Kid teaching math

What Do We Really Know About Teaching Kids Math?

Earlier this week, I wrote about the history of progressive math education, the culture wars it has inspired over the past hundred years, and the controversy over the California Math Framework. Today, I want to start with a much broader question: What do we really know about how to teach math to children?

The answer is not all that much—and what little we do know is highly contested. An American math education usually proceeds in a linear fashion, with the idea that one subject prepares you for the next. Take, for example, the typical path through mathematics for a relatively advanced student. They will start with basic arithmetic, learn multiplication and division, and graduate to fractions. Then they’ll go into algebra, then geometry, then Algebra II/trigonometry, before tackling calculus. There may be small variations to this sequence, but that’s more or less how most kids learn math in the U.S.

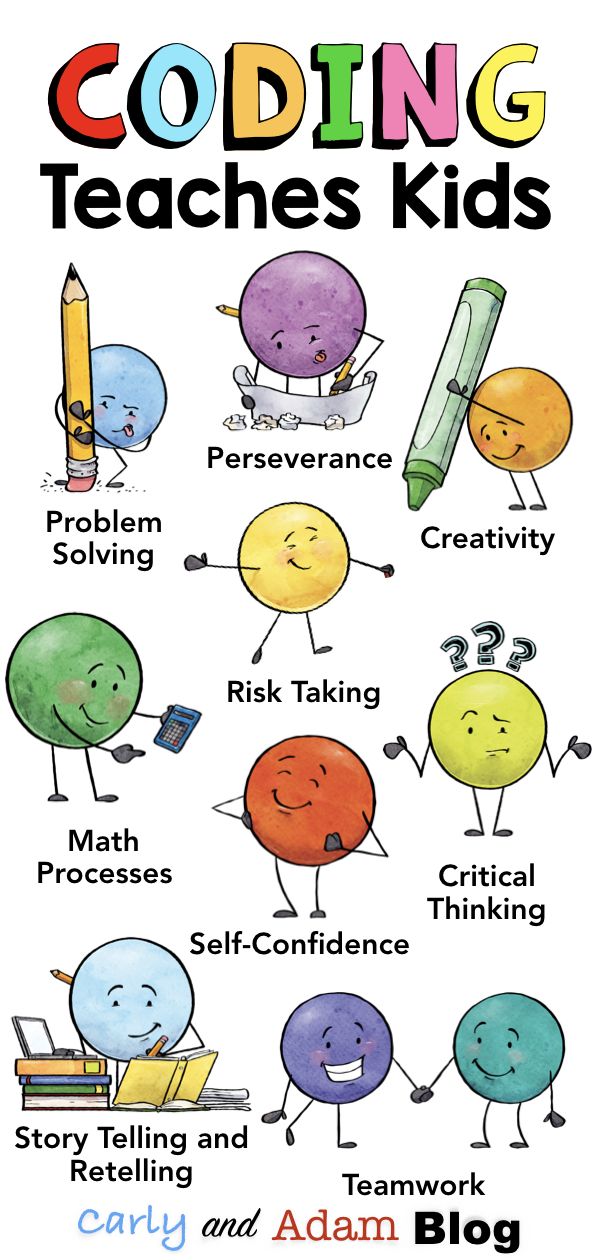

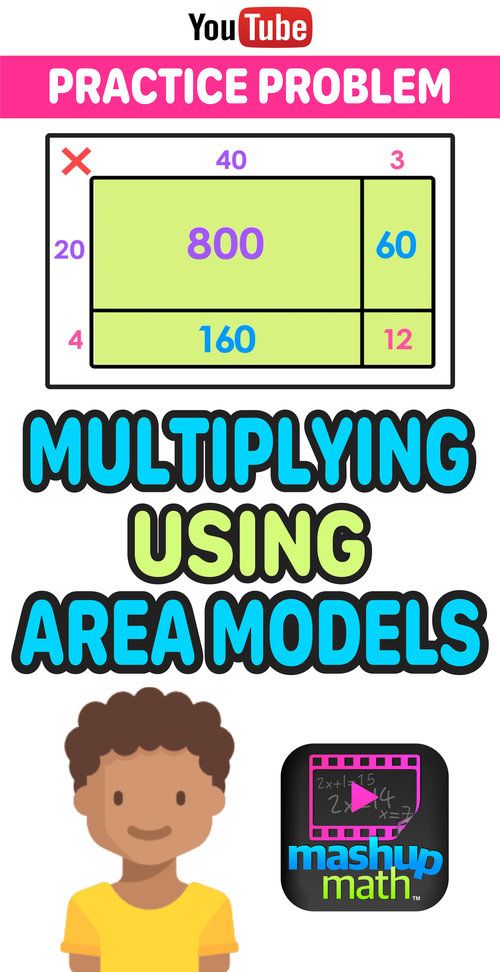

But are we sure that these math subjects should really go in this order? And are we sure that these are the only steps that should be included? There are arguments, for example, that say that children should engage in play-based exploration of concepts of calculus in preschool and kindergarten before they start learning to add and subtract, because proper guidance through pattern-recognition activities like Legos and origami will place arithmetic into the correct context and make it feel less tedious.

A much less radical example can be found at a school district in Escondido, California, that recently altered the traditional math procession by placing all its freshmen and sophomores in “Math I” and then “Math II.” When they reach their junior year, those students go through a “decision tree” where they answer questions like “Do you know what type of career you want to have?” and “Is your career in a STEM field?” Students who answer yes, and say they want to ultimately take calculus, are put in a math class that includes precalculus; if not, they are placed in statistics-based courses. The idea is to make math education better for all students, even those who might not want to pursue careers in STEM, though some in the district have also acknowledged concerns that the system might reinforce inequality, with the statistics track being considered the “pathway for students of color.”

The Escondido experiment highlights a lot of the more entrenched questions in math education. Does kicking an equity issue down the road really solve it? How should we address disparate outcomes in achievement while also accepting that most students won’t go on to do college-level math? And why is there an assumption that statistics, with all its potential applications and iterations, should be seen as the remedial route while calculus gets reserved for the more accomplished students?

Does kicking an equity issue down the road really solve it? How should we address disparate outcomes in achievement while also accepting that most students won’t go on to do college-level math? And why is there an assumption that statistics, with all its potential applications and iterations, should be seen as the remedial route while calculus gets reserved for the more accomplished students?

Beyond the question of tracking, there are debates about whether PEMDAS, the acronym many of us learned about the order of operations in a math problem, is actually the right way to do things; whether the traditional pedagogical structure, in which a teacher tells you how to do something and you do it for homework, might be totally backward; and whether the United States, which scores relatively low in math compared with other wealthy nations, is actually bad at math, or if we just have a bottleneck problem.

Last month, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation announced that it would be spending more than a billion dollars on improving math education in the U. S. As was the case in the nineteen-nineties math wars, much of the early work will focus on deploying technology, studying how students learn, and addressing racial and economic achievement gaps. According to Bob Hughes, the Gates Foundation’s director of K-12 education, the intention is to help “African American and Latino students and students of all races and backgrounds experiencing poverty,” with an emphasis on transition years, including from eighth to ninth grade, which some studies have shown goes a long way in determining whether a student will stick with math in high school and beyond.

S. As was the case in the nineteen-nineties math wars, much of the early work will focus on deploying technology, studying how students learn, and addressing racial and economic achievement gaps. According to Bob Hughes, the Gates Foundation’s director of K-12 education, the intention is to help “African American and Latino students and students of all races and backgrounds experiencing poverty,” with an emphasis on transition years, including from eighth to ninth grade, which some studies have shown goes a long way in determining whether a student will stick with math in high school and beyond.

The Gates Foundation’s math prescriptions are still not set in stone, but Hughes discussed interventions such as cutting costs in order to expand math tutoring for students who have fallen behind their grade level, implementing more digital tools, and developing curricula and classroom materials that will aim to help teachers make math both accessible and challenging. The foundation seems particularly interested in this last part: how different forms of pedagogy and instruction find their way into classrooms. “It’s very hard for quality materials to necessarily buck the trend of incumbent players in the curriculum space,” Hughes said. “So we’re thinking a lot about markets.”

“It’s very hard for quality materials to necessarily buck the trend of incumbent players in the curriculum space,” Hughes said. “So we’re thinking a lot about markets.”

The subtext of this project, as I see it, is that math education has become entirely too cluttered with a host of bad or untested ideas. The researchers at the Gates Foundation seem to believe that there’s a way to locate proper techniques, and insure that as many teachers impart them to their students as possible. For them, finding these better methods involves a lot of data, “UX studies,” and “A/B testing,” all of which can be done efficiently and quickly if students are using math-learning technology that will track their progress and proficiency.

The Gates Foundation has generally steered clear of politics. Hughes’s tone in our conversation was noncommittal, even when discussing the question of when to teach algebra—something that became controversial in the education world when the authors of the California Mathematics Framework recommended ceasing algebra instruction for middle schoolers. (“The research base is mixed,” Hughes has said. “I think that we’re going to be supporting people who believe [Algebra I] in eighth grade or ninth grade is appropriate.”) But he did offer a set of “non-negotiables,” which included a need to be “kind and gentle” with students, a focus on grounding solutions in teachers and communities, and, finally, an emphasis on getting the right answer.

(“The research base is mixed,” Hughes has said. “I think that we’re going to be supporting people who believe [Algebra I] in eighth grade or ninth grade is appropriate.”) But he did offer a set of “non-negotiables,” which included a need to be “kind and gentle” with students, a focus on grounding solutions in teachers and communities, and, finally, an emphasis on getting the right answer.

“Math is unique because there is a right answer, and I think that politicizes it, somehow,” Hughes said. “In other subjects, there may be different answers or you can have a multiplicity of interpretations. Math has a right answer; there are multiple ways to get there, but there is a right answer. We believe it’s important for kids to get to that right answer. And that’s not a universally agreed-upon notion in some quarters.”

This stands in opposition to much of the progressive push in math education, which—as Brian Lindaman and Jo Boaler, two of the authors of the California curriculum guidelines discussed in Tuesday’s column, point out—emphasizes the need for students to “struggle” together in a classroom to figure out a solution, and posits that the right answer is ultimately not as important as the problem-solving skills that are acquired through “inquiry-based learning. ”

”

The Gates Foundation seems to be trying to forge a middle path by focussing on Black and Latino math achievement without resorting to the methods of some progressive educators who have spent their careers working on that very same problem. The foundation is relying on studies, tech, and data collection as a way to both assess and correct the ways in which children learn math, under the belief that there is, in fact, a smarter way to do all this that does not fall into all the political traps of the past and present.

These fights—between the dogged pursuit of social-justice-based education and the various backlashes that try to reify the status quo—are in fact the only constant in American math education over the past century. Many people have tried to fairly assess the merits of both sides of the fight with proper historical context, and hack out the type of compromise that the Gates Foundation desires. One such person is Alan Schoenfeld, a professor of mathematics and education at the University of California, Berkeley. In an influential 2004 article about the math wars, Schoenfeld writes:

In an influential 2004 article about the math wars, Schoenfeld writes:

Even though the wars rage, partly because there are some true believers on both sides and partly because some stand to profit from the conflict, I remain convinced that there is a large middle ground. I believe that the vocal extremes, partly by screaming for attention and partly by claiming the middle ground (“it’s the other camp that is extreme”), have exerted far more influence than their numbers should dictate.

7 Strategies for Teaching Children Mathematics

Math can be a difficult subject area for many kids to grasp. While some children may understand math concepts more intuitively, it may not be easy for others. This is where your role as a parent comes in. There are several ways parents can help their little ones practice and improve their math skills in order to succeed in this subject area. Read on for some helpful strategies to help you teach your kids about mathematics.

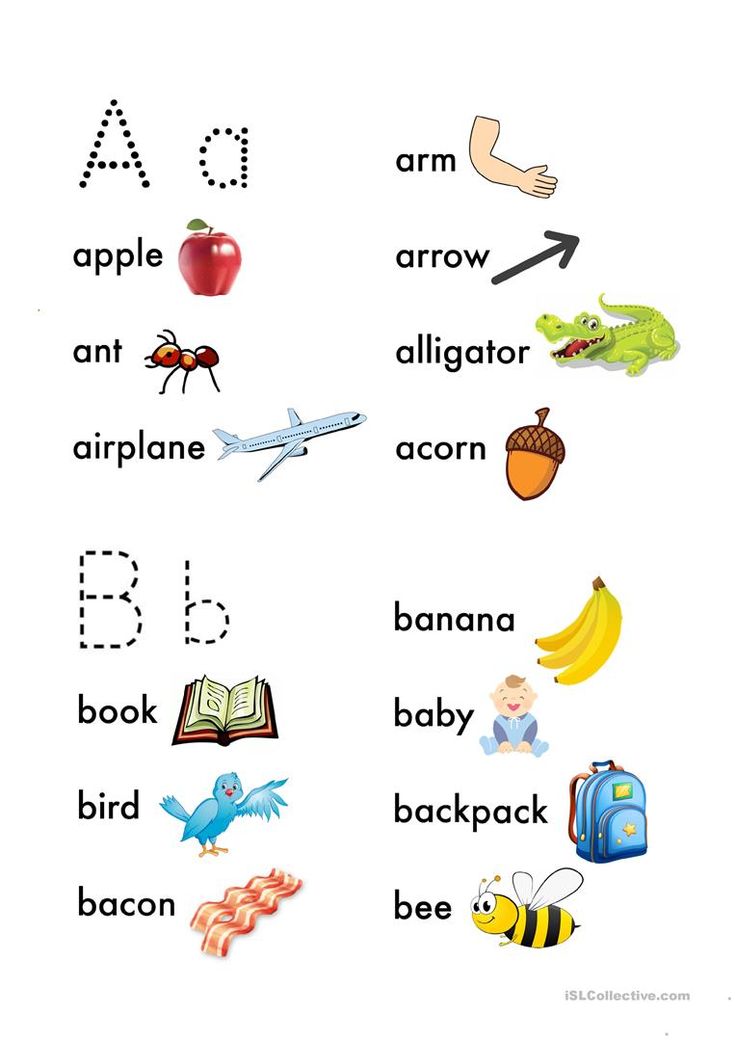

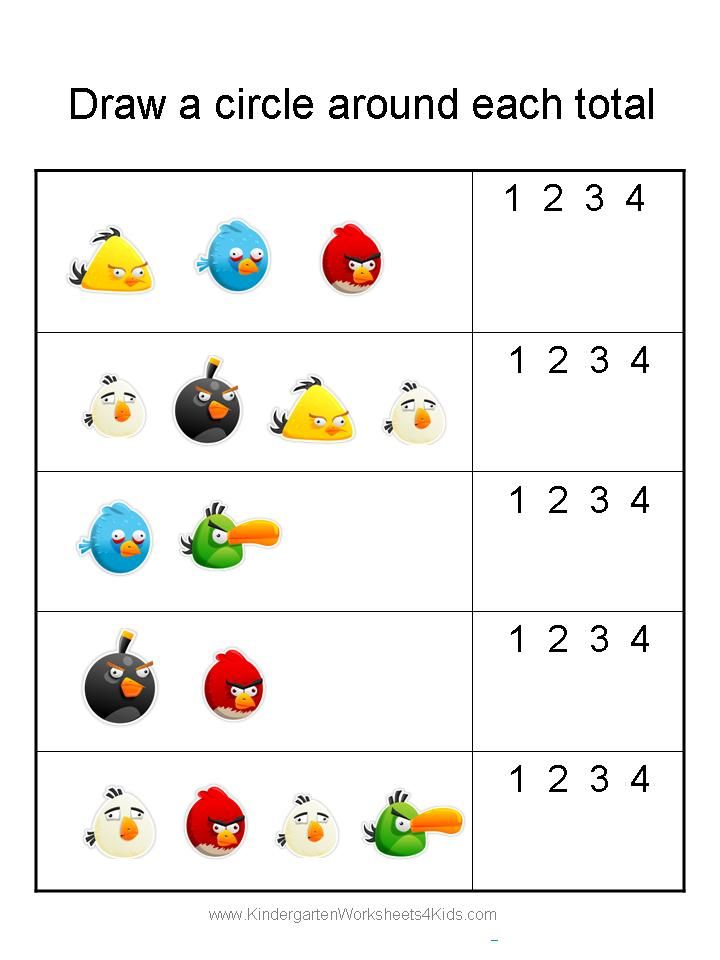

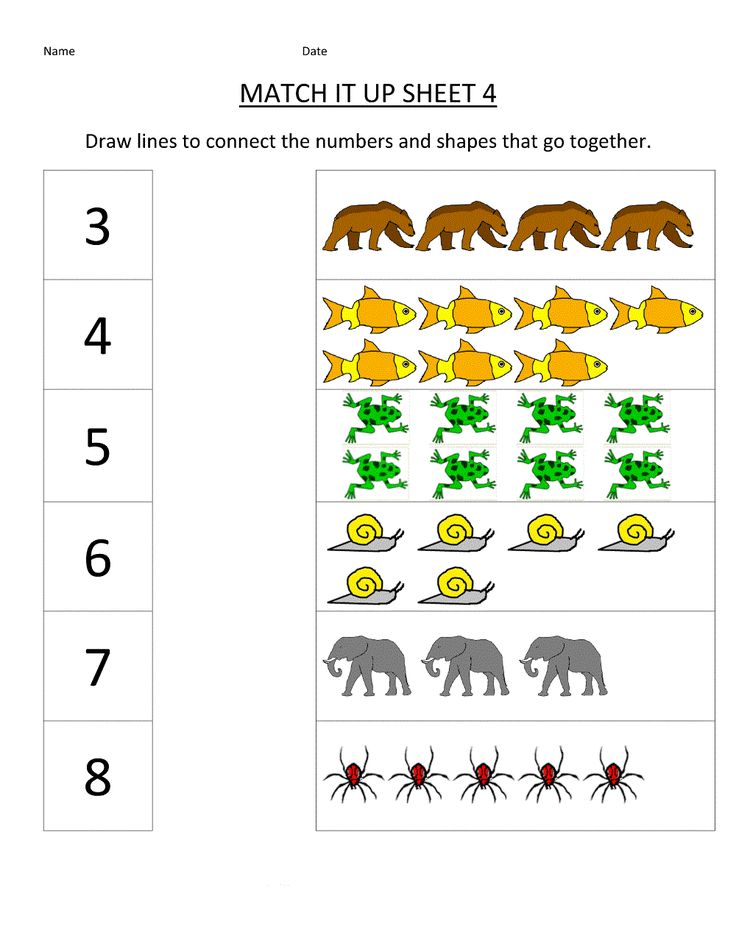

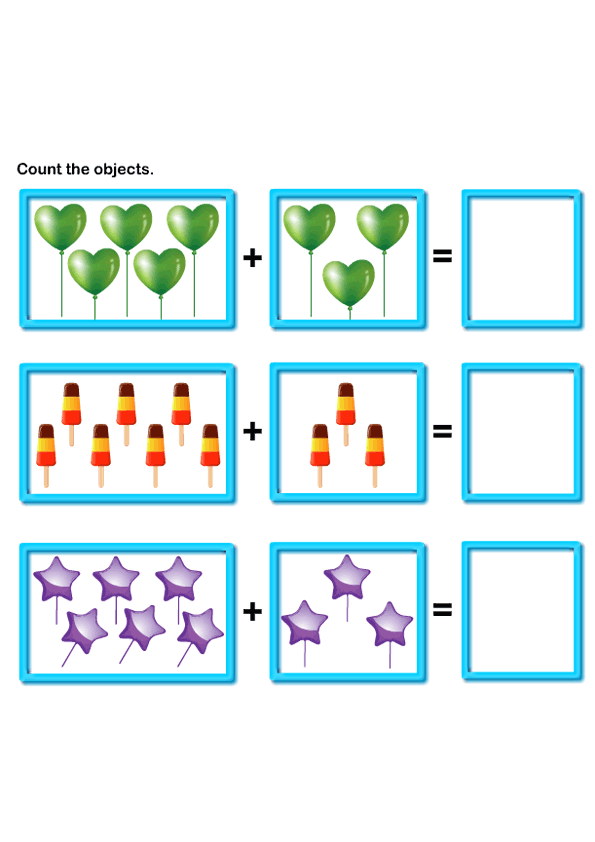

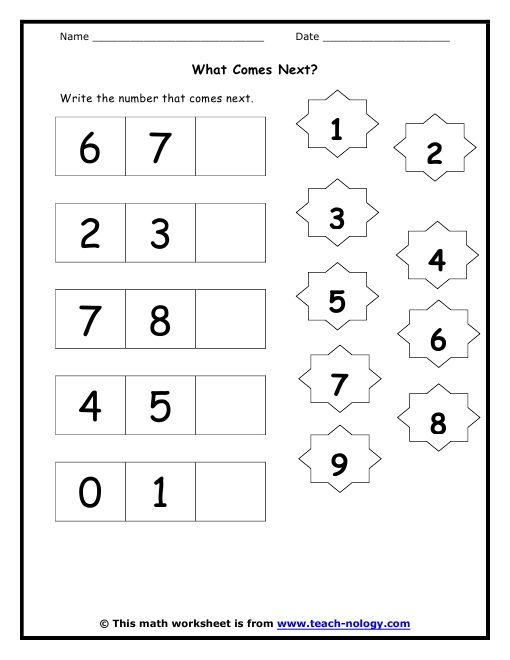

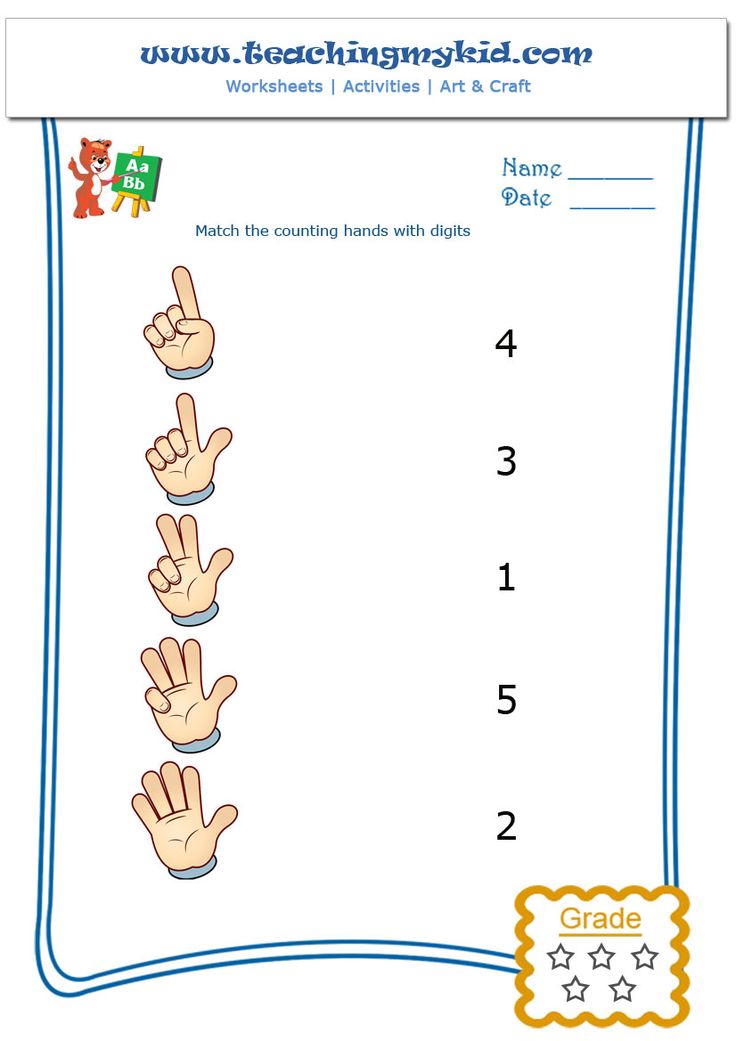

Learning math begins with counting. Believe it or not, you can start teaching your little one how to count and other simple math concepts from a very early age. For example, if you have three apples, put them on the table and invite your child to count them with you. This type of activity helps young children begin to grasp the concept of numbers in their simplest form.

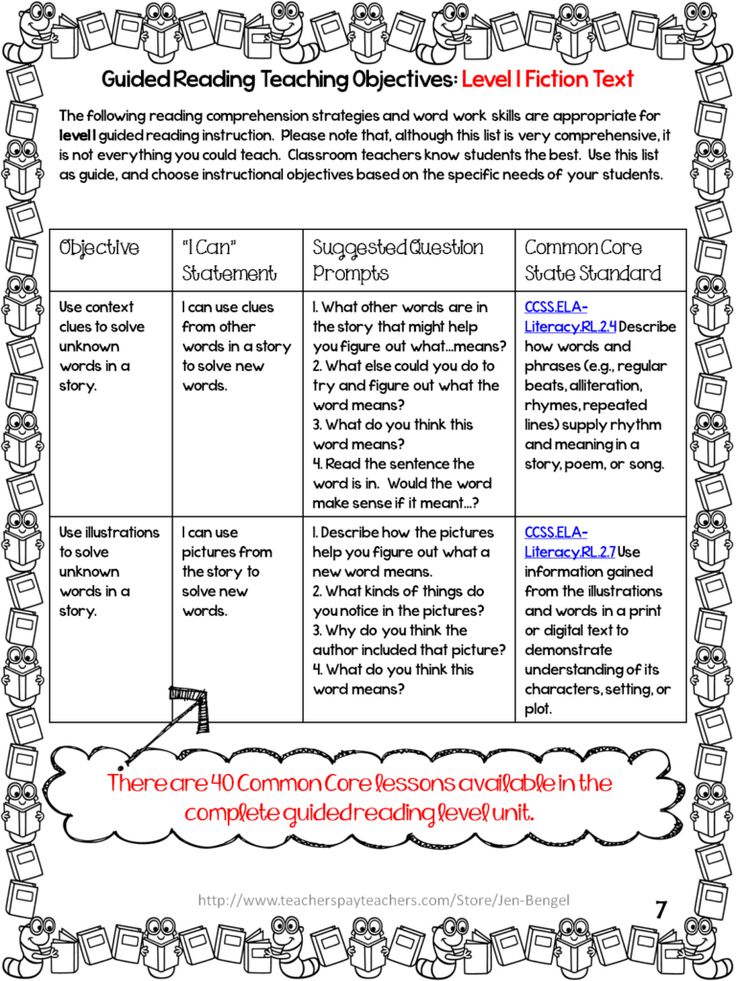

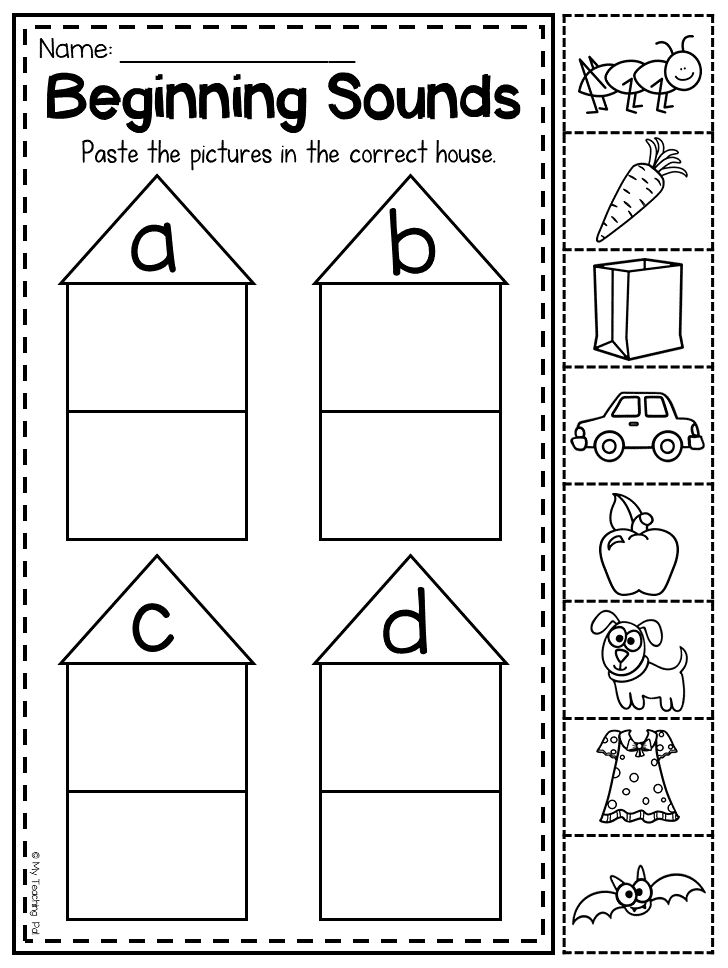

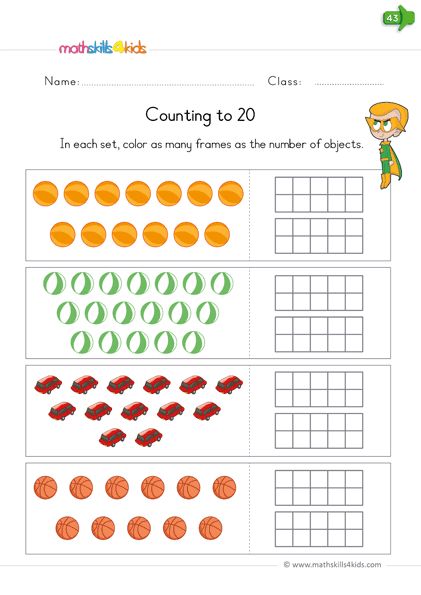

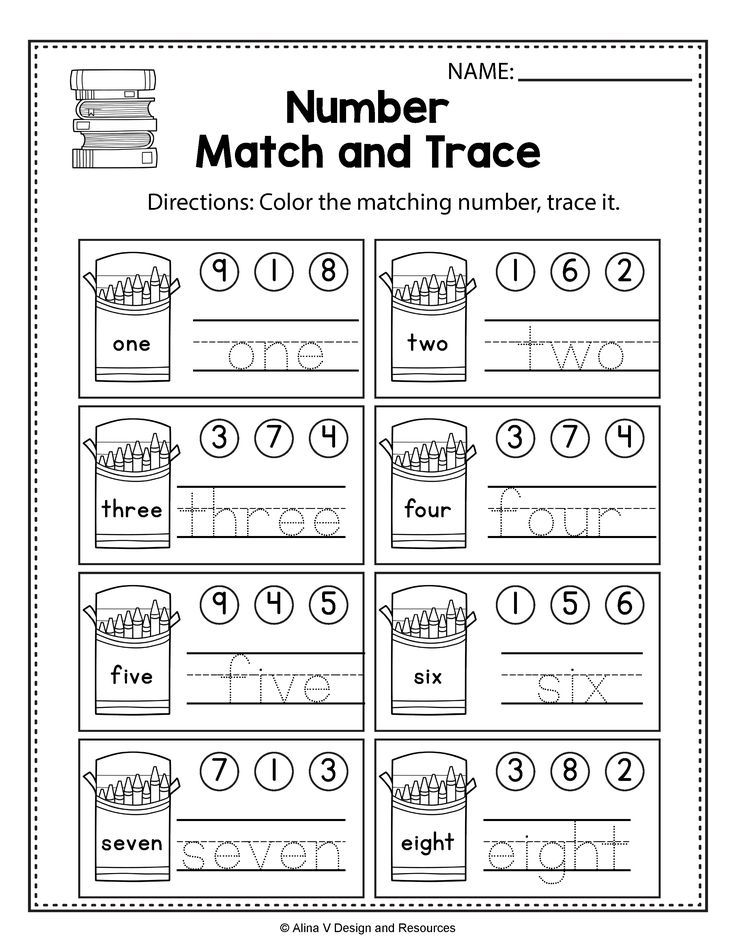

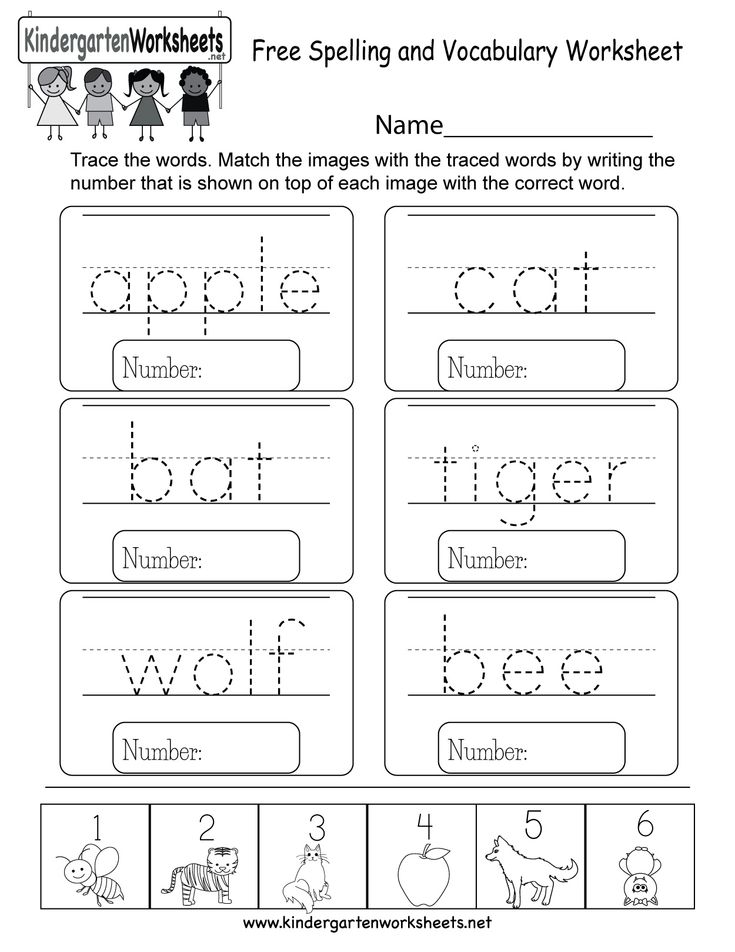

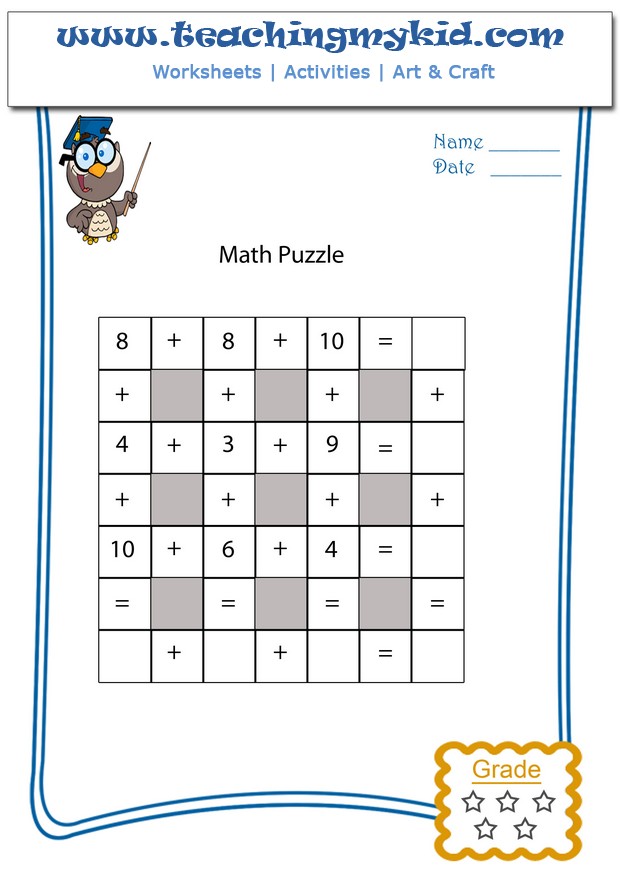

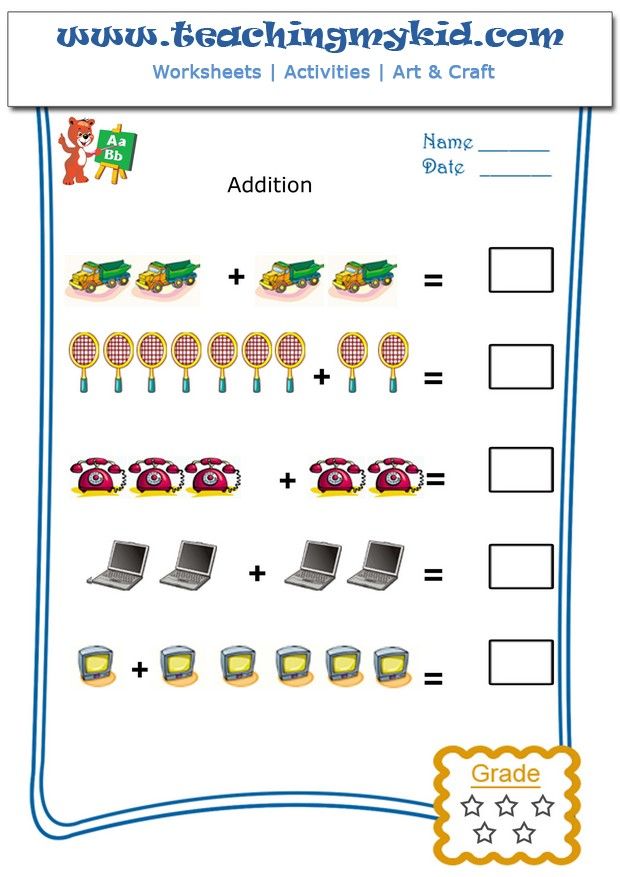

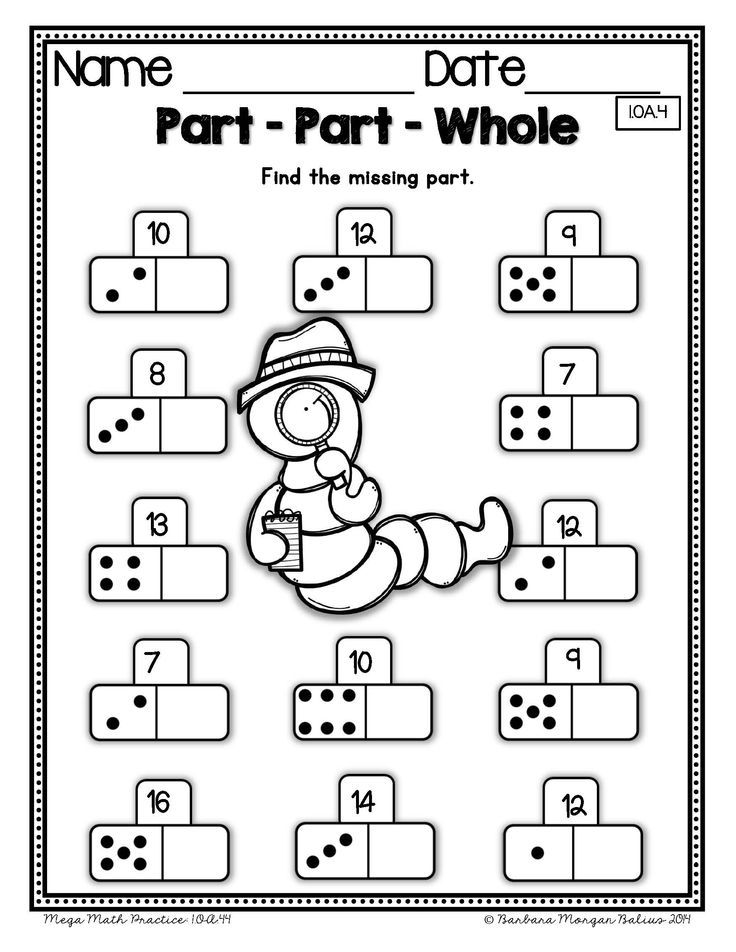

2. Use picturesPictures are helpful tools when teaching children math concepts. Incorporating visual aides and pictures can make concepts easier to understand for kids who are just beginning to learn how to count. In addition to helping children learn what each number looks like, pictures can also be used to teach kids about addition and subtraction. If your little one is having trouble grasping these types of basic math concepts, pictures can make all the difference.

3. Make flashcardsFlashcards are also effective teaching tools when teaching kids mathematics. They provide a hands-on learning experience, and can be made easily at home with everyday items you might have on hand. For example, if your child is struggling to remember what number five looks like, there’s no need to go out and purchase expensive flashcards from the store. Instead, grab some index cards and write numbers one through five on each card with a marker. Then use a dry erase marker or crayon to draw the corresponding amount of objects on each of the dots representing that particular number. In this case, draw four stars on four dots and five stars on the fifth dot. Do this for each of the numbers one through five.

They provide a hands-on learning experience, and can be made easily at home with everyday items you might have on hand. For example, if your child is struggling to remember what number five looks like, there’s no need to go out and purchase expensive flashcards from the store. Instead, grab some index cards and write numbers one through five on each card with a marker. Then use a dry erase marker or crayon to draw the corresponding amount of objects on each of the dots representing that particular number. In this case, draw four stars on four dots and five stars on the fifth dot. Do this for each of the numbers one through five.

Learning about math doesn’t have to be a dull, boring experience for kids. There are plenty of ways to incorporate math concepts into your daily life in ways that make learning more exciting and engaging.

For example, if your little one is learning about fractions, you can cut up an apple into two equal sized pieces so your child can see what “half” looks like. Kids are often able to grasp the concept more easily when teaching is woven into their everyday lives rather than from a textbook or in a traditional classroom setting.

Kids are often able to grasp the concept more easily when teaching is woven into their everyday lives rather than from a textbook or in a traditional classroom setting.

There’s a variety of ways you can teach your child about various math concepts by incorporating hands-on teaching tools, many of which you can find around your home or at school. While these teaching aids are primarily intended to teach children how to count, they can also be used to help them learn other basic math concepts as well. Give some thought to how your child might learn best before introducing any of these teaching tools. Otherwise, they can prove to be more a distraction than an asset for both of you.

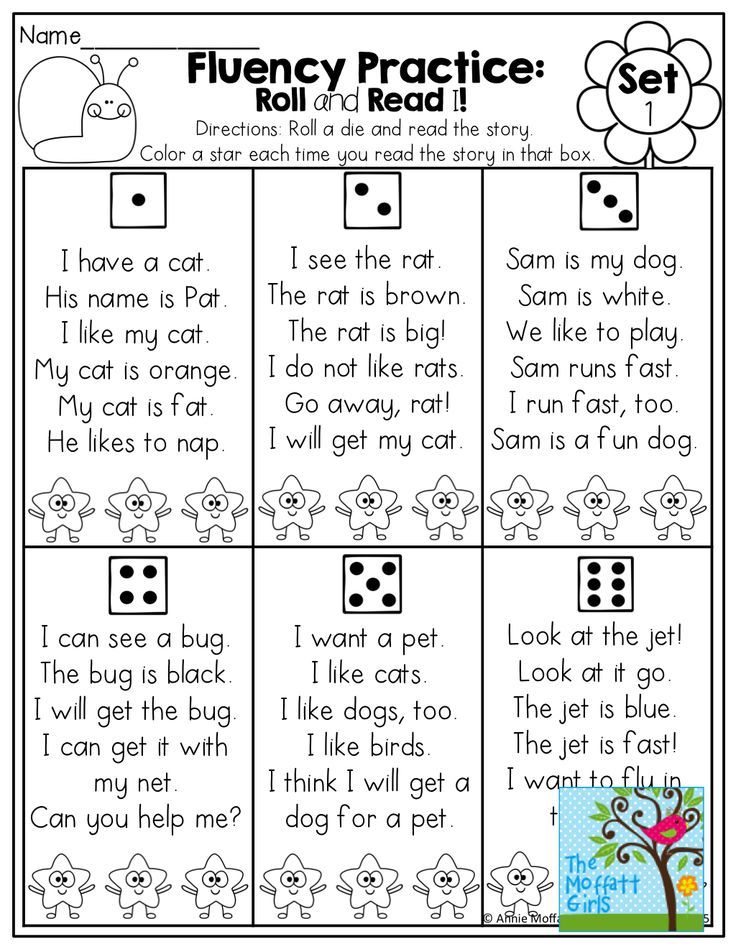

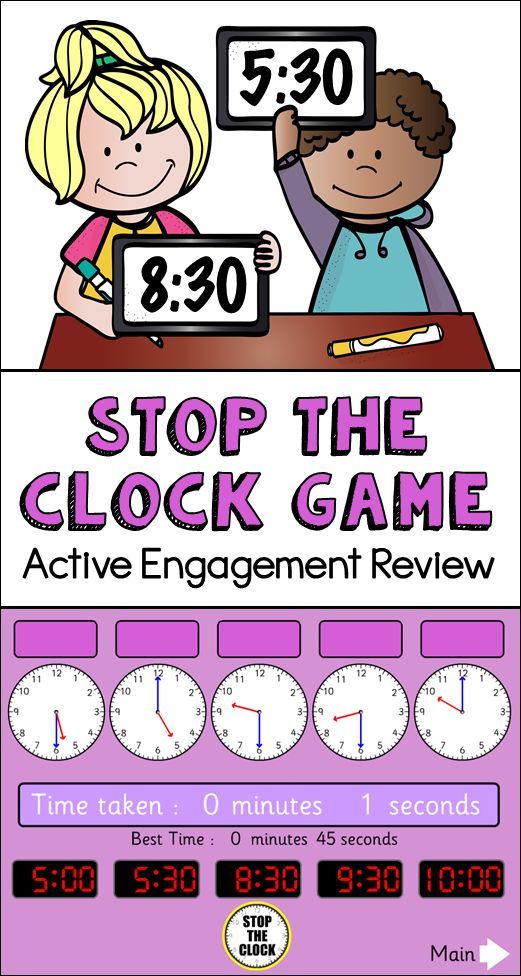

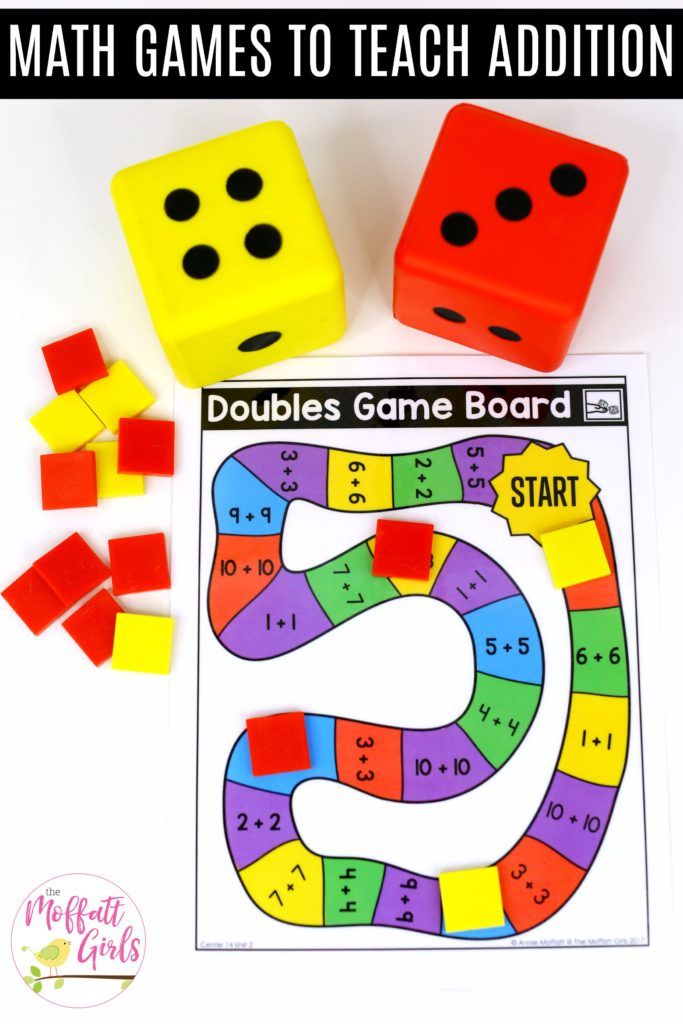

6. Play math gamesMath games are a simple and fun way to help kids learn how to solve math problems while they’re having fun. Games like Yahtzee, Baffle, and Dominoes all use the process of addition. To make learning more accessible for your little one, you can teach them how to play a variety of math games at home with everyday items you have on hand.

Teaching kids about mathematics is even easier when you use everyday items. For example, you can always use a ruler to teach kids about measurements, and an egg carton is a great tool to demonstrate the concept of multiplication with small groups of objects.

These are just a few of the easy ways you can use to help reinforce basic math concepts with children. Follow these tips to start teaching your little one about math quickly and effectively. Math concepts are an integral component of your child’s academic journey, as they are needed in order to succeed in school and beyond. Follow these tips to make learning math more fun and engaging for your child.

At The Pillars Christian Learning Center, we strive to empower children by identifying, acknowledging, and appreciating the diverse needs and talents of each child, and helping them know and understand they are accepted and valued for their uniqueness. Visit our website to learn more!

Why is it necessary to study mathematics with a child

Why is it necessary to study mathematics? Every child asks such a question to his parents, not fully understanding how such a complex subject is useful in life. In this article we talk about the role of learning mathematics in the development of a child and explain how to awaken motivation for classes.

In this article we talk about the role of learning mathematics in the development of a child and explain how to awaken motivation for classes.

⠀

The role of mathematics is really huge in our life. Without this science, the world would be different. If it did not develop, there would be no great discoveries, there would not be those things that we use today. Now more specifically, why you need to love counting from the cradle.

1. Mathematics trains memory

Memory is one of the most important functions of the psyche, on which other processes are built. Therefore, from early childhood, the child must be taught the ways and techniques of effective memorization of information.

⠀

Early math lessons that are related to counting will help with this. There is an opinion that if children count well, then they have a mathematical mindset. But is it? Not really. Memory and thought processes develop only if the counting is done consciously, and not mechanically.

⠀

Until the age of 7, children use their fingers or various objects to count. But this skill alone will not develop mathematical thinking. It is the solution of problems that trains the brain and memory, develops the flexibility of the mind, helping to understand the relationship and cover the whole problem in order to find non-standard ways out of various situations.

⠀

Conclusion: solve problems with your child to develop memory.

2. Mathematics teaches you to think

Regular training in the gym strengthens the body, and constant practice of mathematics trains the mind. In the process of computing activity, the child improves:

- ability to reason and analyze;

- think logically;

- highlight the main thing;

- structure and draw conclusions.

See also: “How to develop creative thinking in a child at home? TRIZ Methods for Children from 5 Years Old»

Here is an example of home games that will help a child develop creative thinking.

3. Mathematics teaches you not to give up and not stop there

To solve a problem correctly, children need to be precise, attentive, responsible and persistent.

⠀

The more often your son or daughter pumps these skills, the smarter he will become. In the future, this will help not only with studies, but also in life.

4. Music and mathematics: where is the connection?

Did you know that the same area of the brain is responsible for the development of musical and mathematical abilities? Or that some musical hits gain popularity due to their "mathematical" structure?

For example, hip-hop wins the hearts of young people with repetitive improvisations and rhythmic beats. Such love is due to the innate need of people for repetitive elements and rhythm.

It follows that parallel studies in these two areas will help your child become the Albert Einstein or Sherlock Holmes of his time in the future.

5. Math Helps You Succeed in Other Sciences

Early math classes lay the foundation on which to build your ability in other school subjects. If you look at different disciplines more broadly, you can see that geography, chemistry, physics, biology, drawing are closely related to mathematics.

If you look at different disciplines more broadly, you can see that geography, chemistry, physics, biology, drawing are closely related to mathematics.

⠀

From observations: if a student has problems with algebra and geometry, in 95% of cases he will also have difficulties with physics and chemistry.

⠀

The conclusion is obvious - build a solid base by doing mathematics with your child from early childhood.

6. Everyday tasks seem less complicated and are solved faster

The longer and deeper the child studies mathematics, the better he copes with daily activities in all areas of life. Accurate calculations and calculations teach to reason, think through algorithms of actions and build sequences. Thanks to mathematics, the child learns to check the facts and get to the bottom of the truth, and not to speculate. Learn from life situations and draw conclusions.

⠀

Read here how to develop logical thinking and prepare a child for learning mathematics with the help of simple games.

7. Learning mathematics and developing thinking is the key to success in a career

The modern world is an era of technological development, where IT workers are the most in demand. And one cannot do without a mathematical mindset: the ability to calculate well, think critically and strategically, and build complex algorithms.

⠀

If you want your child to master the profession of the future, do math with him.

In conclusion, we want to talk about motivation. With preschoolers and younger students, use play in the classroom. This form of presentation of information is understandable and interesting to children. Take on board various methods of conveying information: mobile and role-playing games, question-answer, exercises.

⠀

When organizing a lesson, consider the age and individual characteristics of the child. Then he will study at his own will and with burning eyes, and the results will not be long in coming.

⠀

Read also:

The child does not want to study: what are the reasons and what should parents do?

Rules of motivation in teaching preschool children

6 reasons to teach your child in an online school

How to help your child with mathematics

Why do children not like mathematics? Because she's complicated. It's not easy to teach a child math, figure out how to solve equations, or convert fractions to decimals. While developing math skills, the child has to solve complex problems. And if we take into account that only he will understand one topic, another no less difficult one appears after it, then it becomes clear why children do not understand mathematics. What to do?

It's not easy to teach a child math, figure out how to solve equations, or convert fractions to decimals. While developing math skills, the child has to solve complex problems. And if we take into account that only he will understand one topic, another no less difficult one appears after it, then it becomes clear why children do not understand mathematics. What to do?

What do children learn when they learn math

If you ask a child the question “Why study math?”, in most cases, he will answer: “To go to the store, to be able to count money, etc.”. Many adults will respond the same way. Does the study of mathematics really have such a prosaic meaning? Let's figure it out. After all, this is the reason why the child does not understand mathematics. Ability to reason logically and think critically. Mathematically savvy children are able to solve not only mathematical, but also life problems. They are logical, consistent, able to see what does not lie on the surface. In addition, mathematics develops an extremely important and demanded skill in our time - critical thinking. Here is an argument in favor of how important it is to love mathematics.

In addition, mathematics develops an extremely important and demanded skill in our time - critical thinking. Here is an argument in favor of how important it is to love mathematics.

Good memory.

From the very first days of studying mathematics, we remember something, we keep it in our minds. A good memory is the key to successful learning in all subjects. Therefore, understanding how to teach mathematics miraculously affects all studies.

Willpower.

Patience, perseverance, passion, bringing things to the end - all this is developed by mathematics. After all, it is so interesting to get to the point, to solve a complex example, to cope with a task.

Real application.

Often children do not understand how to apply school knowledge in life, so motivation is lost. Mathematics is found in many everyday moments: from a banal trip to the store to the opportunity to help dad figure out the navigator.

Why a child does not understand mathematics

Mathematical rules are important not only to know, but also to be able to apply them in practice, to use what has already been learned to gain new knowledge. But sometimes difficulties arise and the question is how to explain mathematics to a child. We tell you what schoolchildren usually “stumble” on in mathematics.

But sometimes difficulties arise and the question is how to explain mathematics to a child. We tell you what schoolchildren usually “stumble” on in mathematics.

1. The child is in a hurry

The child tries to do everything as quickly as possible. But it turns out to be a “blunder”: he confuses signs, incorrectly formats examples, incorrectly opens brackets. And in mathematics, one mistake leads to another.

2. The old rule is better than the new one

The student tries to solve new problems according to the old rules. For example, when a child is learning fractions, he may insist that ¼ is greater than ½. He knows that 4 is greater than 2 and is guided by it.

3. “Automatically”

The student “automatically” responds to the type of task without going into particulars. Suppose the child correctly solves the example "3 + 3" = "6". Then he sees "3 - 3" and writes "6" again, because he reacted to two triples. It's not that he can't subtract, he just wrote the first thing that came to mind without taking the sign.

4. “I forgot what it was…”

We use working memory to keep intermediate answers in mind while solving a complex problem. Some children find this difficult. You need to keep in mind the formula, algorithm or answer of the previous action, but if the working memory is not developed, then this is difficult to do.

5. Working on mistakes

Self-control is necessary to do the correct work on mistakes or to double-check the finished homework. Let's say a child quickly finishes a math test, but doesn't come back and check their work, even though they have time. Either in his picture of the world there is no idea to double-check what has already been done, or he does not understand what kind of verification is needed in each specific case. Therefore, doing work on the mistakes will allow you to find the answer to the question of what to do if you do not understand mathematics.

We cannot cancel math lessons, but we can help your child realize how useful it is by making math problems a part of his daily life.

How to captivate a child with mathematics

How to begin to understand mathematics? Take advantage of our proven tips.

1. Connect math concepts to life. If children are explained how to apply the knowledge gained in the lessons in reality, it becomes clear to them why all this is needed. For example, any person solves mathematical problems every day: for example, in a store.

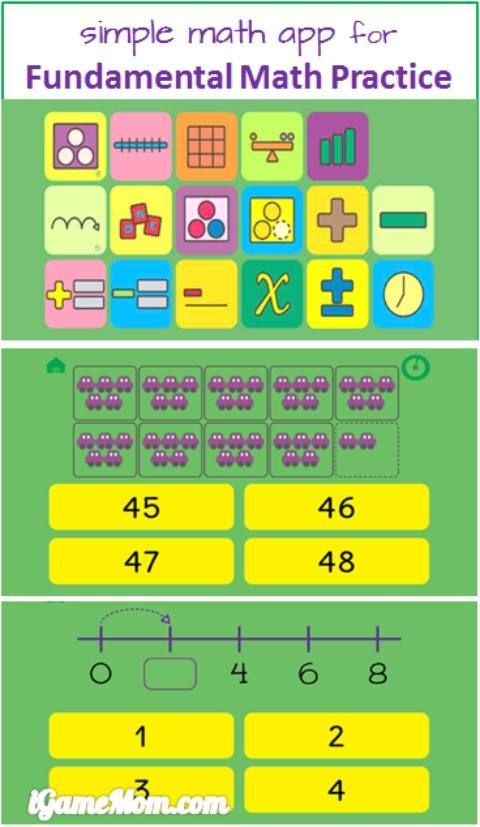

2. Play math games. Both computer and board games perfectly train mental counting skills and reaction speed. The advantage of "tabletops" is that they can be played by the whole family.

3. Solve logic problems with a catch. For example: “There were four pears and three apples on the apple tree. How many apples grew on an apple tree? Children notice the catch and it amuses them a lot, as a result, memorization is more efficient.

4. Read entertaining books about mathematics. For younger students, Vladimir Levshin's cycle about the adventures of the Master of Scattered Sciences and his assistant Edinichka, as well as "Entertaining Arithmetic" by Yakov Perelman, is suitable.

5. Participate in online math quizzes. Thanks to interesting and sometimes funny tasks, the child will understand that serious mathematics can be exciting and fun. And help him see how easy it is to fall in love with mathematics.

6. Use progressive teaching methods. For example, online simulators on the iSmart educational platform:

- interactive math tasks are fun and more like a game;

- the child will quickly understand school mathematics;

- will bring computing skills to automatism.

How to fix your grades in math

- Do a little math every day.

- Encourage your child to solve everyday problems. Regular training will help him understand why all these numbers are needed.

- Work well in every lesson.

- Pay more attention to your homework.

- Prepare carefully for tests.

Interestingly, studies have found that children aged 8 to 10 who practiced math at home for 15 minutes a day, 5 days a week, improved their performance by 60%. Is everything simple? Yes! And you will be able to see for yourself how to help a child with mathematics in a relatively short period of time.

Is everything simple? Yes! And you will be able to see for yourself how to help a child with mathematics in a relatively short period of time.

How to prepare for a math test

Learning how to start understanding math will help your child feel confident on tests. Here are some helpful tips to help you get through this daunting task.

1. When the teacher says that a similar task will be on the test, make a note to yourself so that you know which tasks to focus on.

2. Write down all the topics that will be on the test, and select examples and tasks from the textbook for them.

3. Learn theory in time: theorems and formulas.

4. Solve, solve, solve... The more typical tasks you complete, the better you will hone the solution algorithm.

5. Be sure to review all your notebooks in which you solved problems.

On the test:

6. First, solve simple tasks in a draft and only then proceed to more difficult ones.