Jack and the beanstalk meaning

A Summary and Analysis of ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ – Interesting Literature

LiteratureBy Dr Oliver Tearle

What is the story of ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ all about? And what is the moral of this story? It’s one of the best-known and best-loved fairy tales in Britain, and also – as we will see – one of the oldest.

‘Jack and the Beanstalk’: plot summary

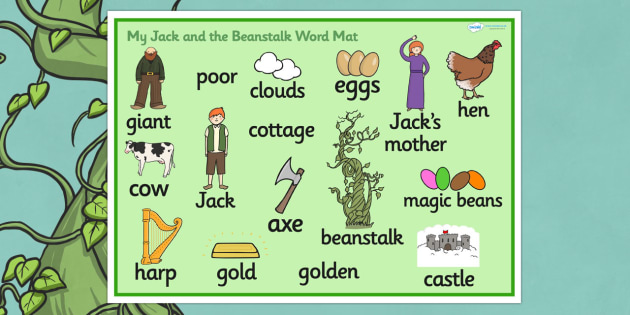

First, a very short summary of the plot of the Jack and the beanstalk tale (or a refresher for those who are some way out of the nursery). Jack is a young and rather reckless boy who lives with his widowed mother. They become increasingly poor – thanks partly to Jack’s own carelessness – until the day comes when all they have left is a cow, which Jack’s mother tells him to take to the market to sell for money. Unfortunately, while on his way into town, Jack meets a bean dealer who says he will pay Jack a hat full of magic beans for the cow.

Jack, delighted to have been made an offer on the cow before he’s even reached the market, lives up to his reckless reputation once again and agrees to the deal. He returns home with no cow and no money and only a hat full of beans to show for the journey; his mother, needless to say, is less than happy with this outcome, and hurls the beans out into the garden in her anger. They both retire to bed without having eaten, as they have no food left.

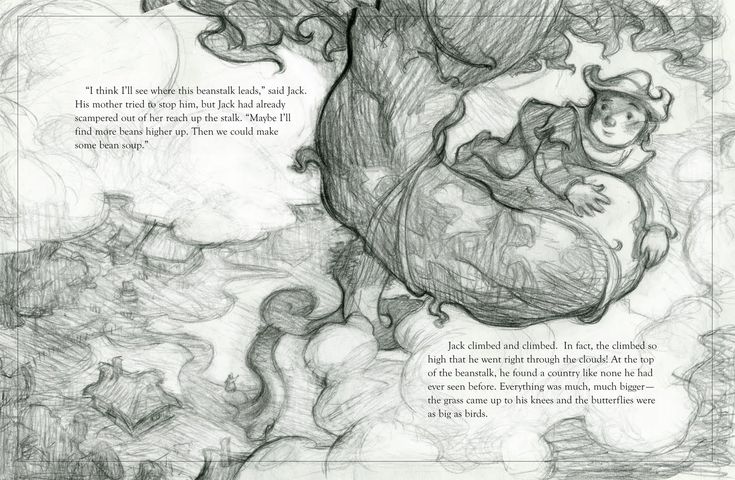

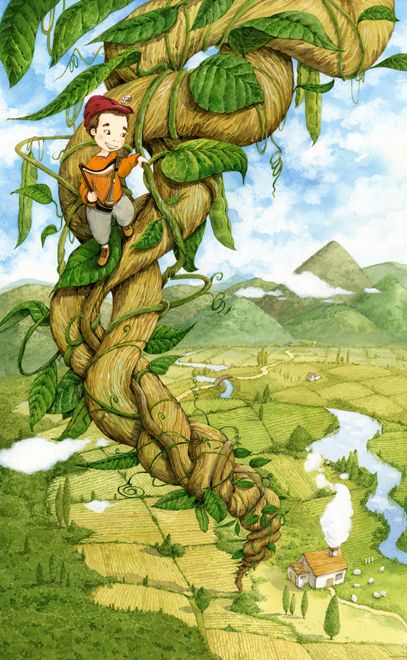

However, when Jack wakes the next morning, he finds that the magic beans scattered across the garden have grown into a giant beanstalk outside his window. He promptly climbs it – as you do – and finds a whole new land at the top. Wandering among this land, Jack comes upon a huge castle and sneaks his way inside. The giant, who owns the castle, returns home and smells Jack, proclaiming: ‘Fee-fi-fo-fum! I smell the blood of an English man: Be he alive, or be he dead, I’ll grind his bones to make my bread.’ Jack steals a sack of gold from the giant’s castle before swiftly making his escape back down the beanstalk.

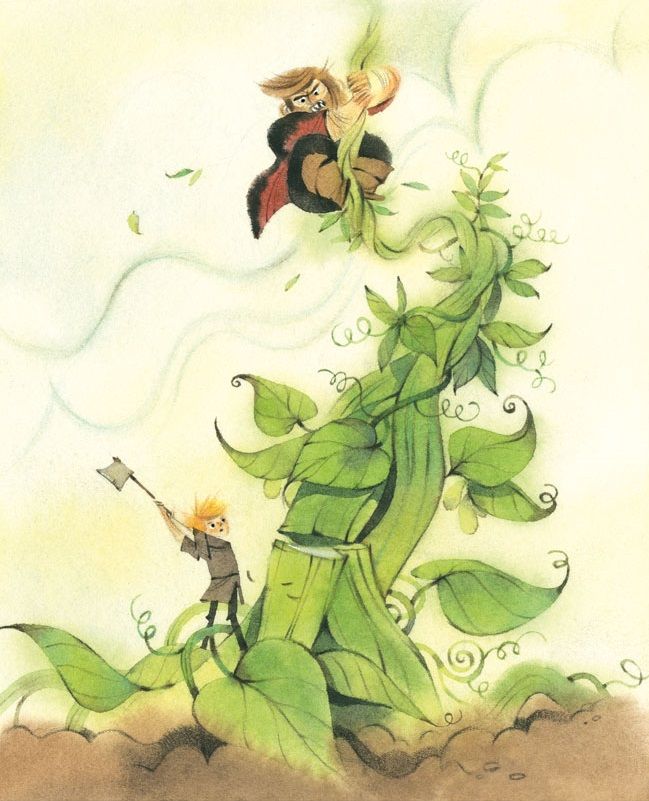

However, this is a fairy tale, which wouldn’t be complete without obeying the ‘rule of three’. So, Jack duly climbs the beanstalk twice more and steals from the giant twice more. The giant wakes when Jack is leaving the castle the third time, and chases Jack back down the beanstalk. The quick-thinking Jack calls for his mother to throw down an axe for him; before the giant reaches the ground, Jack chops down the beanstalk, causing the giant to fall to his death. Jack and his mother live happily ever after, and are never poor or hungry again, thanks to Jack’s burgling skills. Who says crime doesn’t pay?

So, Jack duly climbs the beanstalk twice more and steals from the giant twice more. The giant wakes when Jack is leaving the castle the third time, and chases Jack back down the beanstalk. The quick-thinking Jack calls for his mother to throw down an axe for him; before the giant reaches the ground, Jack chops down the beanstalk, causing the giant to fall to his death. Jack and his mother live happily ever after, and are never poor or hungry again, thanks to Jack’s burgling skills. Who says crime doesn’t pay?

‘Jack and the Beanstalk’: analysis

‘Jack and the Beanstalk’, like a great number of fairy tales, has a curious and complicated history. The story’s earliest incarnation of in print was as ‘The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean’ in 1734; it underwent some tidying up (with a large dose of moralising added for good measure) in 1807 in Benjamin Tabart’s ‘The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk’, although the elements we most associate with the story were given the definitive treatment in an 1890 version. All this would suggest that the tale of Jack and the beanstalk is relatively recent, especially when so many other classic fairy tales have medieval prototypes in world literature.

All this would suggest that the tale of Jack and the beanstalk is relatively recent, especially when so many other classic fairy tales have medieval prototypes in world literature.

But in fact, researchers at the universities in Durham and Lisbon believe that the essential story of ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ dates back over 5,000 years, or two whole millennia before Homer. This prototype of Jack’s beanstalk antics is classified by folklorists as ATU 328 The Boy Who Stole Ogre’s Treasure. Like ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ and ‘Beauty and the Beast’, this story appears to be thousands, rather than hundreds, of years old.

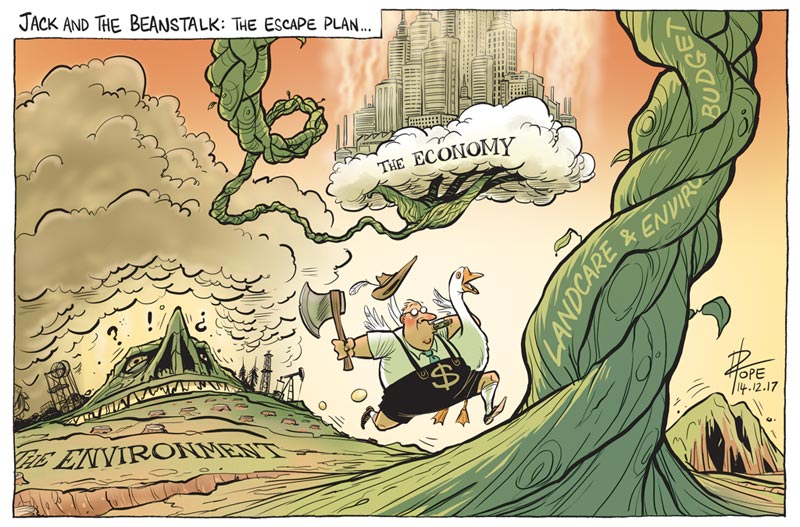

As we implied above, there is something immoral in the story’s essential message: steal from others to get yourself out of poverty, and you will triumph. The killing of the giant is self-defence, admittedly, but we can see why Victorians might have been a little queasy around the central thrust of the story.

So in some versions of the tale, such as the one the Opies include in The Classic Fairy Tales

, a back-story is included, which informs us that the giant actually stole his riches from Jack’s father, whom he killed out of jealousy and greed. The giant’s wealth, then, is ill-gotten, and Jack, in stealing from him, is in fact only reclaiming what is rightfully his. This addition makes the tale more palatable to younger readers whose parents want to use the fairy tale for moral instruction as well as entertainment, and, after all, Jack is still far from perfect. His lack of foresight and rashness lead to his selling the cow for such a low price.

The giant’s wealth, then, is ill-gotten, and Jack, in stealing from him, is in fact only reclaiming what is rightfully his. This addition makes the tale more palatable to younger readers whose parents want to use the fairy tale for moral instruction as well as entertainment, and, after all, Jack is still far from perfect. His lack of foresight and rashness lead to his selling the cow for such a low price.

‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ has endured because it contains so many of the classic ingredients of the fairy tale: the plucky young hero who’s down on his luck, the evil villain, the happy ending. And it’s been around for a long time: if those scholars are correct in their analysis, the original for the story has been around for almost twice as long as Homer’s Iliad. That’s some literary pedigree.

The author of this article, Dr Oliver Tearle, is a literary critic and lecturer in English at Loughborough University. He is the author of, among others, The Secret Library: A Book-Lovers’ Journey Through Curiosities of History and The Great War, The Waste Land and the Modernist Long Poem.

Image: via Wikimedia Commons.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Tags: Analysis, Children's Literature, Classics, Fairy Tales, Jack and the Beanstalk, Literary Criticism, Literature, Summary

The Original Story of “Jack and the Beanstalk” Was Emphatically Not for Children

If, like me, you once tried to plant jelly beans in your backyard in the hopes that they would create either a magical jelly bean tree or summon a giant talking bunny, because if it worked in fairy tales it would of course work in an ordinary backyard in Indiana, you are doubtless familiar with the story of Jack and the Beanstalk, a tale of almost but not quite getting cheated by a con man and then having to deal with the massive repercussions.

You might, however, be a little less familiar with some of the older versions of the tale—and just how Jack initially got those magic beans.

The story first appeared in print in 1734, during the reign of George II of England, when readers could shill out a shilling to buy a book called Round about our Coal Fire: Or, Christmas Entertainments, one of several self-described “Entertaining Pamphlets” printed in London by a certain J. Roberts. The book contained six chapters on such things as Christmas Entertainments, Hobgoblins, Witches, Ghosts, Fairies, how people were a lot more hospitable and nicer in general before 1734, and oh yes, the tale of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean, and how he became Monarch of the Universe. It was ascribed to a certain Dick Merryman—a name that, given the book’s interest in Christmas and magic, seems quite likely to have been a pseudonym—and is now available in what I am assured is a high quality digital scan from Amazon.com.

Roberts. The book contained six chapters on such things as Christmas Entertainments, Hobgoblins, Witches, Ghosts, Fairies, how people were a lot more hospitable and nicer in general before 1734, and oh yes, the tale of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean, and how he became Monarch of the Universe. It was ascribed to a certain Dick Merryman—a name that, given the book’s interest in Christmas and magic, seems quite likely to have been a pseudonym—and is now available in what I am assured is a high quality digital scan from Amazon.com.

(At $18.75 per copy I didn’t buy it. You can find plenty of low quality digital scans of this text in various places in the internet.)

The publishers presumably insisted on adding the tale in order to assure customers that yes, they were getting their full shilling’s worth, and also, to try to lighten up a text that starts with a very very—did I mention very—lengthy complaint about how nobody really celebrates Christmas properly anymore, by which Dick Merryman means that people aren’t serving up as much fabulous free food as they used to, thus COMPLETELY RUINING CHRISTMAS FOR EVERYONE ELSE, like, can’t you guys kill just a few more geese, along with complaining that people used to be able to pay their rent in kind (that is, with goods instead of money) with the assurance that they’d be able to eat quite a lot of it at Christmas. None of this is as much fun as it sounds, though the descriptions of Christmas games might interest some historians.

None of this is as much fun as it sounds, though the descriptions of Christmas games might interest some historians.

Also, this:

As for Puffs in the Corner, that is a very harmless Sport, and one may ramp at it as much as one will; for at this Game when a Man catches his Woman, he may kiss her ’till her Ears crack, or she will be disappointed if she is a Woman of any Spirit; but if it is one who offers at a Struggle and blushes, then be assured she is a Prude, and though she won’t stand a Buss in publick, she’ll receive it with open Arms behind the Door, and you may kiss her ’till she makes your Heart ake.

….Ok then.

This is all followed by some chatter and about making ladies squeak (not a typo) and what to do if you find two people in bed during a game of hide and seek, and also, hobgoblins, and witches, and frankly, I have to assume that by the time Merryman finally gets around to telling Jack’s tale—page 35—most readers had given up. I know I almost did.

I know I almost did.

Image from Round about our Coal Fire: Or, Christmas Entertainments (1734)

The story is supposedly related by Gaffer Spiggins, an elderly farmer who also happens to be one of Jack’s relatives. I say, supposedly, in part because by the end of the story, Merryman tells us that he got most of the story from the Chit Chat of an old nurse and the Maggots in a Madman’s brain. I suppose Gaffer Spiggins might be the madman in question, but I think it’s more likely that by the time he finally got to the end, Merryman had completely forgotten the start of his story. Possibly because of Maggots, or more likely because the story has the sense of being written very quickly while very drunk.

In any case, being Jack’s relative is not necessarily something to brag about. Jack is, Gaffer Spiggins assures us, lazy, dirty, and dead broke, with only one factor in his favor: his grandmother is an Enchantress. As the Gaffer explains:

for though he was a smart large boy, his Grandmother and he laid together, and between whiles the good old Woman instructed Jack in many things, and among the rest, Jack (says she) as you are a comfortable Bed-fellow to me —

Cough.

Uh huh.

Anyway. As thanks for being a good bedfellow, the grandmother tells Jack that she has an enchanted bean that can make him rich, but refuses to give him the bean just yet, on the basis that once he’s rich, he will probably turn into a Rake and desert her. It’s just barely possible that whoever wrote this had a few issues with men. The grandmother then threatens to whip him and calls him a lusty boy before announcing that she loves him too much to hurt him. I think we need to pause for a few more coughs, uh huhs and maybe even an AHEM. Fortunately before this can all get even more awkward and uncomfortable (for the readers, that is), Jack finds the bean and plants it, less out of hope for wealth and more from a love of beans and bacon. In complete contrast to everything I’ve ever tried to grow, the plant immediately springs up smacking Jack in the nose and making him bleed. Instead of, you know, TRYING TO TREAT HIS NOSEBLEED the grandmother instead tries to kill him, which, look, I really think we need to have a discussion about some of the many, many unhealthy aspects of this relationship. Jack, however, has no time for that. He instead runs up the beanstalk, followed by his infuriated grandmother, who then falls off the beanstalk, turns into a toad, and crawls into a basement—which seems to be a bit of an overreaction.

Jack, however, has no time for that. He instead runs up the beanstalk, followed by his infuriated grandmother, who then falls off the beanstalk, turns into a toad, and crawls into a basement—which seems to be a bit of an overreaction.

In the meantime, the beanstalk has now grown 40 miles high and already attracting various residents, inns, and deceitful landlords who claim to be able to provide anything in the world but when directly asked, admit that they don’t actually have any mutton, veal, or beef on hand. All Jack ends up getting is some beer.

Which, despite being just brewed, must be amazing beer, since just as he drinks it, the roof flies off, the landlord is transformed into a beautiful lady, with a hurried, confusing and frankly not all that convincing explanation that she used to be his grandmother’s cat. As I said, amazing beer. Jack is given the option of ruling the entire world and feeding the lady to a dragon. Jack, sensibly enough under the circumstances, just wants some food. Various magical people patiently explain that if you are the ruler of the entire world, you can just order some food. Also, if Jack puts on a ring, he can have five wishes. It will perhaps surprise no one at this point that he wishes for food, and, after that, clothing for the lady, music, entertainment, and heading to bed with the lady. The story now pauses to assure us that the bed in question is well equipped with chamberpots, which is a nice realistic touch for a fairy tale. In the morning, they have more food—a LOT more food—and are now, apparently, a prince and princess—and, well. There’s a giant, who says:

Various magical people patiently explain that if you are the ruler of the entire world, you can just order some food. Also, if Jack puts on a ring, he can have five wishes. It will perhaps surprise no one at this point that he wishes for food, and, after that, clothing for the lady, music, entertainment, and heading to bed with the lady. The story now pauses to assure us that the bed in question is well equipped with chamberpots, which is a nice realistic touch for a fairy tale. In the morning, they have more food—a LOT more food—and are now, apparently, a prince and princess—and, well. There’s a giant, who says:

Fee, fow, fum—

I smell the blood of an English-Man,

Whether he be alive or dead,

I’ll grind his Bones to make my Bread.

I would call this the first appearance of the rather well known Jack and the Beanstalk rhyme, if it hadn’t been mostly stolen from King Lear. Not bothering to explain his knowledge of Shakespeare, the giant welcomes the two to the castle, falls instantly in love with the princess, but lets them fall asleep to the moaning of many virgins. Yes. Really. The next morning, the prince and princess eat again (this is a story obsessed with food), defeat the giant, and live happily ever after—presumably on top of the beanstalk. I say presumably, since at this point the author seems to have entirely forgotten the beanstalk or anything else about the story, and more seems interested in swiftly wrapping things up so he can go and complain about ghosts.

Yes. Really. The next morning, the prince and princess eat again (this is a story obsessed with food), defeat the giant, and live happily ever after—presumably on top of the beanstalk. I say presumably, since at this point the author seems to have entirely forgotten the beanstalk or anything else about the story, and more seems interested in swiftly wrapping things up so he can go and complain about ghosts.

Merryman claimed to have heard portions of this story from an old nurse, presumably in childhood, and the story does have a rather childlike lack of logic to it, particularly as it springs from event to event with little explanation, often forgetting what happened before. The focus on food, too, is quite childlike. But with all of the talk of virgins, bedtricks, heading to bed, sounds made in bed, and violence, not to mention all of the rest of the book, this does not seem to be a book meant for children. Rather, it is a book that looks back nostalgically at a better, happier time—read: prior to the reign of the not overly popular George II of Great Britain. I have no proof that Merryman, whatever his real name was, participated in the Jacobite rebellion that would break out just a couple of years after this book’s publication, but I can say he would have felt at least a small tinge of sympathy, if not more, for that cause. It’s a book that argues that the wealthy are not fulfilling their social responsibilities, that hints darkly that the wealthy can be easily overthrown, and replaced by those deemed socially inferior.

I have no proof that Merryman, whatever his real name was, participated in the Jacobite rebellion that would break out just a couple of years after this book’s publication, but I can say he would have felt at least a small tinge of sympathy, if not more, for that cause. It’s a book that argues that the wealthy are not fulfilling their social responsibilities, that hints darkly that the wealthy can be easily overthrown, and replaced by those deemed socially inferior.

So how exactly did this revolutionary tale get relegated to the nursery?

We’ll chat about that next week.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

citation

"Jack and the Beanstalk". English fairy tale

Once upon a time there was a poor woman. Her husband died, and she was left alone in the world with her son. The boy's name was Jack, he was her only joy, she indulged all his whims and spared nothing for him. And Jack grew up a fidget, did not like to work, and he was still small. Year by year it became more and more difficult for them, gradually they sold everything they had, leaving only their beloved cow Belyanka, who both watered and fed them. Jack sold milk at the market in the city, that's how they lived.

Year by year it became more and more difficult for them, gradually they sold everything they had, leaving only their beloved cow Belyanka, who both watered and fed them. Jack sold milk at the market in the city, that's how they lived.

But then the day came when Belyanka, who was already quite a few years old, gave almost not a drop of milk; they had no money left at all, and they simply did not know how to live on. The poor mother was in despair.

– Apparently, we will have to sell our Belyanka. It’s a pity for me to part with her, just to tears, but there is no other way out, we don’t have to die of hunger.

Jack did not have to be persuaded for a long time.

“All right, mother,” he said. - Today is just a market day, I will quickly sell it.

He tied a rope around the cow's neck and led her out of the yard.

They are walking together on the road to the city and suddenly they meet a strange old man.

“Good morning, Jack,” the old man says.

“Good morning,” the boy replies, wondering how the old man knows his name.

– Where are you in such a hurry? the old man asks.

“To the market to sell a cow,” Jack answers.

– Really? This is just for you, - the old man smiled. “Tell me, how many beans do you need to take to make five.”

“Two in each hand and another in your mouth,” Jack replied; small he was not a mistake.

“That's right,” said the old man. “Here they are, beans, look,” and he took out five outlandish beans from his pocket. - Since you're so smart, I'm not averse to swapping with you: I'll get a cow, you'll get beans!

- Swap Belyanka for these beans? Are you laughing at me?

- Uh, you don't know what those beans are. Plant them in the ground in the evening, and by morning they will grow right up to the sky.

- Yeah, well? Truth? Jack was surprised.

– I tell you exactly! And if not, take your cow back.

– Well, let's go, – agreed Jack, gave Belyanka to the old man, and put the beans in his pocket.

Jack turned back and returned home before dark, because he had to walk very far.

Are you back yet, Jack? mother was surprised. - I see Belyanka is not with you. So you sold it. How much did they give you for it?

“You'll never guess, Mom,” Jack replied.

– Oh, right? Oh, my good one. Five pounds? Ten? Fifteen? Well, not twenty!

- I'm telling you, you won't guess. And what do you say to this? and Jack showed her the beans. – They are magical, plant them in the evening and…

– What?! the mother exclaimed. “Are you really such a blockhead, such a fool, such a simpleton, that you gave away my Belyanka, the most dairy cow in the area, and besides, fattened and well-groomed, for a handful of some miserable beans. It is for you! It is for you! It is for you! And your wonderful beans - get them out the window! And march to bed, forget about dinner, you won’t get a piece today!

Sad, Jack went up to his attic, to a small room. He was sad and hurt: he felt sorry for his mother, and he was hungry. For a long time he lay and sighed, and finally fell asleep.

For a long time he lay and sighed, and finally fell asleep.

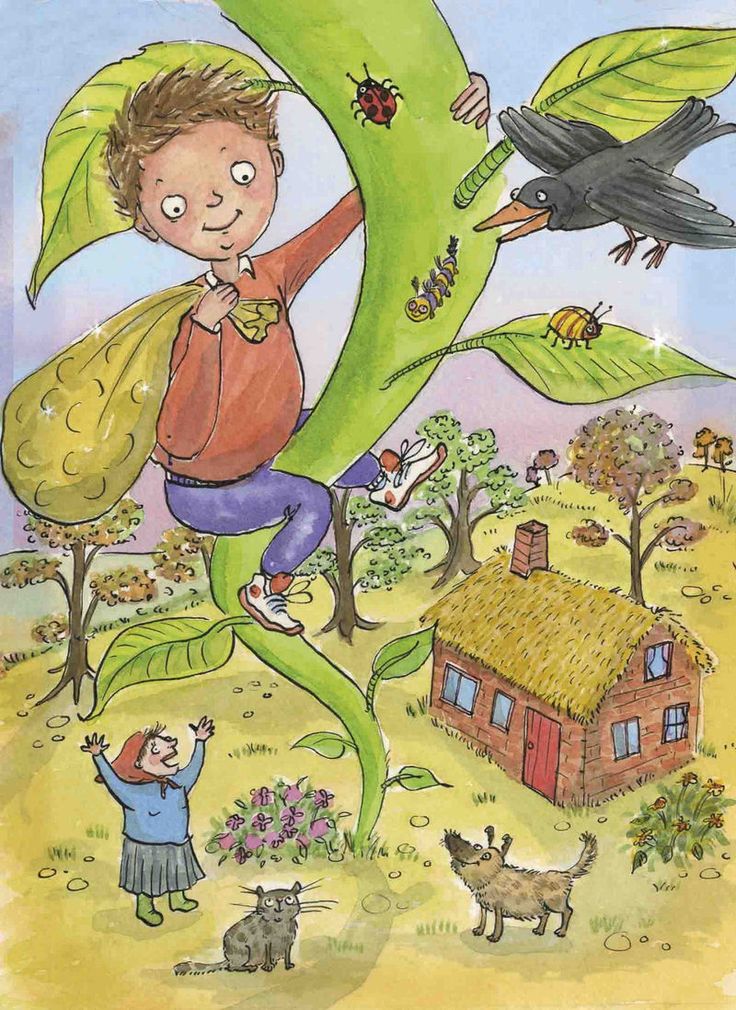

And in the morning, when Jack woke up, he was terribly surprised. The sun illuminated only one corner, and the rest of the room was dark and shaded. Jack jumped up, dressed and ran to the window. And what did he see? The beans that his mother threw yesterday out of the window into the garden sprouted, and the great beanstalk rose higher and higher until it reached the sky; so the old man, it turns out, spoke the truth.

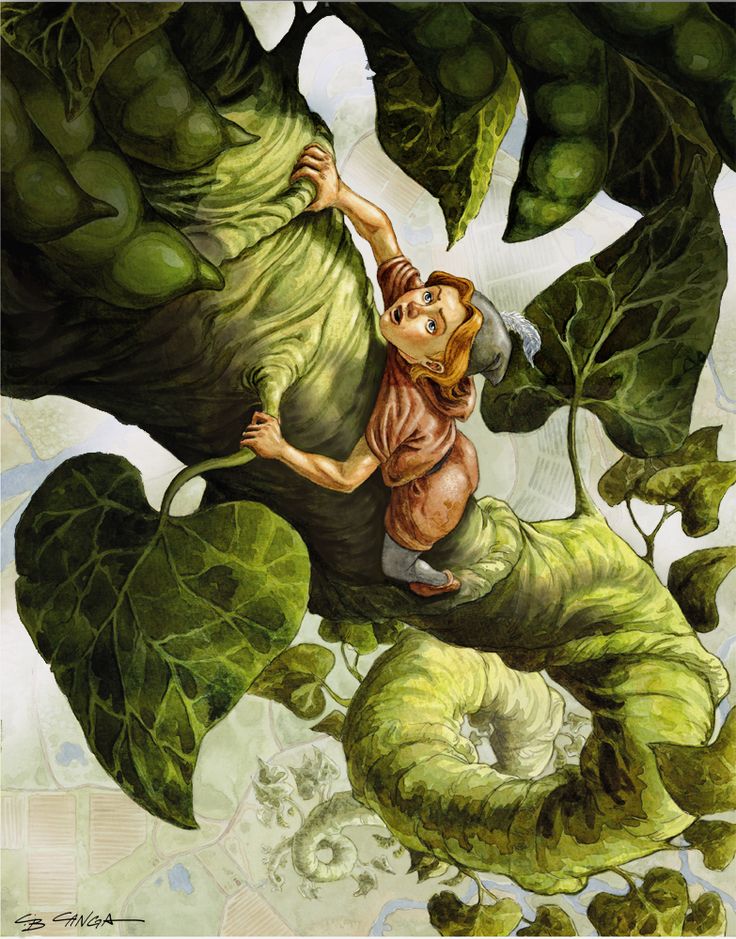

The beanstalk grew right next to the window of his room, so it was easy for Jack to climb onto it. He began to climb it, as if on a ladder, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, until he finally reached the very sky. There he saw a large and wide road, straight as an arrow.

Jack went along this road and walked and walked and walked until he came to a huge, huge house, and at the threshold of it stood a huge, huge woman.

“Good morning, ma'am,” Jack said very politely. “Would you be so kind as to give me something to eat?”

“Would you be so kind as to give me something to eat?”

After all, Jack, as you remember, went to bed without dinner and was now as hungry as a wolf.

– Would you like to have breakfast? - said a huge, enormous giantess. “They’ll eat you for breakfast if you don’t get out of here as soon as possible.” My husband is a cannibal giant, and his favorite dish is boys fried in breadcrumbs. Better leave while you're still intact, he'll be back any minute.

“Oh ma'am, please give me something to eat,” Jack insisted. “I haven’t had poppy dew in my mouth since yesterday morning, so I don’t care if they fry me or starve to death.

The giantess was, in general, a kind woman. She took pity on the boy, took him to the kitchen and gave him a slice of bread with cheese and a jug of milk. But before Jack had time to eat even half of breakfast, when suddenly - top! - top! - top! The whole house shook from someone's footsteps.

– Lord! Yes, this is my old man, the giantess gasped. - What should I do? Come on, jump over here!

- What should I do? Come on, jump over here!

And just as she pushed Jack to the stove, the ogre himself entered. Well, he was huge, in one word - a giant! Three calves were dangling from his belt, tied by his legs. The cannibal untied them, threw them on the table and said:

– Hey wife, fry me some for breakfast. Mmm, what does it smell like in here?

And the giant began to look around and sniff, happily saying:

Fuh-fuh-fuh-fuh,

I smell a human spirit.

I love to eat people,

Especially boys.

I eat three for breakfast

And I don't miss lunch.

Whether he is fat or thin,

He will not return home.

I need

Boy for dinner today.

– What are you, hubby, you must have imagined. Or maybe it smells like that little boy who was at lunch yesterday. Do you remember that you liked him so much. Go and wash up and change, and I'll make you breakfast.

The ogre came out and Jack wanted to get out of the stove and run away, but the giantess wouldn't let him in.

“Wait until he falls asleep,” she said. After breakfast, he always lies down to take a nap.

The ogre had breakfast, and then he went to a huge chest, took out two bags of gold from it, and began to count the coins. I counted, counted, and fell asleep and snored all over the house.

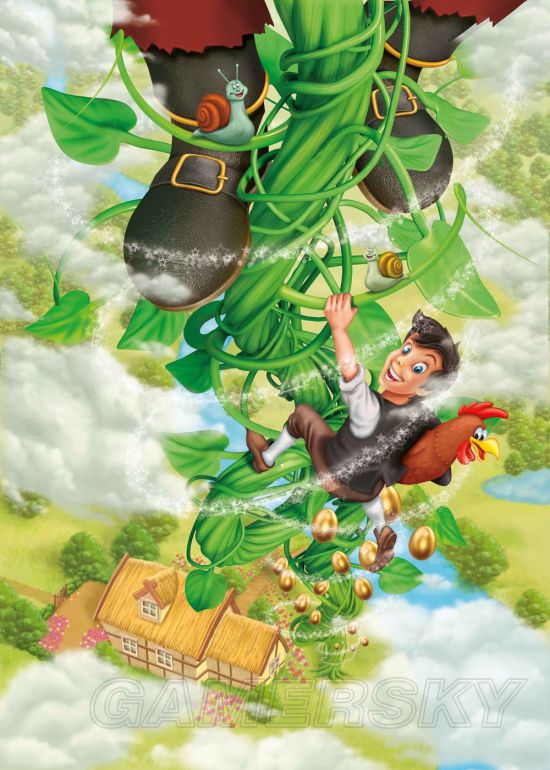

Here the boy quietly got out of the oven and crept on tiptoe past the ogre, taking one of the sacks of gold from him. Jack hurried quickly to his beanstalk, threw the bag down, right into his mother's garden, and he himself began to go down the stalk lower and lower until he was finally at home.

Jack told his mother everything that happened to him, held out a bag of gold and said:

– Well, Mom, wasn't I right about the beans? You see, they are really magical!

And Jack and his mother began to live on the money that was in the giant's bag. But everything in the world comes to an end, and the giant gold has also dried up. Decided then Jack once again try his luck at the top of the beanstalk. One fine morning he got up early, climbed onto the stalk and climbed higher and higher along it. He climbed and climbed and climbed and climbed until he saw a familiar road in front of him - big, wide and straight as an arrow. He went along it and again found himself in front of a huge, huge house. At the door of the house, like last time, there was a huge, enormous woman.

One fine morning he got up early, climbed onto the stalk and climbed higher and higher along it. He climbed and climbed and climbed and climbed until he saw a familiar road in front of him - big, wide and straight as an arrow. He went along it and again found himself in front of a huge, huge house. At the door of the house, like last time, there was a huge, enormous woman.

“Good morning, ma'am,” Jack said matter-of-factly. “Would you be so kind as to give me something to eat?”

“Get out of here, little boy,” the giantess replied, “otherwise my cannibal husband will eat you for breakfast.” Wait a minute, aren't you the same shooter who's been here once before? You know, just that day my husband lost one of his bags of gold.

“Strange things, ma'am,” says Jack. “I really could tell you something about it, but I’m so hungry that I can’t even say a word until I eat at least something.

The giantess became terribly curious, so she let the boy into the house and gave him something to eat. And Jack deliberately chewed as slowly as possible. And here is the top! - top! - top! - the steps of the giant were heard again, and the giantess again hid Jack in the furnace.

And Jack deliberately chewed as slowly as possible. And here is the top! - top! - top! - the steps of the giant were heard again, and the giantess again hid Jack in the furnace.

Then everything was the same as last time. Again the ogre came in and sniffed, and said his 'fuh-fuh-fuh', and ate three roast oxen for breakfast. But after breakfast, the cannibal shouted:

- Wife, bring me a goose that lays golden eggs!

The giantess brought it, and the ogre ordered the chicken:

– Run! and the hen laid an egg of pure gold.

Then the cannibal began nodding again, fell asleep and began to snore so that the whole house trembled. Then Jack slowly got out of the oven, grabbed the chicken, and that was it. But then the hen cackled and woke up the ogre. And just as Jack was running out of the house, he heard the giant shouting:

- Wife, wife! What are you doing with my chicken?

And his wife answered him:

– What did it seem to you, hubby?

Jack did not listen further. With all his legs he rushed to the beanstalk and flew down it like a madman. At home, he showed his mother a magic chicken, shouted: "Rush!" And the hen laid a golden egg. From then on, all Jack had to do was say, "Rush!" - like a hen laying a golden egg for them.

With all his legs he rushed to the beanstalk and flew down it like a madman. At home, he showed his mother a magic chicken, shouted: "Rush!" And the hen laid a golden egg. From then on, all Jack had to do was say, "Rush!" - like a hen laying a golden egg for them.

But Jack did not rest on this. It wasn't long before he decided to try his luck at the top of the beanstalk again. He got up early one fine morning, climbed onto the stalk and climbed higher and higher along it. He climbed and climbed and climbed and climbed until he reached the very top. But this time Jack did not go straight to the ogre's house, but came up with something better. Approaching the house on the sly, he hid in the bushes, waited until the giantess with a bucket had gone to fetch water, and only then slipped into the house imperceptibly and hid in a huge copper cauldron. Soon he heard the familiar top! - top! - top! and the ogre and his wife entered.

- Phew, Phew, Phew! the ogre shouted again, sniffing the air. “I can smell him, wife, I can smell him, he’s around here somewhere.”

“I can smell him, wife, I can smell him, he’s around here somewhere.”

– Do you really feel it, hubby? his wife answers. - Well, if this is again that tomboy who stole your gold and a chicken with golden eggs, then he is definitely sitting in the stove. And they both rushed to the stove. It's good that Jack didn't hide in it this time.

“You are always with your “fuh-fuh-fuh,” said the giantess. - Yes, it smells like that boy that you caught yesterday. I fried it for you for breakfast. How could I forget! Yes, and you are also good, you can’t distinguish the smell of living from fried!

Finally, the ogre sat down to breakfast, but every now and then he forgot about food and muttered:

– No, I still can swear that ...

And he got up and searched the pantry and cupboards, looked into all the chests, but up to the copper cauldron Luckily, it didn't get there.

Having finished breakfast, the ogre called out:

“Hey, wife, bring me my golden harp!”

The giantess brought a harp and placed it on the table in front of him.

– Sing! the giant ordered. And the golden harp played a wonderful melody. It sounded and overflowed, and under these magical sounds the ogre fell asleep and snored, so loudly that it seemed like thunder was rumbling.

Then Jack silently lifted the lid of the cauldron, got out of it as quietly as a mouse, crawled to the table, climbed on it, grabbed the golden harp and rushed with it to the door. But the harp suddenly sang loudly: “Master! Master!" The ogre immediately woke up and saw Jack running away with his harp.

Jack rushed at full speed, and the ogre rushed after him and, of course, would soon have caught him, but Jack still managed to run away and dodge and dodge all the time, quickly approaching the beanstalk. Now the cannibal is almost catching up with him, and then suddenly Jack once - and disappeared. The cannibal ran to the end of the road and sees that Jack is already far below, descending the stalk. The giant was afraid to follow him along such an unreliable "ladder", became thoughtful, and Jack, meanwhile, went down lower and lower. But then the harp rang out again: “Master! Master!" - and the giant still grabbed the stem, which staggered under his weight. Jack slides lower and lower along the stalk, and behind him the giant descends heavily. Jack is in a hurry with all his might, now it’s just a little bit left to get home.

But then the harp rang out again: “Master! Master!" - and the giant still grabbed the stem, which staggered under his weight. Jack slides lower and lower along the stalk, and behind him the giant descends heavily. Jack is in a hurry with all his might, now it’s just a little bit left to get home.

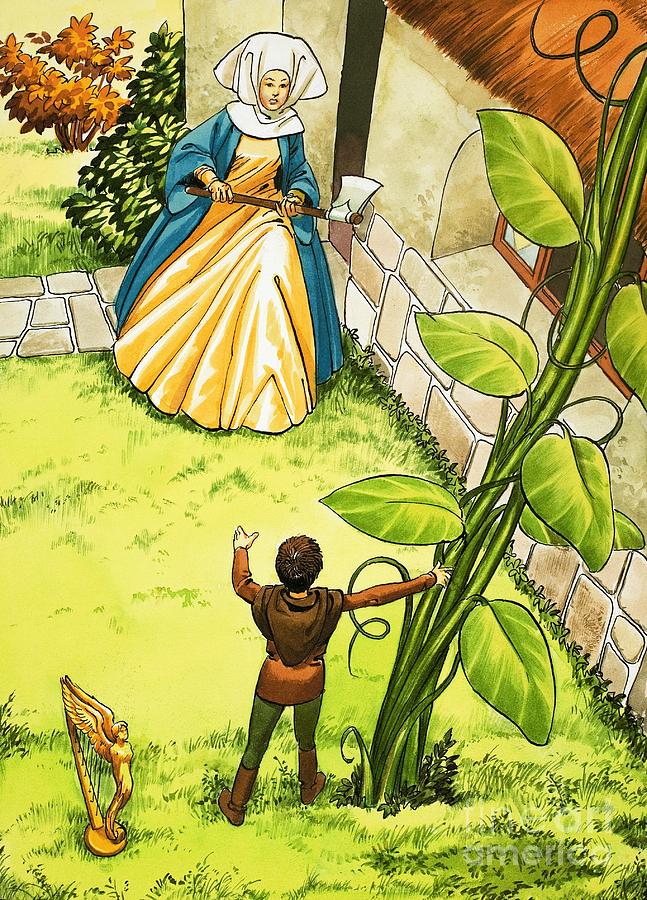

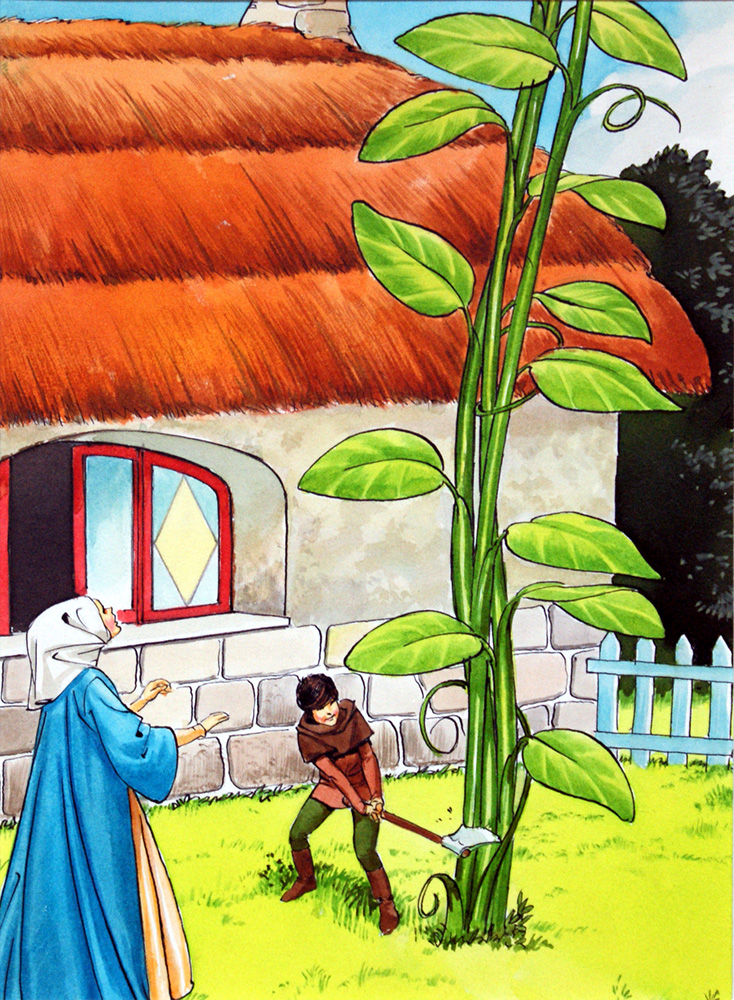

– Mom! Mother! Give me an ax! Quicker! Bring the ax! shouted Jack. His mother ran out to him with an ax, rushed to the beanstalk, and froze in horror when she saw the cannibal's huge legs dangling from under the clouds.

And Jack quickly jumped to the ground, grabbed an ax and let's cut the stem; cut it almost in two with the first blow. The ogre felt that the stem was shaking and swaying, and stopped. Looks down:

- What happened? - And Jack hit the ax again and completely cut the stem. The stalk fell to the ground, and the ogre with him, so that the spirit was out of him.

Jack first calmed his mother down and showed her the golden harp. Since then, they have fared better than before. The harp played wonderful melodies for them in the morning. And the chicken laid the golden eggs, one had only to say to her: “Lay!” Jack and his mother sold eggs, showed the harp for money, and knew no more need or sadness.

The harp played wonderful melodies for them in the morning. And the chicken laid the golden eggs, one had only to say to her: “Lay!” Jack and his mother sold eggs, showed the harp for money, and knew no more need or sadness.

Gradually they got rich, and some time later Jack went on a journey: to see people and show himself. He returned from distant countries with a beautiful princess, they got married and lived happily ever after.

Jack and the Magic Bean - frwiki.wiki

For the articles of the same name, see Jack and the Magic Bean (disambiguation).

Jack and the Beanstalk is a fairy tale popular in English.

It bears some resemblance to Jack the Giant Slayer , another Cornish hero tale. The origin of Jack and Beanstalk is unknown. We can see in the parody version which appeared in the first half of XVIII - th century the first literary version of the story. In 1807, Benjamin Tabart published in London a moralizing version closer to what is known today. Subsequently, Henry Cole popularized the story in The Home Treasury (1842) and Joseph Jacobs gave another version in English Tales (1890). The latter is the version most often reproduced in English-language collections today, and due to its lack of morality and "dry" literary treatment, it is often considered a truer oral version than Tabart's. However, there can be no certainty in this matter.

In 1807, Benjamin Tabart published in London a moralizing version closer to what is known today. Subsequently, Henry Cole popularized the story in The Home Treasury (1842) and Joseph Jacobs gave another version in English Tales (1890). The latter is the version most often reproduced in English-language collections today, and due to its lack of morality and "dry" literary treatment, it is often considered a truer oral version than Tabart's. However, there can be no certainty in this matter.

Jack and the Beanstalk is one of the most famous folk tales and has been the subject of many adaptations in various forms until today.

Summary

- 1 First printed versions

- 2 Summary (Jacobs version)

- 3 variants

- 4 Structure

- 5 Classification

- 6 Fee-fi-fo-fum formula

- 7 parallels in other fairy tales

- 8 Patterns and ancient origin of these

- 9 Morality

- 10 interpretations

- 11 Illustrations

- 12 Modern adaptations

- 12.

1 Cinema

1 Cinema - 12.2 Television and video

- 12.3 Video games

- 12.4 Exhibitions

- 12.

- 13 Notes and references

- 14 Bibliography

- 14.1 Versions / editions of fairy tale

- 14.2 Research

- 14.3 Symbolic

- 14.4 About adaptation

- 15 See also

- 15.1 Related Articles

First printed versions

The origin of this tale is not exactly known, but it is believed to have British roots.

According to Iona and Peter Opie, the first literary version of the tale is The Charm Shown in the History of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean , which appears in the 1734 English edition of Round of Our Charcoal Fire or Christmas Amusement , a collection that includes the First Edition, which did not include the tale, is dated 1730. Then this is a parody version that makes fun of the fairy tale, but nevertheless testifies on the part of the author of a good knowledge of the traditional fairy tale.

Frontispiece (" Jack Fleeing the Giant ") and title page "The Story of Jack and the Beanstalk" , B. Tabart, London, 1807 when two books were published: "The Story of Mother Twaddle" and "The Wonderful Achievements of Her Son Jack" with the single initials " Bat " as the author's name. and Jack and Bob's Story , published in London by Benjamin Tabart. In the first case, this is a poetic version, which differs significantly from the known version: a servant takes Jack to the giant's house, and she gives the latter beer to put him to sleep; as soon as the giant falls asleep, Jack decapitates him; He then marries a maid and sends for his mother. Another version, whose title page states that it is a version "printed from an original manuscript, never before published", is closer to the tale as we know it today, except that it has a fairy character, which gives the moral of the story.

In 1890, Joseph Jacobs reported in English Tales a version of Jack and the Beanstalk which he said was based on "oral versions heard in his boyhood in Australia about 1860" and in which he took the side of "ignoring excuse". given by Tabart for Jack who killed the giant. Subsequently, other versions of the tale will follow sometimes Tabart, who therefore justifies the hero's actions, sometimes Jacobs, who presents Jack as a steadfast deceiver. So Andrew Lang at The Red Fairy Book , also published in 1890, follows Tabart. From Tabart/Lang or Jacobs, it is difficult to determine which of the two versions is closer to the oral version: while specialists such as Katherine Briggs, Philip Neal or Maria Tatar prefer Jacobs' version, others such as Jonah and Peter Opie consider it should be “nothing but a reworking of a text that has continued to be printed for more than half a century. "

given by Tabart for Jack who killed the giant. Subsequently, other versions of the tale will follow sometimes Tabart, who therefore justifies the hero's actions, sometimes Jacobs, who presents Jack as a steadfast deceiver. So Andrew Lang at The Red Fairy Book , also published in 1890, follows Tabart. From Tabart/Lang or Jacobs, it is difficult to determine which of the two versions is closer to the oral version: while specialists such as Katherine Briggs, Philip Neal or Maria Tatar prefer Jacobs' version, others such as Jonah and Peter Opie consider it should be “nothing but a reworking of a text that has continued to be printed for more than half a century. "

Jack trades his cow for beans. Illustration by Walter Crane.

Summary (Jacobs version)

In Jacobs' version of the tale, Jack is a boy who lives alone with his widowed mother. Their only source of existence is milk from a single cow. One morning they realize that their cow is no longer producing milk. Jack's mother decides to send her son to sell her in the market.

Jack's mother decides to send her son to sell her in the market.

Along the way, Jack meets a strange looking old man who greets Jack by his first name. He manages to convince Jack to trade his cow for beans, he says "magic": if we plant them at night, in the morning they will grow to heaven! When Jack returns home with no money but only a handful of beans, his mother gets angry and throws the beans out the window. She punishes her son for his gullibility by sending him to bed without supper.

« Fee-foo-foom, I can smell the blood of an Englishman. ". Arthur Rackham's illustration from English Tales by Flora Annie Steele, 1918.

While Jack sleeps, the beans sprout from the ground, and by morning a giant stalk of beans has grown in the place where they were thrown. , Jack sees a huge rod rising into the sky and decides to immediately climb to its top.

At the top he finds a broad road which he chooses and which leads him to a large house. On the threshold of a large house stands a large woman. Jack asks her to offer him dinner, but the woman warns him: her husband is a cannibal, and if Jack doesn't turn around, he risks serving dinner to her husband. Jack insists, and the giantess cooks a meal for him. Jack is not halfway to the meal when footsteps are heard, causing the whole house to shake. The giantess hides Jack in the oven. The ogre appears and immediately senses the presence of a human:

On the threshold of a large house stands a large woman. Jack asks her to offer him dinner, but the woman warns him: her husband is a cannibal, and if Jack doesn't turn around, he risks serving dinner to her husband. Jack insists, and the giantess cooks a meal for him. Jack is not halfway to the meal when footsteps are heard, causing the whole house to shake. The giantess hides Jack in the oven. The ogre appears and immediately senses the presence of a human:

« F-f-f-f-fum!

I smell the blood of an Englishman,

whether he is alive or dead,

I will have his bones to grind my bread. "

What does it mean:

« F-f-f-fum!

I sniff the blood of an Englishman,

Dead or alive,

I have to grind his bones to make bread. "

The ogre's wife tells him that he has his own thoughts and that the smell he smells is probably the smell of the remains of a little boy that he enjoyed the day before. The ogre leaves, and as Jack is ready to jump out of his hiding place and wrap his legs around his neck, the giantess tells him to wait until her husband naps. After the ogre swallows, Jack sees him take some bags from the chest and count the gold coins in them until he falls asleep. So Jack tiptoes out of the oven and runs off carrying one of the bags of gold. He descends the bean stalk and brings gold to his mother.

The ogre leaves, and as Jack is ready to jump out of his hiding place and wrap his legs around his neck, the giantess tells him to wait until her husband naps. After the ogre swallows, Jack sees him take some bags from the chest and count the gold coins in them until he falls asleep. So Jack tiptoes out of the oven and runs off carrying one of the bags of gold. He descends the bean stalk and brings gold to his mother.

Jack escapes for the third time, carrying a magical harp. The ogre is on his trail. Illustration by Walter Crane.

Gold allows Jack and his mother to live for a while, but there comes a time when it all disappears and Jack decides to return to the top of the bean stalk. On the threshold of a large house, he again finds the giantess. She asks him if he had already arrived the day her husband noticed one of her bags of gold was missing. Jack tells her that he is hungry and cannot talk to her until he has eaten. The giantess prepares food for him again . .. Everything goes like last time, but this time Jack manages to steal a goose that every time we say "ponds" lays a golden egg. He returns her to his mother.

.. Everything goes like last time, but this time Jack manages to steal a goose that every time we say "ponds" lays a golden egg. He returns her to his mother.

Soon an unsatisfied Jack feels the urge to climb back to the top of the bean stalk. So the third time he climbs up the stick, but instead of going straight to the big house, when he comes to it, he hides behind a bush and waits before entering the house. Ogre, that giantess went out for water. There is another cache in the house, in a "pot". A couple of giants are back. Once again, the ogre senses Jack's presence. The giantess then tells her husband to look in the oven because that's where Jack used to hide. Jack is gone and they think it is the smell of the woman the ogre ate the day before. After dinner, the ogre asks his wife to bring him a golden harp. The harp sings until the ogre falls asleep, and Jack takes the opportunity to get out of his hiding place. When Jack grabs the harp, she calls her master an ogre with a human voice, and the ogre wakes up. The ogre chases Jack, who has grabbed the harp, towards the beanstalk. The ogre comes down the rod behind Jack, but as soon as Jack goes down, he quickly asks his mother to give him an ax with which he cuts the huge rod. The ogre falls and "breaks his crown".

The ogre chases Jack, who has grabbed the harp, towards the beanstalk. The ogre comes down the rod behind Jack, but as soon as Jack goes down, he quickly asks his mother to give him an ax with which he cuts the huge rod. The ogre falls and "breaks his crown".

Jack shows his mother a golden harp, and thanks to her and the sale of golden eggs, they both become very rich. Jack marries a great princess. And then they live happily ever after?

Variants

Three flights are missing from the 1734 parody version and the 1807 "BAT" version, but not from the bean stalk. In Tabart's version (1807), Jack, upon arriving in the giant's realm, learns from an old woman that his father's property had been stolen by the giant.

Composition

- Introduction: Jack and his mother are poor, but their cow gives milk.

- Misfortune → Mission: The cow no longer gives milk

- Encounter → Magic Offer ← Earth Mission Failure: Jack meets a "wizard" - Jack accepts magic and trades a cow for one or more beans.

- Earth Sanction: Jack is punished, deprived of food (Jack is hungry). NIGHT: Jack sleeps.

- The magic happens: a stalk of a giant bean is found in the morning.

- Skyworld:

- 1- e visit / 1- flight (Jack is very hungry): (a) Man-eating Jack's wife protects and hides in the oven - (b) Ogre senses Jack: Phi-Pho- fum! ("Chorus formula") - (c) Jack takes the bag of gold - (d) Ogre is unaware.

- 2- e visiting / 2- e stealing (Jack is hungry): (a) The ogre's wife doubts Jack and hides him in spite of everything in the oven - (b) Fi-fi-fo-foom! - (c) Jack takes the goose that lays the golden eggs - (d) Ogre in his house almost catches up with Jack.

- 3 - th visit / 3 e flight (Jack wants to find other treasures): (a) Jack is hiding in a pot - (b) Fee-fo-fum! - (a ') Ogre's wife condemns Jack - (c) Jack takes golden harp - (d) Ogre pursues Jack to wand.

- Conclusion: Fall and death of the ogre - Jack and his mother are rich and happy.

This plan includes several progressions, each of which takes place in three stages: in the earthly world, hunger becomes more acute (cash cow → beans → "going to bed without supper"), and in the heavenly world, hunger subsides until finally turns into a desire for more wealth, the ogre's wife gradually separates from Jack, and finally the danger posed by the ogre becomes more and more concrete.

Classification

Ogre fall. Illustration by Walter Crane.

Illustration by Walter Crane.

The tale is usually kept in Aarne-Thompson tales AT 328, corresponding to the type "The boy who steals the ogre's treasure". However, one of the main elements of the tale, namely the bean stalk, does not occur in other tales in this category. Beanstalk , similar to the one that appears in Jack and the Beanstalk , is found in other typical tales such as AT 563, "Three Magic Objects" and AT 555, "The Fisherman and His Wife". Bean Ogre's fall, on the other hand, seems to be unique to Jack .

Formula "Fi-fi-fo-fum"

The formula appears in some versions of Jack's story The Giant Killer ( XVIII - th th century), and earlier, in Shakespeare's play King Lear (v.1605). We find echoes of this in the Russian fairy tale about Vasilisa the Most Beautiful , where the witch shouts: “Crazy! It smells like Russian here! (Crazy, Fu means "Phi! Pah!" In Russian).

Parallels in other tales

Among other similar tales, such as AT 328 "The Boy Stealing the Ogre's Treasure", we find in particular the Italian tale "The Thirteenth" and the Greek tale How the Dragon was Deceived . Corvetto , a tale that appeared in Giambattista Basile's Pentamerone (1634–1636), is also part of this type. It is about a young courtier who enjoys the favor of the king (of Scotland) and is the envy of the other courtiers, who therefore look for a way to get rid of him. Not far from there, in a fortified castle perched atop a mountain, lives an ogre, who is served by an army of animals and who keeps certain treasures that the king is likely to desire. The enemies of Corvetto force the king to send a young man in search of a cannibal, first a talking horse, then a tapestry. When a young man enters two victorious cases of his mission, they see to it that the king orders him to capture the ogre's castle. To complete this third mission, Corvetto introduces himself to the ogre's wife, who is busy preparing a feast; he offers to help her in her task, but instead kills her with an axe. Corvetto then manages to knock the ogre and all the guests of the feast into a hole dug in front of the castle gates. As a reward, the king finally extends the hand of his daughter to the young hero.

Corvetto then manages to knock the ogre and all the guests of the feast into a hole dug in front of the castle gates. As a reward, the king finally extends the hand of his daughter to the young hero.

The Brothers Grimm note the analogies between Jack and the Beanstalk and the German fairy tale The Devil's Three Golden Hairs (KGM 29), in which the devil's mother or grandmother acts in a manner quite comparable to the behavior of the cannibal's wives in Jack : a female figure, protecting the child from an evil male figure. In the version of the tale "Petit Puse" (1697), Perrault's wife also comes to the aid of Puse and his brothers.

The theme of a giant plant serving as a magical staircase between the earthly world and the heavenly world is also found in other fairy tales, especially in Russian ones, for example, in "Doctor Fox" .

The tale is unusual in that in some versions the hero, although an adult, does not marry at the end, but returns to his mother. This feature occurs only in a small number of other tales, such as some variations of the Russian tale Vasilisa the Beautiful .

This feature occurs only in a small number of other tales, such as some variations of the Russian tale Vasilisa the Beautiful .

Patterns and ancient origins of these

The bean stalk seems to be a memory of the World Tree connecting Earth with Heaven, an ancient belief that existed in Northern Europe. This may be reminiscent of a Celtic tale, an ancient form of the Axis mundi , the original myth of the cosmic tree, a magical-religious symbolic link between Earth and Heaven, allowing sages to climb to the upper halves to know the secrets of the cosmos and the conditions of human life on earth. It is also reminiscent in the Old Testament of the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11:1-9) and the scale of Jacob's dream (Genesis 28:11-19) ascending to Heaven.

The victory of the "small" over the "great" is reminiscent of the episode of David's victory over the giant Philistine Goliath in the Old Testament ( First Samuel 17:1-58). In the 1807 version of The Bat (1807), the "ogre" is beheaded, as was Goliath in the Old Testament story.

"The Goose that Lays the Golden Eggs", illustration for the Aesop fable by Milo Winter, taken from of the book "Isop for Children" . The motif of the "hen that lays golden eggs" is repeated in the fairy tale Jack and the Magic Bean .

Jack steals a goose that lays golden eggs, which resembles the goose with golden eggs of Aesop's fable (VII e - VI - th BC), without coming to however this is Aesopian morality: no moral judgment is made on greed in Jack . Gold mining animals can be found in other tales such as the donkey in Peau d'âne or the donkey in Petite-table-sois-mise, Donkey-to-gold and Gourdin-sors-du. - bag , but a fact. The fact that in Jack the goose lays golden eggs does not play a special role in the development of the plot. In his Symbol Dictionary Jean Chevalier and Alain Gerbran note: “In the Celtic continental and insular tradition, the goose is the equivalent of the swan [. ..]. Considered a messenger from the Other World, among the Bretons he is the object of a ban on food, along with a hare and a chicken. "

..]. Considered a messenger from the Other World, among the Bretons he is the object of a ban on food, along with a hare and a chicken. "

Jack also steals the golden harp. In the same Dictionary of Symbols we can read that the harp “connects heaven and earth. The heroes of the Edda want to be burned with a harp on a funeral pyre: this will lead them to that world. This is the role of the psychiatrist, the harp does not fulfill it only after death; during earthly life, it symbolizes the tension between the material instincts, represented by its wooden frame and the ropes of the lynx, and the spiritual aspirations, represented by the vibrations of these ropes. They are harmonious only if they come from a well-regulated tension between all the energies of the being, this measured dynamism that symbolizes the balance of personality and self-control. "

Moral

The story shows a hero who shamelessly hides in a man's house and uses his wife's sympathy to rob him and then kill him. In Tabart's moralized version, the fairy explains to Jack that a giant stole and killed his father, and Jack's actions turn into justified retribution in the process.

In Tabart's moralized version, the fairy explains to Jack that a giant stole and killed his father, and Jack's actions turn into justified retribution in the process.

Meanwhile, Jacobs omits this excuse, relying on the fact that, according to his own recollection of a fairy tale heard in childhood, she was absent from it, and also on the idea that children know well, without this we should tell them in a fairy tale that theft and murder are "evil".

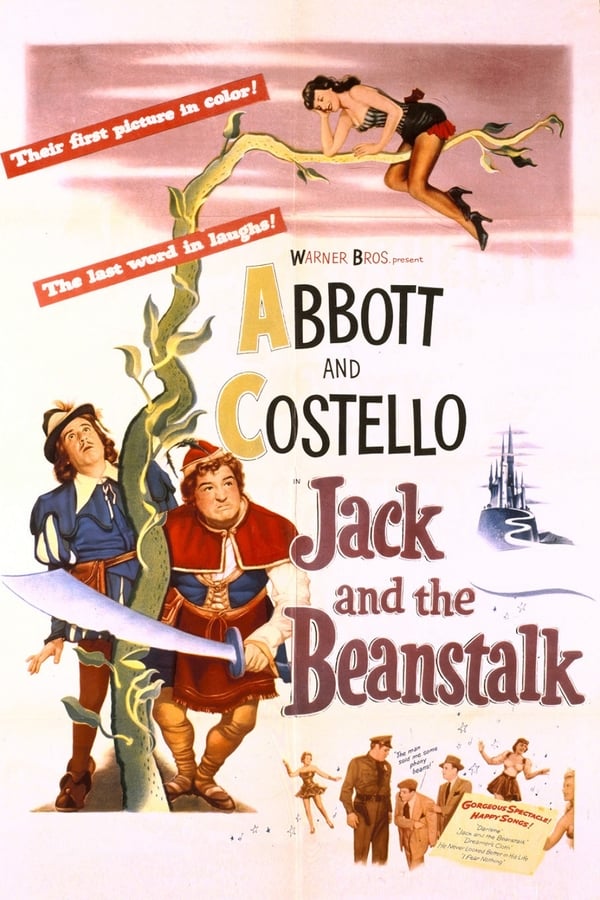

Many modern interpretations have followed Tabart and portrayed the giant as a villain, terrorizing little people and often stealing valuables to make Jack's behavior legal. For example, the film The Goose Who Loves Golden Eggs ( Jack and the Beanstalk , 1952), starring Abbott and Costello, blames Jack the giant for failure and poverty, making him guilty of theft, and little people from the lands at the foot of his dwelling, food, and possessions, including a goose that lays golden eggs, which in this version originally belonged to Jack's family. Other versions suggest that the giant stole the chicken and harp from Jack's father.

Other versions suggest that the giant stole the chicken and harp from Jack's father.

However, the moral of the tale is sometimes disputed. It is, for example, a subject of discussion in Richard Brooks' Seed of Violence ( Jungle on Plank , 1955), an adaptation of the novel by Evan Hunter (i.e. Ed McBain).

A mini-series made for television by Brian Henson in 2001, Jack and the Beanstalk ( Jack and the Beanstalk: The True Story ) gives an alternate version of the tale, leaving Tabart's additions aside. Here, Jack's character is significantly clouded, and Henson dislikes the morally dubious actions of the hero in the original tale.

Interpretations

There are different interpretations of this tale.

At first we can read Jack's exploits in the Middle Kingdom as a fairy tale. Indeed, it is at night when Jack, deprived of his supper, is asleep that a giant bean stalk appears, and it is not uncommon to see it as a fairy tale creation, spawned by his hunger and subsequent adventures, in part because of the guilt of failing him. missions. The giantess, the ogre's wife, is a projection of Jack's mother in the dream, which can be interpreted as the fact that during Jack's first visit to the Skyworld, the giantess accepts her regarding her mother's protective behavior. The ogre thus represents the absent father, whose role was to provide both, Jack and his mother, with a livelihood, a role for which Jack is now called upon to replace him. In Skyworld, Jack joins his father-turned-giant and formidable shadow - the ogre - in competition with him, who seeks to eat him, and eventually sets about the task. Causing the ogre's death, he comes to terms with his father's death and realizes that it is his duty to the one who was initially presented as worthless to take over. In this way, he also breaks the bonds that bind and hold his mother captive to his father's memory.

missions. The giantess, the ogre's wife, is a projection of Jack's mother in the dream, which can be interpreted as the fact that during Jack's first visit to the Skyworld, the giantess accepts her regarding her mother's protective behavior. The ogre thus represents the absent father, whose role was to provide both, Jack and his mother, with a livelihood, a role for which Jack is now called upon to replace him. In Skyworld, Jack joins his father-turned-giant and formidable shadow - the ogre - in competition with him, who seeks to eat him, and eventually sets about the task. Causing the ogre's death, he comes to terms with his father's death and realizes that it is his duty to the one who was initially presented as worthless to take over. In this way, he also breaks the bonds that bind and hold his mother captive to his father's memory.

We can also interpret the story from a broader point of view. The giant that Jack kills before becoming the master of his fortune may represent the "big ones in this world" who exploit the "little people" and thereby provoke their rebellion, making Jack the hero of a sort of jacquerie.

Vector illustrations

The tale, reprinted many times, was drawn by famous artists such as George Cruikshank (illustrator of Charles Dickens), Walter Crane or Arthur Rackham.

Modern fixtures

Movie

Jack and beanstalk (1917)

- 1902: Jack and the Beanstalk , a ten-minute short film produced by the Edison Manufacturing Company and directed by George S. Fleming and Edwin S. Porter, with Thomas White (Jack).

- 1912: Jack and the Beanstalk or Jack the Giant Killer , a short film directed by J. Searle Dawley, with Gladys Hewlett (Jack), Harry Eitinge (giant) and Gertrude McCoy.

- Jack and the Beanstalk , a short film with Leland Benham (Jack) and Helen Badgley.

- 1917: Jack and the Beanstalk , directed by Chester M. Franklin and Sidney Franklin, with Francis Carpenter (Jack), Jim J. Traver (giant), Virginia Lee Corbin, Jane Leigh, Katherine Leigh, Violet Radcliffe and Carmen de Ryu.

- 1922: Jack and the Beanstalk , produced and directed by Walt Disney.

- 1924: Jack and the Beanstalk , an animated short film directed by Herbert M. Dawley.

- 1924: Jack and the Beanstalk , short film directed by Alfred J. Goulding, with Baby Peggy and Blanche Payson.

- 1924: L'Ogre ( The Giant Killer ), short film mixing live action footage and animation, directed by Walter Lantz, starring the character Dinky Doodle (a character created in 1916 and considered one of the first cartoon characters) .

- 1931: Jack and the Beanstalk , an animated short film directed by Dave Fleischer, starring Betty Boop.

- 1933: Mickey in Giantland ( Giantland ), an animated short produced by Walt Disney and directed by Barton Gillette, starring, as the name suggests, the character Mickey.

- 1933: Jack and the Beanstalk , an animated short film directed by Ub Iwerks and written by Ben Hardaway, collaboration with Sheamus Culhane, music by Carl W.

Stalling (uncredited).

Stalling (uncredited). - 1943: Jack the Wabbit and the Beanstalk , an animated short film directed by Friz Freleng, music by Carl W. Stalling and starring the character Bugs Bunny.

- 1947: Mickey and the Beanstalk , episode from Disney's Spring Scoundrel , directed by Hamilton Luske and Bill Roberts, again starring the character Mickey.

- 1952: La Poule aux Eggs d'Or ( Jack and the Beanstalk ), produced in black and white for the modern part and in color for Jean Yarbrough's fantasy tale period with Lou Costello (Jack), Buddy Baer (giant), and Costello's lifelong friend, Bud Abbott.

- 1955: Jack and the Beanstalk or Jack the Giant Killer , a British short film (China Shadow technique) directed by Lotte Reiniger with music by Freddie Phillips.

- 1955: Seed of Violence by Richard Brooks, who integrates the cartoon Jack and the Magic Bean into his film to show Richard Dadier's character's heart for tolerance towards his students.

- 1967: Shônen Jakku to Mahô-tsukai (in the United States: Jack and the Witch ) is a Japanese animated film directed by Taiji Yabusita.

- 1970: Jack and the Beanstalk , directed by Barry Mahon, with Mitch Poulos (Jack) and Renato Boraquerro (giant).

- 1974: Jack and the Beanstalk is a Japanese-American animated film directed by Gisaburo Sugi.

- 2013: Jack the Giant Slayer ( Jack the Giant Slayer ), a feature film directed by Bryan Singer, starring Nicholas Hoult as Jack.

- 2015: Into the Woods musical film featuring characters from fairy tales with Daniel Huttlestone as Jack.

- Tom and Jerry Jack and Magic Bean

TV and video

- 1967: Jack and the Beanstalk ( Jack and the Beanstalk (1967) ), produced by Gene Kelly, William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, directed by Gene Kelly, Music by Lenny Hayton, with Gene Kelly, Bobby Riha (Jack) and Ted Cassidy (giant).

The film, which is about fifty minutes long, combines real footage and animation, emphasizing music and dance.

The film, which is about fifty minutes long, combines real footage and animation, emphasizing music and dance. - 1973: The Goodies and Beanstalk , episode of the British TV series featuring the Goodies, a trio of actors consisting of Tim Brooke-Taylor, Graham Garden and Bill Oddie.

- 1974: Jack and the Beanstalk with Peter Jeffrey.

- 1993: Jack and the Magic Bean (video), animated short film directed by Koji Morimoto, "Anime Art Video" compilation.

- 1998: Jack and the Beanstalk , British television film directed by John Henderson and starring Neil Morrissey (Jack), Griff Rhys Jones and Peter Serafinowicz.

- 2001: Jack and the Beanstalk ( Jack and the Beanstalk: The True Story of ), directed by Brian Henson, with Matthew Modine (Jack), Vanessa Redgrave, Mia Sarah, Daryl Hannah, Jon Voight and JJ Feild (Jack's child) .

- 2010: Jack and the Beanstalk , an American television film directed by Gary J.

Tunnicliff and starring Colin Ford, Chloe Moretz and Christopher Lloyd.

Tunnicliff and starring Colin Ford, Chloe Moretz and Christopher Lloyd. - 2010: Simsala Grimm , German cartoon season 2 episode 1: Jack and the beanstalk (Hans und die Bohnenranke)

- 2013: TV series Once Upon a Time offers its own version of the tale. "Jack" here is a woman, and her real name is Jacqueline. In the universe of the series, Jacqueline allies with Prince James (charming's twin) and manipulates the giant into pretending to be his friends, rather than steal his wealth and magic beans;

- 2013: Tom and Jerry: Giant Beans , an animated television series that features Tom and Jerry.

video games

- Attempt to adapt to Nintendo has been cancelled.

- There is an Amstrad CPC version.

- There is also a Commodore 64 version called Jack and the Beanstalk (© 1984, Thor Computer Software).

- In 2008, 24 Grimm stories were adapted into 24 episodes of a downloadable video game called American McGee's Grimm, created by American creator American McGee, also known for the game American McGee's Alice .

In a review of children's books for The Quarterly Review of 1842 and 1844 (volumes 71 and 74), Elizabeth Eastlake recommends a series of books beginning with Treasury Houses [sic] by Felix Summerlee [i.e. Henry Cole], including a book of England's traditional Children's Songs , Beauty and the Beast , Jack and the Beanstalk and other old friends, all charmingly performed and beautifully illustrated." - quoted by Summerfield (1980), pp. 35-52.

In a review of children's books for The Quarterly Review of 1842 and 1844 (volumes 71 and 74), Elizabeth Eastlake recommends a series of books beginning with Treasury Houses [sic] by Felix Summerlee [i.e. Henry Cole], including a book of England's traditional Children's Songs , Beauty and the Beast , Jack and the Beanstalk and other old friends, all charmingly performed and beautifully illustrated." - quoted by Summerfield (1980), pp. 35-52. - ↑ a b c and d (en) "The Story of Jack and the Beanstalk ", available from surlalunefairytales.com. — Page consulted June 12, 2010

- ↑ a and b Tatar (2002), p. 132.

- ↑ a and b Opie (1974).

- ↑ (in) The Story of Jack and the Beanstalk: A Recording and Facsimile, about the Hockliff Project.

Tale collected by Johann Georg von Hahn in Griechische und Albanesische Märchen , 1854

Tale collected by Johann Georg von Hahn in Griechische und Albanesische Märchen , 1854 - ↑ (in) Corvetto at surlalune.com, English translation of the tale.

- ↑ (en) Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm (eds.), The Devil's Three Golden Hairs, in Selected Stories of the Brothers Grimm , trad. Frédéric Baudry, Hachette, Paris, 1900, p. 146 St. - Online at the Gallica website.

- ↑ (ru) William Ralston Shedden (ed.), "The Fox Doctor" in fairy tales popular in Russia , trans. Loys Brueyre, Hachette, Paris, 1874, p. 277 St. - Online at the Gallica website.

- ↑ (en) William Shedden Ralston (ed.

), "Vasilisa la Belle", in Popular Tales of Russia , trans. Loys Brueyre, Hachette, Paris, 1874, p. 147 St. - Online at the Gallica website.

), "Vasilisa la Belle", in Popular Tales of Russia , trans. Loys Brueyre, Hachette, Paris, 1874, p. 147 St. - Online at the Gallica website. - ↑ Tatarsky (1992), p. 199.

- ↑ Eliade (1952). 9Chevalier-Gheerbrant (1992), p. 392.

- ↑ Tatarsky (1992), p. 198.

- ↑ Nazzaro (2002), pp. 56-59.

- ↑ Cruikshank (1854).

- ↑ Crane (1875).

- ↑ Rackham (1913).

- ↑ (in) Jack and the Beanstalk , sealntera.com.

- ↑ a b and c Available in addition to DVD, Jack's Giant Fighter , MGM Home Entertainment - Ciné Malta, coll. "Cult & Underground", 2002. EAN 3-545020-008485.

- ↑ a and b Find out more.

- ↑ Title assigned to by Drive In Movie when announcing the broadcast of this movie on August 10, 2018 at 9:00 pm.

However, this title does not appear in the subtitles of the film produced by Bach Films.

However, this title does not appear in the subtitles of the film produced by Bach Films. - ↑ Process Super Color, mentioned in the credits.

- ↑ (in) Jack and the Beanstalk at Movie Database at Internet

- ↑ Downloadable version from catsuka.com.

- ↑ " TREMOLO EDITIONS PRODUCTIONS " on TREMOLO EDITIONS PRODUCTIONS (accessed March 22, 2016)

- ↑ " FGL Music - Jack and the Magic Bean - Tale Musical Pop Rock (Jack and the Magic Bean) ", available at www.fglmusic.com (accessed March 22, 2016)

- (en) [Crane] Jack and the Beanstalk , George Routledge & Sons, London, 1875.

Jack and the Beanstalk, in Bluebeard picture book , Walter Crane, ill., George Routledge & Sons , London, [ca. 1875]. - Send online text messages with a fax at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) website.

Jack and the Beanstalk, in Bluebeard picture book , Walter Crane, ill., George Routledge & Sons , London, [ca. 1875]. - Send online text messages with a fax at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) website. - (en) George Cruikshank (ed., ill.), "The Story of Jack and the Beanstalk", in Fairy Library , David Bog, London, [c.1853-1854]. — Notice and facsimile of mutilated copy at The Hockliffe Project website.

- (en) [Heartland] "Jack and the Beanstalk", in Edwin Sidney Heartland (ed.), English Tales and Other Folk Tales , Walter Scott Publishing Company, London, [c.1890]. - Send text messages online at surlalune.com.

- (en) [Jacobs] "Jack and the Beanstalk", Joseph Jacobs (ed.

), English Tales , David Nutt, London, 1890. - Text online at surlalune.com.

), English Tales , David Nutt, London, 1890. - Text online at surlalune.com. - (en) [Lang] "Jack and the Beanstalk", in Andrew Lang (ed.), The Red Fairy Book , Longmans, Green and Company, London, 1890. - Text online at surlalune.com.

- (en) [McLaughlin] Jack and the Beanstalk, R. Andre (?) ill., McLaughlin Brothers, Sat. "Young Men Series", New York, 1888.

- (en) [Nesbit] "Jack and the Beanstalk", in E. Nesbit, "Old Children's Stories" , ill. W. H. Margetson, Henry Froude and Hodder and Stoughton, Sat. "Children's Bookcase", London 1908. - Text online with facsimile at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) website.

- (en) [Orr] "Jack and the Beanstalk", in "The Stories of Jack and the Beanstalk [ and Michael Scott ]", Francis Orr & Sons, Glasgow, [1820]. - Send online text messages with a fax at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) website.

- (en) [Park] The Amazing Story of Jack and the Beanstalk, which details his travels through the beanstalk, how he got hold of the sacks of gold, and how he killed the ogre by chopping down the bean. stem , A. Park, London, [c.1840]. - Notice and facsimile on the Hockliffe Project website.

- (en) [Parsons] "Jack and the Beanstalk", in Elsie Clews Parsons (ed.

), "Tales from Maryland and Pennsylvania", in Journal of American Folklore , vol. 30, n o 116 (April ). - Send text messages online at surlalune.com.

), "Tales from Maryland and Pennsylvania", in Journal of American Folklore , vol. 30, n o 116 (April ). - Send text messages online at surlalune.com. - (en) Arthur Rackham , Arthur Rackham Picture Book , W. Heinemann, London, 1913.

- (en) [Reynolds] "Jack and the Beanstalk: A New Version", in Jack and the Beanstalk, and Little Jane and Her Mother , William J. Reynolds & Co., Boston, 1848]. - Send online text messages with a fax at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) website.

- (en) [Tabart] The Story of Jack and the Beanstalk , Benjamin Tabart - Juvenile and School Library, London 1807 - Notice and facsimile on The Hockliffe Project website.

- (en) [Vredenberg] "Jack and the Beanstalk", in Edric Vredenberg et al. (ed.), Old Tales , Francis Brundage, E. J. Andrews et al. ill., Raphael Tuck & Sons, London, [before 1919]. - Send online text messages with a fax at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) website.

- (en) Christine Goldberg, "Composition Jack and the Beanstalk ", at Marvels & Tales , vol. 15, No 1 (2001), pp. 11-26. - Online at the Project Muse website.

- (en) Matthew Orville Granby, "Tame Fairies Are Good Teachers: The Popularity of Early British Fairy Tales", in The Lion and the Unicorn , 30.

1 ().

1 (). - (en) Jonah and Peter Opie, Classic Tales , New York, Oxford University Press, New York, 1974.

- ( fr ) Geoffrey Summerfield, "Creating a Home Treasury", at children's literature , 8 (1980).

- (en) Maria Tatar, Classic Fairy Tales Annotated , W. W. Norton, 2002 (ISBN 0-393-05163-3) .

- (ru) Maria Tatarka, cut off their heads! : Tales and Culture of Childhood , Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1992 (ISBN 0-691-06943-3) .

Learn more