How to increase reading fluency

How to Improve Reading Fluency for Better Comprehension | Scholastic

You’ve spent years reading storybooks, store signs, and cereal boxes to your child. But now that they're learning to read out loud by themselves, story time might feel like new territory. When your growing reader furrows their brow with every word and stumbles through most sentences, there are certain steps you can take to set them up for lifelong reading success.

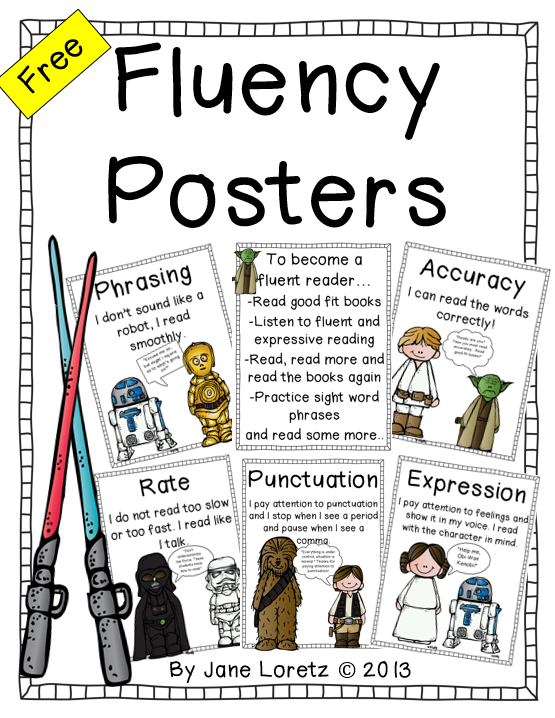

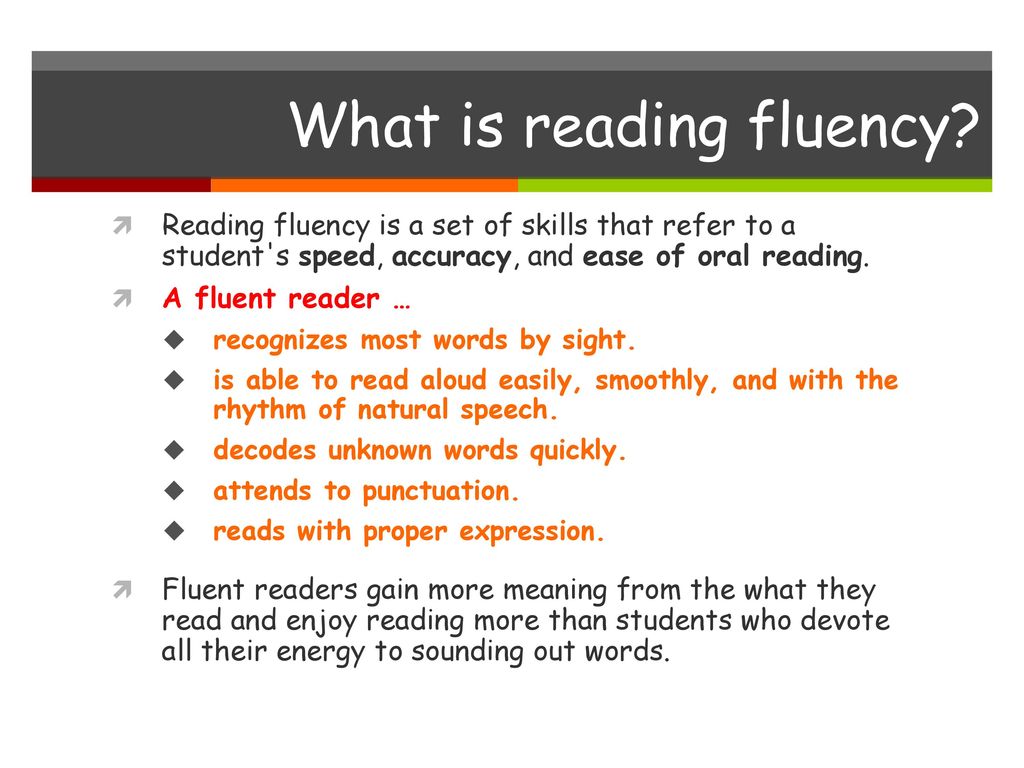

Reading fluency is the ability to read out loud accurately, at a good pace (not too slow or too fast), and with expression. “Although it’s typically measured in school when children start reading on their own, such as at the end of first grade, reading fluency is something you can start working on with them even before then,” says Helen Maniates, Ph.D., associate professor of teacher education at the University of San Francisco.

And it certainly pays to, because reading skills can help your child get more out of every subject in school. “Reading fluency contributes to reading comprehension,” says Maniates. “When children read slowly, don’t pay attention to punctuation, or struggle with particular words, they lose track of the ideas in the text.” Set your child up for academic success with these easy — and fun! — reading approaches.

1. Show them your own fluent reading.

The more often your child hears fluent reading, the more likely they are to pick it up. “Start by reading a paragraph or a full page from a book, and then ask your child to read it,” says Brook Sawyer, Ph.D., an associate professor focusing on language and literacy development at the College of Education at Lehigh University. “When you provide that model, it’s an opportunity for the child to get familiar with the story, understand the pacing, and then mimic you.”

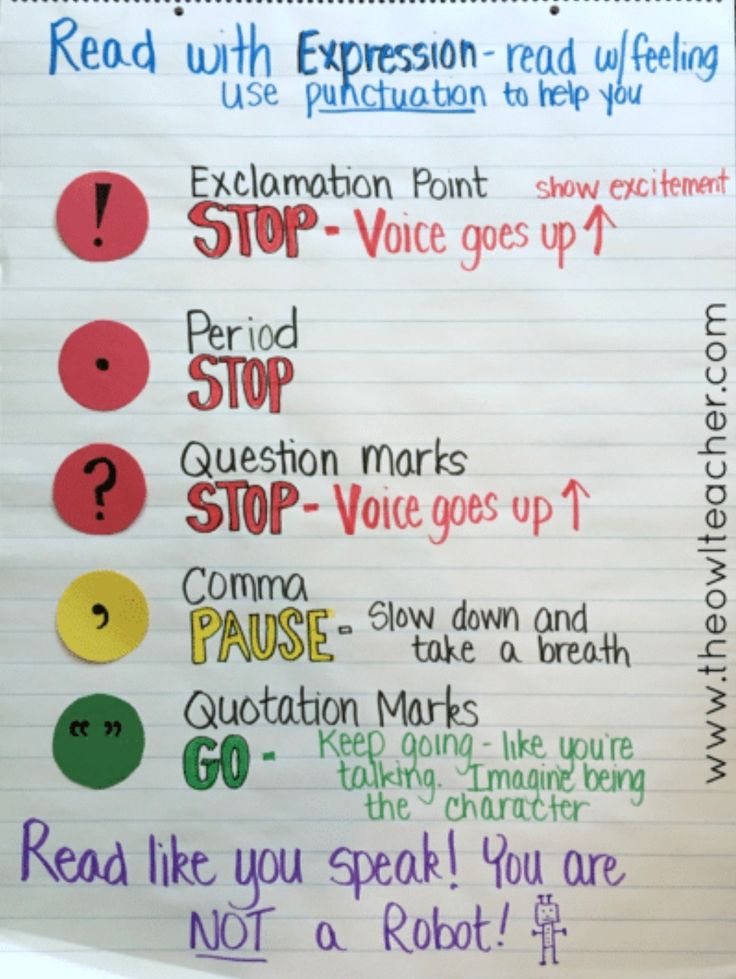

As you model, channel your high school drama class: Read with exuberant, Oscar-worthy expression and pause at the appropriate times (at commas, periods, etc.) to demonstrate the cadence of our language. It’s also helpful to play audiobooks in the car to squeeze in extra modeling time when you’re on the go, says Sawyer.

It’s also helpful to play audiobooks in the car to squeeze in extra modeling time when you’re on the go, says Sawyer.

2. Teach your child how to track words.

If you’ve ever learned a new language, you know how difficult it can be to decipher where one word ends and the next begins when listening to a conversation. Your little learner might feel the same way when they try to follow along during story time. That’s where tracking — or running your finger under words as you read them — comes in handy. You can track while you’re reading to your child, or ask them to track when they're reading out loud.

“When kids are first learning to read, it’s really important for them to touch each word to understand the correspondence between the spoken and written language,” says Maniates. “It’s a stepping-stone strategy. Eventually, they’ll be able to tackle larger phrases without reading word by word.” To make tracking words more fun for your child, equip them with plastic Martian or witch fingers!

3. Try choral reading together.

Try choral reading together.

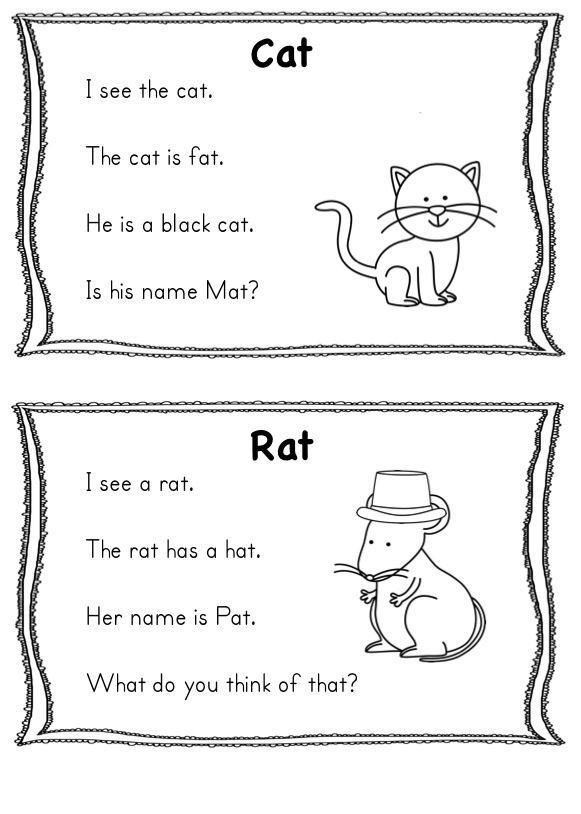

Not to worry: No singing skills required! Choral reading simply means you read a story out loud, and ask your child to read along with you at the same pace. This helps them understand what fluent reading feels like, and gives them the chance to practice it themselves at your pace, says Sawyer. It’s OK if you’re a tiny bit ahead of them — just be sure to pick a book that they can already read themselves. That way, they're working on pacing and accuracy rather than decoding new words.

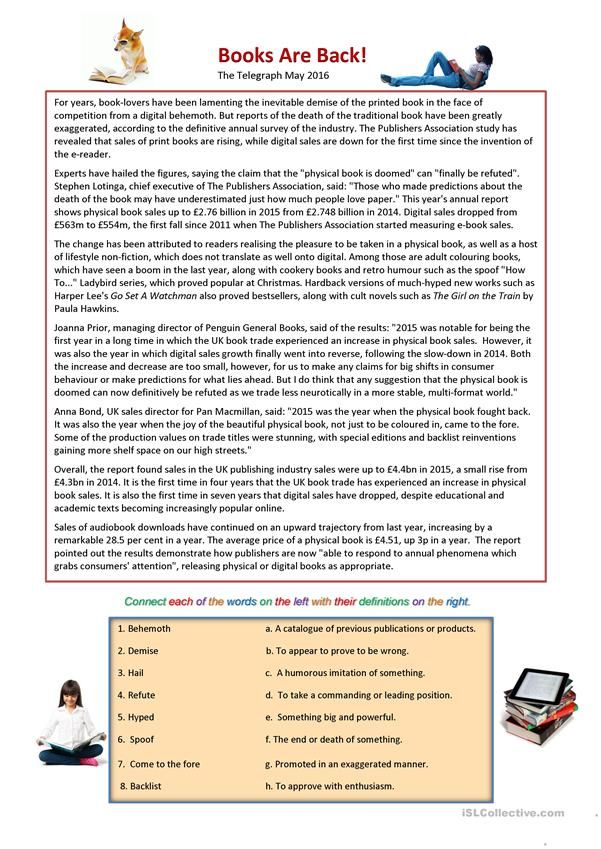

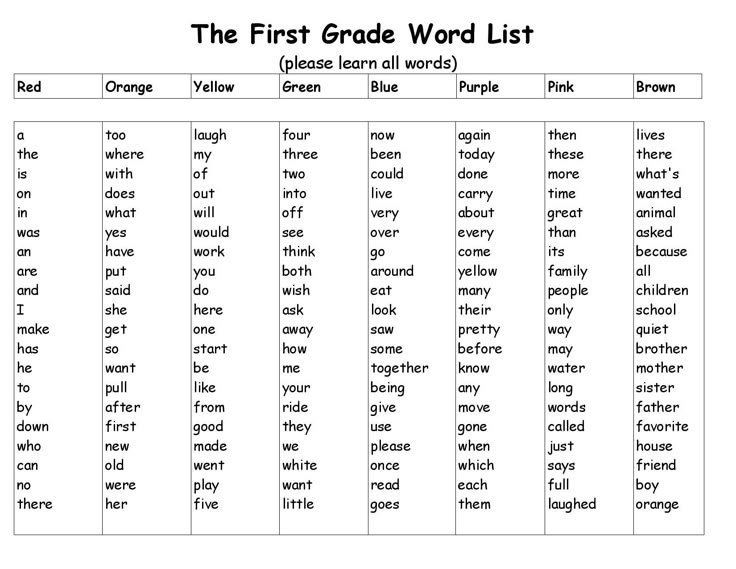

4. Focus on sight words.

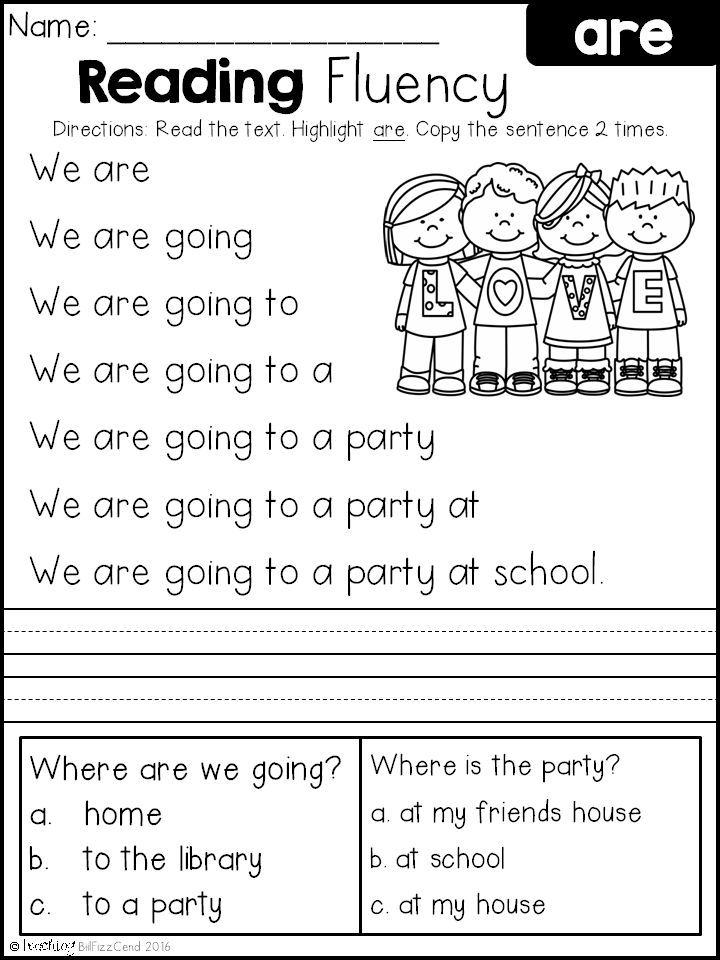

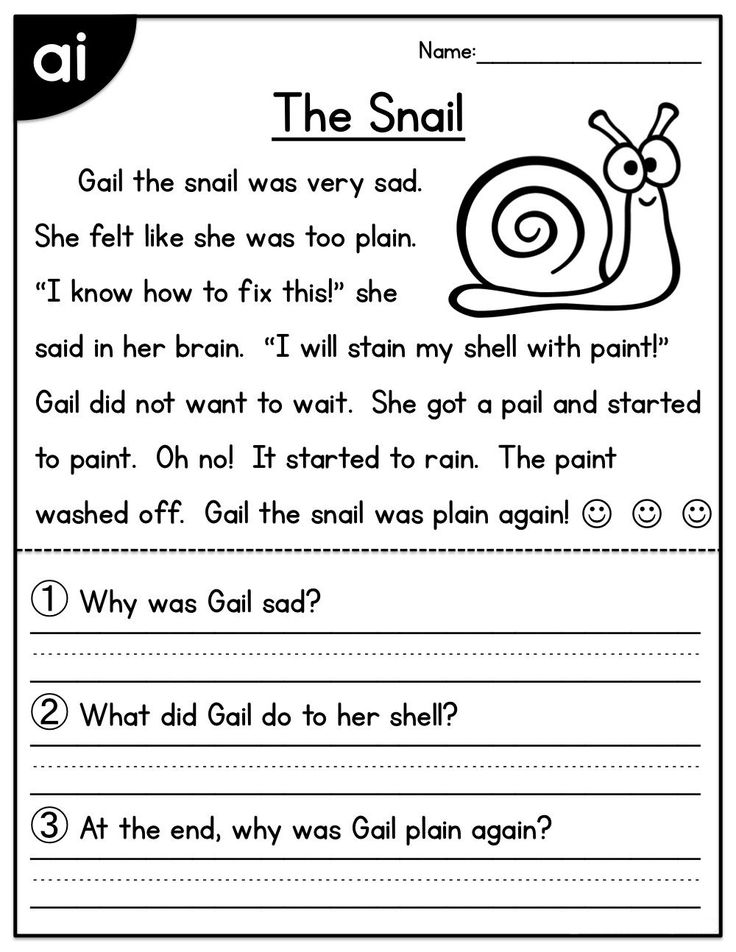

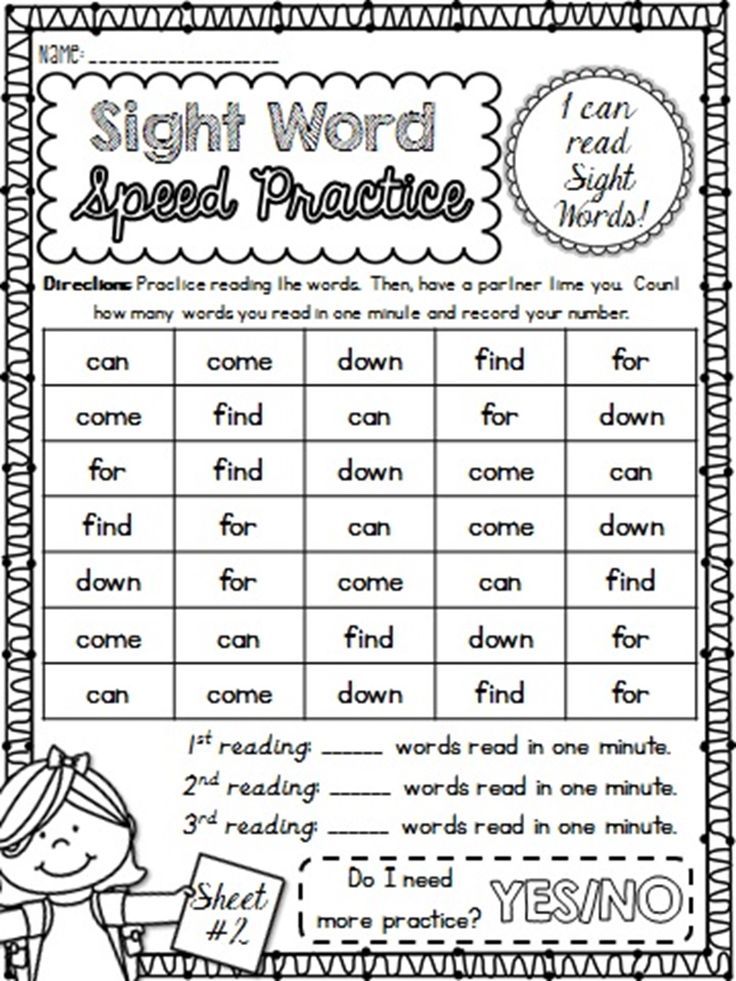

You may notice that your child struggles with certain words like “walk” or “house,” also known as sight words. “These are words that are not decodable by sounding them out phonetically,” says Maniates. “They often overlap with high-frequency words, which are those that appear very often in children’s texts.” When your child memorizes what these words look like and can instantly recognize them, they won’t have to spend valuable reading time (and brainpower!) trying to sound them out.

Turn teaching sight words into a game: Spell the words out with magnetic letters; write them on a large piece of paper and ask your child to splat the correct word with a fly swatter when you say it; or use activity packs to help them easily learn them anywhere.

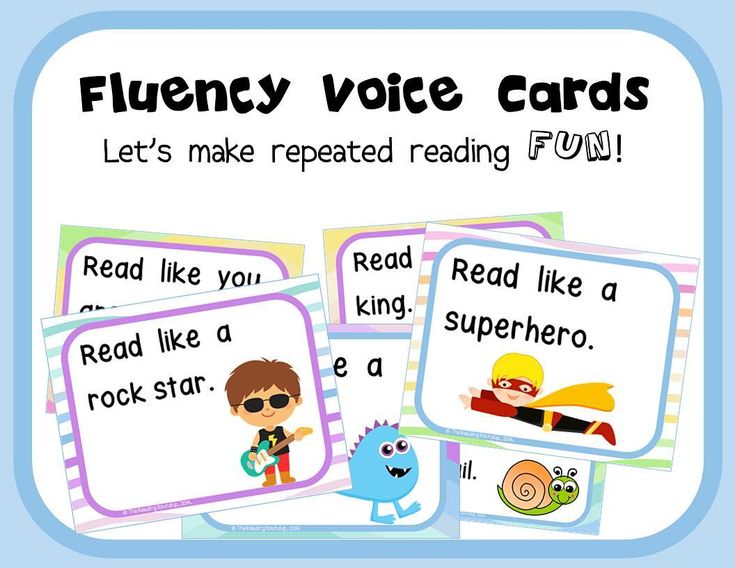

5. Recruit a friendly audience.

Just like us grown-ups, kids are more likely to fumble over their words when they feel nervous or uncomfortable. Set up an inviting stage for them to practice reading stories out loud by creating an audience out of their favorite stuffed animals or recruiting your family pet to listen along. “Some kids really don’t like to read in front of other people, either because they feel shy or feel pressure around it,” says Sawyer. “Start by reading a story together, and then for extra practice, set up a pretend audience that they can read out loud for.”

Eventually, this might also help your child read with more expression. “Reading out loud is almost like a performance, because you’re thinking about your voice, the volume, the pitch, the tone, and you might even be making facial expressions or gestures,” says Maniates. “We want kids to do this when they’re young because that’s how they’ll internalize stories when they read silently to themselves later on.”

“We want kids to do this when they’re young because that’s how they’ll internalize stories when they read silently to themselves later on.”

6. Record, evaluate, and repeat!

Every so often, when your child is reading out loud, record a passage and then listen to it together. You might celebrate that they read on pace, then record it a second time while aiming for more expression. “Set a specific goal for the session, and decide together what you want to do a little better,” says Sawyer. Just be sure to make it a relaxed setting (this is something you can do in jammies and on the sofa!) and focus on the positive strides your child is making.

It's also a good time to incorporate texts that are easy for your child to read. “Parents are often concerned with getting their kids ahead in reading, but when they’re struggling, going back to easier texts can be really helpful,” says Maniates. “It builds confidence and consolidates their skills so they can expand upon them.”

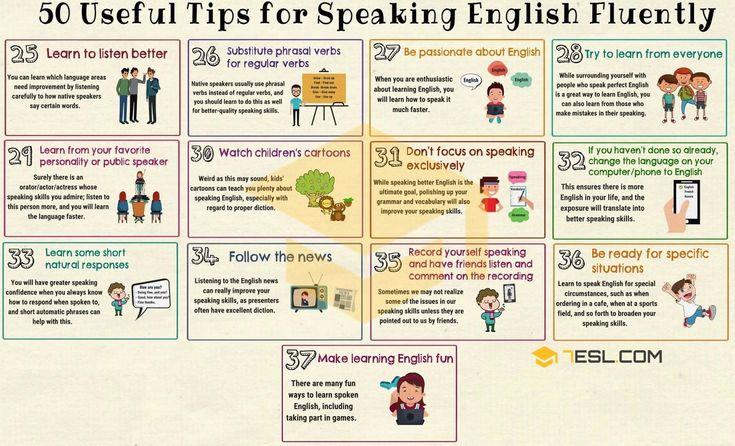

Shop books that build fluency skills below! You can find all books and activities at The Scholastic Store.

Five Evidence-Based Ways to Improve Reading Fluency in Elementary and Secondary Grades

Imagine this conversation between an instructional coach and a sixth-grade social studies teacher concerned about student performance on unit tests.

Instructional Coach: When we spoke last week, we decided that you would interview a few students to learn why they struggle with their social studies unit tests and talk to other teachers to see if they are noticing similar trends. What did you learn?

Teacher: I began by talking to colleagues, and they are experiencing similar things. I then spoke to a few students and learned that they often struggle on unit tests because they have difficulty reading and understanding the questions.

Coach: How do students perform when working on daily activities?

Teacher: Students usually do well and can answer the questions that I ask about what we are reading. This is why I am confused by their poor performance on the unit tests.

Coach: When students are reading during daily activities, what do you notice?

Teacher: Well, some have low reading levels, so I often read the material to them.

Coach: Do you read the material when it comes time for the test?

Teacher: No, I want to see what they can do independently.

Coach: What I heard you say is that students perform well on daily activities when you read the material to them, but they struggle when they are expected to read and answer questions on their own. We may need to dig into their reading fluency skills and help them develop their skills in this area in order to help them perform better on their social studies unit tests.

Teacher: I see what you mean, and I will need help thinking about how to better support my students’ reading fluency.

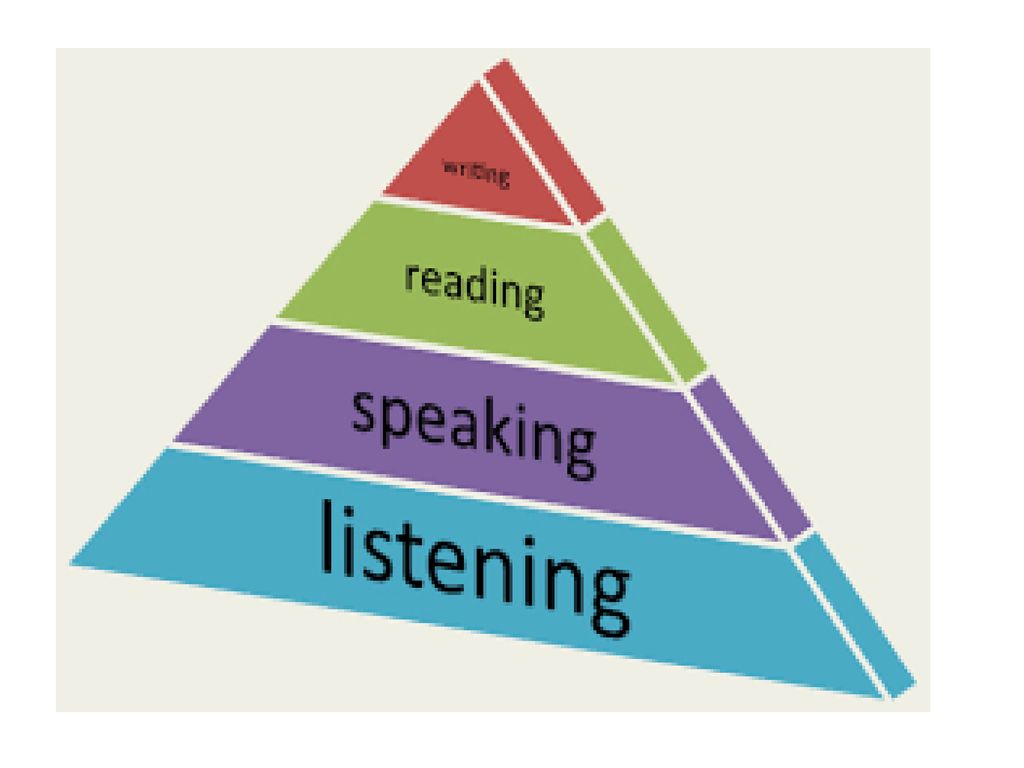

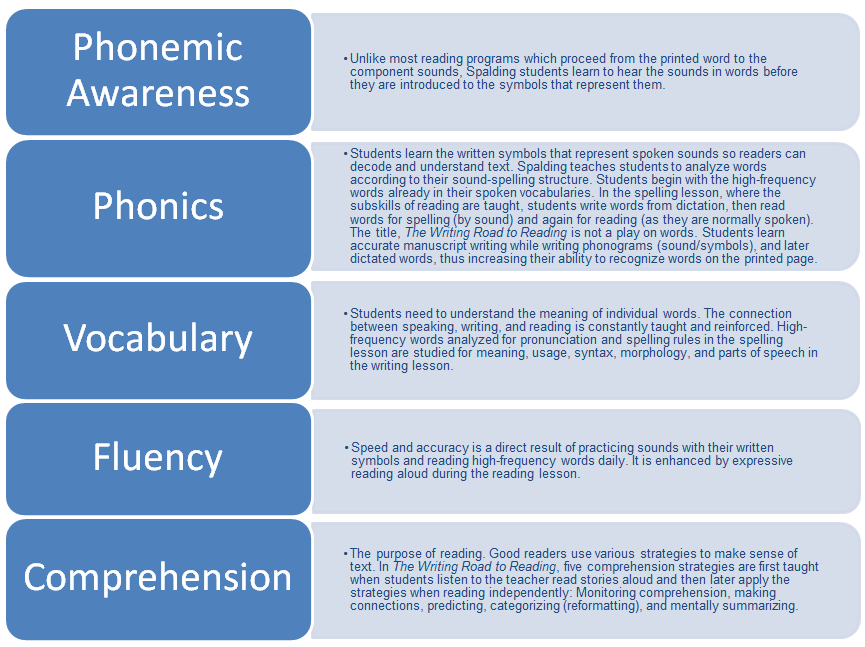

In this blog post, we focus on reading fluency in elementary and secondary classrooms. Reading fluency is a critical reading skill that facilitates reading for understanding and is our ultimate goal for teaching reading. It involves reading with appropriate rate, accuracy, and expression (National Reading Panel, 2002). Pikulski and Chard defined reading fluency as “efficient, effective word-recognition skills that permit a reader to construct the meaning of text. Fluency is manifested in accurate, rapid, expressive oral reading and is applied during, and makes possible, silent reading comprehension” (2011, p. 510).

It involves reading with appropriate rate, accuracy, and expression (National Reading Panel, 2002). Pikulski and Chard defined reading fluency as “efficient, effective word-recognition skills that permit a reader to construct the meaning of text. Fluency is manifested in accurate, rapid, expressive oral reading and is applied during, and makes possible, silent reading comprehension” (2011, p. 510).

The importance of reading fluency for students’ reading comprehension is further supported by a recent National Assessment of Educational Progress report (NAEP, 2021). The NAEP study found that oral reading fluency was consistently and positively related to fourth-grade students’ performance on the NAEP reading test, which measures reading comprehension and is used to evaluate our nation’s progress in reading. In particular, students who scored low on the NAEP reading test showed difficulty with reading fluency, word-level reading skills, and text comprehension. Despite the importance of reading fluency, many teachers may be unsure how to best support the students they teach who struggle with reading. In this blog post, we share five evidence-based recommendations for improving reading fluency among struggling readers.

In this blog post, we share five evidence-based recommendations for improving reading fluency among struggling readers.

5 Recommendations for Improving Reading Fluency Among Struggling Readers

1. Develop students’ ability to decode words.

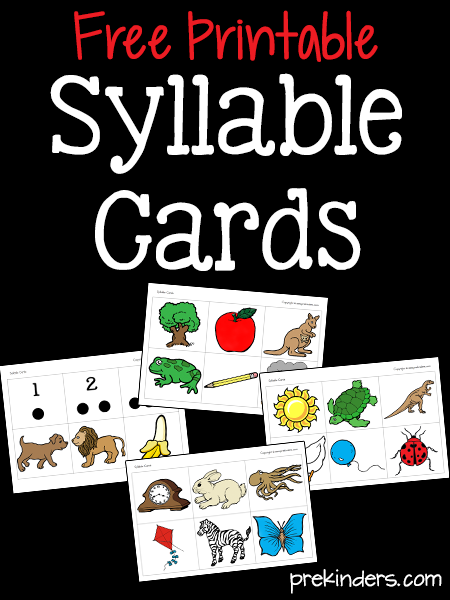

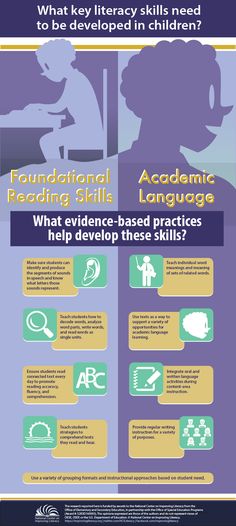

Many students who struggle with reading fall behind early in their education because they struggle with skills such as letter identification, letter-sound correspondence, or word recognition. These underlying word-reading skills are foundational for reading fluency. For students with significant reading difficulties, this word-level instruction is key to unlocking passage-level reading fluency.

When teaching these skills, it is important to deliver instruction that is explicit and systematic. Instruction should be explicit in the sense that the teacher must implement familiar routines, include many examples, and explain each skill in ways that are clear, visible, and consistent for students. Instruction should be systematic in that it should move from easier to more complex, build on higher-utility skills and what students know, and be appropriate for the task or lesson goal. The "I do, we do, you do” model is often used to plan an explicit and systematic lesson.

The "I do, we do, you do” model is often used to plan an explicit and systematic lesson.

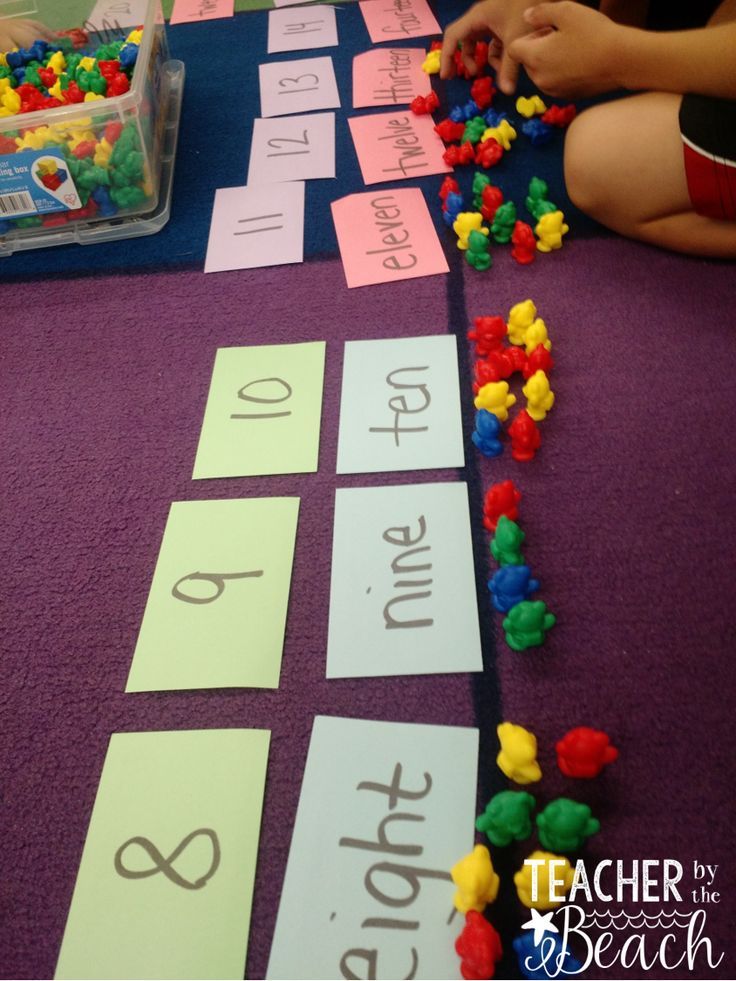

What foundational reading skills are important to teach in each grade? Here are some examples (The Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk [MCPER], 2016) of specific activities teachers might use when teaching one or more of these skills (this is not meant to be an exhaustive list):

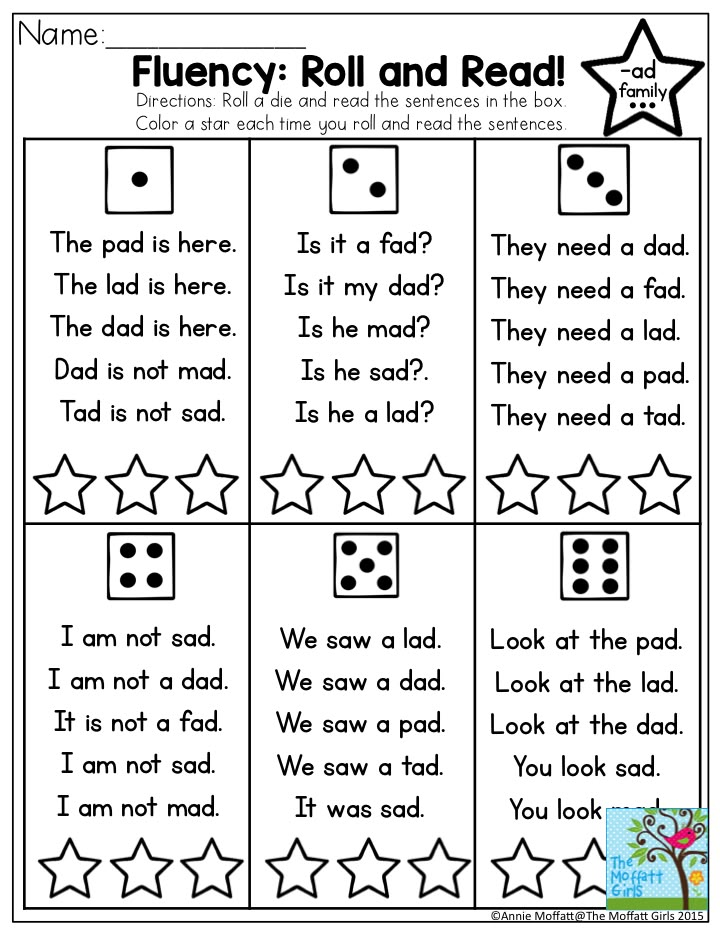

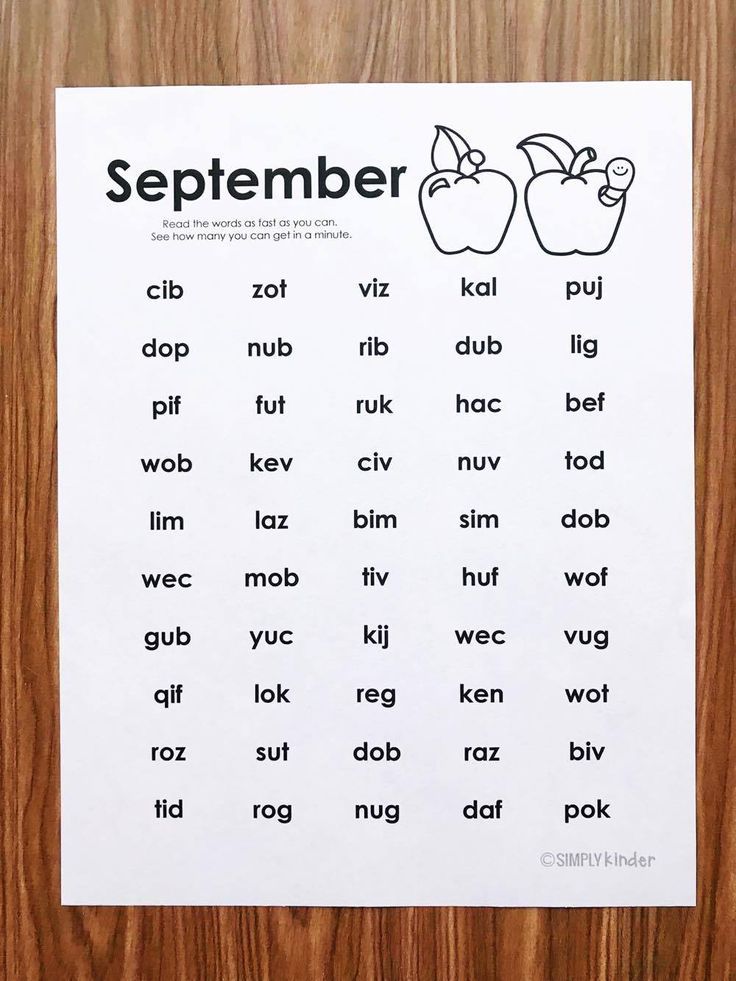

- Kindergarten: Introduce new and review previously learned letters and sounds; make or build words; introduce new and review previously learned high frequency words; use fluency practice with skills.

- Grade 1: Review phonological awareness skills; introduce sound, spelling partners, and morphemes; make or build words; introduce new and review previously learned high-frequency words; use fluency practice with skills.

- Grade 2: Make or build words; introduce new high-frequency words; use fluency practice with skills.

- Grades 3–5: Make or build words; use fluency practice with skills.

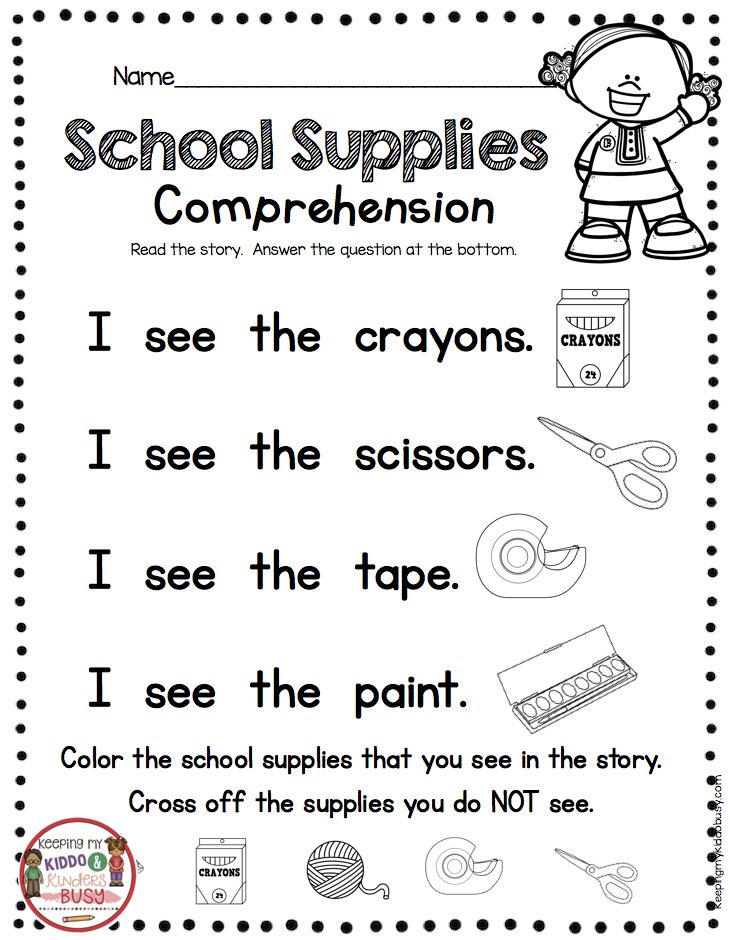

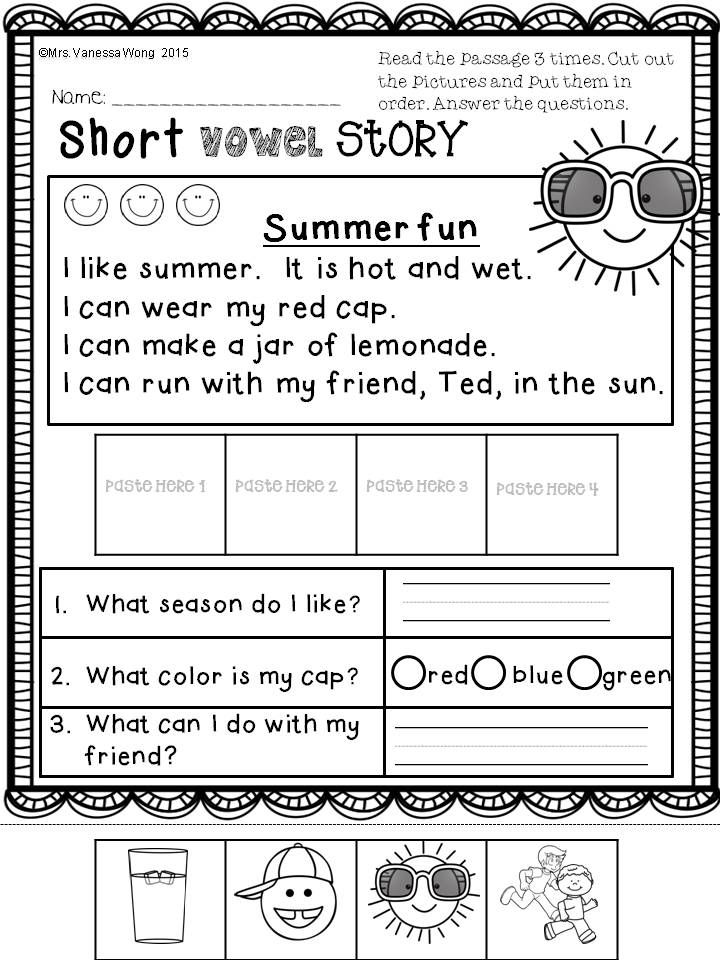

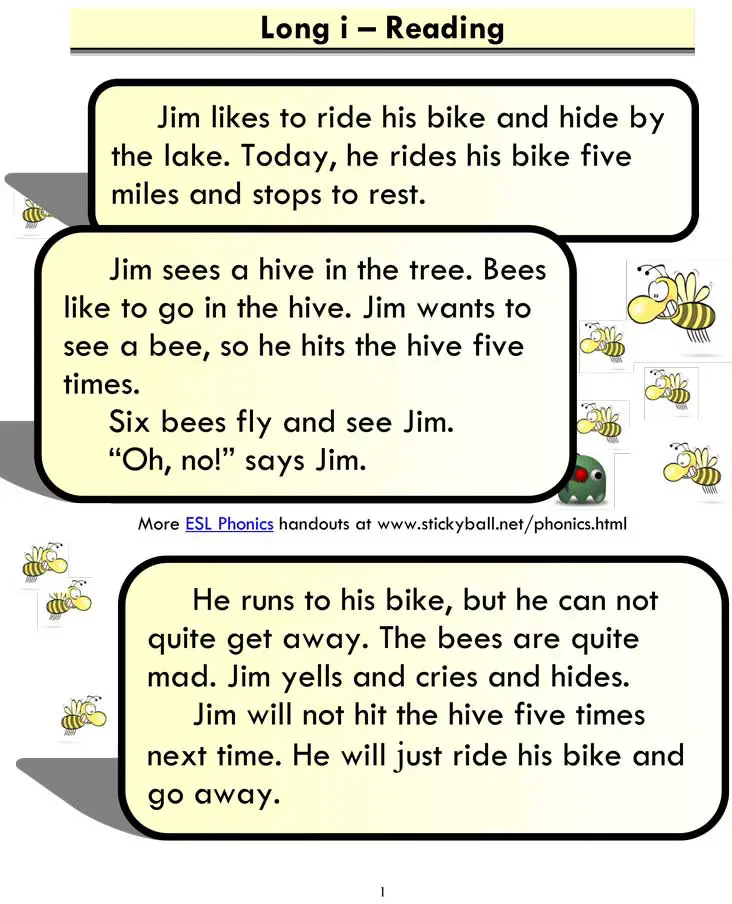

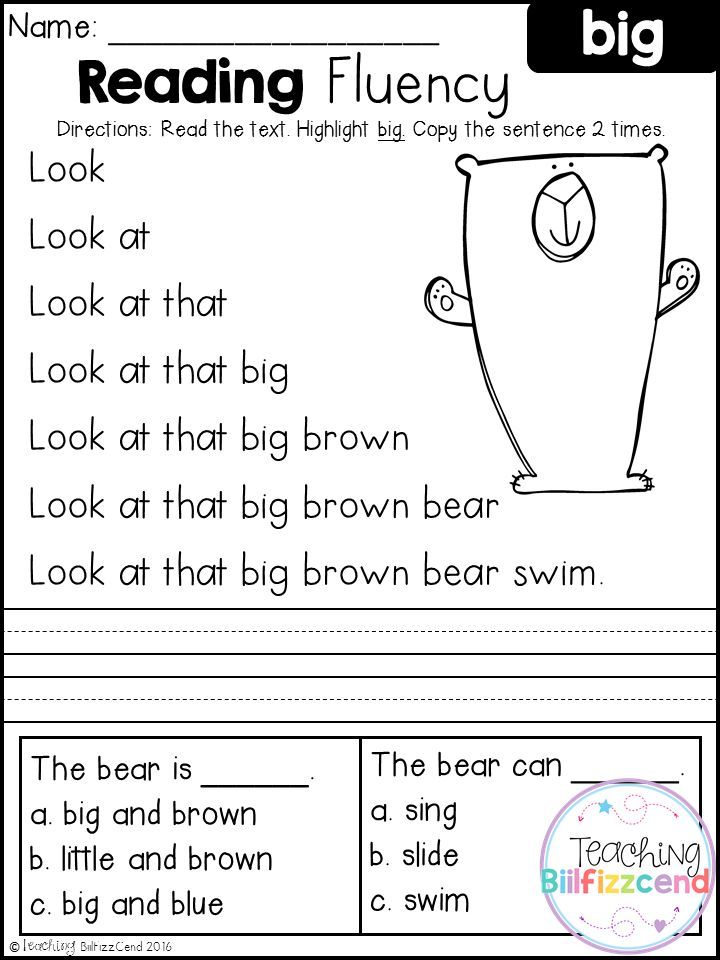

2. Ensure that each student reads connected text every day to support reading rate, accuracy, and expression.

Students may be proficient enough at reading lists of individual words, but they must also practice their skills in books or passages (i.e., connected text) to become fluent readers. Reading familiar books or passages allows students’ skills to become more automatic, which enables them to free up their attention to connect ideas in the text to background knowledge and increase their reading comprehension.

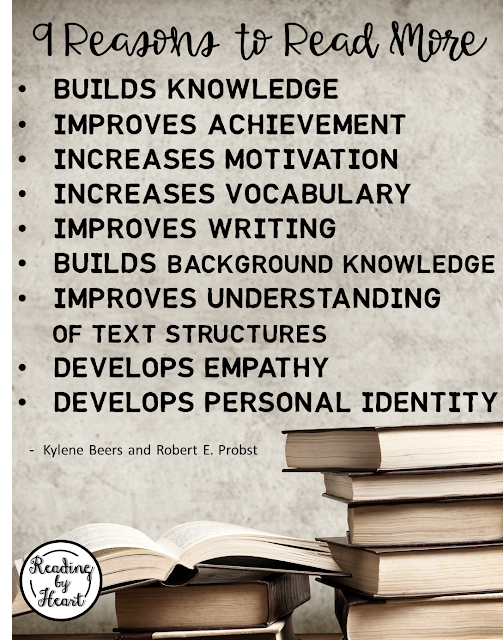

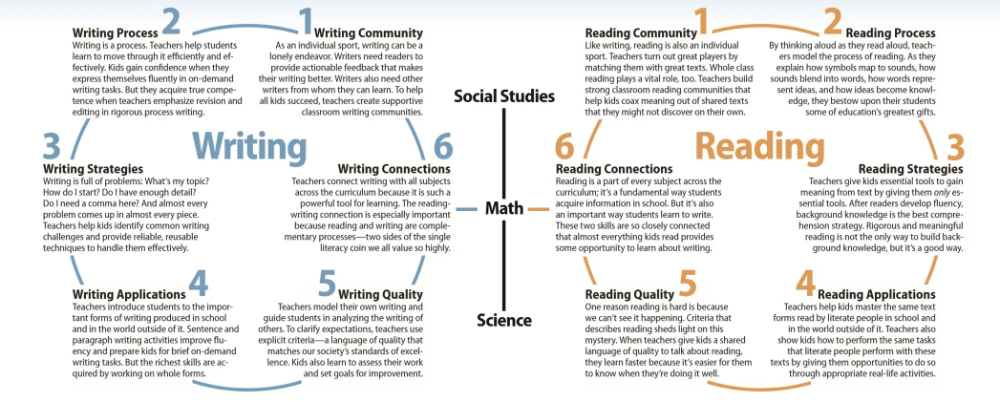

To get better at reading requires more time reading. When developing lesson plans, it is important that teachers identify opportunities for students to practice reading. This can, of course, happen in English and language arts classes, but it also should happen across content areas. Students often are motivated to read more when they are interested in the reading material and when they have adequate support.

At home, parents can encourage more reading each day by scheduling dedicated time for students to read independently (i. e., reading material independently with 95% to 100% accuracy) and by establishing a purpose for reading. For example, children can select a book to read that is of interest to them, and each day they can document what they read in a reading log. Daily entries in this reading log might include recording progress toward achieving a goal (e.g., increasing the number of words or pages read each day), brief summaries, connections made, difficulty vocabulary encountered, etc. Entries could be used to create a presentation to be shared with a student’s peers. Schoenbach, Greenleaf, and Murphy’s Reading for Understanding (2012) provides additional recommendations for reading logs (what they refer to as metacognitive logs).

e., reading material independently with 95% to 100% accuracy) and by establishing a purpose for reading. For example, children can select a book to read that is of interest to them, and each day they can document what they read in a reading log. Daily entries in this reading log might include recording progress toward achieving a goal (e.g., increasing the number of words or pages read each day), brief summaries, connections made, difficulty vocabulary encountered, etc. Entries could be used to create a presentation to be shared with a student’s peers. Schoenbach, Greenleaf, and Murphy’s Reading for Understanding (2012) provides additional recommendations for reading logs (what they refer to as metacognitive logs).

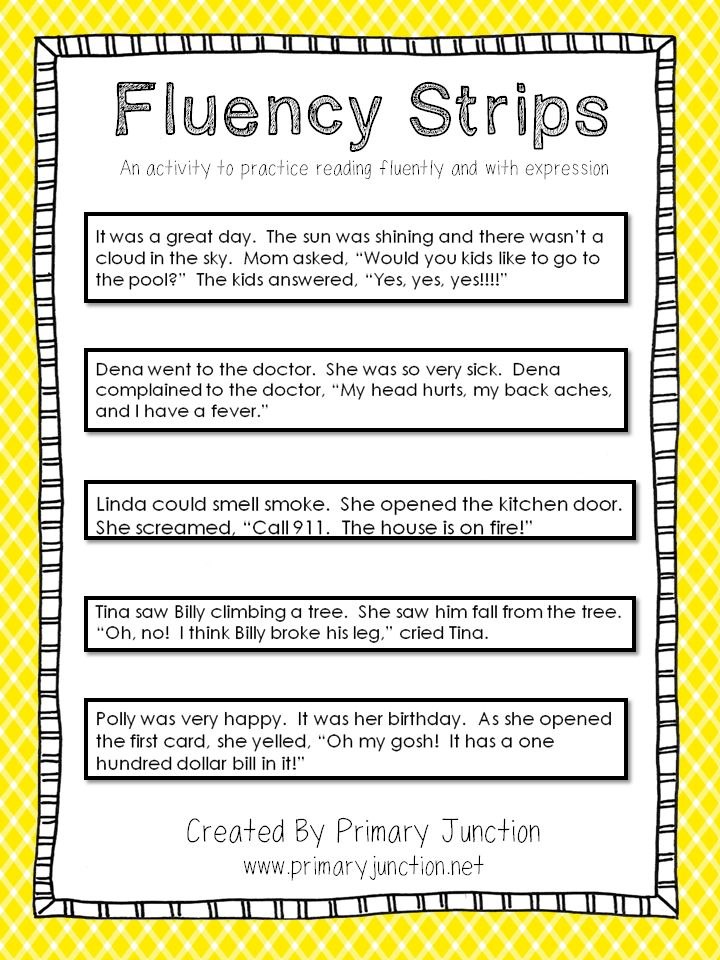

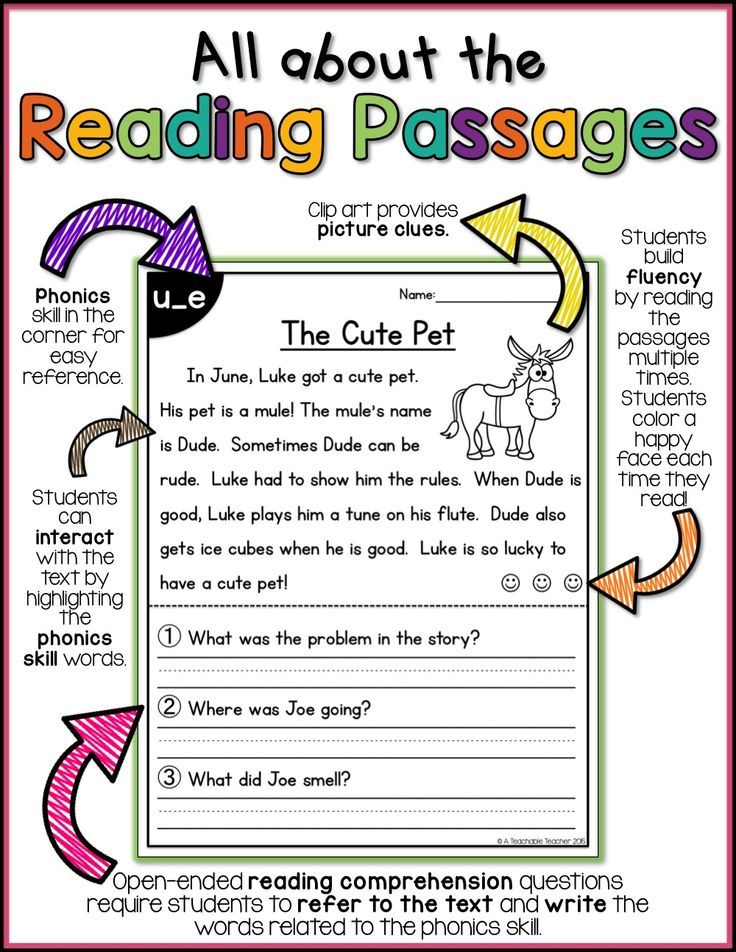

3. Model reading fluency for your students.

Read-alouds are a powerful and useful instructional tool that model important foundational skills (i.e., prosody, vocabulary, and that print conveys a message) for children in a way that explicitly and unambiguously teaches something (Roberts & Burchinal, 2001; Trelease, 2001). When paired with think-alouds, teachers can promote vocabulary acquisition and help students make sense of or make connections between ideas beyond the classroom (Beck, McKeown, & Kucan, 2013; Gold & Gibson, 2001; Massaro, 2017).

When paired with think-alouds, teachers can promote vocabulary acquisition and help students make sense of or make connections between ideas beyond the classroom (Beck, McKeown, & Kucan, 2013; Gold & Gibson, 2001; Massaro, 2017).

Read-alouds can be used to model reading fluency. For example, before reading a text, a teacher might say, “Follow along as I read. Listen to how I read the words at a steady pace and how I pause to take a quick breath at each period." Modeling reading fluency has been found to be an effective tool for improving reading fluency. Teachers or parents who are interested in incorporating this modeling within their read-aloud routines may find this read-aloud resource, developed by The Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk, to be helpful.

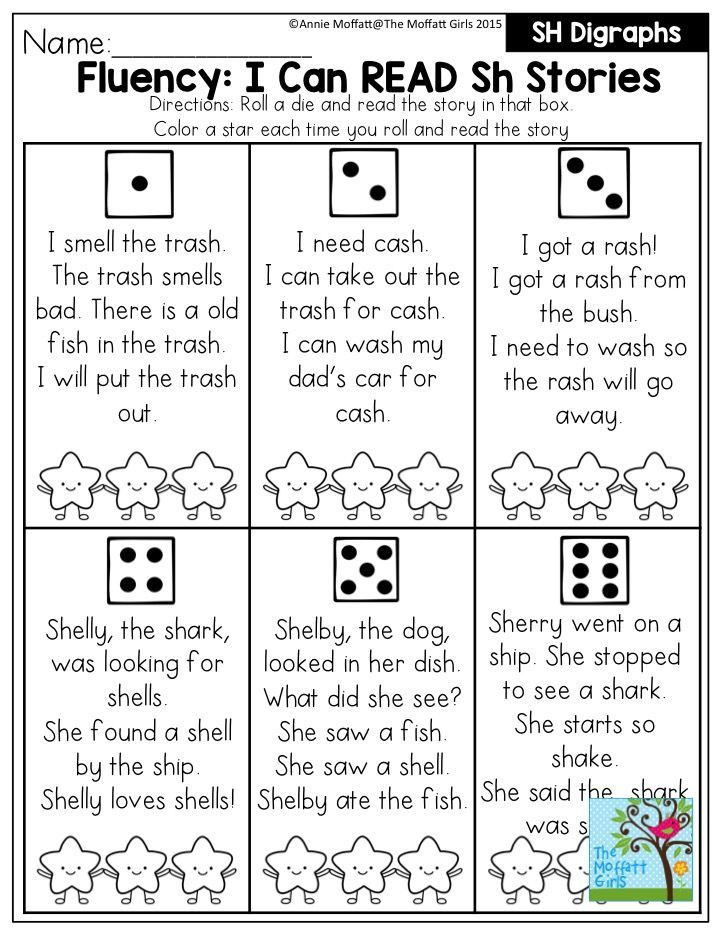

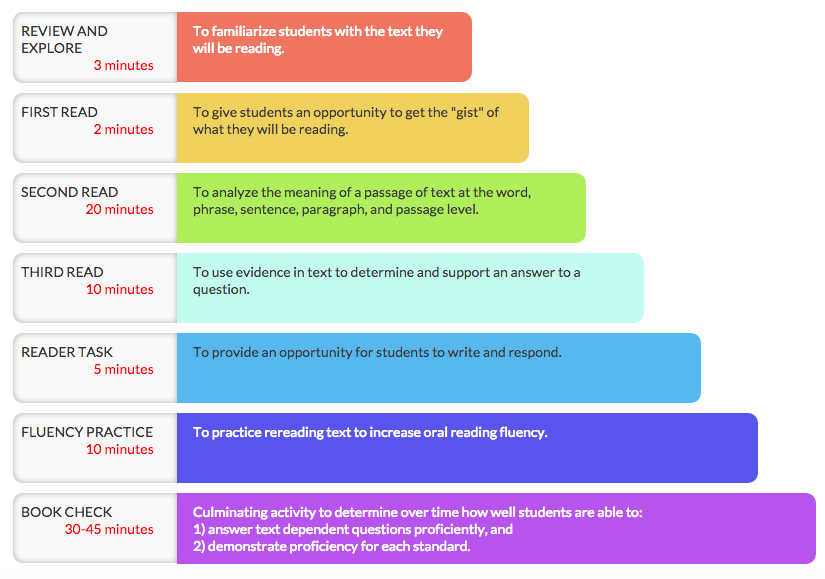

4. Take advantage of repeated reading routines.

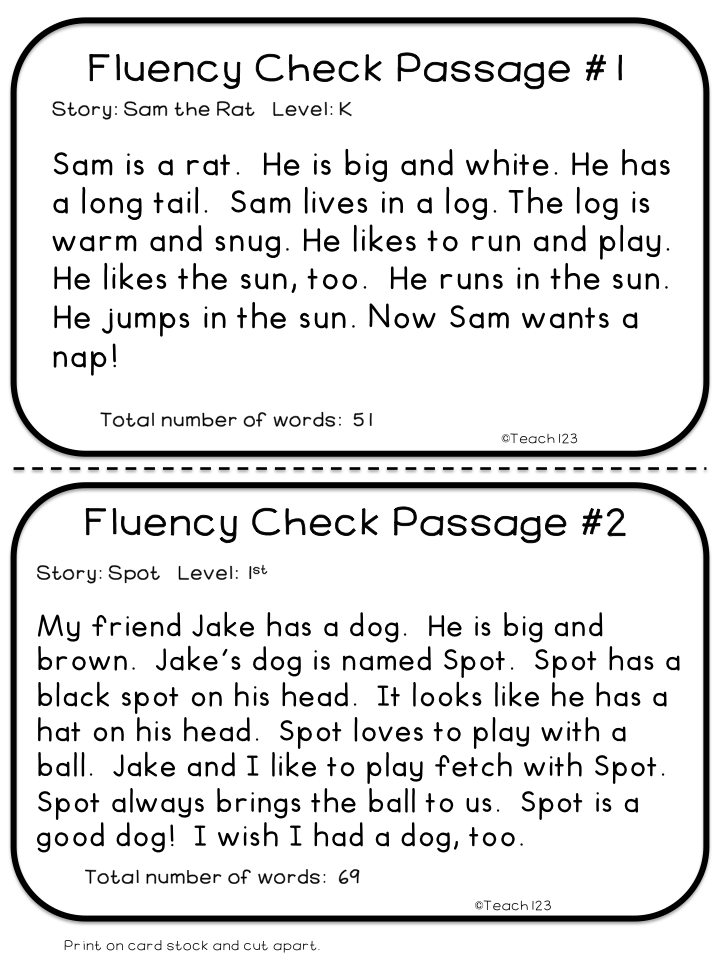

Repeated reading is reading and rereading material to match the (a) purpose of the lesson and (b) student’s reading ability. For example, if the purpose is to enhance reading rate, then select a text that is appropriate and at the student’s decoding level. The teacher and student can monitor the number of words read correctly and can discuss the story to check comprehension. Discussions after each read can change to focus on a different reading element (e.g., character, main idea).

The teacher and student can monitor the number of words read correctly and can discuss the story to check comprehension. Discussions after each read can change to focus on a different reading element (e.g., character, main idea).

Teachers who are interested in this routine can find lesson plans here that show how this routine can be taught following an explicit instructional approach (see page 59 of the PDF, which is page 196 in the original resource book).

- Students select a passage.

- The higher-performing student reads the lower-performing student’s passage first to provide a model.

- The lower-performing student practices reading through the passage three times with their partner. The partner marks student errors on a copy of the passage and provides feedback on student errors.

- Students read the passage a fourth time as quickly as possible. Partners time the student reading for 1 minute. This time is referred to as the “first timing.”

- Students record progress on their individual graphs in their workbooks.

5. Set fluency goals and use progress-monitoring data to inform instruction.

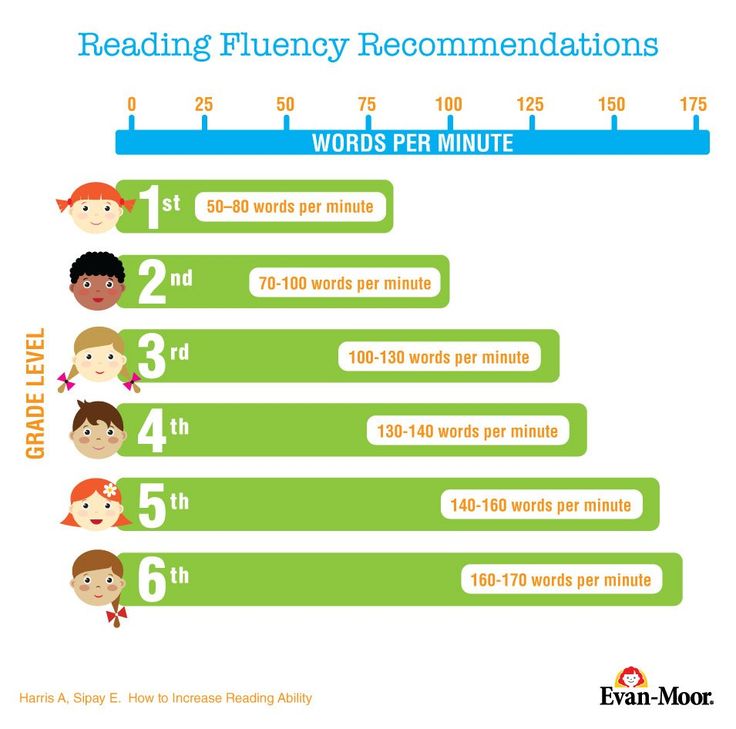

The combination of reading accuracy and rate (automaticity) is considered a student’s oral reading fluency (ORF). Beginning in the middle of first grade, ORF is a complex skill that develops gradually, measures accuracy without regard to reading rate, and is one way to screen students quickly to monitor progress and determine whether additional support is needed. Measuring ORF provides valuable information about the child’s ability to read connected text fluently. Below are a few resources to use when setting fluency goals and monitoring student progress:

- Reading Fluency Goal Setting template (Iowa Reading Research Center, n.d.a)

- Oral Reading Fluency Reflection Guide (Iowa Reading Research Center, n.d.b)

- Oral Reading Fluency Norms (Reading A-Z, 2021

Tracking or monitoring progress is important to determine student reading growth and is closely linked to both screening and diagnostic assessment. Progress monitoring, administered weekly or biweekly, is a systematic process to formatively track the progress of student growth of an intervention skill (e.g., fluency). It additionally provides information about the appropriate levels of text to use (The University of Texas Center for Reading and Language Arts, 2002). Progress monitoring can help you answer a number of questions, such as: Is learning happening? Is my teaching helping students make progress?

Progress monitoring, administered weekly or biweekly, is a systematic process to formatively track the progress of student growth of an intervention skill (e.g., fluency). It additionally provides information about the appropriate levels of text to use (The University of Texas Center for Reading and Language Arts, 2002). Progress monitoring can help you answer a number of questions, such as: Is learning happening? Is my teaching helping students make progress?

Take Action

- Review current or historical school and classroom data to determine how information and resources included in this blog might be used to further student learning.

- Choose one of the resources, routines, or strategies to implement in your classroom. Write and share reflections. How did the routine improve or strengthen your current practices? How did students respond differently to this routine versus what you normally do?

- Select one of the five recommendations about which to learn more.

Based on this new learning, make adjustments in one of your current classes to target one or more student’s needs.

Based on this new learning, make adjustments in one of your current classes to target one or more student’s needs. - Review one or more of the additional resources below and choose one to add to your existing classroom practices.

| Resource | Content |

|---|---|

| Fluency Practice: Techniques for Building Automaticity in Foundational Knowledge and Skills Authors: Datchuk & Hier, 2019 Audience: Elementary | Learn about the components of fluency practice, gain access to a checklist of steps to use when implementing a fluency practice session (i.e., before, during, and after), and see examples of scoring and graphing oral reading. |

| FCRR Student Center Activities Author: Florida Center for Reading Research, 2004-2010 Audience: Elementary | Materials to use during whole- or small-group instruction, centers/workstations, or for extended learning. |

| Effective Fluency Instruction and Progress Monitoring Author: The University of Texas Center for Reading and Language Arts, 2004 Audience: Elementary | Gain access to a presentation focused on fluency instruction, as well as strategy sets to teach letter sounds, regular word reading, irregular word reading, and fluency in connected text. |

| Essential Reading Strategies for the Struggling Reader: Activities for an Accelerated Reading Program Author: The University of Texas Center for Reading and Language Arts, 2001 Audience: Elementary, Secondary | Learn about and access supplemental literacy resources to support the five components of reading instruction. For fluency, activities include basic steps to teach reading fluency, partner reading, fluency word cards, page races, repeated readings, fast phrases, independent reading, and more. |

| Sight Word Fluency Lists Author: The Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk, 2017 Audience: Elementary | Access lesson materials that focus on sight word fluency and word recognition. Use materials for routines such as reading words aloud as a group, partner reading, repeated reading, paired reading, and more. |

| 10 Key Policies and Practices for Reading Intervention (The Key Strategies in Action 2: Use universal screening to identify students experiencing reading difficulties) Author: The Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risks, 2020 Audience: Elementary, Secondary | Learn about policies and practices for reading intervention, as well as key strategies in action. Practices for reading fluency include (but are not limited to) text reading, partner reading, fast phrases, diagnostic assessments, progress monitoring, and providing feedback. |

References

Beck, I., McKeown, M., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Datchuk, S., & Hier, B. (2019). Fluency practice: Techniques for building automaticity in foundational knowledge and skills. Exceptional Children, 51(6), 424-435.

Duke, N. & Pearson, D. (2008). Effective practices for developing reading comprehension. Journal of Education, 189(1/2), 107-122.

Florida Center for Reading Research. (n.d.). FCRR student center activities. https://www.fcrr.org/student-center-activities

Glaser, D. (2002). High school tutors: Their impact on elementary students’ reading fluency through implementing a research-based instruction model [Doctoral dissertation, Boise State University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Gold, J., & Gibson, A. (2001, June 14). Reading aloud to build comprehension. Reading Rockets. https://www.readingrockets.org/article/reading-aloud-build-comprehension

Reading Rockets. https://www.readingrockets.org/article/reading-aloud-build-comprehension

Iowa Reading Research Center. (n.d.a ). Oral reading fluency skills goal setting template. https://iowareadingresearch.org/oral-reading-fluency-goal-setting-template

Iowa Reading Research Center. (n.d.b). Oral reading fluency reflection guide. https://iowareadingresearch.org/oral-reading-fluency-reflection-guide

Massaro, D. (2017). Reading aloud to children: Benefits and implications for acquiring literacy before schooling begins. The American Journal of Psychology, 130(1), 63-72.

The Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk. (2014). Read-aloud routine for building vocabulary and comprehension skills in kindergarten through third grade. https://meadowscenter.org/files/resources/FlipBook_Screen1.pdf

The Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk. (2016). Sample literacy blocks, K-5. https://buildingrti.utexas. org/instructional-materials/sample-literacy-blocks-k-5

org/instructional-materials/sample-literacy-blocks-k-5

The Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk. (2017). Sight word fluency lists. https://texasldcenter.org/lesson-plans/detail/sight-word-fluency-lists

The Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk. (2020). 10 key policies and practices for reading intervention. https://www.meadowscenter.org/files/resources/10Key_ReadingIntervention_WEB-Rev2.pdf

National Assessment of Educational Progress. (2021). The 2018 NAEP oral reading fluency study. https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/subject/studies/pdf/2021025_2018_orf_study.pdf

National Reading Panel. (2002). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf

Pikulski, J., & Chard, D. (2005). Fluency: Bridge between decoding and reading comprehension. The Reading Teacher, 58(6), 510-519.

The Reading Teacher, 58(6), 510-519.

Reading A-Z. (2021). Fluency standards table. https://www.readinga-z.com/fluency/fluency-standards-table/

Roberts, J., & Burchinal, M. (2001). The complex interplay between biology and environment: Otitis media and mediating effects on early literacy development. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (pp. 232-241). The Guilford Press.

Schoenbach, R., Greenleaf, C., & Murphy, L. (2012). Reading for understanding: How Reading Apprenticeship improves disciplinary learning in secondary and college classrooms. Jossey-Bass.

The University of Texas Center for Reading and Language Arts. (2001). Essential reading strategies for the struggling reader: Activities for an accelerated reading program. https://texasldcenter.org/files/lesson-plans/Essential_Strategies_web.pdf

The University of Texas Center for Reading and Language Arts. (2002). Effective instruction for struggling readers: Research-based practices.

(2002). Effective instruction for struggling readers: Research-based practices.

The University of Texas Center for Reading and Language Arts. (2004). Effective fluency instruction and progress monitoring. https://meadowscenter.org/files/resources/Fluency_Guide.PDF

Trelease, J. (2001). The read-aloud handbook (5th ed.). Penguin Books.

How to double your reading speed in a couple of weeks / Sudo Null IT News

Speed reading is an important skill in today's fast paced world. If you want to achieve outstanding results in your career or in the study of the sciences, you will have to read a large amount of literature, both technical and fiction. In order to absorb large amounts of information, you need to be able to read quickly.

At the moment, there are a large number of techniques for studying speed reading, all of them have the right to exist. Some are based on serious scientific research, and some, on the contrary, are more like intuitive research. For each person this or that technique is suitable, it is difficult to say which one is exactly right for you.

For each person this or that technique is suitable, it is difficult to say which one is exactly right for you.

When a person is aware of the problem of low reading speed, he begins to search for information on this topic on the Internet, books, ask friends and acquaintances. After some time, if this idea is not boring, a certain understanding of speed reading techniques begins to take shape, and then it is important to start applying them.

The simplest techniques that are guaranteed to help you increase your reading speed are nothing complicated. These are just a few exercises that need to be repeated for a while. It's very similar to learning touch typing on a keyboard. You need to do exercises for 15-20 minutes a day and in a couple of weeks you can reach a fairly high speed.

Most readers encounter the classic error that consumes 30% of their reading time. This is a return to the already read text. When it seems to us that we have not caught a thought well, or have been distracted by an external thought, we go back and read a piece of text again.

Focus Training Technique

In order to cope with the return to the read text, it is necessary to keep the focus on the place of reading. To do this, you can use the technique of tracking reading. You need to take a pencil and start to drive it along the line while reading. The focus should always be on the pencil, you can not go back to the read text. At first, this is a difficult task to overcome, but over time it will get better and better.

Speed Up Technique

To increase your reading speed, you need to train this skill like any other. For speed training, you need to read very quickly. Approximately 3 times faster than the desired reading speed. For example, you read at 200 words per minute, but you want to increase this value to 300 words per minute. Then in the speed exercise you need to read 900 words per minute. No need to worry about the fact that you do not remember anything and do not understand - this is speed training. And it's important not to forget the pencil, which keeps you from going back while reading.

And it's important not to forget the pencil, which keeps you from going back while reading.

Peripheral Vision Magnification Technique

In normal reading, which we were taught in school, a person reads all the words in a line. This allows you not to miss anything written in the text. But this is not always necessary to understand the meaning of the text. If you develop peripheral reading, then you can see not one word but several at one stop of focus on the text.

There are many different techniques for training peripheral reading, the most common is the Schulte tables. Returning to peripheral vision for reading, there is a simple exercise to increase reading speed. You need to read not all the words in the line, but skip a few words at the beginning and end of the line. This greatly increases speed, but does not greatly affect understanding.

When reading at a high speed, you may encounter the effect of reading for the sake of reading, when you do not have time to assimilate information for its further application in life. To prevent this effect, it is necessary to take small pauses to comprehend the information. A few seconds after each paragraph is enough for its essence to be deposited in long-term memory.

To prevent this effect, it is necessary to take small pauses to comprehend the information. A few seconds after each paragraph is enough for its essence to be deposited in long-term memory.

If you read non-fiction or business literature, it's best to make a short summary of ideas or data from what you've read. Then you will be able to work with this information after reading the book and will not lose important data that can be applied in your field. Ideas can be presented in the form of a list or text in various editors, you can also use mind maps, which allow you to make multi-level lists that are easy to understand.

5 Ways to Increase Your Reading Speed - T&P

Google estimates that there are more than 130 million books in the world today. Not all of them really deserve attention, however, a human life is not enough to read only the masterpieces of world literature, not to mention scientific, educational and other printed materials. Those who want to read more, master speed reading.

Development of peripheral vision

One of the main tools for speed reading is peripheral or side vision. It is carried out by the peripheral areas of the retina and allows you to see and perceive a word or even a whole line instead of several letters.

The classic way to train peripheral vision is to work with the Schulte table. Such a table is a field divided into 25 squares: five horizontally and five vertically. A number is inscribed in each square, in total - from 1 to 25, in random order. The student's task is to sequentially find all the numbers in ascending or descending order, while looking exclusively at the central square.

The Schulte table can be printed on paper, but today there are dynamic online generators and downloadable computer and mobile trainings, including those with a built-in timer. Those who use extended speed reading training programs are advised to “warm up” with the Schulte table before training. If you wish, you can switch from black and white 5x5 tables to more complex versions: for example, with colored fields.

If you wish, you can switch from black and white 5x5 tables to more complex versions: for example, with colored fields.

Suppression of subvocalization

Another of the cornerstones of teaching speed reading is the rejection of subvocalization: pronouncing words in the head and micro-movements of the tongue and lips. A person is able to pronounce on average no more than 180 words per minute - and it is no coincidence that this number is the maximum in ordinary reading. However, when the speed of perception of the text increases, it becomes more difficult to pronounce words, and subvocalization begins to interfere with the development of a new skill.

There are some simple exercises to suppress mental speaking. For example, while reading, you can press your tongue to the sky, pinch the tip of a pencil with your teeth, or even just put your finger on your lips, as if saying to yourself: “Be quiet.” There are also techniques in which the pronunciation of words is “knocked off” by chaotic tapping, the sound of a metronome, or music.

Rejection of regressions

Regressions in short reading are returns to already read parts of the text. They arise when the reader is distracted by extraneous thoughts, or if the speed of assimilation of information is too high for the brain to be able to perceive all the information.

The Best Reader tutorial helps you deal with regressions. It is based on the dynamic selection of parts of the text on the page in black. It is difficult for human eyes to make orderly movements without observing anything, and this feature allows you to better focus your eyes on the necessary fragments. When reading a regular book or document on the screen of an electronic device, you can also use a simple trick that we all know from preschool days: swipe the page with your finger. It also helps to get rid of regressions by understanding that further text often makes it possible to fill in all the short information gaps that have arisen in the process of reading.

Attention concentration

Fast reading requires a high concentration of attention. To develop it and not read texts superficially, there are several exercises. For example, you can use a sheet on which the names of colors will be printed in color, but in such a way as to confuse the reader. The word "yellow" will be written in red letters, the word "red" in blue, and so on. For practice, you need to name the color of the ink, not the word that is written on the sheet, and at first it is quite difficult to do.

To develop it and not read texts superficially, there are several exercises. For example, you can use a sheet on which the names of colors will be printed in color, but in such a way as to confuse the reader. The word "yellow" will be written in red letters, the word "red" in blue, and so on. For practice, you need to name the color of the ink, not the word that is written on the sheet, and at first it is quite difficult to do.

For another exercise, all you need is a blank piece of paper and a pen. You need to focus your attention on some subject and not be distracted from it by extraneous thoughts for two or three minutes. Every time extraneous thoughts arise, it is necessary to make a note on the sheet. Over time, there should be fewer such marks, and after that they will disappear altogether.

You can also train your concentration while reading: just count the words in the text. It is important to keep counting exclusively in your mind, without helping yourself with your fingers, tapping your foot, etc. After two or three minutes, you need to stop and check yourself by counting the words without reading them. At first, the first result will differ from the second, but with regular training, the differences between them will quickly become minimal.

After two or three minutes, you need to stop and check yourself by counting the words without reading them. At first, the first result will differ from the second, but with regular training, the differences between them will quickly become minimal.

Reading whole words

The Spritz application also aims to develop peripheral vision. For training, only one line is used here, on which words with a highlighted red letter in the middle appear at different speeds. In this way, one can learn to perceive words without reading them from beginning to end, but at once in their entirety. This allows you to save up to 80% of the time that is normally spent on eye movements, and increase the reading speed to 500-1000 words per minute.

The official website of the application has a demo version of Spritz, including in Russian. You can choose from 250 to 600 wpm and other languages: English, German, Spanish, and French. In the future, the developers plan to create not only a version for websites and smartphones, but also an option for use within the interface of electronic glasses, smart watches and other compact devices, because the application requires only one line to run.

Fluency materials include (but are not limited to) letter recognition, letter-sound correspondence, word parts, words, phrases, chunked text, and connected text.

Fluency materials include (but are not limited to) letter recognition, letter-sound correspondence, word parts, words, phrases, chunked text, and connected text.