Importance of social emotional development

Social and Emotional Development in Early Learning Settings

What Is Social and Emotional Development, and Why Does It Matter?

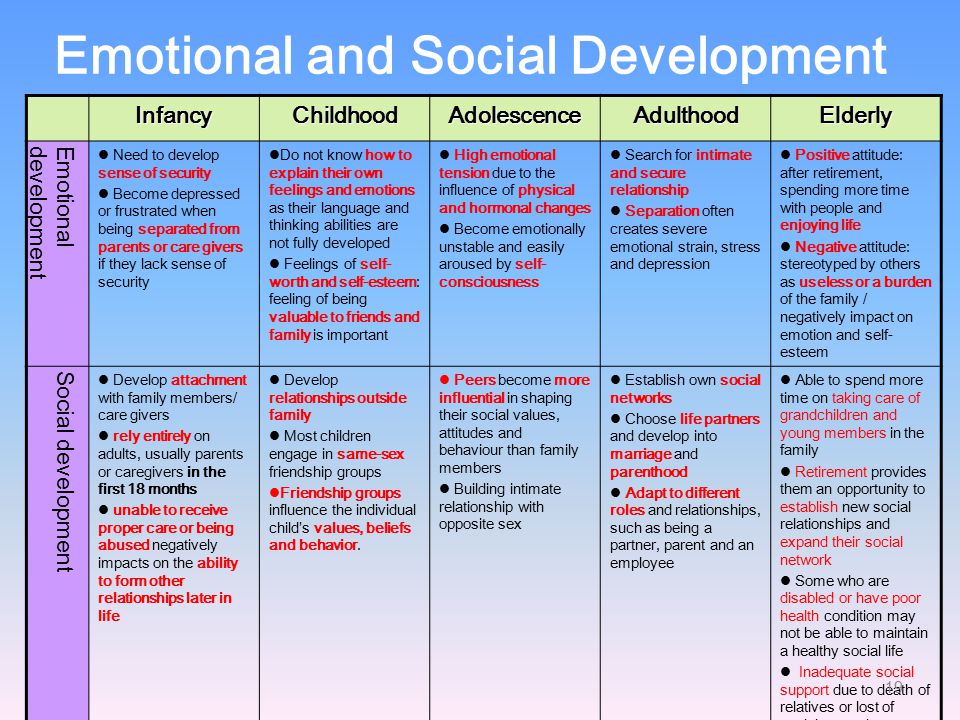

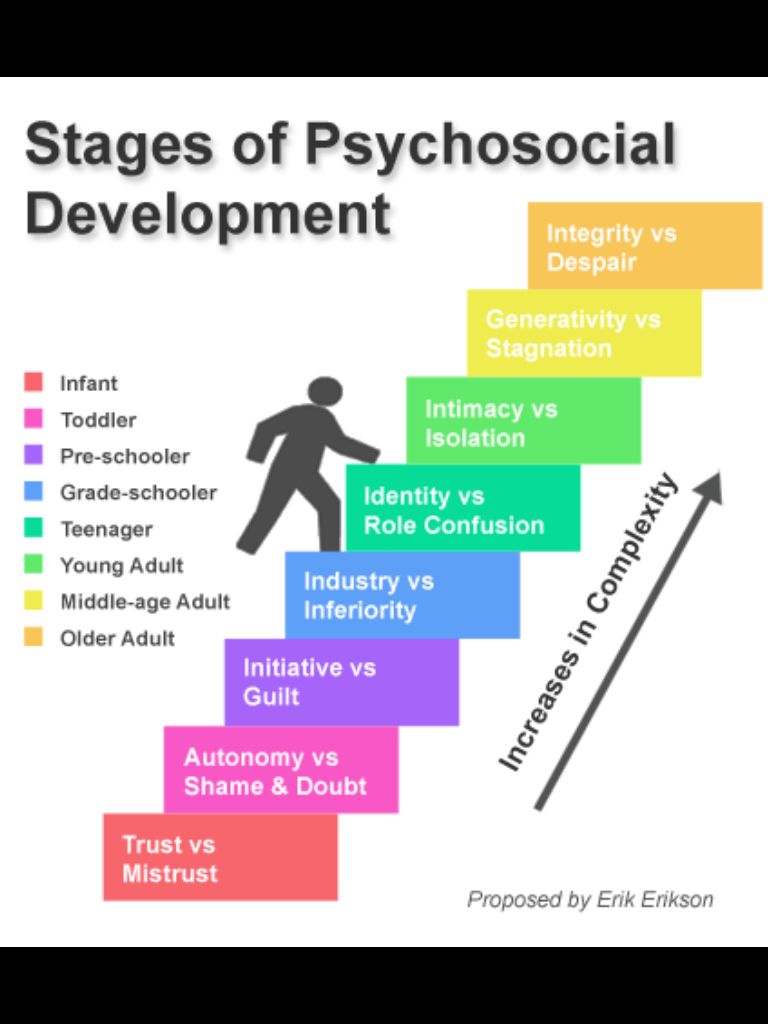

During their first few years of life, children’s brains are rapidly developing, as is their capacity to learn essential social and emotional skills. Social and emotional development in the early years, also referred to as early childhood mental health, refers to children’s emerging capacity to:

- Experience, regulate and express a range of emotions.

- Develop close, satisfying relationships with other children and adults.

- Actively explore their environment and learn.

Social and emotional development is influenced by both biology and experiences. Together, genes and experiences shape the architecture of the brain: Genes provide “instructions” for our bodies while experiences affect how and whether the instructions are carried out. Children’s early experiences consist of interactions with caregivers—parents, other family members, child care providers and teachers—and their environment.

Due to the rapid nature of brain development in early childhood, the quality of early experiences can lay either a strong or weak foundation, which will affect how children react and respond to the world around them for the rest of their life.

For most infants and young children, social and emotional development unfolds in predictable ways. They learn to develop close relationships with caregivers, soothe themselves when they are upset, share and play with others, and listen and follow directions. All these signs indicate positive early social and emotional development.

This is not the story for all children. Among those birth to age 5 who are exposed to biological, relationship-based, or environmental risk factors, at least 10% experience disruptions in their social and emotional development and consequently, mental health problems. For example, children exposed to abuse, neglect or other forms of trauma often respond biologically by producing high levels of cortisol—a stress hormone the body releases to cope with threatening situations. Prolonged periods of high stress in early childhood can cause permanent negative damage to the brain and other developing systems in the body. Children who experience toxic stress, defined as persistent activation of the stress response systems in the absence of a buffering and responsive caregiver, are at risk of poorer social, emotional and physical development. They risk serious mental health problems in childhood and later life.

Prolonged periods of high stress in early childhood can cause permanent negative damage to the brain and other developing systems in the body. Children who experience toxic stress, defined as persistent activation of the stress response systems in the absence of a buffering and responsive caregiver, are at risk of poorer social, emotional and physical development. They risk serious mental health problems in childhood and later life.

Who Plays a Role in Supporting Healthy Social and Emotional Development?

Responsive and nurturing caregivers are essential for healthy social and emotional well-being. When parents or other primary caregivers respond to an infant’s babbles, cries and gestures with eye contact, touch and words (a process known as “serve and return”), new neural pathways are connected and strengthened. These connections support healthy physical and cognitive development. Positive relationships with a caregiver can also buffer against and reduce the disruptive effects of adversity for young children.

Social and emotional learning extends beyond parent-child relationships. Family, community and culture influence social and relationship norms, values, expectations and language, as well as beliefs and attitudes related to child-rearing. Other nonparental caregivers, family members and professionals also play a role in promoting healthy social and emotional development and treating mental health problems in young children. In addition, pediatricians and other health care providers help parents understand developmental stages, promote appropriate caregiver-child interactions, screen for developmental and behavioral issues, and refer families to additional services and supports.

Over 10 million children under the age of 5 are enrolled in early learning settings such as home- and center-based child care and prekindergarten classrooms. On average, young children spend more than 30 hours with nonparental caregivers in early learning settings each week. This makes the professionals who care for and teach young children important partners in supporting social and emotional development and school readiness.

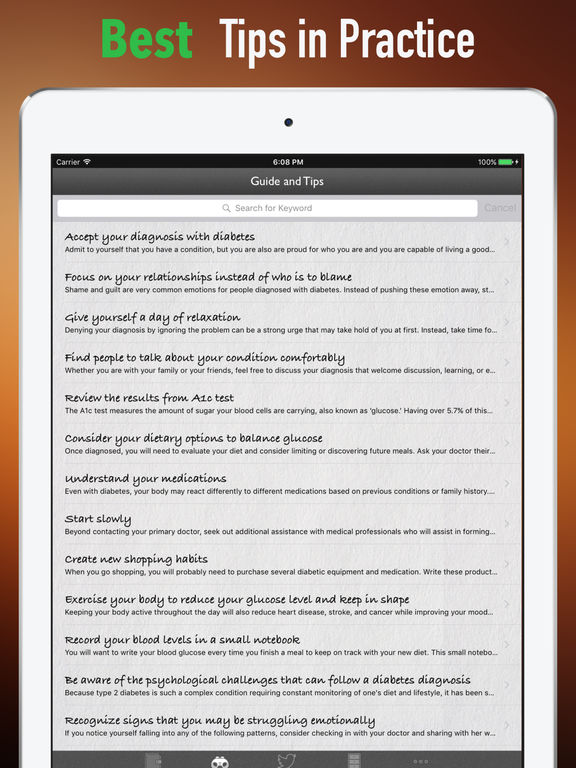

What do mental health issues look like in young children?

Young children can experience a range of mental health problems that can have a lifelong impact and be as severe as those experienced by adults. Diagnosing mental health problems in young children, however, can be challenging because they process and exhibit emotions differently than older children and adults, and changes in behavior can be temporary. Still, certain behaviors may warrant an evaluation from a mental health professional.

Birth to age 3:

- Chronic feeding or sleeping difficulties.

- Inconsolable irritability.

- Incessant crying with little ability to be consoled.

- Becoming extremely upset when left with another adult.

- Inability to adapt to new situations.

- Easily startled or alarmed by routine events.

- Inability to establish relationships with other children or adults.

- Excessive hitting, biting or pushing of other children.

- Flat effect or very withdrawn behavior.

Ages 3 to 5:

- Engages in compulsive activities.

- Throws wild, despairing tantrums.

- Withdrawn; shows little interest in social interaction.

- Displays repeated aggressive or impulsive behavior.

- Difficulty playing with others.

- Little or no communication; lack of language.

- Loss of earlier developmental achievements.

How Is Social and Emotional Development Supported in Early Learning Settings?

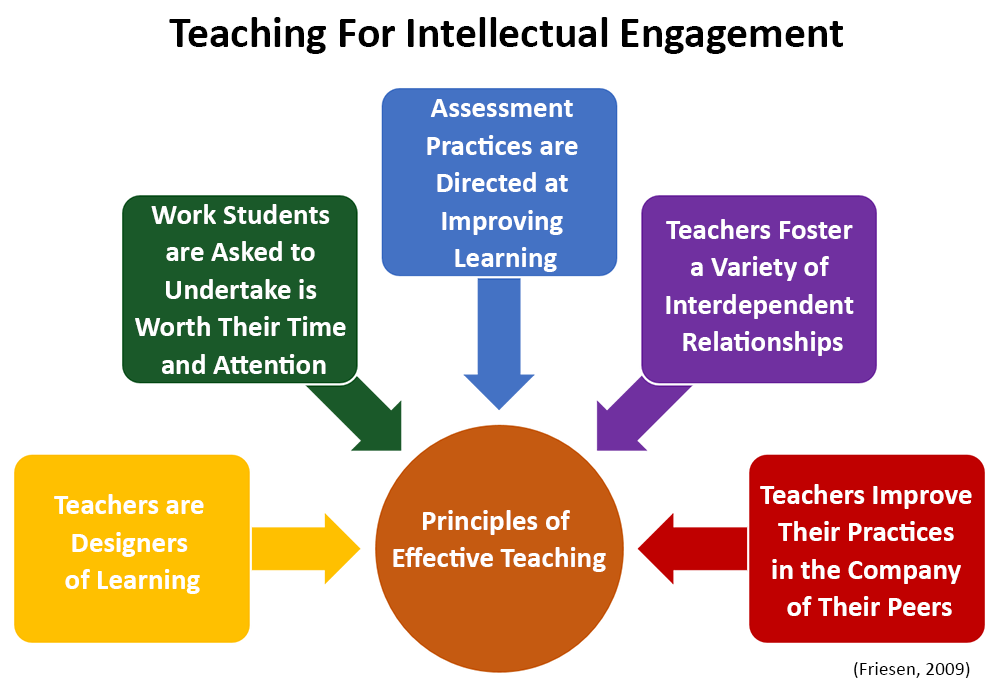

Early learning settings are rich with opportunities to build and practice social and emotional skills; however, the quality of these settings affects the degree to which a child’s social and emotional development is supported. In high-quality settings, children benefit from “frequent, warm and stimulating” interactions with caregivers who are attentive and able to individualize instruction based on children’s needs and strengths. Early educators in high-quality settings are trained in early childhood education and tend to be less controlling and restrictive in their approach to classroom management.

Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation

Infant and early childhood mental health consultation (IECMHC) is an evidence-based strategy to support healthy social and emotional development and “prevent, identify, and reduce the impact of mental health problems among young children and their families,” according to the Center for Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation. IECMH consultants help build the capacity of the adults in young children’s lives to support healthy social and emotional development at home and in early learning settings. IECMH consultants have master’s degrees and are licensed mental health professionals who provide indirect, prevention-based services. They partner with families to assess concerns, assist with implementing positive behavioral supports, and connect families to other services and supports. Within early learning settings, IECMH consultants provide classroom-focused interventions that target all children, home-based interventions for more high-risk children, and referrals for those children who need more specialized services. Additionally, IECMH consultants support early care and education professionals by providing reflective supervision, coaching, training and case consultation.

Additionally, IECMH consultants support early care and education professionals by providing reflective supervision, coaching, training and case consultation.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) Center of Excellence for Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation emphasizes the field’s role in promoting equity and reducing disparities in access to resources and outcomes for young children. Equity, according to SAMHSA’s IECMHC Toolbox, is “the quality of being fair, unbiased, and just.” Equity is essential to reducing disproportionalities among young children of color in suspensions and expulsions in early learning settings. IECMH consultants partner with early care and education professionals to “reflect on their own experiences, biases, and fears—and then move beyond them to see each young child as an individual within a unique family and community context.” There is growing evidence that access to IECMHC reduces the occurrence of suspensions and expulsions for young children.

Licensure and accreditation, well-trained caregivers, low staff-child ratios and parent involvement are generally considered to be fundamental to high-quality care and education. Such elements not only promote strong, secure relationships and positive interactions between caregiver and child, but also improve attention to children’s interest, problem-solving, language development, social skills and physical development.

High-quality early learning opportunities can also reduce the risk of children experiencing poor mental health. Research shows it can mitigate the effects of poverty, maternal depression and other risk factors. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, high-quality child care helps build resilience among at-risk children, partly due to the relationships they form with caregivers. When children perceive at least one supportive adult in their life, they are less likely to experience toxic stress and suffer the detrimental effects of adverse experiences.

Well-trained early care and education professionals are critical to supporting social and emotional competence in young children. First and foremost, they build nurturing and responsive relationships with the children in their care and model respectful and appropriate behavior. They weave social and emotional skill-building into day-to-day activities and implement targeted curriculum and lessons with books, music, games and group discussions.

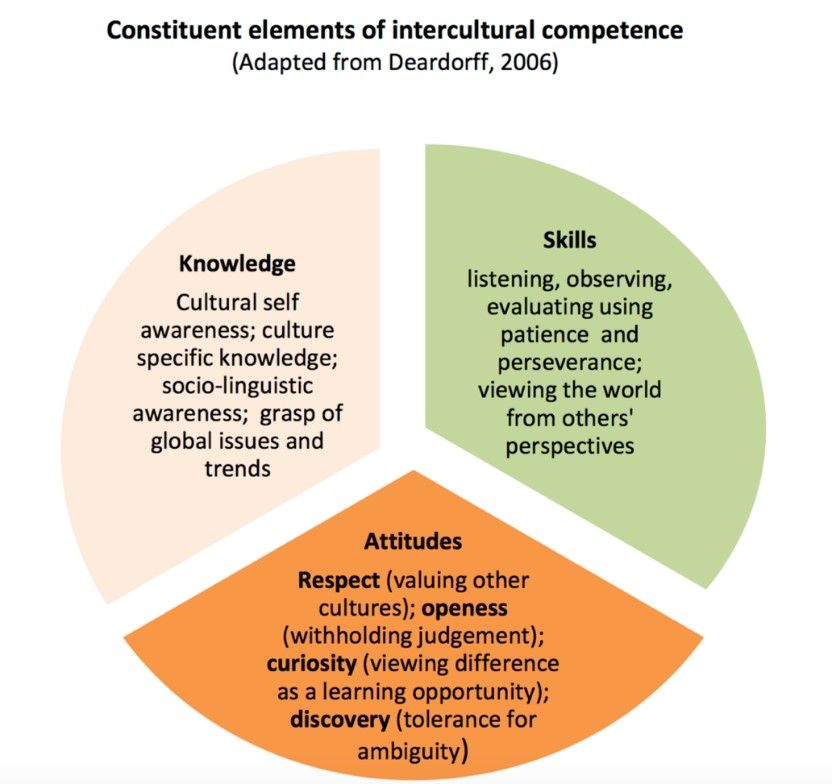

Effective early care and education professionals consider and support the individual needs of each child within the context of their family and culture. Head Start, the federally funded, locally implemented birth-to-5 program for low-income children, emphasizes that “children’s learning is enhanced when their culture is respected and reflected in all aspects” of an early learning program. Early childhood programs implementing culturally reflective policies and practices may look different depending on the setting, but at their core, they are learner-focused, promote a positive cultural and individual identity, and engage all children from unique cultural and/or linguistic backgrounds. Cultural awareness is key for early care and education professionals in forming strong relationships with children and families.

Cultural awareness is key for early care and education professionals in forming strong relationships with children and families.

Early care and education professionals are also critical to identifying children who face barriers to healthy social and emotional development and helping families obtain the support they need. They sometimes partner with an early childhood mental health consultant to address challenging behaviors and develop behavior support plans.

An increasing number of early learning settings are implementing Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support (PBIS) frameworks. The frameworks are designed to equip early care and education professionals with the skills and tools they need to support positive social and emotional development and address challenging behavior. A program-wide PBIS does not prescribe a specific curriculum. Instead, it includes a series of practices, interventions and implementation supports that are available across the system. One such framework, the Pyramid Model for Supporting Social Emotional Competence in Infants and Young Children (Pyramid Model), is specifically designed for programs serving infants and toddlers. Twenty-five states have established statewide coalitions and leadership teams to implement the Pyramid Model (often housed within a state’s human services or education department). The Pyramid Model organizes evidence-based practices into three progressively intensive tiers: universal supports for the wellness of all children, targeted services for those who need more support, and intensive services for those most in need. The model emphasizes how essential early care and education professionals are to the social and emotional well-being of young children by positioning “effective workforce” as the foundation.

Twenty-five states have established statewide coalitions and leadership teams to implement the Pyramid Model (often housed within a state’s human services or education department). The Pyramid Model organizes evidence-based practices into three progressively intensive tiers: universal supports for the wellness of all children, targeted services for those who need more support, and intensive services for those most in need. The model emphasizes how essential early care and education professionals are to the social and emotional well-being of young children by positioning “effective workforce” as the foundation.

How Prepared Are Early Care and Education Professionals to Care for Children With Challenging Behaviors?

Despite the importance of their role, many early care and education professionals report not feeling adequately trained to respond to challenging behaviors or to support children at risk of mental health issues. A national survey of the early care and education workforce revealed just 20% of respondents received training on supporting social and emotional growth in the past year. When asked what types of support would help them better address the needs of children with challenging behavior, professionals in Maine most frequently selected additional training (61%) and greater access to early childhood behavioral specialists (57%). In a similar survey in Virginia, respondents identified access to specialists (63%), additional supports for families (54%) and increased training for staff (52%) as necessary to improving outcomes for children.

When asked what types of support would help them better address the needs of children with challenging behavior, professionals in Maine most frequently selected additional training (61%) and greater access to early childhood behavioral specialists (57%). In a similar survey in Virginia, respondents identified access to specialists (63%), additional supports for families (54%) and increased training for staff (52%) as necessary to improving outcomes for children.

Implicit Bias in Early Learning Settings

In a study by researchers at Yale University, early care and education professionals were instructed to look for challenging behaviors in a video of an early learning classroom where none was present. Researchers used technology to track eye movements and found that when challenging behaviors were expected, teachers tended to observe the black children more closely, especially the black boys.

Another component of the study found that when teachers were provided additional information on a child’s family and background, and when the teacher’s race matched that of the child, teachers tended to lower the severity rating of the child’s behavior. Researchers concluded by calling for greater connections between early care and education professionals and parents, as well as increased training to address biases and increase empathy.

Researchers concluded by calling for greater connections between early care and education professionals and parents, as well as increased training to address biases and increase empathy.

Survey participants in both Maine and Virginia were also asked about the effects of challenging behaviors in the classroom. Concerns included the ability to attend to other children and ensuring the safety and ability of other children to learn. Respondents also noted the negative effect challenging behaviors have on their own well-being.

Without adequate training and supports to handle these stressful situations, early care and education professionals—among whom depression is not uncommon—burn out and leave the profession. Extremely low wages further contribute to their stress. At an average annual salary of just over $22,000, nearly half of the early care and education workforce is enrolled in at least one public support program. These include the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Researchers have found that stress negatively affects early care and education professionals’ ability to provide positive, high-quality environments and is the primary reason they leave the field. Bringing the problem full circle, high turnover among early care and education professionals disrupts the relationships and attachments formed with the children they care for and is linked to poorer developmental outcomes for early learners.

Researchers have found that stress negatively affects early care and education professionals’ ability to provide positive, high-quality environments and is the primary reason they leave the field. Bringing the problem full circle, high turnover among early care and education professionals disrupts the relationships and attachments formed with the children they care for and is linked to poorer developmental outcomes for early learners.

Furthermore, early care and education professionals who lack training may be unprepared to distinguish concerning behaviors from those that are developmentally appropriate. Misinterpreting or mischaracterizing behaviors may lead to more punitive discipline and failure to provide appropriate supports. Underprepared professionals are more likely to over-identify children, especially children of color, for special education, disciplinary action and expulsions. Suspensions and expulsions are more likely to occur in early learning settings that have high student-adult ratios, private ownership, extended hours, limited access to early childhood behavioral specialists, and teachers who report high levels of stress.

Suspension and expulsion in early learning settings

Data collected in recent years by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights has shined a spotlight on how common suspensions and expulsions are in early learning settings. In fact, expulsion rates among preschoolers are three times higher than those of K-12 students. Stark disparities in suspension and expulsion rates among young children based on race and gender led researchers to question the effect of implicit bias, or the “automatic and unconscious stereotypes that drive people to behave and make decisions in certain ways. Black children, who comprise just 19% of preschool enrollment, make up 47% of preschoolers who are suspended. Research shows students of color are more harshly disciplined for the same behaviors exhibited by their white peers. Furthermore, 75% of expelled preschoolers are boys, with black boys being suspended or expelled the most often. The consequences for young children who are suspended or expelled can be significant and long-lasting. The same children are more likely to be suspended or expelled again in later years and to drop out of high school, fail a grade or be incarcerated.

The same children are more likely to be suspended or expelled again in later years and to drop out of high school, fail a grade or be incarcerated.

In 2016, U.S. departments of Health and Human Services and Education issued a policy statement and recommendations aimed at preventing and severely limiting suspensions and expulsions of young children. The departments recommended that early learning programs take the following steps:

- Improve the workforce’s skill set and capacity to support social and emotional development, address challenging behaviors appropriately, and form supportive and nurturing relationships with children and their families.

- Provide training to deepen the workforce’s understanding of cultures and diversity, practice self-reflective strategies and correct biases.

- Increase access to behavioral specialists (including IEMCH consultants).

- Promote the health and well-being of the workforce with reasonable work hours, breaks and access to supports, such as social or mental health services.

The policy statement also made recommendations directly to states, including enacting state policies severely limiting the use of suspensions and expulsions across all early learning settings, collecting data on the use of exclusionary discipline and setting goals for its reduction. It also recommended investing in workforce training and implementing policies to increase quality in early learning settings.

How Are State Policymakers Promoting Healthy Social and Emotional Development in Early Learners?

Well-trained and supported early care and education professionals are critical to reducing the occurrence of suspensions and expulsions in the early years, providing high-quality early learning experiences and supporting social and emotional well-being in young children. Below are actions policymakers across the country are taking to help children, families and early care and education professionals acquire the skills and resources they need to thrive.

Investing in targeted training and professional development for early care and education professionals

- Most states include social and emotional development in their Early Learning Guidelines for early care and education professionals.

- California provides training and coaching on trauma-informed care for in-home child care providers serving children in the foster care system.

- Alaska requires programs at levels 4 and 5 in the state’s Quality Rating Improvement System (QRIS) to participate in trainings specific to trauma and adversity.

- Vermont’s Early Multi-Tiered System of Supports framework includes evidence-based practices and trainings and is embedded in the state’s QRIS.

Addressing compensation and workplace conditions in early learning settings

- Five states fund wage supplements through the Child Care WAGE$ Program, a stipend available through the Child Care Services Association, in which early care and education professionals are placed on a “salary supplement scale.” The scale rewards workers for obtaining higher levels of education and for remaining in the same child care setting. Wisconsin and Georgia have their own wage supplement programs.

- Colorado, Louisiana and Nebraska passed legislation to provide tax credits for early care and education professionals who meet certain education or training requirements.

- Twenty-two states include salary scales and/or benefits (e.g., paid leave and health insurance) as a quality indicator for center-based child care providers in their QRIS.

- Thirteen states include paid time for professional development as a marker of quality in their state’s QRIS for center-based child care providers.

BehaviorHelp in Arkansas

In 2016, Arkansas extended its prohibition of suspension and expulsion in state-funded prekindergarten classrooms to include nearly 1,000 child care providers serving families with child care subsidies.

To support early care and education professionals with implementing the new policy, the state established BehaviorHelp, a program that provides individual support for addressing challenging behaviors in young children. Early care and education professionals, parents and child welfare case workers complete an online form detailing their issue. Behavioral health specialists then follow up with a phone consultation, classroom observation, training related to individual support plans for educators and parents, and referrals to additional services.

Data collected during the program’s first two years revealed that over half of the children exhibiting challenging behaviors had experienced difficult or traumatic events, such as abuse or neglect, divorce or parent incarceration. A survey of users found that 81% felt better able to address their concerns because of the support they received from BehaviorHelp. Users also reported a significant decline in the frequency of challenging behaviors.

Improving access to infant and early childhood mental health consultation

- Louisiana and North Carolina provide access to early childhood mental health consultants for child care providers through their state’s QRIS.

- Virginia funds a full-time coordinator to support a comprehensive IECMH system, including a series of trainings and an IECMH endorsement for practitioners.

- Connecticut’s statewide IECMH program provides universal access to consultants for all early childhood programs in the state.

- Early care and education professionals in Arkansas (see text box on page 7) and Ohio can receive individualized consultations from an early childhood behavioral specialist through a hotline.

Arizona’s Birth to Five hotline is available to parents as well as early care and education professionals.

Arizona’s Birth to Five hotline is available to parents as well as early care and education professionals.

Reducing suspensions and expulsions in early learning settings

- Sixteen states and the District of Columbia limit or prohibit the use of suspensions and expulsions in lower grades, including prekindergarten classrooms.

- Legislators in Washington directed its Department of Children, Youth, and Families to develop a five-year strategy to expand training and awareness in trauma identification, provide positive behavior supports in early settings, and reduce the use of exclusionary discipline by 50%.

- Colorado’s state child care rules require providers to “outline how decisions are made and what steps are taken prior to a suspension, expulsion, or request to withdraw a child from care.” The rules further require that child care providers adopt policies to 1) provide individualized social and emotional intervention supports for children who need them, 2) implement a team-based positive behavior support plan aimed at reducing challenging behavior, suspensions and expulsions, and 3) improve access to early childhood mental health consultants.

Learning about the mental health needs of young children

- Georgia lawmakers established the Infant and Toddler Social-Emotional Health Study Committee to study the availability of services and make recommendations.

- The Oklahoma Legislature established a task force on trauma-informed care to recommend options and strategies for implementing a coordinated approach to preventing trauma in children, as well as interventions for children and families who are at risk of experiencing trauma.

Conclusion | Additional Resources

Early childhood is a critical window of development for learning social and emotional skills. The quality of experiences and relationships during this time can have life-long implications. For children who face barriers to healthy development, the stakes are even higher. Nurturing the social and emotional development of all young children, so they are ready to succeed in school and beyond, depends on strong partnerships between parents and their out-of-home caregivers. State policymakers are taking steps to ensure young children are supported in early learning settings by investing in the training and well-being of the early care and education workforce, restricting the use of suspensions and expulsions, improving access to early childhood mental health specialists, and exploring additional policies to support the mental health needs of young children and their families.

State policymakers are taking steps to ensure young children are supported in early learning settings by investing in the training and well-being of the early care and education workforce, restricting the use of suspensions and expulsions, improving access to early childhood mental health specialists, and exploring additional policies to support the mental health needs of young children and their families.

Additional Resources

- "School Discipline in Preschool Through Grade 3," NCSL LegisBrief

- "Building a Comprehensive State Policy Strategy to Prevent Expulsion from Early Learning Settings,” Administration of Children and Families, Office of Child Care

- Center for Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation

- "Social and Emotional Learning," NCSL

Social-Emotional Development: An Introduction | Virtual Lab School

Objectives

- Define social-emotional development and discuss its importance in our lives.

- Reflect on your own ideas and experiences associated with social-emotional development.

- Discuss how social-emotional learning promotes development in young children.

Learn

Know

Think back over the past couple of days. What are some emotions that you felt? Do you recall feeling happy, sad, angry, fearful, or upset in response to receiving news or having a conversation or argument? Now consider how your feelings at the time might have affected some of your social interactions or relationships with others.

Emotions affect who we are and they impact our attention, memory, and learning; our ability to form relationships; and our physical and mental health. They also influence our behaviors, actions, and interactions with others. Think about times you were happy. How did those feelings affect your behavior and, in turn, your interactions? Now, consider times when you were sad, angry, or upset. How did those feelings influence your behaviors and interactions?

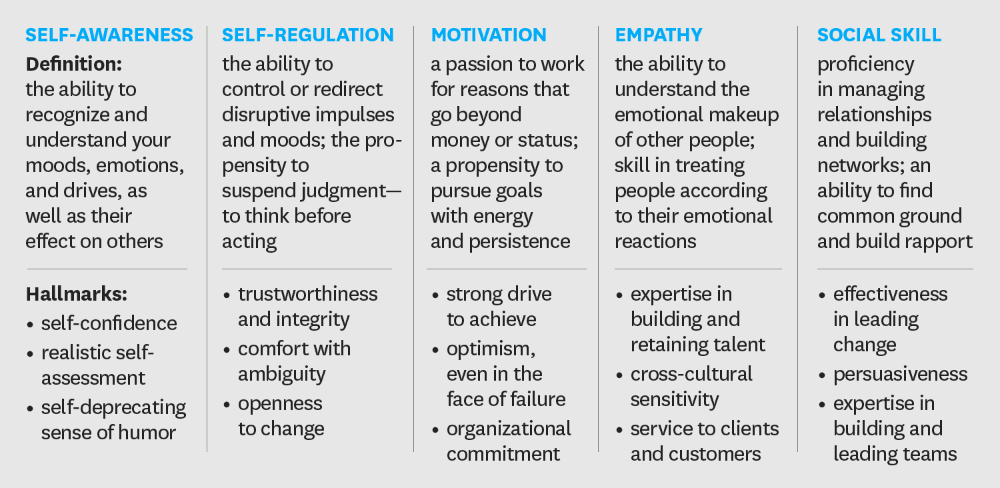

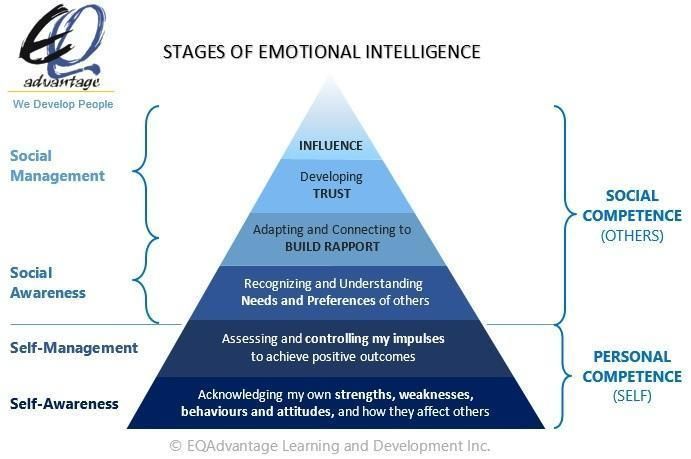

Labeling, identifying, and managing emotions are essential skills for meaningful and successful participation in life experiences, both in our professional and personal lives. Emotional intelligence is a term used to describe the ability to understand your own emotions and use them to guide your thinking and actions. Developing emotional intelligence allows you to manage your emotions effectively and avoid frustration and disappointment. Emotions can strongly influence our relationships with others and our overall quality of life.

Emotional intelligence is a term used to describe the ability to understand your own emotions and use them to guide your thinking and actions. Developing emotional intelligence allows you to manage your emotions effectively and avoid frustration and disappointment. Emotions can strongly influence our relationships with others and our overall quality of life.

What is Social-Emotional Development?

Children begin developing social-emotional skills at birth. Research indicates that children are born ready to connect with other people in their environment. When a child’s emotional and physical needs are met, learning pathways to the brain are formed, which lead to learning in all developmental domains. Emotional signals, such as smiling, crying, or demonstrating interest and attention, strongly influence the behaviors of others. Similarly, the emotional reactions of others affect children’s social behaviors. As children mature and develop, their social-emotional skills become less centered on having their own needs met by their caregivers and more focused on participating in routines and enjoying experiences with friends and caregivers.

The early childhood years are a critical time for the formation of positive feelings toward oneself, others, and the larger world. Young children develop and learn in the context of relationships and when they are encouraged, nurtured, and accepted by adults and peers, they are more likely to be well adjusted. On the contrary, children who are neglected, rejected, or abused are at risk for social and mental health challenges.

Supporting the social and emotional health of preschoolers is important because:

- Early relationships set the stage for healthy or unhealthy brain development

- Poor social, emotional, and behavioral development predicts early school failure, which in turn, predicts later school failure

- Early intervention can reduce the need for later, higher-cost interventions

- Supporting children early in life will allow them to give back to society later

Take a moment to think about what social-emotional development means to you. What comes to mind? How do you explain social-emotional development to others? Below, we highlight 5 key competencies of social-emotional development. It is important to recognize that preschoolers are still establishing these abilities. We should not expect preschoolers to have advanced social awareness or decision-making skills, instead know that they are on a path to acquiring these skills, with guidance and support from families and teachers.

What comes to mind? How do you explain social-emotional development to others? Below, we highlight 5 key competencies of social-emotional development. It is important to recognize that preschoolers are still establishing these abilities. We should not expect preschoolers to have advanced social awareness or decision-making skills, instead know that they are on a path to acquiring these skills, with guidance and support from families and teachers.

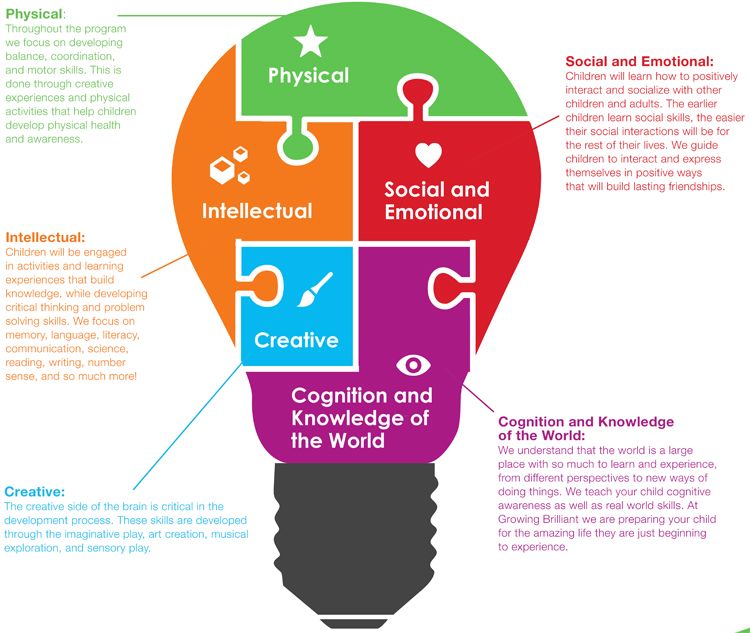

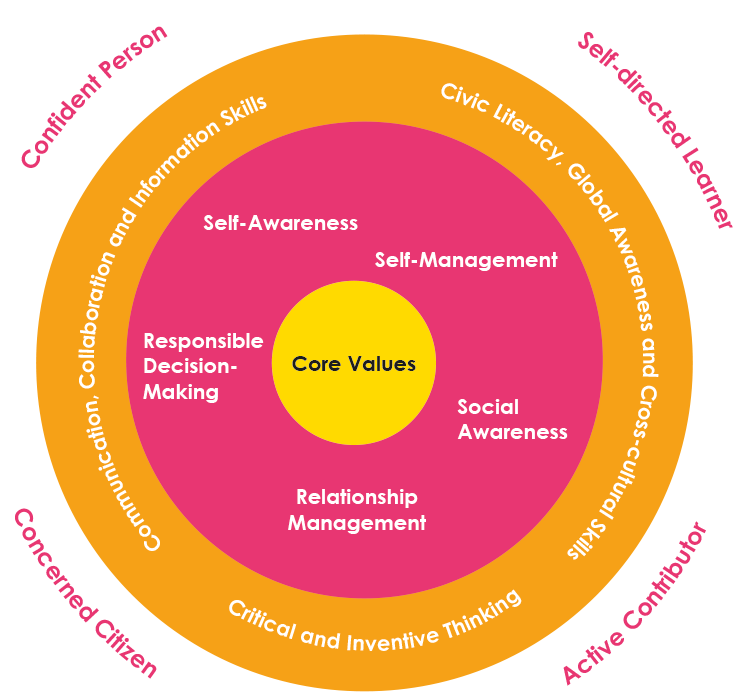

According to the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), social and emotional development (also called social-emotional learning) consists of the following five core components:

Self-awareness:

This is the ability to accurately recognize one’s emotions, thoughts and their influence on behavior. This includes accurately assessing one’s strengths and limitations and possessing a well-grounded sense of confidence and optimism.

We see evidence of this when a preschooler can recognize and identify their own emotions. For example, a preschooler may manage their negative emotions by telling a teacher, “I am sad because I do not want to share my toy from home.” Preschoolers also demonstrate self-awareness when they use props, such as dolls, to identify and express their emotions.

For example, a preschooler may manage their negative emotions by telling a teacher, “I am sad because I do not want to share my toy from home.” Preschoolers also demonstrate self-awareness when they use props, such as dolls, to identify and express their emotions.

Examples of questions someone who is self-aware may ask:

- What are my thoughts and feelings?

- What causes those thoughts and feelings?

- How can I express my thoughts and feelings respectfully?

Self-management:

This is the ability to control one’s emotions, thoughts, and behaviors effectively in different situations. This includes managing stress, controlling impulses, motivating oneself, and setting and working toward achieving personal and academic goals.

When preschoolers are able to wait their turn, accept reminders about free play ending and clean up, and follow routines with simple reminders, these are examples of self-management.

Examples of questions someone who has good self-management may ask:

- What different responses can I have to an event?

- How can I respond to an event as effectively as possible?

Social awareness:

This is the ability to take the perspective of and empathize with others from diverse backgrounds and cultures, to understand social norms for behavior, and to recognize family, school and community resources and supports.

A preschooler is developing their social awareness when they express sympathy for a friend who is feeling sad, help another child rebuild their block town when it gets knocked over, or offer to help a peer who is upset after spilling milk. Preschoolers who express concern for the needs of others are demonstrating their social awareness skills.

Examples of questions someone who has good social awareness may ask:

- How can I better understand other people’s thoughts and feelings?

- How can I better understand why people feel and think the way they do?

Relationship skills:

This is the ability to establish and maintain healthy and rewarding relationships with diverse individuals and groups. This includes clear communication, active listening, cooperation, avoiding social pressure, conflict resolution, and obtaining or providing help when needed.

Preschoolers demonstrate their developing relationship skills by seeking support from a teacher when a peer conflict starts or making suggestions to peers with ways they can work together. Preschoolers also use words rather than actions to express strong feelings (e.g., “I don’t like it when you push.”)

Preschoolers also use words rather than actions to express strong feelings (e.g., “I don’t like it when you push.”)

Examples of questions someone who has good relationship skills may ask:

- What actions can I take in to improve my interactions with other people?

- How can I communicate my expectations to others?

- What can I say or do better to understand the expectations others have for me?

Responsible decision-making:

This is the ability to make constructive and respectful choices about personal behavior and social interactions. This includes consideration of ethical standards, safety concerns, social norms, the realistic evaluation of consequences of various actions, and the well-being of self and others.

When a preschooler waits until another child is done playing on a swing and then uses it, offers to share their paint, or holds a bubble wand so a peer can blow bubbles, they are displaying responsible decision-making.

Examples of questions someone who is a responsible decision-maker may ask:

- What consequences will my actions have on myself and others?

- How do my choices align with my values?

- How can I solve problems effectively?

The Role of Family in Social-Emotional Development

Children develop social-emotional skills in the context of their relationships with their primary caregivers and within their families and cultures. Consider how diverse our society is. You can imagine that this diversity is also expressed in the ways families from different cultures teach children to manage emotions, socialize, and engage with others. For example, in some cultures, children are taught to avoid eye contact. For other cultures, eye contact is an essential component of social interaction. Culture also affects parenting practices and how individuals are taught to deal with emotions, including handling stress and coping with adversity.

Consider how diverse our society is. You can imagine that this diversity is also expressed in the ways families from different cultures teach children to manage emotions, socialize, and engage with others. For example, in some cultures, children are taught to avoid eye contact. For other cultures, eye contact is an essential component of social interaction. Culture also affects parenting practices and how individuals are taught to deal with emotions, including handling stress and coping with adversity.

Family priorities affect social-emotional competence. For example, some families might place a high value on talking about emotions and expressing them as they occur, whereas other families may value doing the opposite. As a preschool teacher, you must be sensitive and respectful of individual differences in social-emotional development when engaging with children in your care and their families.

What Does Social-Emotional Development Look Like in Preschoolers?

During the preschool years, children learn to take turns, share toys and materials, play near each other, talk with peers, and talk about their feelings and the feelings of others. They also begin to follow classroom and home routines independently. Children learn social skills from watching others interact and through conversations with adults and peers. As a preschool teacher, you can play a significant role in promoting children’s social-emotional skills if you engage them early on in meaningful experiences with peers and other adults in your classroom and program.

They also begin to follow classroom and home routines independently. Children learn social skills from watching others interact and through conversations with adults and peers. As a preschool teacher, you can play a significant role in promoting children’s social-emotional skills if you engage them early on in meaningful experiences with peers and other adults in your classroom and program.

The following are examples of social-emotional skills preschool children engage in daily:

- Singing along with peers during circle, center, or book time

- Holding hands while walking down the hall during transitions

- Hugging a friend who is sad

- Sharing a snack with a friend, sibling, or caregiver

- Taking turns while building a tower of blocks with a friend

- Passing out silverware to all children while preparing for lunch

- Making statements such as “I made this all by myself!” when accomplishing tasks

- Giving a friend a toy or object that they asked to use

- Telling a teacher they miss their Mom or Dad

- Getting ready for bath time when a parent says it is time to take a bath

- Talking on the phone with a family member who lives far away

- Telling a family member or teacher that they are sad about something

- Roleplaying experiences such as going grocery shopping, visiting the doctor, or family roles

- Waiting in line for a turn at the drinking fountain

- Putting a stuffed animal down for a nap and telling peers to “be quiet, because my pet is taking a nap”

- Completing a difficult puzzle

Social-Emotional Growth and Young Children’s Development

Social-emotional health affects a person’s overall development and capacity to learn. Research suggests that children who have positive social-emotional health tend to be happier, show greater interest in learning, have a more positive attitude toward school, are more likely to participate in classroom activities, and demonstrate higher academic performance than less socially and emotionally competent peers. Therefore, children’s social-emotional health is equally as important as their physical health.

Research suggests that children who have positive social-emotional health tend to be happier, show greater interest in learning, have a more positive attitude toward school, are more likely to participate in classroom activities, and demonstrate higher academic performance than less socially and emotionally competent peers. Therefore, children’s social-emotional health is equally as important as their physical health.

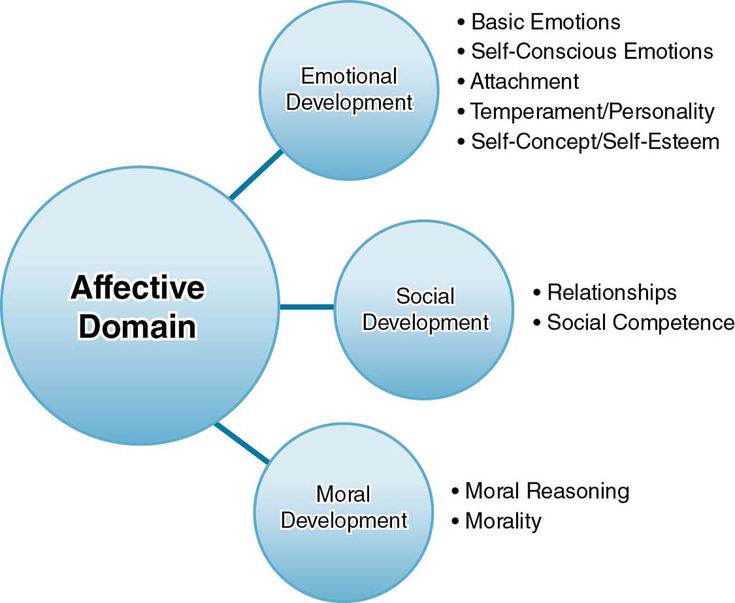

Since social-emotional development affects young children’s growth later in life, social-emotional skills are central to children’s physical well-being, self-expression, learning, and development of relationships. Consider the impact social emotional development has on various areas of development:

- Learning to read involves regulating emotions and activity levels and requires the child to sit and attend to a task

- Learning to walk, swim, run, or ride a bike involves regulating activity level, attending to adult directions, focusing on muscle control, and controlling impulses.

- Learning to communicate involves using socially appropriate strategies for interaction.

- Learning self-help skills involves following directions, controlling emotions to complete challenging tasks, and knowing when and how to ask for help.

- Being successful in school involves understanding classroom expectations and participating in large- and small-group activities with peers.

Success in school is strongly linked to early positive social-emotional development, thus, it is critical to foster social-emotional learning during the early childhood years.

See

Video not availableWatch this video to learn about the importance of social-emotional development for children’s lives.Do

As a preschool teacher, it is your responsibility to provide developmentally appropriate experiences and activities that meet each child’s needs. As you plan and implement your program, you must remember you are setting the foundation for children’s growth and success. When fostering young children’s healthy social-emotional development, consider the following:

When fostering young children’s healthy social-emotional development, consider the following:

| Plan meaningful, fun experiences for the children in your care while acknowledging their individual differences and backgrounds. | |

| Embed opportunities for social-emotional learning throughout your school day and provide children with multiple opportunities to express themselves in various ways. | |

| Acknowledge, validate, and respond to children’s needs, emotions, and concerns. | |

| Be sensitive to children’s unique life circumstances that may influence their social-emotional development. | |

| Arrange your environment in ways that promote children’s social interactions and relationship building with peers and adults in the room. | |

| Use natural classroom events and relationships and interactions with peers and adults as opportunities to talk with children about emotions. | |

| Acknowledge that, like in any other area of development, individual differences exist in children’s social-emotional development. | |

| Reach out to the families of children in your program and learn about their preferred methods of interaction with their children. |

Completing this Course

For more information on what to expect in this course, the Social & Emotional Development Competency Reflection, and a list of the accompanying Learn, Explore and Apply resources and activities offered throughout the lessons, visit the Preschool Social & Emotional Development Course Guide.

Please note the References & Resources section at the end of each lesson outlines reference sources and resources to find additional information on the topics covered. As you complete lessons, you are not expected to review all the online references available. However, you are welcome to explore the resources further if you have interest, or at the request of your trainer, coach, or administrator.

Explore

How do you define social-emotional development? What are your views about your own abilities to build relationships? Download and print the Thinking About Social Emotional Development handout. Take a few minutes to read and respond to the questions. Then, share and discuss your responses with a trainer, coach, or administrator.

Thinking about Social Emotional Development

Complete the activity to further your understanding of social-emotional development

Required: Complete and review this document with your trainer, supervisor, or administrator

Apply

A great deal of research suggests the importance of social-emotional learning for children’s development. Use the Social-Emotional Competence of Children handout, a resource from the Center for the Study of Social Policy to learn more about the importance of social-emotional competence for children’s lives.

Then, re-review the core competence areas from the Social and Emotional Learning Framework developed by The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). Use the information in the SEL Framework activity to guide your practice as you support preschooler’s social-emotional development.

Glossary

Demonstrate

Finish this statement: “Social-Emotional skills begin developing in the ____ years.”infant

preschool

school-age

adult

A parent asks if social-emotional skills affect children’s development in other areas. What is an appropriate response?“No, social-emotional skills do not impact other areas of a child’s development. ”

”

“Yes, social-emotional skills determine a child’s academic success.”

“Social-emotional skills are really not all that important in a child’s development.”

“Yes, studies have shown that social-emotional skills can impact other areas of a child’s development.”

Which of the following is an example of a preschool child practicing their social-emotional skills?Cutting in line for a drink of water

Pushing a peer when they get mad

Singing with friends at circle time

Knocking over a tower of blocks built by a peer and not acknowledging their action

References & Resources

Berk, L. E. (2013). Child development (9th ed). Pearson.

Bohart, H. & Procopio, R. (2017). Spotlight on young children: Social and emotional development. The National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Brackett, M.A., S.E. Rivers, & P. Salovey. (2011). Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 5 (1): 88–103.

Social and Personality Psychology Compass 5 (1): 88–103.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2020). SEL: What are the core competence areas and where are they promoted? https://casel.org/sel-framework/

Denham, S. A., & Brown, C. (2010). “Plays nice with others”: social-emotional learning and academic success. Early Education and Development, 21, 652-680.

Division of Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children. (2014, April 14). DEC recommended practices. https://d4ab05f7-6074-4ec9-998a-232c5d918236.filesusr.com/ugd/95f212_12c3bc4467b5415aa2e76e9fded1ab30.pdf

Funk, S. & Ho, J. (2018). Promoting young children’s social and emotional health. Young Children, 73(1). https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/mar2018/promoting-social-and-emotional-health

National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (2012). Early Childhood Generalist Standards for teachers of ages 3-8 (3rd ed. ).

).

Trawick-Smith, J. W. (2013). Early childhood development: A multicultural perspective (6th ed.). Pearson.

Socio-emotional

Socio-emotional development – this is a purposeful development in a child of a conscious emotional-positive attitude towards himself, other people, the world around him, the ability to deal with opinions and desires with emotional states , as well as the development of socially significant skills of behavior in society.

The formation of these qualities by the end of preschool age will provide the basis for the further development of such significant personal formations as: the ability for creative self-expression, self-realization and self-development. Ultimately, ensuring the social and emotional well-being of a person is the formation of a sense of self-confidence, harmonious interaction with society and life success.

so that every child can:

- find their niche and realize social needs and creative opportunities;

- felt coziness, comfort and his personal significance for all the people around him.

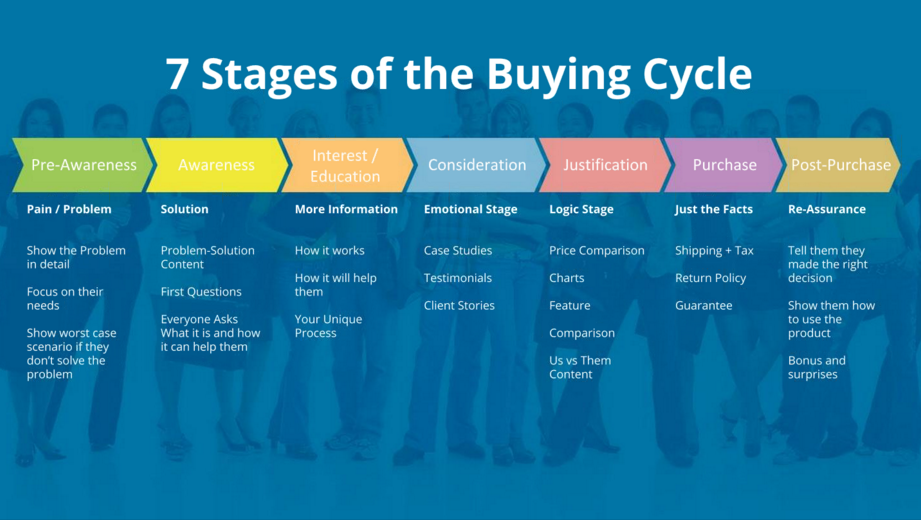

Acquaintance with basic emotions occurs both in the course of the entire educational process and in special classes where preschoolers experience a variety of emotional states, get acquainted with the experience of peers, as well as with literature, paintings, films, cartoons, performances and music that evokes emotions and feelings. The significance of such activities lies in the fact that children expand the range of conscious emotions, they begin to better understand not only their own feelings, but also the feelings of the people around them. Developing feelings, desires and views, our teachers teach to be attentive to each other's moods, to understand and clearly express their emotions, taking into account the mood and opinions of others. The independent activity of the child in a specially organized environment gives him the opportunity to express himself, acquire social skills in communicating with peers

The most effective and accessible methods for developing emotions in preschoolers are: role-playing and outdoor games, game exercises, psycho-gymnastics, the use of theatrical techniques of expressive movements, playing sketches, the active use of facial expressions and pantomime. With their help, the socio-emotional sphere of preschool children develops. Children learn to get acquainted with the help of the exercise “Hello, it's me”, “Let's get to know each other”. Problem situations or plots for dramatization games “A newcomer came to the group”, “I accidentally ...”, “What to do if ...” are widely used in working with preschoolers. As a result, children understand that friendship gives the joy of communication and you need to be able to deliver this joy to another person.

With their help, the socio-emotional sphere of preschool children develops. Children learn to get acquainted with the help of the exercise “Hello, it's me”, “Let's get to know each other”. Problem situations or plots for dramatization games “A newcomer came to the group”, “I accidentally ...”, “What to do if ...” are widely used in working with preschoolers. As a result, children understand that friendship gives the joy of communication and you need to be able to deliver this joy to another person.

Developing the emotional sphere of a preschooler, teaching him to understand his emotions and show them is the task of not only a psychologist, teachers and preschool educators, but also parents. Therefore, kindergarten has an integrated approach to this problem. For parents and educators, workshops, trainings, individual consultations are held, poster information is drawn up on the problems of developing the socio-emotional sphere of children.

Social and emotional development of preschoolers | Article in the journal "Issues of preschool pedagogy"

References:

Plotnikova, KM Social and emotional development of preschool children / KM Plotnikova. - Text: direct // Questions of preschool pedagogy. - 2019. - No. 2 (19). - S. 17-20. — URL: https://moluch.ru/th/1/archive/115/3889/ (date of access: 12/08/2022).

- Text: direct // Questions of preschool pedagogy. - 2019. - No. 2 (19). - S. 17-20. — URL: https://moluch.ru/th/1/archive/115/3889/ (date of access: 12/08/2022).

The socialization of the individual - this problem in the history of Russian pedagogy has always been relevant, this is reflected in the research works of famous teachers, such as V. S. Mukhina. She considered the identification and isolation of the personality as mechanisms of socialization, A.P. Petrovsky, who studied the regular change in the phases of adaptation, individualization and integration in the process of personality formation.

The task of developing children in their first years of life is to acquire skills that will enable them to become independent and able to act in social relationships and respond appropriately to their feelings and the feelings of others. These developmental tasks can only be solved by children in a stable socio-emotional environment.

The world of a child is colorful and varied, full of exciting and defining experiences. Daily new experiences bring with them a wide range of emotions that a child usually encounters unprepared. At these moments, we are often surprised to find how strongly the child experiences emotions, and how difficult it is for us to feel him. From the first days of life, the child has certain emotions from the outside world, especially from his parents. These early smiles, laughter, joy in the eyes of parents further determine the healthy development of the baby. Positive emotions help develop memory, language and movement. In response, you see that the child smiles or cries, knowing that this is how your child communicates with you. It is very important to promote the manifestation of positive emotions, the normal development of the child.

Emotions are a constant companion of a person, influencing all his thoughts and actions. Emotions are of paramount importance for educating a person on socially significant grounds: humanity and responsiveness.

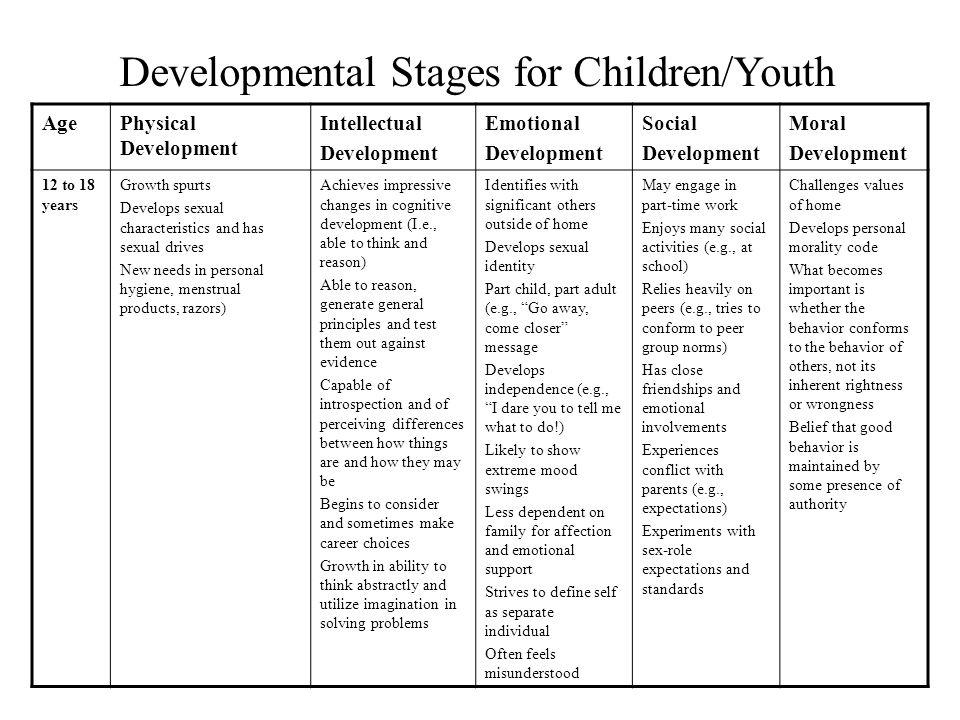

In preschool age, emotions play a significant role in the development of the child. They help to understand reality and respond to it. Manifested in behavior, they inform adults about what the child likes, what pleases or, on the contrary, upsets and saddens. As the child develops and grows, his emotional world becomes more diverse and rich. From the leading emotions (fear, joy), he moves to the most complex range of feelings. A child with developed emotions overcomes egocentrism more easily, better delves into educational and cognitive situations, more successfully fulfills himself in activities (Ezhkova N.S.).

During the preschool stage, development is faster than ever. A small child does not have the ability to control his own emotions. His emotions quickly appear and just as quickly disappear. Through emotional development in preschool age, emotions become more healthy and subordinate to thinking. But this happens when the child learns moral norms and correlates his actions and deeds with them.

Equally important is the development of emotional literacy.

Emotional literacy is the ability of children to write and talk about their emotions or feelings, as well as the emotions and feelings of those around them. It is a significant component of social-emotional development, as it can help children understand their own emotional experiences and at the same time help them understand and accept the emotional experiences of others. Emotional literacy can help children solve problems and regulate their emotions; these skills are important for success in preschool and beyond.

Socially developed children have the ability to develop the relationships with peers and adults necessary for success. Many factors can affect how children express their social skills or emotional competence or the rate at which children acquire social skills or emotional competence. These factors include: environmental risk factors such as living in an unsafe society, receiving care in poor childcare settings, family risk factors such as maternal depression or family mental illness, drug abuse, domestic violence, poverty and risk factors associated with the child, such as a fussy temperament, delays, and serious health problems. All of these factors need to be taken into account when gathering information to fully understand and support children's social and emotional health.

All of these factors need to be taken into account when gathering information to fully understand and support children's social and emotional health.

In this sense, social-emotional development can be seen as an important protective factor for young children, buffering them from stress and helping to prevent major emotional and behavioral difficulties from developing later in life.

The wrong preschool environment can be detrimental to the development of social skills, leaving children stressed by excessive, overly complex interactions with peers.

In fact, peers of the same age are not good teachers. As biological anthropologist Gwen Dewar says, "You need people to study people's skills." Preschoolers need to learn empathy, patience, emotional self-control, social etiquette, and an optimistic, constructive attitude towards solving social problems.

These lessons cannot be learned through peer-to-peer contact. Preschools are populated by impulsive, socially incompetent little people who are prone to sudden fits of anger or despair. Yes, preschoolers can offer important social experiences to each other. But their developmental status makes them unreliable as social mentors. A child who copies other children can pick up good habits, but she can also pick up bad ones.

Yes, preschoolers can offer important social experiences to each other. But their developmental status makes them unreliable as social mentors. A child who copies other children can pick up good habits, but she can also pick up bad ones.

That is why it is necessary to help a child develop social skills in preschool, they must be approached as carefully and consciously as teaching him reading or mathematics.

One of the most important functions of kindergarten is to teach children how to interact socially with others. Children who continue to express anger and frustration by hitting, screaming, and throwing objects will not only make it difficult for their needs to be understood, but might also isolate themselves. Knowing that there are more productive ways to express themselves and that what they say and do affects other people is key to making friends and becoming part of the children's community. Just as understanding of how to be polite comes, the child begins to take turns sharing, talking and playing with other children without the need for reminders and the use of polite language. However, mastering this skill is an ongoing process and kids are just learning it. It may take some time before the preschooler is able to share and be polite.

However, mastering this skill is an ongoing process and kids are just learning it. It may take some time before the preschooler is able to share and be polite.

Children should be able to work independently without constant redirection, as group and independent working times increase as kindergarten develops. Not only does this prepare the child for future learning, but it also helps build a sense of accomplishment and the understanding that he is a person capable of doing everything on his own.

Developing strong social skills means recognizing the value that other people bring to our lives by evaluating peers and adults fairly, developing the civility skills necessary for mature interaction, and developing a basic kindness towards people.

To develop emotional skills, children need the support of their parents. Here are some tips on how to contribute to a constructive increase in your child's emotional intelligence:

- Explain your own feelings

Explain to your child how you feel in a particular situation, for example, "I'm really annoyed right now because I can't find my glasses. " Speaking about your feelings, the child can learn to speak emotionally, in a different way. At the same time, he begins to understand the reasons why someone has certain feelings, as well as asking other family members to share their feelings and their origin.

" Speaking about your feelings, the child can learn to speak emotionally, in a different way. At the same time, he begins to understand the reasons why someone has certain feelings, as well as asking other family members to share their feelings and their origin.

- Talk about the feelings of others

Help your child to follow the emotions of people around him, characters in a book or movie, magazines or photographs. You could say, “Look, the girl who buys ice cream! She has such a big smile, I think she is looking forward to her ice cream!” Or, "Do you see a picture of a boy who looks so angry?" Maybe his mom told him he wouldn't get a candy bar. Recognizing the feelings of others helps your child understand them and develop compassion.

– Acknowledge your child's feelings

Respond if your child shows feelings of frustration, such as homework. You can say, “You look disappointed. Sometimes homework is really hard.” Recognizing and describing your child's feelings will give him more opportunities to express his feelings later on.

– Use more complex feeling terms

Once your child understands basic emotional terms such as "happy", "sad" and "angry", you should move on to more complex terms to steadily expand their vocabulary. Here are some examples:

- angry

- excited

- upset

– disappointed

– Recreate feelings through play

Play the emotions that your child has to guess, and then switch roles. Sing the same song with a changing emotional tone, such as a tired or excited voice. Play scenes from books or create your own stories and indicate people's moods. For example: "The girl in the photo looks scared, so I speak in a low and timid voice."

Literature:

- Ezhkova N. S. Emotional development of preschool children. Part 1: study method. allowance: in 2 hours / N. S. Ezhkova. — M.: Gumanitar, 2010.

- Zaporozhets A.V. The development of social emotions in preschool children / Ed.

Ya. Z. Neverovich. - M .: Knowledge, 2005.

Ya. Z. Neverovich. - M .: Knowledge, 2005. - The Development of Communication in Preschoolers / Ed. A. V. Zaporozhets and M. I. Lisina. - M .: Pedagogy, 1974

- Meshcheryakova S. Yu. On the nature of the revitalization complex // Experimental research on problems of general and ped. psychology. — M., 1975.

- Emotional disorders in childhood and their correction / Ed. V. V. Lebedinsky and others - M., 1990.

- Jacobson, S.G. Moral education in kindergarten [Text]: a guide for kindergarten teachers /S. G. Jacobson. - M .: "Education of a preschooler", 2003. - 112 p.

Basic terms (automatically generated) : child, your child, emotion, feeling, skill, emotional literacy, time, kindergarten, homework, emotional competence.

Development

emotional competence in preschoolers...conclude about emotional competencies children with speech violations and children C

In the study, preschoolers of the Preparatory group MBDOU “ Children Garden 9000

using cards Child easily absorbs the contents fairy tales, which will facilitate its retelling, and in . ..

..

The role of educators and parents in providing psychological ...

If a child comes to nursery kindergarten is not in a good mood or his mood deteriorates during the day, it is necessary to correct this situation. To do this, you can create toys for reacting negative emotions children : various hammers, magic wands.

Social

emotional development children child development ...In children Garden and in the family children experience emotional overloads, which can

in the group Garden We created such an environment so that children have

Purpose of the manual: recognition and fixing emotions of people. In particular, children like ...

In particular, children like ...

Means and methods of development

emotional sphere childPurpose: to form expressive standards in children , to contribute to the enrichment of the emotional sphere , to give an understanding of the division of positive and negative emotions , to teach them to recognize their own emotions and feelings that help them adequately... 1 Raising optimism in children preschoolers

The life of children is filled with various emotions , feelings and requires from children their correct understanding and appropriate response to them. children are often under the influence of feelings that overwhelm them and are not always able to control their emotions .

Emotional development preschooler | Journal article...

Therefore, work aimed at developing the emotional sphere of children very

After all, a child who understands the feelings of another, who actively responds to the emotions of others

and feelings do not exist outside...

Development

emotional responsiveness of preschoolers...Practice shows that in the development of emotional spheres of preschool children is weak

emotions - this is a “complex psychological mechanism that is combined in the process of

in the development of emotional children through the perception of artistic ..

Ways to develop

emotional intelligence in children .