Learn to read for 1st graders

First Grade Instruction | Reading Rockets

It is during first grade that most children define themselves as good or poor readers. Unfortunately, it is also in first grade where common instructional practices are arguably most inconsistent with the research findings. This gap is reflected in the basal programs most commonly used in first-grade classrooms. The National Academy of Sciences report found that the more neglected instructional components of basal series are among those whose importance is most strongly supported by the research.

In this discussion, there are again certain caveats to keep in mind:

There is no replacing passionate teachers who are keenly aware of how their students are learning; research will never be able to tell teachers exactly what to do for a given child on a given day. What research can tell teachers, and what teachers are hungry to know, is what the evidence shows will work most often with most children and what will help specific groups of children.

To integrate research-based instructional practices into their daily work, teachers need the following:

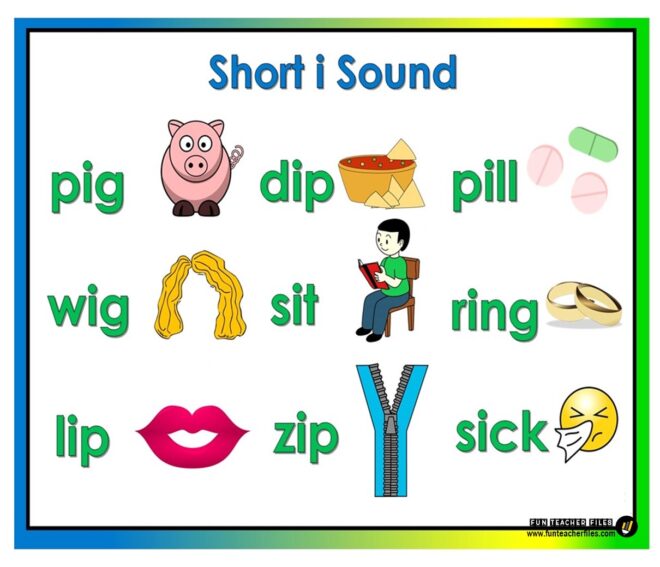

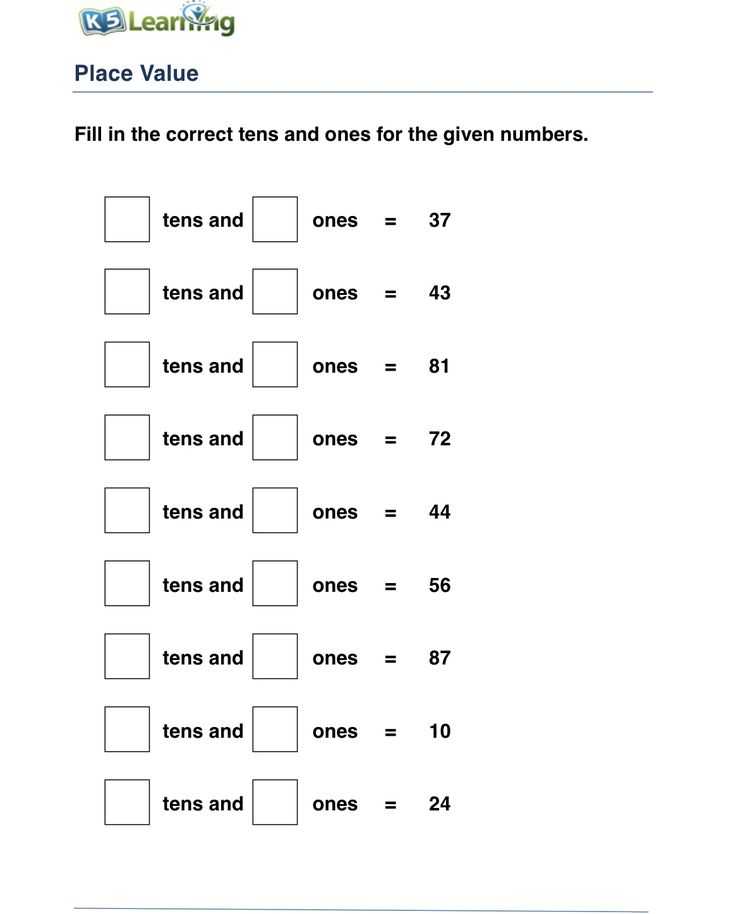

Training in alphabetic basics

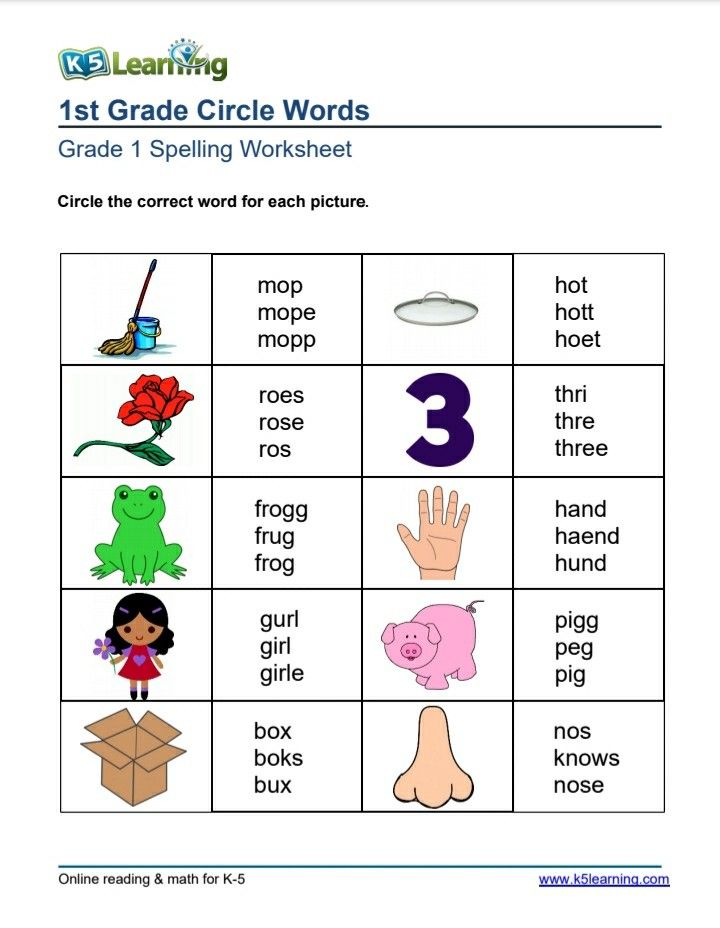

To read, children must know how to blend isolated sounds into words; to write, they must know how to break words into their component sounds. First-grade students who don't yet know their letters and sounds will need special catch-up instruction. In addition to such phonemic awareness, beginning readers must know their letters and have a basic understanding of how the letters of words, going from left to right, represent their sounds. First-grade classrooms must be designed to ensure that all children have a firm grasp of these basics before formal reading and spelling instruction begins.

A proper balance between phonics and meaning in their instruction

In recent years, most educators have come to advocate a balanced approach to early reading instruction, promising attention to basic skills and exposure to rich literature. However, classroom practices of teachers, schools, and districts using balanced approaches vary widely.

However, classroom practices of teachers, schools, and districts using balanced approaches vary widely.

Some teachers teach a little phonics on the side, perhaps using special materials for this purpose, while they primarily use basal reading programs that do not follow a strong sequence of phonics instruction. Others teach phonics in context, which means stopping from time to time during reading or writing instruction to point out, for example, a short a or an application of the silent e rule. These instructional strategies work with some children but are not consistent with evidence about how to help children, especially those who are most at risk, learn to read most effectively.

The National Academy of Sciences study, Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children, recommends first-grade instruction that provides explicit instruction and practice with sound structures that lead to familiarity with spelling-sound conventions and their use in identifying printed words. The bottom line is that all children have to learn to sound out words rather than relying on context and pictures as their primary strategies to determine meaning.

Does this mean that every child needs phonics instruction? Research shows that all proficient readers rely on deep and ready knowledge of spelling-sound correspondence while reading, whether this knowledge was specifically taught or simply inferred by students. Conversely, failure to learn to use spelling/sound correspondences to read and spell words is shown to be the most frequent and debilitating cause of reading difficulty. No one questions that many children do learn to read without any direct classroom instruction in phonics. But many children, especially children from homes that are not language rich or who potentially have learning disabilities, do need more systematic instruction in word-attack strategies.

Well-sequenced phonics instruction early in first grade has been shown to reduce the incidence of reading difficulty even as it accelerates the growth of the class as a whole. Given this, it is probably best to start all children, most especially in high-poverty areas, with explicit phonics instruction. Such an approach does require continually monitoring children's progress both to allow those who are progressing quickly to move ahead before they become bored and to ensure that those who are having difficulties get the assistance they need.

Such an approach does require continually monitoring children's progress both to allow those who are progressing quickly to move ahead before they become bored and to ensure that those who are having difficulties get the assistance they need.

Strong reading materials

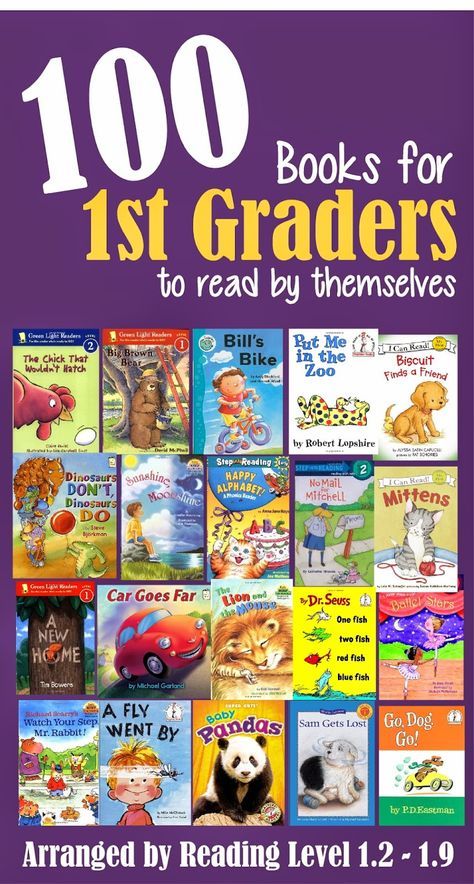

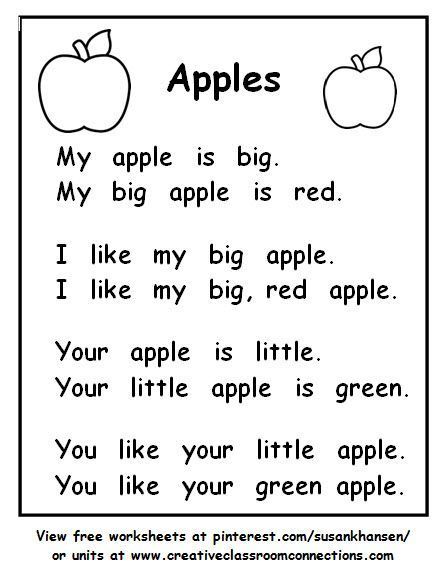

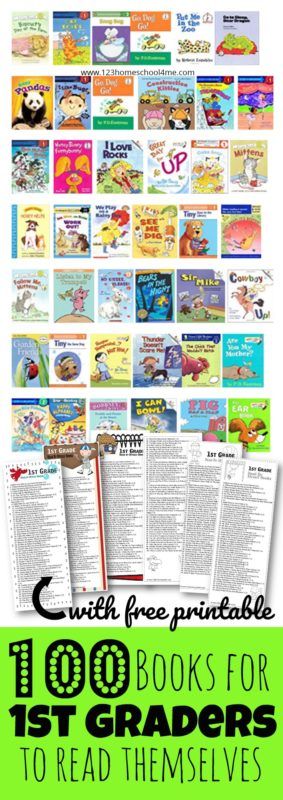

Early in first grade, a child's reading materials should feature a high proportion of new words that use the letter-sound relationships they have been taught. It makes no sense to teach decoding strategies and then have children read materials in which these strategies won't work. While research does not specify the exact percentage of words children should be able to recognize or sound out, it is clear that most children will learn to read more effectively with books in which this percentage is high.

On this point, the National Academy of Sciences report recommends that students should read well-written and engaging texts that include words that children can decipher to give them the chance to apply their emerging skills. It further recommends that children practice reading independently with texts slightly below their frustration level and receive assistance with slightly more difficult texts.

It further recommends that children practice reading independently with texts slightly below their frustration level and receive assistance with slightly more difficult texts.

If the books children read only give them rare opportunities to sound out words that are new to them, they are unlikely to use sounding out as a consistent strategy. A study comparing the achievement of two groups of average-ability first-graders being taught phonics explicitly provides evidence of this. The group of children who used texts with a high proportion of words they could sound out learned to read much better than the group who had texts in which they could rarely apply the phonics they were being taught.

None of this should be read to mean that children should be reading meaningless or boring material. There is no need to return to Dan can fan the man. It's as important that children find joy and meaning in reading as it is that they develop the skills they need. Reading pleasure should always be as much a focus as reading skill. Research shows that the children who learn to read most effectively are the children who read the most and are most highly motivated to read.

Research shows that the children who learn to read most effectively are the children who read the most and are most highly motivated to read.

The texts children read need to be as interesting and meaningful as possible. Still, at the very early stages, this is difficult. It isn't possible to write gripping fiction with only five letter sounds. But a meaningful context can be created by embedding decodable text in stories that provide other supports to build meaning and pleasure. For example, some early first-grade texts use pictures to represent words that students cannot yet decode. Others include a teacher text on each page, read by the teacher, parent, or other reader, which tells part of the story. The students then read their portion, which uses words containing the spelling-sound relationships they know. Between the two types of texts, a meaningful and interesting story can be told.

Strategies for teaching comprehension

Learning to read is not a linear process. Students do not need to learn to decode before they can learn to comprehend. Both skills should be taught at the same time from the earliest stages of reading instruction. Comprehension strategies can be taught using material that is read to children, as well as using material the children read themselves.

Students do not need to learn to decode before they can learn to comprehend. Both skills should be taught at the same time from the earliest stages of reading instruction. Comprehension strategies can be taught using material that is read to children, as well as using material the children read themselves.

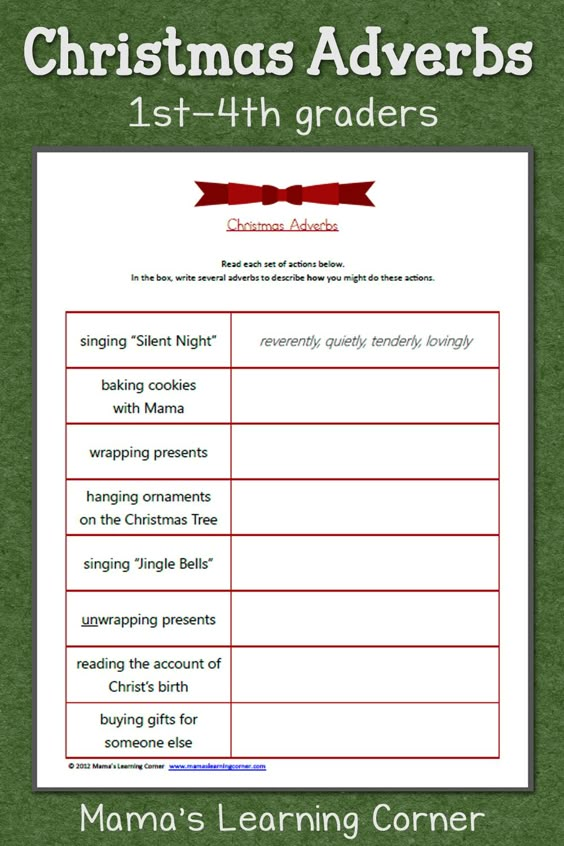

Before reading, teachers can establish the purpose for the reading, review vocabulary, activate background knowledge, and encourage children to predict what the story will be about. During reading, teachers can direct children's attention to difficult or subtle dimensions of the text, point out difficult words and ideas, and ask children to identify problems and solutions. After reading, children may be asked to retell or summarize stories, to create graphic organizers (such as webs, cause-and-effect charts, or outlines), to put pictures of story events in order, and so on. Children can be taught specific metacognitive strategies, such as asking themselves on a regular basis whether what they are reading makes sense or whether there is a one-to-one match between the words they read and the words on the page.

Writing programs

Creative and expository writing instruction should begin in kindergarten and continue during first grade and beyond. Writing, in addition to being valuable in its own right, gives children opportunities to use their new reading competence. Research shows invented spelling to be a powerful means of leading students to internalize phonemic awareness and the alphabetic principle. Still, while research shows that using invented spelling is not in conflict with teaching correct spelling, the National Academy of Sciences report does recommend that conventionally correct spelling be developed through focused instruction and practice at the same time students use invented spelling. The Academy report further recommends that primary grade children should be expected to spell previously studied words and spelling patterns correctly in final writing products.

Smaller class size

Class size makes a difference in early reading performance. Studies comparing class sizes of approximately 15 to those of around 25 in the early elementary grades reveal that class size has a significant impact on reading achievement, especially if teachers are also using more effective instructional strategies. Reductions of this magnitude are expensive, of course, if used all day. An alternative is to reduce class size just during the time set aside for reading, either by providing additional reading teachers during reading periods or by having certified teachers who have other functions most of the day (e.g., tutors, librarians, or special education teachers) teach a reading class during a common reading period.

Reductions of this magnitude are expensive, of course, if used all day. An alternative is to reduce class size just during the time set aside for reading, either by providing additional reading teachers during reading periods or by having certified teachers who have other functions most of the day (e.g., tutors, librarians, or special education teachers) teach a reading class during a common reading period.

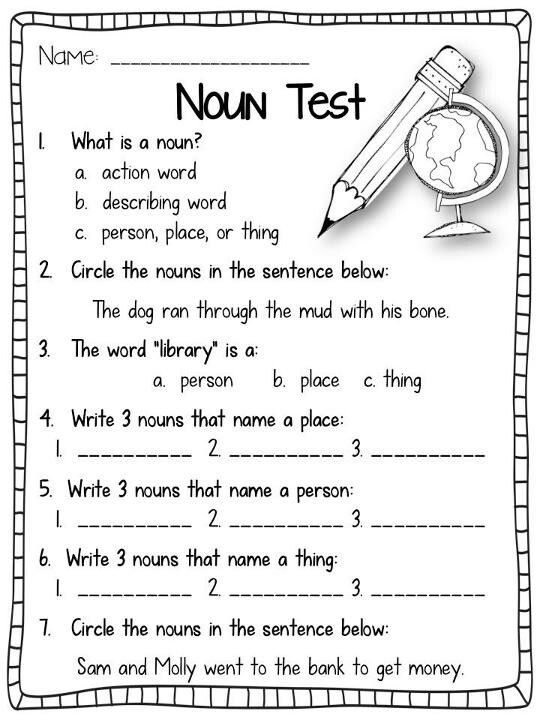

Curriculum-based assessment

In first grade and beyond, regular curriculum-based assessments are needed to guide decisions about such things as grouping, the pace of instruction, and individual needs for assistance (such as tutoring). The purpose of curriculum-based assessment is to determine how children are doing in the particular curriculum being used in the classroom or school, not to indicate how children are doing on national norms. In first grade, assessments should focus on all of the major components of early reading: decoding of phonetically regular words, recognition of sight words, comprehension, writing, and so on.

Informal assessments can be conducted every day. Anything children do in class gives information to the teacher that can be used to adjust instruction for individuals or for the entire class. Regular schoolwide assessments based on students' current reading groups can be given every six to 10 weeks. These might combine material read to children, material to which children respond on their own, and material the child reads to the teacher individually. These school assessments should be aligned as much as possible with any district or state assessments students will have to take.

Effective grouping strategies

Children enter first grade at very different points in their reading development. Some already read, while others lack even the most basic knowledge of letters and sounds. Recognizing this, schools have long used a variety of methods to group children for instruction appropriate to their needs. Each method has its own advantages and disadvantages.

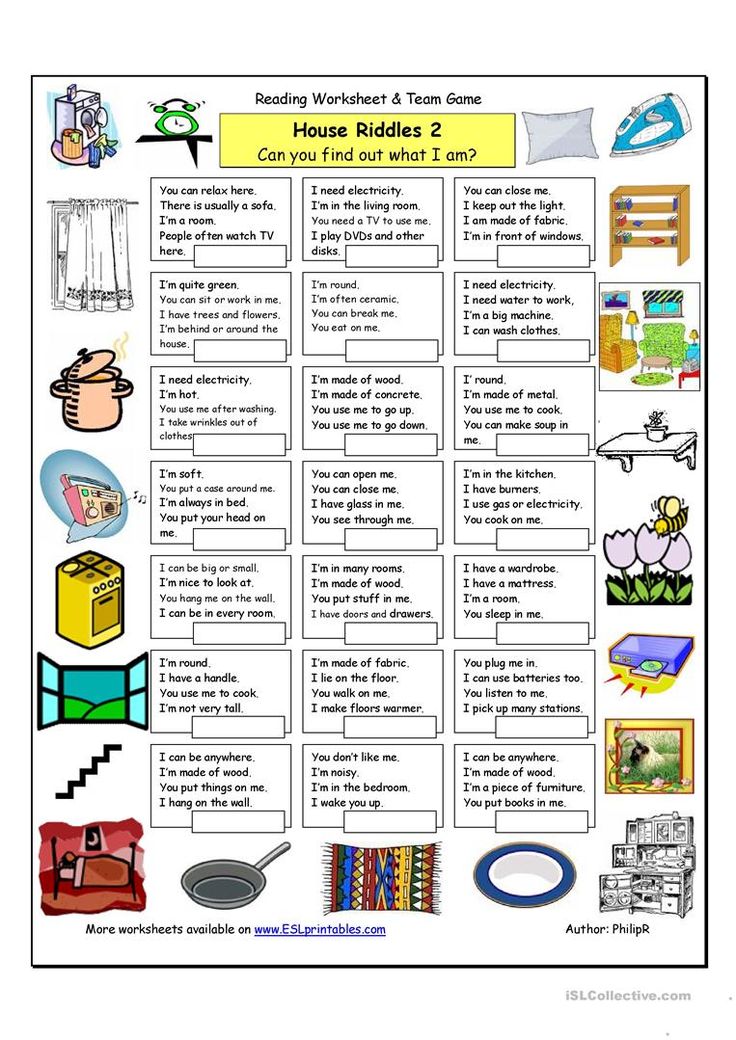

The most common method is to divide children within their own class into three or more reading groups, which take turns working with the teacher. The main problem with this strategy is that it requires follow-up time activities children can do on their own while the teacher is working with another group. Studies of follow-up time find that, all too often, it translates to busywork. Follow-up time spent in partner reading, writing, working with a well-trained paraprofessional, or other activities closely linked to instructional objectives may be beneficial; but teachers must carefully review workbook, computer, or other activities to be sure they are productive.

The main problem with this strategy is that it requires follow-up time activities children can do on their own while the teacher is working with another group. Studies of follow-up time find that, all too often, it translates to busywork. Follow-up time spent in partner reading, writing, working with a well-trained paraprofessional, or other activities closely linked to instructional objectives may be beneficial; but teachers must carefully review workbook, computer, or other activities to be sure they are productive.

Another strategy is grouping within the same grade. For example, during reading time there might be a high, middle, and low second-grade group. The problem with this type of grouping is that it creates a low group with few positive models.

Alternatively, children in all grades can be grouped in reading according to their reading level and without regard to age. A second-grade-level reading class might include some first-graders, many second-graders, and a few third-graders. An advantage of this approach is that it mostly eliminates the low group problem, and gives each teacher one reading group. The risk is that some older children will be embarrassed by being grouped with children from a lower grade level. Classroom management and organization for reading instruction are areas that deserve further research and attention.

An advantage of this approach is that it mostly eliminates the low group problem, and gives each teacher one reading group. The risk is that some older children will be embarrassed by being grouped with children from a lower grade level. Classroom management and organization for reading instruction are areas that deserve further research and attention.

Tutoring support

Most children can learn to read by the end of first grade with good-quality reading instruction alone. In every school, however, there are children who need more assistance. Small-group remedial methods, such as those typical of Title I or special education resource room programs, have not generally been found to be effective in increasing the achievement of these children. One-to-one tutoring, closely aligned with classroom instruction, has been effective for struggling first-graders. While it is often best to have certified teachers working with children with the most serious difficulties, well-trained paraprofessionals can develop a valuable expertise for working with these children. Trained volunteers who are placed in well-structured, well-supervised programs also can be a valuable resource.

Trained volunteers who are placed in well-structured, well-supervised programs also can be a valuable resource.

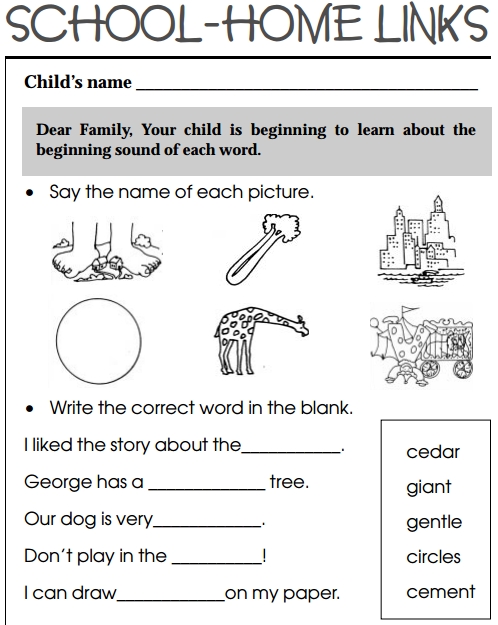

Home reading

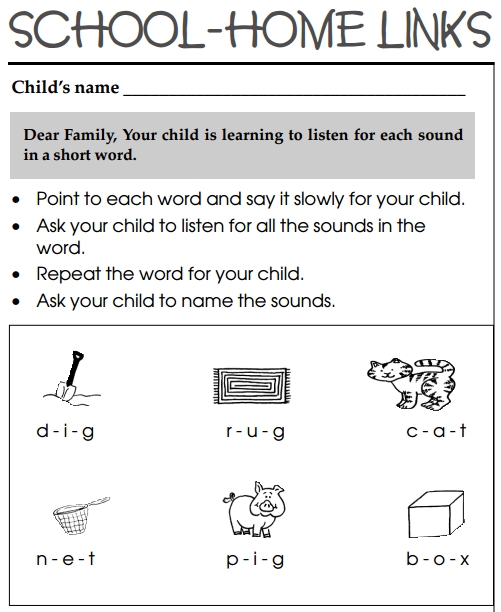

Children should be spending more time on reading than is available at school. They should read at home on a regular basis, usually 20 to 30 minutes each evening. Parents can be asked to send in signed forms indicating that children have done their home reading. Many teachers ask that children read aloud with their parents, siblings, or others in first grade and then read silently thereafter. The books the children read should be of interest to them and should match their reading proficiency.

How To Help 1st Grader Read Fluently

When our children are first learning to read, we want them to be successful. As a parent, you are likely to try to find out how to help 1st grader read better. By first grade, kids are learning to read full-length books and are able to read longer, more complex sentences.

This means that your child is reading at a more challenging level and might be struggling. Their reading fluency is likely a factor in how well they are understanding a text.

Their reading fluency is likely a factor in how well they are understanding a text.

What should a 1st grader be able to read?

By 1st grade your child should have at least the following variety of reading skills:

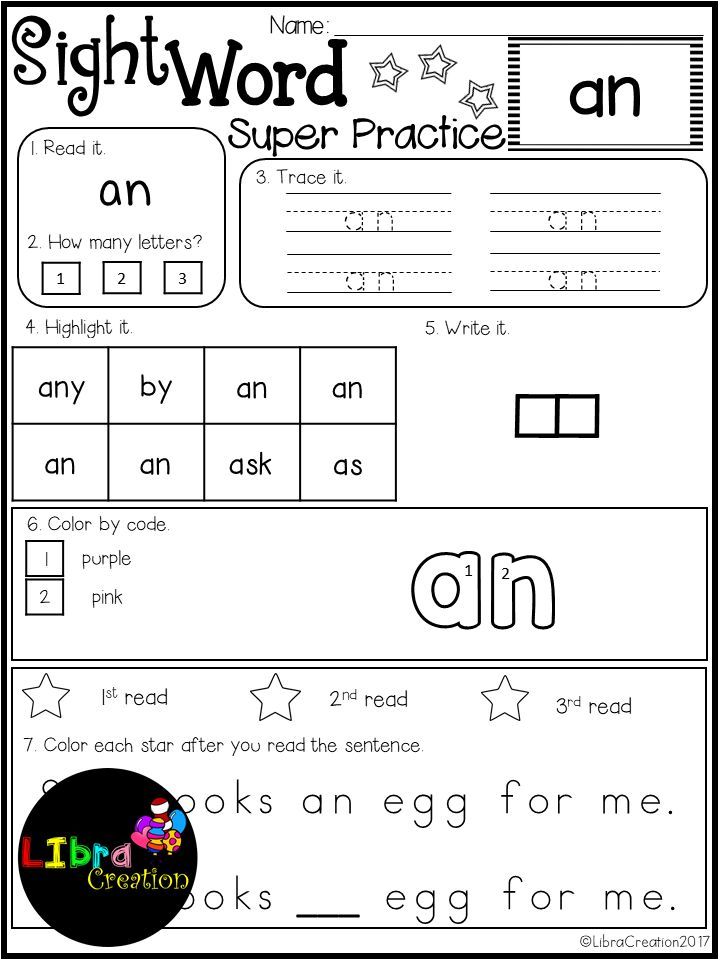

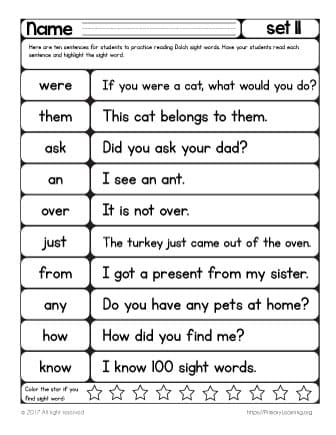

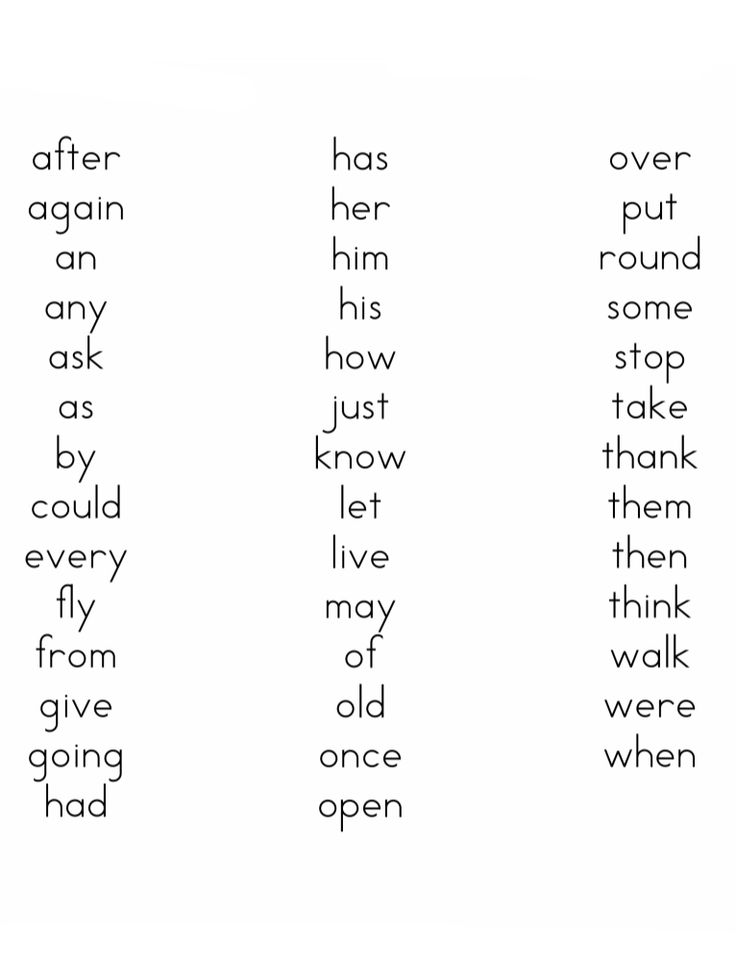

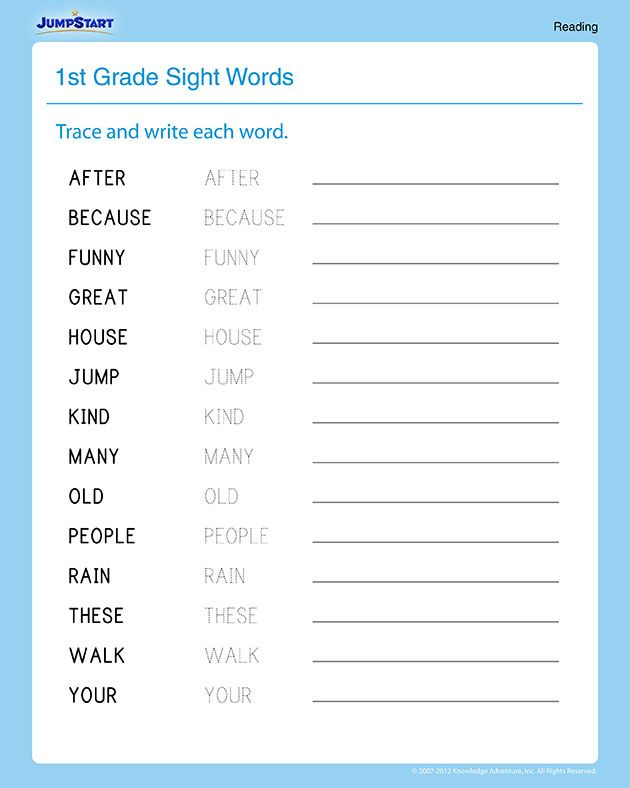

- They should be able to recognize about 150 sight words or high-frequency words.

- They are able to distinguish between fiction and nonfiction texts.

- They should be able to recognize the parts of a sentence such as the first word, capitalization, and punctuation.

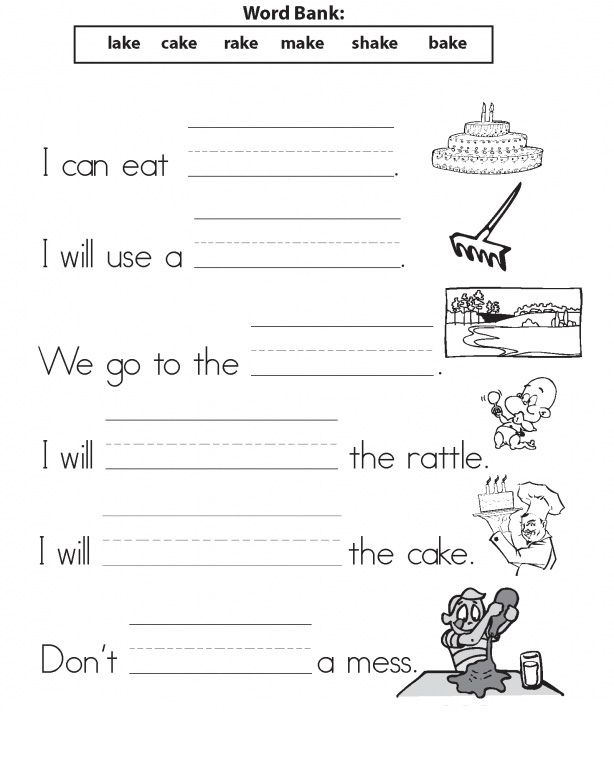

- They are able to understand how a final “e” will change the sound of the vowels within a word.

- They are able to answer questions and recall details from a reading.

- They are able to read fluently meaning with speed, accuracy, and prosody.

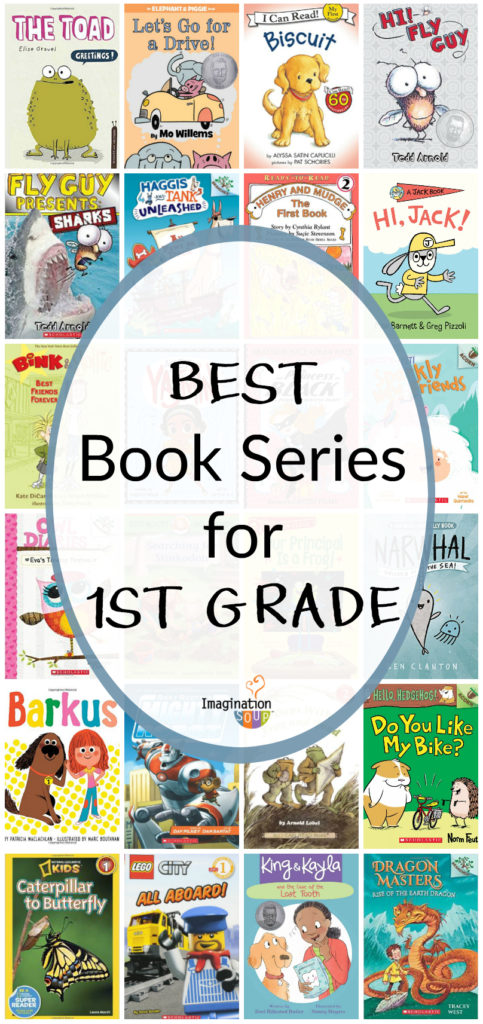

Your first grader should be able to begin reading the first few levels of graded reader books. A graded reader book is a book that is set at a certain reading level. These books are often used in schools to help measure student progress.

These books are often used in schools to help measure student progress.

What is fluency in reading?

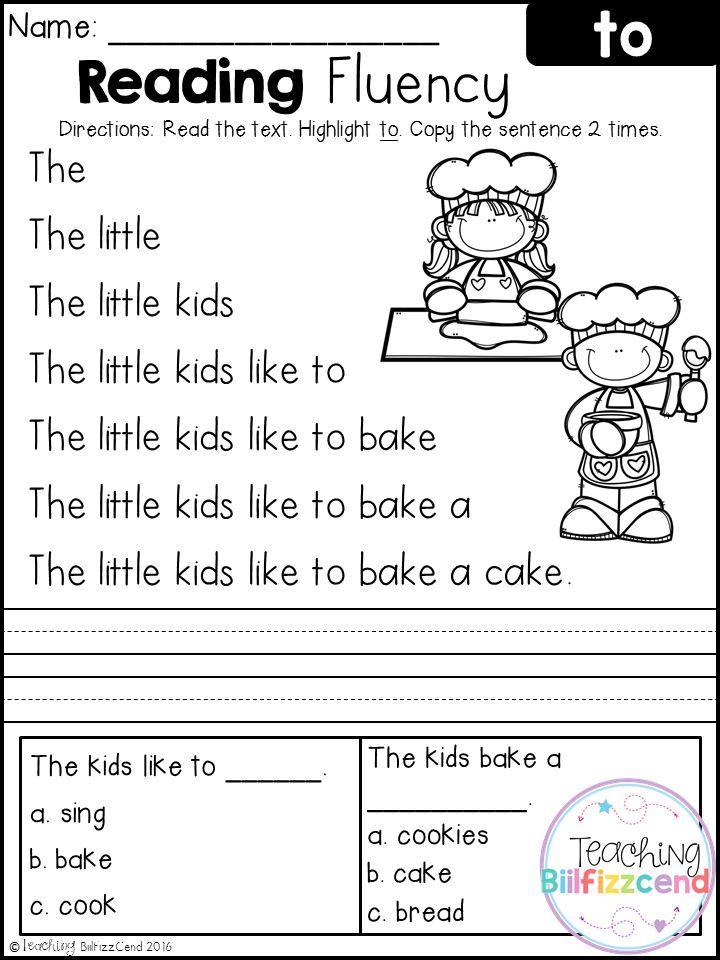

Reading fluency is the ability to “read how you speak”. This means that your child is reading at a conversational pace with appropriate expression. Reading fluency is important because it is directly related to reading comprehension. The more fluent a reader is the better they understand the text.

Fluency in reading relies on speed, accuracy, and prosody. These factors make for a fluent reader and help your 1st grader not only to recognize words but to actually understand and comprehend text.

- Speed – Fluent readers read at a speed that is accurate for their grade level which is 60 words per minute for 1st graders.

- Accuracy – Fluent readers are able to recognize words quickly and have the skills to sound out and decode words they are unfamiliar with.

- Prosody – Fluent readers use expression and intonation to bring meaning into their readings.

This is not just recognizing words, but also recognizing that expression also plays a part in understanding.

This is not just recognizing words, but also recognizing that expression also plays a part in understanding.

How can I help my 1st grader with reading fluency?

There are a variety of things you can do at home to help your 1st grader read more fluently:

- Model reading – Children learn best when they have a model showing them the skills they are meant to be learning. Reading to your child regularly provides a model of fluent reading for them.

- Echo Reading – As you and your child read a text, read one sentence then have them read the same sentence out loud. This form of repeated reading helps them see you model fluency then lets them practice it.

- Reader’s theatre – Turn a book into a script and have your kids bring the story to life. This will help them practice their expression and intonation when they read.

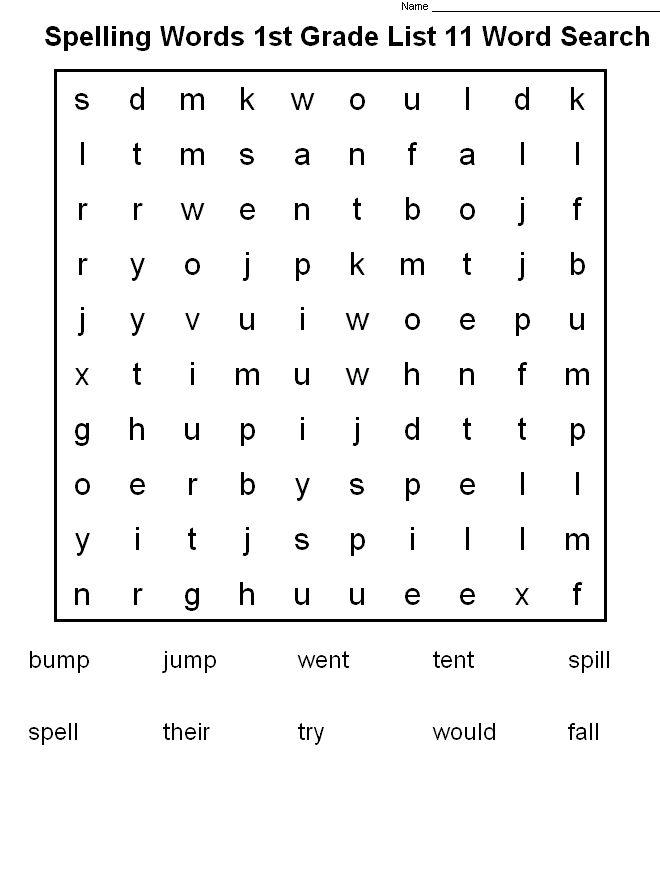

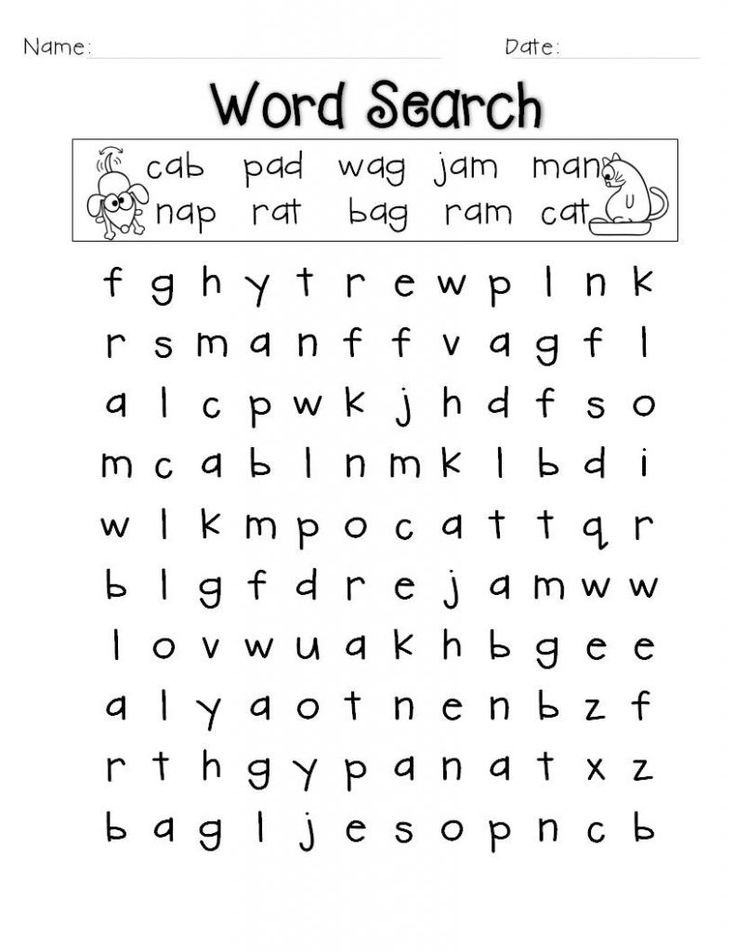

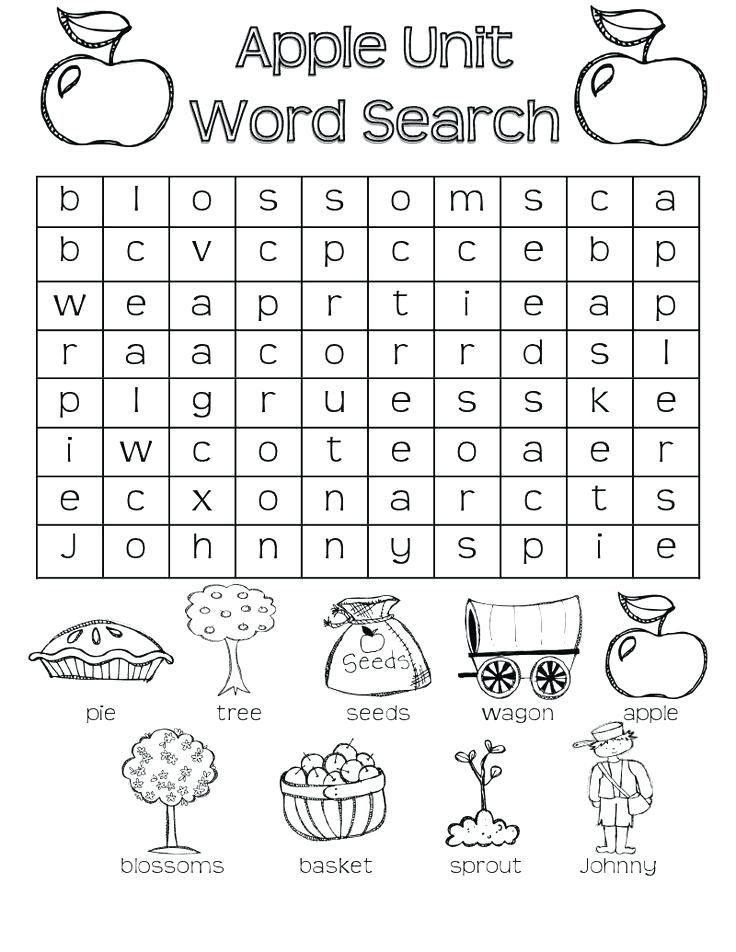

- Practice sight words – The more words your child recognizes, the more fluent they will become.

Use word games and flashcards to help them learn sight words to help them read less choppy.

Use word games and flashcards to help them learn sight words to help them read less choppy. - Extensive reading – The best way to help your 1st grader to read fluently is to get them to read a lot! Provide lots of books of their choice at home and get them to enjoy reading so that they practice often.

- Utilize reading apps – Most kids play with technology already such as tablets and smartphones. Why not incorporate reading into this game time by downloading some reading apps?

Which reading app is helpful for improving fluency?

Readability is an app that helps improve fluency for emerging readers. The app is a great way to increase fluency for your 1st grader because it uses A.I. technology and speech-recognition to recognize errors your child might be making when reading out loud.

Readability provides a large library of original content that your child can read and is constantly being updated with new stories. The app works like a private tutor by actually listening to your child read out loud and recognizing their errors. It then provides feedback to help them improve. It can also read the material to your child as they follow along.

It then provides feedback to help them improve. It can also read the material to your child as they follow along.

These forms of repeated reading can help your 1st grader practice their fluency wherever and whenever they want. Try Readability for free!

How to teach a child to read: techniques from an experienced teacher

At what age should you start teaching a child to read

Speech therapist Naya Speranskaya believes that the optimal age at which you can gradually start learning to read is 5.5 years.

“But still, the starting point for the first steps in this matter should be not a specific age, but the child himself. There are children who are ready to master the skill as early as 3-4 years old, and there are those who "mature" closer to grade 1. Once I worked with a boy who could not read at 6.5 years old. He knew letters, individual syllables, but he could not read. As soon as we began to study, it became clear that he was absolutely ready for reading, in two months he began to read perfectly in syllables, ”said Speranskaya.

How to teach a child to read quickly and correctly

The first thing you need to teach your baby is the ability to correlate letters and sounds. “In no case should a child be taught the names of letters, as in the alphabet: “em”, “be”, “ve”. Otherwise, training is doomed to failure. The preschooler will try to apply new knowledge in practice. Instead of reading [mom], he will read [me-a-me-a]. You are tormented by retraining, ”the speech therapist warned.

Therefore, it is important to immediately give the child not the names of the letters, but the sounds they represent. Not [be], but [b], not [em], but [m]. If the consonant is softened by a vowel, then this should be reflected in the pronunciation: [t '], [m'], [v '], etc.

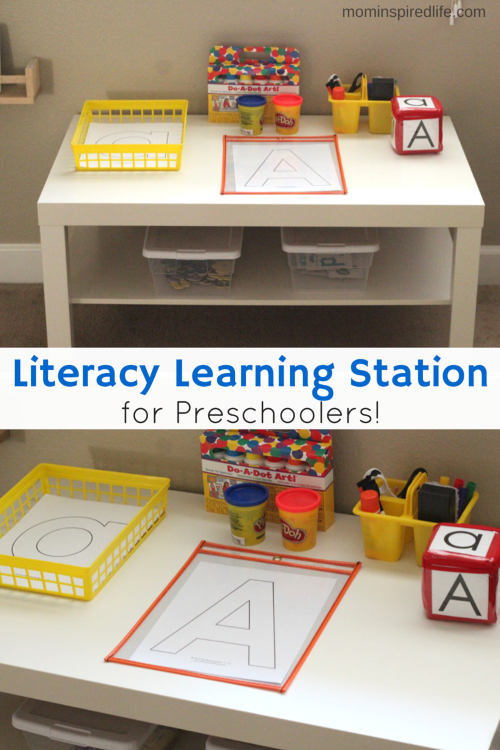

To help your child remember the graphic symbols of letters, make a letter with him from plasticine, lay it out with buttons, draw with your finger on a saucer with flour or semolina. Color the letters with pencils, draw with water markers on the side of the bathroom.

“At first it will seem to the child that all the letters are similar to each other. These actions will help you learn to distinguish between them faster, ”said the speech therapist.

As soon as the baby remembers the letters and sounds, you can move on to memorizing syllables.

close

100%

How to teach your child to join letters into syllables

“Connecting letters into syllables is like learning the multiplication table. You just need to remember these combinations of letters, ”the speech therapist explained.

Naya Speranskaya noted that most of the manuals offer to teach children to read exactly by syllables. When choosing, two nuances should be taken into account:

1. Books should have little text and a lot of pictures.

2. Words in them should not be divided into syllables using large spaces, hyphens, long vertical lines.

“All this creates visual difficulties in reading. It is difficult for a child to perceive such a word as something whole, it is difficult to “collect” it from different pieces. It is best if there are no extra spaces or other separating characters in the word, and syllables are highlighted with arcs directly below the word, ”the speech therapist explained.

It is best if there are no extra spaces or other separating characters in the word, and syllables are highlighted with arcs directly below the word, ”the speech therapist explained.

According to Speranskaya, cubes with letters are also suitable for studying syllables - playing with them, the child will quickly remember the combinations.

Another way to gently help your child learn letters and syllables is to print them in large print on paper and hang them all over the apartment.

“Hang them on the fridge, on the board in the nursery, on the wall in the bathroom. When such leaflets are hung throughout the apartment, you can inadvertently return to them many times a day. Do you wash your hands? Read what is written next to the sink. Is the child waiting for you to give him lunch? Ask him to name which syllables are hanging on the refrigerator. Do a little, but as often as possible. Step by step, the child will learn the syllables, and then slowly begin to read,” the specialist said.

Speranskaya is sure that in this way the child will learn to read much faster than after daily classes, when parents seat the child at the table with the words: “Now we will study reading ...”

“If it is really difficult for you to give up such activities, then pay attention that the nervous system of preschoolers is not yet ripe for long and monotonous lessons. Children spend enormous efforts on the analysis of graphic symbols. Learning to read for them is like learning a very complex cipher. Therefore, it is necessary to observe clear timing in such classes. At 5.5 years old, children are able to hold attention for no more than 10 minutes, at 6.5 years old - 15 minutes. That's how long one lesson should last. And there should be no more than one such “lessons” a day, unless, of course, you want the child to lose motivation for learning even before school,” the speech therapist explained.

How to properly explain to a child how to divide words into syllables

When teaching a child to divide words into syllables, use a pencil. Mark syllables with a pencil using arcs.

Mark syllables with a pencil using arcs.

close

100%

“Take the word dinosaur. It can be divided into three syllables: "di", "but", "zavr". The child will read the first syllables without difficulty, but it will be difficult for him to master the third. The kid cannot look at three or four letters at once. Therefore, I propose to teach to read not entirely by syllables, but by the so-called syllables. This is when we learn to read combinations of consonants and vowels, and we read the consonants separately. For example, we will read the word "dinosaur" like this: "di" "but" "for" "in" "p" The last two letters are read separately from "for". If you immediately teach a child to read by syllables, he will quickly master complex words and move on to fluent reading, ”the speech therapist is sure.

In a text, syllables can be labeled in much the same way as syllables. Vowel + consonant with the help of an arc, and a separate consonant with the help of a dot.

Naya Speranskaya gave parents a recommendation to memorize syllables/syllable fusions for as long as possible, and move on to texts only when the child suggests it himself.

“If a preschooler is not eager to read, then there is no need to put pressure on him. Automate syllables. Take your time. Learning should take place gradually, from simple to complex. The reading technique develops over time, ”added Speranskaya.

Another important clarification from the speech therapist: when the child begins to read words and then sentences, parents need to clarify the meaning of what they read.

“The child reads the word “mom”, after that you ask the question: “what does it mean that you just read it”,” the speech therapist shared, “It is necessary that the child not only reads well, but also feels the meaning of what he read. Unfortunately, it is not uncommon to meet children who “spell” entire texts, but are not able to explain what they are about.”

Naya Speranskaya recommended the following manuals for home schooling:

1. A book to start learning to read - a set of Bezrukov O. A. Kalenkova O. N. "Lessons of Russian literacy", publishing house "Russian Rech"

2. Posters for teaching reading and letter of V. G. Dmitriev, publishing house "AST"

Posters for teaching reading and letter of V. G. Dmitriev, publishing house "AST"

3. "Come on, letter, respond!" Kolesnikova E.V., workbook

4. Books from the series “We read ourselves” by the publishing house “Vakosha”

We teach a child to read syllables easily. 5 fun games

Teach your child to read by syllables, but nothing works? Do you repeat 10 times, but after a couple of seconds he forgets everything, and all your attempts end in screams and tears? Of course, school is coming soon and a slight panic seizes you, but relax and don't worry. Maybe your child is just not ready yet, or maybe you started wrong. Stay with us and find out everything.

How to teach a child to read in syllables so that he likes it?

If your child already knows the letters, but does not want to learn to read by syllables, most likely you simply did not explain why he needs it. Arguments like “to learn to read”, “to do well in school and be no worse than others” do not work. The child needs to understand why he is doing this at the moment? That is, you must “sell” him the idea of learning to read in syllables so that he wants it himself and is still satisfied.

The child needs to understand why he is doing this at the moment? That is, you must “sell” him the idea of learning to read in syllables so that he wants it himself and is still satisfied.

How to do it?

Start with what your child is interested in. For example, while walking around the city, draw his attention to the poster of a cinema or circus and ask: “Are you interested in knowing which cartoon will be shown in the cinema? Let's honor." Or here is another good example: “Ice cream, what flavor would you like? Let's read what they offer here? Of course, the child will say that he cannot read and ask you to help him. Then you explain to him why you need to be able to read and what is the use of this.

The idea is "sold" - you can start learning!

If your child does not yet know the whole alphabet, then at the same time as learning the letters, you can begin to make small words out of them. Did the child learn two or three letters? For example "M", "U", "I". Excellent! Fold them immediately into the word "MEW" and ask the child who does this. Then ask him to repeat after you syllable by syllable: “meow”, pausing after the first syllable.

Excellent! Fold them immediately into the word "MEW" and ask the child who does this. Then ask him to repeat after you syllable by syllable: “meow”, pausing after the first syllable.

Thanks to this approach, it will be easier for the child to read longer words in syllables in the future.

5 fun exercises to teach children to read by syllables

The first rule that all parents should remember before starting to teach anything to their child under 7 years old is no coercion, always translate everything into a game. Then your child will be happy to participate in the process, and you will see the result faster.

Therefore, all the exercises that we have selected for you are in the form of a game.

Surprise eggs

Take some plastic Kinder Surprise eggs and small cardboard cards with letters. Think of a game scenario. For example, put the letters in the eggs that make up the name of the child's favorite cartoon character according to the principle - one egg - one letter. Then call the child and say that you need to find the name of the hero, otherwise he is lost and cannot find his way home. Then begin to open the eggs together and fold the name in such a way that there is a small distance between the syllables, for example "BIN-GO". As soon as you add up the name, ask the child to read it in syllables and call the hero so that he can find his way home.

Then call the child and say that you need to find the name of the hero, otherwise he is lost and cannot find his way home. Then begin to open the eggs together and fold the name in such a way that there is a small distance between the syllables, for example "BIN-GO". As soon as you add up the name, ask the child to read it in syllables and call the hero so that he can find his way home.

When the child manages to name all the characters, you can give him the toy characters he called (if there are such toys at home) or turn on your favorite cartoon.

Find a double

Take blocks with letters and together with your child make a syllable out of two letters. For example, let there be a syllable "BA". Say the syllable several times so that the child remembers it. Then ask him to find the familiar syllable "BA" on the pages of any book.

Of course, it may not work the first time. But nothing, praise the child for every syllable found and say that this is just a game and in case of failure you should not be upset.

This exercise develops visual memory well and helps the child get used to syllables.

Let's be friends

What could be more boring than just combining vowels and consonants into syllables? Another thing is to teach letters to be friends so that they make up words. You will need a metal board and letters on magnets. Arrange the letters on the right and left in this order:

Then tell the child that the letters quarreled and they need to be connected and made friends. Move together the letter "A" to "U" and read what happened - "AU". So the child will understand that connecting letters into syllables is fun and will begin to connect syllables into words with pleasure.

⠀

Also learn to read by syllables with our free games.

Pick me up

In this exercise you will have to get a little creative. Take an A4 sheet and draw a dog on it. Sign the word “SO-BA-KA” under the drawing by syllables. Then take scissors and cut vertically so that you get three equal parts with pattern elements and syllables. Ask the child to read each syllable separately, and then ask the dog to collect and read the word syllable by syllable.

Ask the child to read each syllable separately, and then ask the dog to collect and read the word syllable by syllable.

If you have no time to draw yourself, look for similar puzzles in the store.

This fun exercise will quickly help your child learn to read long words.

Transformer Word

Blocks or cards with letters are suitable for this exercise. For example, put together the already familiar word “SO-BA-KA” with your child. Read it syllable by syllable and disassemble it into individual letters. Say: “And now you will see how much our “DOG” can give us new words! Let's watch?".

Then form new words from individual letters: “SOK”, “TANK”, “BOK”, “KO-SA”. Make up words in turn, ask the child to read each syllable by syllable and explain the meaning of what they read.

This exercise allows you to learn to read several words from familiar syllables in one session.