Is your mama a

Is Your Mama a Llama?

None Lloyd the llama asks “Is your mama a llama?” as he searches for his own mama. Is your mama a llama? Lloyd asked his friend Dave. And what do you think is the answer Dave gave? Dave's mama hangs by her feet and lives in a cave. Now would you think that's how a llama would behave? Read along with this charming story about Lloyd the llama as he asks all of his animal friends “Is your mama a llama?“ See if you can answer before Lloyd realizes what kind of animal each mama is. And what do you think? Will Lloyd finally find his mama llama in the end? show full description Show Short DescriptionAnimals

Enjoy fun, animal stories for kids including bedtime favorites like Is Your Mama a Llama and Piggies in the Pumpkin Patch.

view all

Is Your Mama a Llama?

All About Kangaroos

Aggie and Ben: The Surprise

Aggie and Ben: Just Like Aggie

Aggie and Ben: The Scary Thing

Aggie the Brave: Get Well Soon

Aggie the Brave: A Visit to the Vet

Aggie the Brave: The Long Day

Good Dog, Aggie: Aggie At School

Good Dog, Aggie: Aggie in Training

Mechanimals

Click Clack Moo: Cows That Type

Who Am I? Wild Animals

Sweet Tweets: Five Little Ducks

Piggies in the Pumpkin Patch

One membership, two learning apps for ages 2-8.

TRY IT FOR FREE

Full Text

Is your mama a llama? “Is your mama a llama?” I asked my friend Dave. “No, she is not,” is the answer Dave gave. “She hangs by her feet, and she lives in a cave. I do not believe that’s how llamas behave.” “Oh,” I said. “You are right about that. I think that your mama sounds more like a... Bat!” “Is your mama a llama?” I asked my friend Fred. “No, she is not,” is what Freddy said. “She has a long neck and white feathers and wings. I don’t think a llama has all of those things.” “Oh,” I said. “You don’t need to go on. I think that your mama must be a... Swan!” “Is your mama a llama?” I asked my friend Jane. “No, she is not,” Jane politely explained. “She grazes on grass, and she likes to say, ‘Moo!’ I don’t think that is what a llama would do.” “Oh,” I said. “I understand, now. I think that your mama must be a... Cow!” “Is your mama a llama?” I asked my friend Clyde. “No, she is not,” is how Clyde replied. “She’s got flippers and whiskers and eats fish all day... I do not think llamas act quite in that way.” “Oh,” I said. “I’m beginning to feel that your mama must really be a... Seal!” “Is your mama a llama?” I asked my friend Rhonda. “No, she is not,” is how Rhonda responded. “She’s got big hind legs and a pocket for me... So I don’t think a llama is what she could be.” “Oh,” I said. “That is certainly true. I think that your mama’s a... Kangaroo!” “Is your mama a llama?” I asked my friend Llyn. “Oh, Lloyd, don’t be silly!” Llyn said with a grin. “My mama has big ears, long lashes, and fur... And you, of all people, should know about her! Our mamas belong to the same herd, and you know all about llamas, ’cause you are one, too!” “Yes, you are right,” I said to my friend. “My mama’s a... Llama!” And this is... THE END

“She’s got flippers and whiskers and eats fish all day... I do not think llamas act quite in that way.” “Oh,” I said. “I’m beginning to feel that your mama must really be a... Seal!” “Is your mama a llama?” I asked my friend Rhonda. “No, she is not,” is how Rhonda responded. “She’s got big hind legs and a pocket for me... So I don’t think a llama is what she could be.” “Oh,” I said. “That is certainly true. I think that your mama’s a... Kangaroo!” “Is your mama a llama?” I asked my friend Llyn. “Oh, Lloyd, don’t be silly!” Llyn said with a grin. “My mama has big ears, long lashes, and fur... And you, of all people, should know about her! Our mamas belong to the same herd, and you know all about llamas, ’cause you are one, too!” “Yes, you are right,” I said to my friend. “My mama’s a... Llama!” And this is... THE END

1

We take your child's unique passions

2

Add their current reading level

3

And create a personalized learn-to-read plan

4

That teaches them to read and love reading

TRY IT FOR FREE

Is Your Mama a Llama? (Short 2001)

- 20012001

- Not RatedNot Rated

- 7m

YOUR RATING

AnimationShortFamily

Lloyd the llama is looking for his mama. "Is your mama a llama?" he asks a bat, a swan, a cow, a seal, and a kangaroo. Young children will share Lloyd's delight when the answer to his questi... Read allLloyd the llama is looking for his mama. "Is your mama a llama?" he asks a bat, a swan, a cow, a seal, and a kangaroo. Young children will share Lloyd's delight when the answer to his question is finally, "Yes!"Lloyd the llama is looking for his mama. "Is your mama a llama?" he asks a bat, a swan, a cow, a seal, and a kangaroo. Young children will share Lloyd's delight when the answer to his question is finally, "Yes!"

"Is your mama a llama?" he asks a bat, a swan, a cow, a seal, and a kangaroo. Young children will share Lloyd's delight when the answer to his questi... Read allLloyd the llama is looking for his mama. "Is your mama a llama?" he asks a bat, a swan, a cow, a seal, and a kangaroo. Young children will share Lloyd's delight when the answer to his question is finally, "Yes!"Lloyd the llama is looking for his mama. "Is your mama a llama?" he asks a bat, a swan, a cow, a seal, and a kangaroo. Young children will share Lloyd's delight when the answer to his question is finally, "Yes!"

YOUR RATING

- Director

- Virginia Wilkos

- Writer

- Deborah Guarino(book)

- Star

- Amy Madigan(voice)

- Director

- Virginia Wilkos

- Writer

- Deborah Guarino(book)

- Star

- Amy Madigan(voice)

Photos

Top cast

Amy Madigan

- Narrator

- (voice)

- Director

- Virginia Wilkos

- Writer

- Deborah Guarino(book)

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

User reviews

Be the first to review

Details

- Release date

- 2001 (United States)

- Country of origin

- United States

- Language

- English

- Production company

- Weston Woods Studios

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Technical specs

- Runtime

7 minutes

- Color

Related news

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content

More to explore

Recently viewed

You have no recently viewed pages

Why is your mom still not screwed up? / Sudo Null IT News

Case of a homeless person

One day in late December, when the air smells of fireworks burning over the city, and the streets are full of people panicking over pea prices, I decided to teach programming to a homeless person. He was sitting against the wall in the underpass; a middle-aged man with reasonable eyes, not drinking or degraded, in neat but very shabby clothes. It is clear that he experienced loneliness and despair.

He was sitting against the wall in the underpass; a middle-aged man with reasonable eyes, not drinking or degraded, in neat but very shabby clothes. It is clear that he experienced loneliness and despair.

Usually, instead of money, I give male beggars the phone number of the personnel department of a courier company that is constantly in need of employees. But he didn't have legs... Then I thought: " Dude, you have plenty of time. Working at a computer is the best thing that can happen in your life. The coupon for the PHP course discount is what should have been put on your bed where your legs used to be when you woke up after the amputation of .”

I decided to offer him to learn programming. In his position, he must have been motivated as hell. But will he succeed?

Of course not!

I have seen many times in the past how people fail. Every programmer in Russia has had or will have a moment when he starts earning more than all his non-IT acquaintances put together (the exception is successful businessmen, of whom there are so few that they can be ignored). Naturally, some of them have a desire to repeat the success. And then we watch with pain in our hearts how nothing comes out of them.

Naturally, some of them have a desire to repeat the success. And then we watch with pain in our hearts how nothing comes out of them.

In my environment, my older brother, girlfriend, girlfriend, friend, several hated acquaintances and colleagues from previous jobs unsuccessfully tried to fall for the life-giving source of coding. Some several times. Most of them explain their fiasco like this: “ Programming is not mine. I have no talent for this .”

A talent for programming

I remember a friend's story about how she became a cellist. The teacher came to the class and asked the children to show their hands. For the cello, with its huge strings, it is absolutely essential that the player has puffy, unslanted fingertips of a special shape. These were the only ones she had.

In famous kyokushin dojos in Japan, teachers ask dads to bring boys to class. To look at the thickness of the bones in the limbs of the parent, because people with thin bones will never learn to break stones with their bare hands, even at the first dan. It's pointless to train them. The apparatus of mental representation must work in a special way for a future artist. Simply put, by closing the eyes, the artist must be able to clearly see the image being presented. Without this ability, he will never rise above the level of mediocrity. That is, for success in various types of activity, appropriate giftedness and talent are necessary.

It's pointless to train them. The apparatus of mental representation must work in a special way for a future artist. Simply put, by closing the eyes, the artist must be able to clearly see the image being presented. Without this ability, he will never rise above the level of mediocrity. That is, for success in various types of activity, appropriate giftedness and talent are necessary.

Is there a talent for programming?

The key ability of a programmer

In my experience, the main feature required to become a programmer is the ability to endure the frustration that arises from overcoming cognitive complexity for a long time, in everyday mode. Not the mind, not the rationality of thinking, not a high concentration of attention, but the ability to endure suffering, understanding something complex.

Frustration from cognitive complexity is the same unpleasant feeling that arises when you can't figure out some confusing garbage. Almost all the daily work of a programmer consists of such moments. Such frustration is expressed in the reflex tension of the muscles of the body with holding the breath. It is unpleasant in itself, but the worst begins a moment later: depending on their personality type, a person begins to feel annoyed, angry (remember those colleagues who yell at their code when it does not work) or sadness and frustration (remember exhausted , demotivated colleagues, reminiscent of sluggish pasta).

Such frustration is expressed in the reflex tension of the muscles of the body with holding the breath. It is unpleasant in itself, but the worst begins a moment later: depending on their personality type, a person begins to feel annoyed, angry (remember those colleagues who yell at their code when it does not work) or sadness and frustration (remember exhausted , demotivated colleagues, reminiscent of sluggish pasta).

As a result, for any person, the programming process is filled with suffering. A normal person does not like pain and quits.

The Engine That Couldn't

My older brother, a high school silver medalist and smart guy, went through something like an exorcism while learning to program. He burned terribly when something did not work out. Bugs for a long time brought him out of balance. It turned out that he could not be at the computer for a long time without physical activity. And he was very upset when something did not work out. Or rather, he didn’t get upset once, a second, a third, demonstrating normal stamina for a person, and then he broke down. Several times a day he went outside and walked for a long time somewhere just to get moving.

Several times a day he went outside and walked for a long time somewhere just to get moving.

Then he began to procrastinate, taking every opportunity to distract himself. At the same time, complaints began of excessive tension in the whole body, especially in the shoulders, eyes and head. The back of my head started to hurt. Many people of intellectual labor complain of such pains. And although his training was going well, it was clear that he was not well.

And then he gave up.

I really wanted him to succeed. He started working at the age of 14 and actually replaced his father in our family. Until the age of 28, he worked in a mine in the north, sending us almost all the money he earned so that we, the younger brothers, would get back on our feet. Because of this, he never received a higher education and did not start his own family. I really wanted him to succeed, and a bright streak came in his life ... But nothing happened.

And, of course, looking at this person in the transition, before giving him my old computer, paying for courses and a month of living in a hostel, I thought about whether this story would repeat itself, whether he had this ability. From the looks of it, almost certainly not. He looked too normal. The fact is that the ability to tolerate the frustration of cognitive complexity, in my experience, is possessed by special people.

From the looks of it, almost certainly not. He looked too normal. The fact is that the ability to tolerate the frustration of cognitive complexity, in my experience, is possessed by special people.

Freaks

To make it clear, I will describe to you a few programmers I know:

-

Paranoid building a bunker in the suburbs in case of an apocalypse. Being the team leader of the project, he complicated and confused it so much that now only he understands how everything works. In fact, now he holds the entire company by the throat.

-

A sleazy guy with a scraggly deacon beard and Asperger's syndrome (a mild form of autism), coding like a god, but completely unaware of such simple things as flirting or humor.

-

C++ programmer with schizoid personality disorder who looks like a living skeleton. For several years, he alone created his own object search engine.

-

An effeminate young man with a quiet voice, never making eye contact, jokingly being a personal slave to his feminist girlfriend.

I think you already understood.

The rarest type in our environment is an ordinary man who does not experience problems with the opposite sex and friends, has a prosperous family, is handsome, sociable, loves physical activity and is normally developed. No mental problems. Man is the norm. Programming is filled with weirdos like no other profession. Freaks, outcasts, subculturists, sociophobes, suicidal, depressive, anxious, angry paranoids, people with serious psychological problems - whom I have not met among our brethren. It is they who have a treasured quality: the ability to withstand the frustration of cognitive complexity for a long time.

Let me explain how it appears, using the example of the same acquaintances:

-

The paranoid Proger, who made his company a nightmare, gained the ability to long and meticulously break through cognitive complexity due to the fact that he does just that in his daily life. The fact is that he always expects a dirty trick and betrayal from everyone around.

In fact, he is always on guard and never relaxes, controlling everything around him in general, like a chess player during a game. He is so accustomed to this state that the discomfort of cognitive complexity is completely normal for him. Nevertheless, from time to time he needs a discharge. Then he goes into brutal drinking bouts.

In fact, he is always on guard and never relaxes, controlling everything around him in general, like a chess player during a game. He is so accustomed to this state that the discomfort of cognitive complexity is completely normal for him. Nevertheless, from time to time he needs a discharge. Then he goes into brutal drinking bouts. -

A programmer with Asperger's Syndrome simply can't be frustrated. His psyche is arranged in such a way that he simply does not experience frustration, bumping into cognitive complexity. Accordingly, he has no discomfort from it and easily endures the hardships and hardships of the programmer's service.

-

The essence of schizoid disorder is the split between mind and body. In fact, such people do not feel their bodies, and since emotions, including frustration, anger and sadness, are bodily reactions, they do not feel them either. Negative sensations in the body do not corny interfere with his mental activity in the field of programming.

-

The slave boy is in a long depression. He experiences frustration, but it does not cause anger, but sadness. His body is weak and flabby, his arms are bamboo. The muscles are not so tense that they do not cause him any discomfort. Accordingly, he can sit at a computer for days on end, does not need physical activity at all, and easily tolerates cognitive complexity. At the same time, he has an extremely low level of motivation. He needs a bitch girl, because only she, with her pressure, can make him do at least something.

This is how it works. I think if you are related to programming, then you yourself offhand throw examples of eccentric programmers. With the ability to endure frustration, they traverse a road with relatively little loss, the sides of which are littered with the bones of their more ordinary comrades.

Non-eccentrics

Does this mean that a non-eccentric cannot become a programmer, and our brothers, sisters, great-nephews will never repeat your success, entering the world of the rich and famous? For a while, that's what I thought. Moreover, I have witnessed how a few programmers, thanks to a good life and high salaries, solved their problems and lost their eccentricity. After that, cognitive complexity became a problem for them too, it became difficult for them to program, and they went into various related fields. Several left for more prosperous countries and became so limp there that they became good for nothing.

Moreover, I have witnessed how a few programmers, thanks to a good life and high salaries, solved their problems and lost their eccentricity. After that, cognitive complexity became a problem for them too, it became difficult for them to program, and they went into various related fields. Several left for more prosperous countries and became so limp there that they became good for nothing.

This is how I would have lived, dropping the poison of skepticism into the souls of novice programmers, if Sasha had not got a job with me.

My first non-eccentric programmer friend

Sasha worked as a security guard. A completely ordinary guy, without any raisins whatsoever. An exemplary freak. He looked like my brother. And this person came to get a job as a PHP programmer. He tritely learned the textbook on his shifts at the mall. Almost by heart. But in practice he did not know how to do anything.

My organization could not hire a real programmer for financial reasons. They were going to pay 30 thousand and, of course, for this amount I could only take a junior. And that's not everyone. Obviously, I didn't have much of a choice. After evaluating the candidates, I called Sasha. All my experience said that he would not become a full-fledged programmer, but he was at least sane, which means he had to be executive. We had to make a website that would automatically parse tender sites, forming a single database for our managers. I expected that being adequate and diligent (after all, he still learned that textbook), Sasha would be able to at least simply follow my instructions regarding routine operations, and we would complete this task step by step.

They were going to pay 30 thousand and, of course, for this amount I could only take a junior. And that's not everyone. Obviously, I didn't have much of a choice. After evaluating the candidates, I called Sasha. All my experience said that he would not become a full-fledged programmer, but he was at least sane, which means he had to be executive. We had to make a website that would automatically parse tender sites, forming a single database for our managers. I expected that being adequate and diligent (after all, he still learned that textbook), Sasha would be able to at least simply follow my instructions regarding routine operations, and we would complete this task step by step.

When we started, my doubts only intensified. It was really difficult for Sasha. Faced with cognitive complexity, he went through a whole range of negative emotions from anger to despair. Every now and then I heard his heavy sighs and curses under his breath. “Yes, how so!” and "I don't understand!" came out of his mouth hundreds of times a day. When it got really bad, he went out to smoke, or arranged a small workout right in the middle of the office. It was difficult for him to sit still at the computer. Like my brother, he needed to move. We agreed that every half an hour he would get up and, for example, go for tea, etc. But not more often, because otherwise it will turn into a way to procrastinate.

When it got really bad, he went out to smoke, or arranged a small workout right in the middle of the office. It was difficult for him to sit still at the computer. Like my brother, he needed to move. We agreed that every half an hour he would get up and, for example, go for tea, etc. But not more often, because otherwise it will turn into a way to procrastinate.

Adding to the problem was his rudimentary English, which prevented him from fully using Google. The second, purely utilitarian, problem: while typing, he looked for each key with his eyes. And pressed it with one finger. It took an extremely long time.

We agreed that he would contact me only if he himself could not find a solution three times. And this happened often. The first time he had to explain literally everything. Luckily, we weren't too tight on deadlines, so he had plenty of time to deal with every problem that came up.

Pretty soon his eyes started to hurt from constant looking at the screen. He somehow made it to the end of the month and bought a large monitor with his first paycheck, which solved the problem. This was an all the more desperate act, because I knew that he had no money and that he was eating only buckwheat, a bag of which had been bought in advance just for such an occasion.

He somehow made it to the end of the month and bought a large monitor with his first paycheck, which solved the problem. This was an all the more desperate act, because I knew that he had no money and that he was eating only buckwheat, a bag of which had been bought in advance just for such an occasion.

It became clear that Sasha did not intend to retreat. And there were reasons for this. Soon he began to complain of pain in his right hand, which holds the mouse. Sort of like carpal tunnel syndrome. Pain shot through his shoulder, spreading to the right side of his body. He had never spent so much time at the computer before. I had to go to a neurologist and slightly change the position of the hand. However, the pain did not go away completely, and from time to time I saw him shift the mouse to use it with his left hand.

It was difficult for Sasha, but I saw that he was determined to break out of the vicious circle of physical work that had fed him until now. For three months, leaving home, I left it in front of the monitor. And each of my next working day began with questions about the problems that he had accumulated while I was gone.

And each of my next working day began with questions about the problems that he had accumulated while I was gone.

At first, his mood was not to hell, but gradually I began to notice that something new appeared. It was pride. He praised himself more and more and asked for my help less and less. I still saw that sometimes he struggles with some elementary problem for half a day, but he found solutions completely on his own. And it happened faster and faster.

Until the day came when he never spoke to me.

We launched that tender site on time. Sasha still works as a programmer. This was the first programmer in my experience who entered the profession without being an intellectual at all and without any mental traits that would protect him from the frustration of cognitive complexity. I think he succeeded because he did not have the right to retreat: his wife, who was pregnant with her first child, was waiting for him at home.

Terminal

Freaks by default have the ability to tolerate the frustration of cognitive complexity. This allows them to successfully master programming, if they ever have such an idea. Non-freaks don't have this ability. Therefore, they tend to fail. But that doesn't mean they can't train her. They just don't do it.

This allows them to successfully master programming, if they ever have such an idea. Non-freaks don't have this ability. Therefore, they tend to fail. But that doesn't mean they can't train her. They just don't do it.

Your non-eccentric friend, who failed his attempt to become a proger, did not even try, because in his head there is an illusion about giftedness, that in order to become a programmer, one must have the appropriate talent. Dozens of times before, since childhood, he tried to make three-dimensional models, knit macrame, draw anime and play the harmonica. As a result, a template appeared in his head: if it’s difficult, if it doesn’t work out better than others, if it’s boring, then there is no talent, you have to quit and go looking further. Such a person takes up programming (and indeed anything difficult to understand), stumbles upon cognitive complexity, decides that it’s not Juan’s sombrero, and immediately gives up.

This is learned helplessness. It is she, and not frustration in itself, like a magic gate, that closes the path to treasures. This is the habit of retreating before pain and difficulties, taking them as a sign of one's unsuitability for the chosen activity.

This is the habit of retreating before pain and difficulties, taking them as a sign of one's unsuitability for the chosen activity.

— You know, Lyokha, I always considered myself a special person, — that man told me when we were sitting at the bus stop with hot dogs and coffee I bought. - Even before my birth, my mother was told that I would achieve a lot, that I would be a great person. Look at me. Where am I and where is the big man?

We all believe in childhood that we are special, that there is something in us that will bring us strength, fame and fortune, and then we wait for this something to manifest itself, look for our talent, try hundreds activities, change hobbies and try, try, try in search of the Grail hidden in us.

And most of the time we don't find anything. Here you are 35 and you are nothing special. And even worse - you have no legs.

Pythia says to Neo: “ I have seen many chosen ones. And you're definitely not one of them0008".

Blade Runner robot police officer Kay suddenly finds out that his memories are fake. He is not the first born android. It's a normal factory stamp.

He is not the first born android. It's a normal factory stamp.

Asta loses the first fight. He will never become the Wizard King.

A legless man gives up after two weeks of trying and takes my old laptop to the pawnshop.

Even if this happened, you still have a way out. Everything can change dramatically if you learn to do something useful for good money. It doesn't have to be programming. But for this you need to understand the main thing:

It is impossible to find oneself special, one can only create oneself special.

Choose a difficult, difficult task, turn towards cognitive complexity and step through it. A non-eccentric will never find a talent for programming in himself. Such talent does not exist. He must make himself a programmer from himself. Grit your teeth and try your best, ignoring the negative feedback that non-geeks always get from programming.

He will beat with anger, hands will fall, despair will roll over. Forces will leave, you will begin to make mistakes and begin to feel like nothing. Your body will hurt, your eyes will water, your hair will fall out, others will tell you about your lack of talent and other nonsense, sometimes you will be deadly bored, but if you persist, then at some point all this will cease to be a problem.

Forces will leave, you will begin to make mistakes and begin to feel like nothing. Your body will hurt, your eyes will water, your hair will fall out, others will tell you about your lack of talent and other nonsense, sometimes you will be deadly bored, but if you persist, then at some point all this will cease to be a problem.

This is the Hero's Path.

What to do when your mother is a cannibal

The invasion of Ukraine has irrevocably changed the reality of all Russians - even if some of them pretend that this is not so. Among the people who will have to deal with the consequences of the war the longest are those who are not even formally responsible for it: children living in Russia. The writer Yulia Yakovleva, who wrote, among other things, a series of children's stories "Leningrad Tales", decided to find out what Russian children think and feel now - and since the end of February she has already talked with several dozen interlocutors aged from five to seventeen years. Kholod publishes some of the results of this non-scientific study.

Kholod publishes some of the results of this non-scientific study.

There are no definite and indefinite articles in Russian, as, for example, in English. Instead, there is mutual understanding in a specific conversational situation: the interlocutors simply understand that this is not about a dog or a house in general, but about this dog and this house. Certainty, as it were, hangs in the air between the speakers.

So it is with war. Previously, the very word "war" in a conversation immediately dragged to itself the certainty of the war of 1941-1945, the "war" was the Great Patriotic War. Now not so. If you say “war”, then the interlocutor will immediately think: the war in Ukraine, the war with Ukraine, the war that is happening now.

In 2015, the Samokat publishing house published my book Children of the Raven, and, as it turned out, marked the beginning of the Leningrad Tales series. These are books about growing up when the world has collapsed. Time of action - 1938-1946. Shortly after the outbreak of the war, one of the readers wrote to me what I felt myself: now we live in the reality of "Children of the Raven."

Shortly after the outbreak of the war, one of the readers wrote to me what I felt myself: now we live in the reality of "Children of the Raven."

To write these books, I read a lot of personal testimonies of the era: letters, diaries, memoirs. One of the most poignant Russian documents of the war of 1941-1945 was the diary of the Leningrad girl Tanya Savicheva, the last entry of which is known to almost everyone in St. Petersburg: "Everyone died, only Tanya remained." Children's testimonies about the war are always an accusation of the war, even if they are distributed in the country that attacked.

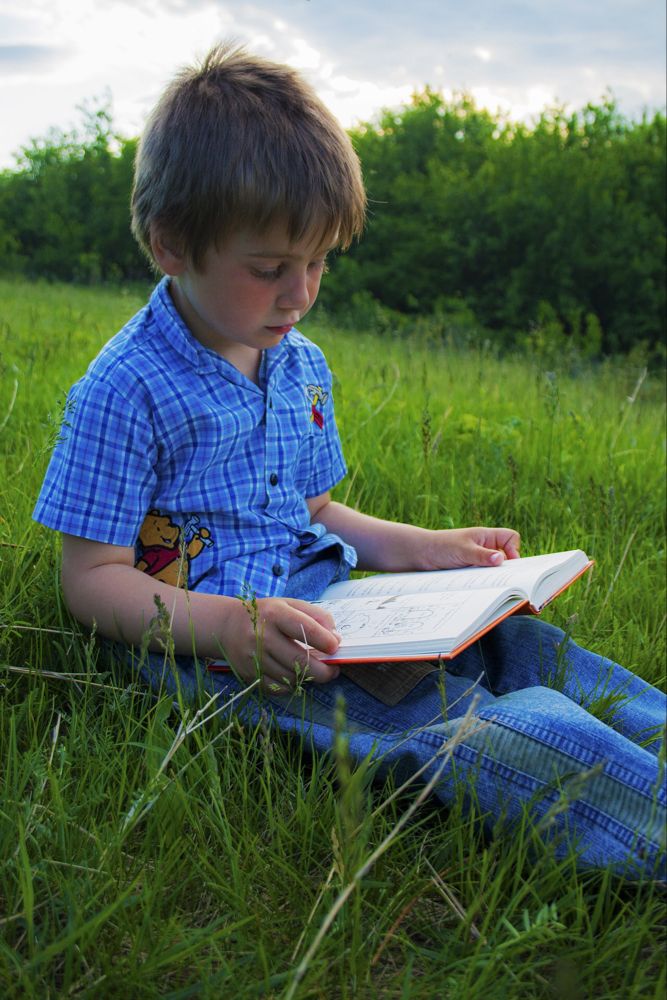

Modern children almost never keep diaries. And if they do, they do not write every day. Therefore, when the war began, when a week passed, another went on, the end did not come, and it was only clear that we were experiencing something unimaginable, unthinkable, I began to talk to the children. Ask, collect their stories about how they live now. What they see, hear, think. How they go to school, walk, quarrel, make friends, read. What they feel.

What they feel.

I thought this: I would surely see how the war, which goes far from them, permeates their conversations, their quarrels and friendships, their growing up. I thought these stories would become priceless over time. People will want to know this just as we would like to know what children did, said, thought in Germany in 1933-1945. Or not, not so: these stories are priceless right now. Ultimately, it is not the 70-year-old president who decides the future of Russia. It will be determined by those who are now 5 or 17, 8 or 13. In short, children. More precisely, my interlocutors.

This is not an anthropological study or a poll. These are just conversations recorded during the war, they do not pretend to anything else. I spoke with about two dozen children myself, about the same number wrote answers to the questions sent. I have compiled a list of questions so that they sound as neutral as possible, take into account different aspects of what is happening, take into account, most importantly, the unprecedented split that the war has caused in Russian society. Arguing, persuading, persuading, or simply conveying my own point of view was not part of my task. Do you support the war? Tell. Are you against war? Tell.

Arguing, persuading, persuading, or simply conveying my own point of view was not part of my task. Do you support the war? Tell. Are you against war? Tell.

Most of the respondents are aged 12 and over. The youngest are five. A few tongues can't be called children: adults, independently thinking people of 17 years old. With each parent, I spoke first myself to find out the boundaries of what topics they allow to be discussed. Some asked questions in advance, someone eventually refused. More than once I found myself in dilemmas. What should I do when a little boy suddenly whispers to me: tell me what happened there, in Bucha, otherwise no one speaks? Only once did a child ask me why I was asking all these questions. I replied that in one Icelandic saga, the hero is asked in the same way, it seems to be a troll, and the hero answers: because I want to know. This answer satisfied both the troll and the child.

One of my fellow journalists whom I asked to join my venture was, in a sense, quite right when she refused: "It's pointless. " From a statistical point of view, yes, of course, it makes no sense. I will never be able to say: children in Russia thought this and that. So why is my belief so strong that these stories are valuable? Very simply: because these children themselves decided so. I didn't eavesdrop on conversations on the streets. Didn't throw a bait. I did not pretend not to be who I am. She explained the reason to everyone equally and directly: because the time is now historical. Because I want to know.

" From a statistical point of view, yes, of course, it makes no sense. I will never be able to say: children in Russia thought this and that. So why is my belief so strong that these stories are valuable? Very simply: because these children themselves decided so. I didn't eavesdrop on conversations on the streets. Didn't throw a bait. I did not pretend not to be who I am. She explained the reason to everyone equally and directly: because the time is now historical. Because I want to know.

My youngest interlocutors are five or six, they were, of course, persuaded to talk to me by their parents. The little ones do not know that there is a war going on, they live not in time, but in eternity, and one must peer intently to notice in the innocent stream of their speeches how the sign of the times will flash, how the quick, undoubted shadow of war will flash. Another thing is teenagers. I met confused, angry, mocking, strict, arrogant, angry. But the very fact that they wanted to talk about their experience says that they realize the value of both their position and what they experienced. Recognize the historicity of their experience. In this realization, I see the seeds of something more. What would later become "society". What would later become a "generation".

Recognize the historicity of their experience. In this realization, I see the seeds of something more. What would later become "society". What would later become a "generation".

Read more

Just don't tell mom

I'm asking parents for permission to talk to their child.

- Well, talk. But she probably won't say anything.

— You can talk, but I have no idea if my children can say something, what to tell them?

- Talk, only there can be strange reactions, a teenager is a teenager.

- Talk? He doesn't read anything at all, he doesn't think about anything.

— He doesn't like to talk with us.

- Try it, but it may not work, she does not communicate with anyone.

Parents shrug their shoulders, doubt, many agree, but many refuse. This is just not strange: each of the parents is obliged to reckon with the reality of Russia, in which they are punished for words.

That's strange. All parents were once children themselves and—oh, horror—teenagers. Since then, they should remember that the life that children lead and the life that parents think their children lead are, to put it mildly, different, sometimes even two different lives. From this thought alone, the parent's heart freezes. Especially now, when ears are growing again in the walls, and a child is a child: he can blurt out, blurt out, write, do, blurt out what adults are punished for. “I can’t believe I said it, me! “But I told her: I forbid you to say that at school.” Alas: to forbid something to a teenager is more or less senseless. They will not stop doing what you have forbidden. They'll just do it in a way that you won't know. And they do.

Since then, they should remember that the life that children lead and the life that parents think their children lead are, to put it mildly, different, sometimes even two different lives. From this thought alone, the parent's heart freezes. Especially now, when ears are growing again in the walls, and a child is a child: he can blurt out, blurt out, write, do, blurt out what adults are punished for. “I can’t believe I said it, me! “But I told her: I forbid you to say that at school.” Alas: to forbid something to a teenager is more or less senseless. They will not stop doing what you have forbidden. They'll just do it in a way that you won't know. And they do.

- Don't tell your mom. If you want, we can remove it completely, - then I suggest. No, you don't need to clean up. Let it be. Just don't tell your mom.

- Mom will be upset.

Each of them has already seen how vulnerable parents are. How a distant war breaks holes in what seemed so reliable, boring, forever, and now it is staggering. For many children this happened for the first time.

For many children this happened for the first time.

— I have never seen such an expression on my mother's face.

- Dad shouted, it happens not only rarely, it just never happens. Do you understand? Never.

- We were immediately afraid for my mother.

— When we found out that my mother was detained, we began to laugh wildly. Then they calmed down, began to think.

— Mom said don't talk about it at school. Don't tell anyone else, they'll think we're talking like that at home.

- I deleted my accounts completely. You see, I am responsible - for my mother, for my father, for my grandmother, for my grandfather.

I want to shout: when you are 12 (13, 14, 15), your responsibility is, for example, lessons, and not all the adults in your family, power in the country or the end of the war. But in Korea there is a legend about a tree: when a secret presses from within, you need to find a tree with a hollow, tell everything in the hollow, and then wall it up. Therefore I am silent; now I am a tree, they say. And sometimes I felt like a lightning rod into which they discharged their lightning.

Therefore I am silent; now I am a tree, they say. And sometimes I felt like a lightning rod into which they discharged their lightning.

None of the conversations lasted less than an hour.

Read more

I look around

In every conversation, I tried to first clarify what exactly the children themselves observe. What is the overview available to them? It quickly became clear that children are like cats: they bypass "their" territory by the same routes every day. The younger the child, the less he has this “own” territory: home - school, school - home - circle, and along the way parents look after. Only teenagers “walk”, but they also have their own proven, favorite places and routes for this. When you go to the same places in the same way, you notice changes faster. What has appeared or disappeared since the beginning of the war?

- Flags. At first they appeared a little. Then more and more.

— One day we went out to go to school, and I said: don't you see what has changed? Them: what? Me: yes flags! flags are everywhere now.

- Many flags. Above every entrance, and somewhere on every floor.

I can see the sewing shops that sew Russian tricolors. The country is big. Most likely, all the flags of this spring were bought where it is cheaper, in China. But still, it is obvious that this is a huge item of government spending.

While the cities are arranged in such a way as if triumphant victors live in them, the war breaks into Russian teenagers through the narrow windows of telephones.

- My eyesight has been very poor since the beginning of the war, I read on my phone all the time.

- I read a lot, then got tired, demolished all the channels, leaving only one or two.

- I read everything, Department of Defense briefings, independent media, everyone. I want to understand what is going on, but everyone one way or another tells only part of the truth.

- I only read, I don't look at photos, I'm afraid.

The other one doesn't look either, but for a different reason:

— Photos and videos serve to evoke a reaction, but I'm more interested in the mechanisms of what is happening. I don't need to prove that people die in war.

I don't need to prove that people die in war.

- It's easier for me through videos and photos. Only eyes blur. It's easier when it's spoken.

— And what do you mean, the eyes are blurry? I ask. But she immediately slams shut: “What?”. Cool girls don't cry.

I am against the war

From the very first days of the war, the state launched huge punitive efforts to stop any protest movement, to stop discussion of the war in Russian society. This alone shows that discussion is equal to condemnation, and the state is incredibly afraid of this fact. The protest after the bans did not fade away. It turned into a peat fire. What it is, Petersburgers, for example, know very well: the flame is not visible, everything is smoldering somewhere, and the city is gradually covered with smoke. The protest took the form of small signs that are shared with each other, with the city, with the world, with anyone who sees. Anti-war stickers, graffiti, leaflets, figurines, price tags, ribbons. They are left quickly, on the move - someone leaves, someone's invisible hands. And their own hands.

They are left quickly, on the move - someone leaves, someone's invisible hands. And their own hands.

Read more

Older children and teenagers talk about it with a mixture of horror and delight. Delight - because it's like such a game. It is as if they themselves are in a fairy tale about the Little Thumb, who leads the cannibal by the nose. Her heart is not pretending to be pounding, this fear is completely genuine. These children already know that the state grabs at random, but does not stand on ceremony with teenagers. They sensibly explain to me under what article they are now being taken away, what fines, what terms, what administrative detention is, how they are registered. They are afraid not only of deadlines and fines, and even not so much of them. They are afraid of what their mother will experience. That the grandmother will be scared (“but she can’t”). What dad will say: how is it, I warned you. What the teacher will report to the FSB. But they are even more afraid that they will be grabbed by other people's rough hands, that adults in uniform will yell, bark, bark at them: beefy men or women - when you are 11, all adults seem large.

They are afraid. And they still do it. Overcoming fear inspires.

— We began to tie green ribbons everywhere. And they appear all in new places. I wanted to knit mine. I look and it's already there. It became so nice.

— I wear two bracelets with the colors of the Ukrainian flag.

— We made the badges ourselves. Do you wear them at school? Yes, at school. And when we go outside, we do not change our minds, we just remove and hide the badges. - Why are you hiding? - Scary. - What are you afraid of? - That some adults can beat us or say something.

- In the subway, people always put stickers or just chewing gum on posters for the war.

State propaganda - it is also beefy, muzzled, it is everywhere. Cities are plastered, hung with banners and posters. State propaganda is printed in a printing house, it is made for money, packaged, packaged, delivered. She is industrial. This is business, nothing personal. But in the protest, everything is the other way around: here everyone is doing it themselves, drawing as best they can, writing by hand. In these signs personally everything, and above all, choice. This is the choice of a particular person, the work of his own hands. These tiny signs are a kind of fleeting touch of a person to his city, they have become an important and visible part of the urban environment. Appearing and disappearing, reappearing (there is no such janitor who would keep up with teenagers), they are like pulsing lights: signals to those who think the same way, "just afraid or can't say."

In these signs personally everything, and above all, choice. This is the choice of a particular person, the work of his own hands. These tiny signs are a kind of fleeting touch of a person to his city, they have become an important and visible part of the urban environment. Appearing and disappearing, reappearing (there is no such janitor who would keep up with teenagers), they are like pulsing lights: signals to those who think the same way, "just afraid or can't say."

— I don't want to use pompous words, but, probably, the point is that you are not alone.

- When I see something like this on the way to or from school, I always take a picture of it and keep it for myself. How many of these photos do you already have? “More than fifty for sure.

I hate them

The stories of those who are against accumulated, quickly turned into a majority, which is getting bigger day by day. There are others: as one girl called it, "ambivalent." Not against and not for, that is, they themselves do not know for what and against what, confused, agitated, they seemed to come to me for something else - clarity? answers? Don't know. But I did not meet a single distinct, convinced and confident “for”. But it is the opinion of the supporters of the war that seems to me the most important: for close scrutiny, reflection. What is this child thinking? How does it fit in your head? Here's what I wanted to see.

But I did not meet a single distinct, convinced and confident “for”. But it is the opinion of the supporters of the war that seems to me the most important: for close scrutiny, reflection. What is this child thinking? How does it fit in your head? Here's what I wanted to see.

To be against the war is understandable, extremely natural. Not to approve of the destruction, death and suffering of civilians, children - what is strange in this? What is not clear? Is it necessary to explain something here? To approve and support the killing of people is really incomprehensible. It ended up that I was looking for such children on purpose and continue to look. Have not found yet.

And I don't know how to interpret it. Perhaps I myself become the filter with my “Leningrad Tales”. For seven years during this series, I talked about the fact that cowardice is a disaster, and courage means being afraid, but still going forward. I wrote that it hurts everyone, that war is horror and corpses, and not a parade and fireworks, that in war there are no winners and losers, but there are dead and murderers, that there is no “we”, but only “I” and everyone's own choice. When the conversation goes on at this level, the fuse falls out of the speeches about the war.

When the conversation goes on at this level, the fuse falls out of the speeches about the war.

All this is true. But let's be objective: in pre-war Russia, with its "we can repeat" "Leningrad Tales" did not become a national bestseller or teenage mainstream at all, I guess most children do not care about me (or let's say more academically: my books are not so important to them).

I think that in my survey it turned out that all children are against the war, because all children are against the war. Let's talk about "ambivalent".

- Well, that's bad, but it's right. - Why is it right? “They would have attacked us sooner or later. - Wait, explain your idea. Who do you mean, who are "they"? — America. “Wait, I lost my thread. How is America? How do you understand it? After all, it is happening in Ukraine. America supports her. - And who do you support? (quick and cocky) I support my country. How do you express your support? - Not. - Why?

Long pause.

— Well…

Long pause.

— Should I answer?

— No, no, you don't have to answer everything. Let's go further?

Nods. Let's go further. The unanswered question remains behind, but does not disappear. He's like a thorn.

Read more

Propaganda does not answer their main, genuine questions. If I am against the war, then what does it mean that I am against Russia? I don't like my country? So I'm for the war? The circle never closes.

- I try not to think, to deviate from this topic.

- I try not to delve into.

— Discussed with friends. - What do you think? Either Putin is a fool or Zelensky is a fool. Both are to blame. And peaceful people are not to blame.

Their questions require clear, definite answers. That is why such questions are called "childish". Teenagers do not mumble "everything is complicated", "everything is not so simple" or "we will never know the whole truth anyway." They demand an answer. Uncomplicated, unambiguous, durable, right now, and the fact that they don’t have it twists their brains a lot.

Someone jumps to counter-accusations. This is also protection:

- This is just racism. - What do you mean? “To punish people for simply living in the country where they were born. A year ago, the same Americans fought for blacks. It's embarrassing, embarrassing.

After a while, I have a common working title for these various mental efforts: what to do when your mother is a cannibal? From this question and adults are now hiding.

— And Butch? “I don't believe that Russian soldiers can do this. I just don't believe it.

— And Butch? - What would you like!? So that I poured mud on my country?

— And Butch? - You are completely confused. Buchu has been set up.

"Russia is a great country," "Russia has a great culture," "America hates Russia," "and we don't need them either"—all the shield phrases, shield phrases, one way or another, come down to these. This struggle is hardest and most painful for those whose fathers, stepfathers, uncles, brothers are fighting in the Russian army right now.

In 442 BC, Sophocles wrote a play about a girl who even goes to her death in order to humanly bury her dead brother Polynices, although she is told: he died as a criminal, for a wrong deed, he is covered with shame. At 19Jean Anouilh wrote a version of this play in 1943.

If I am against people dying (and what is against - here, thank God, there is always consensus), does that mean I am against war? And if I am against the war, then I am against my dad, uncle, stepfather, brother?

— Such conversations and questions offend me.

And I understand that this is the voice of Antigone.

Call her by your name

Antigone has a simple Russian name. Included in Russia in the top five most popular.

But I do not ask anyone for surnames, school numbers. I do not make video or audio recordings, I write with a pen on paper. Sometimes I stop the conversation: wait, I want to write down everything in detail. Or: wait, I think you are saying something very important now. I ask questions to which there can be no "right" or "wrong" answer, but only - just an answer. Nevertheless, the war goes on, the very word “war” in Russia is punishable, it happens that teachers write denunciations about their own students, students write about teachers or classmates, the words “fear” and “fear” flash in conversations in a way that should not be children. I am responsible for the stories entrusted to me.

I ask questions to which there can be no "right" or "wrong" answer, but only - just an answer. Nevertheless, the war goes on, the very word “war” in Russia is punishable, it happens that teachers write denunciations about their own students, students write about teachers or classmates, the words “fear” and “fear” flash in conversations in a way that should not be children. I am responsible for the stories entrusted to me.

— Can we call you something else, whatever you want?

She thinks for a few long moments, then shakes her head and says: no, if I'm ***, then I'm ***.

I write by hand: ***, 11 years old.

*** tells how she argued about the war with a classmate, the boy threatened to beat her if she didn't shut up. He admitted his impotence, he realized with satisfaction ***. But she adds that she was ready to fight for her convictions.

Then I type on the computer. My hands are hanging on the *** words "just a stupid boy." The thought that the boy might not be so stupid, and that his parents might recognize ***, then snitch, then. .. I go back to the beginning, erase the name.

.. I go back to the beginning, erase the name.

Maybe I should call my interlocutors just “girl”, just “boy”? Or will I thereby, on the contrary, imperceptibly cross some fatal boundary, succumb to the state rhetoric of depersonalization, which, due to the inertia of free fall, always turns into dehumanization, dehumanization? Russian official Lavrov called people who died in Ukraine collateral damage, Putin - "expendable material", and people who disagree with him - midges. In the Nazi camps, the corpses of the slaughtered people were called "figures."

She is not a midge. She lives in St. Petersburg, she is eleven, she demanded to be called by her name. And yet I write: girl.

Small

- I remember February 24 very well. I went to school. I envied the kids. Because they don't understand what's going on.

My youngest interlocutors are five years old. For them, the usual streets seem to have not changed. No one told me about Russian flags, perhaps these flags are too high for them. A small child usually looks down, his gaze is closer to the ground, to the sidewalk. He notices the bugs, the complicated life in the grass, the drawings on the pavement.

A small child usually looks down, his gaze is closer to the ground, to the sidewalk. He notices the bugs, the complicated life in the grass, the drawings on the pavement.

- There was a flag, I've never seen one like it before. - What did he look like? - Blue and yellow, two stripes. What is this flag? - This is Ukrainian. Where did you see? - I saw someone draw it with crayons.

Five-year-olds do not have telephones. On the streets they notice changes that are important and valuable in five years, this has nothing to do with the war:

- New stalls on wheels - with corn and candy.

And if they do, they don't see the connection. They do not understand what it is:

- There were a lot of people with black heads. In helmets.

At the age of five, the very concept of war is not quite clear, just as the concept of death is also not clear - at five years, all people are immortal. It is only clear that war is something that should not be.

— Why they are fighting, I don't know. They can agree, but they don't want to. It is very bad that people are dying, it is necessary to agree.

They can agree, but they don't want to. It is very bad that people are dying, it is necessary to agree.

One six-year-old girl is an exception, she knows that there is a war going on now. “We were probably careless,” her mother says, embarrassed. “When it all started, we had friends at home. We discussed this endlessly. Maybe it's wrong." The girl doesn't want to talk to me. But she allows her mother to send her drawings, which she has made since the beginning of this war.

A collage of drawings by one of the interlocutors, Yulia Yakovleva. None of my youngest interlocutors know anymore that there is a war going on, that their country has attacked a neighboring one. Their parents outlined them in a magic circle of silence. Are the parents right? Wrong? They don't have the language to talk about the war with a five or six year old child. It's one thing - war in general. Another thing is this war: which your country unleashed. How to tell a five-year-old man that our country has attacked a neighboring one? How to explain why? Here they are silent.

- I was offended by my dad. He didn't buy me a pirate gun. He said he would buy any toy because it was my birthday. I didn't buy a gun. “Why didn’t you buy a gun, did he tell you?” “He said it was wrong. - What's wrong? “Dad said not to play with pistols.

“He didn't understand what happened,” another mother warns me about her little son. “But now he is very afraid when dad leaves, when adults go somewhere.”

Bombs do not fall on these children, as in Ukraine. They never heard the explosions of shells. We did not see the destroyed houses. They don't even know there's a war going on. But the war still seeps through to them through the looks and conversations of adults, through actions, microscopic decisions that you yourself don’t notice, the war slowly permeates the protective felt of a happy childhood.

For a five-year-old who doesn't know about her, this war goes like this:

- Mom is now looking at the phone all the time.

This boy

— One boy joked about Ukrainians at the lesson. Do you remember what he said? - Not. "Dill", but I don't remember anymore. - Did it seem unusual to you? - Yes. - Why? The teacher started crying after that.

Do you remember what he said? - Not. "Dill", but I don't remember anymore. - Did it seem unusual to you? - Yes. - Why? The teacher started crying after that.

- He said in one breath that his family lives in Kherson and that it is necessary to "let the Chechens go there so that they [rape] everyone there, so that we have a country of tame Chechens at our side."

- One boy went around and showed everyone a video under "Katyusha", there were corpses of Ukrainian soldiers.

"This boy" is, if not in every class, then in every school for sure. I listened to my interlocutors and thought that I myself knew this boy. I also studied with him, that his thought is not dormant, was heralded by a sudden laughter from the back of the desk. This boy is the first to try smoking, obscene remarks fall out of his mouth, more terrible than obscene, but this is not always and not for everyone. He can also mimic. It was not Putin's propaganda that gave birth to this boy. He is eternal. Our grandchildren will also study with him. It will end only with the world. Usually, "this boy" is held back and boxed in by social disapproval - classmates, first of all. When society is split, ethics is twisted, the social contract is cracked, then the energy of “this boy” breaks out, triumphs. Time itself then seems to be the time of "these boys."

Our grandchildren will also study with him. It will end only with the world. Usually, "this boy" is held back and boxed in by social disapproval - classmates, first of all. When society is split, ethics is twisted, the social contract is cracked, then the energy of “this boy” breaks out, triumphs. Time itself then seems to be the time of "these boys."

- They demanded that I kneel before them and apologize. - What did they look like? - Well. Boys. What do boys look like?

This energy can be called "xenophobic", but that would make things too easy. Xenophobia is just one of the forms this dark matter takes. From it you can sculpt anything. For example, the army.

Much has already been said about the fact that Putin's army, which is fighting in Ukraine, is recruited mainly from depressed or semi-depressive regions, on the outskirts, in the outback, in bearish corners. If you know only this, then a kind of chthonic swamp, teeming with horror, is drawn, on the surface of which Moscow, St. Petersburg and several million-plus cities float like silver plaques. But "Leningrad Tales" introduced me to this Russia too: "We're going to school, on the first cart there is firewood for the school, on the second - the children themselves." Therefore, I know something else: what a colossal role in Russia, rural schools and tiny libraries are played by caring adults. Circles of light from each such person diverge far. “Please come talk,” one woman writes to me. “Children are covered with frost.” We will transfer and warm one by one.

Petersburg and several million-plus cities float like silver plaques. But "Leningrad Tales" introduced me to this Russia too: "We're going to school, on the first cart there is firewood for the school, on the second - the children themselves." Therefore, I know something else: what a colossal role in Russia, rural schools and tiny libraries are played by caring adults. Circles of light from each such person diverge far. “Please come talk,” one woman writes to me. “Children are covered with frost.” We will transfer and warm one by one.

It's not about geography or even just about poverty. In Moscow or St. Petersburg, "these boys" also exist. They grow among professors, and among workers, and in complete families, and among single mothers. They are also girls. In general, we are talking, and at some point I understand that the child is screaming - at me, at the world, at the fact that life is like this:

- No one is to blame for hatred! I hate Chechens! Tajiks! I don't care about these Ukrainians! I hate a lot! Yes! I am a bad man! But I don’t walk around and yell: die, creatures! Then I'll be a monster. It is not those who hate who are to blame. Blame the monsters. Those who implement this hatred are to blame. These people are just monsters.

It is not those who hate who are to blame. Blame the monsters. Those who implement this hatred are to blame. These people are just monsters.

The person who understood this is 13 years old.

From the very beginning of the war, the most severe military censorship was introduced in Russia. The very word "war" in one day became illegal. And on the same day, adults, my friends, my acquaintances, my colleagues switched to the language of omissions, reticences, allegories and so quickly achieved virtuosity, as if they had been preparing for a long time. The ease with which this happened was terrifying. Speech has mutated, and even that which cannot be heard by state ears: conversations of friends, conversations in private, conversations in the kitchen, conversations on a walk. They had a distinct imprint on them: now they were talks during the war.

No one calls the war with Ukraine the way the state suggested: “a special military operation”.

In general, why do you think the authorities needed this expression? What's the point of this? I asked questions to my interlocutors. Opinions are the same regardless of age:

Opinions are the same regardless of age:

- The word "war" is too scary.

— Because war is something big, serious, important.

- Because if you say war, then that's it, there is no turning back.

- If you say "war", people will immediately get scared: war!

- Because war is a disaster.

- Bureaucracy, PR, all together.

— So that there are no unnecessary conversations and identifications with the years 1941-1945 inside the country.

Children avoid the word "war" out loud. And in every conversation I call it the way the interlocutor first called it: “these events”, “kapets”, “all this horror”, “what is happening”, “everything” (“when everything happened”), “this”.

Look, I notice more than once in passing that nobody else hears you and me, but you and I still say: “what is happening.” Or "events". The person thinks for a moment, nods, sighs, swallows, looks away. But even after that he does not call the war "war". Or he forces himself, but then the word gets in the way, does not give in to the mouth. It's so short, two-syllable, convenient, but so hard to say.

It's so short, two-syllable, convenient, but so hard to say.

Today's greatest horror connoisseur Stephen King named his best novel about childhood fear "It" for a reason. It. It.

War is "it".

Macbeth killed the dream

One day I have a dream and I understand that it is about war. I dream of a cat with kittens. I make many small unnecessary movements to move the kittens to another place that I myself do not know. And then the dog comes and eats them all.

Bombs do not fall on these children. Their houses were not destroyed. They were not wounded by shell fragments. Some had to leave with their parents, but even then it was not an escape from the shelling. Their injury is referred to as the "witness injury". The trauma of a person who sees, knows and cannot influence anything. So far, it can't.

Read more

— A plane flew over me, it rumbled, I became really scared, although I know that it's just a plane, no bombs come from there.