically a hard worker, you can encourage them to work hard by framing their efforts in this way.

Be as specific as possible, and avoid praising the superficial (like physical appearance) or things over which they have no control (“Wow, you have such a big family!”).

Share of Yourself

Kids love learning about the world of grown-ups, so it’s helpful to let them in on topics they might relate to. Did you try a new breakfast cereal? Feeling excited about a new friend you made? Looking forward to watching a funny movie with your brother? Tell them about it—and be specific.

Rather than simply mention that you used to take dance classes when you were in fourth grade, for instance, tell them all about your ridiculous dance teacher, and the time your friend Stacy, who was always trying to get the other kids to laugh, pretended to burp loudly in the middle of practice. Kids like stories they can relate to—and good stories are made of good details.

Get on Their Level—Literally

Doesn’t it feel weird to talk to someone who towers over you? In my experience, it feels disconcerting, or even threatening—especially if the big person has a loud, booming voice.

When you’re talking to little kids, scooch down. Putting yourself on an equal footing physically can help create a comparable psychological effect—the kid is partaking in a conversation, not listening to a lecture. And when you talk, match their volume—as my 4-year-old friend put it, “Don’t be loud”—and use a tone of voice that’s gentle but natural, like you’re talking to an extremely interesting, highly intelligent person (because you are).

And when you talk, match their volume—as my 4-year-old friend put it, “Don’t be loud”—and use a tone of voice that’s gentle but natural, like you’re talking to an extremely interesting, highly intelligent person (because you are).

Use Tried-and-True Topics and Tactics

Every child in my life knows a lot about my very silly cat, Tabitha. Pets are a great go-to topic for almost every kid—as are favorites (colors, animals, songs) and things that are gross. And then there are the tactics kids love: when you let them in on a secret (“Hardly any kid knows this!”) or a joke (a wink will do), seek their expertise, or ask for their advice.

When I taught second grade, at the beginning of the day my students and I would share challenges we were encountering in our lives and give each other suggestions. I’m not at all ashamed to say that many of my most pressing challenges—how to motivate myself to fold laundry, how to go to bed earlier, and what to do when I kept forgetting my winter gloves at home—were solved by some very thoughtful 7-year-olds.

By and large, kids want to interact with people who want to interact with them, so relish the opportunity to talk with someone who undoubtedly sees the world quite differently than you do.

"How can a child communicate with a stranger? No way." Basic safety rules for children

One of the most powerful and terrible fears of parents is the kidnapping of a child by a criminal. Since the Middle Ages, attempts to prevent the terrible came down to intimidating children. The phrase "the uncle will come, put him in a bag and take away (eat, kill)" is still very common today. Its usefulness and effectiveness is doubtful: the child imagines a terrible person who can grab him in the middle of the street, while not understanding that pedophiles in life do not look dangerous, they try to win over children, rub their trust in them, try to make friends before To commit a crime.

We talked with child psychiatrist Artem Novikov and the founder and head of the LizaAlert school Polina Pavlyukova about what information should be conveyed to a child at different ages, how to answer uncomfortable children's questions, and about the need for sex education in the family and school and building trusting, warm relationships between parents and children.

How to tell young children about the danger of pedophiles?

There is no need to focus the conversation on describing pedophiles and their actions - for a small child, such information is redundant, it can be traumatic. But to give information that can help him, to talk from a very early age about personal boundaries and the inner circle of people who can be trusted is necessary.

"The problem should be approached comprehensively, when you see a news report about a pedophile, you shouldn't go to a child and say: 'You know, there are such people'," explains child psychiatrist Artem Novikov. "The main weapon against sexual crimes is sex education children. From the age of three you need to devote time to him. "

At the same time, the doctor emphasizes: the sexual education of babies is not about condoms or sex, but about what is unacceptable in relation to a child.

© Aleksey Durasov/TASS

"We tell the child about the intimate areas, while speaking about the genitals, you need to call them by their proper names, and not replace them with the children's words "krantik" or "cookie". Because they can then use it people with bad intentions. For each age, of course, you need to adapt the information, adding it as the child grows up. We will definitely introduce the concept of "forbidden zones", that is, we are talking about the "panty zone", zones that underwear covers. We explain that no one can touch these areas, except for the parents during washing, if it is a small child, or a doctor who examines the child in the presence of a parent.0007

Because they can then use it people with bad intentions. For each age, of course, you need to adapt the information, adding it as the child grows up. We will definitely introduce the concept of "forbidden zones", that is, we are talking about the "panty zone", zones that underwear covers. We explain that no one can touch these areas, except for the parents during washing, if it is a small child, or a doctor who examines the child in the presence of a parent.0007

We explain the rules of contact with other people, what is considered acceptable and what is not, we talk about bad, wrong, and acceptable touching. It is important to explain that violence can be more than just physical contact, it can be jokes, talking, being forced to watch videos or photos.

We are introducing a flag system. We explain that if one of the adults discusses with you the genitals - this is an orange flag, if it touches your intimate areas or yours in front of you - this is a red flag and that you need to immediately tell your mother or an adult you trust about this. By discussing such things, we are laying the foundation of trust so that later, if a trouble or trouble happens to him, he will come to us and tell about his problems. We must be prepared that the child may come and ask questions and that they will have to look for answers. "

By discussing such things, we are laying the foundation of trust so that later, if a trouble or trouble happens to him, he will come to us and tell about his problems. We must be prepared that the child may come and ask questions and that they will have to look for answers. "

Artem Novikov notes that if parents taboo such topics, they always lose. Interest in intimate life sometimes wakes up in a child earlier than adults think, and an "uncle" or "aunt" with bad intentions can take advantage of this.

What rules of interaction with adults should a child learn?

“Any stranger is a danger to a child,” says Polina Pavlyukova, head of the LizaAlert school. “You can’t scare children by telling scary stories. It’s important to give a behavioral algorithm. How to communicate with a stranger who wants to communicate with a child? The correct answer is: no way".

© Aleksey Durasov / TASS

It is important to clarify in a conversation that an adult will never turn to a child for help, he will also never give him gifts, invite him to ride in a car, play toys without first asking permission from his parents in the presence of a child. It doesn't matter if it's an acquaintance - a neighbor, a teacher, a coach at a sports school, or a stranger. This rule is inviolable for any adult. If he violates it, this is a signal of danger.

It doesn't matter if it's an acquaintance - a neighbor, a teacher, a coach at a sports school, or a stranger. This rule is inviolable for any adult. If he violates it, this is a signal of danger.

Is it necessary to train, play dangerous situations with a child?

With the permission of their parents, the LizaAlert search squad conducted an experiment: employees of the squad approached the children in public places and persuaded them to leave with them under various pretexts. Nine out of ten children agreed, despite parental warnings not to interact with strangers.

Polina Pavlyukova says that even adults get lost in a stressful situation, so just warning a child about the danger is not enough. You can work out different situations in the game without focusing only on the kidnapping. For example, first talk about how to act if there is a fire at home or if an electrical appliance catches fire. Then - about how to behave if lost on the street. And also - what to do if an adult came up and spoke.

© Aleksey Durasov/TASS

"You need to play different situations: what will you do if a stranger comes up to you and offers you a toy? What if a kitten?" - says Polina Pavlyukova.

It is also important to work out the situation when a child is informed that parents, brother, sister, grandmother are in trouble (accident, hospital) and are asked to come urgently. Everything again comes down to the rule: an adult will never take a child that is not his own anywhere if his parent is not around. If something happens to the parents, the child will definitely not be taken to the hospital, they will not be taken away from school, from the yard, but adult relatives will be informed about it.

Child psychiatrist Artem Novikov believes that such conversations should be woven into everyday life so that the child learns the rules and does not forget them, even if he gets scared or gets carried away.

"You can't just set dates and talk to a child at four, six, eight years old about this topic," says Artem Novikov. "It's a constant job."

"It's a constant job."

How should a child act if they are called with them or they try to take them away by force?

Another terrible fact that psychologists note is that children do not scream when they feel danger. This happens not only because they are scared, but also because they are taught from the cradle to be obedient, not to argue with adults, to behave quietly, decently, not to make noise. Parents should explain to their children that the rules of decency are canceled when a person violates personal boundaries and represents a danger. And that some adults can be bad, and you don’t need to obey them.

"To teach a child to scream, you can go to a deserted place, for example, to a park, where he will not be shy, and start screaming with him," says Polina Pavlyukova. "First stand side by side, then take a step away from each other, increasing the distance , and then invite the child to scream himself.

© Aleksey Durasov/TASS

At the same time, it is necessary not only to shout, but to attract the attention of others so that they immediately understand that the child is not being capricious, but is in danger. The correct phrases are: “Let me go, I don’t know you!”, “I don’t know this person! He wants to take me away!”, “Help! Call the police!”, “My parents do not allow me to leave with this person!”.

The correct phrases are: “Let me go, I don’t know you!”, “I don’t know this person! He wants to take me away!”, “Help! Call the police!”, “My parents do not allow me to leave with this person!”.

It is also necessary to explain to the child who he can turn to for help if he gets lost in transport, if he is in trouble.

"Tell us who a 'safe adult' is: a passer-by with a child, a police officer, a subway employee, a store employee," explains Polina Pavlyukova.

How do you know if a child has been sexually abused?

Experts urge parents to always be attentive to their children. Any strange, unusual behavior for a child should alert.

See also

Checking the connection: how to build close relationships with children and not lose them

"The fact that a child has been sexually abused can be spoken of as immediate signs - skin lesions, bruises, pain, physical damage around intimate areas, marks on underwear, problems with walking, and the avoidance of certain people or situations by the child, sexualized behavior that is uncharacteristic for age,” explains Artem Novikov.

In such situations, even if the child did not tell about the violence and the adult is not sure of his guesses, one should immediately contact a qualified child psychiatrist, psychotherapist. The mistake of many parents is to try to ensure that the child forgets about what happened, to pretend that nothing happened. Rehabilitation is needed for all victims of sexual violence, and children in particular.

What to do if you see a strange person with a child and it seems that the child is in danger?

"Unfortunately, it is only after tragedies that most adults begin to react to safety issues, to the need to be more attentive," says Polina Pavlyukova.

The tragedy that happened in early January 2022 in Kostroma, when two men abducted a five-year-old girl in front of passersby, proves that adults most often do not intervene if they see the strange behavior of strangers towards children. Experts urge not to be embarrassed to look stupid and make a mistake, in case of a mistake you can always apologize, such questions will not offend an adequate parent.

"The instructions are simple," explains Polina Pavlyukova.

Here is her point by point:

1. Do not come within two arms' length of potential abductors. The conversation is best recorded. Use audio or video recording on your phone. Take a photo of the person and the child.

2. If there are other people nearby, draw attention to the situation with a loud call, questions from outside.

3. Ask your child: "Do you need help? Do you know this person?" and rate the answer.

4. Be sure to report the incident to the police at 112.

5. If a person left a child and ran away, remember where he ran away, his special signs and details of clothing that were not included in the photo.

6. If the child knows the parent's phone number, call them. Do not leave the child alone until the arrival of the parents or the police.

Karina Saltykova, Alexey Durasov

Child psychologist "SM-Doctor" gave advice on how to help a child find friends

We figure out how parents can help a child experiencing communication difficulties and not injure him even more.

We deal with Victoria Bogdanova, a child psychologist, an employee of the SM-Doctor clinic for children and adolescents in Maryina Roscha.

Why can't the child find friends?

In most cases, the problem lies in his parents. Among the common reasons are hyperprotection, limited communication with peers, lack of conditions for the child's self-affirmation, or a negative attitude of parents towards his independent actions. All this can lead to the psychological unpreparedness of the child to communicate with other children.

In addition to parental upbringing, communication problems may also be related to the child's personality, for example, if he is too withdrawn or shy.

The third source of problems with socialization can be the children's community itself, which is often quite cruel. Modern children usually spend their time playing alone, often at the computer. This leads to the fact that boys and girls do not know the usual ways for us to get to know each other. In addition, their ability to empathize is not so strongly developed, it is difficult for them to support each other and talk about important topics.

In addition, their ability to empathize is not so strongly developed, it is difficult for them to support each other and talk about important topics.

Adults should start working on developing a friendly attitude towards relatives and peers in a child from about 2-3 years old. It is possible to induce emotional responsiveness in children through reading fairy tales: the child must understand that the characters experience certain feelings that need to be treated with care. Some parents, fearing for their child, impose on him a negative and wary attitude towards other people, and this forms difficulties with communication. To avoid such consequences, it is necessary to educate the child in openness to people, and not alertness and negativity.

Signs indicating that the child has problems with socialization

Naturally, each person is formed in his own way, has individual characteristics, and this is connected not only with the nervous system and temperament, but also with the conditions of development. Starting from the age of 4-5, the level of significance of contacts with peers for a child only increases. Therefore, if your child:

Starting from the age of 4-5, the level of significance of contacts with peers for a child only increases. Therefore, if your child:

- is aggressive towards his peers,

- complains about the lack of friends or the unwillingness of peers to communicate with him,

- goes to kindergarten or school reluctantly,

- does not call up with anyone, does not invite to visit (or if no one calls and invites him),

- is often alone,

- spends all his time playing computer games/reading/TV,

you should pay attention to a possible problem and start taking certain actions to solve it.

Consider the problem on the example of a language understandable to everyone - the language of animation. On September 14, the Disney Channel begins showing the animated series Owl House, which is dedicated to this topic. The main character of the series, Luz, is so passionate about fantasy books that her peers consider her strange and do not want to be friends with her.

If in reality the parents are faced with a similar situation shown in the animated series, is it worth encouraging the interests of the child and his ways of expressing himself when his peers shun him? How can this situation be corrected?

It is worth noting that the girl immersed herself in fantasy books was not accidental: there was something wrong with her relationship with her mother from the very beginning. Escape to the magical world allowed Luz to find what she lacked in real life: the ability to have her own opinion, to defend her will and interests. She managed to realize herself in a world inhabited by rebels and freedom-loving characters.

Luz's infatuation began to spread in a form that frightened her peers and adults, her eccentric behavior at school harmed those around her. Definitely, parents should support their children's hobbies, however, they need to tell them about the existence of personal boundaries of other people and that an unusual form of self-expression can be repulsive. To close the need, you need to find, together with the child, the place where it is acceptable, and it’s definitely not worth extending your eccentricities to all people.

To close the need, you need to find, together with the child, the place where it is acceptable, and it’s definitely not worth extending your eccentricities to all people.

It is important for parents to build close trusting relationships with the child, to encourage his interests, because in this way the child's feelings and experiences are sublimated. And the situation can be corrected, for example, through art therapy or joint work of the parent, child and psychologist. The first task is to understand which needs are not satisfied.

Often, parents send their child to a kindergarten or send him to a summer camp so that he is socialized there. But what if he doesn't feel comfortable there?

In such cases, parents are most often convinced that they know how and what will be best and right for their child. In most of these situations, they do not focus on the real desires and needs of children, but project their own onto them. Please ask your child about where he wants to go or go, how he feels being away from home, what difficulties he faces. It is very important not to leave him alone with his experiences and not downplay his problems. Help your child find the answer to a difficult question, cope with a difficult situation. In the animated series Owl House, a mother wants to commit an act against her daughter's will, and this only provokes her escape into a fantasy world. It is difficult for a girl to find friendly relationships, and her mother does not listen to the needs of her child, which only aggravates the situation. In her place, it would be worth acting quite the opposite: to establish contact with her daughter and find out about her desires.

Please ask your child about where he wants to go or go, how he feels being away from home, what difficulties he faces. It is very important not to leave him alone with his experiences and not downplay his problems. Help your child find the answer to a difficult question, cope with a difficult situation. In the animated series Owl House, a mother wants to commit an act against her daughter's will, and this only provokes her escape into a fantasy world. It is difficult for a girl to find friendly relationships, and her mother does not listen to the needs of her child, which only aggravates the situation. In her place, it would be worth acting quite the opposite: to establish contact with her daughter and find out about her desires.

Equally important is to help the child not withdraw into himself. So, in order not to allow the child to go into compensatory fantasies, parents should first of all develop in him the skill of accepting reality with its difficulties. Helping a child cope with failures is possible only through emotional support: asking about his condition, sharing experiences, talking about his experiences from childhood. In this way, the parent will be able to help the child not be disappointed and not withdraw into himself, even when it seems that those around him do not accept him.

In this way, the parent will be able to help the child not be disappointed and not withdraw into himself, even when it seems that those around him do not accept him.

What parents should remember

First, talk to your child. The words “I see that you are sad / angry / worried. I would like your relationship with the guys to develop differently” are really important, since a child at any age should feel that the parent loves him, is always ready to listen and is aware of his difficulties. This approach helps build trust.

Secondly, it is important for the parent himself to stop overprotecting the child, unquestioningly fulfill his every desire and indulge his every demand. This is necessary so that he learns to independently solve emerging issues and cope with his own egoism. For example, children often demand to play by their rules, and if they lose, they are offended and upset. But life in society does not work like that - a child must be able to play together with other children: sometimes under someone else's guidance, sometimes according to different rules.

Everyone knows that children copy the behavioral model of their parents, which means that you can correct their behavior through your own example. You can convey an important experience without notations and moralizing by telling the child the story of meeting his childhood friends, about how friendship flowed, about quarrels and reconciliations.

Initiate visits and contacts with other children. If possible, change the child's living conditions and social circle as little as possible: because of frequent moves, it will be difficult for him to build close relationships with peers.

Watch together movies and cartoons that raise this topic, and be sure to discuss the actions and behavior of the characters after watching. From the side it is always easier to assess the situation, and then try to shift it to your own experience.

What will help the child to join the team?

There are basic skills and abilities that will help the child get used to the team, but work on their development, of course, should be carried out by parents.

- The ability to understand one's feelings and emotions, as well as the ability to manage and express them in an adequate form. From an early age, parents need to develop the emotional intelligence of their children. For example, you need to teach your child to verbally express resentment without provoking conflict.

- The desire of the child himself to maintain emotional contact and intimacy with other people, to share and be able to understand their feelings. It is important that the child wants to take part in games with peers, perform collective tasks, and at the same time not be afraid to take the initiative in his own hands or support the initiative of other people.

- An equally valuable skill is the understanding of boundaries, as well as the ability to accept refusals and say “no” yourself. The child should be aware of the existence of private property - his own and other people's toys.

The ability to keep up a conversation, joke and ask questions.