Kids reading phonics

Phonics Instruction | Reading Rockets

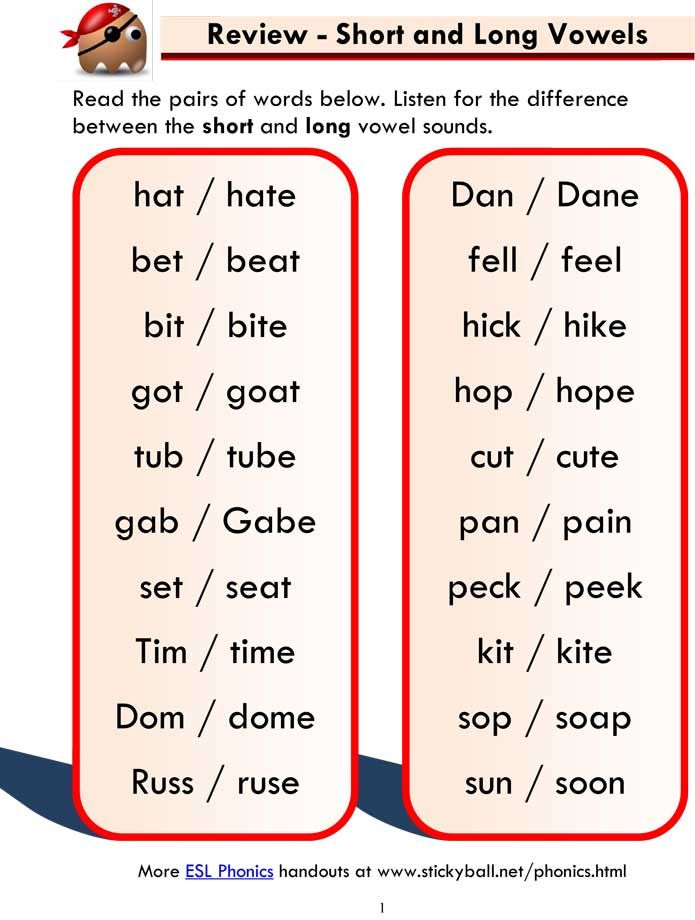

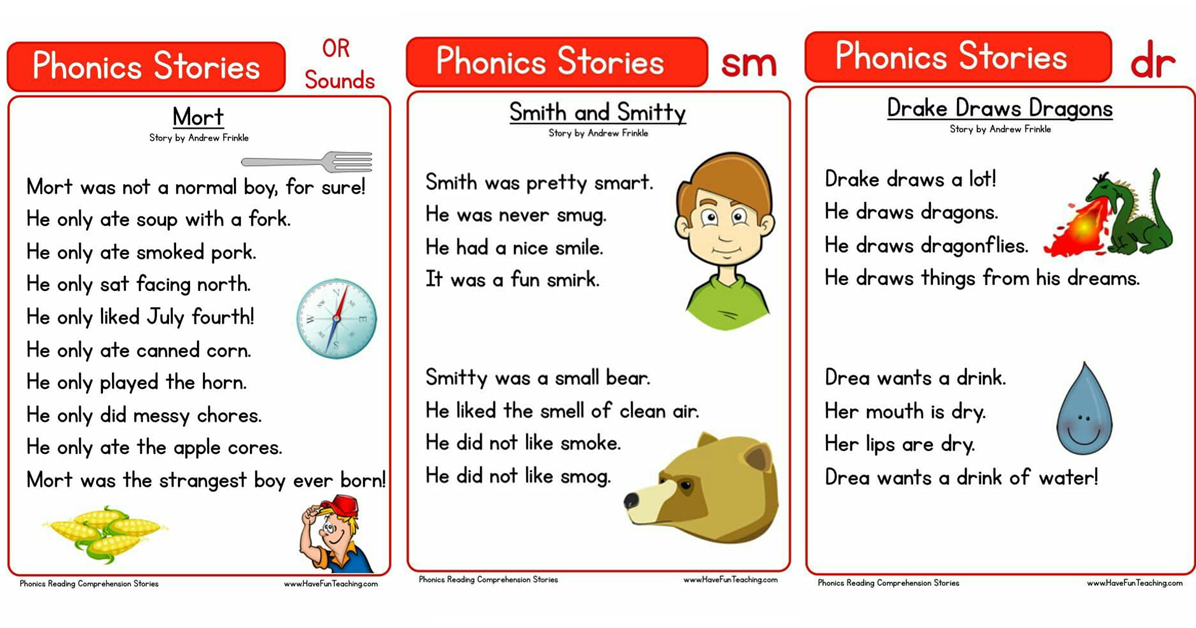

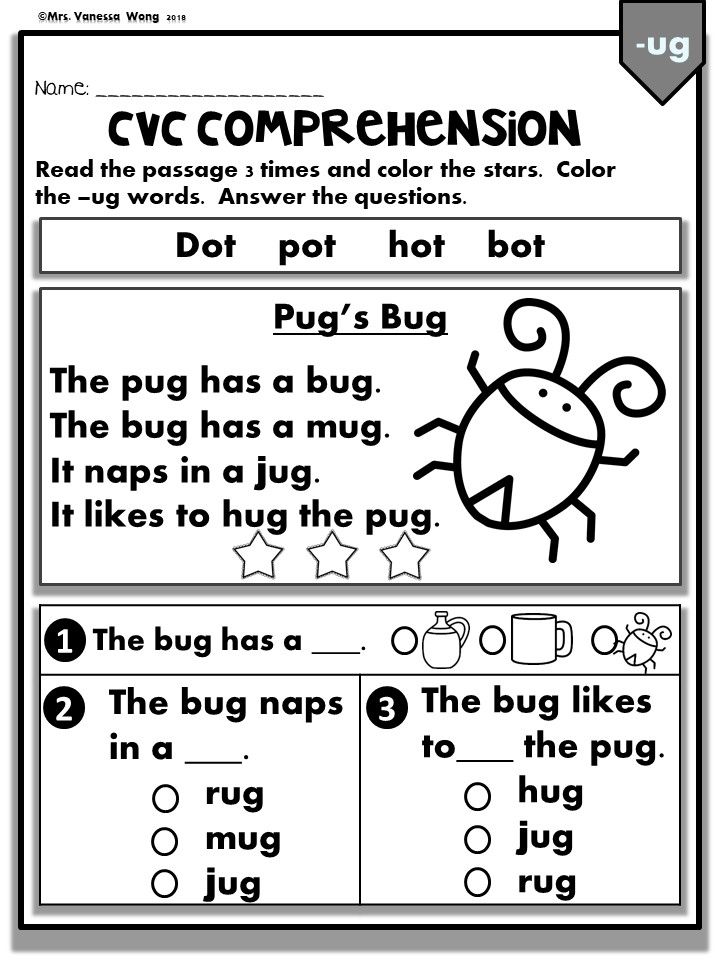

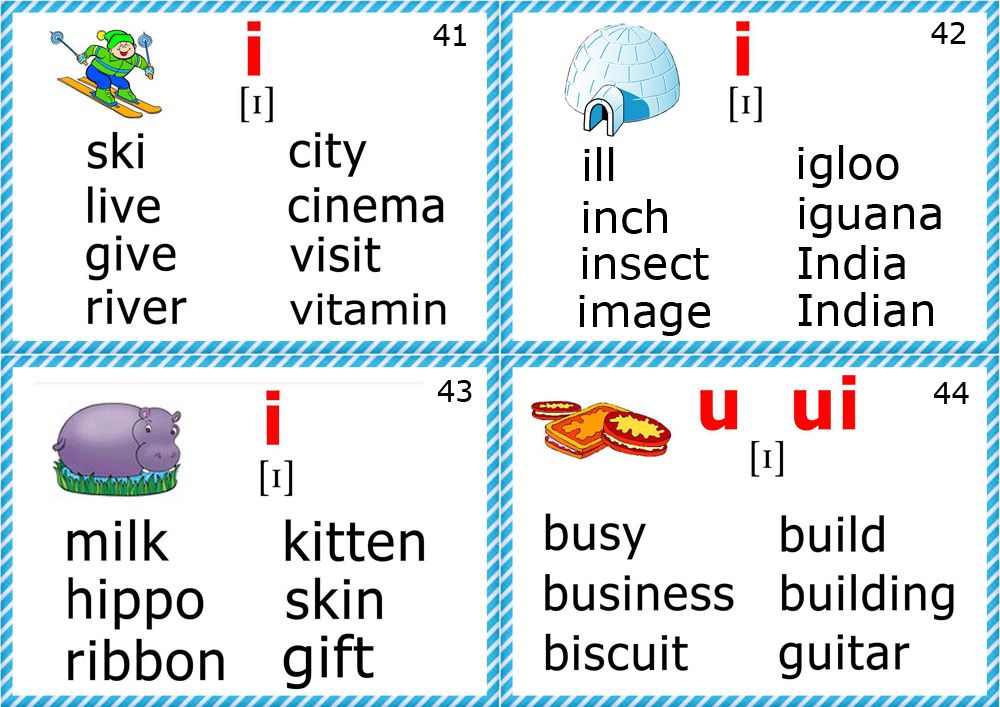

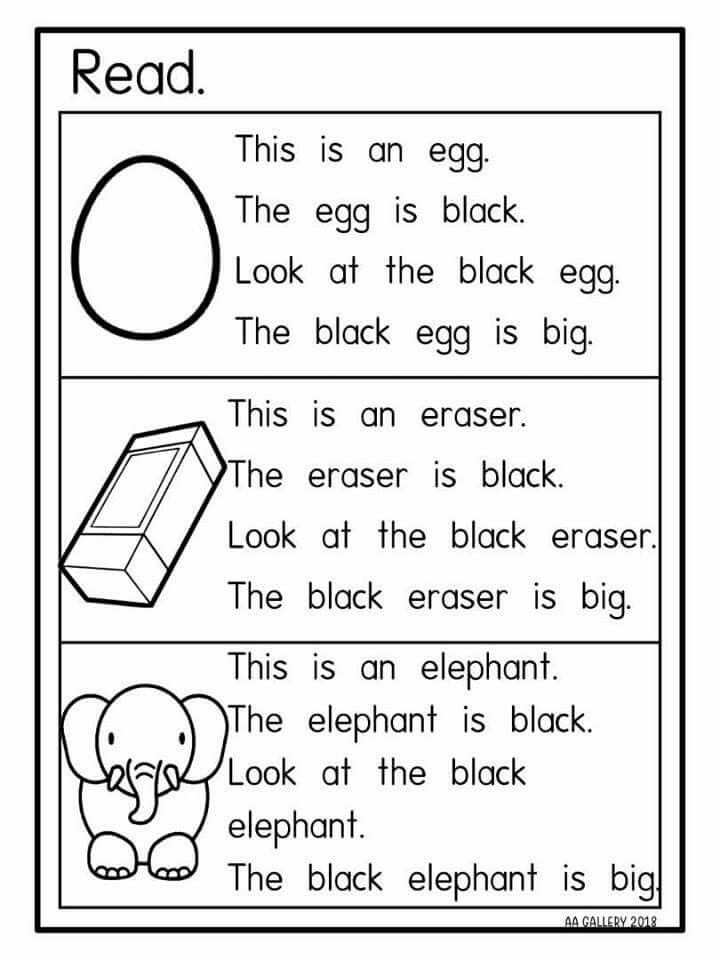

The primary focus of phonics instruction is to help beginning readers understand how letters are linked to sounds (phonemes) to form letter-sound correspondences and spelling patterns and to help them learn how to apply this knowledge in their reading.

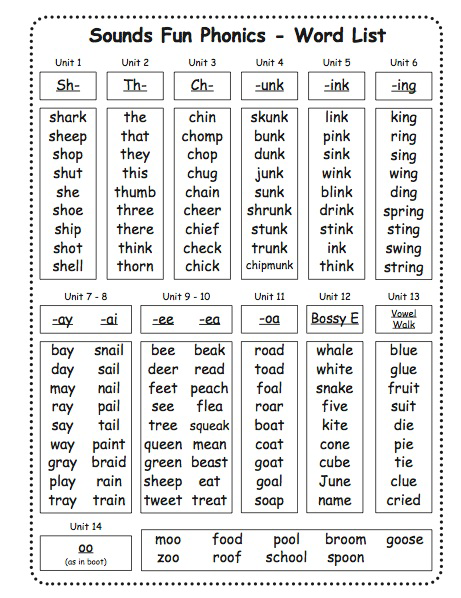

Phonics instruction may be provided systematically or incidentally. The hallmark of a systematic phonics approach or program is that a sequential set of phonics elements is delineated and these elements are taught along a dimension of explicitness depending on the type of phonics method employed. Conversely, with incidental phonics instruction, the teacher does not follow a planned sequence of phonics elements to guide instruction but highlights particular elements opportunistically when they appear in text.

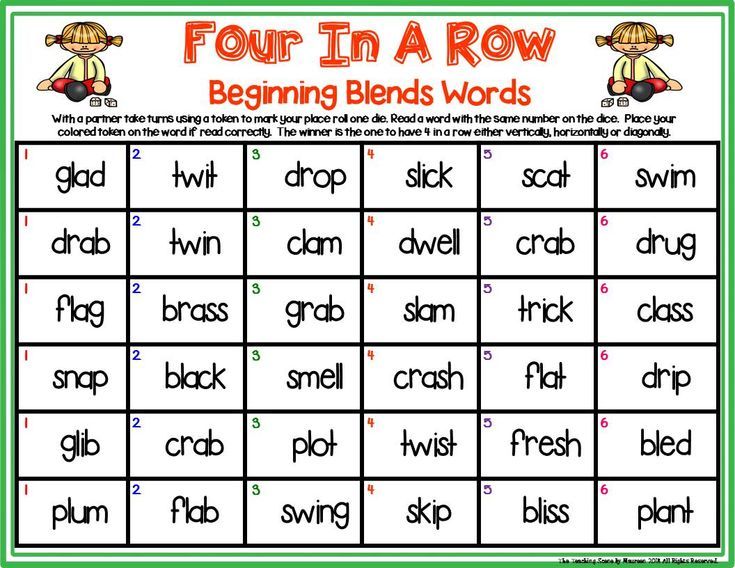

Types of phonics instructional methods and approaches

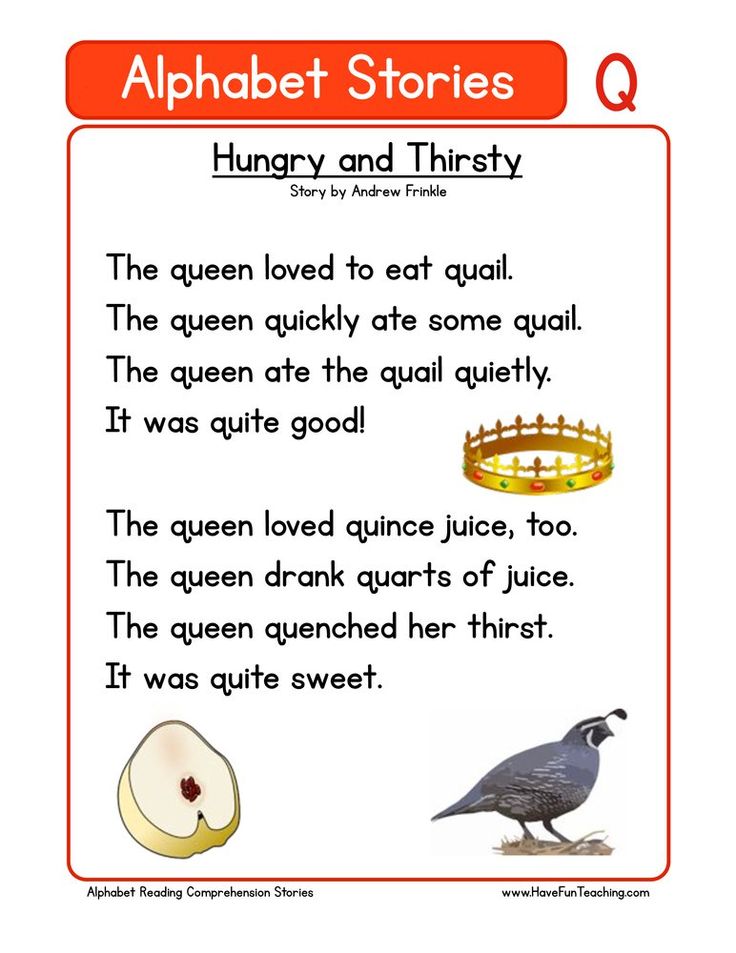

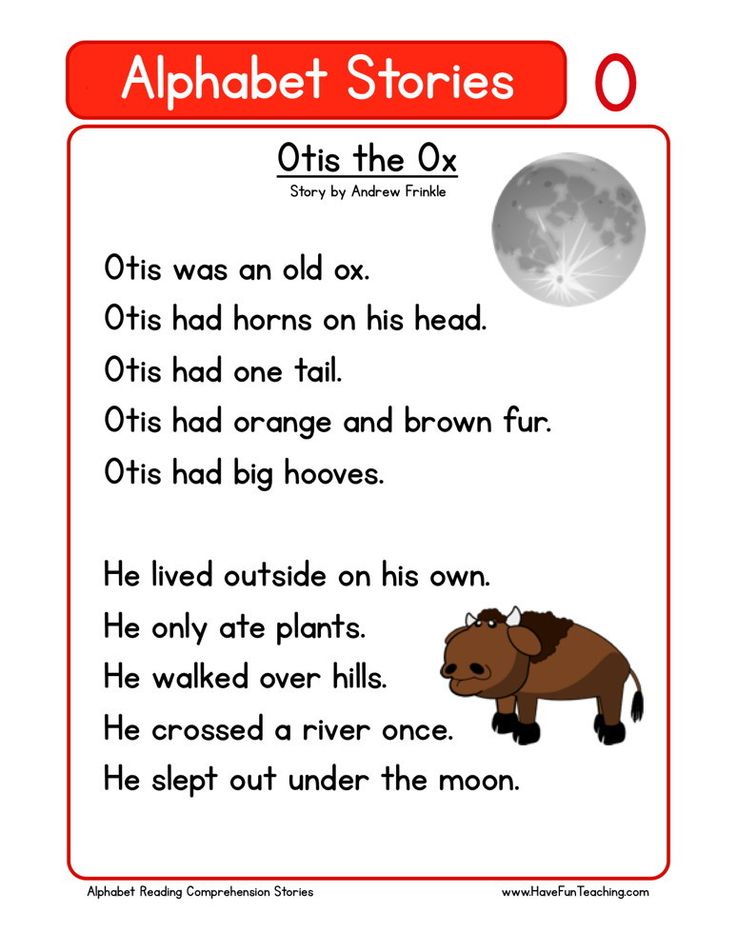

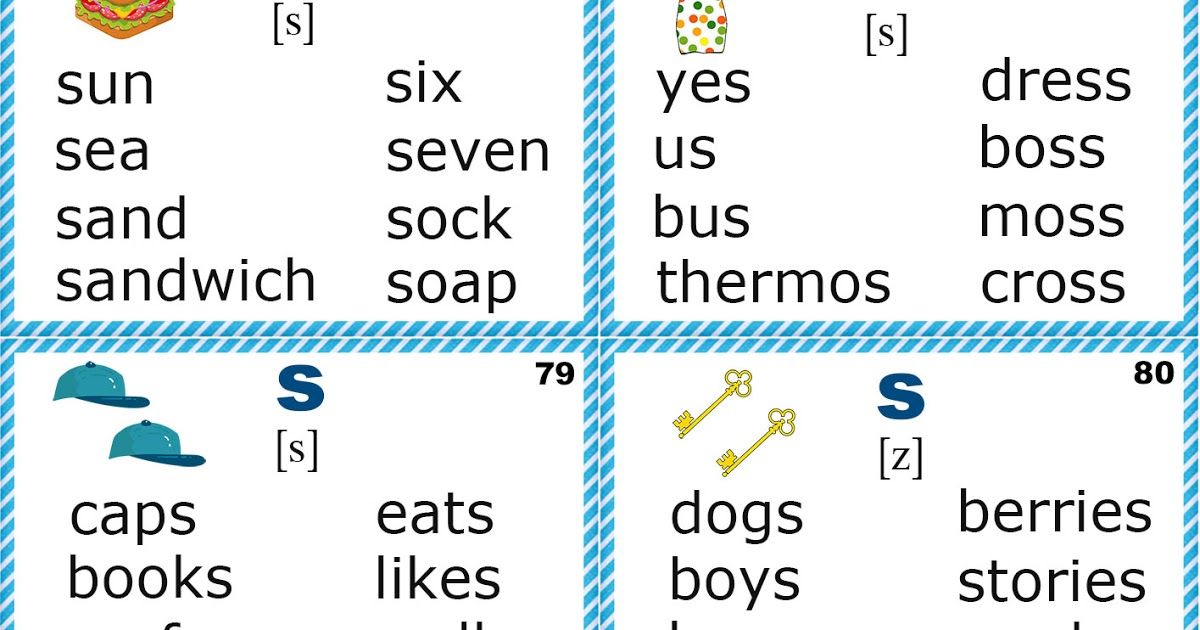

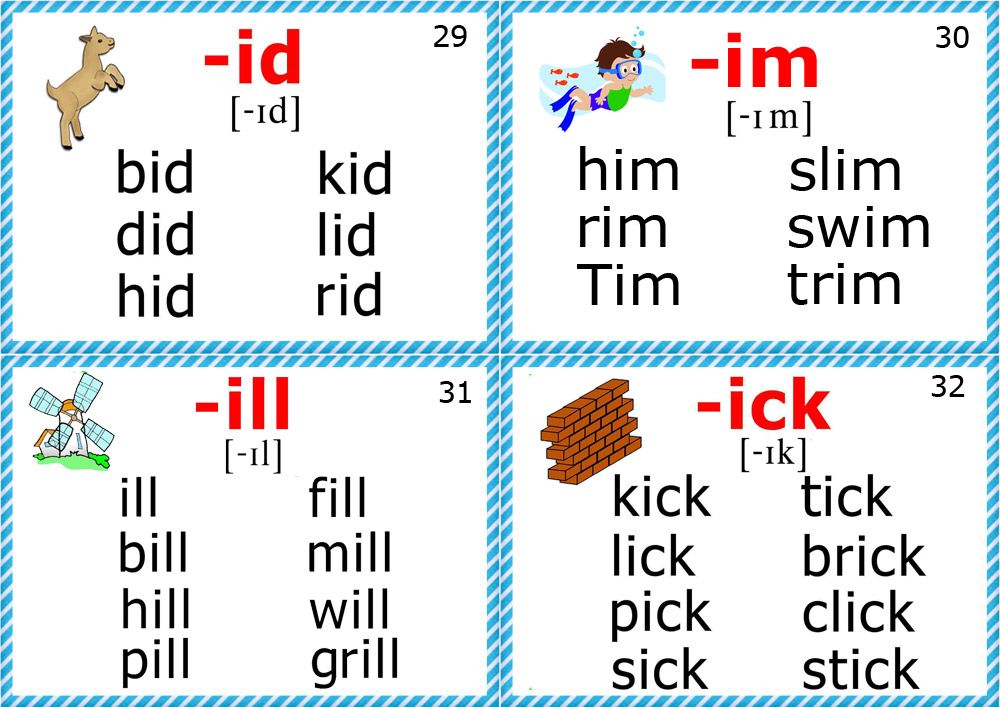

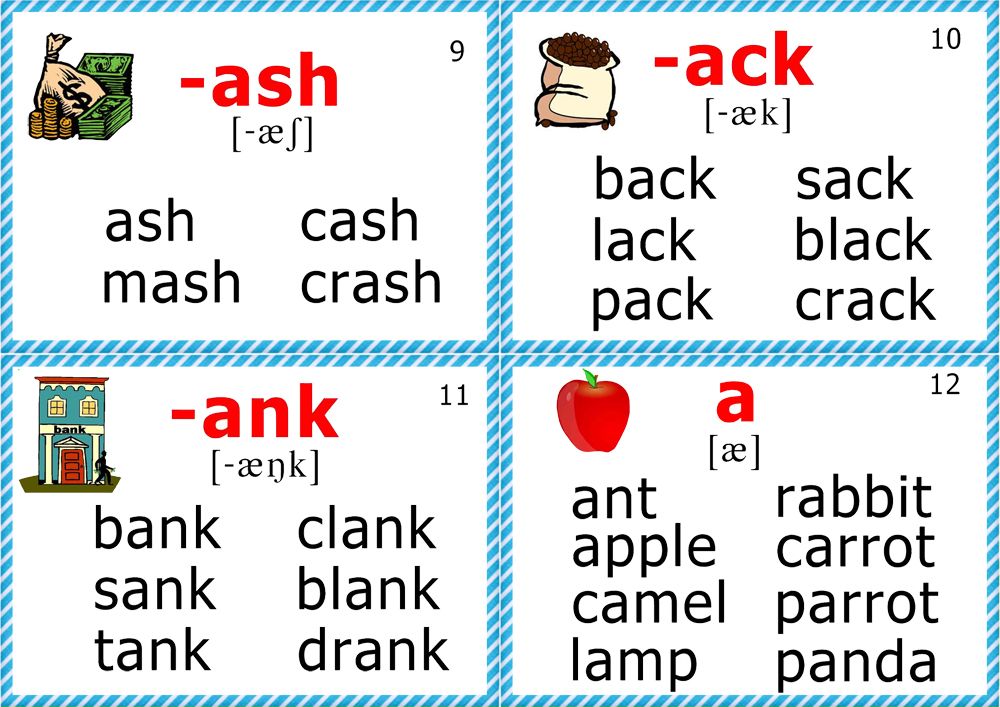

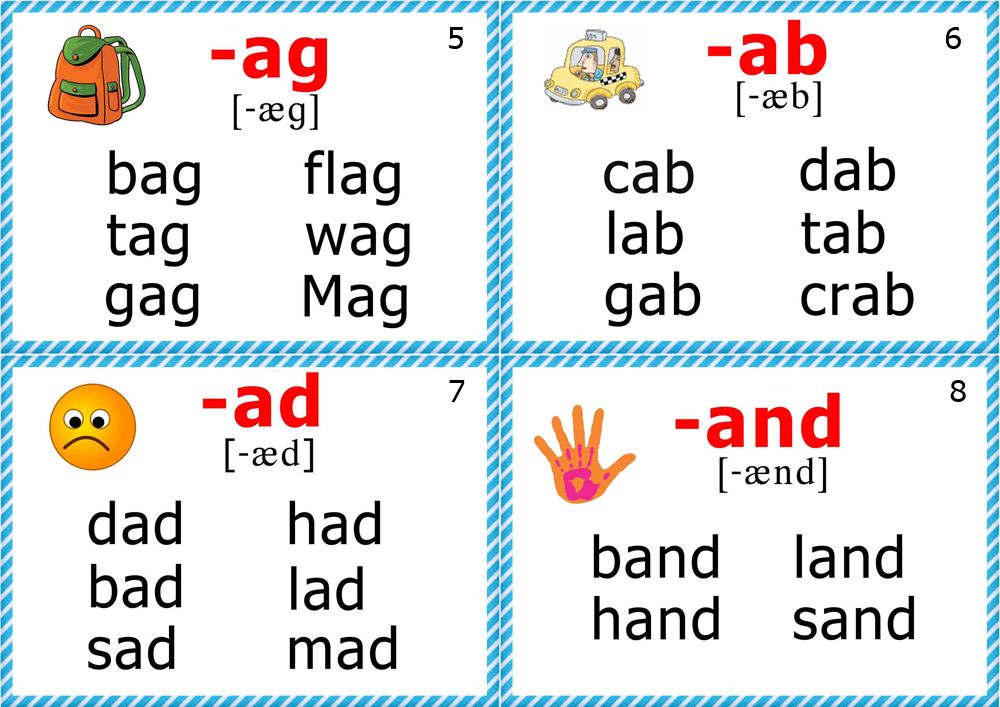

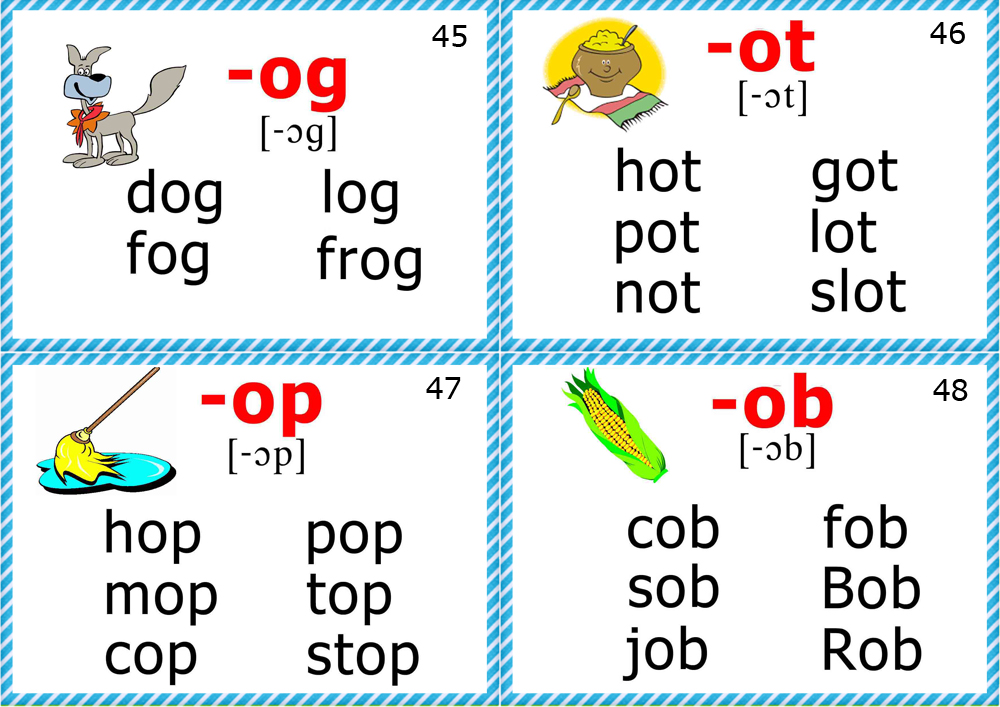

This table depicts several different types of phonics instructional approaches that vary according to the unit of analysis or how letter-sound combinations are represented to the student. For example, in synthetic phonics approaches, students are taught to link an individual letter or letter combination with its appropriate sound and then blend the sounds to form words. In analytic phonics, students are first taught whole word units followed by systematic instruction linking the specific letters in the word with their respective sounds.

Phonics instruction can also vary with respect to the explicitness by which the phonic elements are taught and practiced in the reading of text. For example, many synthetic phonics approaches use direct instruction in teaching phonics components and provide opportunities for applying these skills in decodable text formats characterized by a controlled vocabulary. On the other hand, embedded phonics approaches are typically less explicit and use decodable text for practice less frequently, although the phonics concepts to be learned can still be presented systematically.

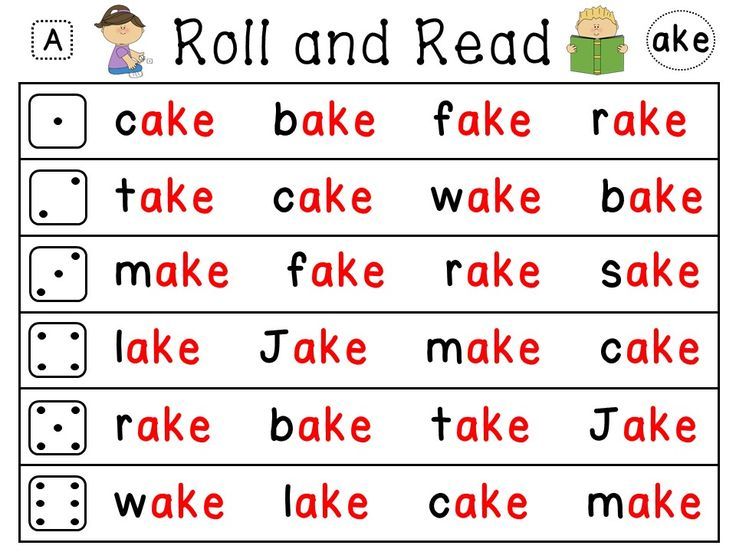

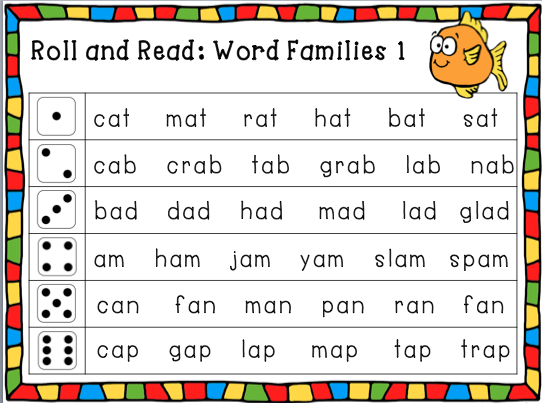

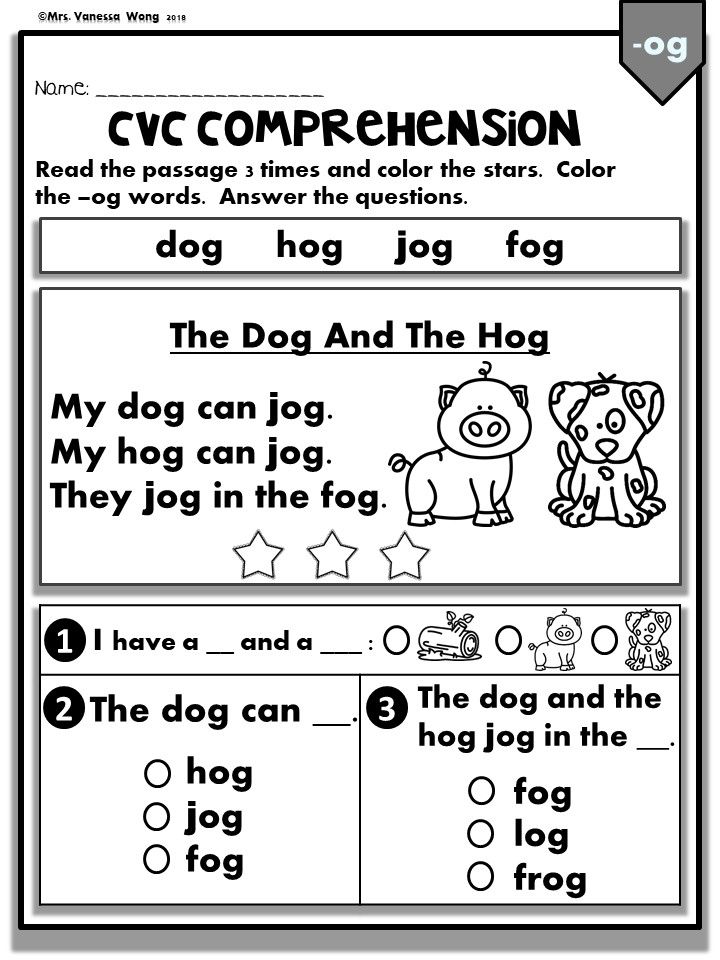

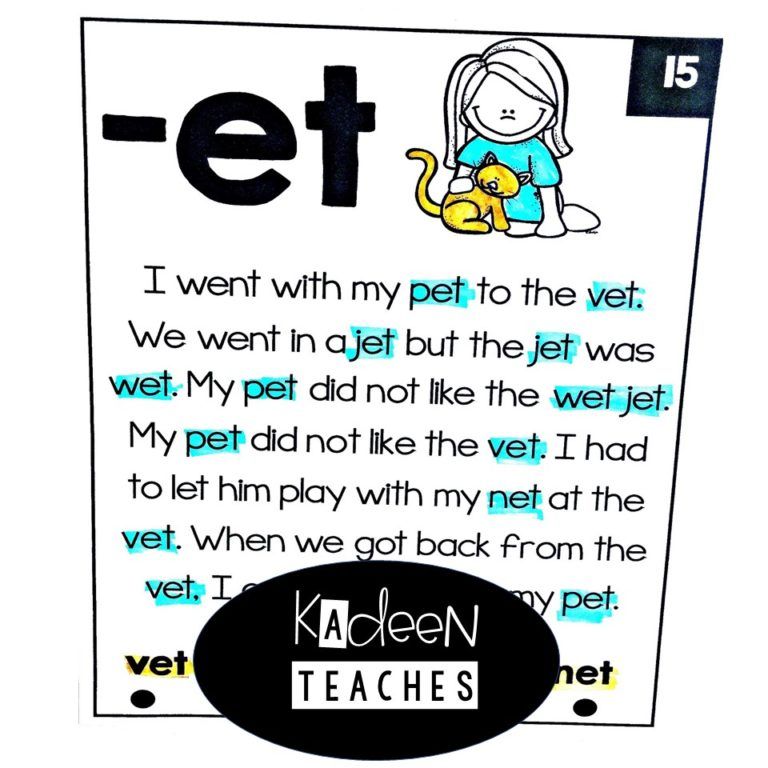

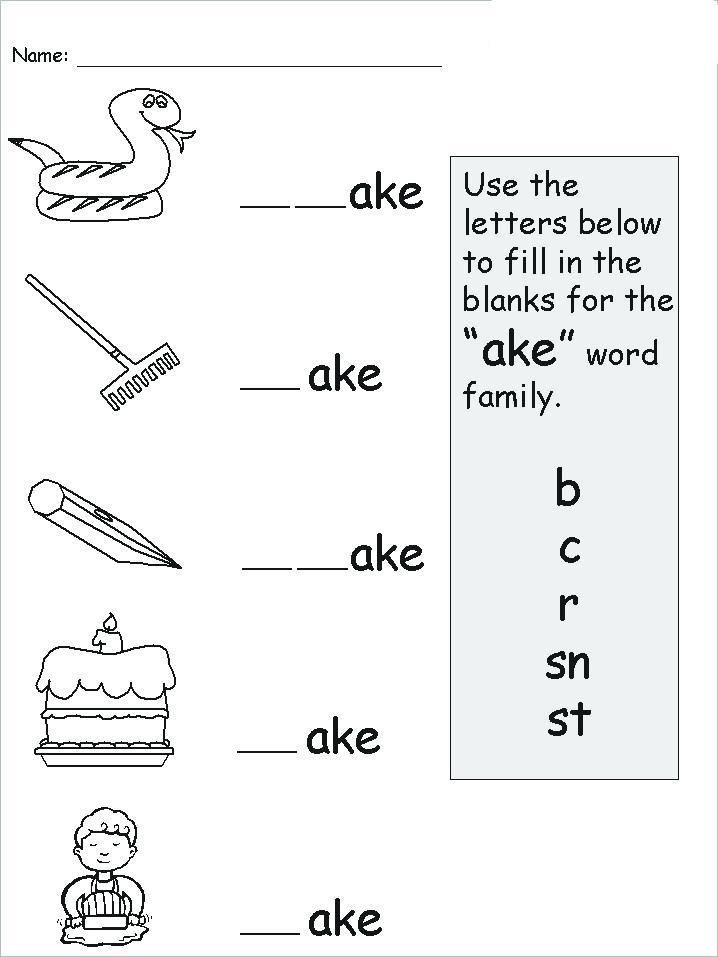

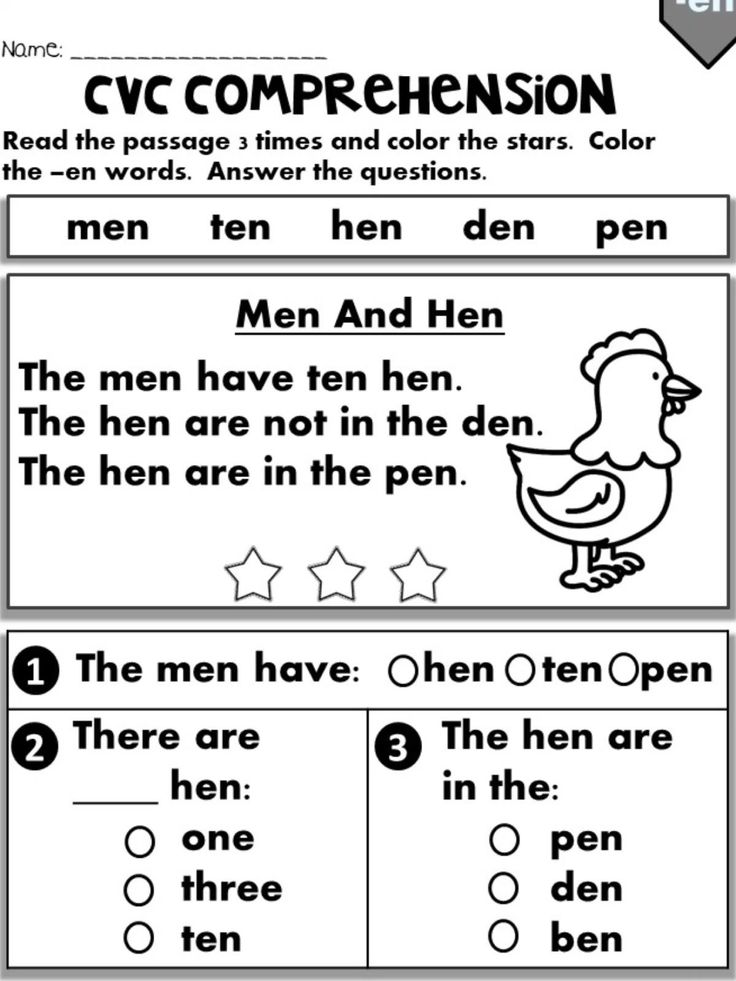

- Analogy phonics

Teaching students unfamiliar words by analogy to known words (e.

g., recognizing that the rime segment of an unfamiliar word is identical to that of a familiar word, and then blending the known rime with the new word onset, such as reading

brick by recognizing that -ick is contained in the known word kick, or reading stump by analogy to jump).

g., recognizing that the rime segment of an unfamiliar word is identical to that of a familiar word, and then blending the known rime with the new word onset, such as reading

brick by recognizing that -ick is contained in the known word kick, or reading stump by analogy to jump). - Analytic phonics

Teaching students to analyze letter-sound relations in previously learned words to avoid pronouncing sounds in isolation.

- Embedded phonics

Teaching students phonics skills by embedding phonics instruction in text reading, a more implicit approach that relies to some extent on incidental learning.

- Phonics through spelling

Teaching students to segment words into phonemes and to select letters for those phonemes (i.e., teaching students to spell words phonemically).

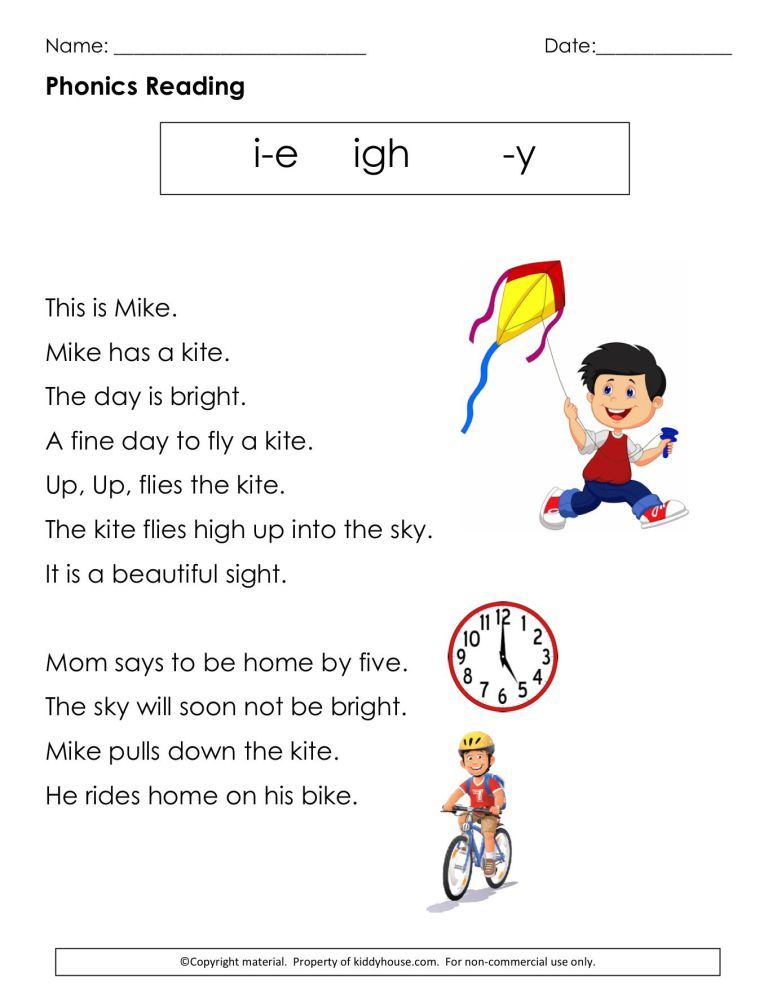

- Synthetic phonics

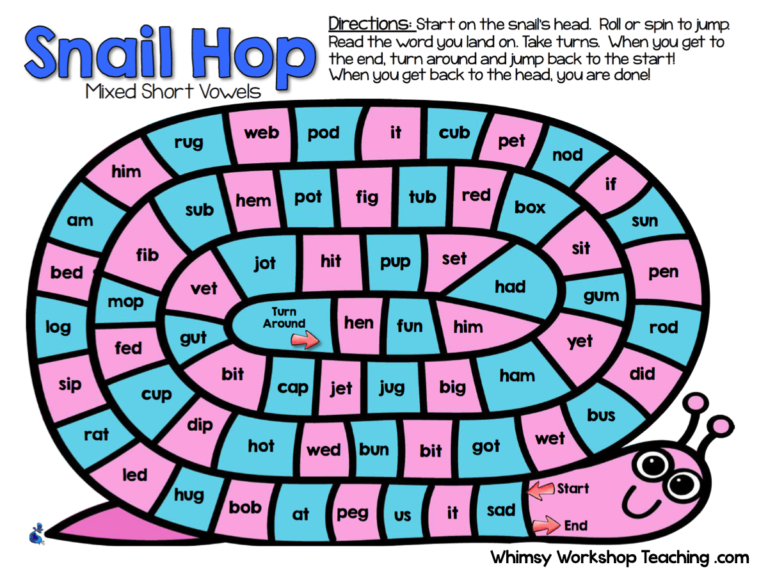

Teaching students explicitly to convert letters into sounds (phonemes) and then blend the sounds to form recognizable words.

Findings and determinations

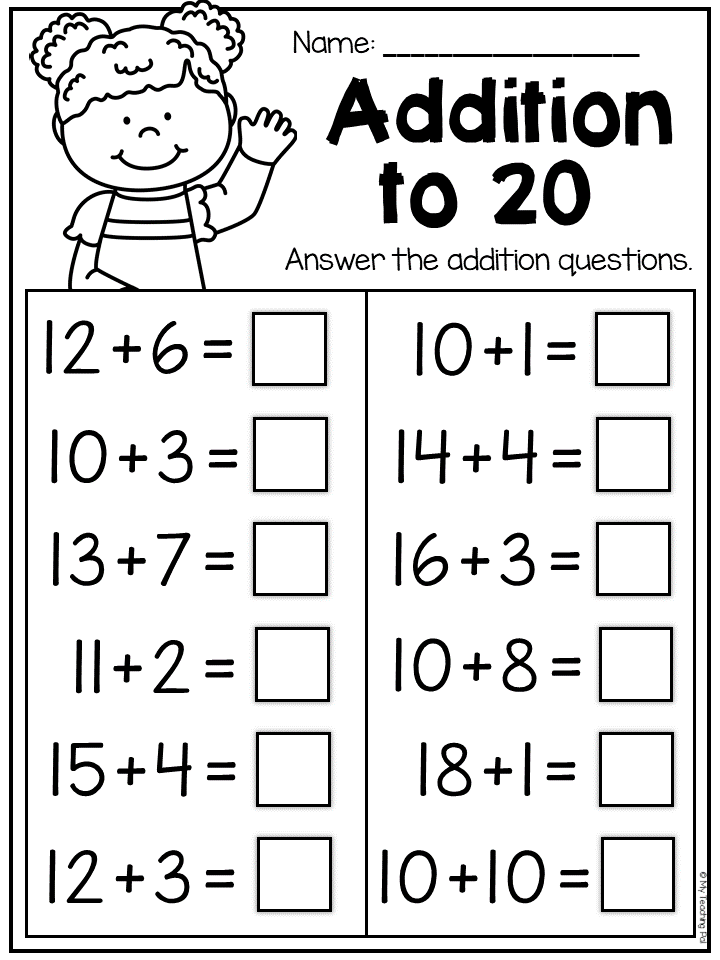

The meta-analysis revealed that systematic phonics instruction produces significant benefits for students in kindergarten through 6th grade and for children having difficulty learning to read. The ability to read and spell words was enhanced in kindergartners who received systematic beginning phonics instruction. First graders who were taught phonics systematically were better able to decode and spell, and they showed significant improvement in their ability to comprehend text. Older children receiving phonics instruction were better able to decode and spell words and to read text orally, but their comprehension of text was not significantly improved.

Systematic synthetic phonics instruction (see table for definition) had a positive and significant effect on disabled readers' reading skills. These children improved substantially in their ability to read words and showed significant, albeit small, gains in their ability to process text as a result of systematic synthetic phonics instruction. This type of phonics instruction benefits both students with learning disabilities and low-achieving students who are not disabled. Moreover, systematic synthetic phonics instruction was significantly more effective in improving low socioeconomic status (SES) children's alphabetic knowledge and word reading skills than instructional approaches that were less focused on these initial reading skills.

This type of phonics instruction benefits both students with learning disabilities and low-achieving students who are not disabled. Moreover, systematic synthetic phonics instruction was significantly more effective in improving low socioeconomic status (SES) children's alphabetic knowledge and word reading skills than instructional approaches that were less focused on these initial reading skills.

Across all grade levels, systematic phonics instruction improved the ability of good readers to spell. The impact was strongest for kindergartners and decreased in later grades. For poor readers, the impact of phonics instruction on spelling was small, perhaps reflecting the consistent finding that disabled readers have trouble learning to spell.

Although conventional wisdom has suggested that kindergarten students might not be ready for phonics instruction, this assumption was not supported by the data. The effects of systematic early phonics instruction were significant and substantial in kindergarten and the 1st grade, indicating that systematic phonics programs should be implemented at those age and grade levels.

The NRP analysis indicated that systematic phonics instruction is ready for implementation in the classroom. Findings of the Panel regarding the effectiveness of explicit, systematic phonics instruction were derived from studies conducted in many classrooms with typical classroom teachers and typical American or English-speaking students from a variety of backgrounds and socioeconomic levels.

Thus, the results of the analysis are indicative of what can be accomplished when explicit, systematic phonics programs are implemented in today's classrooms. Systematic phonics instruction has been used widely over a long period of time with positive results, and a variety of systematic phonics programs have proven effective with children of different ages, abilities, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Discussion

These facts and findings provide converging evidence that explicit, systematic phonics instruction is a valuable and essential part of a successful classroom reading program. However, there is a need to be cautious in giving a blanket endorsement of all kinds of phonics instruction.

However, there is a need to be cautious in giving a blanket endorsement of all kinds of phonics instruction.

It is important to recognize that the goals of phonics instruction are to provide children with key knowledge and skills and to ensure that they know how to apply that knowledge in their reading and writing. In other words, phonics teaching is a means to an end.

To be able to make use of letter-sound information, children need phonemic awareness. That is, they need to be able to blend sounds together to decode words, and they need to break spoken words into their constituent sounds to write words. Programs that focus too much on the teaching of letter-sound relations and not enough on putting them to use are unlikely to be very effective.

In implementing systematic phonics instruction, educators must keep the end in mind and ensure that children understand the purpose of learning letter sounds and that they are able to apply these skills accurately and fluently in their daily reading and writing activities.

Of additional concern is the often-heard call for "intensive, systematic" phonics instruction. Usually the term "intensive" is not defined. How much is required to be considered intensive?

In addition, it is not clear how many months or years a phonics program should continue. If phonics has been systematically taught in kindergarten and 1st grade, should it continue to be emphasized in 2nd grade and beyond? How long should single instruction sessions last? How much ground should be covered in a program? Specifically, how many letter-sound relations should be taught, and how many different ways of using these relations to read and write words should be practiced for the benefits of phonics to be maximized? These questions remain for future research.

Another important area is the role of the teacher. Some phonics programs showing large effect sizes require teachers to follow a set of specific instructions provided by the publisher; while this may standardize the instructional sequence, it also may reduce teacher interest and motivation.

Thus, one concern is how to maintain consistency of instruction while still encouraging the unique contributions of teachers. Other programs require a sophisticated knowledge of spelling, structural linguistics, or word etymology. In view of the evidence showing the effectiveness of systematic phonics instruction, it is important to ensure that the issue of how best to prepare teachers to carry out this teaching effectively and creatively is given high priority.

Knowing that all phonics programs are not the same brings with it the implication that teachers must themselves be educated about how to evaluate different programs to determine which ones are based on strong evidence and how they can most effectively use these programs in their own classrooms. It is therefore important that teachers be provided with evidence-based preservice training and ongoing inservice training to select (or develop) and implement the most appropriate phonics instruction effectively.

A common question with any instructional program is whether "one size fits all. " Teachers may be able to use a particular program in the classroom but may find that it suits some students better than others. At all grade levels, but particularly in kindergarten and the early grades, children are known to vary greatly in the skills they bring to school. Some children will already know letter-sound correspondences, and some will even be able to decode words, while others will have little or no letter knowledge.

" Teachers may be able to use a particular program in the classroom but may find that it suits some students better than others. At all grade levels, but particularly in kindergarten and the early grades, children are known to vary greatly in the skills they bring to school. Some children will already know letter-sound correspondences, and some will even be able to decode words, while others will have little or no letter knowledge.

Teachers should be able to assess the needs of the individual students and tailor instruction to meet specific needs. However, it is more common for phonics programs to present a fixed sequence of lessons scheduled from the beginning to the end of the school year. In light of this, teachers need to be flexible in their phonics instruction in order to adapt it to individual student needs.

Children who have already developed phonics skills and can apply them appropriately in the reading process do not require the same level and intensity of phonics instruction provided to children at the initial phases of reading acquisition. Thus, it will also be critical to determine objectively the ways in which systematic phonics instruction can be optimally incorporated and integrated in complete and balanced programs of reading instruction. Part of this effort should be directed at preservice and inservice education to provide teachers with decision-making frameworks to guide their selection, integration, and implementation of phonics instruction within a complete reading program.

Thus, it will also be critical to determine objectively the ways in which systematic phonics instruction can be optimally incorporated and integrated in complete and balanced programs of reading instruction. Part of this effort should be directed at preservice and inservice education to provide teachers with decision-making frameworks to guide their selection, integration, and implementation of phonics instruction within a complete reading program.

Teachers must understand that systematic phonics instruction is only one component – albeit a necessary component – of a total reading program; systematic phonics instruction should be integrated with other reading instruction in phonemic awareness, fluency, and comprehension strategies to create a complete reading program.

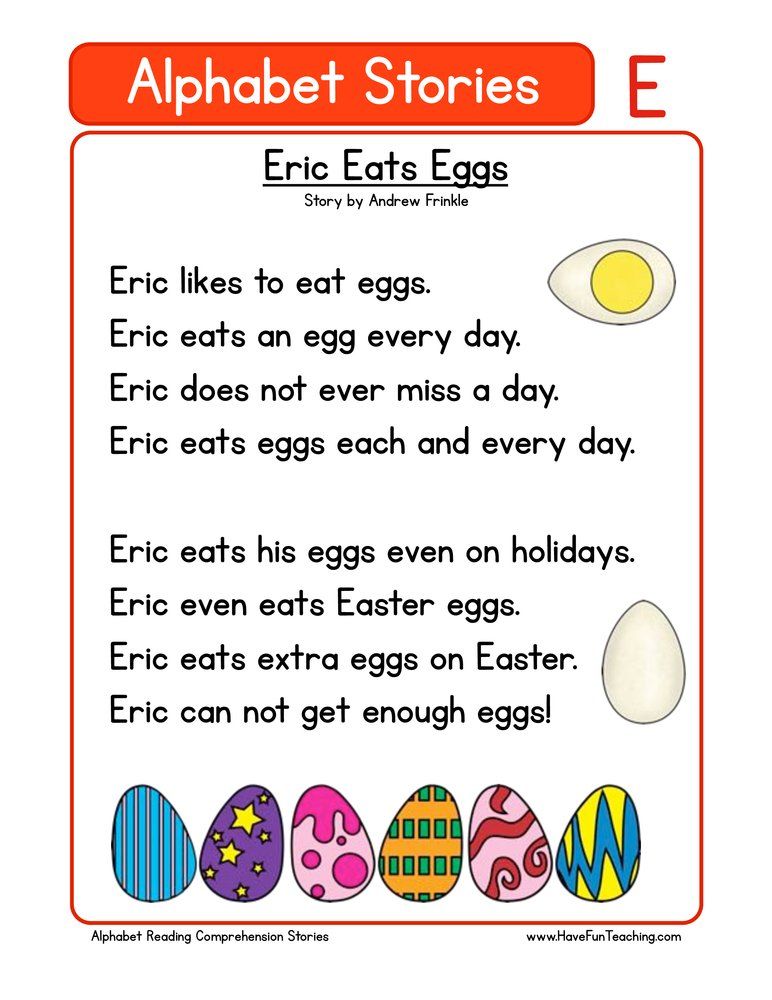

While most teachers and educational decision-makers recognize this, there may be a tendency in some classrooms, particularly in 1st grade, to allow phonics to become the dominant component, not only in the time devoted to it, but also in the significance attached. It is important not to judge children's reading competence solely on the basis of their phonics skills and not to devalue their interest in books because they cannot decode with complete accuracy. It is also critical for teachers to understand that systematic phonics instruction can be provided in an entertaining, vibrant, and creative manner.

It is important not to judge children's reading competence solely on the basis of their phonics skills and not to devalue their interest in books because they cannot decode with complete accuracy. It is also critical for teachers to understand that systematic phonics instruction can be provided in an entertaining, vibrant, and creative manner.

Systematic phonics instruction is designed to increase accuracy in decoding and word recognition skills, which in turn facilitate comprehension. However, it is again important to note that fluent and automatic application of phonics skills to text is another critical skill that must be taught and learned to maximize oral reading and reading comprehension. This issue again underscores the need for teachers to understand that while phonics skills are necessary in order to learn to read, they are not sufficient in their own right. Phonics skills must be integrated with the development of phonemic awareness, fluency, and text reading comprehension skills.

Explaining Phonics Instruction | Reading Rockets

By: International Literacy Association

This ILA brief explains the basics of phonics for parents, offering guidance on phonics for emerging readers, phonological awareness, word study, approaches to teaching phonics, and teaching English learners.

This 2018 brief explains the what, the when and the how of phonics instruction to parents, offering guidance on phonics for emerging readers, phonological awareness, word study, approaches to teaching phonics, and teaching English learners.

Key takeaways:

- Students should have acquired phonological awareness, concepts of print, concepts of word of text and alphabetic principles before beginning to learn phonics.

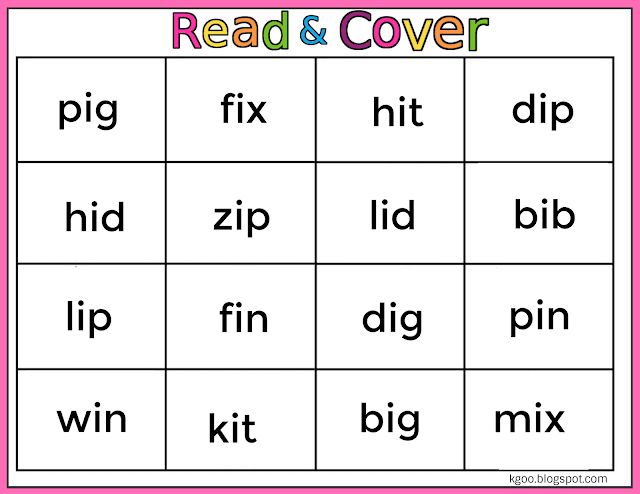

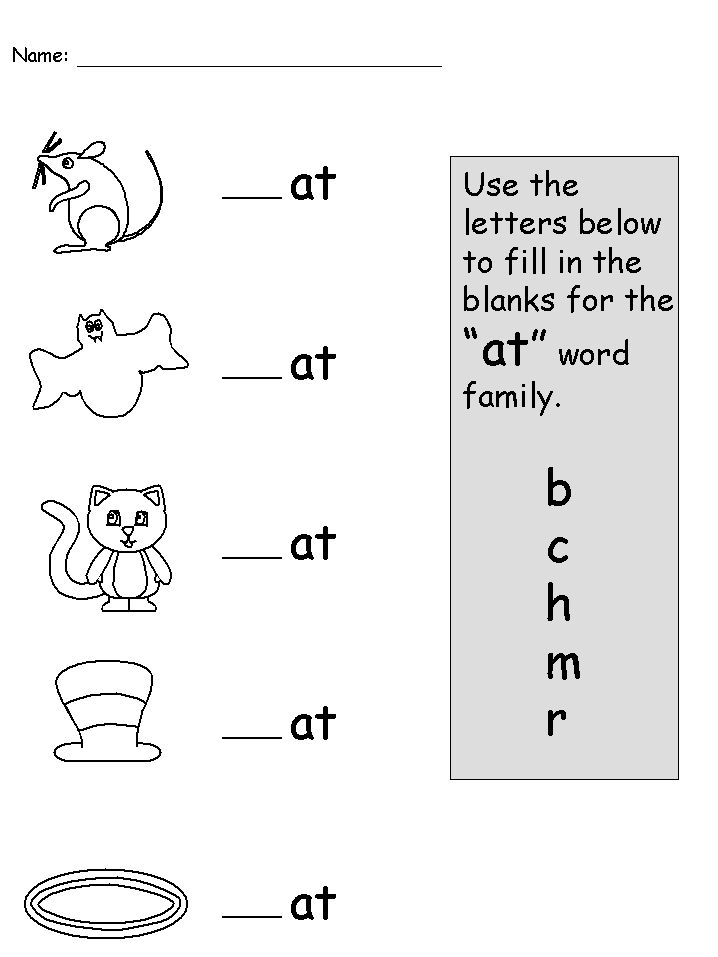

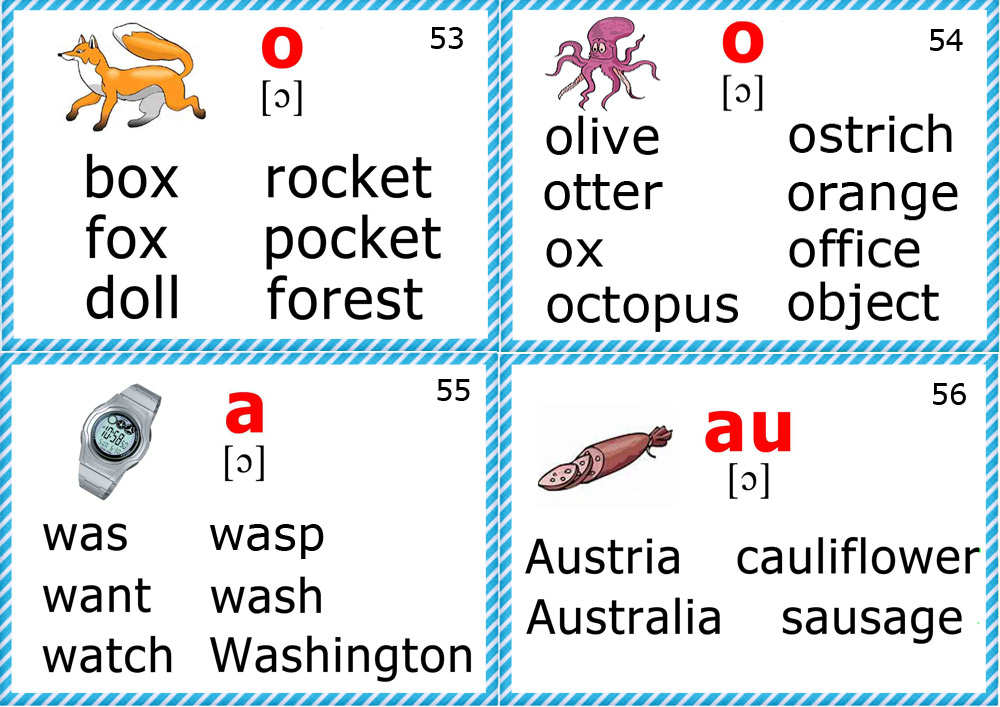

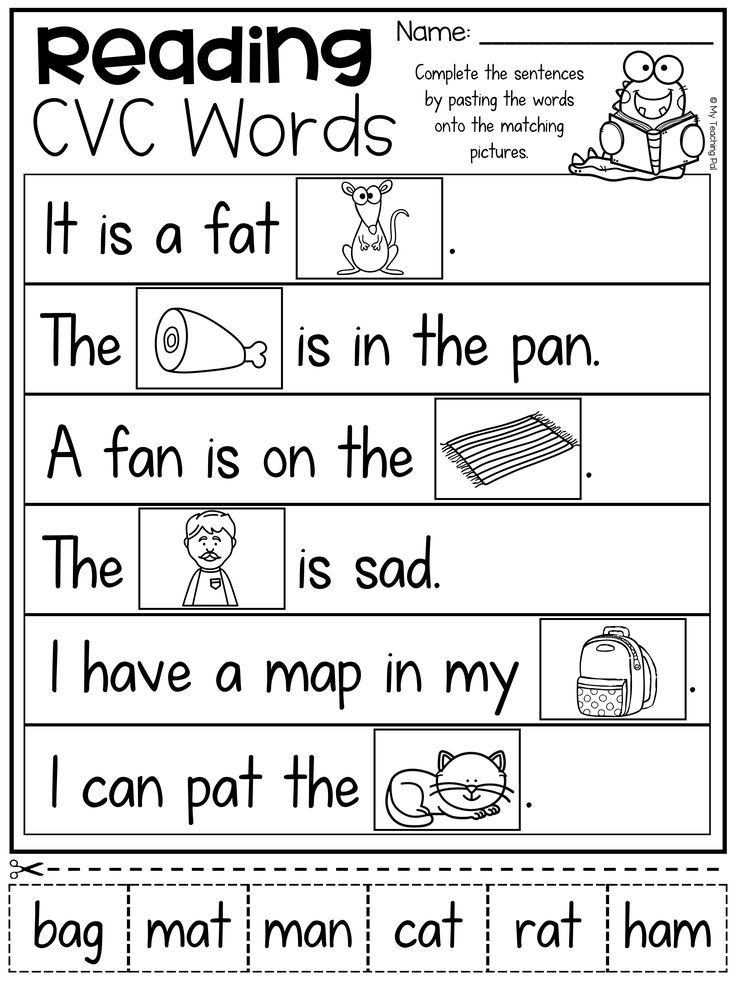

- Most phonics programs incorporate both analytic and synthetic activities. In analytic instruction, students compare words to identify patterns and apply this knowledge to new words (e.g., ran/can), or they examine word families to make analogies between segments of words (e.

g., onset and rime, r-an/c-an/f-an/m-an/p-an). In synthetic phonics, students blend individual letter sounds together to form words (e.g., c-a-t/cat).

g., onset and rime, r-an/c-an/f-an/m-an/p-an). In synthetic phonics, students blend individual letter sounds together to form words (e.g., c-a-t/cat). - Word study is an approach to teach the alphabetic layer (basic letter–sound correspondences) and pattern layer (consonant–vowel patterns) of the writing system by including spelling instruction that is differentiated by students’ development.

- Phonics instruction depends on the characteristics of a specific language; students who learn to read in multiple languages apply phonics that fit the respective letter–sound, pattern and meaning layers.

- Emergent bilingual readers and writers use their knowledge of one language to learn other languages.

See the full brief, Explaining Phonics Instruction: An Educator’s Guide.

International Literacy Association (2018)

Reprints

You are welcome to print copies for non-commercial use, or a limited number for educational purposes, as long as credit is given to Reading Rockets and the author(s). For commercial use, please contact the author or publisher listed.

For commercial use, please contact the author or publisher listed.

Related Topics

Early Literacy Development

Phonics and Decoding

Spelling and Word Study

New and Popular

Print-to-Speech and Speech-to-Print: Mapping Early Literacy

100 Children’s Authors and Illustrators Everyone Should Know

A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words

7 Great Ways to Encourage Your Child's Writing

Screening, Diagnosing, and Progress Monitoring for Fluency: The Details

Phonemic Activities for the Preschool or Elementary Classroom

Our Literacy Blogs

Shared Reading in the Structured Literacy Era

Kids and educational media

Meet Ali Kamanda and Jorge Redmond, authors of Black Boy, Black Boy: Celebrating the Power of You

Get Widget |

Subscribe

How Children Learn to Read - Psy-Pie

Evolving research shows that children need phonetics and general language education.

Even though it's summer break, many schools around the country are getting ready to get students back in the classroom, which means thinking seriously about the best ways to teach the youngest students to read.

Reading has been the holy grail of learning for centuries; you need to be able to read to learn about almost any other subject. nine0006

The two main theories of learning to read are phonetics and holistic language. Phonetics education focuses on developing reading skills from scratch by teaching children the sounds made by letters and how to put those letters together to form words. Language teaching in general emphasizes the meaning of what children read rather than the sounds that make up individual words; this encourages them to combine speaking, listening, reading and writing to understand the words on the page.

For decades, proponents of these two methods have argued about the best way to teach children to read, a debate often referred to as the "reading wars. " Over the past year, new systematic reviews have shed light on what is really being said about teaching children to read. nine0006

" Over the past year, new systematic reviews have shed light on what is really being said about teaching children to read. nine0006

The simple conclusion is that teaching children to read requires a combination of phonetics and holistic language learning. How it works?

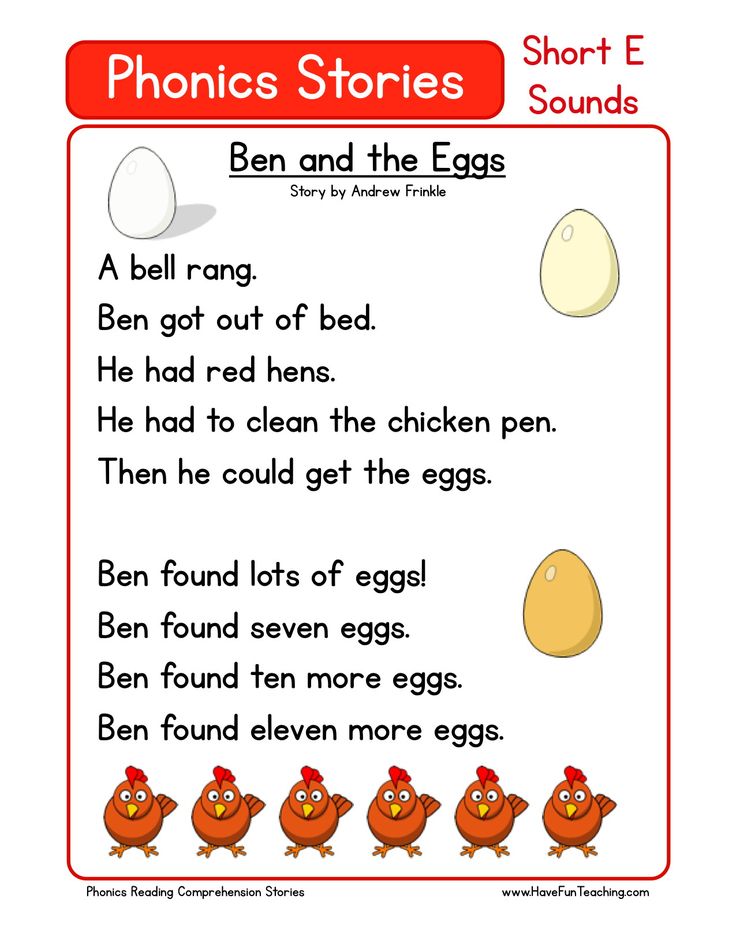

At the most basic levels of learning to read, children must learn that letters stand for sounds. This is where phonetics comes to the rescue. The most comprehensive review of phonetics research has come from the National Reading Commission, convened by the US Congress in the 1990s. The group conducted a systematic review of 38 studies comparing the success of systematic phonetics training with non-systematic or no phonetics training. They found that children who were systematically taught phonetics in kindergarten or first grade were significantly better at deciphering, writing, and understanding text. nine0006

There is also evidence that readers at all levels - even adults - use the skills learned through phonetics to read new words they have never seen before. Think of the popular Harry Potter books, which introduced a whole host of magical words such as "muggle" and "squib"; people of all ages read these words for the first time, saying them out loud.

Think of the popular Harry Potter books, which introduced a whole host of magical words such as "muggle" and "squib"; people of all ages read these words for the first time, saying them out loud.

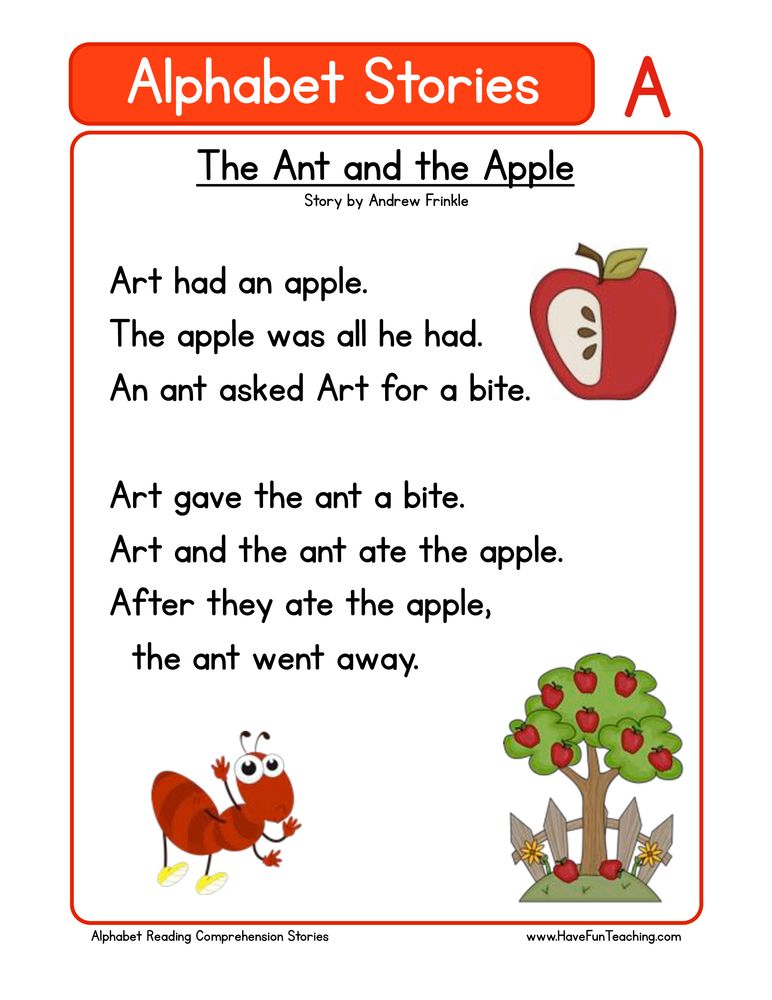

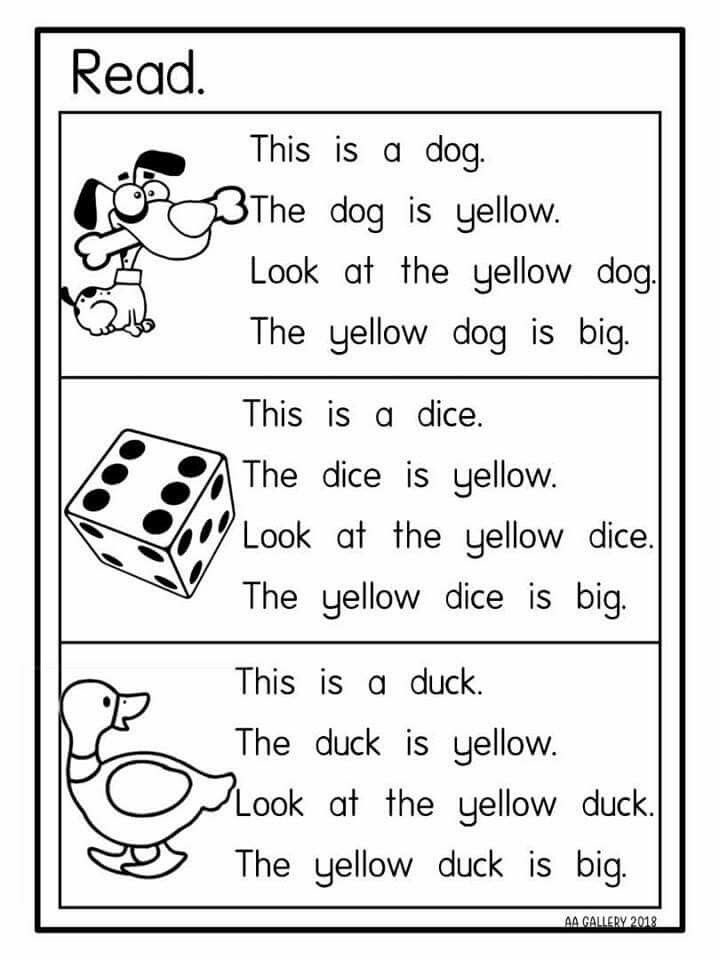

But studies show that learning to read cannot be limited to phonetics. In order to understand texts (which is the point of reading, after all), the reader cannot say every word aloud. They must learn to recognize words automatically so that they can quickly understand their meaning and move on to the next word. Evidence shows that this is a gradual transition where children start by saying most of the words out loud and then slowly move towards automatically recognizing and understanding more words. nine0006

In the transition to word recognition and comprehension, it helps if students have a wide vocabulary and if people read aloud to them, which allows them to understand more complex meanings than what they can read on their own. This is where holistic language learning comes into play. And as any teacher or parent will tell you, it's a big advantage if the student is interested in what they're reading!

And as any teacher or parent will tell you, it's a big advantage if the student is interested in what they're reading!

The more children know and understand the world, and the more words they learn, the better they will be able to understand what they read, and the less they will have to rely on phonetics to pronounce words. nine0006

Conclusion: novice readers need to study phonetics and pay attention to the meaning of the words they read. Evidence shows that this combined method of teaching children to read is the most effective.

Share the article

How to teach a child to read

For most adults, reading is a natural process in which it is not easy to single out the elements that make it up. Yet for most children, learning to read is a process that requires perseverance and effort. Remember how hard it was to learn to read? Pronounce the letter one by one, keeping their sequence in mind and trying to figure out what the word is, then read the next word in the same way. All efforts go into reading one single word, and when the child reads the next word, he often forgets the previous one. Try turning this article upside down and reading it. Hard? How much of what you read do you remember? Was it interesting to read this way? I doubt it's interesting. It is the same with a child: it is difficult to read, he remembers little of what he has read, and therefore it is not interesting to read. nine0045

All efforts go into reading one single word, and when the child reads the next word, he often forgets the previous one. Try turning this article upside down and reading it. Hard? How much of what you read do you remember? Was it interesting to read this way? I doubt it's interesting. It is the same with a child: it is difficult to read, he remembers little of what he has read, and therefore it is not interesting to read. nine0045

Knowing all this, many methodologists are trying to understand the mechanisms of reading, to come up with a method by which it would be easy to learn to read. Although many parents think that how quickly and well their child learns to read does not depend on how he is taught to read, but depends on intelligence, this is actually not the case. Two independent studies in the 1960s and 1970s showed that, in general, reading ability had little to do with IQ. More recent research has shown that children with reading difficulties often have above-average IQs. nine0006

nine0006

There is a belief that no matter how well a child learns to read by the first grade, he will learn later, with years the difficulties in reading will come to naught. This is not true. K. Stanovich showed that success in reading in the first grade largely determines the level of reading in the 11th grade. Good reading is all about practice, so those who are better at reading first tend to read more. Thus, over the years, the difference only increases. Learning to read well in the early years helps develop the important "habit" of reading for life. nine0006

Methods for teaching reading

The 20th century is far from the first to come up with new approaches to teaching reading. Every century, teaching methods are rediscovered, they say how good, natural and logical they are, then, when the fashion for a certain method passes, it is forgotten for several decades, later rediscovered.

Each of the methods invented in the 20th century, either in whole or in part, repeats well-forgotten old methods. But, as in the past, each of them is called "new", "natural", "correct" and "logical". nine0006

But, as in the past, each of them is called "new", "natural", "correct" and "logical". nine0006

Let's take a look at what reading programs currently exist and what results they lead to.

Phonetic method.

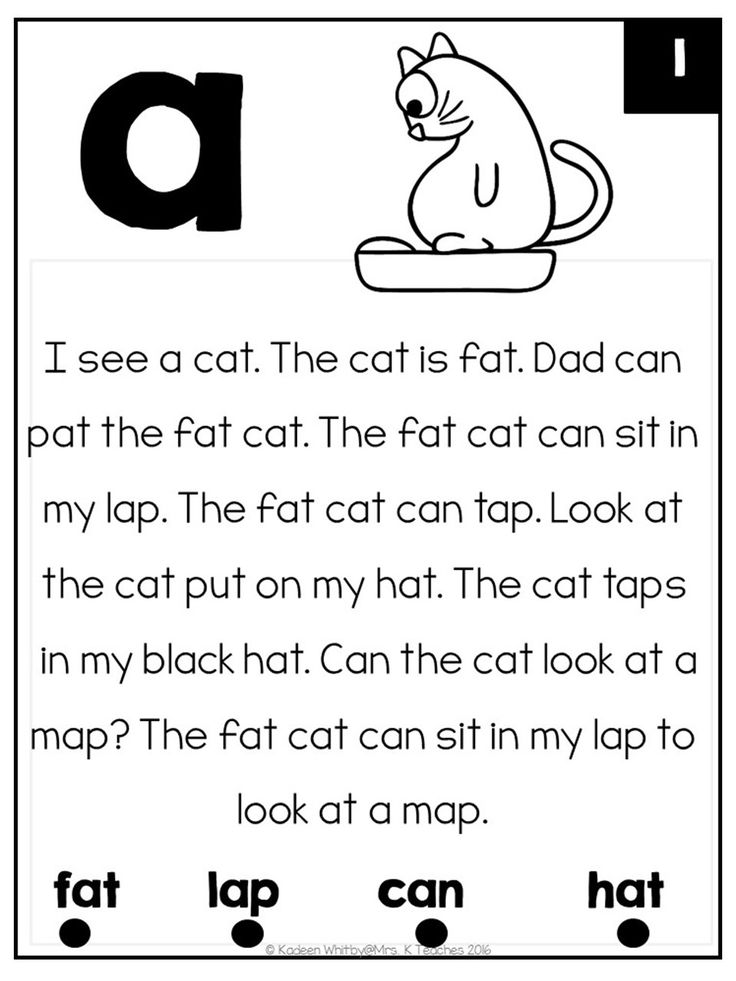

The phonetic approach consists of a system of learning to read, which is based on the alphabetical principle. It is a system whose central component is learning the relationships between letters or groups of letters and their pronunciation. It is based on teaching the pronunciation of letters and sounds (phonetics), and when the child accumulates sufficient knowledge, he proceeds first to syllables, then to whole words. nine0006

The phonetic method is divided into two branches:

1. Systematic-phonics are programs in which phonetics is systematically taught from the outset, usually (but not always) before whole words are read . The approach is most often based on synthesis: children are taught the sounds of letters and train them to combine these sounds. Sometimes these programs also include phonetic analysis - the ability to manipulate phonemes. Not all programs that are classified as "systematic-phonics" meet these criteria. However, they all emphasize the early and serious learning of letter sounds. nine0006

Not all programs that are classified as "systematic-phonics" meet these criteria. However, they all emphasize the early and serious learning of letter sounds. nine0006

2. Method of internal phonetics ("intrinsic-phonics") - these are programs in which emphasis is placed on visual and semantic reading, and in which phonetics is introduced later and in less quantity. Children enrolled in these programs learn the sounds of letters as they analyze familiar words. Another way of identifying words (by context or pattern) in these programs is given more attention than the analysis of the word. Usually there is no set time period for practicing phonetics. The effectiveness of this method in terms of the main parameters is lower than that of the method of systematic phonetics. nine0006

Various researchers have found a correlation between knowledge of letters and sounds and the ability to read. For both beginners and advanced readers, knowledge of letters and sensitivity to phonetic structure (the ability to distinguish phonemes) from spoken language is a good predictor of future reading success, even better than, for example, IQ level. Even for people who have long learned to read and read, but have difficulty reading, these difficulties are often associated with insufficient knowledge of letter-sound correspondences. However, the best phonological knowledge does not necessarily translate into a high level of reading. On the contrary, and not surprisingly, the level of reading in older people is increasingly correlated with the level of IQ. nine0006

Even for people who have long learned to read and read, but have difficulty reading, these difficulties are often associated with insufficient knowledge of letter-sound correspondences. However, the best phonological knowledge does not necessarily translate into a high level of reading. On the contrary, and not surprisingly, the level of reading in older people is increasingly correlated with the level of IQ. nine0006

Linguistic method

Linguistics is the science of the nature and structure of language. Now linguistics is used in the methods of teaching reading. Children come to school already with a large vocabulary, and this method suggests teaching them to read these words, especially those that are most commonly used. Bloomfield suggests learning to read first in words that are commonly used and that read as they are written. By reading words that read as they are written, the child learns to identify correspondences between letters and sounds. nine0006

Look-say

Another name for it is the whole-word method.

The method of "whole words" is that children are taught to recognize words as whole units, and do not explain the letter-sound relationships. Learning by this method is based on the principle of visual recognition of whole words. In this method, neither the names of the letters nor the letter-sound ratio are taught. In order to teach reading, the child was shown whole words and pronounced them, that is, they taught the child to recognize words as a whole, without dividing them into letters and syllables. After the child has learned about 50-100 words in this way, he is given texts in which these words are often found. nine0006

In Russia, this method is known as the Doman method - Glenn Doman builds all reading instruction only on it. This method was very popular in the 20s of the XX century. After the 30s, researchers have identified serious shortcomings of this method .

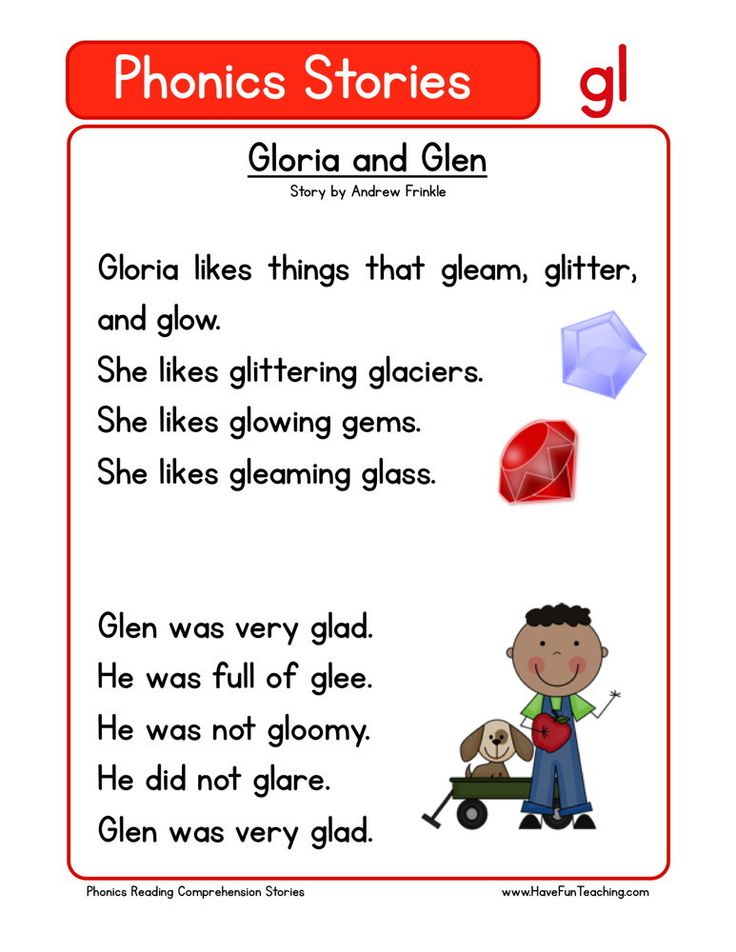

The whole-language method

In some ways, this method resembles the whole-word method, but relies more on the child's language experience. For example, children are given a book with a captivating storyline and have the children read it. Children read, encounter unfamiliar words, and children are encouraged to guess the meaning of these words with the help of context or illustrations, but not through the pronunciation of these words aloud. In order to stimulate the love of reading, children are encouraged to write stories. nine0006

For example, children are given a book with a captivating storyline and have the children read it. Children read, encounter unfamiliar words, and children are encouraged to guess the meaning of these words with the help of context or illustrations, but not through the pronunciation of these words aloud. In order to stimulate the love of reading, children are encouraged to write stories. nine0006

One of the goals of the whole-language approach is to make reading enjoyable. One of the salient features of this method is that phonetic rules do not have to be explained to learners to read. The relationship between letters and sounds is learned through the process of reading, in an implicit way. If a child reads a word incorrectly, they do not correct it. The philosophical view of this doctrine is that learning to read, as well as mastering a spoken language, is a natural process and children are able to comprehend it themselves.

Zaitsev Method

As a unit of the structure of the language, Zaitsev defined the warehouse. A warehouse is a pair of a consonant with a vowel, or a consonant with a hard or soft sign, or one letter. Zaitsev wrote these warehouses on the faces of the cubes. He made the cubes different in color, size, and the sound they make. This helps children feel the difference between vowels and consonants, voiced and soft. Using these warehouses (each warehouse is on a separate face of the cube), the child begins to compose words.

A warehouse is a pair of a consonant with a vowel, or a consonant with a hard or soft sign, or one letter. Zaitsev wrote these warehouses on the faces of the cubes. He made the cubes different in color, size, and the sound they make. This helps children feel the difference between vowels and consonants, voiced and soft. Using these warehouses (each warehouse is on a separate face of the cube), the child begins to compose words.

This technique can be attributed to phonetic methods: a warehouse is nothing more than a phoneme (with the exception of two warehouses: "b" and "b"). Thus, Zaitsev's technique teaches to read immediately by phonemes, and at the same time explains the letter-sound correspondence - not only combinations of consonants and vowels are written on the faces of the cubes, but also the letters themselves. nine0006

English Primary Reading Alphabet (ITA)

James Pitman expanded the English alphabet to 44 letters so that each letter is only pronounced one way, that is, all words are read as they are written. Capital letters in this expanded alphabet are written in the same way as small letters, only in a larger font. As the child mastered reading, the letters were replaced by ordinary ones.

Capital letters in this expanded alphabet are written in the same way as small letters, only in a larger font. As the child mastered reading, the letters were replaced by ordinary ones.

Moore's Method

The basis of learning is an interactive environment. Moore begins by teaching the child letters and sounds. He takes the child into a laboratory where there is a special typewriter that makes sounds or names of characters when you press them. So the child learns the names of letters and symbols (punctuation marks and numbers). The next step is for the child to be shown a series of letters or symbols on a screen, and he types them on the same typewriter, and the typewriter pronounces these series, for example, short simple words. Further, Moore asks to write, read and print words and sentences. His program also includes speaking, listening and writing from dictation. nine0006

The Montessori Method

Montessori gave children the letters of the alphabet and taught them to identify, write and pronounce them. Later, when the children learned to put sounds into words, she taught them to put words into meaningful sentences.

Later, when the children learned to put sounds into words, she taught them to put words into meaningful sentences.

Look-say or phonics method?

Of all the methods for teaching reading, two are the most well-known - the "look-say" method and the "phonics" method. These are two global and fundamentally opposite methods of teaching reading. Let's see which method is more effective for teaching reading. nine0006

Before 1930, there were eight studies aimed at understanding whether phonetics should be taught at all. As a result of research, the need to teach phonetics became obvious. After 1930, researchers were already conducting experiments to understand how and in what quantity phonetics should be taught.

An experiment was set up to compare the look-say method with the phonological method. For the experiment, we took a group of children enrolled in the first grade (5-6 years old) and still not able to read. The group was divided in half and one subgroup was taught to read using the "look-say" method, the other - using the phonological method. When the children began to read, they were tested. It turned out that in the beginning, children who were taught using the look-say method read faster and better understood what was read to themselves and read aloud fluently and with expression. Children who were taught to read using the phonological method were better at reading unfamiliar words, both at the beginning of learning and at any time thereafter. By the second grade, towards the end of learning to read, it turned out that the "phonological" children caught up and overtook their classmates and read better to themselves, better read comprehension and had a larger vocabulary than children taught to read using the "look-say" method. nine0006

When the children began to read, they were tested. It turned out that in the beginning, children who were taught using the look-say method read faster and better understood what was read to themselves and read aloud fluently and with expression. Children who were taught to read using the phonological method were better at reading unfamiliar words, both at the beginning of learning and at any time thereafter. By the second grade, towards the end of learning to read, it turned out that the "phonological" children caught up and overtook their classmates and read better to themselves, better read comprehension and had a larger vocabulary than children taught to read using the "look-say" method. nine0006

In the 1980s, Seymour and Elder observed first graders learning with the whole word method. The researchers paid particular attention to what mistakes students made. In one of the tasks, children were shown cards with signed pictures and asked to read the captions to the pictures. Often children read a word that was close in meaning, but completely distant in structure. For example, "lion" instead of "tiger", "girl" instead of "children" and "wheels" instead of "car". The researchers concluded that these children paid little attention to the letter-sound relationship: the children associated the word with a certain meaning, but not always accurately. For the whole year of training, the children never learned to read new words without someone's help. nine0006

For example, "lion" instead of "tiger", "girl" instead of "children" and "wheels" instead of "car". The researchers concluded that these children paid little attention to the letter-sound relationship: the children associated the word with a certain meaning, but not always accurately. For the whole year of training, the children never learned to read new words without someone's help. nine0006

Also, children learning using the "whole words" method had great difficulty reading words in which letters are written in different scripts (RoBiN), and "phonological" children experienced great difficulty reading words in which the sequence of letters was changed (flower) or some letters are replaced with similar, but different ones (tslsvisor).

It is possible that some children can learn the rules of phonics on their own, but most need explicit phonics instruction or their reading skills will suffer. This conclusion is based in part on knowing how good readers perceive a word on a page. One of the first researchers of this issue, James Cattell, showed that if people are shown words or a series of letters for a short time, then the words are perceived better. Therefore, it seems that people do not spell words. New studies have provided more precise knowledge about this phenomenon. For example, studies of eye movement while reading show that although people notice each letter as a separate character, they usually perceive all the letters in a word at the same time. nine0006

One of the first researchers of this issue, James Cattell, showed that if people are shown words or a series of letters for a short time, then the words are perceived better. Therefore, it seems that people do not spell words. New studies have provided more precise knowledge about this phenomenon. For example, studies of eye movement while reading show that although people notice each letter as a separate character, they usually perceive all the letters in a word at the same time. nine0006

It took longer to answer the question: “Do people who read well read the text to themselves?”. Whole-language proponents have argued for over 20 years that people often perceive the meaning of words from a text directly, without being spoken. Some psychologists still hold this view, but most of them think that reading is the process of saying a text to oneself, even for people who read well.

The most convincing evidence for this last assertion comes from the ingenious experiments of Guy Van Orden: when the subject is first asked, for example, "Is this a flower?", and then shown a word, for example, "lily", and asked if this word belongs to this category . Sometimes the subject was presented with a word that sounded like a suitable answer, such as "lily", and in fact the subjects often identified these words as the appropriate category, and these incorrect answers show that the reader actually transforms sequences of characters into sequences of sounds, which he then uses to understand the meaning. nine0006

Sometimes the subject was presented with a word that sounded like a suitable answer, such as "lily", and in fact the subjects often identified these words as the appropriate category, and these incorrect answers show that the reader actually transforms sequences of characters into sequences of sounds, which he then uses to understand the meaning. nine0006

Recent brain research has shown that even in people who read well, the same areas of the motor cortex are activated during silent reading as when reading aloud. There are other experimental confirmations that reading is a quick pronunciation to oneself. For example, when teaching English-speaking students to read Arabic, the group that was explicitly taught letter-to-sound correspondences was much more successful at reading new words than the group that was taught using the "whole-word" method. nine0006

Laboratory studies have shown that the most important factor in becoming fluent in reading is the ability to recognize letters, pronunciation patterns, and whole words easily, automatically, and visually. Therefore, knowledge of letters and phonological skills is one of the most important for the development of the ability to read.

Therefore, knowledge of letters and phonological skills is one of the most important for the development of the ability to read.

From all of the above it follows that all learning must be based on a solid understanding of letters and sounds. Even a student-specific approach, one that makes reading really interesting, is less effective than phonetics cramming. nine0006

Is the alphabet really necessary?

Of course, you can say that everyone knows that a child needs to know letters before he can start reading words. But, oddly enough, you can learn to read without knowing the letters of the alphabet. Followers of the "whole-word" method urge either not to teach the child letters at all, or to teach them letters only after they can read about 100 words on their own.

A lot of research has been done and it turns out that letter knowledge is a very good predictor of a child's rapid progress in reading. And knowing the letters is a stronger predictor than IQ. Children's ability to make letter sounds before learning to read also predicts early reading success. nine0006

nine0006

When children first begin to read, the correlation between knowledge of letters and/or knowledge of phonetics and their ability to read is very high. Whatever level is tested - from kindergarten to college - proficiency in letters and/or proficiency in phonetics is positively associated with reading ability (as measured by oral word recognition associated with reading aloud, reading comprehension silently, or reading speed) and, of course, with the ability to spell words.

What happens if you teach children to read without teaching them the alphabet? nine0006

Willows, Borwick, Haveren conducted such an experiment. They taught children to read by presenting cards with words. The children were divided into two groups: the first group was shown cards containing a picture and a word, the second group was presented with cards containing only a word. Each group was taught the same four words. When the groups learned these four words, that is, they correctly called the words from the cards, both groups were connected together. The researchers mixed word cards and showed the connected group both word cards with pictures and cards containing only words. It turned out that those children who were taught to read from cards with pictures read words better on cards with pictures and worse - the same words, but on cards without pictures, compared to those children who were taught from cards without pictures. Children who were taught to read with word cards but no pictures were better at reading words on cards without pictures than children who were taught with picture cards but were worse at reading words on picture cards. nine0006

The researchers mixed word cards and showed the connected group both word cards with pictures and cards containing only words. It turned out that those children who were taught to read from cards with pictures read words better on cards with pictures and worse - the same words, but on cards without pictures, compared to those children who were taught from cards without pictures. Children who were taught to read with word cards but no pictures were better at reading words on cards without pictures than children who were taught with picture cards but were worse at reading words on picture cards. nine0006

It turns out that the reverse side of the usefulness of pictures is a decrease in attention to the printed text (letters). Thus, if we see the goal in helping the child to react to an unfamiliar word (to see its image), then the pictures help, but if the goal is to draw the child's attention directly to the spelling of the word, then the pictures interfere.

So now we are ready to answer the question: Is an alphabet necessary? - Answer: yes, it is necessary.

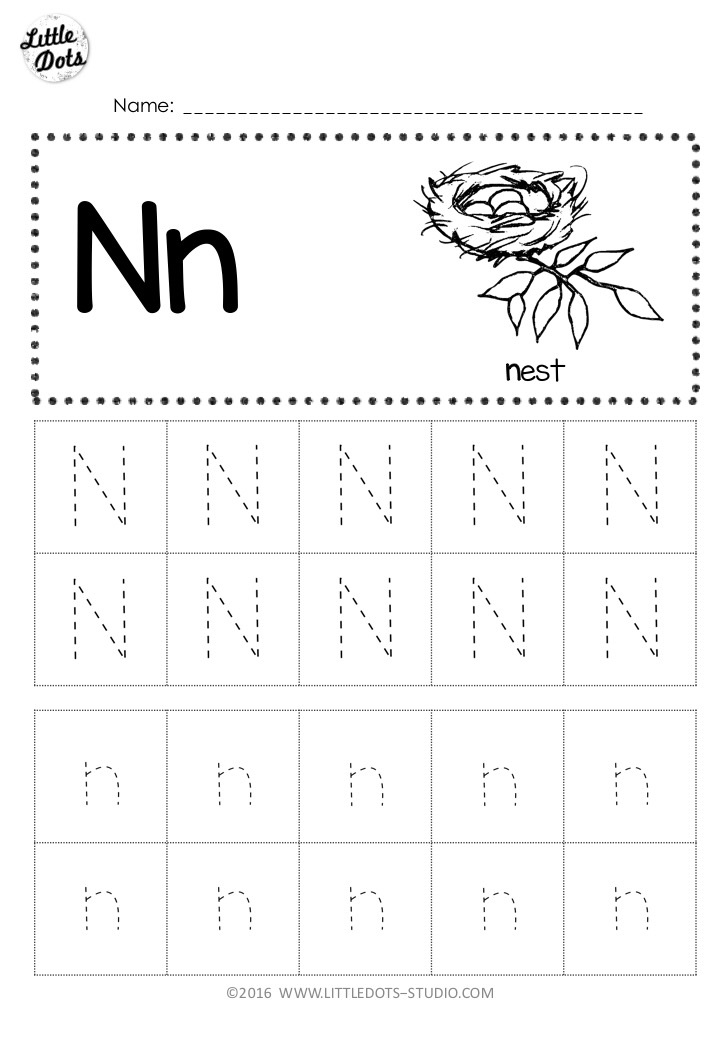

The main idea of learning the alphabet is not that children should know all the letters, but that children should pay attention to the letters. Knowing the letters and knowing their sounds helps pay attention to printed text. It is known that interest in letters in young children is positively associated with reading success. However, with age, the importance of letters and sounds for reading changes: in primary school, knowledge of letters and sounds is more important than education and good oral speech, and in high school, the level of readable texts already requires higher intellectual and linguistic abilities of the student (with good knowledge of the alphabet). and correspondence of letters to sounds). nine0006

Knowledge of the alphabet, an interest in letters, is the next step in a child's development, because the alphabet is an abstract code, unlike real objects that the child has dealt with before. The child begins to use the symbolic representation of information, which is a higher form of mental activity. It is possible that the early introduction of the alphabet will stimulate the development of abstract thinking, so necessary in our scientific automated world.

It is possible that the early introduction of the alphabet will stimulate the development of abstract thinking, so necessary in our scientific automated world.

Is there a way to teach reading that is appropriate for all languages? nine0045 The structures of different languages differ from each other, some more, some less. And the method of teaching reading should be tailored to the characteristics of the structure of the language in which we teach reading. It follows from this that there cannot be one universal methodology for teaching reading in any language, but there may be a most suitable methodology that covers various aspects of the linguistics of a particular language. Only the approach to learning can be common: it is now clear that any learning should be based on a solid understanding of letters and sounds, but the methods by which phonetics is given should be different for each language. nine0006

The "look-say" method is based on the fact that children are taught words as whole units, and when children have learned about 50-100 words, they are given texts in which these words often occur. It seems that this method would be best suited for teaching Chinese to read, but for the past 50 years in China, children have been taught to read words first using the Roman alphabet, and only then using Chinese characters. Similarly, children from most many other language groups are first taught the relationship between letters and the sounds associated with them (phonemes). nine0006

It seems that this method would be best suited for teaching Chinese to read, but for the past 50 years in China, children have been taught to read words first using the Roman alphabet, and only then using Chinese characters. Similarly, children from most many other language groups are first taught the relationship between letters and the sounds associated with them (phonemes). nine0006

The relationship between letters and phonemes is not very simple in languages with many exceptions, such as English. Such exception words are not read the way they are written. Reading rules depend on whether the syllable is closed or open, on the order of the letters and on their combinations with each other. For example, the letter "b" is pronounced the same as in the word "bat". And the letter “e” at the end of the word is not pronounced, but lengthens the pronunciation of the previous vowel: “pave” “save” “gave”. Thus, in English, letters can be pronounced either as they are written, or they can not be pronounced themselves, but affect the pronunciation of other letters. This is why James Pitman's ITA alphabet used to be very popular in English, and the "whole-language" method is now very popular. At the same time, the Bush administration is considering a mandatory introduction of phonetics in the curriculum in all states of America. nine0006

This is why James Pitman's ITA alphabet used to be very popular in English, and the "whole-language" method is now very popular. At the same time, the Bush administration is considering a mandatory introduction of phonetics in the curriculum in all states of America. nine0006

The rules for reading in Russian are much simpler - words are read the way they are written, the only exceptions are those words that are not read the way they are written, only because of the "laziness" of the language: unstressed letters are pronounced the way it is more convenient for pronunciation, and in unstressed syllables, voiced consonants are stunned (milk -> malako, shelter -> krof) and some letters are not pronounced at all (sun -> sun). But even if we read the words according to the rules, the way they are written, this will not be considered a mistake and the meaning of the word will not change from this, as would happen in English. nine0006

A few decades ago, a technique was popular in Russia: to teach first the letters and their names, their sounds, then the merging of letters into syllables and reading by syllables. Often, for a long time, children could not learn the difference between the names of letters by the sounds themselves, the sound of the letters - they were knocked down by the names of the letters. In addition, the syllables are too long for initial reading, and it is difficult for the child to add letter to letter and keep it in his head to read the whole syllable. Perhaps it would be more effective to teach to read by phonemic warehouses, and not tell the child the names of letters, at least until he learns to read. There are not very many warehouses in Russian, and it is convenient to manipulate them when they are written on cubes. In addition, the alphabet, the letter-sound correspondence is also easy to learn if taught with the help of Zaitsev's cubes - the letters themselves are written on the faces of the cubes. Due to the very structure of the Russian language, due to the fact that almost all words are read the way they are written, the warehouse principle is very well suited for teaching reading.

Often, for a long time, children could not learn the difference between the names of letters by the sounds themselves, the sound of the letters - they were knocked down by the names of the letters. In addition, the syllables are too long for initial reading, and it is difficult for the child to add letter to letter and keep it in his head to read the whole syllable. Perhaps it would be more effective to teach to read by phonemic warehouses, and not tell the child the names of letters, at least until he learns to read. There are not very many warehouses in Russian, and it is convenient to manipulate them when they are written on cubes. In addition, the alphabet, the letter-sound correspondence is also easy to learn if taught with the help of Zaitsev's cubes - the letters themselves are written on the faces of the cubes. Due to the very structure of the Russian language, due to the fact that almost all words are read the way they are written, the warehouse principle is very well suited for teaching reading. nine0049

nine0049

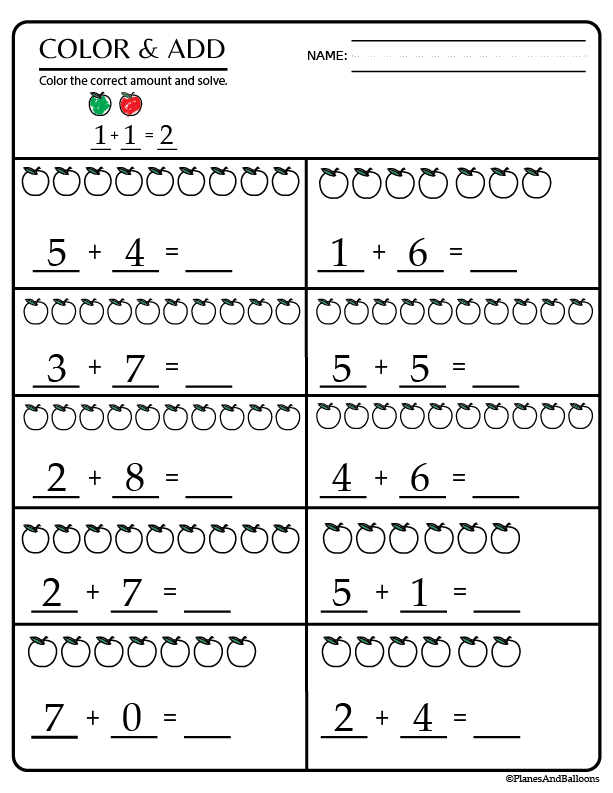

So, we found out that the main thing to teach a child if we want to teach him to read well is phonetics. But the comprehension of letter-sound correspondences is most often a rather boring task, and it is not at all easy to achieve quick success in it. If you teach reading only with the help of one phonetics, then this will most likely lead to a decrease in interest in the reading process in a child. And it is necessary to maintain interest in order not to instill in the child a rejection of reading, moreover, an interested person comprehends the subject of study several times faster than an uninterested one. In order for a child to believe in himself, and it would be interesting for him to learn to read - you need to give him an impulse, show that learning to read is an exciting activity. Interest in reading will be formed only if the child achieves success fairly quickly. For example, if you teach a child to recognize several dozen words, and this can easily be achieved with a good approach, this will bring joy and self-confidence to the child, and at the same time, he can slowly but surely teach phonetics. In order to teach a child to recognize several dozen words, you can sign various objects at home, hang signs under them or on them (table, wardrobe, sofa, stove, etc.). You can also play a “guessing game”: choose a dozen words and write words from this dozen with your child, ask the child to guess what is written. Such games are usually very popular with children. nine0006

In order to teach a child to recognize several dozen words, you can sign various objects at home, hang signs under them or on them (table, wardrobe, sofa, stove, etc.). You can also play a “guessing game”: choose a dozen words and write words from this dozen with your child, ask the child to guess what is written. Such games are usually very popular with children. nine0006

However, even the youngest children can be prepared to learn to read in later years: researchers have found that the most important activity for building the knowledge and skills that reading will eventually require is reading aloud to children. The greatest progress is made when the vocabulary and syntax of what is being read is always slightly higher than the child's own language level. To test this hypothesis, fifteen parents were selected, who were taught how to read correctly to children: actively involve the child in reading. During the reading, parents were asked to ask questions not for “yes or no”, but for more detailed answers. They were asked to pause more often, to leave unfinished thoughts, after listening to the child's answer, to offer alternative answers, to ask more and more difficult questions. After teaching the parents, they were asked to read to the child in this way for a month and record these readings on a tape recorder. At the same time, fifteen untrained parents were selected whose children were the same age as the children in the first group. They were also asked to tape their readings. A month later, both children were tested, and it turned out that children whose parents were trained surpassed their peers by 8.5 months on both the verbal expression of thoughts and the vocabulary test - and this is a huge difference for children of 30 months of age nine0049 .

They were asked to pause more often, to leave unfinished thoughts, after listening to the child's answer, to offer alternative answers, to ask more and more difficult questions. After teaching the parents, they were asked to read to the child in this way for a month and record these readings on a tape recorder. At the same time, fifteen untrained parents were selected whose children were the same age as the children in the first group. They were also asked to tape their readings. A month later, both children were tested, and it turned out that children whose parents were trained surpassed their peers by 8.5 months on both the verbal expression of thoughts and the vocabulary test - and this is a huge difference for children of 30 months of age nine0049 .

There is no general methodology for learning to read in any language, but there are important elements that make up reading, and they must be mastered by anyone who wants to learn to read well. These elements turn out to be the same for all alphabetic languages - this is a sound-speech code, an alpha-sound correspondence.